↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current LLM alignment methods often involve two stages: supervised fine-tuning (SFT) using human demonstrations, and reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) using preference data to further refine the model. However, SFT’s reliance solely on demonstration data can lead to suboptimal performance due to distribution shifts and the presence of low-quality data. This paper addresses these issues by arguing that the SFT stage significantly benefits from incorporating reward learning.

The paper proposes a novel framework that leverages inverse reinforcement learning (IRL) to simultaneously learn a reward model and a policy model directly from the demonstration data. This approach addresses the limitations of existing methods, leading to new, more efficient, and robust SFT algorithms. The authors introduce two algorithms, RFT (explicit reward learning) and IRFT (implicit reward learning), and provide theoretical convergence guarantees for the IRFT algorithm. Empirical results on 1B and 7B models demonstrate significant performance improvements compared to existing SFT approaches on benchmark reward models and the HuggingFace Open LLM Leaderboard. The work thus significantly advances the field of LLM alignment by highlighting the benefits of reward learning at the SFT stage.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges the conventional wisdom in large language model (LLM) alignment by demonstrating the significant benefits of incorporating reward learning into the supervised fine-tuning (SFT) stage. This opens avenues for more efficient and robust LLM alignment, particularly valuable given the current focus on large-scale model training and the increasing need for aligned AI systems. The theoretical analysis and empirical results provide a strong foundation for future research in reward-based SFT approaches.

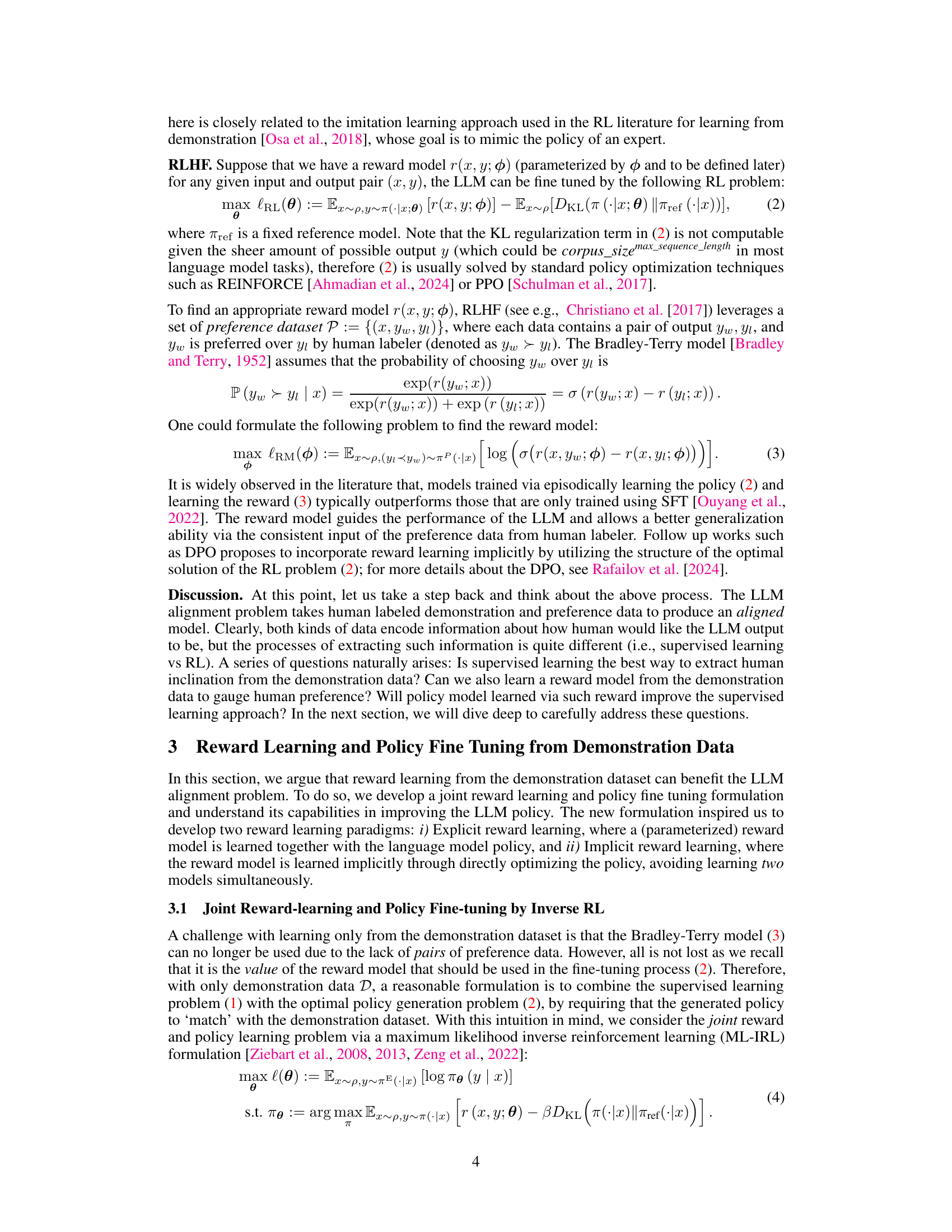

Visual Insights#

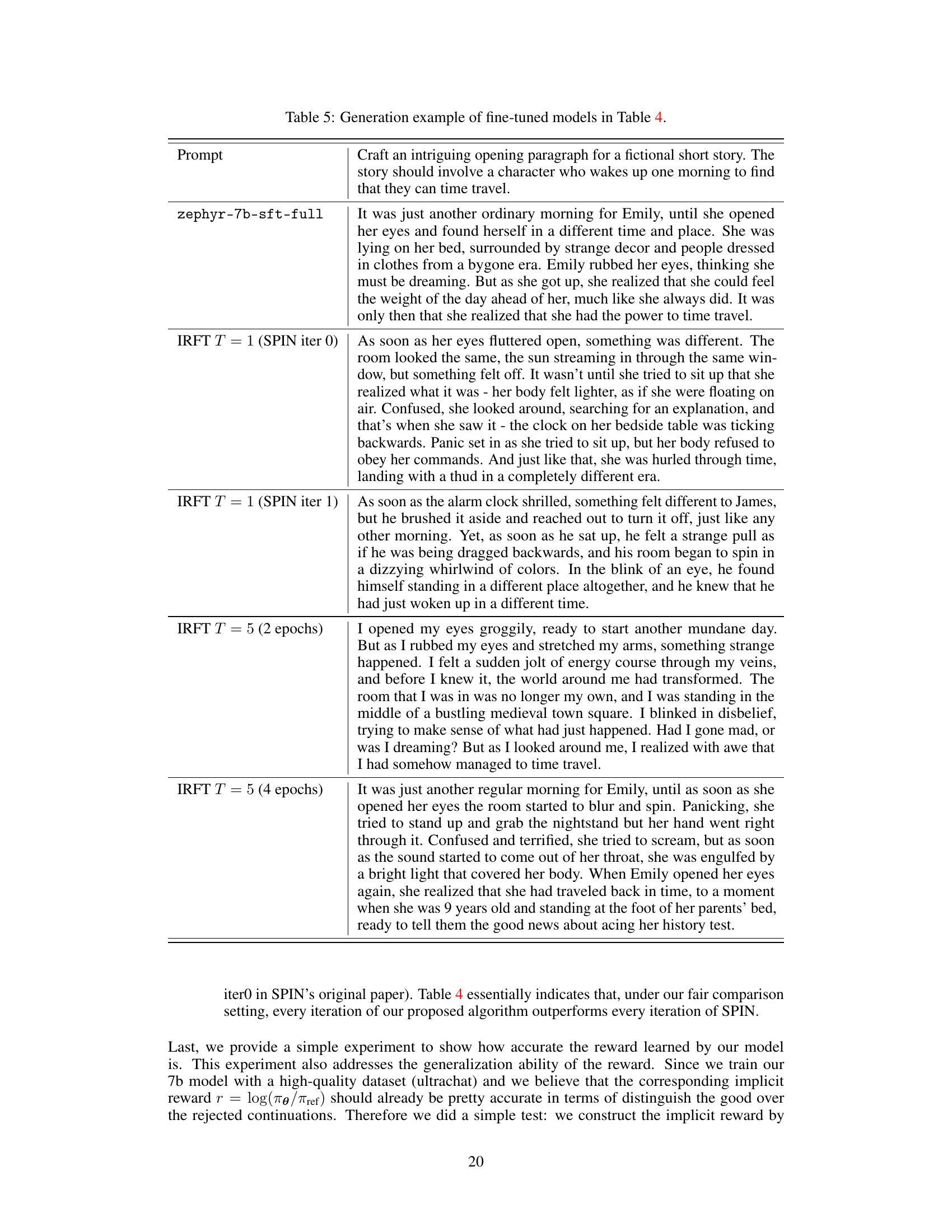

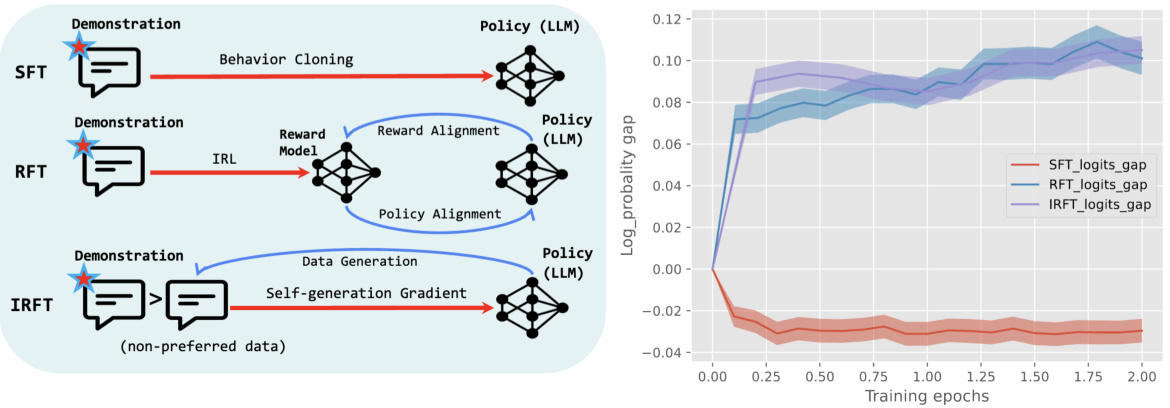

This figure compares three methods for Large Language Model (LLM) alignment: Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT), Reward Fine-Tuning (RFT), and Implicit Reward Fine-Tuning (IRFT). The left panel shows the conceptual differences in the methods’ approaches. SFT uses only behavior cloning on demonstration data. RFT incorporates Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL) to learn a reward model simultaneously with a policy model. IRFT leverages self-generated data to implicitly learn a reward model and refine the policy. The right panel shows the log probability gap between chosen/preferred and rejected/non-preferred continuations. RFT and IRFT show a greater ability to distinguish between these than SFT, even when trained only on chosen/preferred data. This highlights the effectiveness of the proposed reward learning methods in LLM alignment.

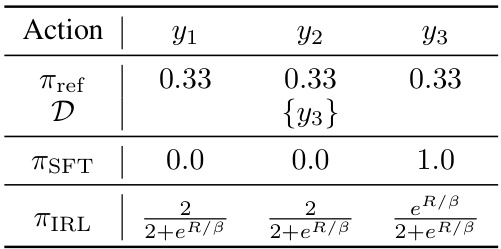

This table presents a simplified example with one state and three actions to illustrate the difference between SFT (Supervised Fine-Tuning) and IRL (Inverse Reinforcement Learning) methods in handling unseen data. SFT assigns all probability to the observed data point, while IRL distributes the probability more evenly, demonstrating its regularization effect and robustness to unseen data.

In-depth insights#

Reward-Augmented SFT#

Reward-augmented supervised fine-tuning (SFT) represents a significant advancement in large language model (LLM) alignment. Standard SFT directly trains LLMs on human-demonstration data, often resulting in suboptimal performance due to limitations in the data’s coverage of the full range of possible tasks. Reward-augmented SFT addresses this by incorporating a reward model learned from human demonstrations or preferences. This reward model guides the fine-tuning process, incentivizing the LLM to generate responses that align with human values and preferences. This approach offers several advantages: improved generalization to unseen data, enhanced robustness to low-quality demonstrations, and more efficient learning, enabling better alignment with human intentions, even with limited training data. By integrating reward learning into the SFT framework, reward-augmented SFT achieves a better balance between supervised learning efficiency and reinforcement learning’s ability to capture complex human preferences, resulting in more aligned and capable LLMs.

IRL for LLM Alignment#

Inverse Reinforcement Learning (IRL) offers a compelling approach to LLM alignment by learning reward functions directly from human demonstrations. Unlike traditional Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), which separates reward modeling from policy optimization, IRL tackles both simultaneously. This approach proves advantageous by potentially resolving issues related to data quality and distribution shifts commonly seen in supervised fine-tuning. By learning a reward model alongside the policy, IRL algorithms can implicitly capture human preferences expressed within the demonstration data, leading to more robust and efficient alignment. The theoretical convergence guarantees of some IRL-based methods provide further confidence in their reliability. However, the computational cost of jointly learning the reward and policy can be significantly higher than simpler approaches like supervised fine-tuning, representing a key challenge to overcome for wider adoption. Future research should focus on developing efficient IRL algorithms that address this computational hurdle while maintaining the advantages of implicit preference learning.

Empirical Evaluation#

An empirical evaluation section in a research paper should meticulously detail the experimental setup, including datasets used, model architectures, evaluation metrics, and baseline methods. Robustness checks are crucial, demonstrating the method’s consistency across different settings and datasets. Statistical significance should be established, using appropriate tests to ensure results aren’t due to chance. Clear visualizations of results, such as charts and tables, aid comprehension. The discussion should interpret the findings, comparing performance against baselines, highlighting strengths and weaknesses, and suggesting future improvements. Limitations of the evaluation should be transparently addressed, acknowledging factors that might affect the generalizability of the results. Ultimately, a strong empirical evaluation builds confidence in the proposed methods, paving the way for future research.

Convergence Analysis#

A rigorous convergence analysis is crucial for establishing the reliability and efficiency of any machine learning algorithm. For the reward-learning fine-tune (RFT) and implicit reward-learning fine-tune (IRFT) algorithms presented, a comprehensive convergence analysis would involve demonstrating that the iterative processes used to update model parameters and the reward model converge to a stationary point or optimal solution. This may involve establishing convergence rates, proving boundedness of iterates, demonstrating monotonicity of the objective function, and analyzing the effect of various hyperparameters on the convergence behavior. Finite-time convergence guarantees, as mentioned in the context of comparing to related works, would be a significant theoretical contribution. The analysis would likely need to handle the complexities of the bilevel optimization structure, potentially employing techniques from non-convex optimization or stochastic approximation theory. Successfully establishing convergence would significantly enhance the credibility and practical value of the proposed algorithms.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the efficiency and scalability of reward learning algorithms is crucial for wider adoption. This includes investigating more efficient ways to collect and process human feedback, as well as developing more robust reward models that are less susceptible to noise or bias. Expanding the range of tasks and domains to which these methods are applied is important to demonstrate their broader impact. This might involve applying reward learning to more complex tasks requiring nuanced reasoning, or exploring new applications in areas like robotics and decision-making. A deeper theoretical understanding of the convergence properties and generalization capabilities of reward learning would strengthen the foundations of this promising field. This also includes research into how reward models can best capture human preferences, and how to mitigate potential biases that may arise. Addressing the ethical implications of using reward learning to align LLMs is essential to responsible development. This requires careful consideration of factors like fairness, transparency, and safety, and the development of methods to minimize the risk of unintended consequences.

More visual insights#

More on tables

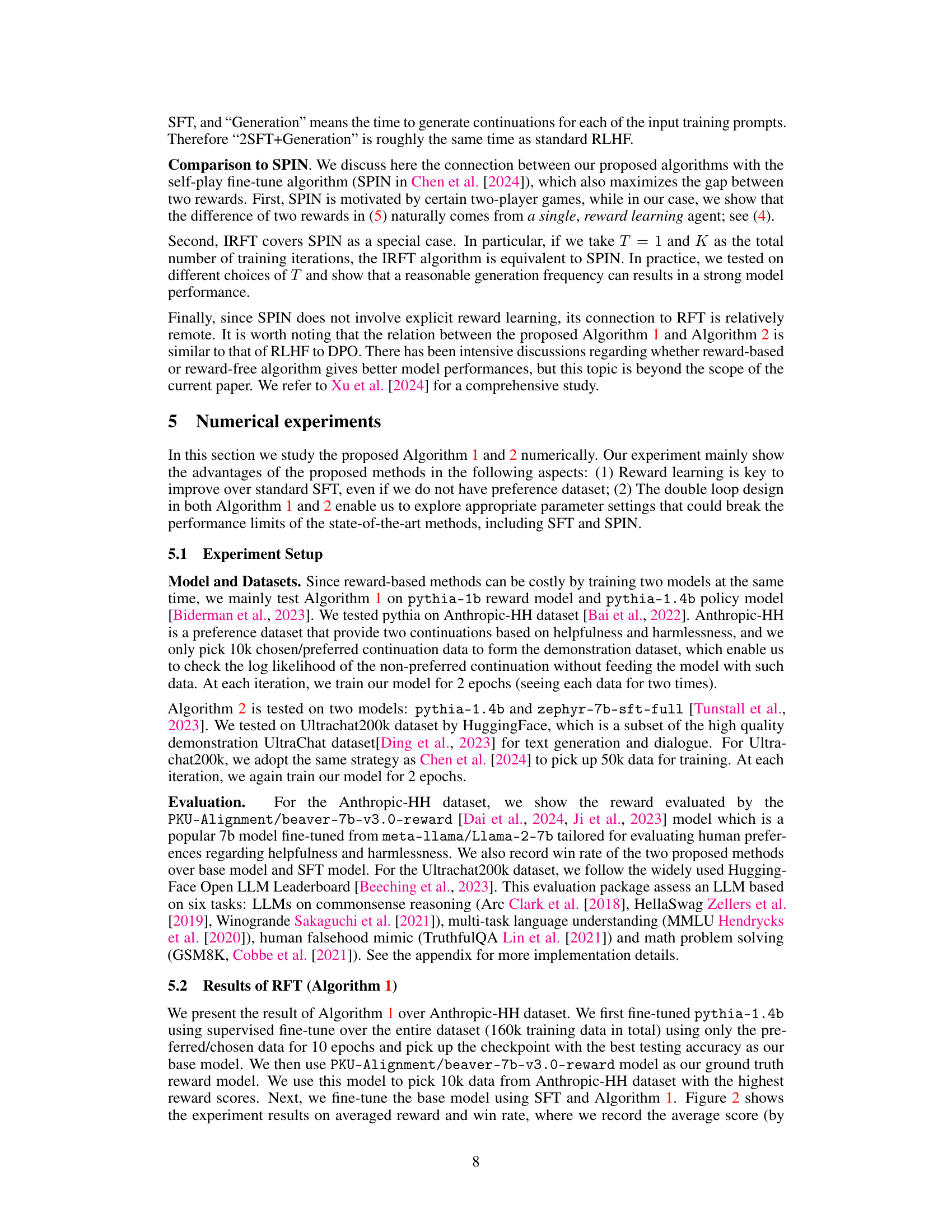

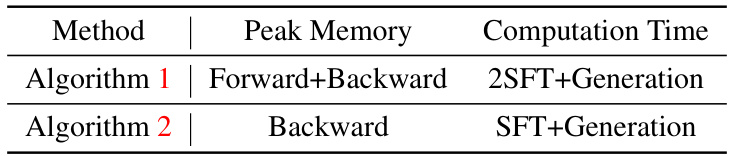

This table compares the memory usage and computation time for Algorithm 1 and Algorithm 2, relative to standard Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT). Algorithm 1, which involves training a reward model and a policy model simultaneously, requires more memory (Forward+Backward) and has a computation time equivalent to 2SFTs plus the time required for generating continuations. Algorithm 2, which implicitly learns the reward model through self-generation, is more efficient, requiring less memory (Backward) and a computation time comparable to a single SFT plus generation time.

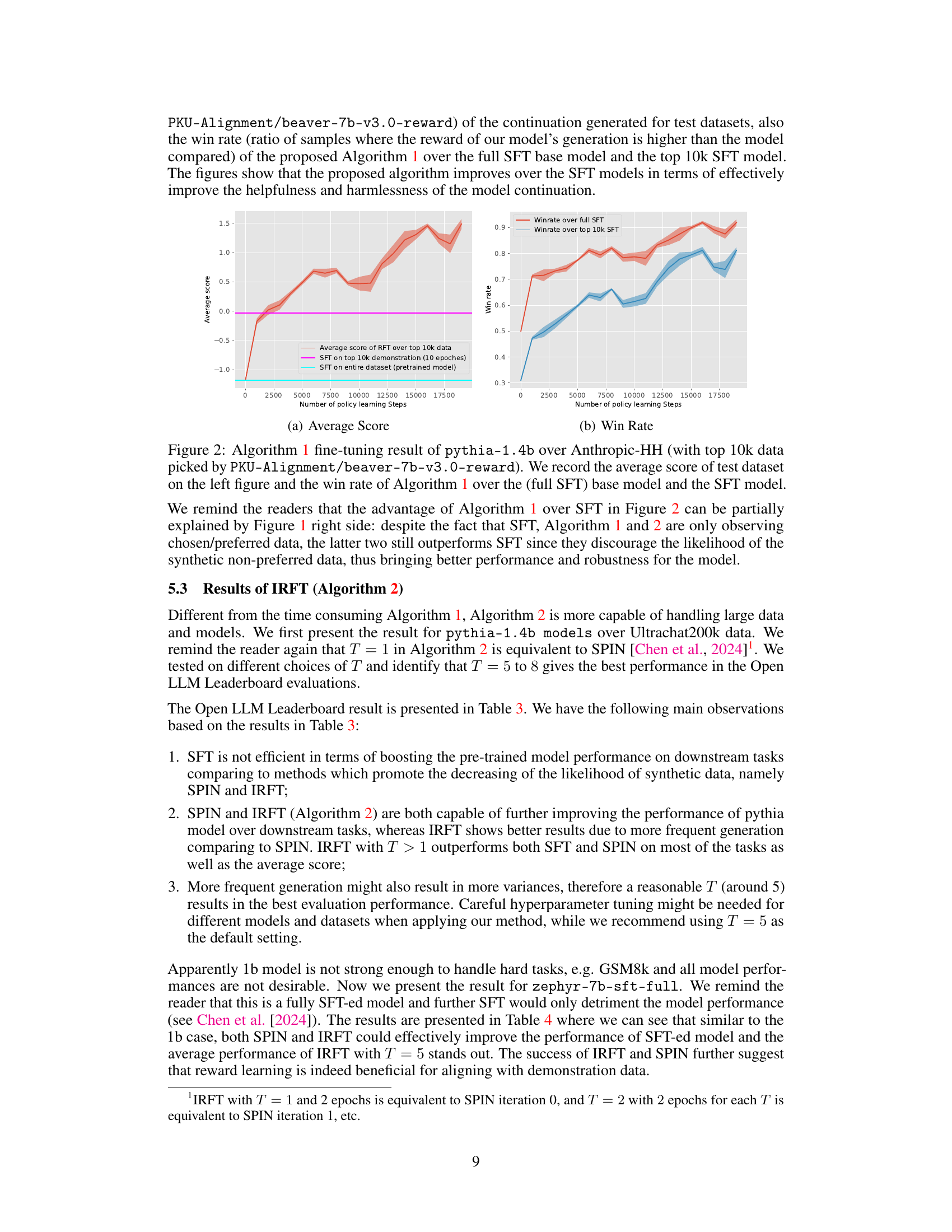

This table presents the performance of the Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT), Self-Play Fine-tune (SPIN), and Implicit Reward-learning Fine-Tune (IRFT) methods on the pythia-1.4b model across various tasks from the HuggingFace Open LLM Leaderboard. It compares the performance using different numbers of training epochs and shows the impact of the proposed IRFT method on model performance. The results demonstrate the improved performance of IRFT, especially when compared to the baseline SFT method.

This table presents the performance comparison between Standard Fine-tuning (SFT), Self-Play Fine-tuning (SPIN), and the proposed Implicit Reward Fine-tuning (IRFT) methods on the Pythia-1.4b model. The evaluation is conducted across multiple tasks from the HuggingFace Open LLM Leaderboard. The table shows the performance metrics for each method, including accuracy and exact match scores, and varying the number of iterations (T and K) for the IRFT algorithm.

This table presents the results of experiments comparing the performance of the Self-Play Fine-tune (SPIN) algorithm and the proposed Implicit Reward-learning Fine-tuning (IRFT) algorithm (Algorithm 2 in the paper) on the Pythia-1.4b language model. The models were evaluated across various tasks from the HuggingFace Open LLM Leaderboard. The table shows the performance metrics (accuracy, exact match, etc.) achieved by different versions of the model (with different values of T, a hyperparameter that controls the training process). This table helps illustrate the effectiveness of the IRFT algorithm in improving the performance of the LLM for multiple tasks.

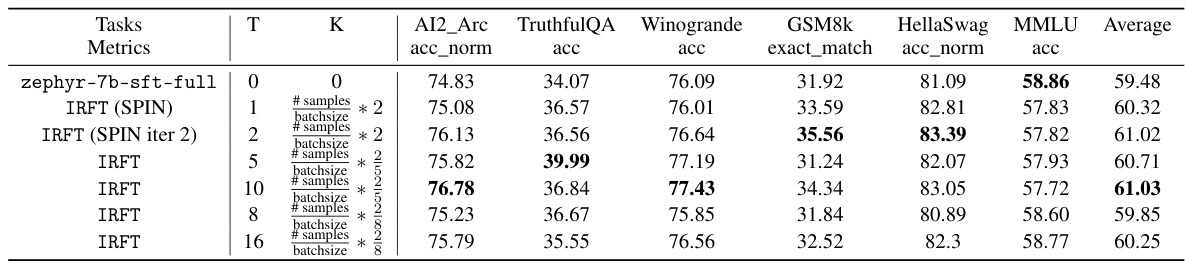

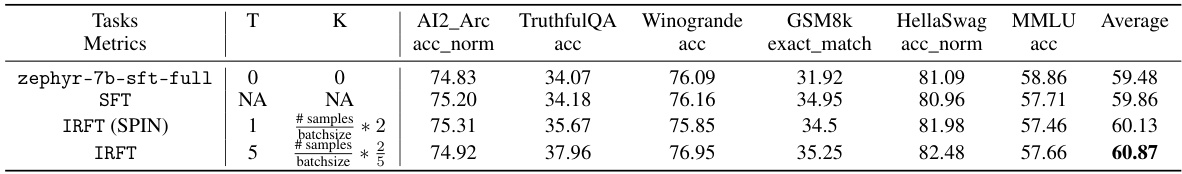

This table shows the performance comparison of different methods on the HuggingFace Open LLM Leaderboard. The methods compared include Standard Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT), Self-Play Fine-Tune (SPIN), and the proposed Implicit Reward Fine-Tuning (IRFT) method with different numbers of training epochs. The results are presented across various tasks included in the leaderboard, highlighting the improvement in performance achieved by the proposed method over SFT and SPIN.

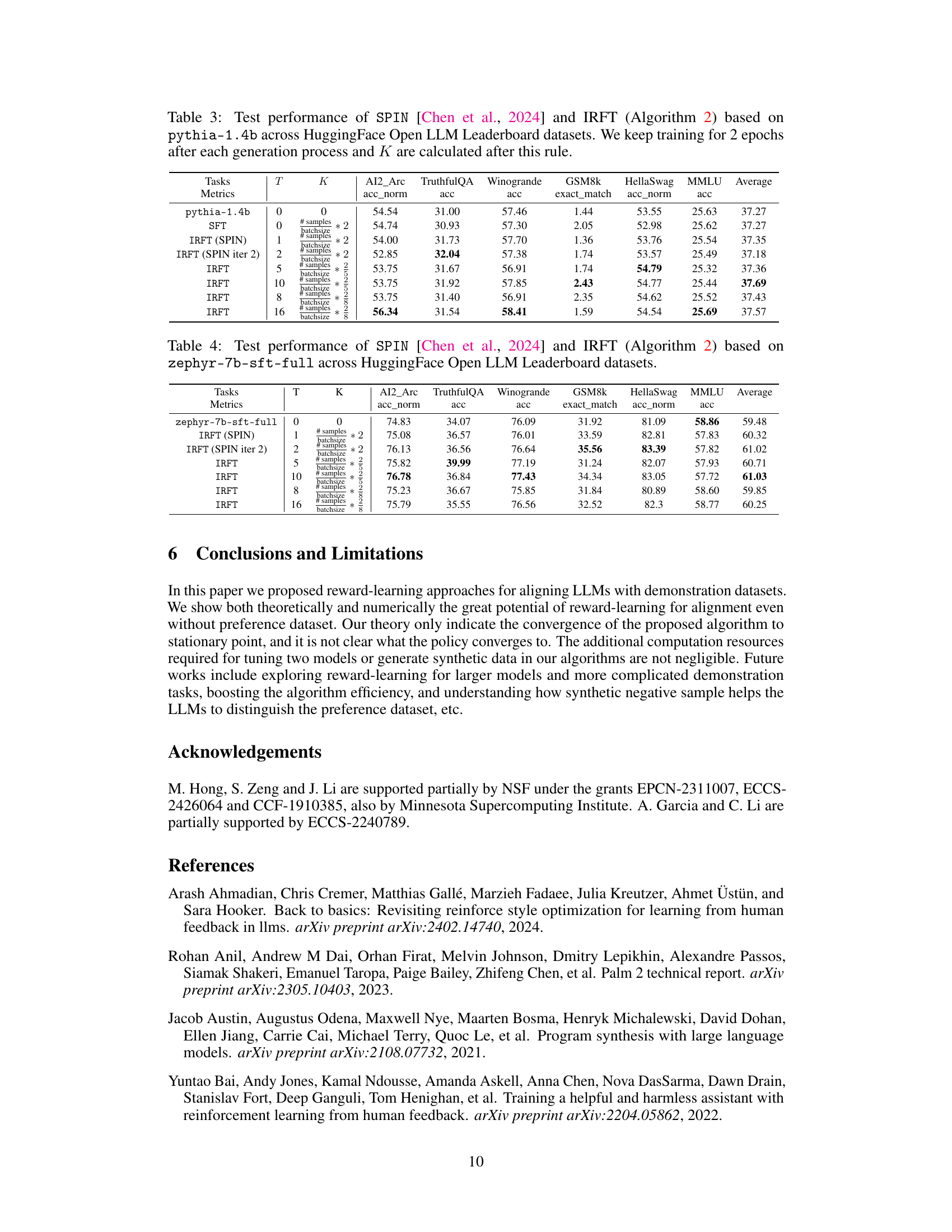

This table compares the performance of different versions of the base model, zephyr-7b-sft-full, across various tasks from the HuggingFace Open LLM Leaderboard. It highlights the impact of using different versions of the evaluation code and model on the overall results, emphasizing the importance of consistent evaluation methodology for accurate comparisons.

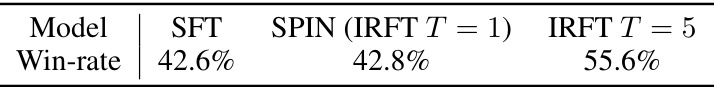

This table shows the win-rate of models trained using different methods: SFT, SPIN (which is equivalent to IRFT with T=1), and IRFT with T=5. The win-rate represents the percentage of times the reward of the model’s generated continuation is higher than the reward of the reference model’s continuation. The results demonstrate the improvement in the ability to distinguish between preferred and rejected continuations as the method progresses from SFT to IRFT with T=5, showcasing the efficacy of the reward learning approach.

Full paper#