↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Causal bandits (CBs) optimize experiments in systems with causal interactions. Existing CB algorithms either assume a known causal graph or rely on restrictive hard interventions. This significantly limits their applicability to real-world problems with complex, unknown causal relationships and inherently stochastic interventions. This is a challenge for algorithm design and regret analysis.

This paper tackles the problem by considering unknown graphs and soft interventions. The authors establish upper and lower regret bounds for this setting, showing that regret scales sublinearly with time. Importantly, the impact of graph size diminishes with time horizon. They also propose a novel algorithm that is computationally efficient and addresses the scalability challenges posed by soft interventions. This work substantially advances CB research, opening new directions for algorithm design and applications in complex systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on causal bandits because it addresses a previously unsolved problem: designing efficient algorithms for causal bandits with unknown graphs and soft interventions. This significantly advances the field, particularly in scenarios with realistic soft interventions that maintain the stochasticity of systems. The findings provide new theoretical bounds and an efficient algorithm, impacting various applications. This research paves the way for broader applications of causal bandits in areas where graph structures are complex or unknown, opening new avenues for further exploration.

Visual Insights#

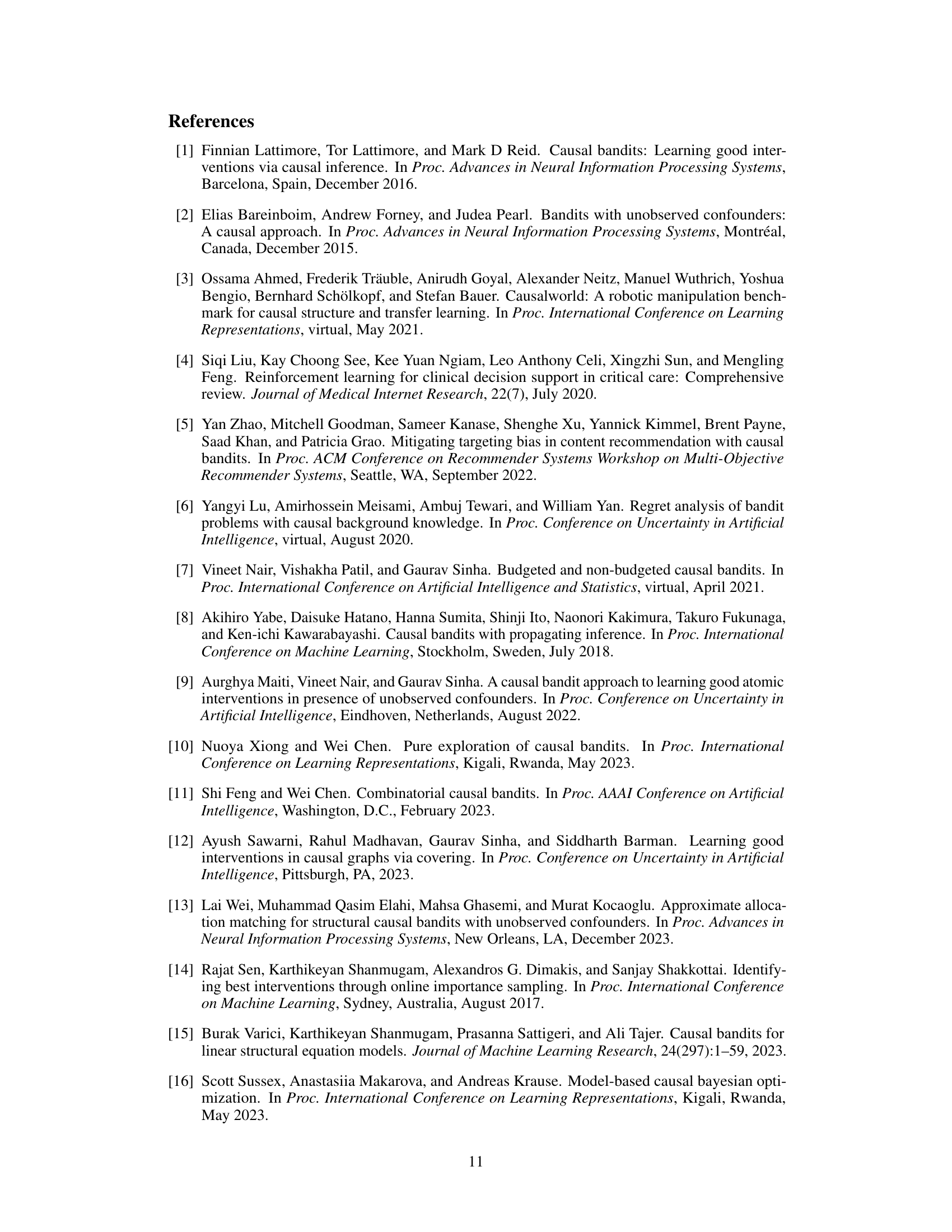

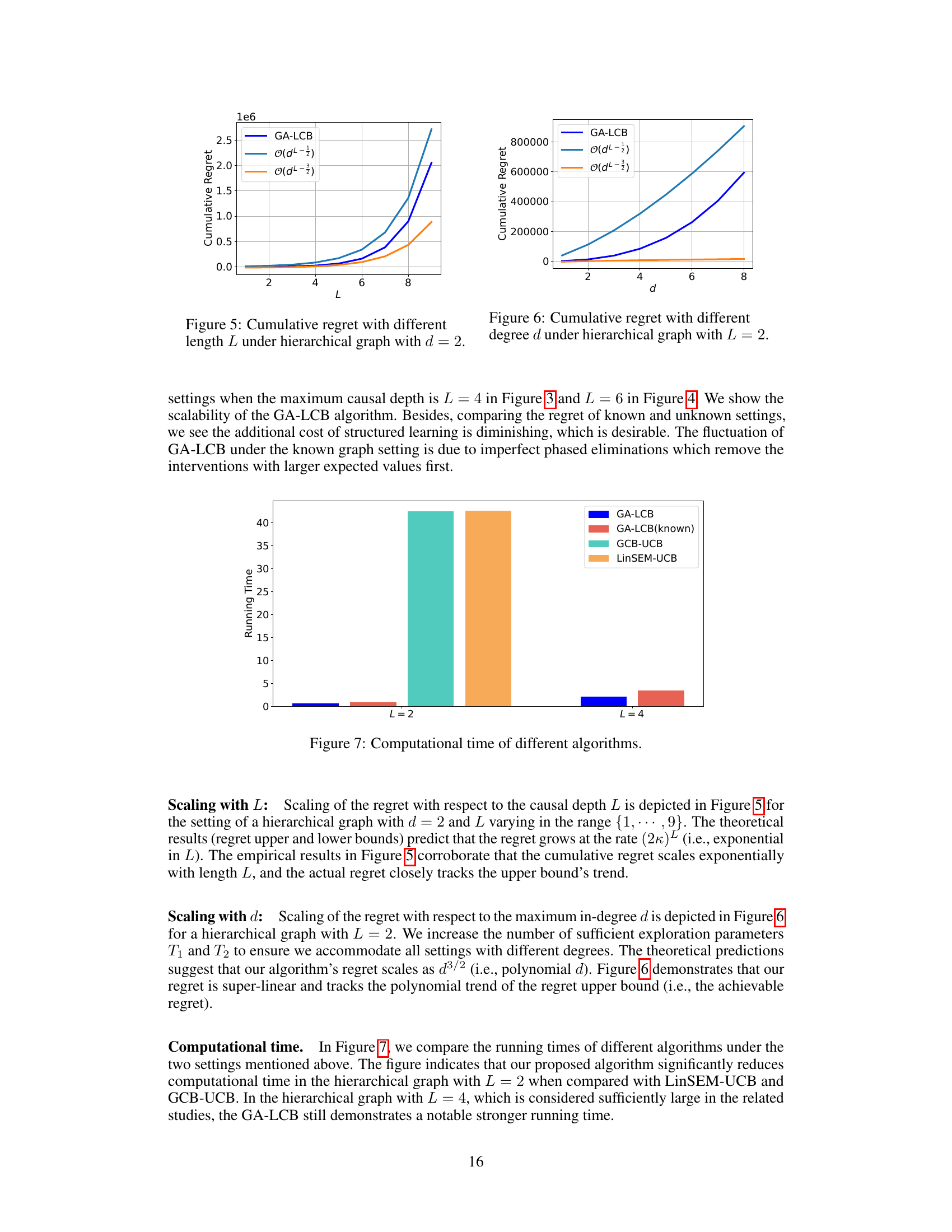

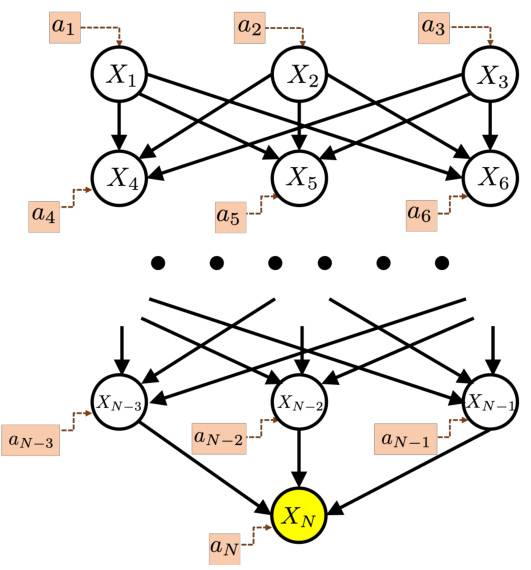

This figure shows a hierarchical graph structure used in the paper’s experiments. The graph has L+1 layers, where the top L layers contain d nodes each. Nodes in adjacent layers are fully connected. The bottom layer consists of a single reward node (XN) connected to all nodes in the topmost layer. This structure allows for varying graph depth (L) and maximum in-degree (d) to evaluate algorithm performance under different graph topologies. The ai symbols represent the interventions available at each node.

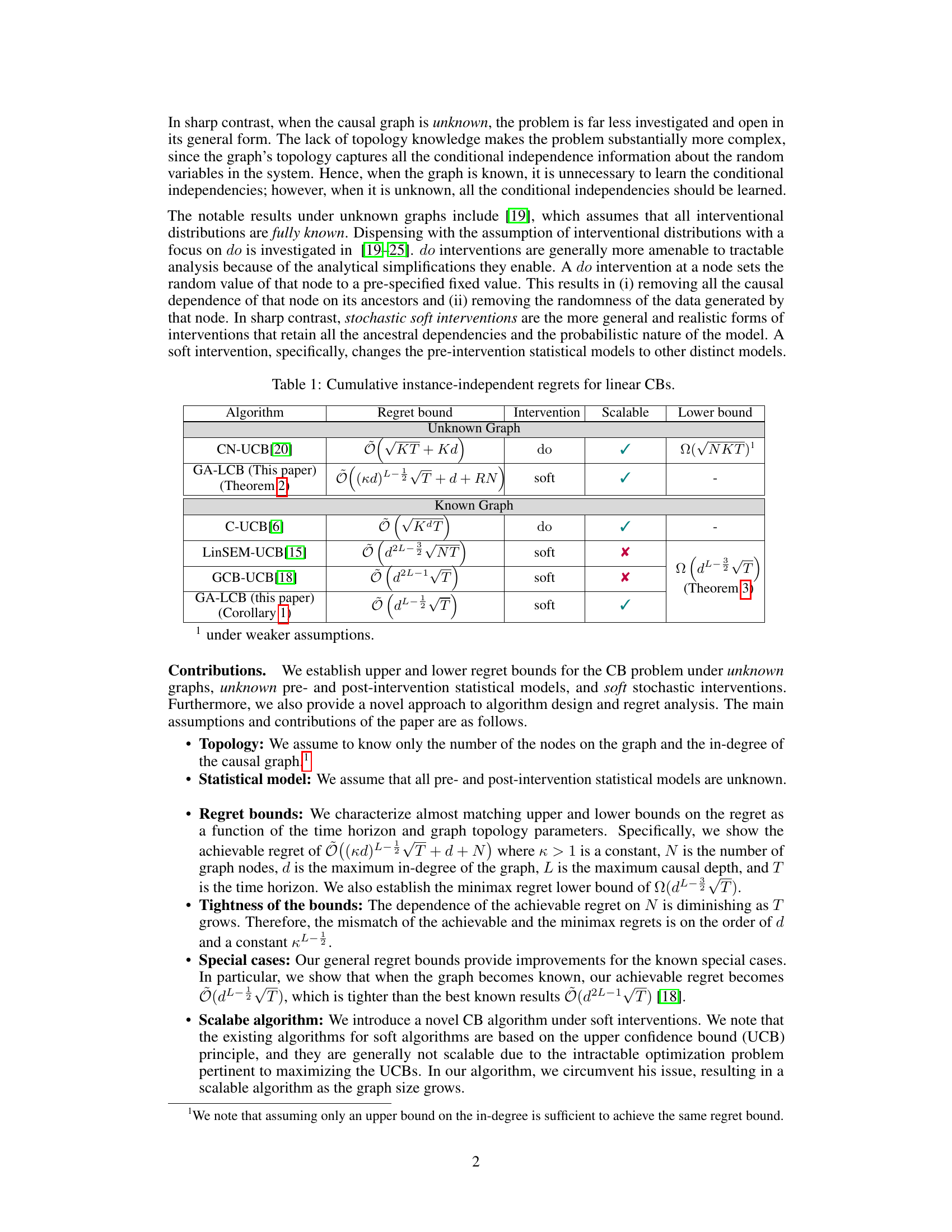

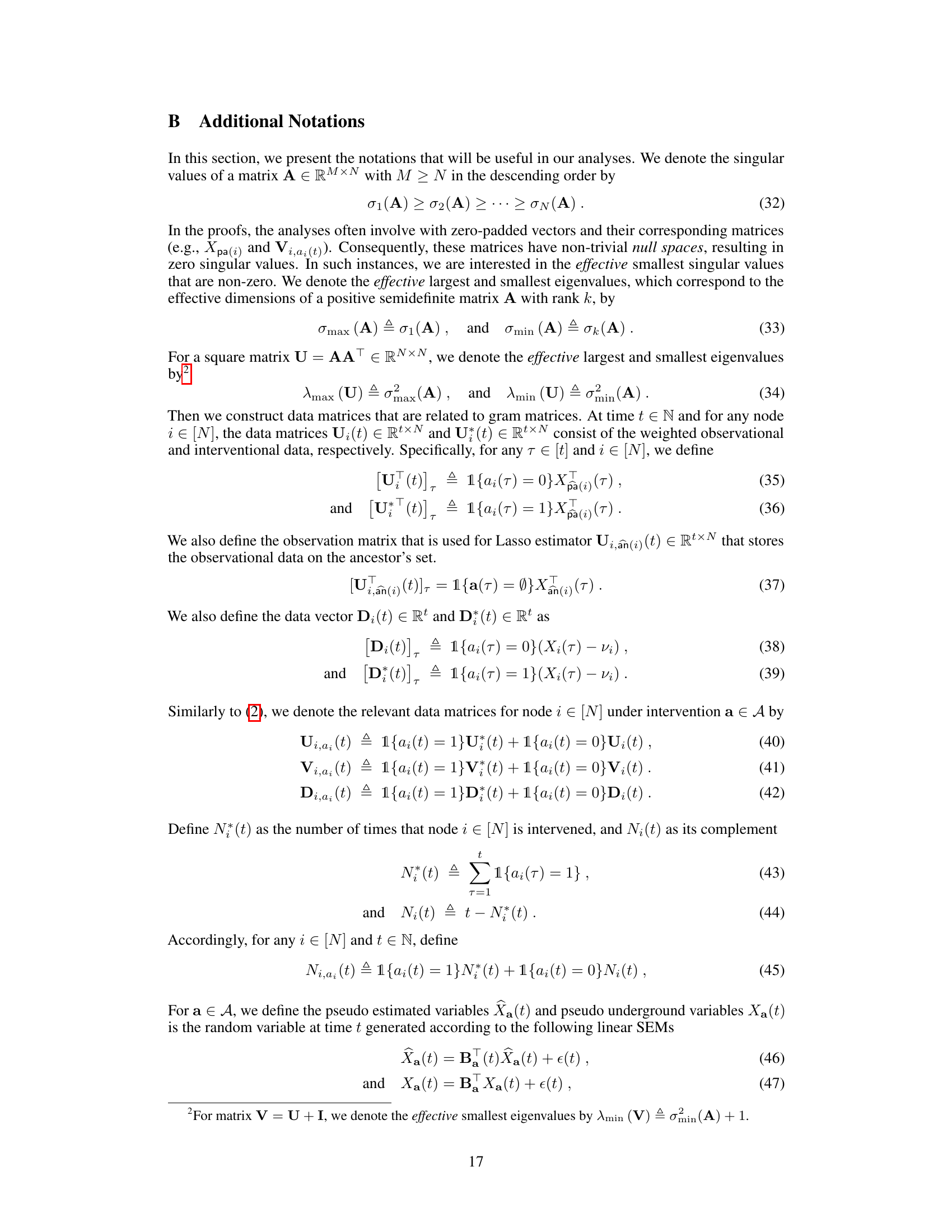

This table compares the cumulative instance-independent regret bounds for various linear Causal Bandit (CB) algorithms. It categorizes algorithms based on whether they assume a known or unknown causal graph and whether they use hard/do interventions or soft interventions. The regret bounds are expressed using Big-O notation, showing the scaling with respect to key parameters such as the number of interactions (T), the number of arms (K), the maximum in-degree of the graph (d), and the maximum causal path length (L). A checkmark indicates whether the algorithm is scalable. The lower bounds provide theoretical limits on the achievable regret. The table highlights the contribution of the paper, GA-LCB, which achieves near-optimal regret bounds for the most general setting of an unknown graph and soft interventions.

In-depth insights#

Unknown Graph CBs#

The study of causal bandits (CBs) with unknown graphs presents a significant challenge due to the added complexity of learning the underlying causal structure alongside the optimal interventions. Unlike scenarios with known graphs, where the relationships between variables are predefined, unknown graph CBs require simultaneously learning the graph topology and estimating optimal interventions. This necessitates algorithms that can efficiently explore and exploit the causal relationships while handling the inherent uncertainty in the graph structure. The main difficulty stems from the exponential growth in the number of possible causal graphs with the number of nodes, making exhaustive search computationally intractable. Therefore, efficient algorithms are crucial, focusing on techniques like structure learning to estimate the graph. Regret analysis in this context becomes more challenging, needing to account for errors in both graph structure learning and intervention selection. The paper’s contribution lies in addressing this problem by establishing upper and lower bounds on regret while introducing a scalable algorithm for CBs under soft interventions in unknown graph settings. The emphasis is on soft interventions, a more realistic model compared to restrictive hard interventions, which presents unique challenges to the algorithm’s design and analysis.

Soft Intervention Regret#

The concept of ‘Soft Intervention Regret’ in causal bandits focuses on the cumulative difference between the rewards obtained by an optimal policy and a policy that learns under soft interventions. Soft interventions, unlike hard interventions, don’t completely remove causal links but rather modify the underlying conditional probability distributions. This makes learning under soft interventions more complex. Analyzing the regret requires considering the uncertainty involved in learning unknown interventional distributions within an unknown causal graph. The regret is expected to be affected by factors like the graph’s topology (depth and in-degree), intervention strength, and the time horizon. Establishing tight upper and lower bounds for the regret under various conditions would be crucial to understanding the algorithm’s efficiency and optimality, as it quantifies the cost of not knowing the true causal structure or precise interventional distributions.

GA-LCB Algorithm#

The Graph-Agnostic Linear Causal Bandit (GA-LCB) algorithm presents a novel approach to address the challenge of causal bandit problems with unknown graphs and soft interventions. Its two-stage design cleverly separates structure learning from intervention selection. The first stage, GA-LCB-SL, efficiently estimates the causal graph structure using a sequence of carefully designed interventions. This avoids the computational intractability of directly optimizing over all possible graphs. The second stage, GA-LCB-ID, leverages the learned structure to guide intervention selection, using a scalable refinement strategy based on upper confidence bounds (UCBs). This avoids the exponential complexity of conventional UCB approaches. GA-LCB achieves almost minimax optimal regret bounds, demonstrating its efficiency despite the significant challenges posed by the problem’s inherent uncertainty. The algorithm’s key innovation lies in its ability to efficiently explore the intervention space and learn the graph structure simultaneously, thus balancing exploration-exploitation effectively in a computationally tractable manner.

Regret Bounds#

The section on ‘Regret Bounds’ is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of causal bandit algorithms. The authors establish both upper and lower bounds on the regret, quantifying the algorithm’s performance relative to an optimal strategy. The upper bound reveals the worst-case cumulative regret, showcasing how algorithm performance scales with key factors like time horizon (T), maximum in-degree (d), and maximum causal path length (L). Importantly, the upper bound demonstrates that the impact of graph size (N) diminishes over time. The lower bound provides a fundamental limit on achievable performance, proving the optimality of their algorithm. The matching behavior of the upper and lower bounds (except for a polynomial gap in d) indicates the algorithm’s near-optimality. The analysis highlights the exponential dependence on L, suggesting that algorithms struggle in deep causal graphs, and a polynomial dependence on d, underlining the impact of graph complexity. These bounds provide valuable insights into the algorithm’s scalability and limitations, offering a theoretical guarantee on its performance in diverse causal settings.

Scalable CBs#

Scalable causal bandits (CBs) are crucial for addressing the challenges of large-scale experimentation. Existing CB algorithms often struggle with computational complexity, particularly when dealing with unknown causal graphs and soft interventions. The core challenge lies in the exponential growth of the intervention space with the number of nodes, making exhaustive search or traditional UCB approaches infeasible. A scalable CB algorithm requires efficient ways to learn the causal graph structure and to identify promising interventions without exploring the entire space. This might involve novel techniques such as leveraging heuristics, approximate inference, or efficient optimization algorithms. The success of a scalable CB algorithm hinges on carefully balancing exploration and exploitation in a computationally tractable way. This might require developing new theoretical bounds tailored to scalable settings and demonstrating their effectiveness through both theoretical analysis and empirical evaluations on realistic large-scale datasets. Techniques like dimensionality reduction or hierarchical approaches could help in achieving scalability while maintaining sufficient accuracy in estimating the reward function. Future research in this area should focus on developing such advanced algorithms and rigorously evaluating their performance and limitations in various complex real-world scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

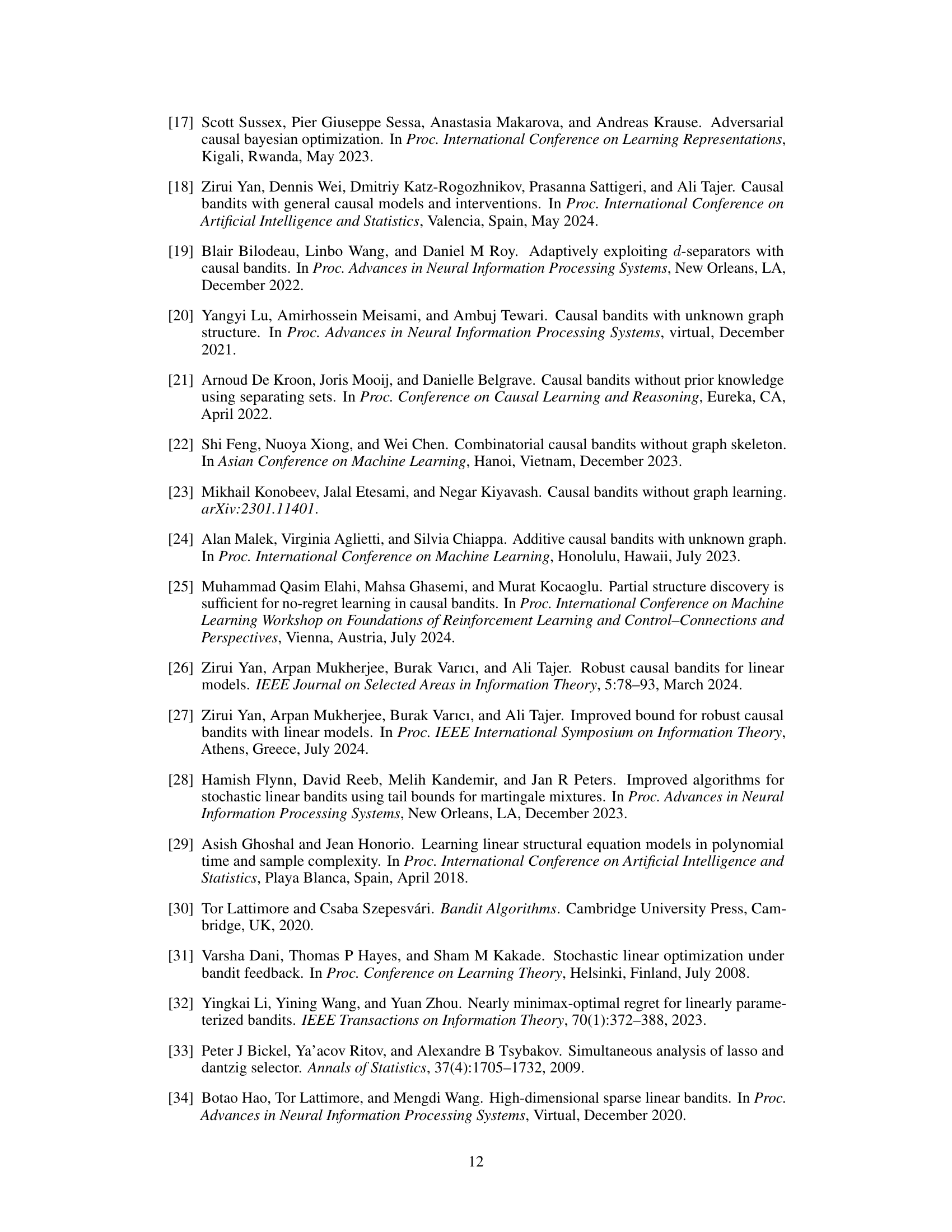

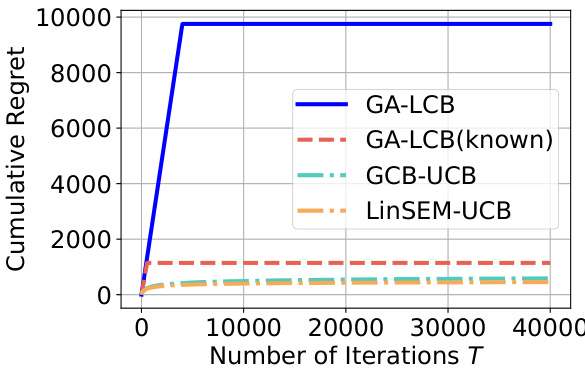

This figure shows the cumulative regret for different causal bandit algorithms with a hierarchical graph where the maximum causal depth L is 2. The x-axis represents the number of iterations, and the y-axis represents the cumulative regret. The algorithms compared are GA-LCB (Graph-Agnostic Linear Causal Bandit), GA-LCB (known) (GA-LCB with known graph structure), GCB-UCB (Graph Causal Bandit - Upper Confidence Bound), and LinSEM-UCB (Linear Structural Equation Model - Upper Confidence Bound). GA-LCB demonstrates a significantly higher initial regret due to the structure learning phase, but its regret plateaus as the number of iterations increases. In contrast, the other algorithms exhibit much lower but less scalable regret.

This figure shows the cumulative regret for different causal bandit algorithms (GA-LCB, GA-LCB(known), GCB-UCB, and LinSEM-UCB) over 40000 iterations on a hierarchical graph with a causal depth of L=2 and maximum in-degree of d=3. GA-LCB is the proposed algorithm in this paper, and GA-LCB(known) represents the performance of the algorithm with prior knowledge of the graph structure. The figure demonstrates the performance comparison among these algorithms, indicating GA-LCB’s performance relative to state-of-the-art algorithms in the presence of uncertainty about the causal graph. Note that GA-LCB shows slightly higher regret than GA-LCB(known) during the initial iterations, which can be explained by the initial structure learning and exploration.

This figure shows the cumulative regret for different causal bandit algorithms (GA-LCB, GCB-UCB, LinSEM-UCB) on a hierarchical graph with causal depth L=2. The x-axis represents the number of iterations, and the y-axis represents the cumulative regret. GA-LCB shows initially higher regret than the other two algorithms, due to its structure learning phase, but the regret converges to a relatively stable level after some iterations.

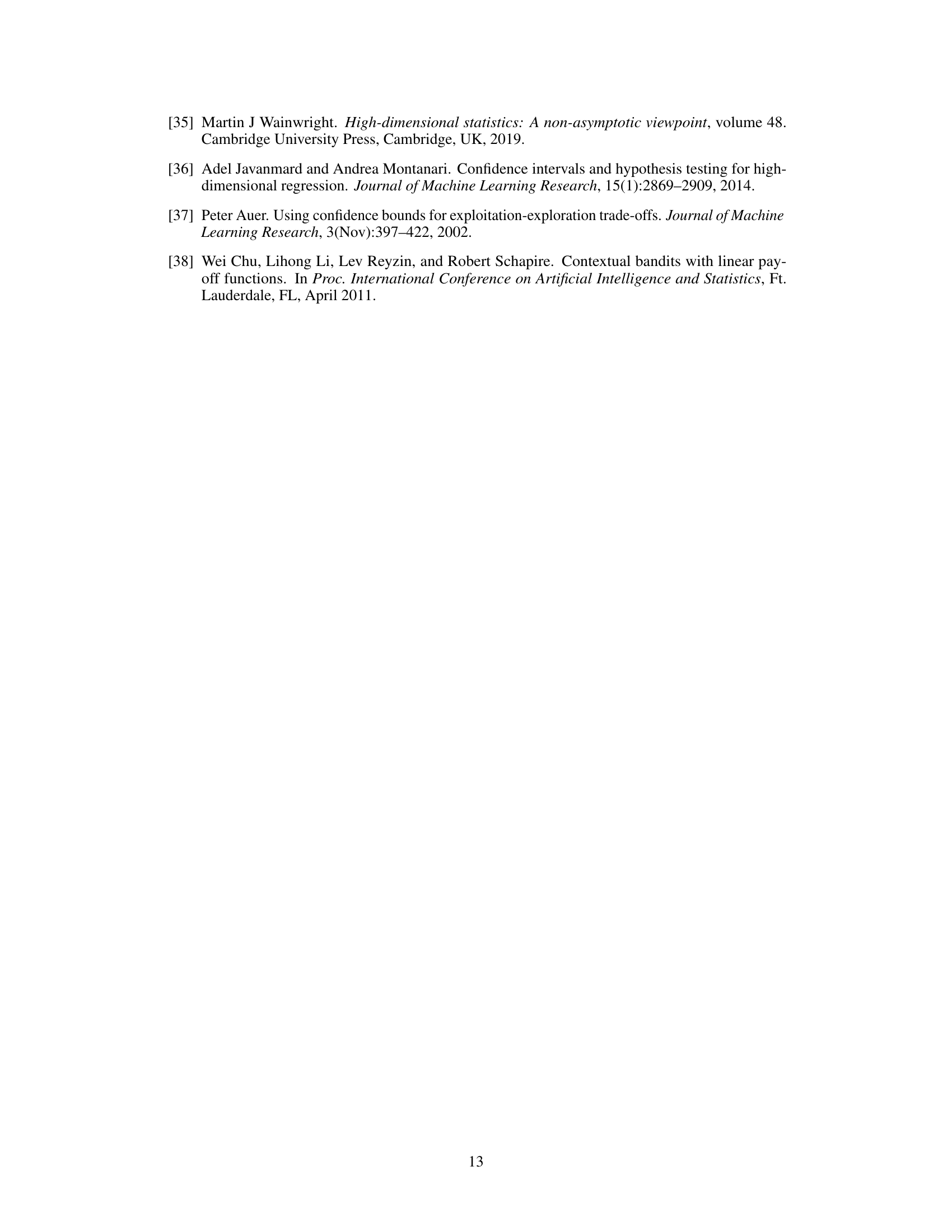

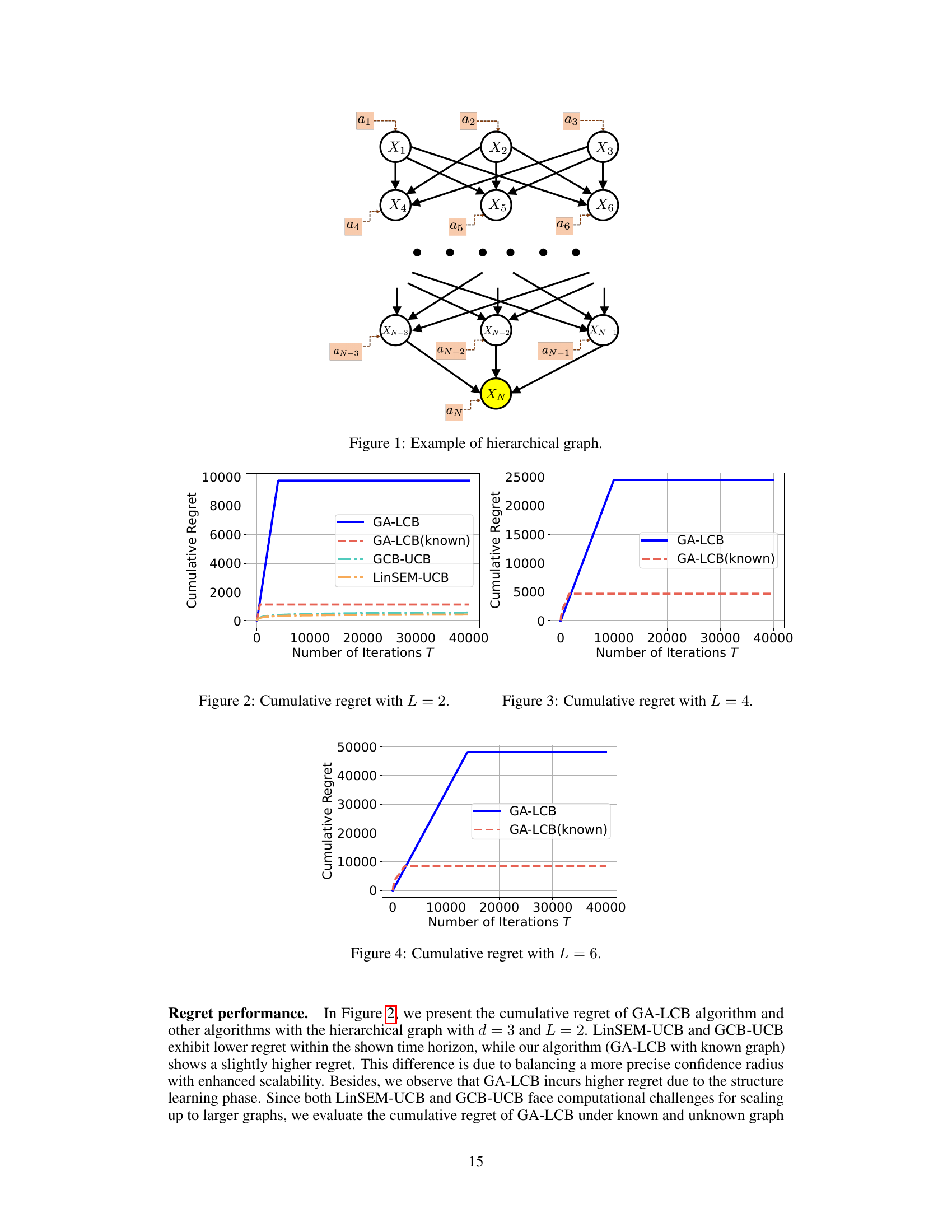

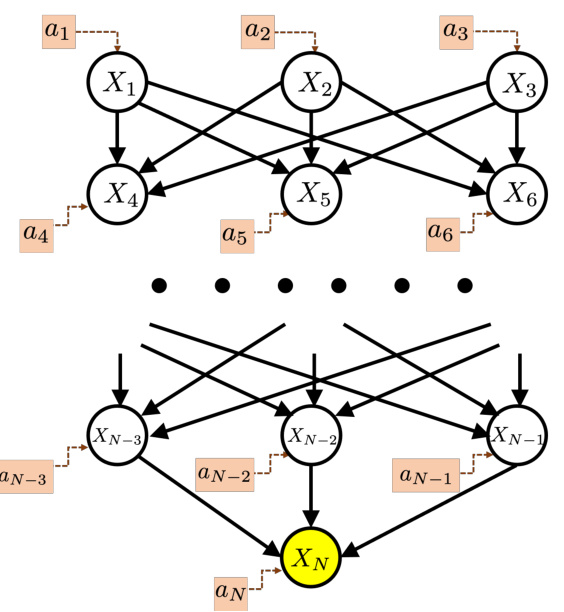

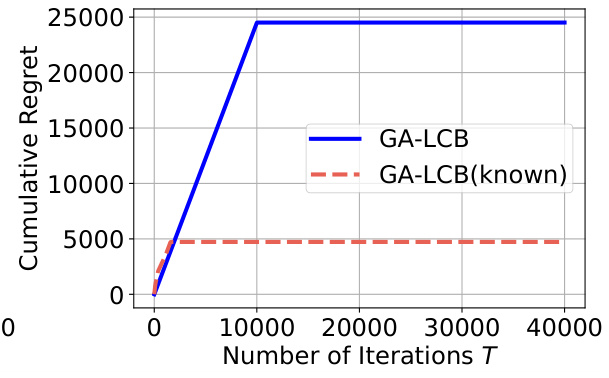

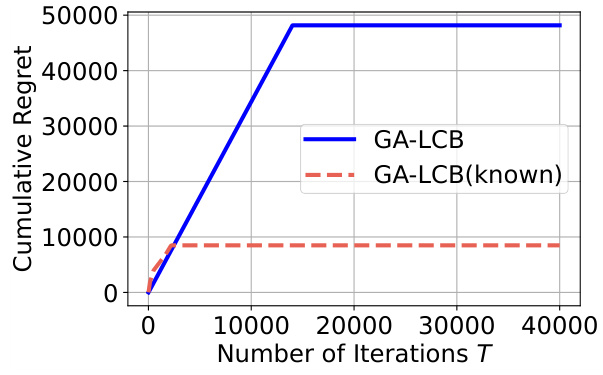

This figure shows the cumulative regret of the GA-LCB algorithm under different causal depth L. The x-axis represents the causal depth L, and the y-axis represents the cumulative regret. The figure shows that the cumulative regret increases exponentially with the causal depth L, which is consistent with the theoretical results in the paper. The figure also shows the cumulative regret of GA-LCB under known and unknown graph settings. The cumulative regret under the unknown graph setting is slightly higher than the cumulative regret under the known graph setting. This is because the GA-LCB algorithm needs to learn the graph structure under the unknown graph setting, which introduces additional regret.

This figure shows the empirical cumulative regret of the GA-LCB algorithm with different maximum in-degree values (d) under a hierarchical graph structure with a fixed maximum causal depth (L=2). It compares the empirical results with the theoretical upper and lower bounds of O(dL−1/2√T) and O(d3/2L−3/2√T) respectively. The plot demonstrates that as the maximum in-degree increases, the cumulative regret also increases, aligning with the theoretical findings in the paper. The empirical results fall between the upper and lower bounds, indicating the effectiveness of the proposed GA-LCB algorithm.

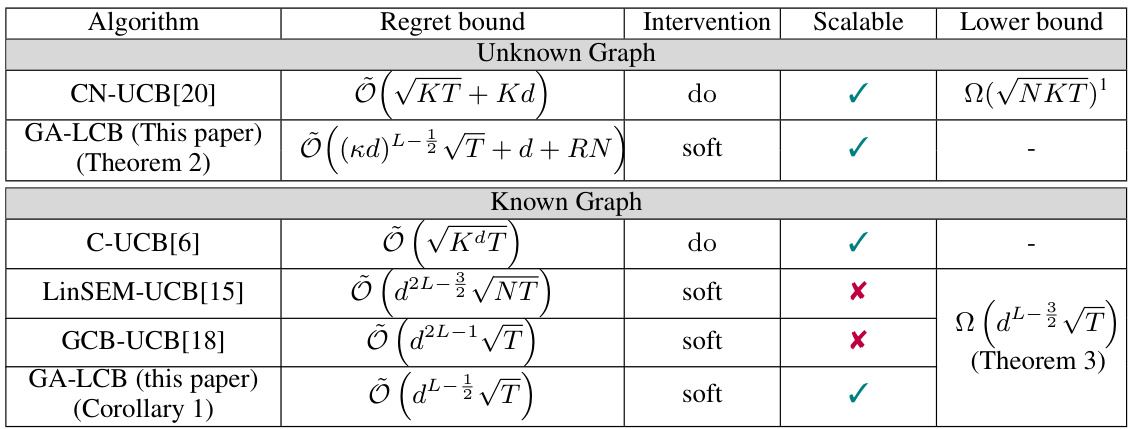

This figure compares the computational time of four different causal bandit algorithms: GA-LCB, GA-LCB (with known graph), GCB-UCB, and LinSEM-UCB. The algorithms are evaluated on hierarchical graphs with different causal depths (L=2 and L=4). The results show that GA-LCB, designed for unknown graphs, has a significantly lower computational time compared to the other algorithms, particularly in larger graphs (L=4). The computational advantage is attributed to GA-LCB’s efficient algorithm design, particularly avoiding computationally expensive optimization.

This figure shows an example of a hierarchical graph used in the paper’s experiments. The graph has multiple layers of nodes, where nodes in adjacent layers are fully connected. Each node represents a variable, and the edges represent causal relationships between them. The last layer contains a single node, representing the reward variable, which is fully connected to all nodes in the previous layer. Soft interventions can be applied to any subset of nodes, aiming to maximize the value of the reward node. The structure illustrates the complexity of the problem addressed by the GA-LCB algorithm, especially when the underlying graph structure is unknown.

Full paper#