↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Continual learning, particularly class incremental learning (CIL), faces the challenge of catastrophic forgetting – the tendency of models to forget previously learned information when learning new data. Generalized CIL (GCIL) tackles a more realistic scenario where incoming data includes mixed categories and unknown data distributions. Existing GCIL methods either struggle with poor performance or compromise data privacy by storing previous data samples (exemplars).

This paper introduces Generalized Analytic Continual Learning (GACL), a new exemplar-free method for GCIL. GACL uses analytic learning, a gradient-free approach, to obtain a closed-form solution. This solution cleverly decomposes incoming data into exposed and unexposed classes, ensuring a weight-invariant property. This means that the model’s weights don’t change drastically between incremental learning steps, effectively mitigating catastrophic forgetting and achieving an equivalence between incremental and joint training. Extensive experiments show that GACL significantly outperforms other methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on continual learning, especially in real-world scenarios with mixed data and uneven distributions. The proposed GACL method offers a novel, exemplar-free approach that significantly improves performance while addressing privacy concerns. This work opens avenues for further research in analytic learning and its applications to other continual learning challenges.

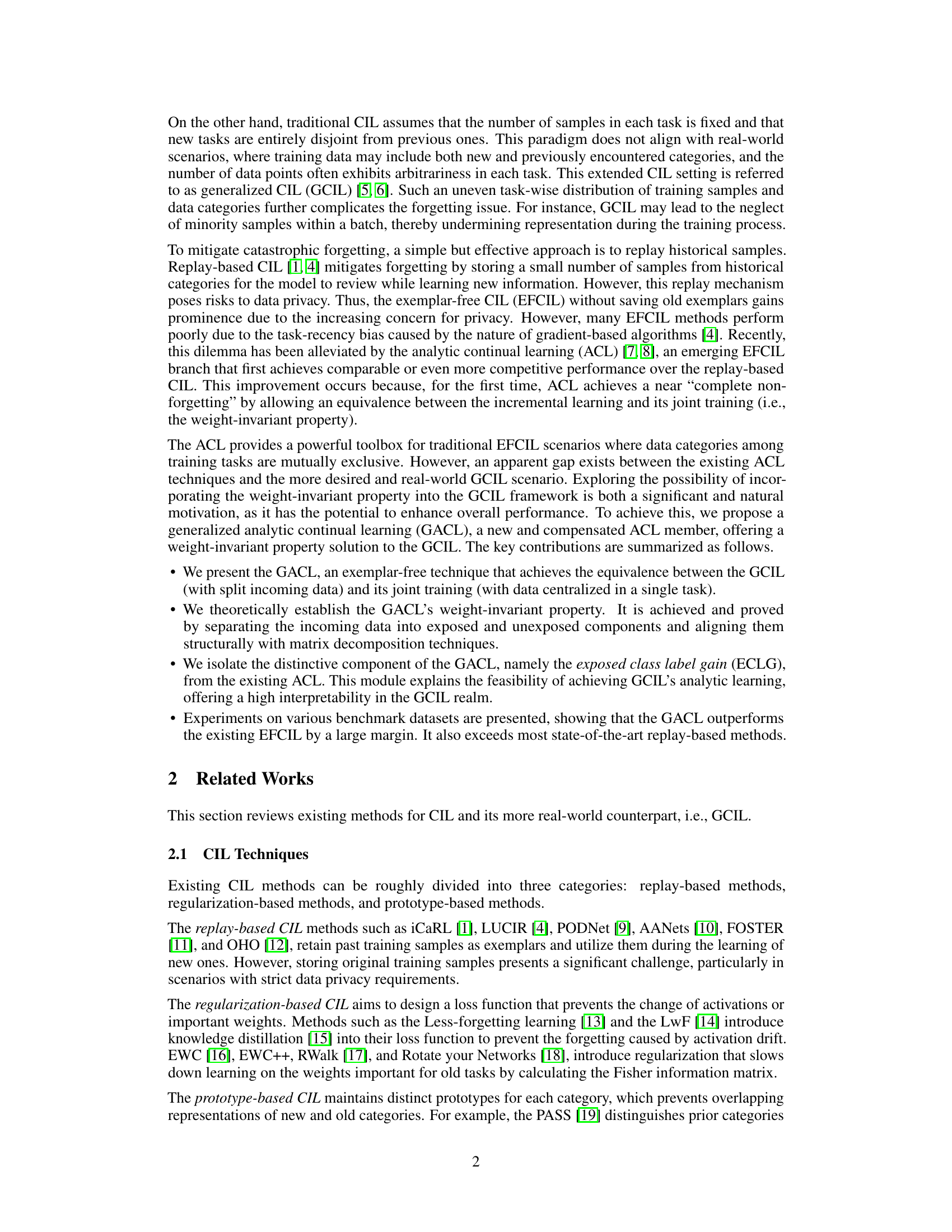

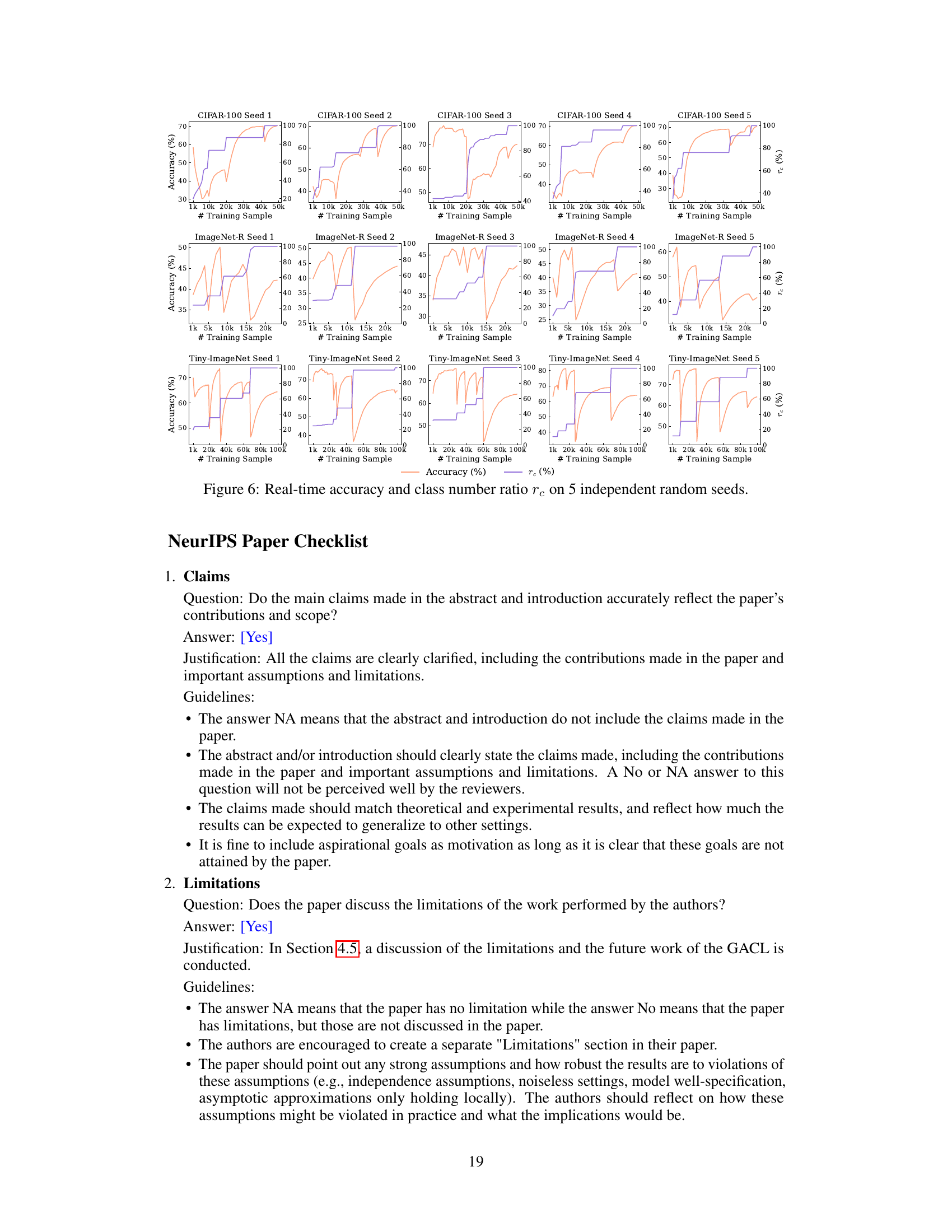

Visual Insights#

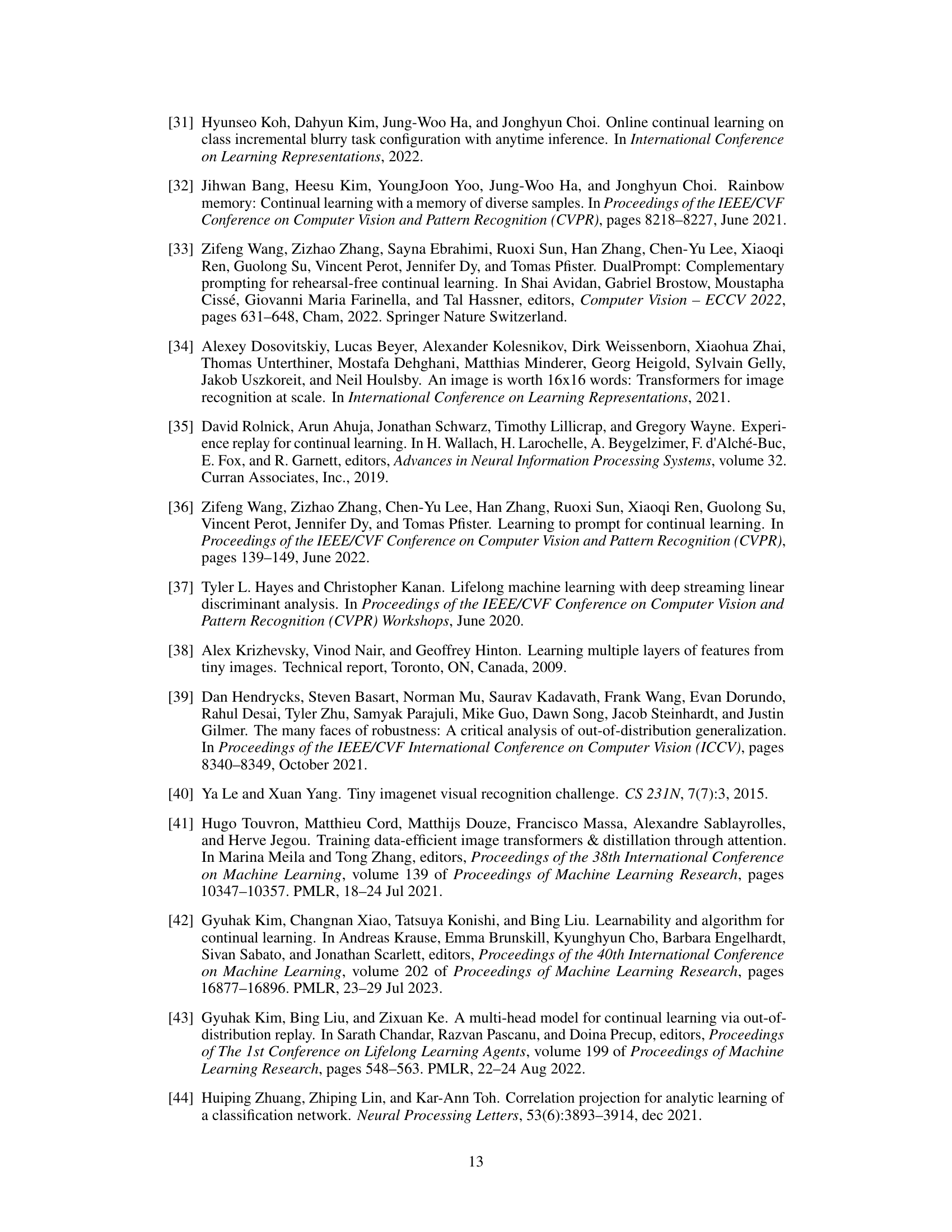

This figure provides a high-level overview of the Generalized Analytic Continual Learning (GACL) method. It breaks down the process into three main stages: 1) Splitting the input data into exposed and unexposed classes; 2) Extracting features using a pre-trained ViT and buffer layer; and 3) Recursive weight updates using exposed and unexposed class information and an autocorrelation memory matrix.

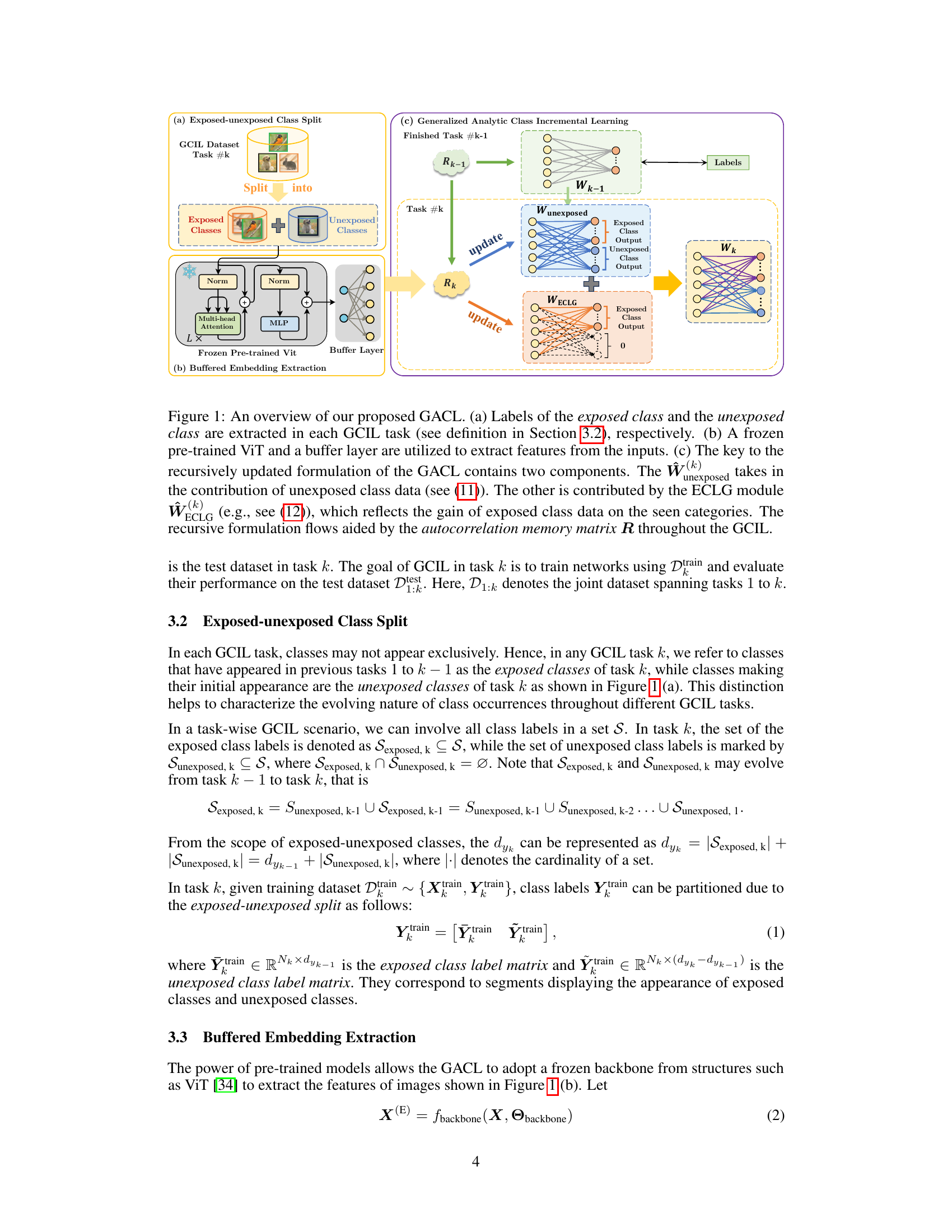

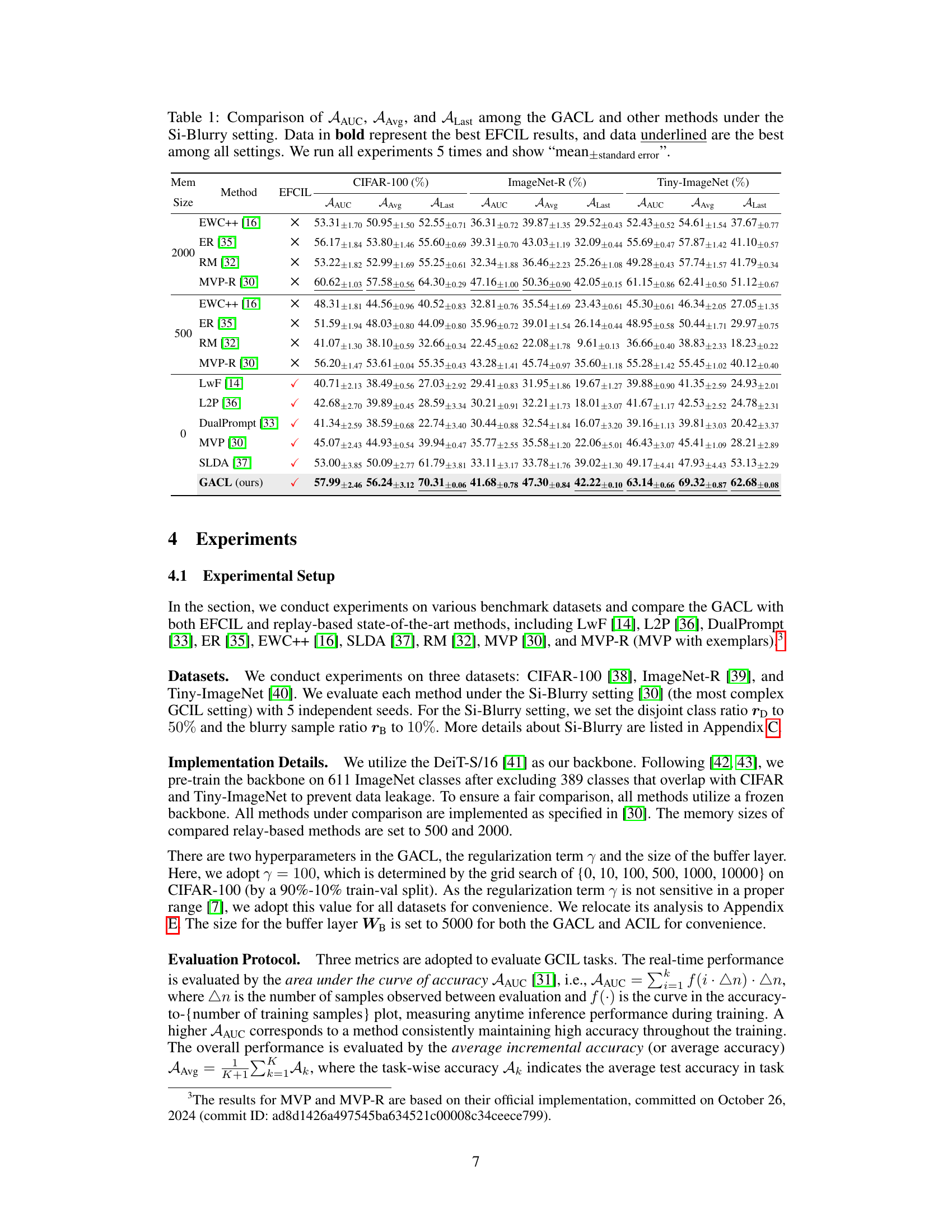

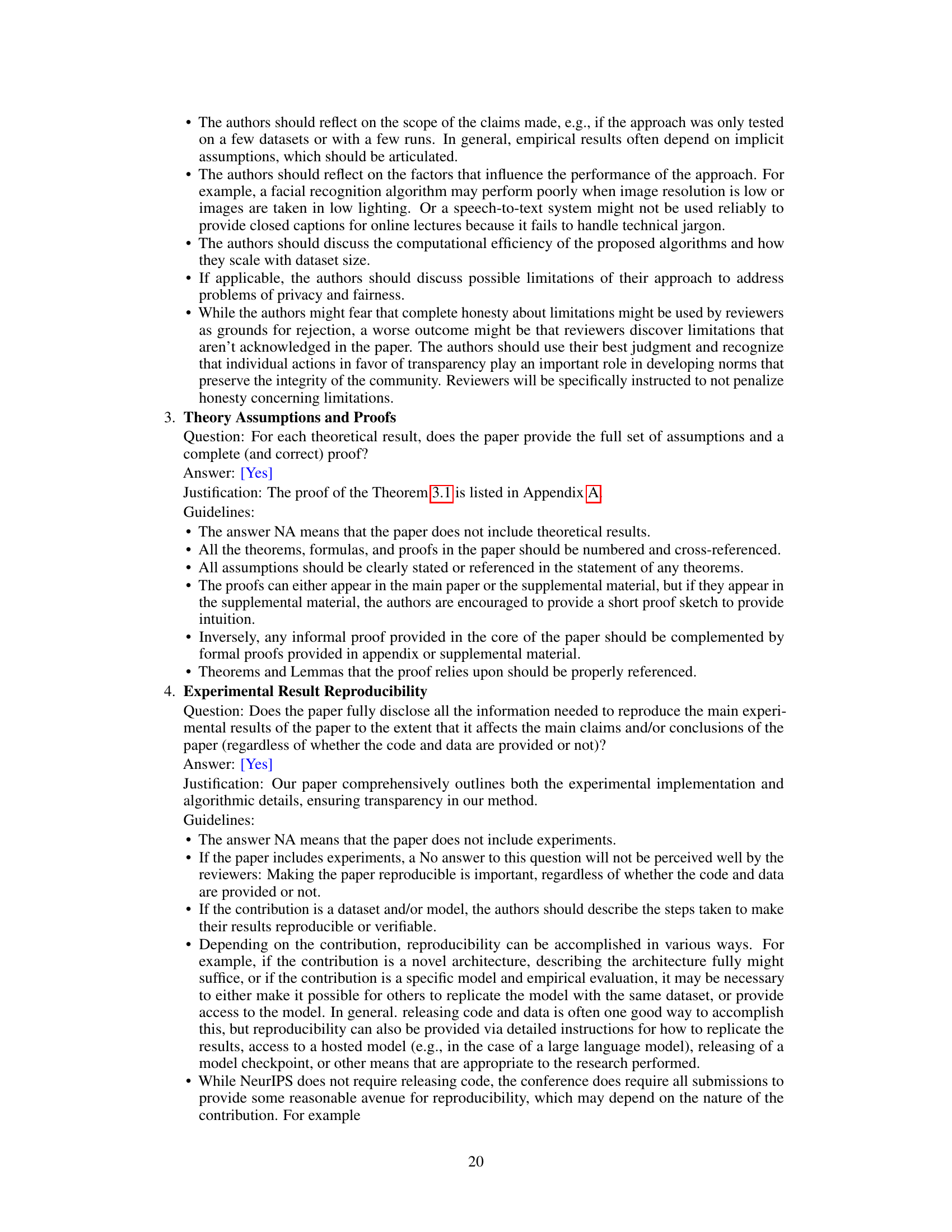

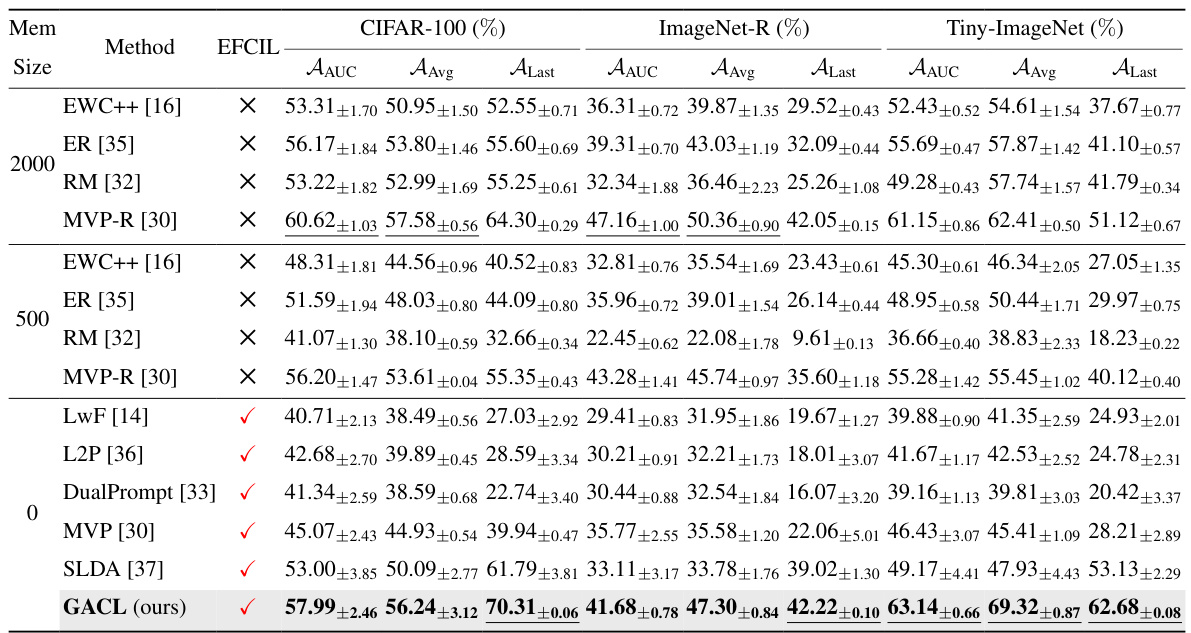

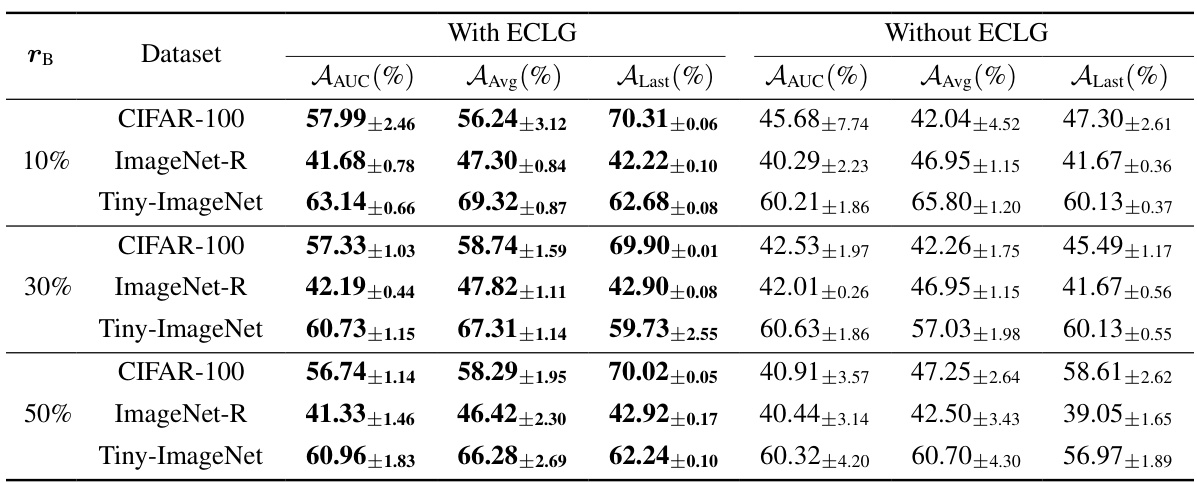

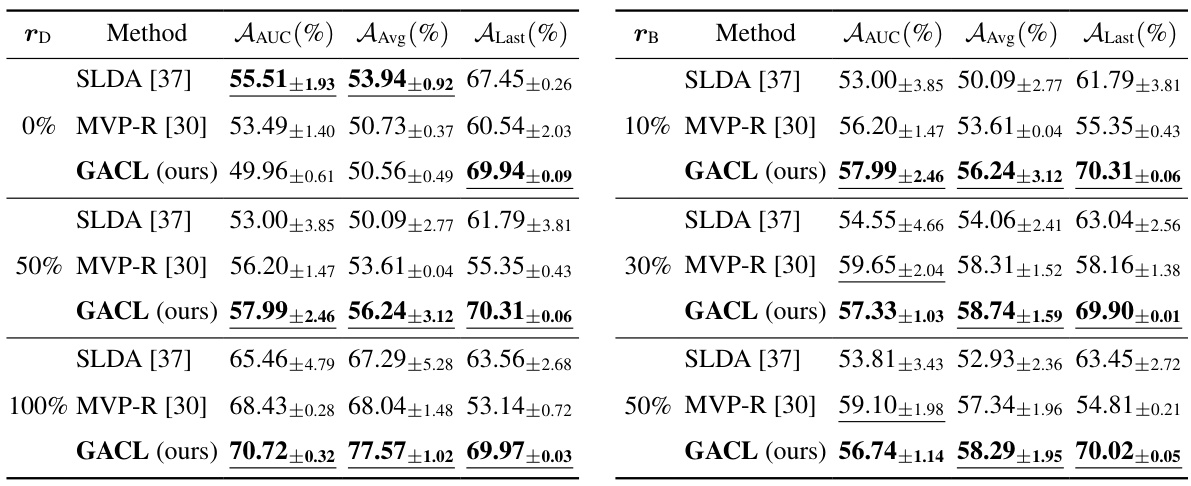

This table compares the performance of the proposed GACL method against other state-of-the-art methods (both exemplar-free and replay-based) under the Si-Blurry setting, a challenging continual learning scenario. The comparison uses three metrics: Average Area Under the Curve (AAUC), Average Accuracy (AAvg), and Last Task Accuracy (ALast). The best performance among exemplar-free continual learning (EFCIL) methods is highlighted in bold, while the overall best performance across all methods and settings is underlined. Results are averaged over five independent runs, with standard errors reported.

In-depth insights#

GCIL Background#

Generalized Class Incremental Learning (GCIL) addresses the limitations of traditional Class Incremental Learning (CIL) by tackling real-world scenarios. Unlike CIL’s assumption of disjoint tasks with fixed sample sizes, GCIL acknowledges the complexity of mixed data categories and imbalanced sample distributions across tasks. This makes GCIL significantly more challenging, requiring robust methods to prevent catastrophic forgetting while handling unknown data distributions. Existing GCIL approaches, often relying on exemplar-based methods or regularization techniques, frequently compromise either performance or data privacy by storing past examples. The central challenge lies in creating exemplar-free methods that effectively handle the uneven distribution of known and unknown classes in incoming data without sacrificing accuracy. The development of GCIL methods has implications for various applications including lifelong machine learning, data privacy, and efficient model training in dynamic environments. Therefore, GCIL presents a rich area of study bridging theory and practice for improving learning systems in real-world settings.

GACL Methodology#

The GACL methodology centers on analytic learning, a gradient-free approach, to address the challenges of Generalized Class Incremental Learning (GCIL). Unlike gradient-based methods prone to catastrophic forgetting, GACL offers a closed-form solution. Weight invariance is a key property, ensuring equivalence between incremental and joint training, crucial for handling uneven data distributions in real-world GCIL scenarios. The method cleverly decomposes incoming data into exposed and unexposed classes, leveraging a buffered embedding extraction mechanism and an exposed class label gain (ECLG) module to update model weights recursively. No exemplars are stored, addressing privacy concerns. The approach’s theoretical foundation is validated through matrix analysis, while empirical results demonstrate consistently superior performance across various datasets.

Empirical Results#

An Empirical Results section in a research paper would typically present quantitative findings that support or refute the study’s hypotheses. A strong section would go beyond simply reporting numbers; it would contextualize the results, discussing their statistical significance and practical implications. For example, it might show how the results compare to prior research, highlighting novel findings or confirming existing knowledge. Visualizations (graphs, charts, tables) are crucial for effective communication of complex datasets, making it easier for the reader to grasp patterns and trends. The discussion should acknowledge limitations of the data or methodology, particularly addressing potential biases and confounding variables that could affect the interpretation of results. A key element is a clear and concise explanation of how the results relate back to the paper’s central research questions or objectives, showing whether the hypothesis is supported or refuted and what the implications of this finding might be for future research or practice. Finally, a good section will highlight the most important results, placing them within a broader theoretical context.

Limitations & Future#

The section discussing limitations and future work in a research paper is crucial for demonstrating a thorough understanding of the study’s scope and potential. A thoughtful analysis would likely address the inherent limitations of the proposed method, such as the reliance on a pre-trained backbone, which restricts adaptability and may limit performance in scenarios where the backbone’s features are not optimally suited to the task. Future research directions could then build upon these findings. This might involve exploring alternative model architectures or strategies to allow for backbone adaptation or fine-tuning during incremental learning, improving the method’s robustness. Another potential limitation might be computational costs and memory usage, especially with larger datasets, therefore future work might focus on optimizing the algorithm for efficiency or exploring techniques to reduce its memory footprint. Addressing the identified limitations and proposing concrete future research directions strengthens the paper’s overall contribution by providing a clear roadmap for future improvements and extensions.

Theoretical Analysis#

A theoretical analysis section in a research paper would typically delve into a rigorous mathematical justification of the proposed method’s claims. It would likely involve formal proofs to establish the validity of core theorems or lemmas underlying the algorithm’s design. This might include demonstrating weight invariance properties, proving the convergence of iterative processes, or establishing bounds on performance metrics. A strong theoretical analysis not only validates the approach but also sheds light on its limitations and potential failure modes. It might explore sufficient conditions for the algorithm’s success, identify specific scenarios where it is expected to perform exceptionally well or poorly, and offer insights into the relationships between different model parameters and performance outcomes. The analysis should be self-contained, clearly defining all variables and assumptions, thereby enabling readers to independently verify the results. Matrix analysis is frequently used in machine learning, particularly when analyzing gradient-based methods or exploring the properties of high-dimensional data. The overall goal is to provide a solid mathematical foundation upon which the experimental results can be interpreted.

More visual insights#

More on figures

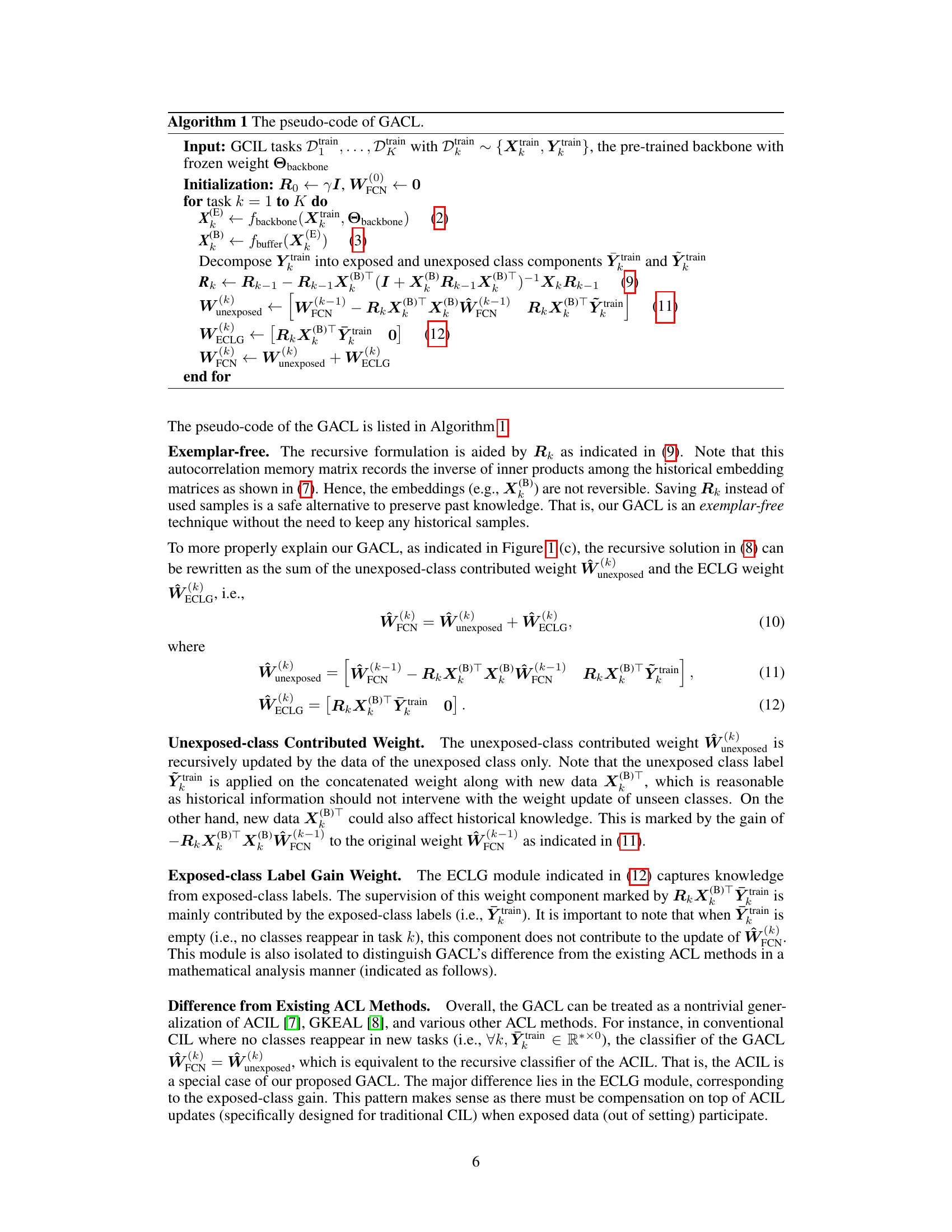

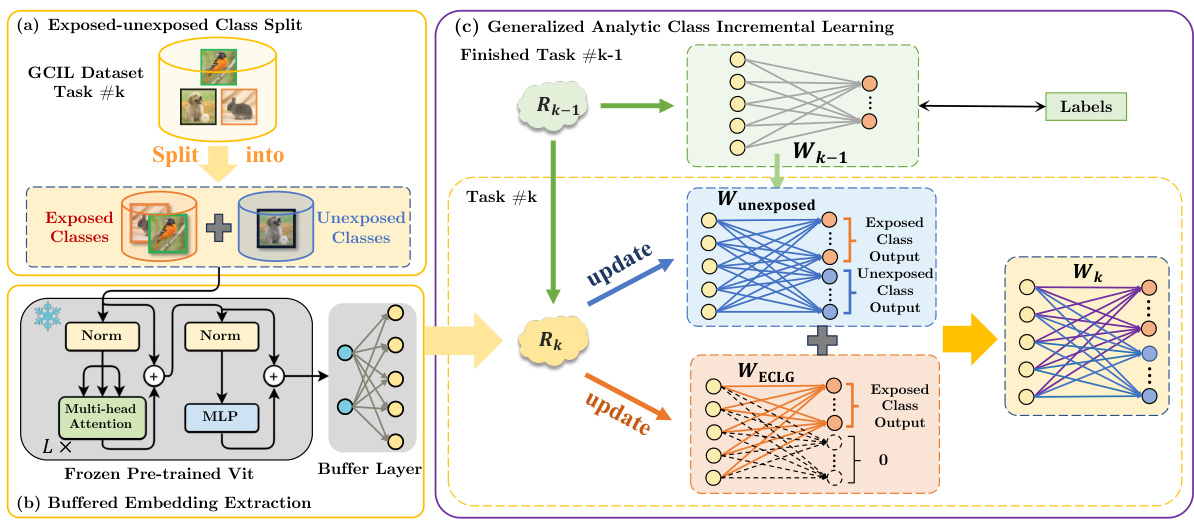

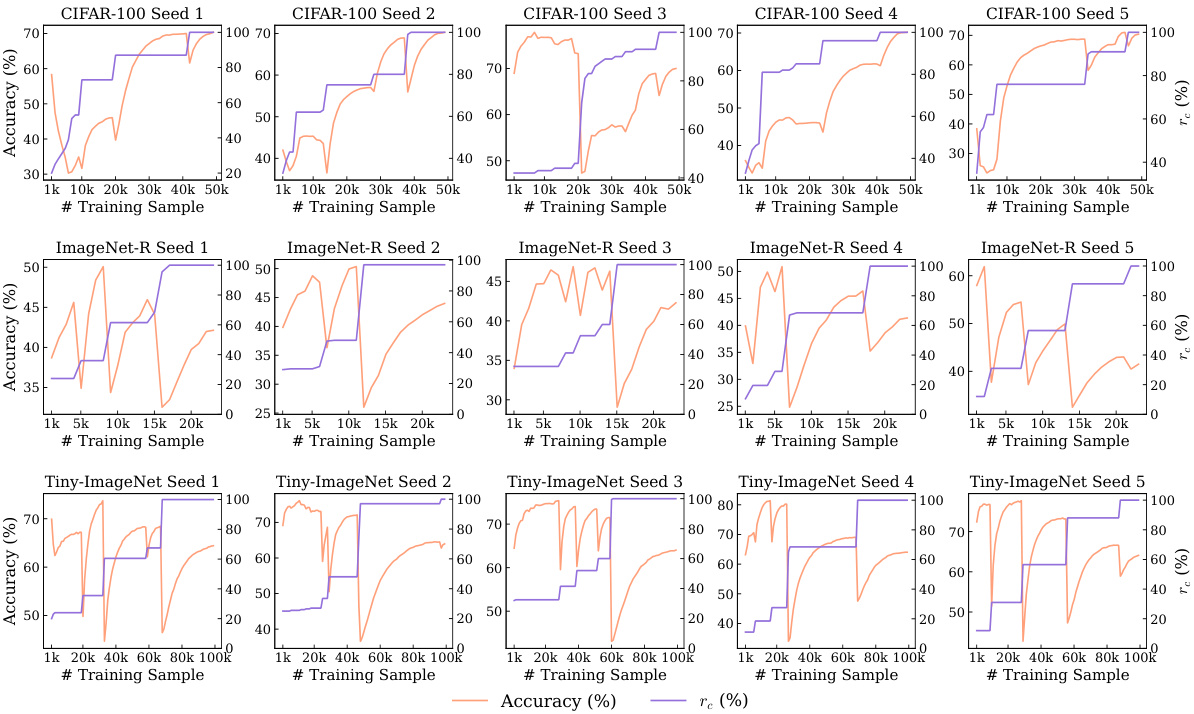

This figure compares the performance of the proposed GACL method against other state-of-the-art EFCIL (exemplar-free class incremental learning) and replay-based methods across three benchmark datasets (CIFAR-100, ImageNet-R, Tiny-ImageNet). The plots show the task-wise accuracy (Ak) for each method over five consecutive tasks (K=5). The top panel displays the results for EFCIL methods, while the bottom panel shows the results for replay-based methods. The figure illustrates the consistent superior performance of GACL across all datasets and task settings compared to existing methods, particularly its ability to maintain high accuracy over multiple tasks (avoiding catastrophic forgetting).

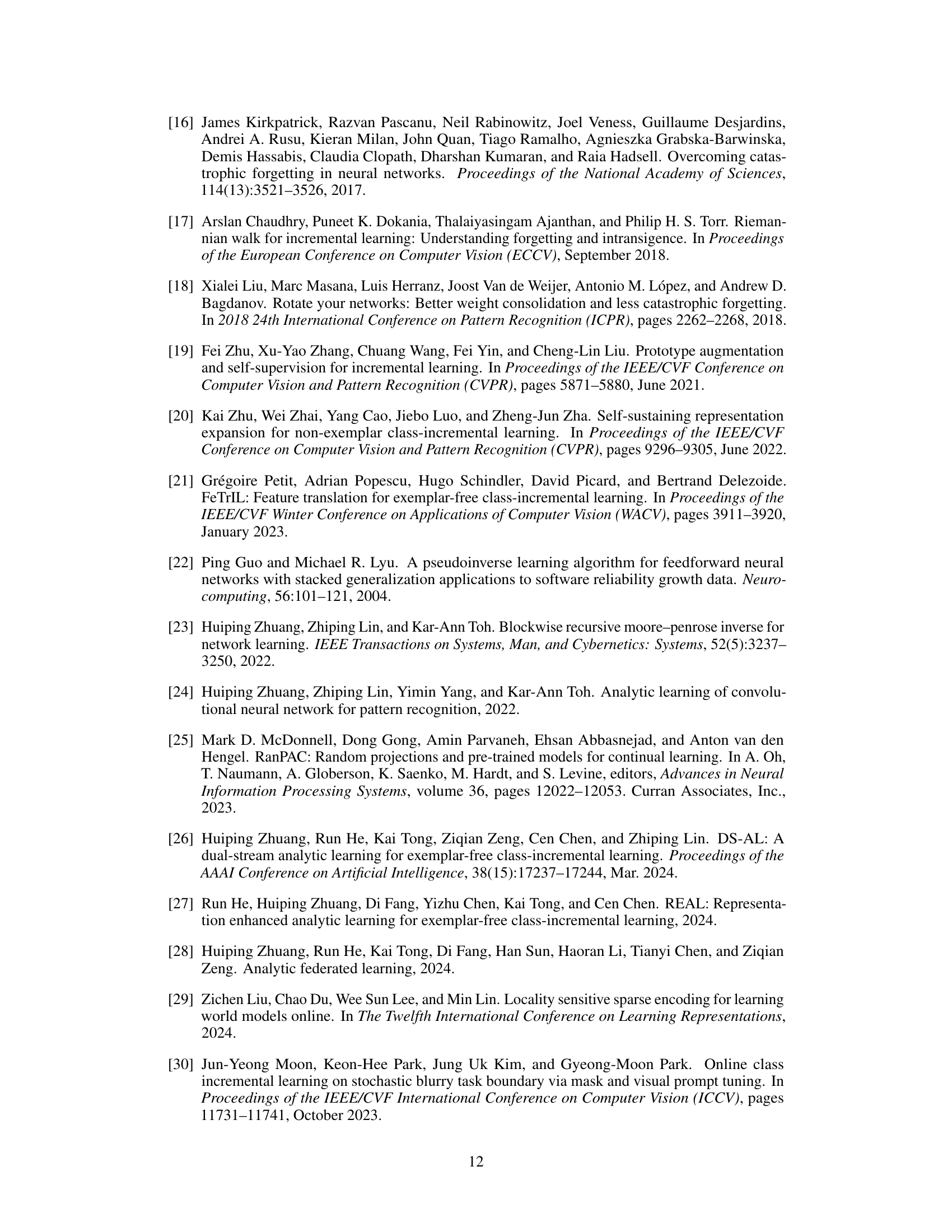

The Si-Blurry setting satisfies all three properties of GCIL mentioned in Appendix B and can be treated as its good realization. As shown in Figure 3, for a K-task learning, the Si-Blurry first randomly partitions all classes into two groups: disjoint classes that cannot overlap between tasks and blurry classes that might reappear. The ratio of partition is controlled by the disjoint class ratio rD, which is defined as the ratio of the number of disjoint classes to the number of all classes. Then disjoint classes and blurry classes are randomly assigned to disjoint tasks (TD) and blurry tasks (TB) respectively. Next, each blurry task further conducts the blurry sample division by randomly extracting part of samples to assign to other blurry tasks based on blurry sample ratio rβ, which is defined as the ratio of the extracted sample within samples in all blurry tasks. Finally, each Si-Blurry task TB+D with a stochastic blurry task boundary consists of a disjoint and blurry task. We adopt Si-Blurry with different combinations of rD and rβ for reliable empirical validations.

This figure provides a high-level overview of the proposed Generalized Analytic Continual Learning (GACL) method. It shows the three main components: (a) the splitting of incoming data into exposed and unexposed classes, (b) feature extraction using a pre-trained Vision Transformer (ViT) and a buffer layer, and (c) the recursive weight update mechanism that leverages exposed class label gain (ECLG) and autocorrelation memory.

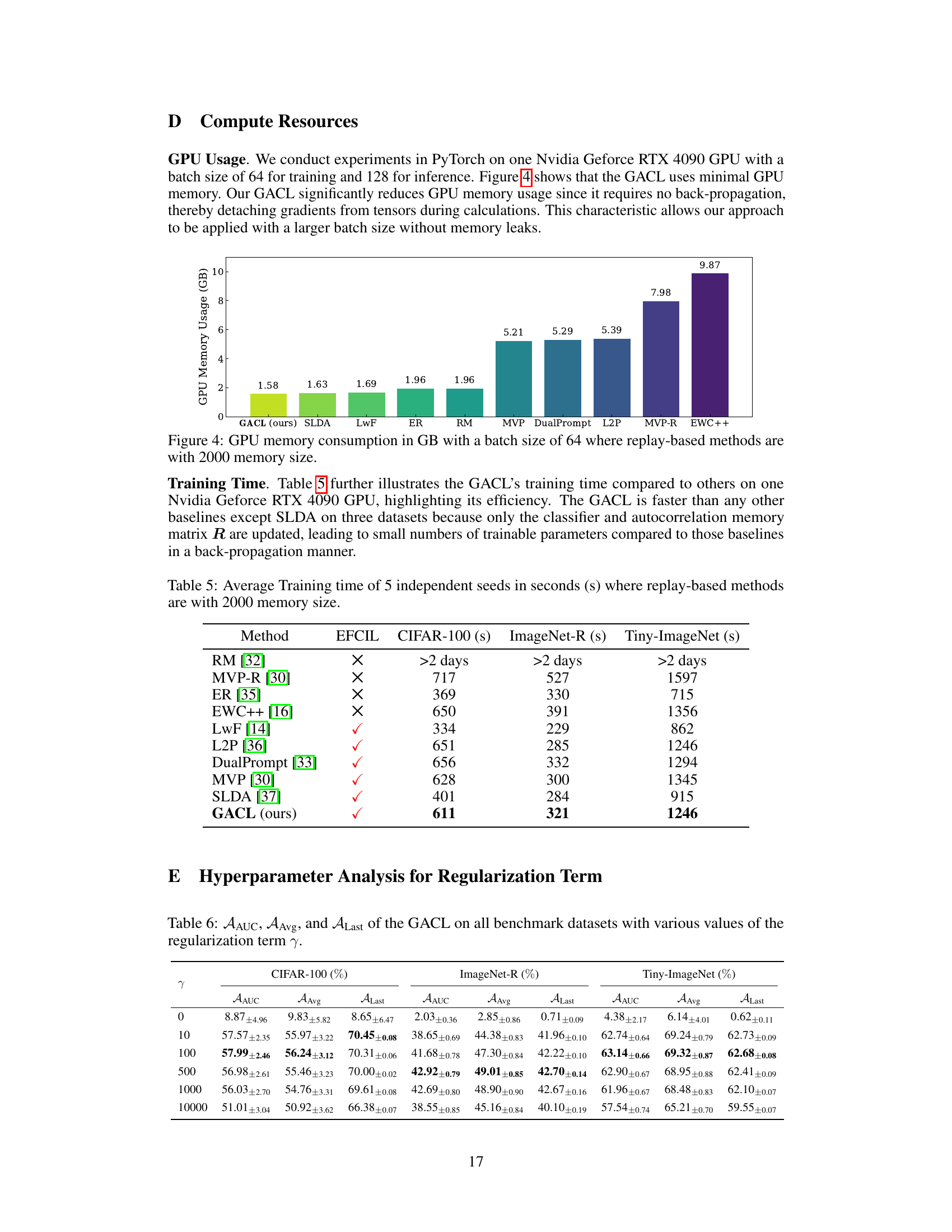

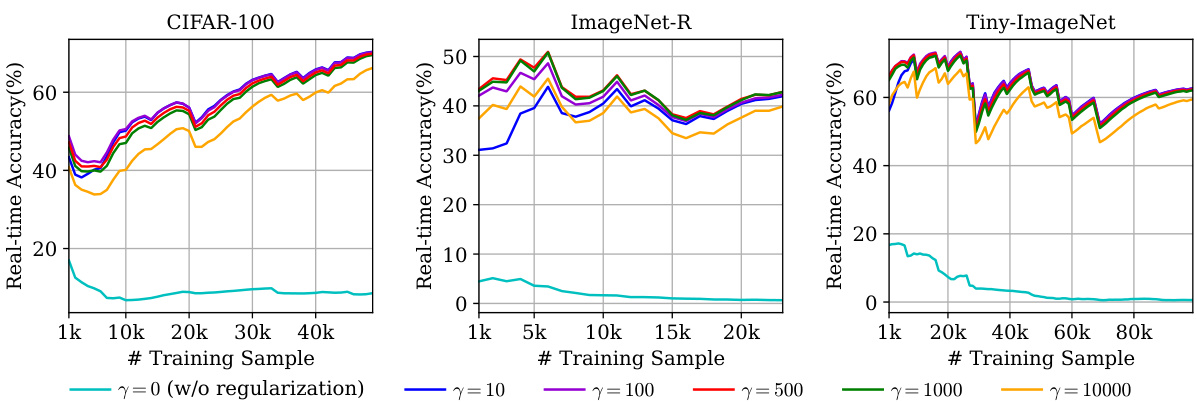

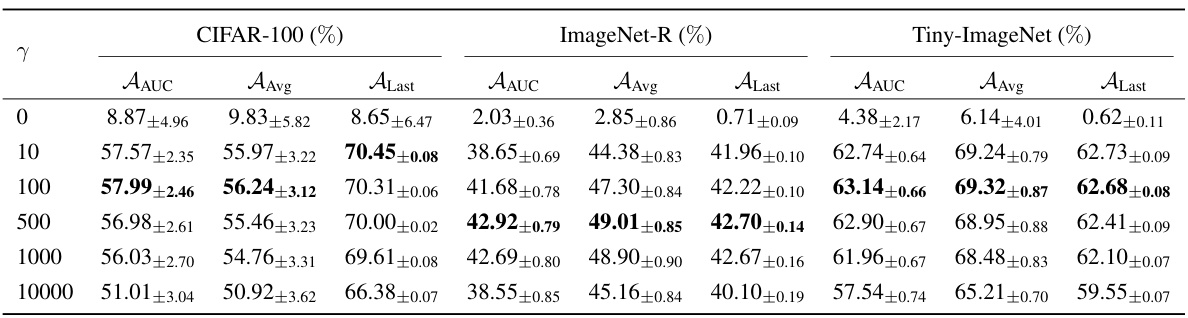

The figure shows the real-time accuracy of the proposed GACL on CIFAR-100, ImageNet-R, and Tiny-ImageNet datasets with different regularization term (γ) values. The x-axis represents the number of training samples, and the y-axis represents the real-time accuracy. Different colored lines represent different γ values. The figure demonstrates the robustness of the GACL across different datasets and regularization strengths, showing generally stable performance across a wide range of γ values, with some minor variations depending on the dataset.

This figure provides a high-level overview of the proposed Generalized Analytic Continual Learning (GACL) method. It’s broken down into three parts: (a) Exposed-Unexposed Class Split: Shows how the input data for each task is divided into exposed (previously seen) and unexposed (new) classes. (b) Buffered Embedding Extraction: Illustrates how a pre-trained Vision Transformer (ViT) and a buffer layer extract features from the input images. (c) Generalized Analytic Class Incremental Learning: This depicts the core GACL algorithm, highlighting the recursive update process using exposed and unexposed class information and an autocorrelation memory matrix. The key components are the weights updated for unexposed classes and an Exposed Class Label Gain (ECLG) module.

More on tables

This table compares the performance of the proposed GACL method against other state-of-the-art methods (both exemplar-free and replay-based) for generalized class incremental learning under the Si-Blurry setting. The comparison uses three metrics: Average Area Under the Curve (AAUC), Average Accuracy (AAvg), and Last Task Accuracy (ALast). The best performance among exemplar-free continual learning methods is highlighted in bold, and the overall best performance across all methods is underlined. Results are averaged over five independent runs, with standard errors reported.

This table compares the performance of the proposed GACL method against other state-of-the-art methods (both EFCIL and replay-based methods) across three datasets (CIFAR-100, ImageNet-R, and Tiny-ImageNet) under the Si-Blurry setting. The comparison is done using three metrics: Average Area Under the Curve (AAUC), Average Accuracy (AAvg), and Last-task Accuracy (ALast). The best EFCIL results and the best overall results are highlighted in bold and underlined respectively. Each result is an average of 5 independent runs, showing mean and standard error.

This table compares the performance of the proposed GACL method against other state-of-the-art methods (both exemplar-free and replay-based) on three benchmark datasets (CIFAR-100, ImageNet-R, and Tiny-ImageNet) under the Si-Blurry setting of Generalized Class Incremental Learning (GCIL). The comparison is based on three metrics: Average Area Under the Curve (AAUC), Average Accuracy (AAvg), and Last-task Accuracy (ALast). The best performance among exemplar-free methods (EFCIL) is shown in bold, and the overall best performance across all methods is underlined.

This table compares the performance of the proposed GACL method against other state-of-the-art methods (both exemplar-free and replay-based) across three benchmark datasets (CIFAR-100, ImageNet-R, and Tiny-ImageNet) under the Si-Blurry setting. The comparison uses three metrics: Average Area Under the Curve (AAUC), Average Accuracy (AAvg), and Last Task Accuracy (ALast). The best results for exemplar-free continual learning (EFCIL) methods and overall best results are highlighted.

Full paper#