↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Training models on large pretrained datasets can be computationally expensive. Subsampling, a common technique to reduce computational costs, implicitly regularizes models in ways not fully understood. The use of pretrained features is prevalent in machine learning, especially in computer vision and natural language processing, but using them effectively while managing computational burden is crucial.

This paper provides a theoretical framework that bridges the gap between observation weighting and explicit ridge regularization. The researchers show that different weighting matrices and ridge penalty levels lead to asymptotically equivalent estimators. This equivalence holds for various feature structures and subsampling strategies, and is validated using both synthetic and real-world data with pretrained ResNet models. They develop an efficient cross-validation method based on these theoretical findings and demonstrate its effectiveness in practical applications, confirming existing conjectures and resolving open questions in the field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large datasets and pretrained models. It offers efficient methods for tuning hyperparameters, improving model performance, and opening up new avenues for research in implicit regularization and ensemble methods. Its general theoretical framework is applicable to various models and feature structures, greatly extending the existing research.

Visual Insights#

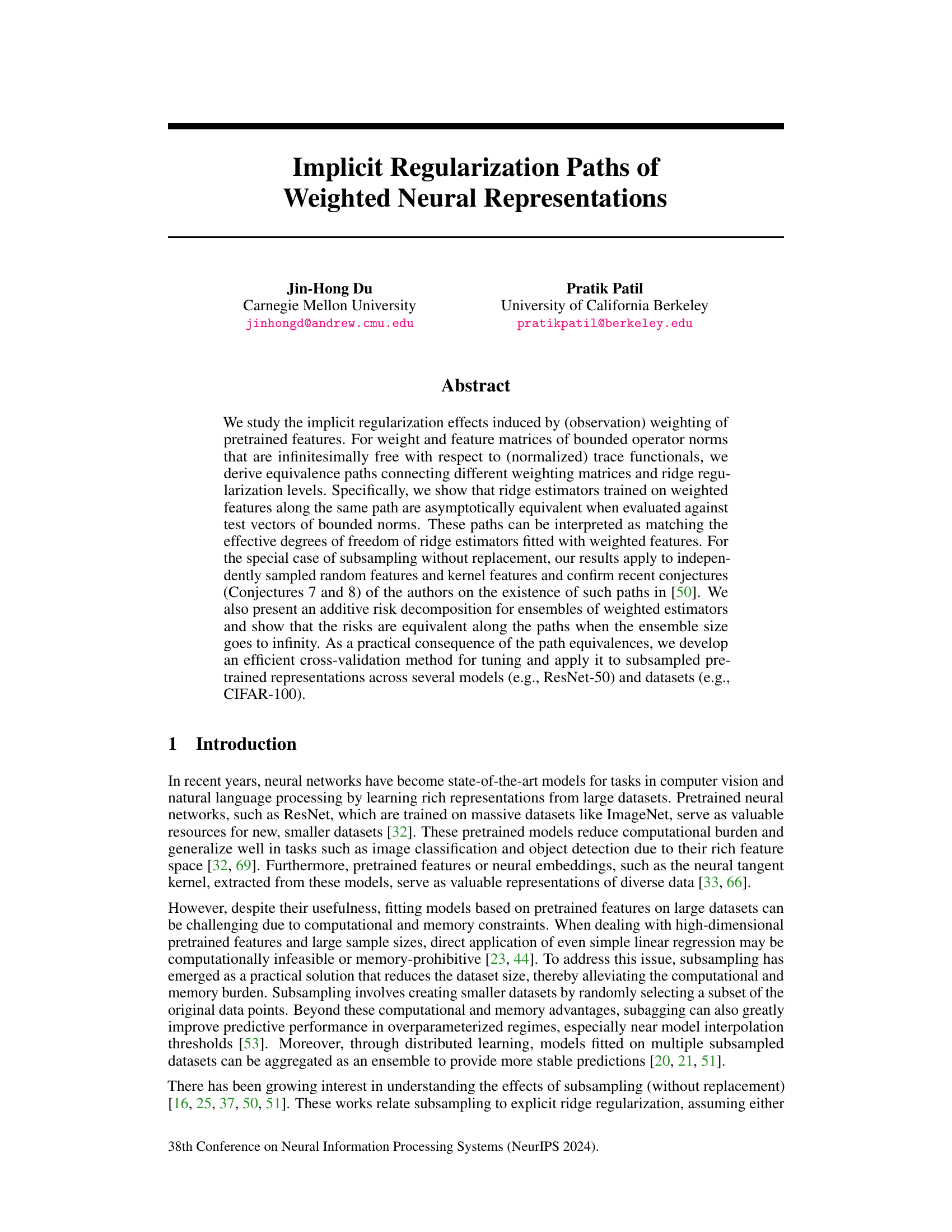

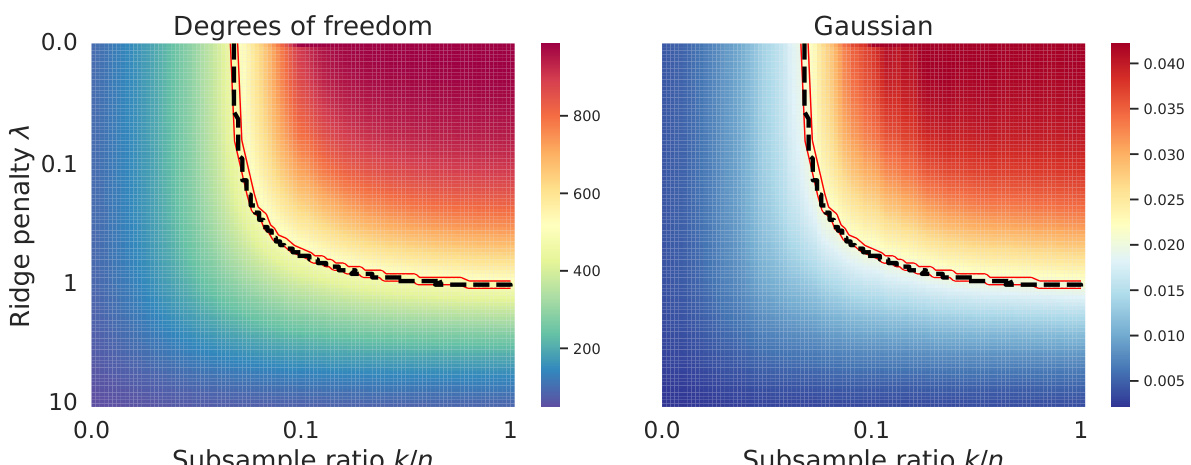

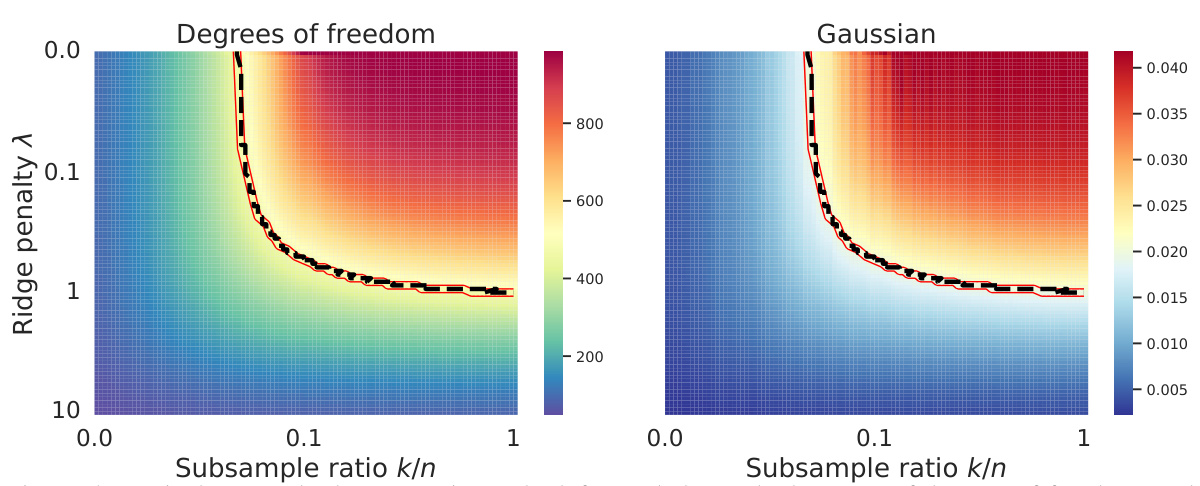

This figure shows the equivalence between subsampling and ridge regularization by comparing the degrees of freedom and random projections of weighted and unweighted models. The left panel is a heatmap of degrees of freedom, showing how it changes with subsample ratio and ridge penalty. The right panel displays the random projections of the weighted estimators. Red lines represent theoretical equivalence paths, and black dashed lines show empirical paths obtained by matching the empirical degrees of freedom. The experiment involved 10,000 data points, 1,000 features, and 100 different random weight matrices. The figure demonstrates that the theoretical and empirical paths largely agree.

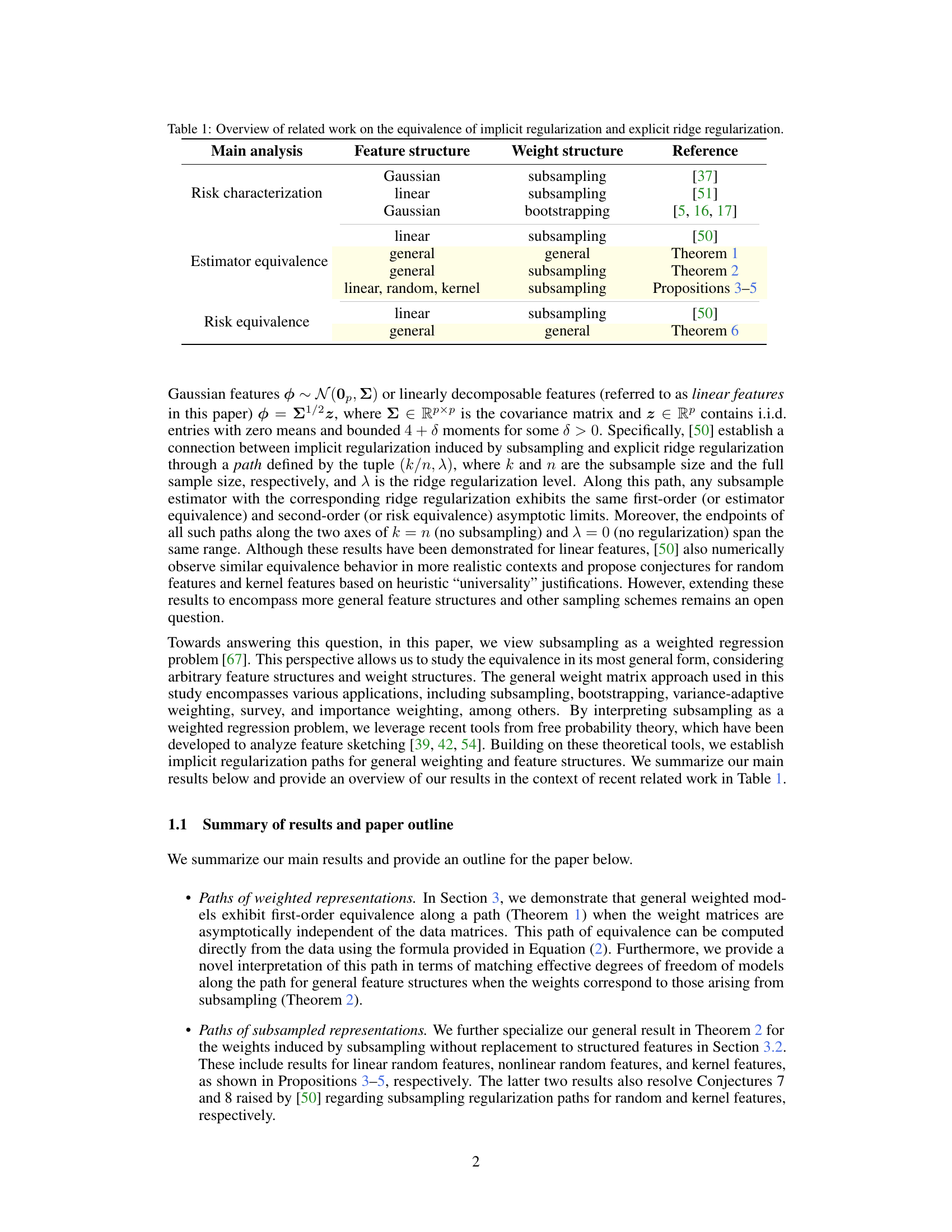

This table summarizes relevant prior works on the equivalence between implicit regularization (induced by subsampling, bootstrapping, etc.) and explicit ridge regularization. It compares different analyses (risk characterization, estimator equivalence, risk equivalence), feature structures (Gaussian, linear, general, random, kernel), weight structures (subsampling, bootstrapping, general), and provides references for each combination. The current paper extends this prior work by establishing implicit regularization paths for general weighting and feature structures.

In-depth insights#

Implicit Regularization#

Implicit regularization is a phenomenon where a machine learning model, despite lacking explicit regularization terms, exhibits properties similar to those induced by explicit regularization. This paper delves into the implicit regularization effects arising from observation weighting of pretrained neural network features. It explores how different weighting schemes, such as subsampling, connect to various levels of explicit ridge regularization through equivalence paths, matching effective degrees of freedom across weighted and unweighted estimators. This connection is established under specific conditions of asymptotic freeness between the weight and feature matrices, allowing for the derivation of these equivalence paths. The practical consequence is the development of a more efficient cross-validation method for tuning hyperparameters. The study extends beyond simpler feature structures, investigating linear, random, and kernel features, and establishing equivalent paths. The ensemble method provides a risk decomposition demonstrating risk equivalence along the path, confirming and extending previous conjectures in the field.

Weighted Regression#

Weighted regression is a statistical method that assigns different weights to observations in a dataset, allowing for more nuanced analysis and model fitting. Observations with higher weights have a greater influence on the model’s parameters than those with lower weights. This technique is particularly useful when dealing with data exhibiting heteroscedasticity (non-constant variance) or when some data points are considered more reliable than others. Weighting schemes can be designed to address specific issues in a dataset, such as outliers or imbalances in class representation. The choice of weight function is crucial, impacting the model’s robustness and accuracy. Careful consideration of the weighting strategy is needed to ensure that the model does not unduly bias toward certain observations and that appropriate statistical assumptions are met. Applications of weighted regression span various fields, including economics, finance, and environmental science. Further research could focus on the development of new weighting functions tailored to specific datasets and improved methods for weight selection and optimization.

Ensemble Risk#

Analyzing ensemble risk in the context of weighted neural representations reveals crucial insights into model generalization. The core idea is to leverage the power of multiple models trained on differently weighted versions of the data to improve prediction accuracy and robustness. This approach mitigates the limitations of individual weighted models, particularly in addressing the issue of overfitting. By combining predictions from an ensemble of weighted estimators, the overall risk can be significantly reduced, achieving a more stable and reliable outcome. The theoretical results demonstrate that risk equivalence exists along specific paths connecting weighted and unweighted models, highlighting the implicit relationship between weight matrices, ridge regularization, and degrees of freedom. This equivalence suggests that efficient cross-validation methods can be developed to tune the hyperparameters of both the ensemble and the individual weighted models, thereby optimizing predictive performance in practical settings. The benefits of ensembling are particularly pronounced as the number of ensemble members grows, leading to asymptotic risk equivalence and potentially more stable performance even in high-dimensional datasets.

Subsampling Paths#

The concept of “Subsampling Paths” in the context of implicit regularization within neural networks suggests a novel way to understand the relationship between subsampling techniques and explicit regularization methods like ridge regression. Instead of viewing subsampling as a discrete operation, it is explored as a continuous path connecting different levels of data reduction and explicit regularization. This path reveals asymptotic equivalence between models trained on subsampled data and those trained on full data with specific ridge penalties. Crucially, this equivalence extends beyond basic linear models, encompassing various feature structures (linear, random, kernel). The theoretical underpinnings likely involve techniques from free probability theory, which might allow for a formal proof showing equivalence in terms of degrees of freedom and risk. Practical implications include efficient cross-validation, as exploring the entire subsampling path is more efficient than exhaustive grid search of subsample size and regularization parameter. The path’s existence implies a more nuanced relationship between subsampling’s benefits (reduced computational cost, improved generalization) and implicit regularization’s effects, opening promising avenues for future research in efficient model training and understanding generalization.

Cross-Validation Tuning#

Cross-validation is a crucial model selection technique, particularly valuable when dealing with high-dimensional data and complex models prone to overfitting. Its application in the context of weighted neural representations involves carefully tuning hyperparameters, such as the regularization parameter (lambda) and the subsample size (k), to balance model complexity and generalization performance. The implicit regularization paths framework offers a novel way to perform this tuning, providing a principled method to explore the space of possible models. Instead of independently tuning lambda and k, this method efficiently explores the path where weighted models are approximately equivalent to the full unweighted model. The effectiveness of this approach lies in its computational efficiency, as it reduces the need to perform extensive cross-validation across the entire lambda-k grid. However, the optimal ensemble size (M) still requires tuning, which can be done using nested cross-validation or other model selection techniques to mitigate overfitting in the ensemble. A significant advantage is the path’s data-dependence, enabling adaptive tuning tailored to specific datasets and neural architectures. This approach offers a powerful and efficient strategy for selecting optimal models from the space of weighted neural representations, thereby enhancing both the accuracy and efficiency of model training.

More visual insights#

More on figures

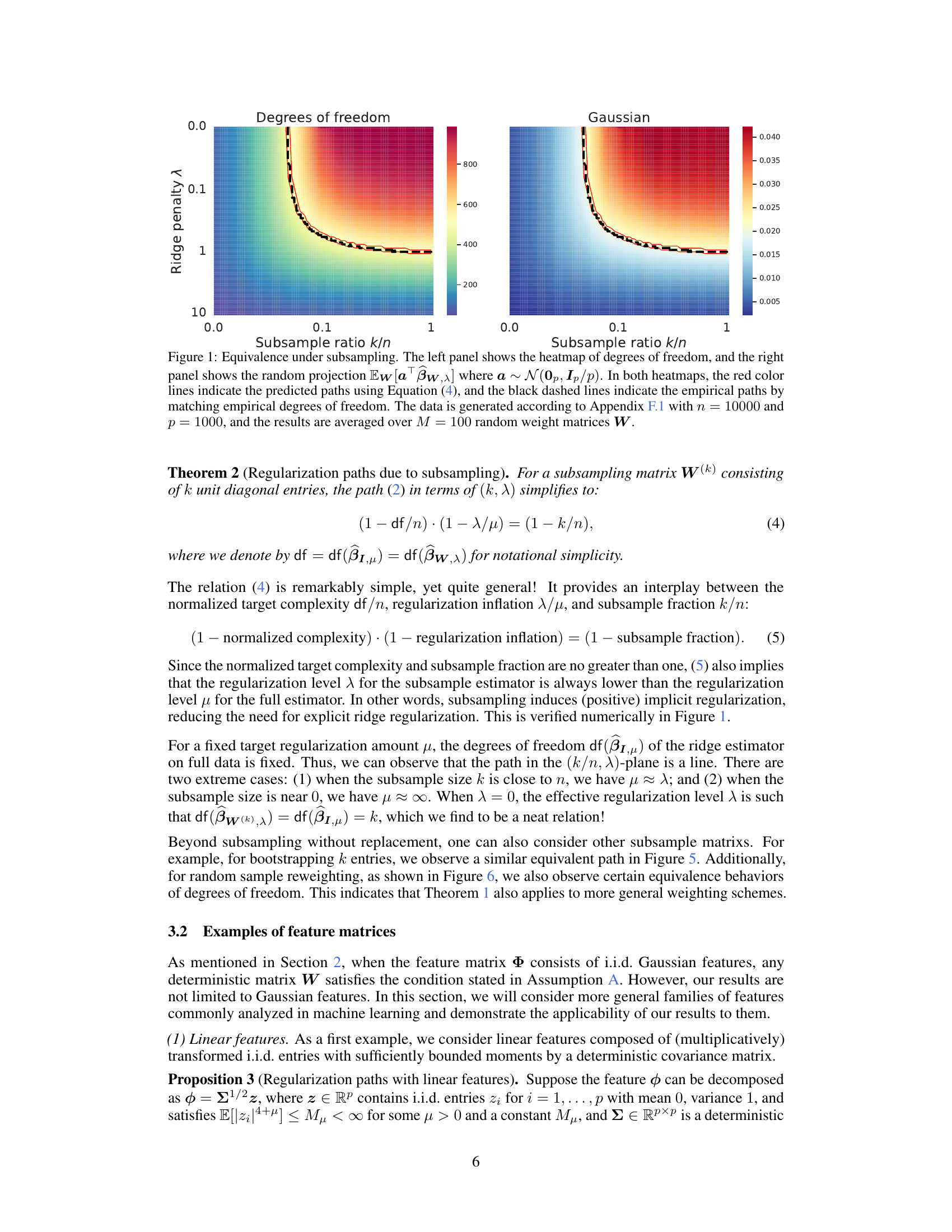

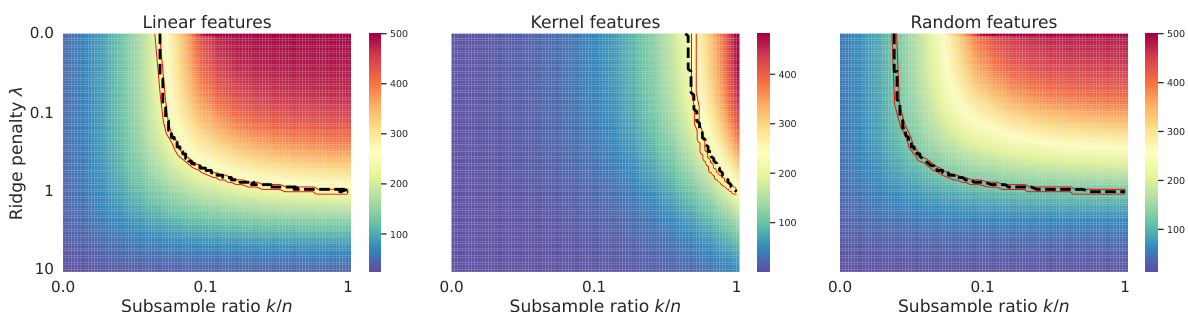

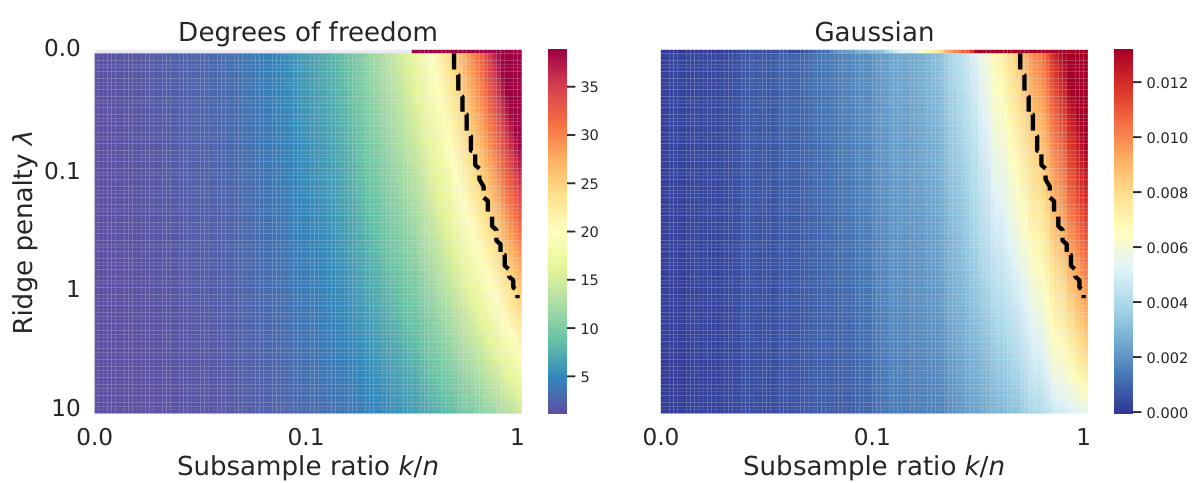

This figure shows the equivalence paths for three different types of feature structures (linear, kernel, and random features) under subsampling. The heatmaps display the degrees of freedom as a function of the subsample ratio (k/n) and ridge penalty (λ). Red lines represent the theoretically predicted paths calculated using Equation (4), while black dashed lines show the empirical paths determined by matching the empirical degrees of freedom. The results support the paper’s finding that implicit regularization from subsampling is equivalent to explicit ridge regularization along specific paths.

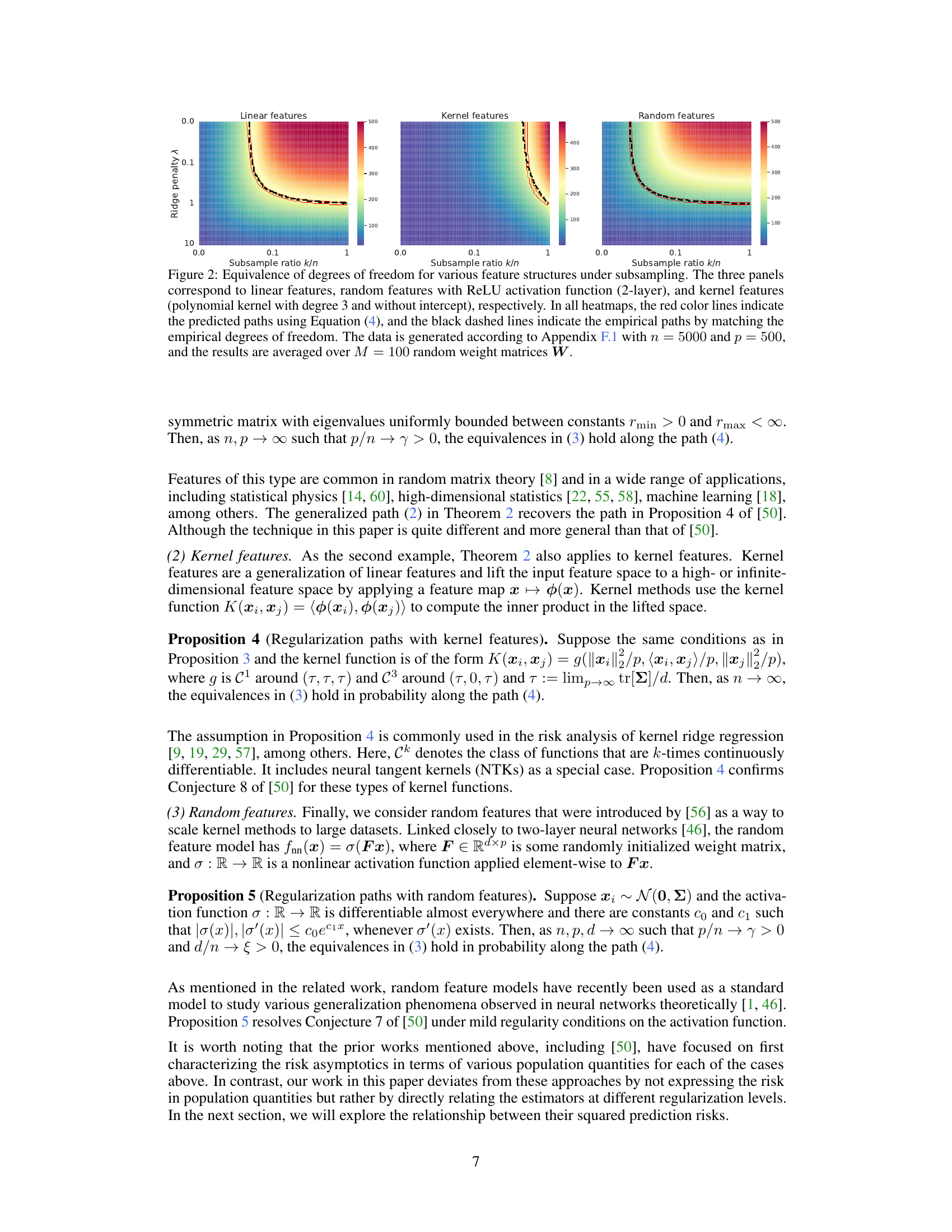

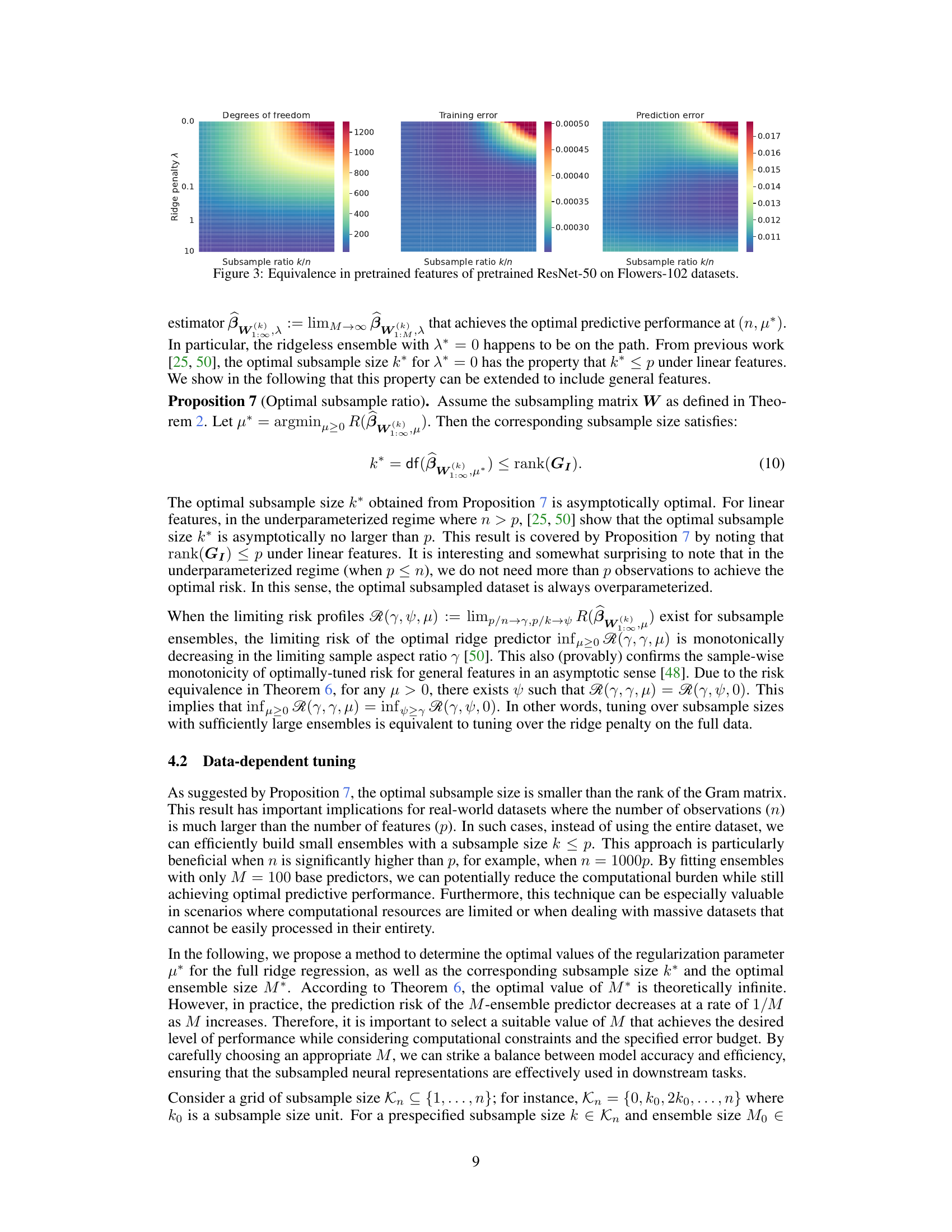

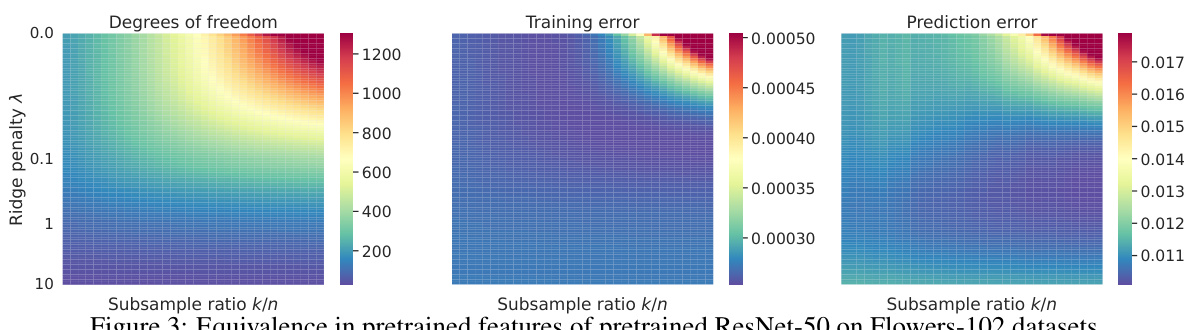

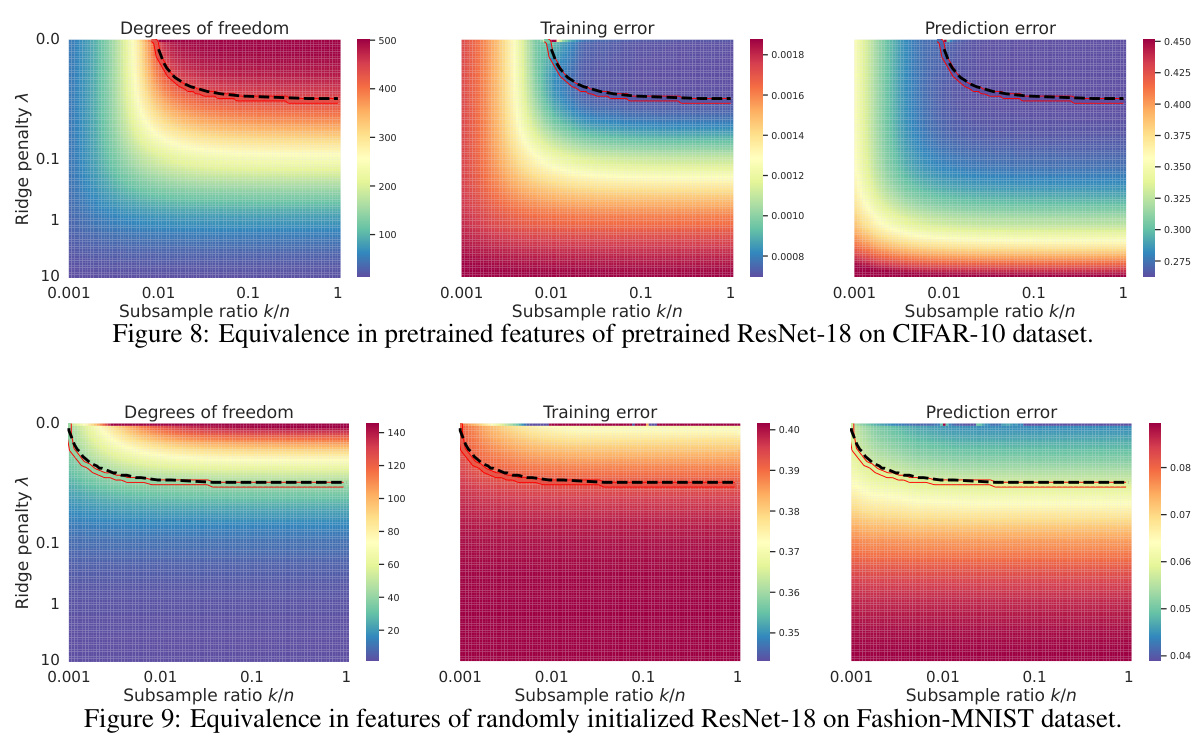

The figure shows the equivalence of degrees of freedom, training error, and prediction error of pretrained ResNet-50 models on Flowers-102 datasets under various subsampling ratios (k/n) and ridge penalty levels (λ). The heatmaps visually represent the relationships, demonstrating how these metrics change along implicit regularization paths, connecting weighted pretrained features to explicit ridge regularization.

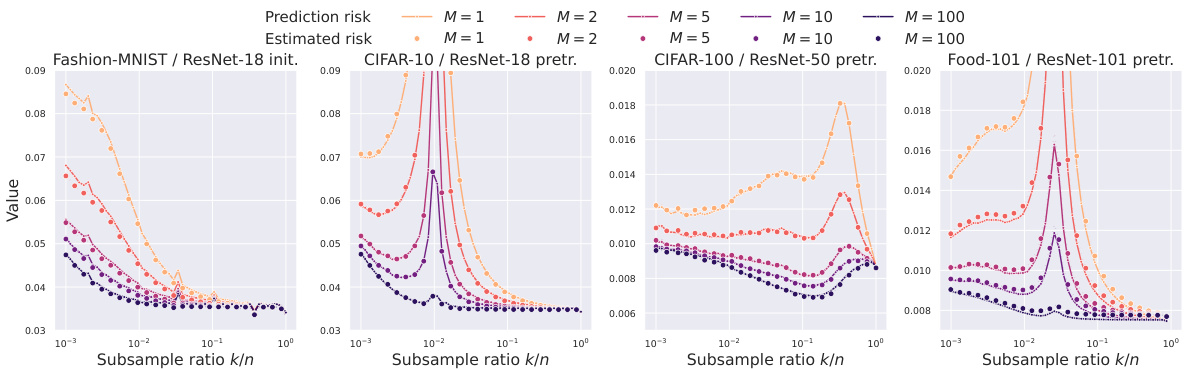

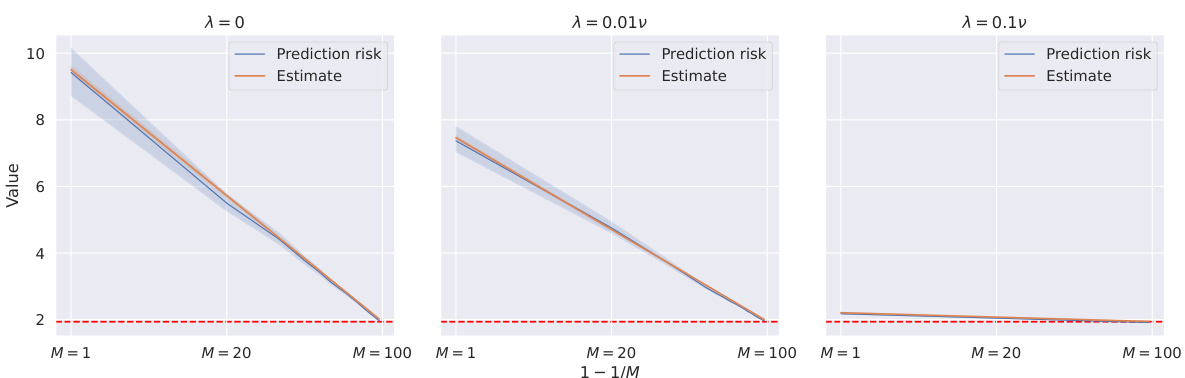

This figure shows the prediction risks and their estimates obtained by using corrected and extrapolated generalized cross-validation methods for different ensemble sizes (M) and subsample ratios (k/n) across four different datasets. The risk estimates closely match the actual prediction risks even for small subsample ratios (k/n = 0.01) and sufficiently large ensemble sizes (M = 100).

This figure shows two heatmaps. The left heatmap shows the degrees of freedom for different subsample ratios (k/n) and ridge penalties (λ). The right heatmap shows the random projection Ew[a¯ßw,x], which is a measure of the model’s performance. Red lines represent the theoretical equivalence paths derived from Equation (4) in the paper, showing the relationship between subsample size and ridge penalty. The black dashed lines depict empirical paths obtained by matching the empirical degrees of freedom, demonstrating good agreement with the theoretical predictions.

This figure shows the equivalence between subsampling and ridge regularization. The left panel displays a heatmap illustrating the degrees of freedom for different subsampling ratios (k/n) and ridge penalties (λ). The right panel shows random projections, providing further evidence of equivalence. Red lines represent theoretically predicted paths, while black dashed lines show empirically determined paths. The close match between theoretical and empirical paths supports the paper’s claim of equivalence.

The figure shows the prediction risks and their estimates for different ensemble sizes (M) under three different regularization levels (λ). The results are consistent with the risk equivalence theory, where the ensemble risk converges to the full-ridge risk as M increases.

This figure shows the equivalence between subsampling and ridge regularization. The left panel displays a heatmap illustrating the degrees of freedom for different subsampling ratios (k/n) and ridge penalty values (λ). The right panel shows a heatmap of random projections, visualizing the estimator equivalence. Red lines represent the theoretical equivalence path predicted by equation (4), while black dashed lines show the empirical paths obtained by matching the degrees of freedom. The data used was generated according to Appendix F.1, with a large sample size (n=10000) and feature dimension (p=1000), averaged over 100 random weight matrices. The figure demonstrates the close agreement between theoretical predictions and empirical observations, supporting the main claim of the paper that subsampling and ridge regularization are asymptotically equivalent along a specific path.

Full paper#