TL;DR#

Software vulnerability detection is crucial for system security. Existing deep learning methods often lack sensitivity towards code with multiple functional modules or diverse vulnerability types, hindering their effectiveness in practical applications. This paper proposes a novel approach called KF-GVD, which tackles these issues by integrating specific vulnerability knowledge into the feature learning process of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs).

KF-GVD’s key innovation lies in its ability to accurately detect vulnerabilities across various functional modules and subtypes without compromising general performance. Experimental results showed that KF-GVD outperforms state-of-the-art methods on different detection tasks and discovers 9 undisclosed vulnerabilities. This work provides an improved model, offering a more efficient and accurate approach to vulnerability detection, enhancing system security and reliability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents KF-GVD, a novel method that significantly improves vulnerability detection. It addresses the limitations of existing methods by incorporating task-specific knowledge, leading to higher accuracy and more interpretable results. This is particularly relevant in the context of increasingly complex software systems with diverse vulnerability types and modules, as it offers a scalable and robust approach to identifying vulnerabilities more efficiently and accurately. The method’s high accuracy and interpretability can help improve security practices and facilitate more effective development processes. The 9 undisclosed vulnerabilities discovered further highlight the practical value and impact of the research.

Visual Insights#

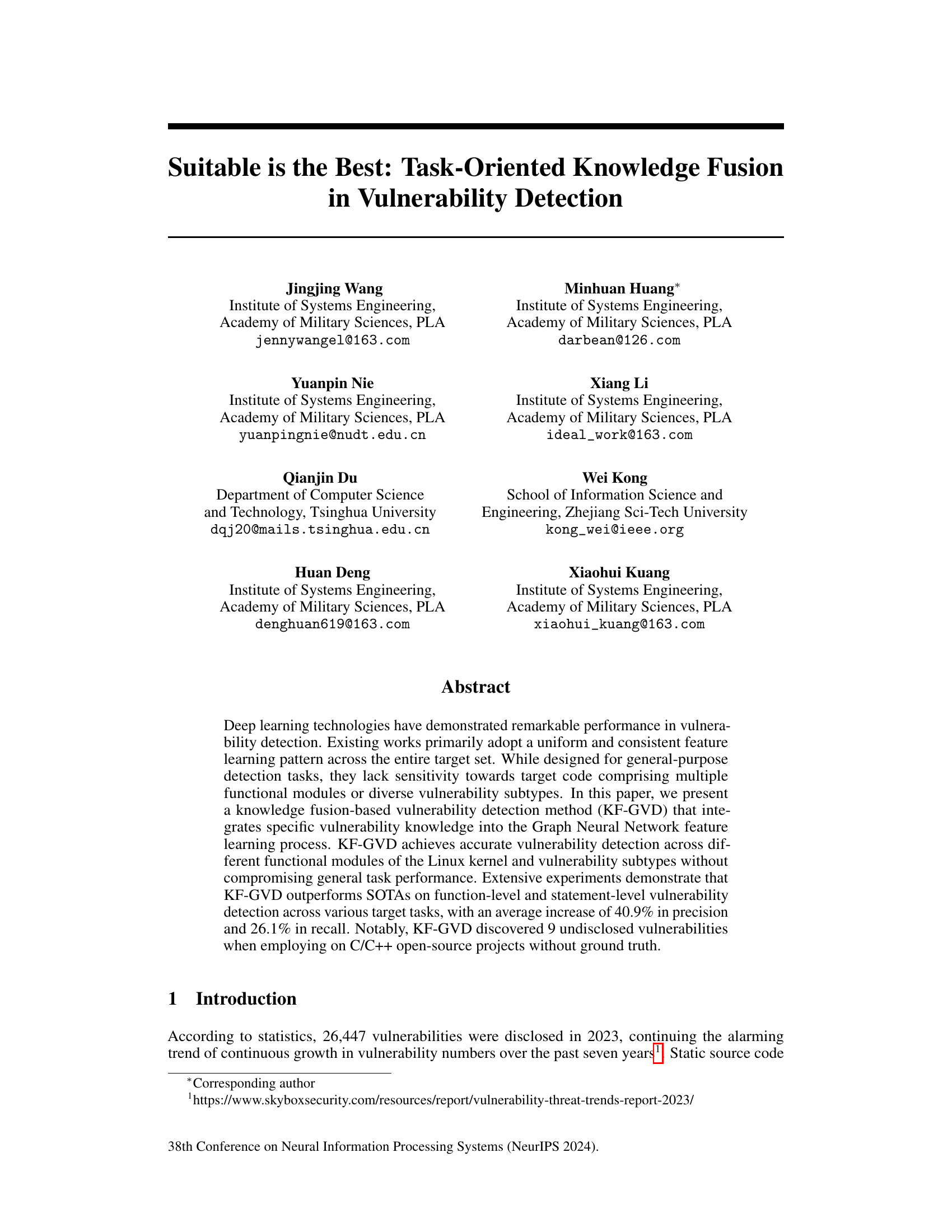

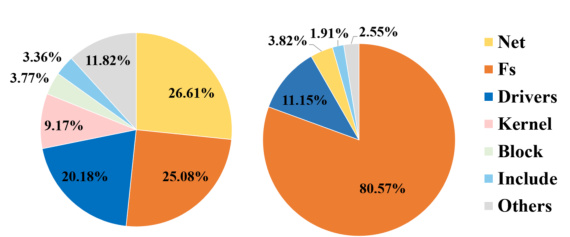

🔼 This figure shows two pie charts visualizing the distribution of CWE-416 (Use After Free) and CWE-119 (Buffer Overflow) vulnerabilities across different modules of the Linux kernel over the past ten years. The left chart represents CWE-416, while the right chart represents CWE-119. Each slice in the pie chart represents a module, and its size is proportional to the number of vulnerabilities found within that module. The charts highlight the disproportionate distribution of vulnerabilities across modules; certain modules are more prone to specific vulnerability types than others.

read the caption

Figure 1: The distribution of CWE-416 (left) and CWE-119 (right) vulnerabilities across all modules in the Linux kernel over the past decade.

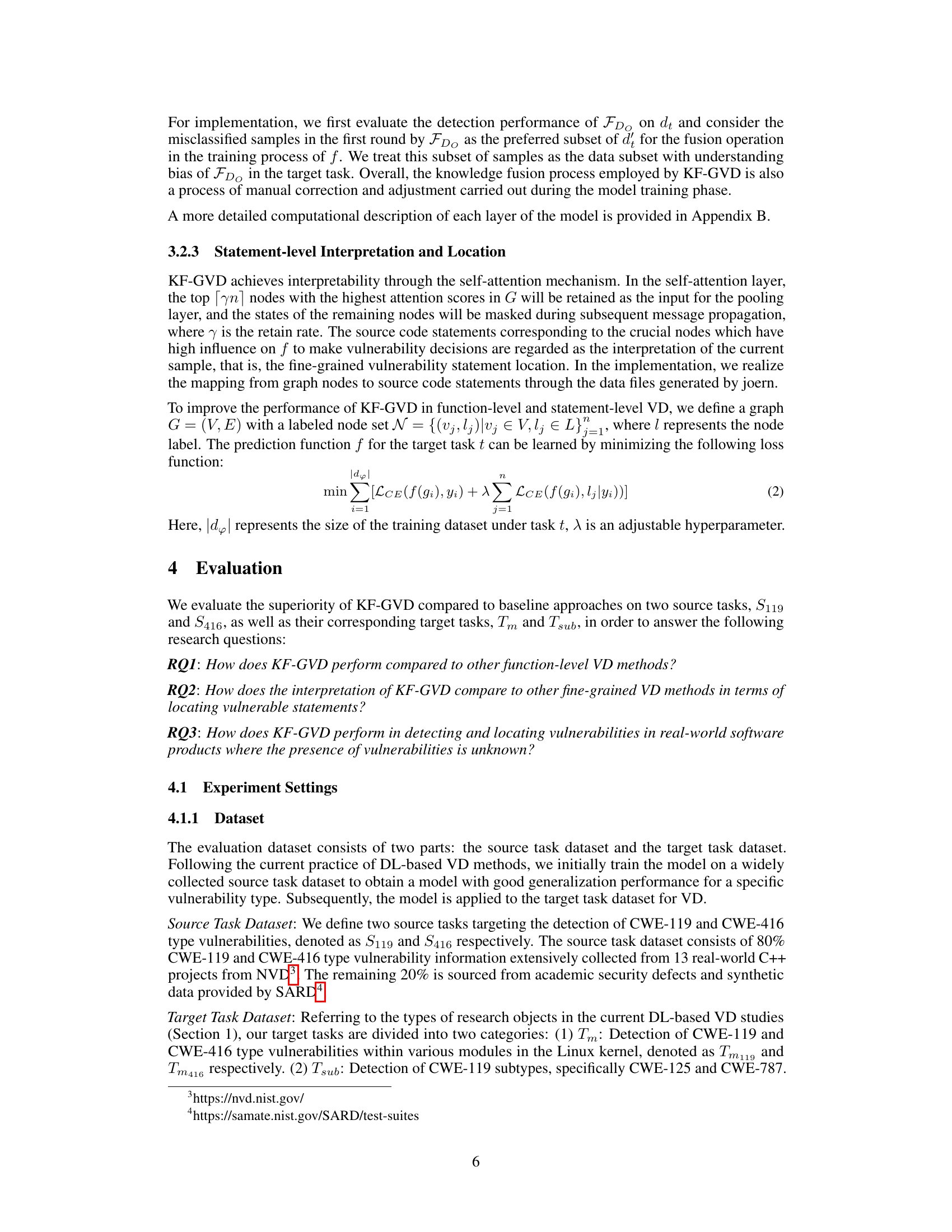

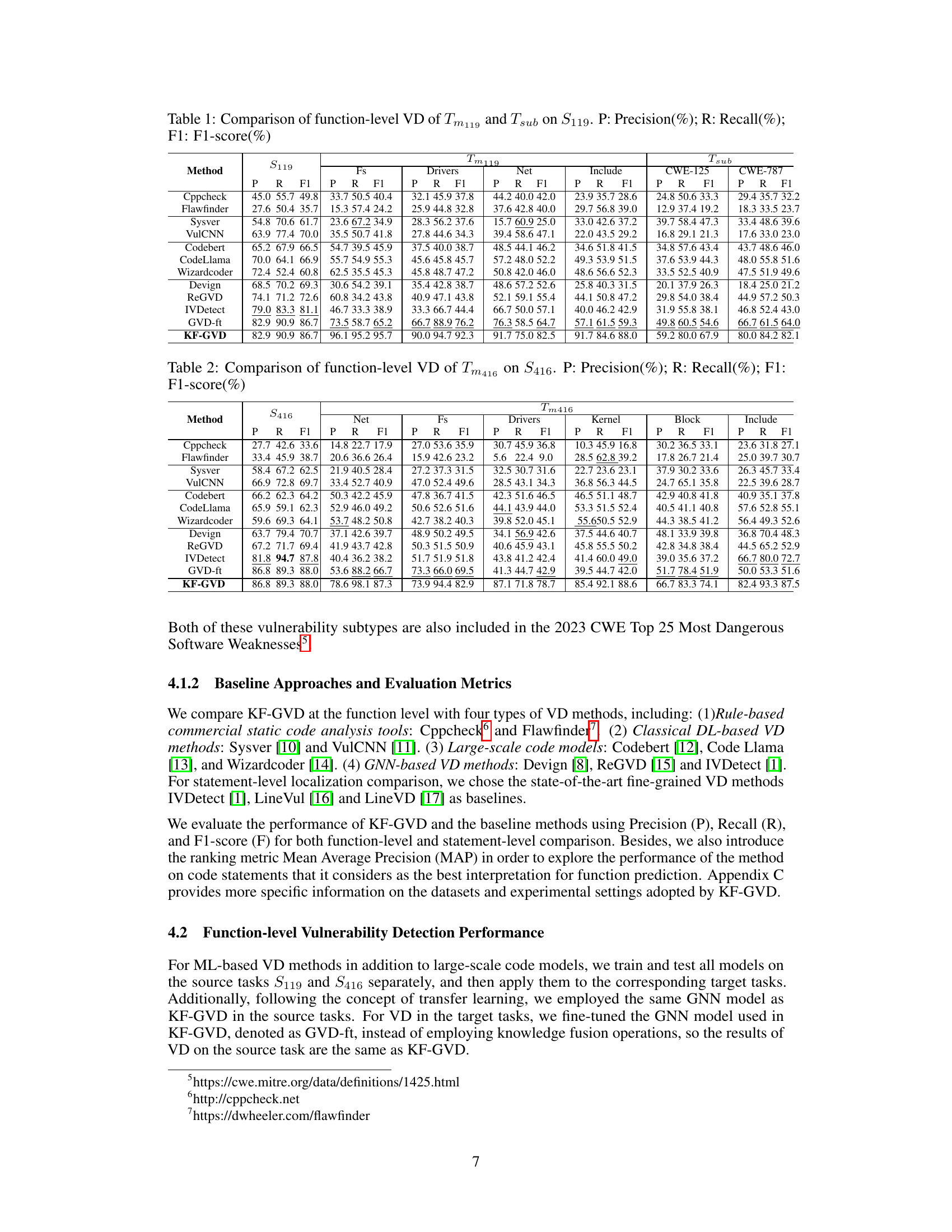

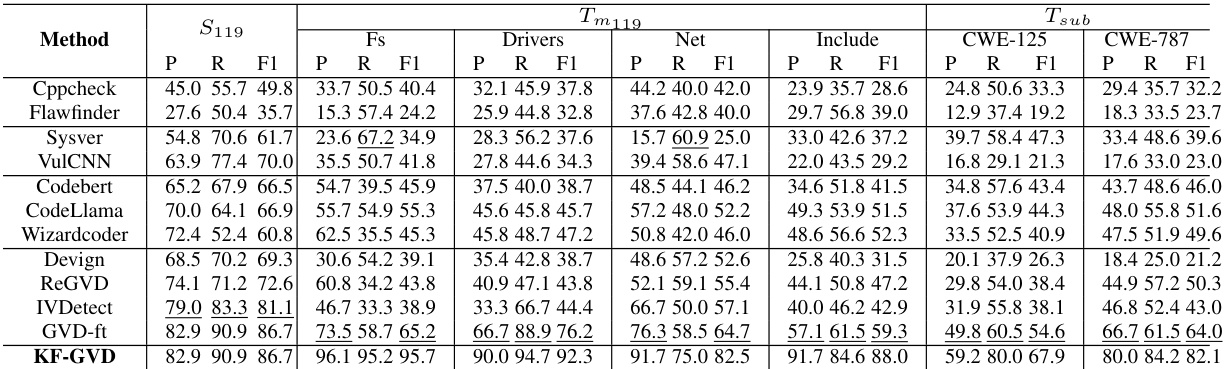

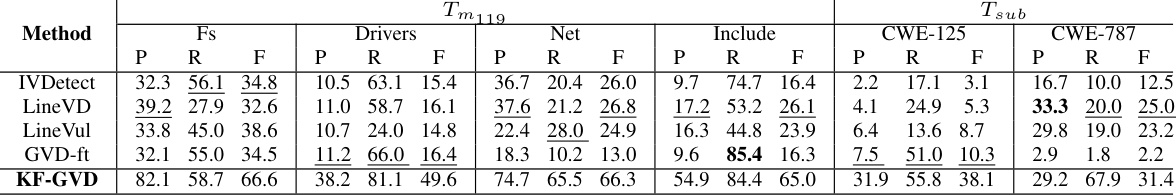

🔼 This table presents the results of function-level vulnerability detection experiments using various methods, including Cppcheck, Flawfinder, and more advanced deep learning approaches like VulCNN and KF-GVD. The performance metrics (Precision, Recall, and F1-score) are compared across different modules (Fs, Drivers, Net, Include) for two target tasks (Tm119 and Tsub) using the S119 source task dataset. The table allows assessing the relative effectiveness of various vulnerability detection methods and their ability to generalize performance across diverse code modules and subtypes.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of function-level VD of and on . P: Precision(%); R: Recall(%); F1: F1-score(%)

In-depth insights#

Task-Oriented Fusion#

The concept of “Task-Oriented Fusion” in a vulnerability detection context suggests a paradigm shift from generic, model-agnostic approaches to specialized, task-aware methodologies. Instead of training a single model to identify all vulnerabilities across diverse codebases, this approach advocates tailoring the model’s learning process to specific tasks (e.g., detecting buffer overflows in a kernel module versus use-after-free errors in a library). This involves incorporating relevant task-specific knowledge, such as code patterns associated with particular vulnerabilities or module functionalities, directly into the model’s architecture or training process. The key benefit is enhanced sensitivity and precision in identifying vulnerabilities within specific contexts, which leads to fewer false positives and ultimately more effective vulnerability remediation. This targeted approach may also improve generalization to new, unseen tasks within the same domain, compared to models that only learn from a broad spectrum of data. However, challenges remain in efficiently managing the complexity of multiple models, and in defining and extracting the most effective knowledge for each specific task. Furthermore, the effectiveness will heavily rely on the quality and completeness of available task-specific data, which might be scarce for certain rare vulnerability types or specialized software components.

GNN-based Approach#

A GNN-based approach leverages the power of graph neural networks to model relationships within data, making it particularly well-suited for analyzing complex structured information such as source code. In vulnerability detection, this translates to representing code as a graph, where nodes are code elements (functions, variables, etc.) and edges represent dependencies or relationships between them. This graph representation allows the GNN to capture intricate patterns and contextual information crucial for identifying vulnerabilities that might be missed by traditional methods. The effectiveness of such an approach depends heavily on the quality of the graph construction and the specific GNN architecture employed. Key advantages include the ability to handle complex code structures and incorporate both local and global context into vulnerability predictions. However, challenges remain in generating high-quality code graphs, designing efficient and scalable GNN architectures, and ensuring the interpretability of the model’s predictions to facilitate understanding by security professionals. The choice of graph features and the GNN’s architecture profoundly impact the model’s accuracy and efficiency.

Knowledge Subgraphs#

Knowledge subgraphs represent a powerful technique for incorporating domain expertise into machine learning models. In the context of vulnerability detection, these subgraphs, derived from Code Property Graphs (CPGs), encapsulate crucial information regarding specific vulnerabilities. By focusing on relevant code sections and operations linked to certain vulnerabilities, they allow the model to concentrate its learning on the most critical aspects. This targeted approach improves the model’s sensitivity and accuracy, especially when dealing with complex systems like the Linux kernel, where vulnerabilities can exhibit diverse characteristics across functional modules. The selection of nodes and edges within the CPG to form these knowledge subgraphs is a critical step, potentially leveraging expert knowledge, static analysis rules, or patterns observed in historical vulnerability data. The effectiveness of this approach hinges on the quality and relevance of the selected knowledge subgraph. An improperly constructed subgraph could hinder the model’s performance or introduce biases. Ultimately, the concept of knowledge subgraphs highlights the value of integrating human expertise into machine learning for enhanced accuracy and interpretability in complex tasks like vulnerability detection.

Interpretability Aspects#

Interpretability in machine learning models, especially those applied to critical domains like vulnerability detection, is paramount. A model’s interpretability, or the ability to understand its decision-making process, directly impacts trust and allows for debugging and refinement. In the context of vulnerability detection, interpretability could reveal why a specific code segment was flagged, helping developers understand the model’s reasoning and verify its findings, leading to more effective remediation. Conversely, a lack of interpretability hinders debugging, making it difficult to identify and correct errors in the model or to ascertain whether the model’s conclusions are valid. Techniques to enhance interpretability, such as attention mechanisms or visualization tools, are essential for building trustworthy AI systems for security purposes. For instance, highlighting the specific code sections that significantly influenced the model’s prediction can provide valuable insights for security analysts and developers. This approach moves beyond simple classification towards a more nuanced understanding, boosting efficiency and accuracy. Future research should focus on creating more explainable AI (XAI) methods specifically designed for vulnerability detection, balancing the complexity of code analysis with the need for transparent model outputs. This would foster increased confidence and wider adoption of AI-driven security solutions.

Future Enhancements#

Future enhancements for the research could involve exploring more sophisticated graph neural network architectures to better capture complex relationships within code. Incorporating additional code features beyond those currently used could also improve accuracy and generalizability. Furthermore, a focus on handling larger and more complex codebases is crucial, particularly as the scale of software projects grows. The current study is limited to certain types of vulnerabilities and specific programming languages; future work could expand the scope to encompass a broader range of vulnerability types and programming languages. Addressing the computational cost of the current model, especially for larger-scale projects, is necessary for practical applications. Improving the interpretability of the model’s predictions would also significantly enhance its value for developers. Finally, exploring the potential of transfer learning techniques to improve model generalization across different codebases and vulnerability types warrants investigation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

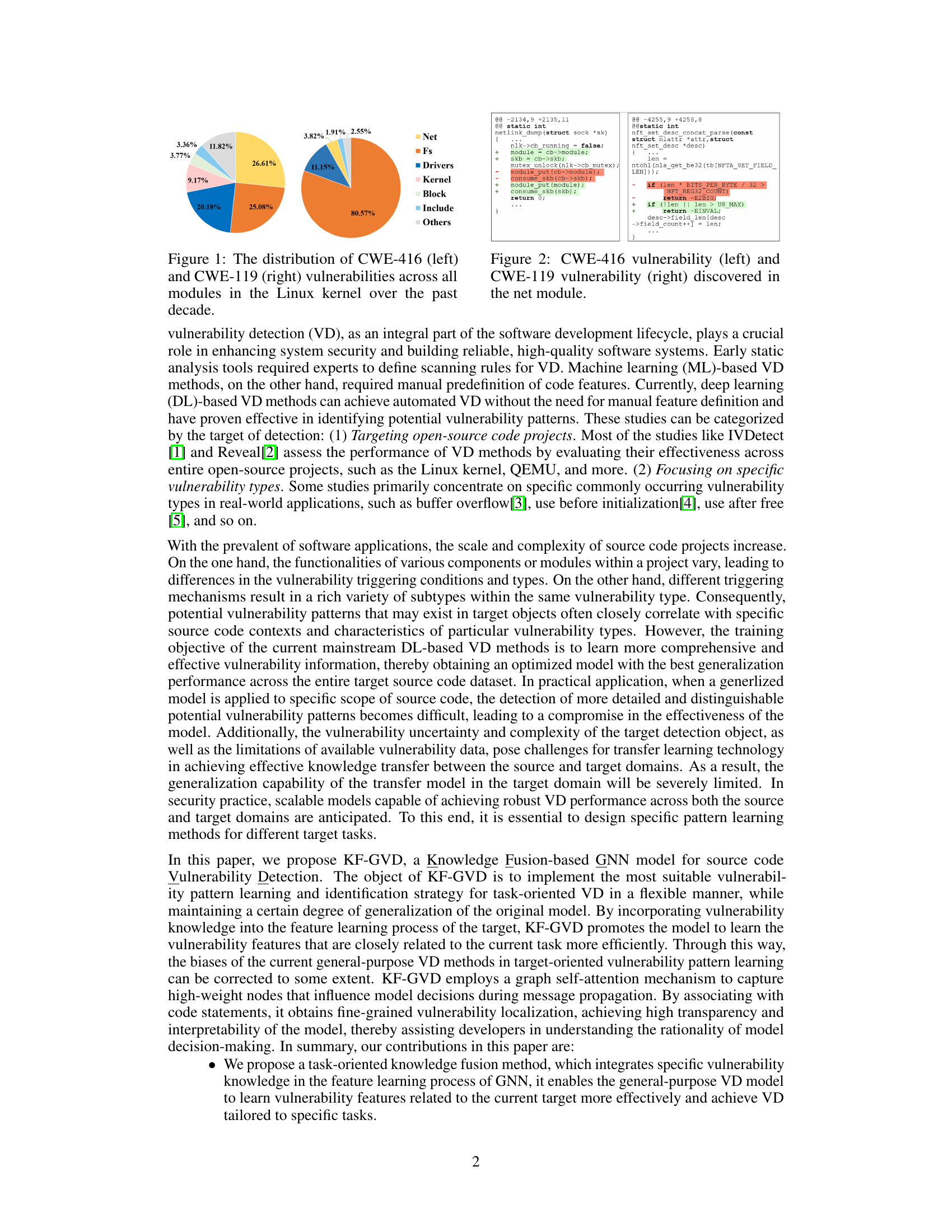

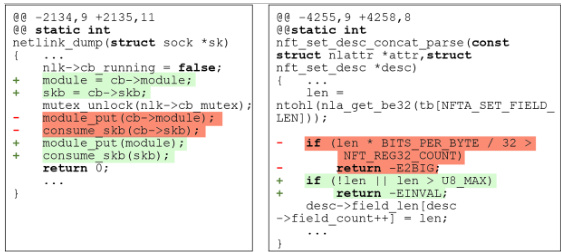

🔼 This figure shows examples of CWE-416 (Use After Free) and CWE-119 (Buffer Overflow) vulnerabilities found in the ’net’ module of the Linux kernel. The left panel displays a CWE-416 vulnerability involving a race condition with pointer-related resource leakage. The right panel shows a CWE-119 vulnerability related to insufficient checks in network protocol fields. The examples highlight how different vulnerability types can manifest within the same module, demonstrating the need for task-oriented vulnerability detection.

read the caption

Figure 2: CWE-416 vulnerability (left) and CWE-119 vulnerability (right) discovered in the net module.

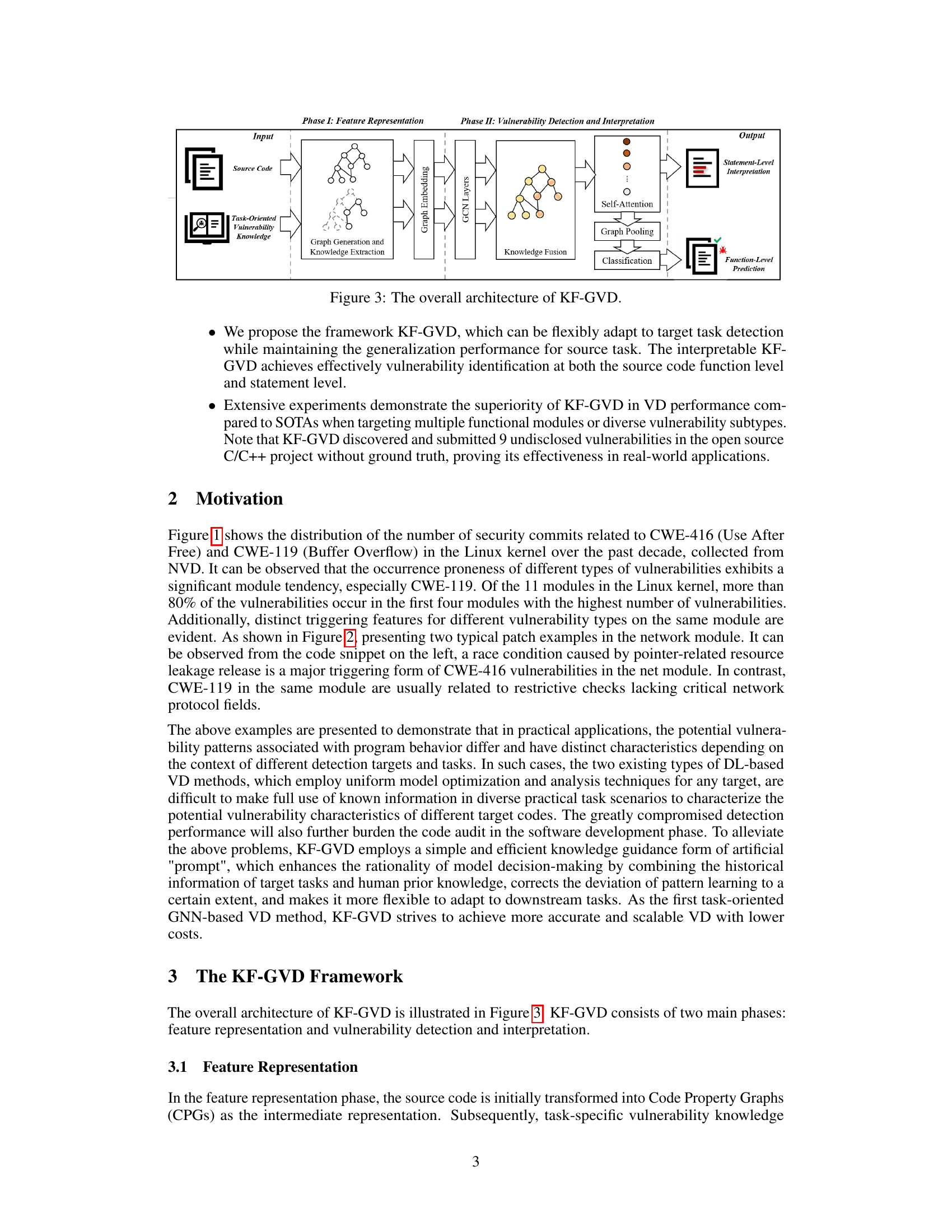

🔼 The figure illustrates the overall architecture of the KF-GVD model, which consists of two main phases: feature representation and vulnerability detection and interpretation. In the feature representation phase, source code is transformed into Code Property Graphs (CPGs), and task-specific vulnerability knowledge is integrated. Then, graph embedding, GCN layers, and self-attention are used to extract features. The vulnerability detection and interpretation phase involves knowledge fusion, graph pooling, classification, and statement-level interpretation to output both function-level prediction and statement-level interpretation.

read the caption

Figure 3: The overall architecture of KF-GVD.

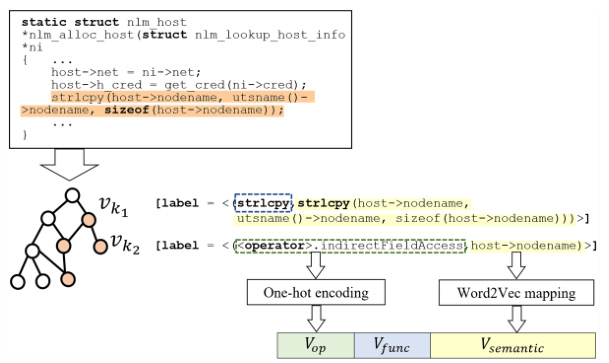

🔼 This figure shows an example of how the source code is transformed into a Code Property Graph (CPG) and then into node feature vectors. The CPG visually represents the code’s structure and relationships. The node feature vectors combine three types of information: Vop (code element operation type, one-hot encoding), Vfunc (special function calls/code field types, one-hot encoding), and Vsemantic (semantic information from code statements, Word2Vec mapping). These combined vectors are used as the input for the next step in the KF-GVD model.

read the caption

Figure 4: An example of feature representation.

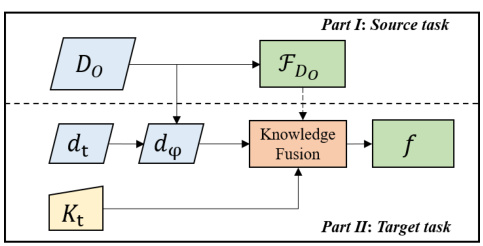

🔼 This figure illustrates the workflow of the KF-GVD model. It is divided into two parts: the source task and the target task. In the source task, a model FDo is trained on a dataset Do. In the target task, knowledge Kt is integrated into the model using a knowledge fusion step. The fusion combines the knowledge Kt with the pre-trained model FDo and the dataset dt to generate a specialized model f that is more effective for the target task.

read the caption

Figure 5: The workflow of KF-GVD.

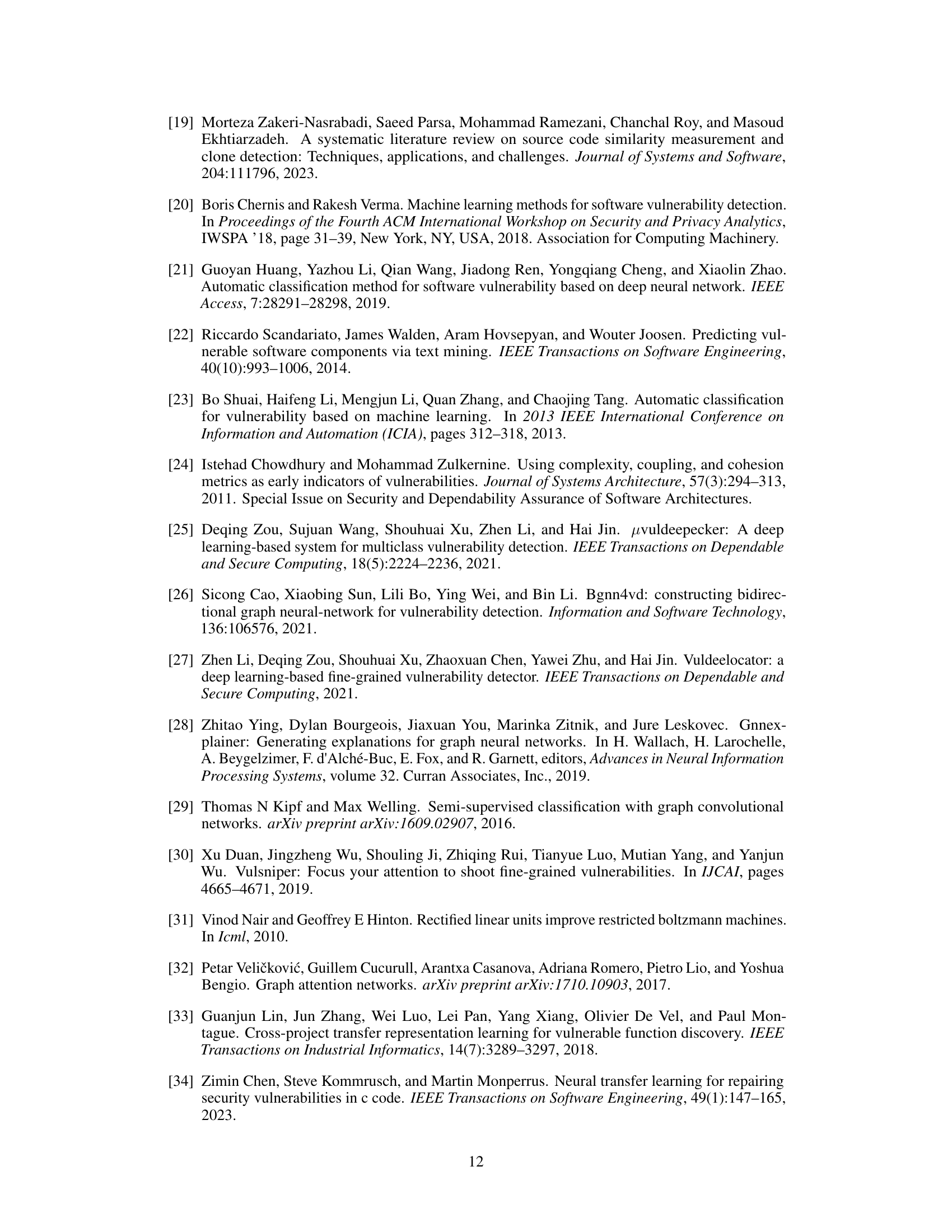

🔼 This figure compares the performance of various statement-level vulnerability detection (VD) methods across three target tasks (Tm119, Tsub, Tm416). The methods compared are IVDetect, LineVD, LineVul, GVD-ft, and KF-GVD. The metric used is Mean Average Precision at 5 (MAP@5), indicating the average precision of the top 5 most confidently predicted vulnerable statements. KF-GVD consistently outperforms other methods in MAP@5 across all three target tasks, demonstrating its superiority in precisely locating vulnerable statements.

read the caption

Figure 6: Statement-level VD comparison on MAP@5.

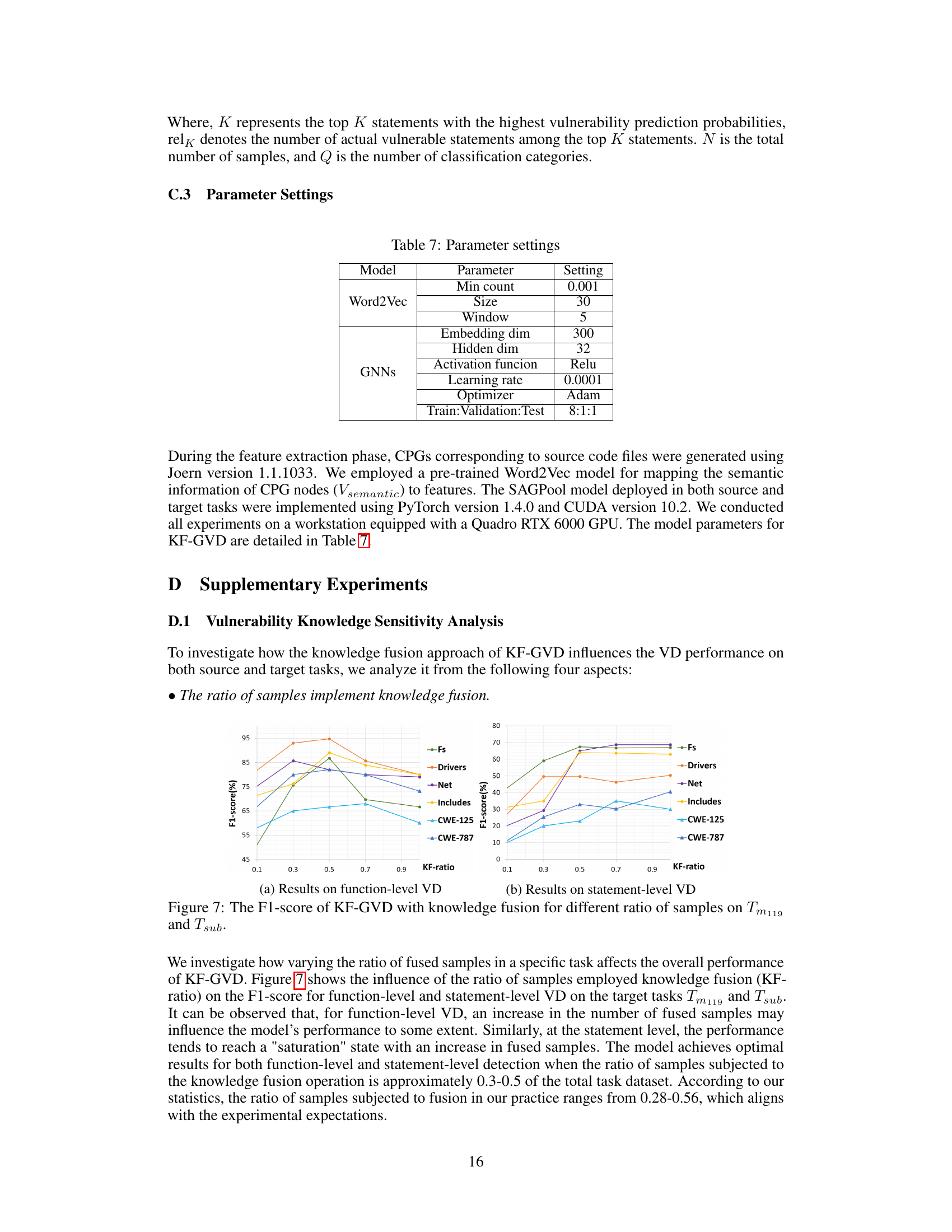

🔼 This figure shows the impact of the ratio of samples using knowledge fusion on the F1-score for function-level and statement-level vulnerability detection. The x-axis represents the ratio of samples where knowledge fusion was applied, and the y-axis shows the F1-score. Separate lines are shown for different modules (Fs, Drivers, Net, Includes) and CWE subtypes (CWE-125, CWE-787) in both function-level and statement-level analyses. The graph indicates the optimal range for knowledge fusion, showing that the model achieves its peak performance when a certain proportion of samples undergo knowledge fusion.

read the caption

Figure 7: The F1-score of KF-GVD with knowledge fusion for different ratio of samples on Tm119 and Tsub.

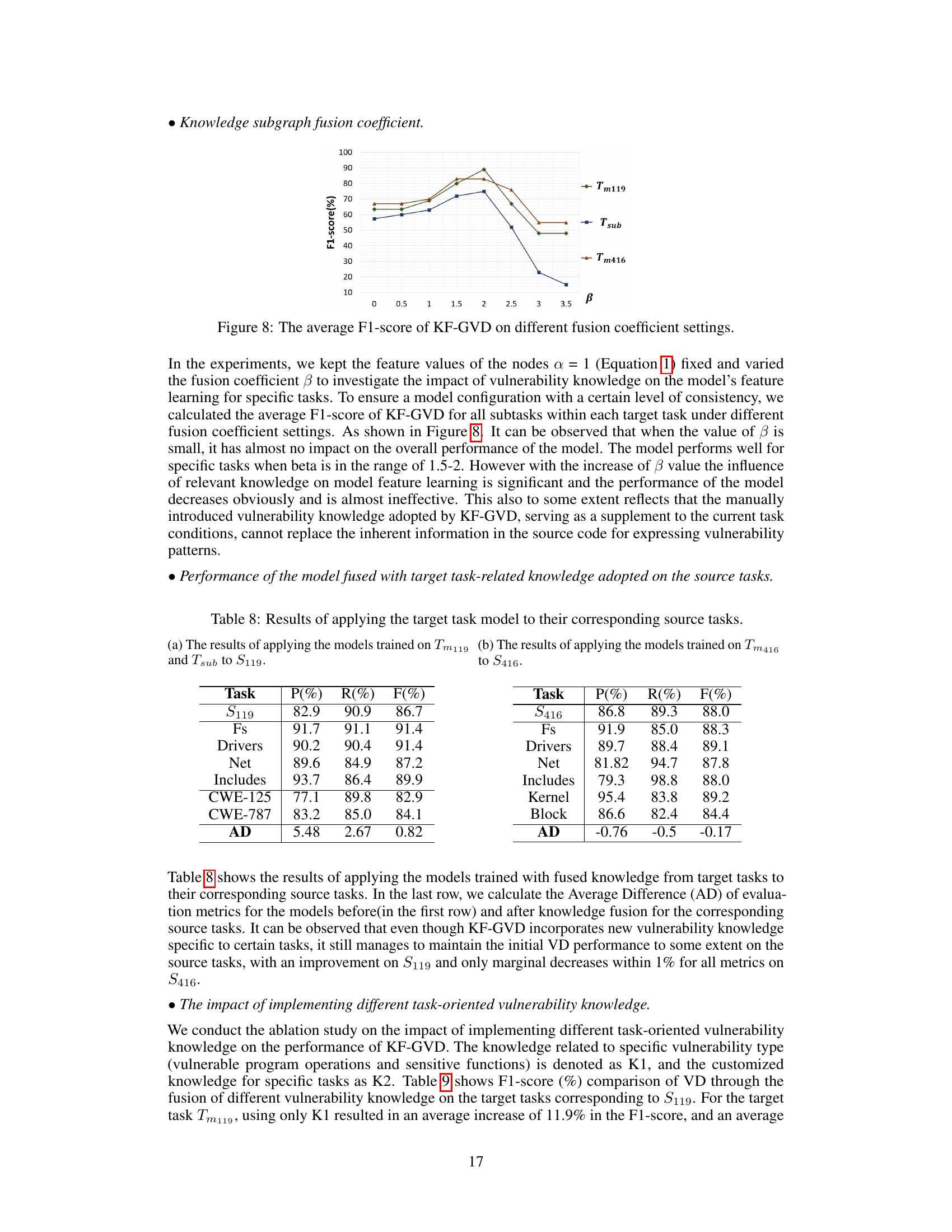

🔼 This figure shows the impact of the knowledge fusion coefficient (β) on the performance of the KF-GVD model. The x-axis represents different values of β, and the y-axis represents the average F1-score across various subtasks within three target tasks (Tm119, Tsub, and Tm416). The graph illustrates how changing β affects the model’s ability to integrate vulnerability knowledge, influencing the precision and recall of vulnerability detection.

read the caption

Figure 8: The average F1-score of KF-GVD on different fusion coefficient settings.

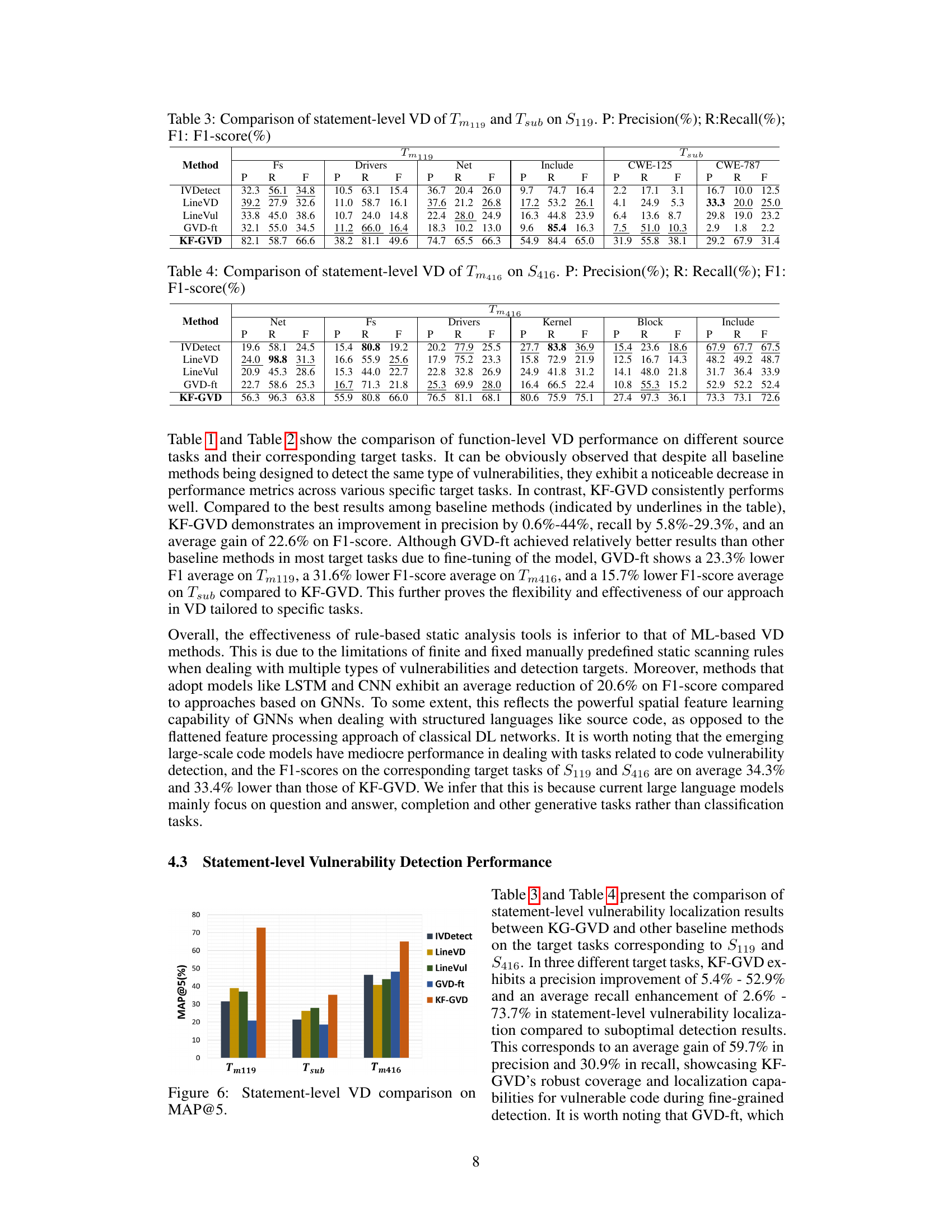

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the results of function-level vulnerability detection experiments on the target task Tm416 (CWE-416 vulnerabilities in various modules of the Linux kernel) using the source task dataset S416 (CWE-416 vulnerabilities). It compares the performance of KF-GVD with several baseline methods (Cppcheck, Flawfinder, Sysver, VulCNN, Codebert, CodeLlama, Wizardcoder, Devign, ReGVD, IVDetect, GVD-ft) across different modules (Fs, Net, Drivers, Kernel, Block, Include). The evaluation metrics used are Precision (P), Recall (R), and F1-score (F1), all expressed as percentages.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of function-level VD of Tm416 on S416. P: Precision(%); R: Recall(%); F1: F1-score(%)

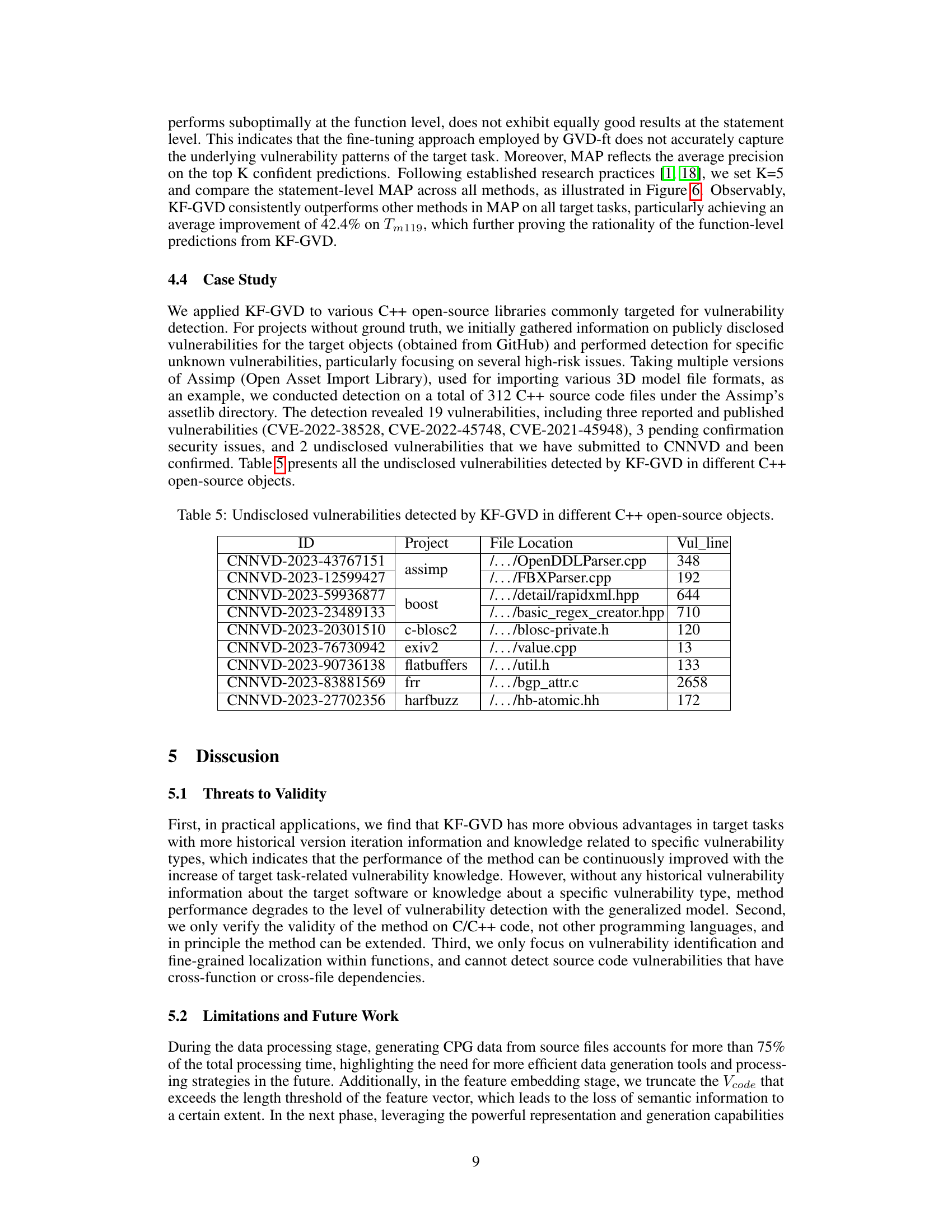

🔼 This table presents the results of statement-level vulnerability detection (VD) experiments. It compares the performance of several methods (IVDetect, LineVD, LineVul, GVD-ft, and KF-GVD) on two target tasks (Tm119 and Tsub) using the S119 dataset as a source task. The table shows precision (P), recall (R), and F1-score (F) for each method on different modules (Fs, Drivers, Net, Include) and CWE subtypes (CWE-125 and CWE-787). The metrics assess the effectiveness of the methods at locating vulnerabilities at the statement level within the code.

read the caption

Table 3: Comparison of statement-level VD of Tm119 and Tsub on S119. P: Precision(%); R:Recall(%); F1: F1-score(%)

🔼 This table presents the results of function-level vulnerability detection (VD) experiments for the target task Tm416 (detecting CWE-416 vulnerabilities in various Linux kernel modules) using the source task dataset S416. It compares the performance of KF-GVD against several baseline methods, including Cppcheck, Flawfinder, Sysver, VulCNN, Codebert, CodeLlama, Wizardcoder, Devign, ReGVD, IVDetect, and GVD-ft. The metrics used are Precision (P), Recall (R), and F1-score (F1), all expressed as percentages. The table provides a breakdown of results for each of the Linux kernel modules: Net, Fs, Drivers, Kernel, Block, and Include.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of function-level VD of Tm416 on S416. P: Precision(%); R: Recall(%); F1: F1-score(%)

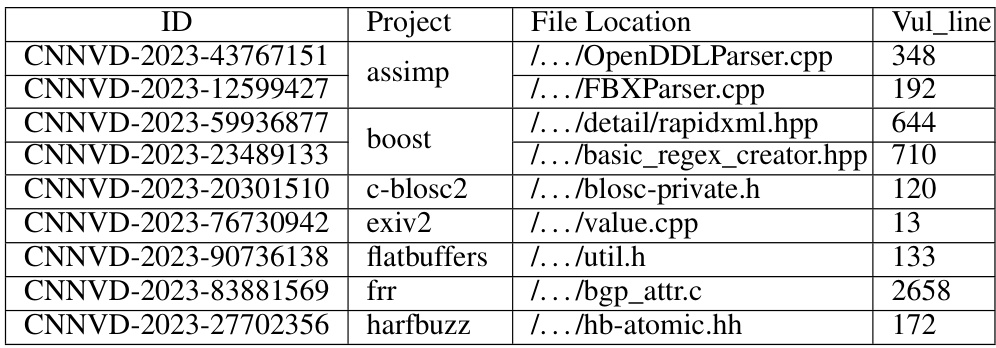

🔼 This table lists 9 undisclosed vulnerabilities discovered by the KF-GVD model in various open-source C++ projects. Each row represents a unique vulnerability, providing its CNNVD ID, the project it was found in, the specific file and line number where the vulnerability resides. This demonstrates the model’s ability to find previously unknown vulnerabilities.

read the caption

Table 5: Undisclosed vulnerabilities detected by KF-GVD in different C++ open-source objects.

🔼 This table presents the statistics of four different datasets used in the paper’s experiments. The datasets are categorized as source tasks (S119 and S416) and target tasks (Tm and Tsub). For each dataset, the table shows the number of code files, the ratio of vulnerable to non-vulnerable code samples (Vul: Non-Vul), and the label granularity used (Function or Function, statement, indicating whether the vulnerability labels are assigned at the function level or also at the statement level).

read the caption

Table 6: Dataset statistics

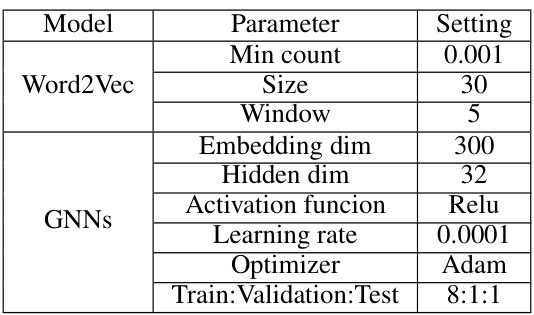

🔼 This table shows the hyperparameters used for the Word2Vec model and the Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) in the KF-GVD framework. It specifies settings for parameters like minimum count, size, window, embedding dimension, hidden dimension, activation function, learning rate, optimizer, and the train/validation/test data split ratio.

read the caption

Table 7: Parameter settings

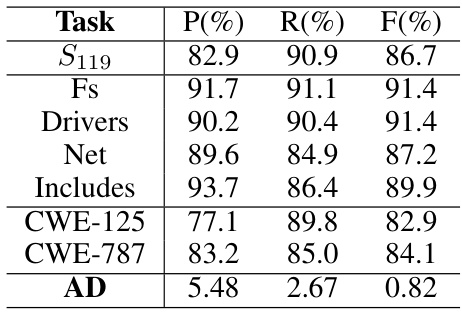

🔼 This table presents the results of applying models trained on specific target tasks (Tm119 and Tsub) to their corresponding source task (S119). It demonstrates the model’s generalization capabilities and shows the performance differences between models trained for specific subtasks versus the general model. The final row, ‘AD’, indicates the average differences in precision (P), recall (R), and F1-score (F) between the models trained on the target tasks and the models initially trained only on the source task.

read the caption

Table 8: Results of applying the models trained on Tm119 and Tsub to S119.

🔼 This table presents the results of function-level vulnerability detection (VD) for target task Tm416 (detecting CWE-416 vulnerabilities in various modules of the Linux kernel) using the source task dataset S416. It compares the performance of KF-GVD against several baseline methods (Cppcheck, Flawfinder, Sysver, VulCNN, Codebert, CodeLlama, Wizardcoder, Devign, ReGVD, IVDetect, and GVD-ft). The metrics used for comparison are Precision (P), Recall (R), and F1-score (F1). The table shows the performance across different modules of the Linux kernel: Fs, Net, Drivers, Kernel, Block, and Includes.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of function-level VD of Tm416 on S416. P: Precision(%); R: Recall(%); F1: F1-score(%)

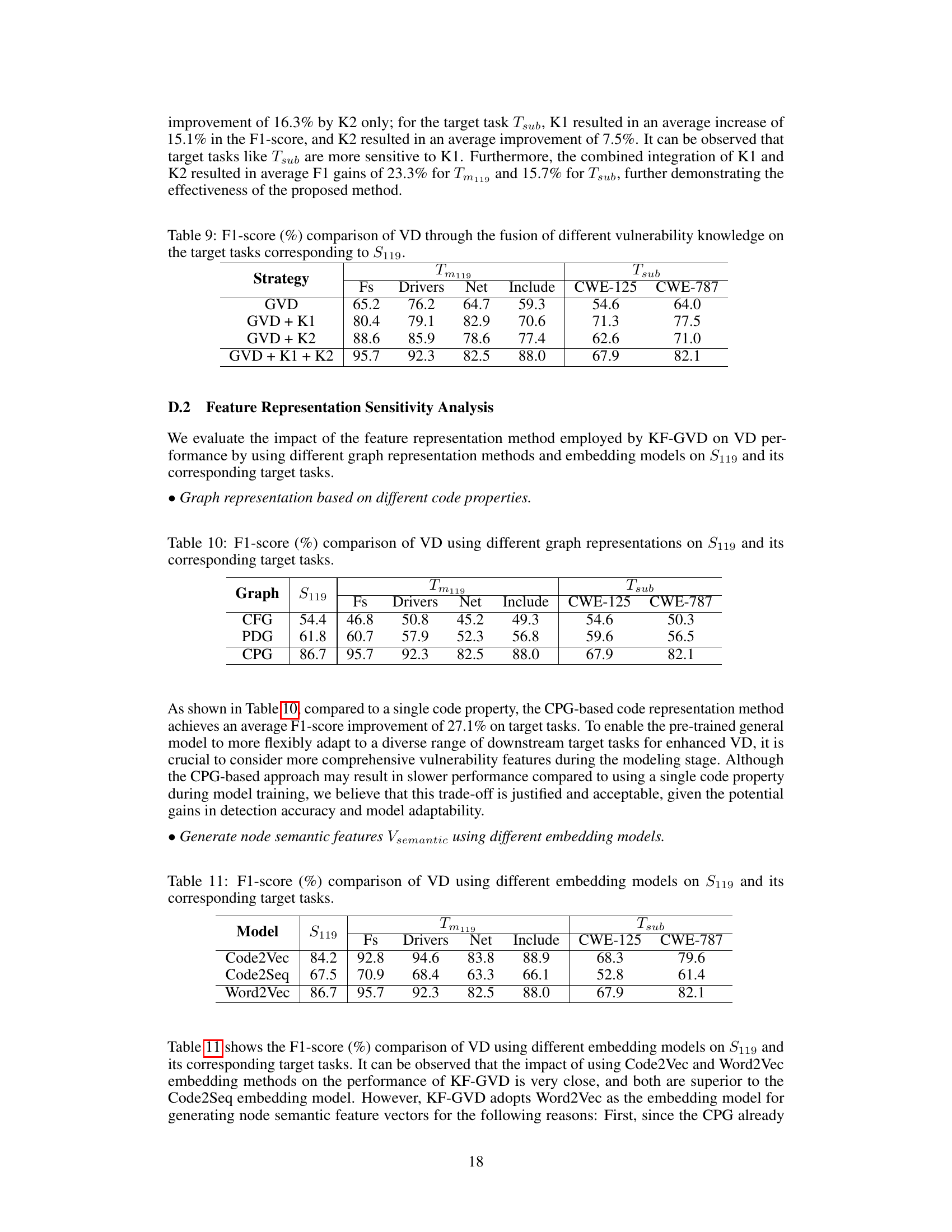

🔼 This table presents the results of function-level vulnerability detection (VD) experiments on the target tasks (Tm119 and Tsub) corresponding to the source task S119. It compares the performance of the general-purpose VD model (GVD) with different combinations of vulnerability knowledge (K1 and K2) integrated into the model. K1 represents knowledge about vulnerable program operations and sensitive functions relevant to the vulnerability type. K2 represents customized knowledge for specific tasks related to the target functional scenarios. The table shows the F1-scores for each target task and module (Fs, Drivers, Net, Include), as well as for specific CWE subtypes (CWE-125 and CWE-787). The results demonstrate the impact of integrating specific vulnerability knowledge on the model’s performance.

read the caption

Table 9: F1-score (%) comparison of VD through the fusion of different vulnerability knowledge on the target tasks corresponding to S119.

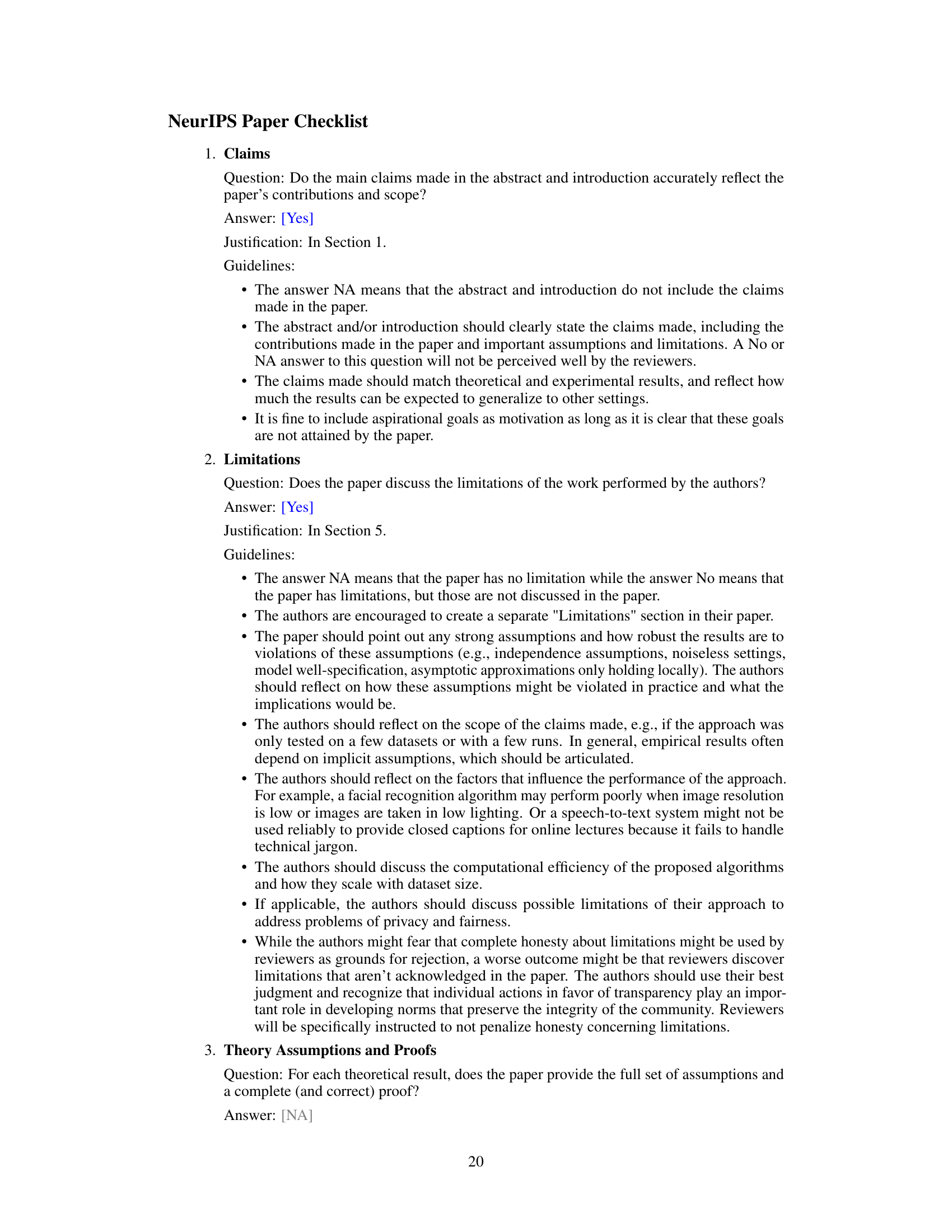

🔼 This table presents the F1-scores achieved by the vulnerability detection (VD) method using different graph representations (CFG, PDG, CPG) on the source task S119 and its corresponding target tasks (Tm119 and Tsub). It demonstrates the impact of the choice of graph representation on the performance of the VD method across various modules (Fs, Drivers, Net, Include) and CWE subtypes (CWE-125, CWE-787). The CPG representation consistently outperforms CFG and PDG, highlighting its effectiveness in capturing comprehensive vulnerability information for improved VD performance.

read the caption

Table 10: F1-score (%) comparison of VD using different graph representations on S119 and its corresponding target tasks.

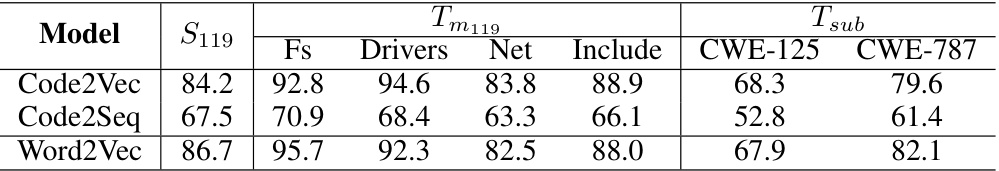

🔼 This table presents the results of vulnerability detection (VD) experiments using different embedding models: Code2Vec, Code2Seq, and Word2Vec. The F1-score, a metric combining precision and recall, is reported for the source task (S119) and several target tasks (Tm119 and Tsub). The target tasks represent different subsets of the Linux kernel (Fs, Drivers, Net, Include) and specific vulnerability subtypes (CWE-125, CWE-787). The table helps to assess the impact of different embedding models on the effectiveness of the KF-GVD approach in various scenarios.

read the caption

Table 11: F1-score (%) comparison of VD using different embedding models on S119 and its corresponding target tasks.

🔼 This table presents the results of cross-domain vulnerability detection experiments. Six different cross-domain tasks (L->F, L->O, F->L, F->O, O->L, O->F) were performed using seven different vulnerability detection methods. The F1-score, a metric that balances precision and recall, is used to evaluate the performance of each method on each task. The results show the relative effectiveness of the different methods across various domains.

read the caption

Table 12: F1-score (%) comparison of VD on cross-domain tasks.

Full paper#