↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current neural operators for solving physics problems often suffer from scalability issues. Different techniques are used for various simulation datasets (e.g., Lagrangian vs. Eulerian), leading to problem-specific designs. This limits their application to large and complex simulations. Furthermore, existing methods often face computational bottlenecks when dealing with high-resolution data and large datasets.

Universal Physics Transformers (UPTs) address these challenges. UPTs utilize a unified learning paradigm, encoding data flexibly into a compressed latent space representation. This allows them to operate efficiently without relying on grid or particle-based latent structures, improving scalability across meshes and particles. The inverse encoding and decoding in the latent space enables efficient dynamic propagation and allows for queries at any point in space-time. The diverse applicability and efficacy of UPTs are demonstrated in simulations of mesh-based fluids, Reynolds-averaged Navier-Stokes, and Lagrangian-based dynamics.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on physics-informed neural networks and scientific machine learning. It introduces a novel, unified framework (UPTs) that significantly improves the scalability and efficiency of neural operators for various spatio-temporal problems. The scalability of UPTs addresses a critical challenge in the field, enabling the application of these powerful models to significantly larger and more complex datasets than previously possible. The work also opens exciting avenues for future research in large-scale scientific simulations and unified modeling paradigms.

Visual Insights#

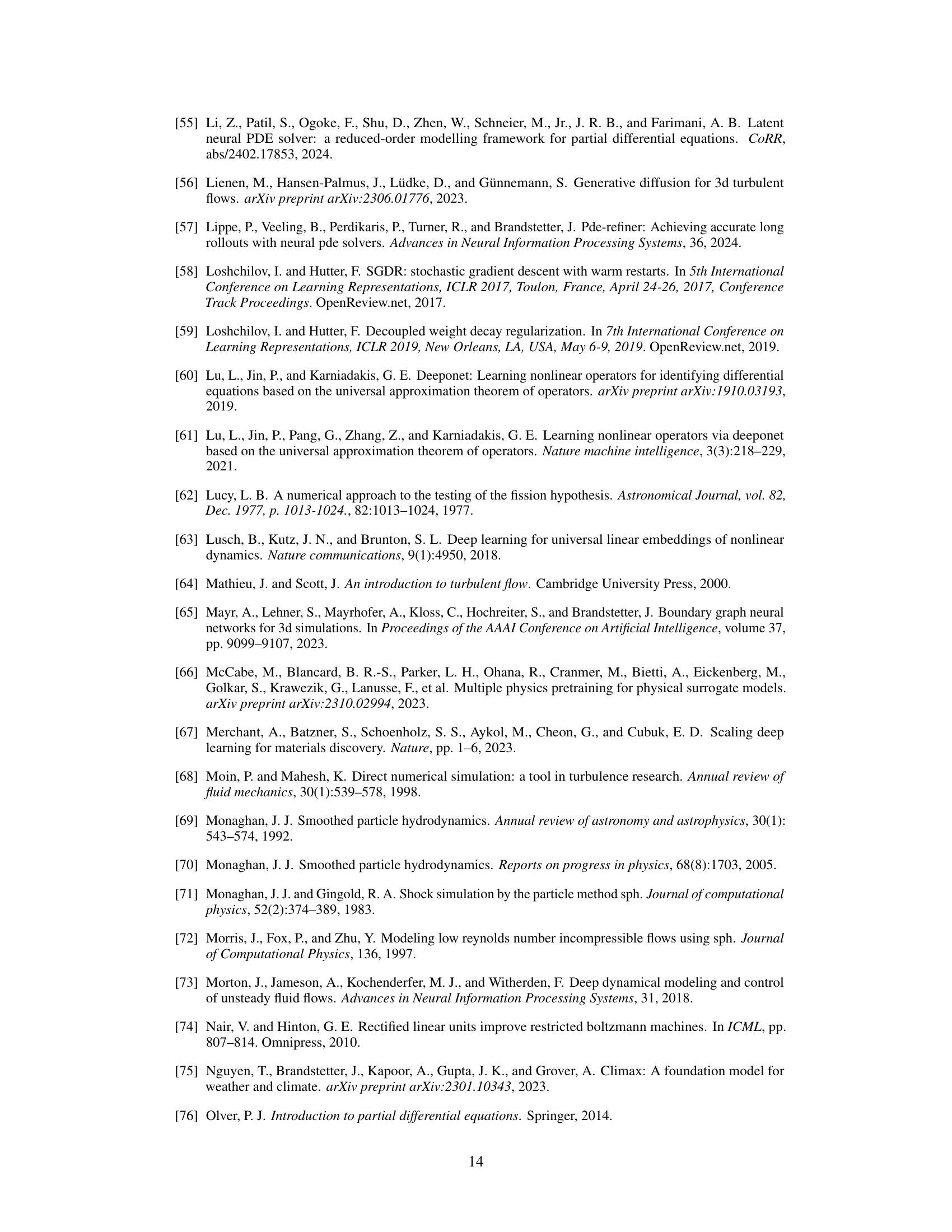

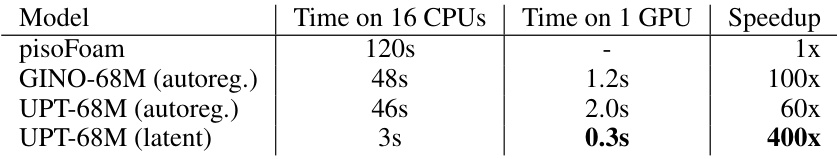

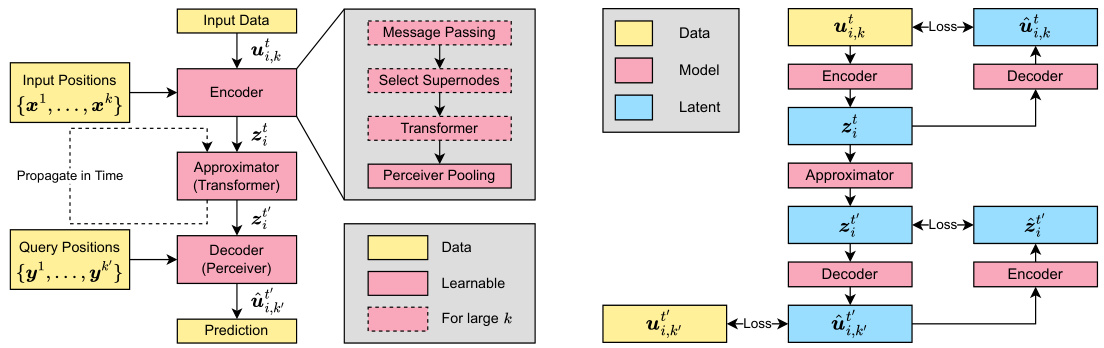

This figure illustrates the Universal Physics Transformer (UPT) learning process. UPTs handle both grid-based and particle-based data by encoding them into a fixed-size latent space. The dynamics are then efficiently propagated within this latent space before being decoded at any desired query point in space and time. This approach allows for scalability to larger and more complex simulations.

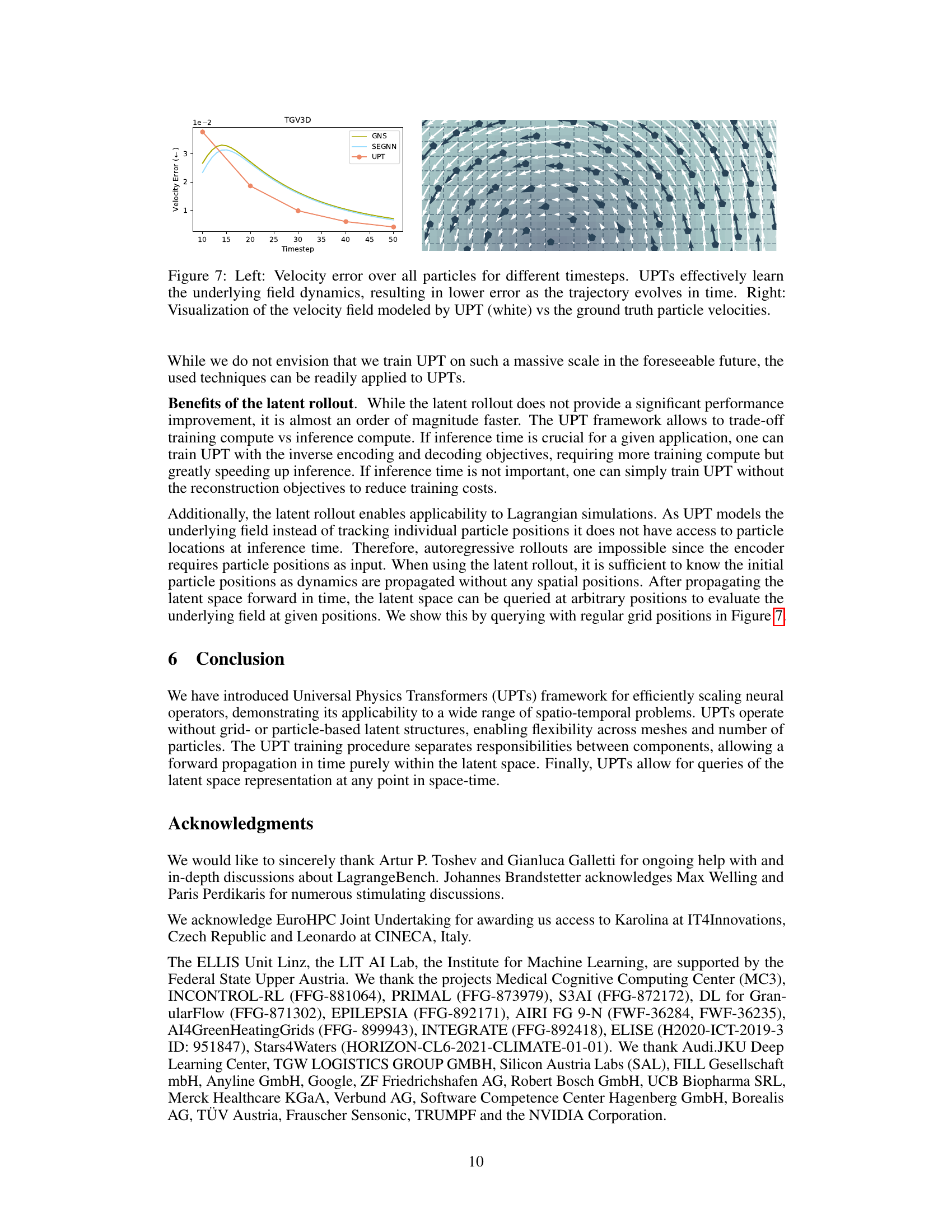

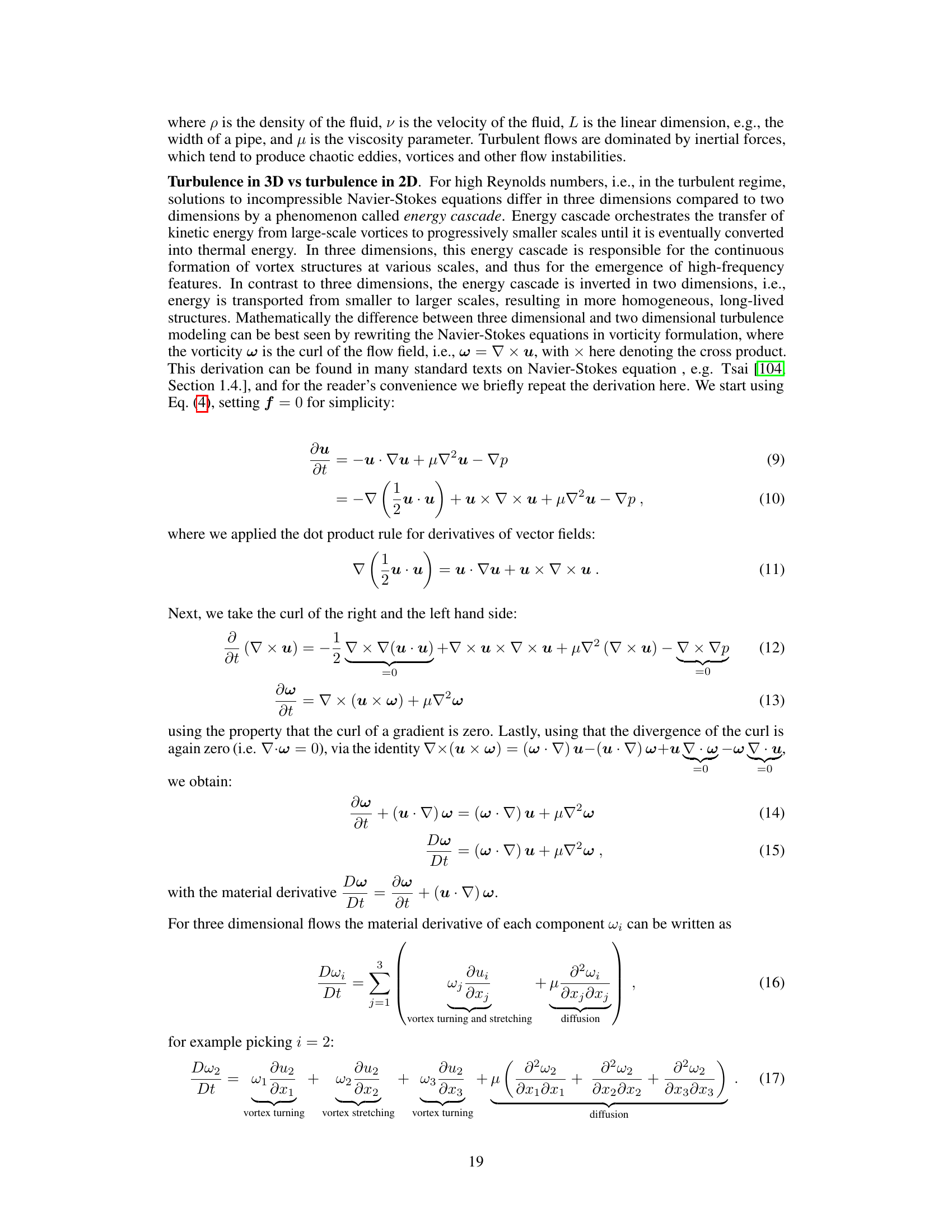

This table compares the time required to simulate a full trajectory rollout using different methods: pisoFoam (a traditional finite volume solver), GINO-68M (autoregressive), UPT-68M (autoregressive), and UPT-68M (latent). It highlights the significant speedup achieved by UPTs, especially when using the latent rollout technique. The speedup is shown for both CPU and GPU computation, demonstrating the efficiency gains offered by the neural surrogate models compared to the traditional approach.

In-depth insights#

UPT Framework#

The Universal Physics Transformers (UPT) framework presents a novel approach to neural operator learning, emphasizing scalability and efficiency across diverse spatio-temporal problems. Unlike traditional methods, UPTs avoid grid- or particle-based latent structures, handling both Eulerian and Lagrangian simulations seamlessly. The core innovation lies in a three-stage architecture: an encoder that compresses input data into a fixed-size latent space, regardless of the input’s representation, a transformer-based approximator that efficiently propagates dynamics within this latent space, and a decoder that allows querying the latent space at any point in space-time. This design enables scalability to large-scale simulations and fast inference via latent rollouts. Inverse encoding and decoding schemes further enhance the model’s stability and efficiency. The UPT framework demonstrates its effectiveness across diverse applications, showcasing the power of a unified approach to modeling complex physical phenomena.

Latent Space Dynamics#

The concept of ‘Latent Space Dynamics’ in the context of a research paper likely refers to how the internal representations (latent space) of a model evolve over time. This is crucial for understanding how the model learns and generalizes, especially in time-dependent problems. Effective latent space dynamics require careful design of both the encoding and decoding processes, enabling efficient and accurate transformation between the input space and the latent space. A key aspect is the ability to propagate information efficiently within the latent space, thus avoiding the computationally expensive mapping to and from the input space at every timestep. This efficient propagation may be achieved using methods such as recurrent neural networks or transformers. The dimensionality of the latent space is a critical factor influencing scalability and computational efficiency. The ideal latent space should be compact enough to allow fast computation but large enough to capture the essential information of the data and its dynamics. Furthermore, effective visualization and interpretation of latent space dynamics is paramount for understanding model behaviour and for debugging and improving model performance. The research paper likely demonstrates the efficacy of latent space dynamics through experiments that evaluate the model’s ability to predict future states, capturing transient behavior and generalizing well across different data regimes. Overall, a deep investigation into latent space dynamics is essential for developing robust and scalable models capable of handling complex time-evolving phenomena.

Scalability & Efficiency#

Analyzing the scalability and efficiency of a system requires a multifaceted approach. Computational cost, including memory and runtime, is paramount. The paper should detail the scaling behavior of the system as the size of the input data grows. Algorithm complexity is crucial; linear scaling is ideal, while exponential scaling signals potential limitations. Generalization ability is also important—does the model maintain high accuracy on unseen data or different problem instances? Resource utilization (CPU/GPU usage, memory footprint) should be quantified to show how efficiently the resources are being used. Finally, comparison to existing methods is key to demonstrating superiority or identifying competitive advantages. A thorough analysis of these factors provides a complete picture of the system’s scalability and efficiency.

Diverse Applications#

A hypothetical research paper section titled ‘Diverse Applications’ would explore the versatility of a presented method or model across various domains. This section’s strength lies in demonstrating the generalizability and robustness of the proposed approach beyond a niche application. High-quality diverse applications showcase the method’s adaptability to different data types, problem formulations, and computational environments. A strong presentation might include real-world applications such as those in computational fluid dynamics, weather prediction, or materials science, comparing performance against existing state-of-the-art techniques. The key is to present a range of applications that vary significantly in their characteristics while still highlighting the consistent effectiveness of the method, showcasing not just functionality but also a practical impact across diverse scientific and engineering fields. A compelling narrative connecting the diverse applications is essential, linking them conceptually rather than presenting them as isolated examples. Ultimately, this section aims to solidify the method’s potential and establish its broader usefulness in the scientific community.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this paper on Universal Physics Transformers (UPTs) could significantly advance scientific computing. Extending UPTs beyond fluid dynamics, to other domains such as plasma physics, weather modeling, or material science, is a key area. Improving the latent rollout mechanism, perhaps by adapting techniques from diffusion models, would enhance efficiency. Developing methods to handle large-scale Lagrangian simulations efficiently remains a challenge, necessitating the creation of substantial datasets for training and testing. A particularly interesting avenue is combining Lagrangian and Eulerian simulations within a unified framework, harnessing the strengths of both approaches. Finally, exploration of extreme-scale training techniques, inspired by the success of large language models, promises to unlock the potential of UPTs for solving truly massive-scale scientific problems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

The figure qualitatively explores the scaling limits of different neural operator architectures when the number of input points increases. Models with compressed latent spaces (like GINO and UPT) significantly outperform models without such compression (GNNs and Transformers) in terms of memory usage as the number of input points grows. However, GINO’s reliance on regular grids limits its scalability in 3D. UPT offers the best scalability due to its efficient latent space compression.

The figure illustrates the Universal Physics Transformer (UPT) architecture and training process. The left panel shows the UPT’s workflow: encoding data from various sources (grids or particles) into a fixed-size latent space, propagating the dynamics within the latent space using a transformer approximator, and decoding the results to obtain predictions at arbitrary query locations. The right panel details the training procedure, highlighting the use of inverse encoding and decoding losses to learn the encoding and decoding functions and allow for efficient latent space rollouts. This setup is crucial for efficiently handling large-scale simulations because it avoids the computational cost of working directly with high-dimensional spatial data.

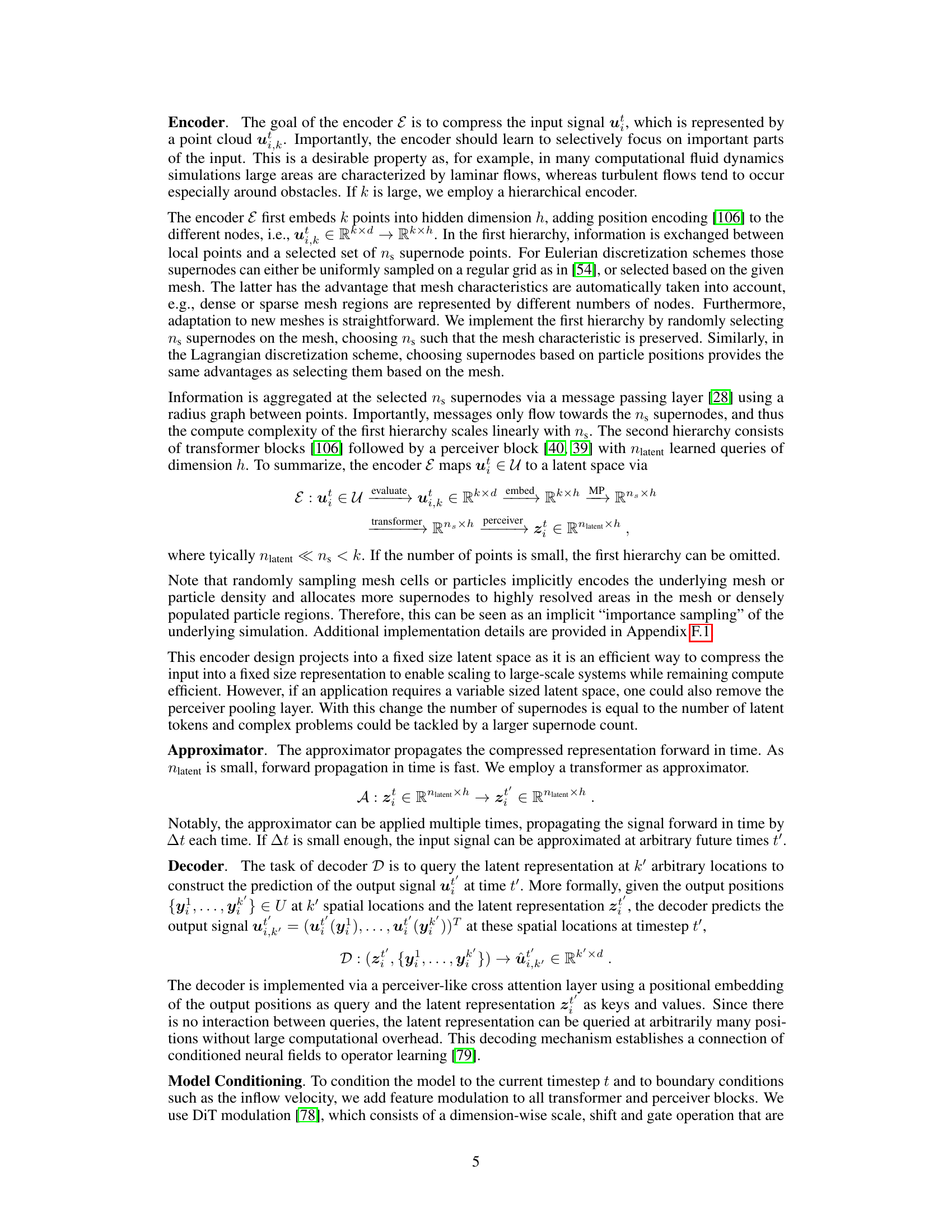

This figure shows example rollout trajectories of the Universal Physics Transformer (UPT) model, highlighting its ability to simulate physical phenomena accurately across different simulation settings. The UPT model was trained on datasets with varying obstacles, flow conditions, and mesh resolutions, demonstrating its robustness and generalization capabilities. While the absolute error may appear to indicate divergence in some instances, closer examination reveals that the discrepancies originate from small, gradual shifts in predictions over time, possibly resulting from the model’s point-wise decoding of the latent field representation.

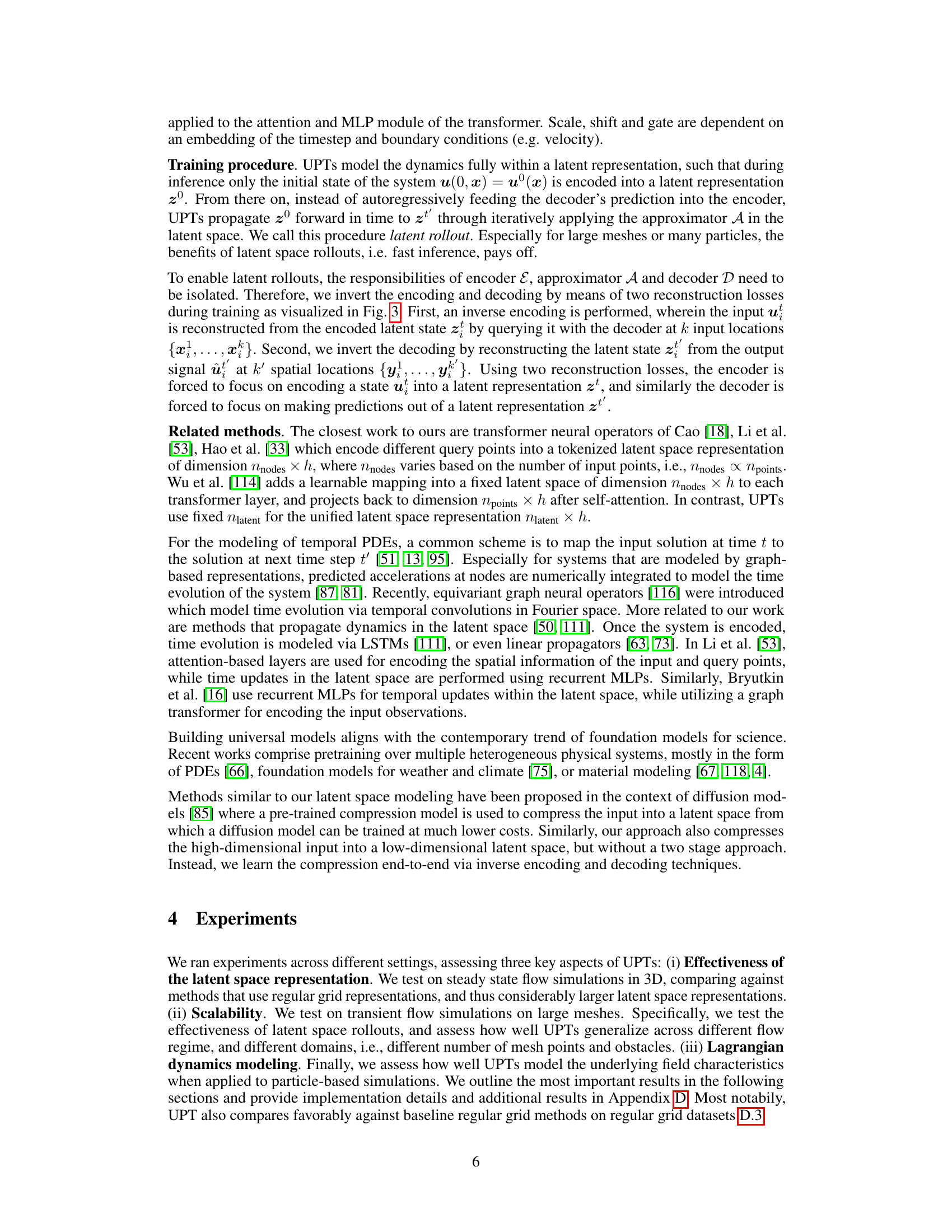

This figure presents a comparison of UPTs against other methods across different model sizes and input/output data points. The left and center plots show that UPTs consistently outperform other methods in terms of Mean Squared Error (MSE) and correlation time. The right plot demonstrates the impact of varying the number of input/output points, showing the stable and robust performance of UPTs across different resolutions.

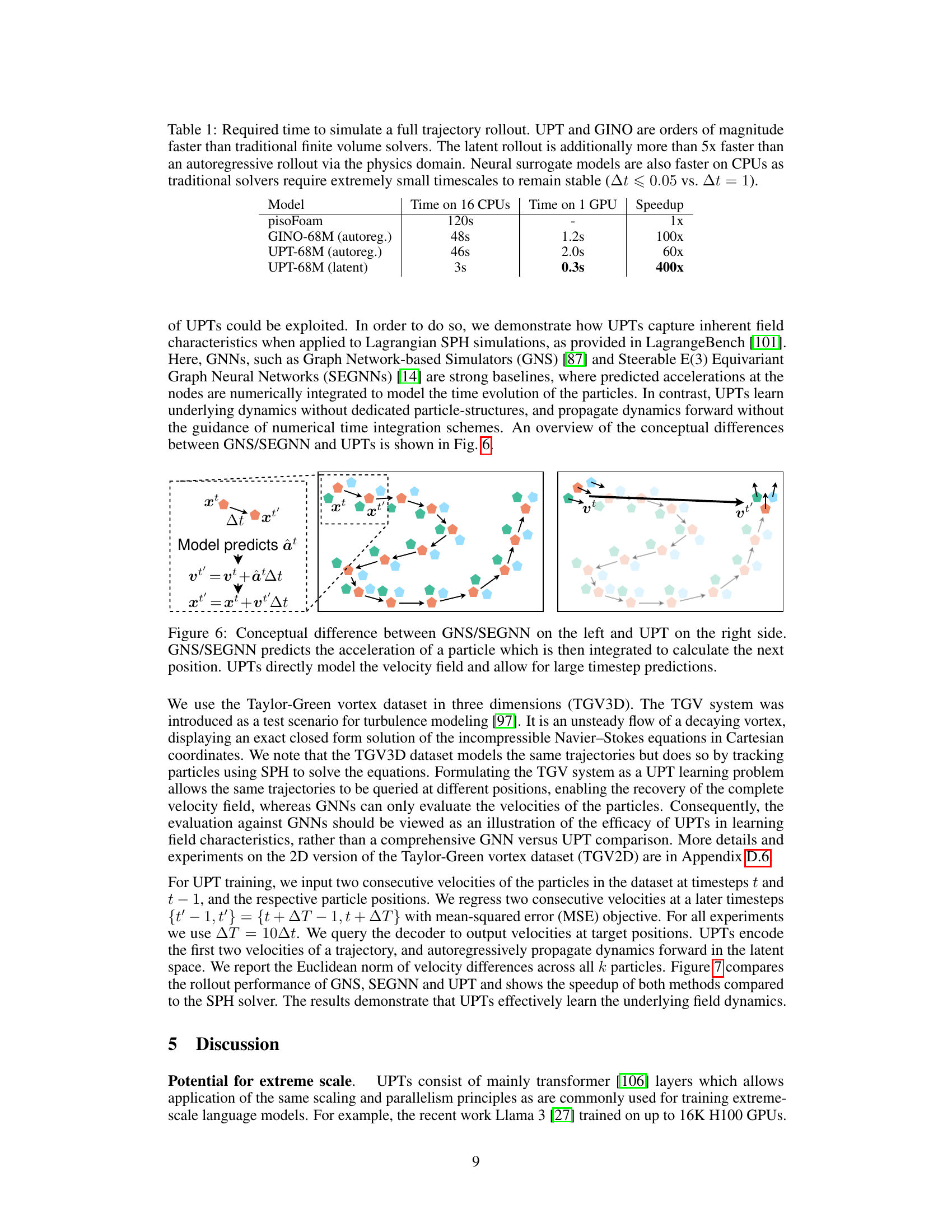

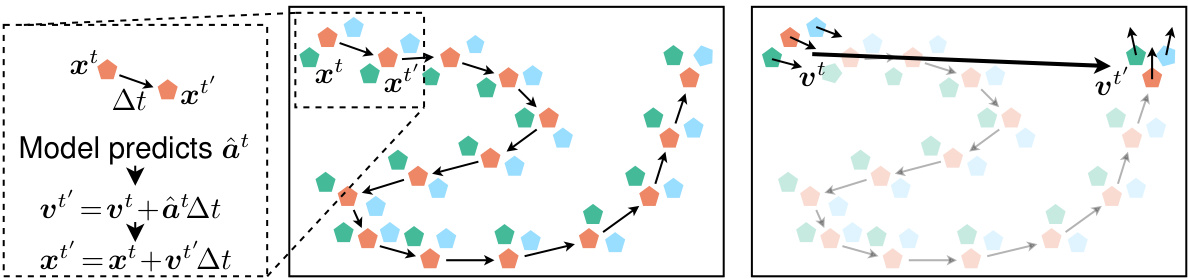

This figure illustrates the core difference between Graph Neural Network-based simulators (GNS) and Steerable E(3) Equivariant Graph Neural Networks (SEGNN), and Universal Physics Transformers (UPTs). GNS and SEGNN predict particle acceleration, which is then numerically integrated to find the next position. This process requires small timesteps. In contrast, UPTs model the entire velocity field, making larger timesteps possible. The figure depicts particle trajectories to show how the UPT approach handles the dynamics more directly.

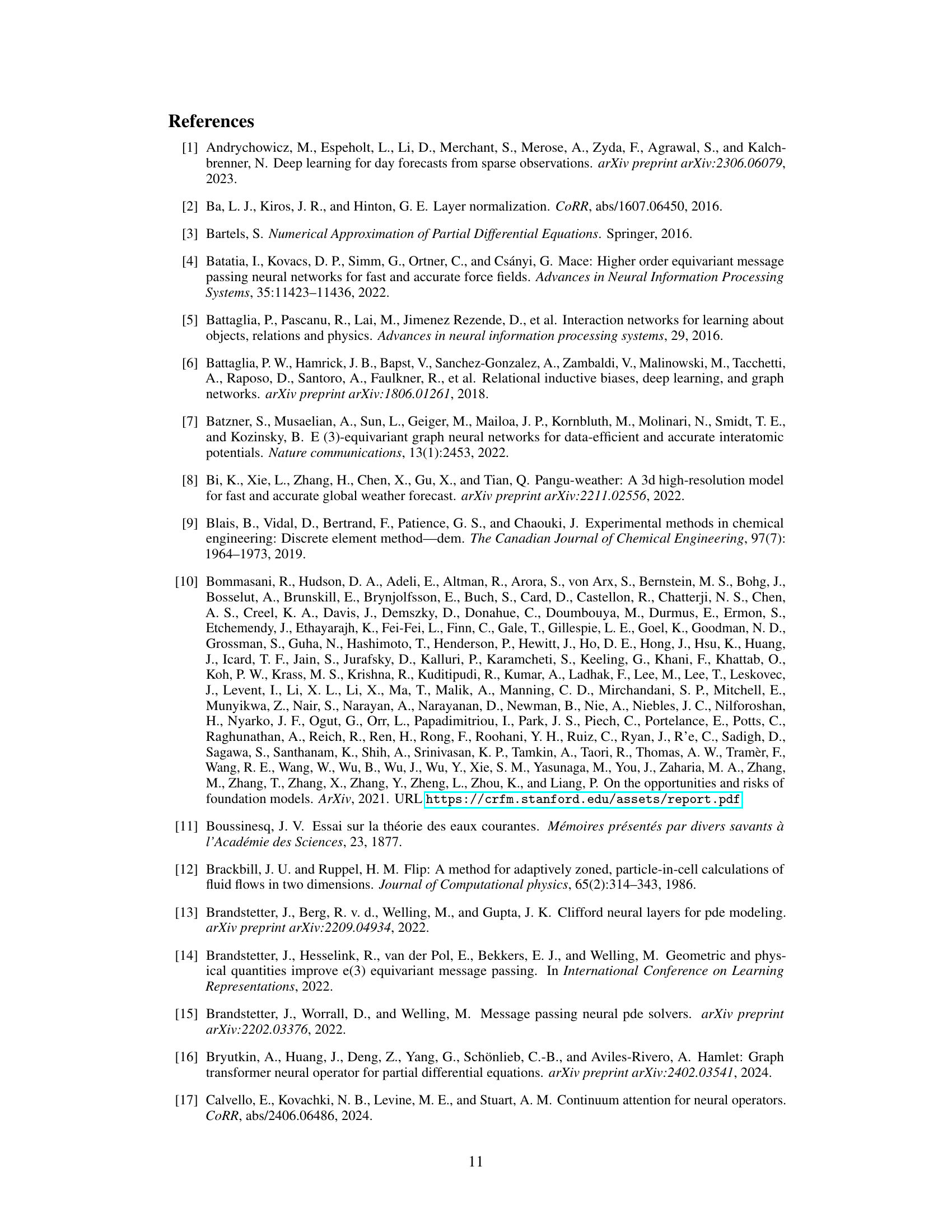

This figure shows the comparison between the UPT model and other methods (GNS and SEGNN) for predicting particle velocities in a Lagrangian fluid dynamics simulation. The left panel displays a line graph showing the mean Euclidean norm of the velocity error over all particles across different timesteps. The right panel provides a visual comparison of the velocity field predicted by the UPT model and the ground truth particle velocities. The visualizations are given as quiver plots of the velocity vector fields.

The figure qualitatively shows the scaling limits of various neural operators for increasing input sizes. Models with compressed latent space representations (GINO and UPT) scale much better than those without (GNN and Transformer). GINO’s scaling advantage is lost in 3D due to its reliance on regular grids. UPT exhibits the best scalability, handling up to 4.2 million points.

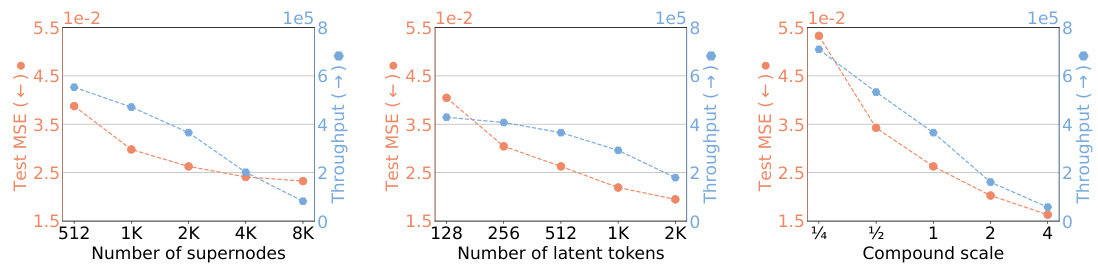

This figure shows the results of an experiment investigating the impact of scaling the latent space size on the performance of a 17M parameter UPT model. Three different scaling experiments are performed: increasing the number of supernodes, increasing the number of latent tokens, and scaling both simultaneously (compound scaling). The results are presented in terms of test MSE and throughput (samples processed per GPU hour). The experiment was conducted with a reduced training setting of 10 epochs and 16,000 input points.

This figure compares the performance of Universal Physics Transformers (UPTs) and Geometry-Informed Neural Operators (GINOs) across different model sizes on a specific task. It demonstrates that UPTs achieve better performance (lower test MSE) with significantly fewer parameters than GINOs. This highlights the superior expressivity and efficiency of the UPT architecture.

This figure shows the scalability and data efficiency of UPTs. The model was trained on subsets of the data used for the transient flow experiments (2K and 4K out of the 8K training simulations). The results demonstrate that UPTs achieve comparable performance to GINO-8M with only a quarter of the data, highlighting its data efficiency.

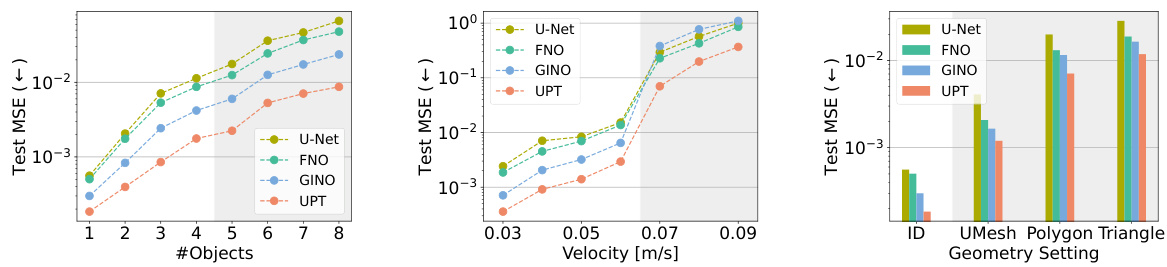

This figure shows the out-of-distribution generalization capabilities of the 68M parameter models trained on the transient flow dataset. The left panel shows results when increasing the number of obstacles; the center panel increases the inflow velocity; and the right panel compares the results across different mesh geometries (uniform mesh, triangles, and polygons). UPTs show a strong performance across all OOD (out-of-distribution) scenarios.

This figure shows example rollout trajectories from the UPT-68M model. Each row represents a different simulation, showcasing the model’s ability to handle various obstacle configurations, flow regimes, and mesh discretizations. The leftmost column displays the ground truth, while subsequent columns show model predictions at different timesteps. The absolute error is also depicted, highlighting subtle prediction shifts that occur over time despite the model successfully simulating the overall physics. The figure emphasizes the UPTs flexibility and robustness in various situations.

The left plot shows the velocity error of the UPT model over time, showcasing its ability to accurately learn and simulate the underlying field dynamics. The right plot compares the runtime performance of UPT against SPH, SEGNN, and GNS for simulating a TGV2D trajectory. UPT demonstrates significantly faster simulation times.

More on tables

This table presents a comparison of the performance of Universal Physics Transformers (UPTs) against other state-of-the-art models on a regular grid Navier-Stokes dataset. The comparison is done for both small and large model sizes, highlighting the scalability and performance advantages of UPTs.

This table compares the performance of UPT-S against several other models on the regular gridded small-scale Shallow Water-2D dataset. The table shows that UPT-S achieves a lower relative L2 error than the other models, demonstrating its effectiveness even on datasets for which other models were specifically designed.

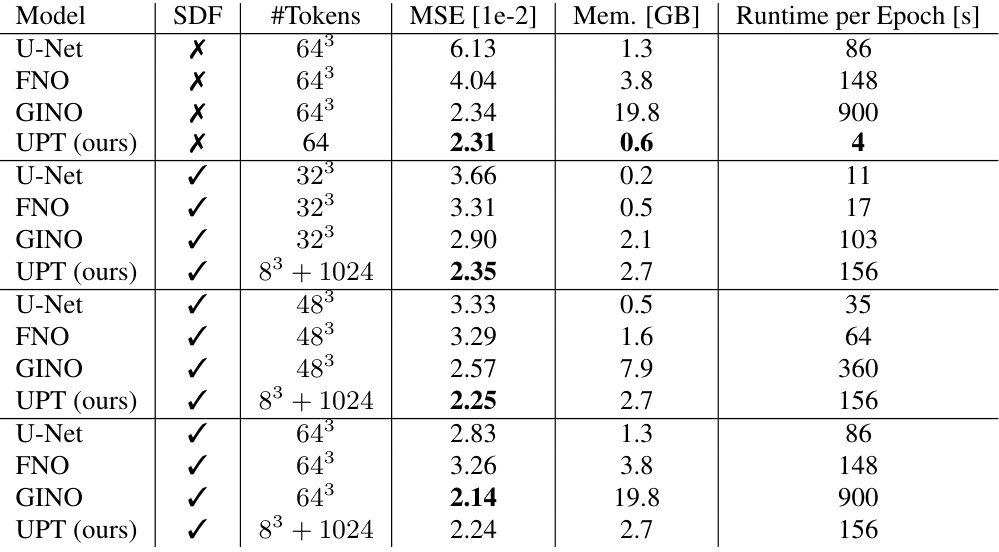

This table presents the results of ShapeNet-Car pressure prediction experiments. It compares different models (U-Net, FNO, GINO, and UPT) in terms of their Mean Squared Error (MSE), memory usage, and runtime per epoch. The table also shows results with and without using Signed Distance Function (SDF) features as input to the UPT model.

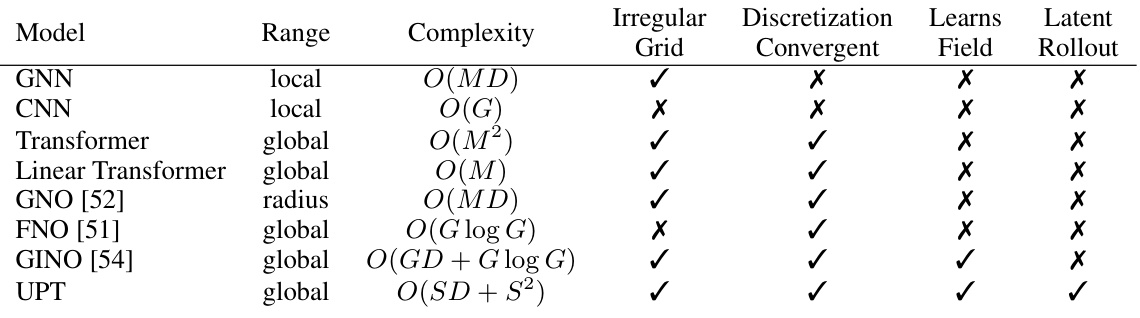

This table extends Figure 2 by adding a column for theoretical complexity analysis of different neural operator models (GNN, CNN, Transformer, Linear Transformer, GNO, FNO, GINO, and UPT). It also includes columns indicating whether each model uses a regular grid, produces discretization-convergent results, learns the underlying field, and performs latent rollout for efficient scaling. The complexity analysis considers the number of mesh points (M), graph degree (D), number of grid points (G), and number of supernodes (S).

Full paper#