TL;DR#

Protein structure generation is crucial for drug discovery but challenging due to the complexity of protein folding and the need for high diversity and designability in generated structures. Existing generative models often fail to produce proteins with desired properties, particularly when dealing with conditional design tasks involving specified functional properties or target motifs. This research addresses these limitations by introducing a new model that efficiently handles sequence and structure information.

This new model, called FOLDFLOW-2, uses a sequence-conditioned SE(3)-equivariant flow matching approach. It leverages a large language model to encode sequence information, combines structure and sequence representations effectively, and incorporates a geometric transformer-based decoder. The results show that FOLDFLOW-2 significantly outperforms previous models across all metrics, including designability, diversity, and novelty. Furthermore, its ability to handle conditional design tasks is a major advance, paving the way for new applications in drug design and biological engineering.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel method for protein backbone generation that outperforms existing state-of-the-art models. The method’s ability to handle multi-modal data (structure and sequence) and generate diverse protein structures is crucial for drug discovery and other applications. The introduction of Reinforced Finetuning also opens exciting new avenues for aligning generative models to arbitrary rewards. This work addresses key challenges in protein design and significantly advances the field.

Visual Insights#

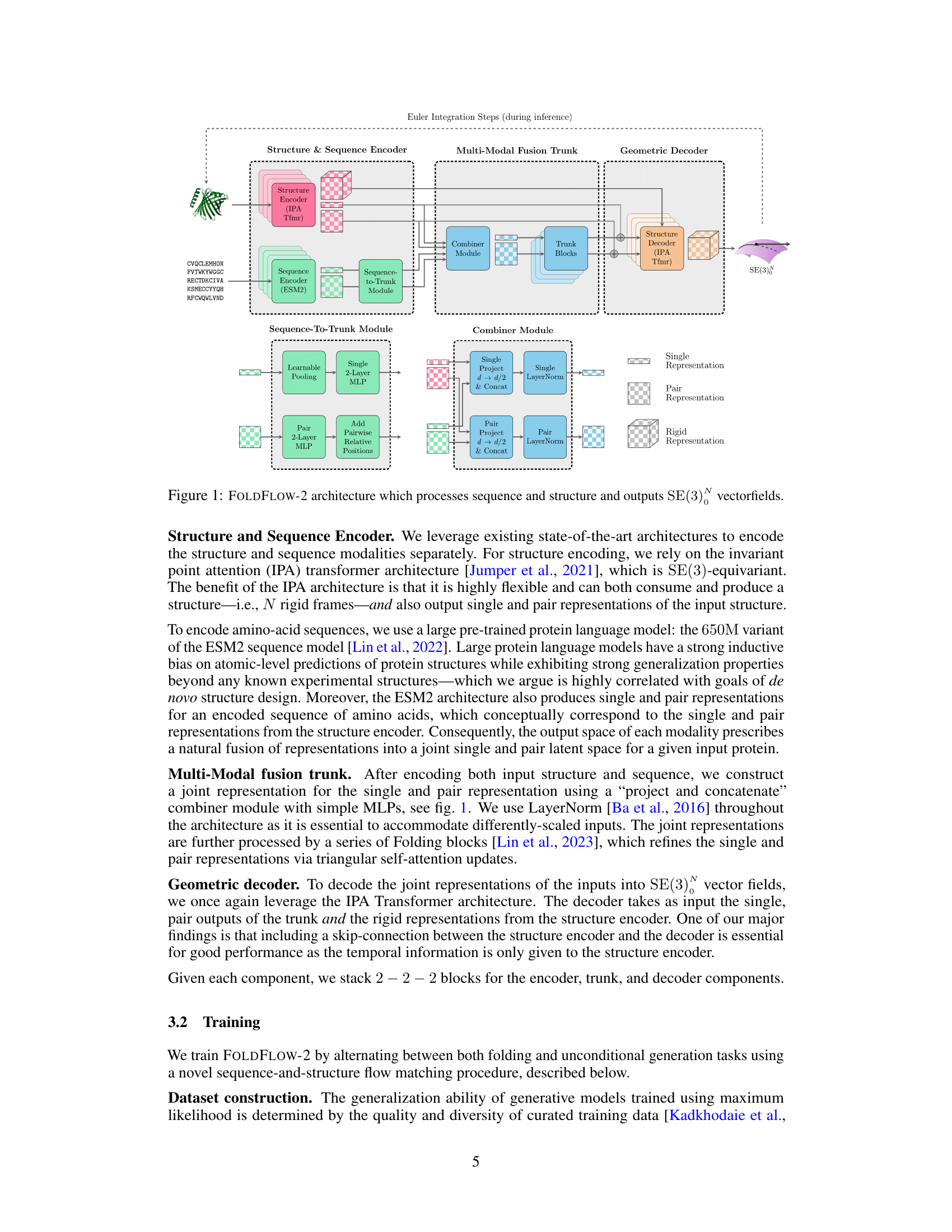

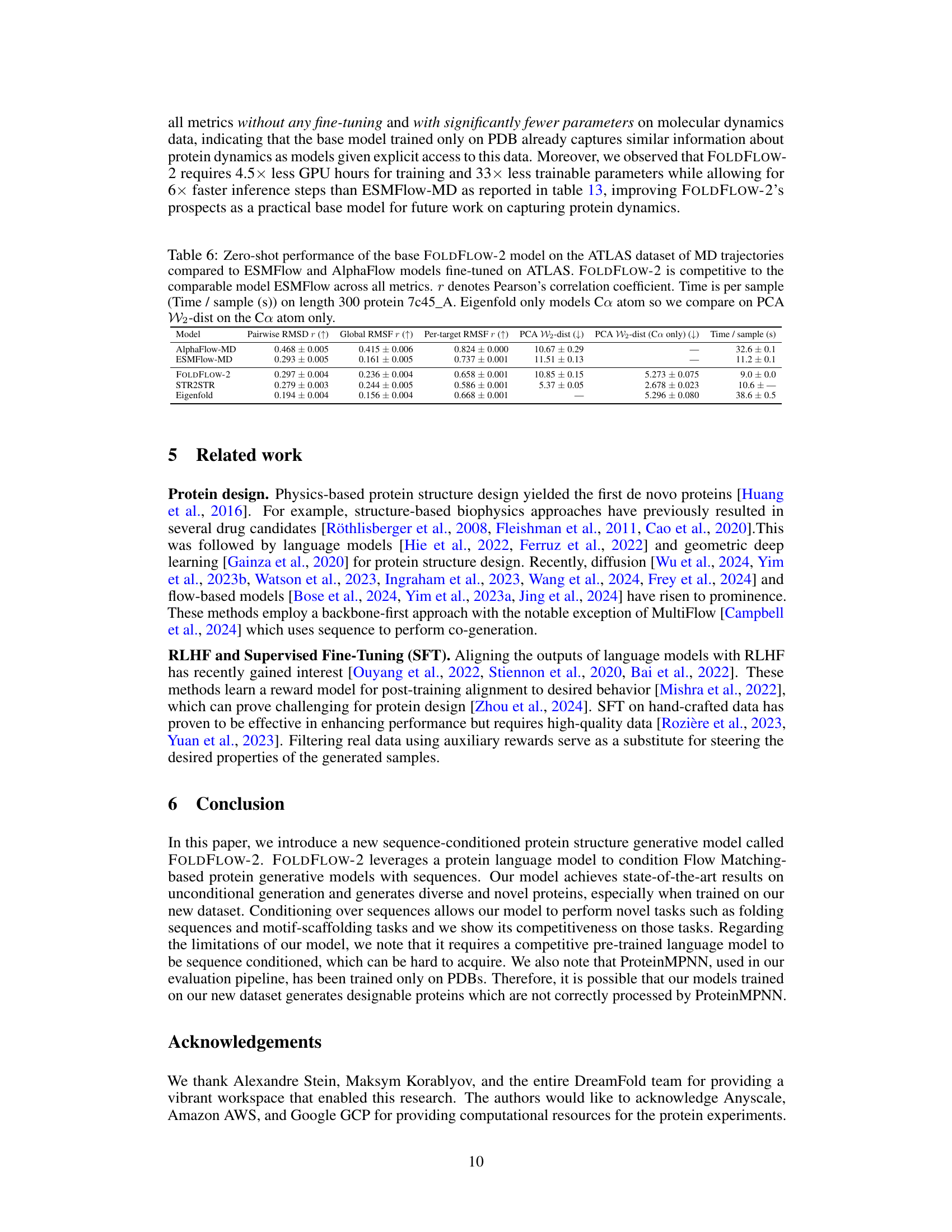

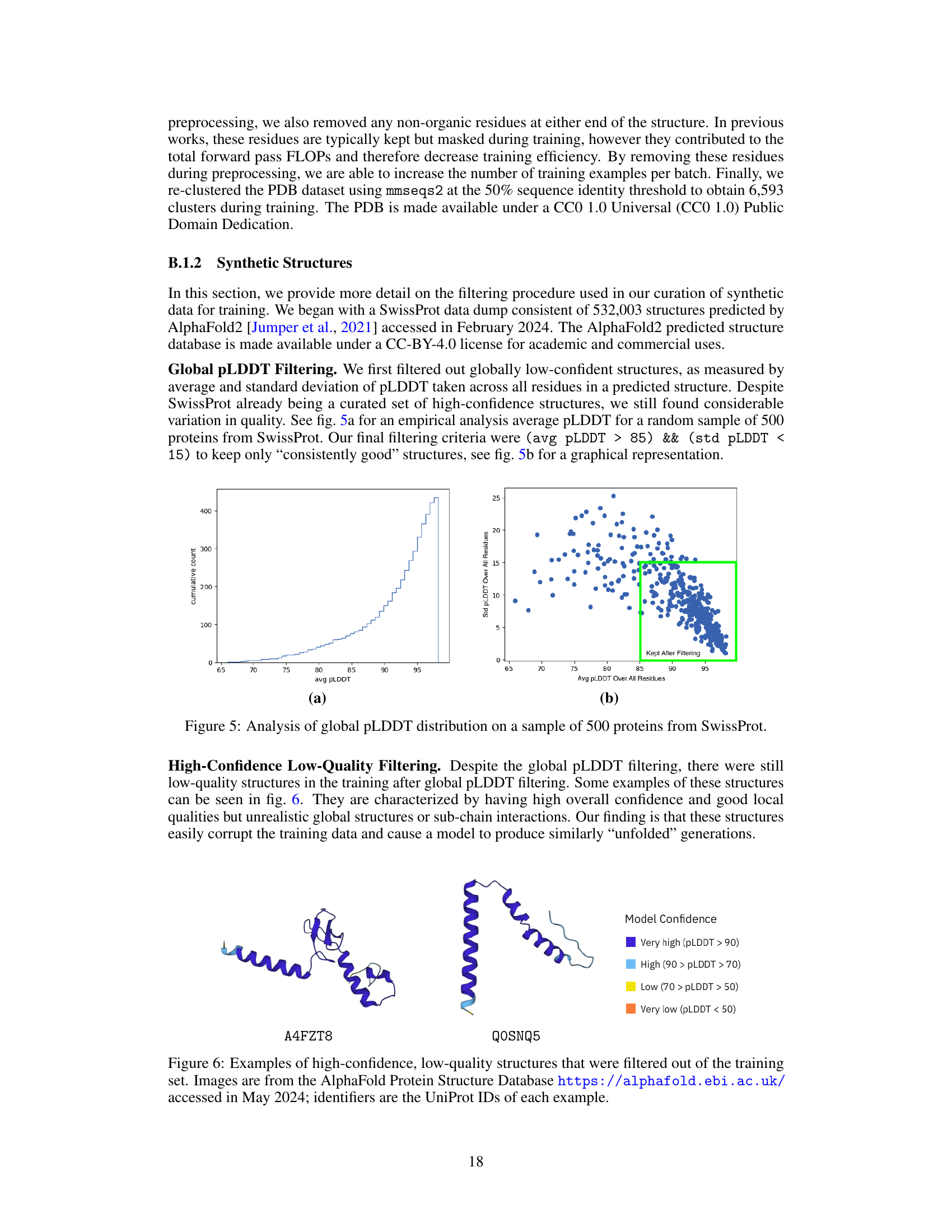

🔼 The figure shows the architecture of the FOLDFLOW-2 model. It consists of three main components: a structure and sequence encoder, a multi-modal fusion trunk, and a geometric decoder. The encoder processes both the 3D structure of the protein backbone and its amino acid sequence separately. The fusion trunk combines these two representations into a shared representation. Finally, the decoder generates SE(3) vector fields, which represent the protein’s 3D structure.

read the caption

Figure 1: FOLDFLOW-2 architecture which processes sequence and structure and outputs SE(3) vectorfields.

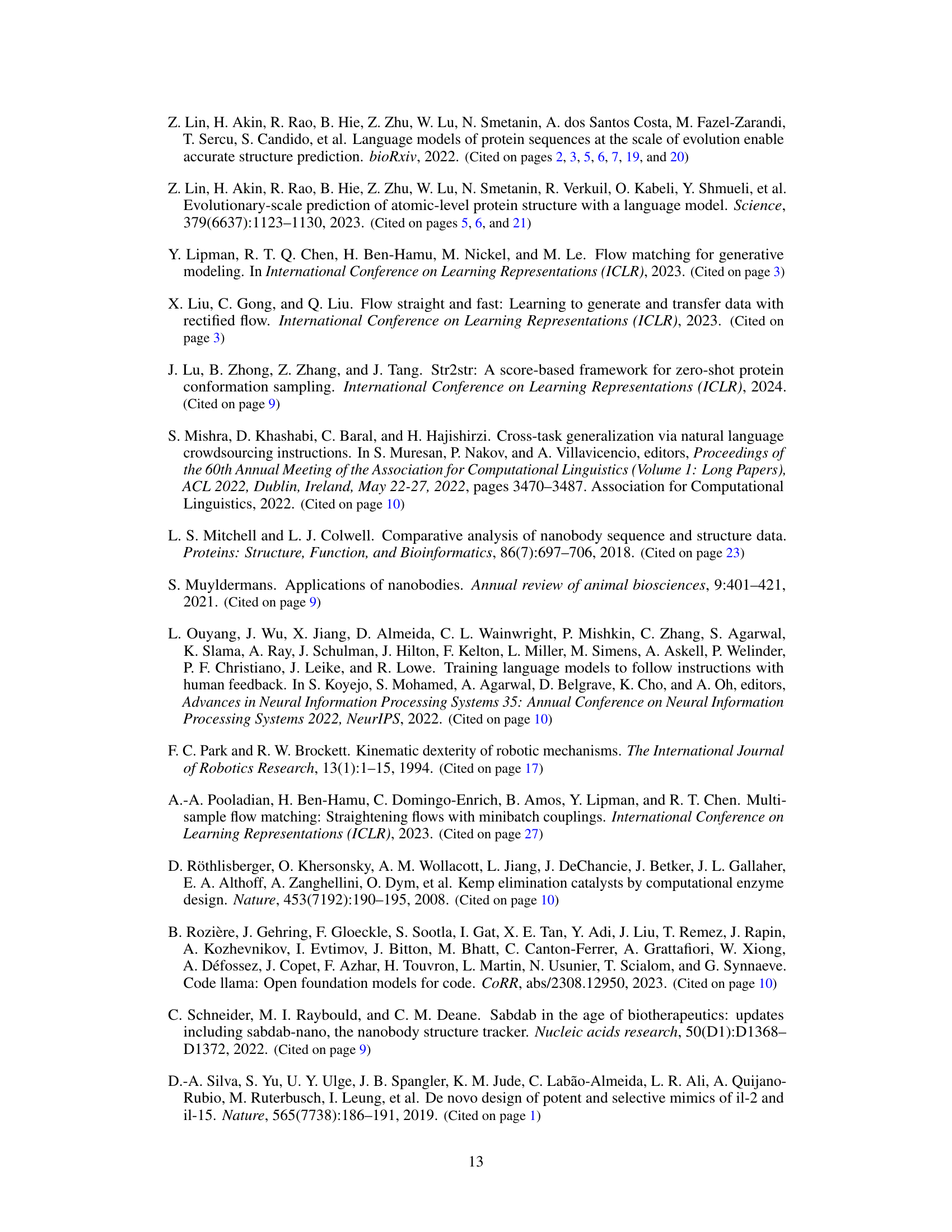

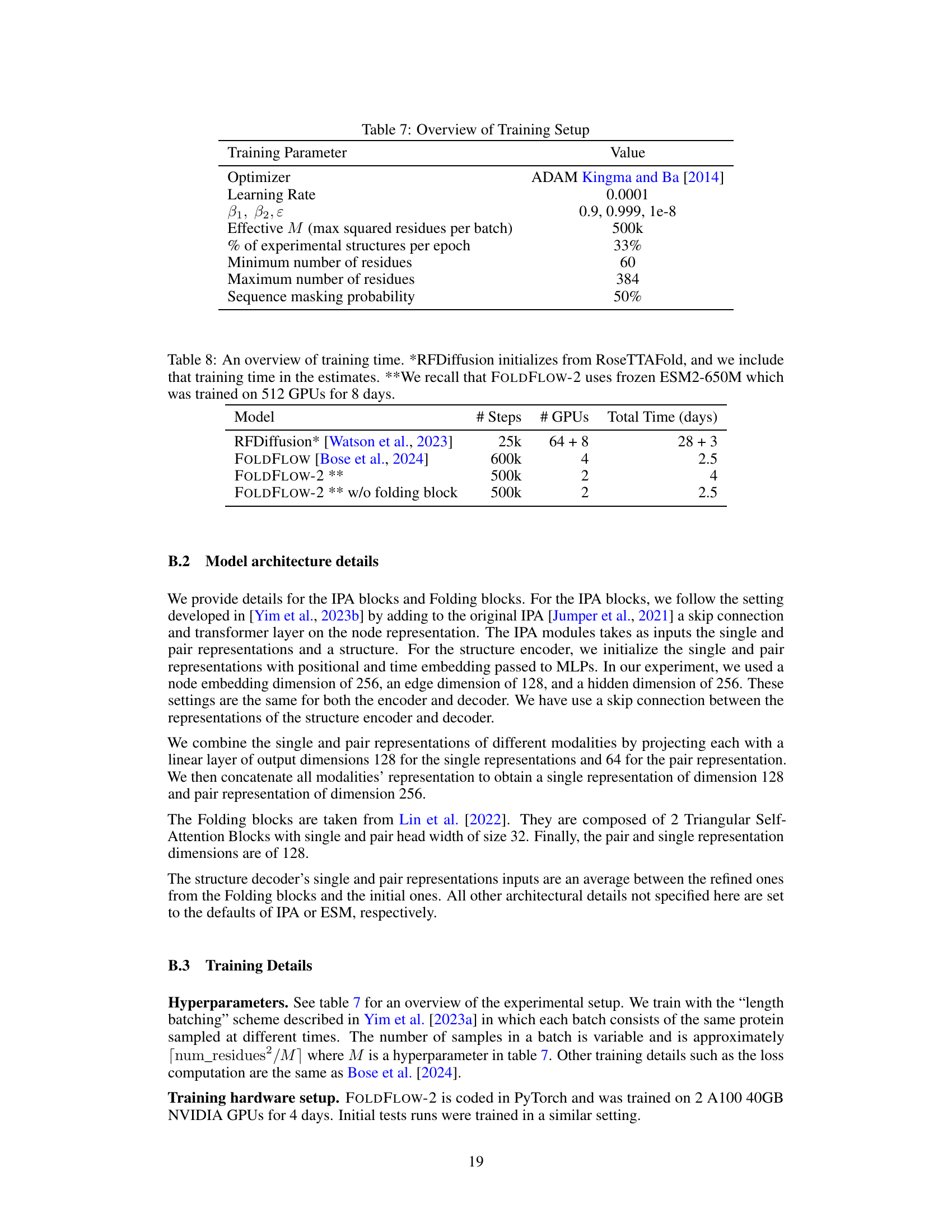

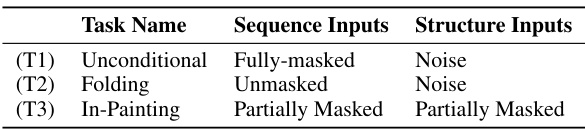

🔼 This table summarizes the capabilities of various protein backbone generation models in terms of their ability to perform unconditional generation, folding (generating structures given a sequence), and inpainting (generating structures given a partially masked structure and sequence). Each model is represented by a checkmark in the column that indicates its ability to perform the corresponding task.

read the caption

Table 1: Overview of the conditioning capability of unconditional (Ø), folding (A), and inpainting (A, X) of various protein backbone generation models.

In-depth insights#

SE(3)-Equivariant Flow#

SE(3)-equivariant flows offer a powerful approach to generative modeling of 3D data, such as protein structures, by directly incorporating the symmetries of the special Euclidean group SE(3). This approach ensures that the generated structures are invariant to rotations and translations, a crucial property for representing protein backbones. Unlike standard flows that operate on Euclidean spaces, SE(3)-equivariant flows directly model the manifold structure of SE(3), avoiding the need for computationally expensive transformations and potentially improving the quality and diversity of generated samples. The key advantage lies in learning representations that naturally respect the rotational and translational symmetries, leading to more physically realistic and interpretable models. However, working with SE(3) presents computational challenges, requiring specialized techniques for efficient computation of probability densities and flows on this non-Euclidean space. Despite these challenges, the benefits of building inherent symmetries into the generative model significantly outweigh the costs, particularly in applications like protein design, where physically meaningful structures are essential.

Sequence Conditioning#

Sequence conditioning in protein structure prediction involves leveraging the amino acid sequence of a protein to guide the generation of its 3D structure. This approach is crucial because the sequence contains vital information about the protein’s folding and function. Effective sequence conditioning methods improve the accuracy and biological relevance of generated structures by incorporating the inherent biological inductive bias of amino acid sequences. This bias reflects the evolutionary constraints and physical-chemical properties that govern protein folding. By conditioning on the sequence, models can better predict realistic conformations and avoid generating unrealistic or non-functional structures. Various methods exist, such as embedding the sequence information into the model’s input or using it to modulate the generation process. The choice of method can impact the quality of predictions, and optimal solutions often involve sophisticated techniques to handle the complexity of protein sequence-structure relationships. Successful incorporation of sequence information reduces the search space and enables the generation of more designable and diverse protein structures, with potential applications in drug discovery and protein engineering. However, challenges remain, especially in accurately capturing long-range interactions and handling sequence variations that might lead to alternative folds. Further research is needed to refine sequence conditioning approaches and push the boundaries of protein structure prediction.

Large-Scale Training#

Large-scale training of machine learning models, especially deep learning models, presents unique challenges and opportunities. Data volume is a primary concern; massive datasets are needed to train effectively, demanding significant storage and processing power. Computational resources are another key factor; training can take days, weeks, or even months on clusters of high-performance GPUs, incurring substantial costs. Model architecture must also be considered; designs need to scale efficiently, often requiring distributed training techniques to parallelize the computational load. Despite these obstacles, large-scale training unlocks the potential for state-of-the-art performance, allowing models to learn complex patterns and representations that would be impossible with smaller datasets. Generalization ability also improves significantly; models trained on vast quantities of data are better equipped to handle unseen data and diverse real-world scenarios. However, careful consideration is needed to mitigate issues like overfitting and the high carbon footprint associated with large-scale computations.

ReFT for Diversity#

Reinforced Fine-Tuning (ReFT) for diversity in protein backbone generation is a significant advancement. By aligning a generative model to a reward function that prioritizes structural diversity, ReFT addresses the common issue of generative models producing overly similar outputs. This targeted approach pushes beyond simple unconditional generation, enabling the model to explore a wider range of protein conformations, which is vital for de novo drug design where novelty is crucial. The success of ReFT relies on the careful selection of a relevant reward function accurately reflecting the desired diversity metrics. The strategy directly tackles the limitations of previous methods by actively shaping the generated structures towards increased variety, thereby overcoming limitations of dataset biases. This method leads to a more robust and applicable model, as it creates more designable proteins across various lengths and compositions. Furthermore, the efficacy of this technique is highlighted by the quantitative improvements observed in relevant metrics such as scRMSD and TM-score, demonstrating the practical impact of ReFT in enhancing the diversity of generated protein backbones.

Conditional Design#

The concept of “Conditional Design” in the context of protein backbone generation signifies a significant advance in protein engineering. It moves beyond the limitations of unconditional generative models, which produce proteins randomly, by allowing researchers to specify desired properties. This opens up exciting possibilities for designing proteins with predefined functionalities and specific interactions, such as creating novel drugs or enzymes with tailored characteristics. The conditional aspect allows for incorporating known structural or sequence information as constraints, guiding the generation process towards desired outcomes. This targeted approach drastically reduces the search space, accelerating drug discovery and the design of novel biomolecules. The challenge lies in developing robust and accurate models capable of handling the complexity of protein structure and function while satisfying multiple conditional constraints simultaneously. Successful conditional design requires sophisticated deep learning architectures and large, high-quality datasets to train effective models. The results are promising and demonstrate progress toward more efficient and targeted protein design; however, further refinements are needed to address limitations like generalizability to diverse protein families and the need for computationally efficient algorithms.

More visual insights#

More on figures

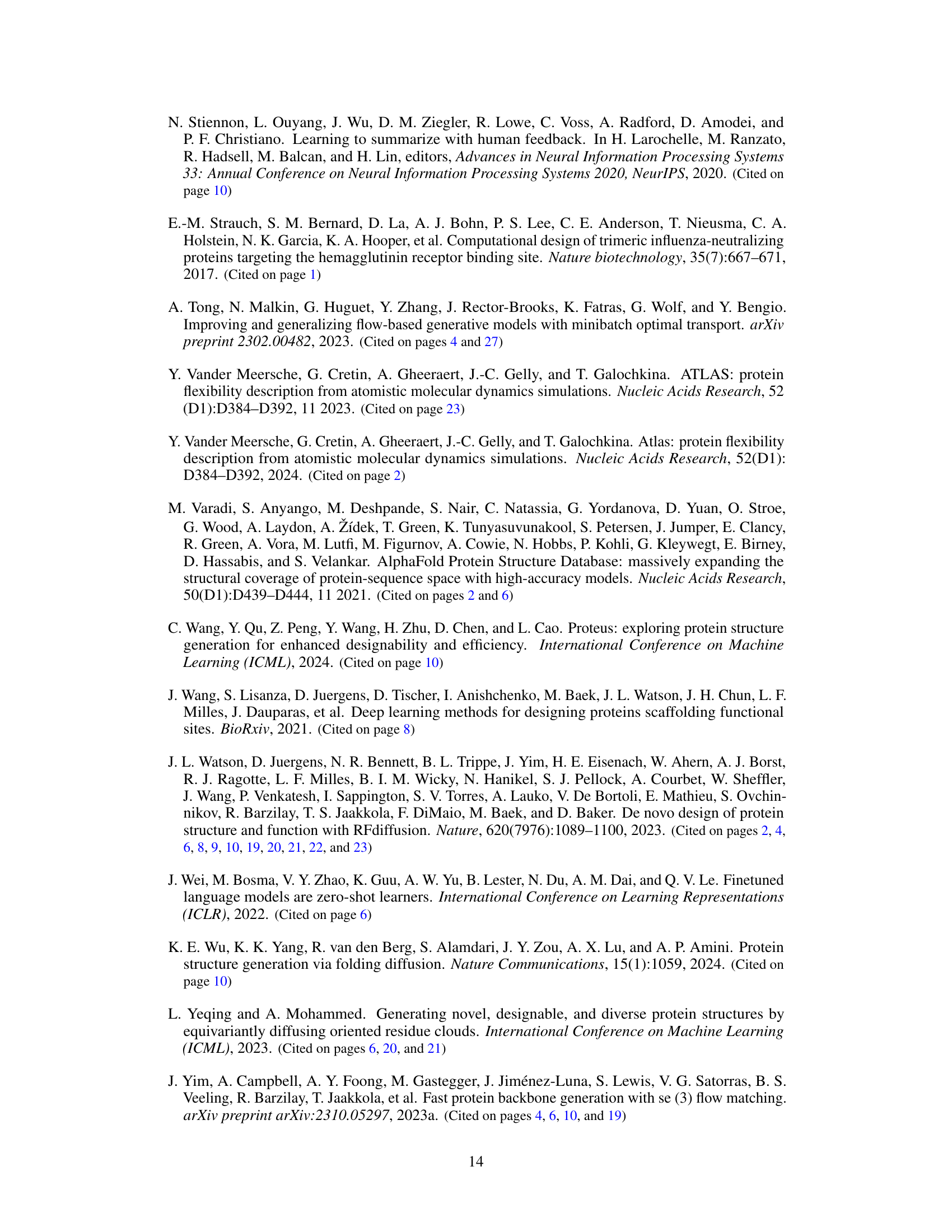

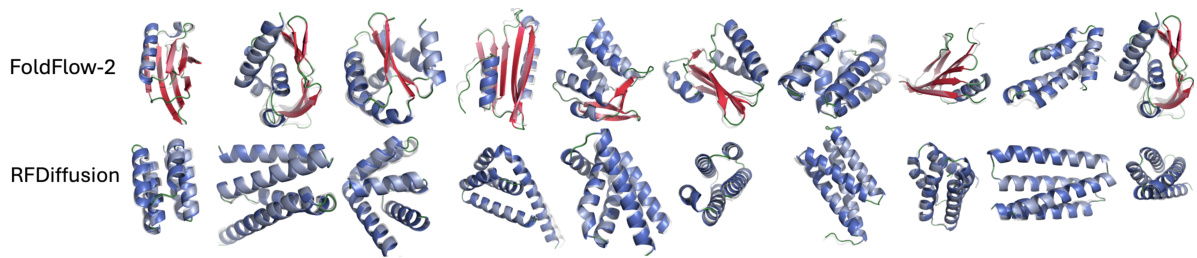

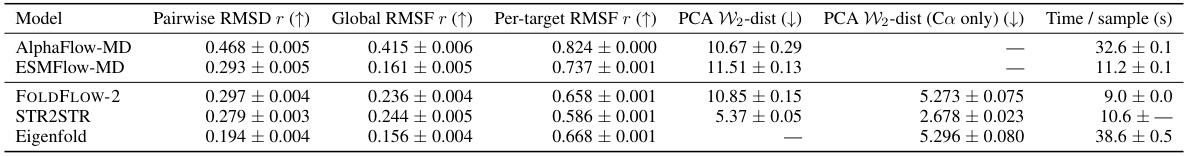

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of protein structures generated by FOLDFLOW-2 and RFDiffusion. Both models generated 100-residue-long protein backbones. The structures are colored according to their secondary structure (alpha-helices, beta-sheets, coils) to highlight the differences in structural diversity. The FOLDFLOW-2 structures exhibit a much wider variety of secondary structure elements compared to RFDiffusion, which produces mostly alpha-helices. This demonstrates FOLDFLOW-2’s superior ability to generate diverse and designable protein structures.

read the caption

Figure 2: Uncurated designable (scRMSD < 2Å) length 100 structures with ESMFold refolded structure from FOLDFLOW-2 and RFDiffusion colored by secondary structure composition where we see RFDiffusion generates mostly α-helices.

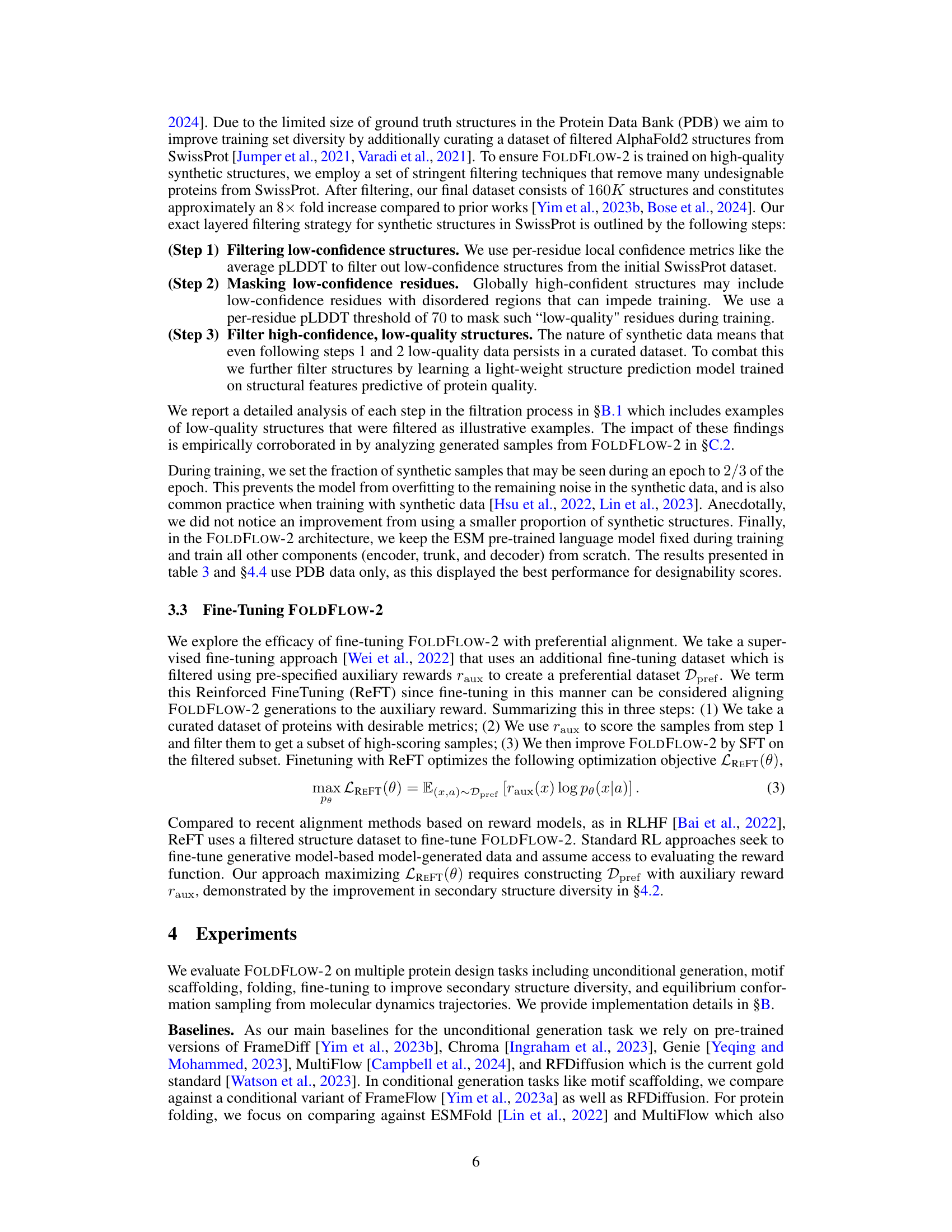

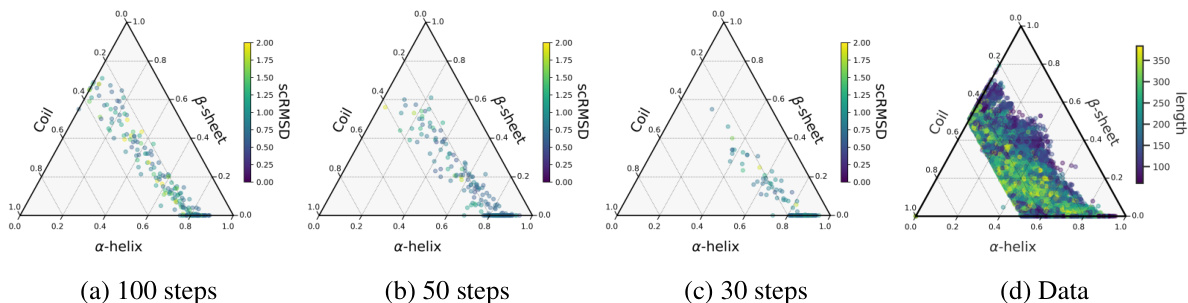

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of secondary structure elements (alpha-helices, beta-sheets, and coils) for designable proteins generated by different models, including FOLDFLOW-2, FOLDFLOW, FrameDiff, and RFDiffusion. Each model’s distribution is visualized as a ternary plot, where the vertices represent the proportion of each secondary structure type. The figure also includes a ternary plot showing the distribution of secondary structure elements in the actual protein data used for training. A bar chart shows the number of beta-sheets generated by each model across various protein lengths. The figure demonstrates that FOLDFLOW-2 generates a much more diverse range of secondary structures compared to the other models, more closely resembling the distribution in the actual protein data.

read the caption

Figure 3: Distribution of secondary structure elements (a-helices, B-sheets, and coils) of designable (scRMSD < 2.0) proteins generated by various models. FOLDFLOW-2 generates more diverse designable backbones.

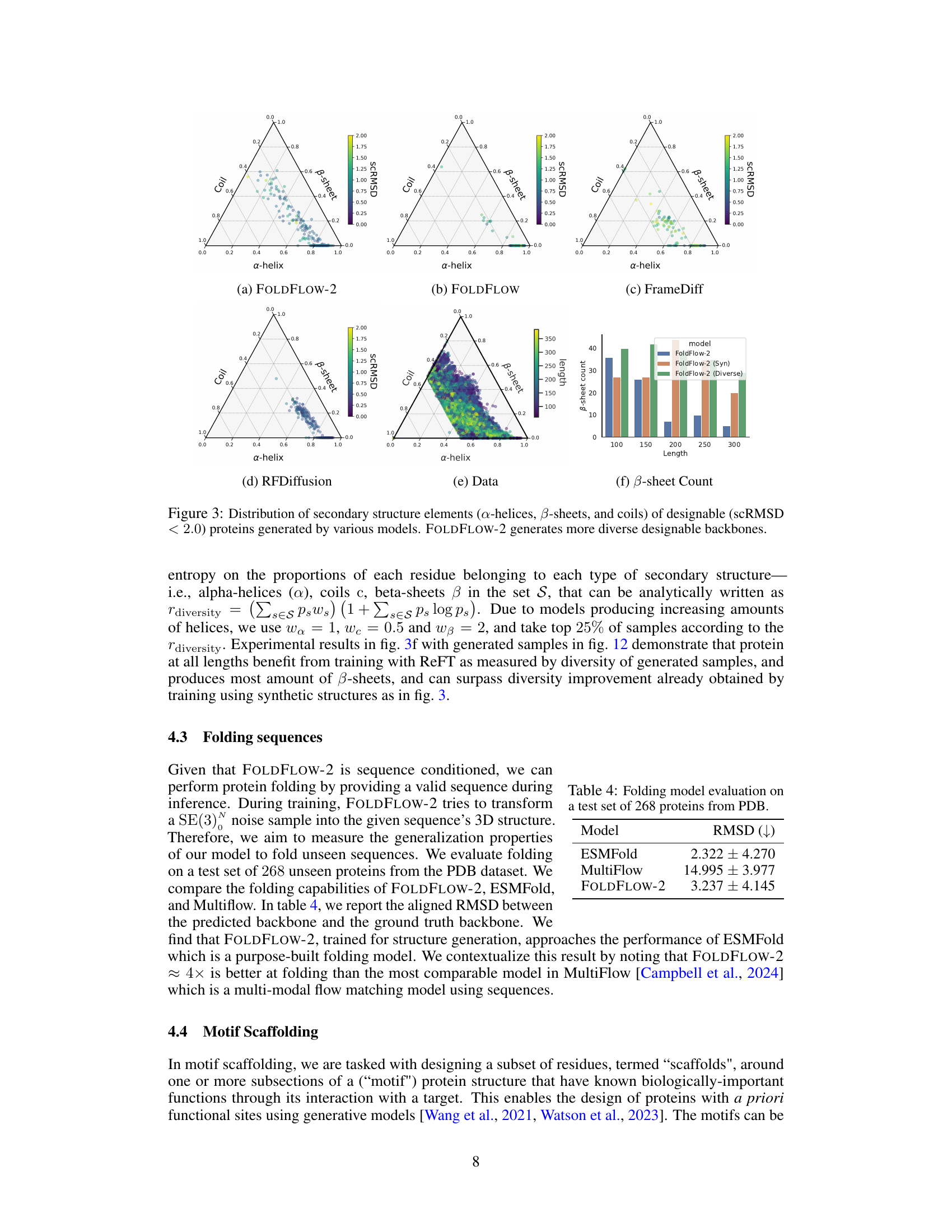

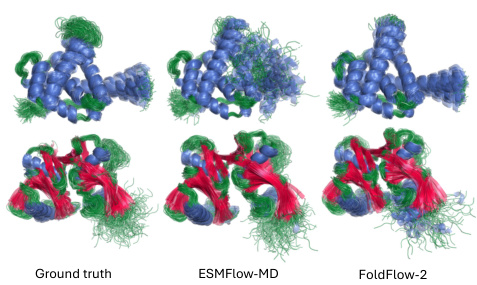

🔼 This figure compares the protein conformation ensembles generated by the FOLDFLOW-2 model against those from ESMFlow-MD and ground truth data from molecular dynamics simulations. The proteins in each column represent the same protein, showcasing the diversity of generated conformations and the model’s ability to capture different protein dynamics compared to ground truth.

read the caption

Figure 10: Additional conformation generation task samples. Proteins are colored by secondary structure with a-helices in blue, B-sheets in red, and loops in green.

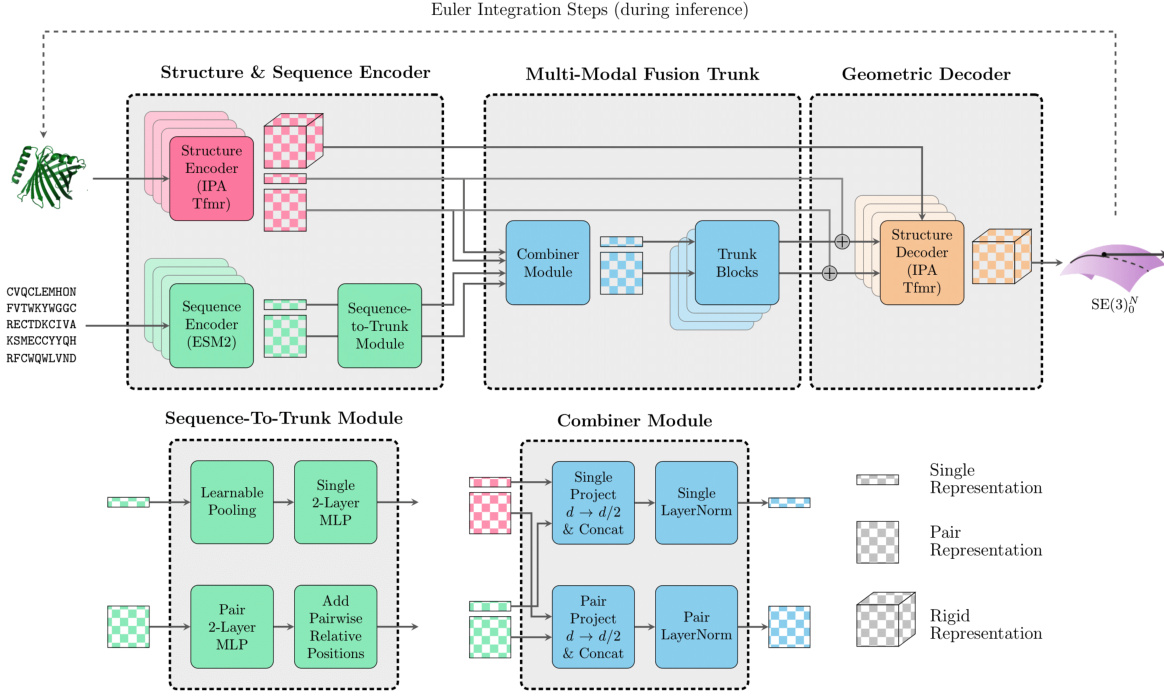

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of global pLDDT values for a sample of 500 proteins from the SwissProt dataset. Panel (a) displays a cumulative histogram of the average pLDDT scores. Panel (b) presents a scatter plot showing the relationship between the average pLDDT score and the standard deviation of pLDDT scores across all residues within each protein. The green box in panel (b) highlights the region where proteins were kept after filtering, indicating a selection of high-confidence proteins with low pLDDT standard deviations.

read the caption

Figure 5: Analysis of global pLDDT distribution on a sample of 500 proteins from SwissProt.

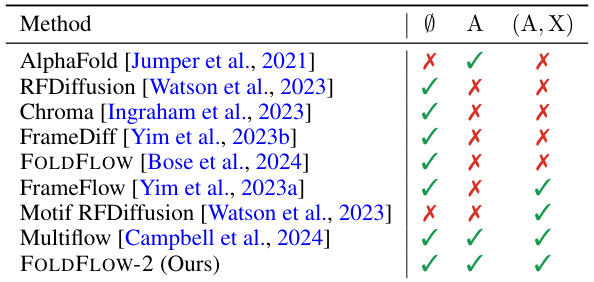

🔼 This figure shows two examples of protein structures that were filtered out from the training dataset due to being of low quality despite having high overall confidence. The structures exhibit unrealistic global structures or sub-chain interactions, which are problematic for training a generative model. The figure highlights the importance of the filtering process in ensuring the quality of the training data.

read the caption

Figure 6: Examples of high-confidence, low-quality structures that were filtered out of the training set. Images are from the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/, accessed in May 2024; identifiers are the UniProt IDs of each example.

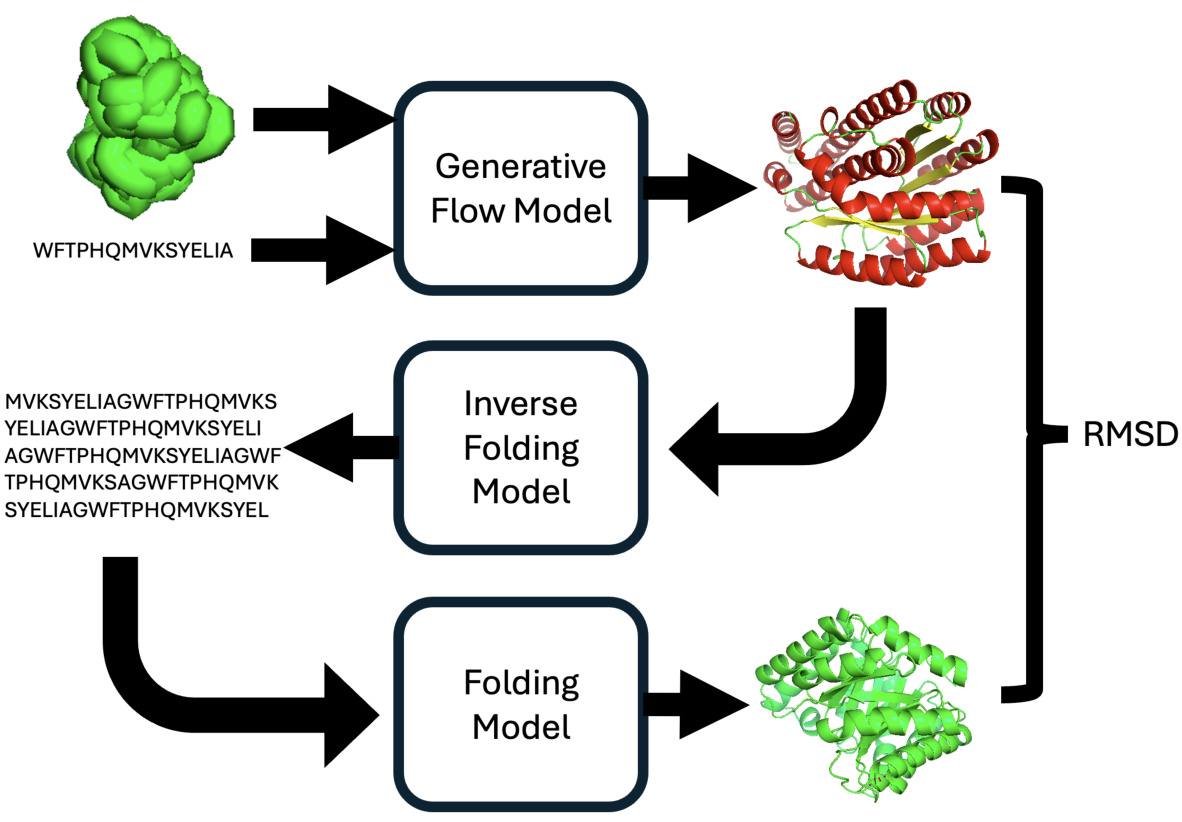

🔼 The figure illustrates the process of calculating protein designability. A generative flow model creates a protein backbone from input data (potentially noise or a protein sequence). This backbone is input into an inverse folding model eight times to generate eight distinct sequences. Each sequence is then folded by ESMFold to produce a structure. Finally, the minimum scRMSD (structure-based root mean square deviation) between the generated and refolded structures is computed and used to determine the designability of the generated structure. A designable structure is one with at least one scRMSD below 2.0Å.

read the caption

Figure 7: Schematic of designability calculation. First a generative flow model is used to generate a protein backbone from an initial structure (possibly noise) and (optionally) a protein sequence. This is then fed to an inverse folding model (ProteinMPNN [Dauparas et al., 2022]) eight times to generate eight sequences for the structure. Then all eight sequences are fed back to ESMFold to produce a structure for each sequence. All eight structures are compared using scRMSD from the ESMFold 'refolded' structure to the generated structure, and the minimum is taken as the “designability” of the generated structure with at least one structure with error < 2.0Å being classified as designable following Watson et al. [2023].

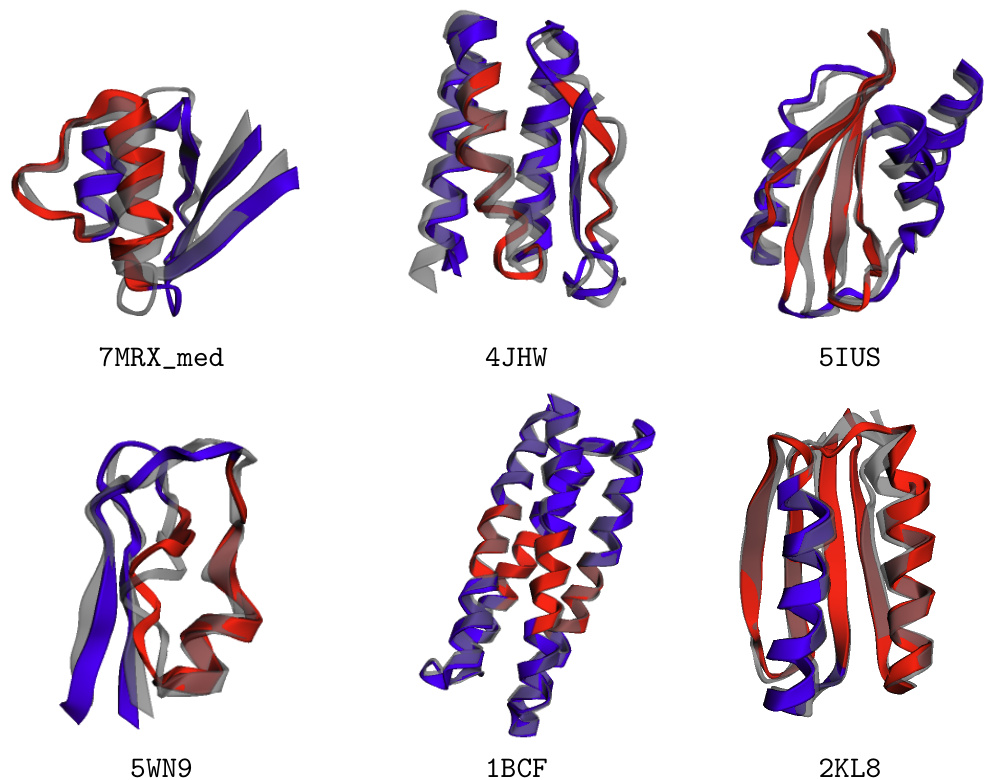

🔼 This figure shows six examples of successful motif scaffolding from the Watson et al. [2023] benchmark. Each example displays the original motif (red), the newly generated scaffold (blue), and the final structure after refolding with ESMFold (gray). The successful integration of the scaffold into the overall protein structure demonstrates the effectiveness of the FOLDFLOW-2 model in this conditional protein design task. The visual representation clearly highlights the designed scaffold’s incorporation into the pre-existing motif.

read the caption

Figure 8: Samples of solved motif scaffolding problems from the benchmark of Watson et al. [2023]. The motif is in red, the designed scaffold is in blue, and the refolded structure from ESMFold is in gray.

🔼 This figure shows four examples of motif scaffolding results using the FOLDFLOW-2 model on VHH nanobodies. In each example, the original motif (CDR, or Complementarity Determining Region) is shown in red, the generated scaffold in blue, and the final structure after refolding with ESMFold is shown in gray. The figure demonstrates the model’s ability to generate diverse and structurally realistic scaffolds for nanobodies.

read the caption

Figure 9: Samples of scaffolds for VHHs. Motif (i.e. CDR) is in red, scaffold is in blue, and refolded structure from ESMFold is in gray.

🔼 This figure compares the results of three different methods for generating protein conformations: ground truth, ESMFlow-MD, and FoldFlow-2. Each method produces multiple conformations for the same protein, which are visually represented using different colors for different secondary structures (a-helices in blue, B-sheets in red, and loops in green). The figure aims to illustrate the differences in the types and diversity of conformations generated by each method.

read the caption

Figure 10: Additional conformation generation task samples. Proteins are colored by secondary structure with a-helices in blue, B-sheets in red, and loops in green.

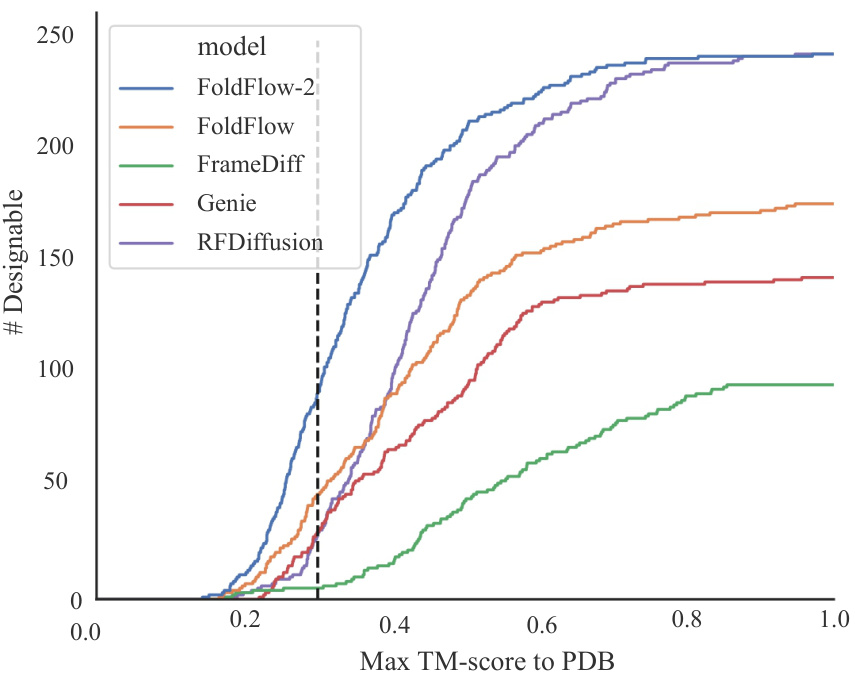

🔼 This figure shows the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the maximum TM-score to the PDB for designable proteins generated by various methods, including FOLDFLOW-2, FoldFlow, FrameDiff, Genie, and RFDiffusion. The x-axis represents the maximum TM-score to the Protein Data Bank (PDB), indicating how similar the generated protein is to known proteins. The y-axis shows the number of designable proteins with a maximum TM-score less than or equal to the x-axis value. The plot demonstrates that FOLDFLOW-2 generates a significantly larger number of designable proteins that are less similar to existing proteins in the PDB compared to other methods, highlighting its ability to produce novel protein structures.

read the caption

Figure 11: Curve showing the number of designable proteins that are at least some distance away from the PDB. FOLDFLOW-2 has many more novel and designable proteins than baselines. We report designability fraction at TM-score = 0.3 in table 3.

🔼 This figure compares designable protein structures generated by different methods, including RFDiffusion and FoldFlow-2 (with and without synthetic data and diversity fine-tuning). The images show that FoldFlow-2 produces more diverse structures, particularly at shorter lengths, demonstrating the effectiveness of its approach and the benefit of incorporating synthetic data and fine-tuning techniques. The silver overlay represents the refolded structures using ESMFold, highlighting the structural similarity.

read the caption

Figure 12: Designable samples from various methods. Overlayed in silver are refolded ESMFold structures. FOLDFLOW-2 exhibits significantly more diversity in secondary structure at shorter lengths than RFDiffusion with fine-tuned models able to produce diverse proteins across lengths.

🔼 This figure compares the distribution of secondary structures (α-helices, β-sheets, and coils) generated by different protein backbone generation models, including FOLDFLOW-2, FOLDFLOW, FrameDiff, and RFDiffusion. It uses ternary plots to visualize the proportions of each secondary structure type in the generated proteins. The goal is to show that FOLDFLOW-2 generates a more diverse set of secondary structures compared to the other models, better reflecting the distribution found in real-world protein data. Designable proteins are defined as those with a structure-based root mean square deviation (scRMSD) less than 2 angstroms compared to the original protein structure.

read the caption

Figure 3: Distribution of secondary structure elements (a-helices, β-sheets, and coils) of designable (scRMSD < 2.0) proteins generated by various models. FOLDFLOW-2 generates more diverse designable backbones.

More on tables

🔼 This table summarizes the different tasks that can be performed by the FOLDFLOW-2 model by manipulating the input modalities (sequence and structure). It shows that the model can perform unconditional generation, protein folding, and in-painting by controlling whether the sequence and/or structure inputs are fully masked, unmasked, or partially masked.

read the caption

Table 2: By manipulating the input modalities, FOLDFLOW-2 is able to perform a diverse set of conditional and unconditional generation tasks including biologically relevant tasks such as designing scaffolds.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of various protein backbone generation models across three key metrics: designability, novelty, and diversity. Designability measures the fraction of generated proteins that can be accurately refolded to their original structures. Novelty assesses how dissimilar the generated proteins are to known proteins in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Diversity measures the variety of structural features among the generated proteins. The table provides quantitative results for each metric along with standard errors for designability and novelty, indicating the statistical significance of the results. It serves as a key benchmark to evaluate the capabilities of FOLDFLOW-2 against state-of-the-art models.

read the caption

Table 3: Comparison of Designability (fraction with scRMSD < 2.0Å), Novelty (max. TM-score to PDB and fraction of proteins with averaged max. TM-score < 0.3 and scRMSD < 2.0Å), and Diversity (avg. pairwise TM-score and MaxCluster fraction). Designability and Novelty metrics include standard errors.

🔼 This table presents the results of protein folding evaluation on a test set of 268 proteins from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Three different models are compared: ESMFold, MultiFlow, and FOLDFLOW-2. The performance is measured using the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) between the predicted and the ground truth backbones. Lower RMSD values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 4: Folding model evaluation on a test set of 268 proteins from PDB.

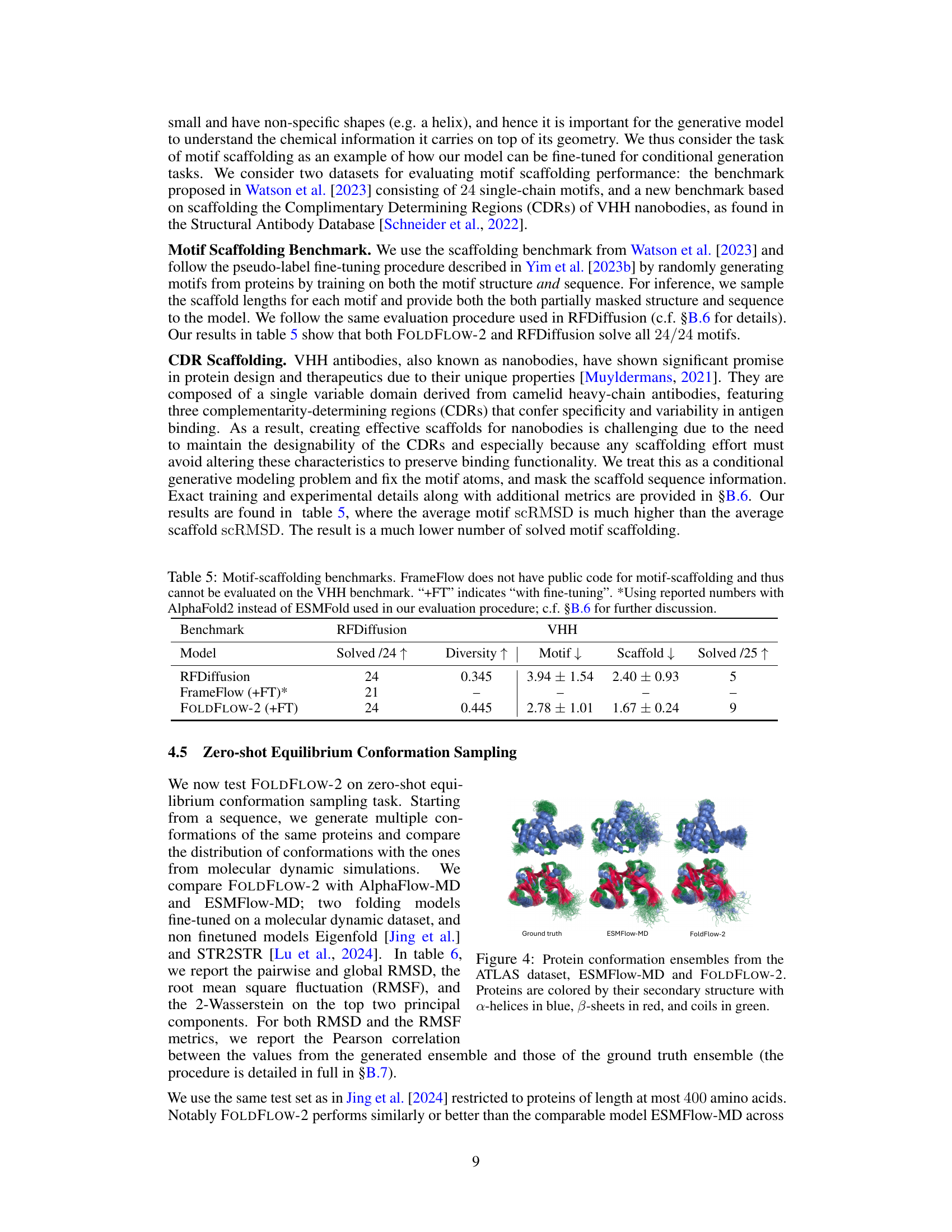

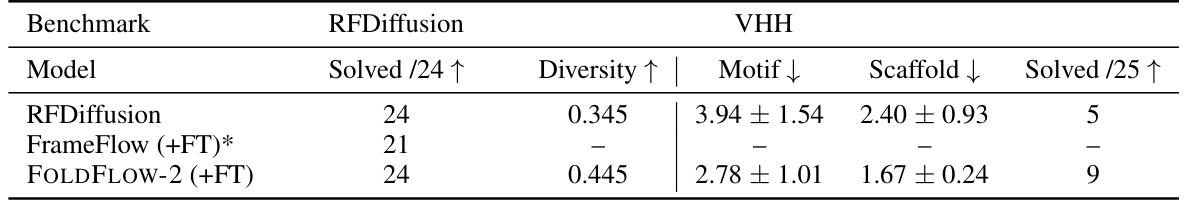

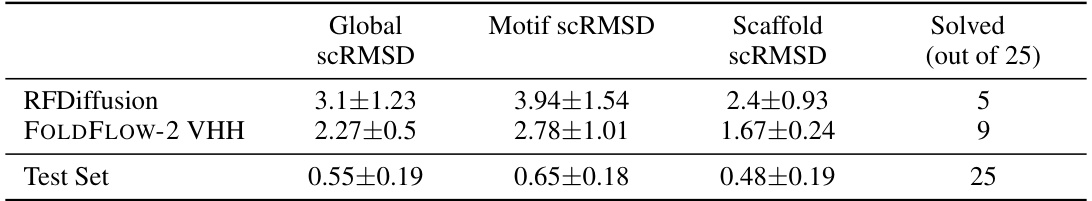

🔼 This table compares the performance of different models on two motif scaffolding benchmarks: one with 24 single-chain motifs and another with VHH nanobodies. The metrics used are the number of solved motifs, diversity, motif scRMSD, scaffold scRMSD, and the number of solved VHH nanobodies. It highlights that FOLDFLOW-2 achieves state-of-the-art results, particularly on the VHH benchmark.

read the caption

Table 5: Motif-scaffolding benchmarks. FrameFlow does not have public code for motif-scaffolding and thus cannot be evaluated on the VHH benchmark. '+FT' indicates 'with fine-tuning'. *Using reported numbers with AlphaFold2 instead of ESMFold used in our evaluation procedure; c.f. §B.6 for further discussion.

🔼 This table compares the performance of FOLDFLOW-2 with other state-of-the-art methods for unconditional protein backbone generation. The metrics used to evaluate the models are designability (the fraction of generated proteins that can be refolded to within a certain RMSD threshold), novelty (how different the generated proteins are from known proteins in the PDB database), and diversity (the variety of structures generated). Standard errors are provided for designability and novelty metrics.

read the caption

Table 3: Comparison of Designability (fraction with scRMSD < 2.0Å), Novelty (max. TM-score to PDB and fraction of proteins with averaged max. TM-score < 0.3 and scRMSD < 2.0Å), and Diversity (avg. pairwise TM-score and MaxCluster fraction). Designability and Novelty metrics include standard errors.

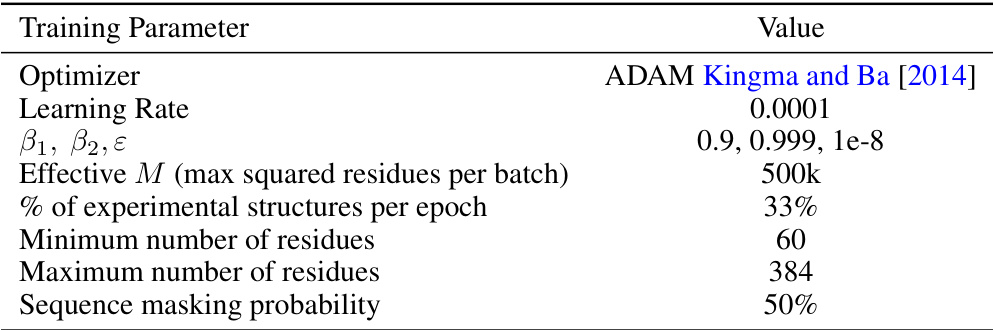

🔼 This table details the hyperparameters used for training the FOLDFLOW-2 model. It includes the optimizer used (ADAM), learning rate, beta parameters for ADAM, the effective batch size (M), the percentage of experimental structures included per epoch, the minimum and maximum number of residues considered, and the probability of masking a sequence during training.

read the caption

Table 7: Overview of Training Setup

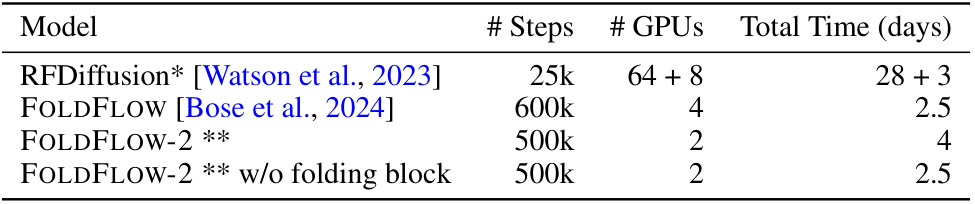

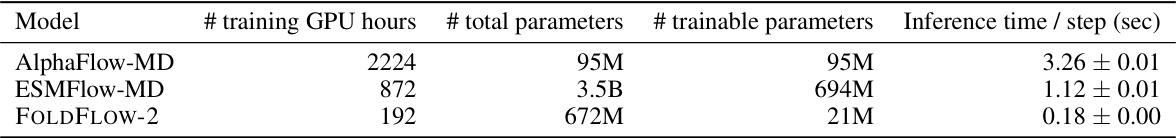

🔼 This table compares the training time and resources for four different protein backbone generation models, including the authors’ proposed model, FOLDFLOW-2. It highlights the computational efficiency gains achieved by FOLDFLOW-2 compared to other models like RFDiffusion, demonstrating a significant reduction in training time and GPU usage.

read the caption

Table 8: An overview of training time. *RFDiffusion initializes from RoseTTAFold, and we include that training time in the estimates. **We recall that FOLDFLOW-2 uses frozen ESM2-650M which was trained on 512 GPUs for 8 days.

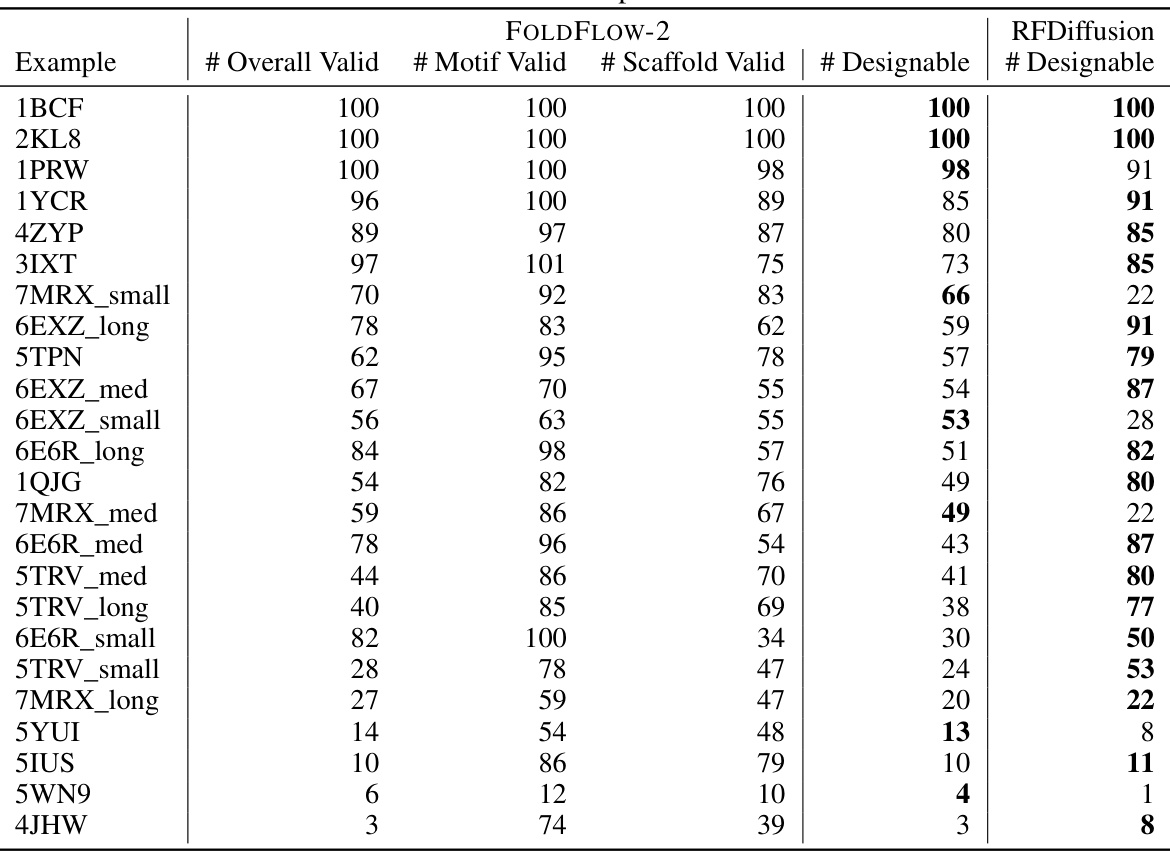

🔼 This table provides a detailed breakdown of the FOLDFLOW-2 model’s performance on the motif scaffolding task. It shows the number of overall valid, motif valid, scaffold valid, and designable structures generated for each of the 24 motif examples in the benchmark dataset, using ESMFold for refolding. The results are presented as counts out of 100 samples for each metric.

read the caption

Table 9: A detailed breakdown of FOLDFLOW-2 motif scaffolding performance using ESMFold to refold all structures. All numbers are out of 100 samples.

🔼 This table presents a detailed breakdown of FOLDFLOW-2’s performance on motif scaffolding for refoldable VHH structures. For each example VHH structure, it shows the number of overall valid samples, the number of motifs that were successfully validated, the number of scaffolds that were valid, the number of designable structures according to the criteria described in the paper, and the number of designable structures produced by RFDiffusion. The table provides a granular view of the success rate of FOLDFLOW-2 on this specific challenging task.

read the caption

Table 10: A detailed breakdown of FOLDFLOW-2 motif scaffolding performance applied to refoldable VHH structures. The same comments as table 9 apply to evaluation. All numbers are out of 25 samples.

🔼 This table presents the results of motif scaffolding experiments on two benchmarks: a standard benchmark with 24 single-chain motifs and a new benchmark based on VHH nanobodies, featuring 25 refoldable motifs. The table compares the performance of RFDiffusion and FOLDFLOW-2, highlighting the number of solved scaffolds, diversity scores, and motif and scaffold scRMSD values. It notes that FrameFlow’s public code does not support motif scaffolding, therefore it is excluded from the VHH benchmark. Important to note that the reported numbers for FrameFlow are obtained using AlphaFold2 results instead of ESMFold, which is the actual model used in the evaluation procedure detailed in the supplementary material (section B.6).

read the caption

Table 5: Motif-scaffolding benchmarks. FrameFlow does not have public code for motif-scaffolding and thus cannot be evaluated on the VHH benchmark. '+FT' indicates 'with fine-tuning'. *Using reported numbers with AlphaFold2 instead of ESMFold used in our evaluation procedure; c.f. §B.6 for further discussion.

🔼 This table shows the performance of RFDiffusion and FOLDFLOW-2 VHH on the VHH motif scaffolding benchmark, including global, motif, and scaffold scRMSD and the number of solved motifs (out of 106). The test set provides a baseline of expected performance on this task.

read the caption

Table 12: VHH Motif Scaffolding results on all samples, same numbers as table 11

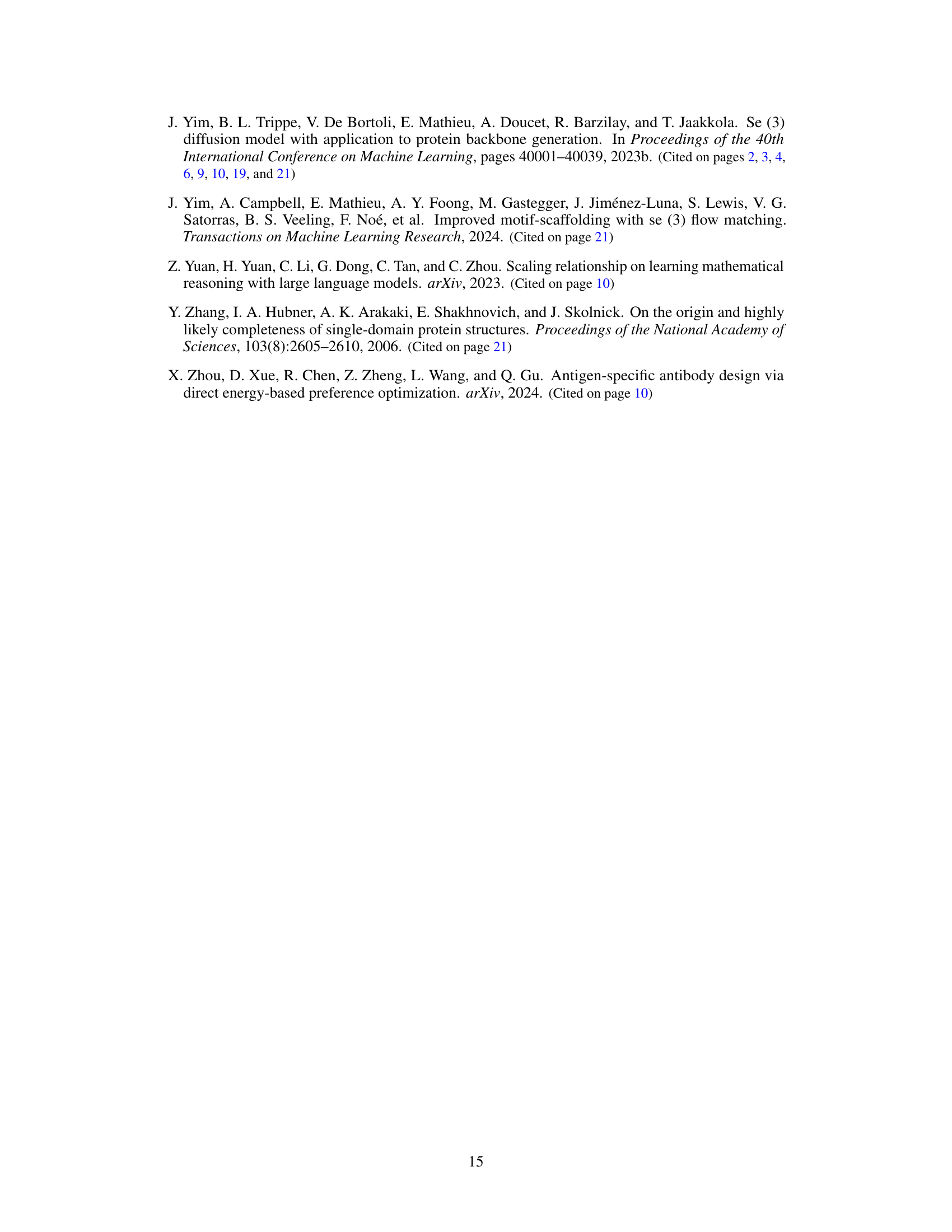

🔼 This table compares the training time (in GPU hours), total number of parameters, number of trainable parameters, and inference time per step for three different models: AlphaFlow-MD, ESMFlow-MD, and FOLDFLOW-2. It highlights that FOLDFLOW-2 is significantly more efficient in terms of training time and model size while maintaining competitive inference speed.

read the caption

Table 13: Molecular dynamics experiment training details.

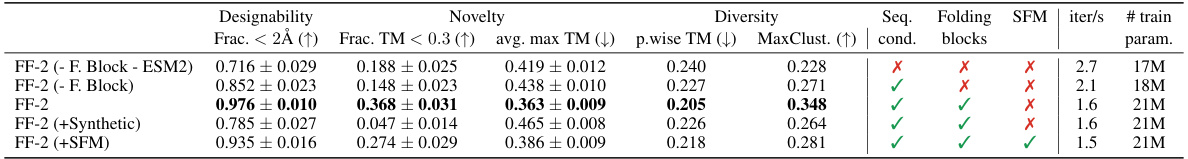

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study on the FOLDFLOW-2 model. It examines the impact of several architectural components and training strategies on the model’s performance in terms of designability, novelty, and diversity of generated protein structures. Specifically, it compares the full FOLDFLOW-2 model against versions where the folding blocks are removed or replaced with simpler MLPs, sequence conditioning is removed, synthetic data is added to the training set, or stochastic flow matching is used. The metrics used to evaluate the models are the fraction of generated proteins with a structural RMSD (scRMSD) below 2Å, the average maximum TM-score to proteins in the PDB dataset (a measure of novelty), and the average pairwise TM-score and the maximum number of clusters among the generated proteins (both measures of diversity).

read the caption

Table 14: Ablation study on FOLDFLOW-2 (FF-2) using: synthetic data, folding blocks, and stochastic flow matching (SFM). We generated 250 proteins (50 of length 100, 150, 200, 250) and compared Designability (fraction with scRMSD < 2.0Å), Novelty (max. TM-score to PDB and fraction of proteins with averaged max. TMscore < 0.3 and scRMSD < 2.0Å), and Diversity (avg. pairwise TMscore and MaxCluster fraction).

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study on the inference annealing functions used in the FOLDFLOW-2 model. It compares the performance of the model across different annealing functions (1, 2t, 5t, 10t, 15t, 20t), evaluating the designability, novelty, and diversity of the generated protein structures using several metrics. The results highlight the impact of the annealing schedule on the quality and diversity of the generated protein structures.

read the caption

Table 15: Comparison of Designability (fraction with scRMSD < 2.0Å), Novelty (max. TM-score to PDB and fraction of proteins with averaged max. TMscore < 0.3 and scRMSD < 2.0Å), and Diversity (avg. pairwise TMscore and MaxCluster fraction) for different inference annealing functions i(t).

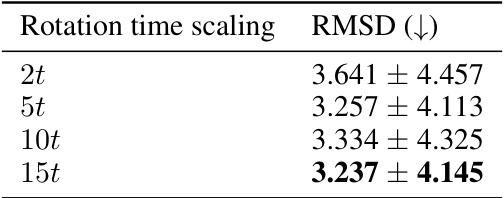

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the impact of rotation time scaling on the root mean square deviation (RMSD) of protein backbone generation. It shows the RMSD values obtained using different rotation time scaling factors (2t, 5t, 10t, and 15t) during the integration process. The lower the RMSD, the better the generated protein structure aligns with the ground truth, indicating improved folding performance. The experiment used 278 test samples, and the mean and standard deviation are reported for each scaling factor.

read the caption

Table 16: Speed of the integration on rotations. Integrating with a faster time for rotations compared to translation leads to more designable structures. Reporting the mean ± std. on 278 test samples.

🔼 This table compares the performance of FOLDFLOW-2 and several other methods on three key metrics: designability, novelty, and diversity. Designability measures the fraction of generated proteins that can be successfully refolded to their original structure. Novelty assesses how different the generated proteins are from those in the PDB database. Diversity quantifies how varied the set of generated proteins are. Standard errors are included for designability and novelty.

read the caption

Table 3: Comparison of Designability (fraction with scRMSD < 2.0Å), Novelty (max. TM-score to PDB and fraction of proteins with averaged max. TM-score < 0.3 and scRMSD < 2.0Å), and Diversity (avg. pairwise TM-score and MaxCluster fraction). Designability and Novelty metrics include standard errors.

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the impact of varying the number of Euler integration steps during the protein folding process on the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD). The RMSD measures the difference between the generated protein backbone structure and the ground truth structure. Lower RMSD values indicate better accuracy in the folding process. The table shows that using 50 Euler steps results in the lowest average RMSD, suggesting this is the optimal number of steps for this specific task. The standard deviation is also provided to show the variability of the results.

read the caption

Table 18: Effect of the number of integration steps on the aligned RMSD between the generated and ground truth backbone. Reporting the mean ± std. on 278 test samples.

Full paper#