↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many machine learning tasks rely on comparison data from individuals, but this data is often subjective and unverifiable. Existing peer prediction mechanisms for truthful data elicitation assume independent tasks, which isn’t applicable to comparison data where responses are intrinsically correlated (e.g., if A is preferred to B and B to C, A is likely preferred to C). This makes truthful elicitation challenging. The paper tackles this problem by designing new mechanisms that effectively incentivize truthful responses even in complex scenarios.

The core contribution is a novel peer prediction mechanism that uses a bonus-penalty payment scheme to incentivize truthful comparisons. This mechanism cleverly leverages the strong stochastic transitivity property inherent in comparison data. Furthermore, the paper extends this mechanism to handle data collected from social networks, where responses are correlated due to homophily, demonstrating that the mechanism still functions well under these conditions. The paper’s theoretical contributions are supported by experiments on real-world data, showcasing its practical applicability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on incentivizing truthful data contributions, especially in scenarios lacking ground truth verification. It introduces novel mechanisms for eliciting comparison data and networked data, addressing a critical challenge in many machine learning applications. The findings are valuable for advancing peer prediction mechanisms and information elicitation techniques, opening up new avenues for designing more effective and reliable data collection strategies.

Visual Insights#

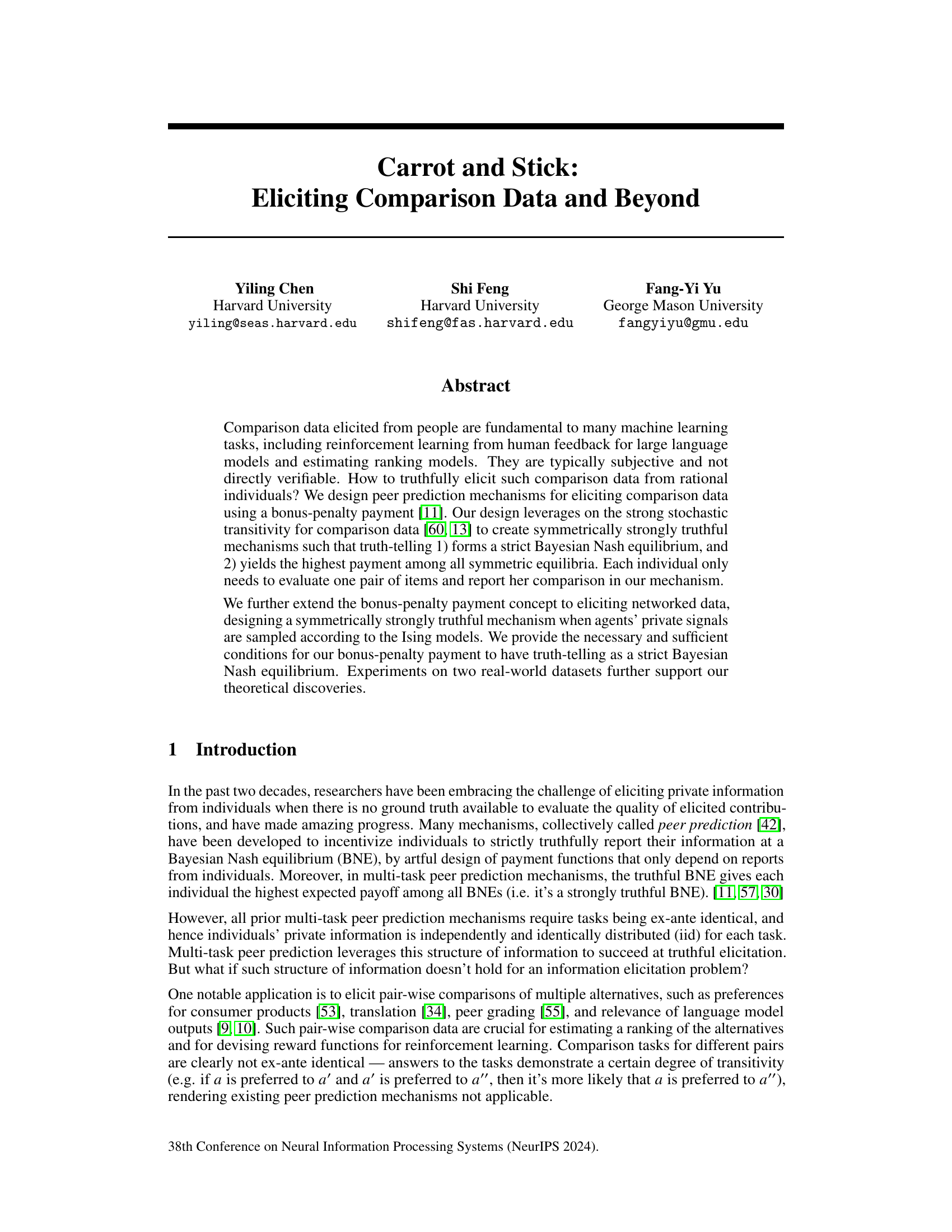

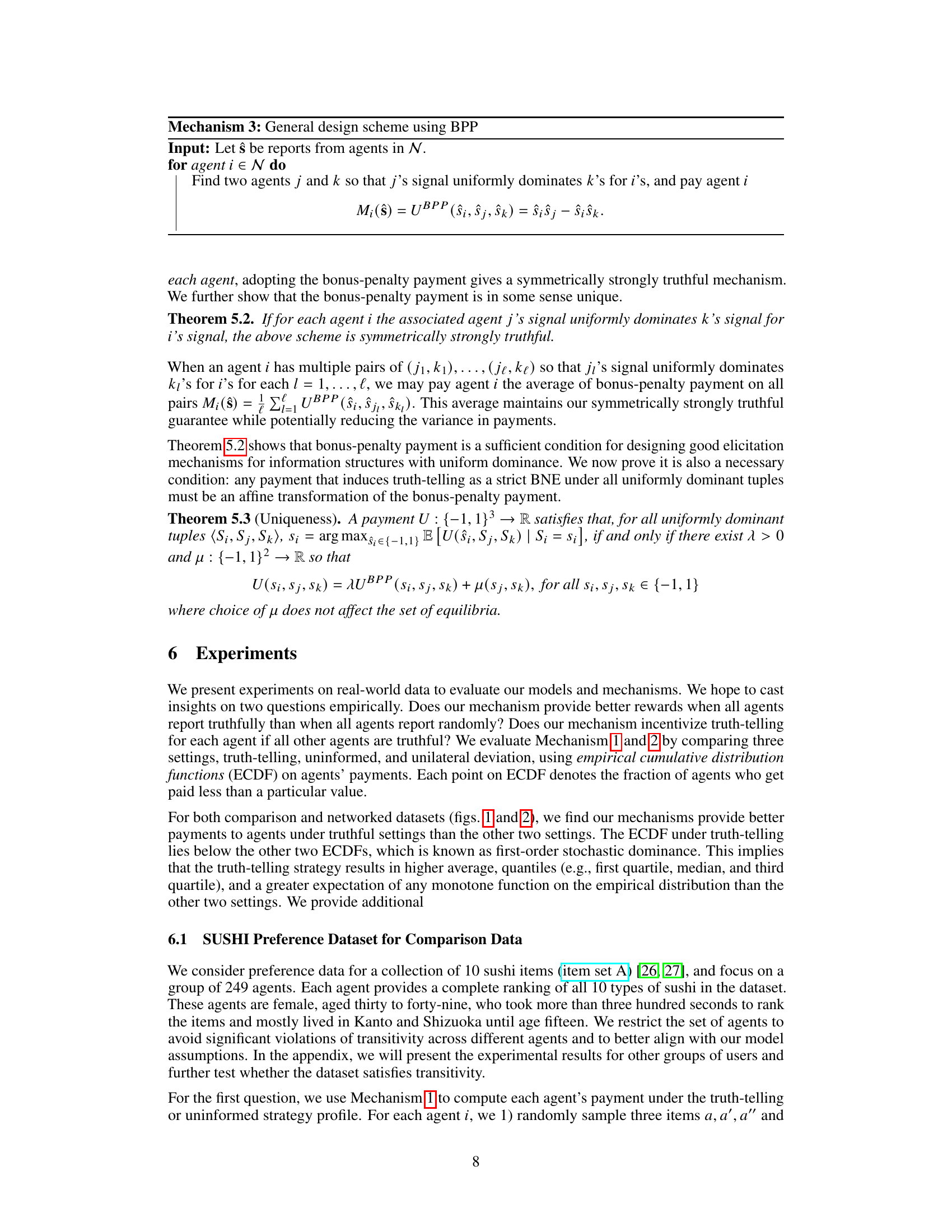

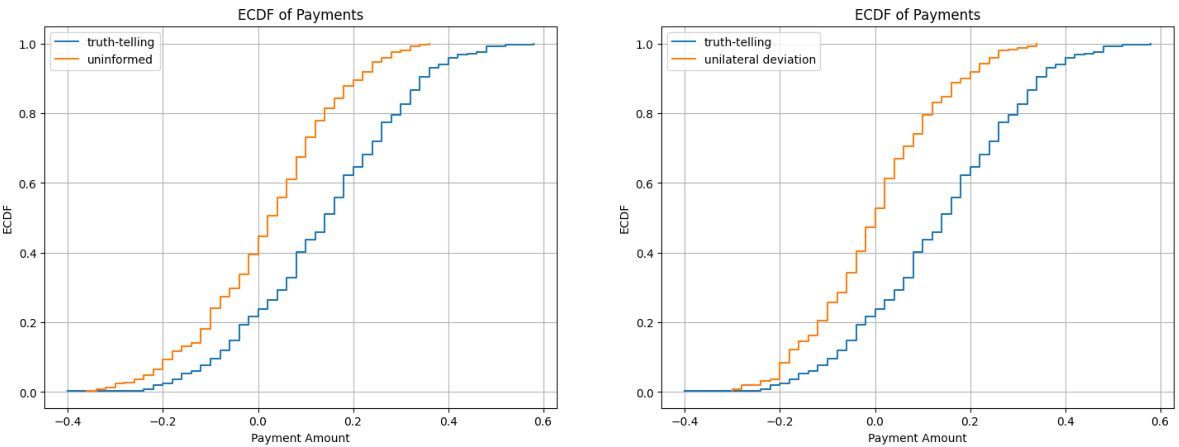

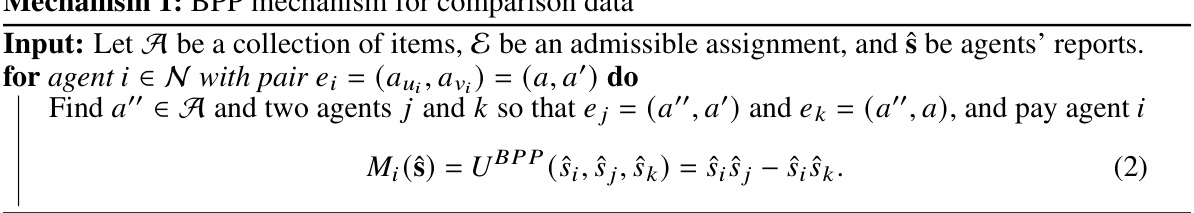

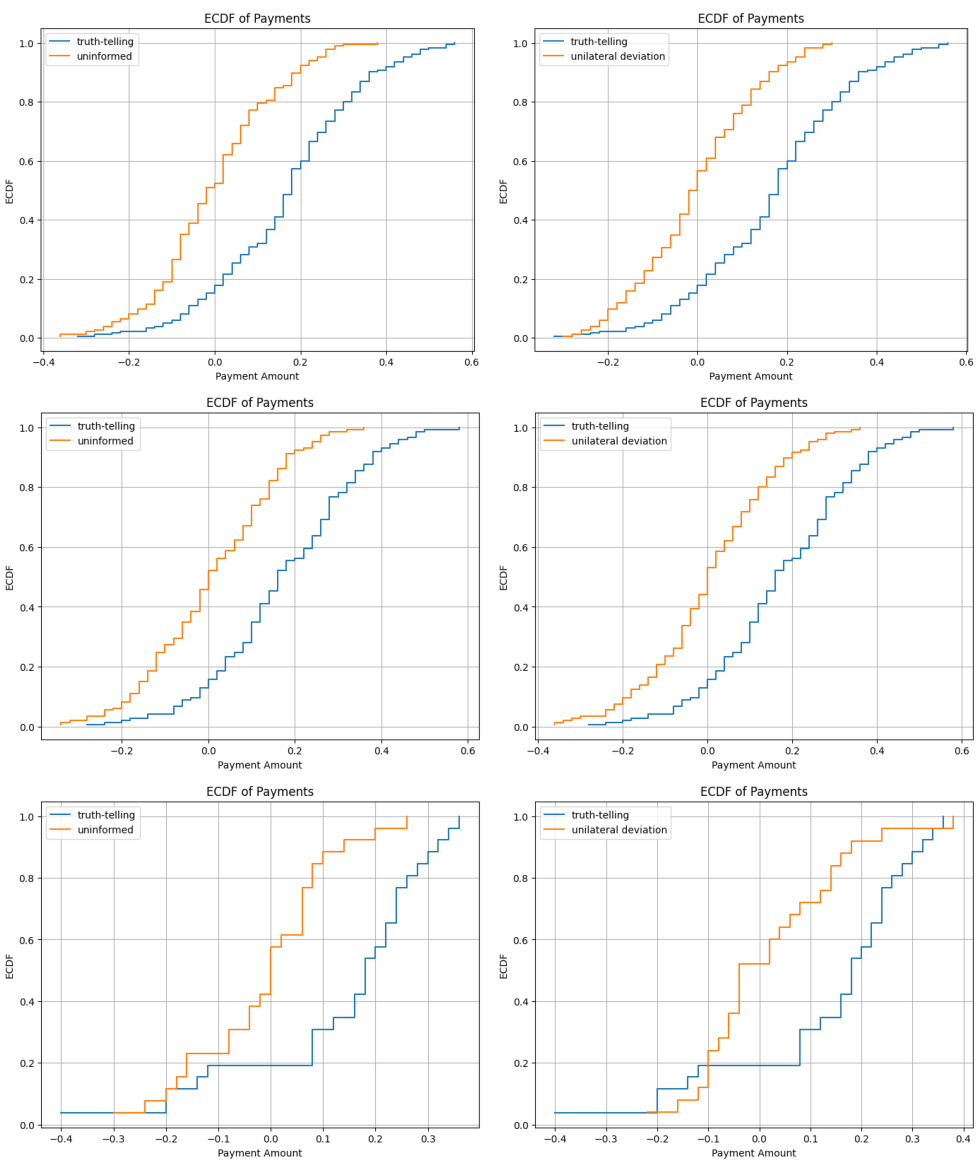

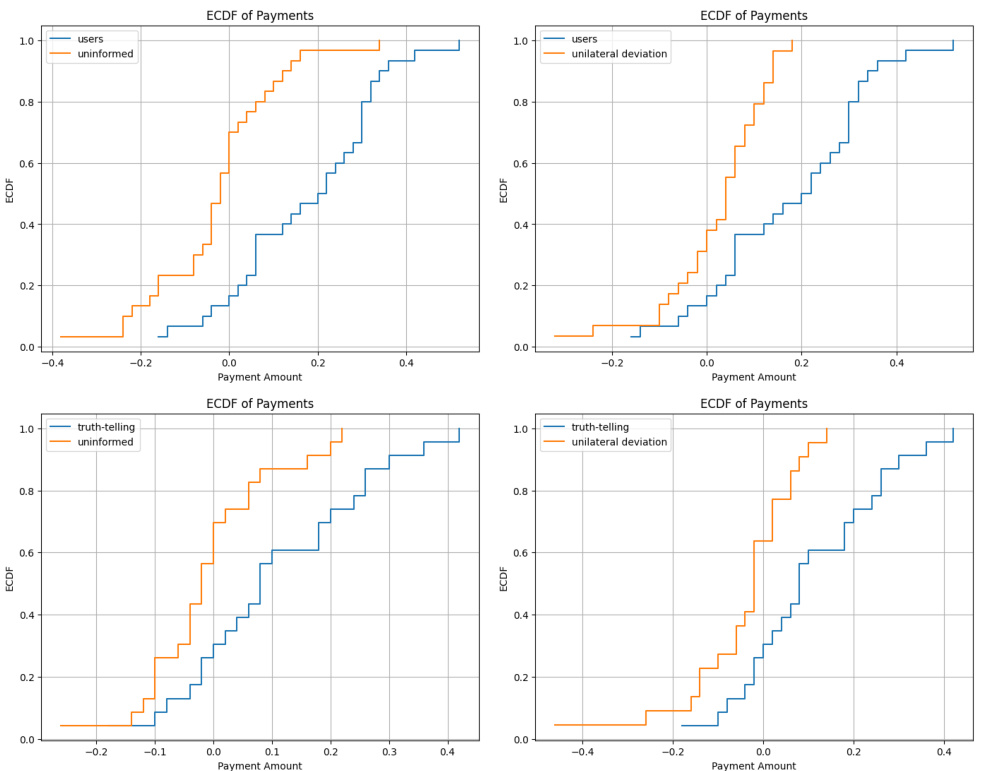

This figure shows the empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF) of payments for agents under three different settings: truth-telling, uninformed, and unilateral deviation. The left column demonstrates the ECDF of payments when all agents either report truthfully or randomly. The right column compares the ECDF of payments under truth-telling against the scenario where a single agent deviates while others report truthfully. The results suggest that the truthful strategy leads to higher payments compared to other strategies.

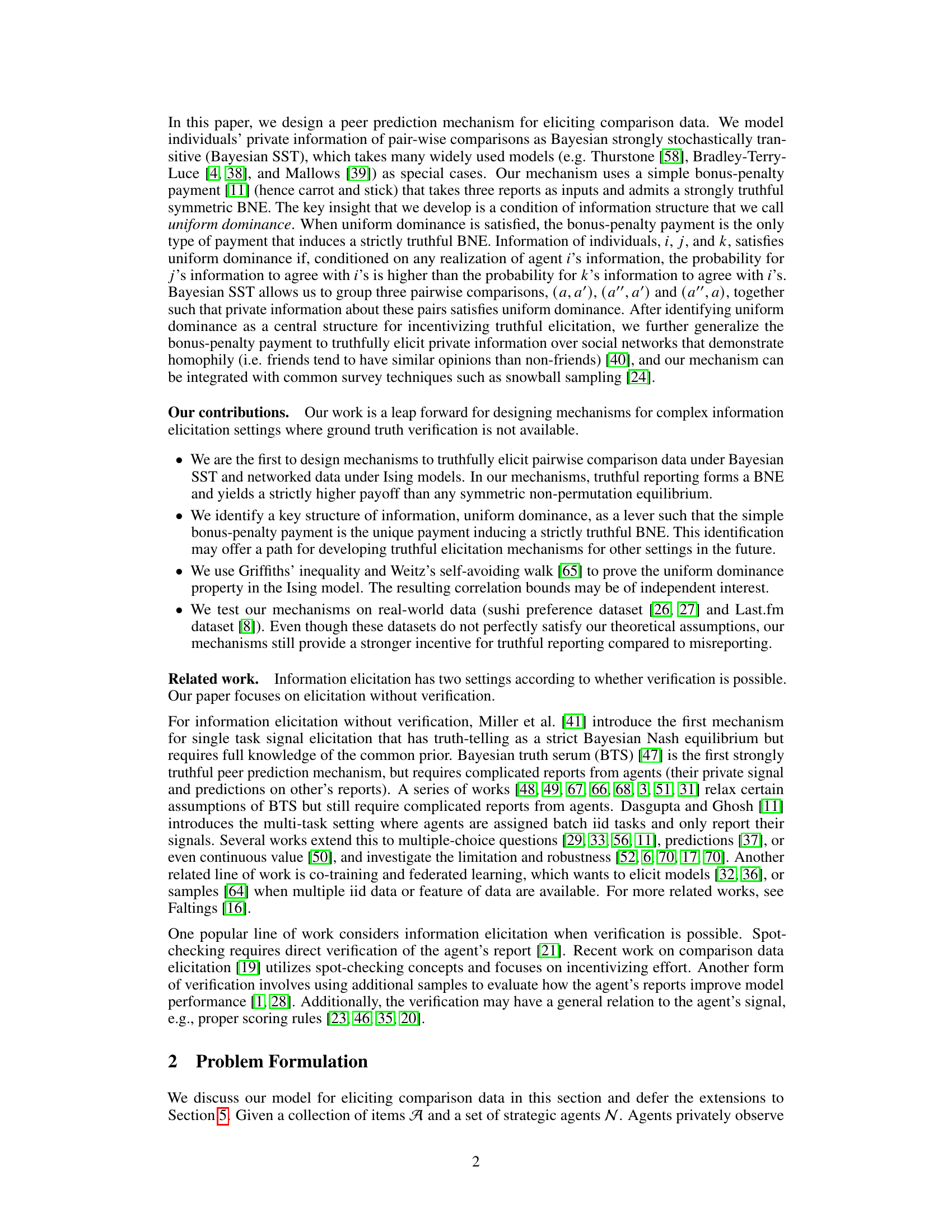

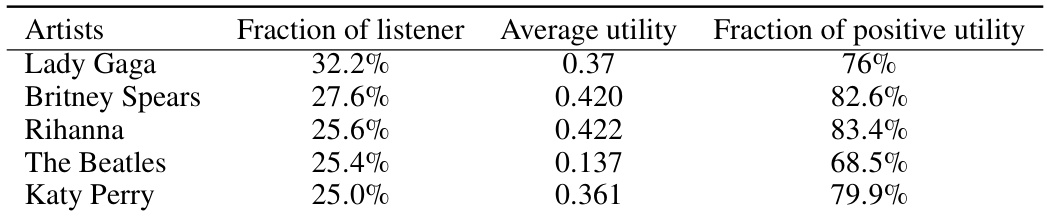

This table presents a summary of the results obtained from an experiment to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed mechanism for eliciting truthful responses in comparison data. Specifically, it shows the average utility and the fraction of positive utility for several different user groups, defined by gender, age, and location. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the mechanism even when the dataset has some limitations.

In-depth insights#

Incentivizing Comparisons#

Incentivizing truthful comparisons is crucial for various machine learning applications, especially when ground truth is unavailable. Peer prediction mechanisms offer a solution by strategically designing payment schemes that reward truthful comparisons. Strong stochastic transitivity in preference data, and uniform dominance conditions, create a framework for ensuring the truthful Bayesian Nash equilibrium. The bonus-penalty payment mechanism, inspired by carrot-and-stick incentives, is a key design element. Careful consideration of information structure and careful agent assignment are essential for mechanism effectiveness. Real-world applications, such as preference elicitation and networked data analysis, highlight the practical significance of incentivized comparisons, particularly under conditions of homophily. Further research could explore the robustness of such mechanisms under various noise models and different agent behavior assumptions. Developing methods to elicit rich comparative data remains an important challenge for advancing machine learning systems.

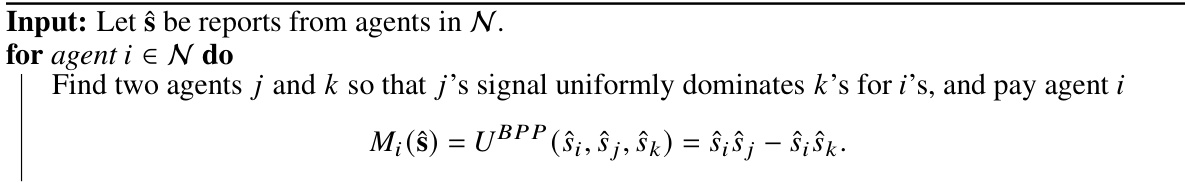

Bonus-Penalty Mechanism#

The bonus-penalty mechanism is a peer prediction method designed to incentivize truthful responses in settings where ground truth is unavailable. It leverages a payment scheme that rewards agreement between a participant’s report and a carefully selected peer’s report, while penalizing agreement with another peer whose report is less likely to be truthful. This mechanism cleverly utilizes the inherent stochastic transitivity often found in comparative data (e.g., preference rankings). The key to its success is creating a structure of uniform dominance: ensuring that for any given participant, a chosen peer’s report is more likely to be correct than another. This ensures the incentive to provide truthful information, leading to a Bayesian Nash equilibrium. While simple in design, the bonus-penalty mechanism offers a robust solution, addressing limitations of prior methods that assumed identical tasks. Importantly, its strong truthfulness and flexibility extend its application beyond simple comparison data, making it suitable for complex settings such as networked data and social networks.

Networked Data#

The concept of ‘Networked Data’ in this context refers to data exhibiting dependencies or correlations within a network structure. This is significant because it moves beyond the assumption of independent and identically distributed (iid) data commonly found in simpler peer prediction mechanisms. The authors extend the bonus-penalty payment framework to handle this complex scenario. They specifically focus on scenarios where relationships between agents’ private signals follow Ising model patterns, capturing homophily (similarity between connected agents). This extension demonstrates the robustness of their framework, showcasing the applicability of bonus-penalty payments in settings beyond iid data. A key achievement is proving the strong truthfulness of the mechanism even with networked data under specified conditions. The success in extending to networked data highlights the broad potential of the uniform dominance concept, which forms the theoretical foundation for incentivizing truthful responses.

Real-world Experiments#

A dedicated ‘Real-world Experiments’ section would significantly strengthen a research paper. It should detail the datasets used, justifying their selection based on relevance to the problem and the algorithm’s assumptions. Concrete examples of data preprocessing steps are crucial for reproducibility. The experimental design should be clearly outlined, specifying evaluation metrics and the rationale behind them. Results should be presented visually, using graphs and tables, and statistical significance testing should be used to support claims. A discussion comparing results across various datasets (if applicable) is valuable. Limitations of the real-world data and their potential impact on the findings should be transparently addressed. Finally, the section should conclude with a summary of the key findings and their implications, relating them back to the paper’s main contributions.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several key areas. Extending the bonus-penalty mechanism to handle more complex data structures like time series or hierarchical data, where relationships between data points are not uniformly distributed, is crucial. Investigating the robustness of the mechanisms to different levels of agent rationality or strategic behavior is also warranted, potentially incorporating concepts from behavioral economics. The unique payment function identified warrants further exploration, specifically in characterizing the boundary conditions under which it remains optimal. Generalizing the uniform dominance concept to broader classes of information elicitation problems is another fertile avenue for future research. Finally, empirical investigations using diverse, large-scale datasets, covering various domains and demographics, are needed to fully validate the practical applicability and effectiveness of these elicitation mechanisms in real-world settings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

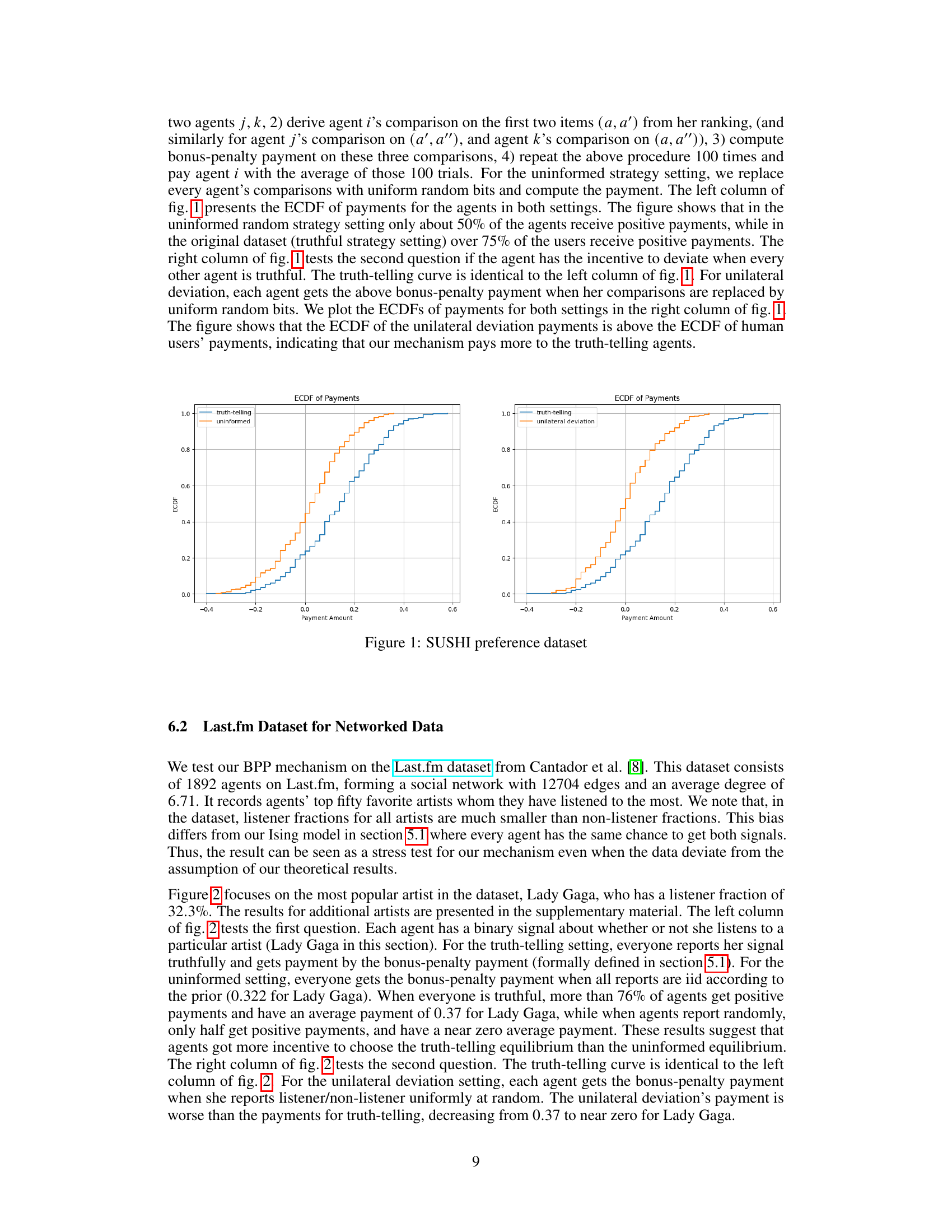

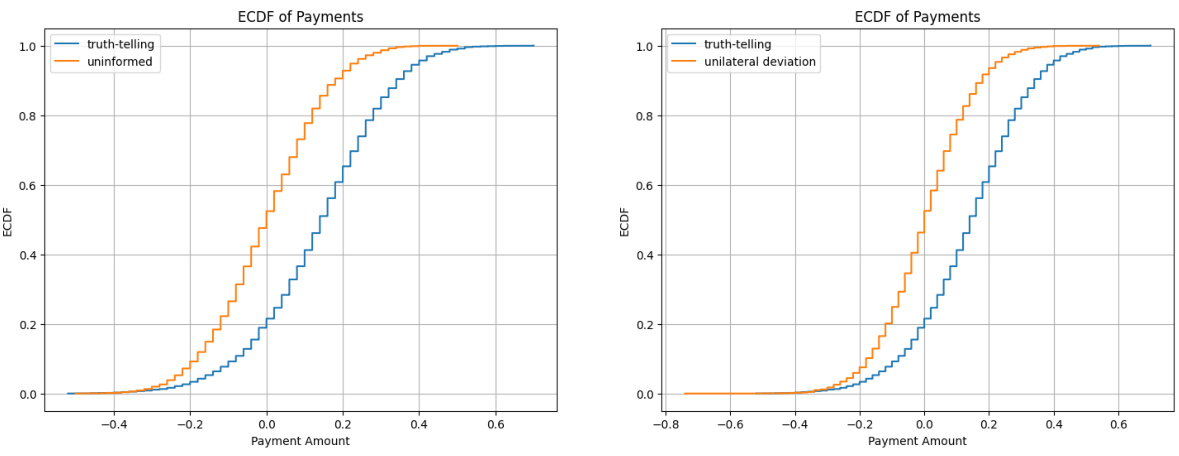

This figure shows the empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDFs) of agents’ payments under three different settings: truth-telling, uninformed, and unilateral deviation. The left column compares truth-telling and uninformed settings, demonstrating that truth-telling yields significantly better payments. The right column compares truth-telling and unilateral deviation, showcasing that truth-telling remains incentivized even when others are truthful.

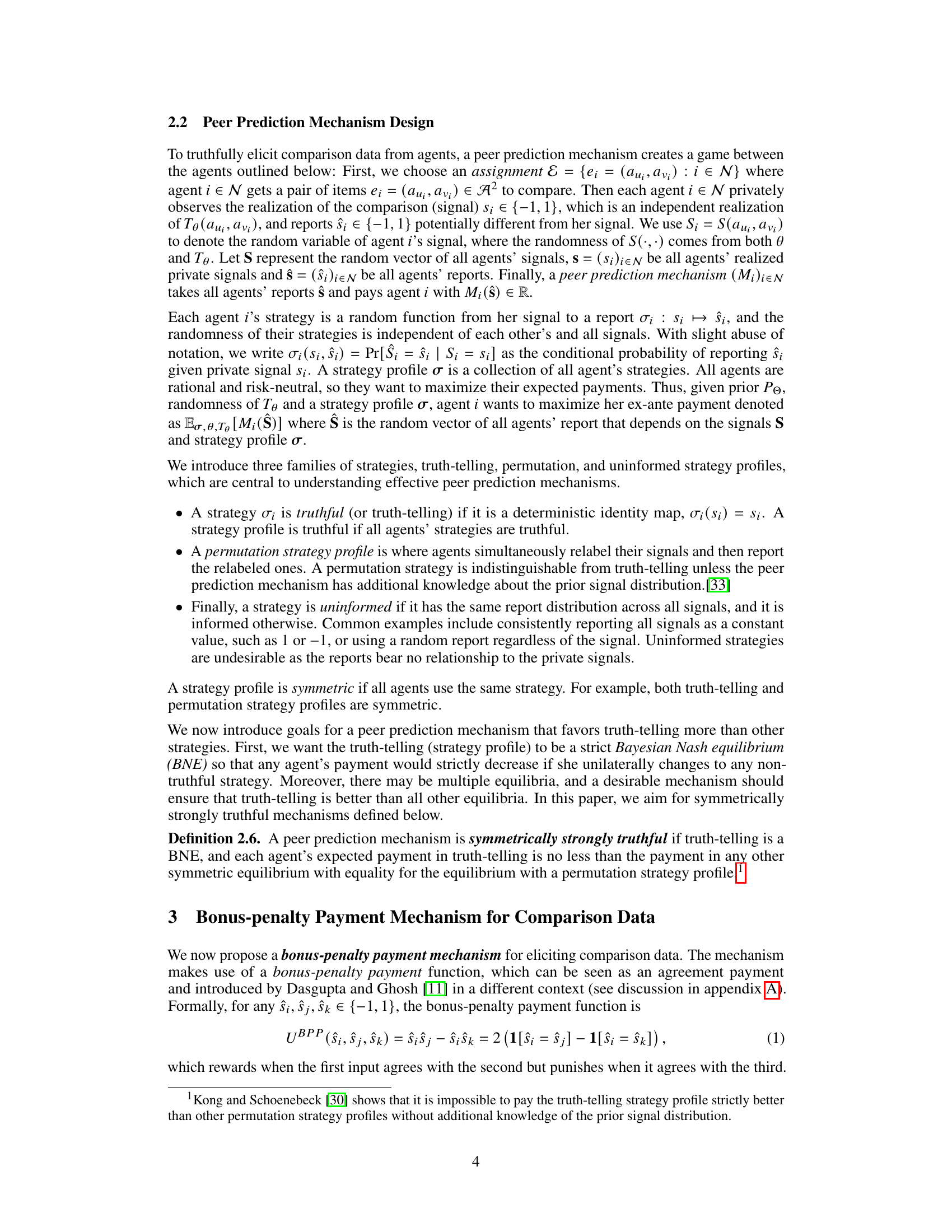

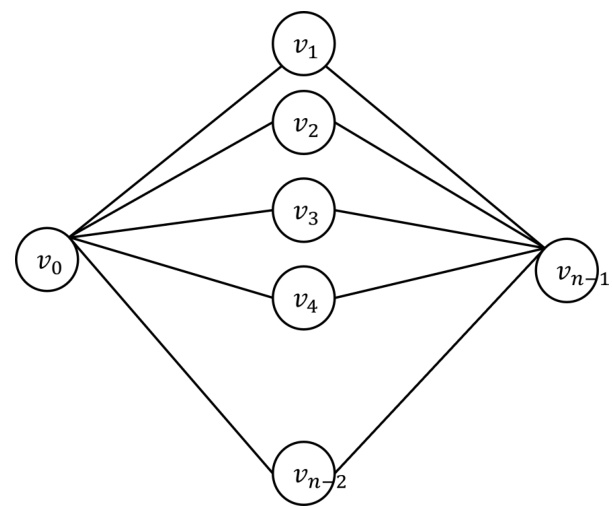

This figure demonstrates a graph where nodes v0 and vn-1 are not directly connected but share n common friends (v1 to vn-2). The caption highlights that the correlation between v0 and vn-1 increases as n grows larger, while the correlation between v0 and its direct neighbors (v1 to vn-2) remains relatively unchanged. This illustrates a key aspect of the Ising model used in the paper regarding correlations and distances within a network.

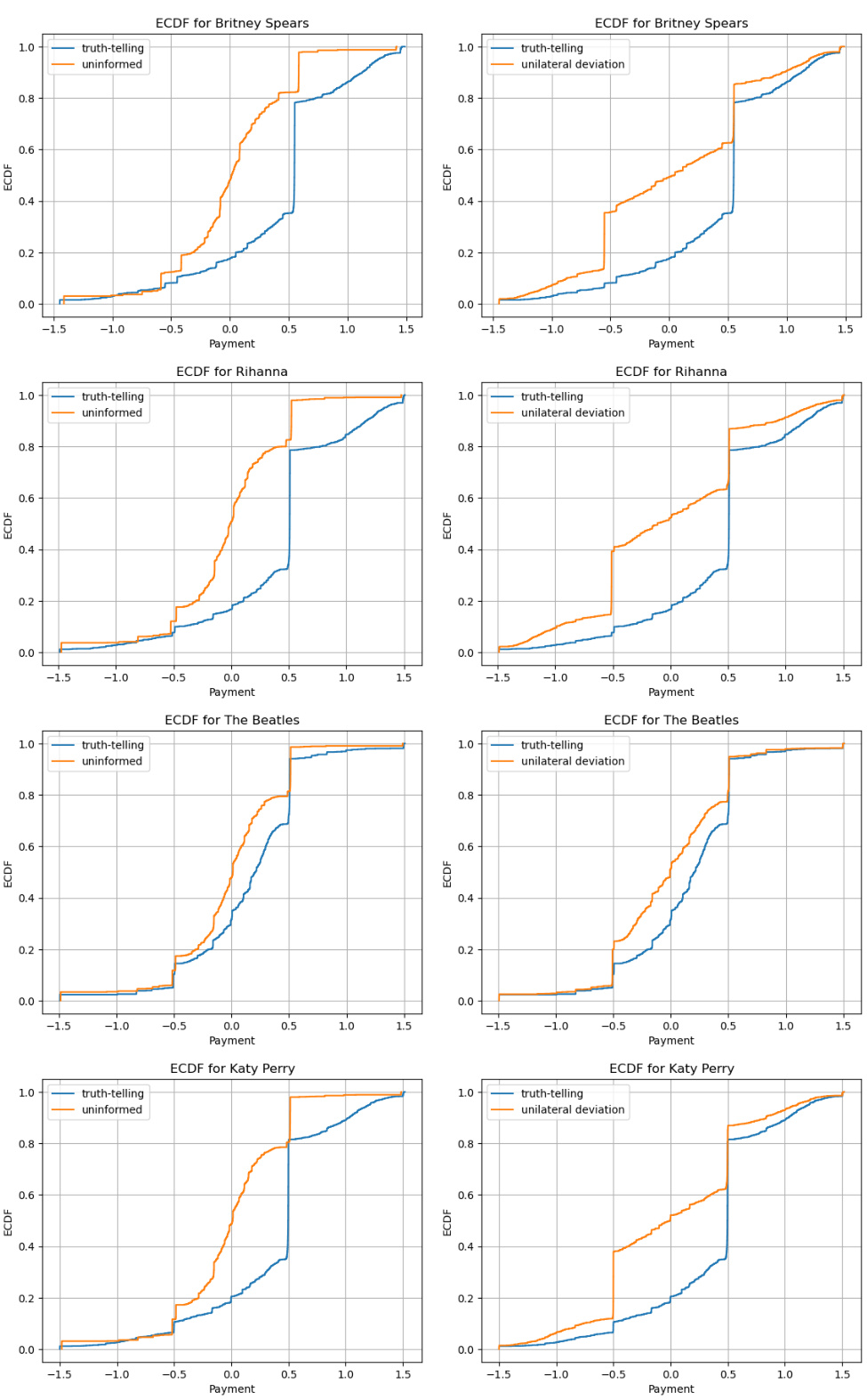

This figure presents empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDFs) of agents’ payments under three different settings: truth-telling, uninformed, and unilateral deviation. The left panel compares the truth-telling setting to the uninformed setting (where agents’ reports are random). The right panel compares the truth-telling setting to a unilateral deviation setting (where one agent reports randomly, while the rest report truthfully). The plots show the distribution of payments received by the agents in these settings, illustrating that truthful reporting leads to better payments compared to reporting randomly or deviating unilaterally. This supports the mechanism’s incentive properties in eliciting truthful comparison data.

The figure shows the empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF) of payments for agents under three different settings: truth-telling, uninformed, and unilateral deviation. The left column shows the ECDF of payments when all agents either report truthfully or report randomly. The right column shows the ECDF of payments when one agent deviates from the truth-telling strategy while all others report truthfully. The results demonstrate that our mechanism provides better rewards when all agents report truthfully, and incentivizes truth-telling when all others are truthful.

The figure shows the empirical cumulative distribution function (ECDF) of payments for agents under three settings: truth-telling, uninformed, and unilateral deviation. The left column demonstrates that truth-telling yields significantly more positive payments than the uninformed setting. The right column shows that unilateral deviation results in lower payments compared to the truth-telling setting, providing evidence that the mechanism incentivizes truthful reporting.

This figure shows the empirical cumulative distribution functions (ECDFs) of agents’ payments under three different settings: truth-telling, uninformed, and unilateral deviation. The left column compares truth-telling and uninformed settings, while the right column compares truth-telling and unilateral deviation. The results demonstrate that truthful reporting leads to better payments for agents.

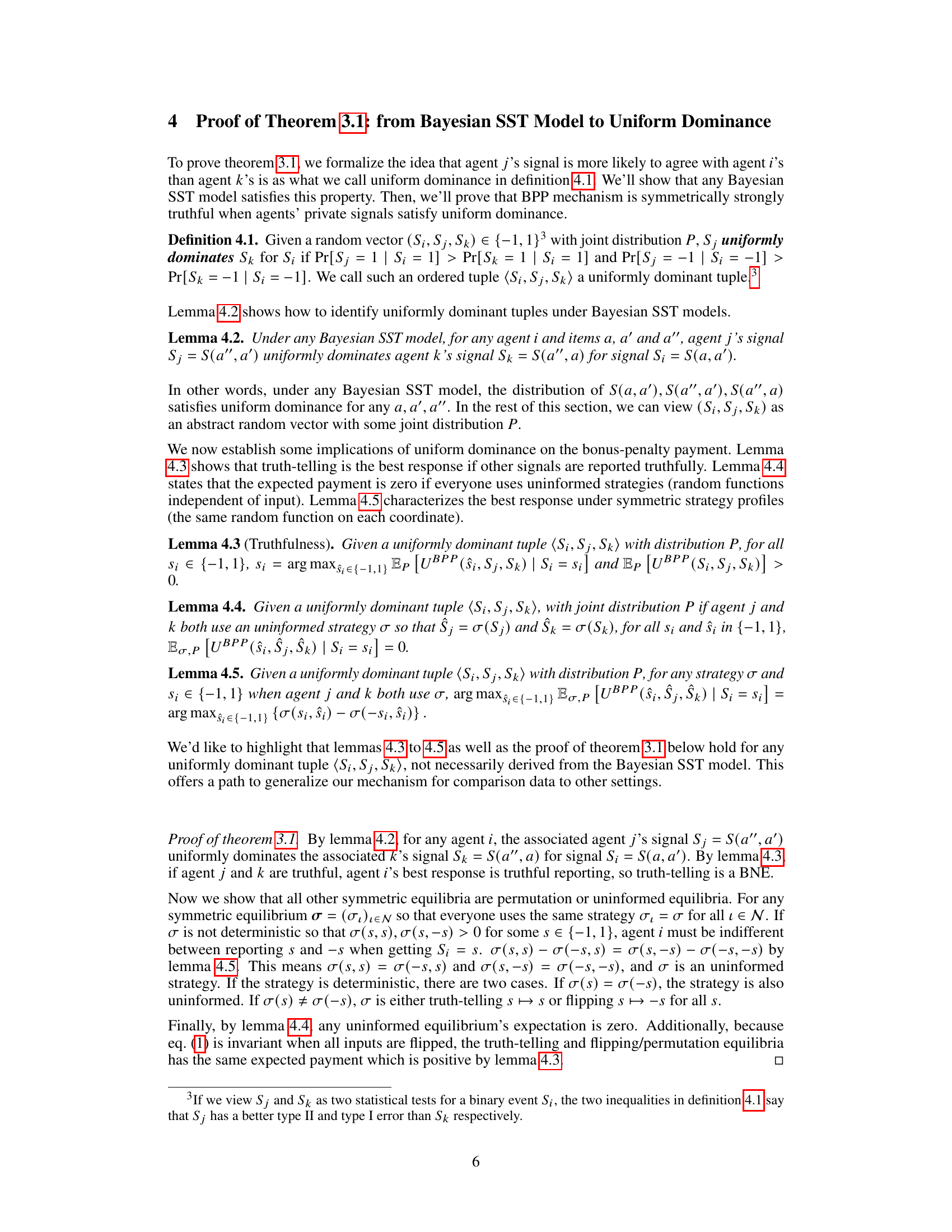

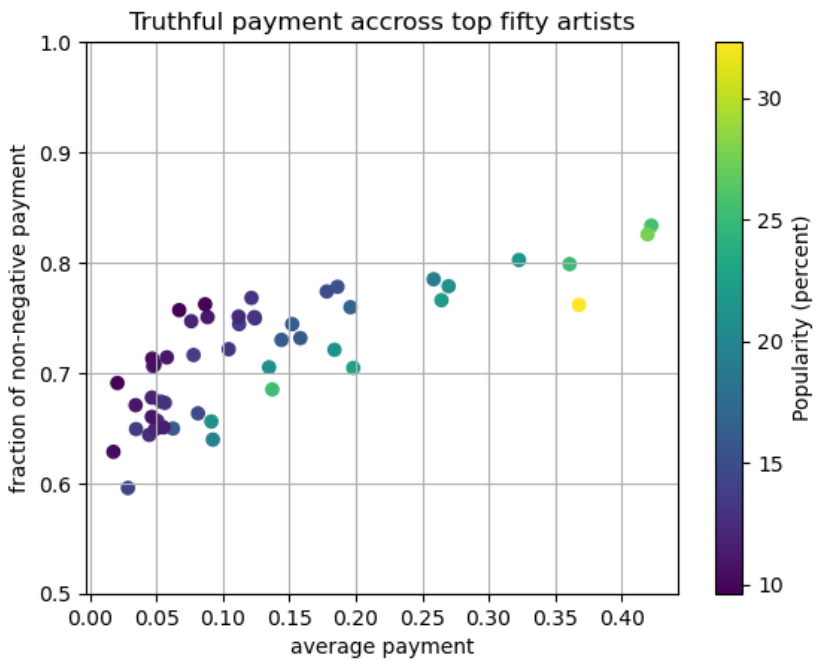

This figure shows the relationship between the average truthful payment and the fraction of agents receiving non-negative payments for the top 50 most popular artists in the Last.fm dataset. The color of each point represents the popularity (percentage of listeners) of the artist. The plot suggests that as artist popularity increases, both the average payment and the fraction of agents with non-negative payments tend to increase, although there’s some variability.

More on tables

This table presents the results of an experiment on the SUSHI dataset, focusing on different user groups based on various criteria like gender, age, and location. It shows the number of users, average utility, and the fraction of users who received a positive payment when truth-telling was employed in the bonus-penalty payment mechanism. The selection criteria varied across different groups to test the robustness of the mechanism.

This table presents the results of an experiment on the SUSHI dataset with different user selection criteria. For each criterion (e.g., female users aged 30-49 from Kanto/Shizuoka), it shows the number of users included, their average utility (payment) under a truthful strategy, and the percentage of those users who received a positive payment. The table helps demonstrate the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed mechanism under different user populations.

This table presents the results of an experiment on the Last.fm dataset, focusing on the top five most popular artists (excluding Lady Gaga). For each artist, it shows the fraction of listeners, the average utility obtained under truth-telling conditions, and the fraction of agents who received positive payments in the truth-telling setting. The results indicate the effectiveness of the bonus-penalty payment mechanism in incentivizing truthful reporting, even when the data deviates from the theoretical assumptions of the Ising model.

Full paper#