↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Models (LLMs) often exhibit a performance gap between English and other languages, particularly those with limited resources. Existing methods either retrain LLMs for each language or rely on translation, often underutilizing LLMs’ inherent reasoning and language understanding capabilities. This leads to suboptimal performance and high computational costs.

MindMerger, a novel method, directly addresses these issues. It merges LLMs with external multilingual language understanding models using a two-stage training scheme to integrate external capabilities without modifying the core LLM parameters. Experiments show that MindMerger significantly outperforms existing methods across diverse multilingual datasets, achieving notable improvements in both high- and low-resource languages. This approach demonstrates a new paradigm for leveraging existing multilingual resources to enhance LLM performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on multilingual large language models (LLMs) and cross-lingual reasoning. It offers a novel method to significantly improve LLM reasoning capabilities in non-English languages, particularly low-resource ones, without requiring extensive parameter updates. This addresses a critical limitation in current LLM research and opens up new avenues for enhancing multilingual understanding and reasoning across diverse languages. The proposed method is also computationally efficient, making it practical for real-world applications.

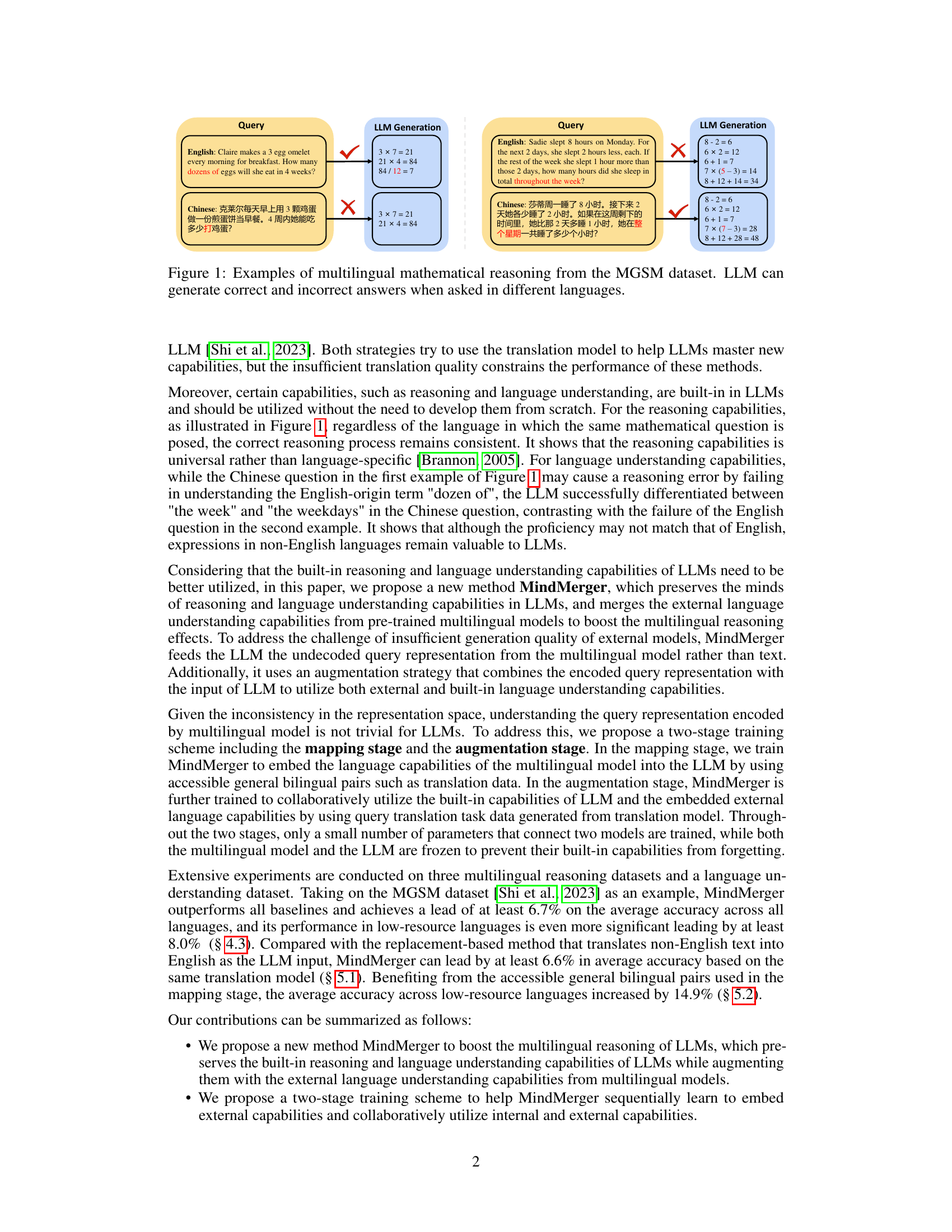

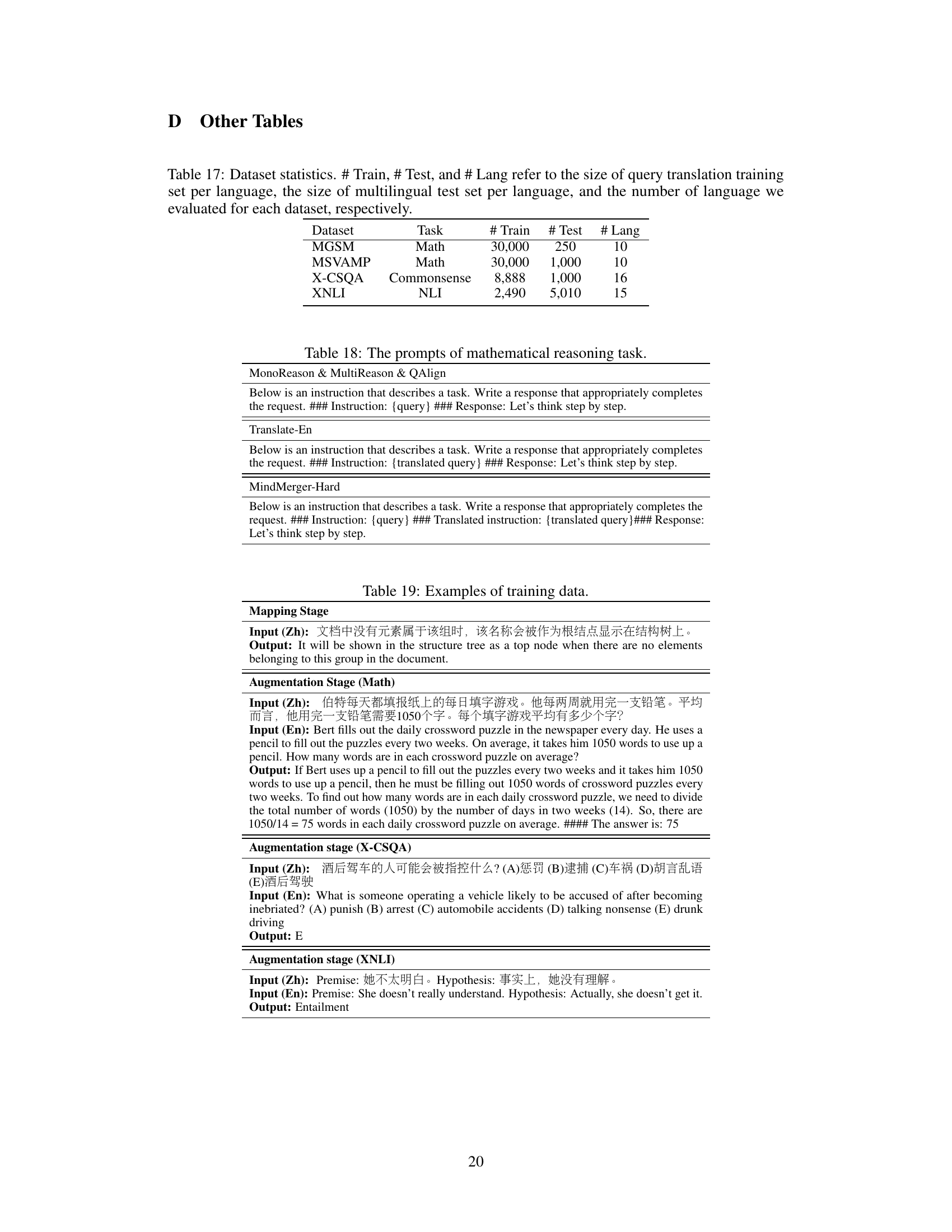

Visual Insights#

This figure shows two examples of math word problems, one in English and one in Chinese, and how a large language model (LLM) attempted to solve them. The examples highlight the challenges of multilingual reasoning for LLMs. In both cases, the LLM correctly understands and solves the English version, but its performance varies greatly with the Chinese version. In the first problem, the LLM correctly calculates the answer. However, in the second problem, the LLM fails to fully grasp the logic of the Chinese version, resulting in an incorrect answer. This illustrates the significant discrepancy in the LLM’s ability to handle reasoning tasks in different languages.

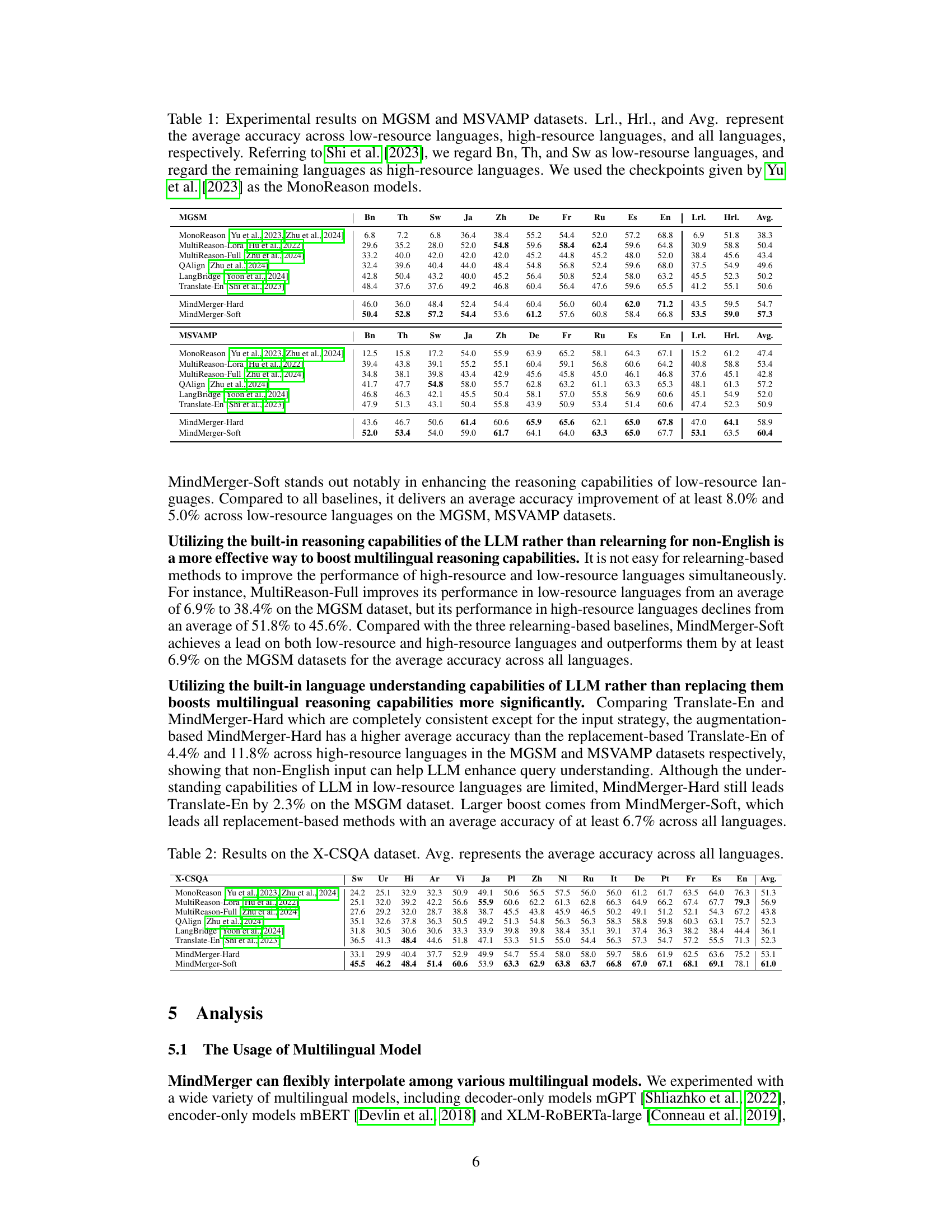

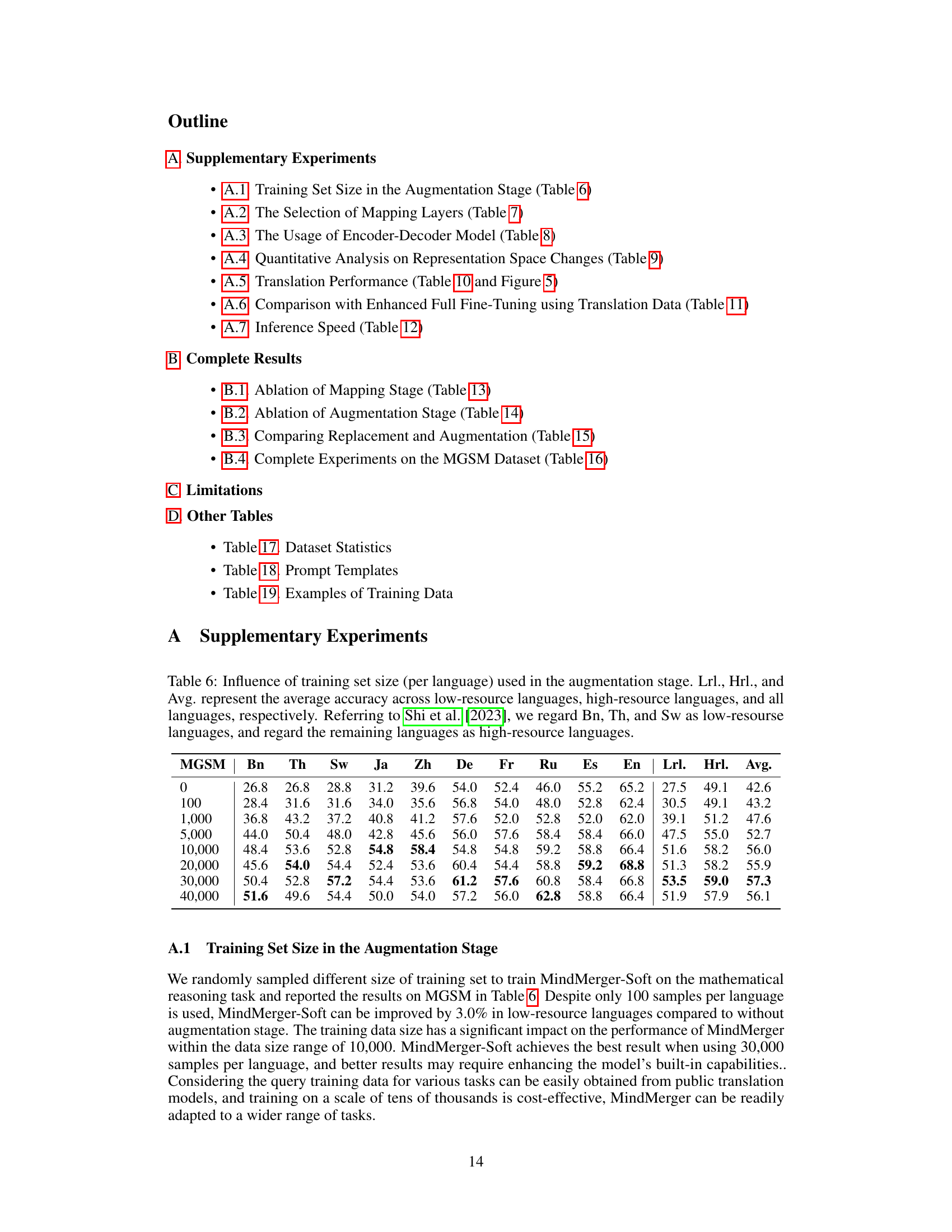

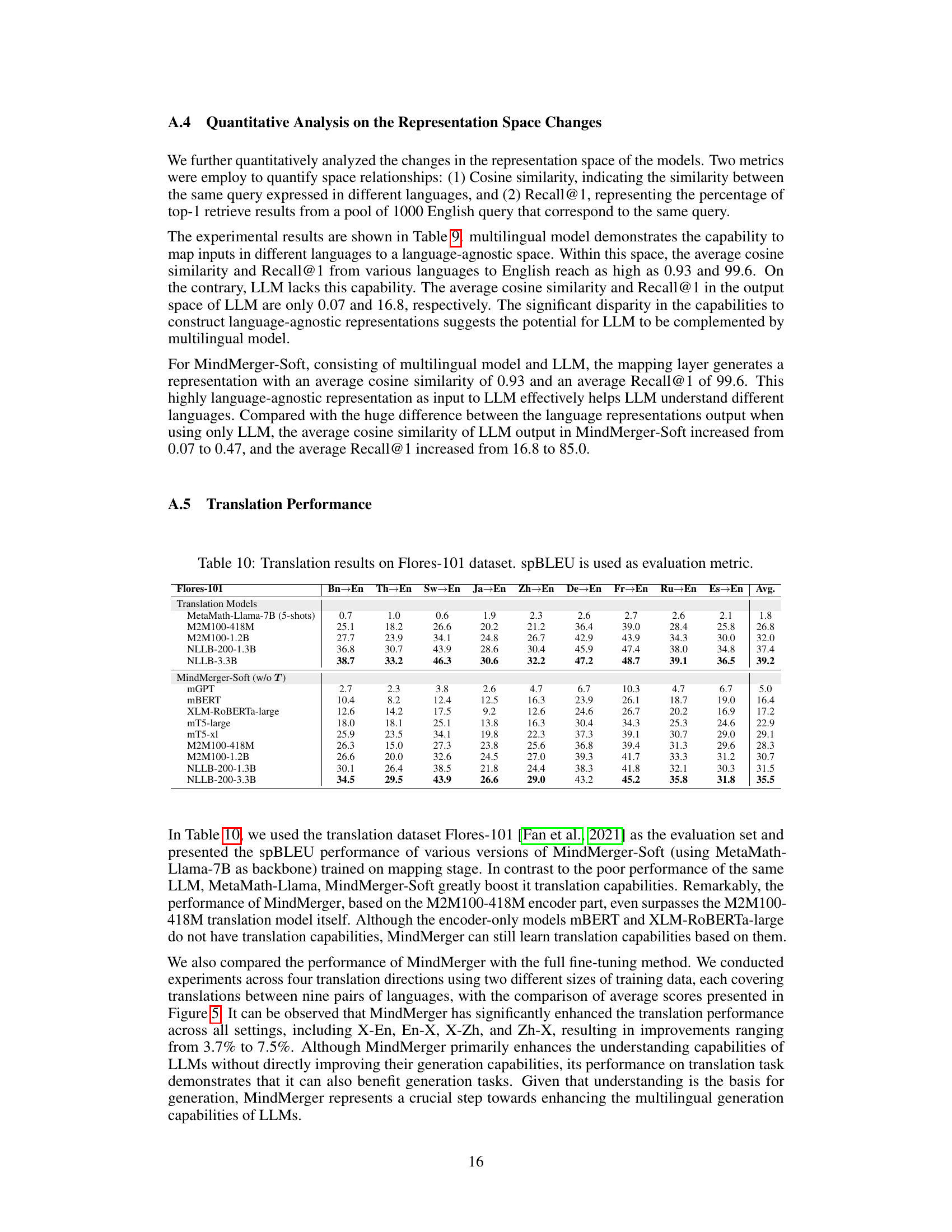

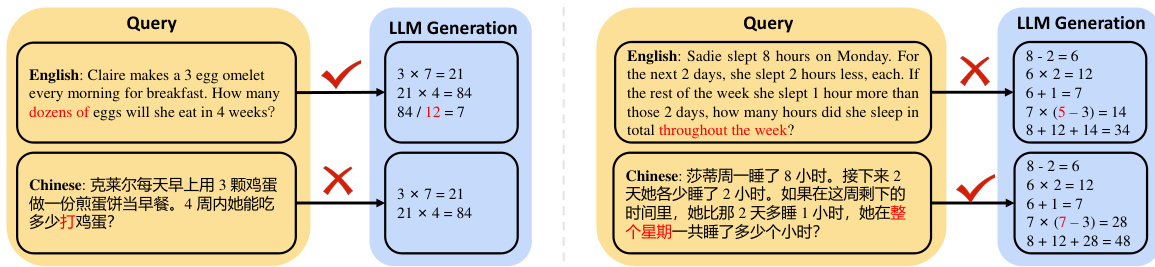

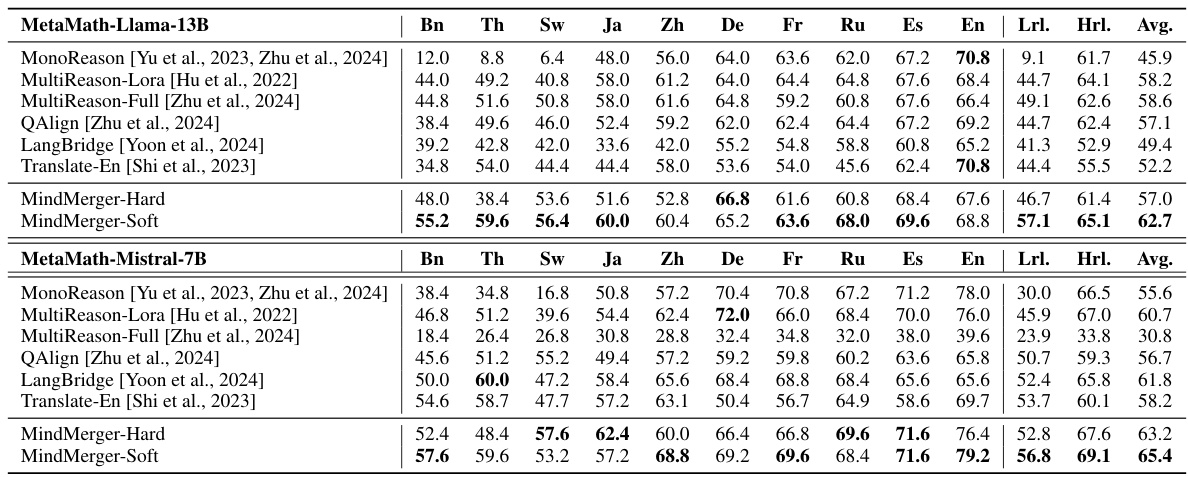

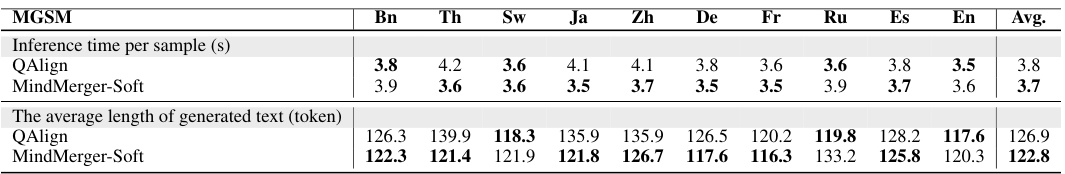

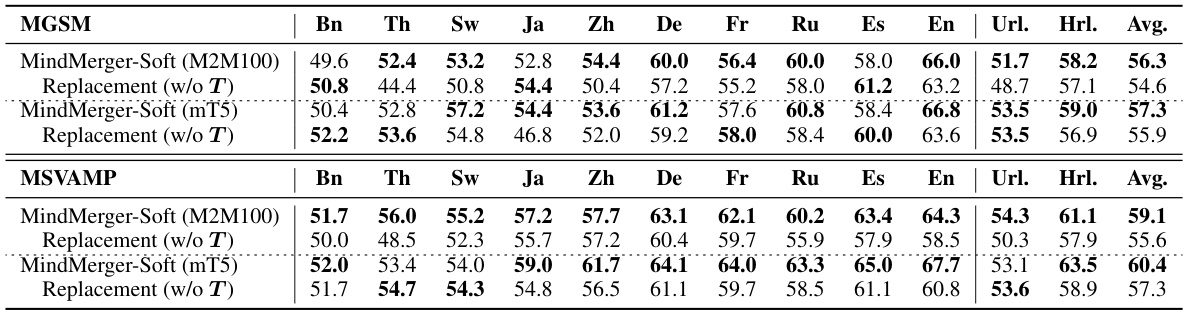

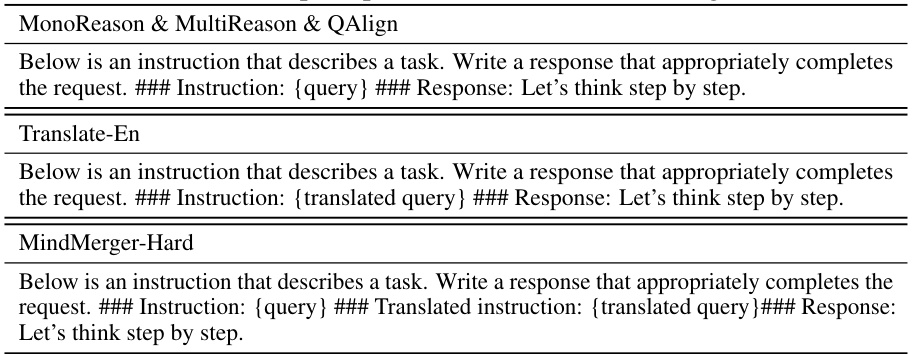

This table presents the experimental results of various multilingual reasoning models on two benchmark datasets: MGSM and MSVAMP. The results are broken down by language, distinguishing between low-resource and high-resource languages. The table compares the performance of MonoReason (a baseline), several relearning-based models (MultiReason-Lora, MultiReason-Full, QAlign), two replacement-based models (Translate-En, LangBridge), and the proposed MindMerger method (both hard and soft versions). The average accuracy across low-resource languages (Lrl.), high-resource languages (Hrl.), and all languages (Avg.) are reported to provide a comprehensive comparison.

In-depth insights#

LLM Reasoning Boost#

LLM reasoning capabilities, particularly in non-English languages, remain a significant challenge. Boosting these capabilities is crucial for broader LLM adoption and utility. Approaches focusing on fine-tuning or translation often underutilize the inherent reasoning abilities already present within LLMs. A more effective strategy might involve merging LLMs with external knowledge sources, such as multilingual models, to leverage existing language understanding skills and enhance reasoning without complete retraining. A two-stage training process, embedding external capabilities and then fostering collaborative use with internal LLM capabilities, offers a promising direction. This approach can significantly improve multilingual reasoning, especially for low-resource languages. The efficiency of this method, particularly in reducing parameter updates and maintaining the integrity of pre-trained models, highlights its practical advantages over complete fine-tuning.

MindMerger’s Approach#

MindMerger’s approach ingeniously tackles the challenge of boosting Large Language Model (LLM) reasoning in non-English languages. Instead of retraining LLMs from scratch or solely relying on translation, it leverages the inherent reasoning and language understanding capabilities already present within LLMs. This is achieved by merging LLMs with external multilingual models, specifically using a two-stage training process. The first stage, mapping, embeds the external language understanding capabilities into the LLM’s space. The second stage, augmentation, trains collaborative utilization of these capabilities alongside the LLM’s built-in abilities. This two-pronged strategy efficiently enhances multilingual reasoning without significant parameter updates, yielding notable performance gains, particularly in low-resource languages. The use of undecoded query representation from the external model further mitigates translation quality issues. MindMerger’s innovative merging strategy and two-stage training provide a powerful and efficient method for improving LLM reasoning across languages.

Multilingual Merging#

Multilingual merging in large language models (LLMs) aims to enhance the multilingual reasoning capabilities of these models by integrating external multilingual resources. This approach addresses the performance gap between English and other languages in LLMs, which often underutilize built-in reasoning skills. Instead of retraining or replacing non-English inputs, multilingual merging leverages existing language understanding features from multilingual models. This is achieved by merging the LLM with external capabilities, preserving the LLM’s inherent strengths. The effectiveness of this merging hinges on careful training strategies that integrate external resources without disrupting the LLM’s internal knowledge. A key challenge lies in harmonizing representation spaces between the external model and the LLM to ensure seamless collaboration. Successful multilingual merging offers a parameter-efficient method to boost multilingual performance, especially in low-resource languages, by focusing on enhancing existing capabilities rather than extensive retraining.

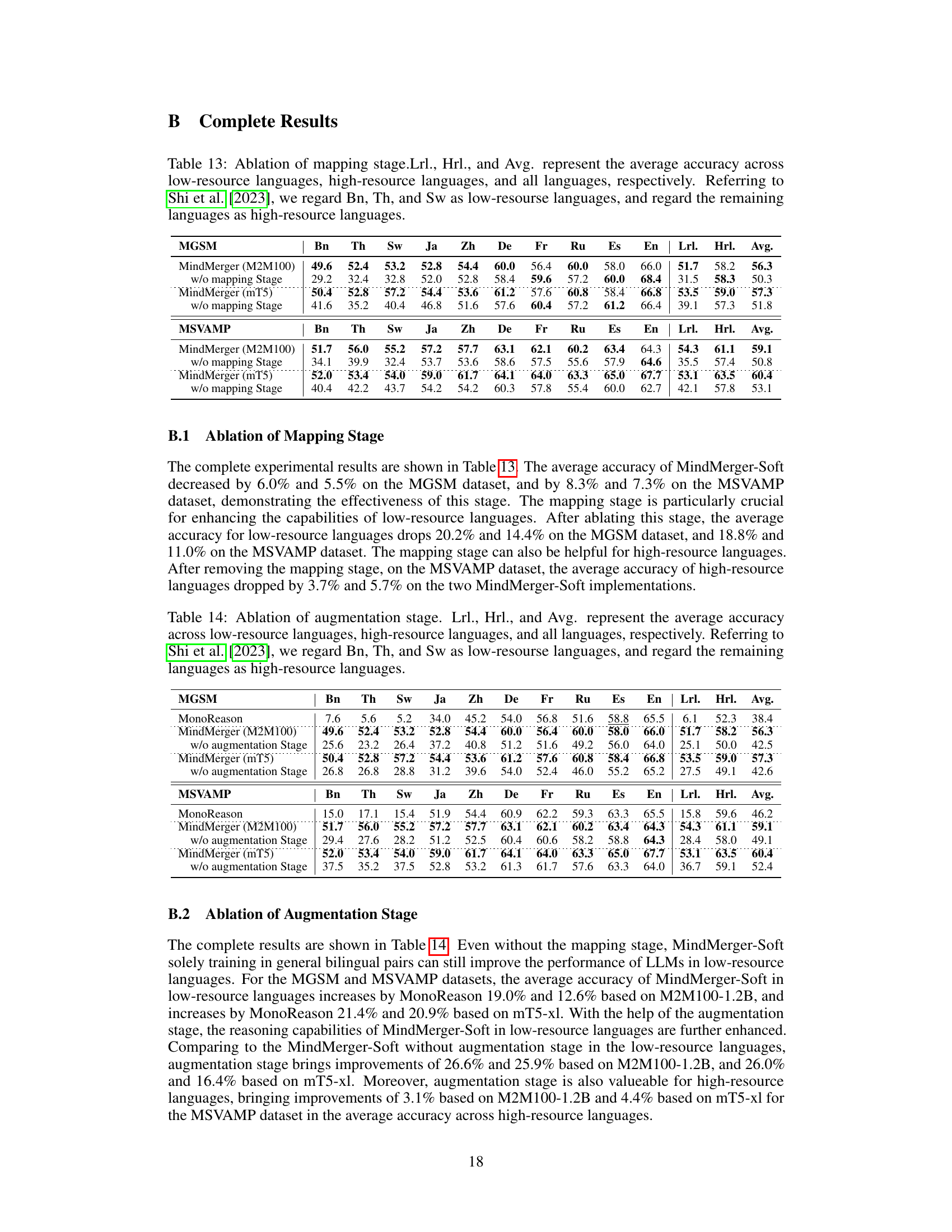

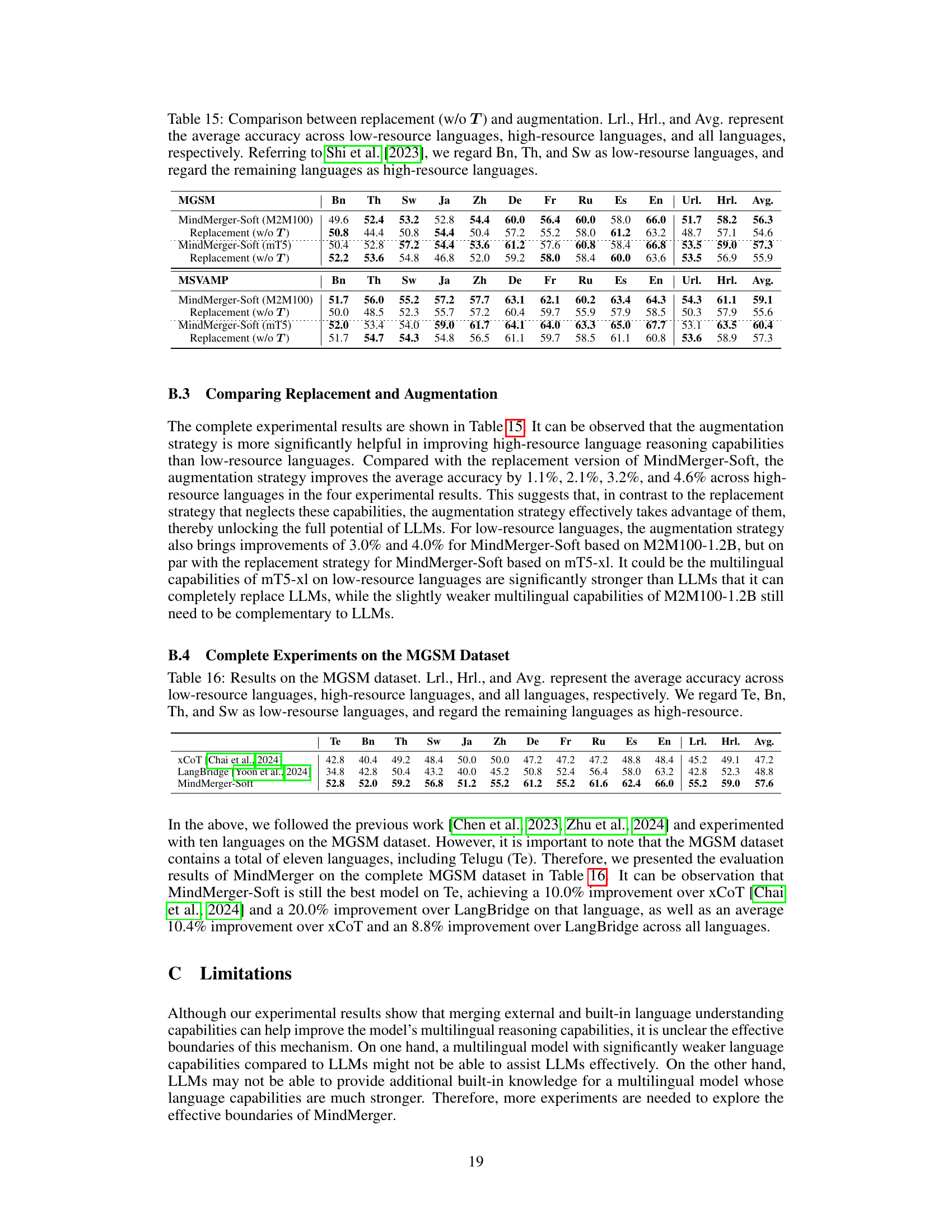

Ablation Study Insights#

Ablation studies systematically remove components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In this context, an ablation study would likely assess the impact of each module in the proposed MindMerger architecture. Removing the mapping layer might reveal whether the model can effectively integrate external multilingual capabilities without this intermediate transformation. Removing the augmentation stage would show whether the collaborative utilization of internal and external LLM capabilities is crucial for performance gains, specifically in low-resource languages. By analyzing the performance changes after each ablation, researchers can pinpoint crucial components, highlighting the relative importance of different modules. This offers insights into the design and effectiveness of the architecture and can inform future improvements or modifications. The results might demonstrate the necessity of both the mapping and augmentation stages for optimal multilingual reasoning, especially in cases where LLM internal capabilities are limited.

Future Enhancements#

Future enhancements for multilingual LLM reasoning could involve exploring more sophisticated model merging techniques, such as attention-based mechanisms that dynamically adjust the contribution of external and internal LLM capabilities. Investigating different architectural designs beyond simple concatenation, perhaps integrating the external model’s features more deeply within the LLM architecture itself, warrants further exploration. Additionally, research into finer-grained control over the merging process would allow for more targeted improvements for specific language families or task types. Addressing limitations in low-resource languages remains crucial, potentially through techniques like data augmentation, cross-lingual transfer learning, or meta-learning approaches. Finally, evaluating the robustness of MindMerger to adversarial attacks and exploring methods to improve its interpretability and explainability would significantly enhance its reliability and trustworthiness.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the architecture and training process of the MindMerger model. The model structure shows how a Large Language Model (LLM) is combined with an external multilingual encoder. The training scheme details the two-stage process: a mapping stage using general bilingual pairs to integrate the external model’s capabilities into the LLM, and an augmentation stage using query translation task data to collaboratively utilize both internal and external capabilities. The colors (blue and yellow) distinguish between the LLM and the external model, respectively.

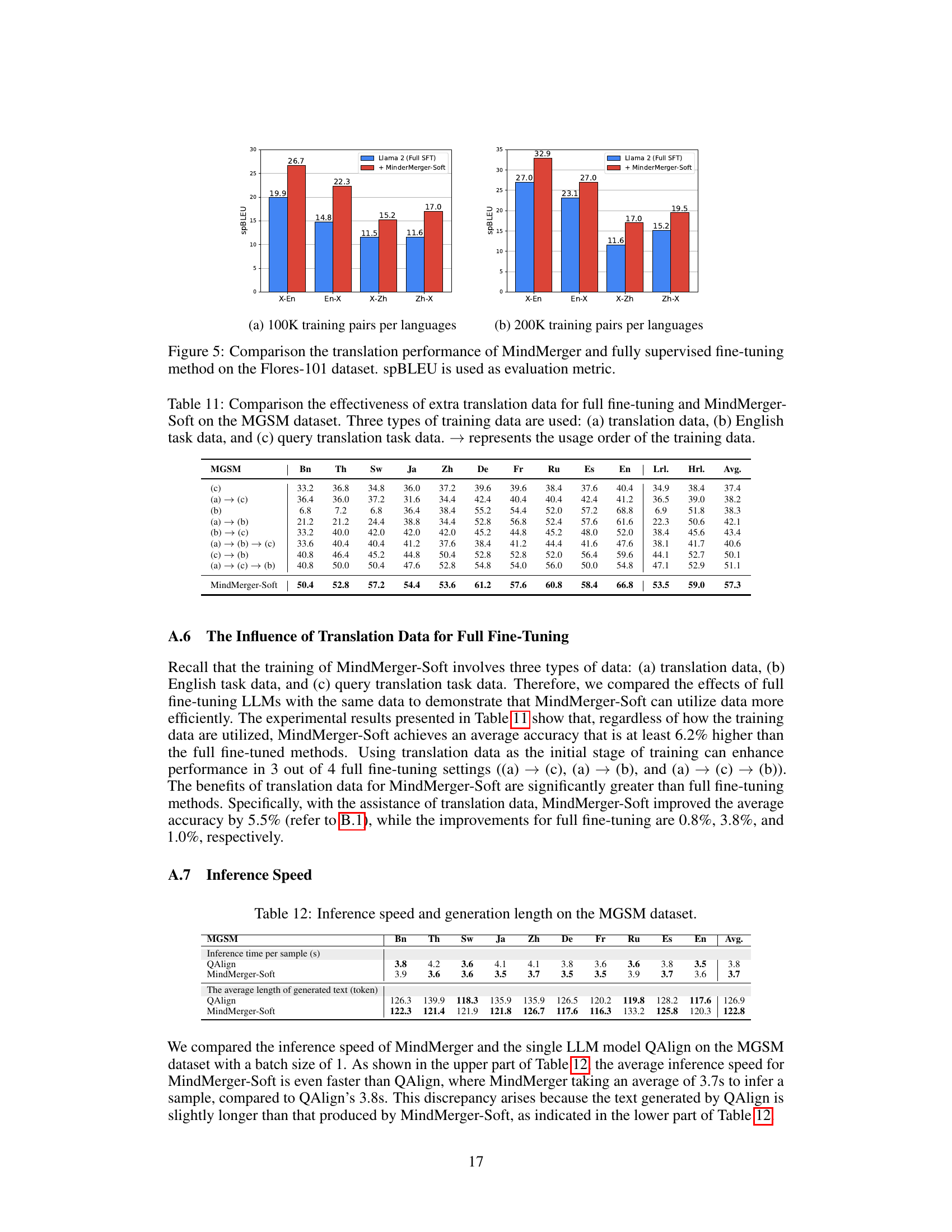

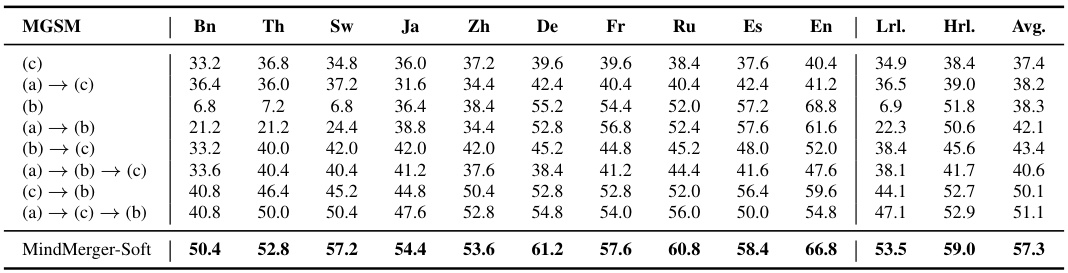

This figure presents the ablation study results for MindMerger-Soft on the MGSM dataset. It shows the impact of removing the mapping stage (a), the augmentation stage (b), and compares the replacement-based and augmentation-based strategies (c). The results are broken down by average accuracy across low-resource languages (Lrl.), high-resource languages (Hrl.), and all languages (Avg.). The figure demonstrates the importance of both the mapping and augmentation stages in achieving high performance, particularly for low-resource languages.

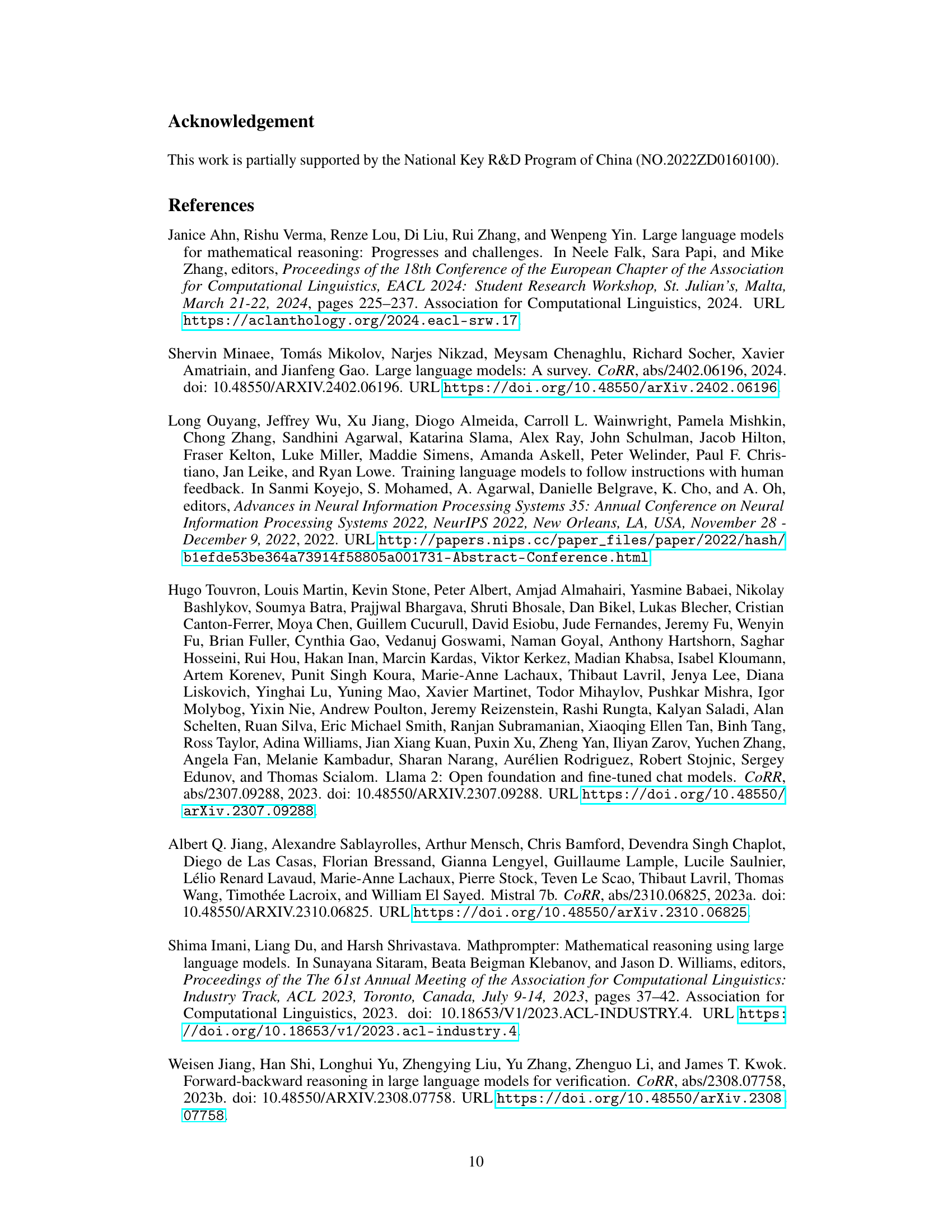

This figure visualizes the representation spaces of LLM embeddings and the outputs of the mapping layer using t-SNE. The left panel (a) shows the LLM embeddings, illustrating how the representations of different languages are mostly separate, especially low-resource languages, from English. In contrast, the right panel (b) shows the mapping layer outputs, where the representations of all languages are clustered together and near to English. This demonstrates how the mapping layer helps to bridge the representation gap between multilingual model and LLM, facilitating the effective utilization of both internal and external capabilities.

This figure shows the results of ablation studies conducted on the MindMerger-Soft model using the MGSM dataset. Three ablation experiments were performed: removing the mapping stage, removing the augmentation stage, and replacing the augmentation strategy with a replacement strategy. The results are presented in terms of average accuracy across low-resource, high-resource, and all languages. The figure demonstrates the importance of both the mapping and augmentation stages for achieving optimal performance, particularly in low-resource languages.

More on tables

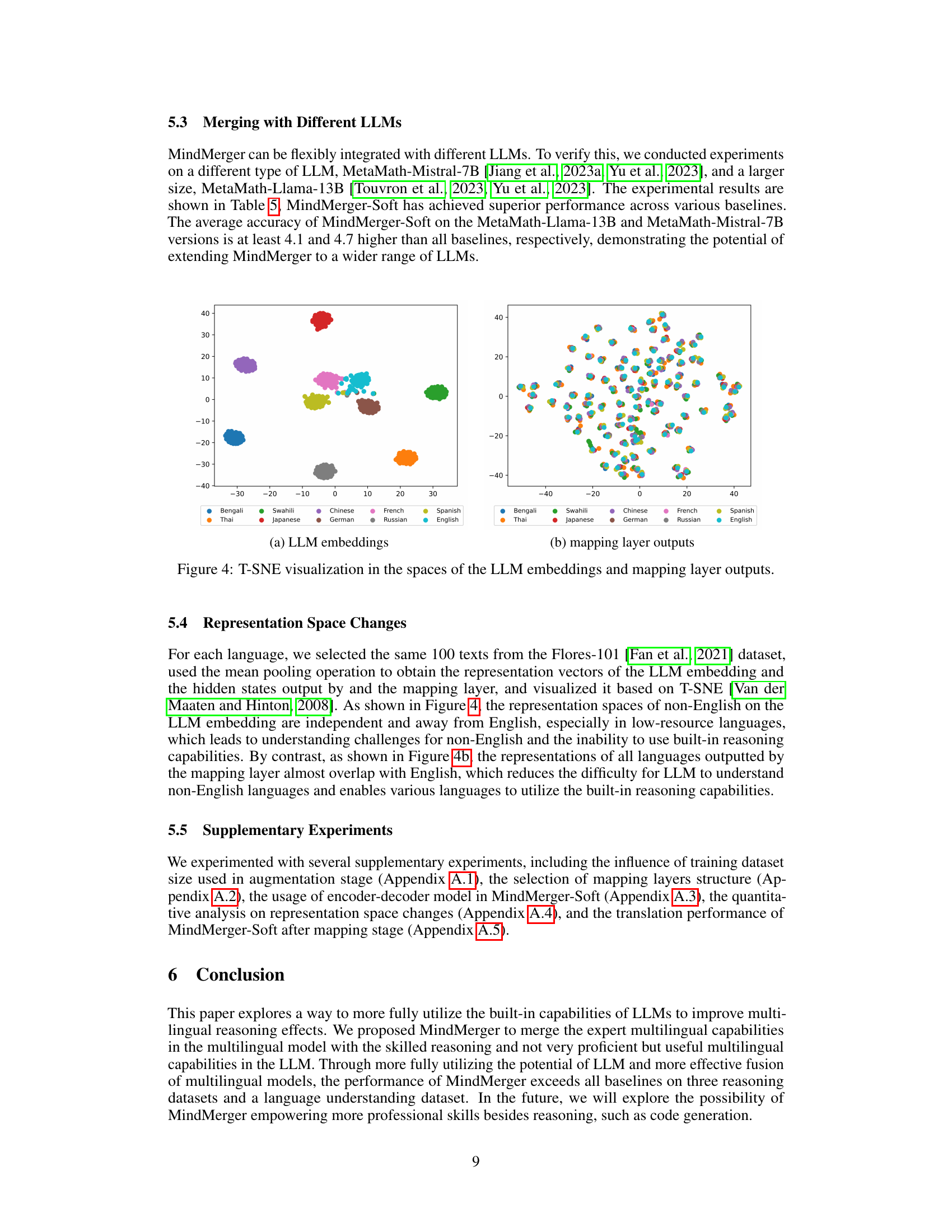

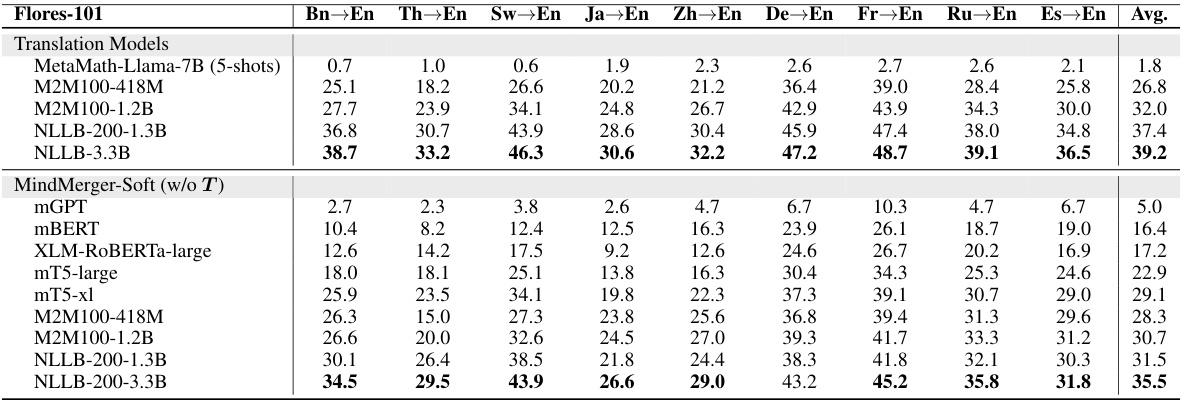

This table presents the results of the X-CSQA (Cross-lingual Commonsense Question Answering) dataset experiment. It shows the performance of various models across different languages, including low-resource languages. The ‘Avg.’ column represents the average accuracy across all languages tested. The table aims to demonstrate the multilingual reasoning capabilities of the models and their effectiveness in handling commonsense questions across various language backgrounds.

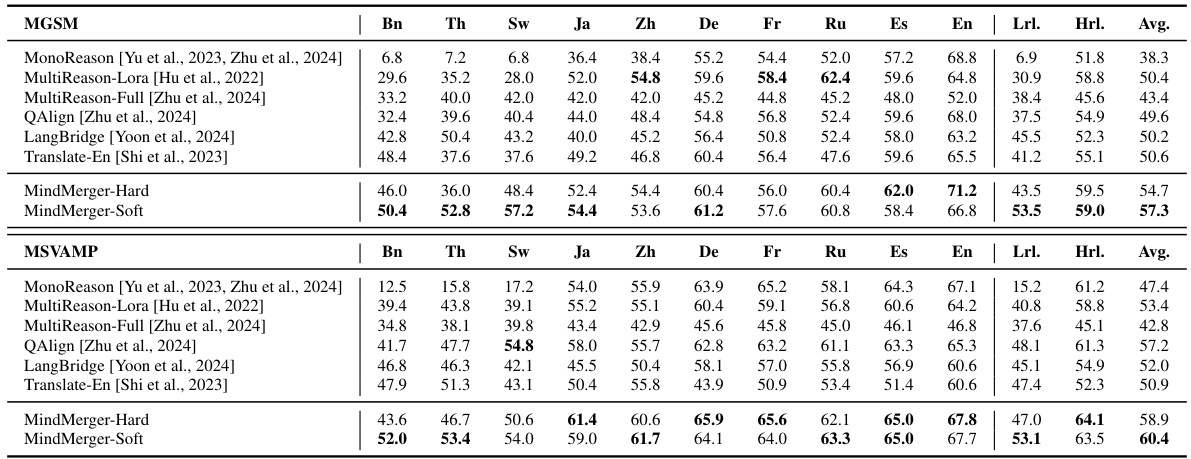

This table presents the experimental results of various multilingual reasoning models on the MGSM and MSVAMP datasets. The results are broken down by language, showing the average accuracy for low-resource languages, high-resource languages, and overall. It compares the performance of the proposed MindMerger method against several baseline models.

This table presents the experimental results of various multilingual reasoning models on the MGSM and MSVAMP datasets. It compares the performance of the proposed MindMerger models (MindMerger-Hard and MindMerger-Soft) against several baseline methods, including MonoReason, MultiReason-Lora, MultiReason-Full, QAlign, LangBridge, and Translate-En. The results are broken down by language, distinguishing between low-resource and high-resource languages, and overall average accuracy. The table highlights the improvements achieved by MindMerger, particularly in low-resource languages.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of various models on two multilingual mathematical reasoning datasets: MGSM and MSVAMP. The models compared include MonoReason (a baseline), several relearning-based methods (MultiReason-Lora, MultiReason-Full, QAlign), and two replacement-based methods (Translate-En, LangBridge). The table shows the average accuracy across all languages, as well as the average accuracy specifically for low-resource and high-resource languages. Low-resource languages are identified as Bengali (Bn), Thai (Th), and Swedish (Sw), while high-resource languages include Japanese, Chinese, German, French, Russian, Spanish, and English. The results highlight MindMerger’s superior performance, particularly in low-resource languages.

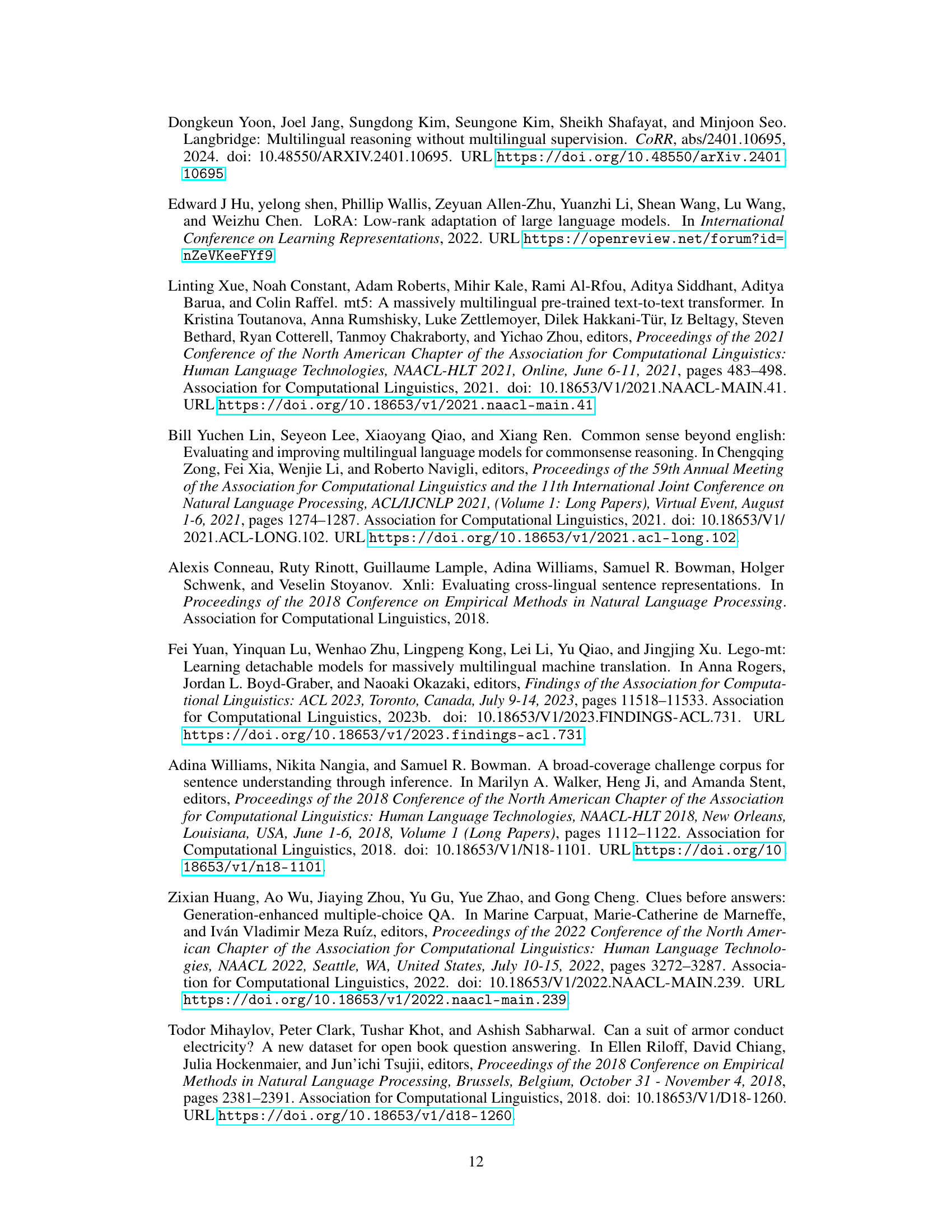

This table presents the results of an ablation study on the impact of different training set sizes used in the augmentation stage of the MindMerger model on the MGSM dataset. It shows how the average accuracy across low-resource languages (Lrl.), high-resource languages (Hrl.), and all languages (Avg.) changes with varying training set sizes. The results highlight the influence of data quantity on the model’s performance, particularly for low-resource languages.

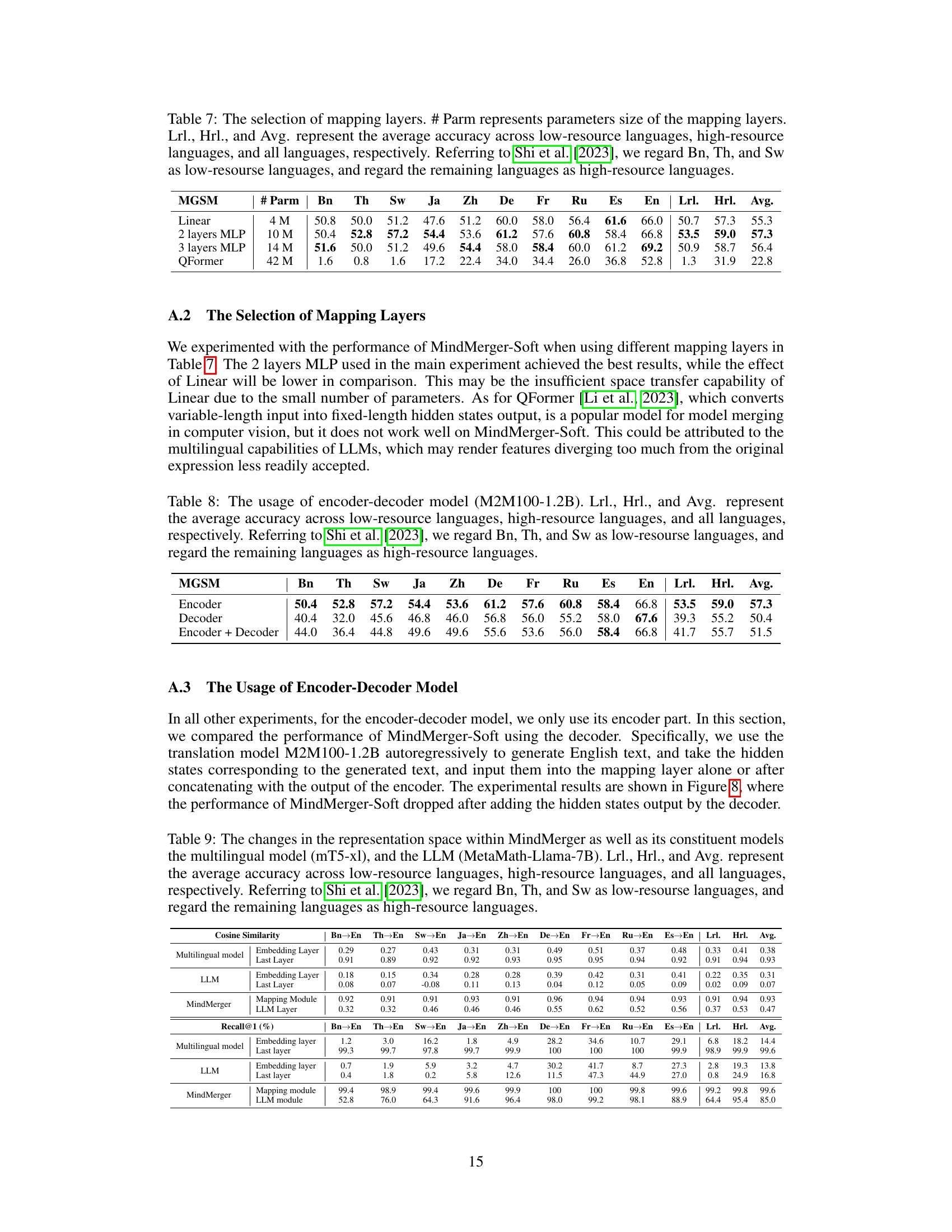

This table presents the results of experiments conducted to determine the optimal configuration of the mapping layers within the MindMerger model. Different mapping layer architectures (Linear, 2-layer MLP, 3-layer MLP, and QFormer) were compared, and their performance was evaluated across low-resource, high-resource, and all languages combined. The results demonstrate that a 2-layer MLP architecture yields the best performance in terms of average accuracy across all languages.

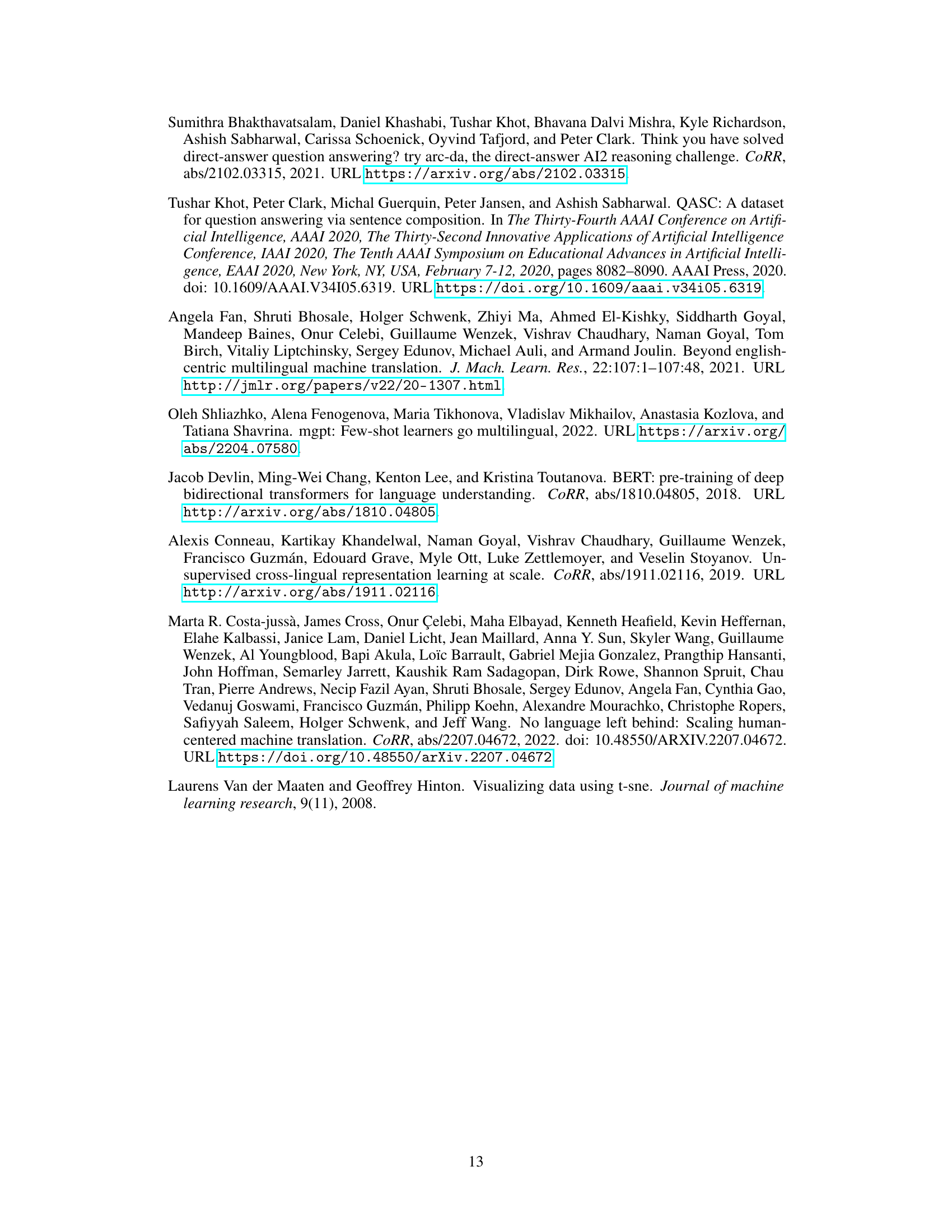

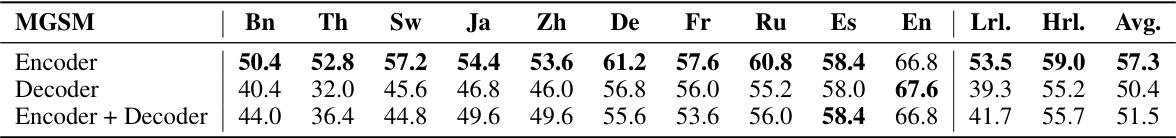

This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the performance of MindMerger-Soft using different components of the encoder-decoder model M2M100-1.2B. It compares the performance when using only the encoder, only the decoder, and both encoder and decoder components. The results are broken down by language group (low-resource and high-resource) and overall, showing the impact of each model component on multilingual reasoning accuracy.

This table presents the experimental results of various multilingual reasoning methods on the MGSM and MSVAMP datasets. It compares the performance of MindMerger against several baseline methods, broken down by language (including low-resource languages like Bengali, Thai, and Swahili, and high-resource languages such as English, French, and German). The results show the average accuracy for each language and across all languages, highlighting MindMerger’s improvements, especially in low-resource scenarios.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of various multilingual reasoning models on two datasets: MGSM and MSVAMP. The models are categorized into several types: MonoReason (a baseline), relearning-based methods (MultiReason-Lora, MultiReason-Full, QAlign), and replacement-based methods (Translate-En, LangBridge). The table shows the average accuracy across all languages, as well as broken down by low-resource and high-resource languages. The low-resource languages are identified as Bengali (Bn), Thai (Th), and Swahili (Sw). The results demonstrate the comparative performance of MindMerger against established methods.

This table presents the experimental results of various multilingual reasoning models on two datasets: MGSM and MSVAMP. It compares the performance of MindMerger against several baseline models. The results are broken down by language, differentiating between low-resource and high-resource languages, and showing average accuracy across all languages. The table helps demonstrate MindMerger’s improved performance, especially in low-resource languages.

This table presents the experimental results of various multilingual reasoning models on two datasets: MGSM and MSVAMP. The results are broken down by language, distinguishing between low-resource and high-resource languages. The table compares the performance of MindMerger (in two variants) against several baseline models, showing accuracy scores for each language and averaged across low-resource, high-resource, and all languages. The MonoReason model checkpoints are from Yu et al. (2023).

This table presents the experimental results of MindMerger and its baselines on two multilingual mathematical reasoning datasets: MGSM and MSVAMP. The results are broken down by language, distinguishing between low-resource and high-resource languages. The table shows the average accuracy for each model on each dataset and language group, allowing for a comparison of the performance of MindMerger against various methods, and highlights performance differences between resource levels for each language.

This table presents the experimental results of different multilingual reasoning models on the MGSM and MSVAMP datasets. It compares the performance of MindMerger (with two variants and using two different multilingual encoders) against several baseline methods. The results are broken down by language (showing low-resource languages separately), highlighting the improvements achieved by MindMerger, particularly in low-resource settings. MonoReason models from Yu et al. (2023) serve as a baseline for comparison.

This table presents the experimental results of several multilingual reasoning models on the MGSM and MSVAMP datasets. It compares the performance of MindMerger (in two variants) against several baseline methods. The results are broken down by language, distinguishing between low-resource and high-resource languages, and showing average accuracy across all languages. The baseline models include MonoReason, MultiReason-Lora, MultiReason-Full, QAlign, LangBridge, and Translate-En. This allows for a comprehensive comparison of the proposed MindMerger approach against existing state-of-the-art methods in multilingual reasoning.

This table presents the results of the MGSM dataset experiment, comparing the performance of MindMerger-Soft against other methods. It shows the average accuracy for low-resource (Lrl), high-resource (Hrl), and all languages (Avg). The low-resource languages specified are Telugu, Bengali, Thai, and Swahili.

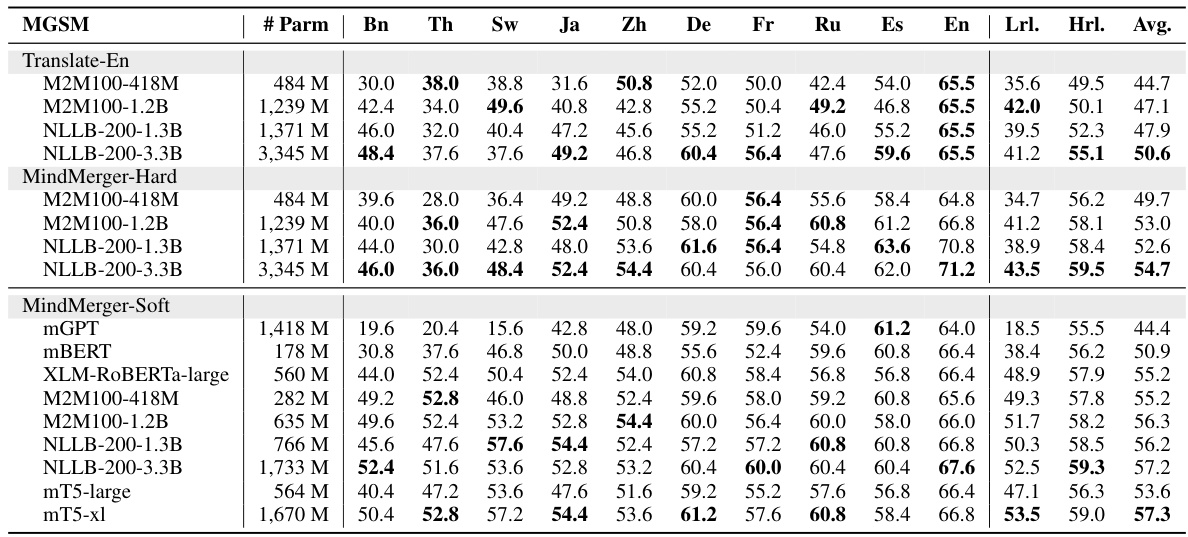

This table presents the statistics of the four datasets used in the paper’s experiments. For each dataset, it shows the number of training examples per language (# Train), the number of test examples per language (# Test), and the total number of languages included (# Lang). The datasets cover three different tasks: mathematical reasoning (MGSM and MSVAMP), commonsense reasoning (X-CSQA), and natural language inference (XNLI).

This table presents the experimental results of various multilingual reasoning models on two datasets: MGSM and MSVAMP. The results are broken down by language, distinguishing between low-resource and high-resource languages. The table compares the performance of MindMerger (in two variants) against several baseline models, showing the average accuracy for each language and across different language categories. The MonoReason model’s checkpoints from Yu et al. (2023) were used as a baseline.

This table presents the experimental results of different multilingual reasoning models on two datasets: MGSM and MSVAMP. It compares the average accuracy of several models (MonoReason, MultiReason-Lora, MultiReason-Full, QAlign, LangBridge, Translate-En, MindMerger-Hard, and MindMerger-Soft) across various languages, distinguishing between low-resource and high-resource languages. The results showcase the performance improvements achieved by MindMerger compared to the baselines, particularly for low-resource languages.

Full paper#