TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) are increasingly used as decision-making agents; however, their ability to explore, a key aspect of reinforcement learning, remains unclear. This paper investigates whether LLMs can effectively explore in simple multi-armed bandit environments without explicit training. The study examined several LLMs, prompt designs, and environments to understand the extent to which in-context learning supports exploration.

The researchers found that only one configuration, using GPT-4, chain-of-thought reasoning, and an externally summarized history, led to satisfactory exploration. Other configurations, even with chain-of-thought, failed to consistently explore, highlighting the importance of appropriate prompt design and potential limitations in LLMs’ intrinsic exploratory abilities. These findings emphasize the need for further research into empowering LLMs for robust and reliable exploration in more complex decision-making scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges the assumption that large language models (LLMs) inherently possess strong exploratory capabilities, a critical aspect for effective decision-making in complex environments. The findings highlight the need for algorithmic improvements in LLMs for robust exploration and decision-making, opening new avenues for research and development in AI. The implications extend to various AI applications that require intelligent decision-making agents.

Visual Insights#

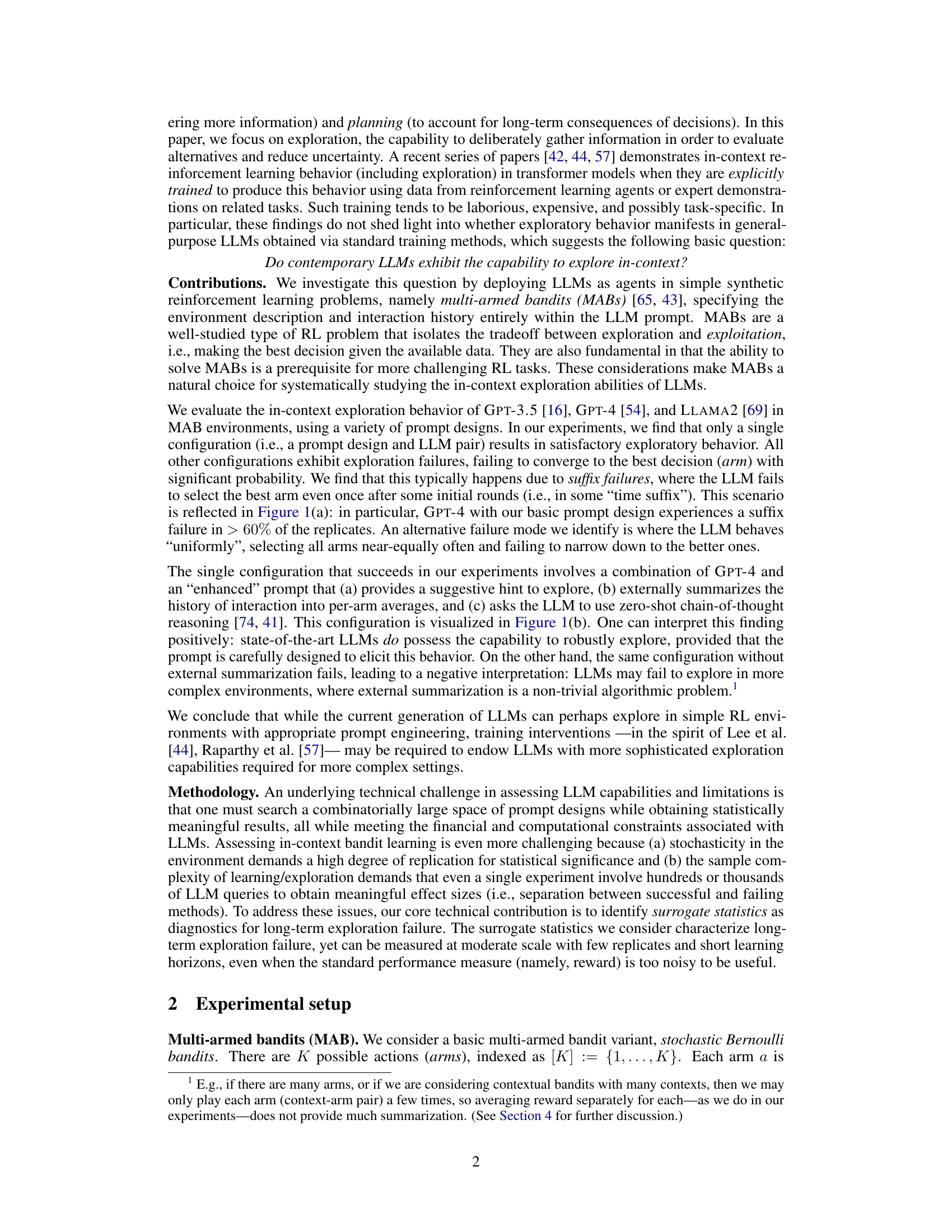

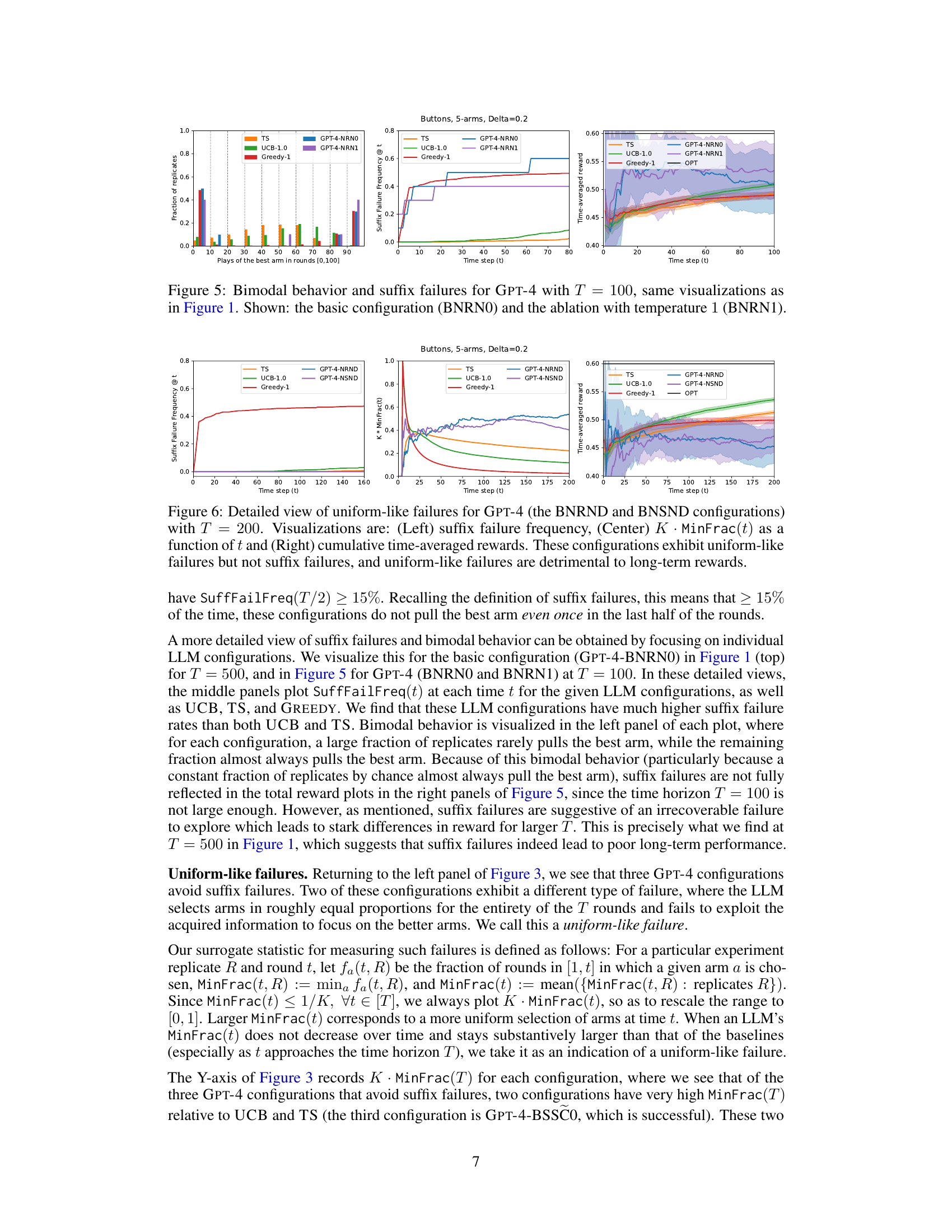

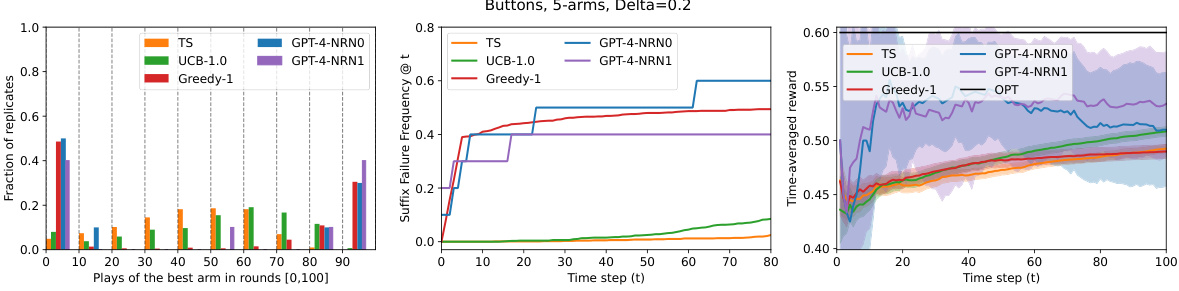

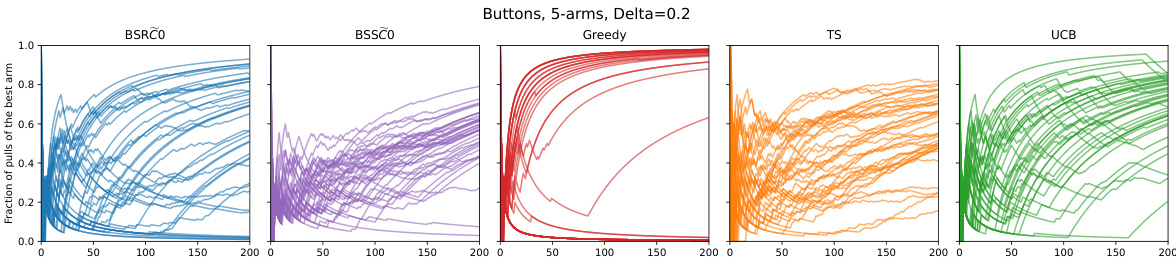

🔼 This figure presents the results of two experiments using GPT-4 in a 5-armed bandit setting. The top row shows an experiment where GPT-4 fails to explore effectively, exhibiting behavior similar to a greedy algorithm. The bottom row shows a successful exploration experiment where GPT-4, with a modified prompt, converges to the optimal arm. The figure uses three visualizations: histograms showing how many times the best arm was chosen across multiple trials, plots of the suffix failure frequency (how often the best arm was never chosen after a certain point), and plots of the cumulative reward across trials. This demonstrates the impact of prompt engineering on exploration capability of LLMs.

read the caption

Figure 1: Representative experiments: Two prompt configurations for GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem, with exploration failure (top) and success (bottom). The baselines are two standard bandit algorithms with performance guarantees, Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) and Thompson Sampling (TS), as well as the GREEDY algorithm (see Footnote 5). Visualizations are: (Left) histogram over replicates of the number of times the best arm is chosen, (Center) for each t, we plot the suffix failure frequency, the fraction of replicates for which the best arm is never chosen after time-step t, and (Right) cumulative time-averaged rewards, averaged over replicates (±2 standard errors).

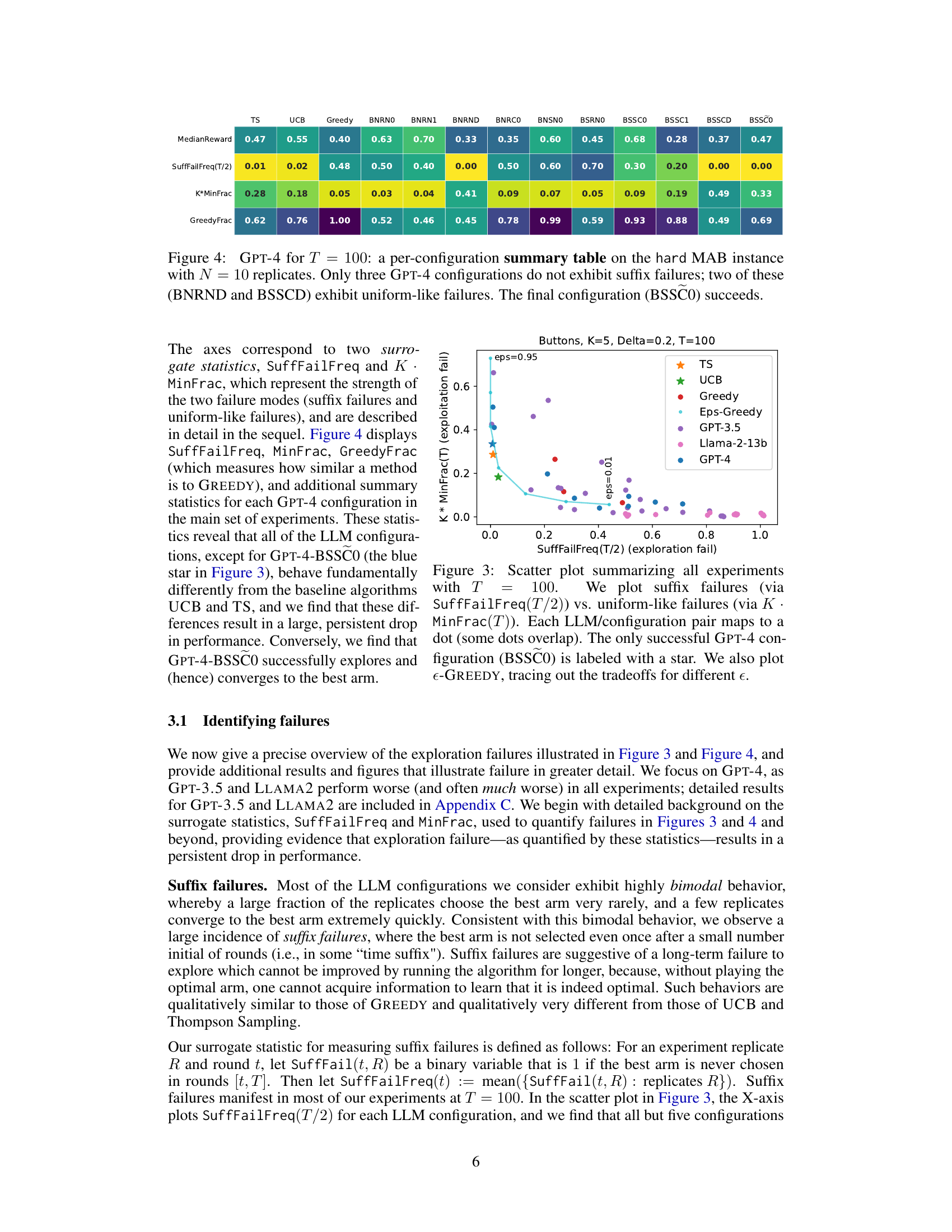

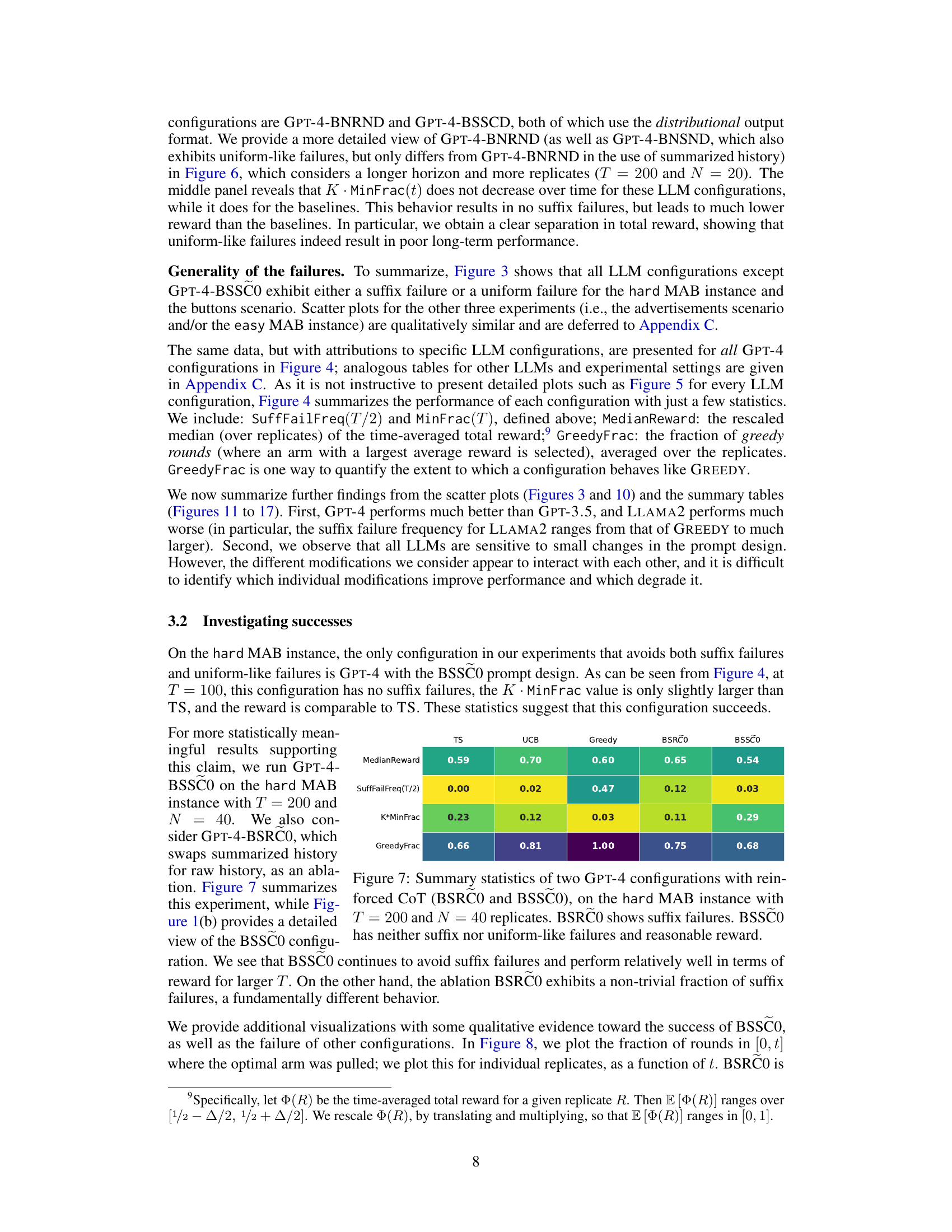

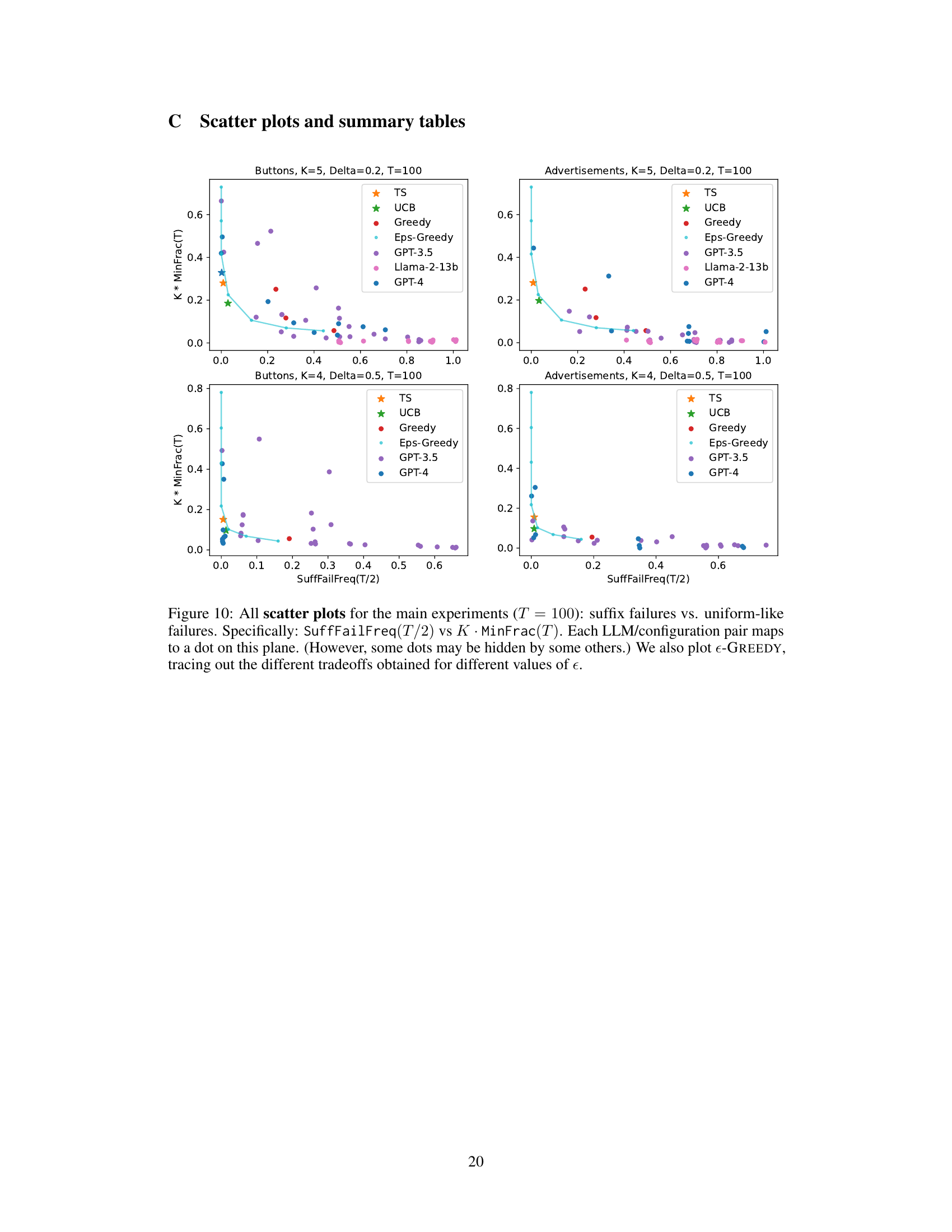

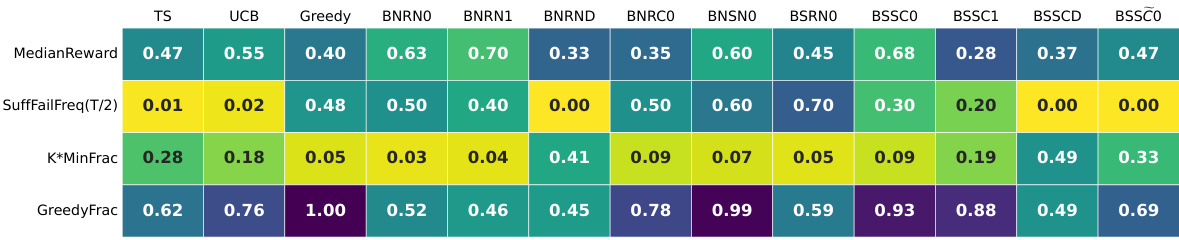

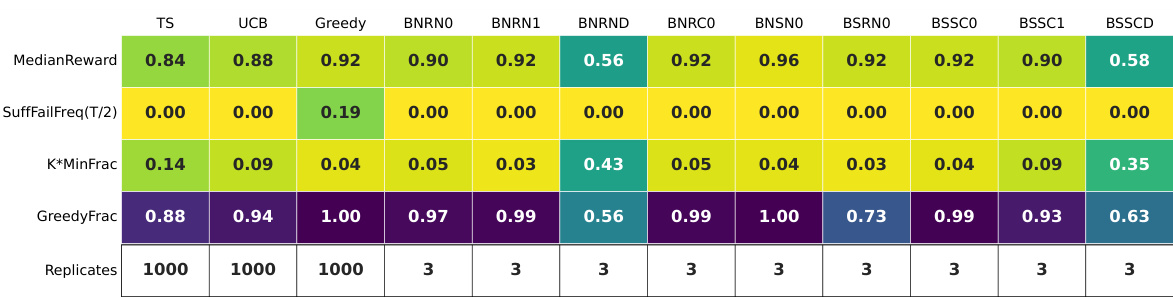

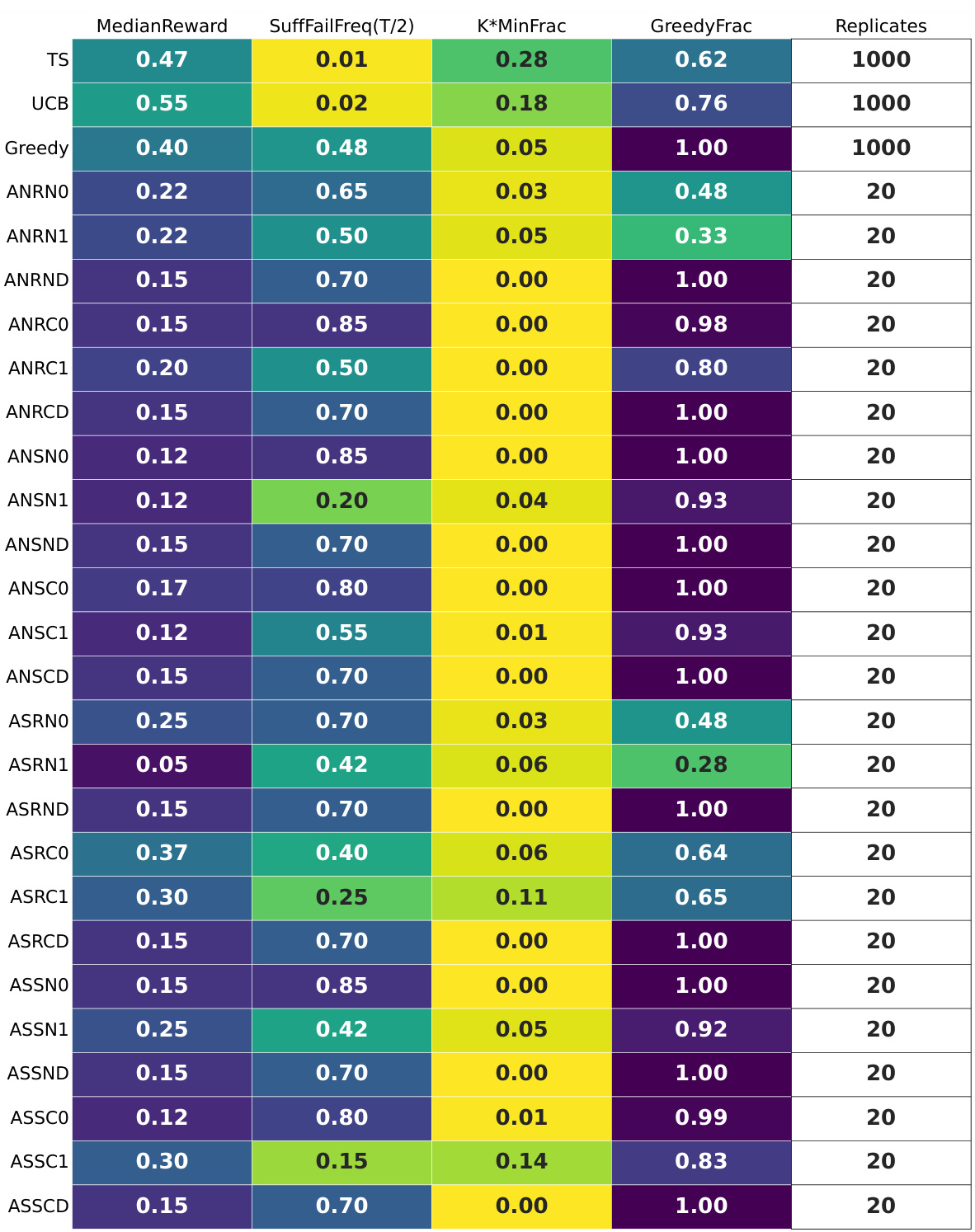

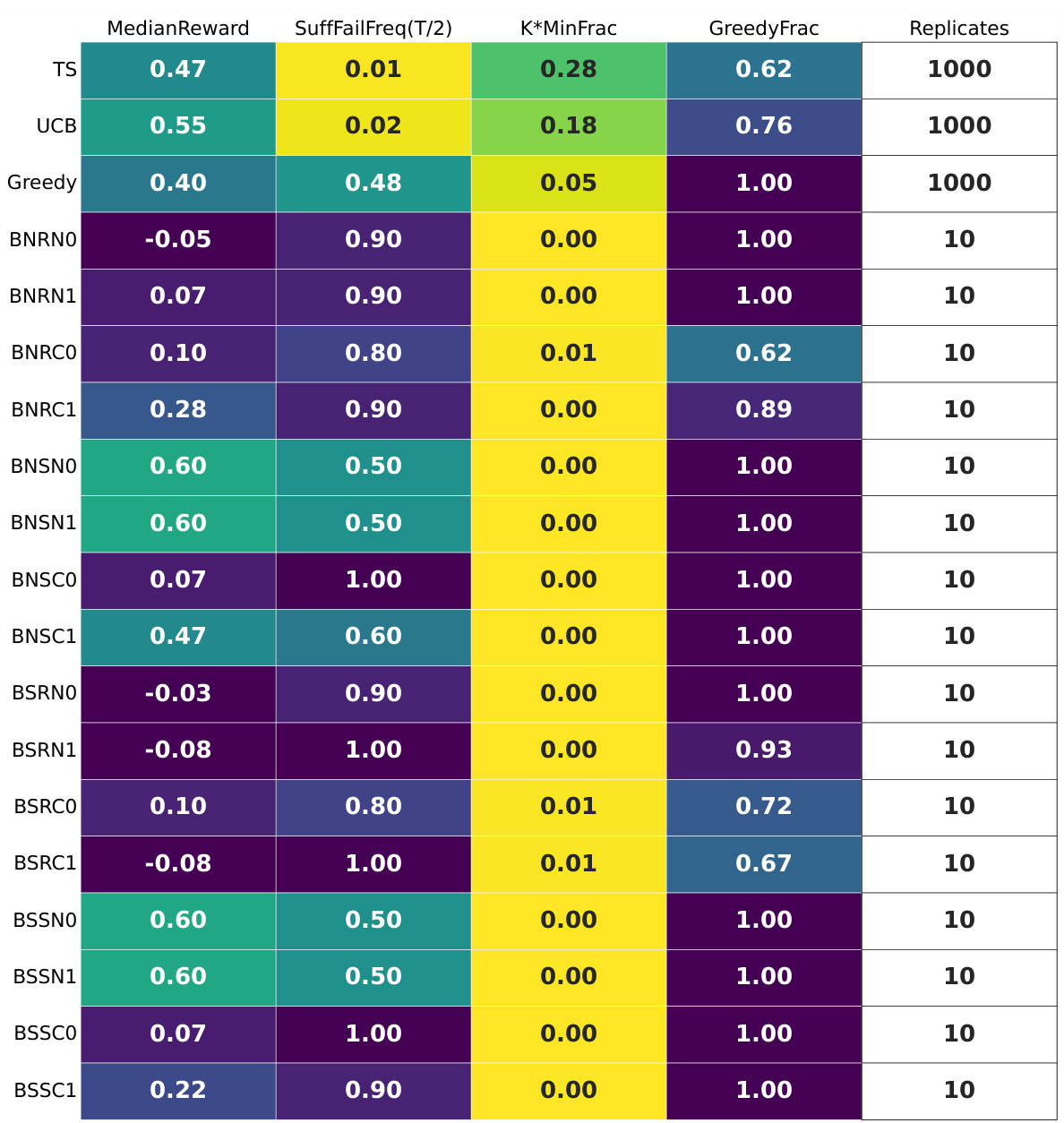

🔼 This table summarizes the results of experiments using GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem with a reward gap of 0.2 (hard instance). It shows several key statistics for 12 different prompt configurations. The statistics include the median reward achieved, the suffix failure frequency (the percentage of times the best arm was not chosen after the midpoint of the trial), and the minimum fraction of times each arm was played (K * MinFrac). The table highlights the only successful configuration which avoided both suffix failures and uniform-like failures.

read the caption

Figure 4: GPT-4 for T = 100: a per-configuration summary table on the hard MAB instance with N = 10 replicates. Only three GPT-4 configurations do not exhibit suffix failures; two of these (BNRND and BSSCD) exhibit uniform-like failures. The final configuration (BSSCO) succeeds.

In-depth insights#

LLM Exploration#

The investigation into LLM exploration reveals a complex interplay between model capabilities and prompt engineering. While state-of-the-art LLMs demonstrate a capacity for exploration under specific, carefully crafted prompts (highlighting the importance of prompt engineering), they do not robustly explore in simpler settings. This suggests that intrinsic exploration abilities in LLMs are limited and require substantial external interventions, such as summarization of interaction history, to elicit desirable behavior. The reliance on such interventions indicates a crucial gap in current LLMs and points to a need for more sophisticated algorithms or training methods to enable exploration in complex scenarios. The findings challenge the notion of LLMs as general-purpose decision-making agents and emphasize the significant engineering required to bridge the gap between theoretical capabilities and robust, reliable performance. External interventions, while helpful, might not scale to complex problems, underscoring a fundamental research challenge in advancing LLM-based decision making agents.

Prompt Engineering#

Prompt engineering plays a crucial role in directing the capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs). Careful crafting of prompts is essential to elicit desired behavior, especially in complex tasks that demand exploration or reasoning. The paper highlights that even with state-of-the-art LLMs, simple prompts often fail to yield robust exploratory behavior in multi-armed bandit settings, underscoring the need for more sophisticated prompt designs. Strategies such as incorporating chain-of-thought reasoning and externally summarized interaction histories can significantly improve LLM performance, but these techniques may not generalize well to more complex environments. Therefore, prompt engineering is not a substitute for algorithmic improvements, and future research should explore advanced methods for prompting and training LLMs to improve their decision-making capabilities.

MAB Experiments#

The section on “MAB Experiments” would detail the empirical setup and results of using multi-armed bandit (MAB) problems to assess the exploration capabilities of large language models (LLMs). The core would involve describing the specific MAB environments used, such as the number of arms, reward distributions, and the gap between the best and other arms. Different prompt designs would be outlined, explaining how the environment description and interaction history were presented to the LLMs. The choice of LLMs (GPT-3.5, GPT-4, LLaMa 2) and their configurations would be justified, including temperature settings, chain-of-thought prompting, and history summarization techniques. The results section would present key performance metrics comparing LLM performance to standard bandit algorithms (e.g., UCB, Thompson Sampling, Greedy). Key findings regarding the success or failure of LLMs to exhibit exploration behavior would be highlighted, potentially discussing suffix failures (failure to select the best arm once it is known) and uniform-like failures (selecting all arms equally), and analyzing their root causes. Finally, the limitations and implications of the experimental design would be discussed, acknowledging issues like computational cost and scale, and the need for further research.

Exploration Failures#

The study reveals that Large Language Models (LLMs) frequently fail to explore effectively in multi-armed bandit tasks, a fundamental aspect of reinforcement learning. These exploration failures manifest primarily as suffix failures, where the models fail to select the optimal arm even after numerous opportunities, and uniform failures, where they select arms with near-equal probability, hindering convergence to the best option. Prompt engineering, while helpful in isolated instances, does not consistently resolve these issues. This suggests that algorithmic improvements, perhaps involving training adjustments or architectural changes, are crucial for enabling LLMs to reliably perform exploration in more complex scenarios. The inability to generalize exploratory behavior across different prompt designs underscores the need for more robust exploration capabilities within LLMs themselves.

Future of ICRL#

The future of in-context reinforcement learning (ICRL) is bright but challenging. Significant advancements are needed to address current limitations, including the unreliability of exploration without significant prompt engineering or fine-tuning, and the difficulty of scaling ICRL to complex environments where external summarization of interaction history is impractical. Future research should explore innovative prompting strategies, investigate the use of auxiliary tools to augment LLM capabilities, and develop new algorithms designed to efficiently manage the exploration-exploitation tradeoff. Addressing computational limitations associated with LLMs will also be critical for progress. The potential rewards are substantial, however; successful ICRL could lead to highly adaptable and efficient AI agents capable of operating effectively in a wide range of real-world settings. Further theoretical understanding is necessary to fully grasp the underlying mechanisms of in-context learning and to guide the development of more robust and powerful ICRL techniques. Finally, careful consideration must be given to ethical implications as ICRL-based agents become increasingly sophisticated and capable of influencing real-world decisions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

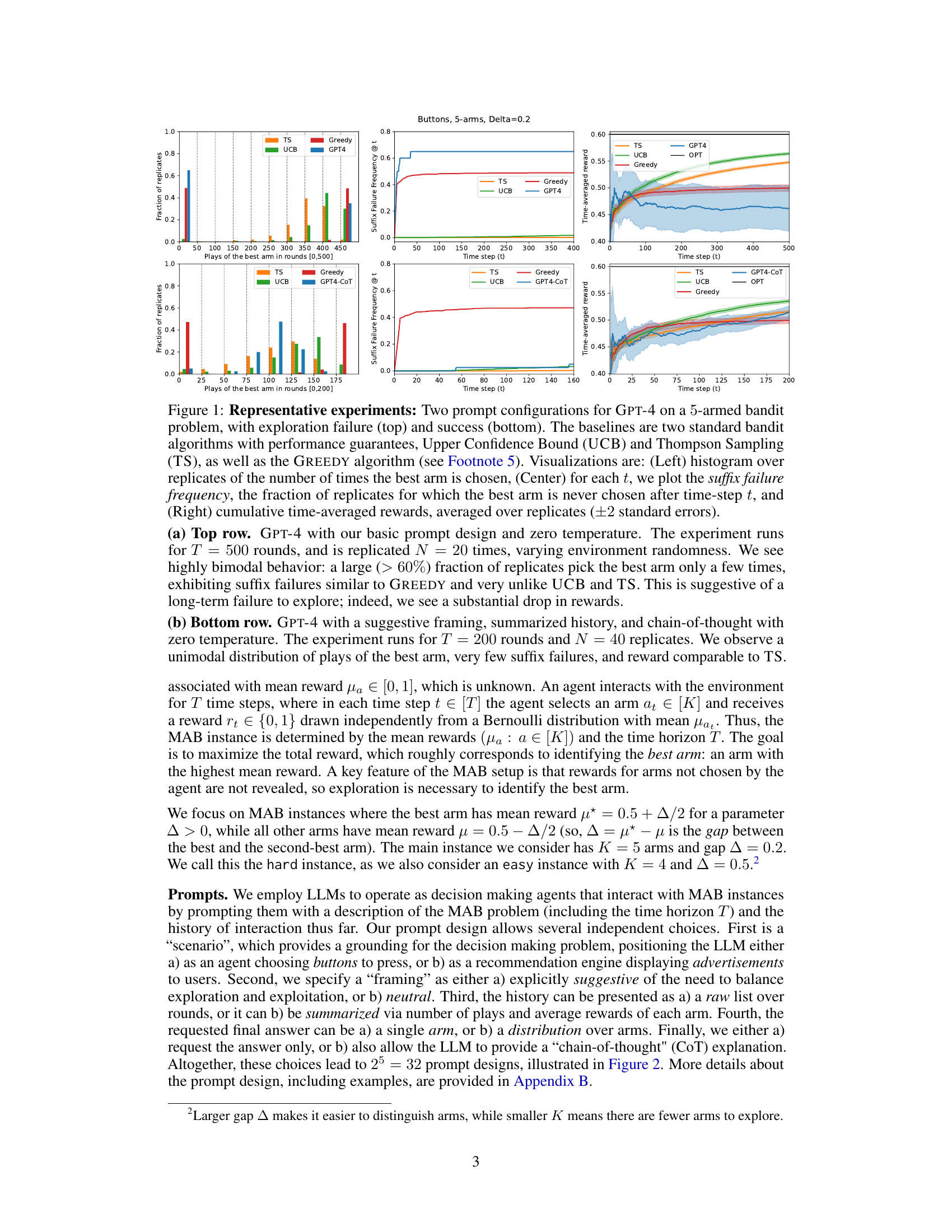

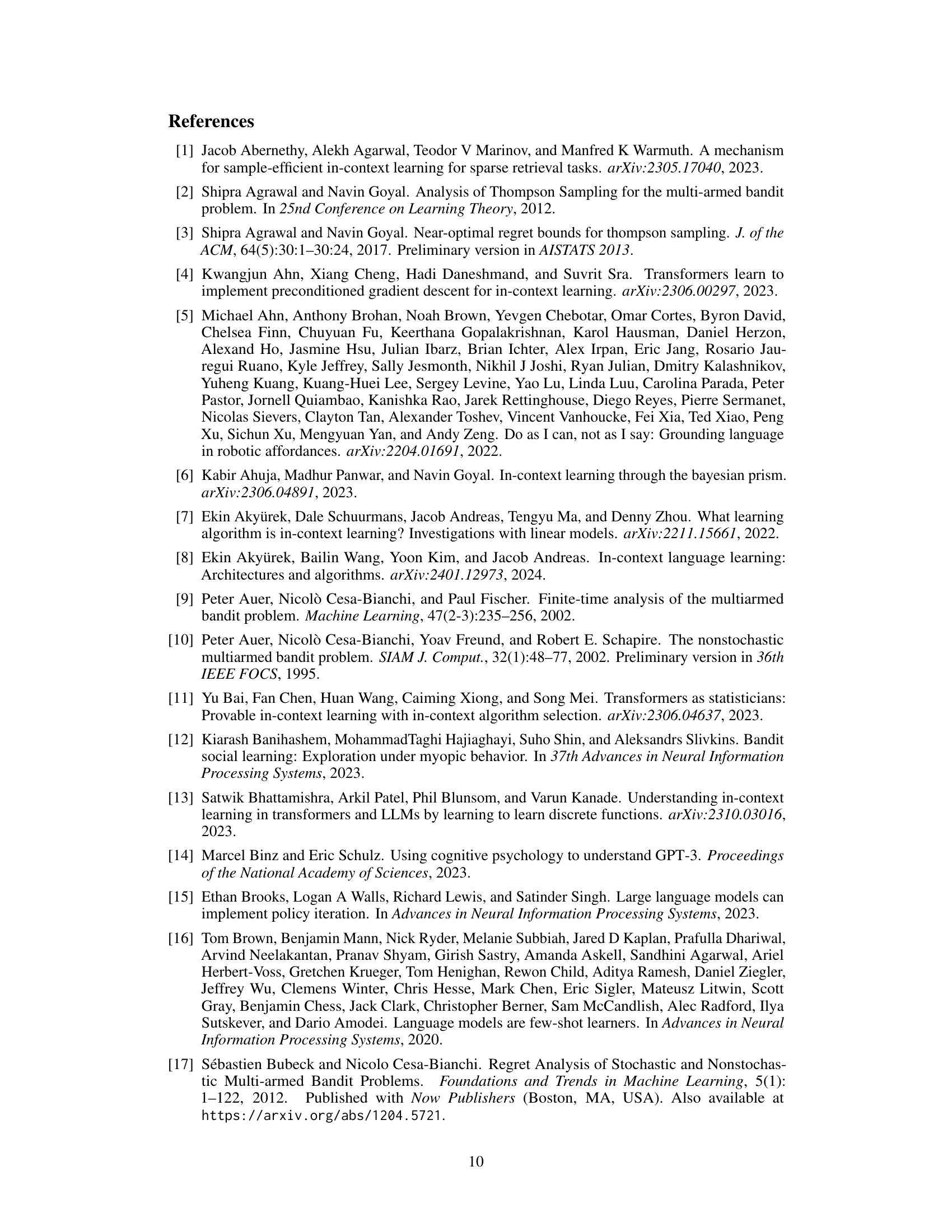

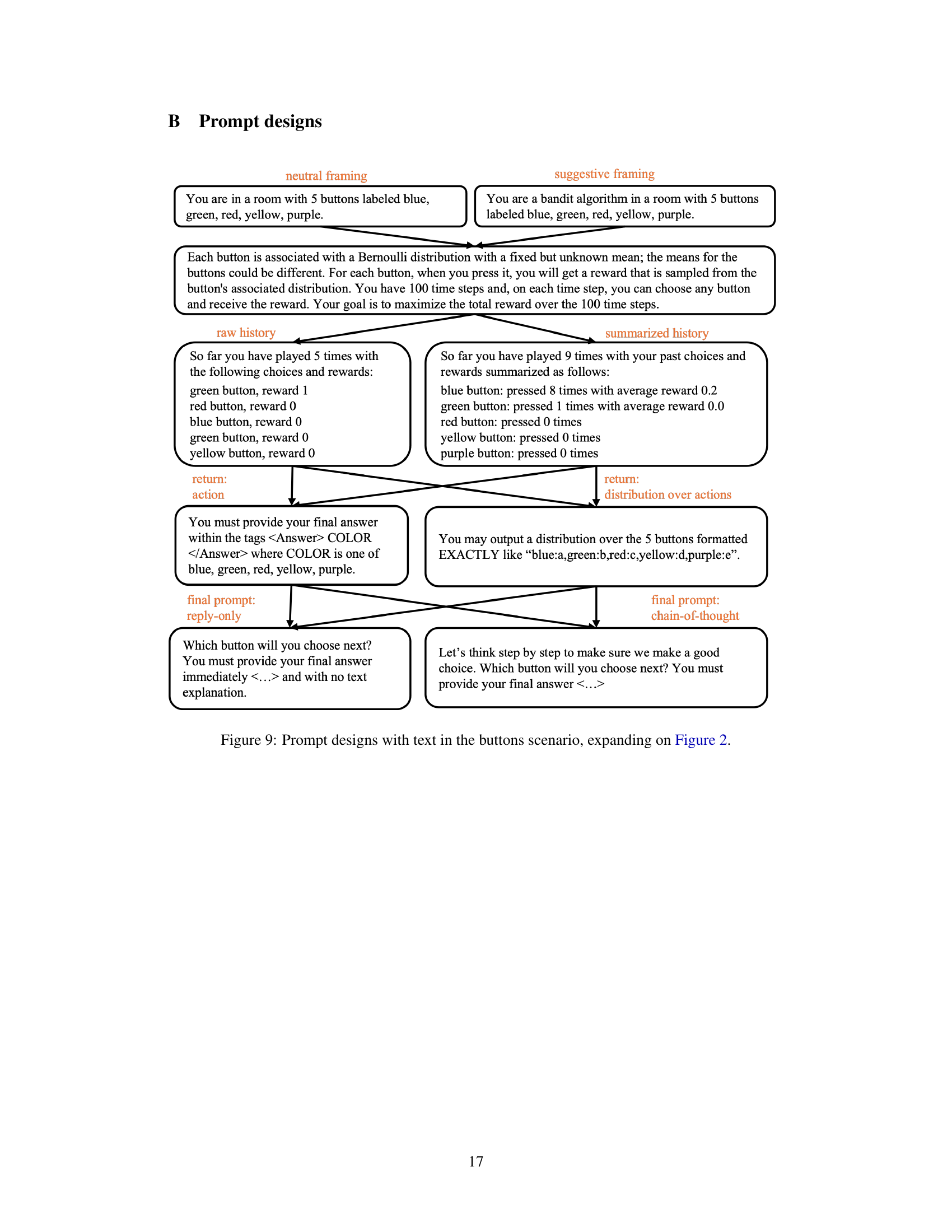

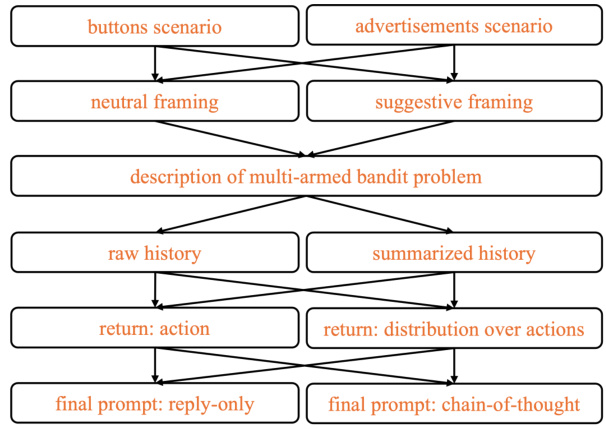

🔼 This figure is a graph that shows how the prompts are generated. The different prompt designs are created by combining elements such as scenarios (buttons or advertisements), framing (neutral or suggestive), history presentation (raw or summarized), return type (single action or distribution), and the inclusion of chain-of-thought reasoning. The figure shows the different options and how they combine to create a total of 32 different prompt designs. Figure 9 provides more detailed text examples of each.

read the caption

Figure 2: Prompt designs; see Figure 9 for a more detailed view. A prompt is generated by traversing the graph from top to bottom.

🔼 This figure displays the results of two experiments using GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem. The top row shows an experiment where GPT-4 fails to explore effectively, while the bottom row shows a successful exploration. Three different algorithms (Upper Confidence Bound, Thompson Sampling, and Greedy) are used as baselines for comparison. The left panel of each row is a histogram showing how often the best arm was selected, the center panel plots the frequency of ‘suffix failures’ (never choosing the best arm after a certain time step), and the right panel shows the time-averaged reward.

read the caption

Figure 1: Representative experiments: Two prompt configurations for GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem, with exploration failure (top) and success (bottom). The baselines are two standard bandit algorithms with performance guarantees, Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) and Thompson Sampling (TS), as well as the GREEDY algorithm (see Footnote 5). Visualizations are: (Left) histogram over replicates of the number of times the best arm is chosen, (Center) for each t, we plot the suffix failure frequency, the fraction of replicates for which the best arm is never chosen after time-step t, and (Right) cumulative time-averaged rewards, averaged over replicates (±2 standard errors).

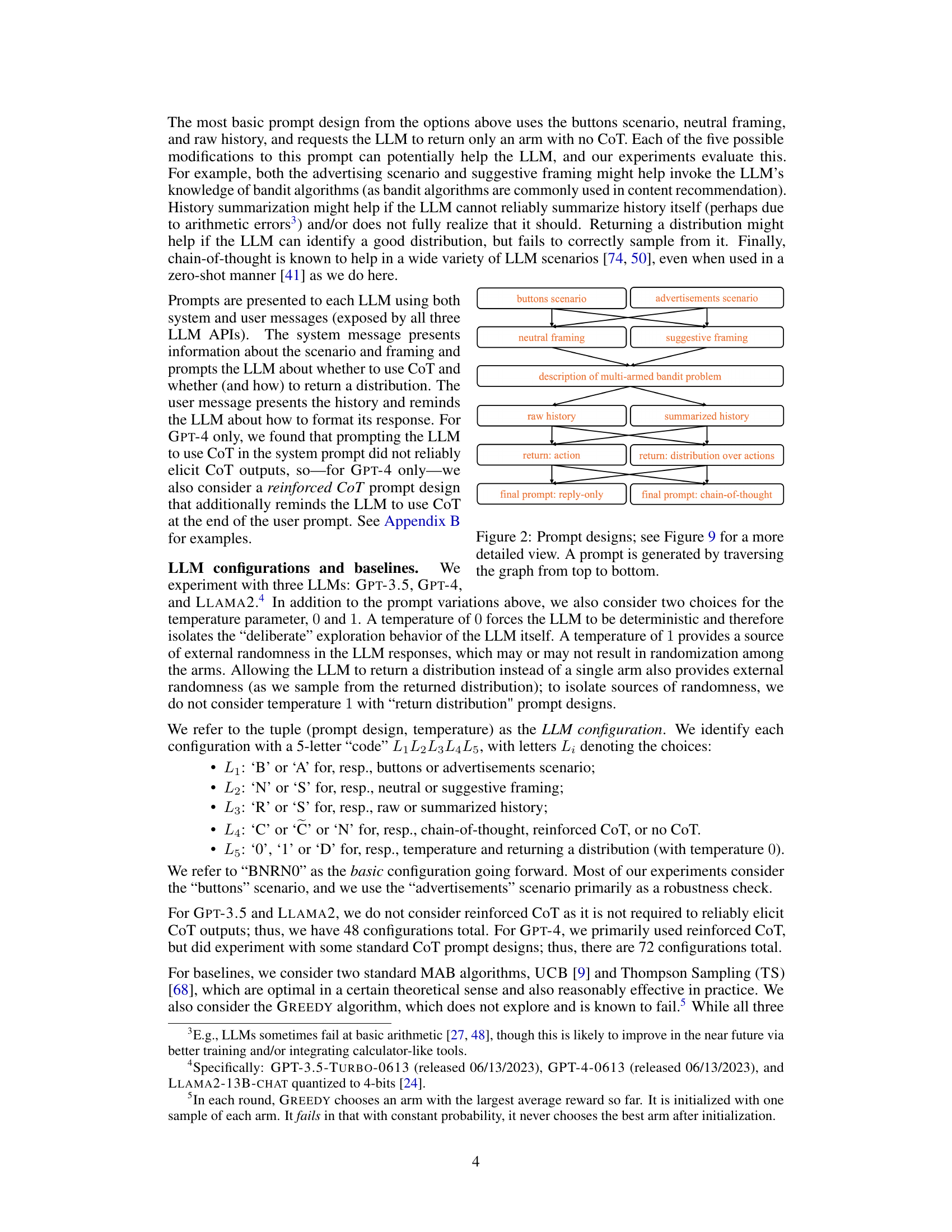

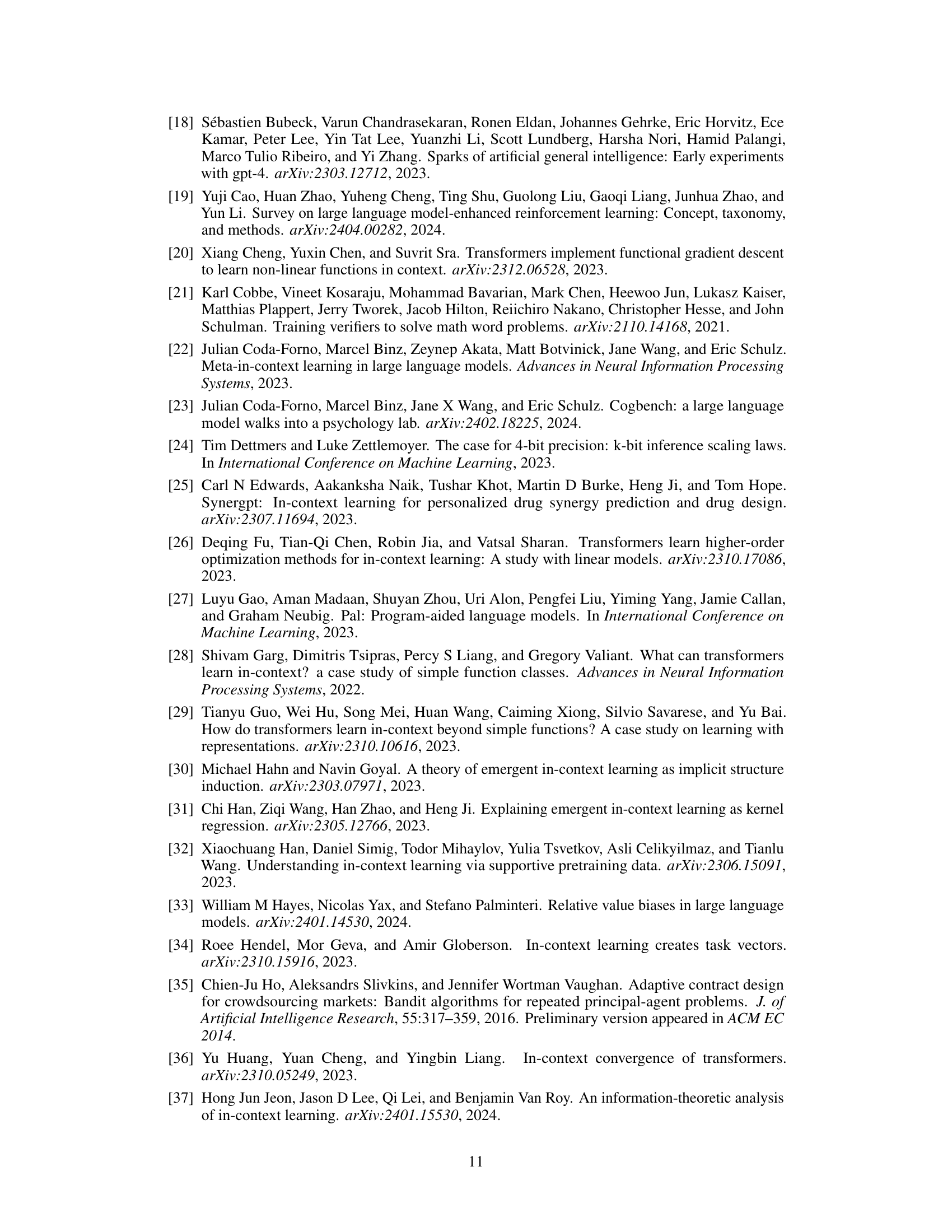

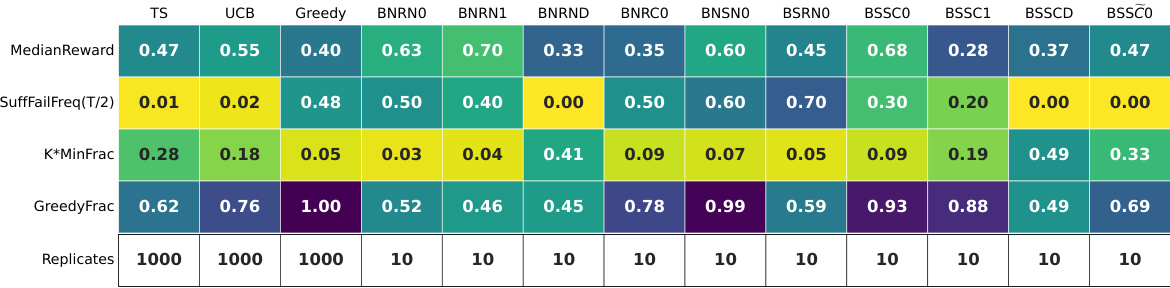

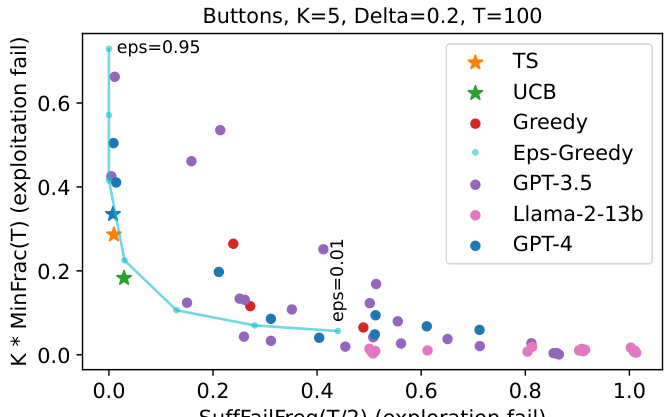

🔼 This scatter plot visualizes the results of experiments comparing different Large Language Models (LLMs) and configurations on a multi-armed bandit (MAB) problem. The x-axis represents the frequency of suffix failures (where the best arm is never chosen after a certain point), and the y-axis shows the frequency of uniform-like failures (where arms are chosen almost equally). Each point represents a specific LLM and prompt configuration. The plot reveals that most LLMs and configurations exhibit substantial exploration failures, failing to converge to the best arm. The successful GPT-4 configuration (BSSC0) is highlighted, demonstrating that successful exploration is possible but requires specific prompt engineering and LLM capabilities. The e-GREEDY baseline curve helps to contextualize the results.

read the caption

Figure 3: Scatter plot summarizing all experiments with T=100. We plot suffix failures (via SuffFailFreq(T/2)) vs. uniform-like failures (via K*MinFrac(T)). Each LLM/configuration pair maps to a dot (some dots overlap). The only successful GPT-4 configuration (BSSC0) is labeled with a star. We also plot e-GREEDY, tracing out the tradeoffs for different e.

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments using GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem. Two different prompt configurations are compared: one that leads to exploration failure and one that leads to success. The figure includes histograms showing how often the best arm was chosen, plots of suffix failure frequency (the percentage of times the best arm was never chosen after a certain point in time), and plots of cumulative average rewards. These are compared against three standard bandit algorithms (UCB, Thompson Sampling, and Greedy) to illustrate the success or failure of the GPT-4 configurations.

read the caption

Figure 1: Representative experiments: Two prompt configurations for GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem, with exploration failure (top) and success (bottom). The baselines are two standard bandit algorithms with performance guarantees, Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) and Thompson Sampling (TS), as well as the GREEDY algorithm (see Footnote 5). Visualizations are: (Left) histogram over replicates of the number of times the best arm is chosen, (Center) for each t, we plot the suffix failure frequency, the fraction of replicates for which the best arm is never chosen after time-step t, and (Right) cumulative time-averaged rewards, averaged over replicates (±2 standard errors).

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments comparing GPT-4’s performance on a 5-armed bandit problem with two different prompt configurations and three baseline algorithms (UCB, TS, and GREEDY). The top row displays an exploration failure, while the bottom row shows a successful exploration. The visualizations include histograms of best arm selections, suffix failure frequencies, and cumulative time-averaged rewards. The figure demonstrates the impact of prompt design on LLM exploration capabilities.

read the caption

Figure 1: Representative experiments: Two prompt configurations for GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem, with exploration failure (top) and success (bottom). The baselines are two standard bandit algorithms with performance guarantees, Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) and Thompson Sampling (TS), as well as the GREEDY algorithm (see Footnote 5). Visualizations are: (Left) histogram over replicates of the number of times the best arm is chosen, (Center) for each t, we plot the suffix failure frequency, the fraction of replicates for which the best arm is never chosen after time-step t, and (Right) cumulative time-averaged rewards, averaged over replicates (±2 standard errors).

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments comparing GPT-4’s performance on a 5-armed bandit problem with two different prompt configurations. The top row demonstrates exploration failure, while the bottom row shows successful exploration. The figure uses histograms to show the number of times the best arm was selected across multiple trials, plots showing the frequency of ‘suffix failures’ (where the best arm is never selected after a certain point in time), and graphs of cumulative time-averaged rewards. These visualizations allow for a comparison of GPT-4’s performance against standard bandit algorithms such as UCB, Thompson Sampling, and a greedy algorithm.

read the caption

Figure 1: Representative experiments: Two prompt configurations for GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem, with exploration failure (top) and success (bottom). The baselines are two standard bandit algorithms with performance guarantees, Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) and Thompson Sampling (TS), as well as the GREEDY algorithm (see Footnote 5). Visualizations are: (Left) histogram over replicates of the number of times the best arm is chosen, (Center) for each t, we plot the suffix failure frequency, the fraction of replicates for which the best arm is never chosen after time-step t, and (Right) cumulative time-averaged rewards, averaged over replicates (±2 standard errors).

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments comparing GPT-4’s performance in a 5-armed bandit problem with two different prompt configurations. The top row illustrates a case of exploration failure, where GPT-4 fails to consistently select the best arm, mirroring the performance of a greedy algorithm. The bottom row shows a successful exploration, where GPT-4, aided by a more informative prompt, exhibits performance comparable to optimal bandit algorithms like UCB and Thompson Sampling. The visualizations include histograms of best-arm selections, suffix failure frequency, and time-averaged rewards, providing a comprehensive view of the model’s exploration behavior under different conditions.

read the caption

Figure 1: Representative experiments: Two prompt configurations for GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem, with exploration failure (top) and success (bottom). The baselines are two standard bandit algorithms with performance guarantees, Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) and Thompson Sampling (TS), as well as the GREEDY algorithm (see Footnote 5). Visualizations are: (Left) histogram over replicates of the number of times the best arm is chosen, (Center) for each t, we plot the suffix failure frequency, the fraction of replicates for which the best arm is never chosen after time-step t, and (Right) cumulative time-averaged rewards, averaged over replicates (±2 standard errors).

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments comparing GPT-4’s performance on a 5-armed bandit problem with two different prompt configurations. The top row demonstrates an exploration failure where the model does not consistently select the best arm. The bottom row illustrates successful exploration, showing the model successfully converging to the optimal arm. The figure includes histograms showing the number of times the best arm is chosen, plots of the suffix failure frequency, and plots of the cumulative time-averaged rewards for both the GPT-4 configurations and for baseline bandit algorithms (UCB, Thompson Sampling, and Greedy).

read the caption

Figure 1: Representative experiments: Two prompt configurations for GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem, with exploration failure (top) and success (bottom). The baselines are two standard bandit algorithms with performance guarantees, Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) and Thompson Sampling (TS), as well as the GREEDY algorithm (see Footnote 5). Visualizations are: (Left) histogram over replicates of the number of times the best arm is chosen, (Center) for each t, we plot the suffix failure frequency, the fraction of replicates for which the best arm is never chosen after time-step t, and (Right) cumulative time-averaged rewards, averaged over replicates (±2 standard errors).

🔼 This figure displays the results of two experiments using GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem. The top row shows an experiment where GPT-4 fails to explore effectively, while the bottom row shows an experiment where GPT-4 successfully explores. The figure compares GPT-4’s performance to three baseline algorithms: Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), Thompson Sampling (TS), and a greedy algorithm. Three visualizations are provided for each experiment: a histogram showing the number of times the best arm was chosen across multiple trials, a plot of the suffix failure frequency (the probability of never selecting the best arm after a certain point in time), and a plot of the cumulative time-averaged rewards.

read the caption

Figure 1: Representative experiments: Two prompt configurations for GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem, with exploration failure (top) and success (bottom). The baselines are two standard bandit algorithms with performance guarantees, Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) and Thompson Sampling (TS), as well as the GREEDY algorithm (see Footnote 5). Visualizations are: (Left) histogram over replicates of the number of times the best arm is chosen, (Center) for each t, we plot the suffix failure frequency, the fraction of replicates for which the best arm is never chosen after time-step t, and (Right) cumulative time-averaged rewards, averaged over replicates (±2 standard errors).

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments comparing GPT-4’s performance on a 5-armed bandit problem with two different prompt configurations. One configuration resulted in exploration failure, while the other was successful. The figure presents three visualizations for each configuration: a histogram showing the number of times the best arm was chosen across multiple repetitions of the experiment, a plot of the suffix failure frequency (the proportion of trials where the best arm was never chosen after a certain point), and a plot showing the cumulative time-averaged rewards. These results highlight the impact of prompt design on the LLM’s ability to explore effectively.

read the caption

Figure 1: Representative experiments: Two prompt configurations for GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem, with exploration failure (top) and success (bottom). The baselines are two standard bandit algorithms with performance guarantees, Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) and Thompson Sampling (TS), as well as the GREEDY algorithm (see Footnote 5). Visualizations are: (Left) histogram over replicates of the number of times the best arm is chosen, (Center) for each t, we plot the suffix failure frequency, the fraction of replicates for which the best arm is never chosen after time-step t, and (Right) cumulative time-averaged rewards, averaged over replicates (±2 standard errors).

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments using GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem. The top row shows an exploration failure, where the model does not consistently choose the best arm. The bottom row shows successful exploration with a modified prompt. Histograms illustrate the number of times the best arm was chosen, while plots show suffix failure frequency and cumulative reward, comparing GPT-4’s performance to standard bandit algorithms (UCB, TS, and Greedy).

read the caption

Figure 1: Representative experiments: Two prompt configurations for GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem, with exploration failure (top) and success (bottom). The baselines are two standard bandit algorithms with performance guarantees, Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) and Thompson Sampling (TS), as well as the GREEDY algorithm (see Footnote 5). Visualizations are: (Left) histogram over replicates of the number of times the best arm is chosen, (Center) for each t, we plot the suffix failure frequency, the fraction of replicates for which the best arm is never chosen after time-step t, and (Right) cumulative time-averaged rewards, averaged over replicates (±2 standard errors).

🔼 This figure presents a comparison of exploration performance between GPT-4 with different prompt configurations and standard bandit algorithms (UCB, TS, and Greedy) in a 5-armed bandit problem. The top row shows an exploration failure, where GPT-4 rarely selects the best arm, while the bottom row illustrates successful exploration, reaching comparable performance to the baseline algorithms. Three visualizations are provided for each scenario to show the distribution of best arm selections, the frequency of suffix failures (where the best arm is never chosen after a certain point), and the cumulative average rewards.

read the caption

Figure 1: Representative experiments: Two prompt configurations for GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem, with exploration failure (top) and success (bottom). The baselines are two standard bandit algorithms with performance guarantees, Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) and Thompson Sampling (TS), as well as the GREEDY algorithm (see Footnote 5). Visualizations are: (Left) histogram over replicates of the number of times the best arm is chosen, (Center) for each t, we plot the suffix failure frequency, the fraction of replicates for which the best arm is never chosen after time-step t, and (Right) cumulative time-averaged rewards, averaged over replicates (±2 standard errors).

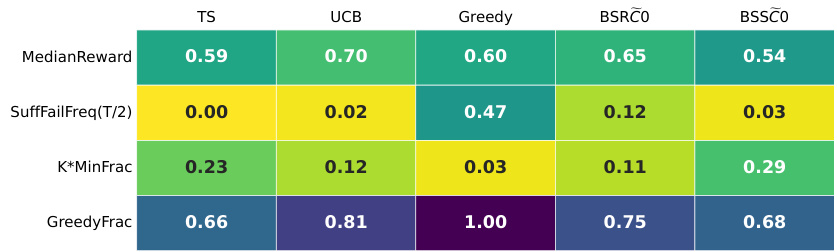

More on tables

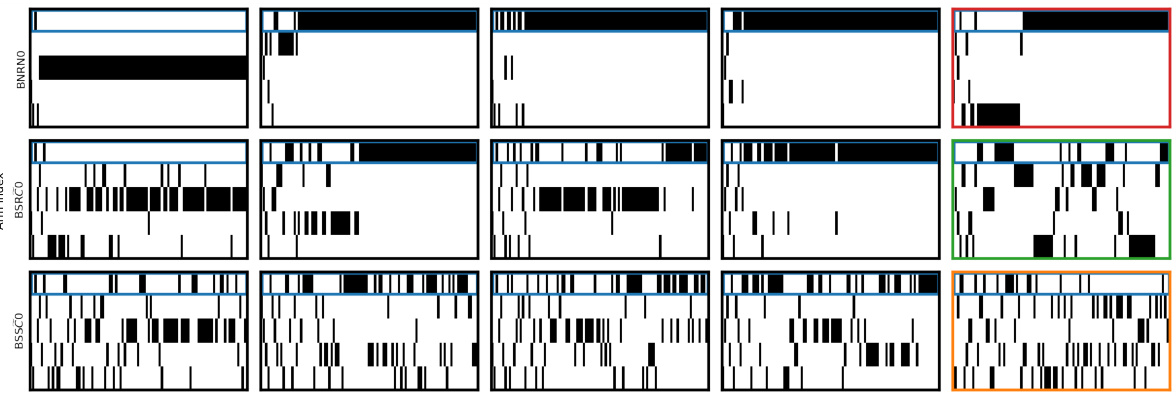

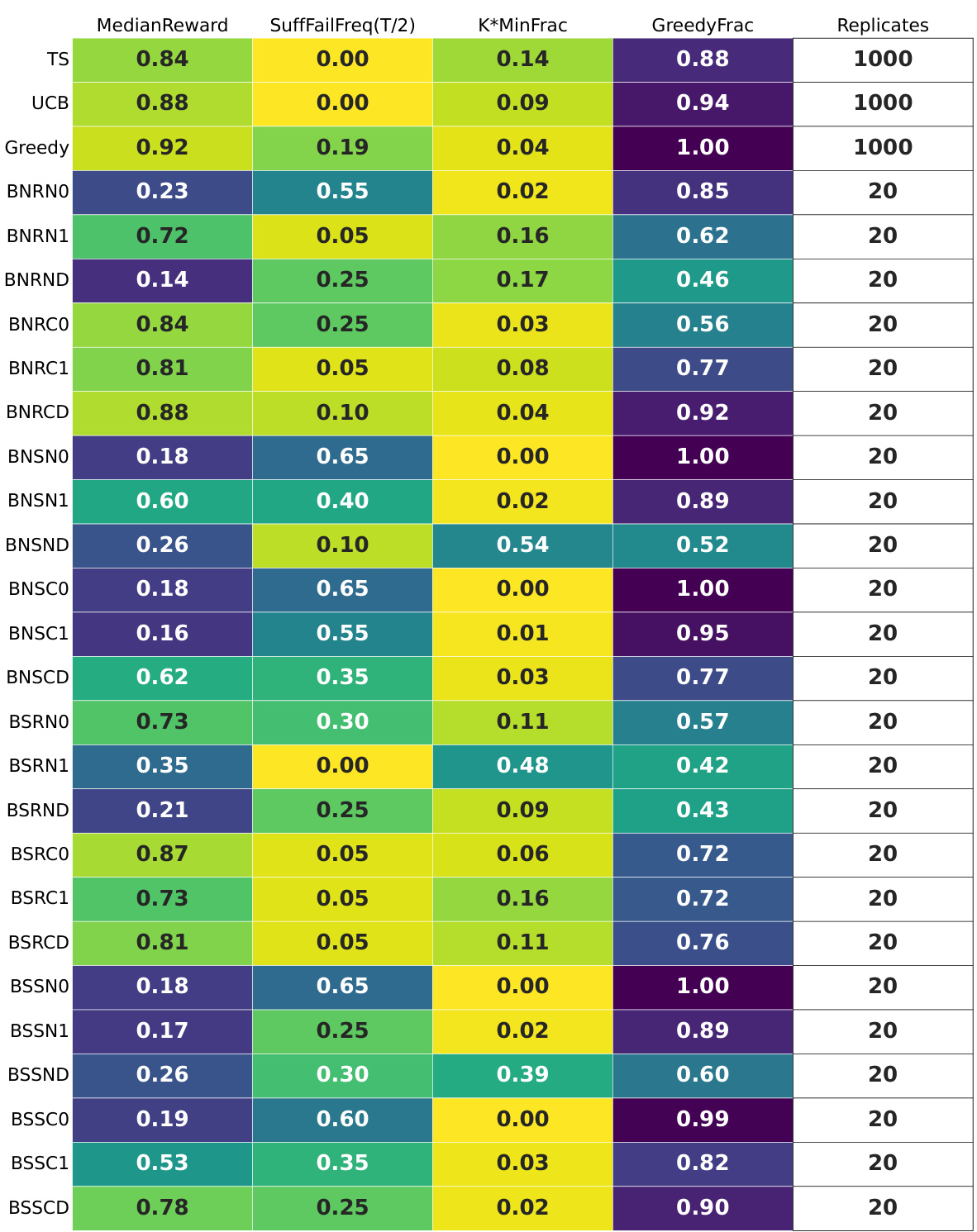

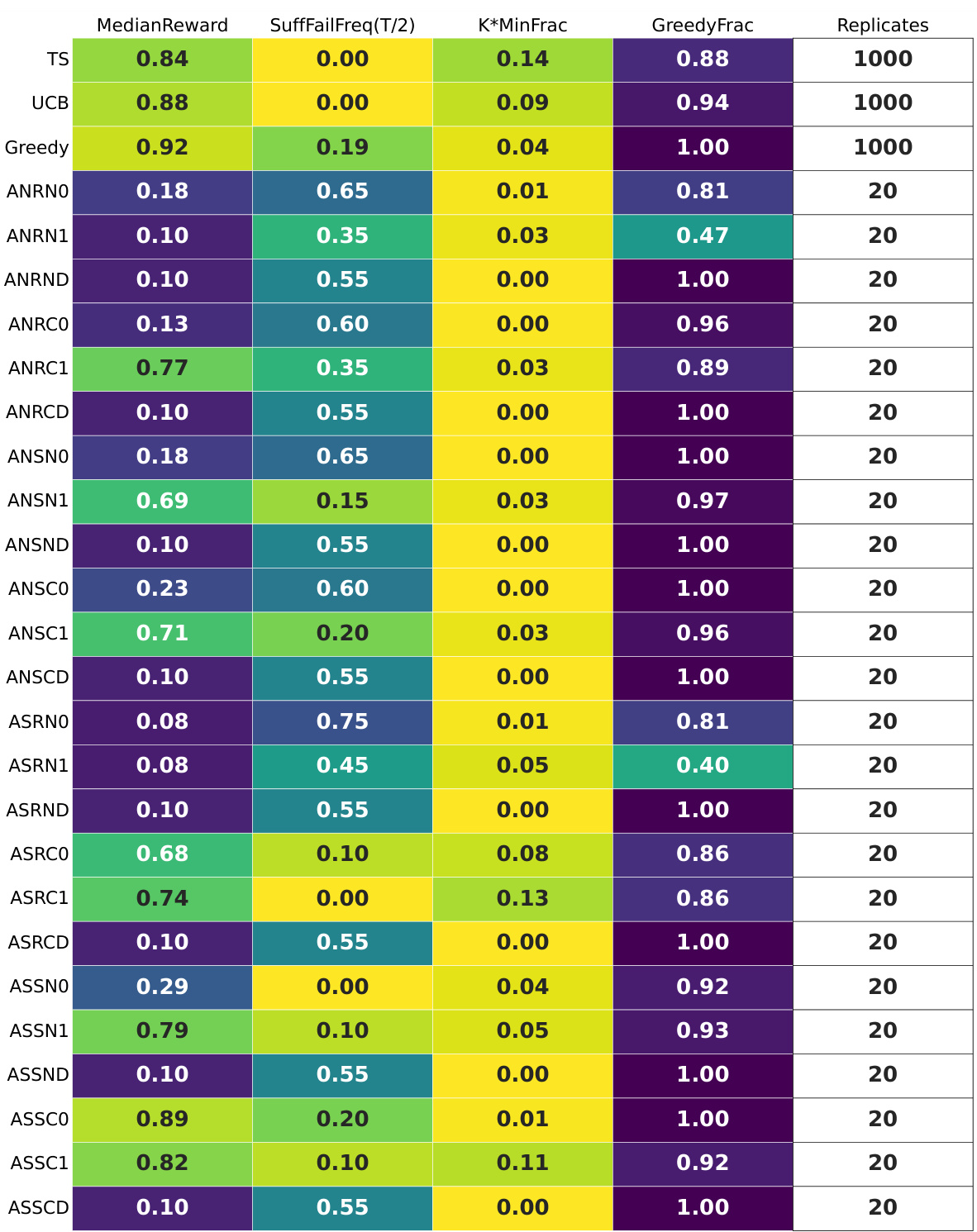

🔼 This table summarizes the results of the GPT-4 experiments on different configurations of the multi-armed bandit problem. It shows key statistics for each configuration, including the median reward achieved, the frequency of suffix failures (where the best arm is never selected after a certain point), the minimum fraction of times each arm was chosen (indicating uniform-like behavior), and the fraction of times the greedy algorithm was mimicked. The table also shows the number of replicates used for each configuration. The ‘fails’ row shows whether all replicates completed successfully for each configuration.

read the caption

Figure 11: GPT-4 for T = 100: the per-configuration summary tables. The 'fails' row indicates that all replicates completed successfully.

🔼 This table summarizes the results of experiments using GPT-4 with different prompt designs and temperature settings on four different multi-armed bandit (MAB) problem instances. The table includes statistics such as median reward, suffix failure frequency, the minimum fraction of times each arm was pulled, and the fraction of times the greedy algorithm’s choice was made. The ‘fails’ row indicates whether any replicates failed to converge. The table provides a compact representation of the performance variations across different experimental settings.

read the caption

Figure 11: GPT-4 for T = 100: the per-configuration summary tables. The 'fails' row indicates that all replicates completed successfully.

🔼 This table presents a summary of the experimental results for GPT-4 with a time horizon of 100 time steps. It shows several key statistics for various LLM configurations, including median reward, suffix failure frequency, minimum fraction (an indicator of uniform-like failures), and greedy fraction. The configurations are systematically varied across different prompt designs, allowing for comparison of how different prompt choices impact performance. The ‘fails’ row indicates whether any of the replicates failed to complete successfully. This table helps in understanding which configurations exhibited successful exploration behavior (i.e., those with high reward and low failure rates).

read the caption

Figure 11: GPT-4 for T = 100: the per-configuration summary tables. The 'fails' row indicates that all replicates completed successfully.

🔼 This table summarizes the results of experiments using GPT-4 with different prompt designs in a multi-armed bandit (MAB) task with time horizon T=100. Each row represents a different prompt configuration, and includes metrics such as median reward, suffix failure frequency (SuffFailFreq(T/2)), the minimum fraction of times the least played arm was selected (K*MinFrac), the fraction of rounds the greedy algorithm was mimicked (GreedyFrac), and the number of replicates. The ‘fails’ row indicates if all replicates succeeded in finding the optimal arm. The table provides a quantitative comparison of the performance of different prompt designs in promoting successful exploration in the MAB task.

read the caption

Figure 11: GPT-4 for T = 100: the per-configuration summary tables. The 'fails' row indicates that all replicates completed successfully.

🔼 This table summarizes the results of experiments using GPT-4 with different prompt configurations on a multi-armed bandit (MAB) problem. For each configuration, it shows the median reward, suffix failure frequency (SuffFailFreq(T/2)), the minimum fraction of times each arm was chosen (K*MinFrac), and the fraction of times the greedy algorithm was used (GreedyFrac). It also indicates the number of replicates for each configuration. The ‘fails’ row shows whether any replicates failed to complete.

read the caption

Figure 11: GPT-4 for T = 100: the per-configuration summary tables. The 'fails' row indicates that all replicates completed successfully.

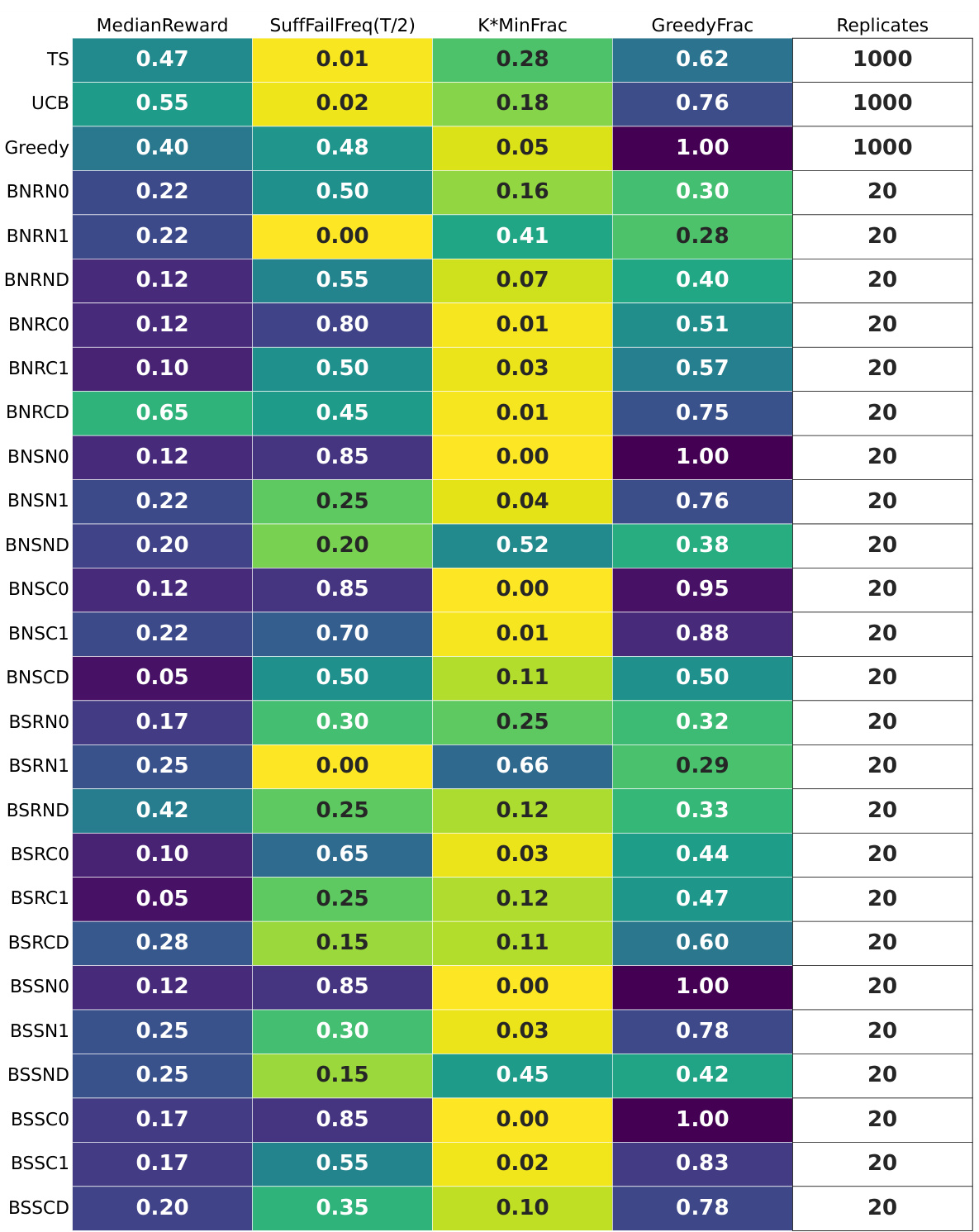

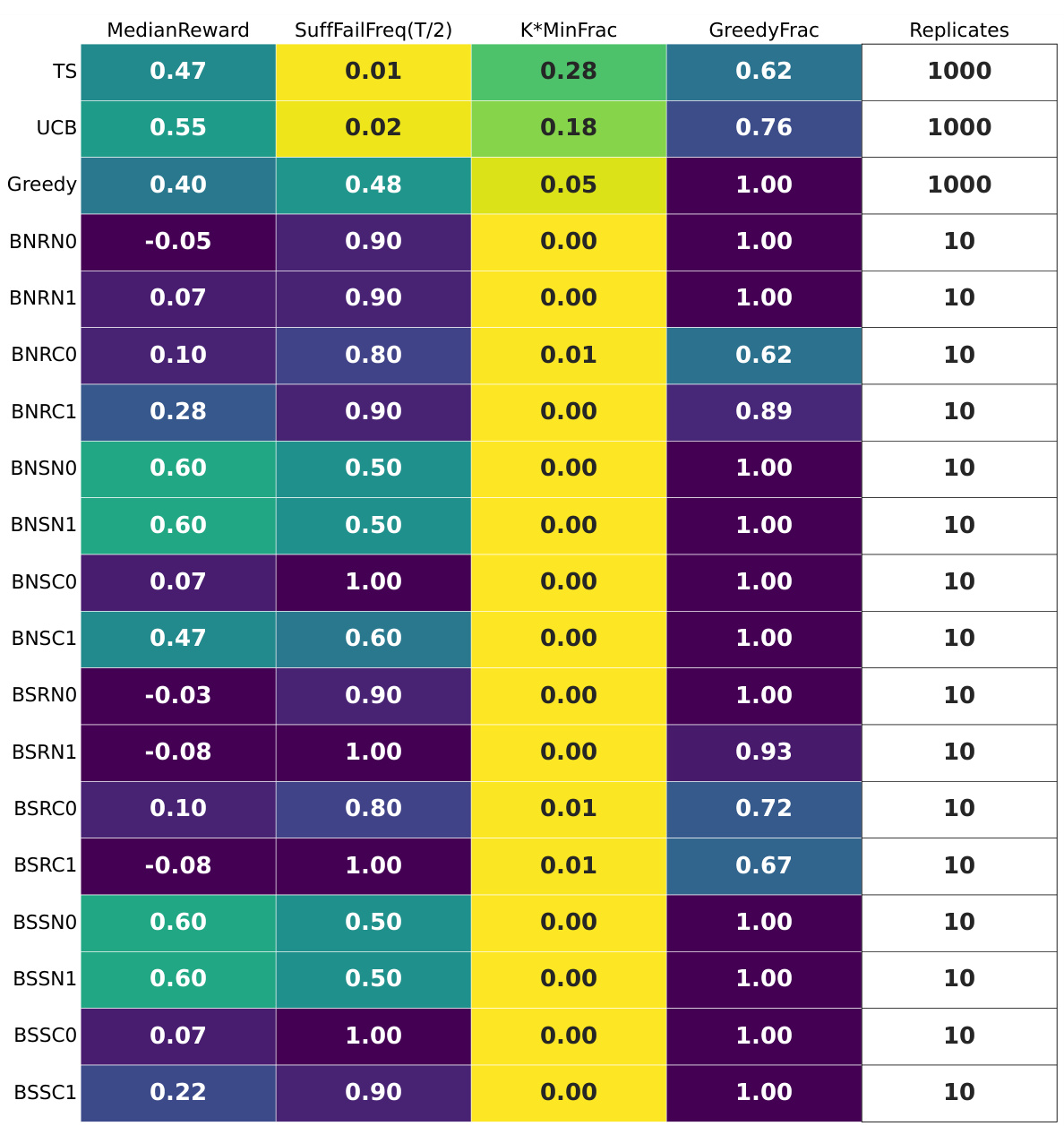

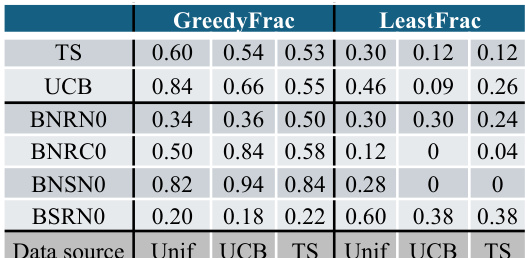

🔼 This table presents a summary of the experimental results for LLAMA2 on the hard multi-armed bandit (MAB) instance using the buttons scenario. It shows the median reward achieved by each of the 32 LLM configurations, along with the suffix failure frequency at T/2, the minimum fraction of times each arm is chosen (K*MinFrac), and the fraction of greedy rounds (GreedyFrac). The results highlight the relative performance of various prompt designs and their impact on exploration behavior in the context of LLMs. The table also includes the number of replicates used for each configuration.

read the caption

Figure 16: LLAMA2 for T = 100: the per-configuration summary tables. The buttons scenario, hard MAB instance.

🔼 This table summarizes the results of experiments using LLAMA2 on a hard multi-armed bandit problem with a time horizon of 100. It shows various performance metrics for different prompt designs, including the median reward, the frequency of suffix failures (where the best arm is never selected in the latter half of the rounds), the minimum fraction of times each arm was chosen, and the fraction of times a greedy approach (choosing the current best arm) was used. The goal is to assess the exploration capabilities of LLAMA2 under different prompt configurations.

read the caption

Figure 16: LLAMA2 for T = 100: the per-configuration summary tables. The buttons scenario, hard MAB instance.

🔼 This table summarizes the results of experiments using GPT-4 on a 5-armed bandit problem with a reward gap of 0.2. It shows the performance of various prompt configurations across several key metrics, including median reward, suffix failure frequency, uniform failure frequency, and the frequency of greedy choices. The table highlights that only one configuration (BSSCO) achieves satisfactory exploratory behavior, while others suffer from suffix failures (where the best arm is not selected after a certain point) or uniform-like failures (where all arms are selected nearly equally).

read the caption

Figure 4: GPT-4 for T = 100: a per-configuration summary table on the hard MAB instance with N = 10 replicates. Only three GPT-4 configurations do not exhibit suffix failures; two of these (BNRND and BSSCD) exhibit uniform-like failures. The final configuration (BSSCO) succeeds.

Full paper#