TL;DR#

Minimax optimization problems, frequently encountered in machine learning (e.g., GANs), are often addressed using extragradient (EG) methods. However, stochastic EG (SEG) methods have limited success, especially in unconstrained settings. Existing SEG variants often require restrictive assumptions or lack convergence rate guarantees. This creates a need for more robust and efficient stochastic minimax optimization techniques.

This paper introduces SEG-FFA, a novel SEG algorithm combining flip-flop shuffling and anchoring. The authors prove that SEG-FFA has provably faster convergence than existing methods, demonstrating success in unconstrained convex-concave problems and providing tight convergence rate bounds in strongly convex-strongly concave settings. This breakthrough addresses a significant gap in the field by providing a theoretically sound and practically efficient method for unconstrained stochastic minimax optimization.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in minimax optimization, particularly those working with stochastic methods. It directly addresses the limitations of existing stochastic extragradient methods by providing provably faster convergence in both convex-concave and strongly convex-strongly concave settings. This opens avenues for improved algorithms in various machine learning applications involving minimax problems.

Visual Insights#

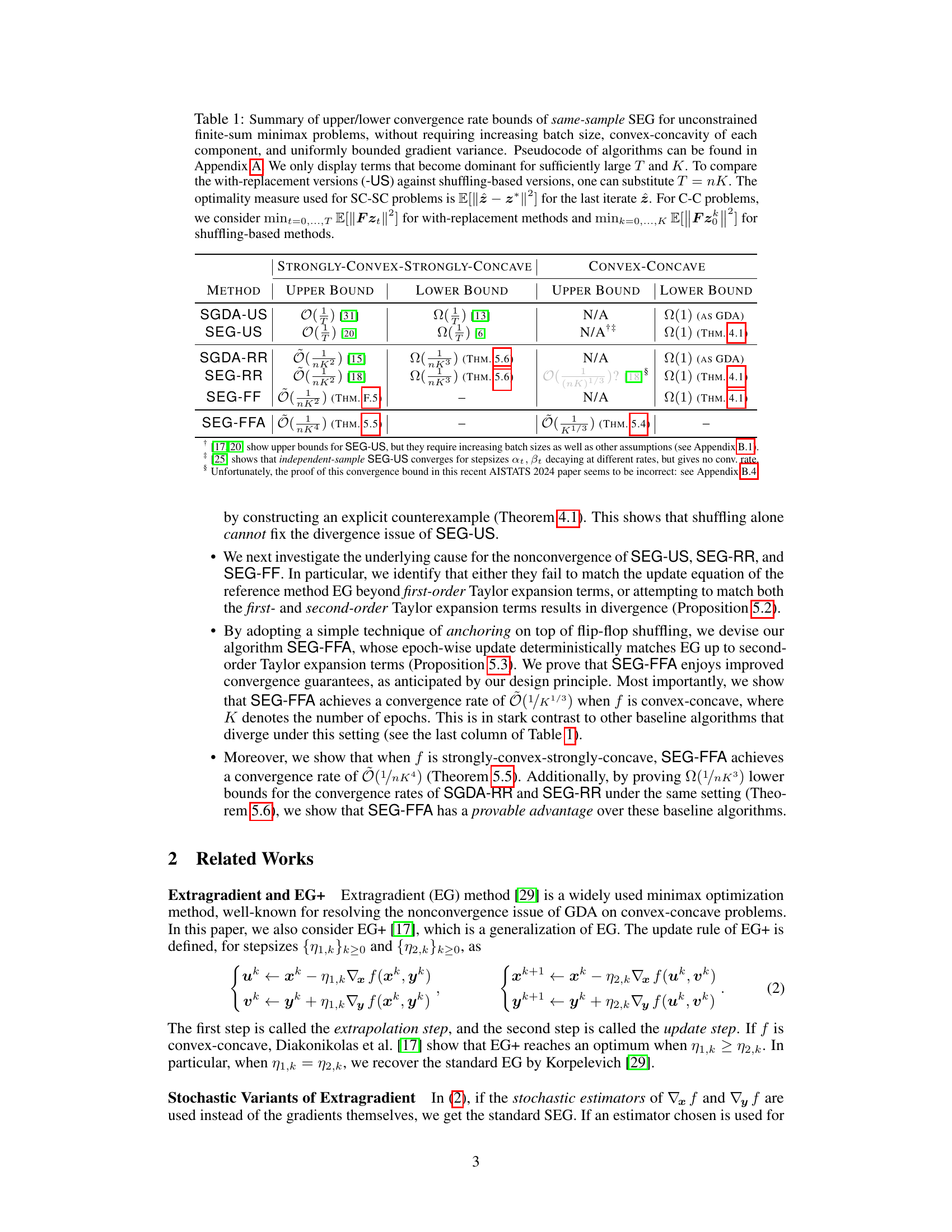

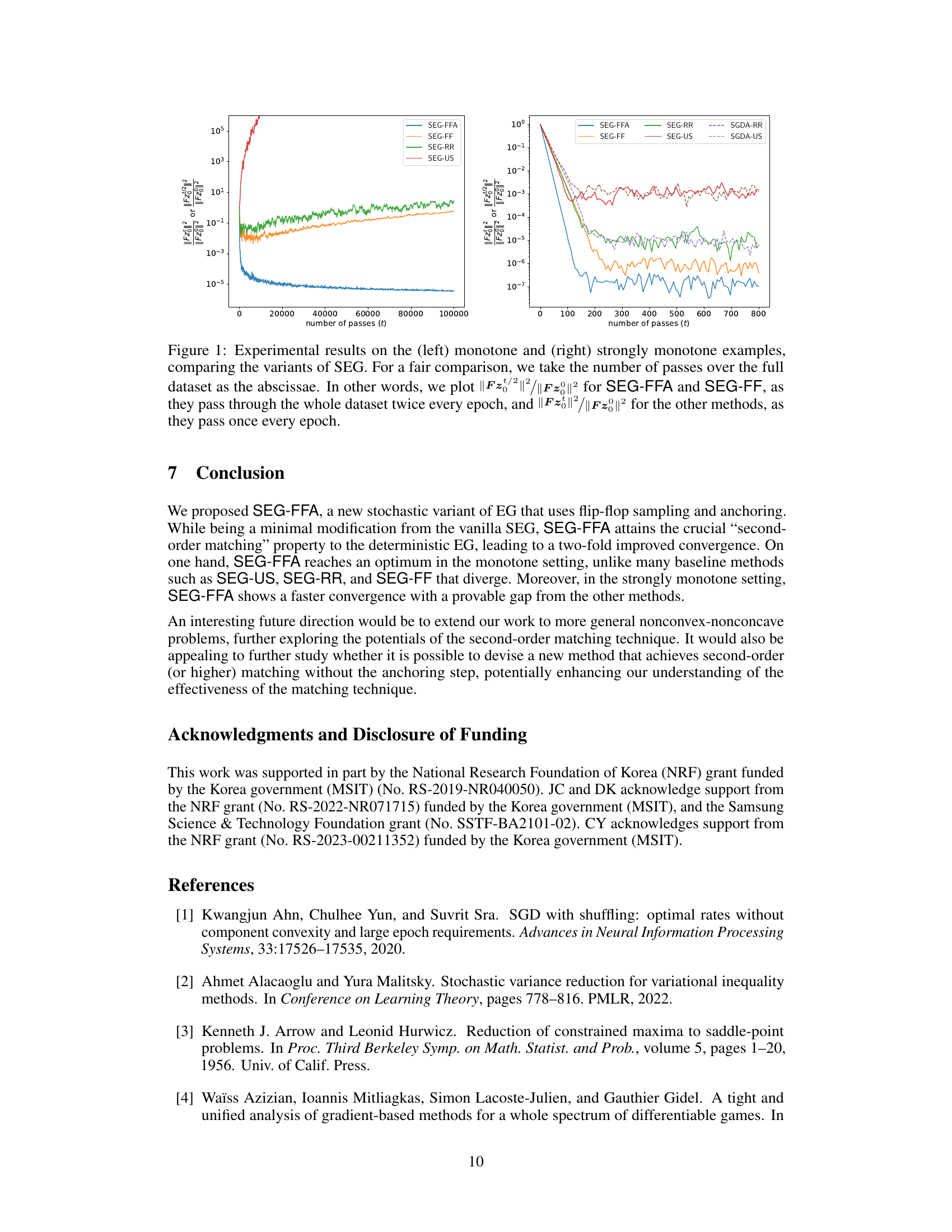

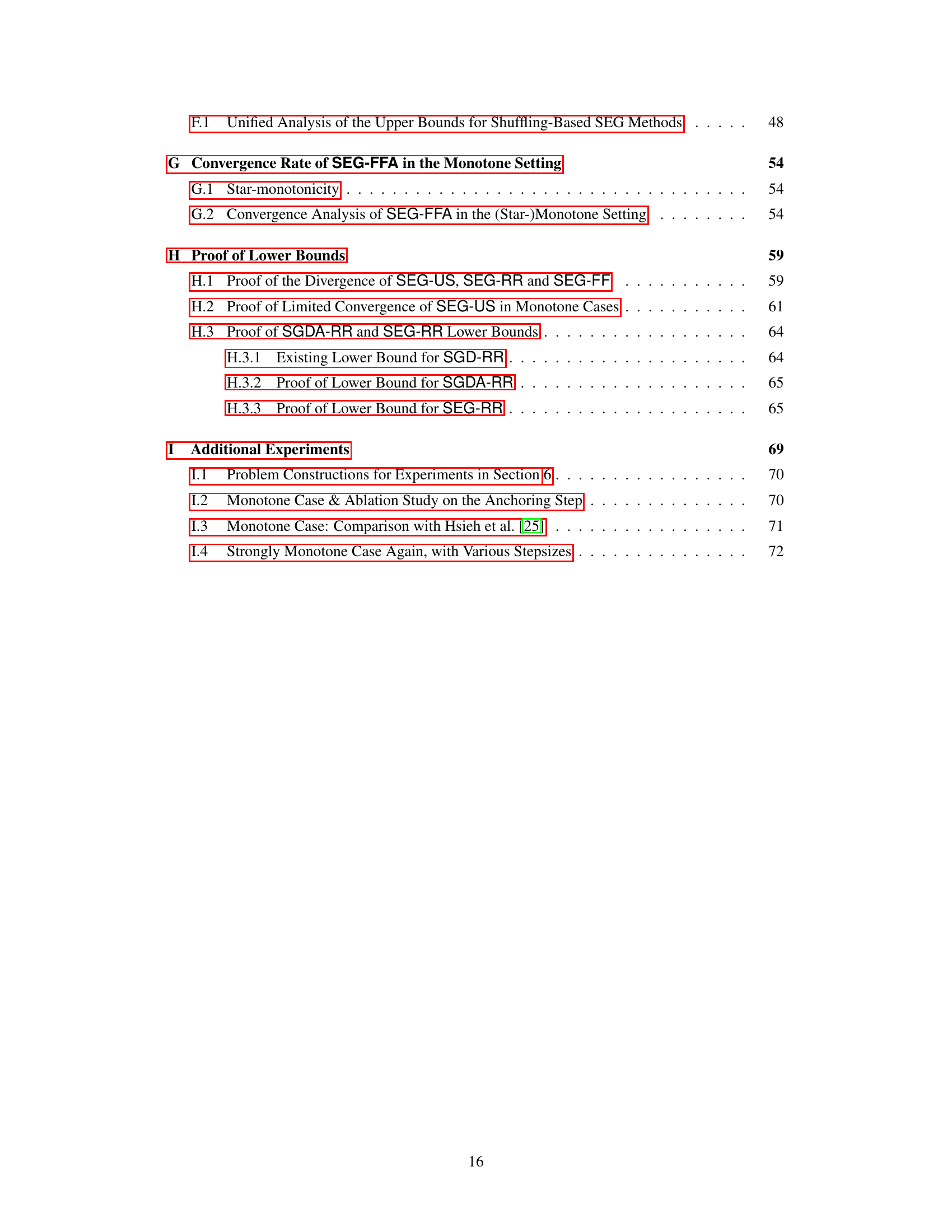

🔼 This figure shows the experimental results for both monotone and strongly monotone cases. The x-axis represents the number of passes over the dataset. The y-axis represents the squared norm of the saddle-point gradient, normalized by the squared norm of the initial saddle-point gradient. The plots compare the performance of different stochastic extragradient (SEG) methods: SEG-FFA, SEG-FF, SEG-RR, SEG-US, SGDA-RR, and SGDA-US. In the monotone case (left), SEG-FFA is the only method that converges, while the others diverge. In the strongly monotone case (right), SEG-FFA shows faster convergence compared to the other methods. The different convergence rates highlight the benefits of SEG-FFA.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experimental results on the (left) monotone and (right) strongly monotone examples, comparing the variants of SEG. For a fair comparison, we take the number of passes over the full dataset as the abscissae. In other words, we plot ||Fz/2||2/||Fz8||² for SEG-FFA and SEG-FF, as they pass through the whole dataset twice every epoch, and ||Fz||²/||Fz8||² for the other methods, as they pass once every epoch.

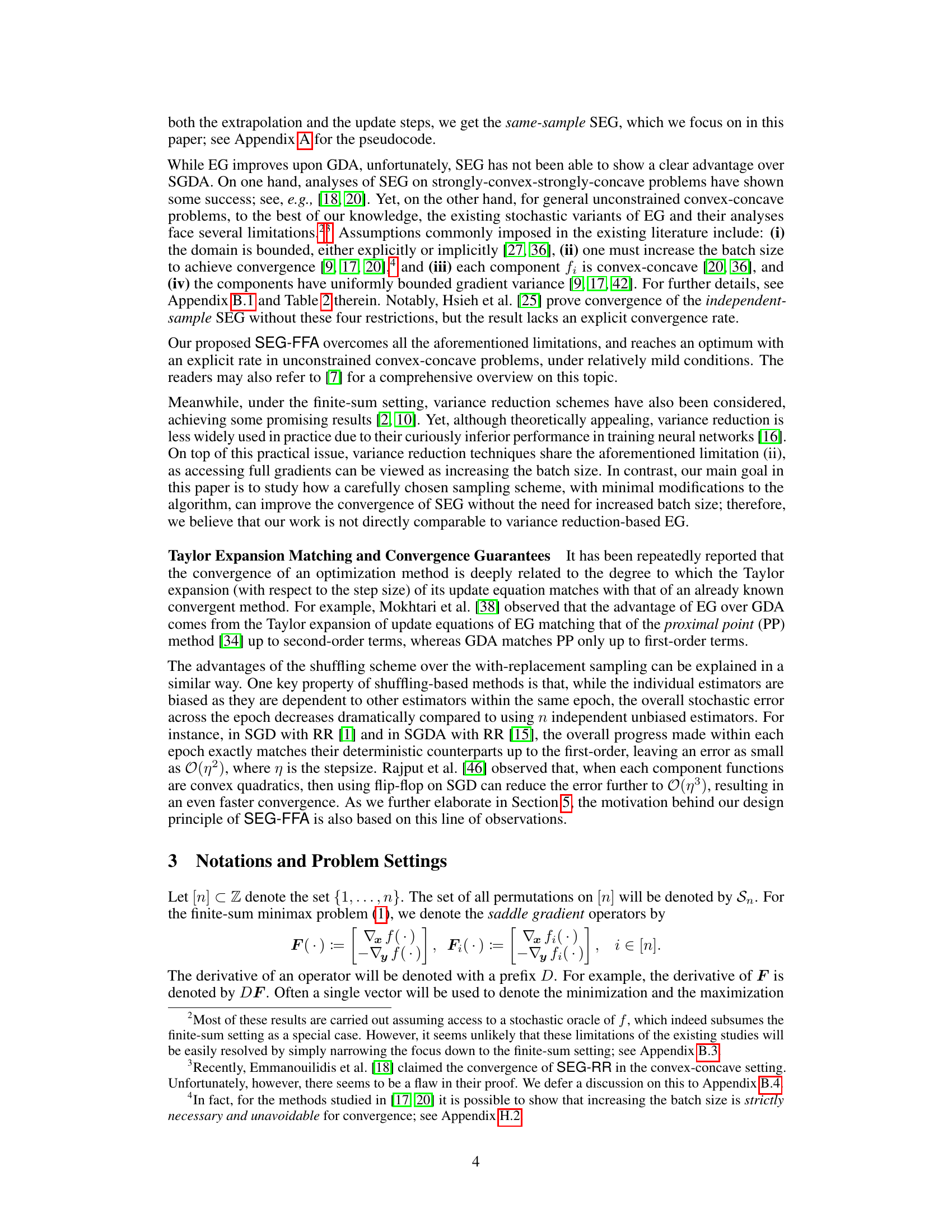

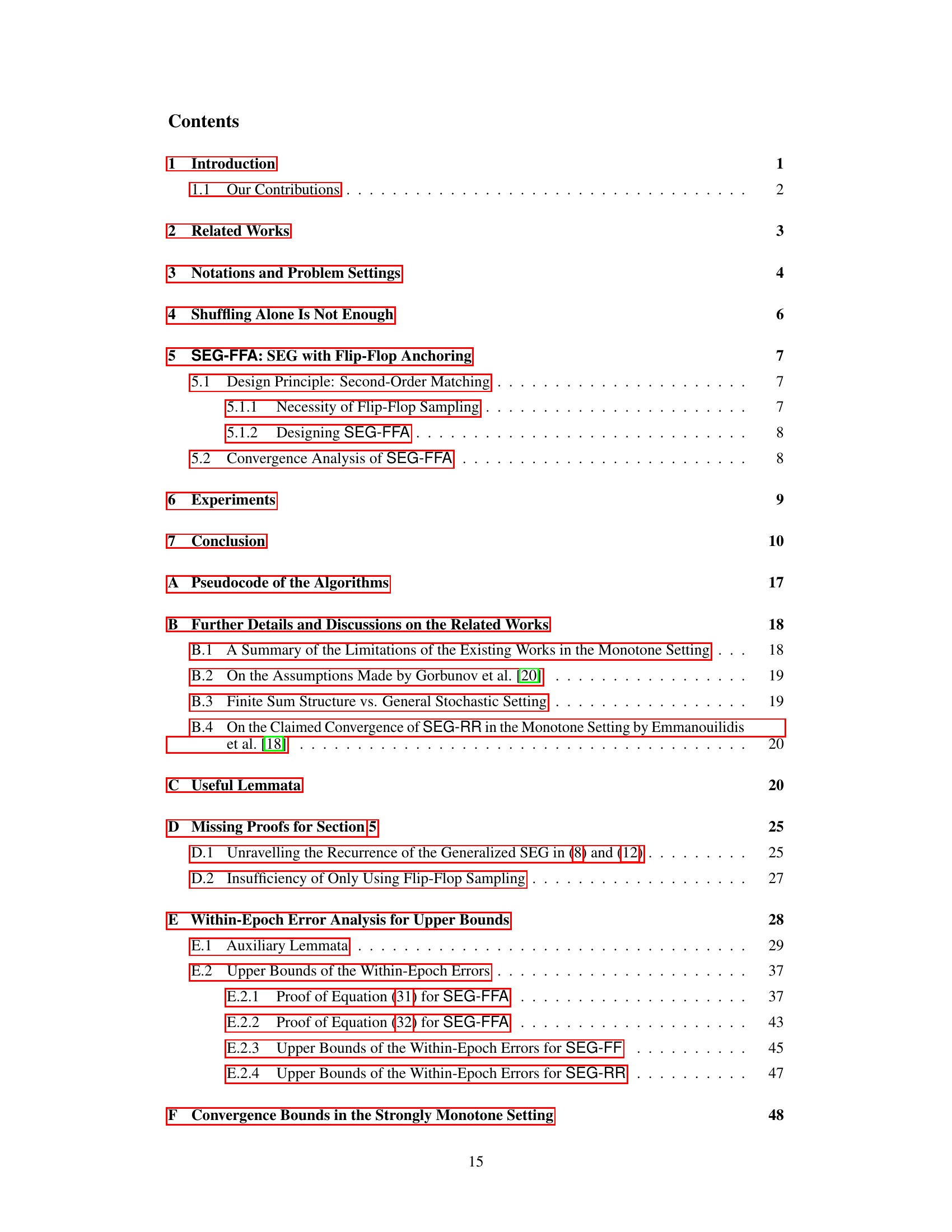

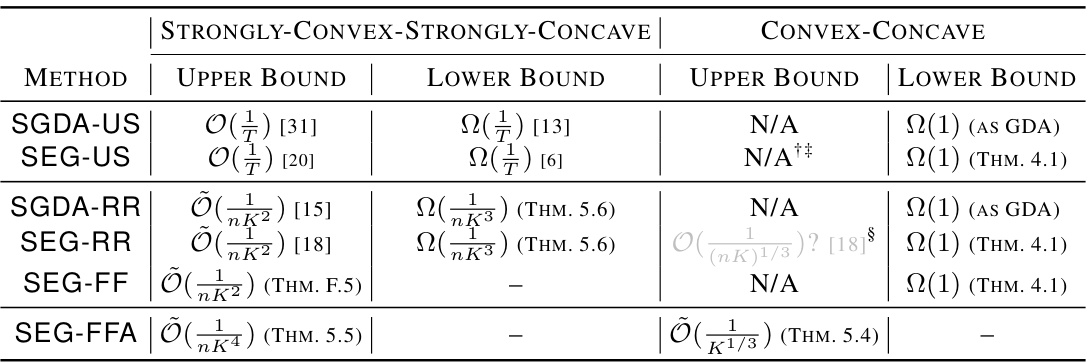

🔼 This table summarizes the upper and lower bounds of convergence rates for various stochastic extragradient (SEG) methods applied to unconstrained finite-sum minimax problems. It compares the rates for methods using different shuffling schemes (random reshuffling, flip-flop) against the standard with-replacement sampling. The table distinguishes between strongly convex-strongly concave and convex-concave settings, and specifies the optimality measures used for comparison.

read the caption

Table 1: Summary of upper/lower convergence rate bounds of same-sample SEG for unconstrained finite-sum minimax problems, without requiring increasing batch size, convex-concavity of each component, and uniformly bounded gradient variance. Pseudocode of algorithms can be found in Appendix A. We only display terms that become dominant for sufficiently large T and K. To compare the with-replacement versions (-US) against shuffling-based versions, one can substitute T = nK. The optimality measure used for SC-SC problems is E[||2 – z* ||2] for the last iterate 2. For C-C problems, we consider mint=0,...,T E[||Fzt||2] for with-replacement methods and mink=0,...,K E[||FZ||2] for shuffling-based methods.

In-depth insights#

SEG Divergence#

The SEG (Stochastic Extragradient) algorithm, while theoretically appealing for minimax optimization, suffers from a crucial weakness: divergence. The paper investigates this issue, demonstrating that various shuffling strategies, such as random reshuffling and flip-flop, are insufficient to guarantee SEG’s convergence in the general convex-concave setting. This divergence is not merely a theoretical curiosity; it represents a significant obstacle to practical application. The core issue appears to lie in an incomplete match between the SEG updates and those of its deterministic counterpart, the Extragradient method, when higher-order terms in Taylor expansion are considered. The analysis highlights that anchoring provides a solution, effectively mitigating the stochastic noise and ensuring convergence. This finding emphasizes that carefully designed algorithmic modifications, beyond simply altering sampling strategies, are crucial for the successful application of stochastic minimax methods.

Flip-Flop Anchor#

The concept of “Flip-Flop Anchoring” in the context of stochastic extragradient methods for minimax optimization is a novel technique that enhances convergence. It cleverly combines two strategies: flip-flop shuffling, which involves processing data in a forward and then reversed order within each epoch, and anchoring, which takes a convex combination of the initial and final iterates of the epoch. This dual approach is crucial because, alone, flip-flop shuffling can still lead to divergence in certain convex-concave settings, while anchoring provides stability by mitigating the effects of stochastic noise accumulated during the shuffling passes. The combination of these two techniques results in an algorithm (SEG-FFA) that provably converges faster than other shuffling based methods, by achieving second-order Taylor expansion matching with the deterministic extragradient method. Provable convergence guarantees are a significant advantage over existing stochastic extragradient methods, which often require additional assumptions or fail to achieve comparable rates. The anchoring step is a simple but effective trick that dramatically improves the practical performance of the algorithm, showcasing the power of combining seemingly disparate techniques to address challenges in stochastic optimization.

Taylor Expansion#

The concept of Taylor expansion matching is crucial in understanding the paper’s core contribution. It reveals a design principle for creating efficient stochastic extragradient methods. The authors cleverly leverage Taylor expansions to show how closely their proposed SEG-FFA algorithm approximates the deterministic EG method. The matching of higher-order Taylor expansion terms (second-order) is key to achieving improved convergence, unlike other shuffling-based methods which fail to match beyond first-order terms. This precise approximation mitigates the negative impact of stochastic noise inherent in the algorithm, leading to provable convergence guarantees in convex-concave settings and faster convergence rates in strongly-convex-strongly-concave settings. The analysis demonstrates a direct connection between Taylor expansion accuracy and algorithmic performance, providing a rigorous theoretical foundation for SEG-FFA’s superior convergence properties. The detailed analysis of Taylor expansion matching is a significant strength of the paper, showcasing a novel and powerful design strategy.

Convergence Rates#

The convergence rate analysis is a crucial aspect of the research paper, focusing on how quickly the proposed stochastic extragradient algorithm (SEG-FFA) approaches the optimal solution. The paper establishes provably faster convergence rates for SEG-FFA compared to other shuffling-based methods in both strongly convex-strongly concave and convex-concave settings. Theoretical upper and lower bounds on the convergence rates are derived, providing a comprehensive understanding of the algorithm’s efficiency. The analysis shows that SEG-FFA’s superior convergence stems from its ability to accurately match the update equation of the deterministic extragradient method, minimizing stochastic noise through flip-flop shuffling and anchoring. The results highlight the importance of second-order matching and the impact of different shuffling schemes on convergence behavior. The study makes significant contributions to the theoretical understanding of stochastic minimax optimization by providing rigorous convergence guarantees in the unconstrained finite-sum setting.

Future Research#

The paper’s ‘Future Research’ section could explore extending the second-order matching technique to nonconvex-nonconcave settings. This would involve investigating whether the design principles behind SEG-FFA’s success can be generalized to broader classes of minimax problems. Another crucial area of investigation is relaxing the strong assumptions (like Lipschitz-continuous Hessian and component variance bounds) currently required to prove convergence guarantees. Exploring alternative sampling schemes, beyond flip-flop shuffling, that can enhance SEG’s convergence rate without increasing batch size would be valuable. Finally, empirical validation is essential. The current experiments are limited in scope, so more robust and extensive testing on diverse datasets and network architectures is needed to confirm the practical advantages of SEG-FFA, especially compared to other state-of-the-art stochastic minimax algorithms.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure shows the experimental results for both monotone and strongly monotone cases. It compares the performance of SEG-FFA, SEG-FF, SEG-RR, SEG-US, SGDA-RR, and SGDA-US in terms of the squared norm of the saddle gradient. For SEG-FFA and SEG-FF, since two passes over the data occur per epoch, the x-axis represents the number of full dataset passes divided by two. For the other methods, the x-axis is the number of full dataset passes.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experimental results on the (left) monotone and (right) strongly monotone examples, comparing the variants of SEG. For a fair comparison, we take the number of passes over the full dataset as the abscissae. In other words, we plot ||Fz/2||2/||Fz8||2 for SEG-FFA and SEG-FF, as they pass through the whole dataset twice every epoch, and ||Fzt||2/||Fz8||2 for the other methods, as they pass once every epoch.

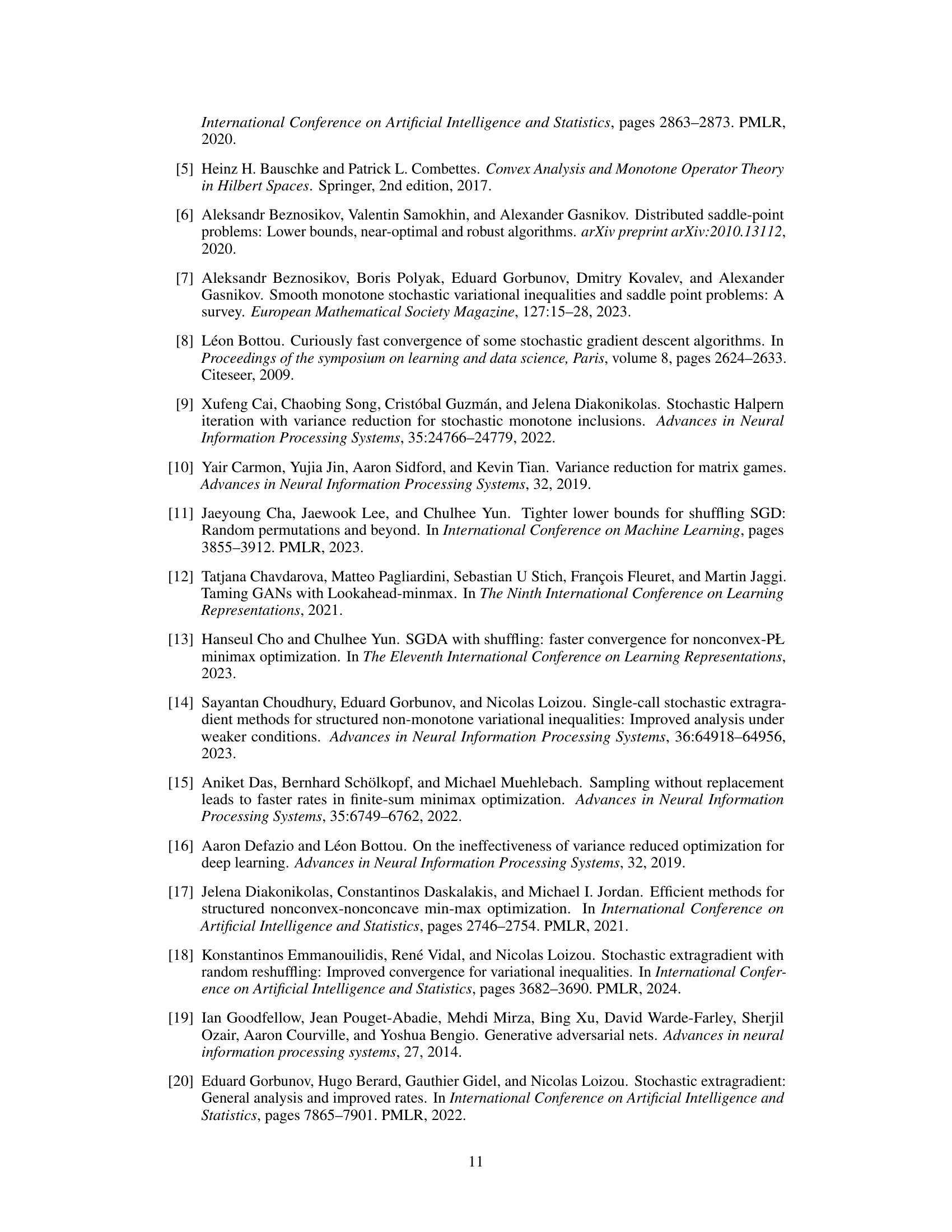

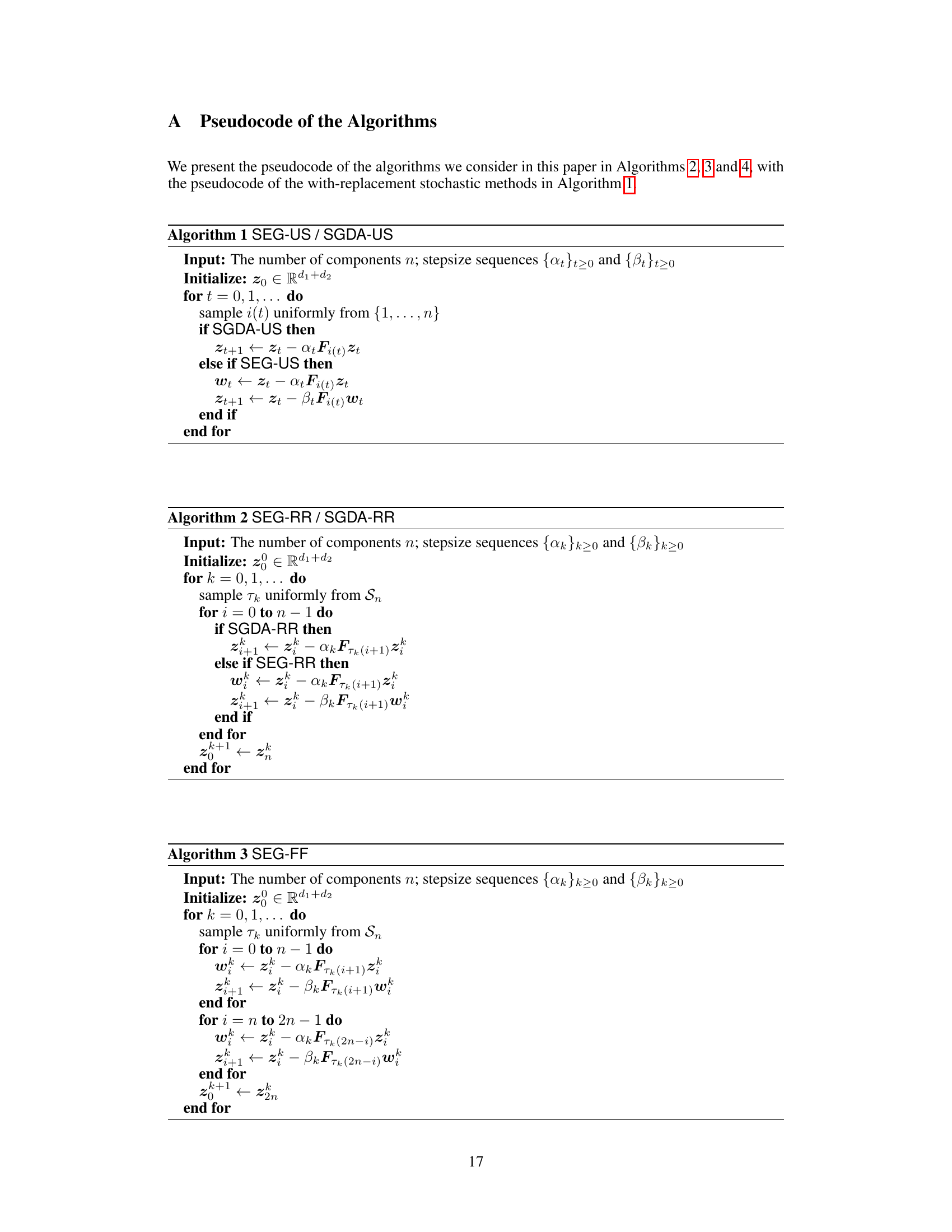

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed SEG-FFA algorithm against two variants of the independent-sample double stepsize stochastic extragradient (DSEG) algorithm from Hsieh et al. [25] on a monotone example. The x-axis represents the number of passes over the dataset, and the y-axis shows ||Fz||²/||Fz₀||², which is a measure of the convergence to the solution (optimum). SEG-FFA demonstrates significantly faster convergence compared to both DSEG variants.

read the caption

Figure 3: Experimental results in the monotone example, comparing SEG-FFA and the methods proposed by Hsieh et al. [25]. By the same reason as in Figure 2, we plot ||Fz2||²/||Fz8||² for SEG-FFA only.

🔼 The figure shows the experimental results for both monotone and strongly monotone cases. It compares the performance of SEG-FFA against other SEG variants (SEG-US, SEG-RR, SEG-FF) and SGDA variants (SGDA-US, SGDA-RR). The x-axis represents the number of passes over the full dataset, and the y-axis shows the normalized function value (||Fz||²). For SEG-FFA and SEG-FF (which use two passes per epoch), the y-axis shows the average of the function values for the two passes. The figure demonstrates that SEG-FFA converges while others diverge in the monotone case and shows faster convergence in the strongly monotone case.

read the caption

Figure 1: Experimental results on the (left) monotone and (right) strongly monotone examples, comparing the variants of SEG. For a fair comparison, we take the number of passes over the full dataset as the abscissae. In other words, we plot ||Fz/2||2/||Fz8||² for SEG-FFA and SEG-FF, as they pass through the whole dataset twice every epoch, and || Fz ||²/||Fz8||² for the other methods, as they pass once every epoch.

Full paper#