TL;DR#

Probabilistic inference for integer arithmetic is computationally expensive and has hindered the progress of neurosymbolic AI. Existing methods using exact enumeration or approximations struggle to scale beyond toy problems. The discrete nature of integers also poses challenges for gradient-based learning in neurosymbolic models.

The authors address these challenges by formulating linear arithmetic over integer-valued random variables as tensor manipulations. This allows them to exploit the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) for efficient computation of probability distributions, achieving O(N log N) complexity instead of the traditional O(N²) complexity. Their approach, PLIA₁, also provides a differentiable data structure enabling gradient-based learning. They validate the approach experimentally, demonstrating significant speedups (several orders of magnitude) compared to current state-of-the-art methods on various problems including exact inference tasks and challenging neurosymbolic AI problems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in probabilistic programming and neurosymbolic AI. It presents a groundbreaking solution to the computational bottleneck of probabilistic inference over integer arithmetic, enabling efficient and scalable solutions for complex real-world problems. This opens new avenues for applying neurosymbolic methods to larger-scale problems and may lead to significant advances in fields like AI planning, combinatorial optimization, and reasoning under uncertainty.

Visual Insights#

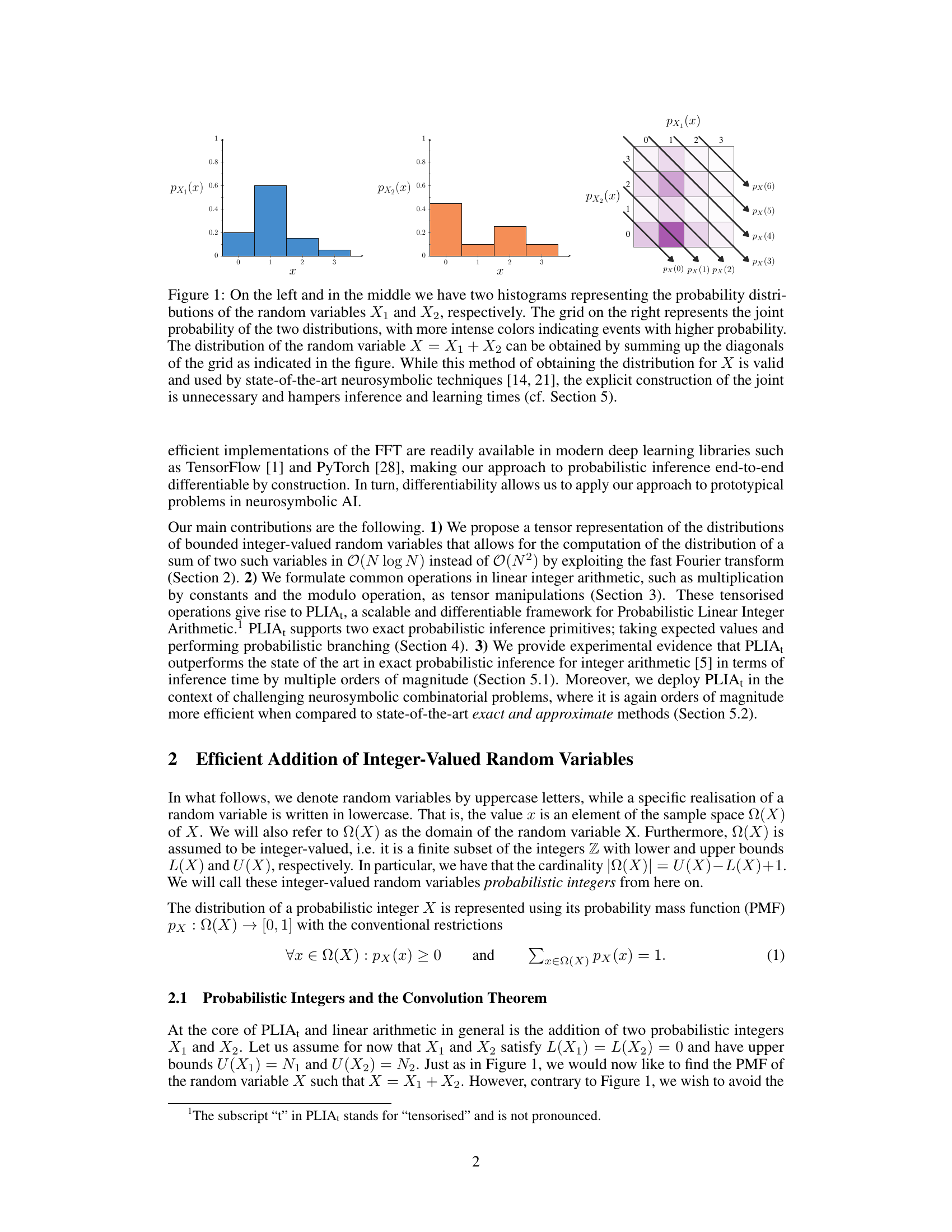

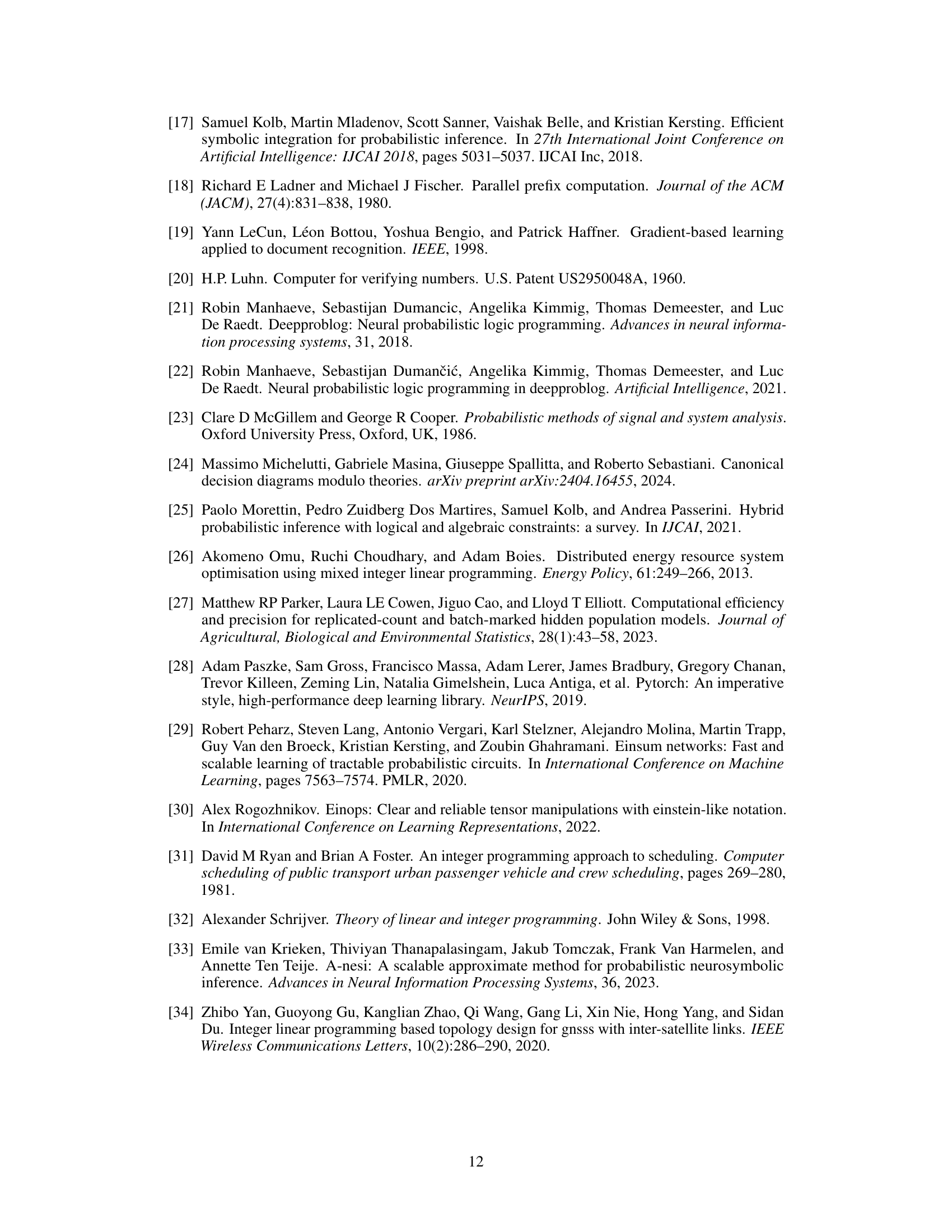

🔼 This figure illustrates three different ways of visualizing the sum of two independent discrete random variables (X₁ and X₂). The left and center histograms show the probability distributions of X₁ and X₂ respectively. The right panel shows the joint probability distribution of X₁ and X₂, represented as a grid where color intensity represents the probability of each combination of values. The figure highlights that the probability distribution of the sum X = X₁ + X₂ can be obtained by summing along the diagonals of the joint distribution grid. While this direct method is valid, it is computationally expensive for larger distributions and forms the basis for the efficiency improvements in the proposed PLIA approach that avoids this explicit construction.

read the caption

Figure 1: On the left and in the middle we have two histograms representing the probability distributions of the random variables X₁ and X₂, respectively. The grid on the right represents the joint probability of the two distributions, with more intense colors indicating events with higher probability. The distribution of the random variable X = X₁ + X₂ can be obtained by summing up the diagonals of the grid as indicated in the figure. While this method of obtaining the distribution for X is valid and used by state-of-the-art neurosymbolic techniques [14, 21], the explicit construction of the joint is unnecessary and hampers inference and learning times (cf. Section 5).

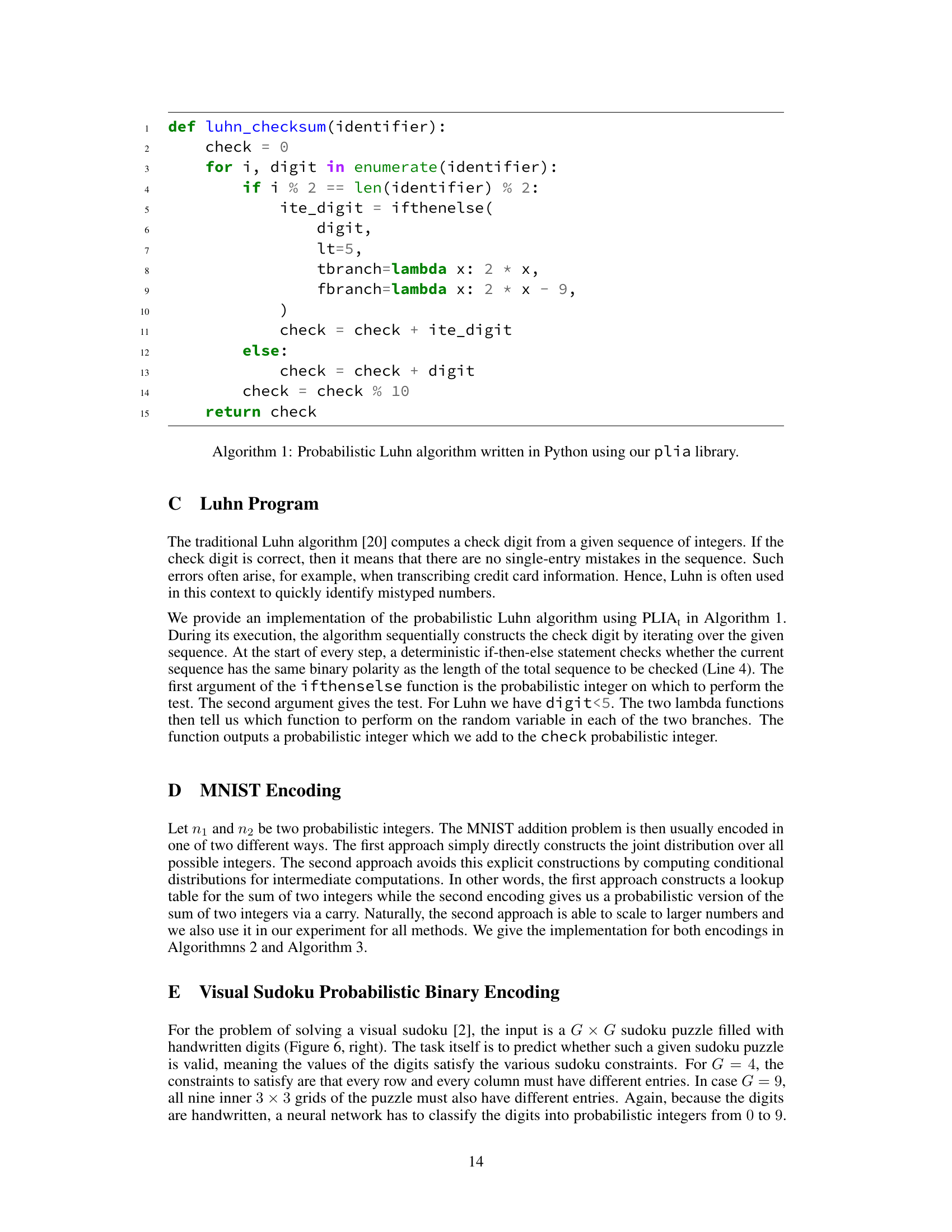

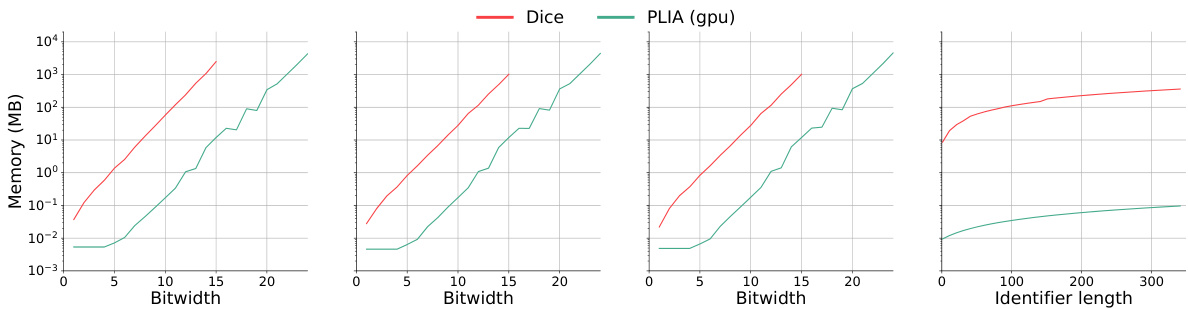

🔼 This table compares the performance of PLIA₁ against other neurosymbolic methods on two benchmark tasks: MNIST addition and visual Sudoku. It shows median test accuracies and training times for various problem sizes. Accuracy is reported with 25th and 75th percentiles, and training times are given in minutes, also with 25th and 75th percentiles, with a 24-hour time limit.

read the caption

Table 1: In the upper part part we report median test accuracies over 10 runs for the MNIST addition and the visual sudoku benchmarks for varying problem sizes and different neurosymbolic frameworks. Sub- and superscript indicate the 25 and 75 percent quantiles, respectively. In the lower part we report the training times in minutes, again using medians with 25 and 75 percent quantiles. We set the time-out to 24 hours (1440 minutes).

In-depth insights#

Tensorial PLIA#

Tensorial PLIA, a hypothetical extension of Probabilistic Linear Integer Arithmetic (PLIA), represents a significant advancement in probabilistic inference for integer arithmetic. By leveraging tensor representations of probability distributions, Tensorial PLIA offers a differentiable data structure, allowing for the application of gradient-based learning methods and efficient computation using modern deep learning libraries. The core innovation is the adaptation of the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to probability operations in the log-domain, enabling the computation of convolutions (representing sums of random variables) with significantly improved time complexity. This addresses a major limitation of traditional approaches, which scale quadratically with the size of the input. The result is a system that scales to significantly larger problem sizes than previously possible, pushing the boundaries of neurosymbolic AI applications. However, further research into the stability and robustness of Tensorial PLIA, particularly in higher-dimensional spaces, is warranted. The method’s efficiency relies on the FFT’s effectiveness, meaning limitations in the applicability of the FFT could limit the scalability of this approach.

FFT-based Inference#

The heading ‘FFT-based Inference’ suggests a method for probabilistic inference leveraging the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). This approach likely exploits the convolution theorem, which states that the convolution of two functions in the time domain is equivalent to the pointwise product of their Fourier transforms in the frequency domain. In the context of probability distributions, this means the probability distribution of the sum of two independent random variables is the convolution of their individual distributions. Applying the FFT allows for efficient computation of this convolution, significantly faster than traditional methods, especially for high-dimensional problems. The log-domain trick is likely employed to handle numerical stability issues related to very small probabilities. The key advantage is scaling probabilistic inference to larger problem sizes, which are intractable using naive methods or exact enumeration. The implementation using deep learning libraries suggests that the methodology is readily differentiable, thus facilitating integration into machine learning workflows for tasks that benefit from probabilistic modeling.

Neurosymbolic AI#

Neurosymbolic AI seeks to bridge the gap between the flexibility of neural networks and the logical reasoning capabilities of symbolic AI. The core challenge lies in effectively integrating these two paradigms, allowing systems to learn from data while also leveraging explicit knowledge representations and reasoning mechanisms. This integration promises significant advancements in several AI areas, enabling more robust, explainable, and generalizable models. However, achieving a seamless integration is complex, requiring novel methods for knowledge representation, inference, and learning that can handle both continuous and discrete data. The paper explores one aspect of this challenge, focusing on probabilistic inference for integer arithmetic—a fundamental building block for many neurosymbolic applications. By applying the fast Fourier transform, the authors present a novel approach that significantly improves efficiency. This illustrates the potential of exploring mathematical and computational techniques to address the core limitations of neurosymbolic AI, paving the way for more sophisticated and powerful systems in the future.

#P-hard Inference#

The heading ‘#P-hard Inference’ highlights a critical challenge in probabilistic inference, specifically within the context of integer arithmetic. The #P-completeness classification implies that finding the exact probability distribution for even simple arithmetic expressions involving integer-valued random variables is computationally intractable. This is a significant hurdle for scaling neurosymbolic AI methods beyond toy problems. Traditional approaches relying on exact enumeration or sampling become infeasible as the problem size grows. The difficulty stems from the discrete nature of integers, unlike continuous variables where methods like variational inference can offer approximations. The paper addresses this by proposing a novel technique that leverages the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) and tensor operations to bypass the need for direct convolution, a core component of computing probability distributions over sums of random variables. This enables a significant speedup, allowing for efficient probabilistic inference in larger-scale applications. The approach effectively trades exact solutions for an efficient, scalable, and differentiable method, opening up possibilities for learning and gradient-based optimization, typically infeasible with #P-hard problems.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending probabilistic linear integer arithmetic (PLIA) to handle more complex operations beyond the basic arithmetic supported in the current version. Integrating more sophisticated probabilistic inference techniques such as variational inference or Markov chain Monte Carlo methods could improve scalability and accuracy. Developing a fully-fledged neuro-probabilistic programming language based on PLIA would make it more accessible to a wider audience and facilitate the development of more complex neurosymbolic AI systems. Furthermore, exploring applications of PLIA in different problem domains, including areas beyond combinatorial optimization and neurosymbolic AI, would also be fruitful. Investigating the potential for hardware acceleration of the FFT computations within PLIA could significantly improve performance and enable the scaling of this technique to even larger problem instances. Finally, a thorough investigation into the theoretical limits of the approach, focusing on the potential for approximation and how such approximations affect the accuracy and reliability of the resulting inferences, would be valuable.

More visual insights#

More on figures

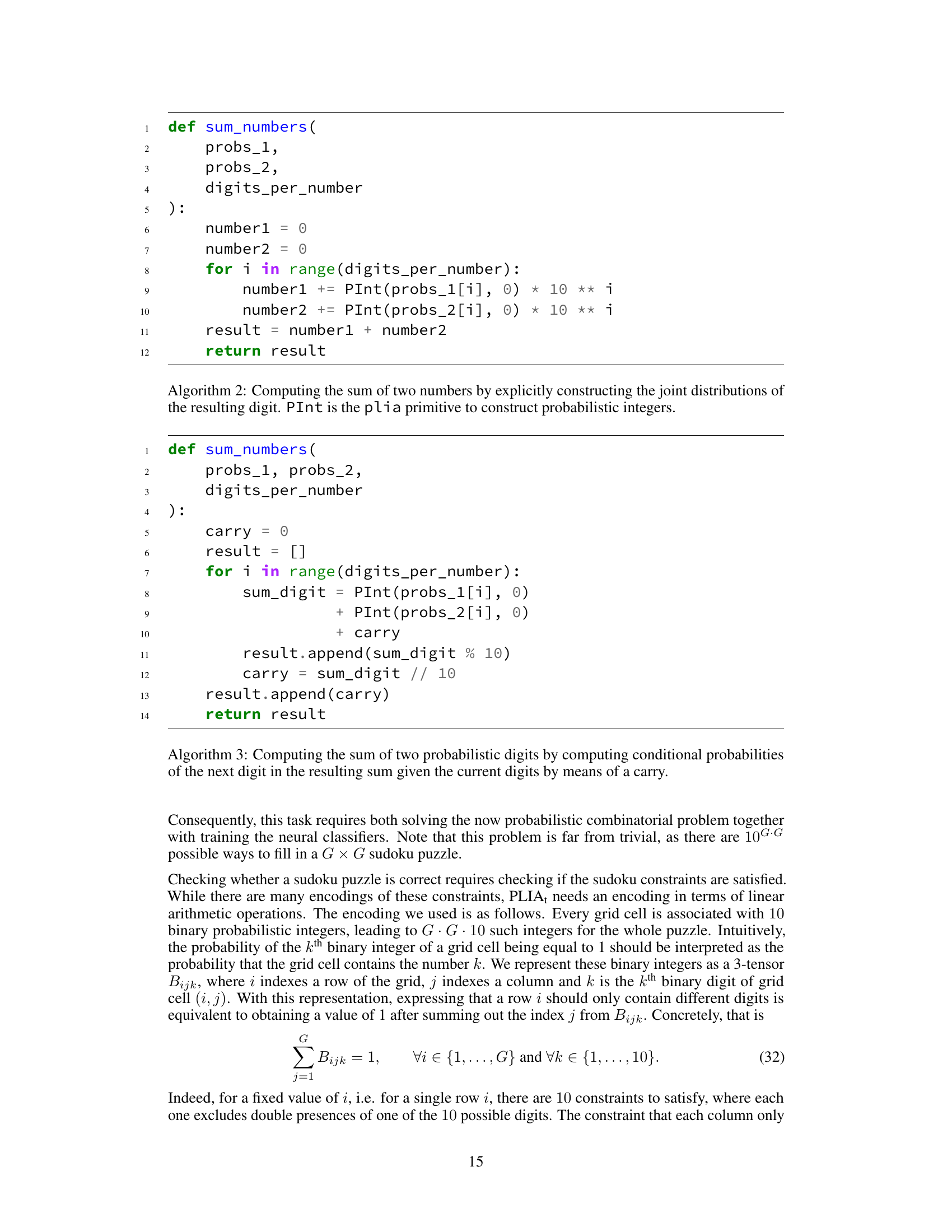

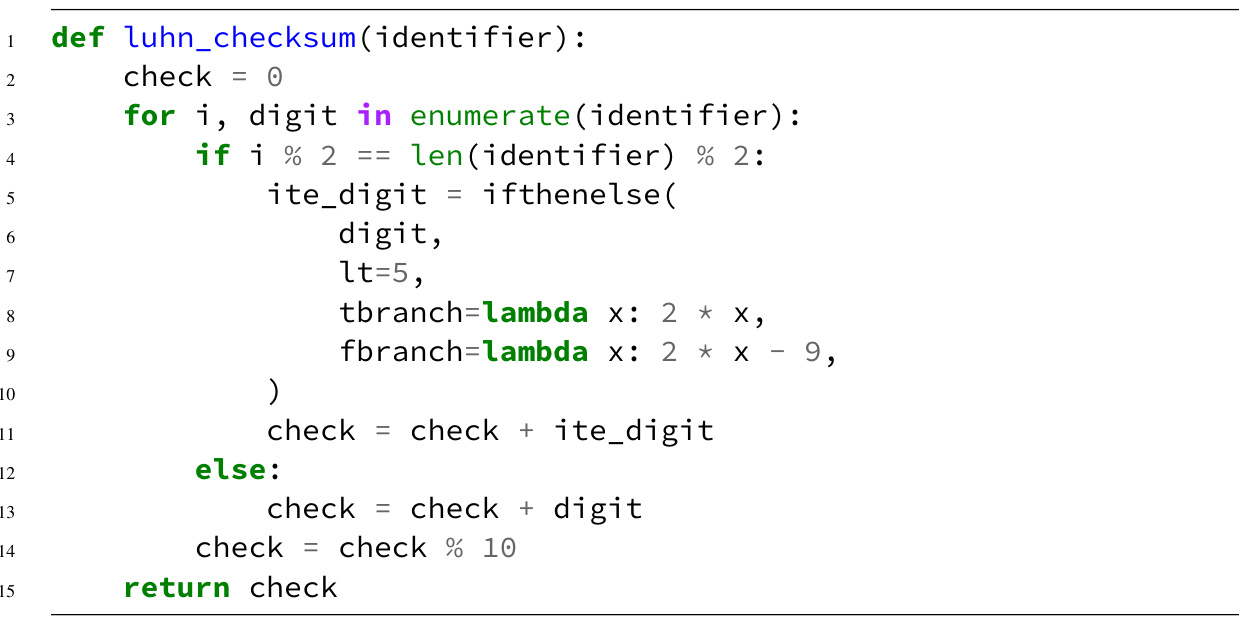

🔼 This figure demonstrates three operations on probabilistic integers: addition of a constant, negation, and multiplication by a constant. The left panel shows that adding a constant shifts the histogram to the right. The middle panel shows that negation reverses the order of the histogram’s bins, while the right panel shows that multiplication by a constant (3 in this example) stretches the histogram by inserting empty bins.

read the caption

Figure 2: (Left) Adding a constant to a probabilistic integer simply means that we have to shift the corresponding histogram, shown here for X' = X + 1. (Middle) For the negation X′ = −X, the bins of the histogram reverse their order and the negation of the upper bound becomes the new lower bound. (Right) For multiplication, here show the case X' = 3X by inserting zero probability bins.

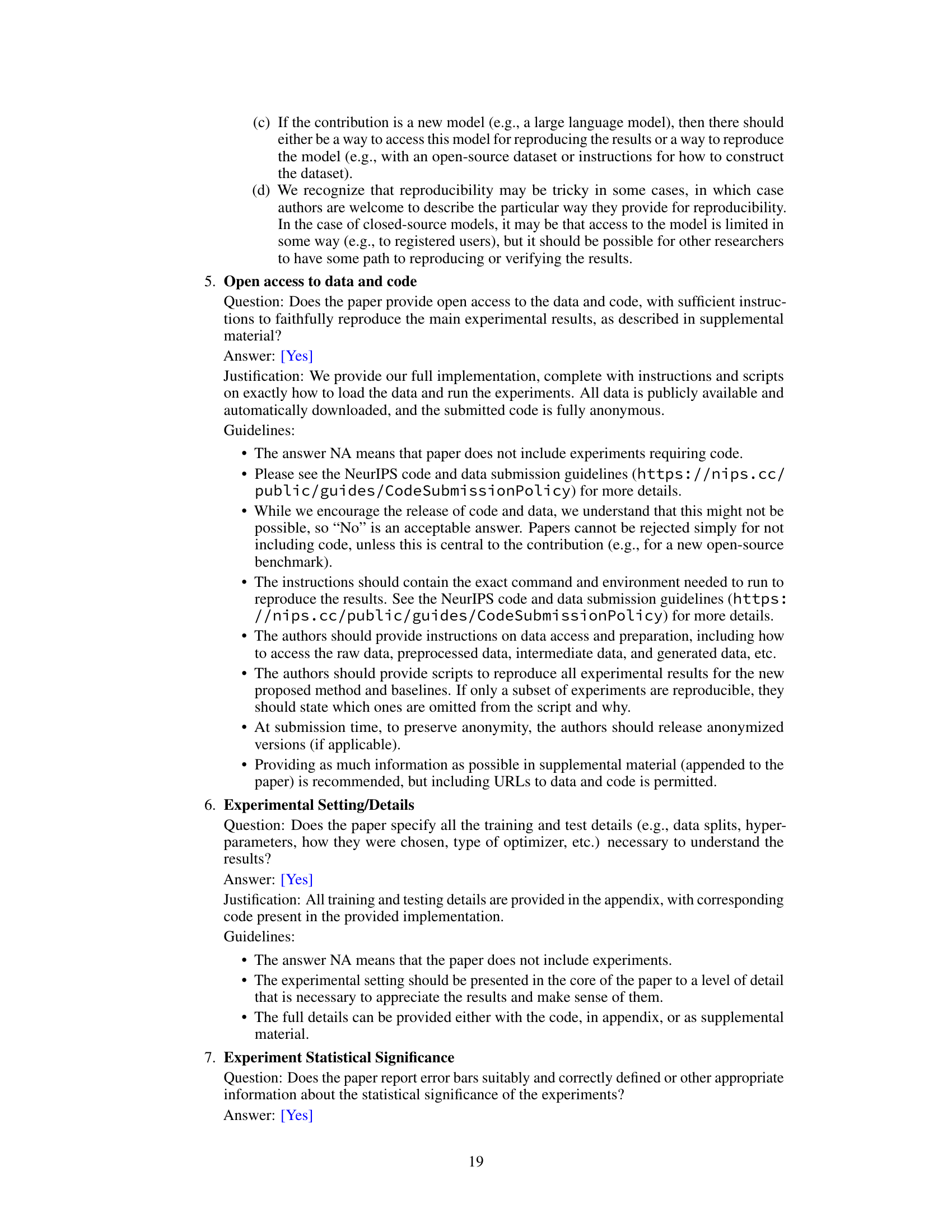

🔼 This figure shows a control flow diagram illustrating probabilistic branching. A probabilistic integer X is input, feeding into a binary random variable C representing a condition. If the condition C is true, X passes to XT and function gT is applied; otherwise (C is false), X passes to X⊥ and function g⊥ is applied. The final output X′ is a weighted sum of the results from the two branches, reflecting the probabilities of the true and false branches of the condition.

read the caption

Figure 4: Control flow diagram for probabilistic branching. The branching condition is probabilistically true and induces a binary random variable C. In each of the two branches we then have two conditionally independent random variables XT and X⊥ to which the functions gT and g⊥ are applied in their respective branches. The probabilities of X′ are then given by the weighted sums of the probabilities of gT(XT) and g⊥(X⊥) (Equation 29).

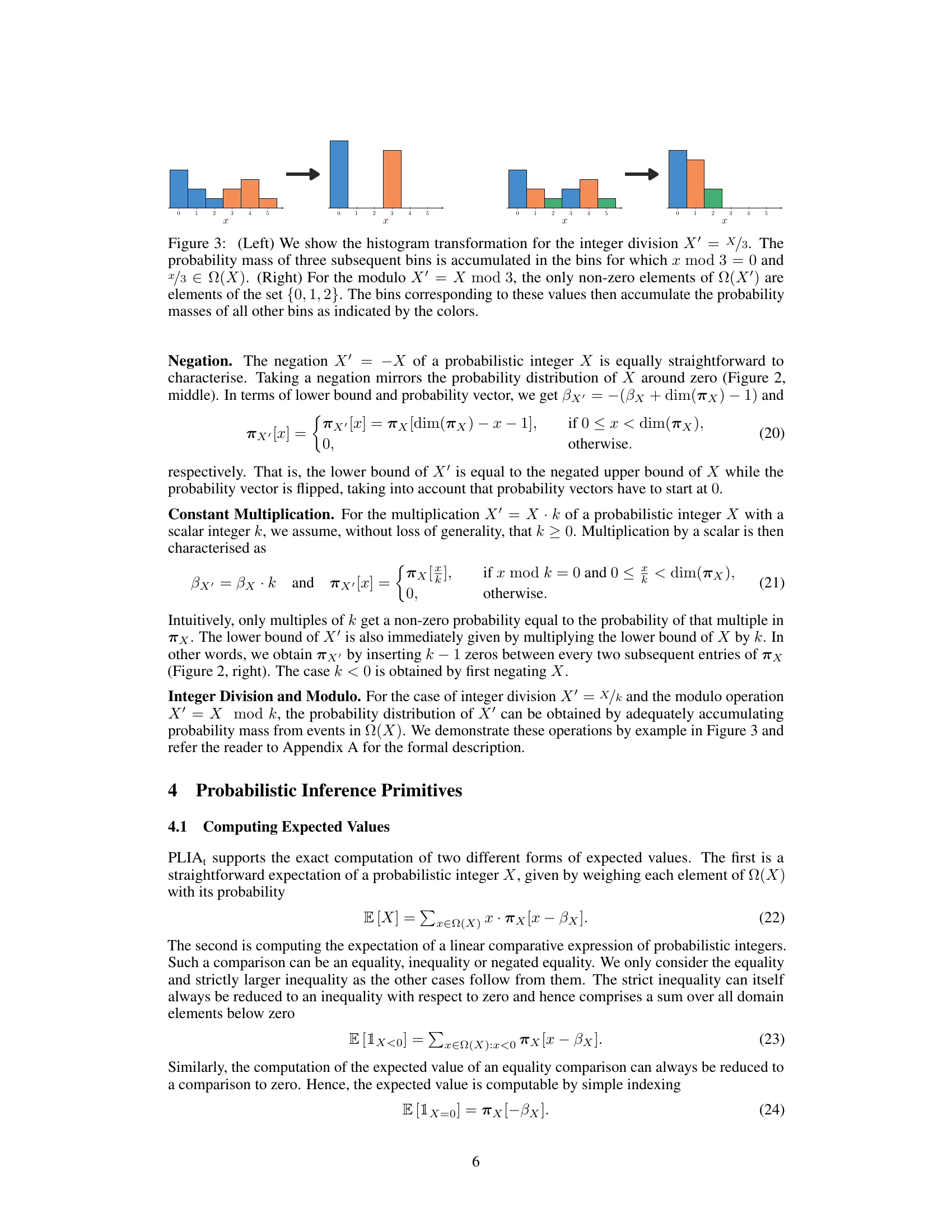

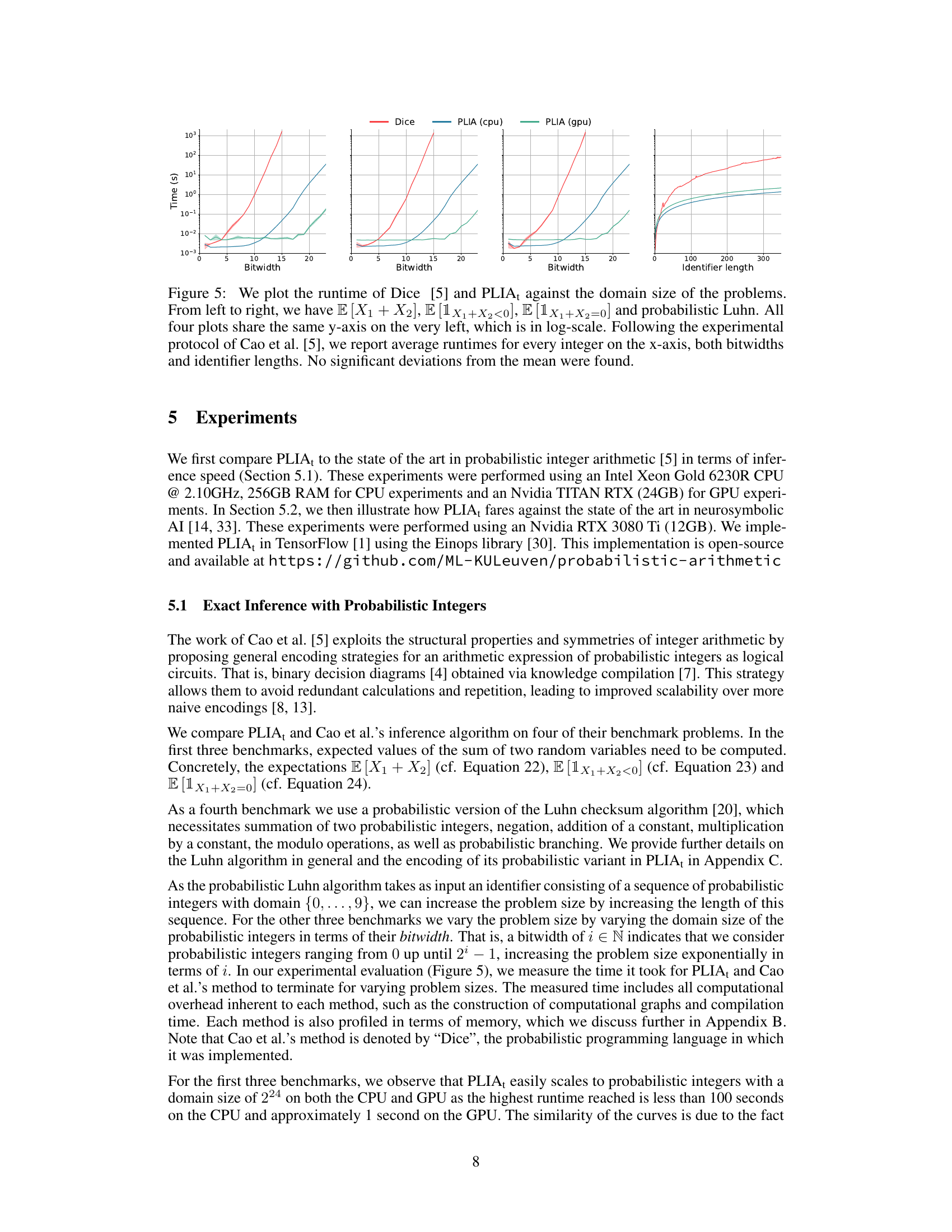

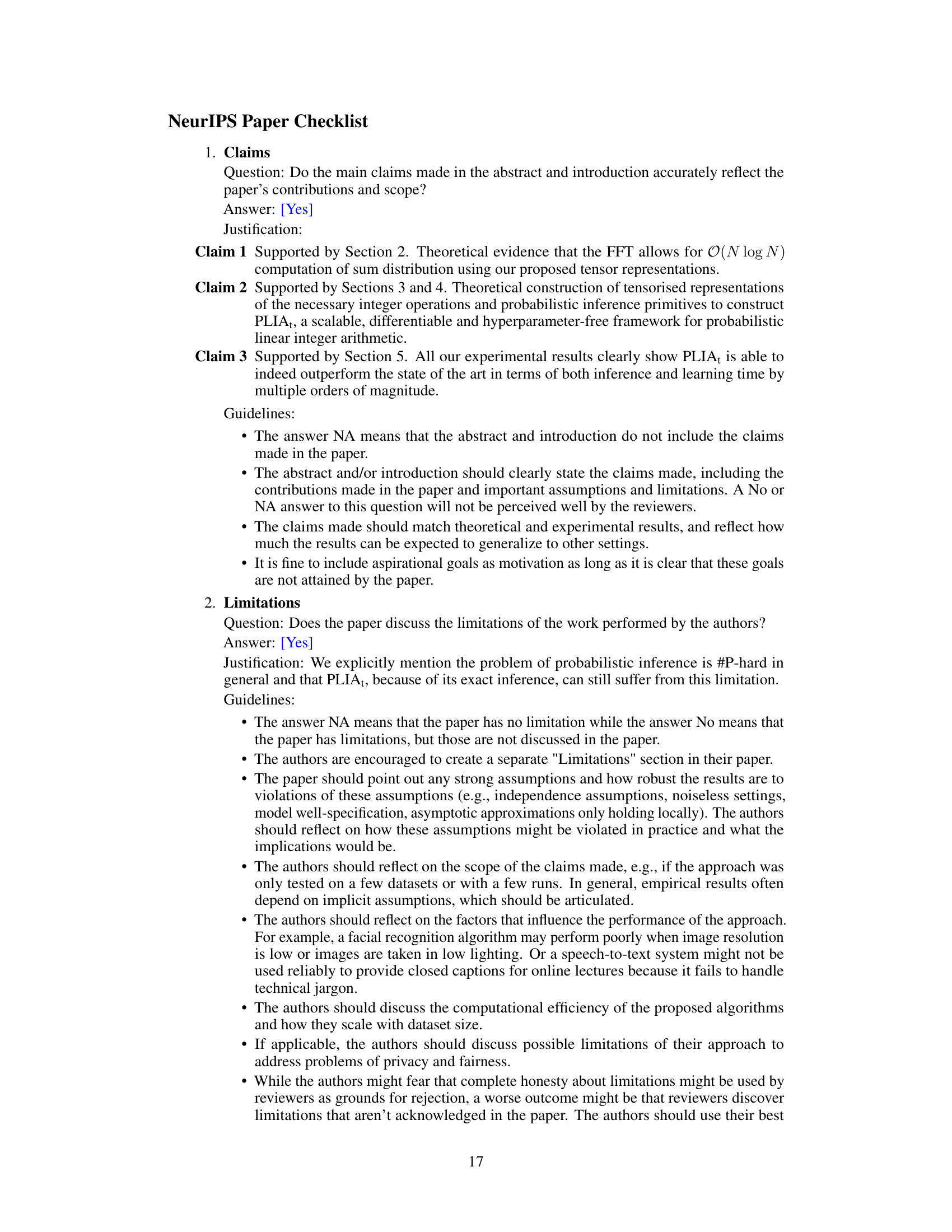

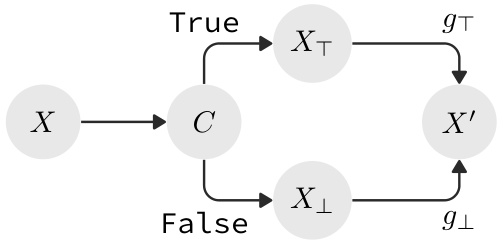

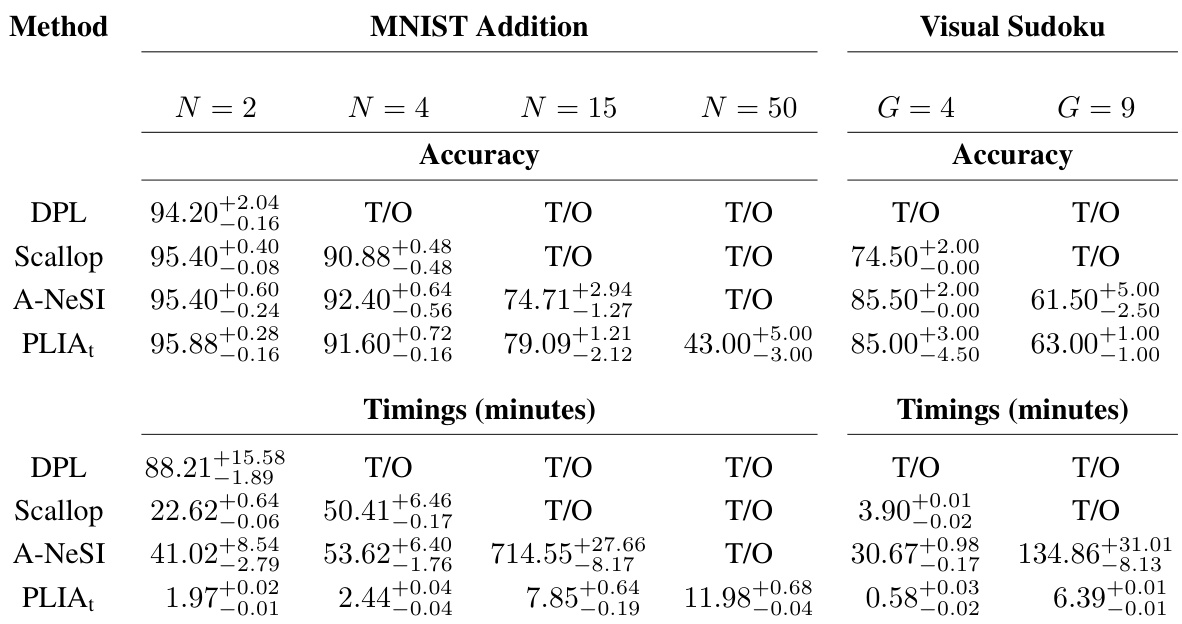

🔼 This figure compares the runtime performance of PLIA₁ and Dice across four different benchmarks: the expected value of the sum of two random variables, the probability of the sum being less than 0, the probability of the sum being equal to 0, and the probabilistic Luhn algorithm. The x-axis represents the domain size of the problem (bitwidth or identifier length), and the y-axis represents the runtime in seconds (log-scale). PLIA₁ shows significantly faster runtimes compared to Dice across all benchmarks, demonstrating its scalability advantages.

read the caption

Figure 5: We plot the runtime of Dice [5] and PLIA₁ against the domain size of the problems. From left to right, we have E[X₁ + X₂], E[1X₁+X₂<0], E[1X₁+X₂=0] and probabilistic Luhn. All four plots share the same y-axis on the very left, which is in log-scale. Following the experimental protocol of Cao et al. [5], we report average runtimes for every integer on the x-axis, both bitwidths and identifier lengths. No significant deviations from the mean were found.

🔼 This figure shows two examples of data points used in the experiments for neurosymbolic learning. The left panel displays an MNIST addition example, where two numbers represented by sequences of MNIST digits are added together to produce a result. This result, an integer, serves as the label for the data point. The right panel shows an example of a visual Sudoku data point. It features a 9x9 grid populated with MNIST digits. The data point’s label is a Boolean value indicating whether the underlying digits satisfy the rules of Sudoku.

read the caption

Figure 6: (Left) Example of an MNIST addition data point, consisting of two numbers given as a series of MNIST digits and an integer. The integer is the sum of the two numbers and constitutes the label of the data point. (Right) Data point from the visual sudoku data set, consisting of a 9 × 9 grid filled with MNIST digits. Data points are labeled with a Boolean value indicating whether the integers underlying the MNIST digits satisfy the constraints of sudoku.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the proposed PLIA₁ method and the existing Dice method for four different probabilistic integer arithmetic problems. The x-axis represents the size of the problem, either in terms of bitwidth or identifier length, and the y-axis represents the runtime in seconds (logarithmic scale). The figure shows that PLIA₁ significantly outperforms Dice, especially for larger problems.

read the caption

Figure 5: We plot the runtime of Dice [5] and PLIA₁ against the domain size of the problems. From left to right, we have E [X₁ + X₂], E [1X₁+X₂<0], E [1X₁+X₂=0] and probabilistic Luhn. All four plots share the same y-axis on the very left, which is in log-scale. Following the experimental protocol of Cao et al. [5], we report average runtimes for every integer on the x-axis, both bitwidths and identifier lengths. No significant deviations from the mean were found.

More on tables

🔼 This table compares the performance of PLIAt against other neurosymbolic methods on two benchmark tasks: MNIST addition and visual Sudoku. It shows median accuracies and training times (in minutes) for different problem sizes (number of digits for addition and grid size for Sudoku). The table highlights PLIAt’s superior efficiency, particularly for larger problem instances, while maintaining competitive accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: In the upper part part we report median test accuracies over 10 runs for the MNIST addition and the visual sudoku benchmarks for varying problem sizes and different neurosymbolic frameworks. Sub- and superscript indicate the 25 and 75 percent quantiles, respectively. In the lower part we report the training times in minutes, again using medians with 25 and 75 percent quantiles. We set the time-out to 24 hours (1440 minutes).

🔼 The table presents a comparison of different neurosymbolic methods (PLIA, DPL, Scallop, A-NeSI) on two benchmark tasks: MNIST addition and visual Sudoku. It shows median accuracy and training times for various problem sizes. The results highlight PLIA’s superior performance in terms of both speed and accuracy, especially as problem complexity increases.

read the caption

Table 1: In the upper part part we report median test accuracies over 10 runs for the MNIST addition and the visual sudoku benchmarks for varying problem sizes and different neurosymbolic frameworks. Sub- and superscript indicate the 25 and 75 percent quantiles, respectively. In the lower part we report the training times in minutes, again using medians with 25 and 75 percent quantiles. We set the time-out to 24 hours (1440 minutes).

Full paper#