↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current text-to-video generation methods struggle with precise control over individual concepts. This limits their ability to create complex, high-fidelity videos with nuanced motion and varied viewpoints. The lack of explicit 3D representation further hampers the ability to easily manipulate and control individual elements within the video.

This paper introduces C3V, a novel framework that leverages Large Language Models (LLMs) to decompose complex text prompts into individual concepts (e.g., scene, objects, motion). Each concept is generated as a separate 3D representation before being composed using additional priors from LLMs and 2D diffusion models. This allows for fine-grained control over each concept’s appearance, movement, and position within the final video. The use of Score Distillation Sampling refines the 2D output to achieve natural image distribution and high visual quality. The experiments show that C3V outperforms existing methods in generating high-fidelity videos from text with diverse motion and flexible control over individual concepts.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel paradigm for text-to-video generation, addressing the challenge of precisely controlling individual concepts within the generated video. It introduces a compositional approach using 3D representations and large language models, which offers flexible control over each concept and opens up new avenues for research in video generation, particularly for high-fidelity videos with diverse motion and flexible control. The improved ability to generate and manipulate such videos can significantly impact various applications, from filmmaking and animation to virtual and augmented reality.

Visual Insights#

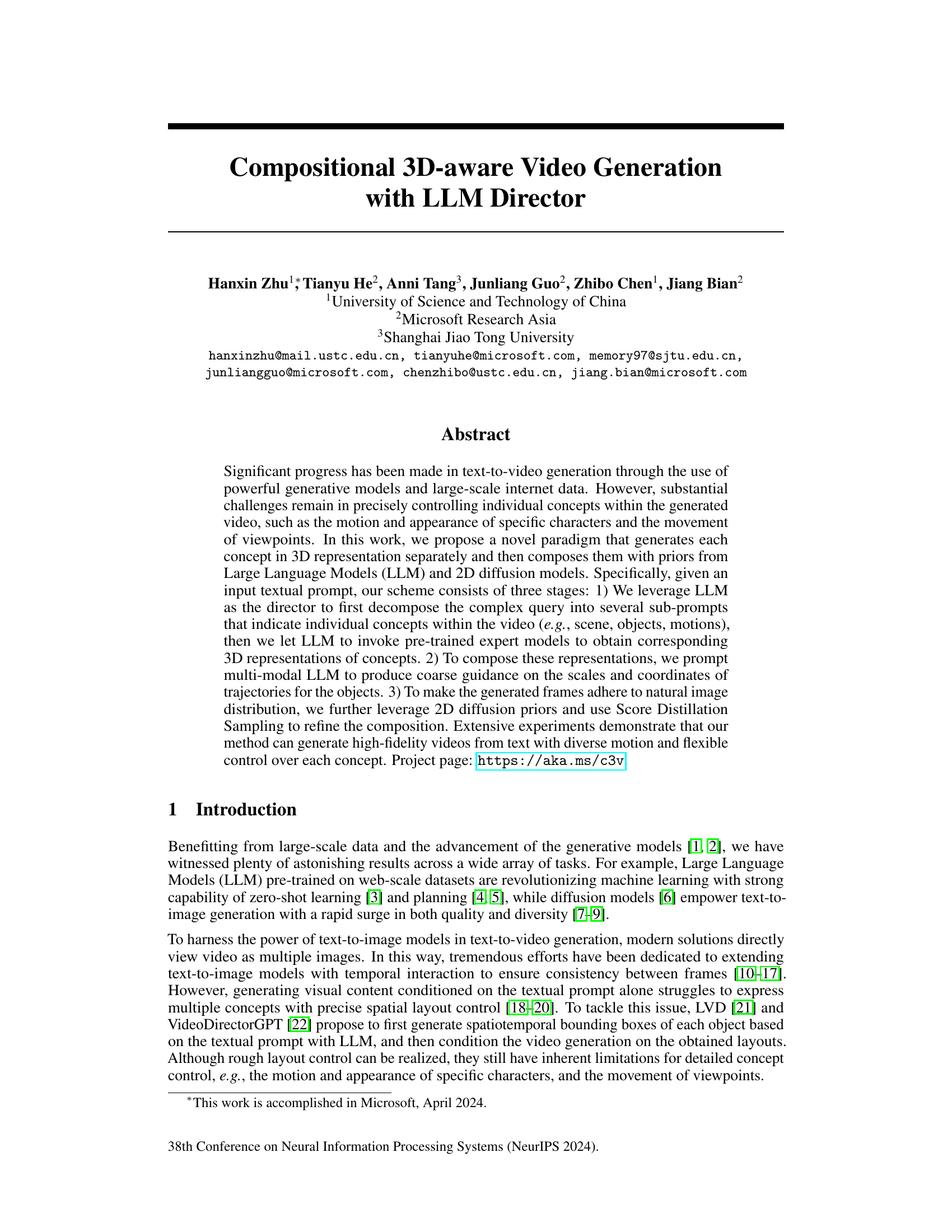

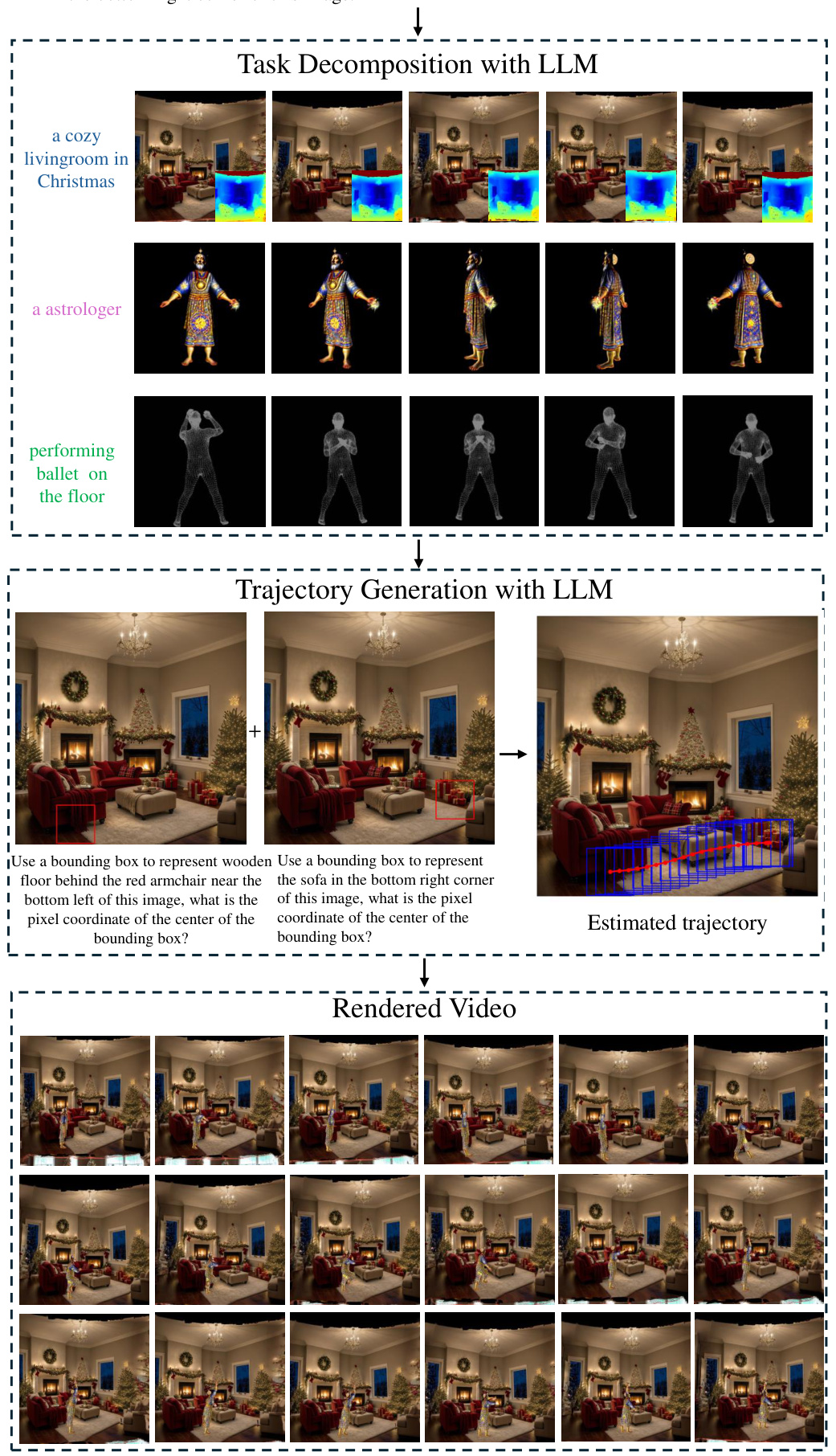

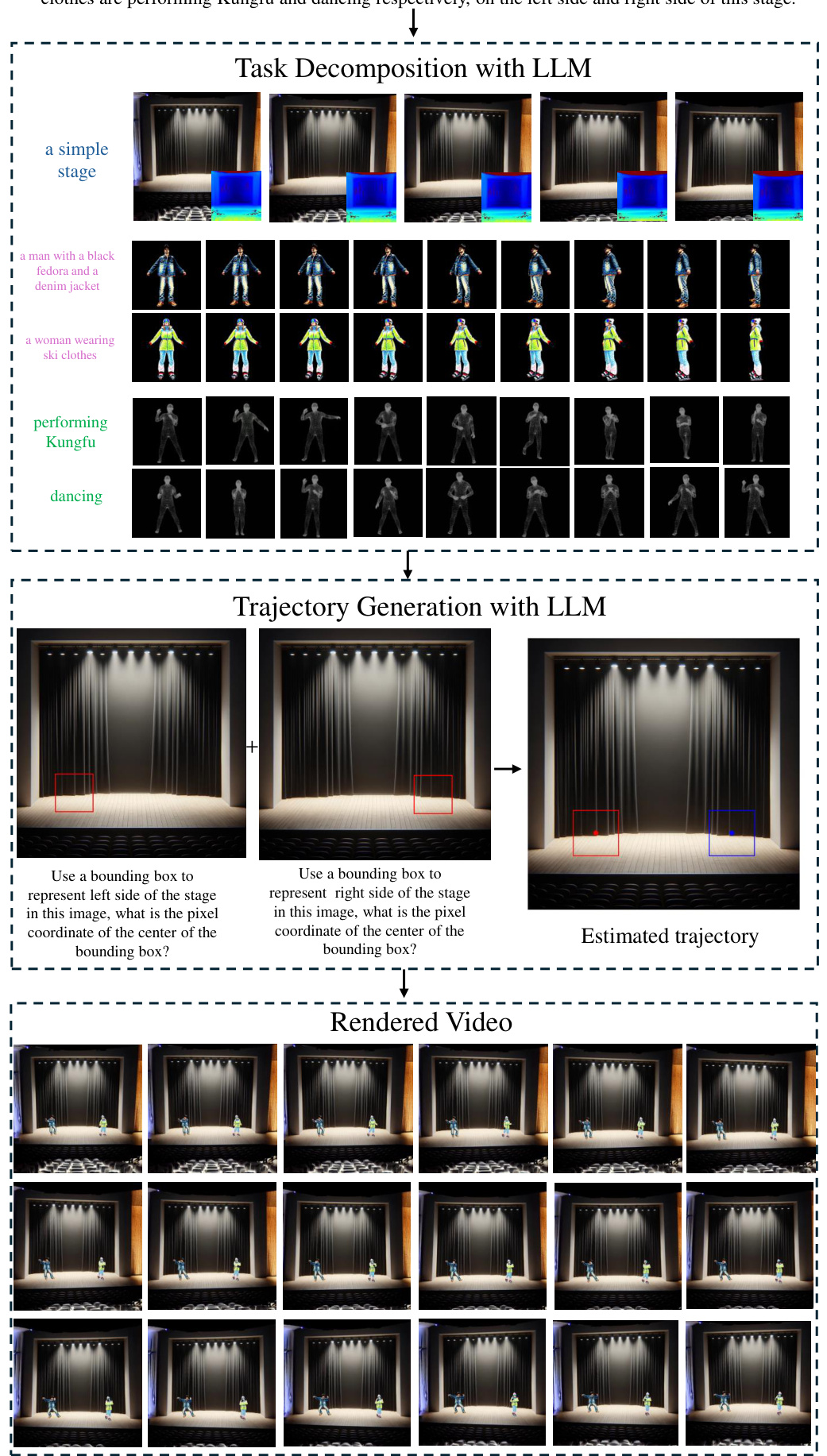

This figure illustrates the three-stage process of the proposed method (C3V). Stage 1 involves decomposing a complex textual prompt into individual concepts (scene, objects, motion) using an LLM and generating their 3D representations using pre-trained expert models. Stage 2 utilizes a multi-modal LLM to estimate the 2D trajectories of objects step-by-step. Finally, Stage 3 refines the 3D object scales, locations, and rotations by lifting the 2D trajectories into 3D and using 2D diffusion priors with score distillation sampling.

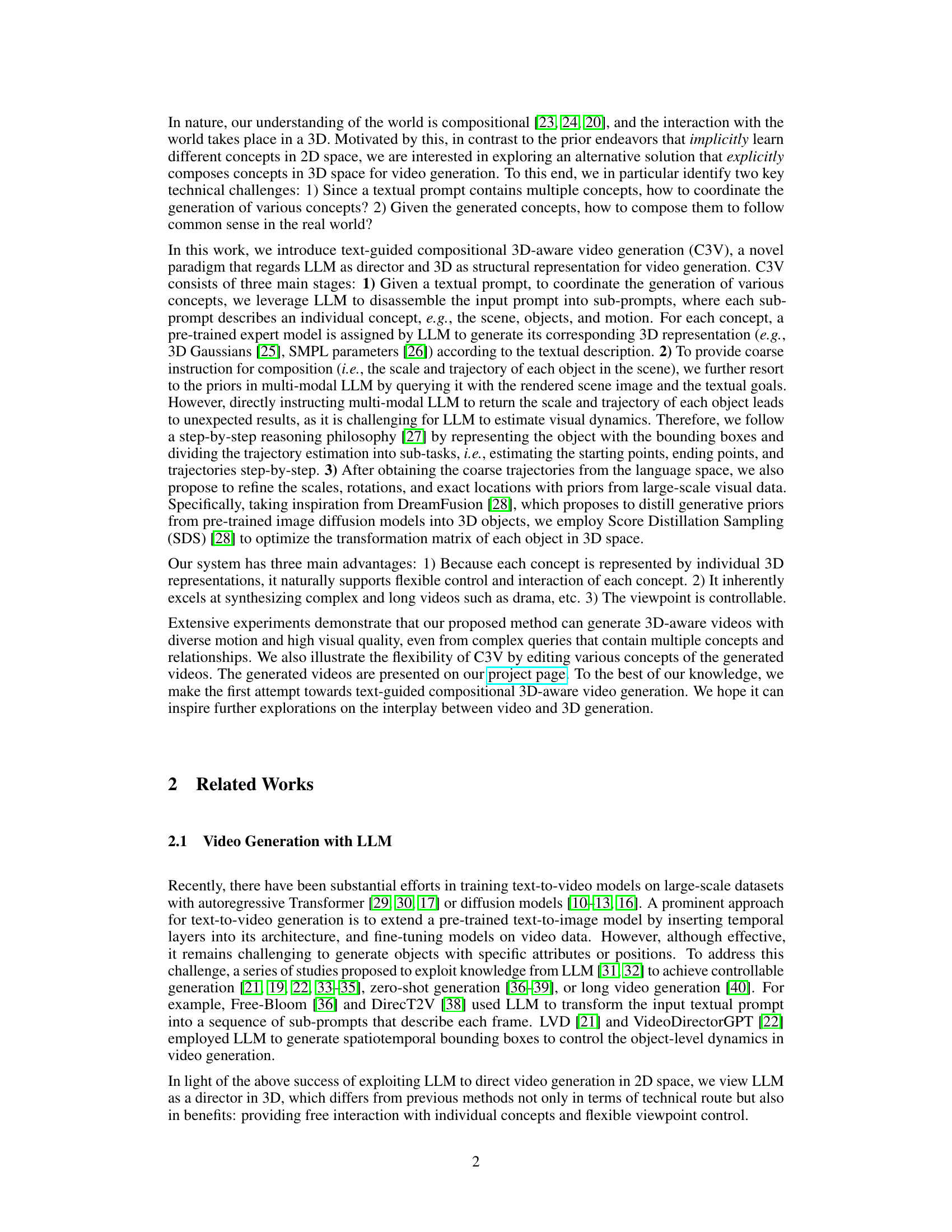

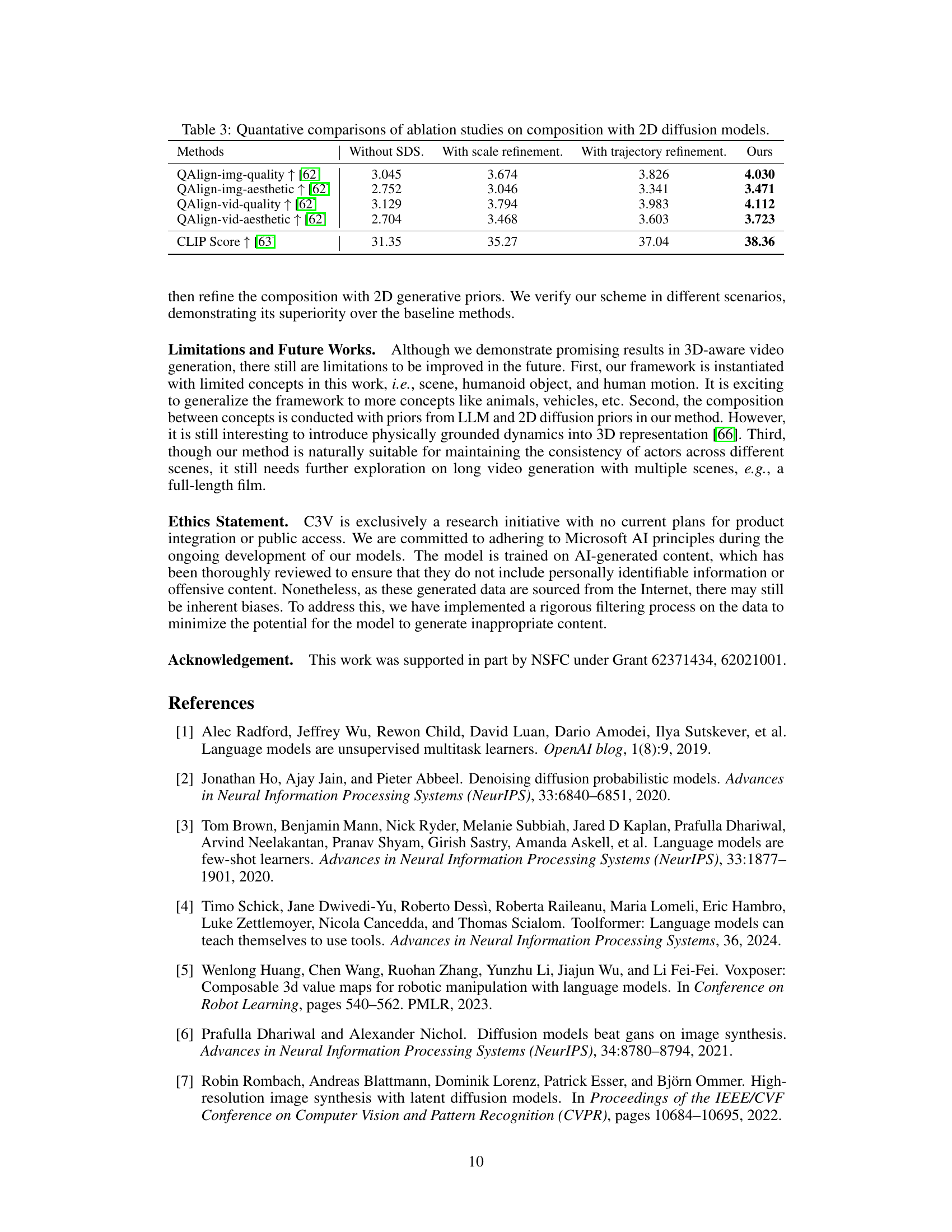

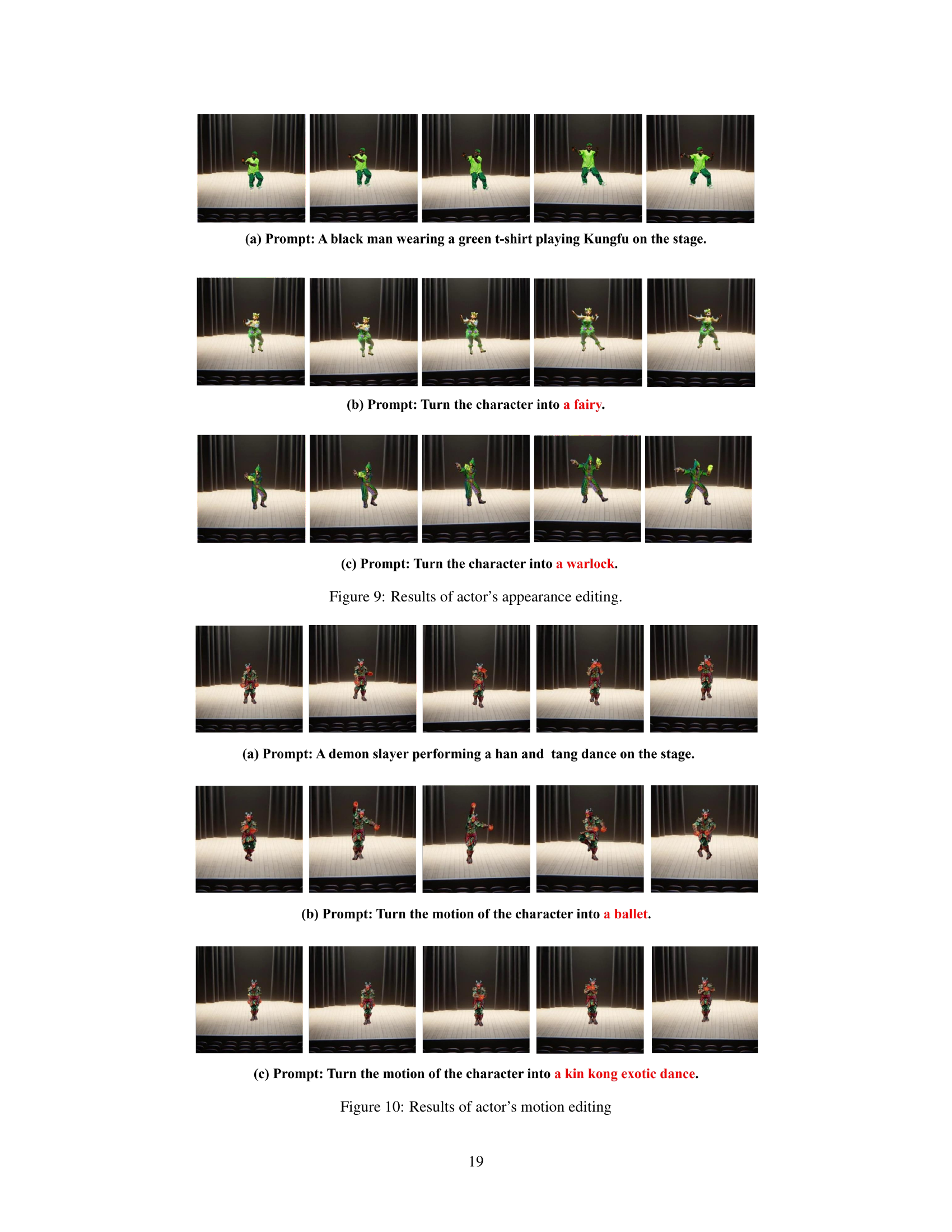

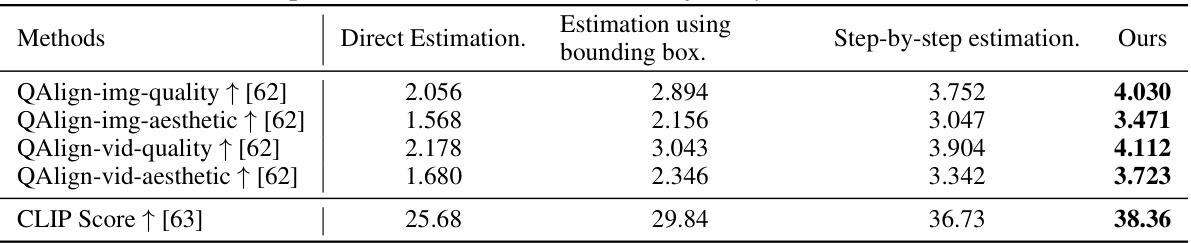

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed method against three state-of-the-art baselines: 4D-FY [58], Comp4D [51], and VideoCrafter2 [59]. The metrics used for comparison include QAlign scores (img-quality, img-aesthetic, vid-quality, vid-aesthetic), which measure the visual quality and aesthetics of both images and videos, and CLIP score, which assesses the alignment between the generated content and textual prompts. Higher scores indicate better performance. The results demonstrate the superiority of the proposed method in terms of both visual quality and alignment with the text prompts.

In-depth insights#

LLM-driven 3D Video#

LLM-driven 3D video generation represents a significant advancement in AI-driven content creation. This approach leverages the power of Large Language Models (LLMs) to understand and interpret complex textual descriptions, translating them into intricate 3D video scenes. The key advantage lies in the ability to control various aspects of the video with nuanced textual prompts, moving beyond simple image generation to encompass dynamic scenes with interactive elements. This opens avenues for high-fidelity, detailed videos that were previously unattainable with traditional methods. However, challenges remain. Precise control over individual objects’ motion and interactions within the 3D environment is still an area for improvement. Additionally, the computational cost of generating and rendering high-resolution 3D videos remains considerable, demanding significant processing power and resources. Addressing these limitations—through enhanced LLM architectures and optimization techniques—is crucial for wider adoption and practical application of this technology. Ultimately, LLM-driven 3D video has the potential to revolutionize filmmaking, animation, and interactive experiences, providing unprecedented creative control and efficiency.

Compositional Approach#

A compositional approach to 3D-aware video generation, as described in the research paper, centers on decomposing complex video concepts into smaller, manageable sub-components. This allows for the independent generation of individual elements like scene, objects, and motion using specialized 3D models. A key advantage is the enhanced controllability afforded by this method. Each component’s properties can be fine-tuned, offering flexibility not usually available in methods that generate videos holistically. The framework often employs a large language model (LLM) to orchestrate the process, guiding the decomposition and directing how these individual components are assembled. This LLM acts as a ‘director’ providing high-level instructions, allowing for complex relationships and interactions between elements. The integration of 2D diffusion models further enhances the generated frames’ visual fidelity by ensuring that the composition adheres to the natural distribution of images, refining the visual quality and realism of the final video. The approach combines the strengths of LLMs for high-level conceptual understanding, 3D models for precise control of individual elements, and 2D diffusion models for high-fidelity image synthesis, resulting in a powerful method for generating sophisticated, controllable videos from textual descriptions.

2D Diffusion Priors#

The concept of “2D Diffusion Priors” in the context of 3D-aware video generation is a crucial technique for enhancing the realism and fidelity of generated videos. It leverages the significant advancements in 2D image diffusion models, which excel at generating high-quality and diverse images from textual prompts. By incorporating these pre-trained 2D diffusion models, the approach effectively transfers their learned knowledge of image statistics and natural textures into the 3D video generation process. This is particularly valuable because generating high-quality 3D content directly is often challenging due to limited training data. The 2D diffusion priors act as a powerful regularizer, guiding the generation of 3D video frames to adhere to a natural image distribution. This is achieved by incorporating the 2D diffusion model’s score function, which measures the distance between generated and real images in the latent space, thereby influencing the generation process. By utilizing techniques like score distillation sampling, the method seamlessly integrates these 2D priors with the 3D representation, refining the composition and ensuring that the generated visuals maintain photorealism and consistency. The strategy is particularly effective in tackling the challenges posed by compositional video generation, where multiple individual elements are combined. Therefore, the integration of 2D diffusion priors is a significant step toward realistic and controllable 3D-aware video generation.

Controllable Generation#

The concept of ‘Controllable Generation’ in the context of AI-driven video creation is a significant advancement, moving beyond simple text-to-video generation towards a more nuanced and intentional approach. The ability to exert fine-grained control over individual aspects of a video – such as the actions, appearance, and interactions of specific characters, or even the scene itself – is a crucial step towards making AI video generation truly useful and versatile. This level of control opens up possibilities for creative applications in filmmaking, animation, and beyond, where precise adjustments are often critical for realizing artistic visions. However, achieving truly flexible control is challenging, demanding sophisticated techniques to disentangle various elements and resolve potential conflicts. The discussed framework highlights the power of integrating Large Language Models (LLMs) and 3D representations to coordinate multiple concepts within the video, but the limitations must be acknowledged. Further research should focus on developing more robust methods for handling complex scenarios and relationships between objects and actions in 3D space. Ultimately, the goal is to create systems that not only generate videos automatically but also allow users to easily specify and manipulate various aspects of the output, making AI video generation tools accessible and powerful to a broader range of users.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this compositional 3D-aware video generation work could explore several key areas. First, expanding the range of concepts beyond the current set (scene, object, motion) to encompass a wider variety of elements within the video would greatly increase the system’s expressiveness. This involves developing or adapting suitable 3D representations for additional concepts and incorporating them into the LLM-guided compositional framework. Second, improving the handling of complex interactions between concepts, which is currently approximated with coarse guidance, would enhance the realism and consistency of the generated videos. This might involve more sophisticated modeling of physical dynamics or leveraging physics engines to ensure realistic object movement and interactions. Third, developing more efficient and scalable methods for 3D scene composition would be crucial for enabling longer and more complex videos. This could be addressed by exploring alternative approaches to 3D representation, more efficient composition algorithms, or leveraging advancements in hardware acceleration. Finally, investigating the use of learned priors from large-scale 3D video datasets, should they become available, could significantly improve the quality and fidelity of the generated videos. This would enable more sophisticated training of both the 3D generative models and the LLM director. Addressing these areas would advance the field of compositional 3D-aware video generation and lead to the creation of even more compelling and realistic videos.

More visual insights#

More on figures

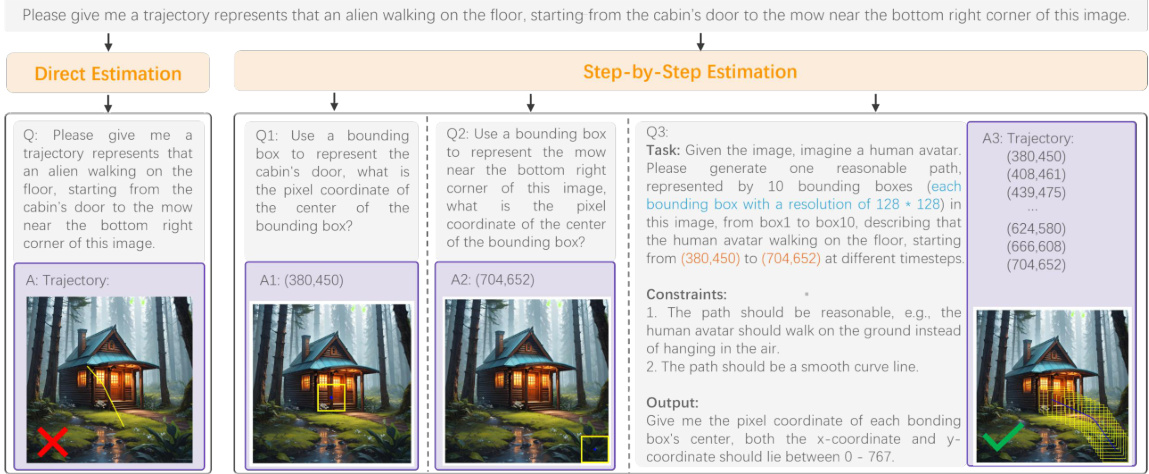

This figure illustrates the process of generating a trajectory using a Large Language Model (LLM). Instead of directly asking the LLM for a complete trajectory, which can lead to unrealistic results, the authors employ a step-by-step approach. First, they ask the LLM to identify the starting and ending points of the trajectory using bounding boxes. Then, they provide this information to the LLM, along with the image, and request a series of intermediate points that create a smooth path between the start and end. This approach makes it easier for the LLM to generate a reasonable and natural-looking trajectory.

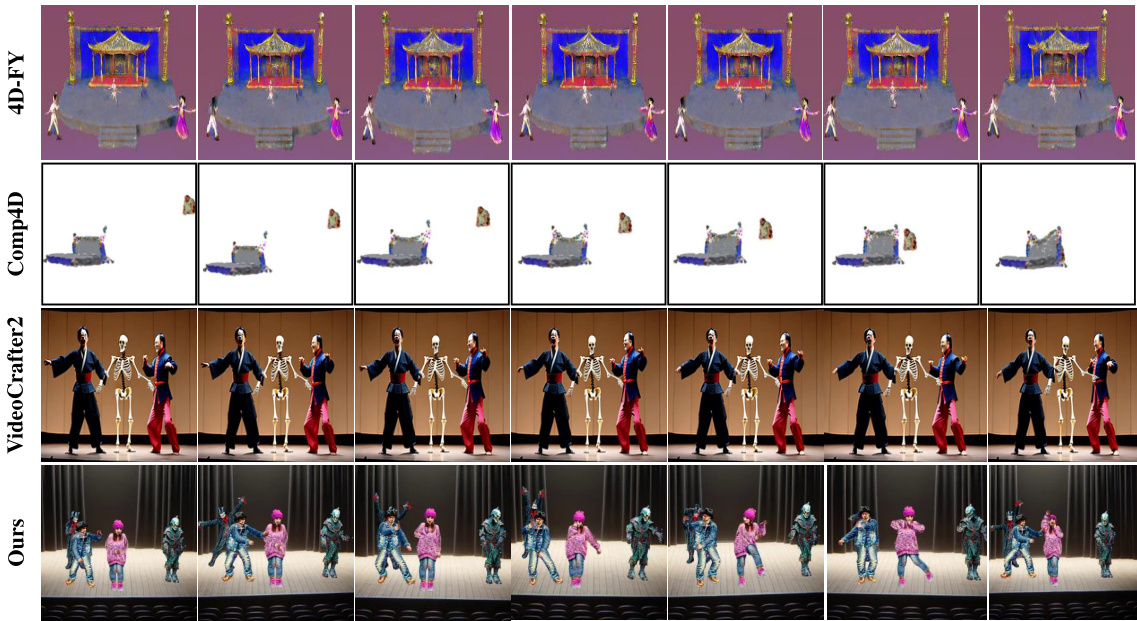

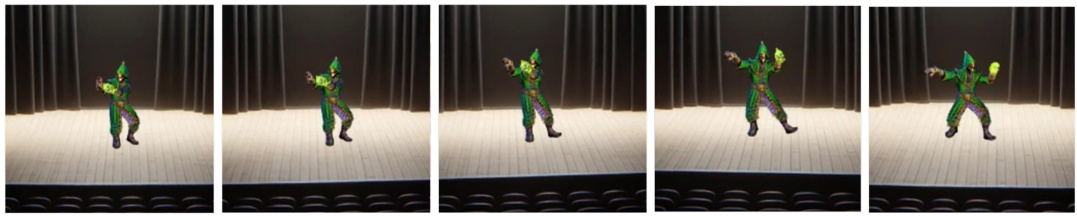

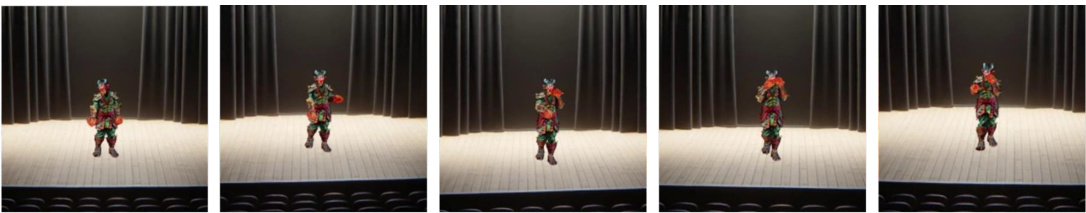

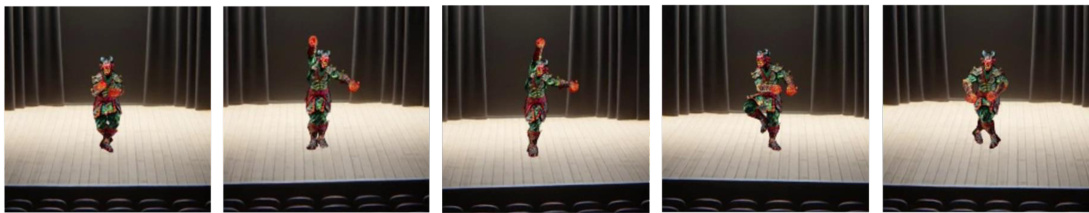

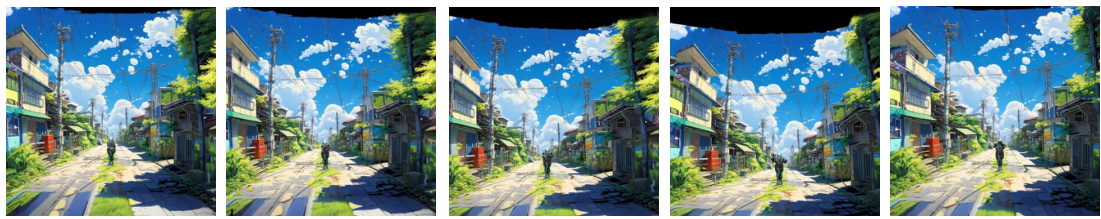

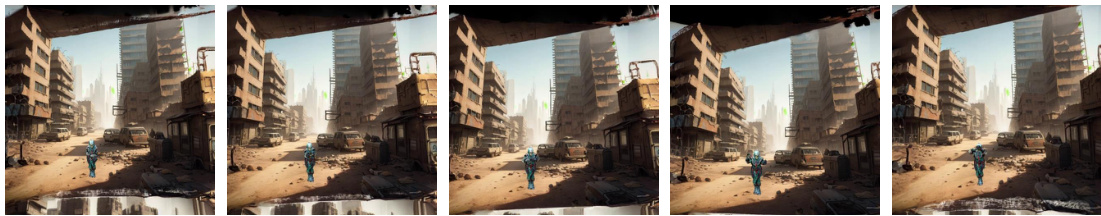

This figure compares the results of the proposed method (C3V) with three baseline methods (4D-FY, Comp4D, and VideoCrafter2) on two different text prompts. The results show that C3V outperforms baselines in generating videos with diverse motions and high visual quality, especially when dealing with complex queries containing multiple objects and actions.

This figure compares the video generation results of the proposed C3V model with three baseline models (4D-FY, Comp4D, and VideoCrafter2) on two complex text prompts. The results demonstrate that the baseline methods struggle to accurately generate videos with multiple objects and the corresponding motions, while the proposed C3V model is able to generate high-quality videos with diverse motions and high visual quality, fulfilling the requirements of the complex prompts.

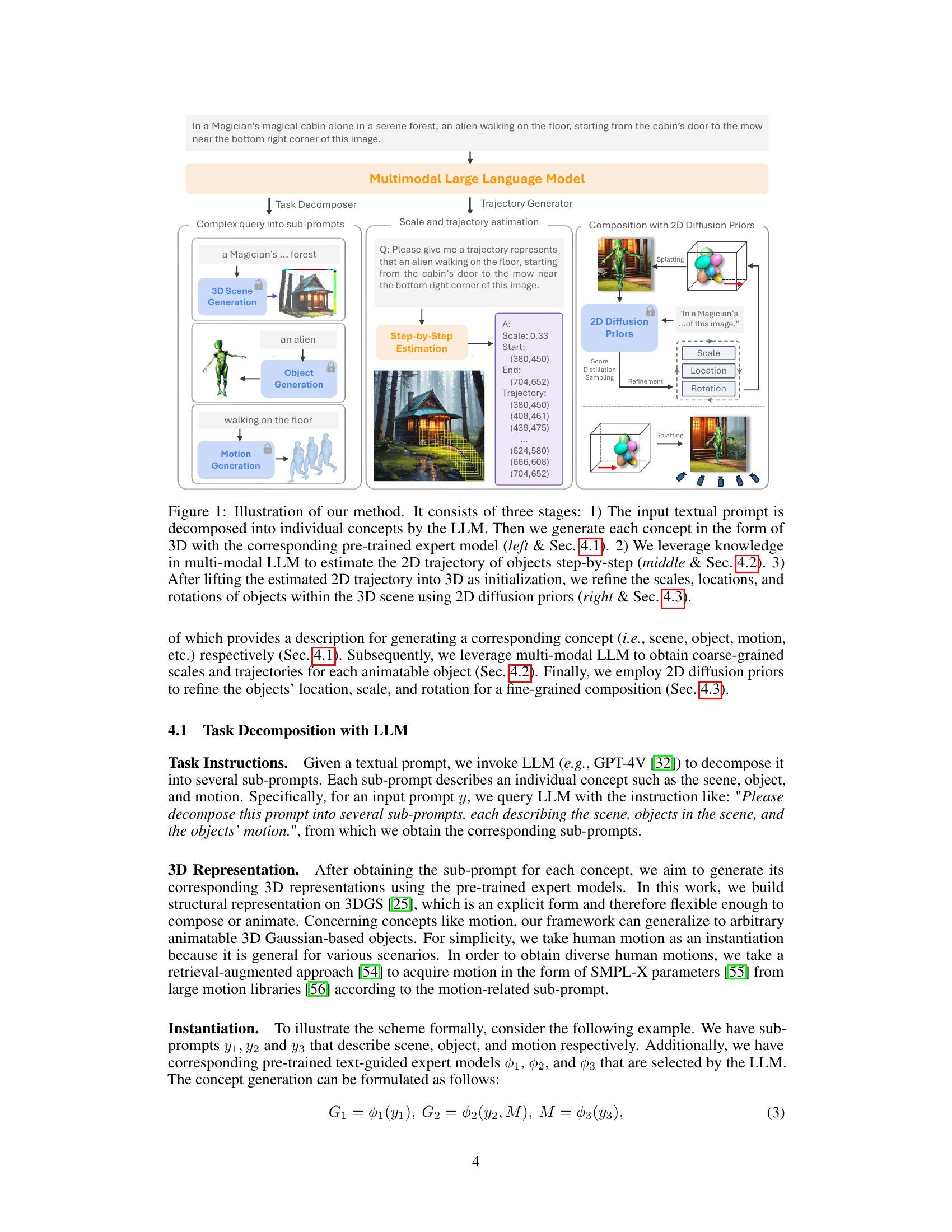

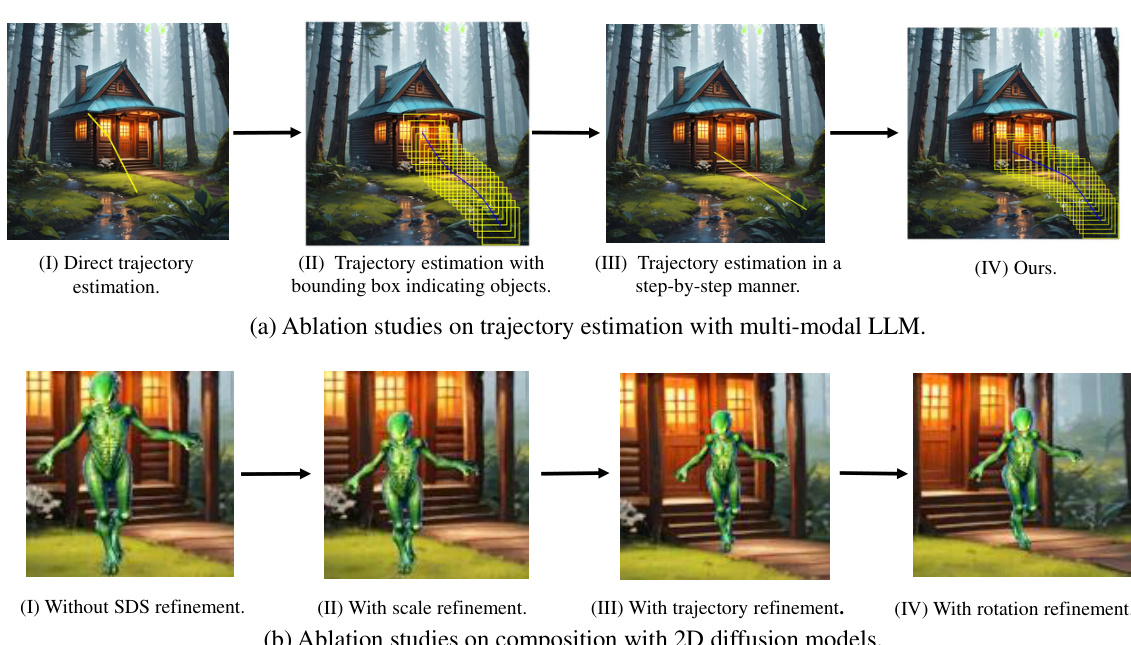

This figure presents ablation studies on the proposed C3V framework. The top row (a) shows the impact of different trajectory estimation methods using a multi-modal LLM: direct estimation, estimation with bounding boxes, step-by-step estimation, and the final C3V method. The bottom row (b) illustrates the effect of refining composition using 2D diffusion priors, showing results without refinement and with refinements to scale, trajectory, and rotation. Each ablation uses the same text prompt to highlight the impact of each design choice.

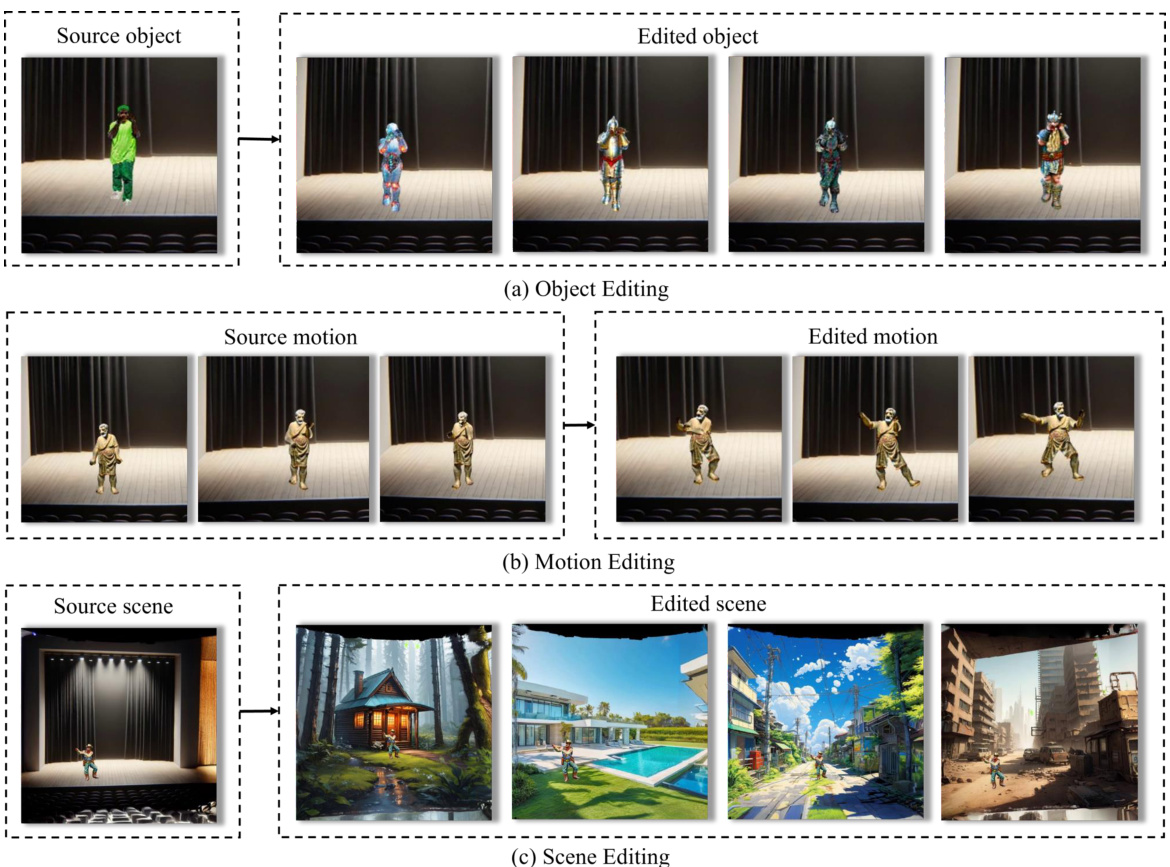

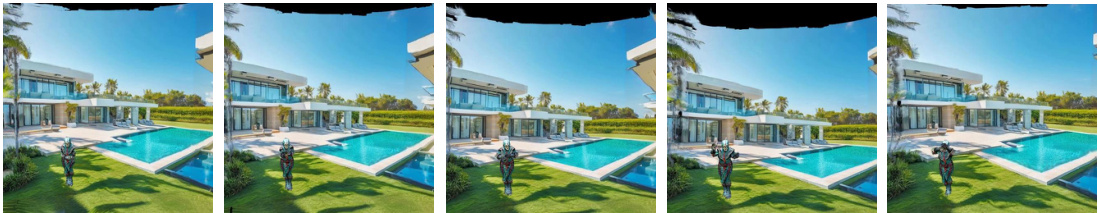

This figure shows the flexible control offered by the proposed method over individual concepts in the generated videos. It demonstrates this capability by presenting three editing scenarios: (a) Object Editing: Changing the appearance of an actor by replacing it with different objects. (b) Motion Editing: Modifying the motion of an actor by replacing its motion with different actions. (c) Scene Editing: Altering the background scene completely, showcasing the ability to seamlessly integrate the actors into new and varied environments.

This figure illustrates the three stages of the C3V model. The first stage is task decomposition using an LLM, which breaks down the complex prompt into sub-prompts describing the scene, the object (alien), and the motion (walking). The second stage is trajectory generation using an LLM, which estimates the trajectory of the alien by using bounding boxes and stepwise reasoning. The third stage is the rendering of the final video using 3D Gaussian splatting and 2D diffusion priors.

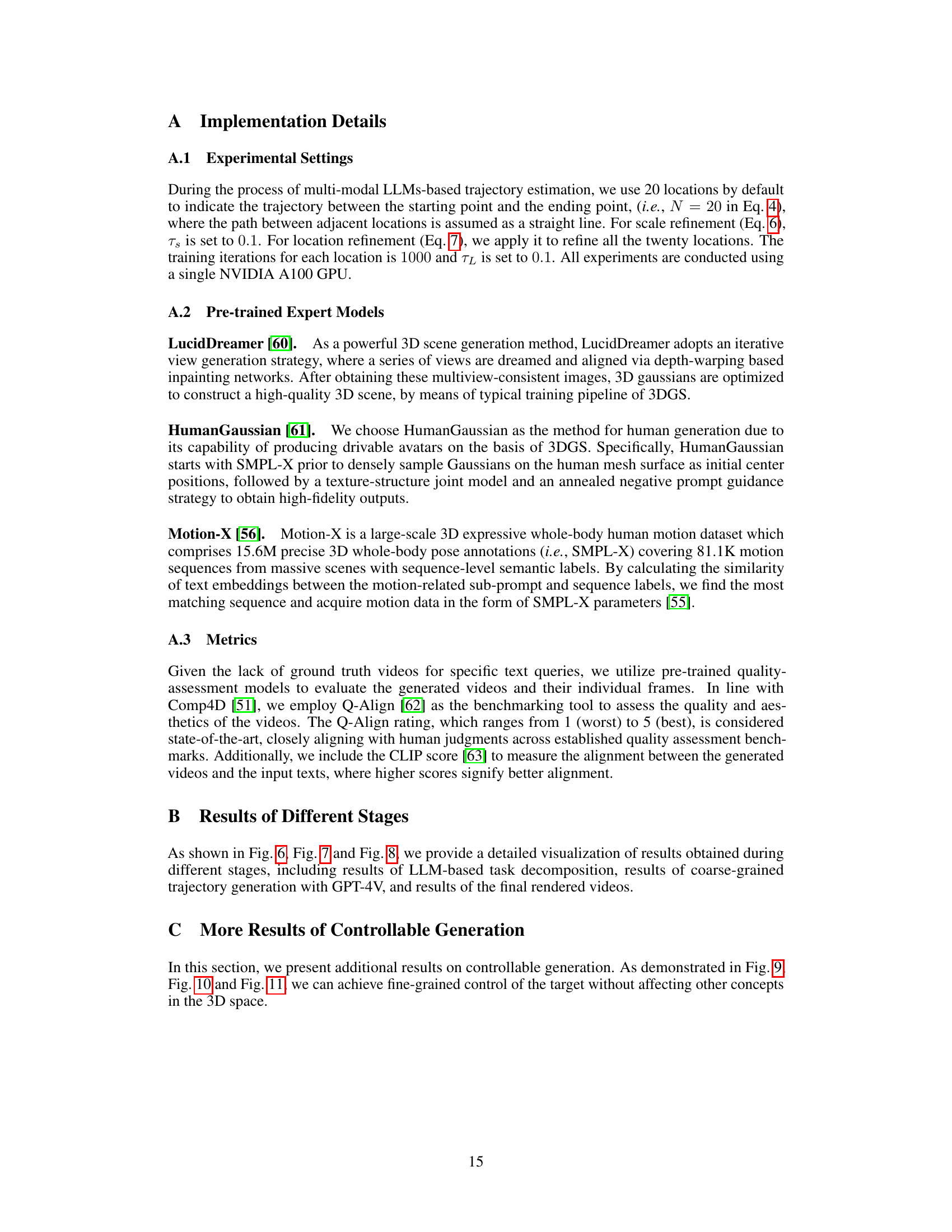

This figure shows a breakdown of the process for generating a video based on the given text prompt. It illustrates the three stages of the C3V method: Task Decomposition with LLM (breaking the complex prompt into sub-prompts), Trajectory Generation with LLM (estimating the trajectory based on the sub-prompts using a bounding box approach and refining through a step-by-step method), and finally the Rendered Video (output of the process). Each stage is visually represented, allowing one to see how the initial prompt is translated into a coherent video.

This figure shows a breakdown of the process of generating a video using the C3V method. It starts with task decomposition using an LLM to break down the input prompt into individual concepts (a simple stage, a man in a specific outfit performing kung fu, a woman in ski clothes dancing). Then, trajectory generation uses the LLM to estimate the path each character will take on the stage, leveraging bounding boxes to help define starting and ending points. Finally, the rendered video output from the three stages is shown.

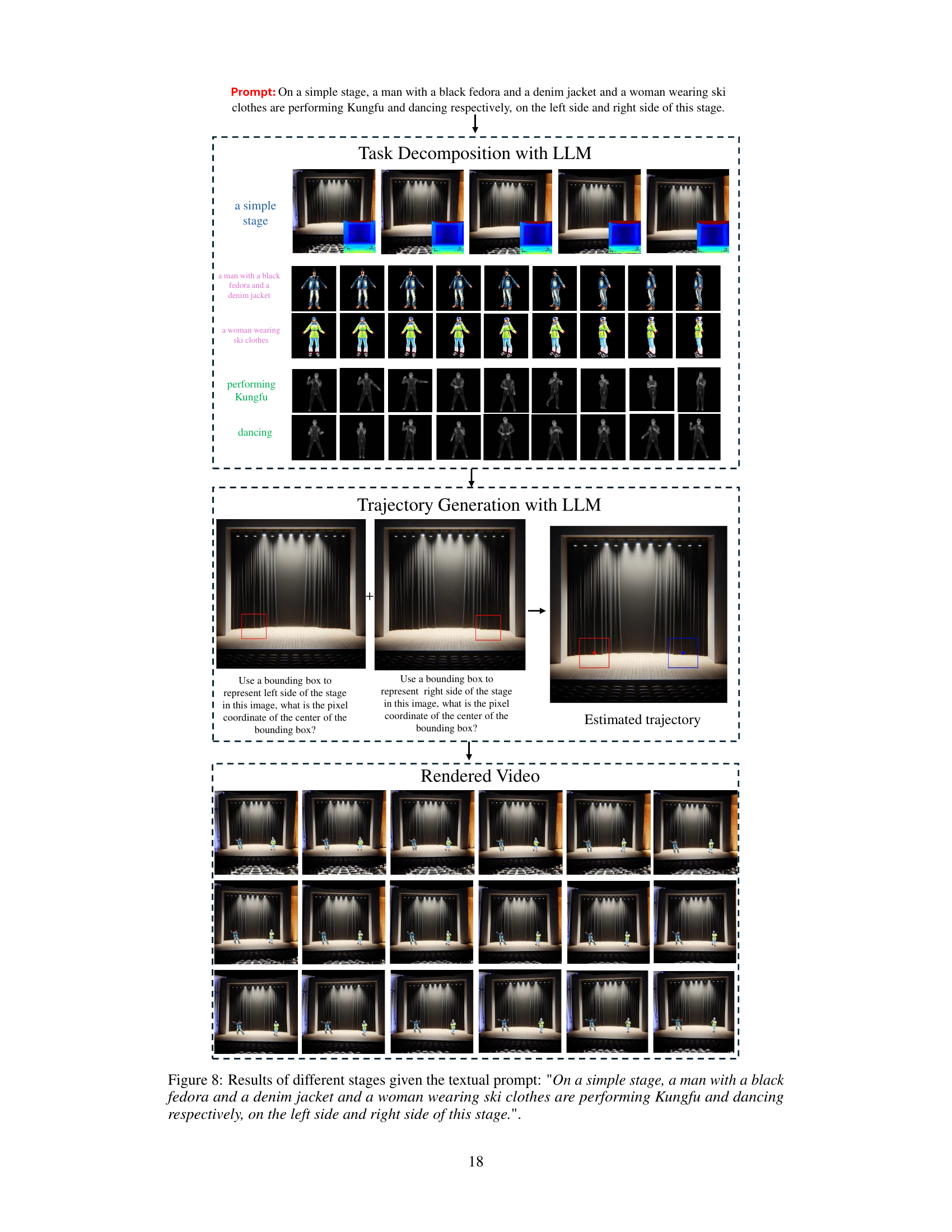

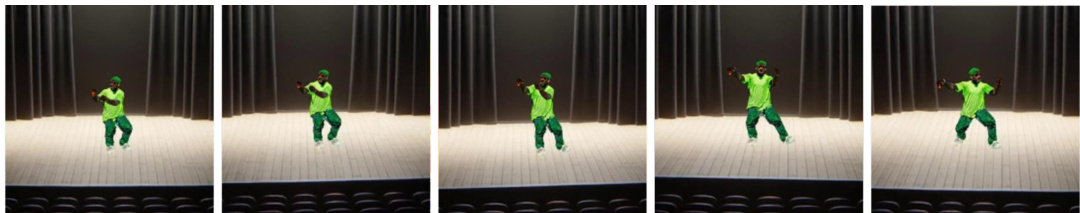

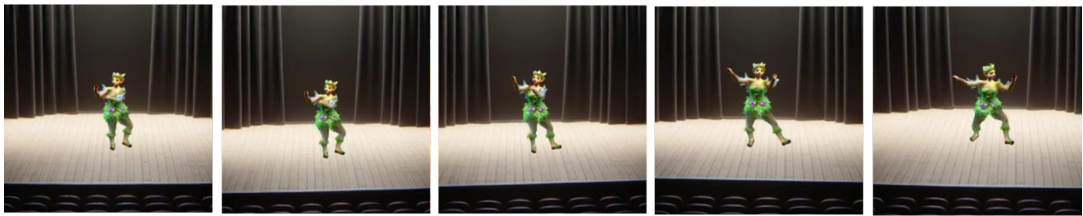

This figure shows the results of editing the appearance of an actor in a generated video. Four different prompts are tested: (a) A black man wearing a green t-shirt playing Kungfu on the stage; (b) Turn the character into a fairy; (c) Turn the character into a warlock. Each prompt demonstrates the system’s ability to change the actor’s visual characteristics in the generated video sequence.

This figure shows the results of editing the appearance of the actor in a generated video. The top row shows a video of a black man in a green shirt performing Kung Fu. The next two rows show the same video but with the actor’s appearance changed, first into a fairy and then into a warlock. This demonstrates the model’s ability to alter the visual characteristics of individual elements within a generated scene.

This figure shows the results of the actor’s appearance editing experiment. The top row shows a baseline video of a black man in a green shirt performing kung fu on a stage. The subsequent rows demonstrate edits of that character’s appearance. The second row shows the character transformed into a fairy; the third row, into a warlock. This demonstrates the system’s ability to alter the appearance of a character based on textual prompts.

This figure shows the results of editing the appearance of the actor in a generated video. Subfigure (a) shows the original generated video of a black man in a green t-shirt doing Kung Fu. Subfigure (b) shows the same video, but the character has been changed to a fairy. Subfigure (c) shows the same video again, but with the character changed to a warlock. This demonstrates the ability of the model to edit the appearance of the character by simply changing a textual prompt.

This figure shows the results of editing the appearance of the actor in a generated video. Four subfigures show the results using different prompts. Subfigure (a) shows the base result, with a black man wearing a green t-shirt. Subfigure (b) changes the character’s appearance to that of a fairy, Subfigure (c) shows the result of changing the character into a warlock.

This figure shows the results of editing the appearance of an actor in a generated video. Four image sequences are presented, each corresponding to a different prompt. (a) shows a base video with a black man in a green shirt. (b) modifies the prompt to change the character to a fairy. (c) changes the prompt to turn the character into a warlock. Each row displays the resulting video frames demonstrating that the model successfully alters the character’s appearance based on the textual instructions given.

This figure shows the results of scene editing in the C3V model. Three sub-figures demonstrate how easily the scene can be changed while retaining the other elements (character and action). (a) shows a scene with a modern mega villa by the sea and a swimming pool, (b) transforms the scene into an anime-style road, and (c) changes the setting to a post-apocalyptic desert city. This illustrates the model’s capacity for flexible and precise control over individual scene components during video generation.

This figure illustrates the three-stage process of the proposed C3V method. Stage 1 uses an LLM to decompose the input text prompt into individual concepts (scene, objects, motion). Stage 2 estimates the 2D trajectory of the objects using a multi-modal LLM. Stage 3 refines the 3D representation of the objects using 2D diffusion priors.

This figure shows three examples of scene editing using the proposed method. In (a), the original scene is a modern mega-villa by the sea, and the prompt is changed to show the character dancing in the scene. In (b), the scene is changed to a long anime-style road, and in (c), the scene is transformed into a post-apocalyptic city in the desert. This demonstrates the flexibility of the method to edit the scene while keeping the character consistent.

More on tables

This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for trajectory estimation using a multi-modal large language model (LLM). It compares four approaches: Direct Estimation, Estimation using bounding box, Step-by-step estimation, and the authors’ proposed method (Ours). The metrics used for comparison include QAlign scores for image and video quality and aesthetics, as well as CLIP scores reflecting the alignment between generated videos and textual prompts. Higher scores indicate better performance. The table shows that the authors’ method consistently outperforms the baseline methods across all metrics.

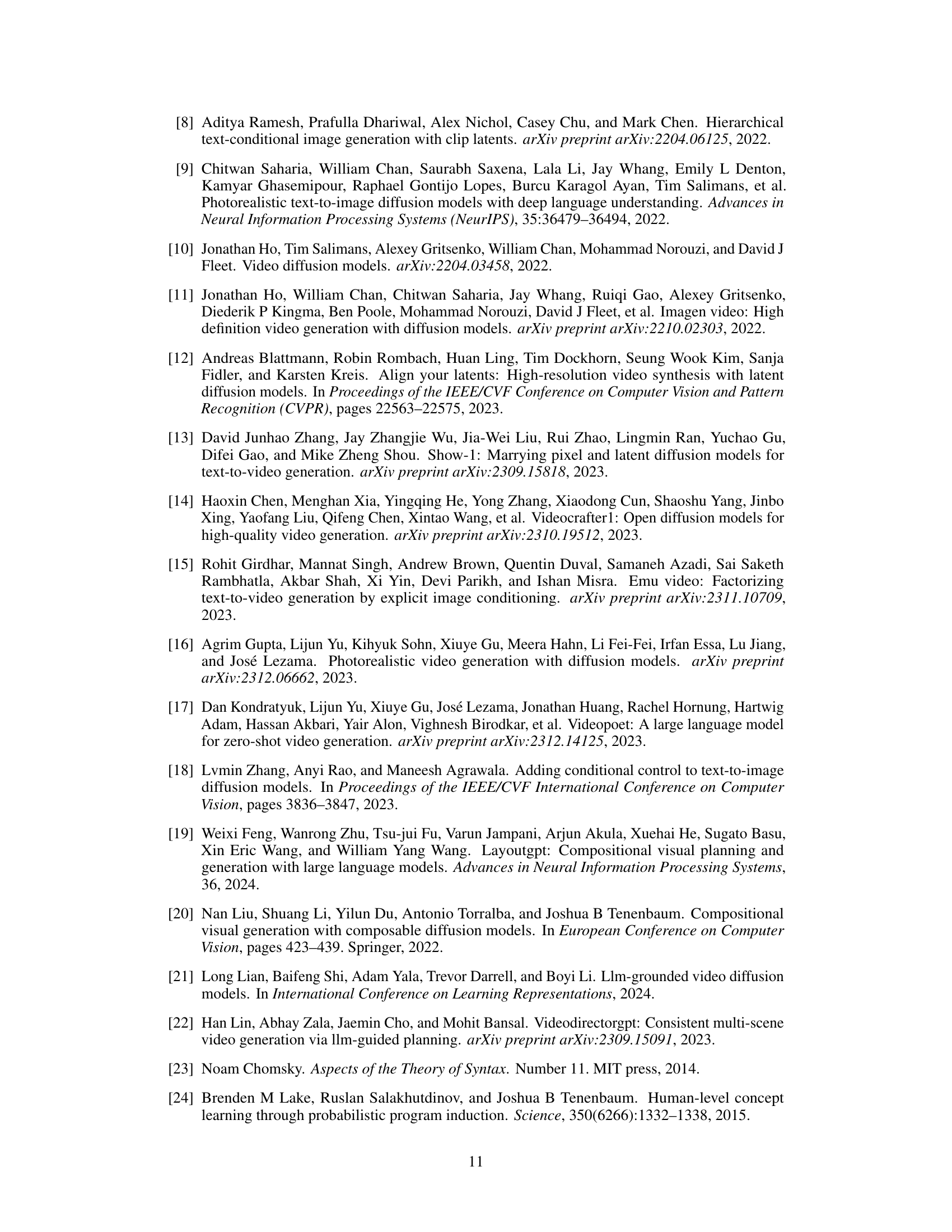

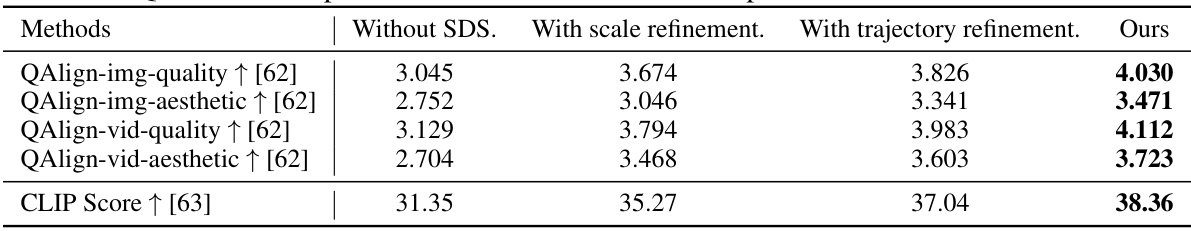

This table presents a quantitative comparison of the ablation studies conducted on the composition with 2D diffusion models. It shows the impact of different stages of refinement (without SDS, with scale refinement, with trajectory refinement) on several metrics: QAlign-img-quality, QAlign-img-aesthetic, QAlign-vid-quality, QAlign-vid-aesthetic, and CLIP Score. Higher scores indicate better performance. The ‘Ours’ column shows the results with all refinements applied.

Full paper#