↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on uncertainty quantification in deep learning. It challenges the reliability of a popular method (evidential deep learning), reveals its limitations, and proposes improvements. This directly addresses a significant gap in the field and opens new avenues for more reliable uncertainty estimation techniques.

Visual Insights#

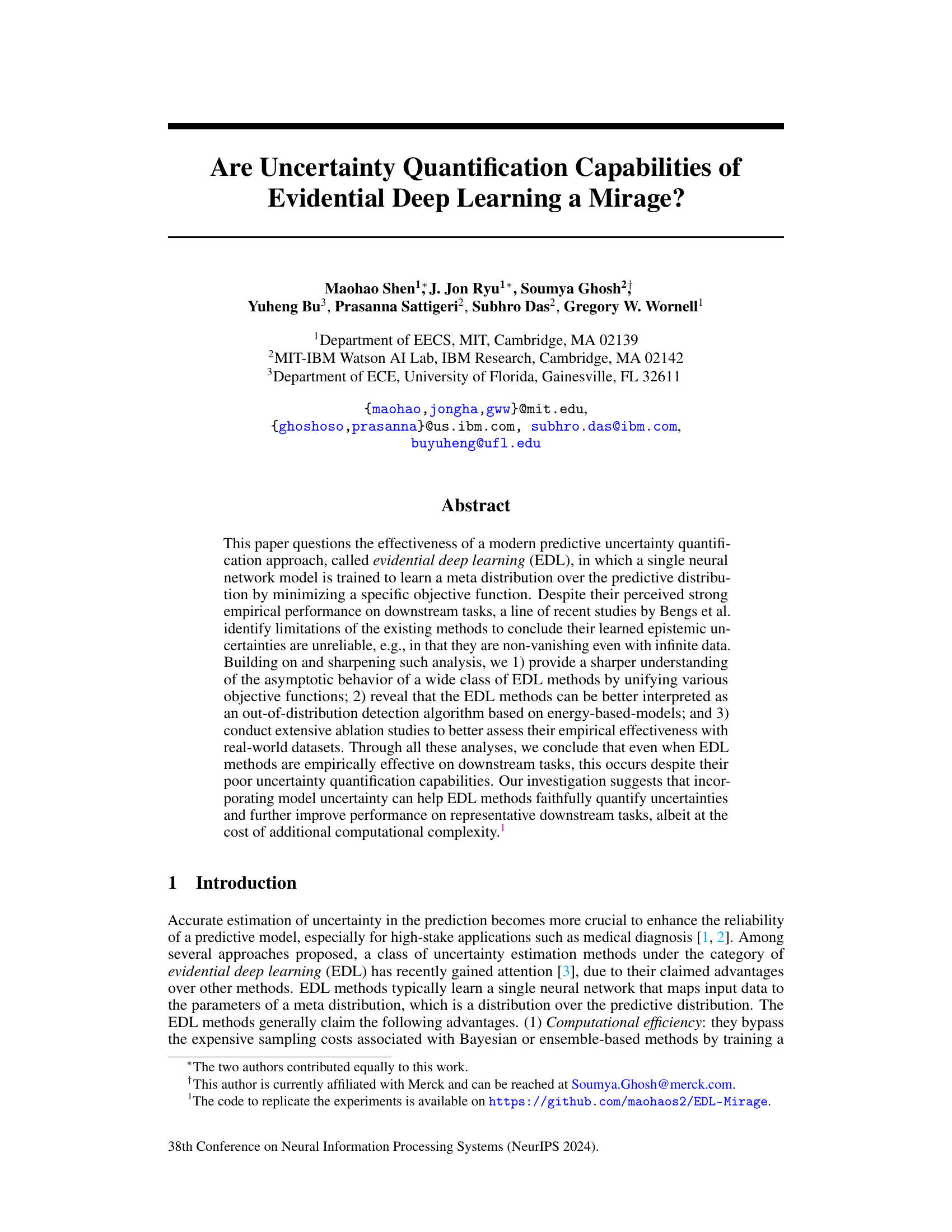

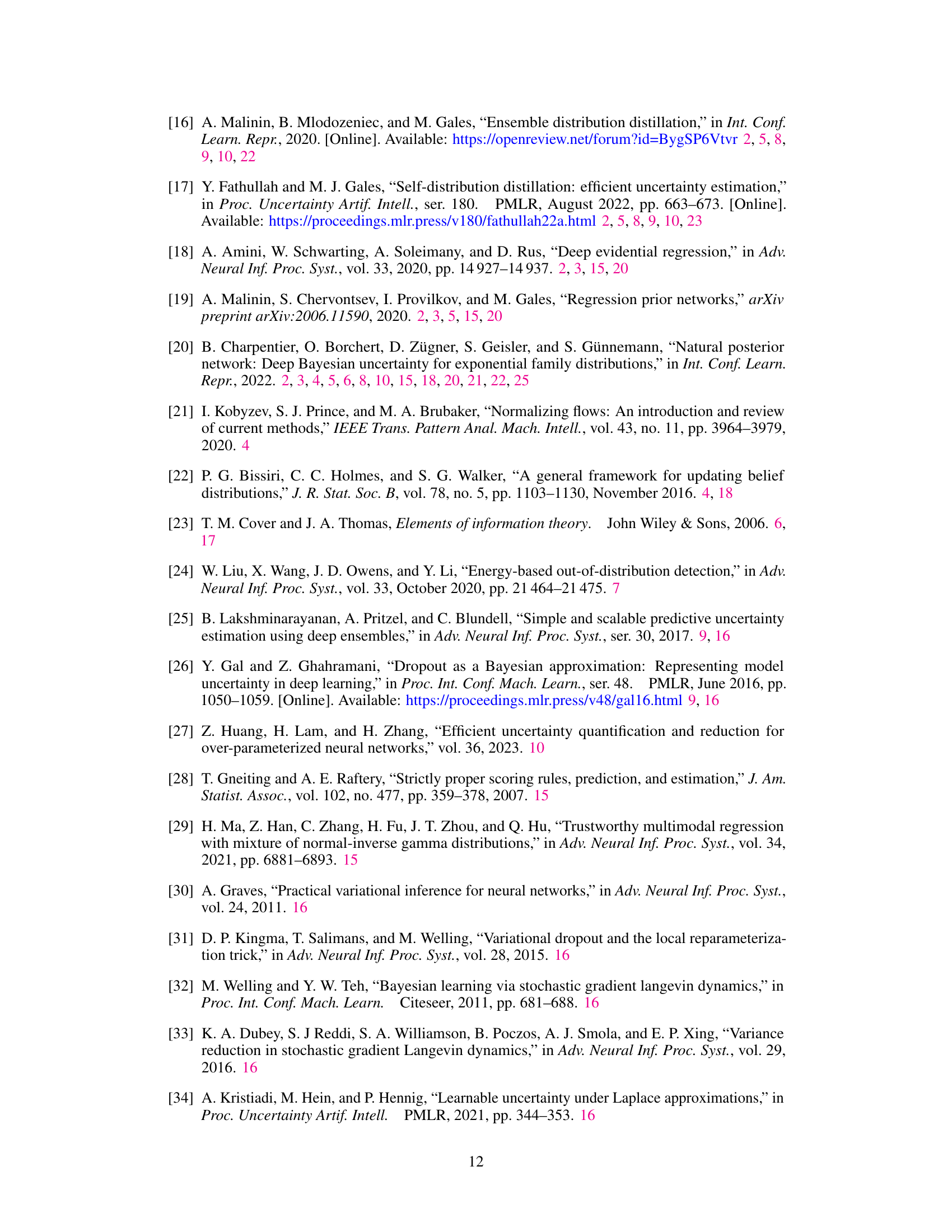

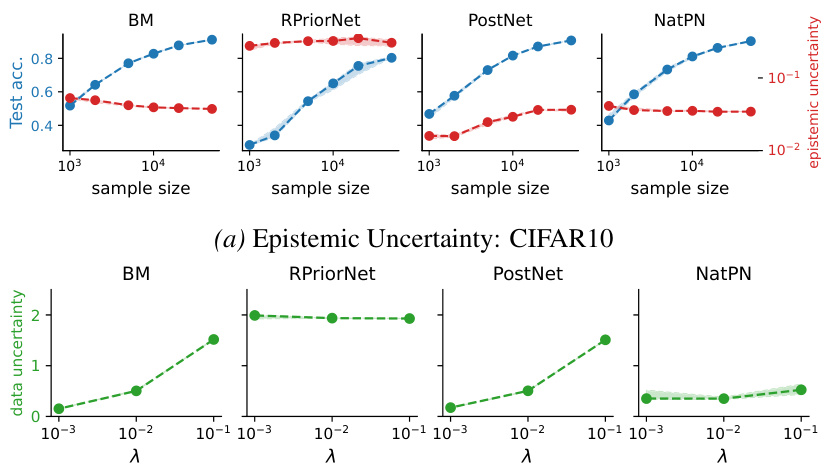

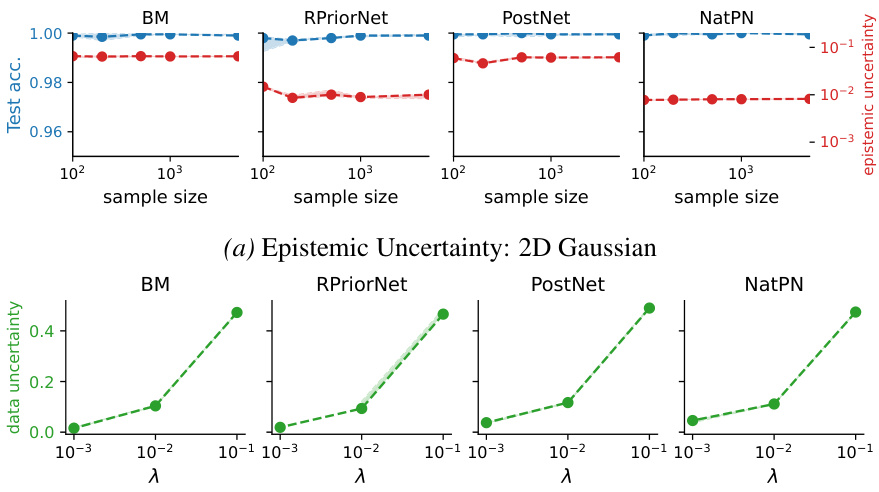

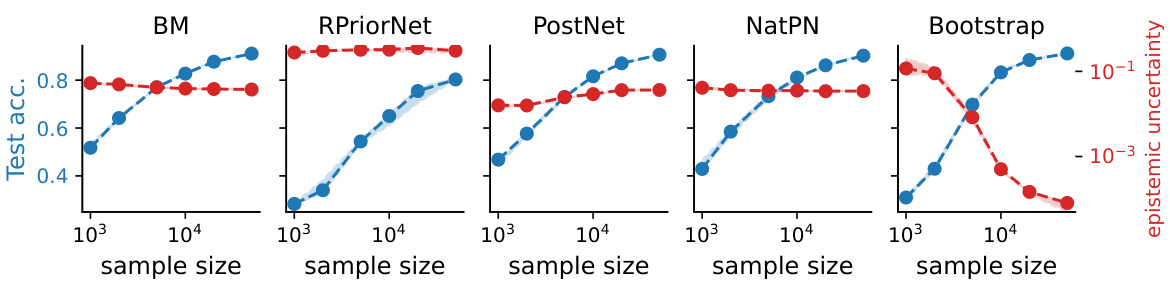

This figure shows the behavior of epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty learned by four different EDL methods (BM, RPriorNet, PostNet, NatPN) on the CIFAR10 dataset. The left side (a) illustrates the epistemic uncertainty which, contrary to its definition, does not vanish as the sample size increases. The right side (b) shows the aleatoric uncertainty, which unexpectedly changes with hyperparameter λ instead of remaining constant.

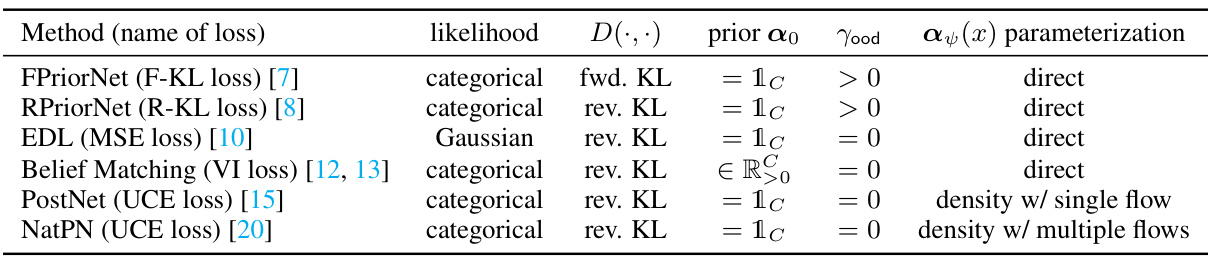

This table presents a new taxonomy for classification-based evidential deep learning (EDL) methods. It categorizes EDL methods based on two key distinguishing features: (1) the parametric form of the meta distribution (direct vs. density parameterization) and (2) the learning criteria (objective function used during training). The table lists several representative EDL methods and specifies their likelihood model, divergence function (forward KL or reverse KL), prior parameters (α0), OOD regularization parameter (γood), and parameterization type. The unifying objective function L(ψ) from equation (6) in the paper subsumes the various loss functions used by these methods.

In-depth insights#

EDL’s Mirage#

The paper challenges the reliability of Evidential Deep Learning (EDL) for uncertainty quantification. EDL methods, while empirically successful on some tasks, demonstrate a flawed understanding of uncertainty. The authors reveal that EDL models learn spurious epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties, failing to exhibit the expected behavior of vanishing epistemic uncertainty with increasing data. They provide a unified theoretical analysis of EDL methods, showing that even under optimal conditions, the learned uncertainty doesn’t accurately reflect genuine model uncertainty. Instead of quantifying uncertainty, EDL methods are better interpreted as energy-based out-of-distribution (OOD) detectors. The authors propose a modified approach, incorporating model uncertainty via bootstrapping, to more faithfully capture uncertainties, highlighting the critical need to address model uncertainty within EDL frameworks for accurate uncertainty quantification.

EDL Theory#

Evidential Deep Learning (EDL) theory centers around using neural networks to learn meta-distributions, which model uncertainty in predictions. Key theoretical challenges revolve around the reliability of learned uncertainties, particularly the non-vanishing nature of epistemic uncertainty even with abundant data. EDL methods are often better viewed as out-of-distribution detectors that implicitly model uncertainties rather than providing faithful uncertainty quantification. Unifying various objective functions within a common framework reveals that these methods are often implicitly fitting to specific target distributions, rather than learning inherently meaningful uncertainties. Incorporating model uncertainty is highlighted as crucial for faithfully quantifying uncertainty, contrasting with the typical EDL approach of minimizing an objective function for a single, fixed model.

EDL Experiments#

A hypothetical section on ‘EDL Experiments’ in a research paper would warrant a thorough exploration of the methodology. It should detail the specific evidential deep learning (EDL) models used, clearly outlining their architectures and hyperparameters. The selection of datasets is crucial; the description should specify whether these were synthetic, real-world, or a combination. Crucially, the evaluation metrics employed should be justified and their appropriateness discussed in relation to uncertainty quantification. Quantitative results, reported with standard error bars or other significance measures, are paramount, reflecting the statistical robustness of any claims. The experimental setup needs comprehensive details to enable replication, including hardware, software, and training procedures. Ablation studies would be critical for isolating the contribution of different EDL components, verifying their effectiveness, and revealing potential weaknesses. Finally, a discussion comparing EDL performance with established baseline methods offers crucial context and highlights the relative strengths and limitations of the approach.

EDL Limitations#

Evidential Deep Learning (EDL) methods, while empirically successful in some uncertainty quantification tasks, suffer from significant limitations. The core issue is the absence of explicit model uncertainty, treating the model as a single point estimate rather than a distribution. This leads to spurious epistemic uncertainty, where learned uncertainty persists even with infinite data, contradicting its fundamental definition. Additionally, EDL’s aleatoric uncertainty estimates are model-dependent, violating the requirement of invariance to data size. These flaws indicate that EDL methods are fundamentally more akin to out-of-distribution (OOD) detectors than robust uncertainty quantifiers. A crucial improvement involves incorporating model uncertainty, which accurately reflects the epistemic uncertainty through the distribution of models, but this comes at the cost of increased computational complexity.

Future of EDL#

The future of evidential deep learning (EDL) hinges on addressing its current limitations. Improving uncertainty quantification is paramount, perhaps by explicitly incorporating model uncertainty through methods like bootstrapping or Bayesian approaches, thereby moving beyond the current reliance on single-model estimations. Further theoretical investigation is needed to solidify the foundations of EDL, clarifying the asymptotic behavior of its methods and resolving ambiguities in objective functions. Bridging the gap between theoretical understanding and empirical success is crucial. While EDL exhibits promising empirical performance in tasks like out-of-distribution detection, a more complete understanding of why this occurs despite theoretical shortcomings is necessary. Finally, exploring novel architectural designs and loss functions that explicitly target robust uncertainty estimation while maintaining computational efficiency will determine EDL’s true potential.

More visual insights#

More on figures

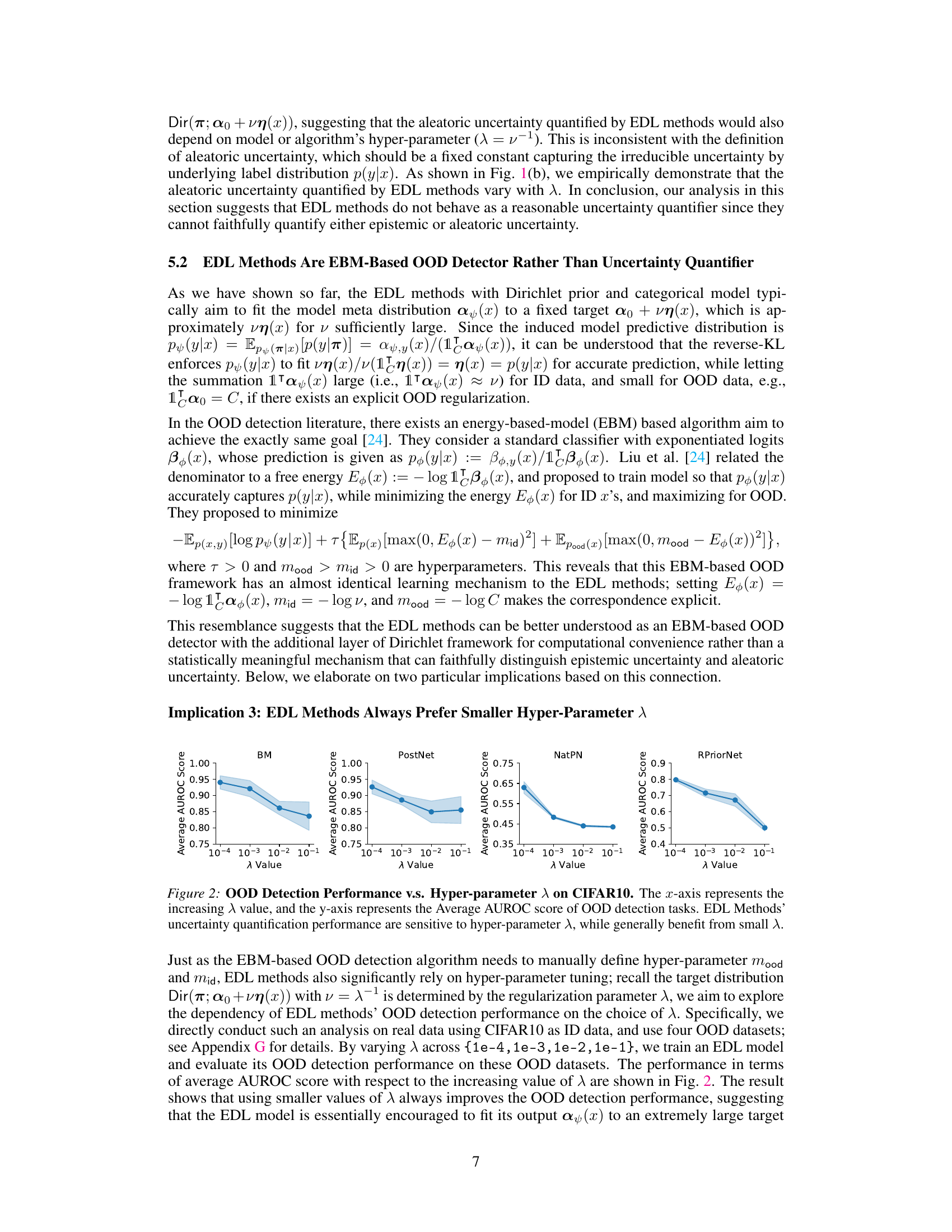

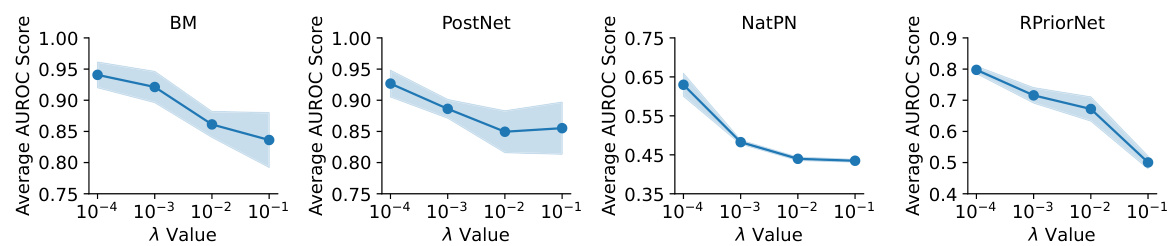

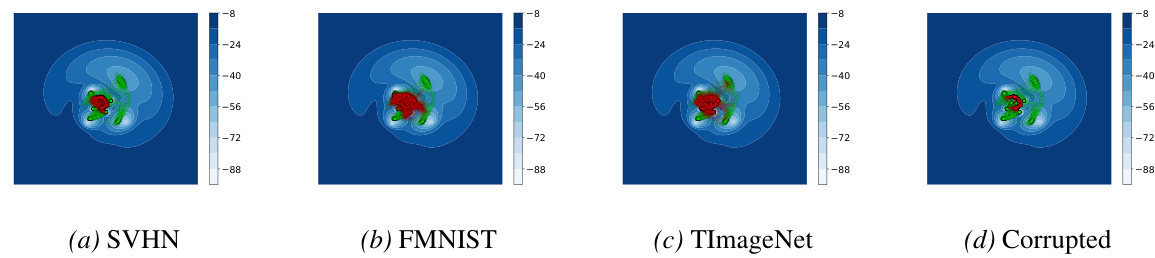

This figure shows the impact of the hyperparameter λ on the performance of different EDL methods in out-of-distribution (OOD) detection tasks using CIFAR-10 as the in-distribution dataset. The average AUROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve), a common metric for evaluating OOD detection, is plotted against different values of λ. The shaded area represents the standard deviation across multiple runs. The results indicate that the performance of EDL methods in OOD detection is sensitive to the choice of λ, with generally better performance observed for smaller values of λ.

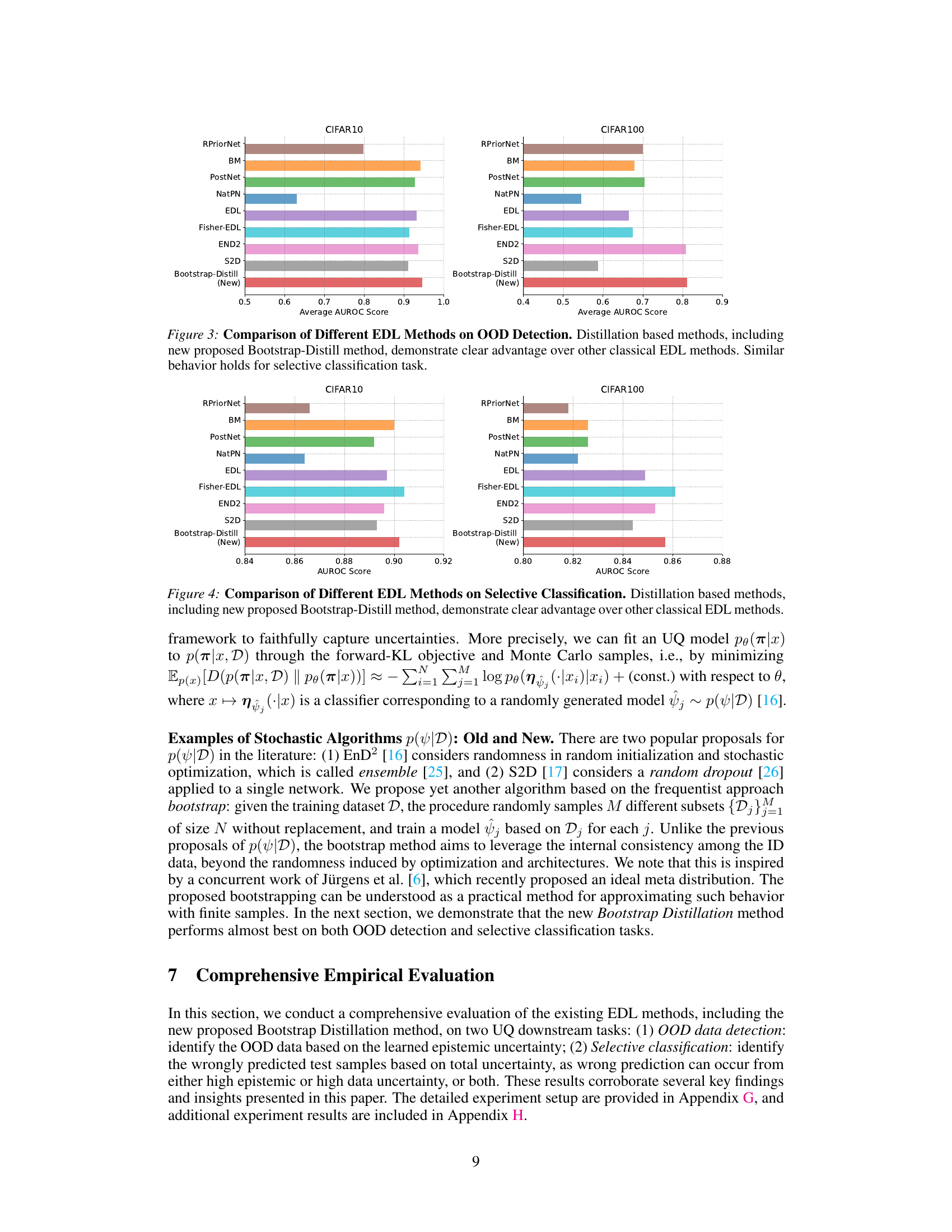

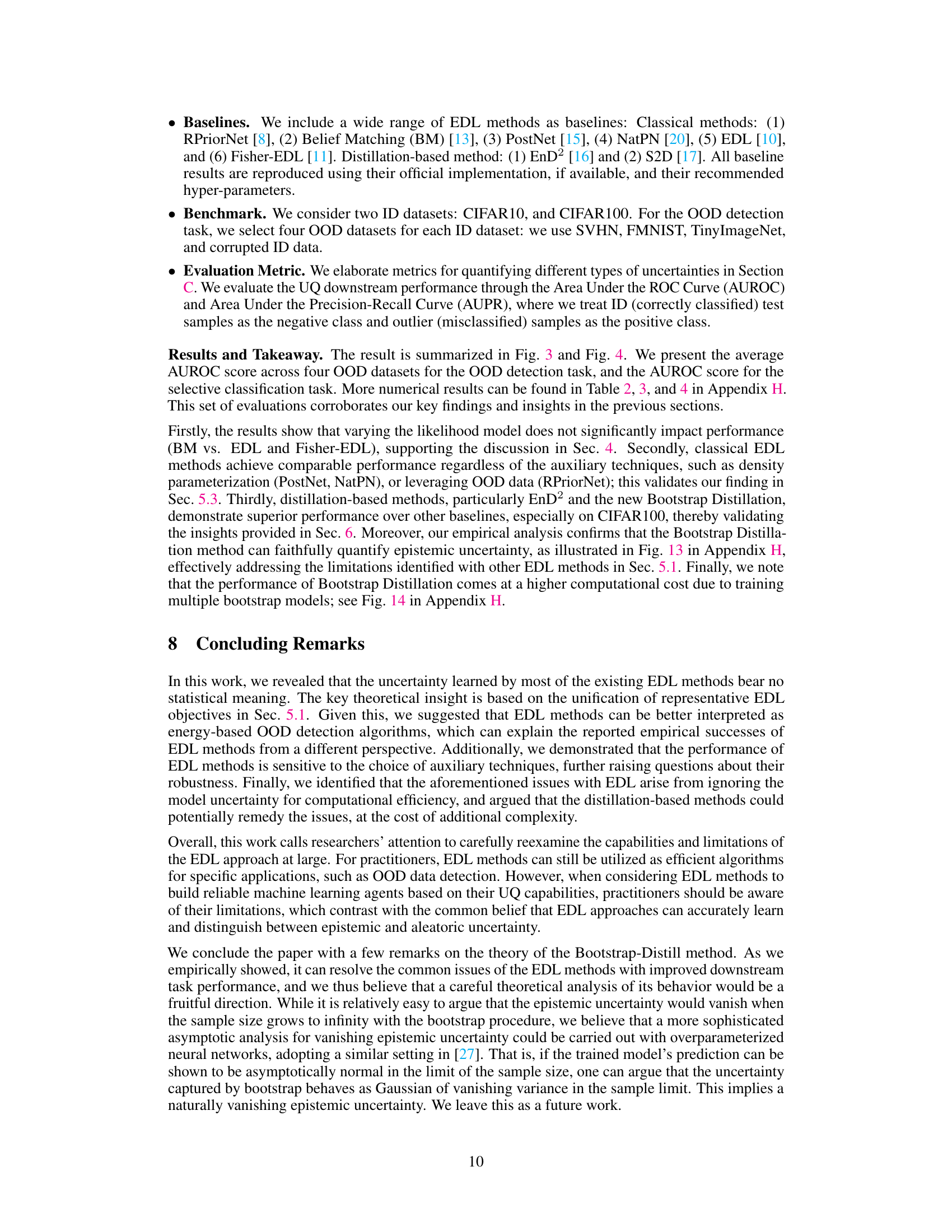

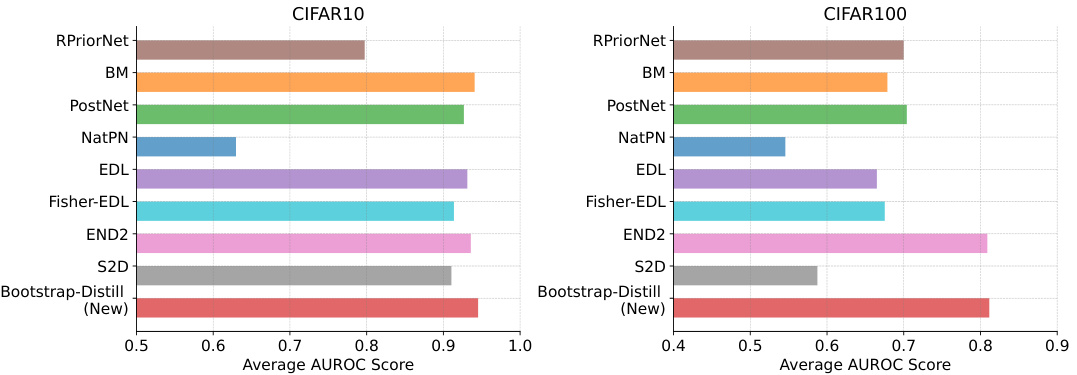

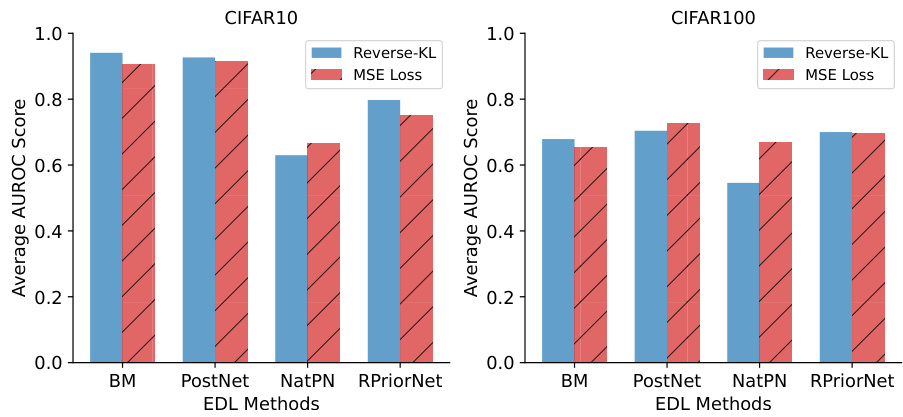

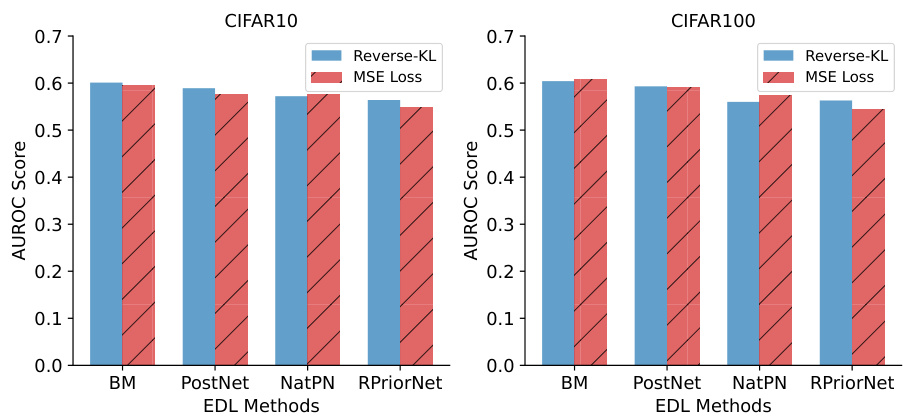

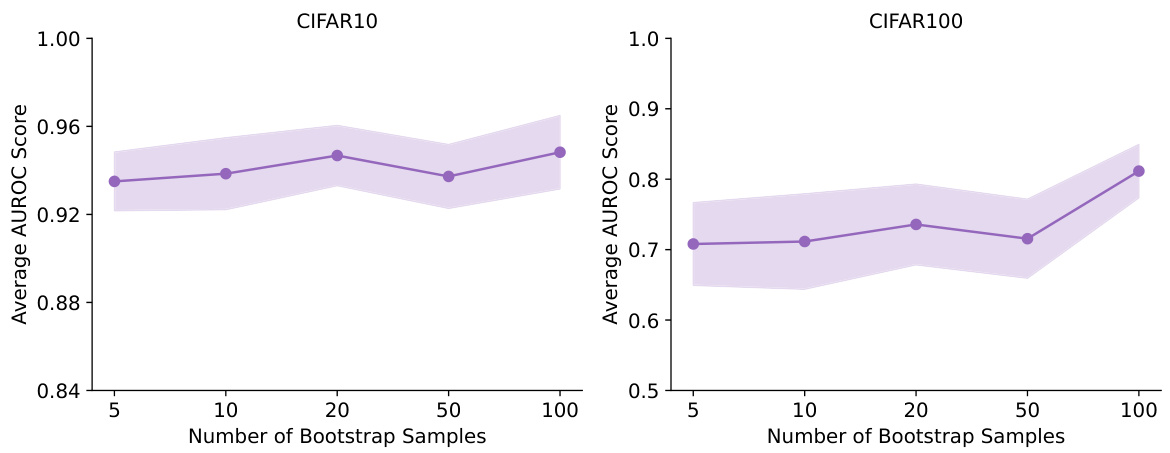

This figure compares the performance of various EDL methods on out-of-distribution (OOD) detection. The x-axis represents the different EDL methods. The left bar graph shows AUROC scores for CIFAR-10, and the right bar graph shows AUROC scores for CIFAR-100. The results indicate that distillation-based methods, particularly the new Bootstrap-Distill method, significantly outperform other EDL approaches in OOD detection. The improved performance is consistent across both CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets.

This figure shows the behavior of epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties learned by four different EDL methods (BM, RPriorNet, PostNet, NatPN) on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The left panel (a) demonstrates that epistemic uncertainty (the uncertainty due to the model’s knowledge) does not decrease even with an increasing number of training samples, which is unexpected. The right panel (b) illustrates that the aleatoric uncertainty (the uncertainty inherent in the data) depends on a hyperparameter λ, contradicting the fundamental definition of aleatoric uncertainty as being data-dependent, not model-dependent.

This figure shows the behavior of epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties learned by four representative EDL methods (BM, RPriorNet, PostNet, and NatPN) on CIFAR-10 dataset. The left panel (a) demonstrates that epistemic uncertainty, as quantified by mutual information, does not decrease and vanish with increasing sample sizes. This is contrary to the expected behavior, where uncertainty should decrease with more data. The right panel (b) illustrates that the aleatoric uncertainty, quantified by the expected Shannon entropy, is not a constant but depends on the hyperparameter lambda (λ). This is not in line with the definition of aleatoric uncertainty which should be constant and independent of model parameters.

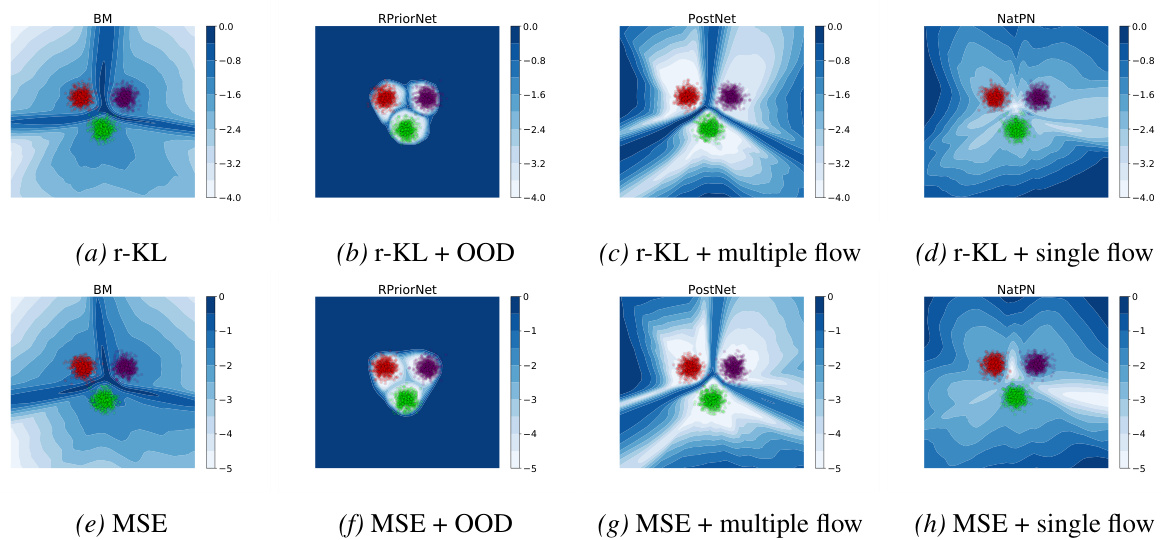

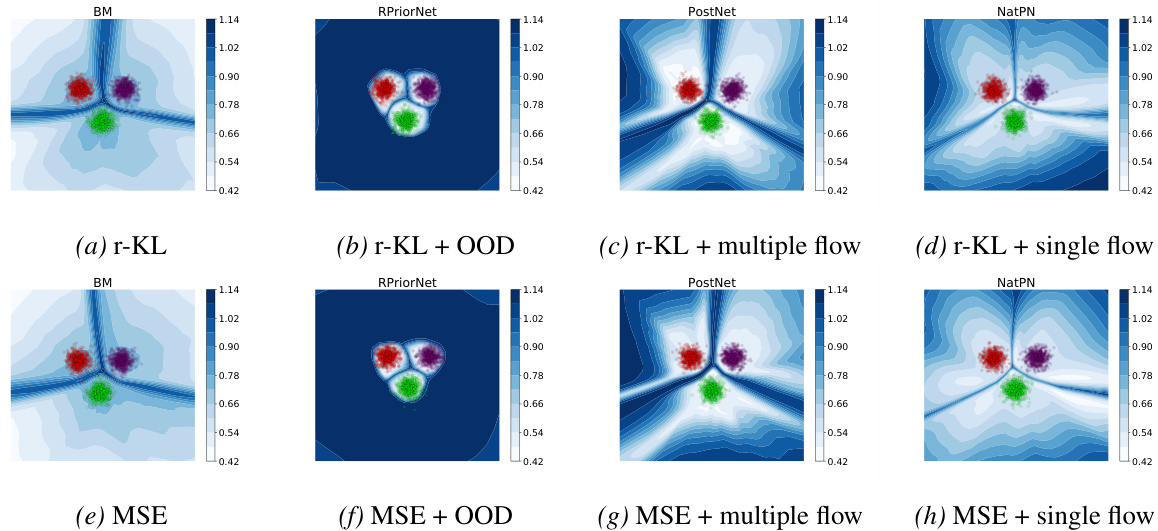

This figure shows an ablation study on the effect of different training objectives and auxiliary techniques on the ability of EDL methods to quantify epistemic uncertainty. The results indicate that the choice of training objective (reverse KL vs. MSE) has little impact, whereas the use of auxiliary techniques like density estimation and OOD data during training significantly affects performance. Without these techniques, the basic EDL method struggles to distinguish between in-distribution and out-of-distribution data.

This figure shows that Evidential Deep Learning (EDL) methods fail to accurately capture epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty. The left panel demonstrates that epistemic uncertainty (which should decrease with more data) remains high even with a large number of samples. The right panel shows that aleatoric uncertainty (which should be constant) changes with a hyperparameter (λ). This indicates EDL methods do not reliably represent uncertainty.

This figure displays the behavior of epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty learned by four representative EDL methods (BM, RPriorNet, PostNet, NatPN) on the CIFAR10 dataset. Subfigure (a) shows that epistemic uncertainty, which should decrease with more data, remains constant, even with an increasing number of samples. Subfigure (b) reveals that aleatoric uncertainty, which should be constant, is dependent on the hyperparameter λ. This inconsistent behavior contradicts the fundamental definitions of both types of uncertainty, suggesting a flaw in how these EDL methods quantify uncertainty.

This figure shows the behavior of epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty learned by four different EDL methods (BM, RPriorNet, PostNet, NatPN) on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The left panel (a) demonstrates that epistemic uncertainty, as measured by mutual information, does not decrease with increasing sample size, contradicting the theoretical definition of epistemic uncertainty. The right panel (b) shows that aleatoric uncertainty varies with the hyperparameter λ, again contradicting the theoretical definition which posits it should be constant. These findings suggest that the EDL methods do not reliably quantify uncertainties.

This figure shows the behavior of epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty learned by different Evidential Deep Learning (EDL) methods on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The left subfigure (a) demonstrates that epistemic uncertainty, as measured by mutual information, does not decrease and vanish with increasing sample size as it theoretically should, indicating a spurious learning effect. The right subfigure (b) illustrates that the aleatoric uncertainty, as quantified by the expected entropy of predictive distribution, varies with the hyperparameter λ, contradicting the definition of aleatoric uncertainty as a fixed quantity inherent to the data.

This figure shows the behavior of epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty learned by four representative EDL methods (BM, RPriorNet, PostNet, NatPN) on CIFAR10 dataset. The left panel (a) demonstrates that epistemic uncertainty, as measured by mutual information, remains almost constant regardless of the increasing sample size and test accuracy, contradicting the expectation that epistemic uncertainty should decrease and vanish with more data. The right panel (b) illustrates that aleatoric uncertainty, represented by the expected Shannon entropy of the predictive distribution, varies with the hyperparameter λ instead of being a constant, contrary to the fundamental definition of aleatoric uncertainty. This suggests EDL methods fail to accurately quantify these types of uncertainty.

This figure shows the behavior of epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties learned by four representative EDL methods (BM, RPriorNet, PostNet, NatPN) on the CIFAR10 dataset. The left-hand side (a) demonstrates that the epistemic uncertainty, which should decrease and vanish with increasing data, remains largely constant for ID data across different sample sizes. The right-hand side (b) demonstrates that the aleatoric uncertainty depends on the hyperparameter λ instead of being constant, contradicting the definition of aleatoric uncertainty. These findings challenge the reliability of uncertainty quantification using the existing EDL methods.

This figure shows the behavior of epistemic and aleatoric uncertainty learned by different EDL methods (BM, RPriorNet, PostNet, NatPN) on CIFAR-10 dataset. Subfigure (a) demonstrates that epistemic uncertainty, as quantified by the EDL methods, does not vanish even with an increasing number of training samples, which contradicts the theoretical definition of epistemic uncertainty. Subfigure (b) shows that the EDL methods do not learn a constant aleatoric uncertainty, but rather learn an uncertainty dependent on the hyperparameter λ, a finding that contradicts the theoretical definition of aleatoric uncertainty. This suggests that the uncertainty estimations produced by the EDL methods are unreliable.

This figure demonstrates the behavior of epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties learned by four representative EDL methods (BM, RPriorNet, PostNet, and NatPN) on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The left panel (a) shows that epistemic uncertainty, contrary to its definition, does not vanish as the number of training samples increases. The right panel (b) shows that aleatoric uncertainty depends on the hyperparameter λ, which is inconsistent with the definition of aleatoric uncertainty as independent of the model.

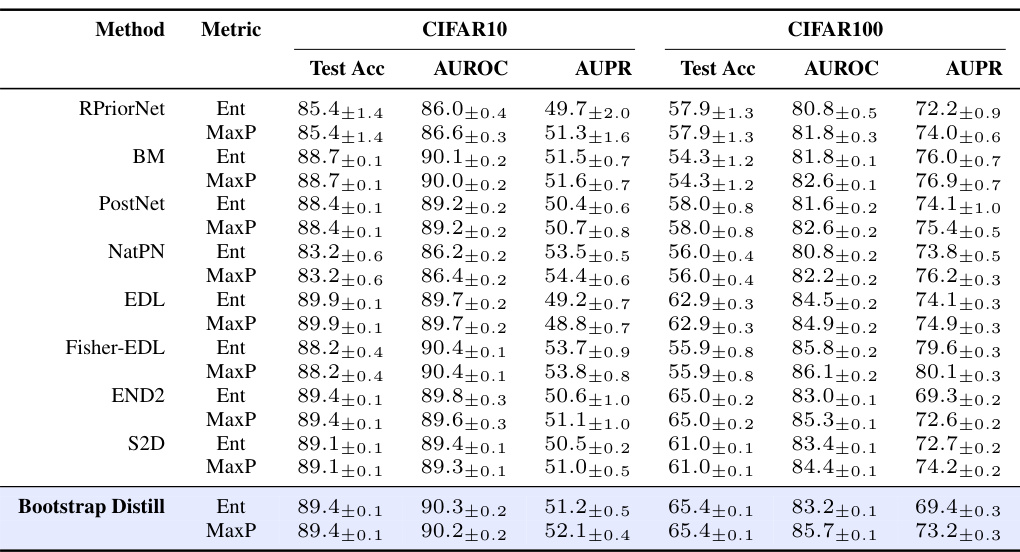

More on tables

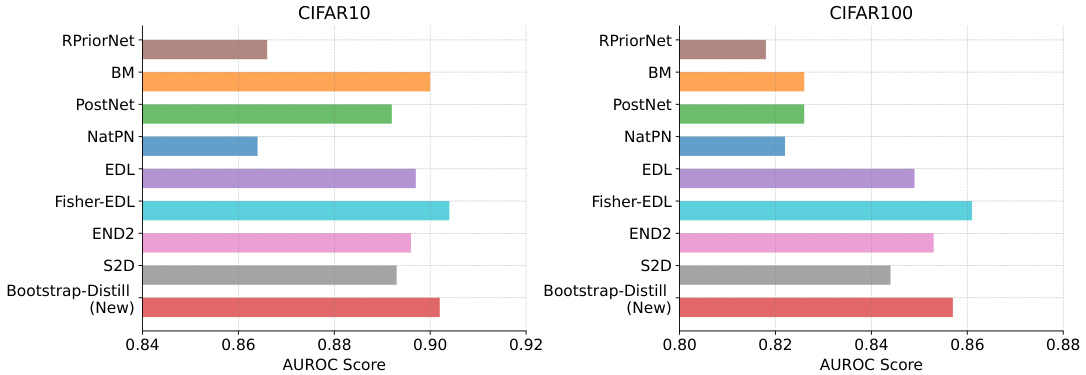

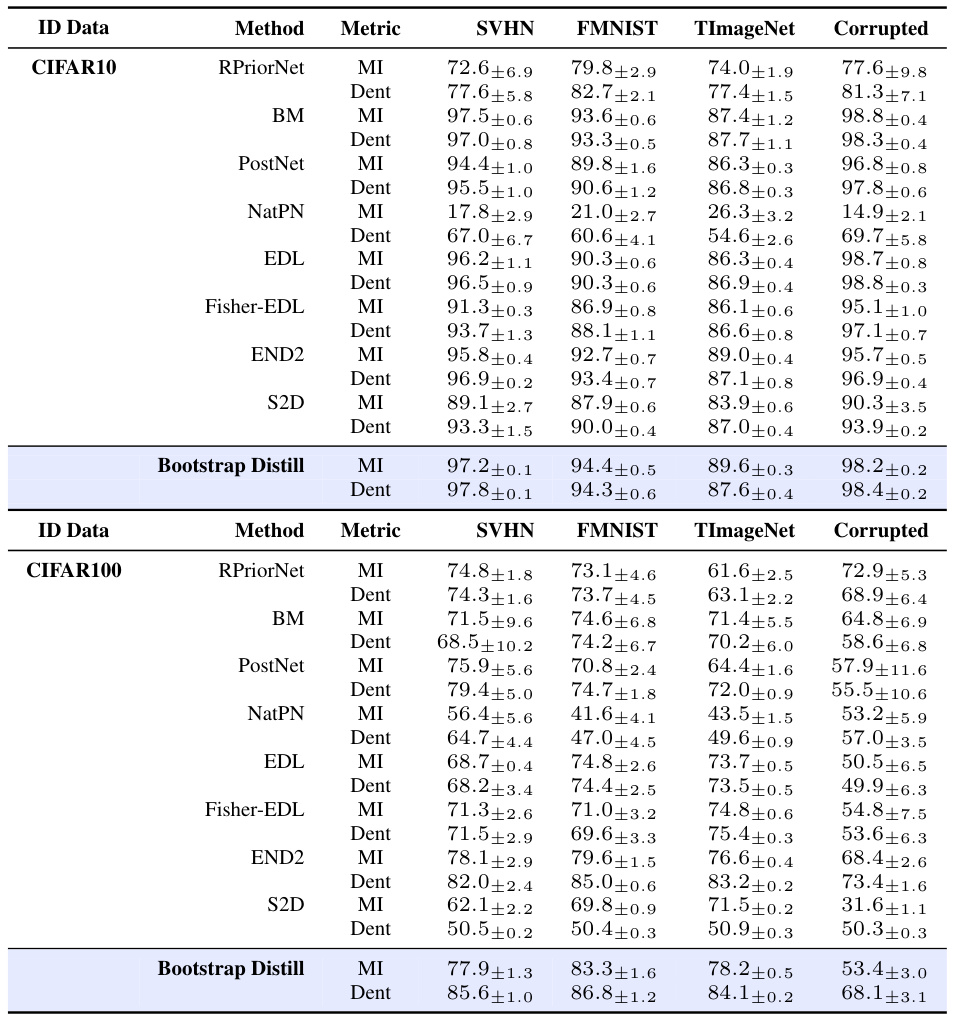

This table presents the AUROC scores for out-of-distribution (OOD) detection using different uncertainty quantification methods. The results are broken down by method (e.g., RPriorNet, BM, etc.), metric (Mutual Information or Differential Entropy), and OOD dataset (SVHN, FMNIST, TinyImageNet, Corrupted). It allows comparison of different methods’ performance in identifying OOD data across various datasets, using two different uncertainty metrics.

This table presents the AUROC scores for out-of-distribution (OOD) detection, using both Mutual Information (MI) and Differential Entropy (Dent) as metrics. It compares various EDL methods (RPriorNet, BM, PostNet, NatPN, EDL, Fisher-EDL, END2, S2D, and Bootstrap Distill) across four different OOD datasets (SVHN, FMNIST, TinyImageNet, and Corrupted) for two in-distribution datasets (CIFAR10 and CIFAR100). The table allows for a quantitative comparison of the effectiveness of different EDL methods in detecting OOD samples.

This table presents the average AUROC scores for OOD detection across four different OOD datasets (SVHN, FMNIST, TinyImageNet, and Corrupted) for various uncertainty quantification methods. The methods are grouped into classical EDL methods (RPriorNet, BM, PostNet, NatPN, EDL, Fisher-EDL) and distillation-based methods (END2, S2D, Bootstrap Distill). The table shows results for both CIFAR10 and CIFAR100 as the in-distribution datasets. Two metrics, Mutual Information (MI) and Differential Entropy (Dent), are used to quantify uncertainty. The table allows comparison of the performance of different methods for identifying out-of-distribution data.

Full paper#