TL;DR#

Exploration in reinforcement learning (RL) is crucial but challenging, particularly in complex environments lacking explicit reward signals. Existing methods often struggle to balance exploration and efficient learning, sometimes relying on heuristic exploration bonuses. These bonuses can be unstable and require careful design. Furthermore, maximizing mutual information between skills and states, a common approach, may not always promote sufficient exploration, yielding ambiguous results.

This paper introduces LEADS, an algorithm that learns diverse skills for efficient exploration using successor state representations. LEADS addresses limitations of existing methods by maximizing a novel objective function that promotes both skill diversity and state-space coverage. It leverages a new uncertainty measure and incorporates exploration bonuses within the framework of mutual information maximization, offering a more robust and effective exploration strategy. Experimental results demonstrate LEADS’s superior performance across multiple maze navigation and robotic control tasks compared to state-of-the-art techniques, highlighting its efficiency and effectiveness in reward-free scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel method for exploration in reinforcement learning that significantly outperforms existing approaches. It addresses a key challenge in RL by promoting both skill diversity and efficient state-space coverage, opening new avenues for research in exploration and skill discovery. The method’s ability to achieve this without relying on reward bonuses is particularly noteworthy and offers advantages in complex, reward-free environments. The use of successor state representations offers a new perspective on mutual information maximization, and the exploration bonuses enhance the method’s robustness.

Visual Insights#

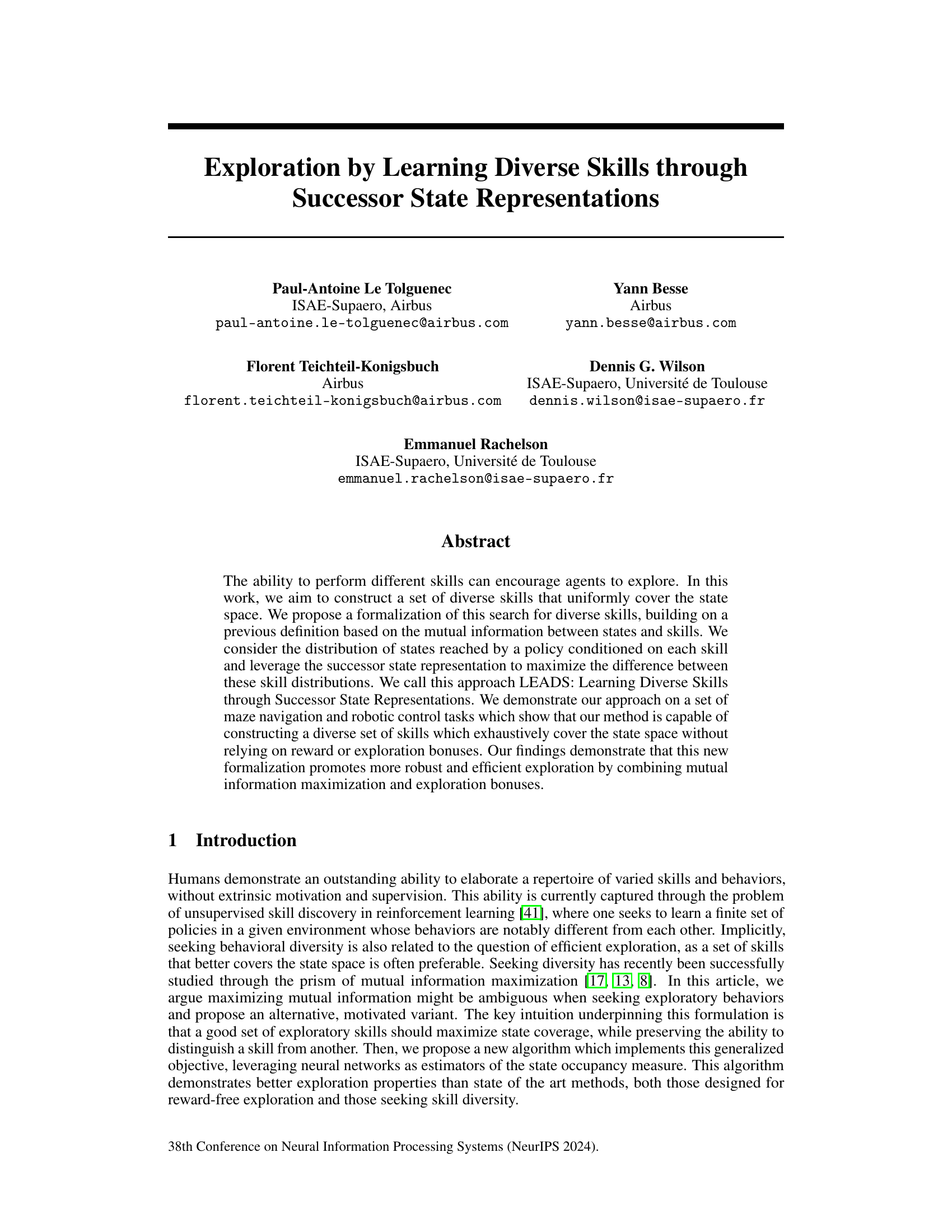

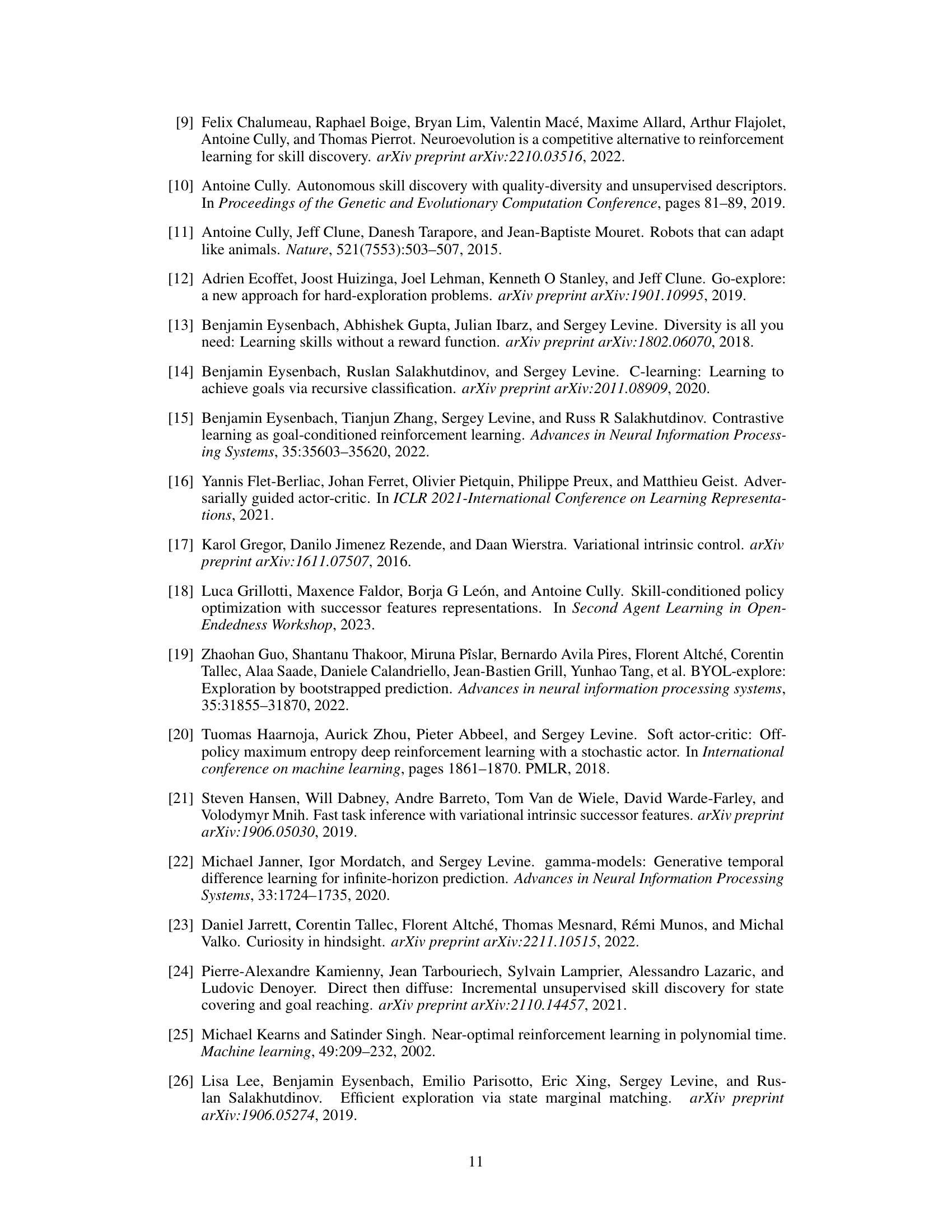

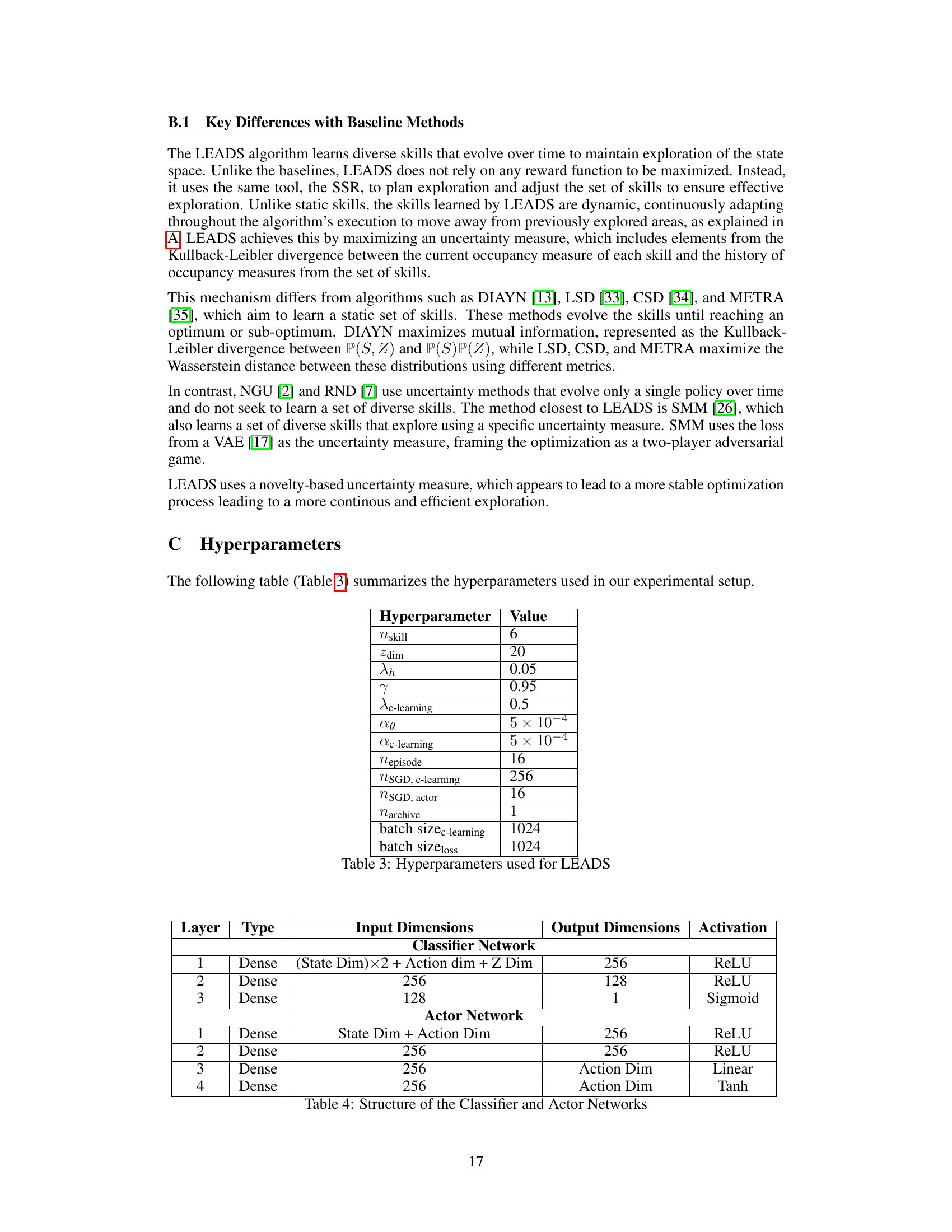

🔼 This figure illustrates two different sets of skills (Z1 and Z2) in a grid-world environment. Each set contains four skills, each represented by a unique symbol. The left panel (Z1) shows each skill visiting only one state. The right panel (Z2) shows each skill visiting two states. Gray squares represent unreachable states. The figure is used to demonstrate how the mutual information between states and skills might not capture the concept of exploration sufficiently well, as both Z1 and Z2 have the same mutual information, while Z2 is more exploratory.

read the caption

Figure 1: State distributions of two sets Z1 (left) and Z2 (right) of four skills each on a grid maze. Each skill's visited states are represented by a different symbol and distributed uniformly. The gray boxes are unreachable.

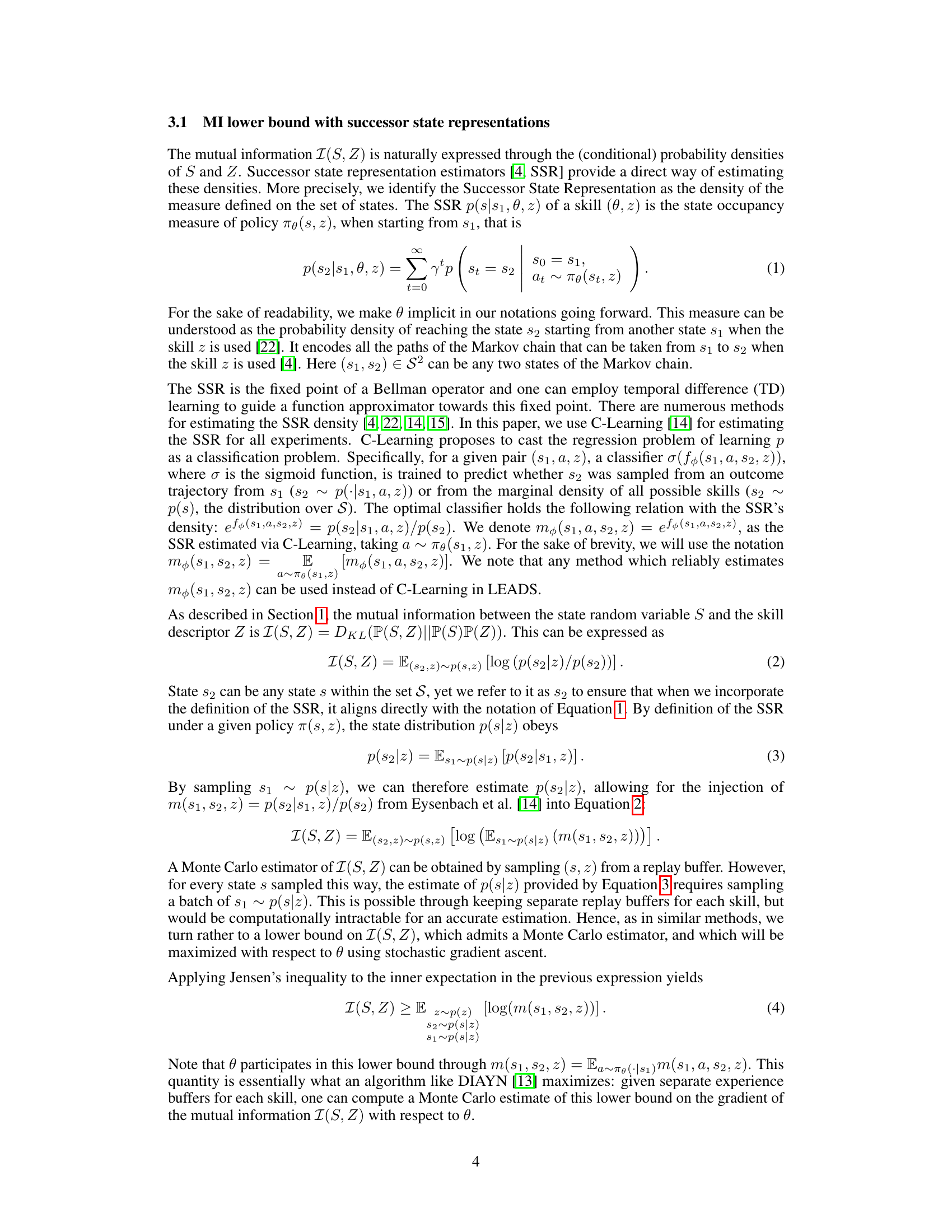

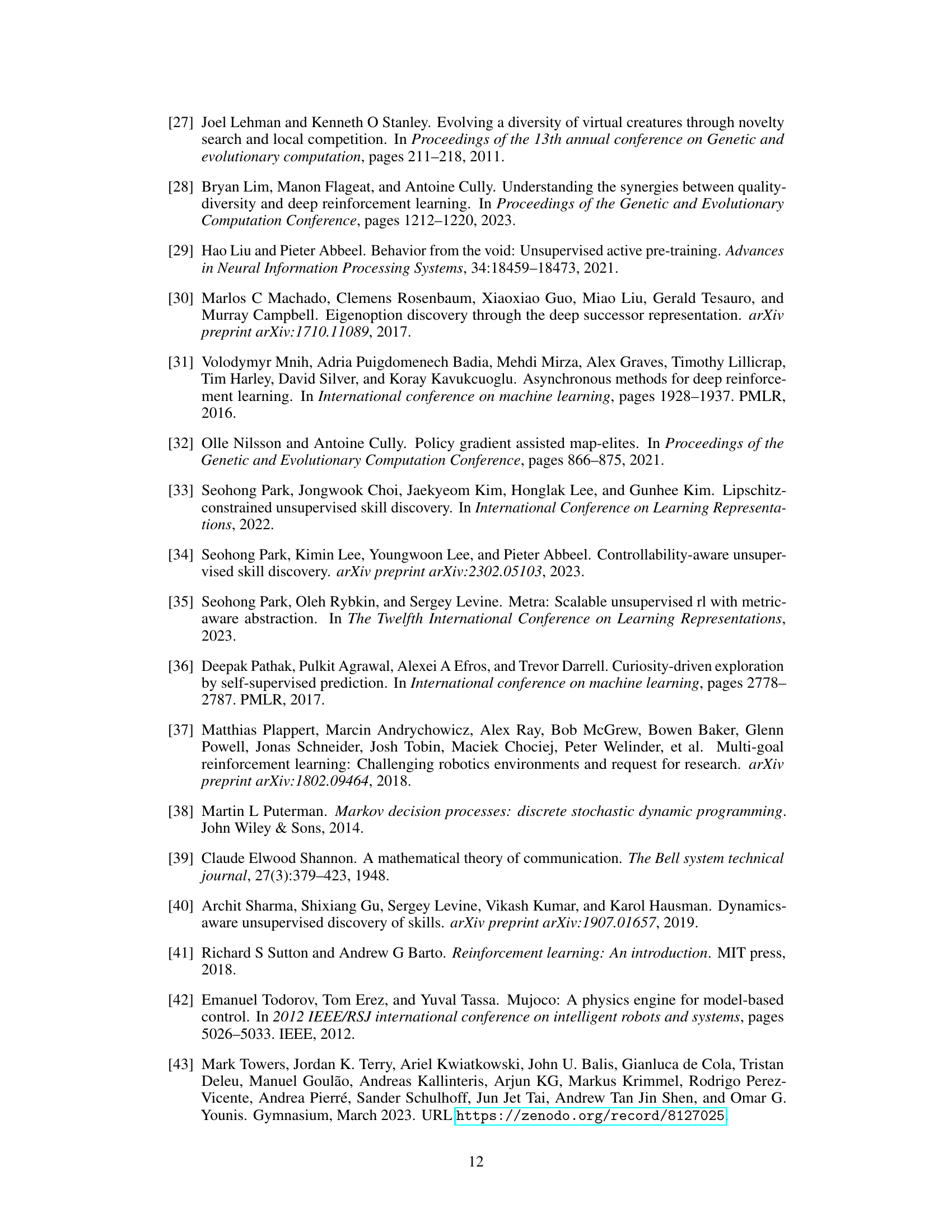

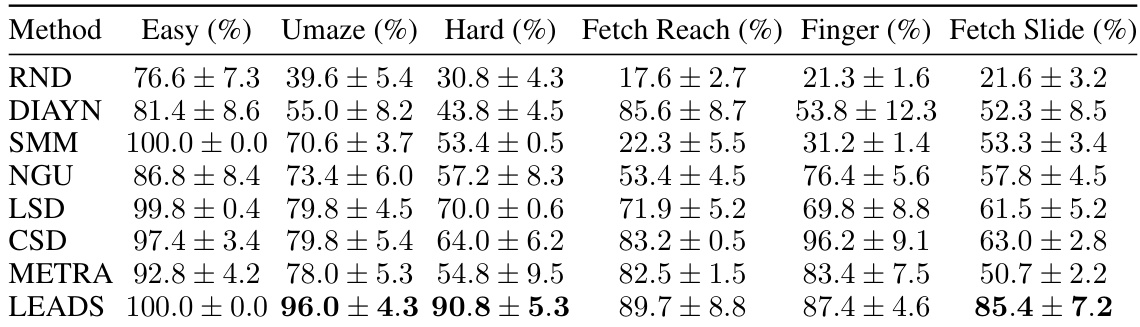

🔼 This table presents the final coverage percentages achieved by different exploration methods across various environments (mazes and robotic control tasks). It compares LEADS against several baseline methods, highlighting statistically significant differences (p<0.05) using t-tests. The results show the percentage of the state space covered by each algorithm. Appendix B provides more detailed results of the t-tests.

read the caption

Table 1: Final coverage percentages for each method on each environments. Bold indicates when a single method is statistically superior to all other methods (p < 0.05). Full T-test results are presented in Appendix B.

In-depth insights#

Diverse Skill Search#

Diverse skill search in reinforcement learning aims to discover a set of policies (skills) that exhibit diverse behaviors and comprehensively explore the environment’s state space. A core challenge is defining and measuring diversity; simple metrics might fail to capture the nuanced interactions between skills and their coverage. Mutual information (MI) has been used, quantifying the reduction in uncertainty about the state given knowledge of the skill, but its limitations are apparent. MI maximization may not fully encourage exploration, as it can prioritize highly informative but locally concentrated skills, neglecting less-informative but crucial areas. Alternative approaches incorporate concepts like successor state representations (SSR), leveraging the density of states reachable from a given starting state under a policy, enabling direct state space coverage assessment. The exploration problem is intrinsically linked to the problem of skill discovery: defining what constitutes a diverse and useful skillset is crucial. Methods such as LEADS (Learning Diverse Skills through Successor State Representations) focus on explicitly maximizing state coverage and skill distinctiveness, integrating measures that address both aspects, rather than relying solely on MI. Such advances move beyond simple MI maximization, creating more robust exploration and skill learning strategies.

Successor Features#

Successor features, in the context of reinforcement learning, offer a powerful mechanism for representing the long-term consequences of actions. They encode the expected future state occupancy, providing a more informative prediction than immediate state transitions. This allows agents to plan more effectively, reason about delayed rewards, and develop more robust policies. The core idea is to learn a function that maps current states and actions to a representation of the expected future states, considering the agent’s policy and the environment’s dynamics. Different methods exist for learning these features, often leveraging techniques like linear regression or neural networks. The resulting representations are particularly useful for hierarchical reinforcement learning, enabling the decomposition of complex tasks into simpler sub-tasks, and for improving generalization and sample efficiency. While computationally more expensive to learn than simpler features, the increased planning capabilities and improved generalization usually outweigh the cost, making them a valuable tool in complex reinforcement learning problems. A key advantage is their ability to disentangle the effects of immediate actions from the long-term impact on future states.

Exploration Bonus#

Exploration bonuses in reinforcement learning are reward mechanisms designed to encourage agents to explore under-explored states. They function by adding extra reward to states visited infrequently, thereby incentivizing the agent to venture beyond familiar areas. A crucial aspect is the design of the bonus function, which determines how the bonus is calculated and decays over time as states are explored. Poorly designed bonus functions can lead to inefficient exploration or even hinder the learning process. Count-based methods directly track state visit counts, while function approximation techniques are used in large state spaces to generalize bonus values. However, finding effective approximators is challenging, often requiring careful design and potentially leading to instability in learning. Alternative approaches focus on intrinsic motivation, framing exploration as an inherent reward signal, rather than an explicit bonus. These methods aim for more elegant and robust exploration strategies, potentially sidestepping the pitfalls of manual bonus function design. The choice between exploration bonuses and intrinsic motivation depends on the specifics of the task and the scalability requirements.

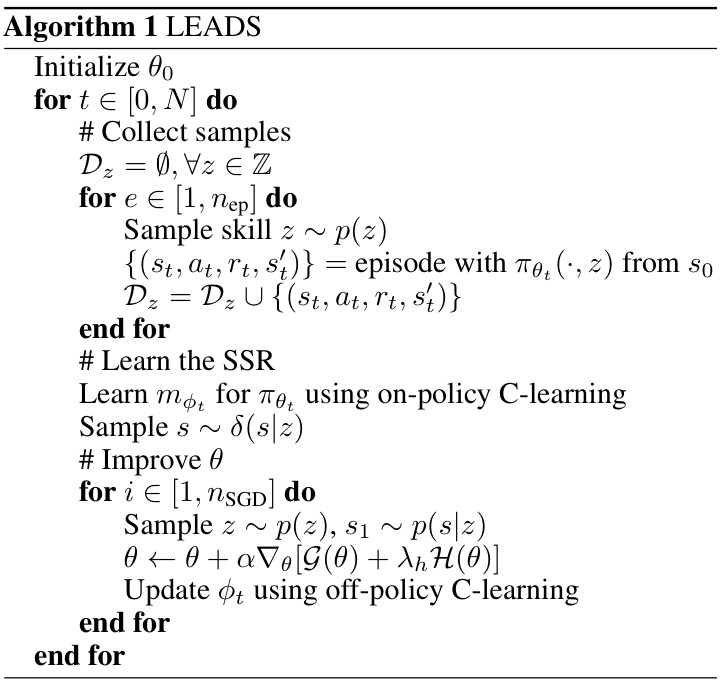

LEADS Algorithm#

The LEADS algorithm, designed for learning diverse skills through successor state representations, presents a novel approach to exploration in reinforcement learning. Instead of relying on reward signals or extrinsic motivation, it leverages the inherent diversity of skills to achieve comprehensive state space coverage. It formally defines a search for diverse skills based on mutual information but cleverly addresses limitations of traditional MI maximization by incorporating an exploration bonus. This bonus incentivizes the algorithm to explore under-visited states, thus avoiding premature convergence on a limited subset of the state space. The algorithm utilizes successor state representations (SSR) to efficiently estimate state occupancy measures, facilitating a more robust and data-efficient exploration process. It achieves this by dynamically updating skill policies, promoting more robust and efficient exploration through a novel combination of mutual information maximization and strategic exploration bonuses. The efficacy of LEADS is demonstrated through promising results in diverse environments, including maze navigation and robotic control tasks, showcasing its superior performance to other state-of-the-art exploration methods.

Future of LEADS#

The future of LEADS hinges on addressing its current limitations and exploring new avenues for improvement. Improving the successor state representation (SSR) estimation is crucial; the algorithm’s performance is heavily reliant on accurate SSRs, especially in complex environments. Investigating alternative SSR methods beyond C-learning could significantly enhance robustness and generalization. Incorporating more sophisticated exploration strategies is another key area for advancement. While LEADS uses an uncertainty measure to guide exploration, exploring alternative methods such as curiosity-driven or intrinsic motivation techniques could provide complementary benefits. Extending LEADS to handle continuous action spaces and more complex reward structures would broaden its applicability to a wider range of reinforcement learning problems. Lastly, developing a more efficient and scalable implementation is necessary to tackle larger, more complex environments and datasets. Addressing these areas will unlock LEADS’ full potential and solidify its place as a leading exploration algorithm.

More visual insights#

More on figures

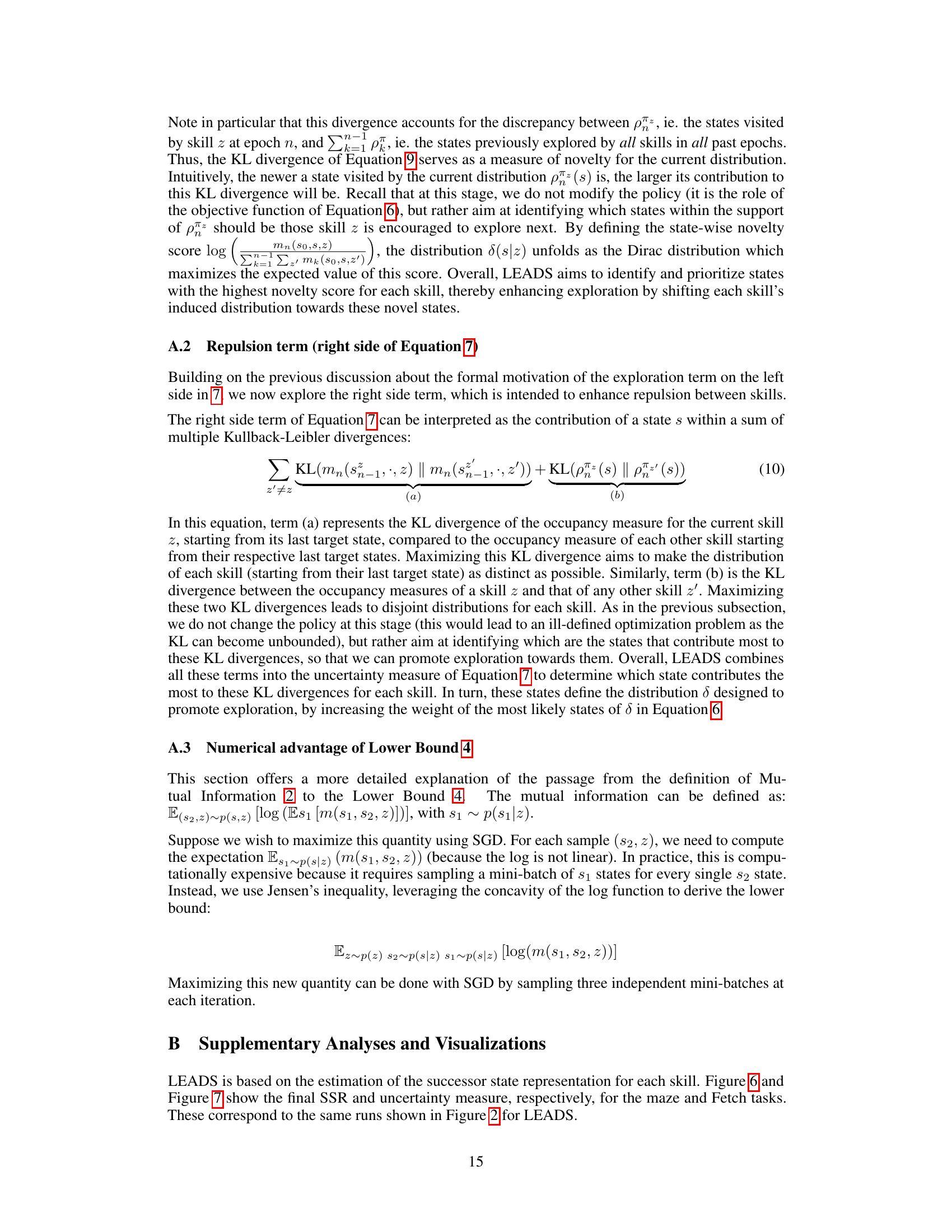

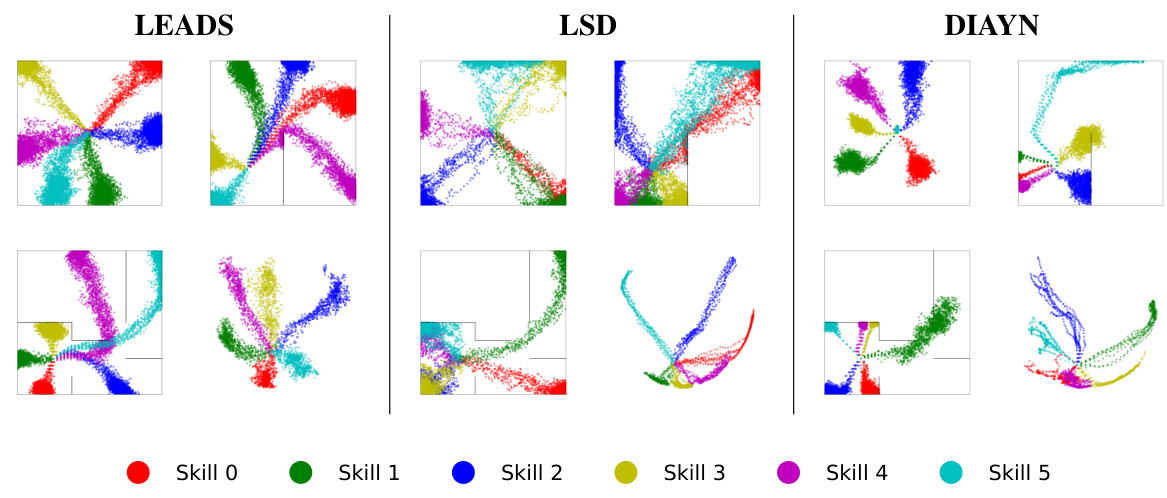

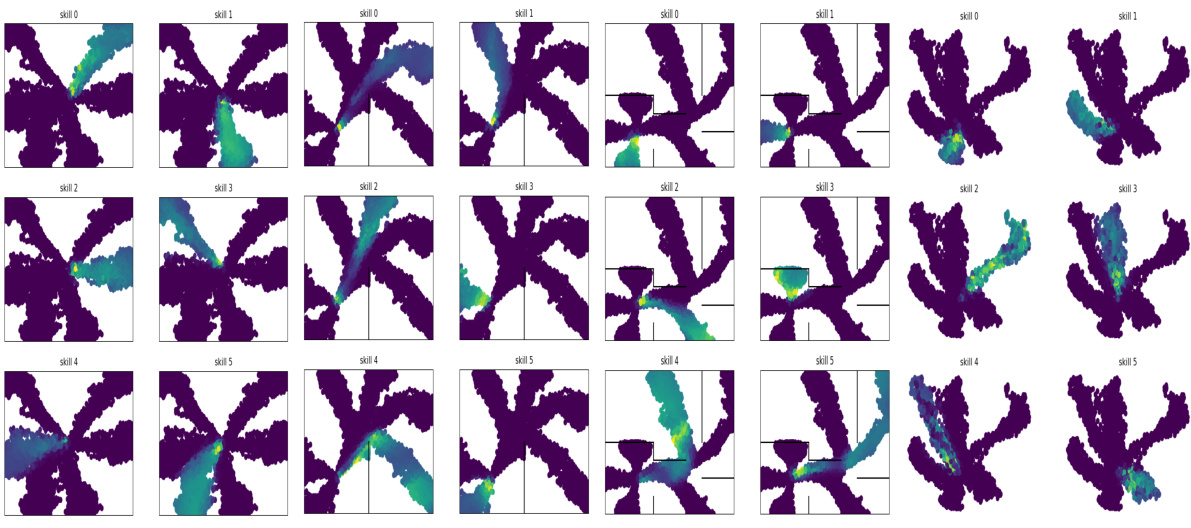

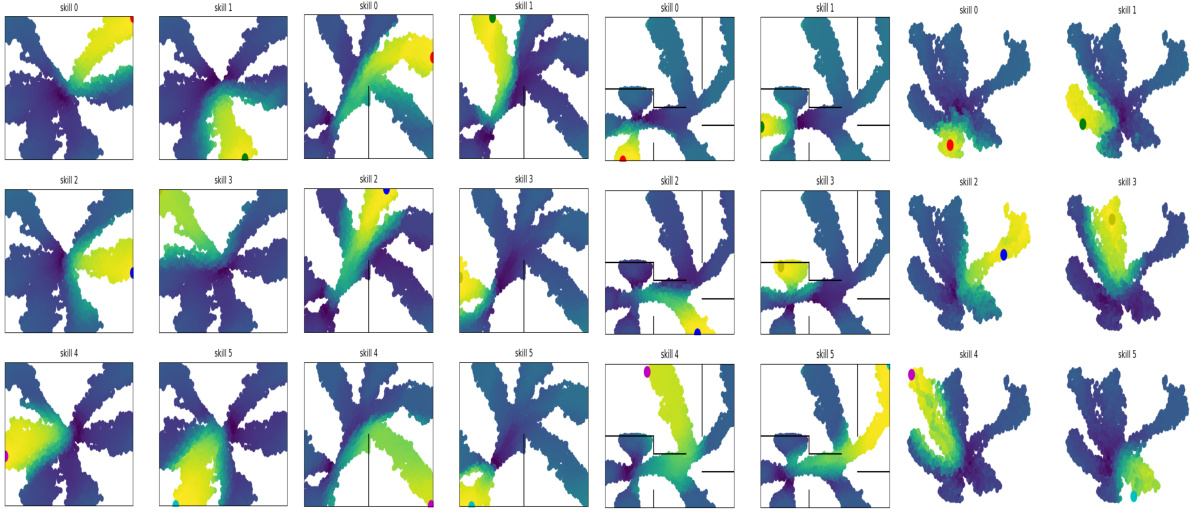

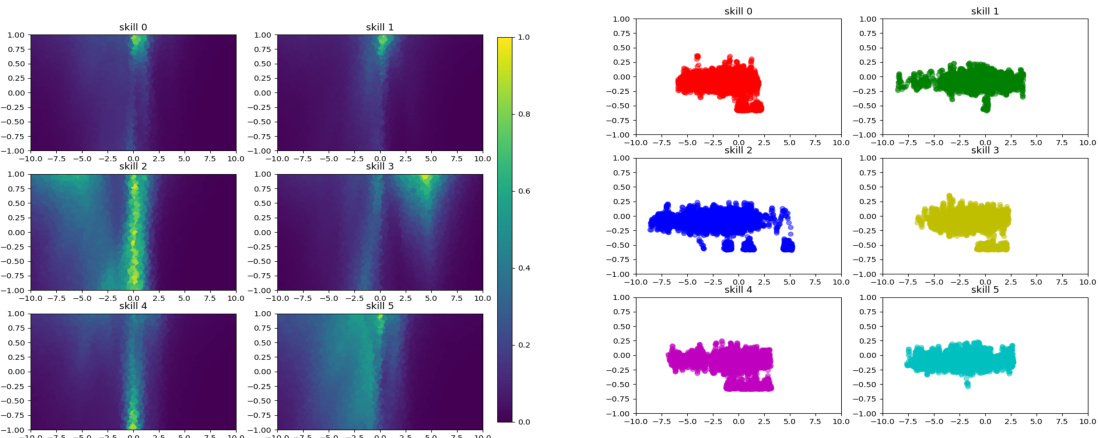

🔼 This figure visualizes the state space coverage achieved by three different algorithms (LEADS, LSD, and DIAYN) across four different tasks. The tasks include three mazes of varying complexity (Easy, U-shaped, and Hard) and a robotic control task (Fetch-Reach). Each color represents a different skill learned by the algorithm. The distribution of points for each color shows the states visited by that specific skill during the learning process. The figure helps to compare how effectively the algorithms explore and cover the state space in different environments, demonstrating the differences in the skills learned and their diversity.

read the caption

Figure 2: Skill visualisation for each algorithm. Per algorithm, the tasks are the mazes Easy (top left), U (top right), Hard (bottom left), and the control task Fetch-Reach (bottom right).

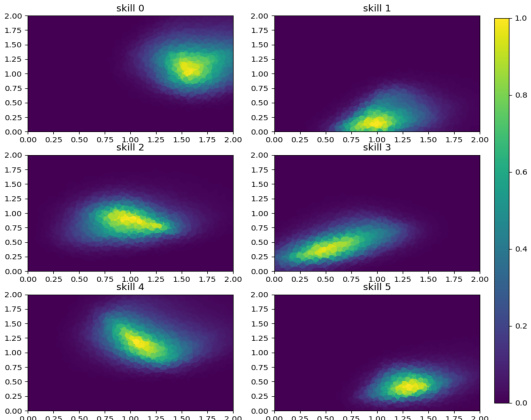

🔼 This figure visualizes the exploration capabilities of the LEADS algorithm in a high-dimensional robotic control environment called ‘Hand.’ The algorithm learns twelve distinct skills (nskill=12). The left panel shows a PCA projection of the explored states in the state space, where each color represents a different skill, highlighting how LEADS discovers skills with distinct state occupancies. The right panels illustrate the state occupancy measure (SSR) and uncertainty measure (ut) during training. The SSR, shown in the top right panel (a), indicates the probability of visiting a given state when using a specific skill. The bottom right panel (b) shows the uncertainty measure (ut), which is used to guide exploration by targeting states that are both uncertain (less frequently visited by other skills) and contribute to skill diversity. The combination of diverse skills and targeted exploration drives effective coverage of the state space.

read the caption

Figure 3: LEADS exploration of the Hand environment state space, using nskill = 12 skills

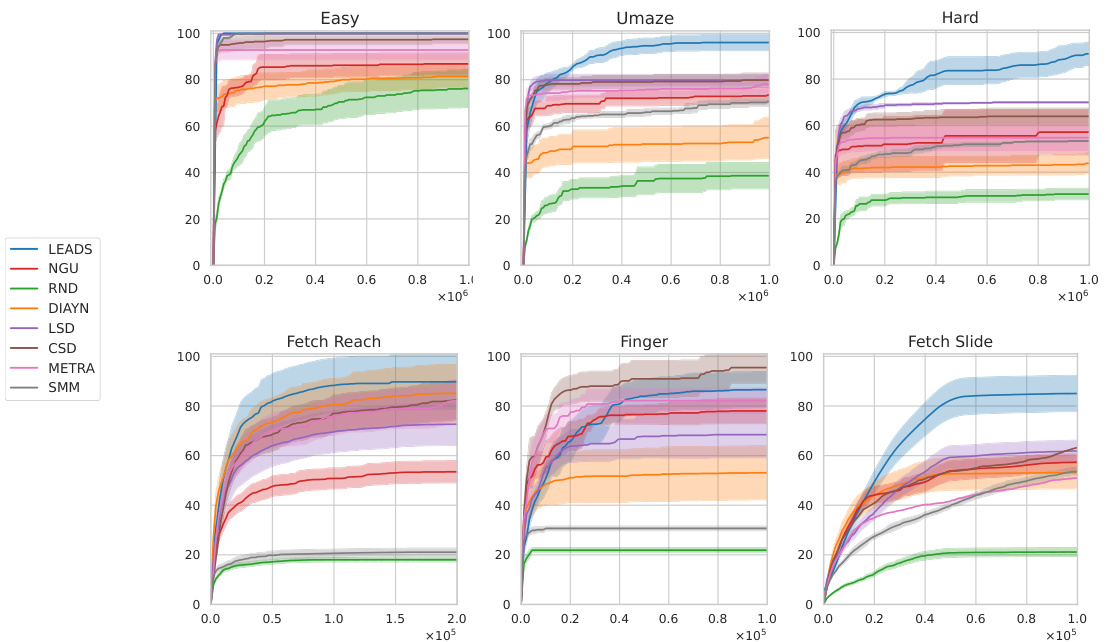

🔼 This figure shows the relative coverage achieved by different exploration algorithms across six different tasks (three mazes and three robotic control tasks) over time. The x-axis represents the number of samples collected. The y-axis represents the percentage of the state space covered. The shaded areas represent standard error across five runs. The figure illustrates the comparative performance of LEADS against several other state-of-the-art exploration algorithms in terms of state space coverage.

read the caption

Figure 5: Relative coverage evolution across six tasks. The x-axis represents the number of samples collected since the algorithm began.

🔼 This figure visualizes the state space coverage achieved by three different algorithms (LEADS, LSD, and DIAYN) on four different tasks. The tasks include three mazes of varying difficulty (Easy, U, Hard) and a robotic control task (Fetch-Reach). Each algorithm uses six skills, and the figure shows the states visited by each skill in each environment. The visualization aims to demonstrate the algorithms’ ability to generate skills that cover the state space and are distinct from one another.

read the caption

Figure 2: Skill visualisation for each algorithm. Per algorithm, the tasks are the mazes Easy (top left), U (top right), Hard (bottom left), and the control task Fetch-Reach (bottom right).

🔼 This figure visualizes the state space coverage achieved by three different algorithms (LEADS, LSD, DIAYN) across four different tasks. Each algorithm is represented by a set of six skills (Skill 0-5). The mazes (Easy, U, Hard) are 2D environments which allow for a clear visualization of each skill’s state coverage, with different colors indicating the different skills. The Fetch-Reach task is a more complex robotic control problem which is visualized in a PCA-reduced space to allow for visualization.

read the caption

Figure 2: Skill visualisation for each algorithm. Per algorithm, the tasks are the mazes Easy (top left), U (top right), Hard (bottom left), and the control task Fetch-Reach (bottom right).

🔼 This figure visualizes the state space coverage achieved by three different skill-learning algorithms (LEADS, LSD, and DIAYN) across four different tasks. For each algorithm, the figure displays a heatmap showing the spatial distribution of states visited during training. The tasks include three mazes of varying difficulty (Easy, U-shaped, and Hard) and a robotic control task (Fetch-Reach). This allows a comparison of how effectively each algorithm explores and covers the state space in different environments. The visualization provides insight into each algorithm’s skill diversity and exploration strategy.

read the caption

Figure 2: Skill visualisation for each algorithm. Per algorithm, the tasks are the mazes Easy (top left), U (top right), Hard (bottom left), and the control task Fetch-Reach (bottom right).

🔼 This figure visualizes the state space coverage achieved by three different algorithms (LEADS, LSD, and DIAYN) on four different tasks. The tasks consist of three mazes of varying difficulty (Easy, U, Hard) and a robotic control task (Fetch-Reach). Each algorithm is shown to have 6 skills, with each skill’s state space coverage represented by a unique color. The figure shows how effectively each algorithm explores the state space of each task by illustrating how well the skills cover the different areas of each environment. The visualization helps to understand the differences in the algorithms’ exploration strategies and their ability to discover diverse skills that uniformly cover the state space.

read the caption

Figure 2: Skill visualisation for each algorithm. Per algorithm, the tasks are the mazes Easy (top left), U (top right), Hard (bottom left), and the control task Fetch-Reach (bottom right).

🔼 This figure visualizes the state space coverage achieved by LEADS, LSD, and DIAYN algorithms across four different tasks: three mazes of increasing difficulty (Easy, U, Hard) and a robotic control task (Fetch-Reach). Each algorithm is represented with a separate set of visualizations, showing the spatial distribution of states visited by each of its six skills (Skill 0-Skill 5) in each environment. This allows for a visual comparison of the algorithms’ exploration capabilities and skill diversity in terms of state space coverage. The mazes allow for a direct 2D visualization of the explored space. For the Fetch-Reach task, a more complex 10-dimensional state space is projected into a 2D representation using PCA to aid visualization.

read the caption

Figure 2: Skill visualisation for each algorithm. Per algorithm, the tasks are the mazes Easy (top left), U (top right), Hard (bottom left), and the control task Fetch-Reach (bottom right).

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the final coverage percentages achieved by various exploration methods across different environments (mazes and robotic control tasks). The percentage represents the proportion of the state space visited by each algorithm. Statistical significance is indicated by bolding, showing when a method significantly outperforms others (p<0.05). Appendix B provides the full t-test results for a more detailed statistical analysis.

read the caption

Table 1: Final coverage percentages for each method on each environments. Bold indicates when a single method is statistically superior to all other methods (p < 0.05). Full T-test results are presented in Appendix B.

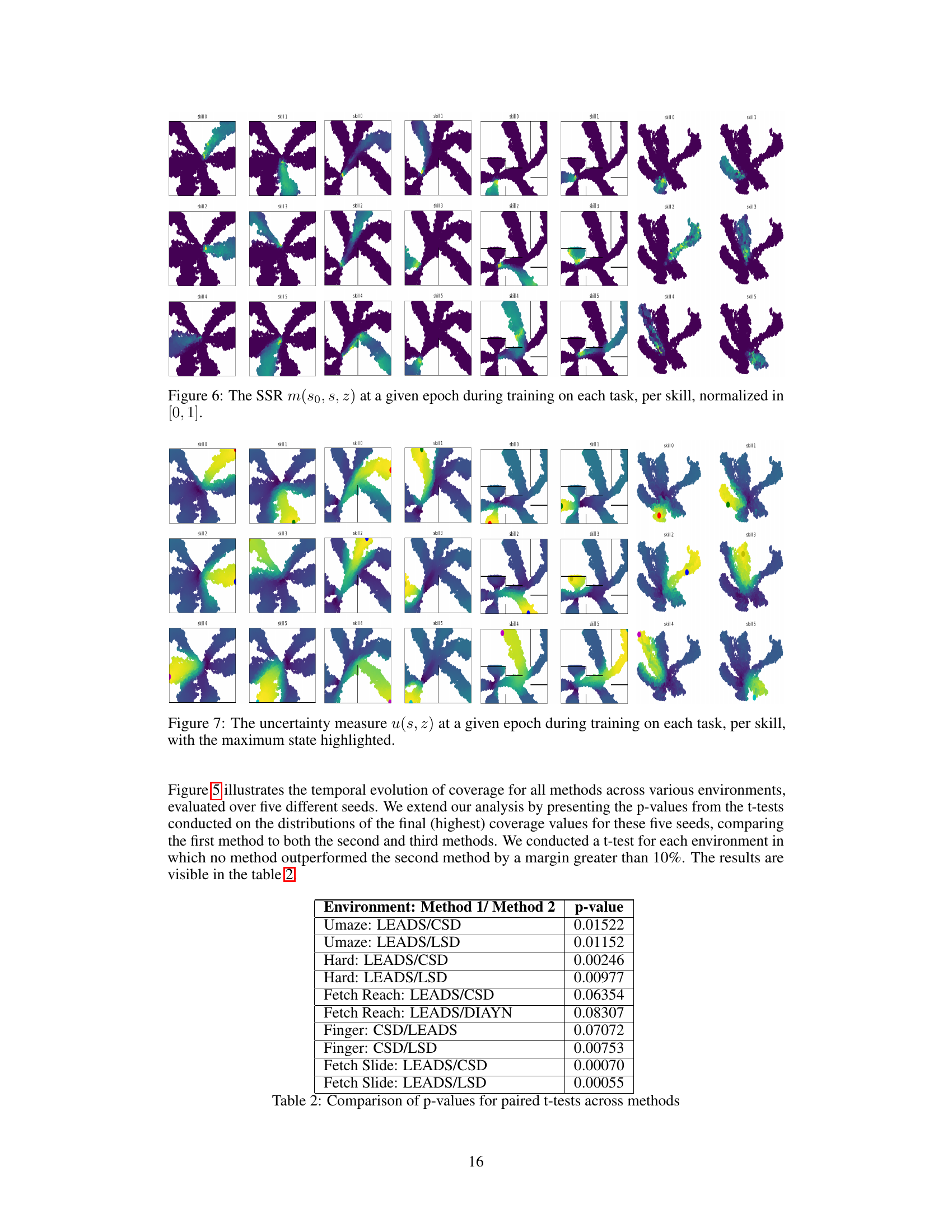

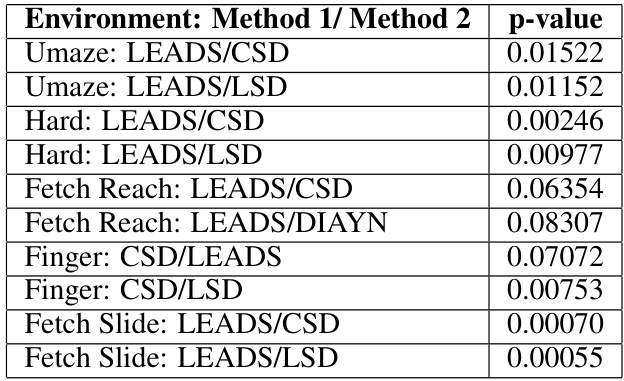

🔼 This table presents the p-values from paired t-tests comparing the performance of LEADS against other methods in different environments. The p-values indicate the statistical significance of the difference in coverage between LEADS and the other methods. A low p-value (typically below 0.05) suggests a statistically significant difference, meaning the difference in performance is unlikely due to random chance. The table shows that LEADS significantly outperforms other methods in several cases (low p-values).

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of p-values for paired t-tests across methods

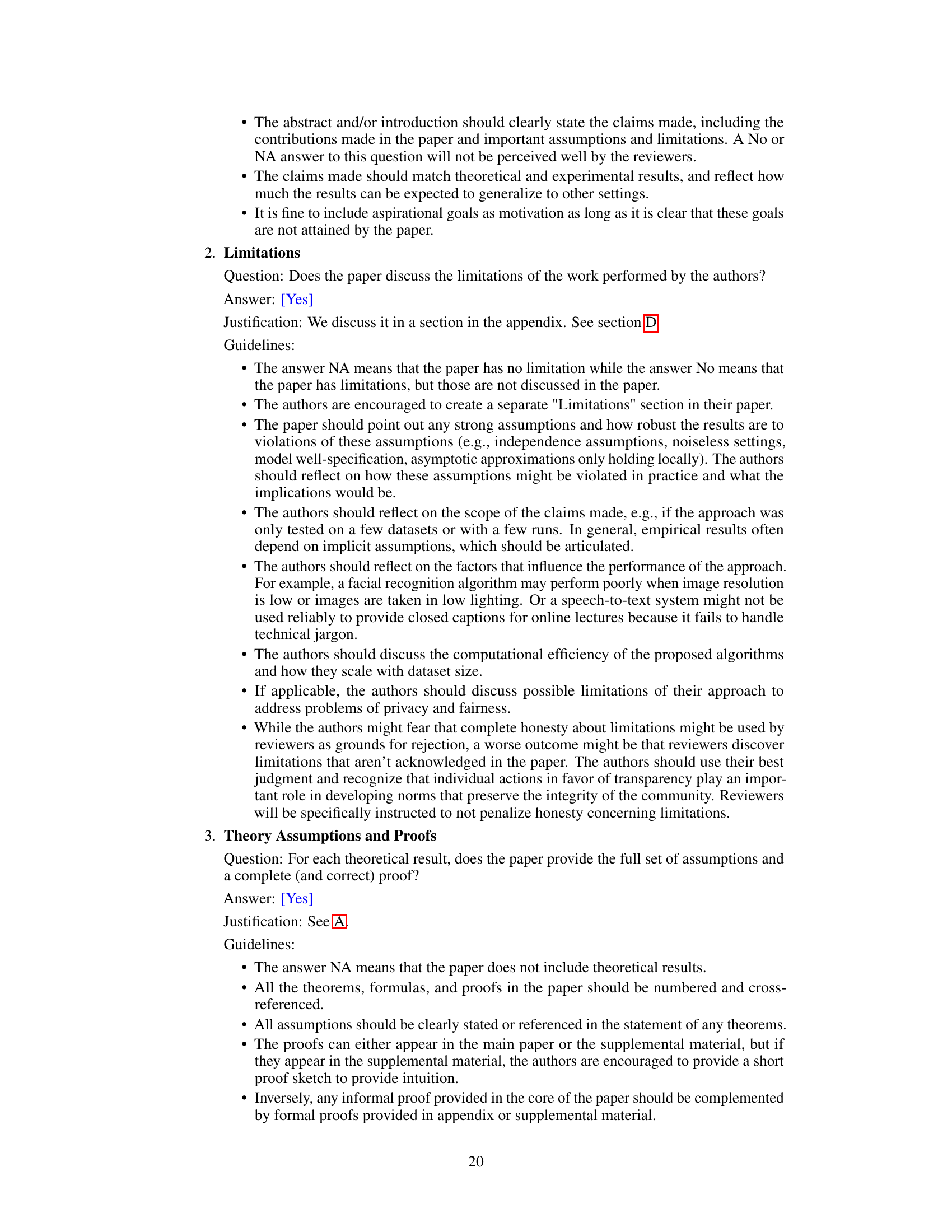

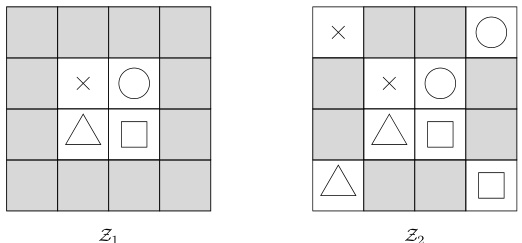

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameters used in the LEADS algorithm and their corresponding values. The hyperparameters control various aspects of the algorithm, including the number of skills, the dimensionality of the skill embedding space, the relative importance of the entropy bonus, the discount factor, the learning rates for different parts of the network, and the batch sizes used during training.

read the caption

Table 3: Hyperparameters used for LEADS

🔼 This table details the architecture of the two neural networks used in the LEADS algorithm: the classifier network and the actor network. For each network, it specifies the number of layers, the type of layer (dense), the input dimensions, the output dimensions, and the activation function used in each layer. The input dimensions reflect the input data fed into each network layer for processing. The output dimensions indicate the number of neurons in the output layer. Activation functions introduce non-linearity into the network, enabling it to learn complex relationships in the data.

read the caption

Table 4: Structure of the Classifier and Actor Networks

Full paper#