TL;DR#

Protein interface prediction (PIP) is crucial for drug discovery, but current methods struggle with the flexibility of proteins upon binding. This leads to poor generalization, as models trained on bound structures perform poorly on unbound ones. The paper introduces ATProt, a novel adversarial training framework.

ATProt treats protein flexibility as an adversarial attack, aiming to make protein representations robust against this attack. It uses stability-regularized graph neural networks to learn stable representations regardless of the protein’s conformational state. The experiments show that ATProt consistently outperforms existing methods in PIP, exhibiting strong generalization ability even when tested with structures predicted by other models such as ESMFold and AlphaFold2. This addresses the issue of bound-unbound structure mismatch in PIP.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses a critical challenge in protein interface prediction: the inability of existing methods to generalize well due to protein flexibility. By introducing an adversarial training framework (ATProt), it improves prediction accuracy, particularly when dealing with unbound structures. This work is relevant to current research trends in deep learning for protein structure prediction and opens avenues for improving model robustness and generalization across various structural prediction models. The proposed method also demonstrates broad applicability, even when applied to structure prediction models like ESMFold and AlphaFold2.

Visual Insights#

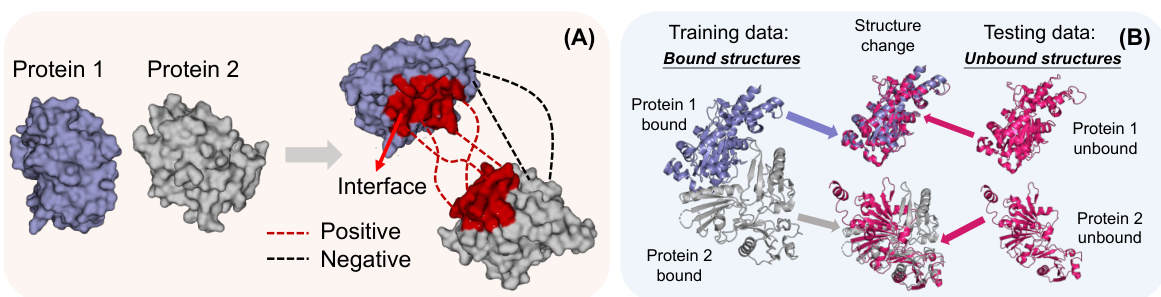

🔼 This figure illustrates the protein interface prediction (PIP) task. Panel (A) shows a schematic of two proteins interacting, highlighting the interface region where residues from different proteins interact. Positive interactions are shown in red, and negative interactions are shown in dashed red lines. Panel (B) highlights the core challenge of PIP: training is typically performed using bound protein structures (after binding), while testing must be performed on unbound structures (before binding). This mismatch between training and testing data, due to conformational changes in proteins upon binding, poses a significant challenge for accurate PIP.

read the caption

Figure 1: (A). The task illustration. PIP involves predicting if there is an interaction between two residues from different proteins. (B). The task challenge. During training, the input consists of bound structures of two proteins. However, for testing, one can only access their unbound structures.

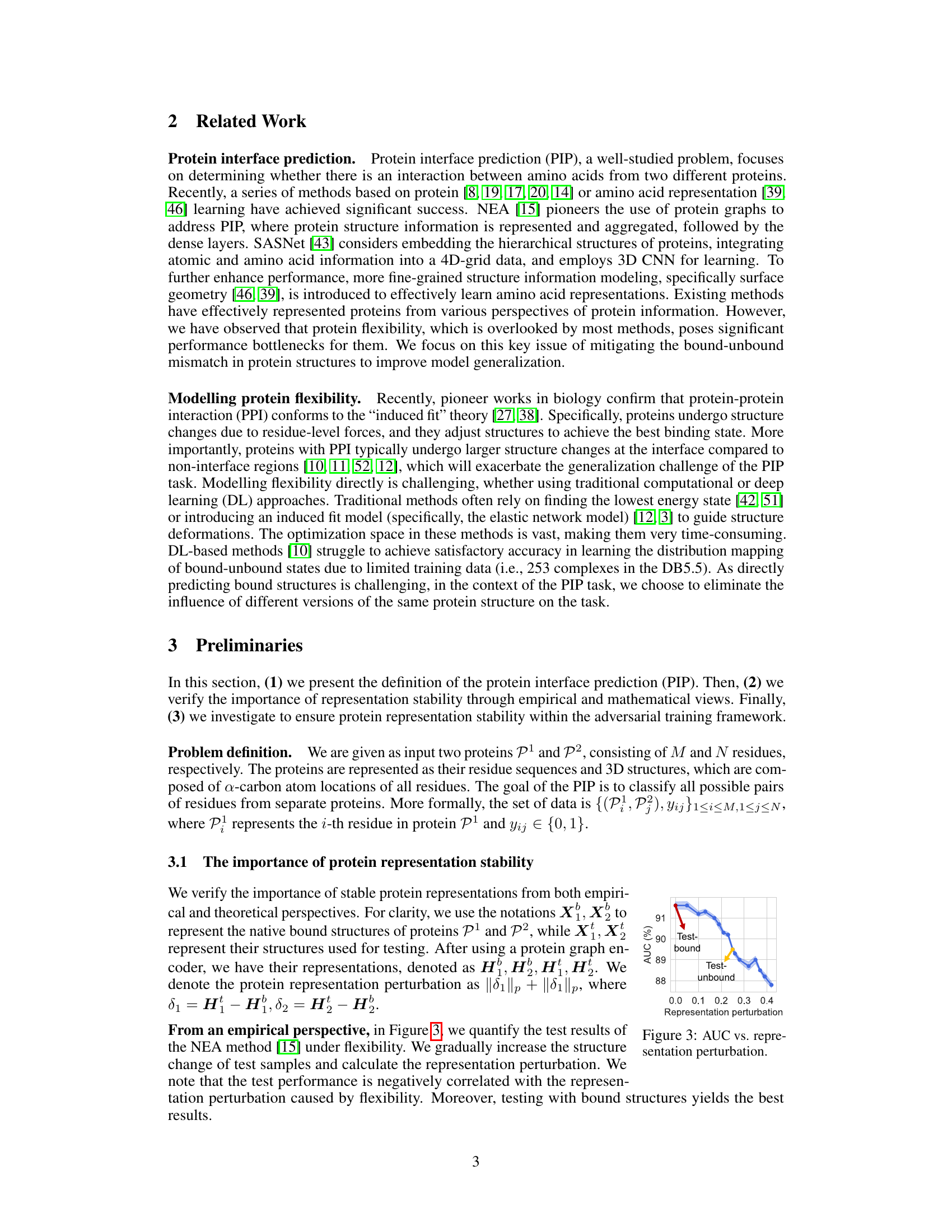

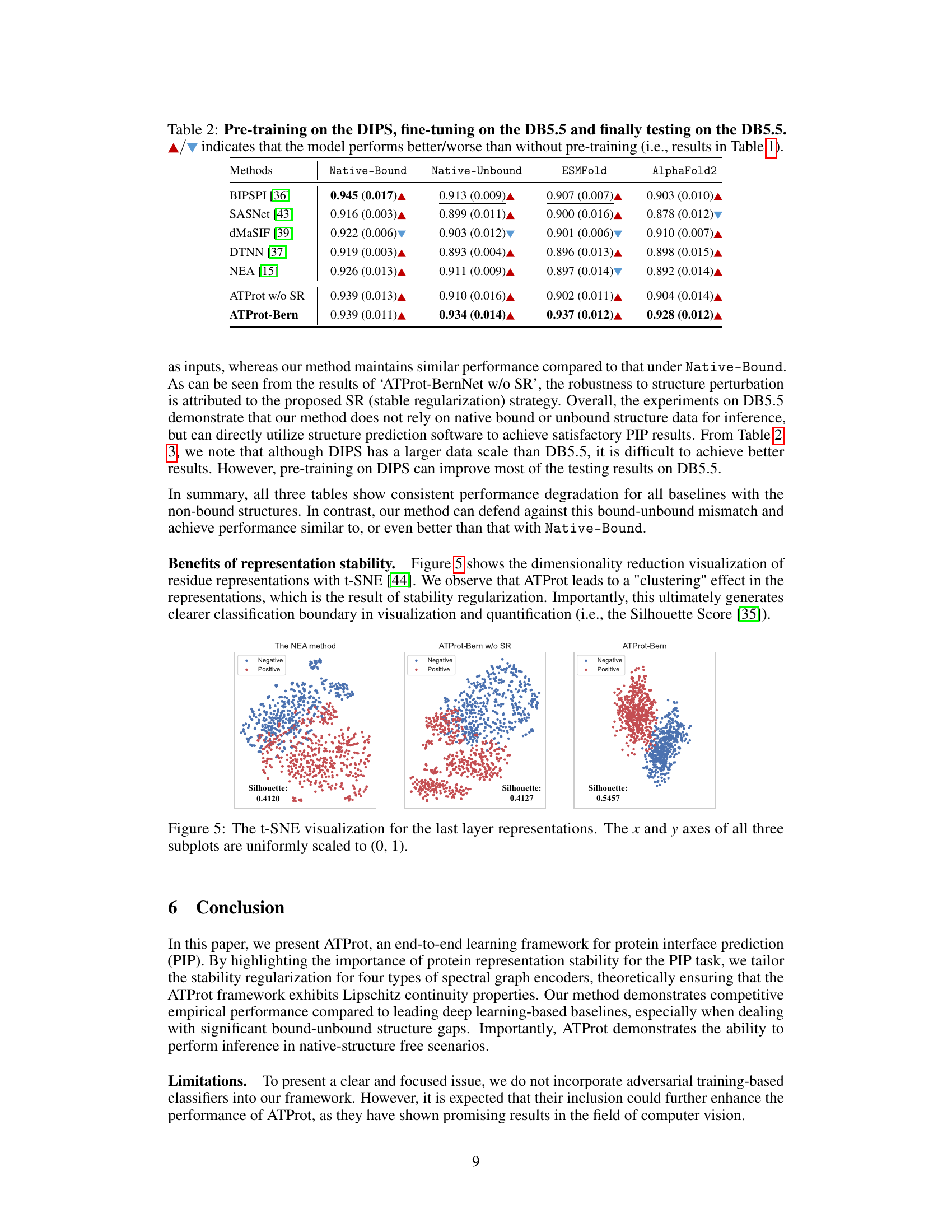

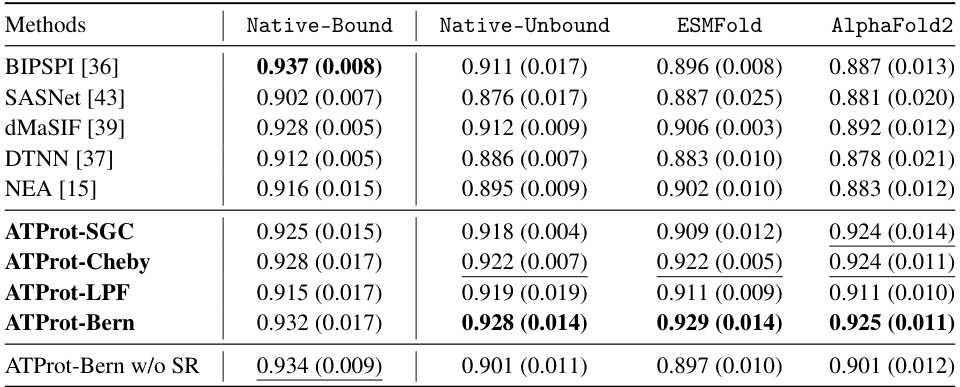

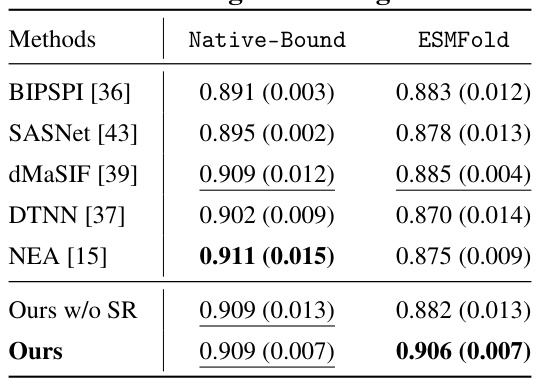

🔼 This table presents the results of training and testing on the DB5.5 dataset for protein interface prediction (PIP). Multiple methods (including baselines and the proposed ATProt with various configurations) are compared using the median AUC (MedAUC) score. The table shows the MedAUC for four testing conditions: Native-Bound, Native-Unbound, ESMFold, and AlphaFold2, representing different structural inputs for the test set. The best and second-best results for each condition are highlighted.

read the caption

Table 1: Training and testing on the DB5.5. Mean and standard deviation values of the MedAUC scores of all baselines, computed from three random seeds. The best performance is in bold and the second best one is underlined. 'SR' means the proposed stable regularization Ls.

In-depth insights#

Stable Protein Reps#

The concept of “Stable Protein Representations” is crucial for accurate and reliable protein interface prediction (PIP). Protein flexibility, a major challenge in PIP, leads to unstable representations that hinder the generalizability of predictive models. Methods focused on achieving stable representations aim to mitigate this by ensuring that the model outputs similar representations for the same protein, regardless of its conformational state (e.g., bound vs. unbound). This stability is vital because it allows the model to consistently learn the underlying features crucial for PIP, irrespective of the protein’s flexibility. Adversarial training is a prominent technique used to achieve stable representations. It treats protein flexibility as an adversarial attack and trains the model to be robust against such attacks, forcing the model to learn stable and invariant features. Achieving stable protein representations is a key advancement in PIP because it leads to more accurate and robust predictions, even when the input structures are diverse and might not reflect the protein’s native binding state. The development of novel protein representation methods incorporating stability is an active area of research, with significant implications for various applications leveraging protein structure information.

ATProt Framework#

The ATProt framework is presented as a novel approach to protein interface prediction (PIP), focusing on improving the robustness of protein representations against the challenges of protein flexibility. It does this by introducing an adversarial training methodology. The core idea is to treat protein flexibility as an adversarial attack on the model and to train the model to be robust to such attacks. ATProt incorporates stability-regularized graph neural networks, which aim to learn stable and consistent representations of protein structures regardless of minor conformational changes. This approach is theoretically grounded, ensuring stability and generalizability. Key to the framework is a focus on using differentiable regularizations, particularly for Bernstein-based spectral filters, to guarantee Lipschitz continuity in the protein representation. The framework demonstrates effectiveness across several benchmark datasets and shows consistent improvement over existing methods, indicating the potential of the ATProt framework in enhancing the accuracy and reliability of protein interface prediction.

Adversarial Training#

Adversarial training, in the context of protein interface prediction, offers a novel approach to enhance model robustness. By treating protein flexibility as an adversarial attack, the method aims to improve generalization. The core idea is to train the model to produce stable representations of protein structures, even when subjected to variations caused by conformational changes. This is achieved by incorporating adversarial regularizations into the training process, effectively defending against the ‘attack’ of flexibility. The approach theoretically guarantees protein representation stability and empirically shows improved performance for protein interface prediction, especially when testing on structures generated by predictive models like AlphaFold2 and ESMFold. This strategy is particularly valuable given the difficulty of obtaining large, diverse datasets of bound protein structures and the inherent flexibility of proteins in biological interactions. The success of adversarial training in this application highlights its potential for addressing data limitations and improving the reliability of AI predictions in related fields.

PIP Robustness#

The concept of “PIP Robustness” in the context of protein interface prediction (PIP) centers on a model’s ability to generalize accurately despite variations in protein structures. Flexibility within proteins, particularly at the interface upon binding, presents a significant challenge to existing data-driven methods. These methods often train on bound (post-binding) structures but test on unbound (pre-binding) structures, creating a discrepancy. A robust PIP model should provide consistent predictions regardless of whether it’s presented with bound or unbound conformations of a protein pair, demonstrating resilience to this inherent structural variability. Achieving robustness can involve strategies like adversarial training, where the model is trained to withstand perturbations or “attacks” designed to mimic flexibility, thereby improving generalization and reliability. Ultimately, improving PIP robustness is key to developing more accurate and reliable tools for drug discovery and related applications, where understanding protein interactions is paramount.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the robustness of protein representation models to various structural perturbations beyond flexibility is crucial. This might involve incorporating more sophisticated physical properties into the graph representation, or developing novel adversarial training strategies that handle a wider variety of attacks. Another area of focus should be on exploring larger and more diverse datasets. The current training datasets are relatively small and biased, which limits generalizability. Developing techniques to integrate experimental data, such as cryo-EM structures or mutagenesis studies, would significantly enhance the accuracy and reliability of the predictions. Furthermore, integrating ATProt with other protein structure prediction models (like AlphaFold2) as a post-processing step could improve the overall accuracy of interface prediction. Finally, extending the framework beyond protein-protein interfaces to other types of biomolecular interactions, such as protein-ligand or protein-DNA interactions, presents a significant opportunity to improve broader drug discovery efforts.

More visual insights#

More on figures

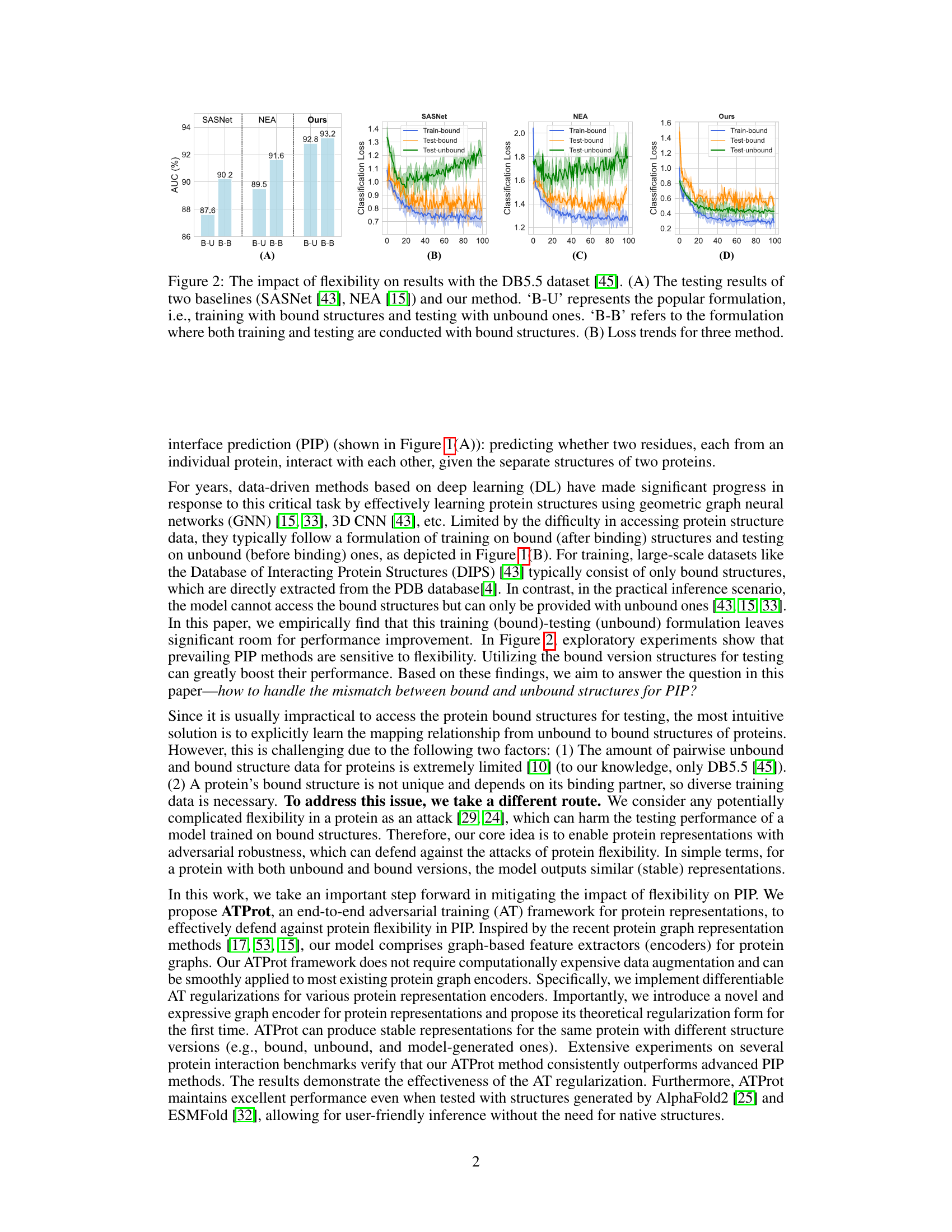

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effect of protein flexibility on the performance of protein interface prediction (PIP) models. Panel (A) shows the testing AUC scores for three methods (SASNet, NEA, and the proposed method, ATProt) under two different scenarios: B-U (training on bound structures, testing on unbound structures) and B-B (training and testing on bound structures). The results highlight the significant performance drop when testing with unbound structures. Panel (B) displays the training loss curves for the three methods, further illustrating the challenges posed by protein flexibility. The curves clearly show that training with only bound structures (B-B) leads to lower training loss compared to the standard B-U setting.

read the caption

Figure 2: The impact of flexibility on results with the DB5.5 dataset [45]. (A) The testing results of two baselines (SASNet [43], NEA [15]) and our method. ‘B-U' represents the popular formulation, i.e., training with bound structures and testing with unbound ones. 'B-B' refers to the formulation where both training and testing are conducted with bound structures. (B) Loss trends for three methods.

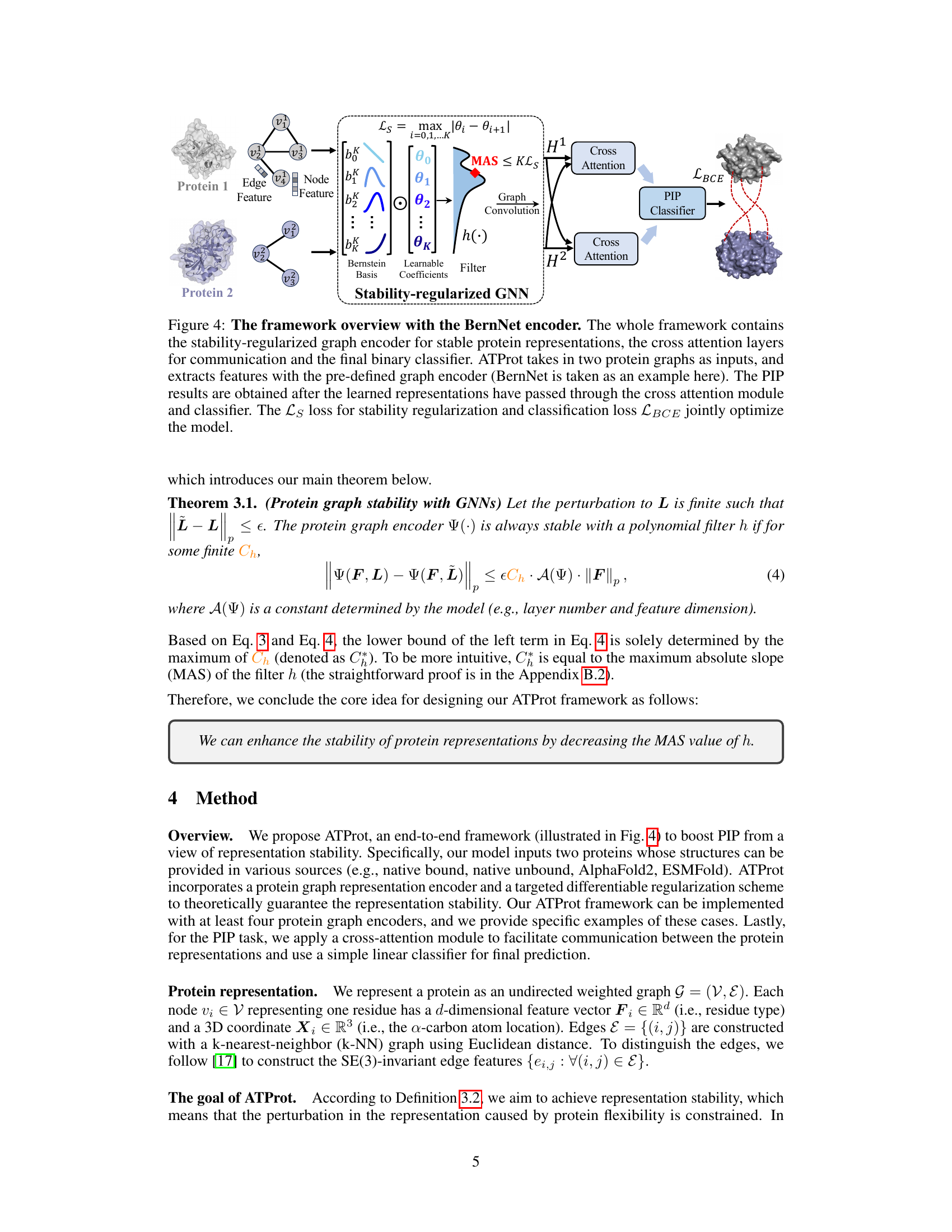

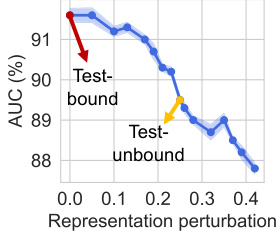

🔼 This figure shows the relationship between the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the protein interface prediction (PIP) task and the perturbation in protein representation. The x-axis represents the magnitude of perturbation in protein representation, and the y-axis represents the AUC in percentage. The blue line shows the AUC when testing with unbound structures, which gradually decreases as the perturbation increases. The red arrow highlights the large drop in AUC when moving from test-bound to test-unbound scenarios. The yellow arrow shows how the performance with unbound structures is significantly lower than that with bound structures. This illustrates the impact of protein flexibility on the accuracy of the PIP task. The figure demonstrates a clear negative correlation between representation perturbation and the AUC, which emphasizes the importance of stable protein representations.

read the caption

Figure 3: AUC vs. representation perturbation.

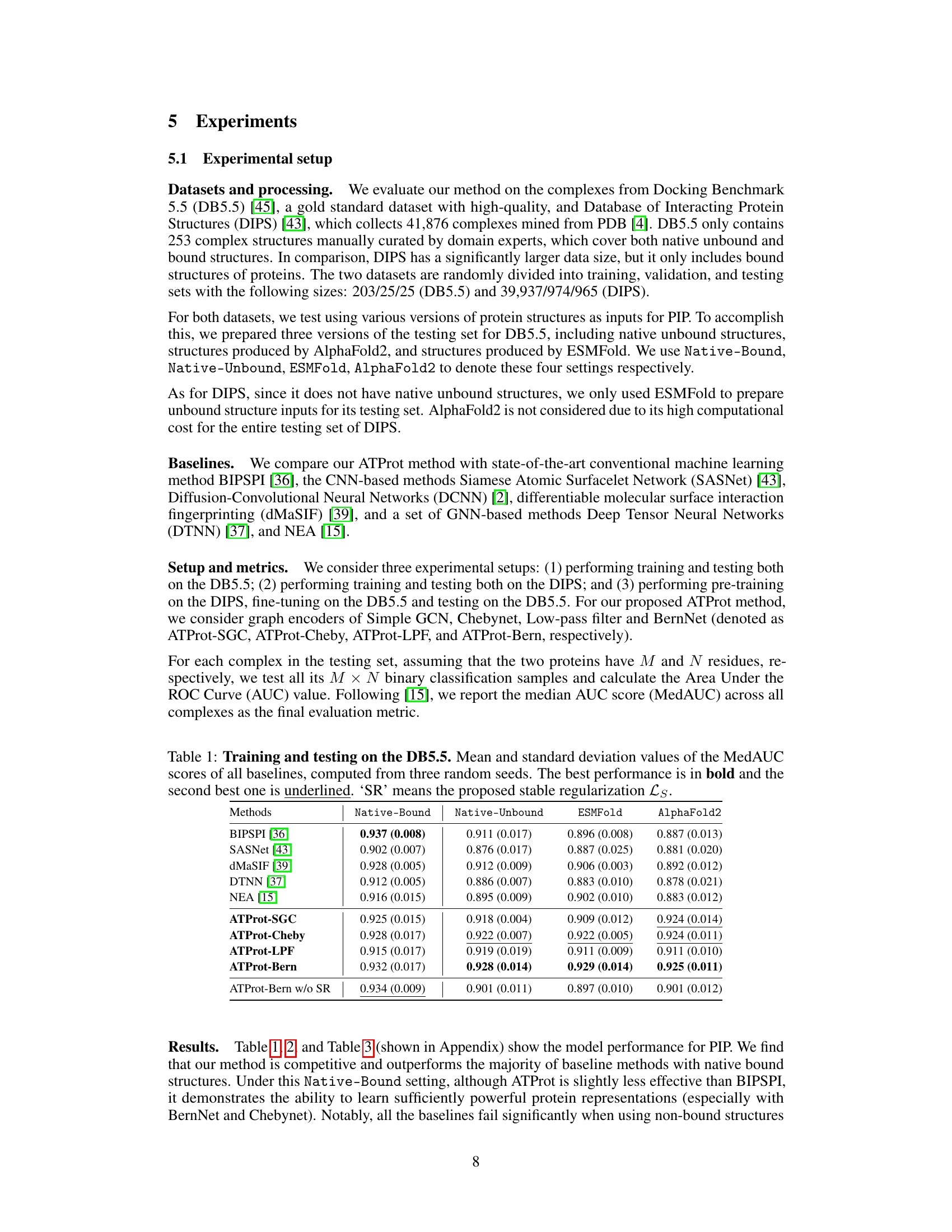

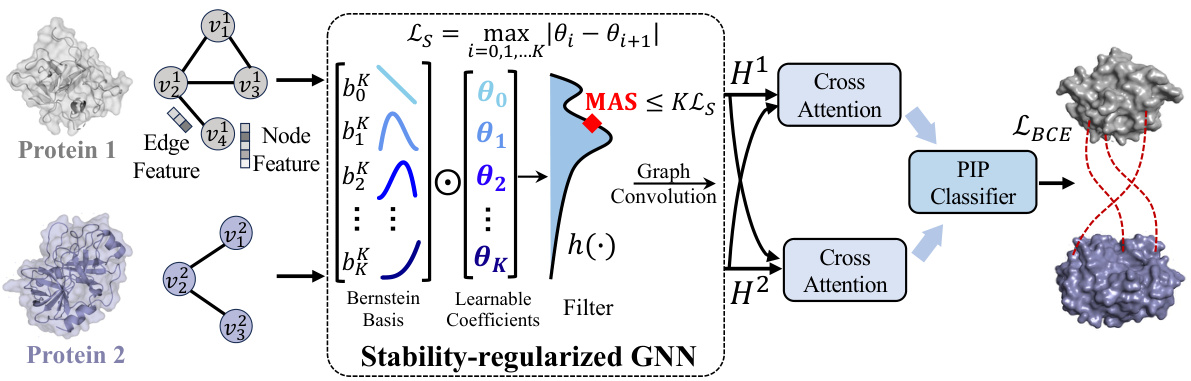

🔼 This figure shows the architecture of ATProt, a framework for protein interface prediction. It uses a stability-regularized graph neural network (GNN), specifically the BernNet encoder, to generate stable protein representations that are robust to variations in protein structure. These representations are then processed through cross-attention layers to combine information from both proteins, before being fed into a binary classifier to predict the interaction. The model is trained to minimize both classification loss (LBCE) and stability regularization loss (Ls).

read the caption

Figure 4: The framework overview with the BernNet encoder. The whole framework contains the stability-regularized graph encoder for stable protein representations, the cross attention layers for communication and the final binary classifier. ATProt takes in two protein graphs as inputs, and extracts features with the pre-defined graph encoder (BernNet is taken as an example here). The PIP results are obtained after the learned representations have passed through the cross attention module and classifier. The Ls loss for stability regularization and classification loss LBCE jointly optimize the model.

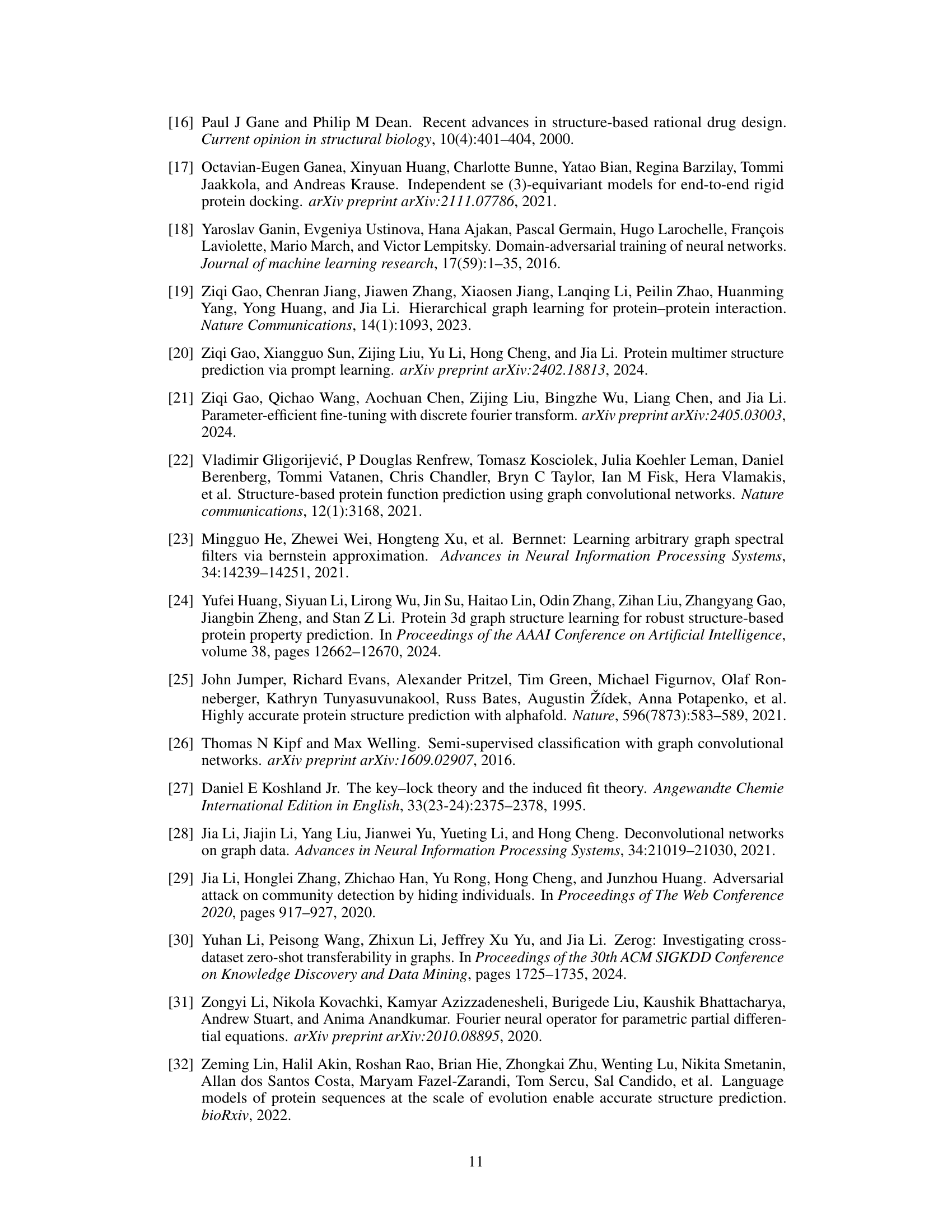

🔼 This figure visualizes the last layer representations of three different models: The NEA method, ATProt-Bern w/o SR, and ATProt-Bern, using t-SNE for dimensionality reduction. Each point represents a residue pair, colored by whether it’s a positive or negative interaction. The visualizations illustrate how the stable representation strategy in ATProt improves the clustering of positive and negative samples, leading to a clearer separation between classes (indicated by higher Silhouette score values).

read the caption

Figure 5: The t-SNE visualization for the last layer representations. The x and y axes of all three subplots are uniformly scaled to (0, 1).

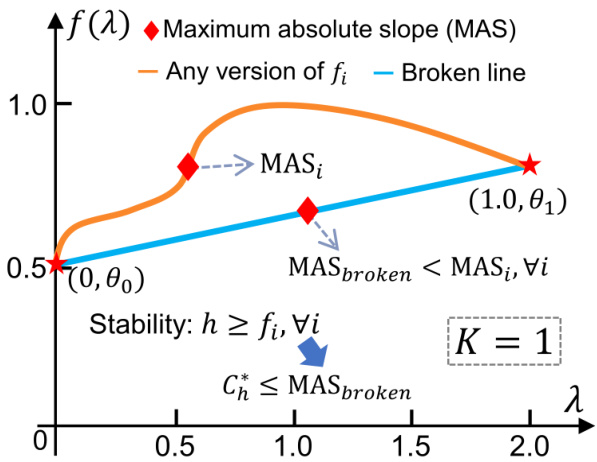

🔼 This figure illustrates how to find the upper bound of C, which is the Lipschitz constant of the BernNet encoder. It demonstrates the relationship between the function f(x) and the learnable coefficients {θk} of the Bernstein basis. The figure shows that the maximum absolute slope (MAS) of any possible version of f(x) is greater than or equal to the MAS of the piecewise linear function connecting the points (k/K, θk). The stability of h is therefore always at least that of fi. The MAS of the broken line (piecewise linear function) is then used as an upper bound for the Lipschitz constant C* of the graph filter h. This approach is crucial to prove Proposition 4.1 which guarantees the stability of the BernNet encoder.

read the caption

Figure 6: The way to find upper bound of C, a case to explain Proposition 4.1.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the results of training and testing on the DB5.5 dataset for protein interface prediction. It compares the performance of several baselines and the proposed ATProt method across different protein structure versions (native bound, native unbound, ESMFold, and AlphaFold2). The median AUC (MedAUC) score, along with standard deviation, is reported for each method and structure type. The table highlights the best-performing method for each setup and the effect of stability regularization.

read the caption

Table 1: Training and testing on the DB5.5. Mean and standard deviation values of the MedAUC scores of all baselines, computed from three random seeds. The best performance is in bold and the second best one is underlined. ‘SR’ means the proposed stable regularization Ls.

🔼 This table presents the results of training and testing various methods on the DIPS dataset. The table shows the median AUC (MedAUC) scores and standard deviations for each method, using both native-bound and ESMFold structures as input. It allows comparison of the performance of different methods in a large-scale dataset where only bound structures are available, and also demonstrates the effect of using different protein structure versions as input.

read the caption

Table 3: Training and testing on DIPS.

🔼 This table presents the results of training and testing various methods for protein interface prediction on the DB5.5 dataset. It compares the performance of the proposed ATProt method against several baseline methods. The table shows the median AUC scores (MedAUC), a measure of prediction accuracy, for each method under different testing conditions (Native-Bound, Native-Unbound, ESMFold, AlphaFold2) and indicates the best and second-best performing methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Training and testing on the DB5.5. Mean and standard deviation values of the MedAUC scores of all baselines, computed from three random seeds. The best performance is in bold and the second best one is underlined. 'SR' means the proposed stable regularization Ls.

Full paper#