↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Skeleton-based action recognition, despite progress, struggles with generalizing across different datasets. This is largely due to temporal mismatches—actions are often partially observed in one dataset but fully captured in another. Existing methods, like temporal alignment, are not always effective in bridging this gap, and other domain generalization approaches often rely on handcrafted augmentations. This limits the potential of skeleton action recognition in real-world, diverse settings.

This research tackles this issue using a novel approach. By discovering a “complete action prior,” which represents the inherent tendency of human actions to start from less diverse poses and gradually increase in diversity, the authors developed a “recover-and-resample” augmentation framework. This framework first recovers complete actions from the training data, and then resamples from these full sequences to generate strong augmentations. The approach is evaluated on three large-scale skeleton action datasets, showcasing considerable improvement in cross-dataset generalization performance compared to other methods. This is achieved using a two-step completion process (boundary pose extrapolation, then linear transformations) making it both efficient and effective.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in skeleton-based action recognition due to its novel approach to address the domain generalization problem. It introduces a new augmentation framework that significantly improves accuracy, particularly for datasets with temporal mismatches. This method offers a powerful solution for developing more robust and generalizable action recognition systems, paving the way for advancements in real-world applications such as human-computer interaction and video surveillance. The proposed complete action prior and efficient recovery and resampling methods also provide novel techniques that are highly relevant to the current research trends in self-supervised learning and data augmentation, opening up several avenues for further investigation.

Visual Insights#

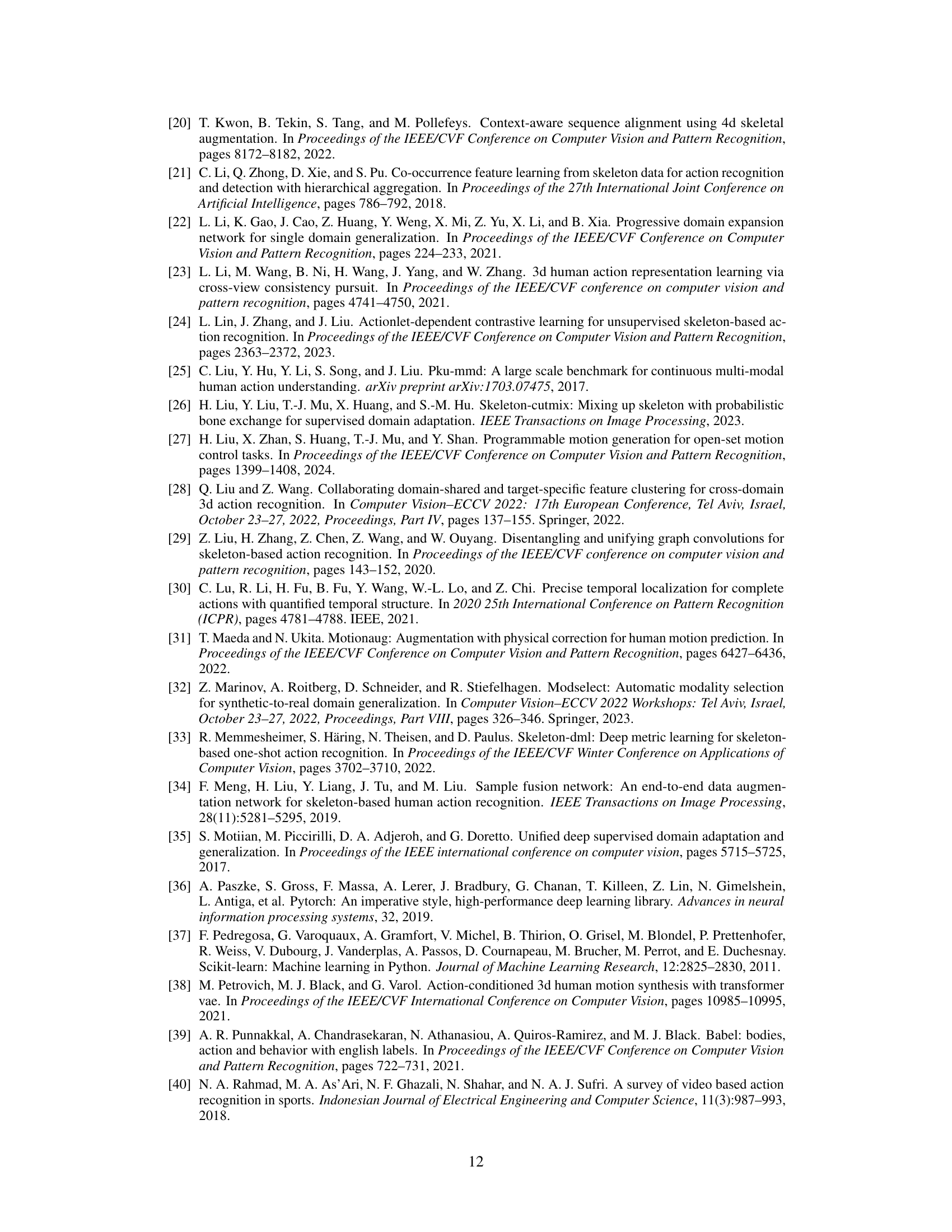

This figure illustrates the core idea of the paper. (a) shows the problem of cross-dataset skeleton action recognition where the temporal length of the same action varies across datasets. (b) introduces the concept of ‘complete action prior’, which states that the feature diversity of human actions in large datasets increases over time, starting from less diverse boundary poses to more diverse poses. (c) presents the proposed ‘recover and resample’ framework, which recovers complete actions from training data using boundary poses and linear temporal transforms and then resamples from these complete actions to generate augmented data for unseen domains.

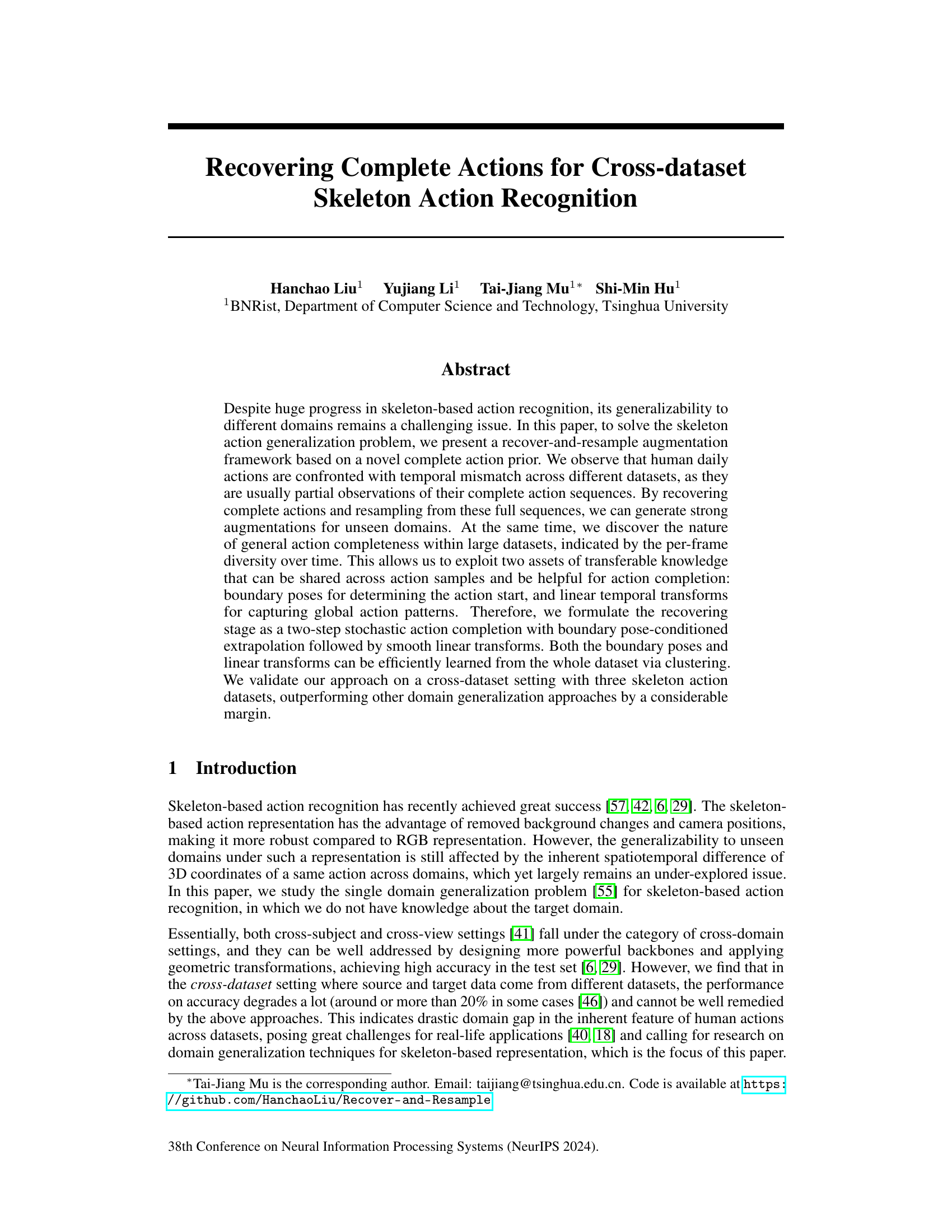

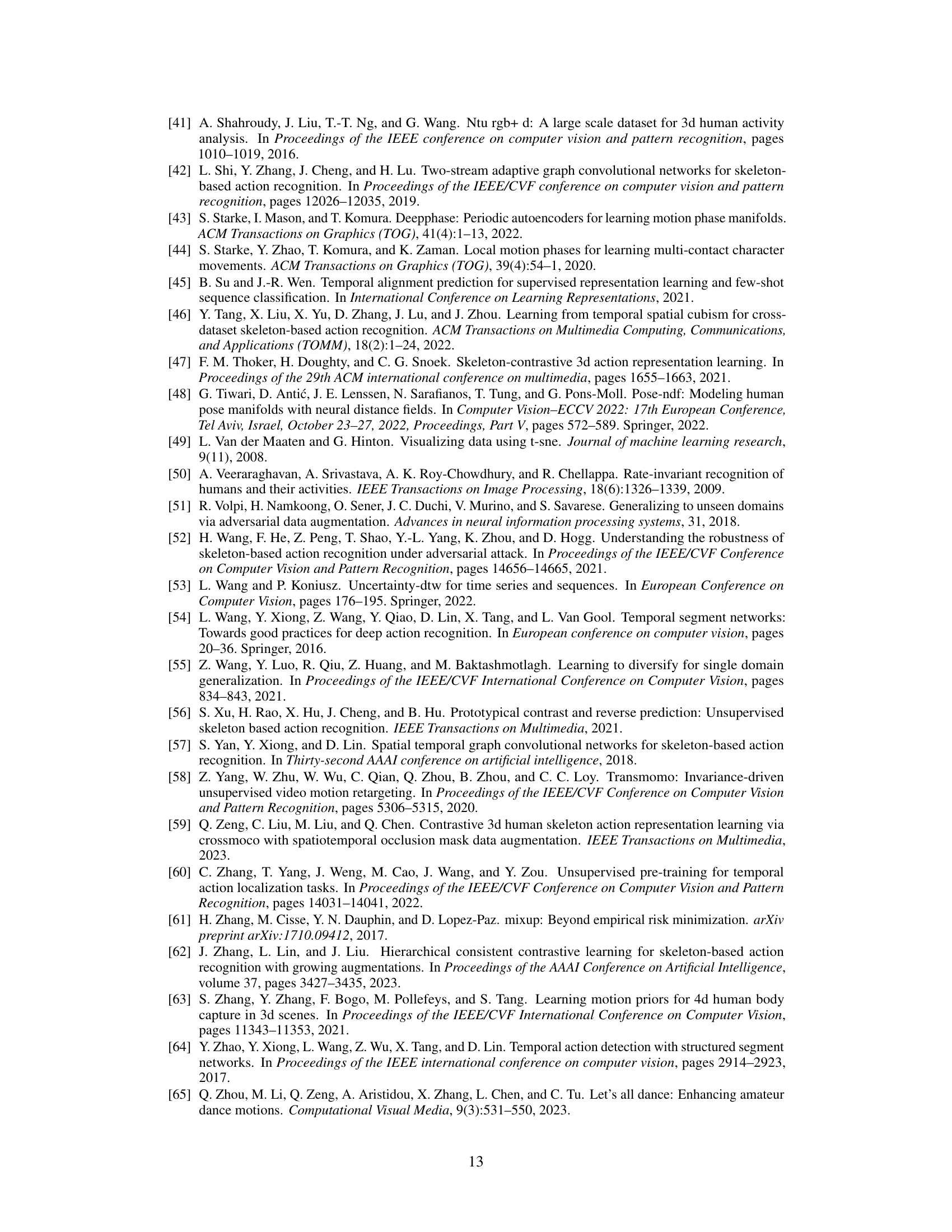

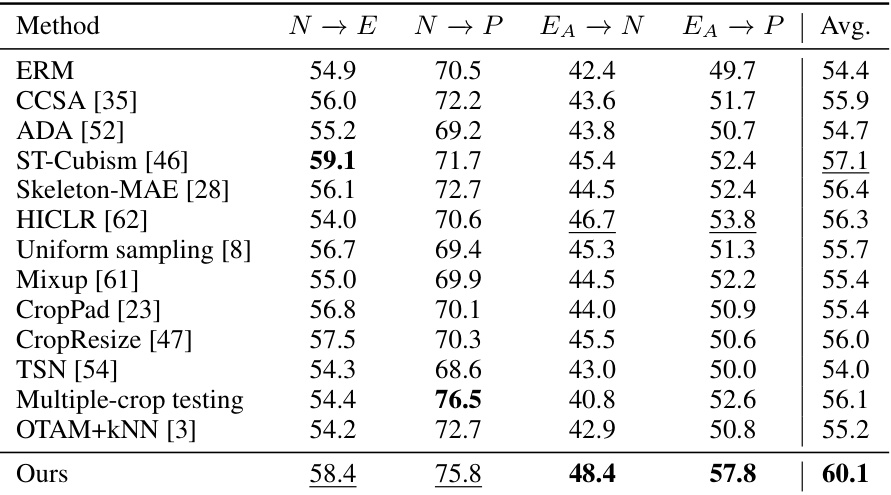

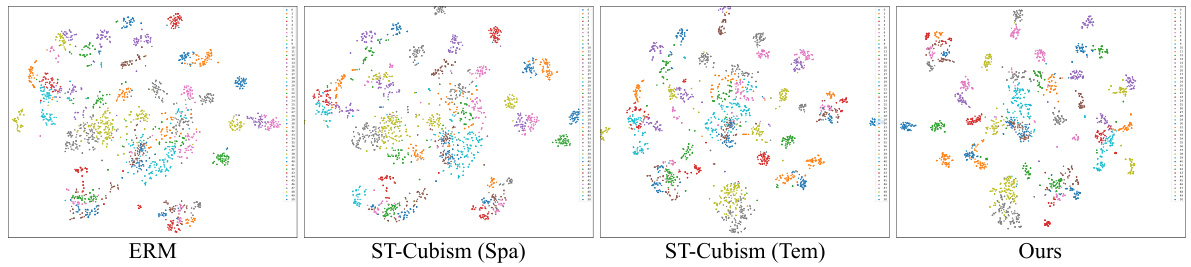

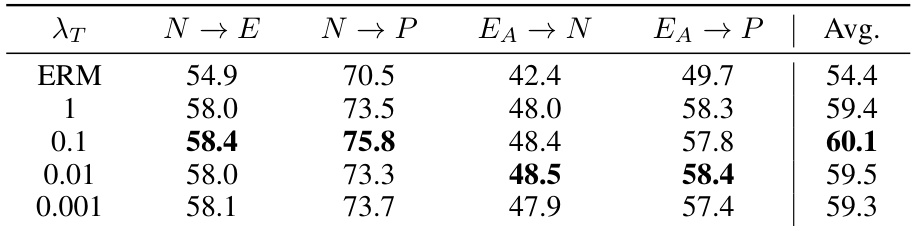

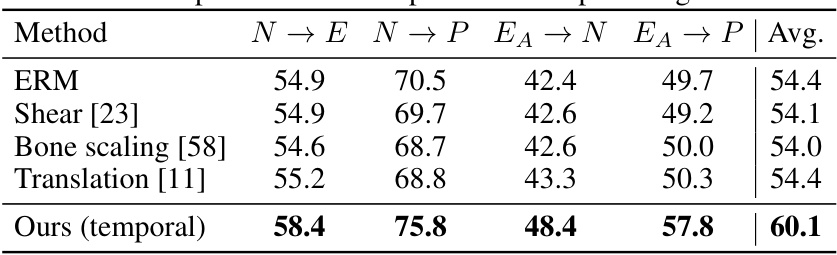

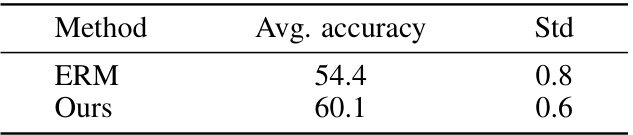

This table compares the performance of the proposed ‘Recover and Resample’ method with various other baseline methods for skeleton-based action recognition across multiple datasets (PKU-MMD, NTU-RGBD, and ETRI-Activity3D). The methods are evaluated on their ability to generalize to unseen datasets, using metrics such as average accuracy across different cross-dataset settings (N→E, N→P, EA→N, EA→P). The table highlights the significant improvement achieved by the proposed method compared to other state-of-the-art techniques.

In-depth insights#

Action Completion#

Action completion, in the context of skeleton-based action recognition, is a crucial technique to address the issue of partial action observations in datasets. Incomplete action sequences, caused by variations in recording methodologies and dataset curation, hinder the training of robust and generalizable models. Action completion aims to generate complete and consistent action sequences from these fragments, thus improving the quality and quantity of training data. This is typically achieved by extrapolating the available portions using learned priors, or by synthesizing missing segments. This method is particularly important for cross-dataset generalization where the temporal misalignment of actions is often substantial. The effectiveness of action completion hinges on the ability to accurately estimate the missing parts, which requires modeling both fine-grained details (e.g., joint movements) and coarse-grained patterns (e.g., temporal dynamics) of human actions. The success of this approach also depends heavily on the quality and diversity of the training data used to learn the action completion model, highlighting the importance of data augmentation techniques.

Cross-Domain Aug#

A heading titled ‘Cross-Domain Aug’ in a research paper likely details augmentation strategies designed to enhance model generalization across diverse data domains. The core idea revolves around bridging the gap between training and testing data distributions, a crucial challenge in machine learning. Effective cross-domain augmentation techniques should generate synthetic data that resembles the characteristics of unseen domains, improving model robustness and preventing overfitting to the training set. This could involve various methods, such as domain adaptation, data synthesis, or transfer learning. The augmentation’s success depends heavily on its ability to capture the essential features and variations of different domains while avoiding the introduction of spurious correlations. Careful consideration of domain-specific biases is essential; augmentations should not introduce or exacerbate these biases. A successful approach would not only increase the diversity of training data but also improve the model’s ability to learn generalizable, domain-invariant features. The paper’s discussion of ‘Cross-Domain Aug’ should meticulously examine the selected techniques, providing empirical evidence to support their effectiveness and detailing any limitations or potential drawbacks.

Temporal Mismatch#

Temporal mismatch in the context of skeleton-based action recognition refers to the inconsistencies in the temporal alignment of actions across different datasets. This is a significant challenge because it hinders the ability of models trained on one dataset to generalize to others. Different datasets might capture actions with varying lengths or speeds, influenced by factors such as recording equipment, individual performance styles, and annotation criteria. This inconsistency prevents direct comparison of action sequences and negatively impacts the model’s ability to learn robust and transferable features. Addressing this mismatch is crucial for improving the generalizability of action recognition systems and enabling them to perform well in real-world scenarios where diverse action capture methods are employed. Techniques like dynamic time warping or data augmentation strategies that artificially adjust temporal characteristics can partially alleviate the problem, but a complete solution likely requires developing models that are inherently more robust to temporal variations or that learn to represent actions in a temporal-invariant manner. This could involve focusing on the relationships between skeletal keypoints irrespective of speed or duration, or by explicitly modeling temporal dynamics as a separate aspect of action recognition.

Stochastic Models#

A section on ‘Stochastic Models’ in a research paper would likely explore the use of probability and randomness to represent and analyze phenomena. This approach is particularly valuable when dealing with complex systems exhibiting inherent uncertainty or variability. The discussion might cover various model types, such as Markov chains for sequential processes, hidden Markov models for situations where underlying states are not directly observable, or Bayesian networks for representing probabilistic relationships between variables. Model selection would be a crucial aspect, comparing the suitability of different stochastic models based on factors like data fit, computational complexity, and interpretability. The section should also address parameter estimation techniques, outlining methods to learn model parameters from data, and potentially discuss challenges associated with model validation and the quantification of uncertainty in predictions.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore more sophisticated temporal modeling techniques beyond linear transformations, perhaps leveraging transformers or recurrent neural networks to capture complex, non-linear relationships in human actions. Improving robustness to noisy or incomplete data is crucial; methods incorporating uncertainty estimation or data augmentation strategies are needed. Cross-dataset generalization remains a challenge; more advanced domain adaptation techniques, possibly involving meta-learning or transfer learning, could be investigated. Furthermore, extending the approach to more complex action datasets with diverse viewpoints, activities, and environmental factors will be important to demonstrate broader applicability. Finally, exploring the potential for incorporating other modalities (e.g., RGB video, inertial sensors) could improve action recognition performance, particularly in challenging scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

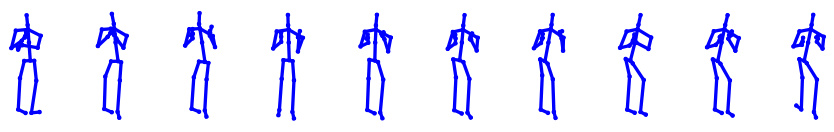

This figure illustrates the recover-and-resample augmentation framework. It shows how the system learns boundary poses and linear transforms from the training data. Then, for a given input skeleton action, it uses boundary pose-conditioned extrapolation to recover a complete action. Finally, it applies a learned linear transformation and resamples the data to augment the training set. The process aims to generate strong augmentations for unseen domains by addressing temporal mismatch in action sequences.

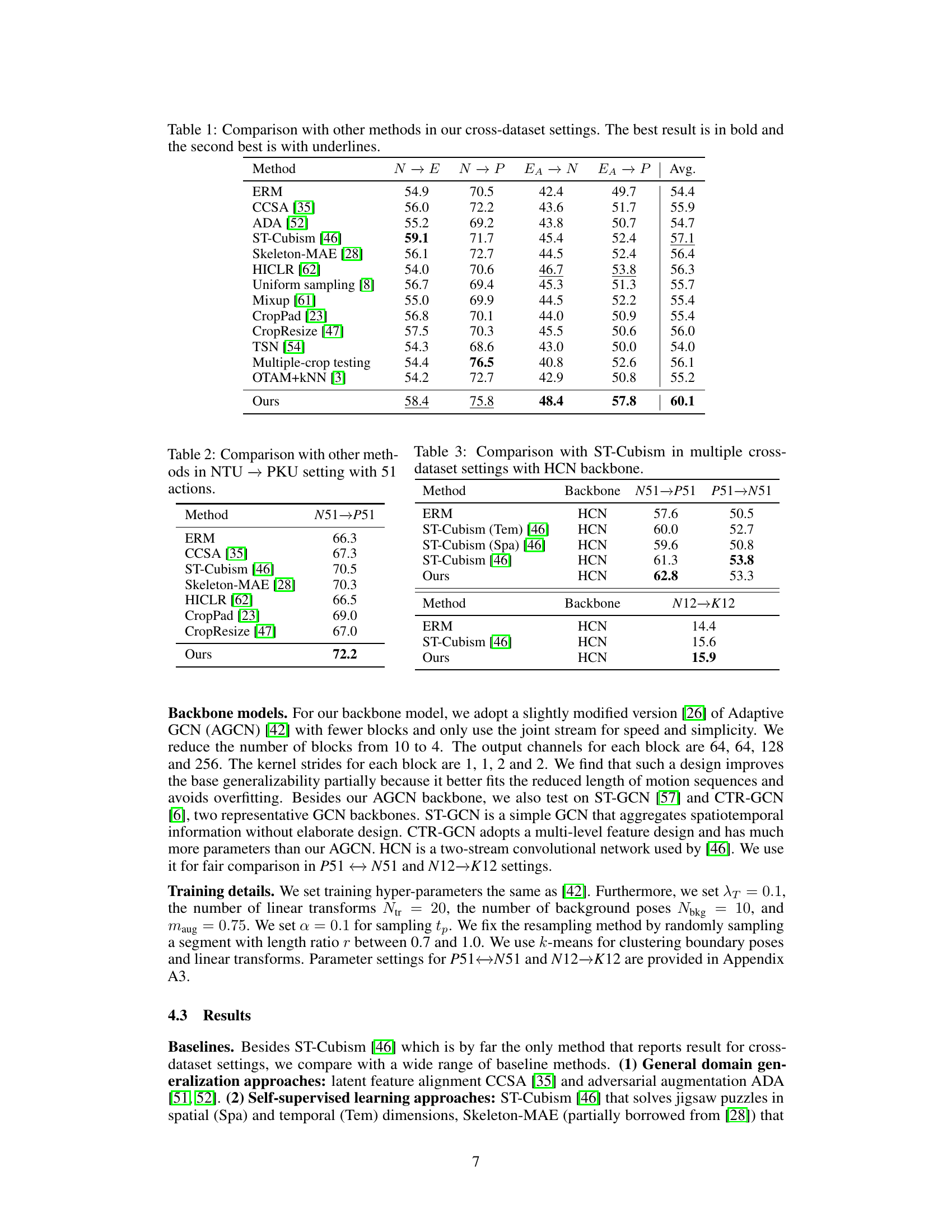

This figure visualizes the linear transform matrices obtained through clustering. The matrices represent learned transformations applied to skeleton action sequences during the augmentation process. These transformations capture common structural temporal patterns in the data, such as shifting and scaling. The visualizations help illustrate how these learned transforms contribute to recovering and augmenting incomplete action sequences in the cross-dataset setting.

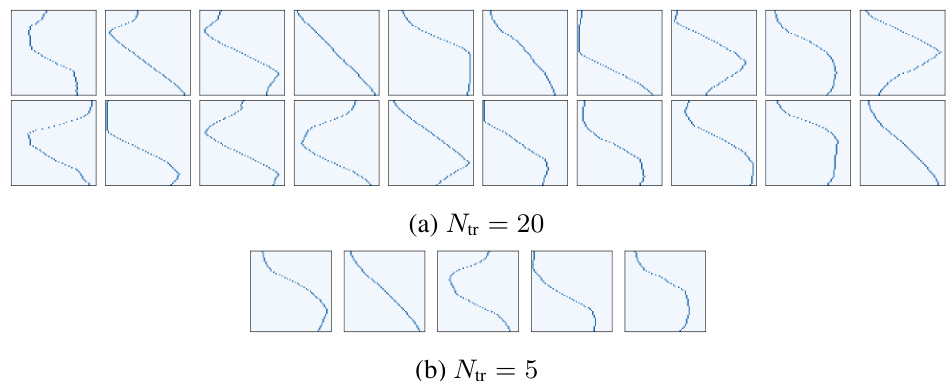

This figure visualizes some examples of linear transform matrices (Wi) learned via clustering using training sets N and EA. Each matrix represents a linear transformation that maps partial sequences to full sequences, which are learned from the training data by reconstructing full sequences from their trimmed segments. These matrices capture common structural temporal patterns (e.g. shifting, scaling, symmetry) inherent in human actions. The visualization helps to understand the learned transform patterns and how they are used for generating augmentations.

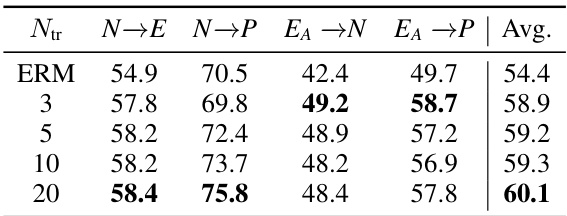

This figure visualizes the clustered linear transform matrices obtained using the training set N for two different numbers of clusters (Ntr): 20 and 5. Each subfigure shows a set of learned transform matrices, represented as images. Comparing the subfigures, we can observe that using more clusters (Ntr=20) leads to a greater diversity of learned transformations, which is essential for capturing a wider range of temporal patterns in human actions.

This figure visualizes the learned linear transform matrices obtained through clustering on training datasets N and EA. These matrices are a key component of the proposed ‘Recover and Resample’ augmentation framework. They represent learned patterns of temporal transformations applied to skeleton action sequences during the action completion process. The visualization likely shows the learned matrices as images, each representing a distinct transform learned from the data.

This figure visualizes the learned linear transform matrices obtained through clustering. The matrices, represented as images, are learned from the training data of two different datasets, N and EA. Each matrix represents a transformation applied to skeleton action sequences to recover complete actions. The visualization helps understand the learned transformation patterns.

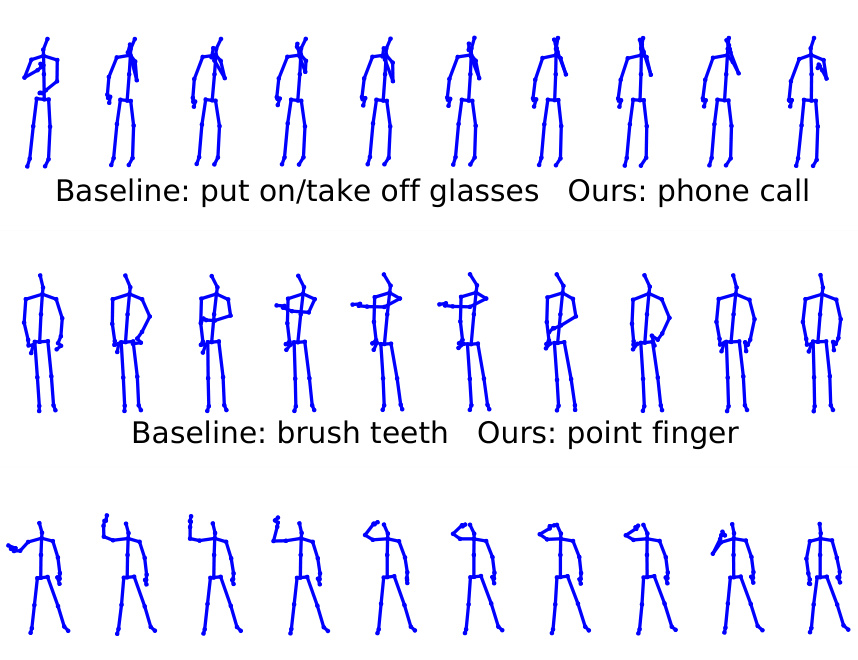

This figure shows qualitative examples of improved action recognition using the proposed ‘recover-and-resample’ augmentation method compared to the baseline (Empirical Risk Minimization or ERM). The images visually demonstrate that the new method can improve the accuracy of action recognition, particularly for actions where only partial sequences are available. The top row shows how the baseline incorrectly identifies the action as ‘put on/take off glasses’, while the proposed method correctly identifies it as ‘phone call’. Similarly, the other rows show misclassifications by the baseline which are corrected by the proposed method.

More on tables

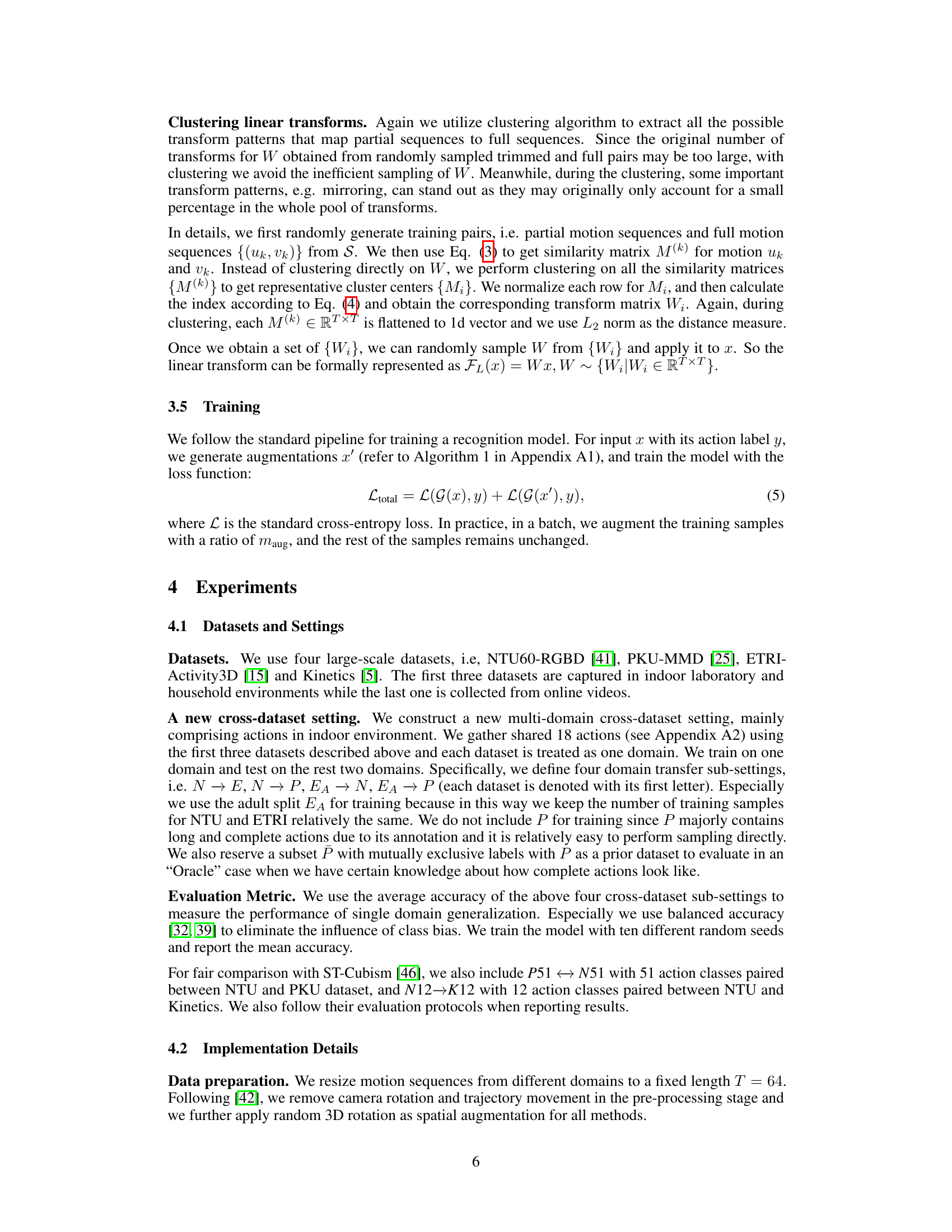

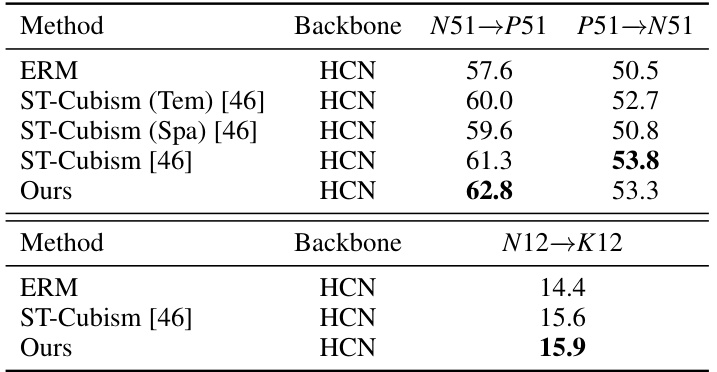

This table compares the performance of the proposed method with other state-of-the-art methods on the NTU → PKU cross-dataset setting, which involves 51 action classes. It shows the accuracy achieved by each method, highlighting the superior performance of the proposed approach.

This table compares the proposed method’s performance with other state-of-the-art methods on the NTU → PKU cross-dataset setting, using 51 action classes. It shows the accuracy achieved by different methods, highlighting the improved performance of the proposed approach compared to baselines in a challenging cross-dataset scenario.

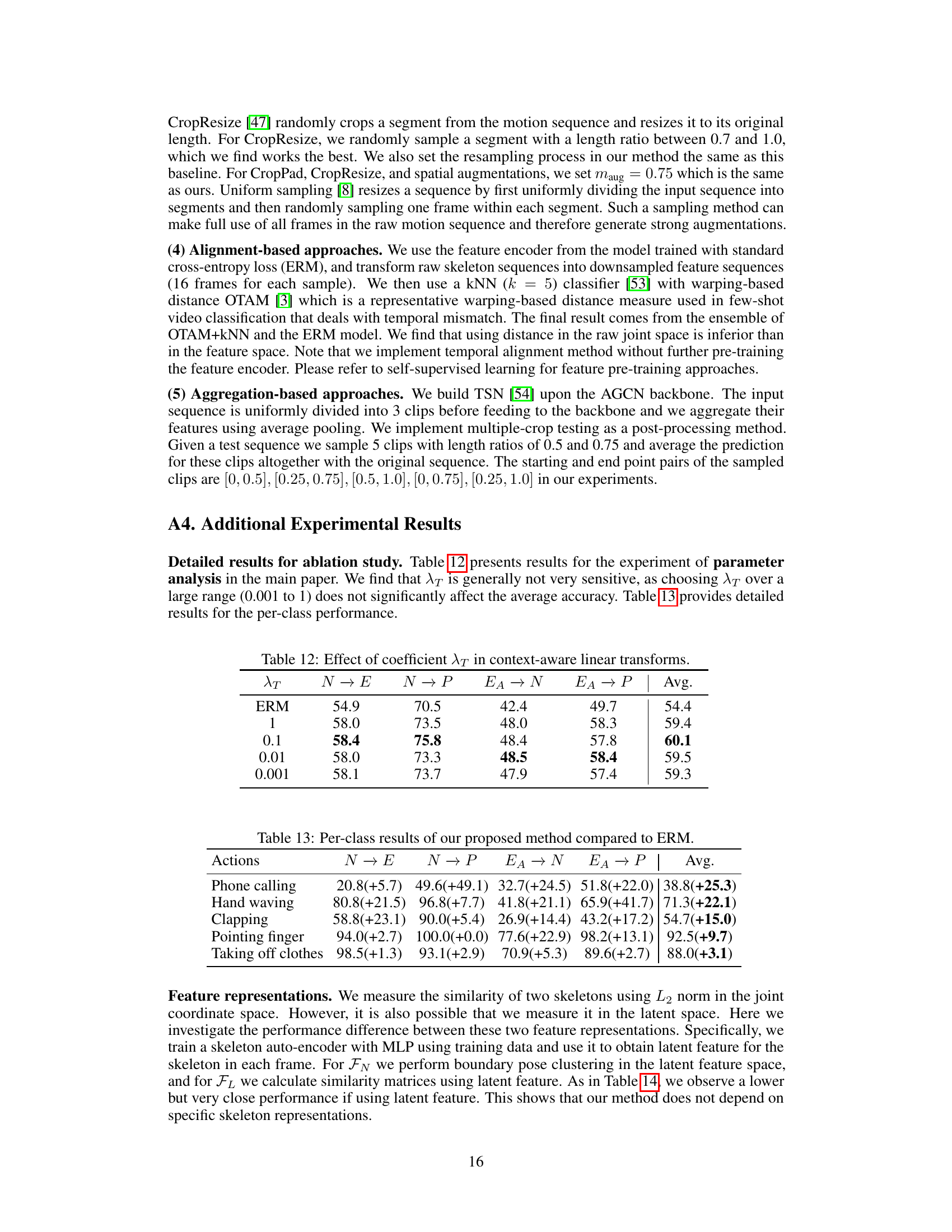

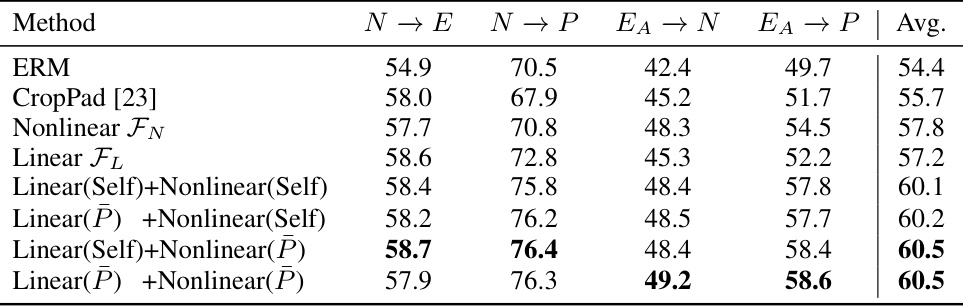

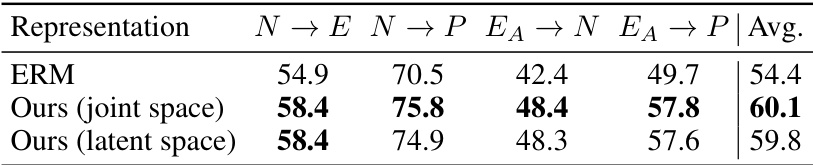

This table presents the ablation study of different components of the proposed Recover and Resample framework. It shows the impact of using only the nonlinear function (FN), only the linear transform (FL), and combinations of these, using either the training dataset (Self) or a separate dataset (P) to obtain boundary poses and linear transforms. The results highlight the contribution of each module and the effectiveness of using a complete action prior from the P dataset.

This table compares the performance of the proposed ‘Recover and Resample’ method against various baselines on three cross-dataset settings for skeleton-based action recognition. The settings involve training on a single dataset and testing on the other two. The table shows the average accuracy across different datasets, highlighting the superior performance of the proposed method.

This table presents the ablation study results of the proposed method. It shows the effects of each component (nonlinear transform, linear transform) and using different prior datasets on the performance (average accuracy across four cross-dataset settings). The resampling step is used in all experiments.

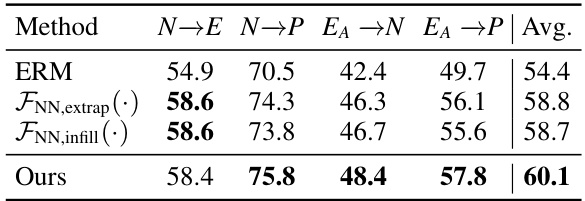

This table compares the performance of three different learning approaches for action completion against the proposed method. The three methods are extrapolating a motion sequence (FNN, extrap), infilling missing frames in a motion sequence (FNN, infill), and the proposed recover-and-resample method. The results are evaluated across four cross-dataset settings (N→E, N→P, EA→N, EA→P), and the average accuracy is reported for each method. This shows the effectiveness of combining the boundary-conditioned extrapolation and linear transform in the proposed approach.

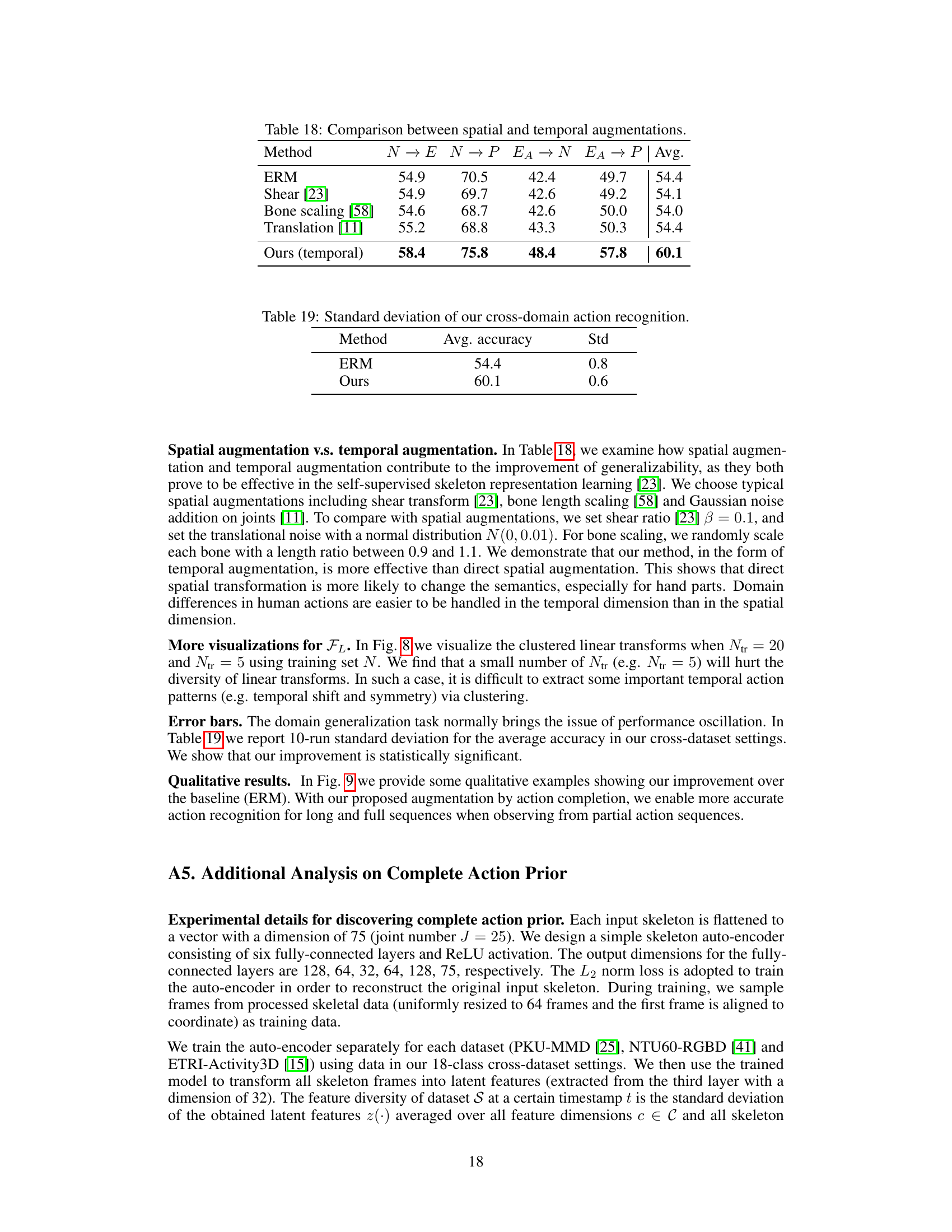

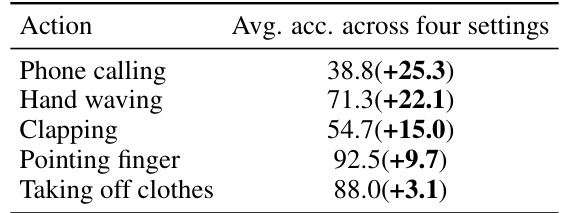

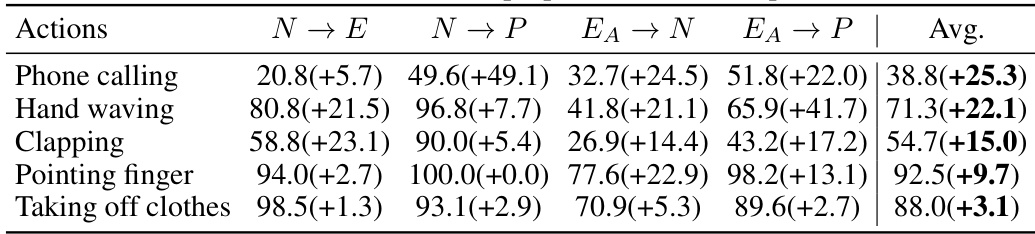

This table presents the per-class accuracy improvement achieved by the proposed method compared to the baseline method (ERM) across four different cross-dataset settings. The improvements are shown as percentage increases, providing a detailed view of the method’s effectiveness on specific actions. Actions with larger improvements are likely those that benefit most from the method’s approach to recovering complete action sequences.

This table compares the performance of the proposed method with several other baseline methods across four different cross-dataset settings (N→E, N→P, EA→N, EA→P). The average accuracy across all four settings is shown, highlighting the superior performance of the proposed ‘Recover and Resample’ augmentation framework compared to various baselines, such as ERM, ADA, ST-Cubism, and others. The best result for each setting is shown in bold, and the second-best is underlined.

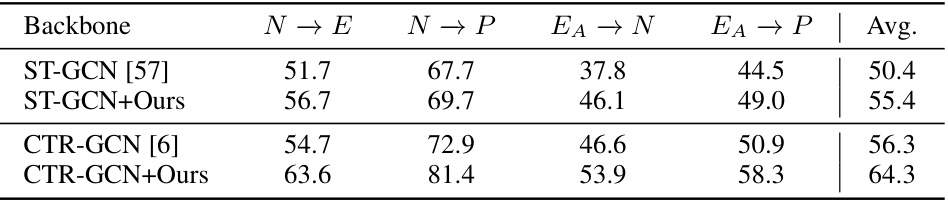

This table shows the average accuracy of the proposed method on different backbones (ST-GCN and CTR-GCN) across four cross-dataset settings (N→E, N→P, EA→N, EA→P). It compares the performance of the base backbones against the backbones when combined with the proposed augmentation method. The results highlight the improvement in accuracy achieved by incorporating the proposed method regardless of the backbone used.

This table lists the 18 action labels that are commonly shared among the three large-scale datasets (NTU60-RGBD, PKU-MMD, and ETRI-Activity3D) used in the cross-dataset experiments of the paper. These actions were selected for their presence across the datasets and suitability for evaluating the proposed method in a cross-domain scenario. The actions are categorized to help in understanding.

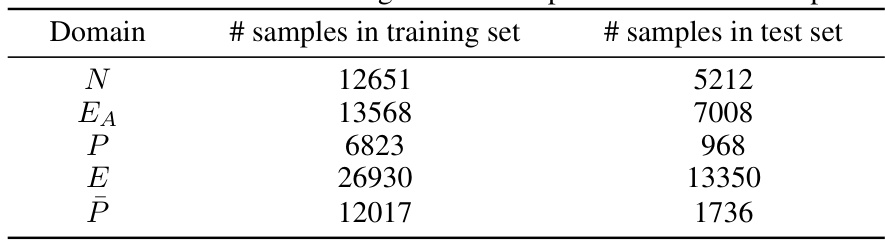

This table presents the number of samples used for training and testing in each of the five datasets used in the cross-dataset experiments. The datasets are denoted by their first letter: N for NTU60-RGBD, EA for ETRI-Activity3D (adult split), P for PKU-MMD, and E for ETRI-Activity3D. The adult split of ETRI was used to balance the training set size across different domains.

This table compares the performance of the proposed method with other baseline methods across four different cross-dataset settings (N→E, N→P, EA→N, EA→P). The best and second-best results for each setting are highlighted in bold and underlined, respectively. The average accuracy across all four settings is also provided. The methods include ERM (Empirical Risk Minimization), several domain generalization and self-supervised learning approaches, along with various augmentation methods.

This table presents a per-class breakdown of the accuracy improvements achieved by the proposed method over the baseline ERM (Empirical Risk Minimization) across four different cross-dataset settings (N→E, N→P, EA→N, EA→P). Each row represents a specific action, showing the improvement in accuracy for that action across the four settings and an average improvement across all settings. The values indicate the improvement in percentage points.

This table compares the performance of the proposed method against various baselines on three cross-dataset settings. The settings evaluate the model’s ability to generalize to unseen datasets by training on one dataset and testing on the other two. The table shows that the proposed augmentation method significantly improves performance, outperforming the other methods by a considerable margin. The best performing method for each setting is bolded, and the second best is underlined.

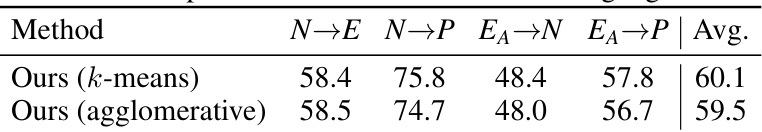

This table compares the performance of the proposed method using two different clustering algorithms: k-means and agglomerative. The results are presented as the average accuracy across four different cross-dataset settings (N→E, N→P, EA→N, EA→P). This allows for an evaluation of how sensitive the method is to the choice of clustering algorithm.

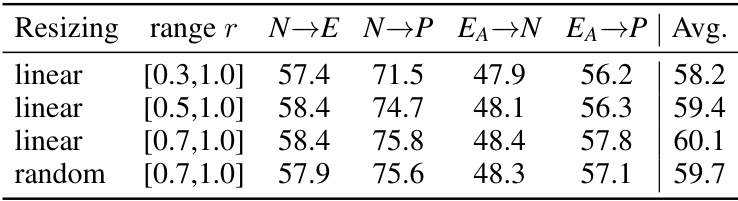

This table presents the result of an ablation study on the resampling stage of the proposed method. Four different resampling strategies were compared: linear resizing with ranges [0.3, 1.0], [0.5, 1.0], [0.7, 1.0], and random resizing with a range of [0.7, 1.0]. The average accuracy across four cross-dataset settings (N→E, N→P, EA→N, EA→P) was calculated for each strategy. The results show that linear resizing with a range of [0.7, 1.0] yields the best performance, indicating that sampling longer and more complete segments is crucial for effective data augmentation.

This table compares the performance of the proposed method against various baseline methods across three different cross-dataset settings for skeleton-based action recognition. The table shows the average accuracy achieved by each method on unseen datasets. The best and second best performances in each setting are highlighted.

This table compares the performance of the proposed ‘Recover and Resample’ method against several baselines on a cross-dataset action recognition task. The task involves training a model on one dataset (source domain) and testing it on two other unseen datasets (target domains). The table shows the average accuracy across four different cross-dataset settings. The baselines include ERM (Empirical Risk Minimization), several domain generalization methods (CCSA, ADA, ST-Cubism, Skeleton-MAE, HICLR), and several augmentation methods (uniform sampling, Mixup, CropPad, CropResize, TSN, multiple-crop testing, OTAM+KNN). The results demonstrate that the proposed method significantly outperforms all baselines.

This table compares the proposed method with various other baseline methods across four different cross-dataset settings (N→E, N→P, EA→N, EA→P). The average accuracy across all settings is reported for each method. The best performing method is highlighted in bold, and the second best is underlined. The table shows the relative performance improvements of the proposed method compared to existing approaches in addressing cross-dataset generalization problems in skeleton-based action recognition.

Full paper#