↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Decoding non-invasive brain recordings is crucial for understanding human cognition, but faces challenges due to individual differences and complex neural signals. Traditional methods often lack interpretability and require subject-specific models and extensive trials. This paper addresses these limitations by presenting a novel framework.

The framework integrates 3D brain structures with visual semantics using Vision Transformer 3D and Large Language Models. This unified feature extractor efficiently aligns fMRI features with multiple levels of visual embeddings, eliminating the need for subject-specific models and enabling extraction from single-trial data. The integration with LLMs enhances decoding, enabling tasks such as brain captioning, complex reasoning, and visual reconstruction. The method demonstrates superior performance across these tasks, enhancing interpretability and broadening the applicability of non-invasive brain decoding.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in neuroscience and AI because it significantly advances non-invasive brain decoding. Its integration of 3D brain structures with visual semantics using Vision Transformer 3D, and the incorporation of LLMs, offers a new approach to decoding complex brain activity. This opens doors for new applications in brain-computer interfaces and cognitive models, and inspires further research into multimodal brain-language interaction.

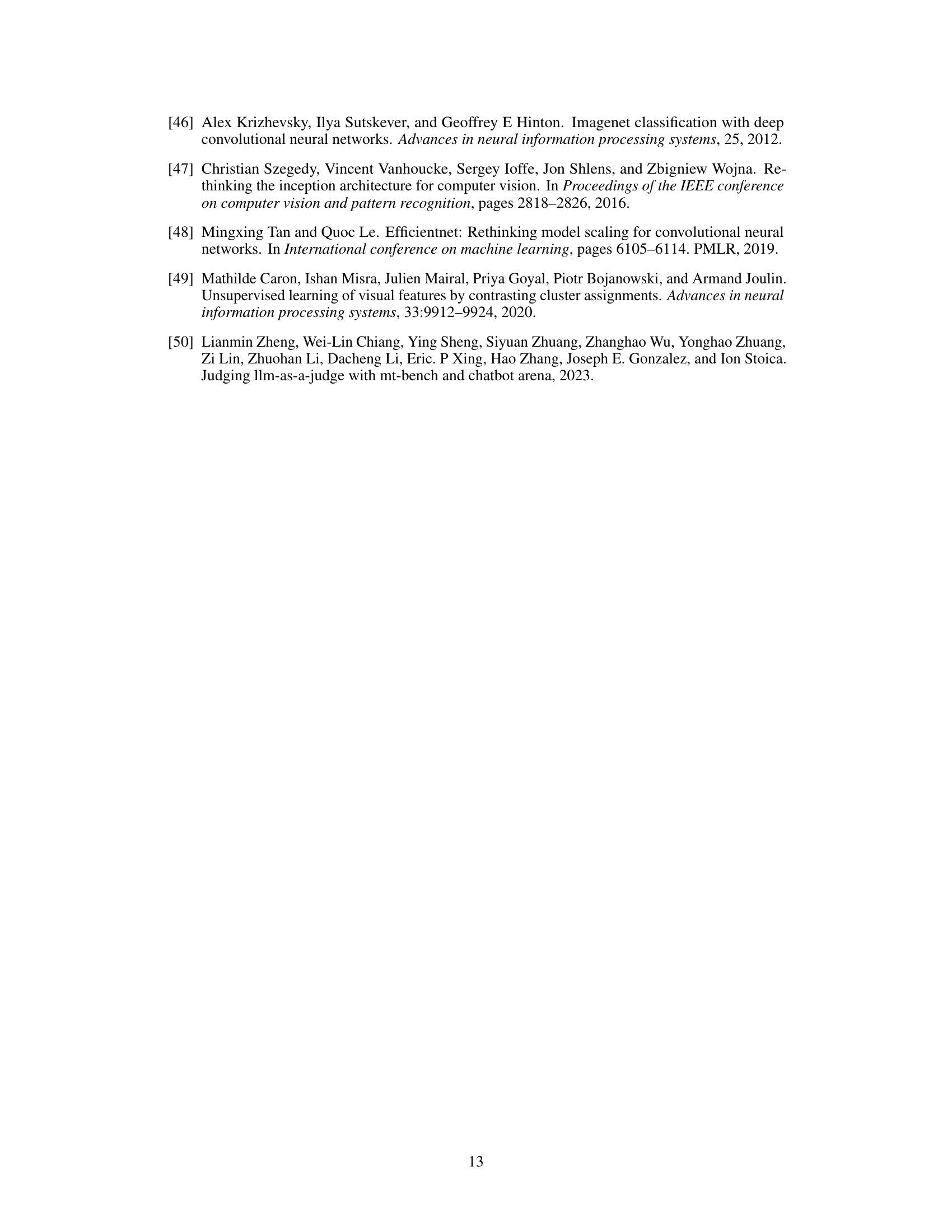

Visual Insights#

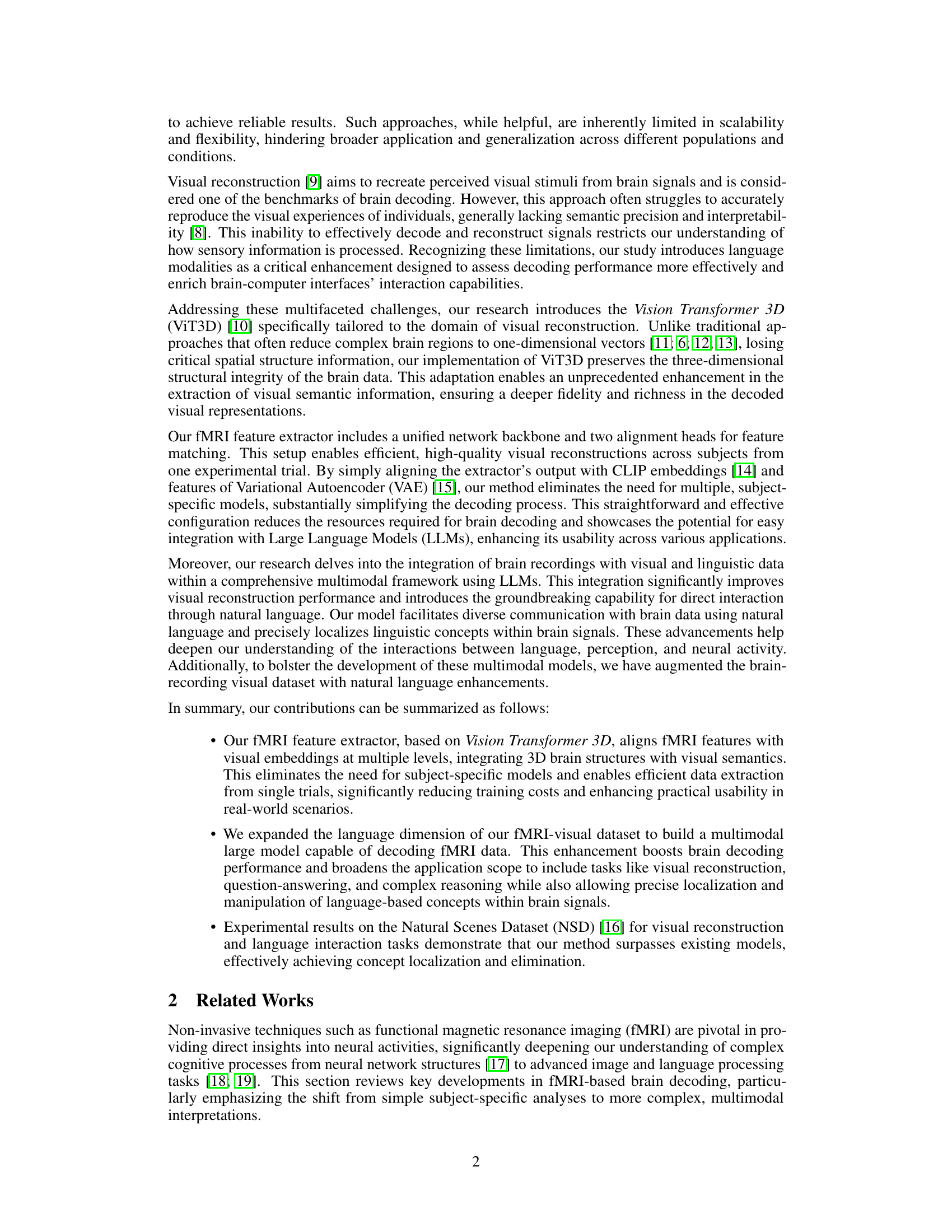

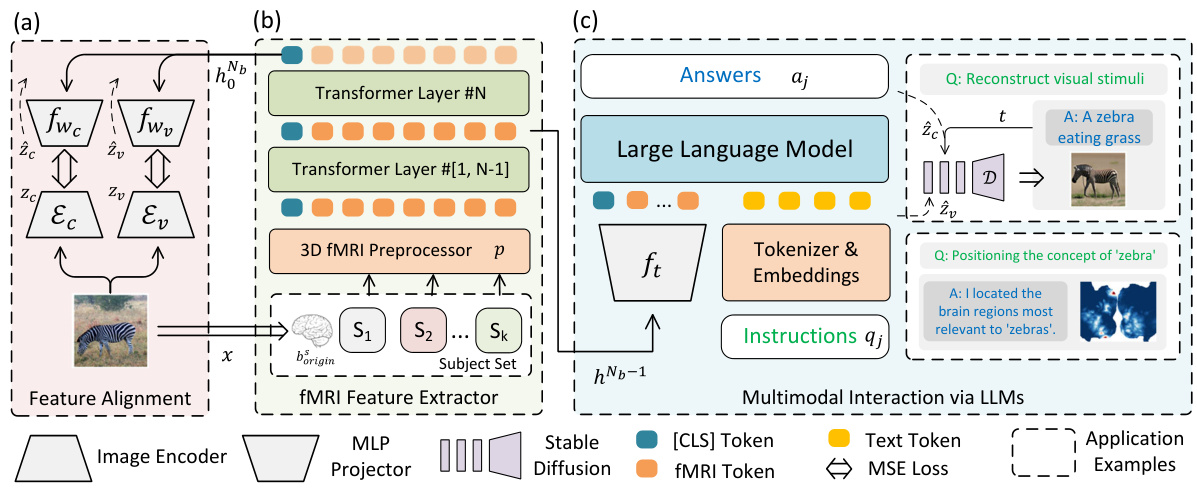

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed multimodal framework for fMRI-based visual reconstruction and language interaction. It shows three main components: a dual-stream fMRI feature extractor that aligns fMRI features with visual embeddings from VAE and CLIP, a 3D fMRI preprocessor for efficient data handling, and a multimodal LLM that integrates fMRI features for natural language interactions, enabling tasks such as visual reconstruction, question-answering, and complex reasoning. The dual-stream feature extractor enables alignment with CLIP and VAE embeddings efficiently, simplifying integration with LLMs. The fMRI preprocessor employs a trilinear interpolation and patching strategy to preserve the 3D structural information, and the multimodal LLM facilitates interactions via natural language instructions and generation of text or image responses.

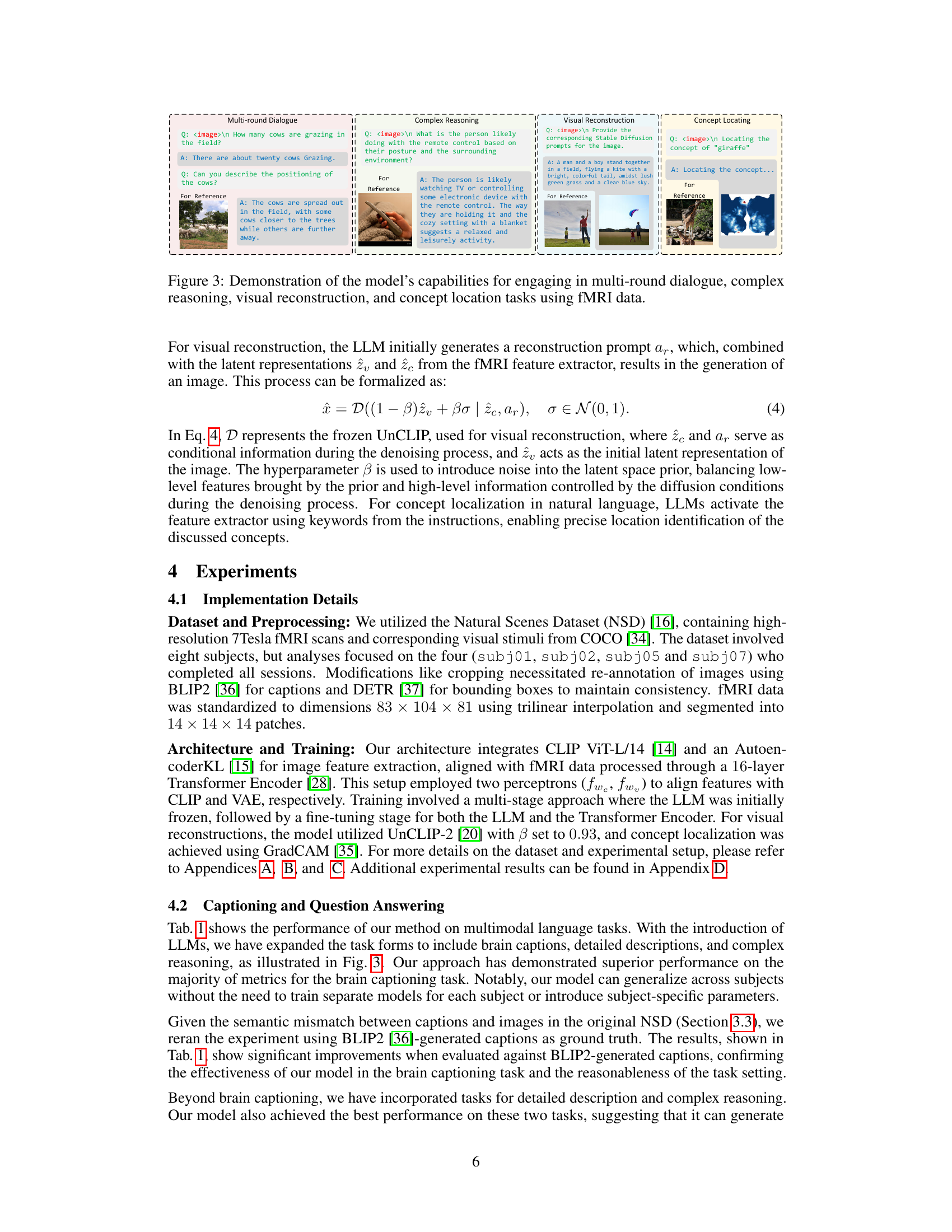

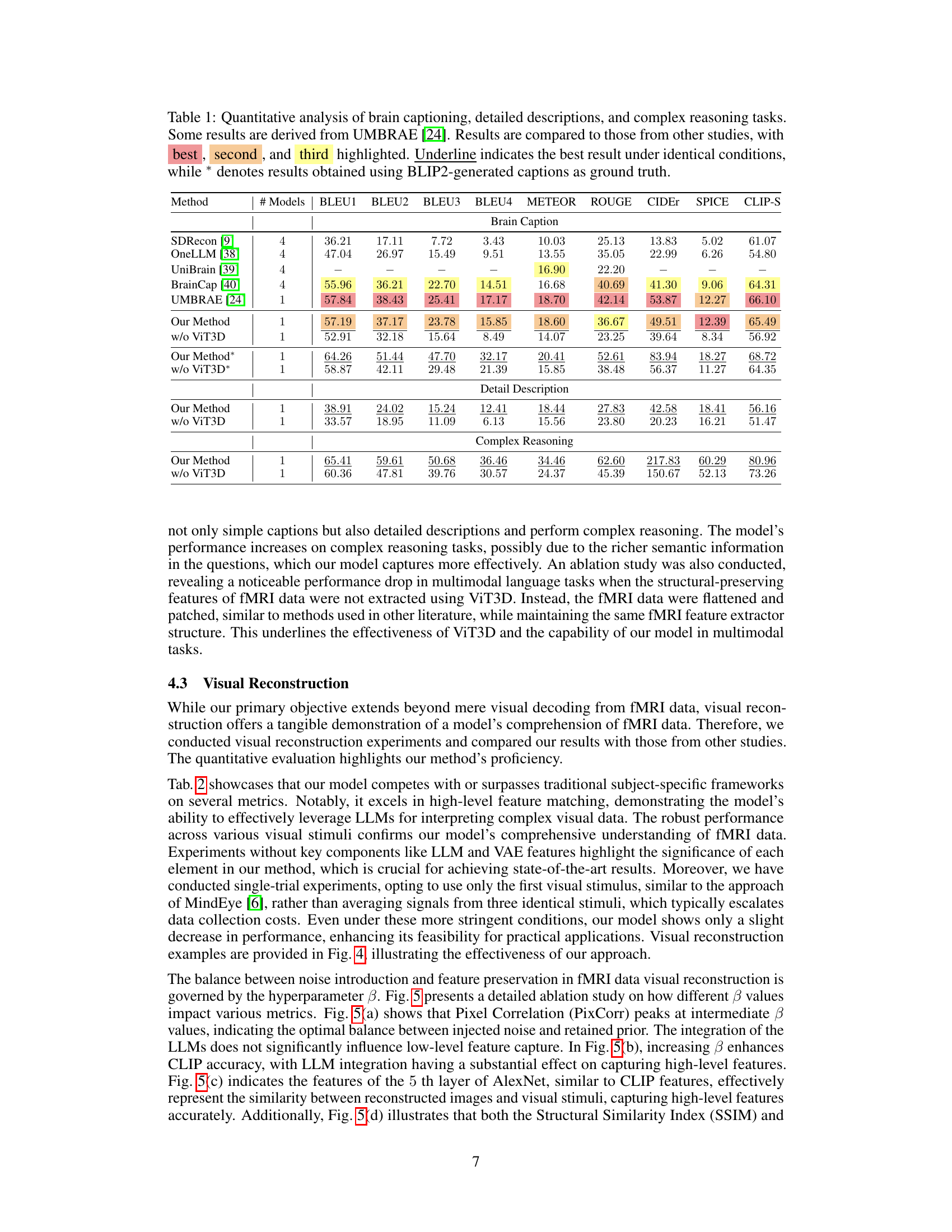

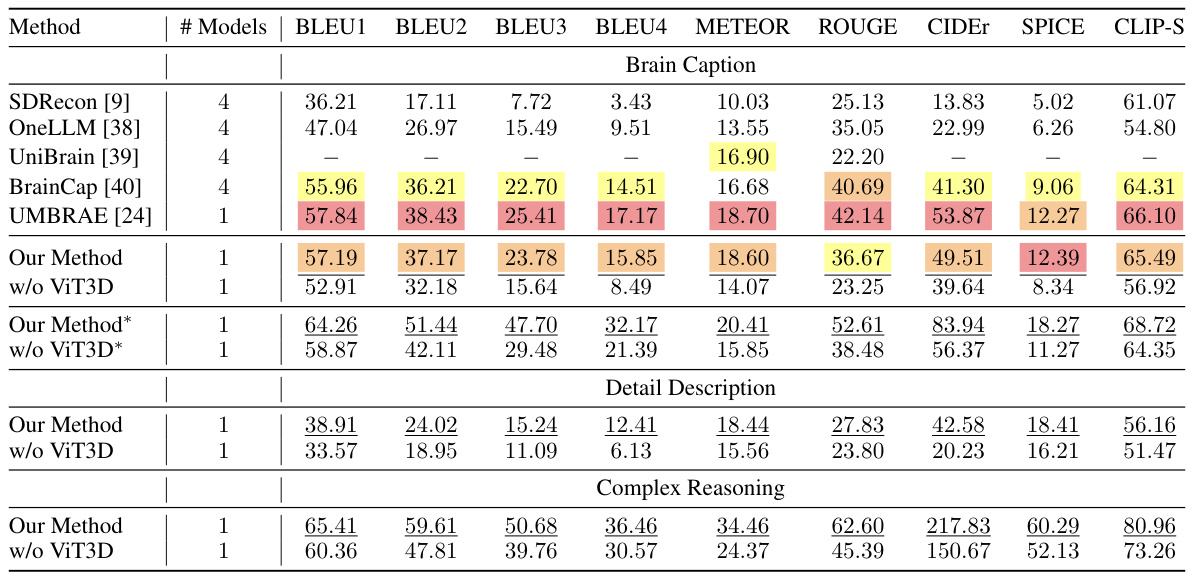

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method’s performance on three tasks: brain captioning, detailed description generation, and complex reasoning, using various evaluation metrics (BLEU, METEOR, ROUGE, CIDEr, SPICE, CLIP-S). It compares the performance against several state-of-the-art methods. The results are broken down to show the impact of using the Vision Transformer 3D (ViT3D) component of the model and show results using BLIP2-generated captions as a ground truth for more accurate comparisons.

In-depth insights#

Neuro-Vision Fusion#

Neuro-Vision Fusion represents a significant advancement in brain-computer interfaces by directly integrating neural data with visual information. The core idea is to bridge the gap between brain activity and visual perception using sophisticated computational models. This integration allows for a more nuanced understanding of how the brain processes visual stimuli, moving beyond simple reconstruction tasks. The fusion isn’t just about reconstructing images from fMRI data; it’s about understanding the semantic content of those images as interpreted by the brain. By incorporating Large Language Models (LLMs), the system gains the ability to describe, reason about, and interact with the decoded visual information using natural language. This significantly enhances interpretability and opens avenues for advanced applications in cognitive neuroscience and human-computer interaction. The success of this approach relies on the effective alignment of fMRI data with multiple levels of visual embedding, ensuring accuracy and generalizability across different subjects. Challenges remain in scaling to larger datasets and addressing issues around individual differences in brain structure and function, yet Neuro-Vision Fusion points toward a future where brain activity can be seamlessly translated into meaningful visual and linguistic interactions.

ViT3D fMRI Decoder#

A ViT3D fMRI decoder represents a significant advancement in brain-computer interface (BCI) technology. By leveraging the power of 3D Vision Transformers, it overcomes limitations of traditional fMRI decoding methods that often simplify complex brain structures into 1D representations, losing crucial spatial information. This architectural choice allows for more precise and accurate alignment of fMRI data with visual semantics, leading to improved visual reconstruction capabilities and enhanced interpretability. The integration of a unified network backbone further streamlines the decoding process, reducing computational costs and making the system more efficient and scalable. This decoder’s ability to handle single-trial data also reduces the need for extensive training and multiple experimental trials, making it more practical for real-world applications. Furthermore, its seamless integration with LLMs opens exciting possibilities for more advanced language-based interactions with brain signals, expanding the range of applications in neuroscience research, cognitive modeling, and advanced BCIs.

LLM-Enhanced Decoding#

LLM-enhanced decoding represents a significant advancement in brain-computer interface (BCI) research. By integrating large language models (LLMs) with fMRI data processing, researchers can achieve more accurate and interpretable decoding of brain activity. LLMs bring the ability to handle complex linguistic structures and contextual information, which is crucial in translating nuanced brain signals into meaningful outputs such as visual reconstructions or natural language descriptions. This multimodal approach not only improves the precision and accuracy of decoding, but it also significantly enhances the interpretability of results, offering valuable insights into the neural processes underlying cognition. The integration of LLMs bridges the gap between raw neurological data and human-understandable language, paving the way for more sophisticated BCIs with potentially far-reaching applications in healthcare, neuroscience, and human-computer interaction. The challenges lie in handling the high dimensionality and variability of fMRI data, requiring robust preprocessing and alignment techniques; however, the potential benefits of LLM-enhanced decoding make it a promising avenue of future research.

Multimodal Interaction#

The concept of “Multimodal Interaction” in this context signifies the sophisticated integration of diverse data modalities—brain recordings (fMRI), visual data (images), and linguistic data (natural language)—to enhance the understanding and interpretation of cognitive processes. The approach goes beyond simply combining these modalities; it leverages a powerful framework that allows for seamless alignment and interaction between fMRI features and visual-linguistic embeddings. This unified approach enables the model to perform complex tasks, such as visual reconstruction from brain activity and natural language interaction with brain signals. This integration is particularly impactful because it addresses limitations of previous methods, offering improved interpretability and generalization across individuals. The core strength lies in its ability to translate complex brain patterns into meaningful linguistic representations, bridging the gap between neural activity and human-understandable concepts. A key enabling factor is the use of Large Language Models (LLMs), which facilitate both intricate reasoning capabilities and the generation of nuanced responses. This multimodal fusion is key to unlocking deeper insights into the relationship between perception, language, and neural processes.

Future Directions#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore enhanced multimodal integration by incorporating additional sensory modalities like audio or tactile data alongside fMRI and language. This would enrich the model’s understanding of cognitive processes and improve the accuracy of visual reconstruction and language interaction. Further investigation into generalizability across diverse populations is crucial; the current model’s performance needs to be rigorously evaluated on more heterogeneous datasets, including those with varied demographic characteristics and neurological conditions. Addressing computational constraints is also important, as the high computational demands of the current approach limit scalability and real-time applications. Research into optimized algorithms and architectures would significantly improve efficiency. Finally, exploring the ethical implications of decoding increasingly complex information from brain activity, and establishing robust safeguards for data protection and responsible use, is vital to ensure ethical and trustworthy applications of this technology.

More visual insights#

More on figures

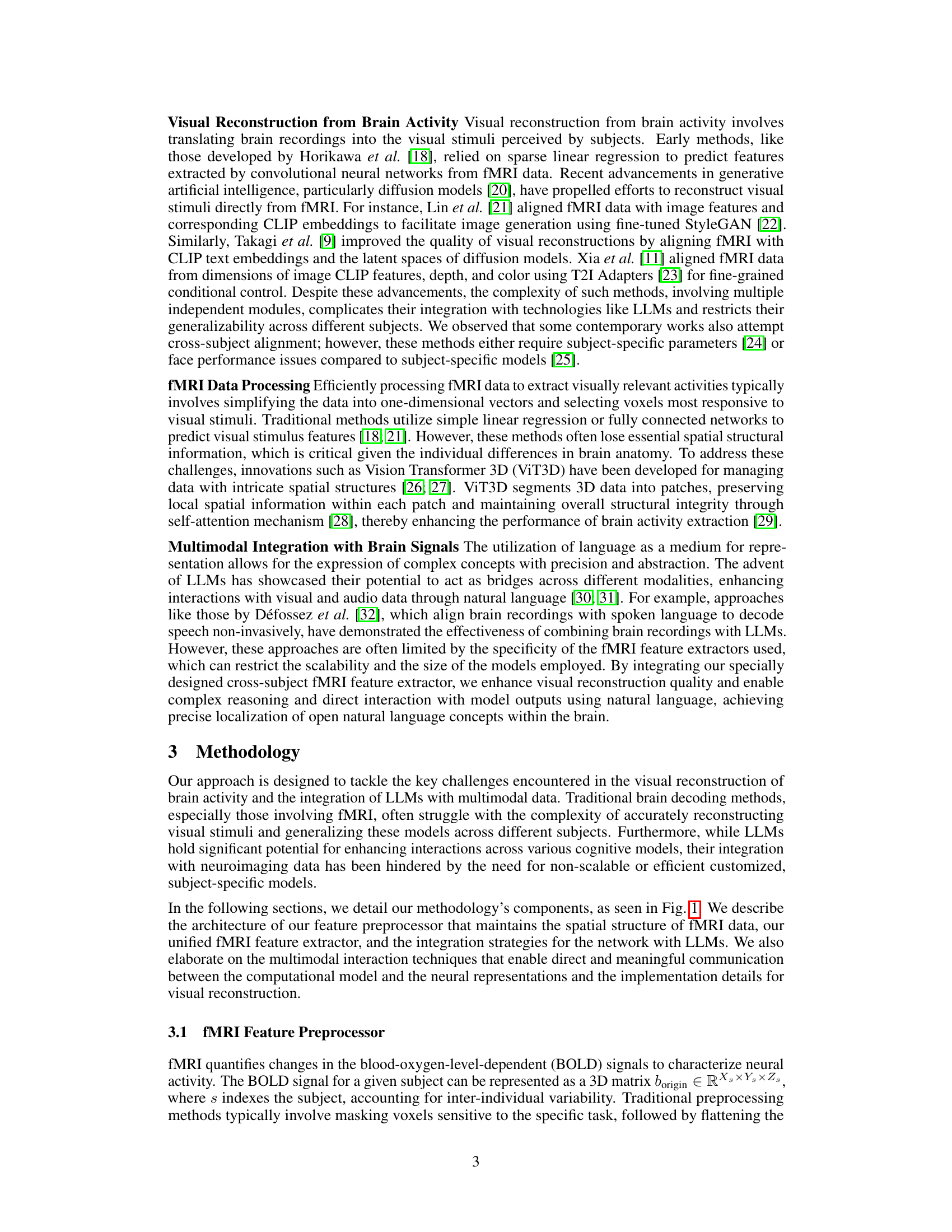

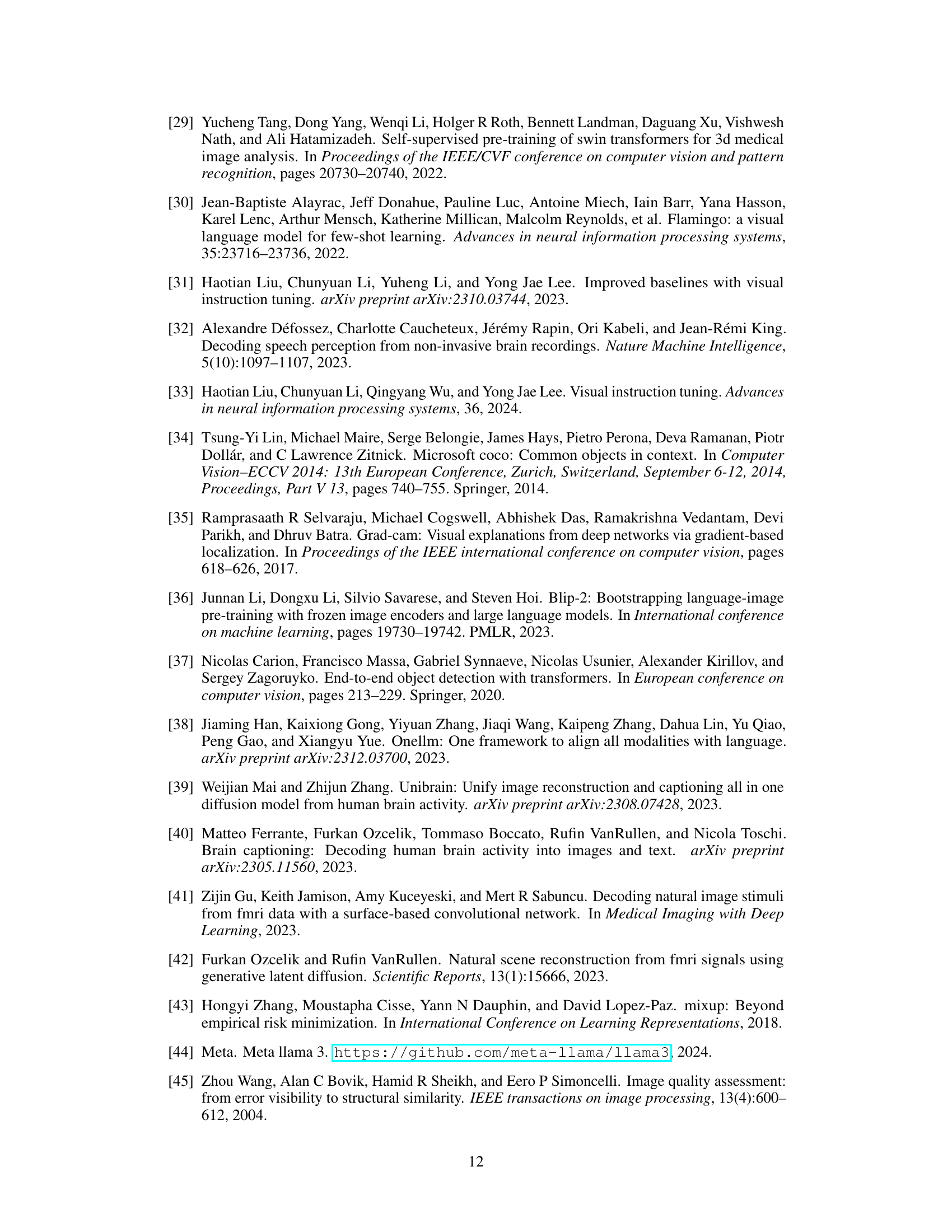

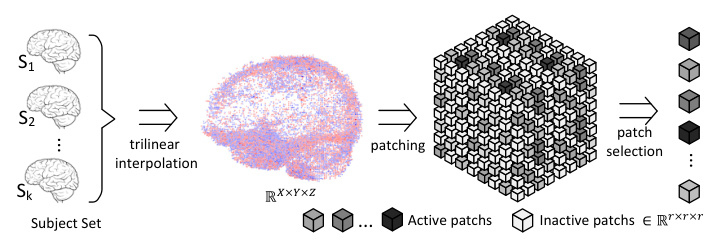

This figure illustrates the preprocessing steps applied to fMRI data before feeding it into the model. It begins with a set of fMRI scans from multiple subjects (S1, S2…Sk). First, trilinear interpolation is used to resize the data to a consistent, uniform size (R x X x Y x Z). Next, the data is divided into small cubic patches. Finally, patches that are considered irrelevant (inactive patches) are filtered out, leaving only the active patches that contain important information for the analysis. This process maintains the spatial structure of the data, crucial for accurate analysis and consistency across subjects.

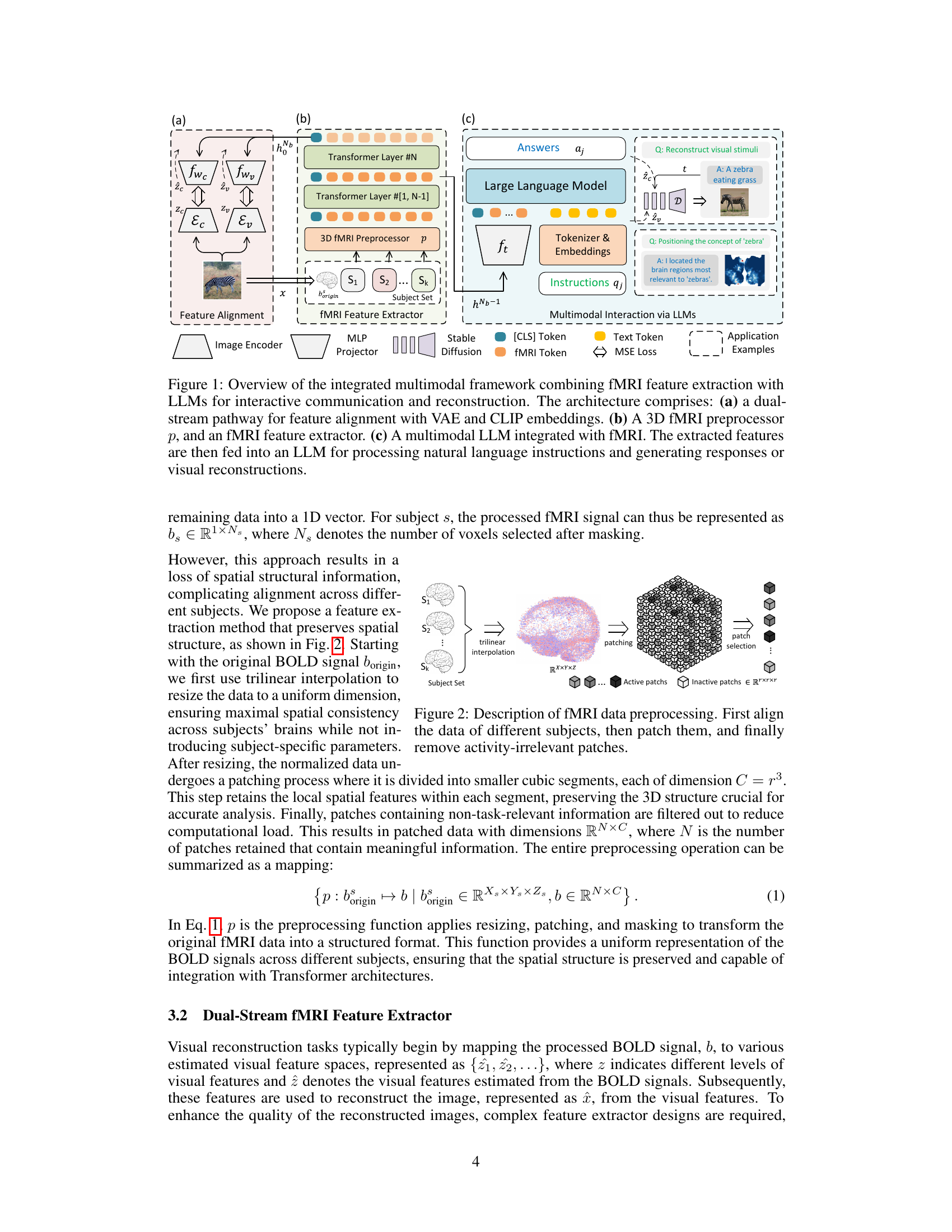

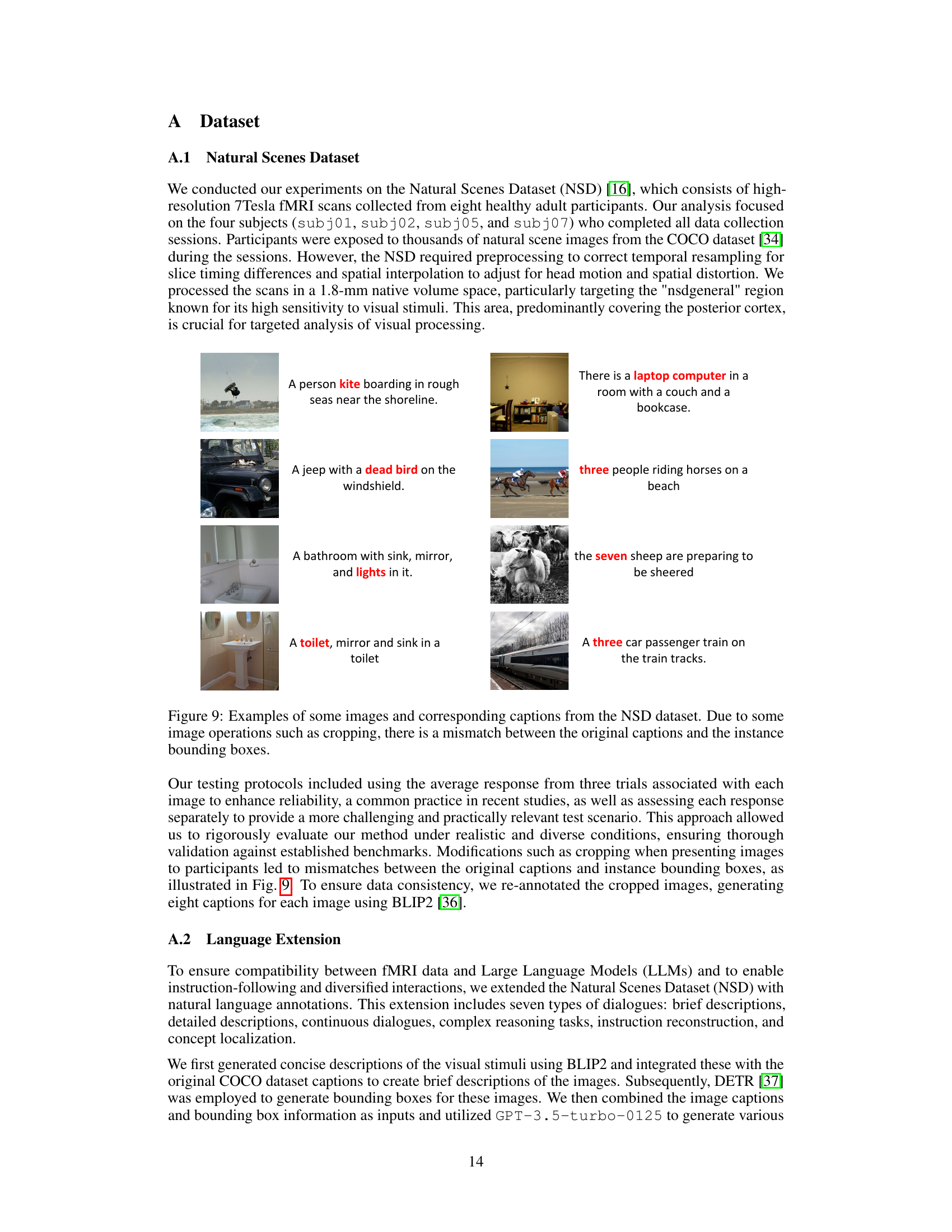

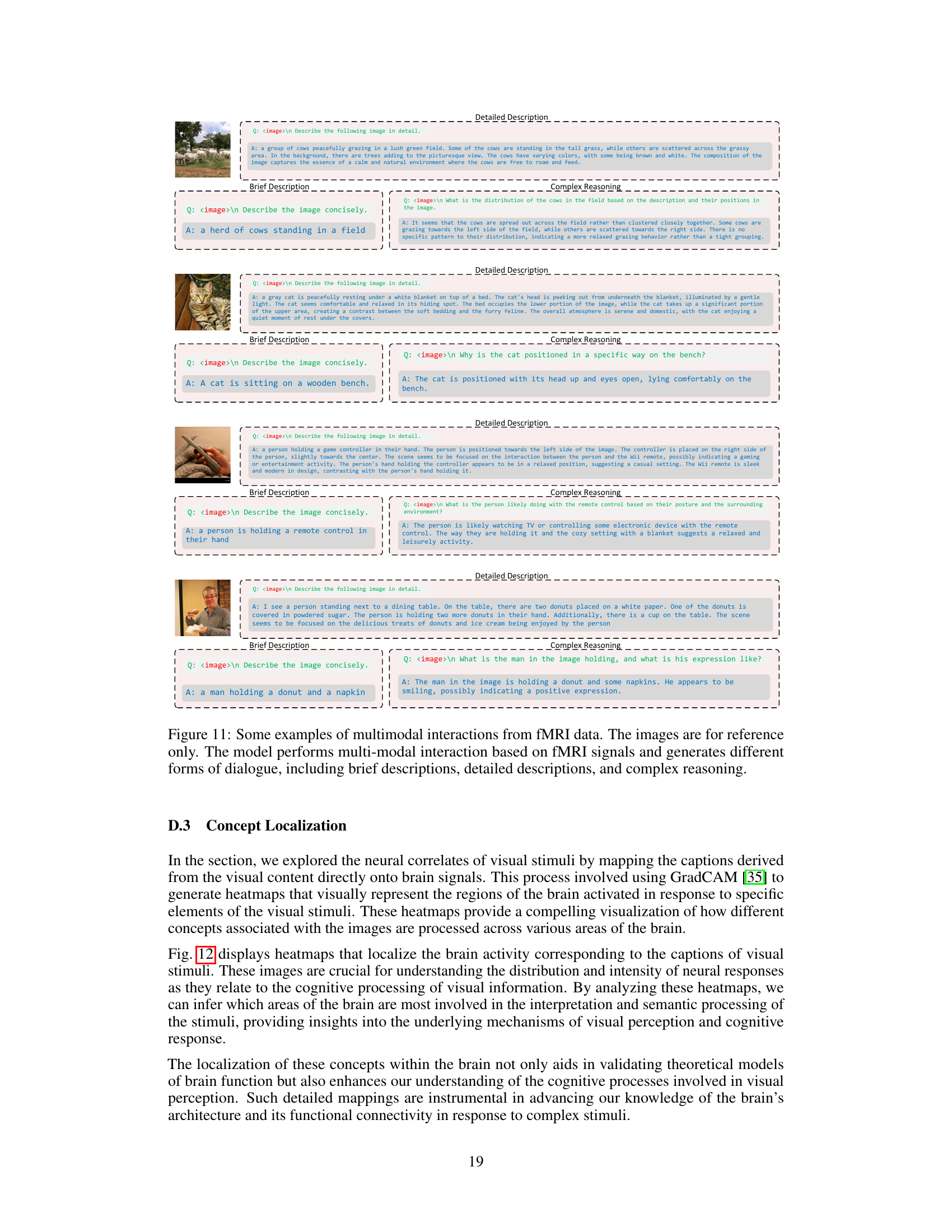

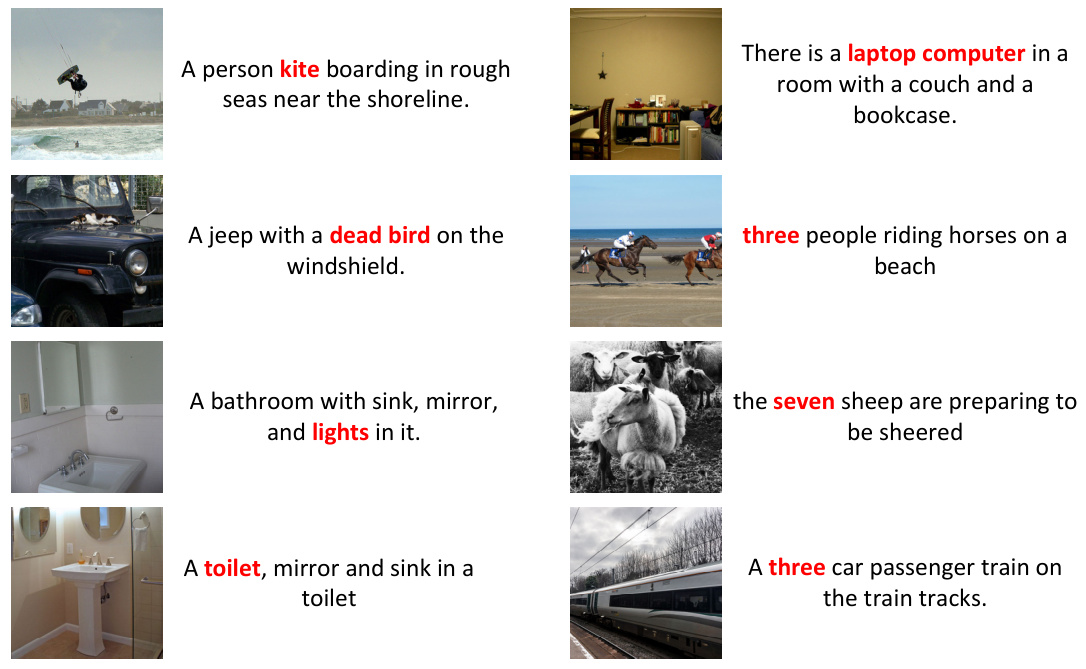

This figure showcases the model’s performance across four key tasks using fMRI data: (1) Multi-round Dialogue: The model demonstrates its ability to engage in extended conversations related to the visual stimuli. (2) Complex Reasoning: The model is tested on its capacity to answer complex questions related to the visual scene requiring inference and reasoning. (3) Visual Reconstruction: The model reconstructs the visual stimuli from the fMRI brain scans, demonstrating its ability to translate brain activity into visual representations. (4) Concept Locating: The model identifies and locates specific concepts from the visual stimuli within the brain signals. Each task includes a question, answer, and an image for visual reference, demonstrating the different capabilities of the model.

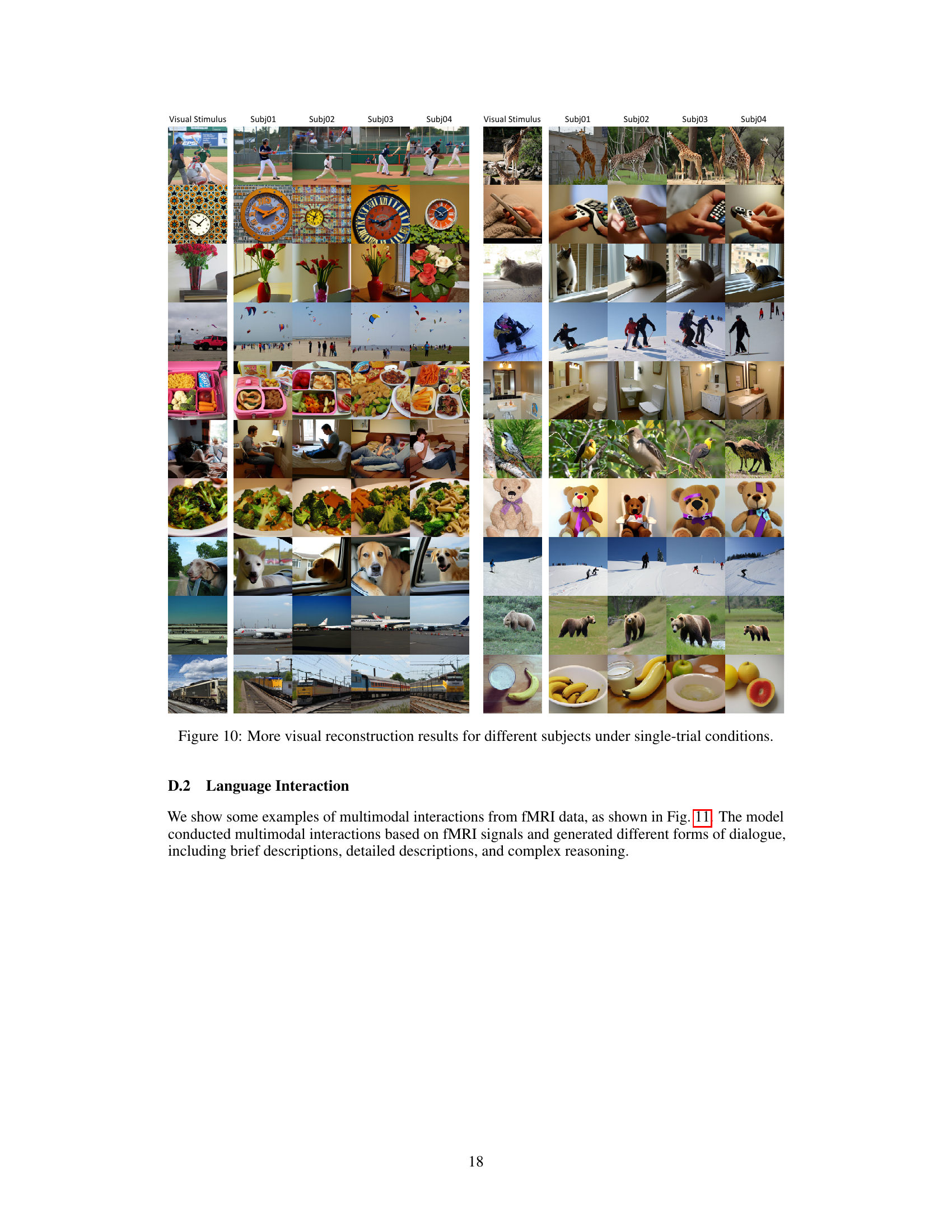

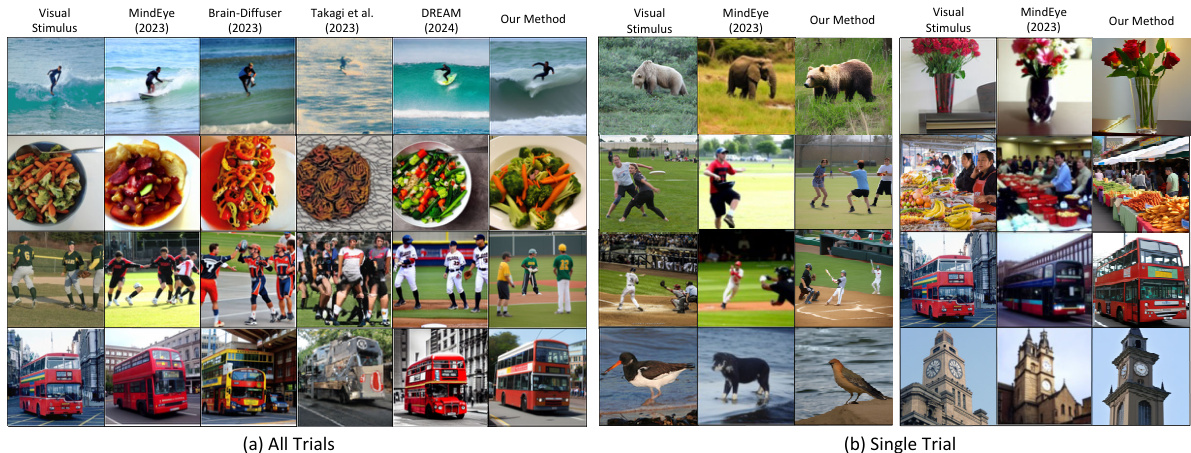

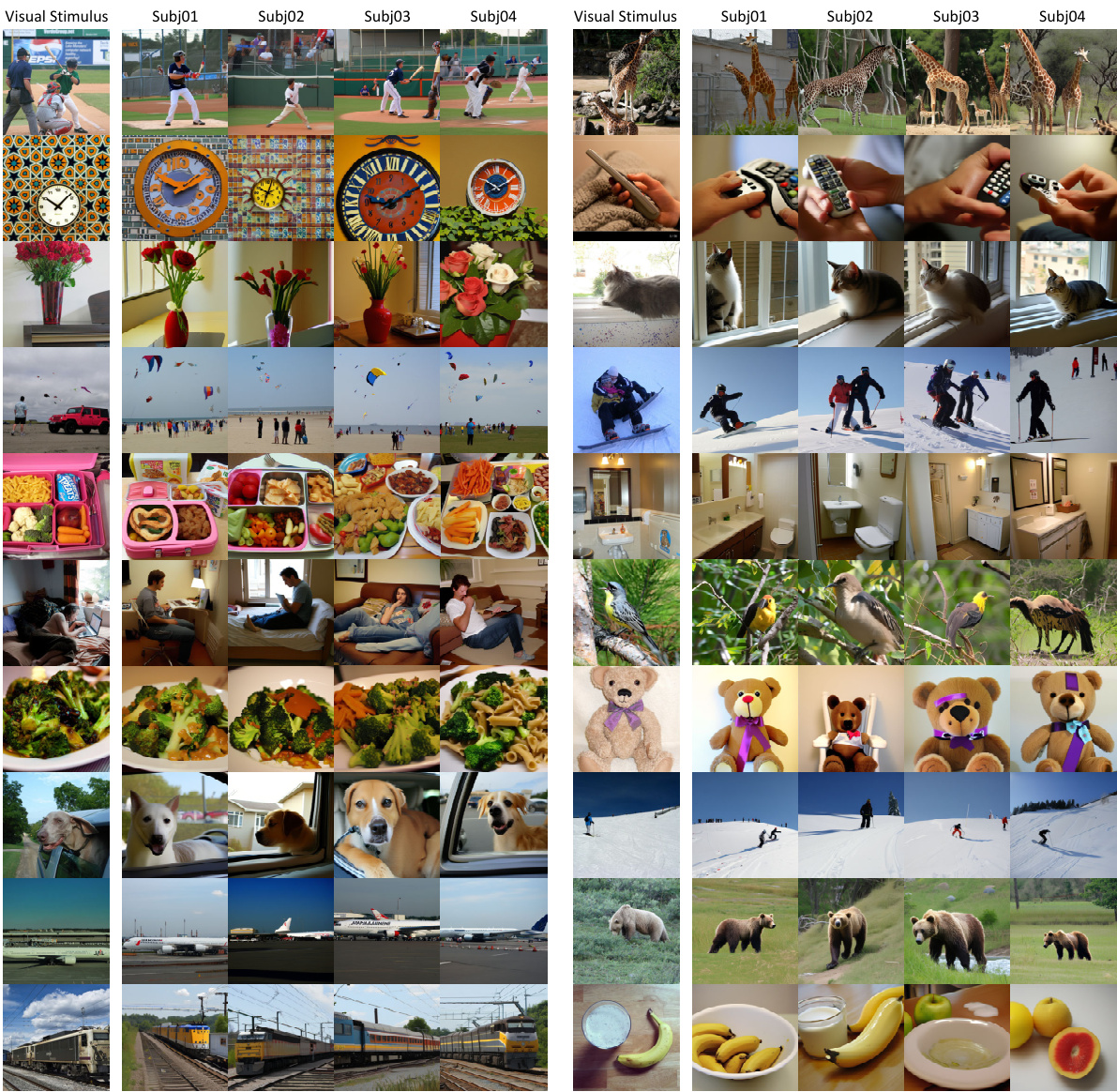

This figure compares visual reconstruction results from the proposed method and three other methods (MindEye, Brain-Diffuser, Takagi et al., DREAM) across different visual stimuli. The left-hand side (a) shows results when averaging the fMRI signal across multiple trials for each stimulus. The right-hand side (b) shows results obtained using only the first trial’s fMRI response, representing a more challenging and realistic single-trial scenario. The figure demonstrates that the proposed method produces visually accurate and consistent reconstruction results under both conditions, highlighting its effectiveness in real-world scenarios.

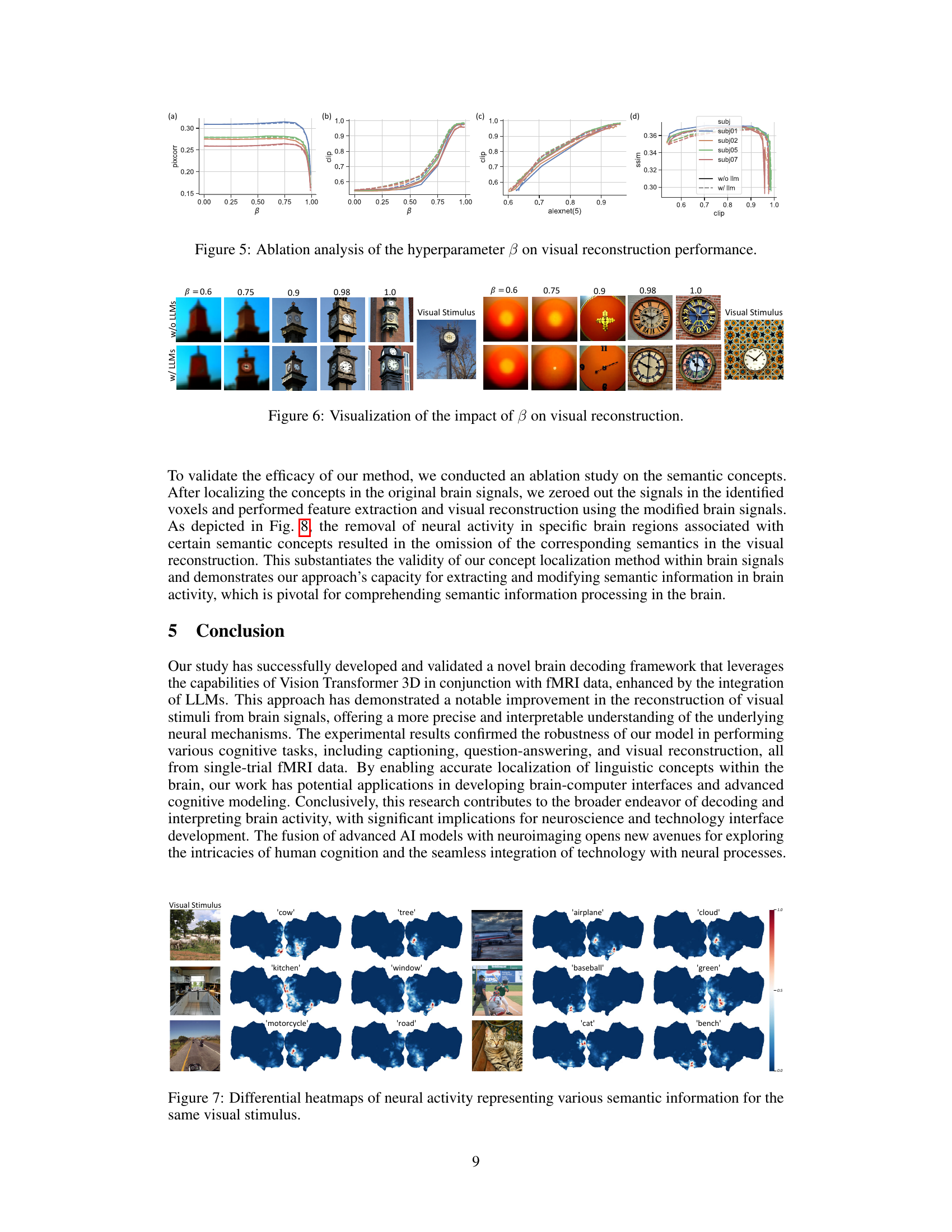

This figure presents an ablation study on the impact of the hyperparameter β on visual reconstruction performance. It shows four subfigures: (a) Pixel Correlation (PixCorr) vs. β, (b) CLIP score vs. β, (c) AlexNet(5) score vs. β, and (d) SSIM vs. CLIP score. Each subfigure shows the performance for four different subjects (subj01, subj02, subj05, and subj07) with and without LLMs. The results indicate that an optimal balance between noise and prior information is crucial for visual reconstruction, and that using LLMs improves performance especially for high-level features.

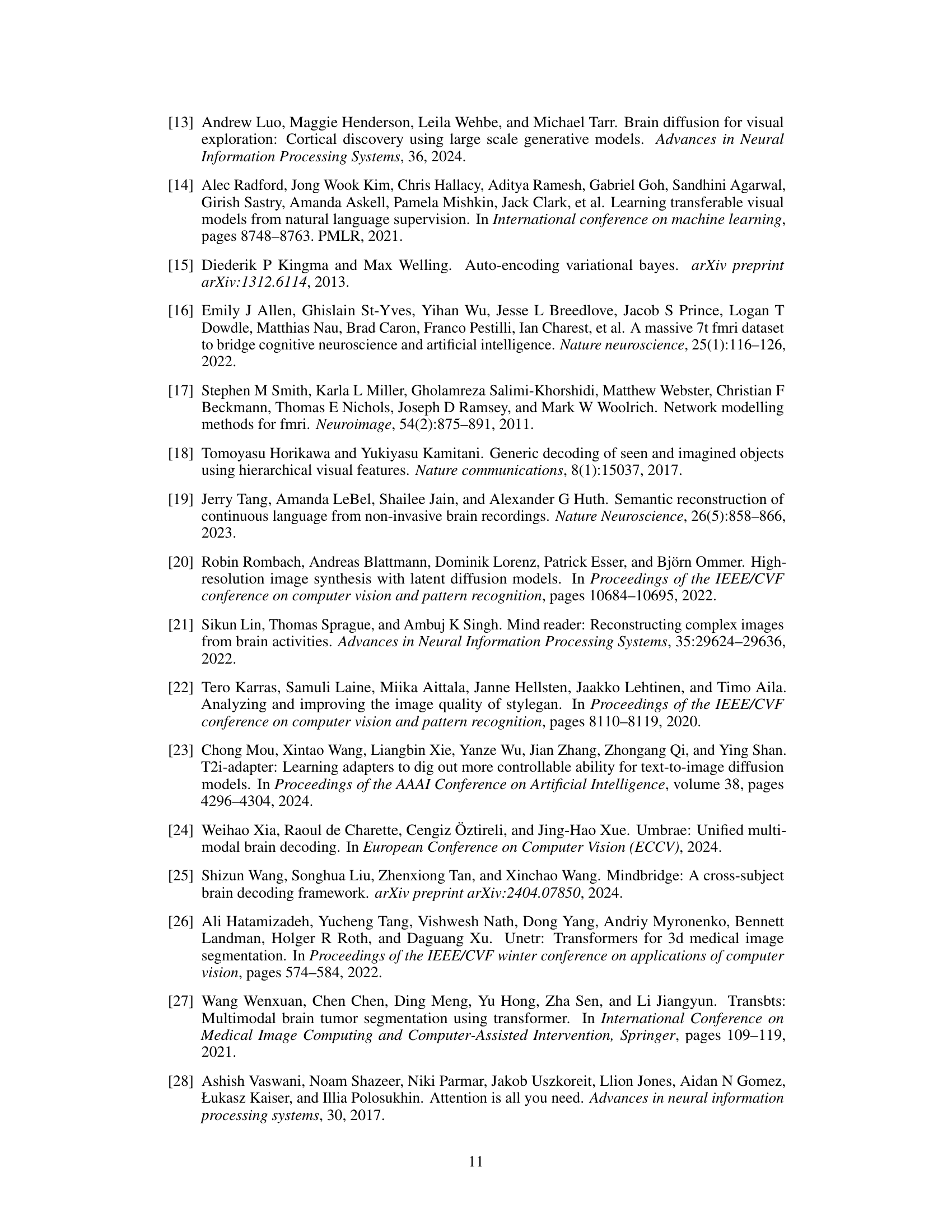

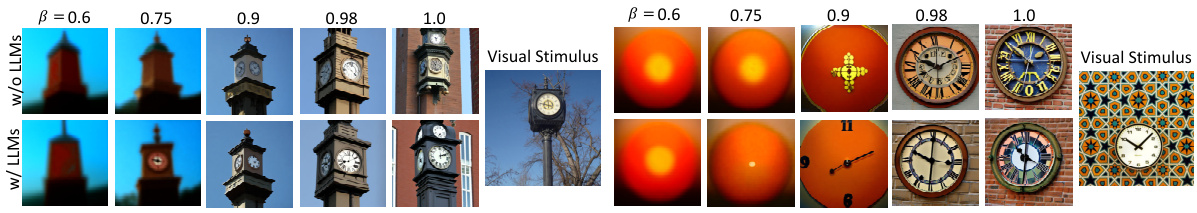

This figure shows the impact of the hyperparameter β on the visual reconstruction results. The top row displays reconstructions without LLMs, while the bottom row uses LLMs. Each column represents a different value of β (0.6, 0.75, 0.9, 0.98, 1.0). The visual stimuli are shown to the right. The figure demonstrates how changes in β affect image quality and the ability of the model to reconstruct fine details of the images.

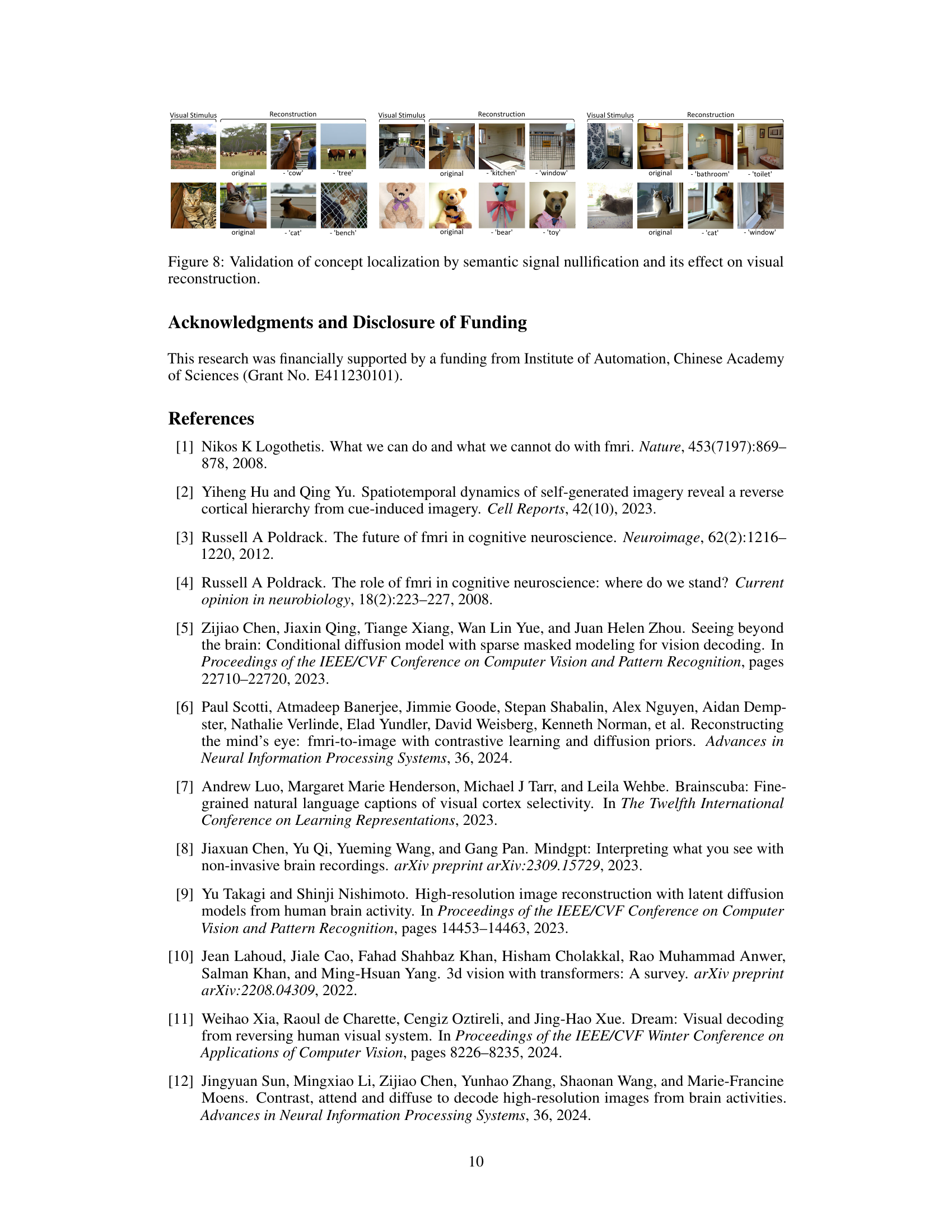

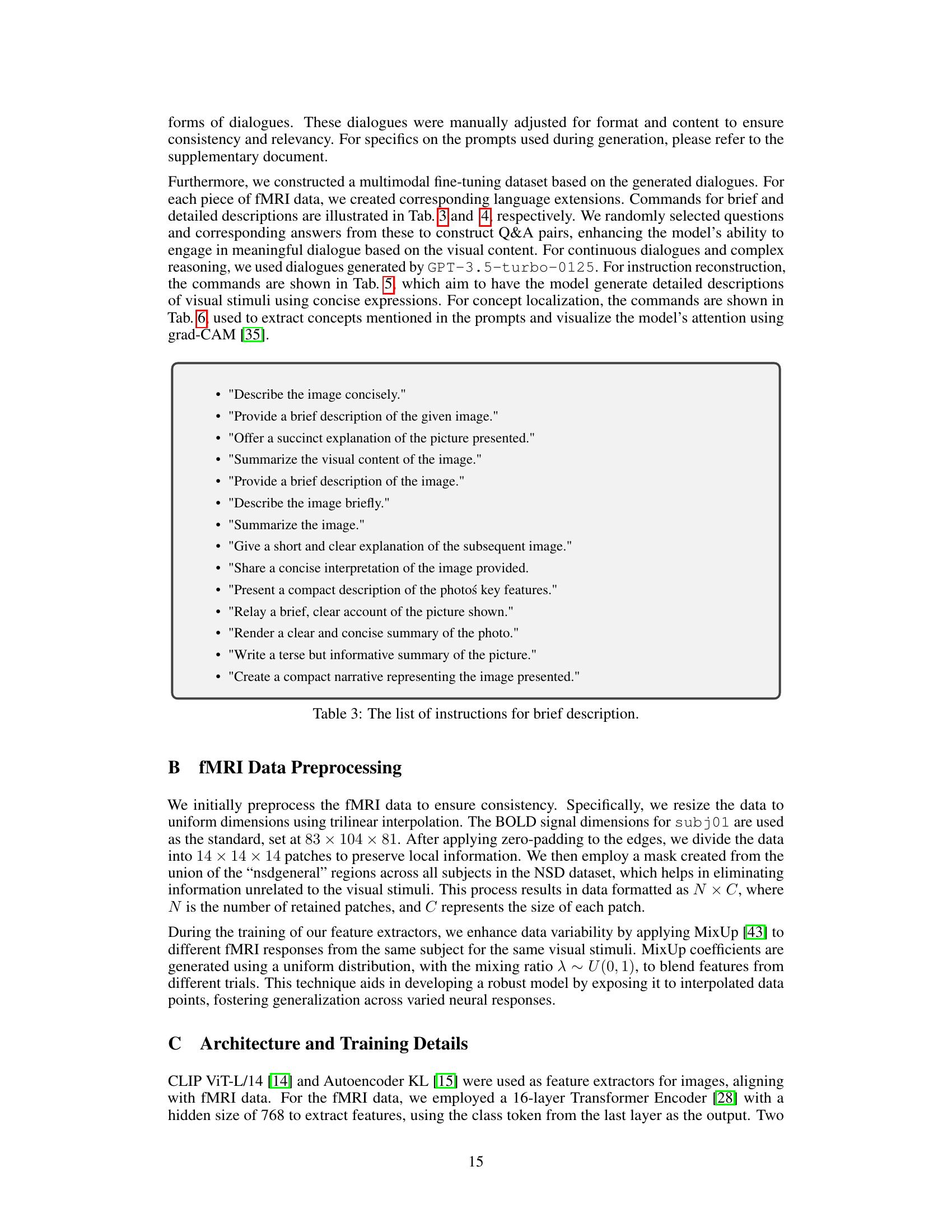

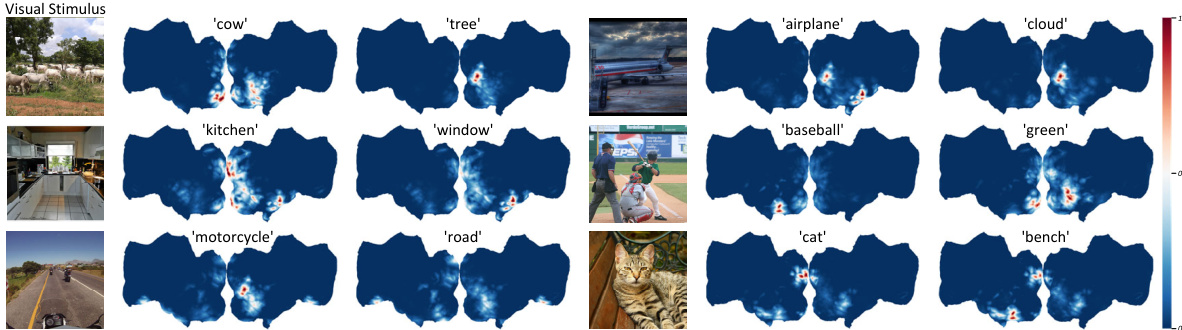

This figure visualizes the brain regions activated by specific concepts derived from visual stimuli. It uses heatmaps to show the spatial distribution of neural responses corresponding to different semantic concepts within the brain. Each row represents a different image from the dataset, and each column shows the activation heatmap for a specific caption related to that image. The heatmaps show that different concepts activate different regions of the brain, suggesting that our brain processes visual information in a distributed manner, assigning different brain areas to different concepts within a scene.

This figure shows the overall architecture of the proposed multimodal framework. It consists of three main components: a dual-stream fMRI feature extractor that aligns fMRI data with visual embeddings from VAE and CLIP, a 3D fMRI preprocessor for efficient data handling, and a multimodal LLM that integrates with the fMRI features for interactive communication and visual reconstruction. The framework allows for natural language interaction, enabling tasks such as brain captioning, complex reasoning, and visual reconstruction.

This figure shows the overall architecture of the proposed multimodal framework that combines fMRI feature extraction with Large Language Models (LLMs) for visual reconstruction and interactive communication. It highlights three key components: 1) A dual-stream pathway that aligns fMRI features with VAE and CLIP embeddings for efficient feature matching; 2) A 3D fMRI preprocessor and a feature extractor that preserves the spatial structure of fMRI data; and 3) A multimodal LLM that integrates with the extracted fMRI features to process natural language instructions and generate responses (text or images). This integrated approach enhances the capabilities of non-invasive brain decoding for a wide range of tasks.

This figure illustrates the proposed multimodal framework which combines fMRI feature extraction with large language models (LLMs) for interactive communication and visual reconstruction. It shows three key components: (a) a dual-stream pathway aligning fMRI features with visual embeddings from a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) and CLIP; (b) a 3D fMRI preprocessor and feature extractor; and (c) the integration of a multimodal LLM with the fMRI data for processing natural language instructions and generating either text-based responses or visual reconstructions. The framework emphasizes the efficient alignment of fMRI data with visual and linguistic information through a unified architecture.

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed multimodal framework. It shows three main components: (a) A dual-stream feature alignment module using Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and CLIP embeddings to align fMRI features with visual information. (b) A 3D fMRI preprocessor and feature extractor that preserves spatial information from the fMRI data using a Vision Transformer 3D model. (c) An LLM that integrates with the fMRI features to perform language-based tasks, such as generating responses to questions, visual reconstruction, and concept localization. The framework utilizes a combined approach of fMRI data and LLMs for advanced brain-computer interaction and cognitive modeling.

This figure shows a block diagram of the proposed multimodal framework for brain decoding. It combines fMRI feature extraction with LLMs to enable interactive communication and visual reconstruction. The framework has three main components: 1) a dual-stream pathway for aligning fMRI features with visual embeddings from VAE and CLIP; 2) a 3D fMRI preprocessor and feature extractor that preserves spatial information in fMRI data; 3) a multimodal LLM that integrates with fMRI features to process natural language instructions and generate responses (text or image).

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the proposed model, showing the integration of three main components: a dual-stream fMRI feature extractor that aligns fMRI data with visual embeddings from VAE and CLIP; a 3D fMRI preprocessor for efficient data handling; and a multimodal LLM for interactive communication and visual reconstruction. The dual-stream feature extractor efficiently aligns fMRI features with multiple levels of visual embeddings, eliminating the need for subject-specific models. The preprocessor maintains the 3D structural integrity of the fMRI data. The LLM integrates the extracted features, enabling natural language interactions and various tasks, such as visual reconstruction and concept localization.

This figure visualizes the results of concept localization within brain signals. Heatmaps are shown for various visual stimuli, each overlaid with a heatmap representing the brain activation patterns corresponding to specific captions describing those stimuli. The color intensity in the heatmaps indicates the strength of brain activation, allowing for the visualization of which brain regions are most strongly associated with specific concepts within the images. The figure demonstrates the spatial distribution of neural responses related to different visual semantic concepts.

More on tables

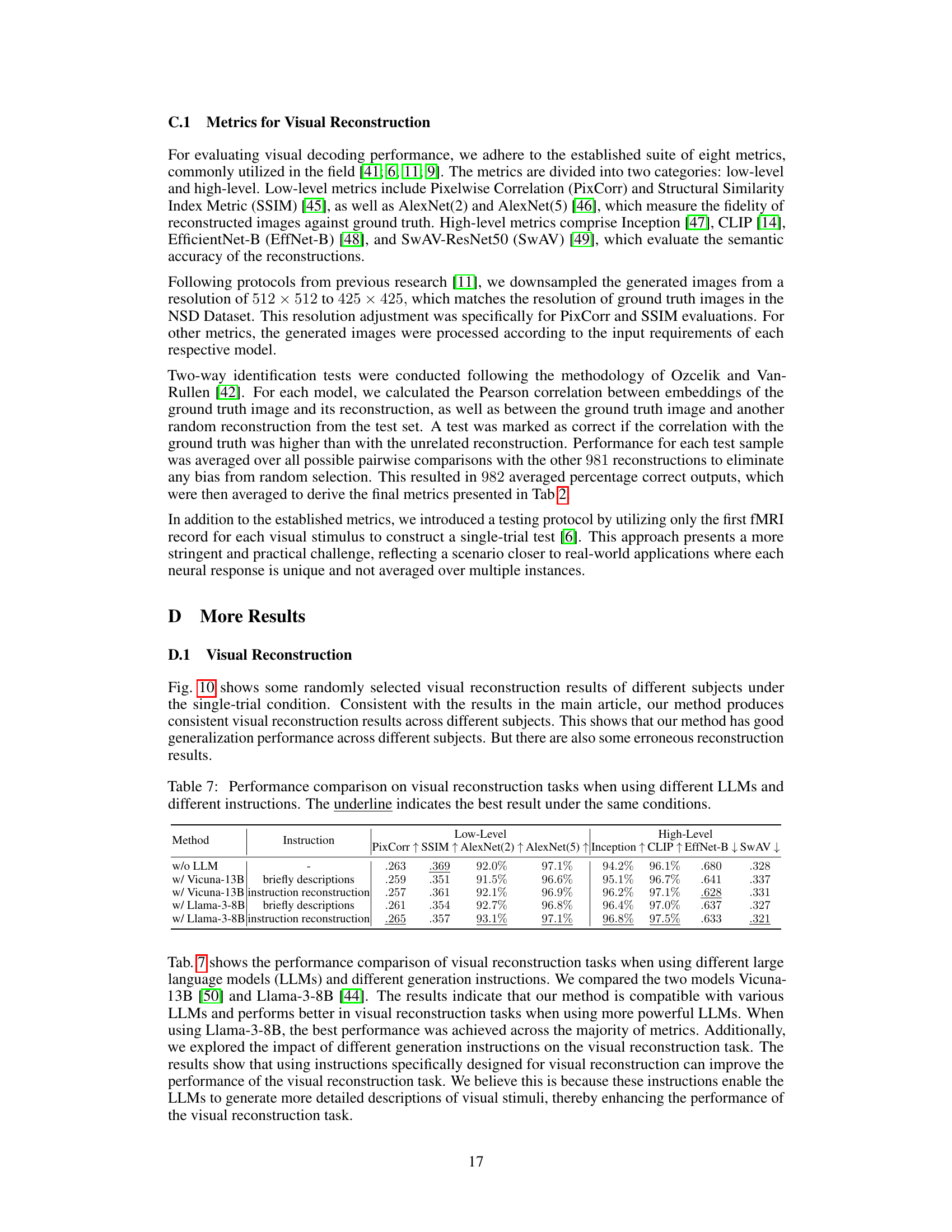

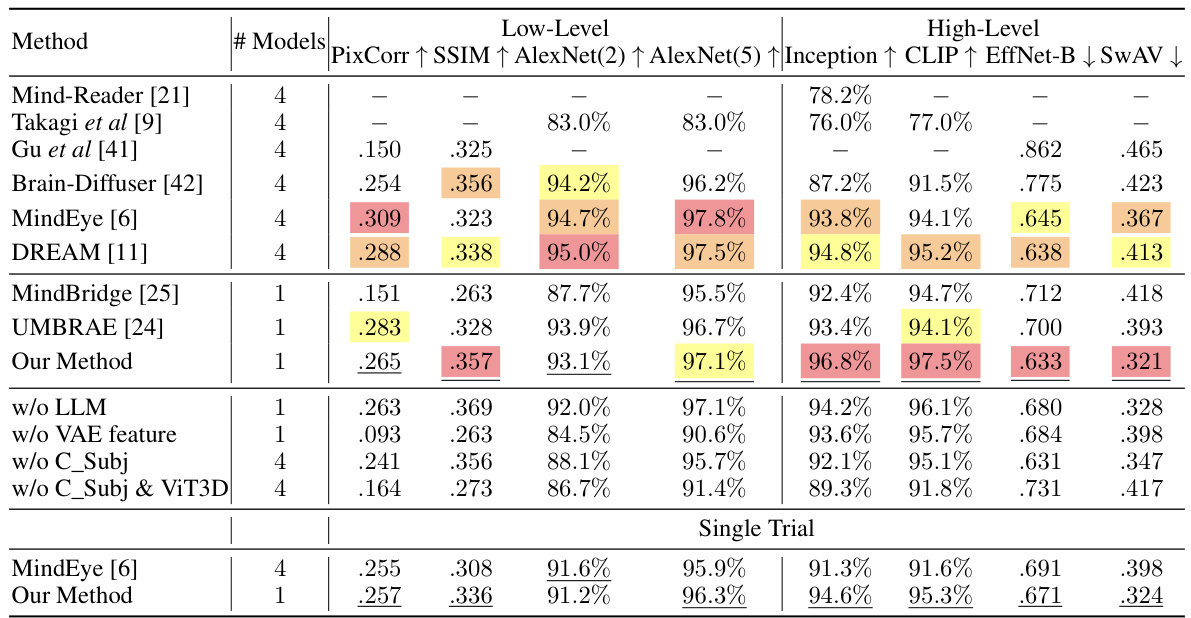

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed visual reconstruction method against several other state-of-the-art methods. It evaluates performance across various low-level (Pixelwise Correlation, SSIM, AlexNet features) and high-level (Inception, CLIP, EfficientNet-B, SwAV) metrics. Results are shown for both multi-trial and single-trial conditions, highlighting the method’s ability to generalize and achieve high performance even with limited data.

This table presents a quantitative analysis of visual reconstruction performance using different large language models (LLMs) and instruction types. It compares the performance of a model without LLMs against models using Vicuna-13B and Llama-3-8B, with both ‘brief descriptions’ and ‘instruction reconstruction’ instructions. The metrics used assess both low-level (pixel-level fidelity) and high-level (semantic accuracy) aspects of the image reconstruction, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of the models’ effectiveness.

Full paper#