↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current deep learning models are often trained using first-order optimization methods due to the computational cost and difficulty of implementing second-order methods, and the generalization properties of second-order methods are not well understood. This paper focuses on the Gauss-Newton method, which is a second-order optimization method, and investigates its generalization properties in deep reversible neural networks. The authors find that while Gauss-Newton shows faster convergence during training, compared to first-order methods, it fails to generalize well to unseen data.

The researchers found that the poor generalization is due to a phenomenon called “lazy training.” In lazy training, the model’s internal representation does not change significantly during training. This means that the model does not learn new features that would help it generalize to unseen data. This is in contrast to first-order methods such as Adam, which exhibit better generalization and more significant changes in internal representations during training. The study also provides an efficient way to compute exact Gauss-Newton updates in deep reversible architectures and highlights the need for further investigation into the generalization properties of second-order optimization methods in deep learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it presents the first exact and tractable implementation of Gauss-Newton optimization in deep learning, overcoming previous limitations of approximations. It reveals unexpected generalization issues with exact GN, challenging existing theories and prompting further research into second-order optimization methods. The findings may significantly impact the development of more efficient and robust training techniques.

Visual Insights#

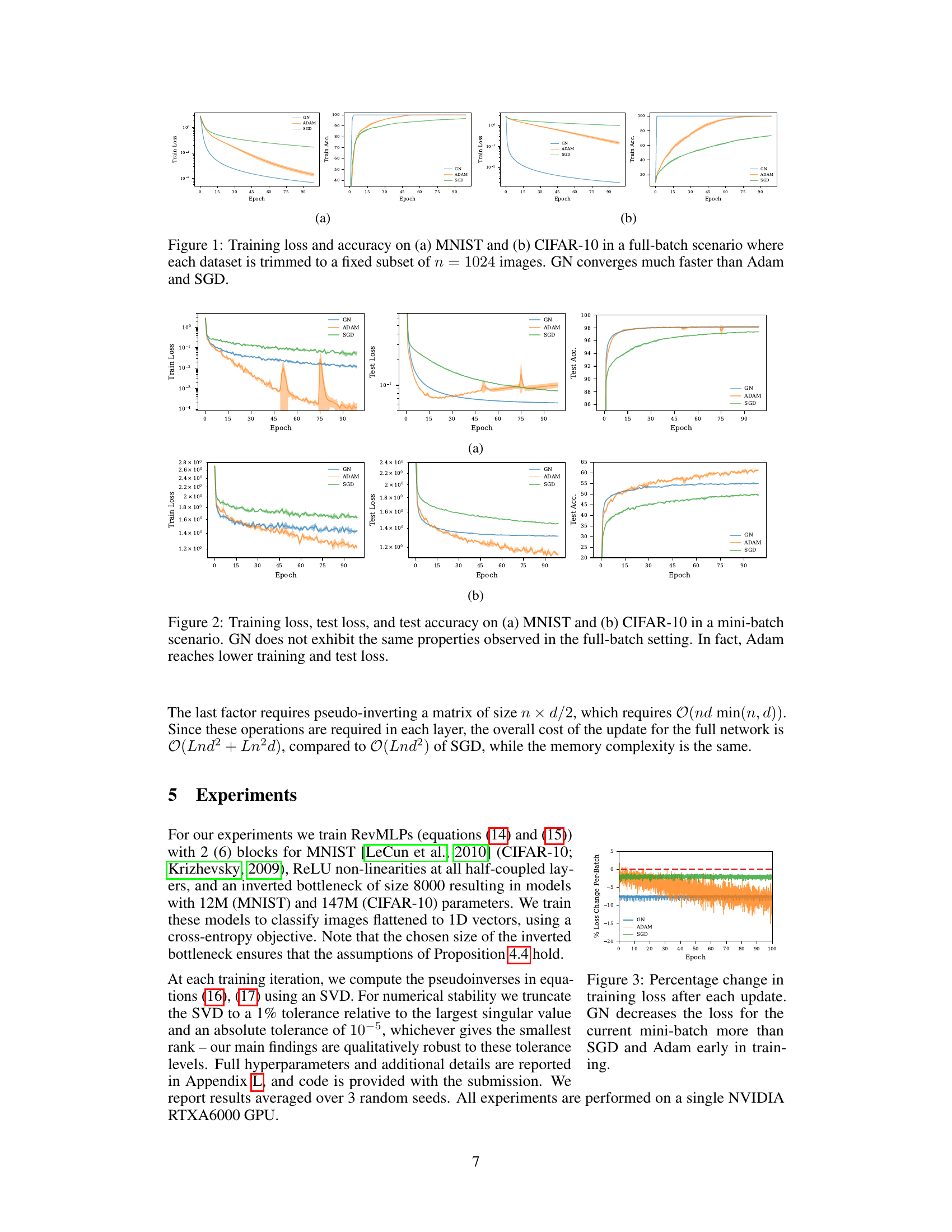

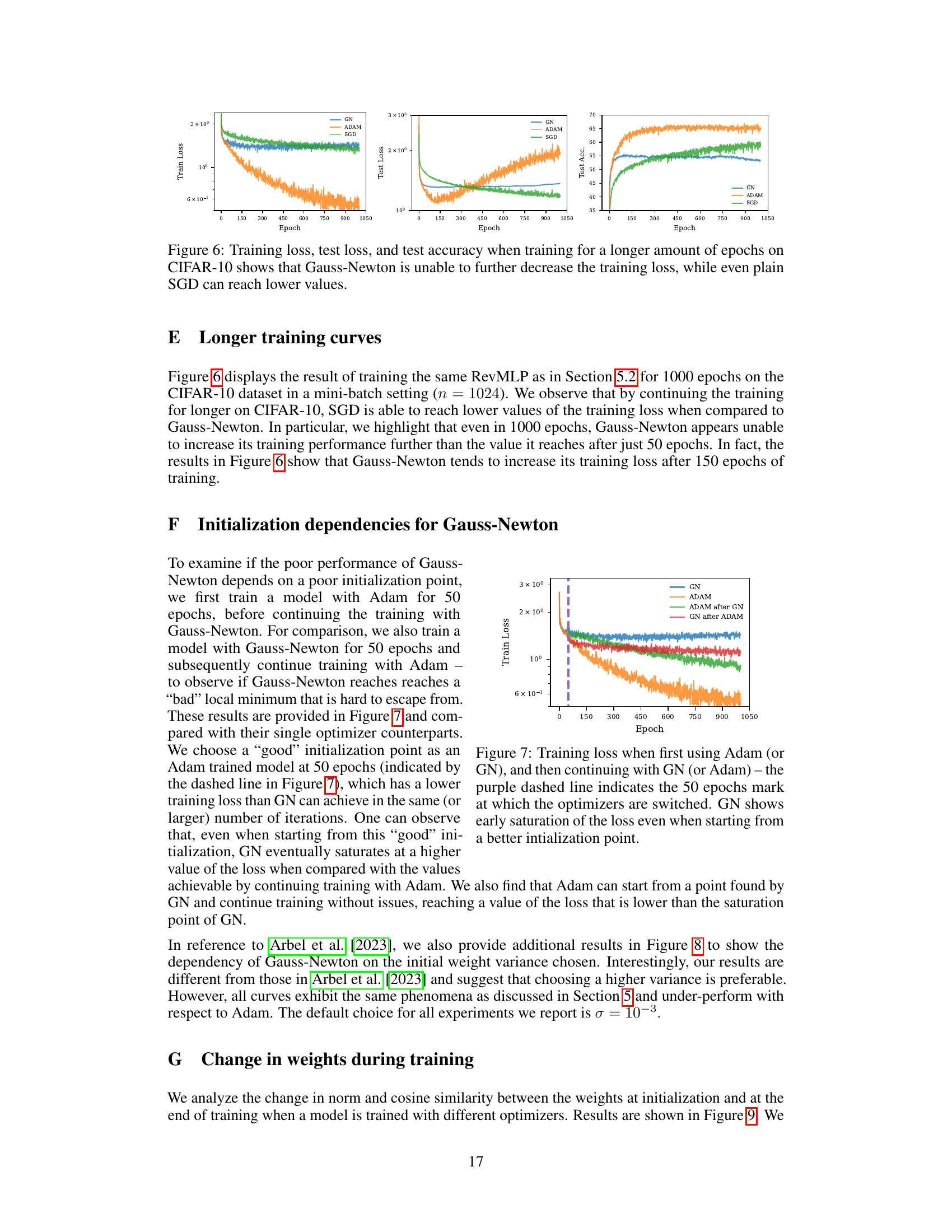

This figure compares the training loss and accuracy of three different optimizers (GN, Adam, and SGD) on MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets. The key observation is that the Gauss-Newton (GN) optimizer converges significantly faster than both Adam and SGD in a full-batch setting where datasets were reduced to 1024 images. The figure highlights the superior convergence speed of GN in this specific setting.

In-depth insights#

GN Optimization#

The study explores Gauss-Newton (GN) optimization, a second-order method, within the context of deep learning. It challenges the common belief that GN always generalizes well by demonstrating that exact GN optimization in deep reversible architectures exhibits poor generalization. The researchers find that despite achieving rapid initial progress on training loss, GN updates overfit individual mini-batches, hindering performance on unseen data. This overfitting is linked to the neural tangent kernel (NTK) remaining almost unchanged during training, indicating that the network’s internal representations do not evolve significantly. The study’s unique contribution lies in using reversible architectures which enables the computation of exact, rather than approximate, GN updates. This allows for a more precise assessment of GN’s generalization capabilities and ultimately reveals its limitations when dealing with stochastic mini-batch settings, suggesting that further regularization strategies might be needed to improve its generalization performance.

Reversible Nets#

Reversible neural networks offer a compelling approach to training deep models by eliminating the need to store activations during the forward and backward passes. This memory efficiency stems from the inherent invertibility of the network architecture, enabling the computation of gradients using only the inputs and outputs. This significantly reduces memory consumption and makes it possible to train significantly deeper and wider networks than would be feasible using traditional architectures. However, the design and implementation of reversible networks present challenges. Constructing reversible networks requires careful consideration of the layer design and the choice of activation functions to ensure the invertibility property holds throughout the network. Furthermore, the computational cost of inverting the network can still be significant, potentially offsetting some of the memory savings. The impact of reversibility on the optimization landscape and generalization performance requires further investigation. While theoretically promising, the practical applicability and impact of reversible nets hinges on addressing these design and computational tradeoffs.

Lazy Training#

The concept of “lazy training” in the context of deep learning signifies that a model’s parameters change minimally during training, resulting in its neural representations remaining largely unchanged from initialization. This behavior, often observed in overparameterized models trained with certain optimizers such as Gauss-Newton, contrasts sharply with models that actively learn new representations. Lazy training can lead to poor generalization, as the model fails to adapt to unseen data beyond its initial representation capabilities. This phenomenon is particularly significant given the pursuit of efficient second-order optimization techniques. While such methods might accelerate training loss reduction on seen data, their inability to meaningfully alter the underlying representations can hinder generalization and limit the model’s overall performance.

Generalization Limits#

The concept of ‘Generalization Limits’ in the context of deep learning is crucial. It explores why models, despite achieving high accuracy on training data, often struggle with unseen data. This is a major obstacle to the widespread application of deep learning. Overfitting, where the model memorizes the training set rather than learning underlying patterns, is a key factor. Regularization techniques, like weight decay or dropout, aim to mitigate overfitting but have limitations, particularly in very deep and complex architectures. The inherent complexity of the model and its capacity to represent extremely intricate functions can make it prone to finding spurious correlations in the training data. Furthermore, data biases can limit a model’s ability to generalize to populations beyond the training data’s characteristics. Understanding and overcoming generalization limits remains a primary focus of deep learning research, involving both theoretical improvements in model design and the development of more robust training methodologies. The interplay between model capacity, data quality, and training strategies is essential for improving generalization.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the tractable exact Gauss-Newton method to a broader class of deep learning architectures beyond reversible networks is crucial for wider applicability. Investigating different regularization strategies within the exact GN framework, such as weight decay or Jacobian preconditioning, could mitigate overfitting issues observed in mini-batch settings. A deeper theoretical understanding of why exact GN struggles with generalization, especially in comparison to first-order methods, is needed. This could involve analyzing the interplay between the NTK, neural representations, and the optimization dynamics. Finally, empirical evaluation on a wider range of datasets and tasks is essential to confirm the findings and assess the robustness of the proposed method.

More visual insights#

More on figures

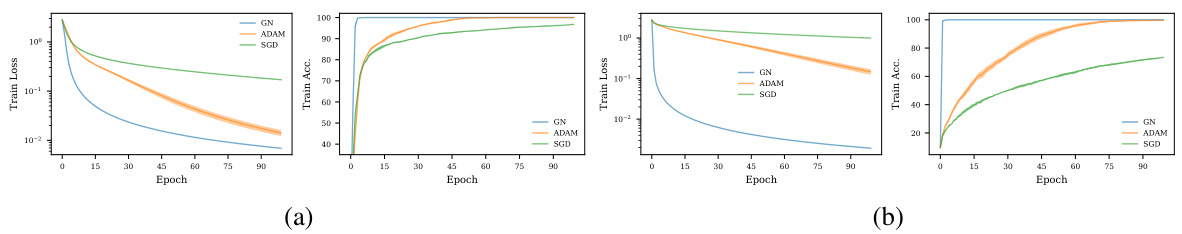

This figure compares the performance of Gauss-Newton (GN), Adam, and SGD optimizers on MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets using mini-batch training. It shows that unlike the full-batch scenario (Figure 1), GN does not outperform Adam and SGD in this setting. GN exhibits rapid saturation of training and test loss, while Adam achieves lower loss values. This demonstrates that the superior performance of GN observed in the full-batch setting does not translate to the mini-batch setting.

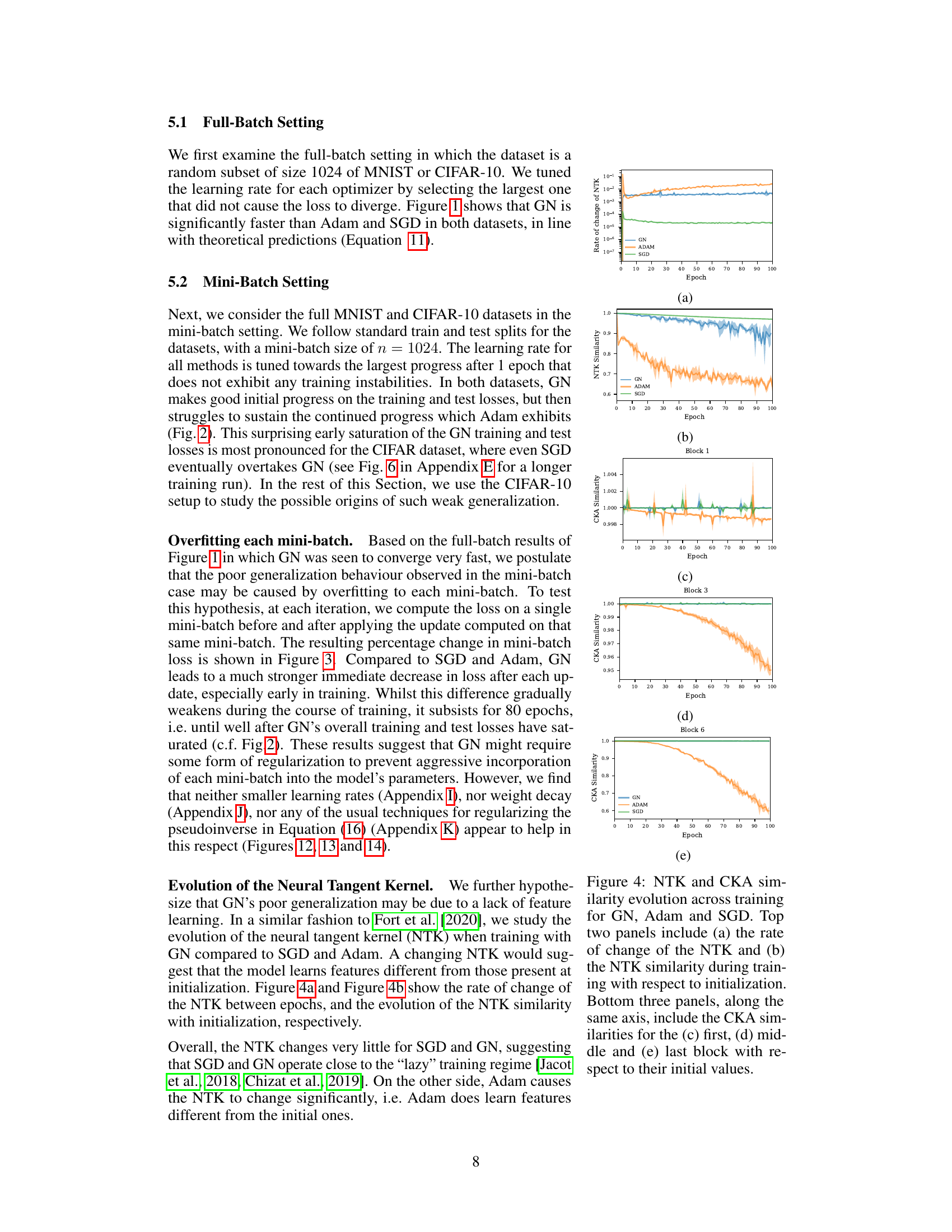

This figure shows the percentage change in the training loss after each update for three different optimizers: Gauss-Newton (GN), Adam, and SGD. The results demonstrate that GN initially reduces the loss more significantly on each mini-batch than Adam and SGD, especially in the early stages of training. This difference gradually diminishes over time, but persists even after the overall training and test losses have saturated.

This figure compares the evolution of the Neural Tangent Kernel (NTK) and the Centered Kernel Alignment (CKA) across training for three different optimizers: Gauss-Newton (GN), Adam, and SGD. The top panel (a) shows the rate of change of the NTK over epochs, indicating how much the NTK changes during training. Panel (b) displays the NTK similarity to the initial NTK across epochs, showing how similar the learned NTK is to the initial one. The bottom three panels (c-e) show the CKA similarity for three different blocks (first, middle, and last) of the network to their initial CKA values over epochs. These plots illustrate the evolution of neural representations during training and how these representations change with different optimizers.

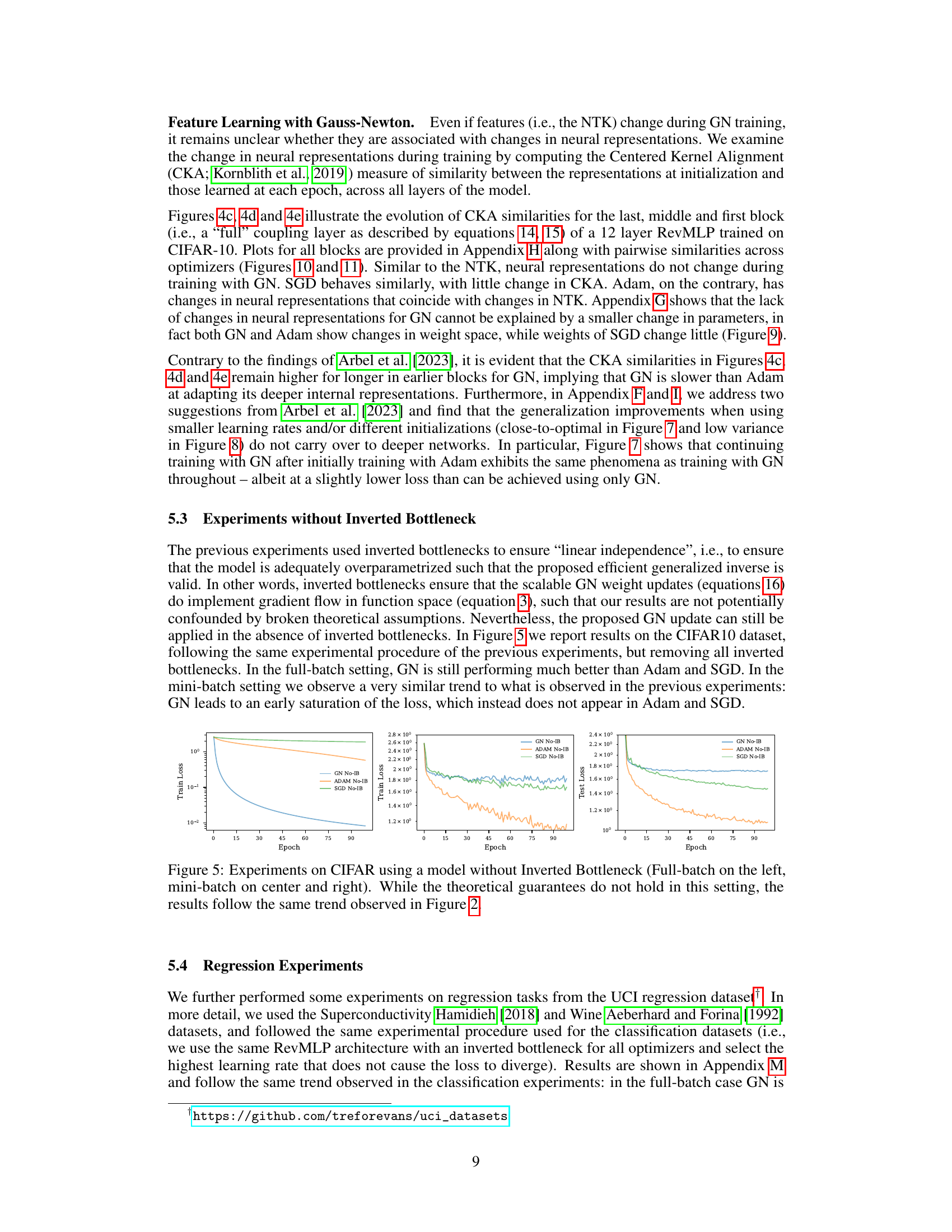

This figure shows the results of experiments conducted on the CIFAR-10 dataset using RevMLPs without inverted bottlenecks. The left panel displays results from a full-batch training setting, while the center and right panels show results from a mini-batch setting. Despite the theoretical guarantees not applying without inverted bottlenecks, the results show a consistent trend with Figure 2, demonstrating that the poor generalization performance of Gauss-Newton in mini-batch settings persists even without this specific architectural feature.

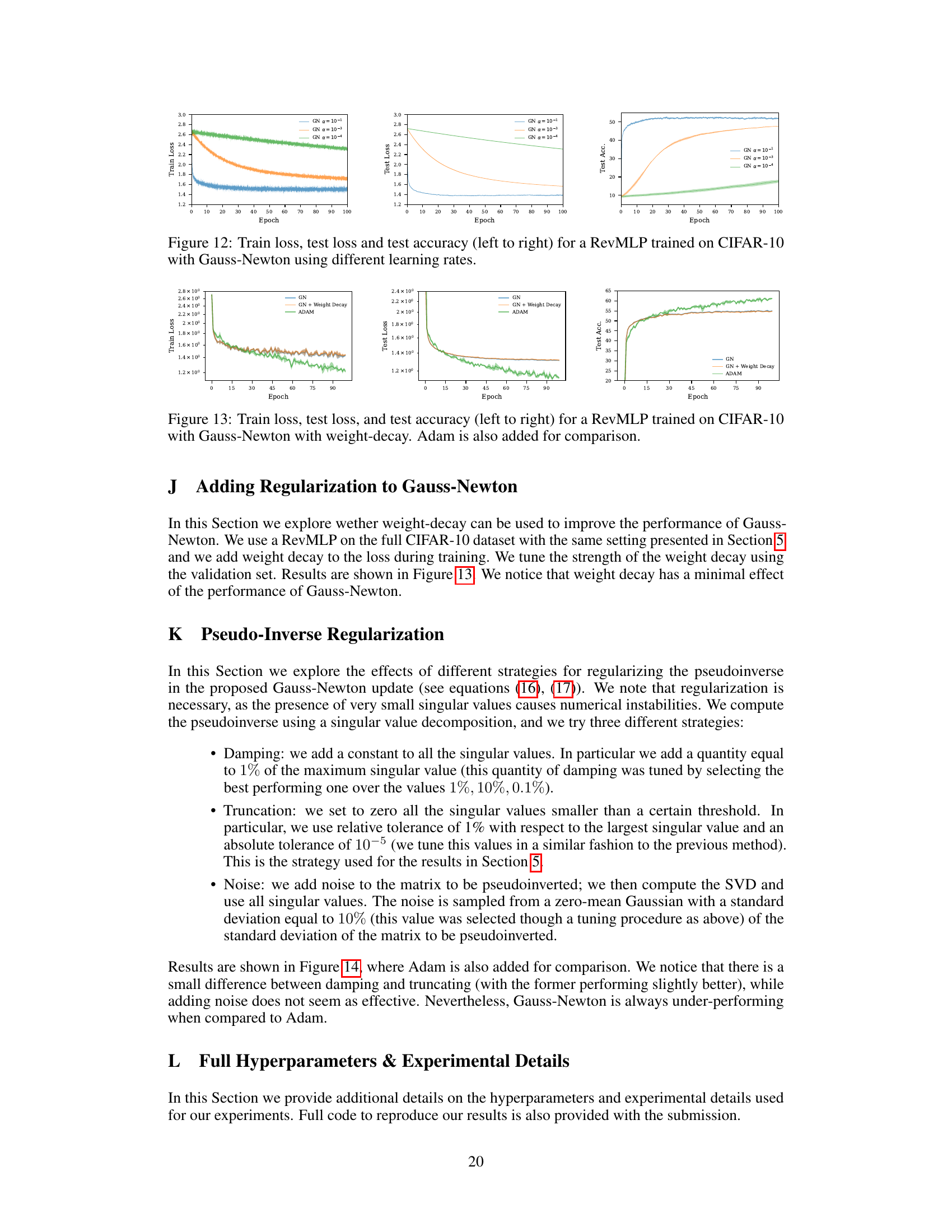

This figure shows the training and testing results for three different optimizers (GN, Adam, and SGD) on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The key takeaway is that while Gauss-Newton initially performs well and converges much faster than the others, it fails to further reduce the loss even after prolonged training, unlike Adam and even SGD, which continue to improve after many epochs. This highlights a significant limitation of GN in the mini-batch setting, specifically its inability to continue learning useful features after initially overfitting to the mini-batches.

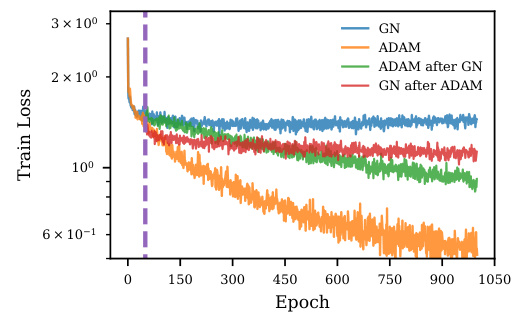

This figure displays the training loss curves when using two different optimizers sequentially. First, a model is trained for 50 epochs using either Adam or Gauss-Newton. Then, training continues for an additional 1000 epochs, switching to the other optimizer. The purple dashed vertical line marks the 50-epoch transition point. The plot shows that Gauss-Newton exhibits early saturation of the training loss, even when initialized with weights from a well-trained Adam model, indicating its limited ability to escape from suboptimal solutions or improve generalization despite potentially good initial progress.

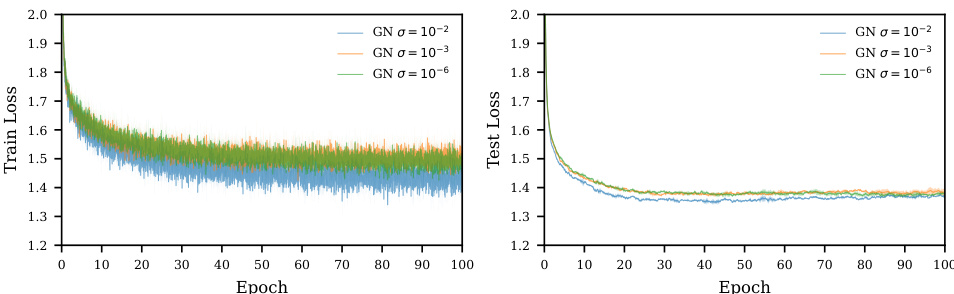

This figure shows the training and test loss curves for Gauss-Newton (GN) optimization with different weight initialization variances (σ = 10⁻², 10⁻³, 10⁻⁶). The results illustrate the impact of weight initialization on the performance of GN, especially in the context of generalization. It demonstrates how different variances affect the training and test loss, highlighting the sensitivity of GN’s performance to initialization parameters.

This figure shows the cosine similarity between the weights at initialization and at the end of training for different optimizers. The results indicate that Adam and Gauss-Newton (GN) exhibit similar behavior in weight space, while SGD shows considerably less change. The ’layer’ designation refers to a half-coupled layer within the reversible blocks of the network architecture.

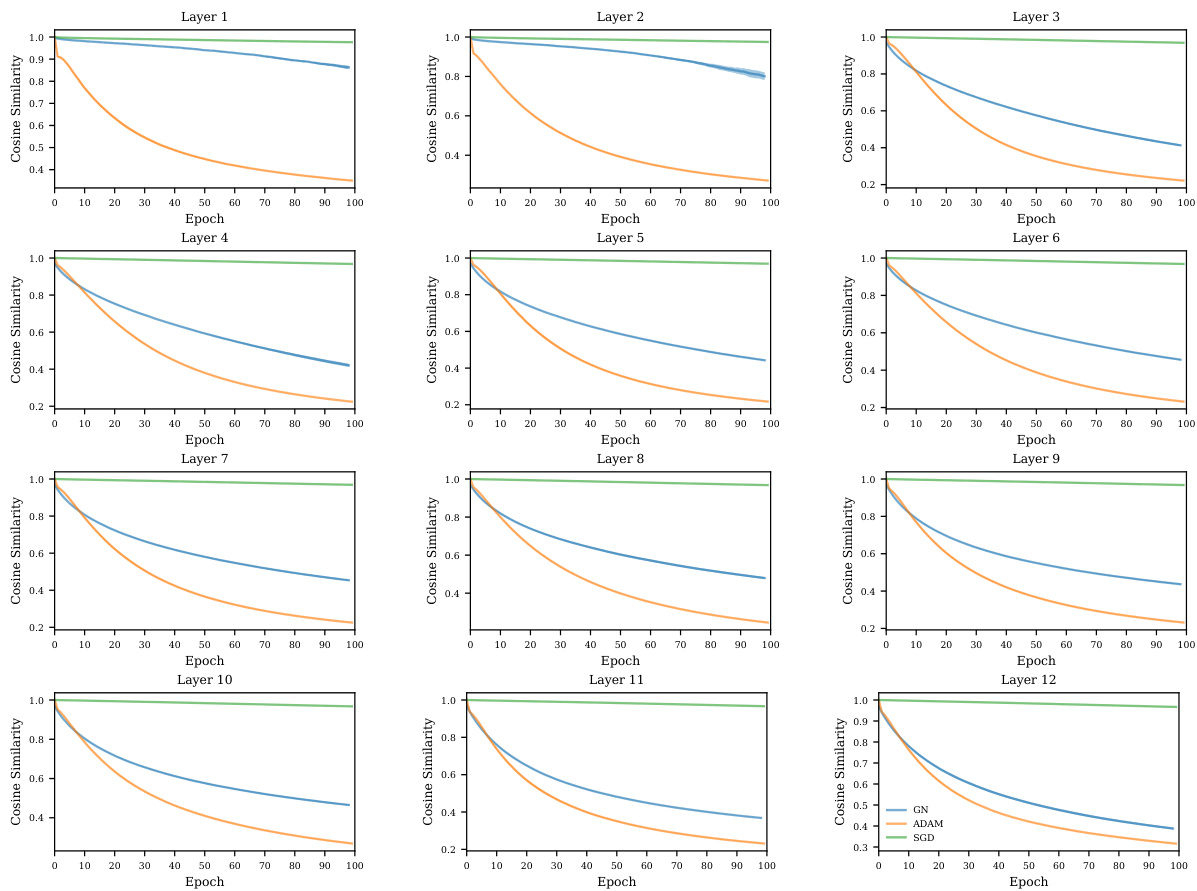

This figure shows the evolution of the Centered Kernel Alignment (CKA) similarity between the neural network representations at initialization and at each epoch during training, for three different optimizers: Gauss-Newton (GN), Adam, and SGD. The results are presented for six blocks of a neural network trained on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The figure demonstrates that GN and SGD maintain a high CKA similarity throughout training, indicating that their learned representations remain very close to their initial representations. In contrast, Adam shows a significant decrease in CKA similarity over time, suggesting that it learns features that are different from those present at initialization.

This figure shows the evolution of the Centered Kernel Alignment (CKA) similarity between the neural network representations at initialization and at different epochs during training, for three different optimizers: Gauss-Newton (GN), Adam, and SGD. The results indicate that GN and SGD maintain a high similarity to their initial feature representations throughout training, suggesting that they operate in a ’lazy’ training regime where they do not significantly change their feature representations. In contrast, Adam shows a much greater change in CKA similarity over time, indicating a substantial change in feature representations.

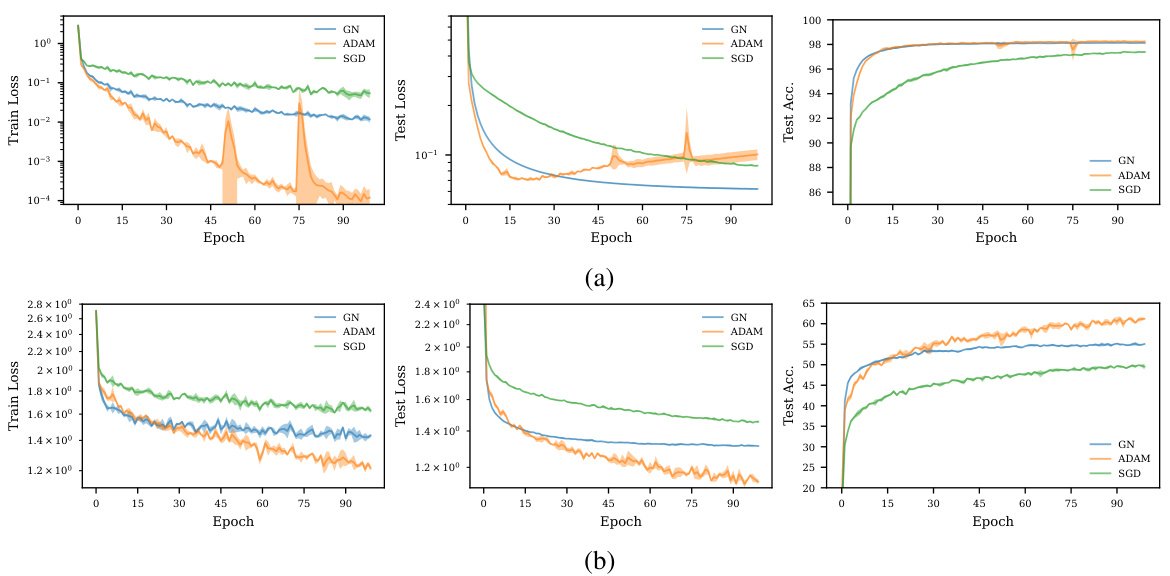

This figure shows the training and test performance of a RevMLP model trained on CIFAR-10 using Gauss-Newton optimization with different learning rates. The three subplots display the training loss, test loss, and test accuracy over 100 epochs. Each line represents a different learning rate (10⁻¹, 10⁻³, 10⁻⁴). The figure illustrates the effect of the learning rate on the convergence and generalization performance of Gauss-Newton in this specific experimental setting.

This figure compares the training and testing performance of three optimizers on the CIFAR-10 dataset: Gauss-Newton (GN), GN with weight decay, and Adam. The plots show that adding weight decay to the GN optimizer does not significantly improve its performance, and it still underperforms Adam, particularly in terms of generalization as measured by test accuracy.

This figure compares the performance of Gauss-Newton with different regularization techniques for the pseudoinverse on the CIFAR-10 dataset. It shows the training loss, test loss, and test accuracy for Gauss-Newton with truncation, damping, and noise added to the pseudoinverse, and compares the results to the Adam optimizer. The figure illustrates how different regularization approaches affect the training and generalization of the Gauss-Newton method.

This figure compares the performance of Gauss-Newton (GN), Adam, and SGD optimizers on MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets using mini-batch training. It shows training loss, test loss, and test accuracy over epochs. The key observation is that GN, unlike its full-batch behavior (shown in Figure 1), fails to maintain its superior performance and is even outperformed by Adam, which achieves lower training and testing losses.

Full paper#