↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many vision-language datasets suffer from severe data imbalance, where some classes are over-represented while others are under-represented. This imbalance can lead to biased models that perform poorly on under-represented classes. Existing research has primarily focused on data curation to address this problem, but limited attention has been paid to understanding how models behave under such conditions.

This paper investigates why the CLIP model shows remarkable robustness to long-tailed pre-training data despite the imbalance. Through controlled experiments, the authors identify key factors contributing to CLIP’s robustness, including its dynamic classification approach, the use of descriptive language supervision, and the scale of the pre-training data. They also demonstrate that these factors can be transferred to other models, enabling models trained on imbalanced data to achieve similar performance to CLIP.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with imbalanced datasets, a prevalent issue in many machine learning applications. It offers transferable insights into how models can be made more robust to this problem, improving generalization and zero-shot performance. The findings are particularly valuable for those working in vision-language models and self-supervised learning. The practical techniques proposed can significantly impact model development.

Visual Insights#

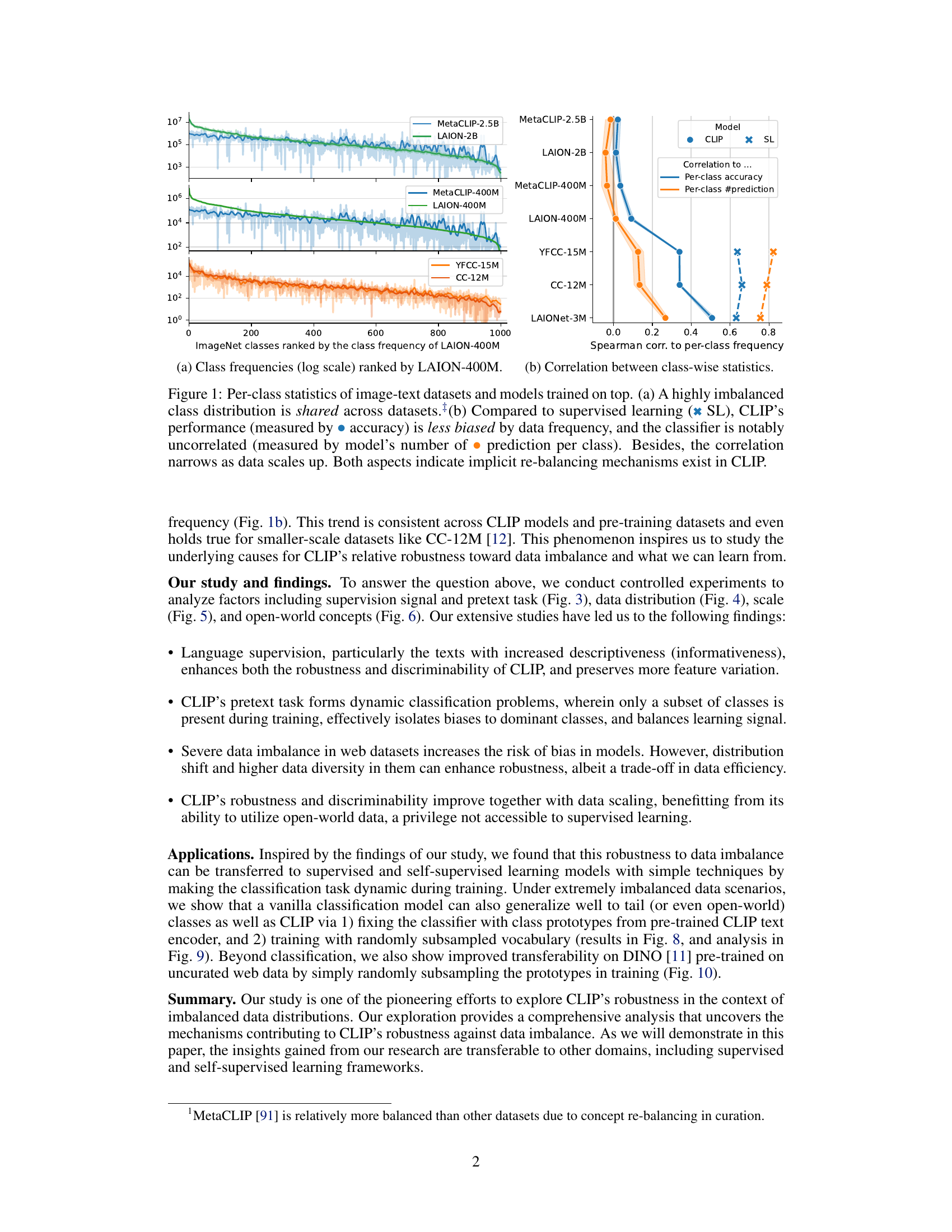

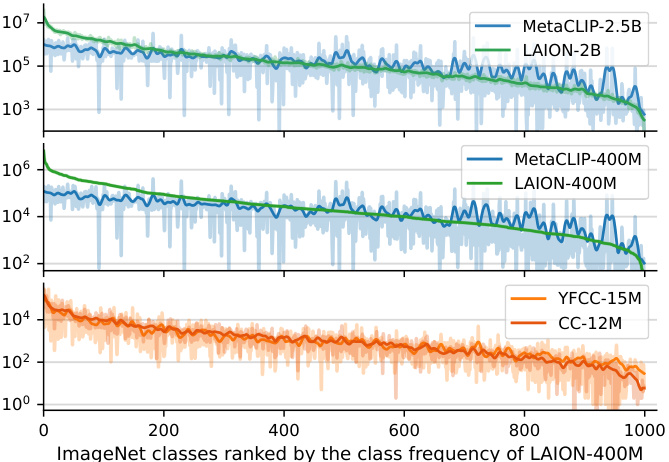

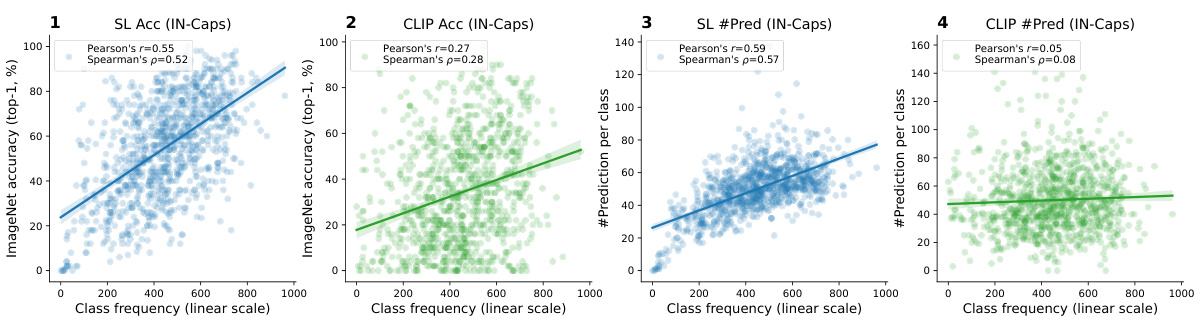

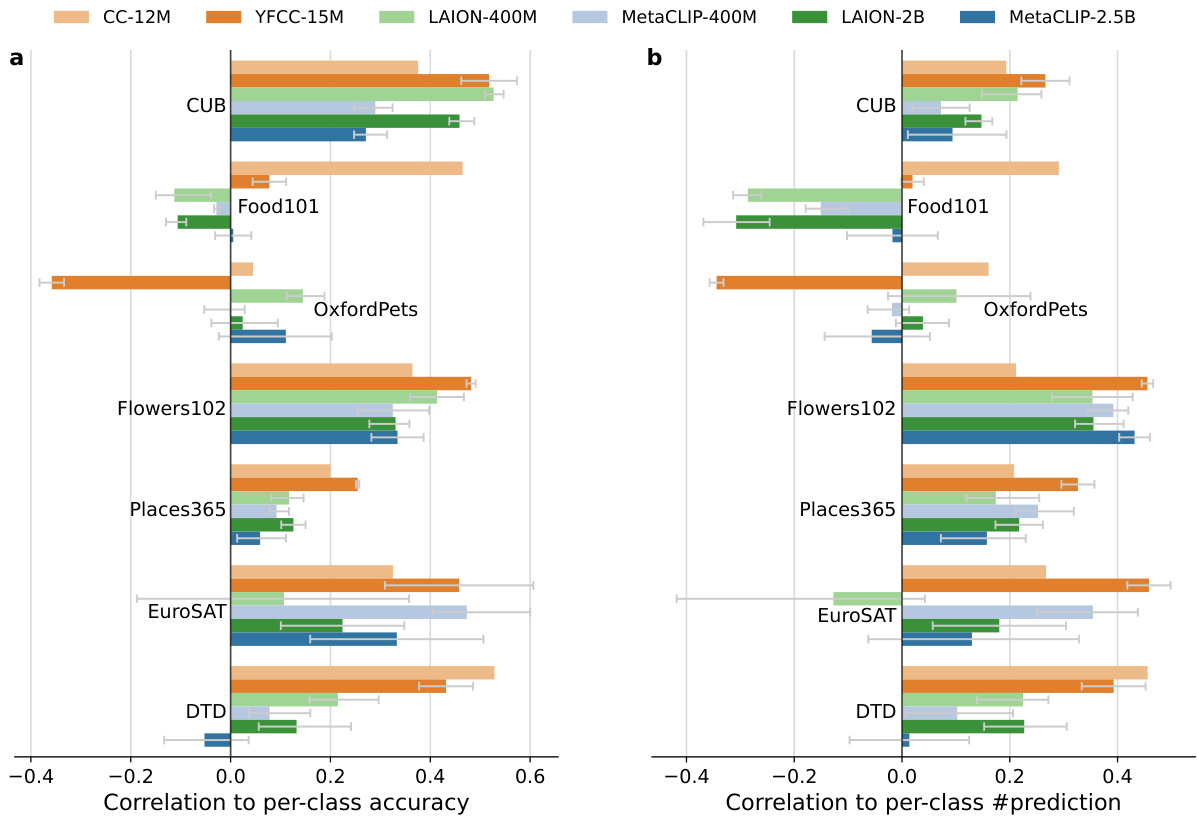

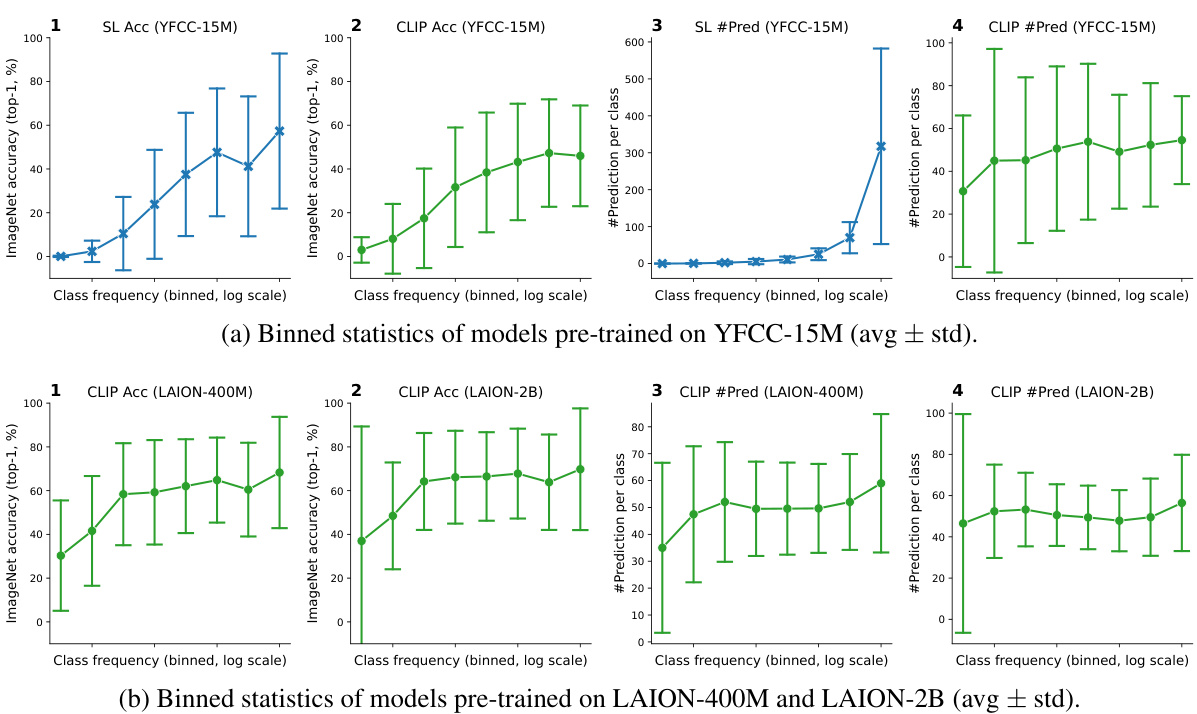

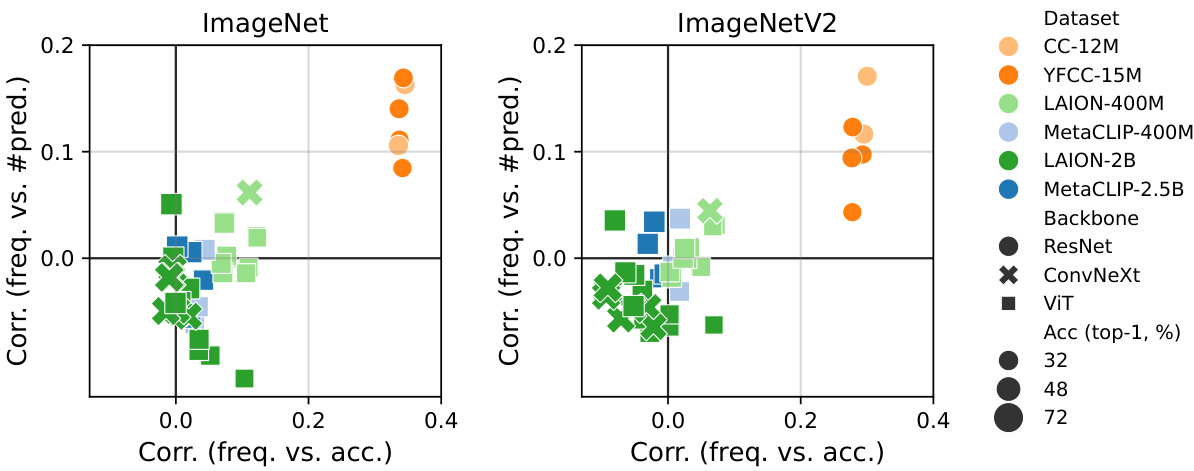

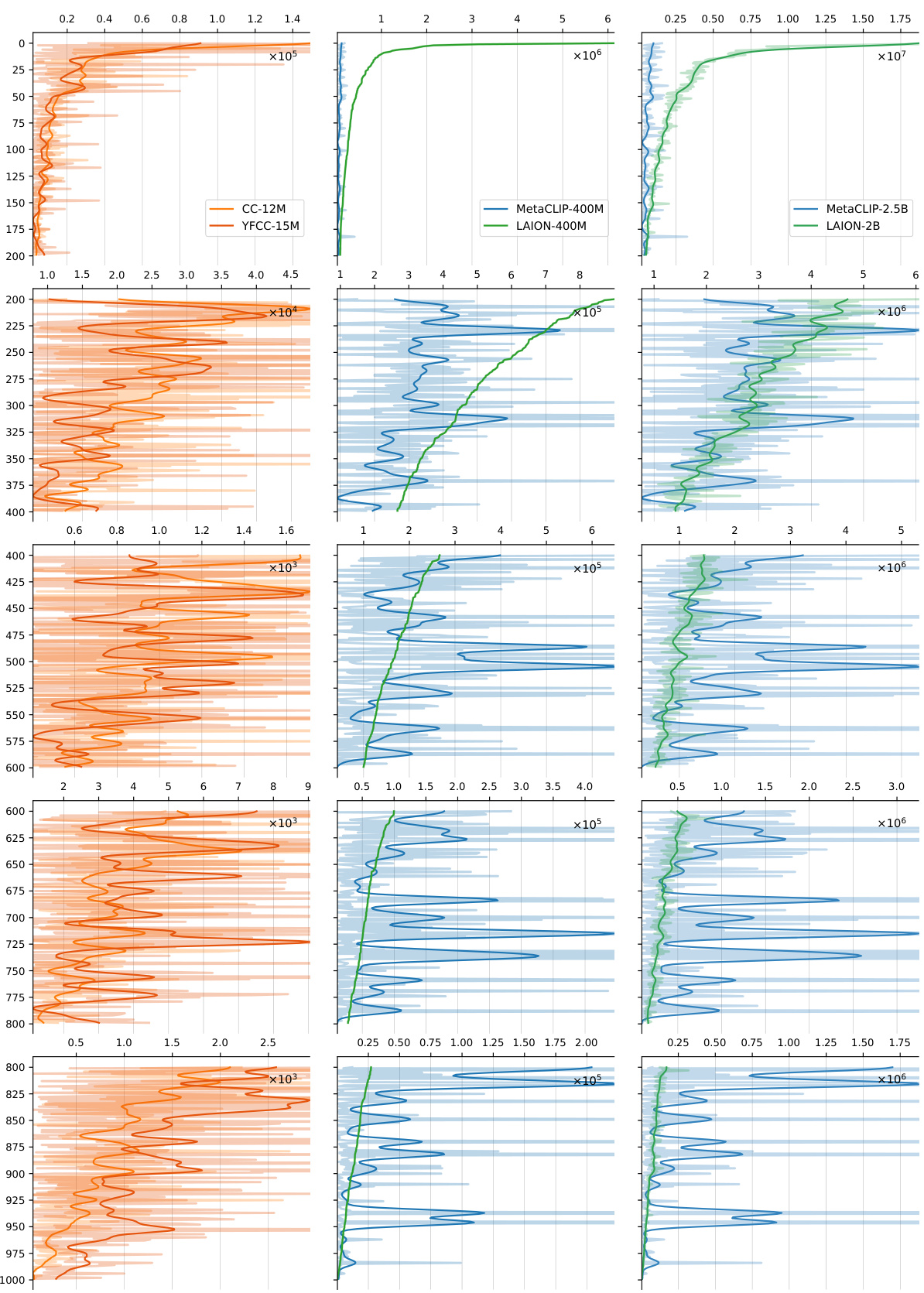

This figure shows the analysis of class distribution and model performance on different image-text datasets. Part (a) demonstrates the highly imbalanced nature of class distribution across various datasets (LAION-400M, MetaCLIP-400M, LAION-2B, MetaCLIP-2.5B, YFCC-15M, CC-12M). Part (b) compares CLIP’s performance with supervised learning models showing that CLIP is more robust to data imbalance. CLIP’s accuracy is less affected by class frequency, and the correlation between a class’s frequency and the model’s predictions decreases with increasing data scale, suggesting the presence of implicit mechanisms that balance the learning process.

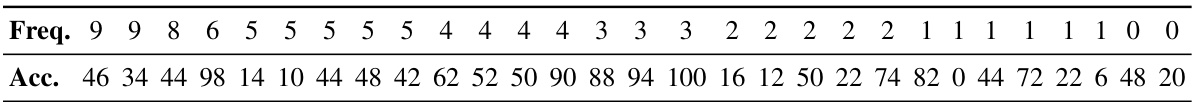

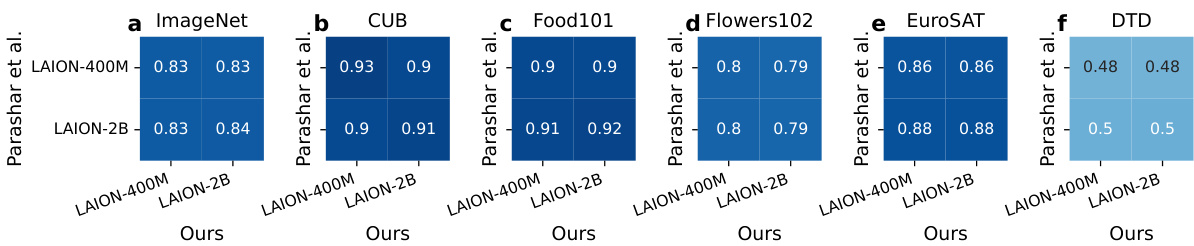

This table presents the frequency and accuracy of CLIP on tail classes in the YFCC-15M dataset. The ‘Freq.’ column indicates how many times each class appears in the dataset. The ‘Acc.’ column shows the accuracy CLIP achieved on each class. It highlights that even though some classes are extremely rare (appearing only once or twice), CLIP still manages to achieve relatively high accuracy on a subset of them, demonstrating robustness to data imbalance.

In-depth insights#

CLIP’s Robustness#

The research paper explores CLIP’s robustness, a key characteristic enabling its success in zero-shot image classification and transfer learning. CLIP demonstrates notable resilience to long-tailed pre-training data, outperforming supervised learning models trained on the same imbalanced datasets. This robustness is attributed to several factors: CLIP’s contrastive learning pretext task inherently balances the learning signal by dynamically focusing on a subset of classes at each training step; the use of descriptive language supervision enhances feature diversity and discriminability, further improving robustness; and the scale of the pre-training data plays a crucial role, as larger datasets with broader open-world concepts mitigate biases and improve generalization. The study highlights the transferability of CLIP’s robustness mechanisms, showing how similar approaches applied to supervised and self-supervised learning models can improve their performance on imbalanced datasets, thus providing valuable insights for enhancing model generalization and robustness in the face of real-world data imbalances.

Dynamic Class#

The concept of ‘Dynamic Class’ in a machine learning context, particularly within the framework of handling imbalanced datasets, introduces a novel approach to classifier training. Instead of a static, pre-defined set of classes, a dynamic class system allows the set of classes considered in each training iteration to vary. This is crucial for mitigating the adverse effects of long-tailed distributions where a few dominant classes overshadow the less frequent ones. By randomly sampling classes during training, the algorithm implicitly balances the learning signal, preventing overfitting to the dominant classes and promoting the learning of more generalized representations. The dynamic nature of the class selection also prevents the model from focusing solely on the prevalent features of the dominant classes, leading to improved performance on less-represented classes. This methodology shares similarities with techniques like data augmentation and curriculum learning, but differs significantly in its strategic focus on the dynamic manipulation of the learning signal itself, making it a powerful strategy for improving model robustness and generalizability in the presence of data imbalance.

Data Imbalance#

Data imbalance, a pervasive issue in large-scale datasets, significantly impacts model performance. This paper investigates how CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) handles this challenge, exhibiting surprising robustness compared to supervised learning methods. The study reveals that CLIP’s pretext task, a dynamic classification problem where only a subset of classes is present during training, helps mitigate the effects of skewed class distributions. This dynamic classification implicitly balances the learning signal, isolating the bias from dominant classes. The robustness further enhances with improved language supervision, larger datasets, and the inclusion of broader, open-world concepts. These findings demonstrate that data diversity and scale can enhance robustness to inherent imbalances, potentially offering transferable insights to improve model training in imbalanced scenarios.

Open-World Data#

The concept of ‘open-world data’ in the context of computer vision and large language models (LLMs) is crucial. It signifies data that is not limited to a predefined set of classes or concepts. This contrasts with the ‘closed-world’ assumption commonly used in traditional machine learning. Open-world data allows models to encounter and learn from a far broader range of visual and textual information, enhancing their robustness and generalization capabilities. This is particularly important in real-world scenarios where encountering novel objects or concepts is commonplace. However, working with open-world data introduces challenges. The inherent long-tailed distribution, where some classes are represented far more frequently than others, poses a significant challenge. This imbalance can lead to biased models that underperform on less-frequent classes. Furthermore, handling noisy or uncurated data inherent in open-world datasets requires robust techniques for data cleaning and preprocessing. Successfully training and evaluating models on open-world data necessitates innovative approaches that deal with this inherent data imbalance, such as dynamic classification or curriculum learning. The reward is a significant improvement in the generalization and robustness of models.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section presents exciting avenues for research. Extending the findings to other visual recognition tasks, such as object detection and segmentation, is crucial to assess the generalizability of the discovered mechanisms. Investigating the role of optimizers, like Adam, in handling heavy-tailed data distributions in CLIP and similar models is important. Exploring the interplay between language supervision and open-vocabulary learning is key. This involves further analysis of how language models enhance generalization beyond ImageNet classes. Investigating the inherent biases in datasets like ImageNet needs further research to understand if model biases are dataset-intrinsic or due to training processes. Additionally, future work could compare the robustness of CLIP to long-tailed data with that of other generative models and large language models to examine if the same strategies are universally effective. Finally, studying the effect of data diversity and imbalance on specific model components and how these impacts performance is critical for building robust models in real-world scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

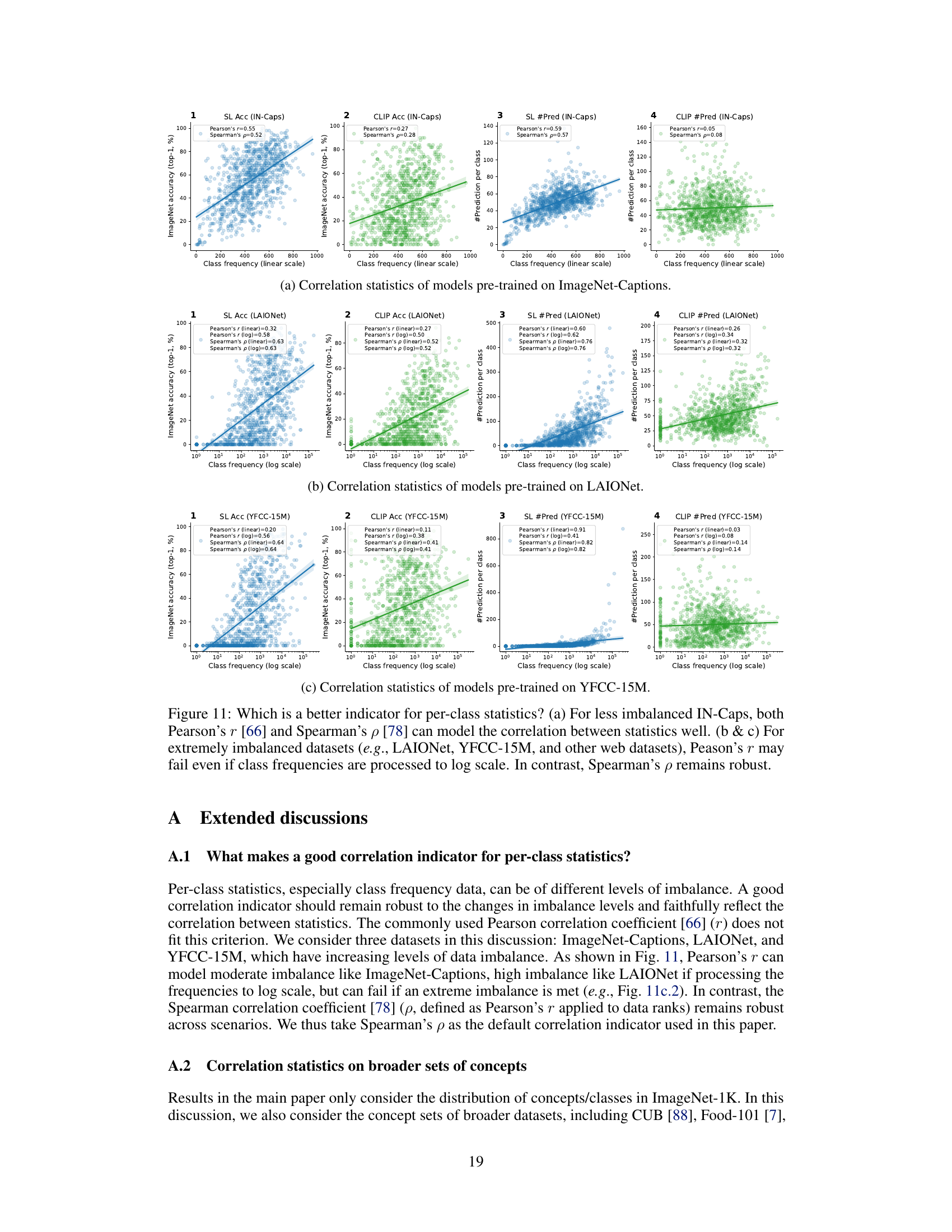

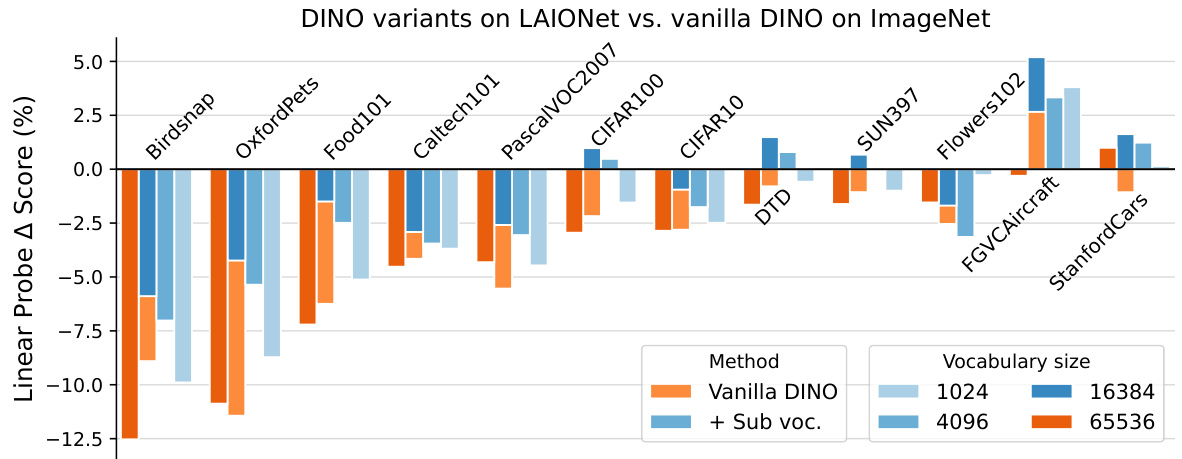

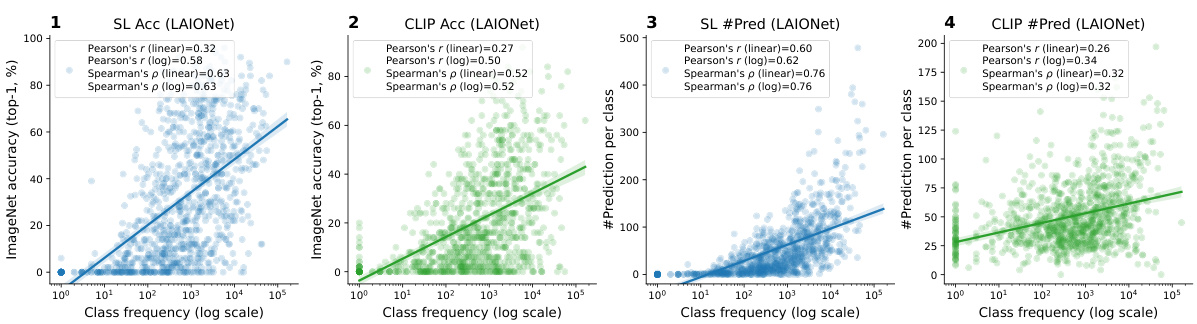

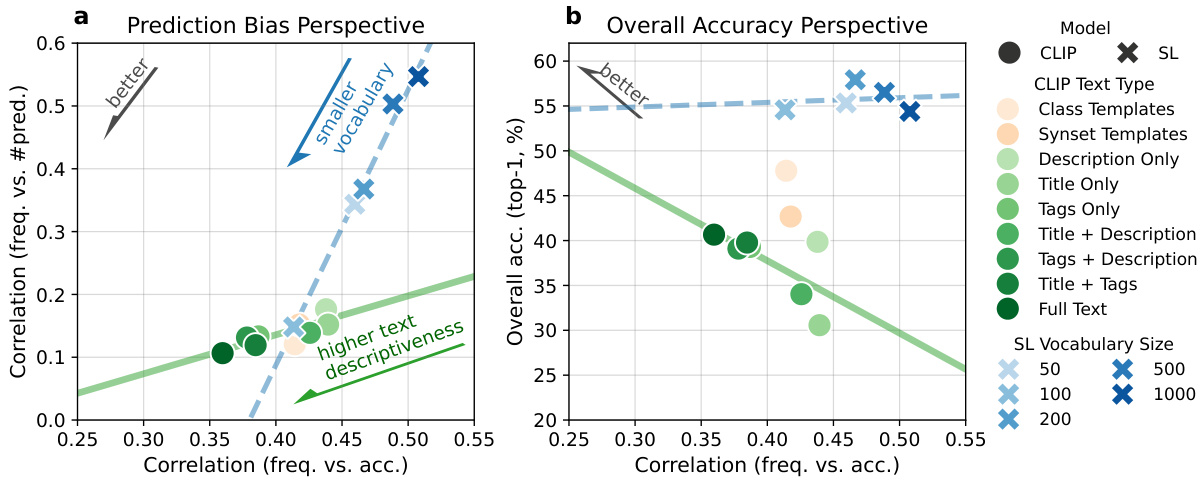

This figure shows the per-class statistics of various image-text datasets and the models trained on them. The left plot (a) demonstrates the highly imbalanced class distribution common across these datasets. The right plot (b) compares CLIP’s performance to that of supervised learning models. It shows that CLIP’s accuracy is less affected by the frequency of classes in the training data, and the number of predictions per class is less correlated with class frequency than in supervised learning. This effect becomes more pronounced as the dataset size increases, suggesting that CLIP incorporates mechanisms to implicitly balance the learning signal.

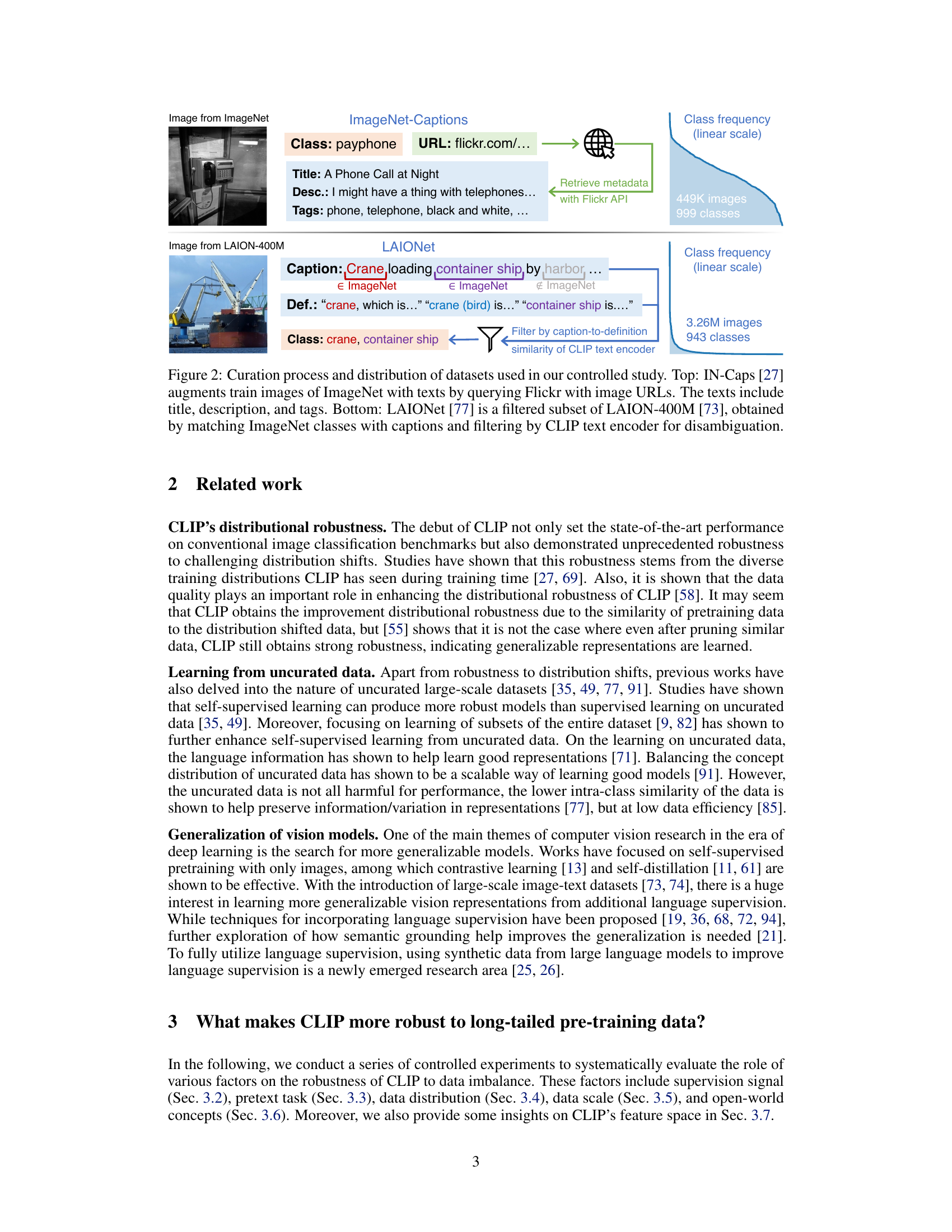

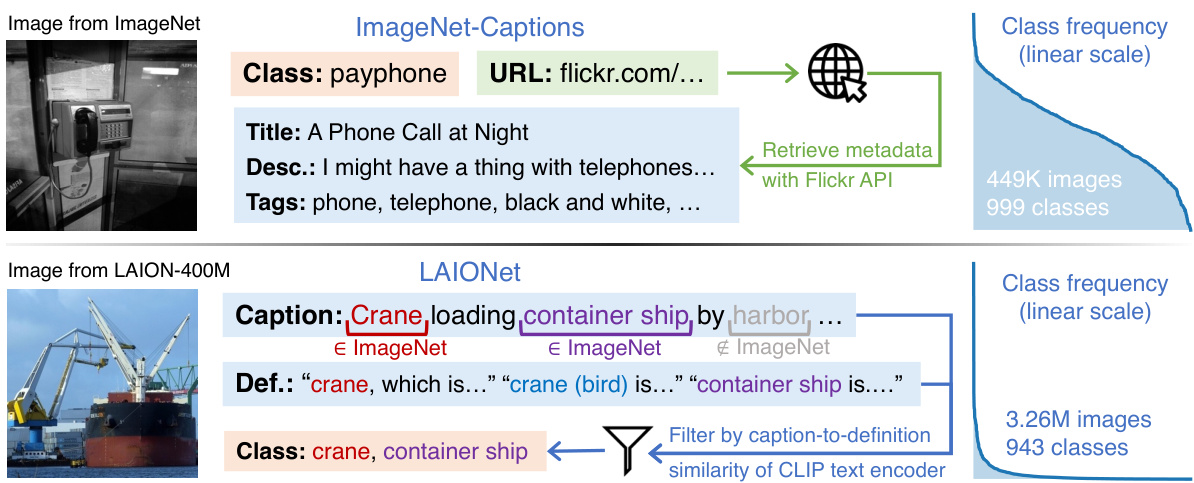

This figure illustrates the data curation processes and resulting data distributions for two datasets used in the controlled experiments: ImageNet-Captions (IN-Caps) and LAIONet. IN-Caps augments ImageNet images with text captions obtained via Flickr API queries using image URLs as input. The captions include titles, descriptions, and tags. LAIONet is a filtered subset of LAION-400M, where filtering is based on matching ImageNet classes with captions and using the CLIP text encoder to disambiguate and select only high-quality image-caption pairs.

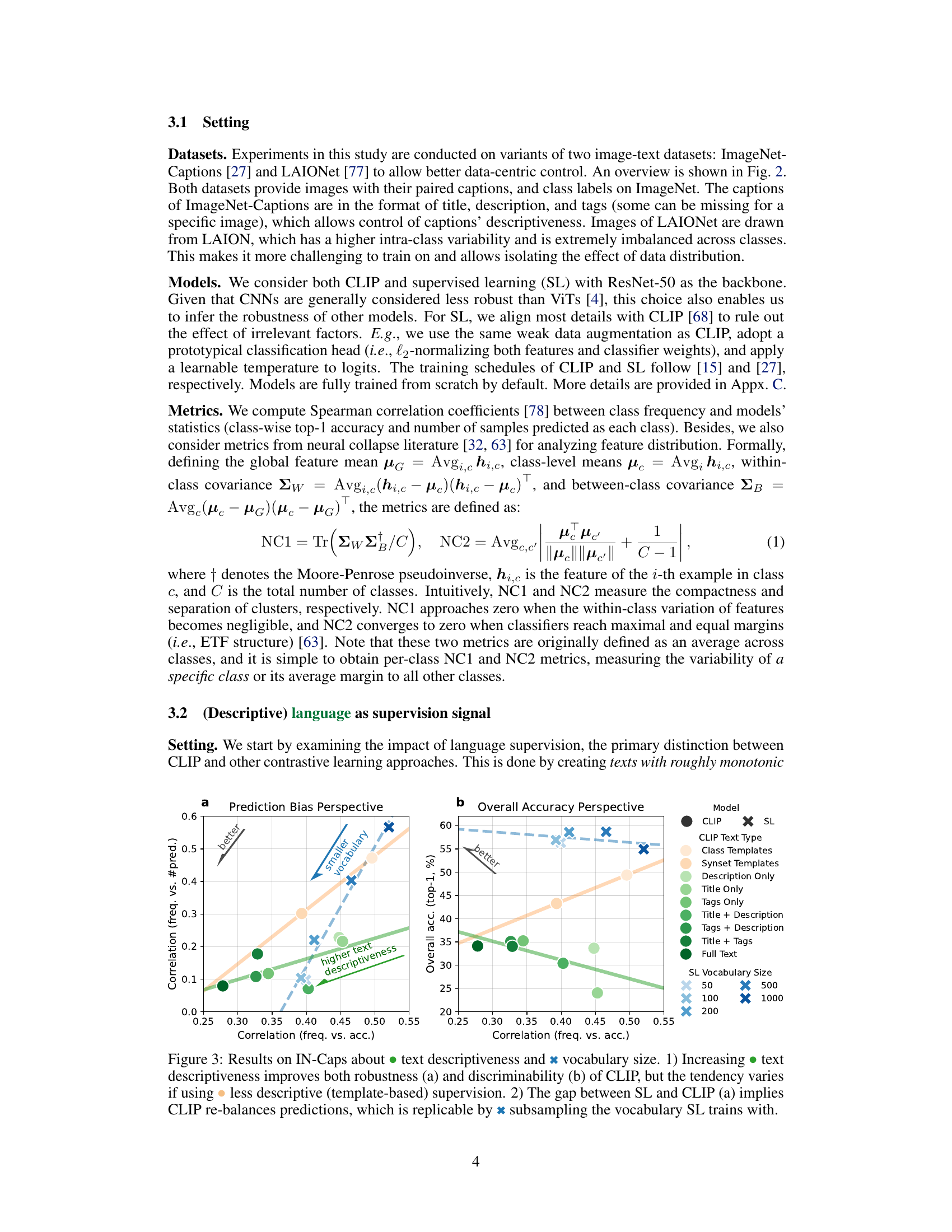

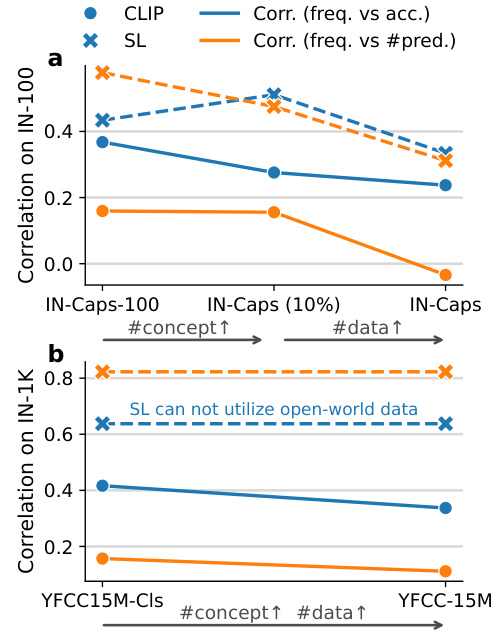

This figure analyzes the impact of language supervision and vocabulary size on the robustness and discriminability of CLIP and supervised learning (SL) models. It shows that more descriptive text supervision leads to better robustness and discriminability for CLIP, while the effect is less pronounced for less descriptive (template-based) supervision. The comparison between CLIP and SL highlights CLIP’s implicit prediction re-balancing mechanism, which can be replicated in SL by subsampling the training vocabulary.

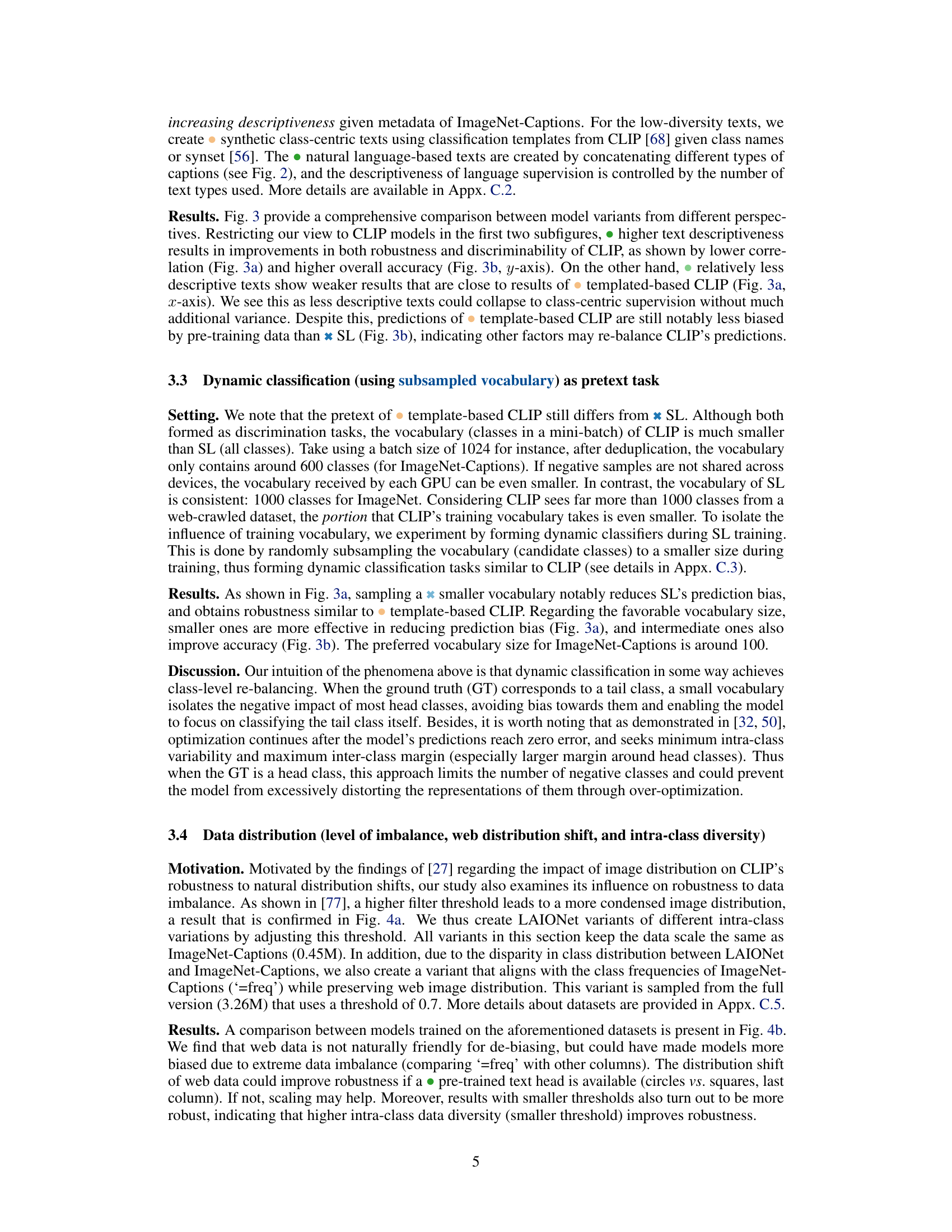

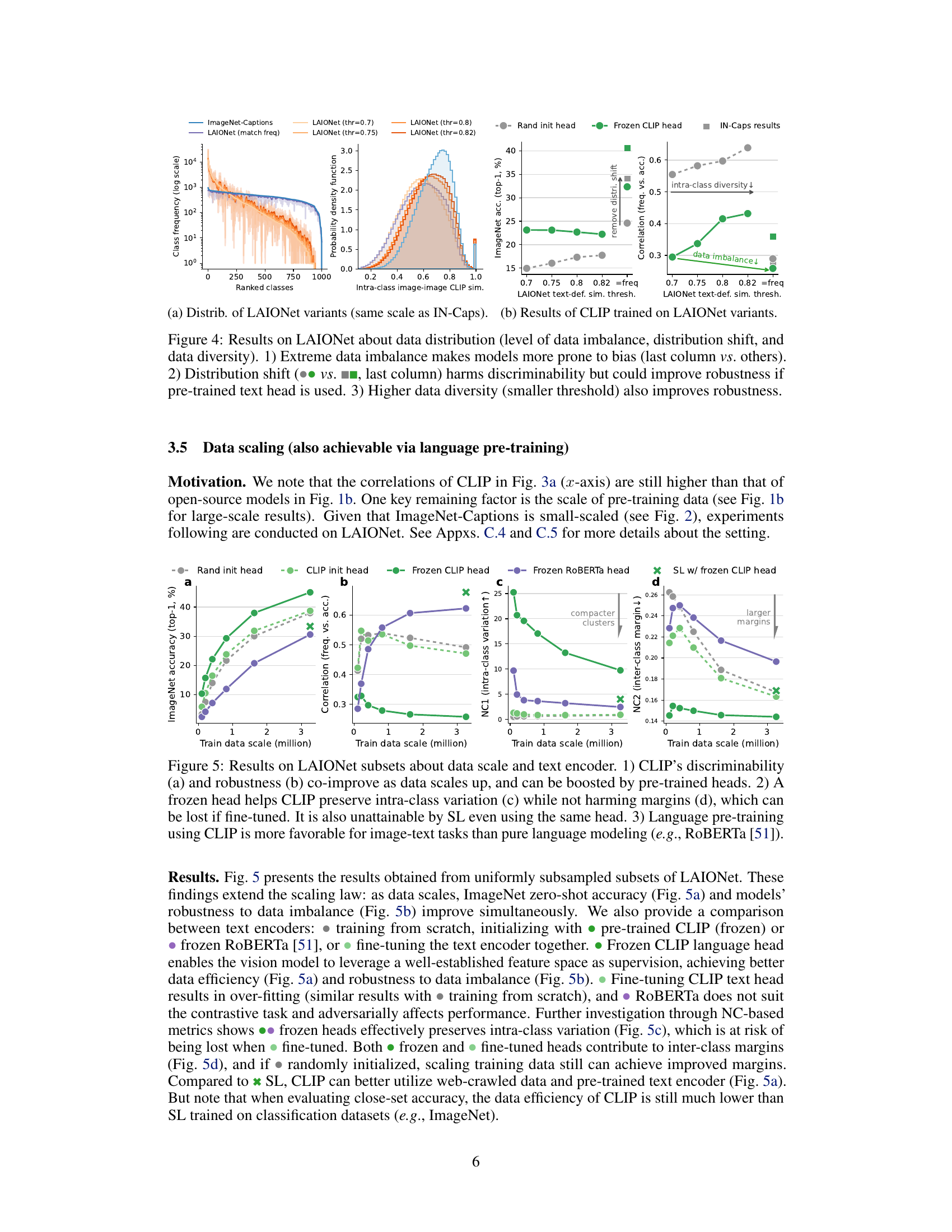

This figure presents a comprehensive analysis of the impact of data distribution on the robustness of CLIP models to data imbalance. It uses different variants of the LAIONet dataset to manipulate the level of data imbalance, distribution shift, and intra-class diversity. The results show that extreme data imbalance increases the risk of model bias. Distribution shifts can harm discriminability, but if a pre-trained text head is used, they can actually improve robustness. Finally, higher data diversity is shown to improve robustness.

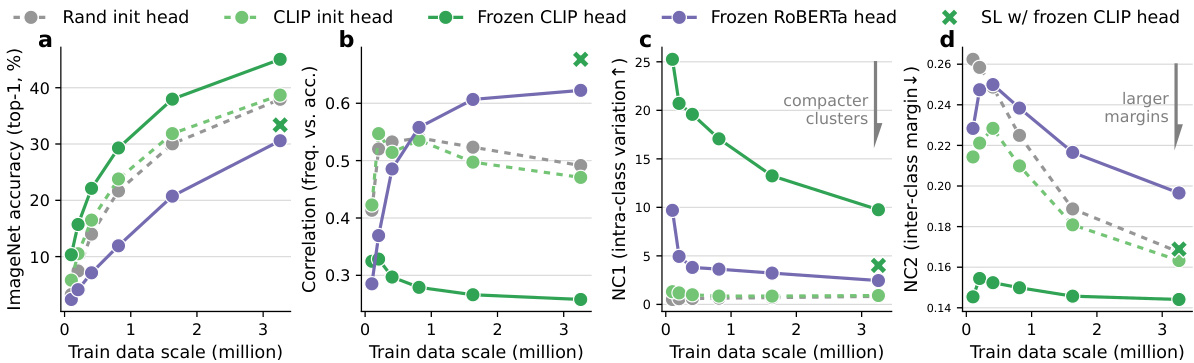

This figure examines the effect of data scale and text encoder on CLIP’s performance. It shows that CLIP’s discriminability and robustness to data imbalance improve with increasing data scale. Using pre-trained heads enhances these effects further. The figure also compares using a frozen vs. fine-tuned text encoder, showing that a frozen pre-trained CLIP text encoder maintains intra-class variation better than a fine-tuned one. Finally, it highlights that language pre-training with CLIP is superior to language modeling alone for image-text tasks.

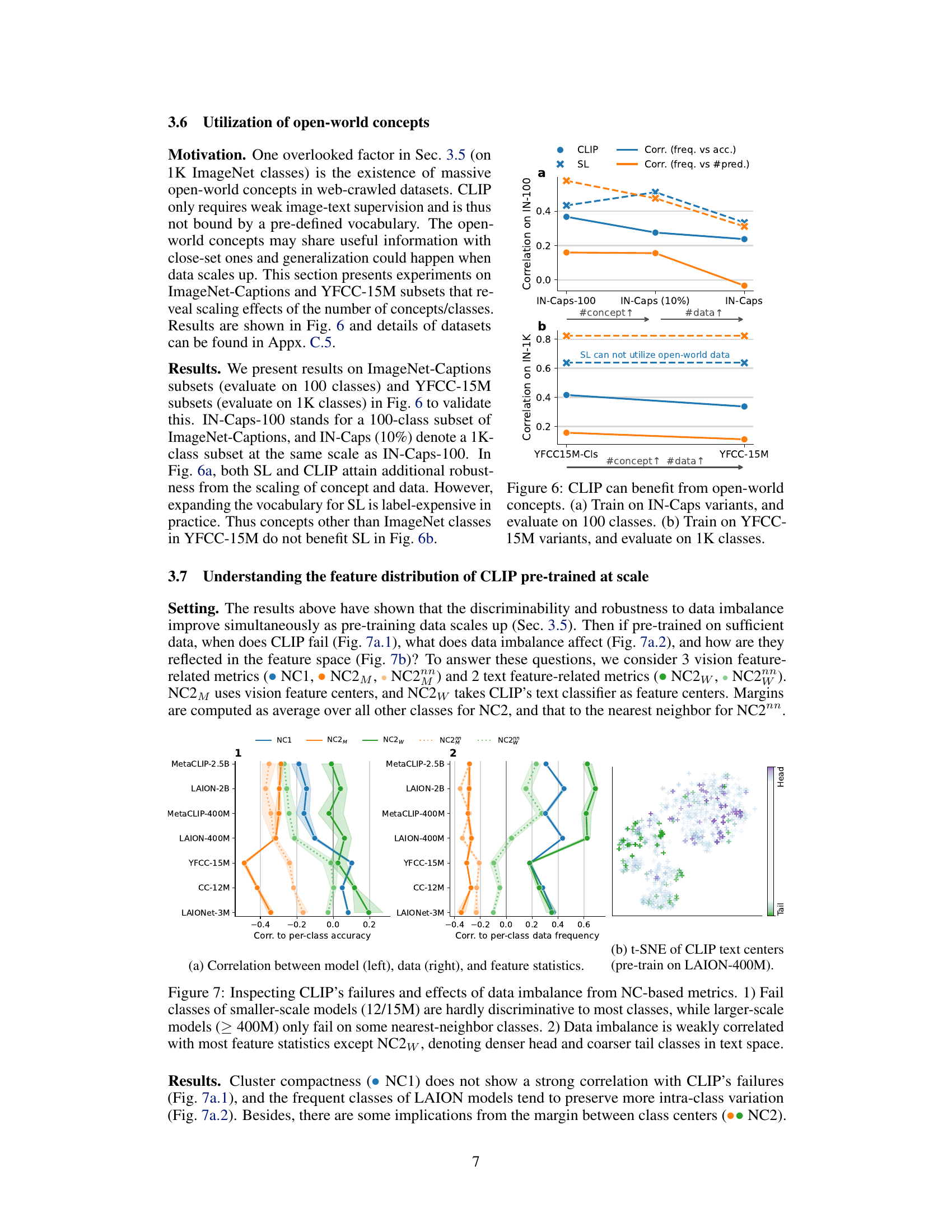

This figure shows that CLIP models benefit from the utilization of open-world concepts. In the left panel (a), CLIP models are trained on IN-Caps variants (ImageNet-Captions datasets with varying numbers of concepts/classes), and evaluated on 100 ImageNet classes. This shows that increasing the number of concepts improves robustness to data imbalance in the training datasets. The right panel (b) follows a similar approach, but utilizes YFCC-15M datasets, which contain a larger number of concepts/classes, and evaluates performance on 1000 ImageNet classes. Supervised learning models (SL) show a decreased performance due to inability to utilize the additional information provided by the open-world concepts, illustrating CLIP’s advantage in handling data imbalance.

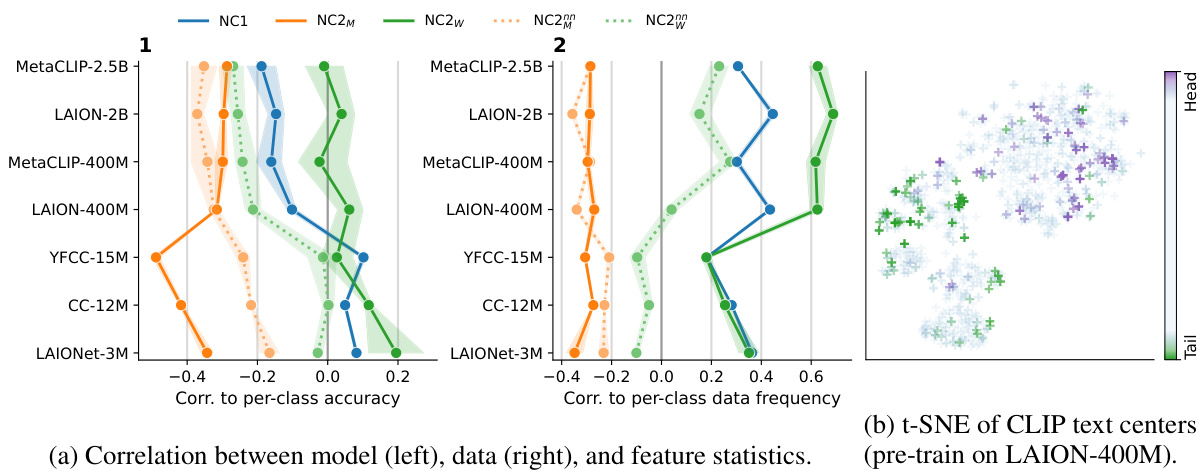

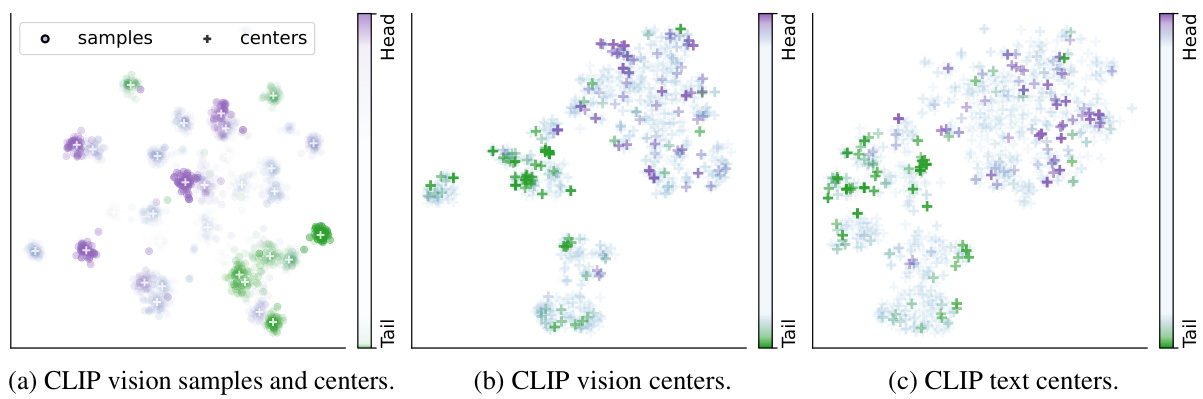

This figure analyzes the failure modes of CLIP models trained on different scales of data and how data imbalance affects these models. The left panels (a) show correlations between various metrics (NC1, NC2M, NC2w, NC2, NC2nn) indicating compactness and separation of clusters in feature space, and per-class accuracy and frequency. It reveals that smaller models fail on many classes, while larger models mainly fail on classes that are close in feature space to other classes. The right panel (b) presents t-SNE visualization of CLIP text centers, highlighting that data imbalance leads to denser head and coarser tail classes in the text feature space. These findings suggest that scale and data distribution impact CLIP’s robustness to data imbalance.

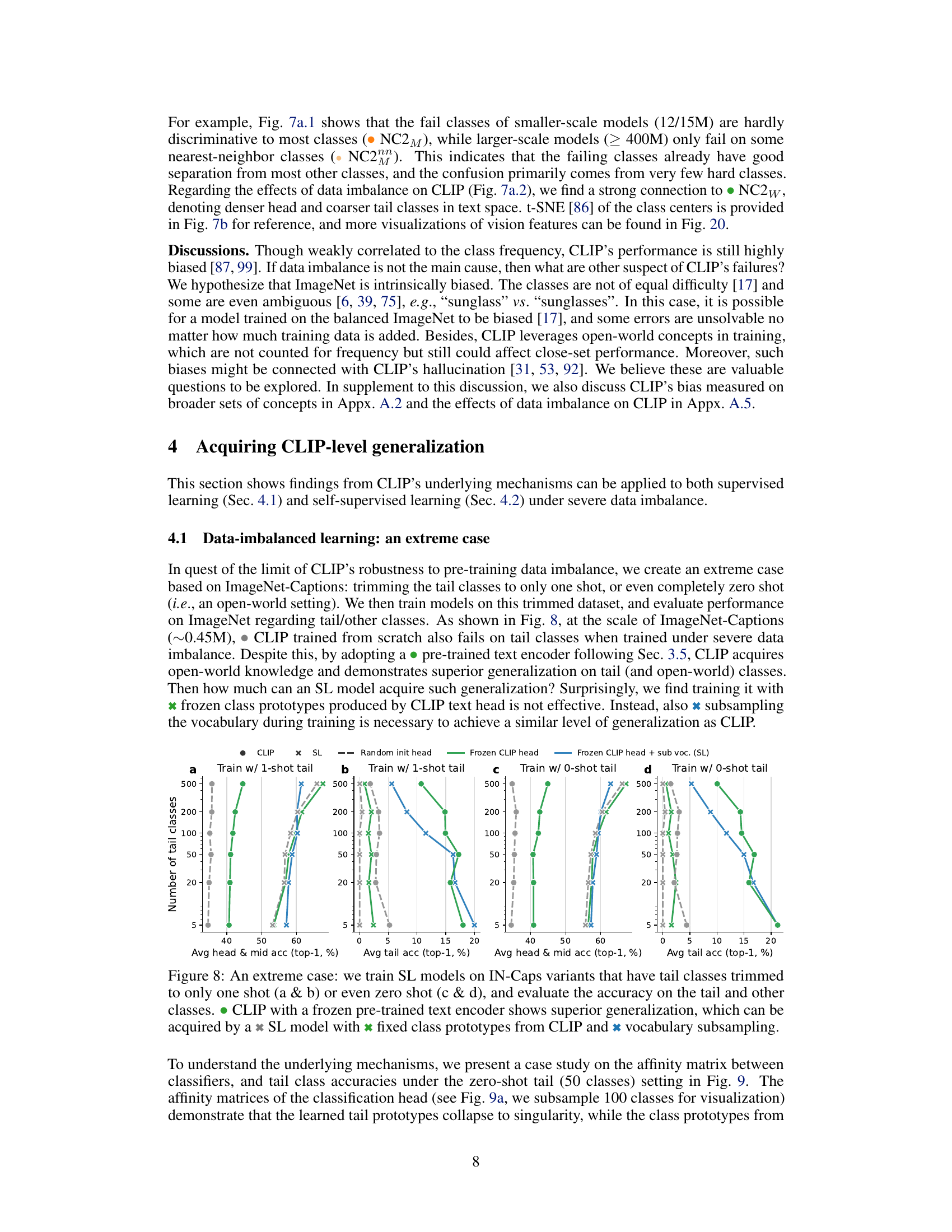

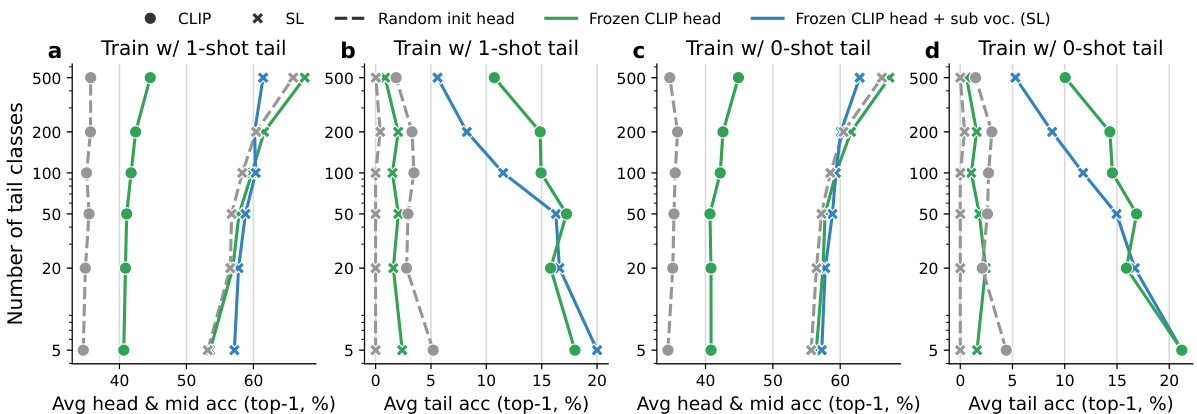

This figure shows the results of training supervised learning (SL) models on a highly imbalanced dataset (ImageNet-Captions with tail classes reduced to one or zero shots). It compares the performance of several approaches: standard SL, SL using a frozen CLIP text encoder, SL with a frozen CLIP head and vocabulary subsampling, and CLIP. The results show that CLIP generalizes better to tail classes than SL, even under these extreme conditions. Vocabulary subsampling helps SL achieve performance closer to CLIP, highlighting the importance of the dynamic vocabulary nature of the CLIP pretext task.

This figure shows a comparison of the behavior of supervised learning (SL) and CLIP models when trained on a dataset with extremely few examples of certain classes (zero-shot tail setting). Part (a) shows affinity matrices, illustrating the relationship between classifiers. It highlights how in SL models, the tail class prototypes (representations of classes with few examples) cluster tightly together, indicating a lack of distinction between them. In contrast, CLIP exhibits a healthier structure with more distinct representations. Part (b) presents distributions of model’s per-class statistics, demonstrating that simply using a pre-trained CLIP head in SL is not sufficient for good generalization, while combining it with vocabulary subsampling can achieve performance similar to CLIP.

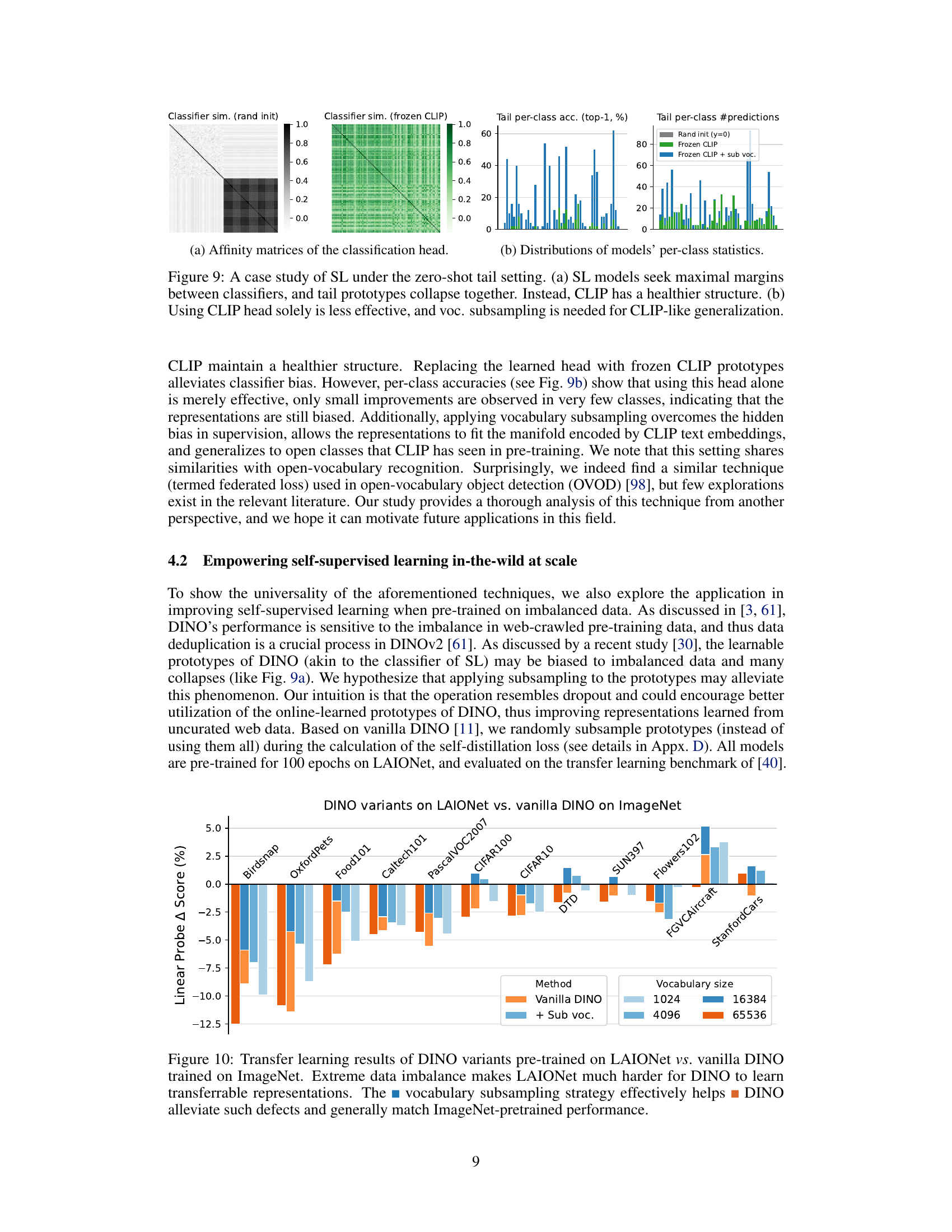

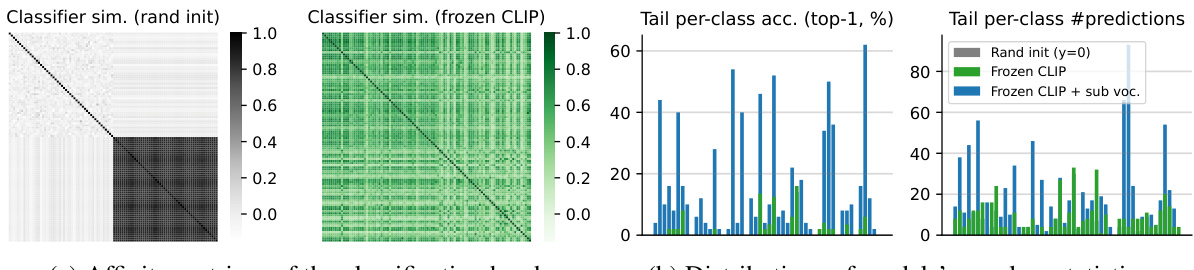

This figure compares the transfer learning performance of different DINO models. The models are pre-trained on either ImageNet or a version of LAIONet that has an extreme class imbalance. The results show that the standard DINO model struggles to transfer well when trained on the imbalanced LAIONet data. However, a modified DINO model that uses a vocabulary subsampling strategy performs significantly better, achieving performance comparable to the model trained on balanced ImageNet data. This demonstrates the effectiveness of vocabulary subsampling in mitigating the negative effects of data imbalance on the transfer learning capability of the model.

This figure shows the per-class statistics of several image-text datasets (LAION-400M, MetaCLIP-400M, LAION-2B, MetaCLIP-2.5B, YFCC-15M, CC-12M, LAIONet-3M) and the models trained on them. Subfigure (a) demonstrates that all datasets share a highly imbalanced class distribution. Subfigure (b) compares the performance of CLIP and supervised learning models. It shows that CLIP’s performance is less affected by the class frequency of the training data, implying an implicit re-balancing mechanism. The correlation between class-wise performance and frequency decreases as the dataset scale increases.

This figure shows the per-class statistics of several image-text datasets and the models trained on them. Panel (a) demonstrates the highly imbalanced class distribution present across various datasets. Panel (b) compares the performance of CLIP models with supervised learning models. It highlights that CLIP is less affected by data imbalance, showing weaker correlation between a class’s performance and its frequency in the training data. This effect is more pronounced as the scale of the training data increases, suggesting implicit re-balancing mechanisms within the CLIP training process.

This figure compares the effectiveness of Pearson’s r and Spearman’s ρ as correlation indicators for per-class statistics in datasets with varying levels of imbalance. It shows that while Pearson’s r performs well on less imbalanced datasets, it fails to accurately reflect the correlation in extremely imbalanced datasets, even when using a log scale for class frequencies. In contrast, Spearman’s ρ consistently performs well across different levels of data imbalance, making it a more robust correlation measure in such cases.

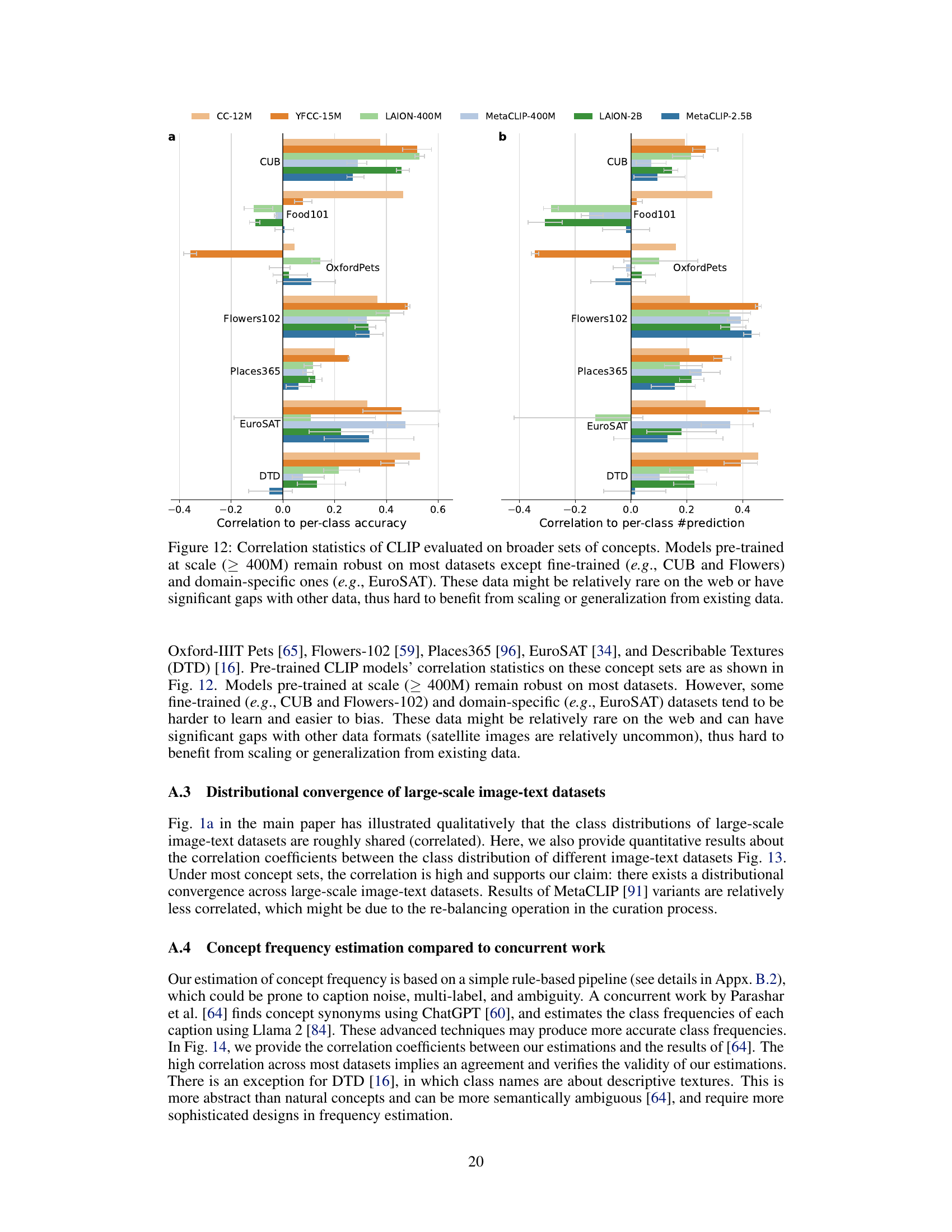

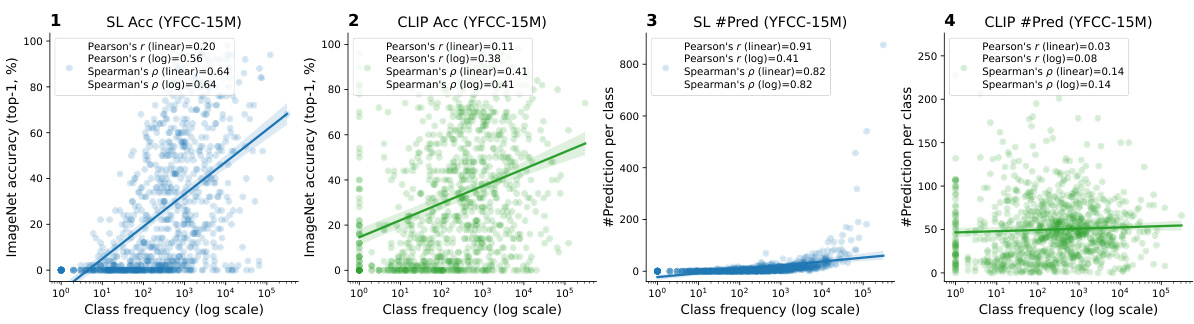

This figure displays the correlation between per-class accuracy and the number of predictions for various CLIP models tested on several datasets (CUB, Flowers102, Places365, EuroSAT, DTD, Food101, Oxford Pets). The models were pre-trained on different scales of data, and the graph shows that larger models (≥ 400M) are more robust, but struggle with fine-grained or domain-specific datasets. The results suggest that data scarcity and differences in data distribution may limit the ability to scale performance improvements.

This figure shows the per-class statistics of several large-scale image-text datasets and the models trained on them. The left subplot (a) demonstrates the highly imbalanced class distribution shared across these datasets; classes are extremely unevenly represented. The right subplot (b) compares the performance of CLIP models to those trained with supervised learning (SL). It reveals that CLIP is less sensitive to the class imbalance than SL, as indicated by a weaker correlation between a class’s accuracy and its frequency in the training data. Moreover, this insensitivity to imbalance seems to increase with the scale of the training data.

This figure shows the per-class statistics of various image-text datasets and the models trained on them. The left subplot (a) illustrates the highly imbalanced class distribution common across these datasets. The right subplot (b) compares the performance of CLIP and supervised learning models. CLIP shows less bias towards frequent classes and a weaker correlation between class performance and frequency, indicating an implicit re-balancing mechanism within CLIP. This effect becomes more pronounced as the dataset size increases.

This figure shows the per-class statistics of different image-text datasets and the models trained on them. Panel (a) demonstrates that a highly imbalanced class distribution is a common characteristic across various datasets. Panel (b) compares CLIP’s performance to that of supervised learning models. It reveals that CLIP’s accuracy is less affected by the class frequency in the training data, exhibiting a weaker correlation between class accuracy and frequency. This suggests that CLIP implicitly balances the learning signal, mitigating the impact of data imbalance. The correlation further decreases as the scale of the training data increases.

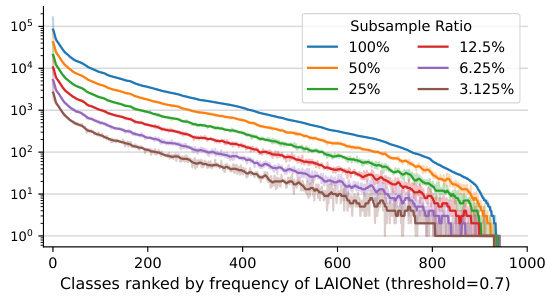

This figure shows the distribution of classes in various subsets of the LAIONet dataset. Different subsets are created by applying different thresholds to the text-definition similarity scores. The x-axis represents the classes ranked by frequency in the full LAIONet dataset (with a threshold of 0.7), and the y-axis shows the number of images per class. The different lines represent subsets of LAIONet with varying subsampling ratios. The figure illustrates the impact of different subsampling strategies on the class distribution.

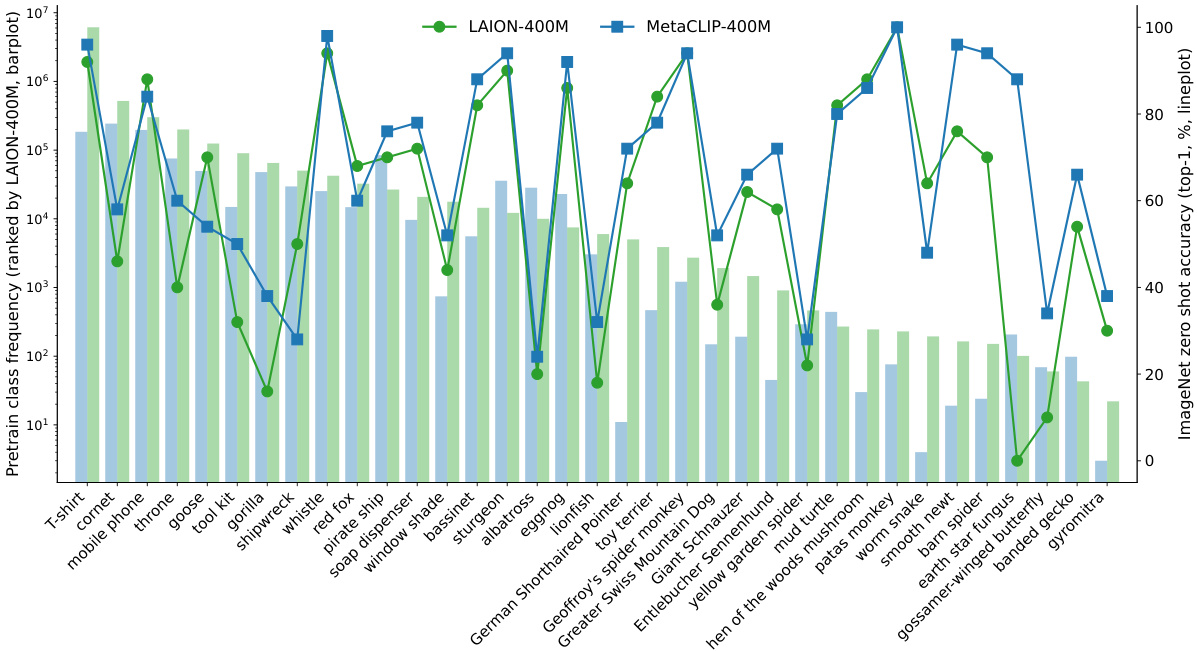

This figure shows the class frequency and zero-shot accuracy of two CLIP models (LAION-400M and MetaCLIP-400M) on a subset of ImageNet classes. The bar plot represents the frequency of each class in the pre-training data, while the line plot shows the zero-shot accuracy achieved by each model for each class. The figure highlights the weak correlation between class frequency (how often a class appears in the training data) and zero-shot accuracy (how well the model can classify the class without any fine-tuning). This demonstrates that CLIP’s performance is not heavily biased towards frequent classes, even with a highly imbalanced dataset.

This figure shows the per-class statistics of several large-scale image-text datasets and the models trained on them. The left panel (a) demonstrates that all datasets exhibit a highly imbalanced class distribution, meaning some classes have many more examples than others. The right panel (b) compares CLIP’s performance to that of supervised learning models. It reveals that CLIP is less sensitive to this class imbalance, exhibiting a weaker correlation between a class’s performance and its frequency in the training data. Moreover, this insensitivity to class imbalance becomes more pronounced as the scale of the training data increases. This suggests that CLIP employs implicit mechanisms to rebalance the learning signal.

This figure shows the effects of text descriptiveness and vocabulary size on the robustness and discriminability of CLIP compared to supervised learning (SL). Panel (a) shows the correlation between class-wise accuracy and frequency, revealing CLIP’s improved robustness with more descriptive text and a smaller vocabulary, while SL shows more bias. Panel (b) shows that overall accuracy is better for CLIP when using more descriptive text, even with a smaller vocabulary. The results suggest that a dynamic classification task with a smaller vocabulary, as in CLIP, helps improve robustness and discriminability. Subsampling the vocabulary in SL can replicate CLIP’s performance.

This figure shows the t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) visualization of the multi-modal feature space learned by CLIP. It visualizes samples and their class centers from both the vision and text encoders separately, highlighting the modality gap. Subfigure (a) shows a subset of samples and their corresponding vision class centers. Subfigure (b) presents all ImageNet class centers from the vision encoder, and subfigure (c) displays the text class centers which are the same as in figure 7b. The separation of vision and text feature spaces is emphasized.

This figure shows a comparison of the class distribution and model performance for various image-text datasets and models trained on them. Part (a) illustrates that all datasets share a highly imbalanced class distribution, where some classes appear far more frequently than others. Part (b) shows that CLIP models are less affected by the data imbalance compared to supervised learning models, as indicated by weaker correlations between class performance and frequency. This suggests CLIP possesses implicit mechanisms that handle class imbalance.

Full paper#