TL;DR#

Federated self-supervised learning (Fed-SSL) faces challenges with inconsistent representation spaces and deviated representation abilities across heterogeneous client models, especially under skewed data distributions. Existing approaches struggle to learn effective global representations under such conditions.

FedMKD, a novel multi-teacher knowledge distillation framework, directly addresses these issues. By incorporating an adaptive knowledge integration mechanism and global knowledge anchored alignment, FedMKD effectively leverages the strengths of diverse client models to learn high-quality global representations that unify all classes from heterogeneous clients. This approach significantly improves representation quality and outperforms state-of-the-art baselines in experiments.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in federated learning due to its novel approach to tackling the challenges of heterogeneous architectures and class skew in self-supervised learning. FedMKD offers a significant improvement over existing methods, opening new avenues for research in resource-aware federated learning and global representation learning. The insights provided are highly relevant to current trends in distributed AI and will have a considerable impact on future research in this field.

Visual Insights#

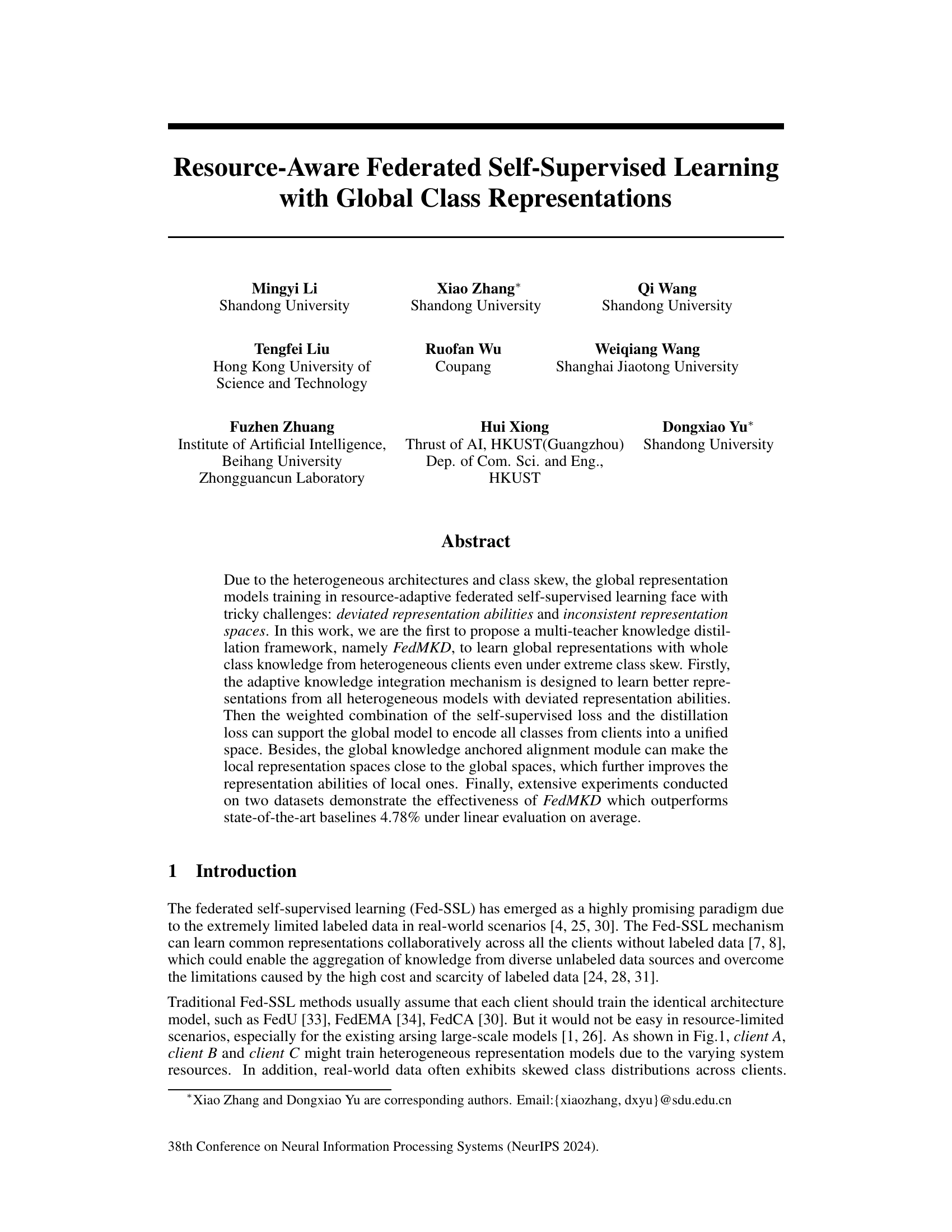

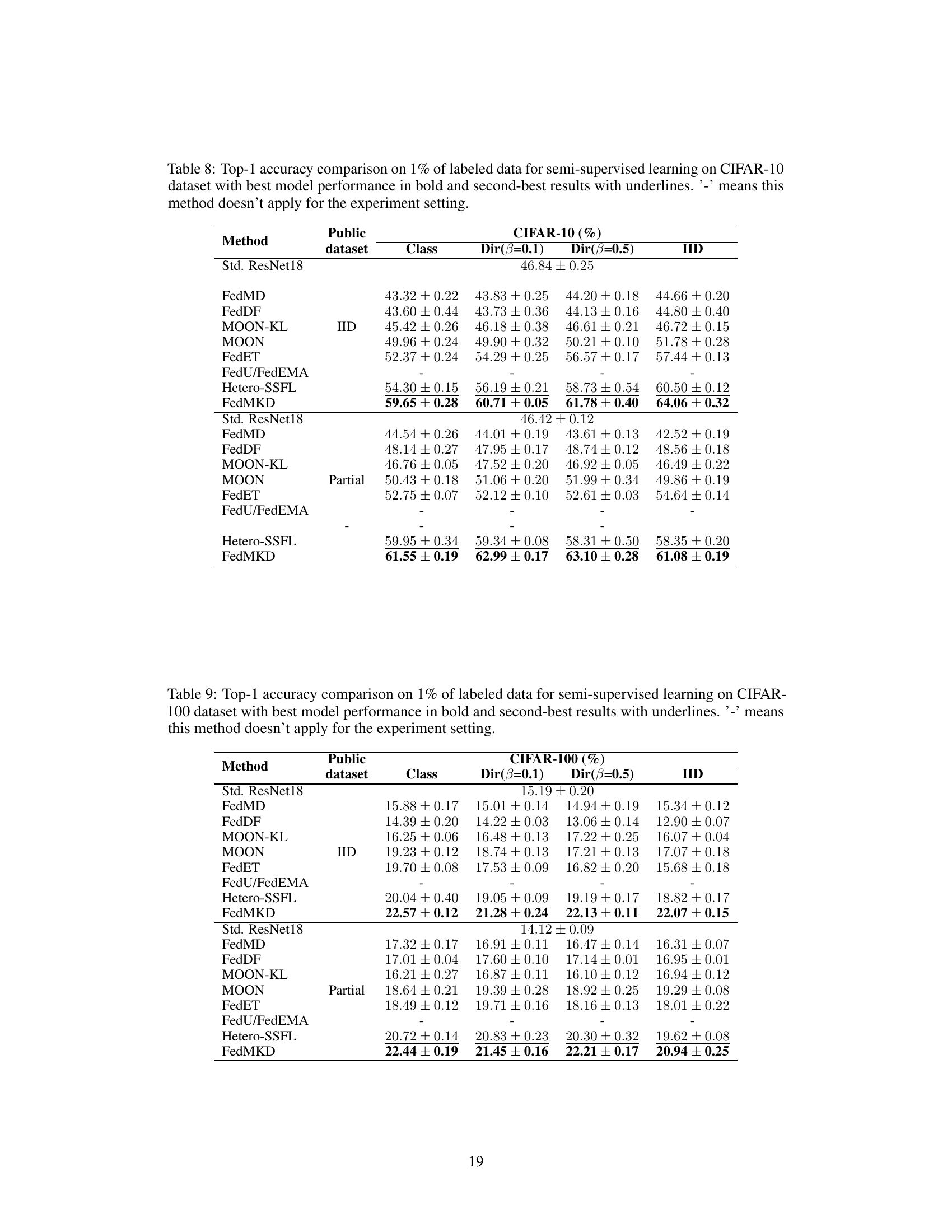

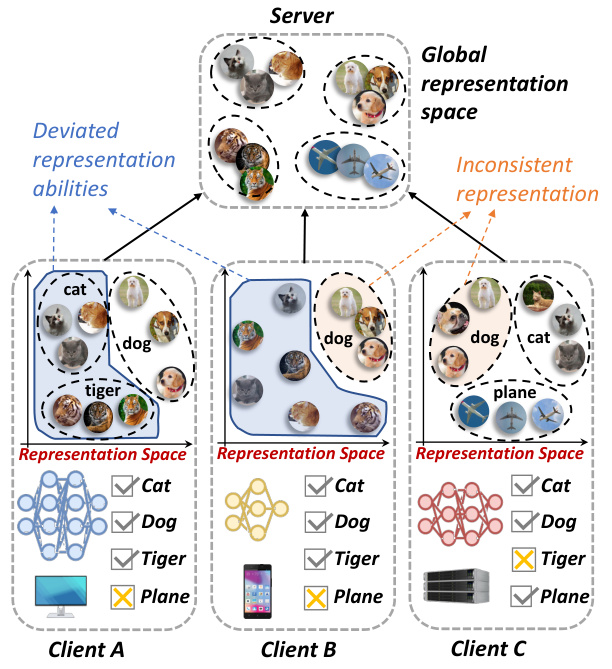

🔼 This figure illustrates the two main challenges in resource-aware federated self-supervised learning (Fed-SSL): deviated representation abilities and inconsistent representation spaces. The deviated representation abilities are shown by the different ways that different client models represent the same classes (e.g., cat, dog, tiger). The inconsistent representation spaces are shown by the fact that different clients have different classes, leading to representation spaces that do not align well.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustrations of main challenges in resource-aware Fed-SSL.

🔼 This table compares different federated self-supervised learning methods based on several key aspects: whether they use a global model, the size of the global model relative to client models, the presence of model heterogeneity across clients, the presence of deviated representation abilities among client models, the consistency of representation spaces, and whether a theoretical analysis is provided. It highlights the unique characteristics of each method and positions FedMKD within this landscape.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of federated self-supervised learning methods.

In-depth insights#

FedMKD Framework#

The FedMKD framework, proposed for resource-aware federated self-supervised learning, tackles the challenges of heterogeneous client architectures and class imbalances. Its core innovation lies in a multi-teacher knowledge distillation approach. This allows the aggregation of knowledge from diverse local models, even those with deviated representation abilities, into a unified global representation. A key component is the adaptive knowledge integration mechanism, which intelligently weighs contributions from various clients. Furthermore, the framework incorporates a global knowledge anchored alignment module to harmonize local and global representation spaces, enhancing the overall learning process. By combining self-supervised and distillation losses, FedMKD aims to efficiently generate comprehensive global class representations, which is a significant advancement in handling the complexities of federated learning with diverse, unlabeled data.

Adaptive Distillation#

Adaptive distillation, in the context of federated learning, represents a significant advancement in knowledge transfer. It tackles the challenge of heterogeneity among client models, where different architectures and data distributions prevent straightforward aggregation. Adaptive techniques dynamically adjust the weights or importance given to different clients’ contributions based on the quality or relevance of their learned representations. This crucial adaptation is vital for mitigating the impact of low-quality or biased local models on the global model. By prioritizing the knowledge from high-performing, well-trained clients, adaptive distillation ensures the global model learns robust and generalized representations. It also directly addresses the issue of inconsistent representation spaces, a key limitation in many federated learning approaches. Adaptive techniques could involve sophisticated mechanisms such as attention mechanisms or weighted averaging schemes to intelligently combine diverse local representations and thereby improve overall model performance and robustness. The dynamic nature of adaptive distillation ensures the method is flexible and resilient to changing conditions in federated learning environments.

Global Alignment#

Global alignment in federated learning aims to harmonize the diverse representations learned by individual client models. Inconsistency in local model representations, stemming from heterogeneous data distributions and architectures, hinders effective aggregation. A global alignment strategy seeks to unify these diverse feature spaces, typically by anchoring local representations to a shared global space. This process can involve techniques like knowledge distillation, where a global model learns from the collective knowledge of local models, or direct representation alignment, using metrics like Centering-and-Scaling or linear-CKA. The effectiveness of global alignment is crucial for generalization, as it ensures that aggregated models can effectively represent the entire data distribution and not just a subset learned by individual clients. Successful global alignment leads to better downstream performance on unseen data, making it a critical component in robust federated learning.

Heterogeneity Effects#

In federated learning, client heterogeneity significantly impacts model performance. Differences in data distributions, hardware capabilities, and model architectures across clients create challenges for aggregation. A thoughtful analysis of heterogeneity effects would explore how these variations affect the learning process. For example, statistical discrepancies in client data may lead to biased global models, while differences in computing resources can cause certain clients to lag behind, hindering overall training efficiency. Addressing these effects might involve techniques like data augmentation to balance data distributions, model adaptation to optimize for diverse hardware, or robust aggregation methods to mitigate the effects of outliers. A thorough investigation should quantify the impact of different sources of heterogeneity on convergence rates, model accuracy, and overall system stability, helping researchers develop strategies for designing more robust and effective federated learning systems that handle these inherent variations.

Future of Fed-SSL#

The future of federated self-supervised learning (Fed-SSL) is bright, but challenging. Addressing the heterogeneity of client devices and data distributions remains crucial. Developing more robust and efficient algorithms that can handle non-IID data and skewed class distributions is key. Adaptive knowledge integration and distillation techniques are promising avenues for improving global representation learning. Further research should focus on enhancing privacy preservation mechanisms, making Fed-SSL more robust against adversarial attacks and improving its scalability for large-scale deployments. Exploring novel self-supervised learning methods specifically designed for the federated setting and incorporating techniques like meta-learning could yield significant advancements. Addressing the resource constraints of edge devices while maintaining high performance and accuracy in Fed-SSL is also a crucial area for future development. Ultimately, the success of Fed-SSL hinges on addressing these challenges and unlocking its full potential for collaborative learning across diverse and distributed datasets.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the main challenges in resource-aware federated self-supervised learning (Fed-SSL). Specifically, it highlights the issues of deviated representation abilities and inconsistent representation spaces arising from heterogeneous client models and class skew. Client A, B, and C represent different clients with varying model architectures and data distributions. Each client’s representation space shows how their models encode similar classes (cat, dog, tiger) differently, leading to inconsistencies when attempting to combine these representations into a unified global representation space on the server.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustrations of main challenges in resource-aware Fed-SSL.

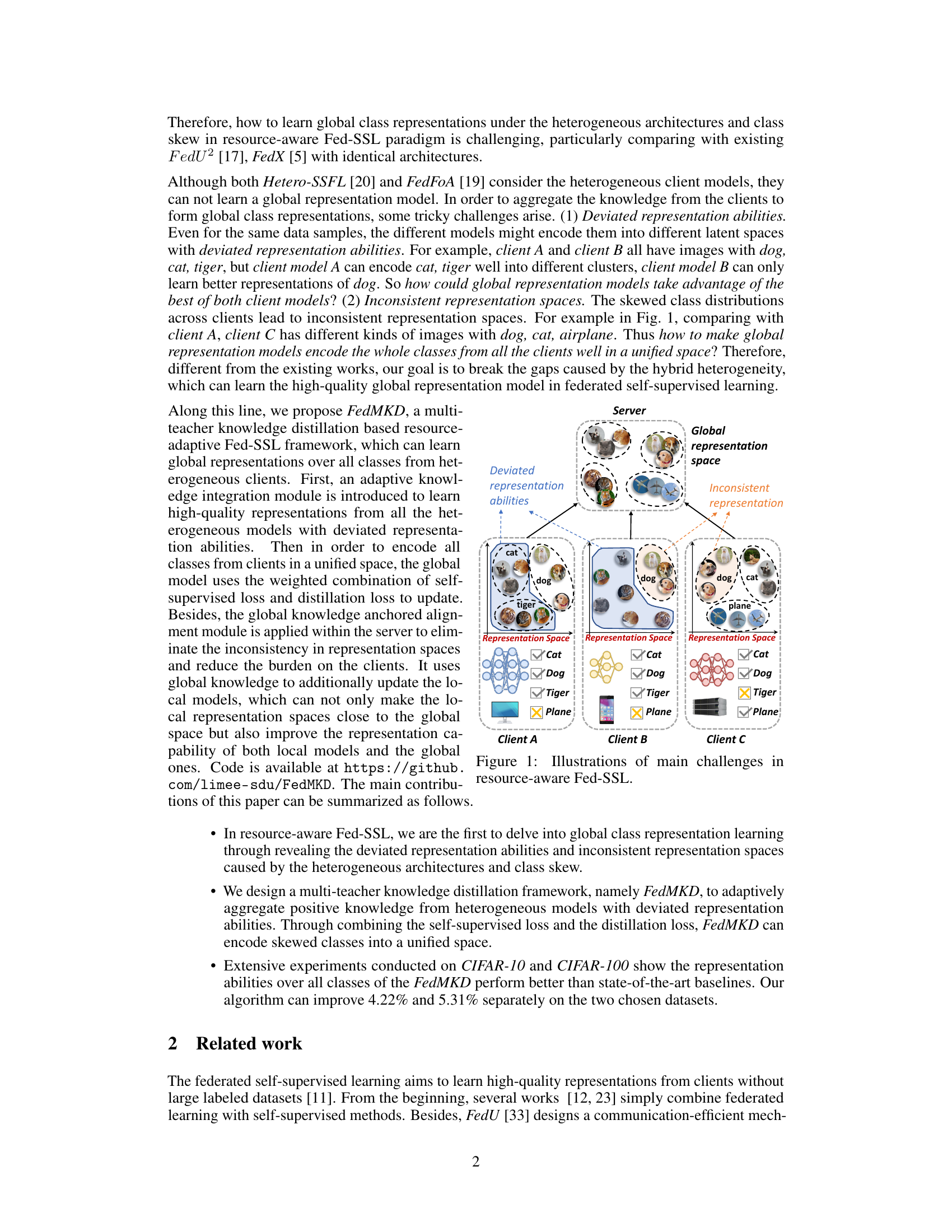

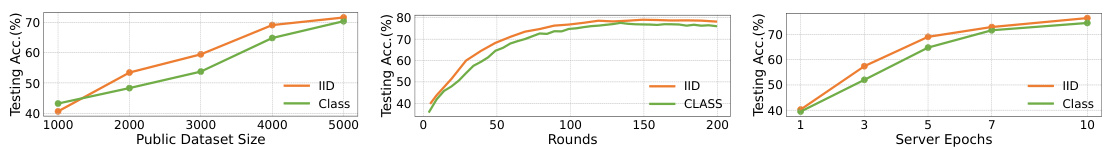

🔼 This figure illustrates the workflow of the proposed FedMKD framework. It shows how each client initializes its model based on available resources, trains it using local unlabeled data, and then the server aggregates the knowledge from different clients using a multi-teacher adaptive knowledge integration distillation method. The server then trains a global model and updates the client models using a global anchored alignment module.

read the caption

Figure 2: The overall framework of FedMKD. Clients initialize the model architecture based on the local resource, then self-supervised train the local model using unlabeled local data. The server uses the multi-teacher adaptive knowledge integration distillation to aggregate positive local knowledge to train the global model and then updates local models again according to the alignment module.

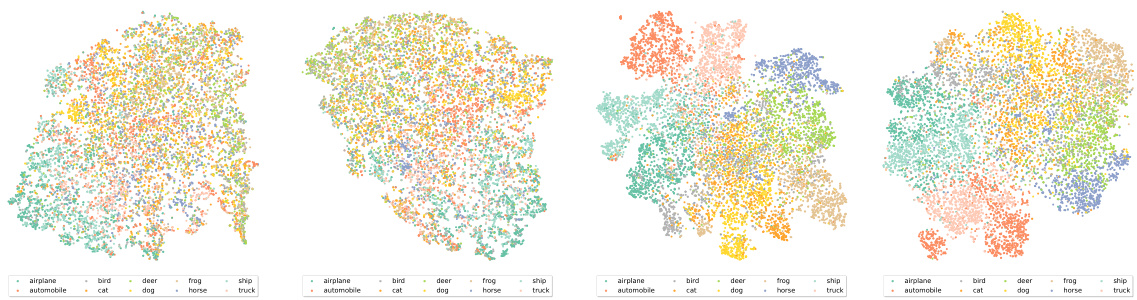

🔼 This figure displays t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) visualizations of hidden vector representations learned by different models on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The visualizations show how different models represent data points in a lower dimensional space. Panel (a) shows the results of standalone training (a single model trained on the full dataset), (b) shows results from the MOON algorithm trained on a partial public dataset, (c) shows results from the FedMKD algorithm trained on an IID (independently and identically distributed) public dataset and (d) shows the results from the FedMKD algorithm trained on a partial public dataset. The IID setting ensures each client has an equal number of samples from each class. The visualizations reveal differences in how the models cluster the data, demonstrating the impact of training methodologies on data representation.

read the caption

Figure 3: T-SNE visualizations of hidden vectors from different models on CIFAR-10, the data distribution of clients is IID.

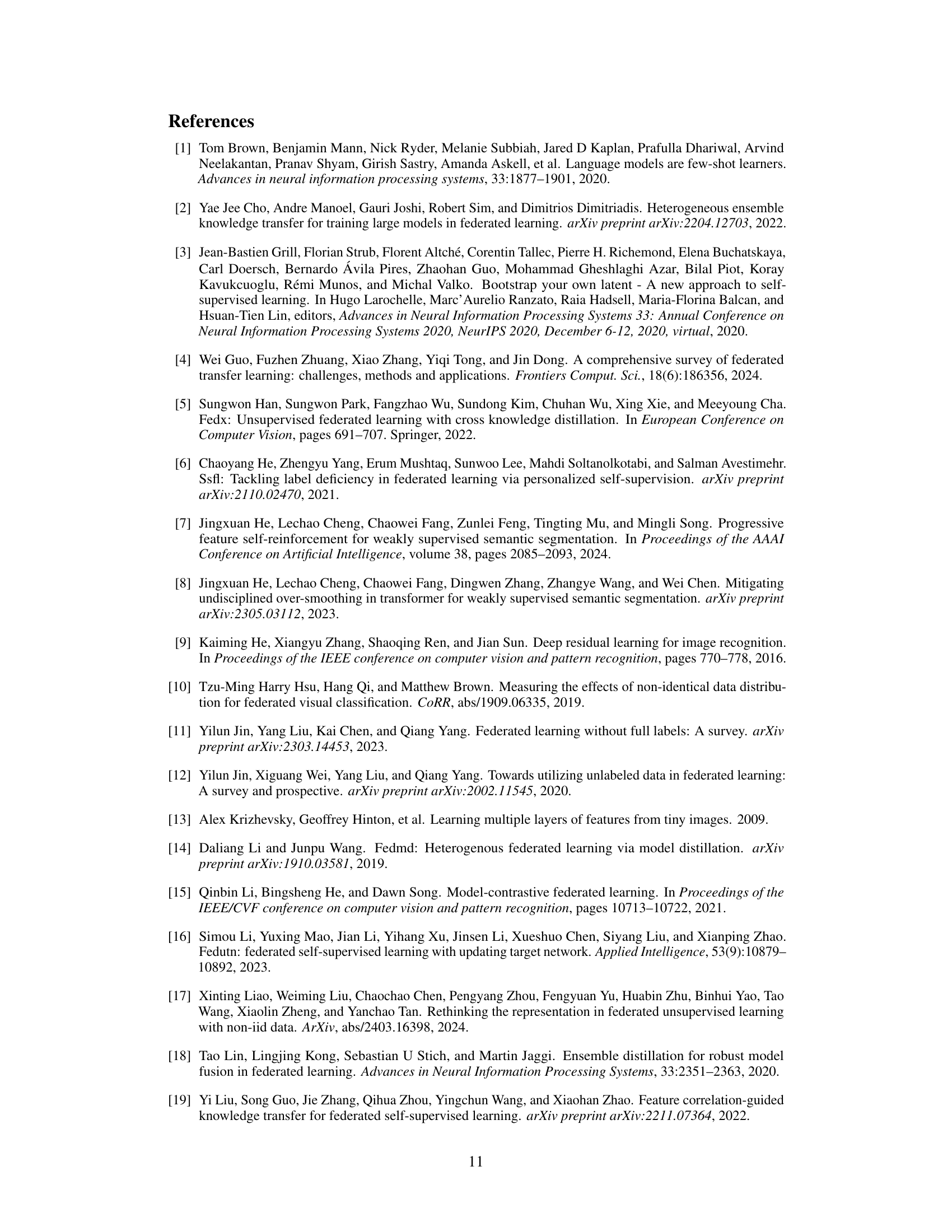

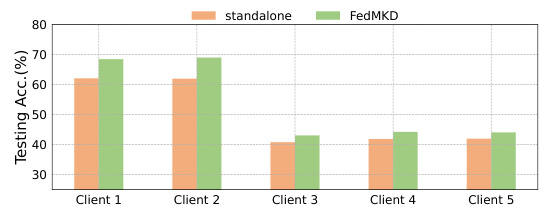

🔼 This figure shows the improvement of client model performance after participating in federated learning using the FedMKD framework. It compares the testing accuracy of standalone local model training versus the performance of the same clients when trained using FedMKD. The results demonstrate that participating in federated training with FedMKD improves the accuracy of the client models, even for those with different architectures.

read the caption

Figure 4: Improvement of clients after involving our proposed FedMKD.

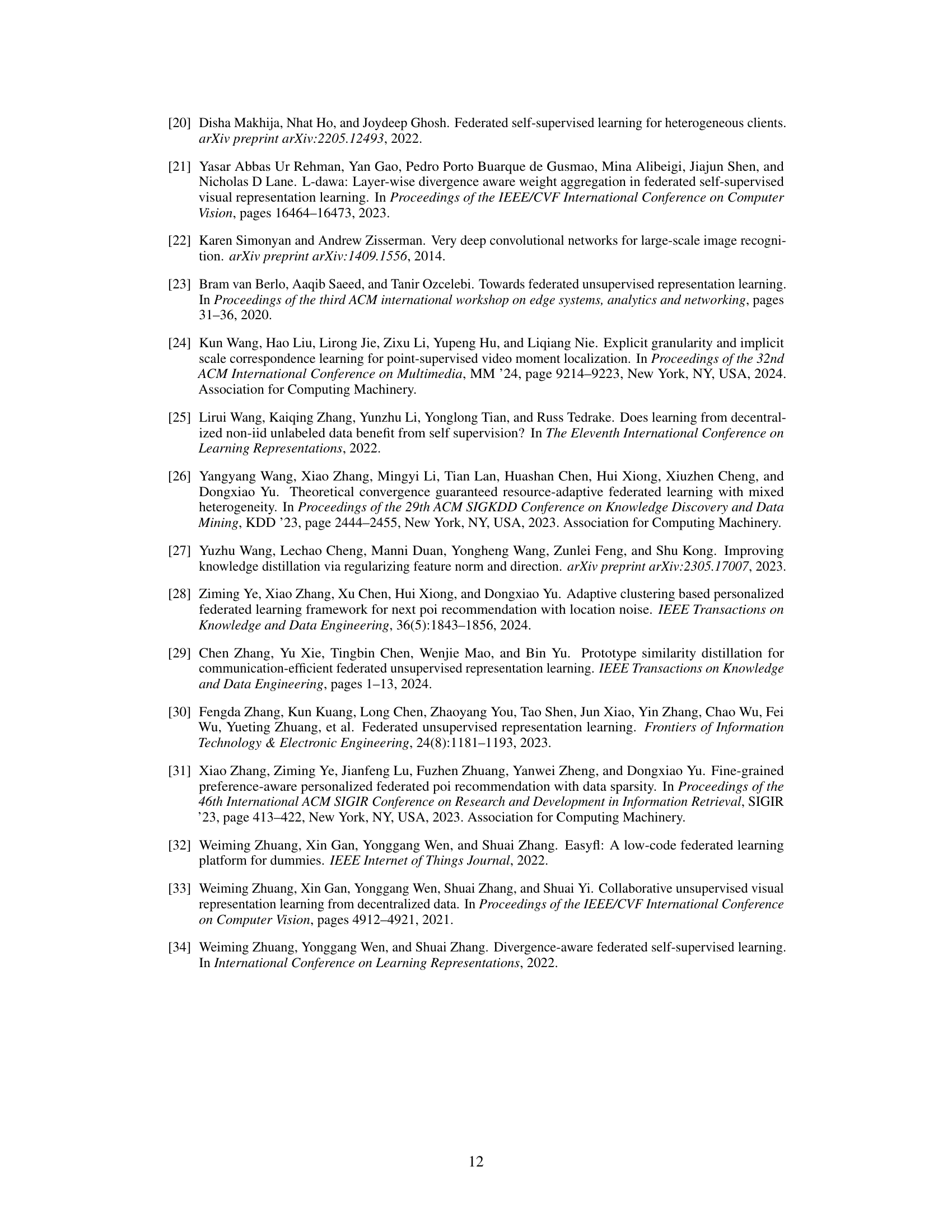

🔼 This figure shows LDA visualizations of hidden vectors from different models on CIFAR-10. The left panel illustrates the inconsistent representation spaces between different clients (Client A and Client B) before the application of the FedMKD method. Overlapping classes such as ‘cat’ and ‘dog’ highlight this inconsistency. The right panel demonstrates how FedMKD creates a unified representation space for the global model, where classes are clearly separated, resolving the inconsistency present in the client-side models.

read the caption

Figure 5: LDA visualizations of hidden vectors from different models on CIFAR-10.

🔼 This figure displays t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) visualizations, a dimensionality reduction technique, of feature vectors obtained from various models trained on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The visualizations help illustrate the learned representation spaces produced by different training methods. Panel (a) shows results from standalone training, (b) shows results from MOON (a baseline method) trained using a partial public dataset, (c) shows results from FedMKD (the proposed method) trained using an independent and identically distributed (IID) public dataset, and (d) shows results from FedMKD trained using a partial public dataset. The visualizations show how well the different methods are able to cluster similar images together, giving a visual representation of their performance in learning effective and compact image representations.

read the caption

Figure 3: T-SNE visualizations of hidden vectors from different models on CIFAR-10, the data distribution of clients is IID.

🔼 This figure shows t-SNE visualizations of hidden vectors learned by different models on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The data distribution across clients is IID (independent and identically distributed). The visualizations compare the hidden vector representations learned under different training scenarios: standalone training, MOON on a partial public dataset, FedMKD on an IID public dataset, and FedMKD on a partial public dataset. The visual separation of clusters indicates how well the different models learn to separate the different classes.

read the caption

Figure 3: T-SNE visualizations of hidden vectors from different models on CIFAR-10, the data distribution of clients is IID.

🔼 This figure shows t-SNE visualizations of hidden vectors from different models trained on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The visualizations compare the feature representations learned by different models under various training conditions (standalone training, MOON on a partial public dataset, FedMKD on an IID public dataset, and FedMKD on a partial public dataset). The goal is to illustrate the impact of the training method and data distribution on the resulting feature representations. The IID (independent and identically distributed) data distribution among clients implies that all clients have similar data distributions.

read the caption

Figure 3: T-SNE visualizations of hidden vectors from different models on CIFAR-10, the data distribution of clients is IID.

More on tables

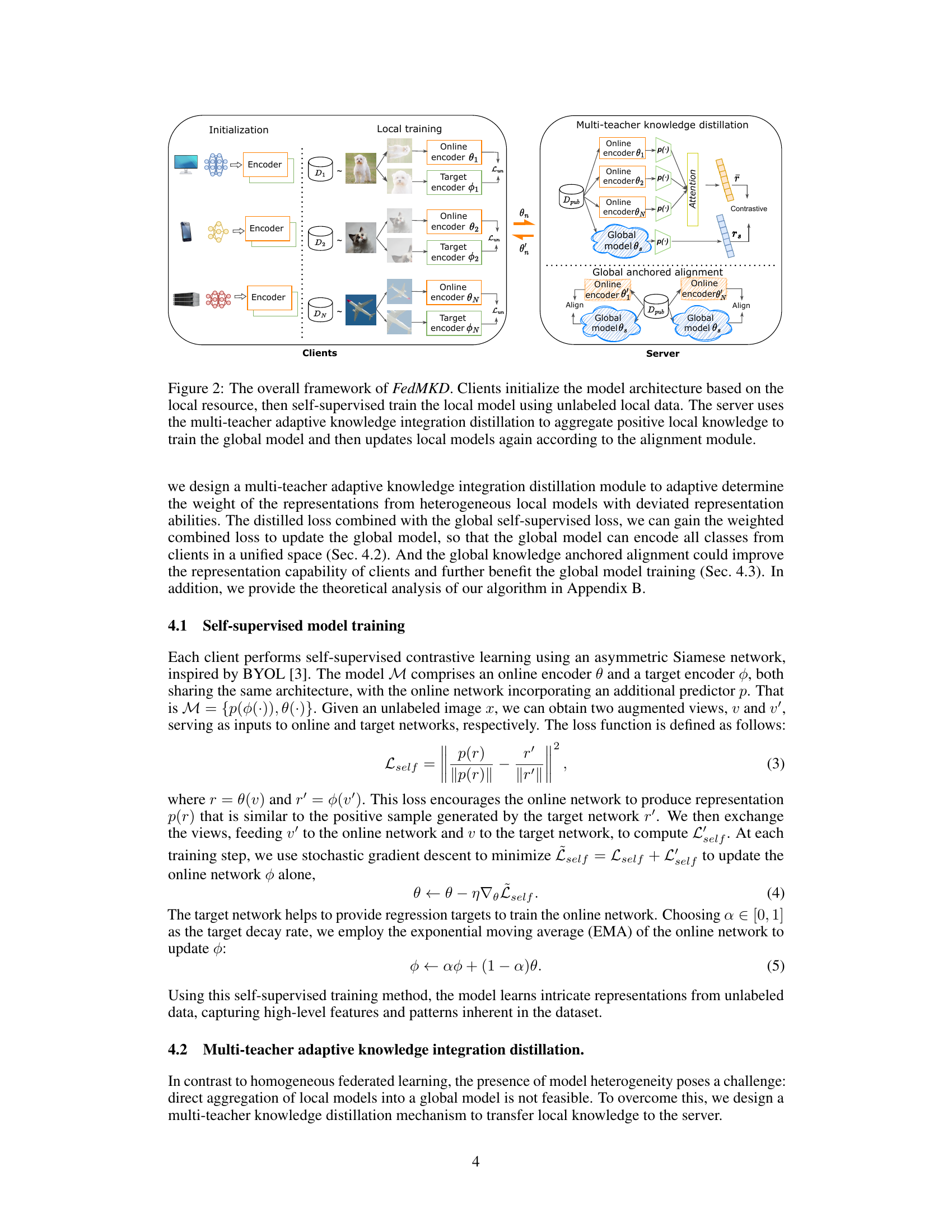

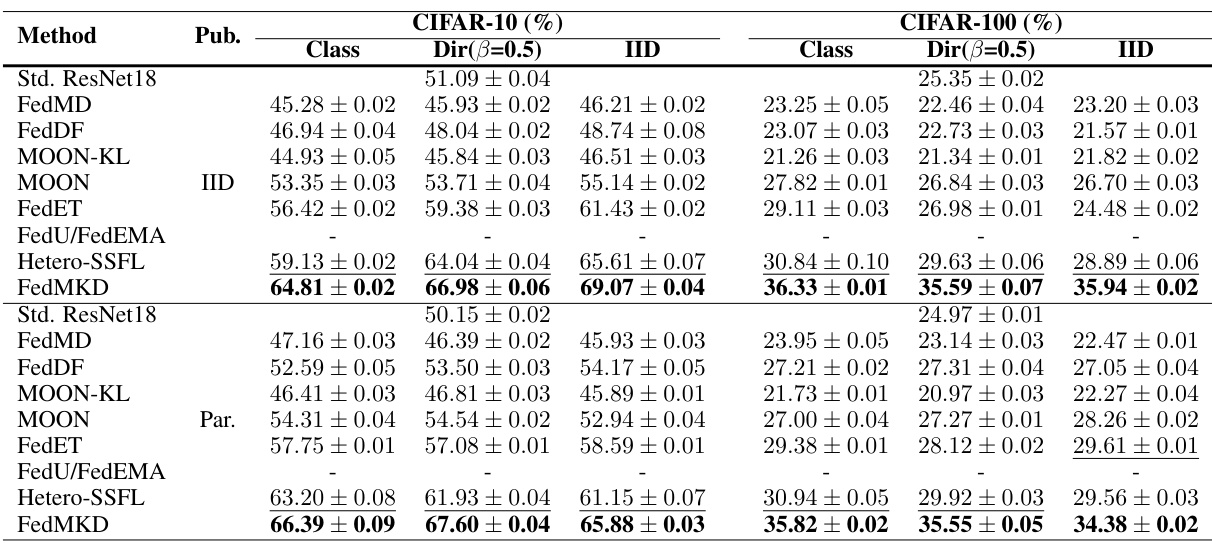

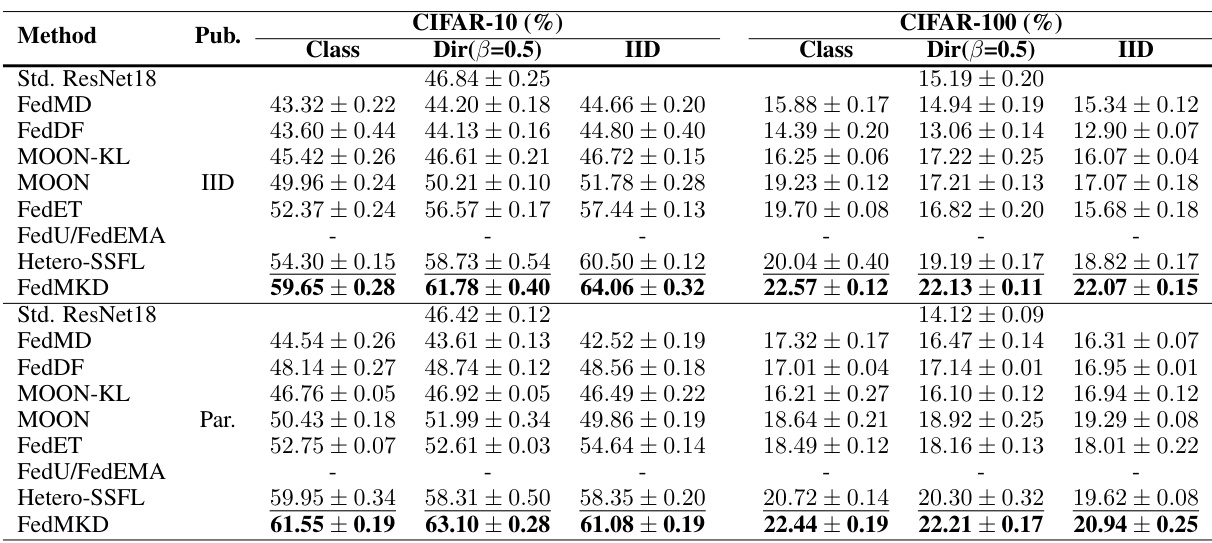

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the top-1 accuracy achieved by various federated self-supervised learning methods on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets using linear probing. The results are broken down by dataset (CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100), data distribution (IID, Class, Dir(β=0.5)), and whether a public dataset was used. The best performing model for each configuration is shown in bold, with the second-best underlined. A hyphen indicates when a method is not applicable for a given setting.

read the caption

Table 2: Top-1 accuracy comparison under linear probing on CIFAR datasets with best model performance in bold and second-best results with underlines. '-' means this method is not suitable for the experiment setting.

🔼 This table compares the Top-1 accuracy of various federated self-supervised learning methods on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets using linear probing. The results are categorized by the type of public dataset used (IID or Partial), data distribution (IID, Dir(β=0.5), Class), and the specific method used. The best and second-best performing models for each configuration are highlighted.

read the caption

Table 2: Top-1 accuracy comparison under linear probing on CIFAR datasets with best model performance in bold and second-best results with underlines. '-' means this method is not suitable for the experiment setting.

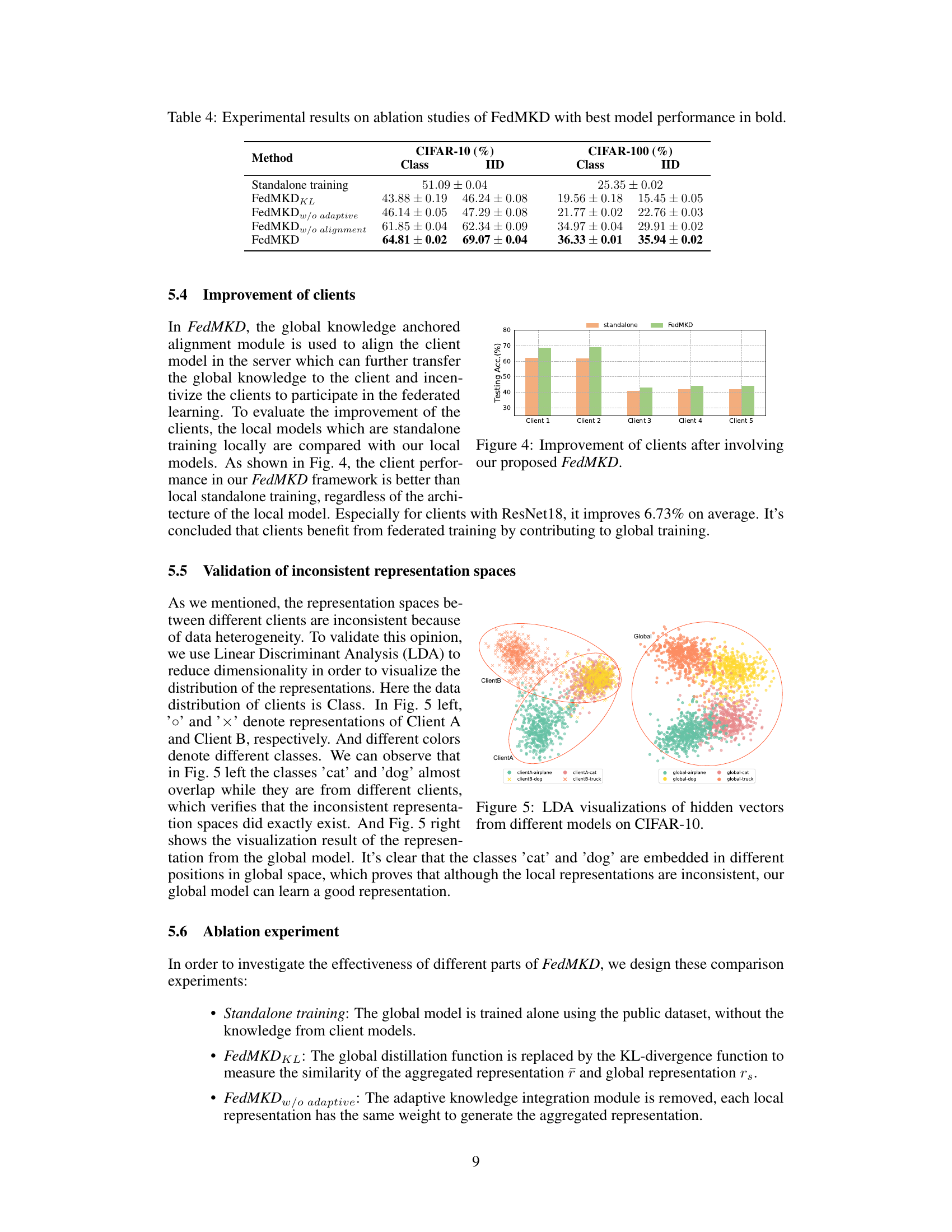

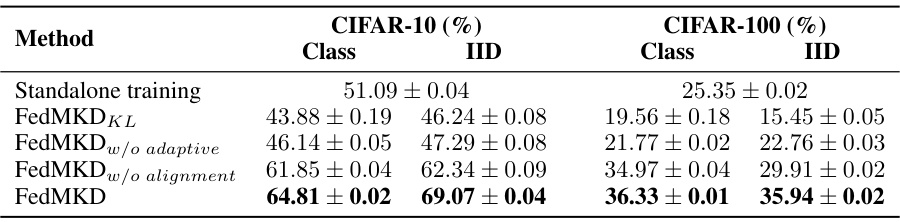

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted on the FedMKD model. It shows the impact of removing key components of the FedMKD framework, such as the KL-divergence loss, adaptive knowledge integration, and global knowledge anchored alignment. By comparing the performance of the full FedMKD model against these variants, the table demonstrates the contribution of each component to the overall performance. The results are presented separately for CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets, with both class and IID data distributions.

read the caption

Table 4: Experimental results on ablation studies of FedMKD with best model performance in bold.

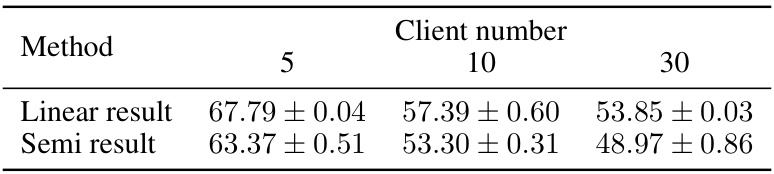

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments conducted to evaluate the scalability of the FedMKD algorithm. The performance (linear and semi-supervised results) of FedMKD is measured across varying numbers of clients (5, 10, and 30). The results show the impact of increasing the number of clients on the algorithm’s performance.

read the caption

Table 5: Experimental results on scalability studies of FedMKD.

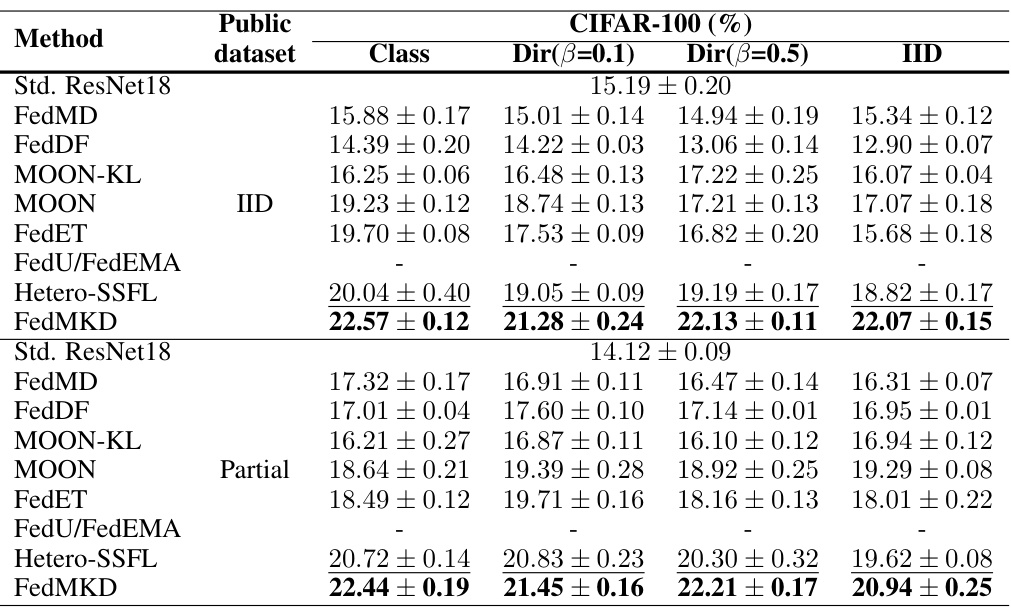

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the top-1 accuracy achieved by different federated self-supervised learning methods on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets using linear probing. The results are categorized by the type of public dataset used (IID or Partial), data distribution (IID, Dir(β=0.1), Dir(β=0.5), and Class), and the specific method. The best and second-best performances for each setting are highlighted. A dash indicates that the particular method is not applicable to a given experimental condition.

read the caption

Table 2: Top-1 accuracy comparison under linear probing on CIFAR datasets with best model performance in bold and second-best results with underlines. '-' means this method is not suitable for the experiment setting.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the top-1 accuracy achieved by different federated self-supervised learning methods on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. The accuracy is measured using linear probing, and the best and second-best results for each setting (IID, Class, Dir(β=0.5)) and dataset are highlighted. The table also indicates which methods are not applicable for specific settings.

read the caption

Table 2: Top-1 accuracy comparison under linear probing on CIFAR datasets with best model performance in bold and second-best results with underlines. '-' means this method is not suitable for the experiment setting.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different federated self-supervised learning methods on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. The methods are evaluated under three different data distributions (IID, Class, and Dirichlet with β=0.5). The table shows the top-1 accuracy achieved by each method using linear probing. The best and second-best results are highlighted for each setting.

read the caption

Table 2: Top-1 accuracy comparison under linear probing on CIFAR datasets with best model performance in bold and second-best results with underlines. '-' means this method is not suitable for the experiment setting.

🔼 This table compares the Top-1 accuracy of various federated self-supervised learning methods on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets using linear probing. The results are shown for different public dataset types (‘IID’ and ‘Partial’), class distributions (IID, Dir(β=0.1), Dir(β=0.5)), and model settings. The best and second-best performing methods for each scenario are highlighted. A ‘-’ indicates the method wasn’t applicable for a given setup.

read the caption

Table 2: Top-1 accuracy comparison under linear probing on CIFAR datasets with best model performance in bold and second-best results with underlines. '-' means this method is not suitable for the experiment setting.

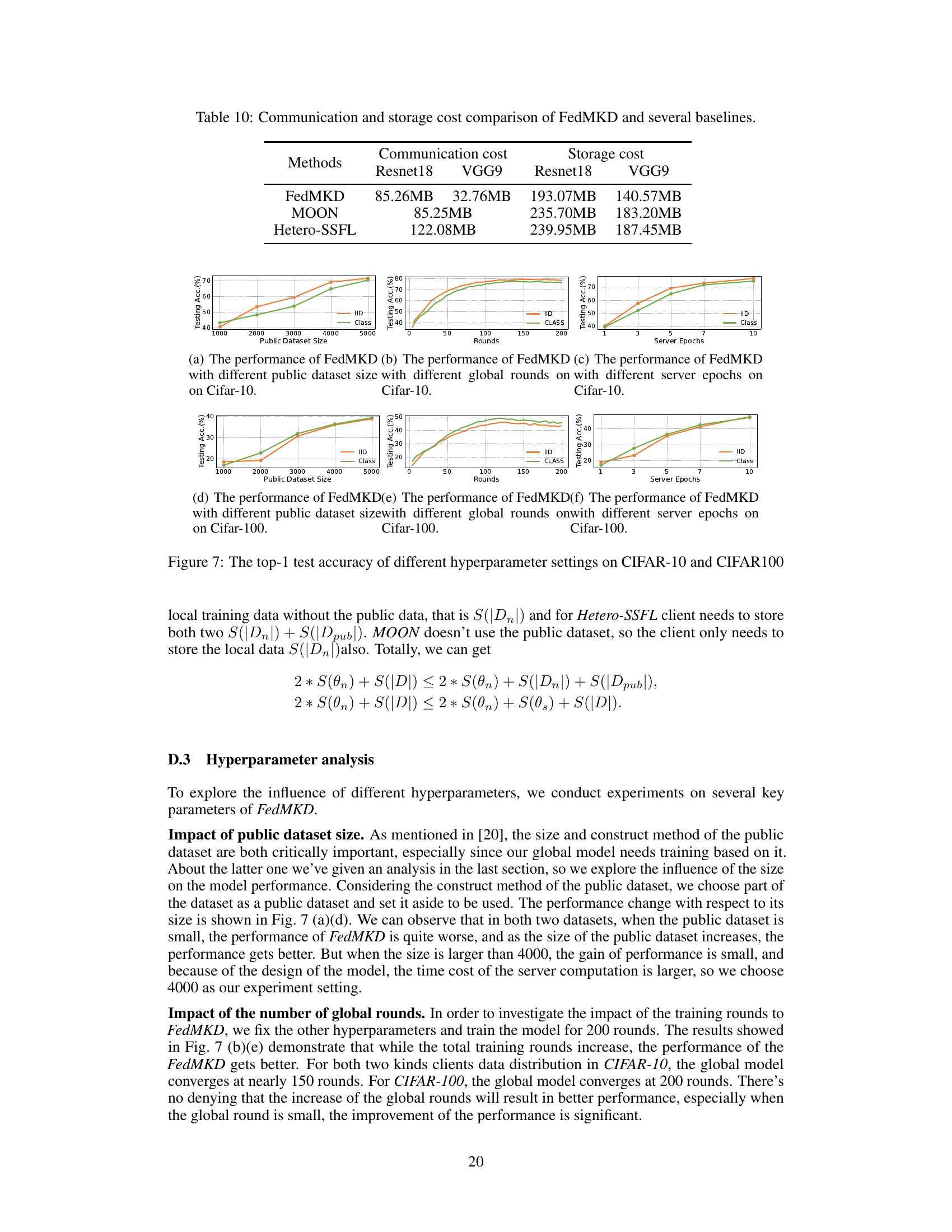

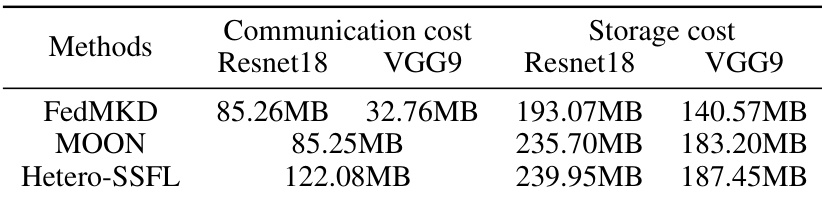

🔼 This table compares the communication and storage costs of the proposed FedMKD method with several baseline federated self-supervised learning methods. The communication cost represents the amount of data transferred during model training, while the storage cost indicates the amount of memory required to store model parameters. The table breaks down these costs separately for models using ResNet18 and VGG9 architectures. This helps understand the efficiency of FedMKD concerning resource utilization during the federated learning process.

read the caption

Table 10: Communication and storage cost comparison of FedMKD and several baselines.

Full paper#