↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current LLM evaluation methods often employ Elo rating systems, borrowed from competitive games. However, LLMs possess static capabilities unlike dynamic game players, raising concerns about Elo’s suitability. This paper investigates two key axioms: reliability and transitivity, revealing that Elo ratings for LLMs are highly sensitive to the order of comparisons and hyperparameter choices, often failing to satisfy these axioms.

This research uses both simulated and real-world data to analyze Elo’s performance. Synthetic data, modeled on Bernoulli processes, helps isolate factors affecting reliability, while real-world human feedback data validates the findings. The study’s main contribution is identifying these limitations and providing concrete guidelines for improving Elo’s reliability, such as increasing the number of comparisons and carefully selecting hyperparameters. This work promotes more robust and trustworthy LLM evaluation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with Large Language Models (LLMs). It challenges the common practice of using Elo ratings for LLM evaluation, highlighting their unreliability and lack of transitivity. The provided guidelines for improving LLM evaluation methods are essential for more robust and accurate assessments.

Visual Insights#

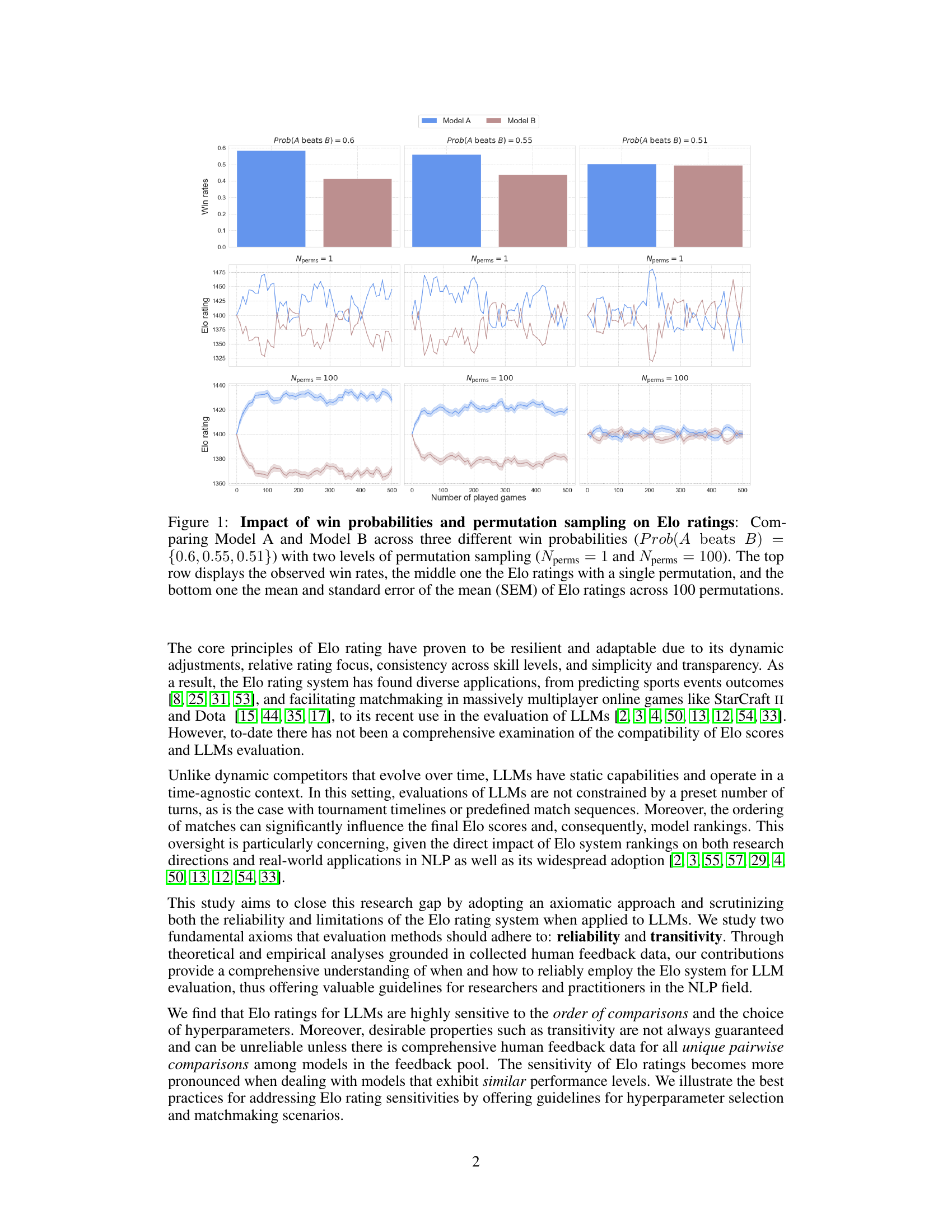

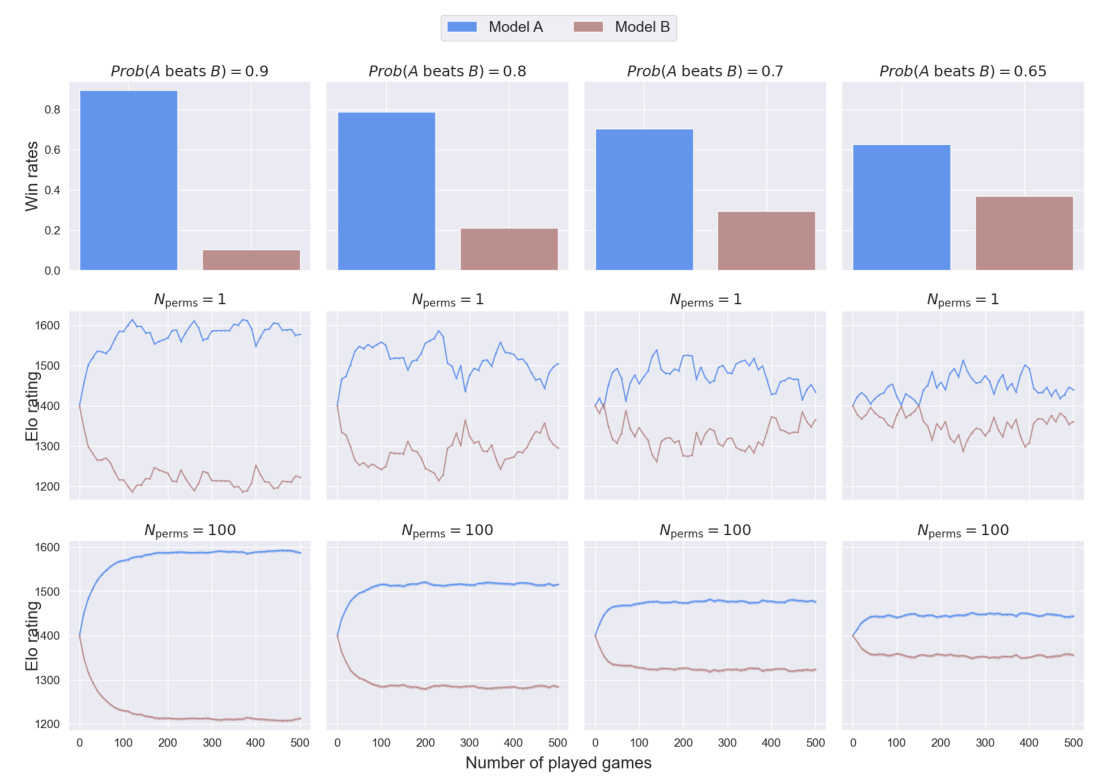

This figure shows how Elo ratings change based on different win probabilities and the number of permutations used. It demonstrates the impact of randomness on the Elo system, especially when win probabilities are close to 50%. The top row shows the actual win rates; the middle row shows Elo ratings calculated using only one permutation of the matches (illustrating volatility); the bottom row shows the average Elo ratings across 100 different permutations, highlighting improved stability and reduced volatility with more permutations.

This table presents the results of an experiment designed to test the reliability and transitivity of Elo ratings for comparing language models. Four different scenarios were set up, each with three models (A, B, C) and varying win probabilities. The table shows the Elo scores for each model under different conditions (N=1, K=1; N=100, K=1; N=1, K=16; N=100, K=16), where N represents the number of permutations of comparisons and K is the K-factor in the Elo algorithm. The star (*) indicates scenarios where Elo failed to produce a transitive ranking; ≈ denotes scenarios where the models have similar performances, and ≫ indicates clear differences in model performance.

In-depth insights#

Elo’s LLM Limits#

The heading “Elo’s LLM Limits” aptly encapsulates the core argument of a research paper analyzing the suitability of the Elo rating system for evaluating Large Language Models (LLMs). The Elo system, while effective in dynamic games like chess, faces challenges when applied to static entities like LLMs. The paper likely explores the limitations of Elo’s inherent assumptions, specifically its reliance on transitivity and reliability, in the context of LLM evaluation. Transitivity, the assumption that if A beats B and B beats C, then A should beat C, may not hold consistently for LLMs due to varying strengths and weaknesses across different tasks. Similarly, reliability is challenged, as Elo ratings can fluctuate significantly based on the order of comparisons and the choice of hyperparameters (K-factor). The paper would likely support these arguments with empirical evidence demonstrating the inconsistencies and instability of Elo-based LLM rankings, suggesting that alternative or supplementary evaluation methods are needed for a more robust and accurate assessment of LLM capabilities. Ultimately, “Elo’s LLM Limits” highlights the critical need for a thoughtful examination of existing evaluation methods before widespread adoption.

Robustness of Elo#

The robustness of Elo ratings in evaluating LLMs is a central theme, challenged by the inherent static nature of LLMs, unlike dynamic game players. The study reveals that Elo’s reliability is compromised by its sensitivity to the order of comparisons, and the choice of hyperparameters (especially the K-factor), violating the axioms of reliability and transitivity, particularly when model performance is similar. This inconsistency in rankings necessitates a reassessment of using Elo for LLM evaluation. The research highlights the need for more robust methods that account for the ordering of comparisons and hyperparameter tuning, and suggests using a larger number of permutations to achieve stable Elo scores. The findings emphasize the importance of empirical validation and careful hyperparameter selection to ensure reliable and meaningful LLM ranking, highlighting the limitations of directly applying Elo without careful consideration of LLM-specific characteristics.

Synthetic Feedback#

The section on ‘Synthetic Feedback’ is crucial because it addresses the inherent challenges of obtaining and managing large-scale human feedback for evaluating LLMs. Human feedback is expensive and time-consuming, making it difficult to create comprehensive evaluations across many models and prompts. Synthetic feedback offers a scalable solution by simulating human preferences through computationally efficient methods. The authors likely leverage a Bernoulli process or similar probabilistic approach to generate synthetic data, mimicking the binary nature of human preferences (preferring one LLM response over another). This allows for controlled experiments exploring the sensitivity of Elo ranking to various factors such as win probabilities and match-up sequences. The use of synthetic data provides a more systematic and controlled testing environment than reliance on human feedback alone. However, limitations must be acknowledged. Synthetic data cannot perfectly replicate the complexities of human judgment, potentially leading to oversimplification. The authors likely address this by comparing the findings from synthetic data to real-world human feedback, validating and characterizing the effectiveness of Elo in evaluating LLMs under real-world conditions and highlighting the strengths and limitations of each approach.

Real-World Tests#

In the realm of evaluating large language models (LLMs), the transition from synthetic to real-world testing is critical. Real-world tests present a more accurate reflection of LLM performance in actual applications, exposing nuances and limitations not apparent in simulated environments. This involves human evaluation of LLM outputs on real-world tasks and prompts, introducing crucial aspects such as subjective judgment and variability among human raters. The choice of real-world dataset is crucial, as it directly impacts the validity and generalizability of the evaluation. Carefully selected datasets, encompassing diverse and realistic tasks, are essential for robust findings. Real-world tests also necessitate a thorough examination of the evaluation metrics used. Human feedback, often incorporated in real-world evaluations, introduces more subjectivity than automated methods, requiring a careful approach to analysis and interpretation of results. Overall, real-world testing provides a more holistic and practical assessment of LLM capabilities and potential limitations, leading to more informed development and deployment strategies.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending the Elo system to handle multiple outcomes beyond binary win/loss scenarios, such as incorporating ties or nuanced performance levels. A more robust Elo system could also incorporate uncertainty quantification, perhaps through Bayesian methods, thus providing more reliable confidence intervals around Elo scores and model rankings. Investigating the impact of different human evaluation methodologies on Elo score stability and exploring alternative ranking systems, potentially inspired by collaborative filtering or network ranking techniques, are other fruitful directions. Furthermore, exploring the sensitivity of Elo scores to specific prompt types or model strengths and weaknesses, as well as examining the interaction effects of these factors, is critical for practical applications. Finally, the scalability and efficiency of current comparative evaluation techniques should be assessed, including exploring more cost-effective and less time-consuming approaches to handle the exponentially increasing number of models.

More visual insights#

More on figures

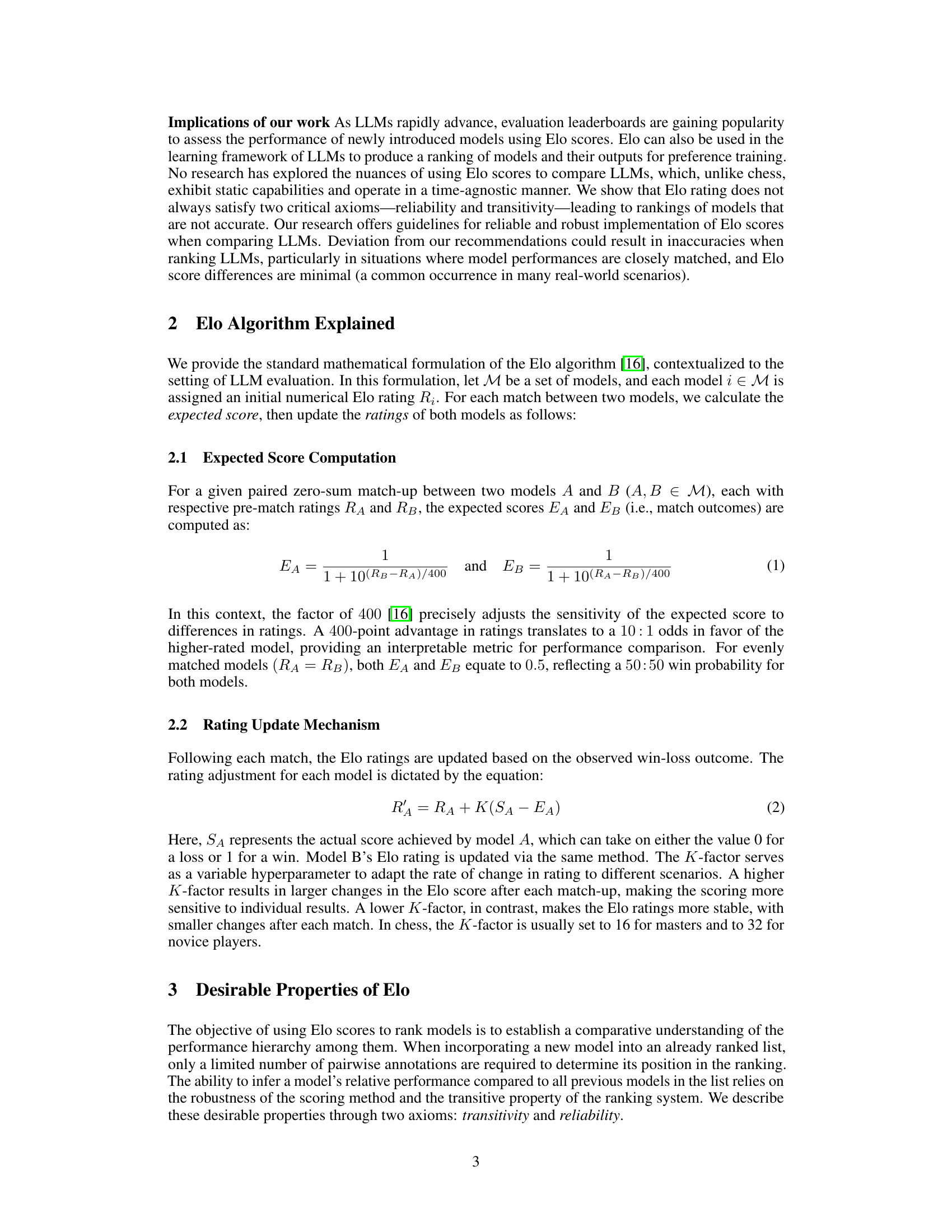

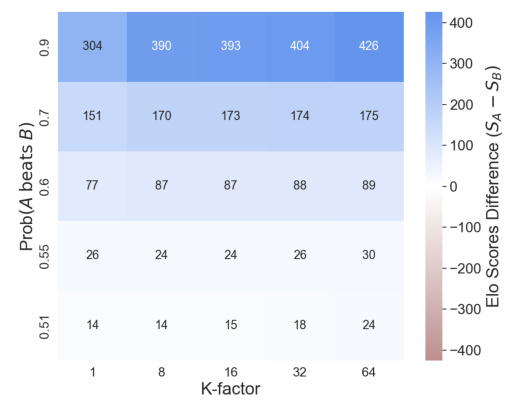

This figure shows the impact of K-factor and the number of permutations (Nperms) on the difference in Elo scores between two models (Model A and Model B). The heatmap displays the Elo score difference (SA - SB) for various combinations of K-factor and win probabilities. Positive values indicate that Model A consistently outperforms Model B, while negative values show discrepancies where Model B gets a higher Elo score than expected. Comparing single sequences versus averages across multiple permutations (Nperms=100) highlights the influence of sequence ordering on Elo score reliability.

This figure shows the impact of the K-factor and the number of permutations (Nperms) on the Elo score difference between two models (Model A and Model B). The heatmap displays the Elo score difference (SA-SB) for various combinations of K-factor and winning probabilities. Positive values indicate that Model A is correctly ranked higher than Model B, while negative values show an incorrect ranking where Model B is ranked higher. The figure compares the results from a single sequence of matches (Nperms = 1) with the average Elo scores across 100 permutations (Nperms = 100). This highlights the effect of the ordering of matches on the final Elo scores.

This figure shows how Model A’s average Elo score changes as the number of permutations (Nperms) increases, for various win probabilities. The x-axis represents the number of permutations, while the y-axis shows the Elo score. Different colored lines represent different probabilities of Model A winning a single match against Model B. The error bars illustrate the variability of the Elo score across multiple runs with the same number of permutations.

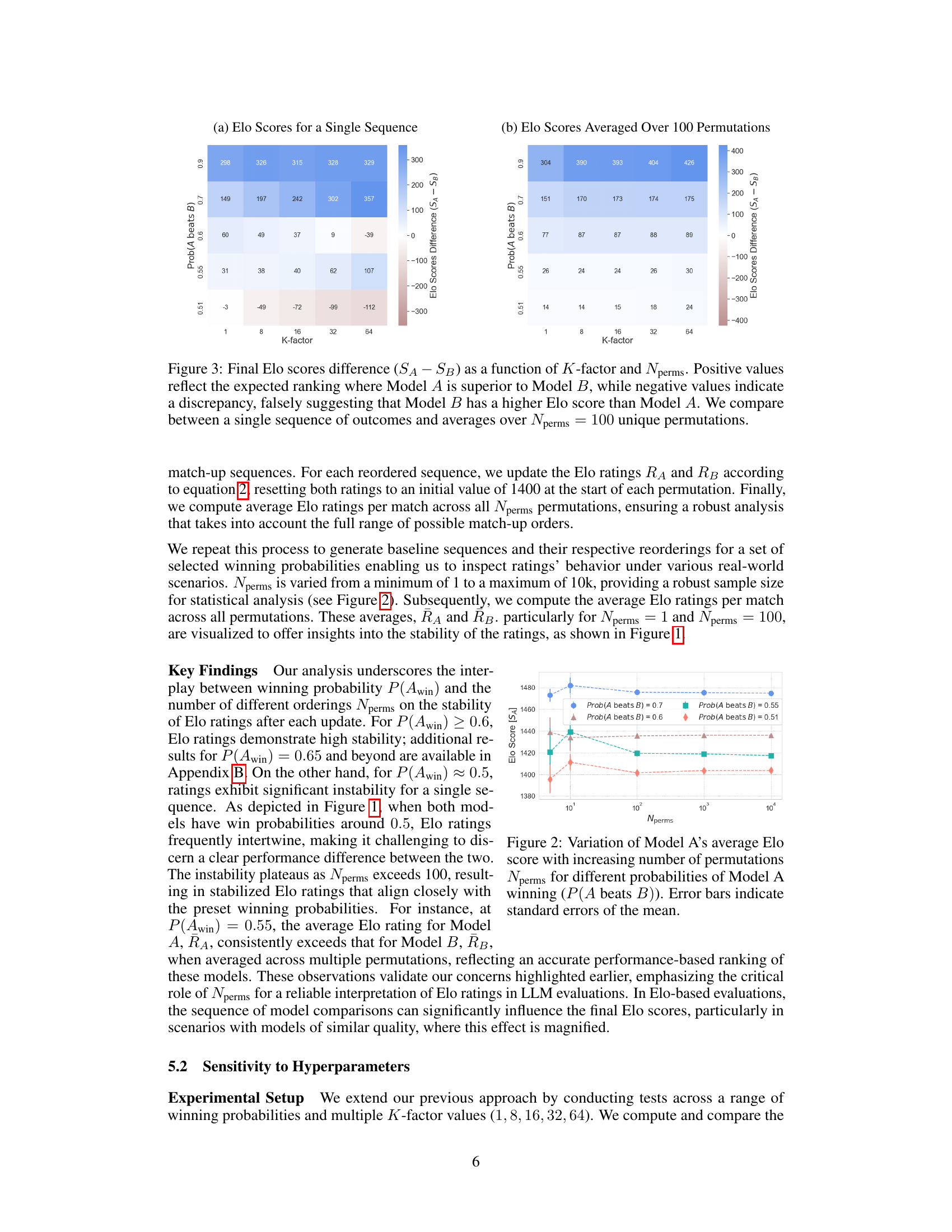

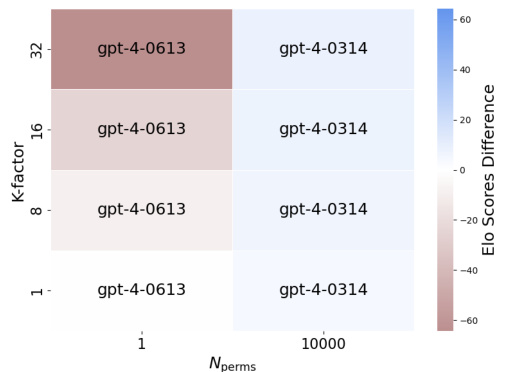

This figure shows the results of an experiment comparing Elo score differences (SA-SB) under different hyperparameter settings (K-factor and Nperms). The heatmap visually represents the difference in Elo scores between two models (A and B). Positive values show Model A consistently outperforming Model B, matching the expected outcome. Negative values indicate that Model B has a higher Elo score than Model A, which contradicts the observed win rates. The labels within the heatmap cells show which model has the higher Elo score in that specific K-factor and Nperms setting.

This figure displays the impact of K-factor and the number of permutations (Nperms) on the difference in Elo scores between two models (Model A and Model B). The heatmap shows the Elo score difference (SA - SB) calculated for different values of K-factor and Nperms. Positive values indicate Model A has a higher Elo score (as expected), while negative values show an unexpected ranking where Model B is considered higher. The figure compares results for a single sequence of matches and averages over multiple (100) permutations, highlighting the effects of sequence ordering on Elo score reliability.

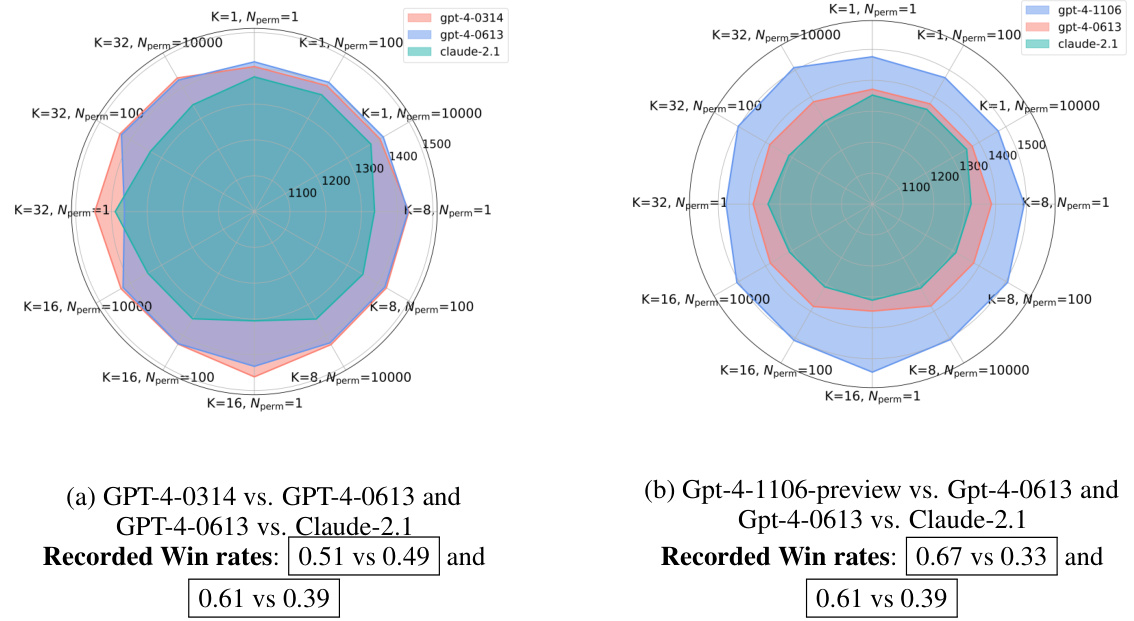

This figure shows the Elo scores for three different models under various configurations of hyperparameters (Nperms and K-factor) and win rates. Panel (a) displays less stable rankings for models with similar performance levels, while panel (b) demonstrates more stable rankings when win rates are skewed, indicating higher performance differences between models. This visualization helps to illustrate the sensitivity of Elo to these factors.

This figure shows the impact of win probabilities and permutation sampling on Elo ratings for two models (A and B) across four different win probabilities: 0.9, 0.8, 0.7, and 0.65. It compares the Elo ratings obtained with a single permutation (Nperms = 1) against those obtained by averaging across 100 permutations (Nperms = 100). The top row shows the observed win rates for each condition. The middle row displays the Elo rating trajectories for a single permutation run. The bottom row shows the average Elo ratings and their standard errors across the 100 permutations, providing a clearer picture of the stability and reliability of the Elo ratings in each scenario.

This figure shows how Elo ratings for two models (A and B) change based on their win probabilities and the number of times their matches are randomly reordered. The top row shows the actual win rates between the models for different probabilities of model A winning. The middle row shows the Elo ratings calculated for each model using a single, fixed order of matches. The bottom row displays the mean Elo ratings (average over 100 random match orderings) along with standard error bars showing the variability of Elo ratings due to the order of the match ups. This illustrates the sensitivity of Elo ratings to random match orderings, especially when models have very similar skill levels.

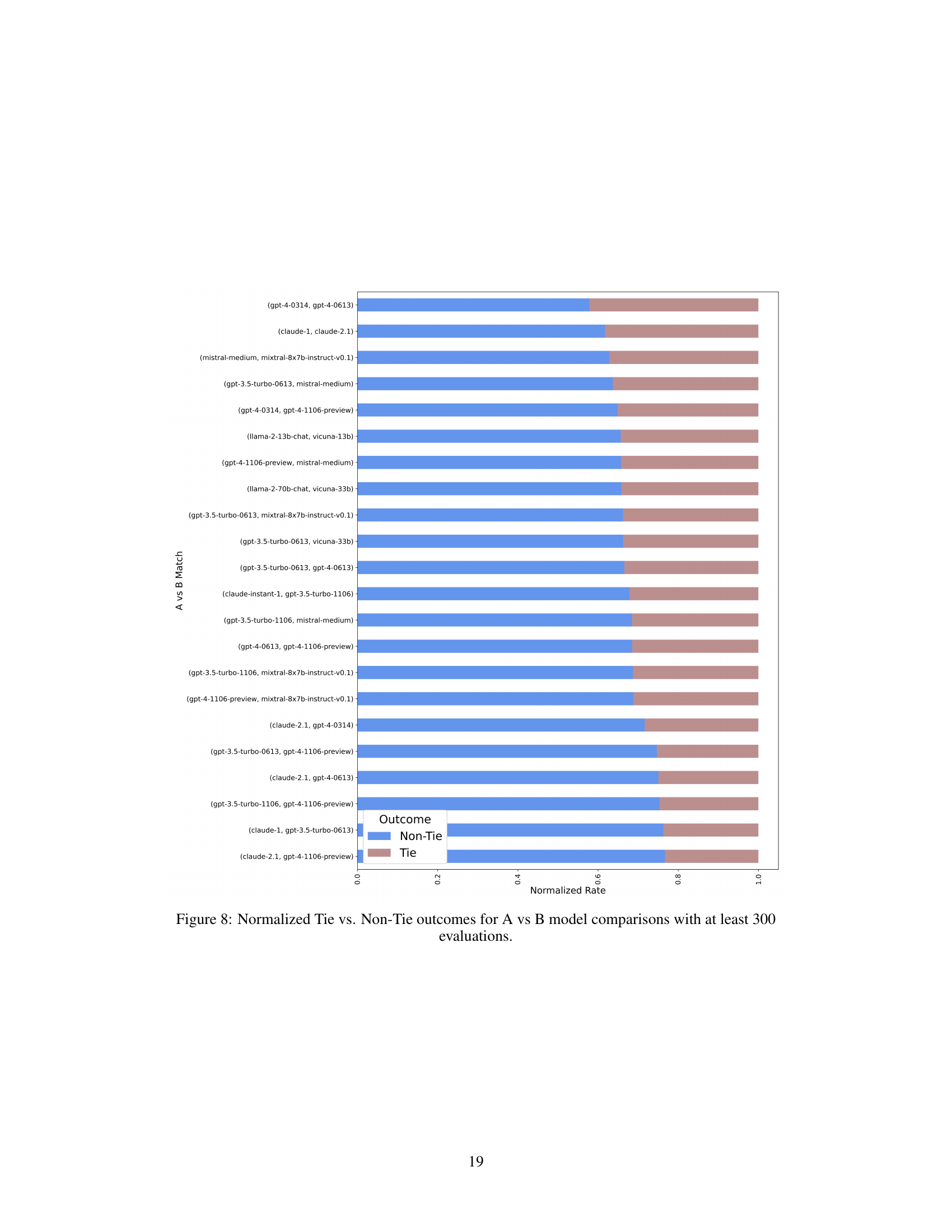

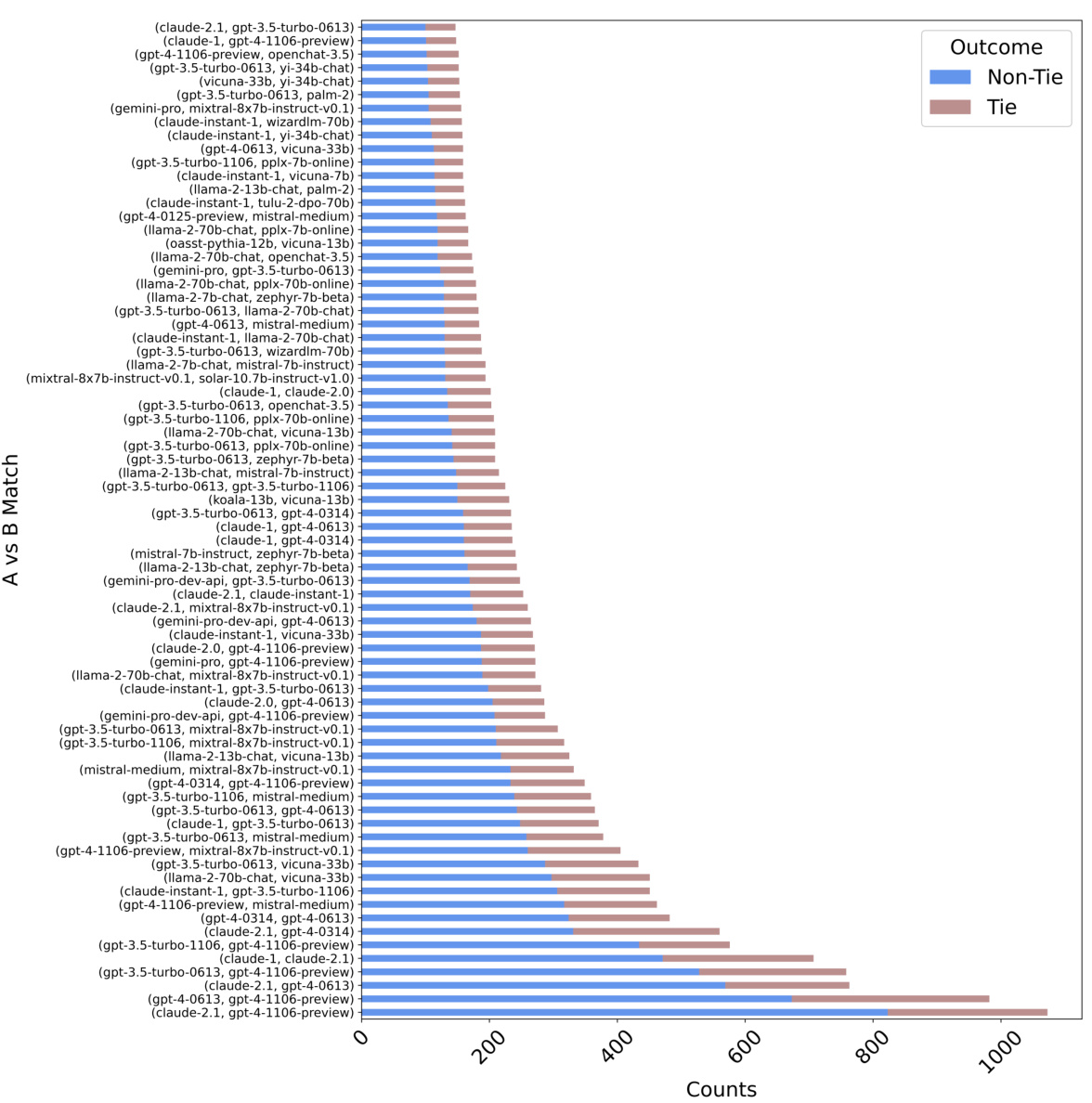

This figure shows the normalized distribution of tie and non-tie outcomes for various pairs of language models from the LMSYS dataset, each pair having at least 300 evaluations. The x-axis lists the pairs of models and the y-axis represents the normalized proportion of each outcome. The bars are color-coded to distinguish between tie (brown) and non-tie (blue) outcomes. The figure provides a visual representation of the relative frequency of ties versus non-ties for different model comparisons in the dataset.

More on tables

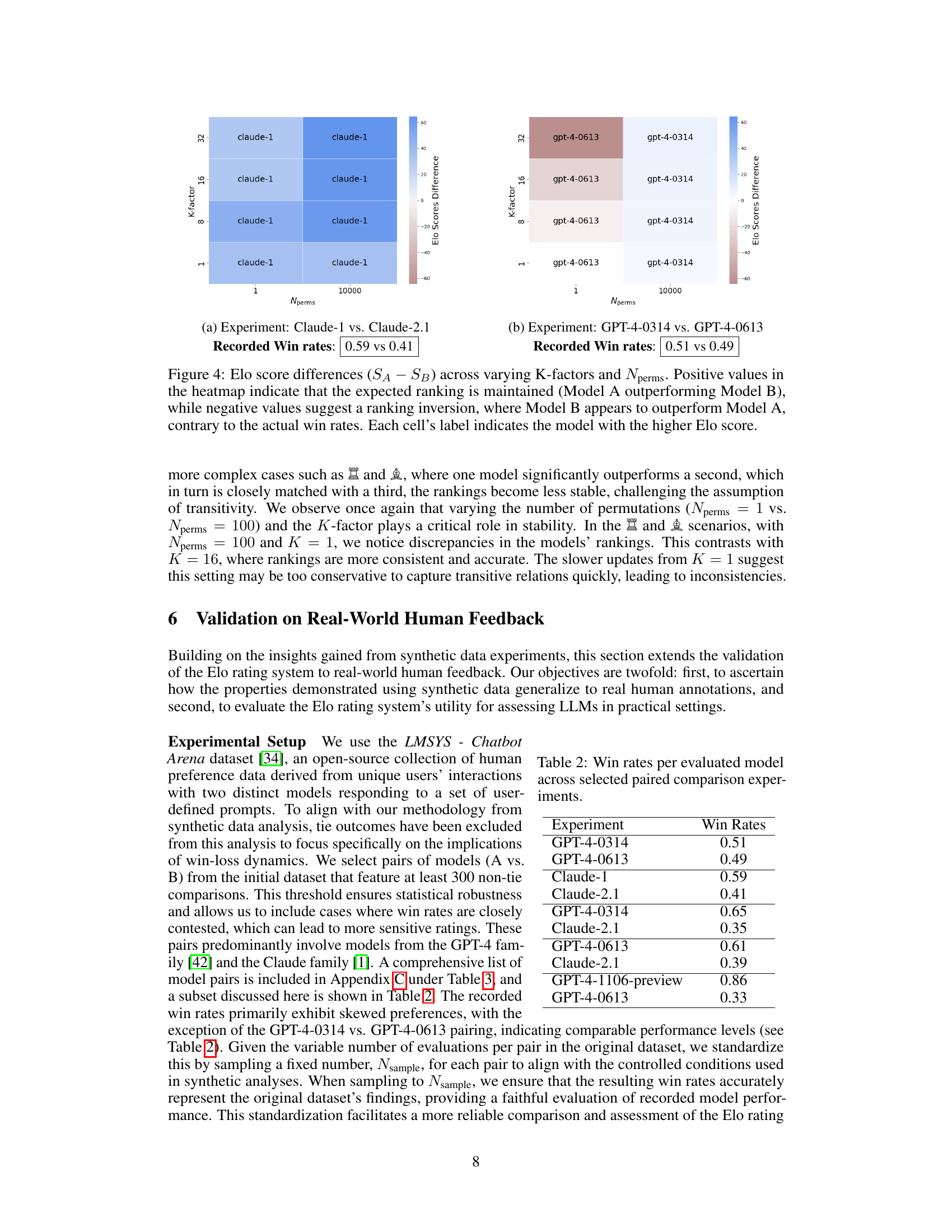

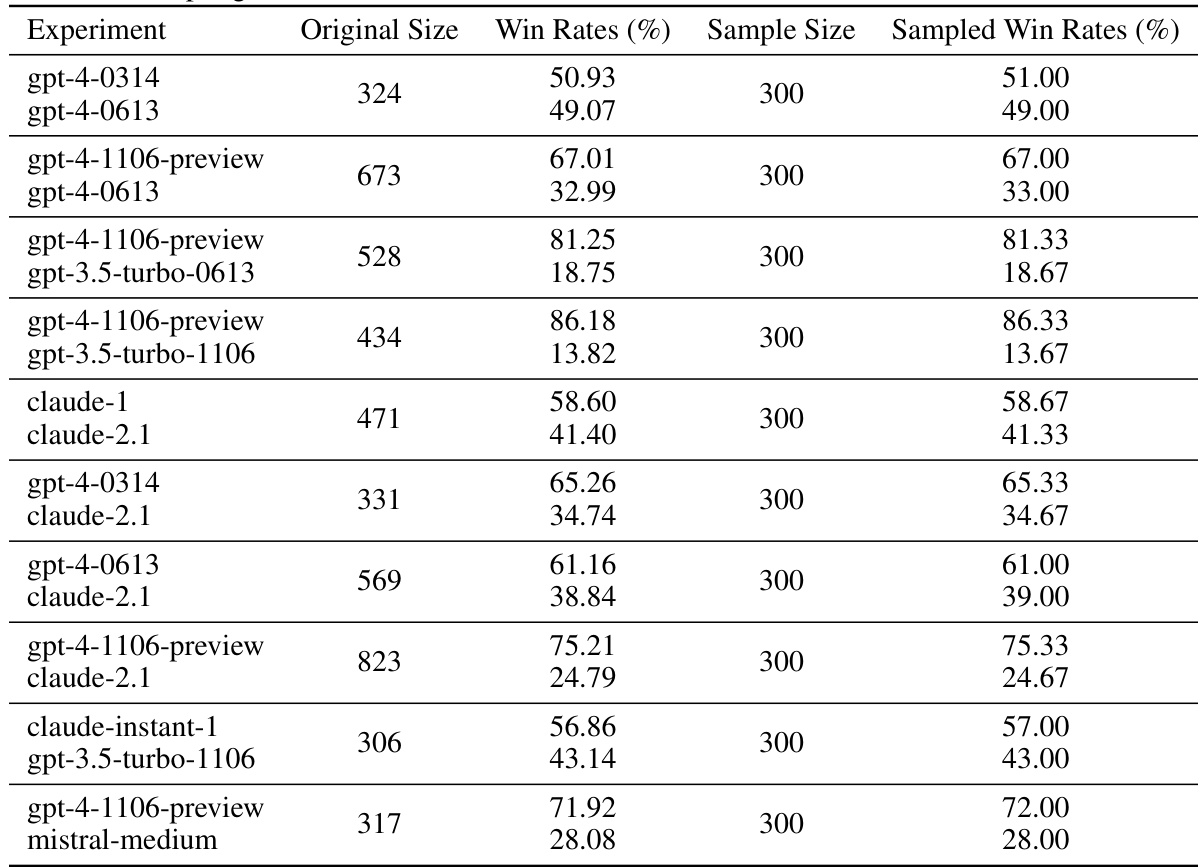

This table shows the win rates for different pairs of language models in selected paired comparison experiments. The win rate represents the proportion of times one model was preferred over another in pairwise comparisons with human evaluators. The data is used in Section 6 of the paper to validate the Elo rating system using real-world human feedback.

This table presents the win rates for various paired model comparisons from the LMSYS dataset [34], focusing on pairs with at least 300 non-tie comparisons. The original number of comparisons and the original win rates are shown, along with the win rates obtained from a controlled sampling method using 300 samples per pair. This allows for a more consistent evaluation of model performance across different sample sizes.

Full paper#