↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Deep learning models often use attention layers, where parameter matrices interact multiplicatively. The effects of weight decay (a common regularization technique) on such models are not well understood, particularly regarding the rank (a measure of complexity) of the resulting matrices. There’s concern that excessive weight decay might negatively impact performance.

This paper investigates the influence of weight decay, specifically showing theoretically and empirically that it induces low-rank attention matrices. The authors demonstrate that the Frobenius norm regularization (related to weight decay) and nuclear norm regularization (related to low-rank) converge quickly during training in models with multiplicative parameter matrices. They validate this on various network architectures. Importantly, they observe that decoupling weight decay for attention layers can enhance performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it reveals a previously unknown link between weight decay and the low rank of attention layers in deep neural networks. This challenges common training practices and suggests improvements for training large language models, impacting various AI research areas. It also provides a strong theoretical foundation for future work on understanding and optimizing the training dynamics of deep learning models.

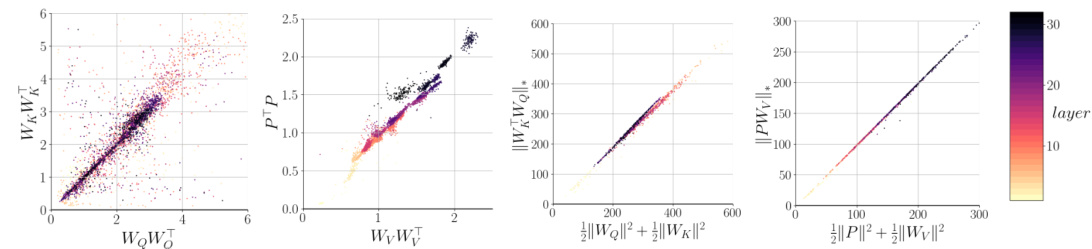

Visual Insights#

This figure empirically validates the theoretical findings of the paper regarding the equivalence between L2-regularized and nuclear norm-regularized losses when optimizing with factorized parameter matrices (W=ABT). It shows how the difference between the Frobenius norm (||A||² + ||B||²) and the nuclear norm (||ABT||*) of the matrix product decreases exponentially fast during training as the regularization strength (λ) increases. The plots illustrate this convergence, the vanishing discrepancy between ATA and BTB, the linear decay of singular values with λ, and the overall behavior of singular values during optimization. All of these observations support the claim that L2 regularization implicitly enforces low-rank solutions in the factorized setting.

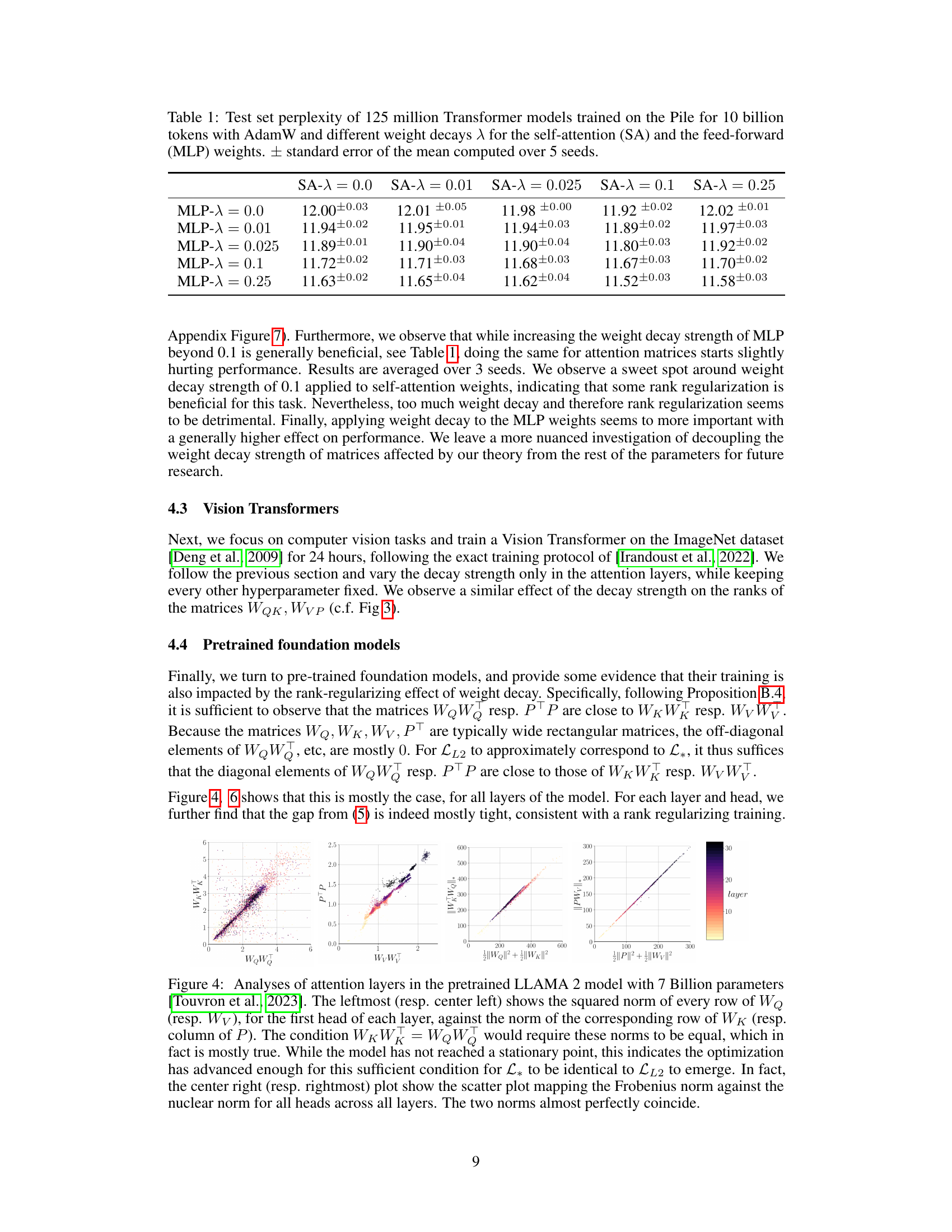

This table presents the test set perplexity results for various Transformer models trained on the Pile dataset. The models were trained using the AdamW optimizer with different weight decay values (λ) applied separately to the self-attention (SA) and Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP) layers. The table shows the impact of varying weight decay strength on model performance, indicating an optimal range and revealing potential differences in sensitivity between the SA and MLP layers. The values reported are averages across five separate training runs.

In-depth insights#

Low-Rank Attention#

Low-rank attention mechanisms offer a potential pathway to enhancing the efficiency and performance of attention-based models. By reducing the rank of the attention matrices, we can decrease computational cost and memory footprint, making it feasible to deploy larger and more complex models. This low-rank approximation may also provide a form of implicit regularization, potentially mitigating overfitting and improving generalization. However, it is crucial to carefully consider the trade-offs involved, as low-rank approximations can lead to information loss, impacting model performance. Decoupling weight decay in attention layers, a common technique, is worth exploring since the resulting low rank may be detrimental to language modeling. Further research should investigate how to effectively balance the benefits of reduced computational cost with the need to preserve essential information for optimal performance. Empirically validating the effects of low-rank attention across various tasks and datasets is vital to establish its broad applicability and understand its impact in different contexts.

L2 vs. Nuclear Norm#

The core of the paper revolves around the relationship between L2 regularization and the nuclear norm, especially within the context of deep learning models using factorized parameterizations like those found in attention layers. The authors demonstrate a surprising equivalence between minimizing a loss function regularized by the Frobenius norm (related to L2) of the factorized matrices and minimizing a loss regularized by the nuclear norm of their product. This is particularly significant because the nuclear norm is a well-known low-rank inducer, implying that L2 regularization on factorized parameters implicitly encourages low-rank solutions. The theoretical results are backed by empirical evidence, showcasing how weight decay, a common form of L2 regularization, consistently reduces the rank of attention matrices in various models. Decoupling weight decay in attention layers from other model parameters is explored as a way to potentially mitigate this unintended low-rank inducing effect.

AdamW & Weight Decay#

The interplay between AdamW, an adaptive learning rate optimizer, and weight decay regularization is a complex topic in deep learning. AdamW, an improved version of Adam, addresses some of Adam’s limitations but doesn’t inherently resolve the challenges associated with weight decay. Weight decay’s main function is to prevent overfitting by adding a penalty to the loss function that’s proportional to the magnitude of the model’s weights. This penalty discourages large weights, which helps in reducing the model’s complexity and improving its generalization capabilities. However, weight decay’s interaction with AdamW, which adjusts learning rates adaptively, can be subtle and potentially lead to unexpected effects. A key issue is the decoupling of weight decay. Many implementations separate weight decay from the main optimization step. This approach maintains the regularizing effect of weight decay while allowing AdamW to function more effectively. Research is ongoing to fully understand the effects of combining these two techniques, with a focus on how this interplay impacts attention layers, model stability, and overall performance. Empirical studies are critical to confirm theoretical findings and explore the best practices for combining AdamW and weight decay in different deep learning models.

Empirical Validation#

An empirical validation section in a research paper would typically present experimental results to support the paper’s claims. It should demonstrate how the theoretical findings translate into real-world applications, showcasing the effectiveness and limitations of the proposed methods. A strong empirical validation would include rigorous testing on diverse and relevant datasets, along with careful analysis of performance metrics. Clear visualizations and statistical significance testing are essential to communicate results effectively and convincingly. This section might also involve comparing the proposed method against existing state-of-the-art techniques, offering a comparative analysis of their respective strengths and weaknesses. Furthermore, a discussion of any unexpected or counterintuitive results would strengthen the section by acknowledging limitations and potential areas for improvement. Finally, a comprehensive evaluation considering all aspects of implementation such as speed and scalability adds depth and enhances the overall credibility of the study.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this paper on weight decay’s impact on attention layers could explore several key areas. Firstly, a more in-depth investigation into the interaction between weight decay, adaptive optimizers (like AdamW), and the resulting rank reduction in attention matrices is needed. This could involve a deeper theoretical analysis or more extensive empirical evaluations on larger language models. Secondly, the impact of decoupling weight decay in attention layers from other layers warrants further study, particularly to assess its efficacy and generality across diverse network architectures and tasks. Thirdly, the research could delve into the implications of this rank-reducing effect on the generalization ability of models, potentially examining the relationship between low-rank attention and overfitting or underfitting. Finally, the theoretical analysis could be extended to other attention mechanisms, such as those employing different activation functions or normalization techniques.

More visual insights#

More on figures

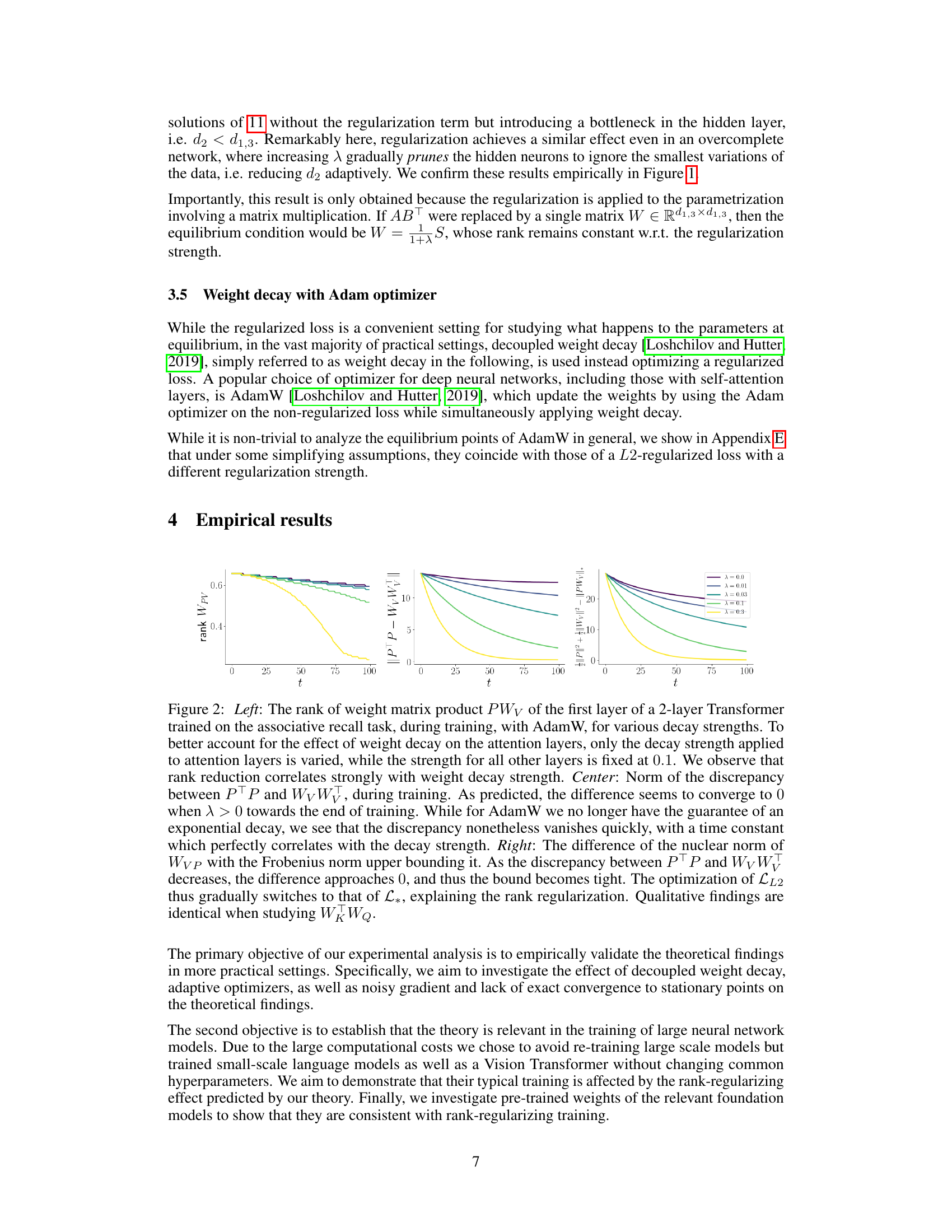

This figure empirically validates the theoretical findings of the paper. It shows the effect of weight decay (λ) on the rank of the matrix product PWv in a 2-layer Transformer. The left panel shows a strong correlation between increasing weight decay and decreasing rank. The center panel demonstrates that the discrepancy between ||PTP|| and ||WvTWv|| decreases exponentially fast with increasing weight decay. The right panel shows that the difference between the nuclear norm and the Frobenius norm approaches zero with increasing weight decay, indicating a transition from LL2 optimization to L* optimization which explains the observed rank regularization.

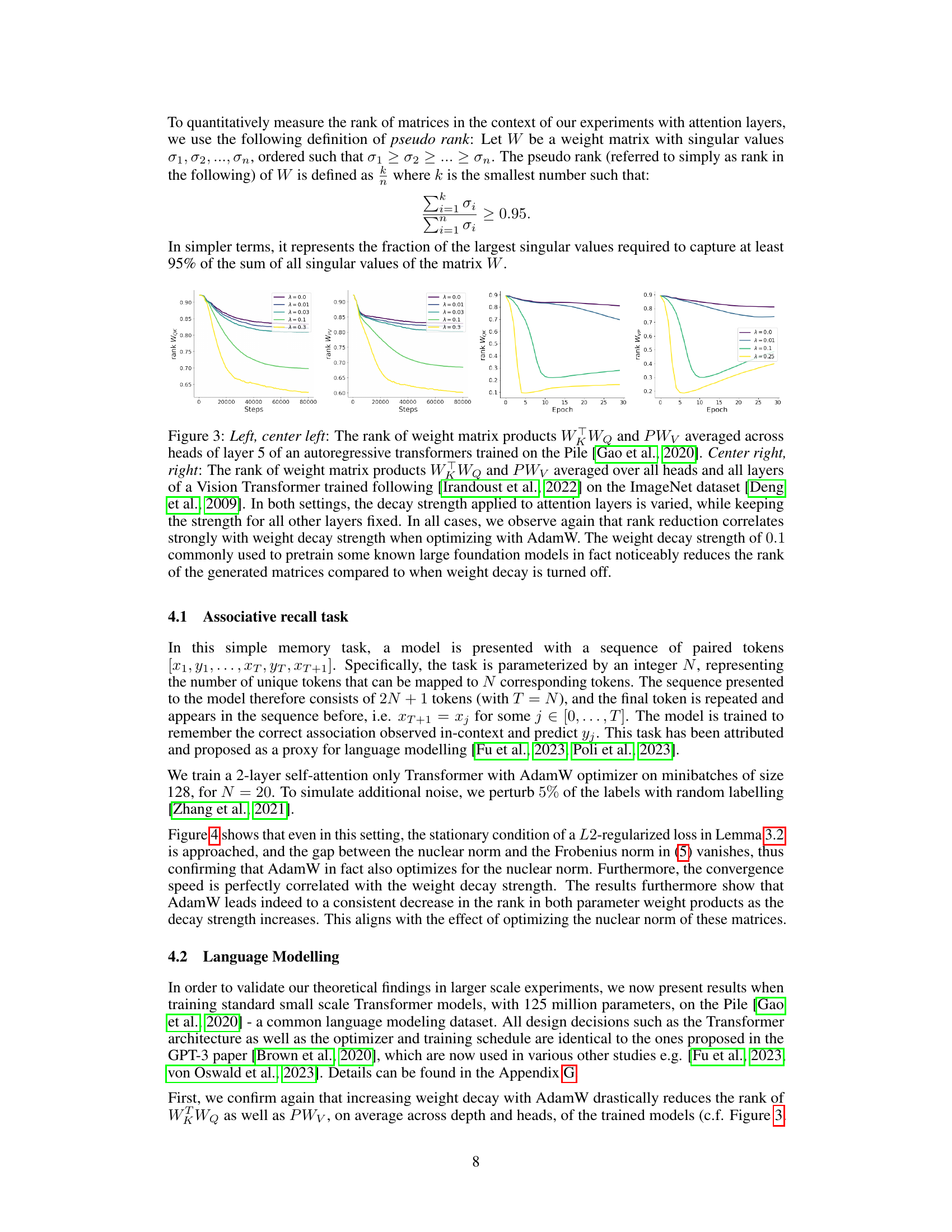

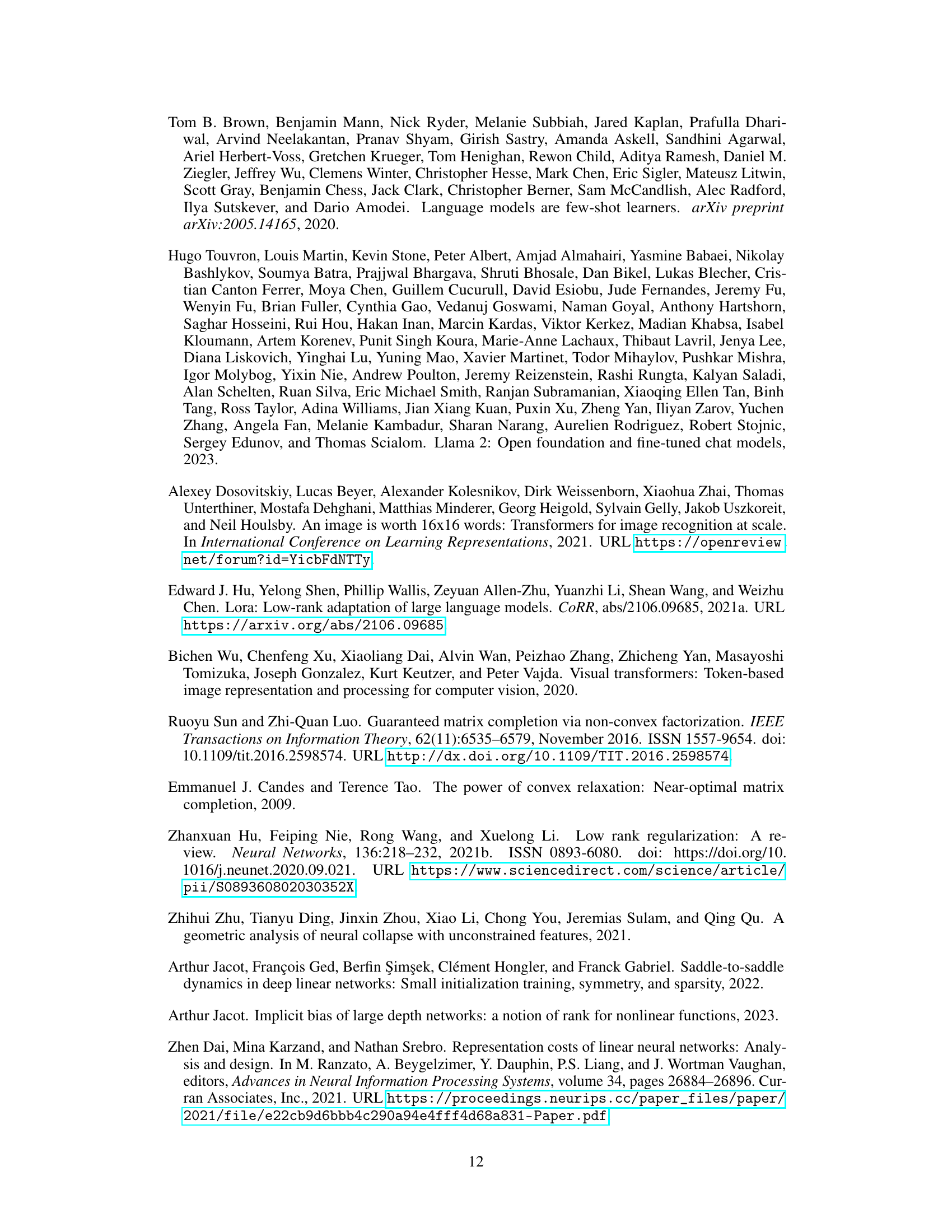

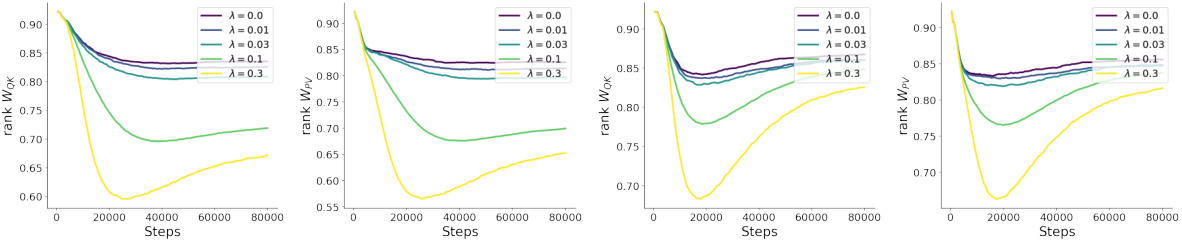

This figure shows the impact of weight decay on the rank of attention matrices in two different types of transformer models: an autoregressive transformer and a vision transformer. The left and center-left panels display the rank of attention weight matrices (WKWQ and PWv) across heads in layer 5 of an autoregressive transformer trained on the Pile dataset. The center-right and right panels show the average rank of the same matrices across all heads and layers of a vision transformer trained on the ImageNet dataset. In both experiments, the weight decay strength applied to the attention layers was varied while keeping the strength for other layers constant. The results clearly demonstrate that increasing weight decay strength reduces the rank of the attention weight matrices, consistent across both model architectures.

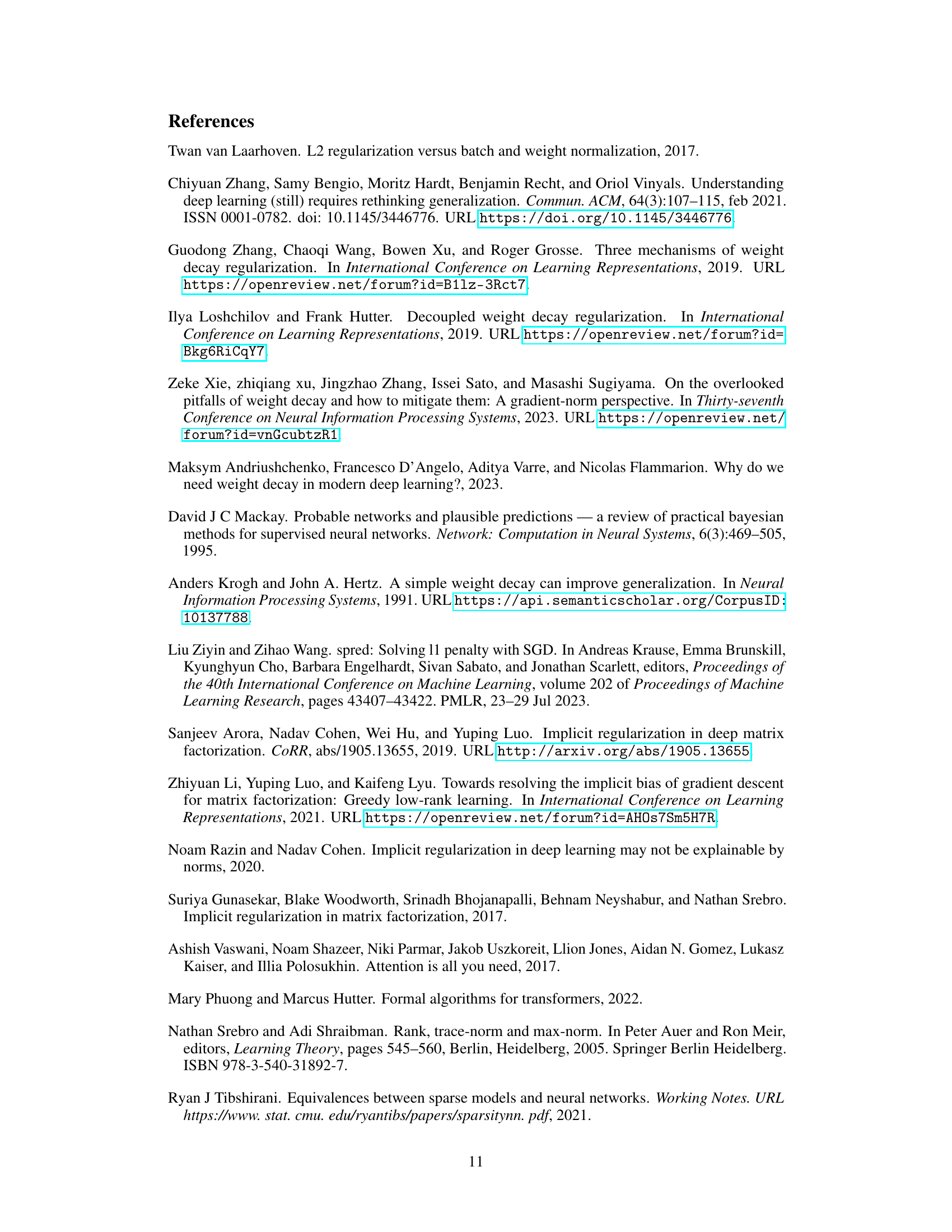

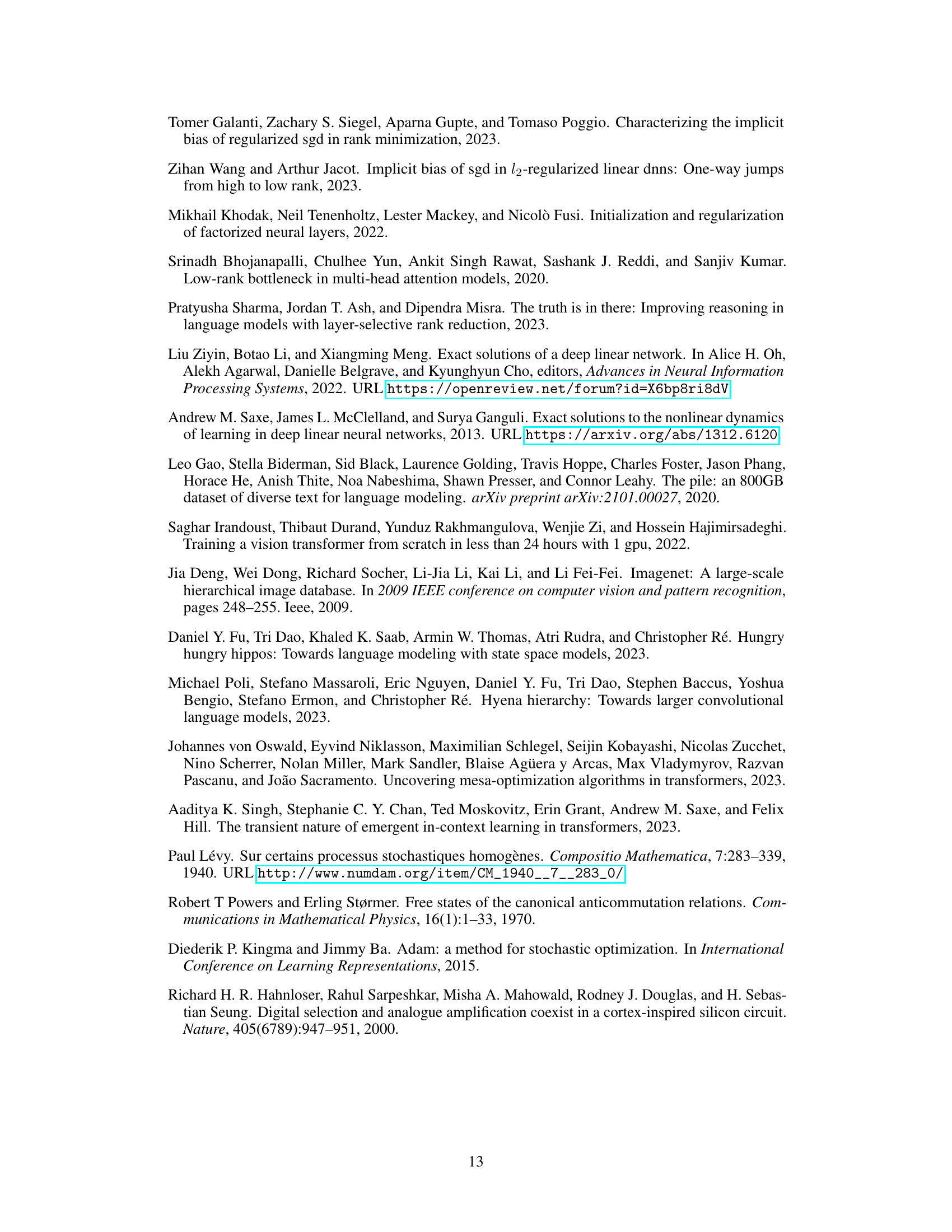

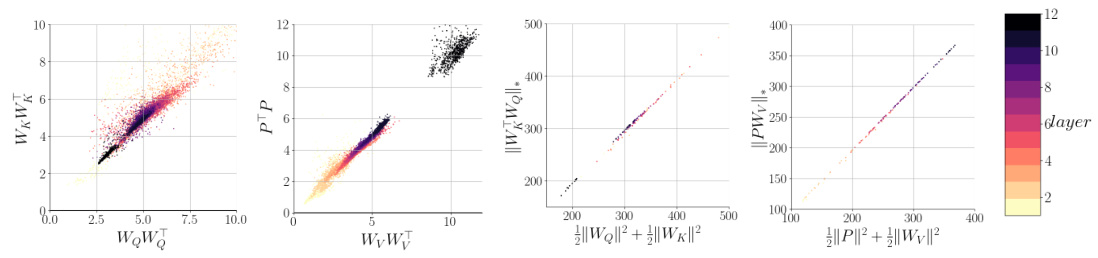

This figure analyzes attention layers in the pretrained LLAMA 2 model to show empirical evidence supporting the theoretical findings of the paper. The plots compare norms of weight matrices (WQ, WK, Wv, P) from the attention mechanism to demonstrate the equivalence between Frobenius and nuclear norms, suggesting the weight decay regularization implicitly induces low-rank attention layers as predicted by the theoretical analysis.

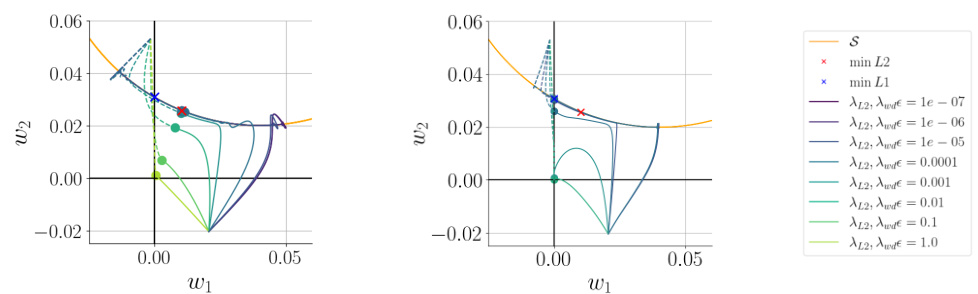

This figure shows the trajectory of two parameters (w1 and w2) during optimization using two different methods: AdamW with decoupled weight decay and Adam with L2-regularization. The left panel shows the case where the parameters are directly optimized. The right panel shows the case where the parameters are factorized as products of two other scalars. In both cases, the optimization path is shown for various regularization strengths. The figure demonstrates that the optimization methods converge to the same point for equivalent regularization strengths, highlighting the relationship between L2 and L1 regularization in the context of parameter factorization.

This figure provides empirical evidence supporting the theoretical findings of the paper. It shows the analysis of attention layers in the pretrained LLAMA 2 model. The plots demonstrate that the Frobenius norm and the nuclear norm of the attention weight matrices are nearly identical, indicating that the weight decay regularization implicitly induces low-rank solutions, as predicted by the theory.

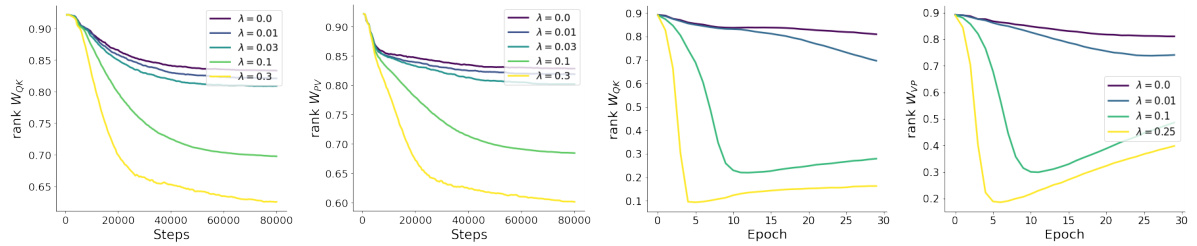

This figure shows the impact of weight decay on the rank of weight matrices in attention layers of autoregressive transformers. The rank of WKWQ and PWv (products of weight matrices in attention layers) is measured across different layers (layer 7 and 9) and various weight decay strengths (λ). The results indicate a strong correlation between weight decay strength and rank reduction, confirming the rank-regularizing effect of weight decay, especially when using the AdamW optimizer.

Full paper#