↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large Language Model (LLM) alignment is crucial for safe AI development. Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) is a complex, often brittle process susceptible to “reward hacking.” Direct Alignment Algorithms (DAAs) offer an alternative, bypassing explicit reward modeling. However, this paper demonstrates that DAAs also suffer from over-optimization, exhibiting performance degradation at higher KL budgets and sometimes even before completing a single epoch. This occurs even though DAAs don’t use explicit reward models. This highlights a significant issue that needs further attention in developing safe and reliable LLMs.

This research investigates over-optimization in DAAs via extensive empirical experiments across diverse model scales and hyperparameters. The study unifies several DAA methods under a common framework and finds that they exhibit similar degradation patterns to classical RLHF methods. It establishes scaling laws applicable to DAAs to predict this over-optimization, providing a unifying framework for understanding and mitigating this issue across objectives, training regimes, and model scales. The findings provide crucial insights into the under-constrained nature of DAA optimization and offer avenues for developing more robust methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it reveals the under-constrained nature of optimization in Direct Alignment Algorithms (DAAs), a popular alternative to RLHF in LLM alignment. It highlights the prevalent over-optimization problem in DAAs, offering valuable insights and urging further research into robust and efficient alignment methods. This is important because safe and effective LLM alignment is a critical and urgent need in the AI community.

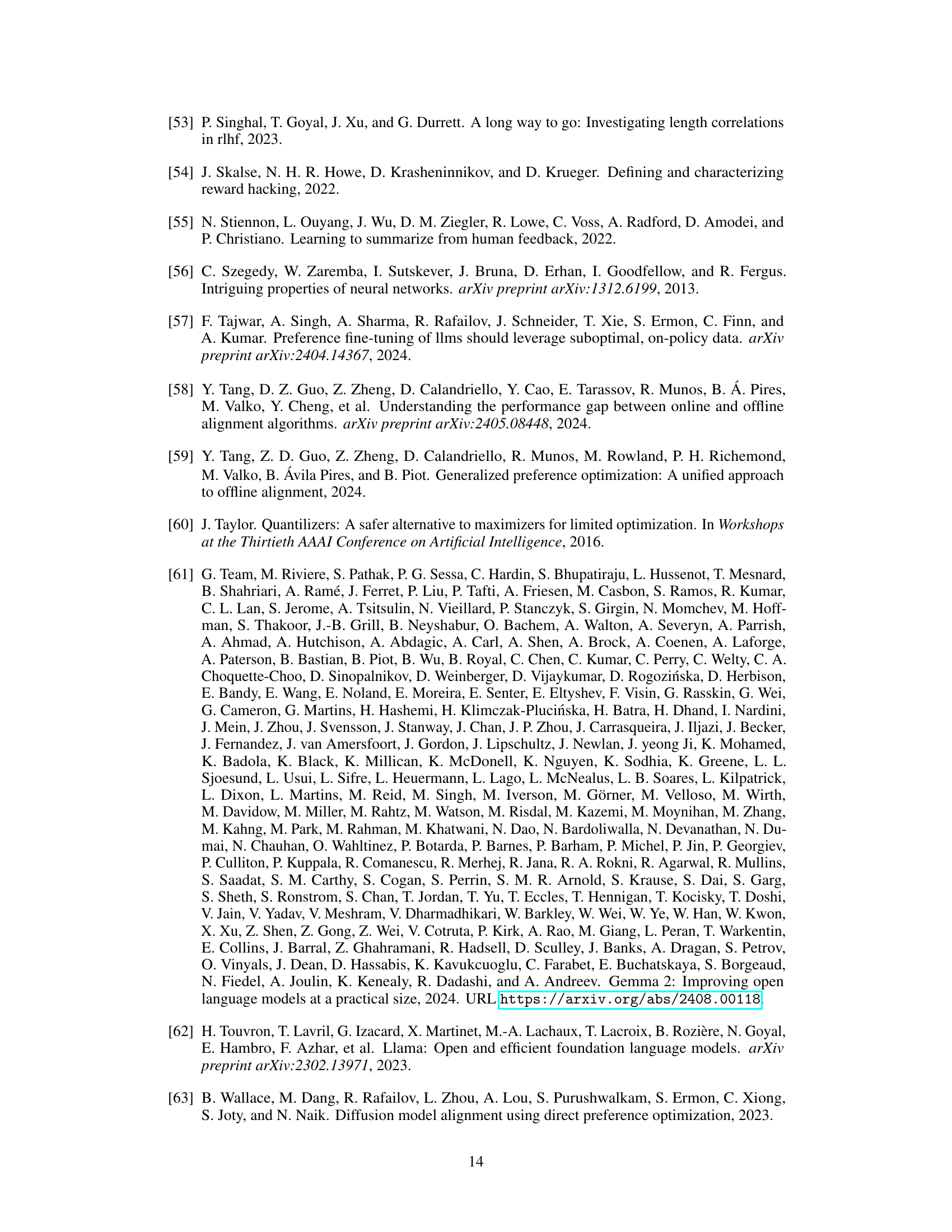

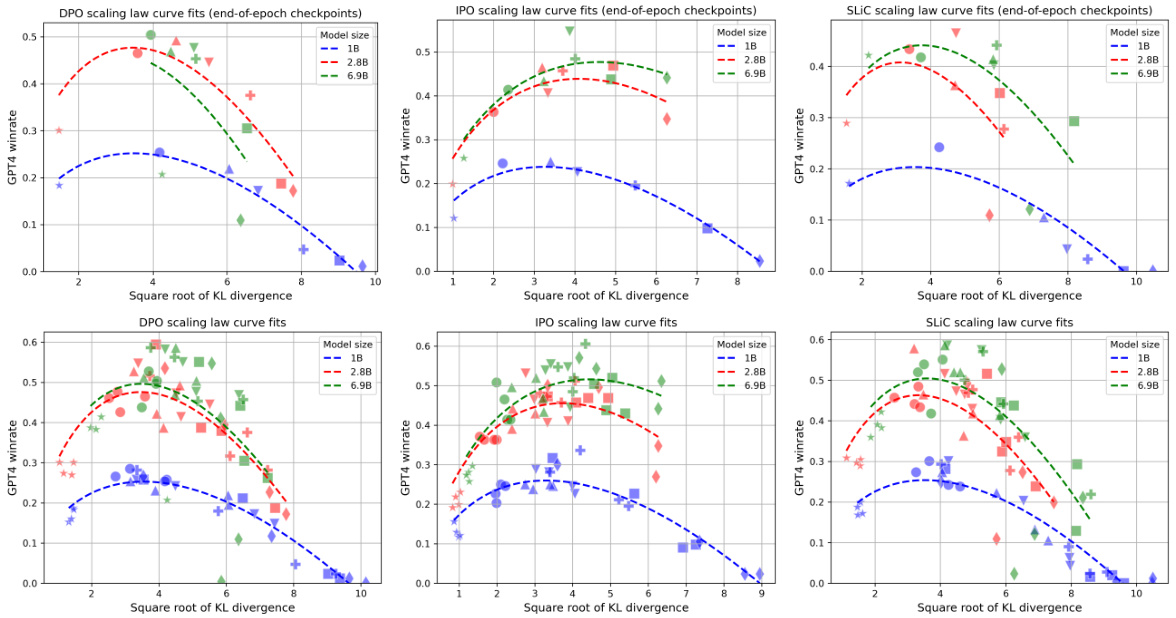

Visual Insights#

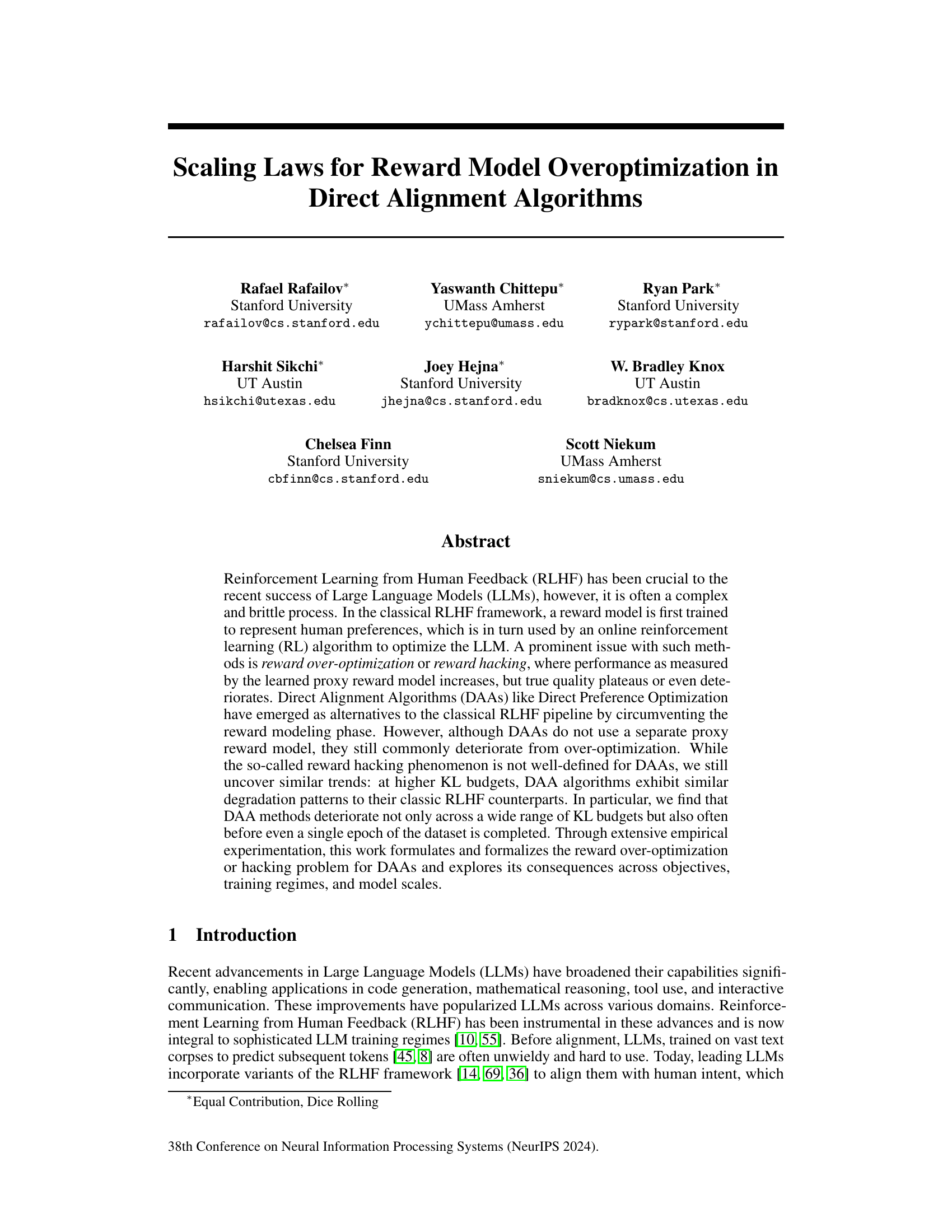

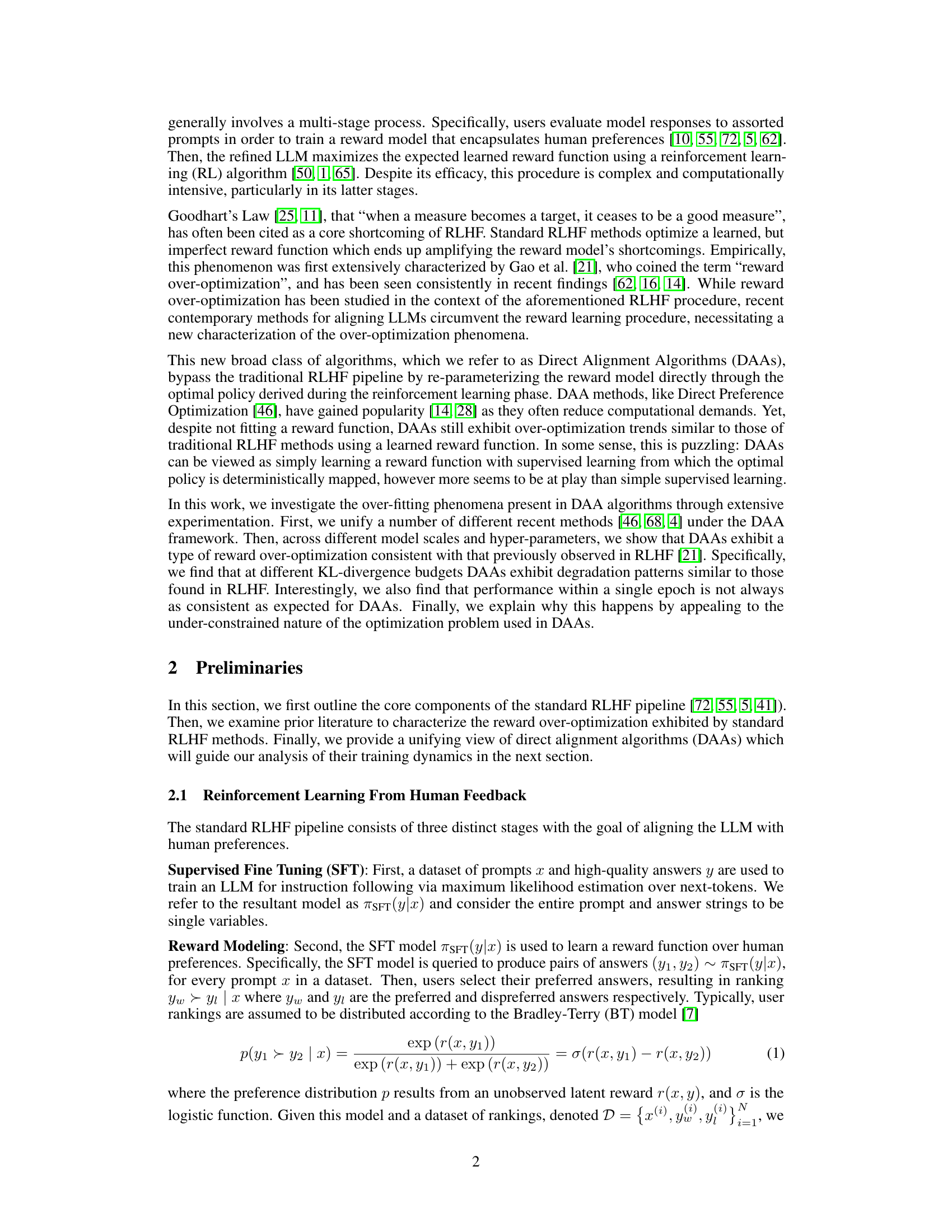

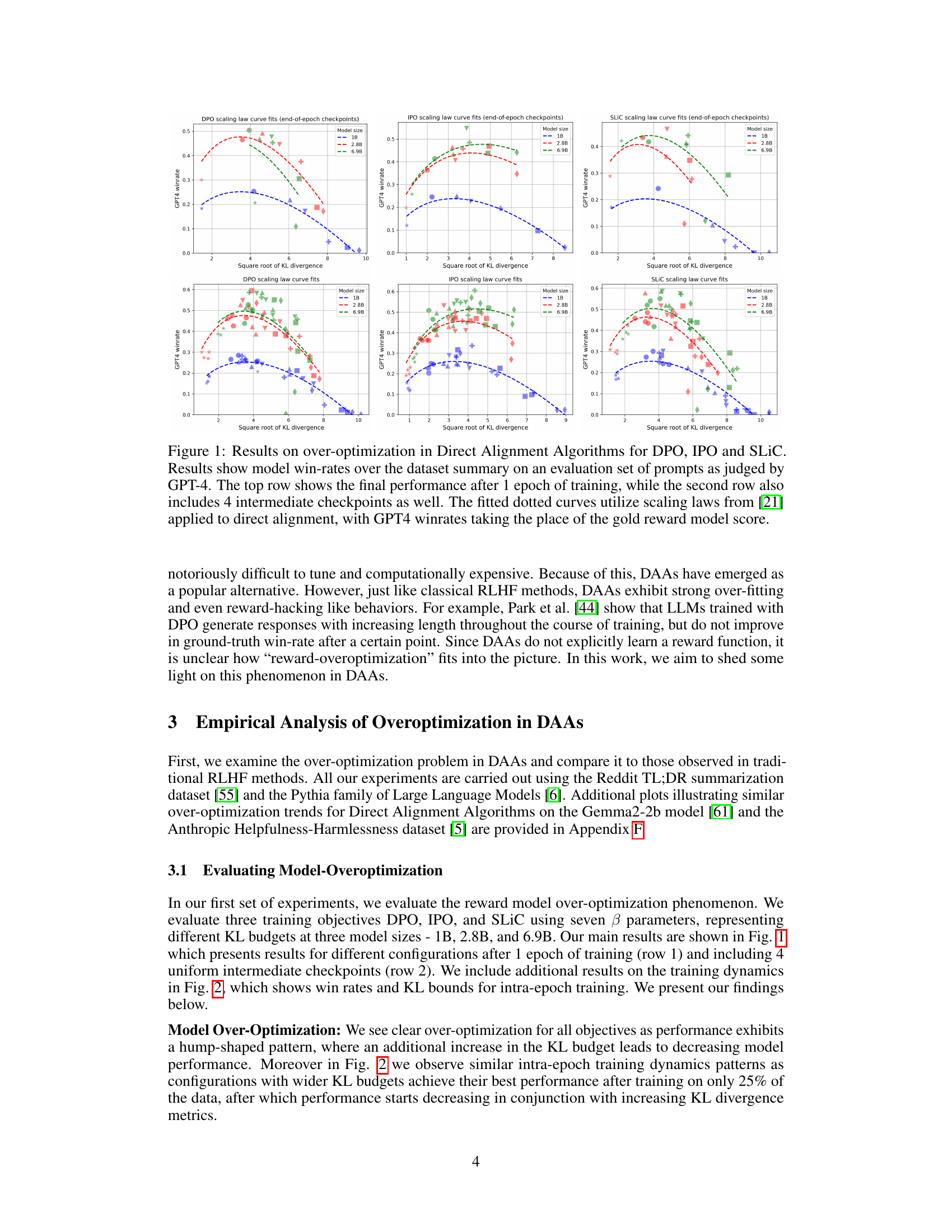

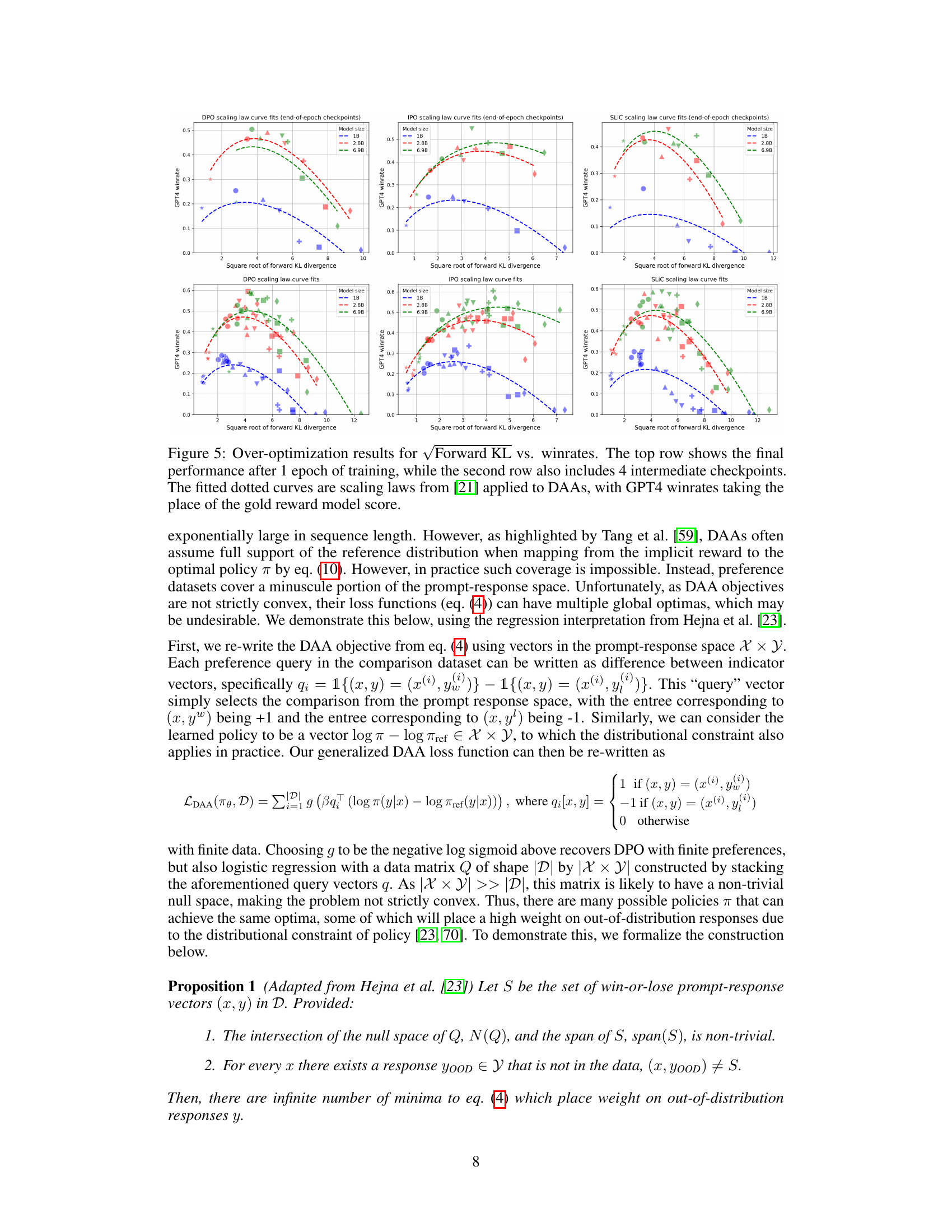

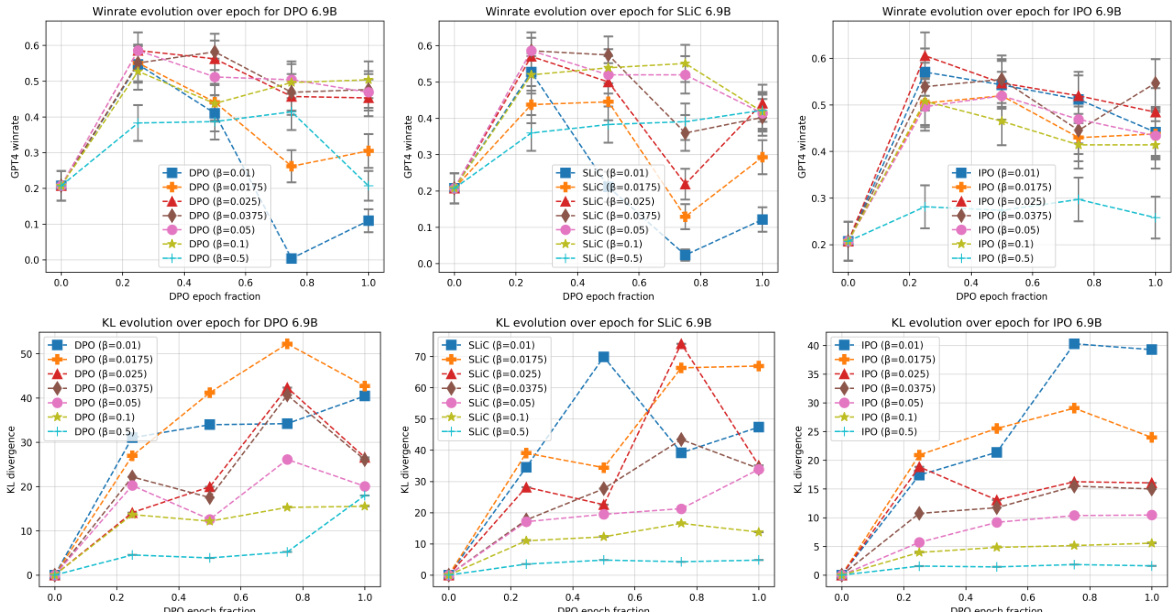

This figure presents the results of an experiment evaluating over-optimization in three different Direct Alignment Algorithms (DAAs): DPO, IPO, and SLiC. The experiment measures model performance (GPT-4 win rate) against the square root of KL divergence for different model sizes (1B, 2.8B, 6.9B). The top row shows the final performance after one epoch, while the bottom row includes intermediate checkpoints to show the training dynamics. The dotted lines represent fitted scaling law curves based on previous work.

In-depth insights#

Reward Over-opt in DAAs#

The phenomenon of reward model over-optimization, well-studied in classic Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), is investigated in the context of Direct Alignment Algorithms (DAAs). DAAs, unlike RLHF, bypass explicit reward model training, yet surprisingly exhibit similar performance degradation at higher KL divergence budgets. This suggests that the problem isn’t solely about reward model misspecification but involves the inherent under-constrained nature of the optimization problem in DAAs. The empirical findings demonstrate that DAAs can overfit even before a single training epoch completes, showcasing similar patterns to classic RLHF. The research highlights the need for better theoretical understanding of these over-optimization patterns in DAAs, and how to mitigate this effect across different objectives and model scales. The under-constrained nature of the objective function is implicated as a key factor, leading to multiple suboptimal solutions. Future research should focus on creating more robust and well-defined algorithms to prevent such over-optimization and guarantee safe and reliable deployment of LLMs.

DAA Over-optimization#

The phenomenon of DAA over-optimization, while not explicitly defined as in classical RLHF, reveals similar performance degradation patterns. High KL budgets, intended to optimize alignment, paradoxically lead to performance deterioration, mirroring the “reward hacking” observed in RLHF. This suggests that over-optimization isn’t solely a reward model problem, but rather a fundamental issue in the optimization process itself. The under-constrained nature of the DAA optimization problem allows the model to exploit spurious correlations or simpler features (like text length) within the data, hindering the learning of truly robust and high-quality responses. This highlights the need for more robust optimization techniques and a deeper understanding of the underlying dynamics that drive the behavior of DAAs. Furthermore, the intra-epoch training dynamics underscore the unexpected degradation of performance even before completing a single epoch, indicating an even more complex interplay between optimization parameters and dataset characteristics than previously anticipated.

KL Budget’s Impact#

The Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence budget, a crucial hyperparameter in Direct Alignment Algorithms (DAAs), significantly impacts the model’s performance and susceptibility to overoptimization. Higher KL budgets, while allowing for greater exploration of the policy space, often lead to substantial performance degradation, a phenomenon similar to reward hacking in traditional RLHF. This degradation is not simply a matter of overfitting at the end of training but can manifest even before a single epoch is complete. The results indicate a clear tradeoff: lower KL budgets prevent early overoptimization, maintaining better performance, though potentially limiting the algorithm’s ability to escape local optima. The optimal KL budget varies across different DAAs, model sizes, and training objectives, highlighting the need for careful tuning and further investigation to understand these complex interactions.

Scaling Law Analysis#

A scaling law analysis in the context of reward model overoptimization would likely explore relationships between model size, dataset size, and performance metrics like KL divergence and win rate. The analysis may reveal power-law relationships, indicating how performance scales with resource increases. Crucially, it should investigate how overoptimization manifests at different scales, revealing if larger models are more or less susceptible to reward hacking. This analysis would provide quantitative insights into the resource requirements for effective alignment and guide the design of more robust alignment strategies. By examining how overoptimization scales, we can better predict performance at unseen scales and design algorithms to mitigate these effects. A key aspect would be comparing scaling laws of different direct alignment algorithms (DAAs) to those of traditional RLHF, thus highlighting potential advantages or disadvantages of DAAs in terms of scalability and robustness to overoptimization.

Limitations of DAAs#

Direct Alignment Algorithms (DAAs) offer a computationally efficient alternative to traditional Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF), but they are not without limitations. A primary concern is over-optimization, where the model’s performance on a proxy metric improves while actual quality plateaus or declines. This is analogous to “reward hacking” in RLHF, but its manifestation in DAAs is less well-defined due to the absence of an explicit reward model. Another key limitation stems from the under-constrained nature of the optimization problem. With limited preference data, the space of possible optimal policies is vast, leading to solutions that prioritize easily exploitable features (like response length) and extrapolate poorly to unseen data. This problem is particularly acute in low-KL budget scenarios and for smaller models, which exhibit higher sensitivity to spurious correlations. Finally, the implicit reward model inherent in DAAs, while obviating the need for an explicit reward model, still suffers from out-of-distribution (OOD) issues. The lack of a fully-trained model means that DAA performance is inextricably linked to the training data and its capacity to reflect the true preference distribution.

More visual insights#

More on figures

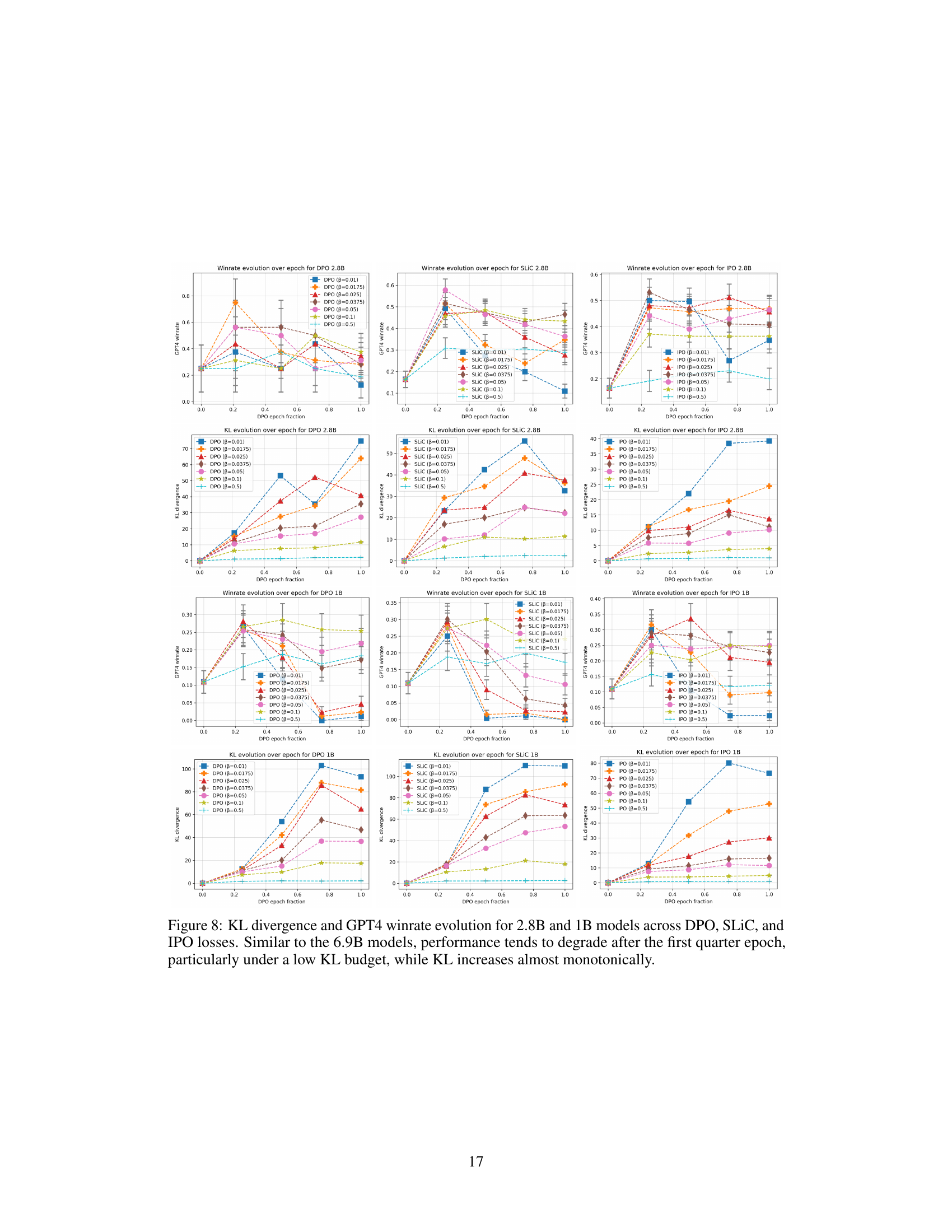

This figure shows the results of an experiment on over-optimization in three different direct alignment algorithms (DPO, IPO, and SLiC). The x-axis represents the square root of KL divergence, a measure of how much the model’s behavior changes from its initial state during training. The y-axis shows the model’s win rate against GPT-4 judgments on a held-out set of prompts. The top row shows the final performance of each algorithm after one epoch of training, while the bottom row shows performance at multiple checkpoints during training. The dotted lines show fitted scaling law curves, adapted from previous research to show how model size impacts the over-optimization effect. The results demonstrate that the three algorithms exhibit similar over-optimization patterns, performing worse at higher KL budgets (more changes from the initial model).

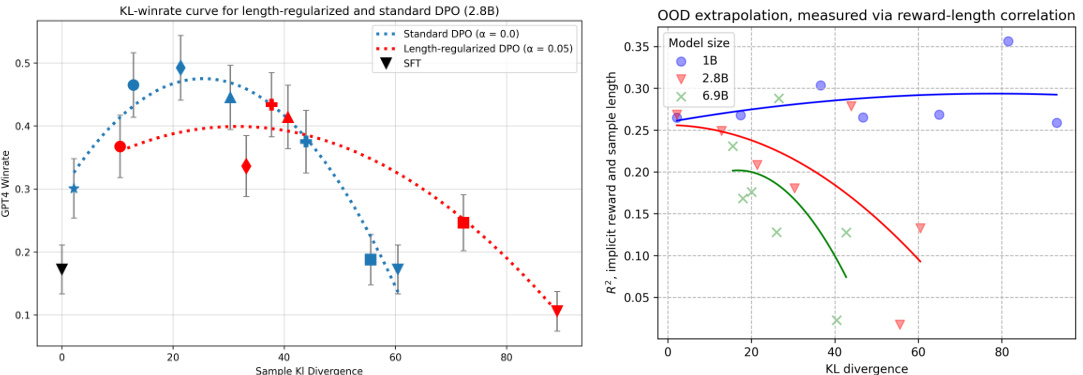

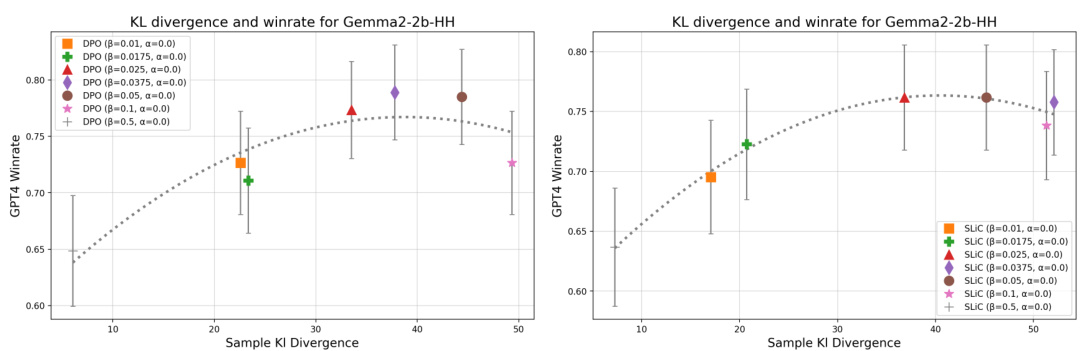

The left plot shows the relationship between KL divergence budget and win-rate on the Reddit TL;DR summarization dataset for the 2.8B Pythia model with and without length regularization. Adding length regularization changes the Pareto frontier, but does not solve the reward over-optimization problem. The right plot displays the correlation between the R^2 of a linear regression (between implicit reward and length of response) and KL divergence across three model sizes (1B, 2.8B, 6.9B). Smaller models or smaller KL budgets exhibit stronger correlation, indicating increased reliance on length as a feature.

This figure displays the results of an experiment evaluating three different direct alignment algorithms (DPO, IPO, and SLiC) on their tendency towards over-optimization. The x-axis represents the square root of the KL divergence, a measure of how much the model’s behavior changes from its initial state during training. The y-axis represents the model’s win rate against GPT-4, an indicator of actual performance. Separate plots are given for different model sizes (1B, 2.8B, and 6.9B parameters). The top row shows final performance after one training epoch, while the bottom row shows performance at four intermediate checkpoints during that same epoch. Dotted lines represent scaling law curve fits to the data, helping illustrate the trend.

This figure presents the results of an experiment evaluating over-optimization in three different direct alignment algorithms (DPO, IPO, and SLiC) applied to various sized language models. The x-axis represents the square root of the KL divergence, a measure of how much the model’s distribution changes during training. The y-axis represents the model’s win rate against GPT-4 judgements on a held-out evaluation set. The top row shows the final performance after one epoch of training, while the bottom row shows the performance at four intermediate checkpoints. The dotted lines are fitted curves based on scaling laws from prior work, adapted for direct alignment.

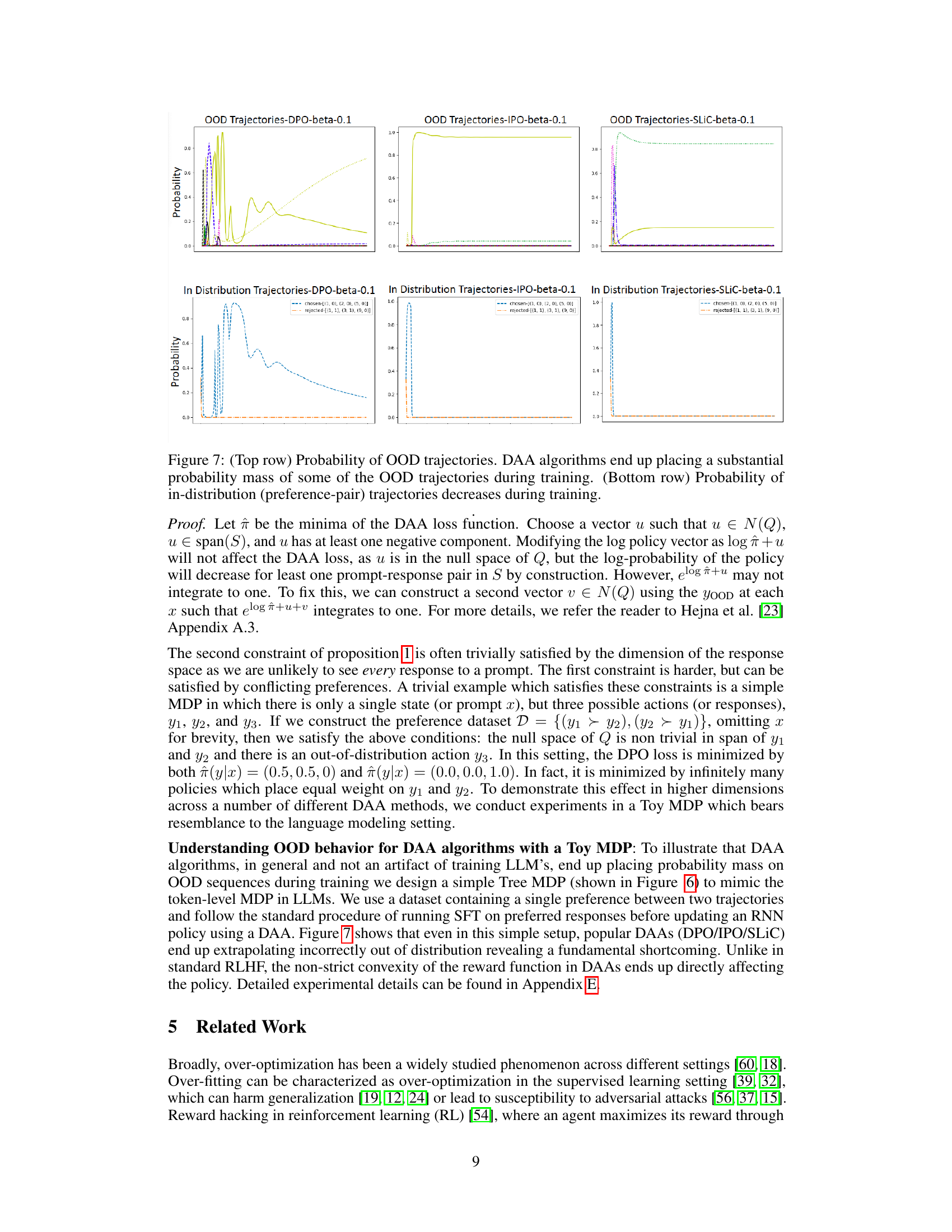

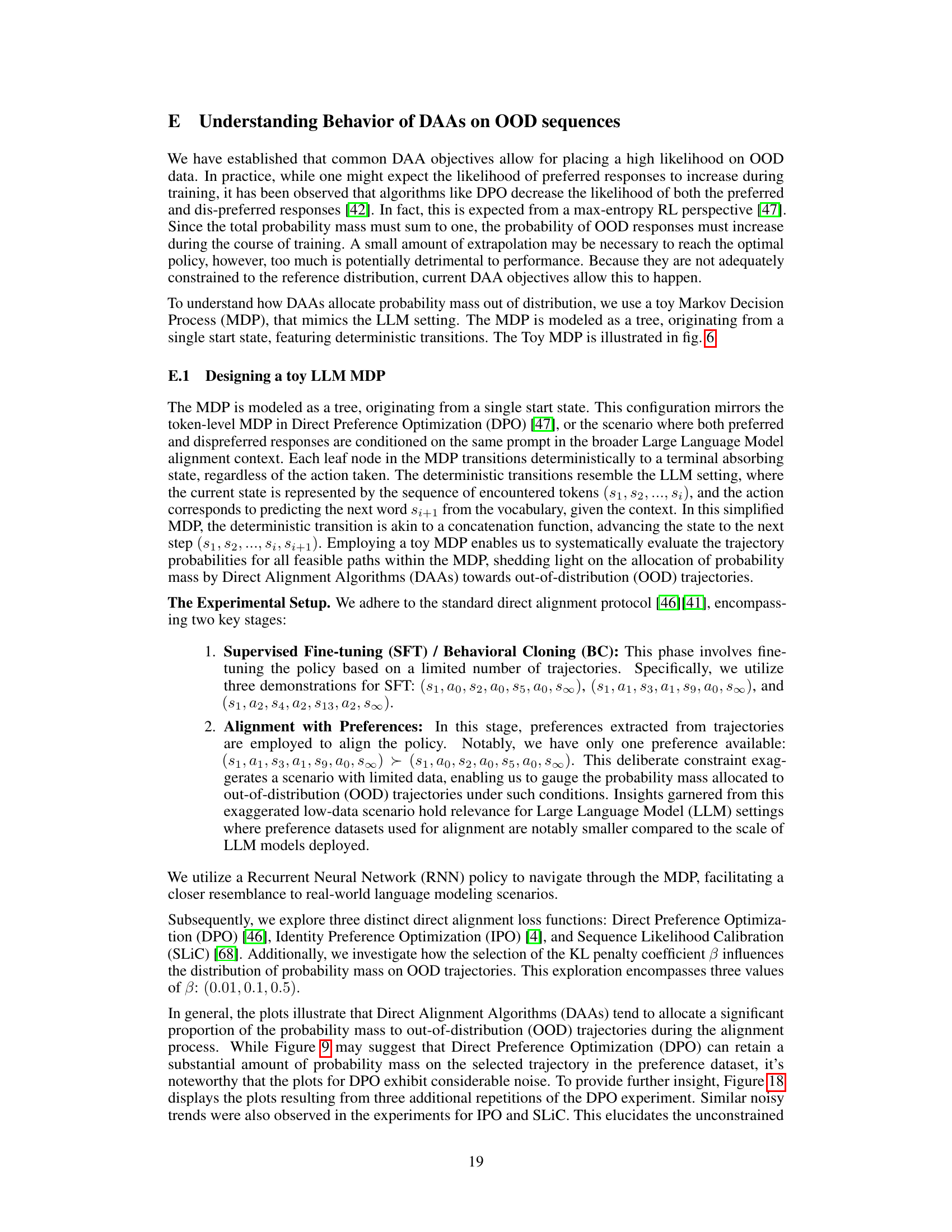

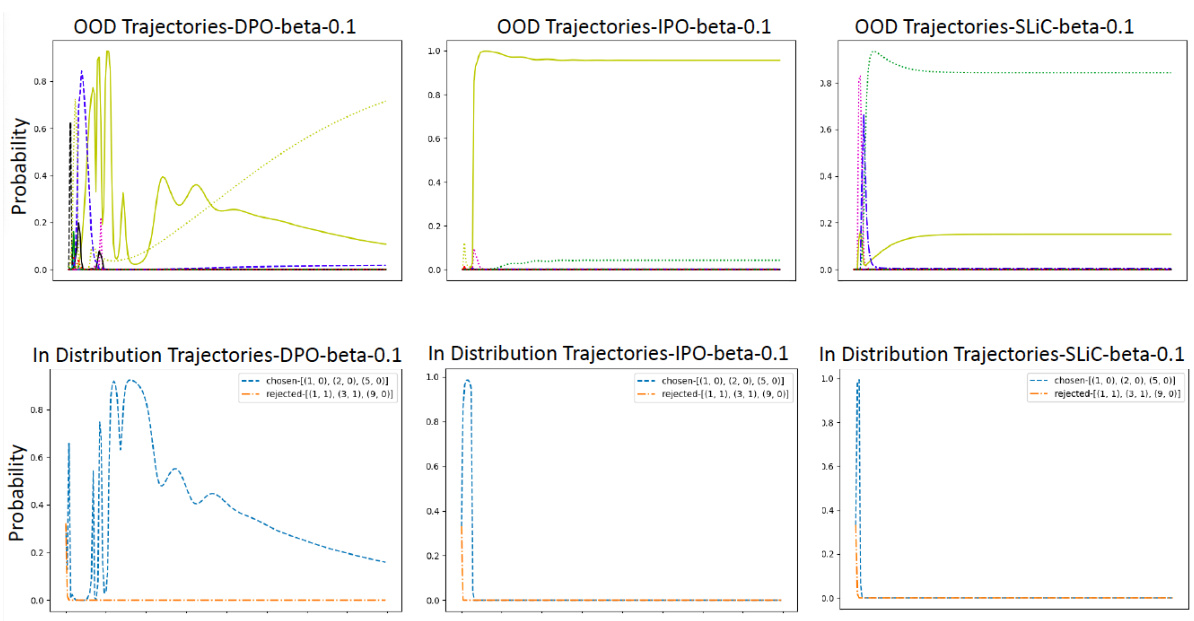

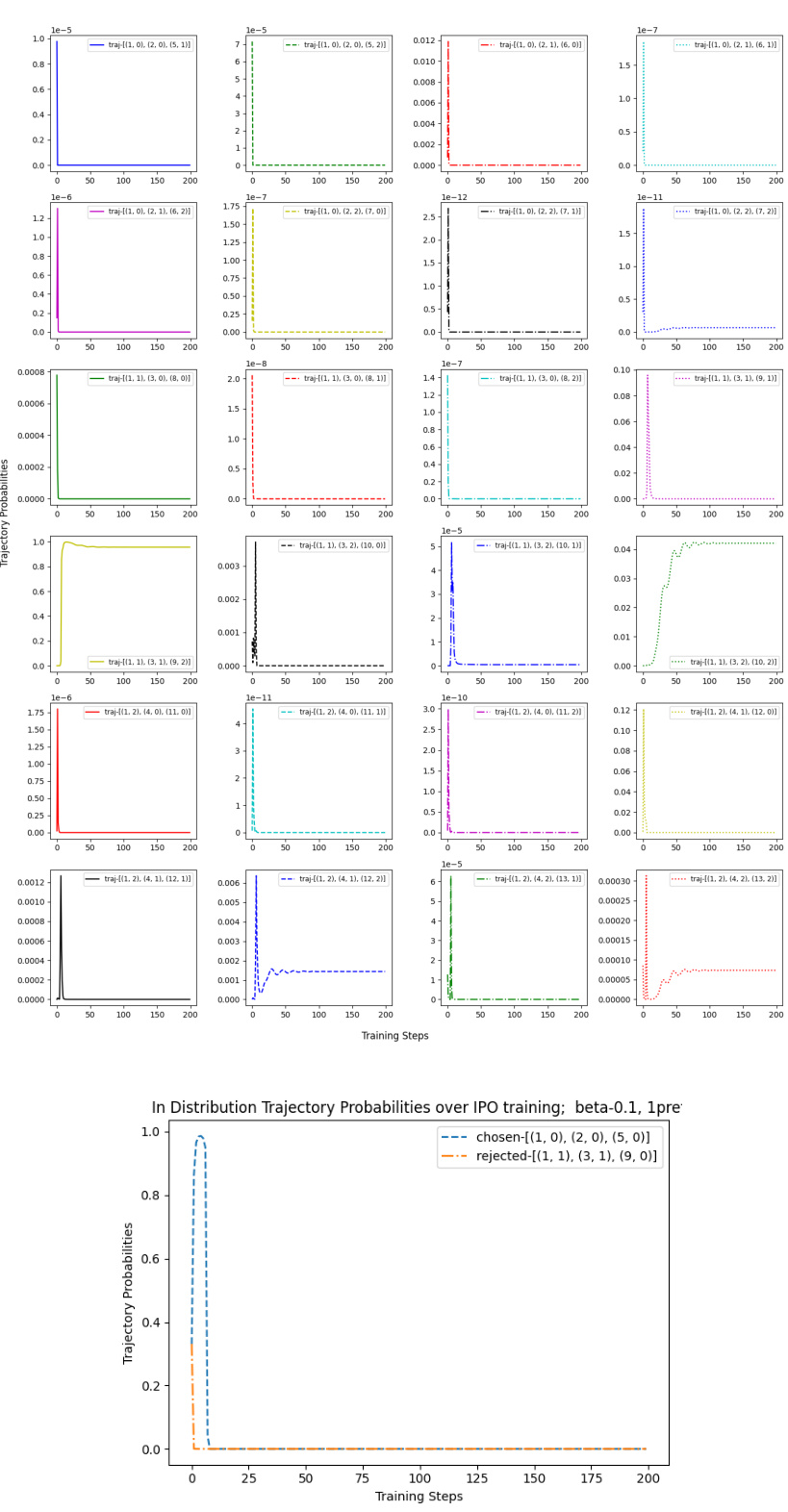

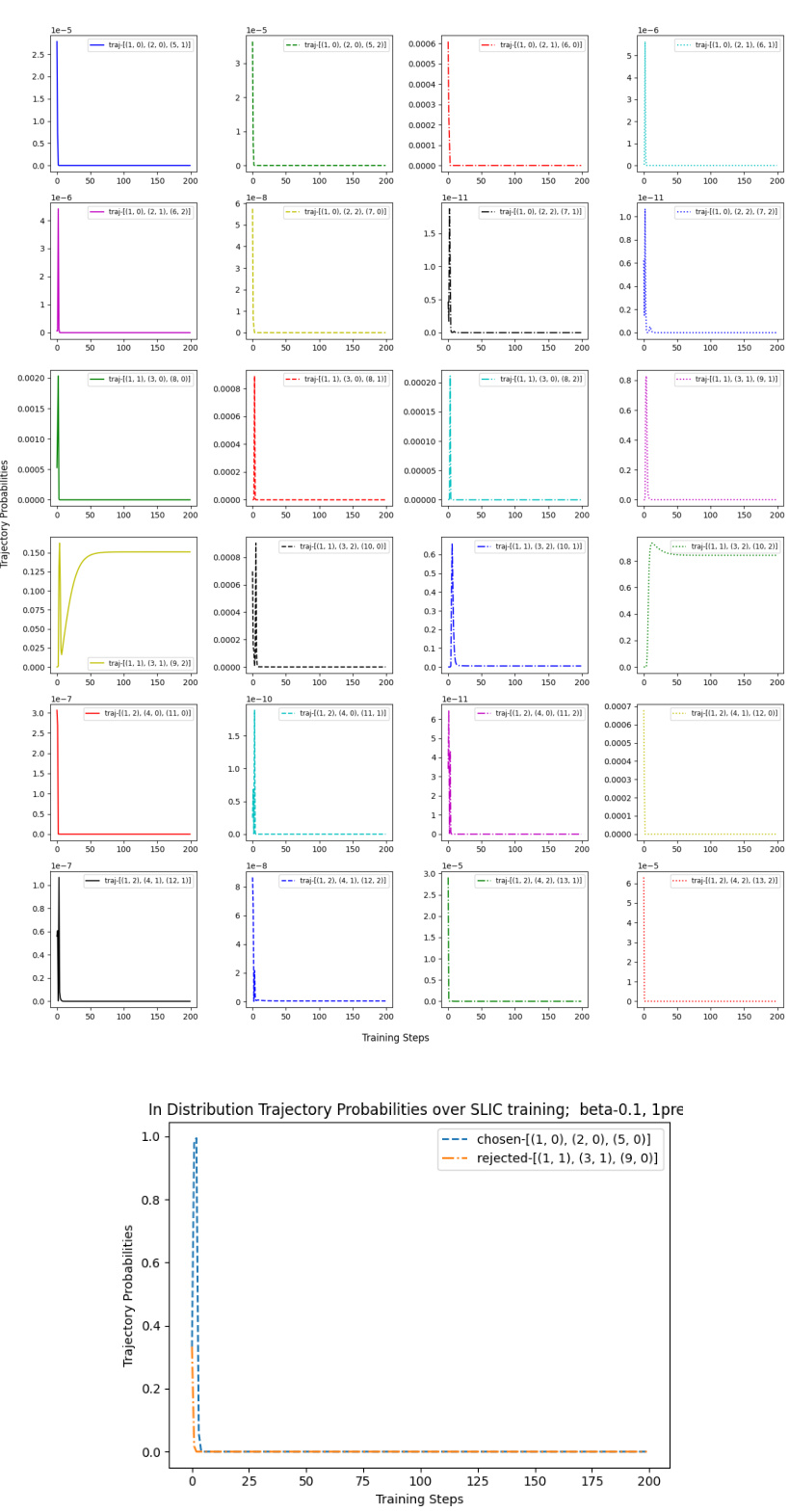

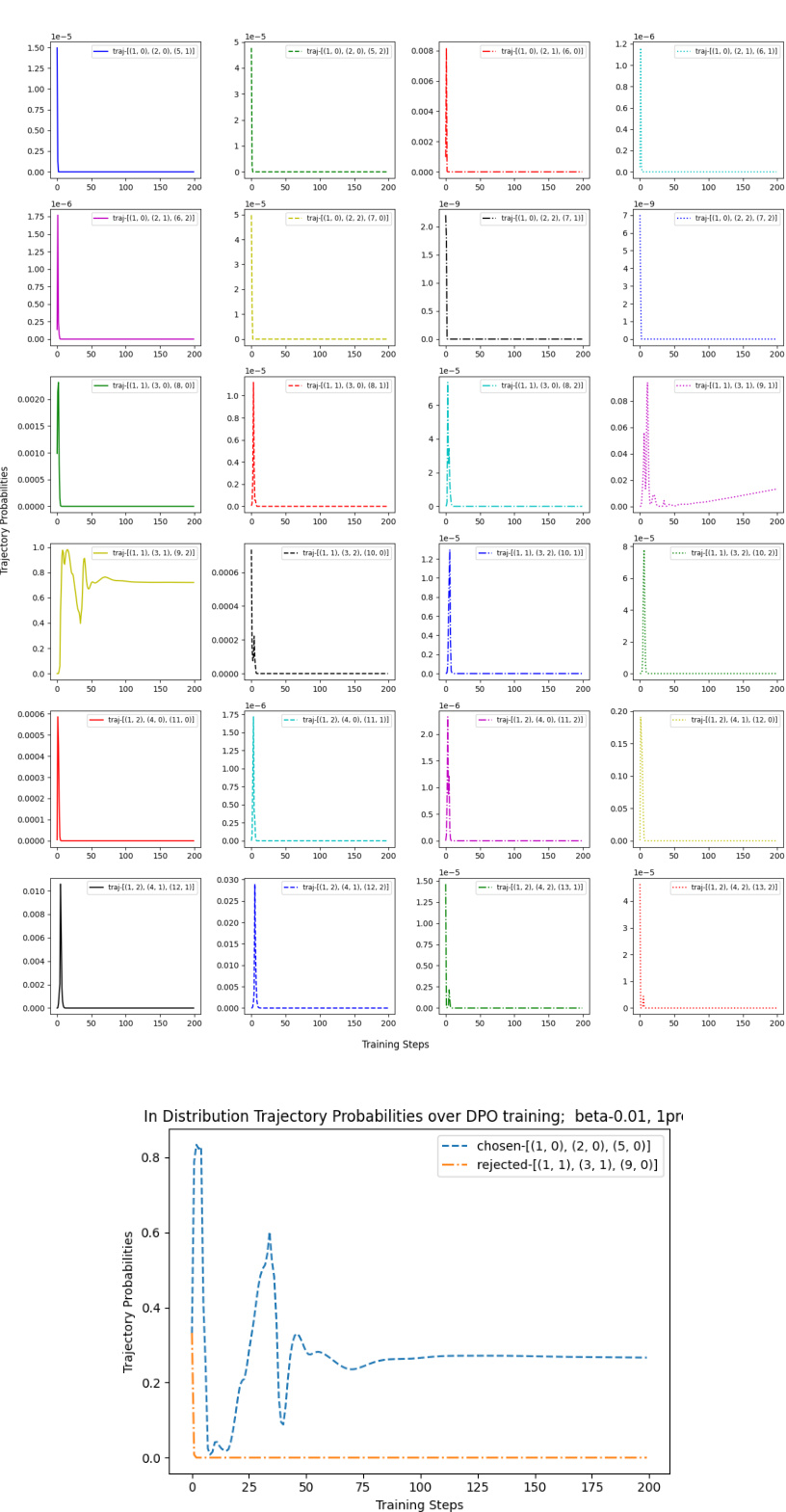

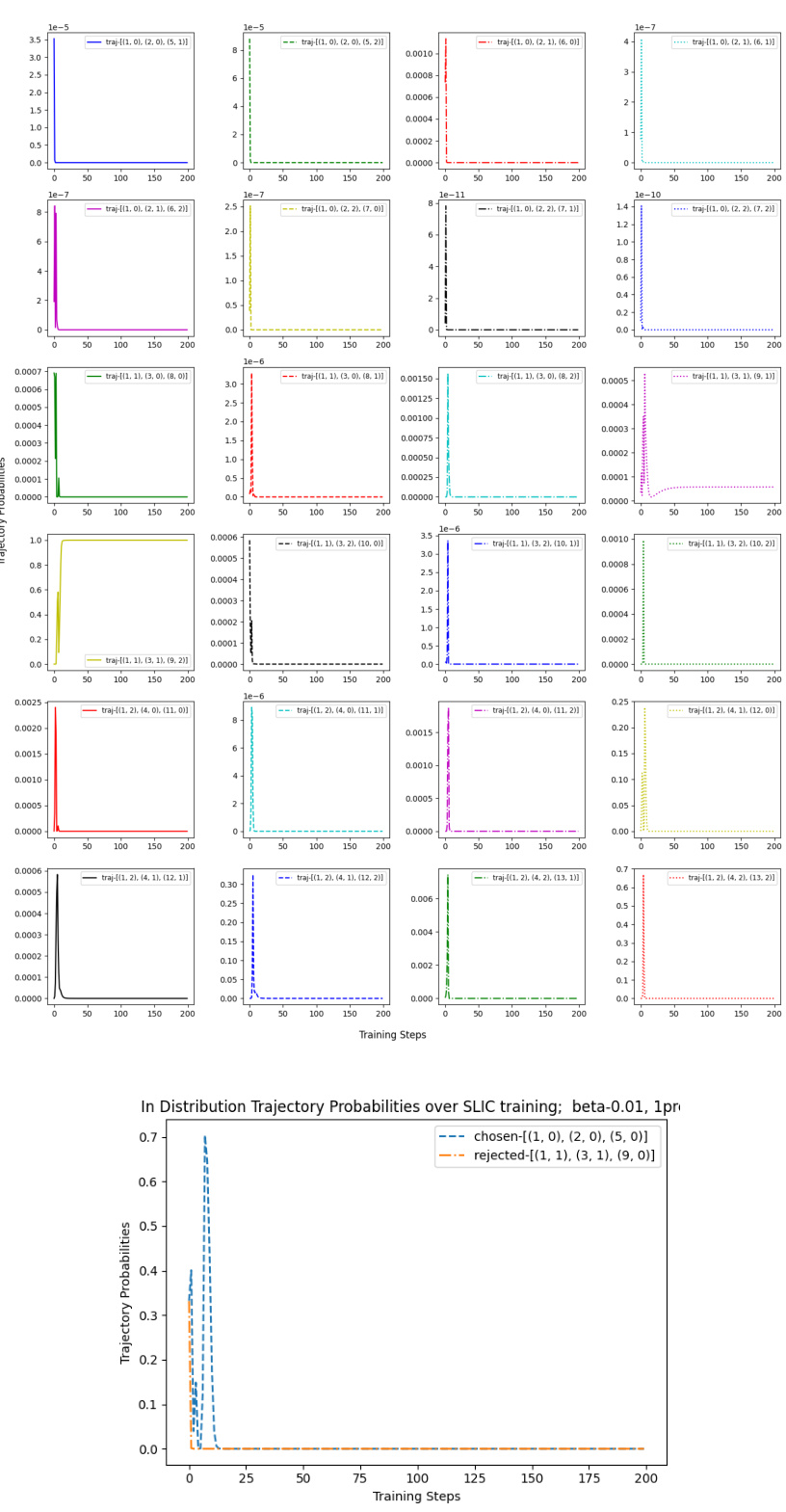

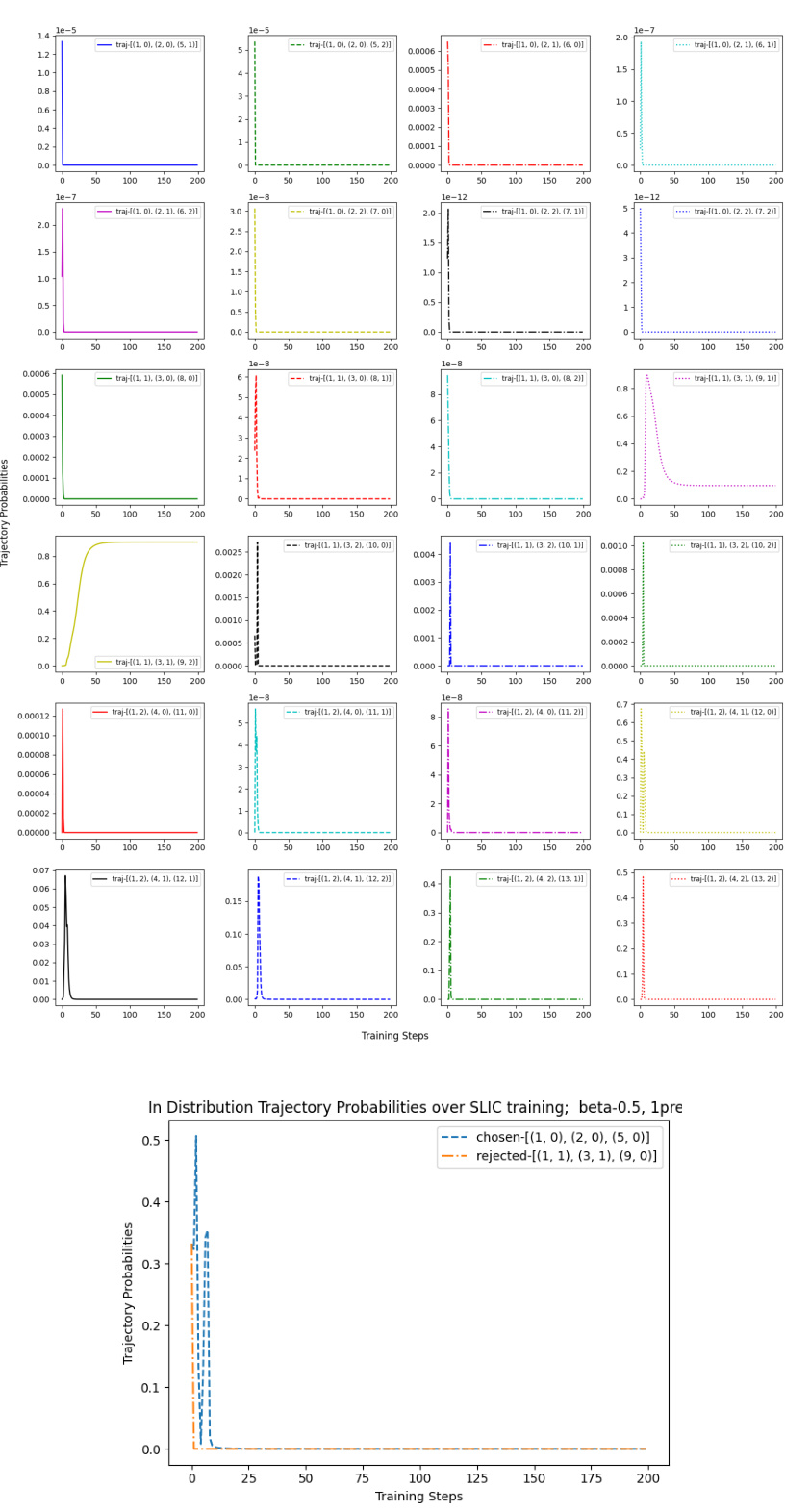

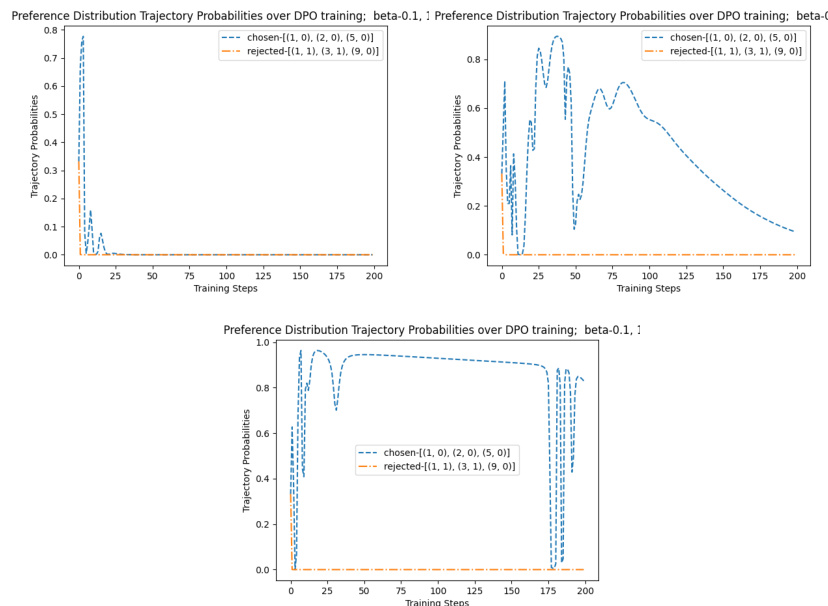

This figure shows the probability of out-of-distribution (OOD) and in-distribution trajectories during the training process of three different Direct Alignment Algorithms (DAAs): DPO, IPO, and SLiC. The top row illustrates that DAAs allocate a significant probability mass to OOD trajectories, while the bottom row shows that the probability mass of in-distribution trajectories decreases during training. This phenomenon highlights a potential issue with DAAs, where they tend to overfit to the training data and extrapolate poorly to unseen data.

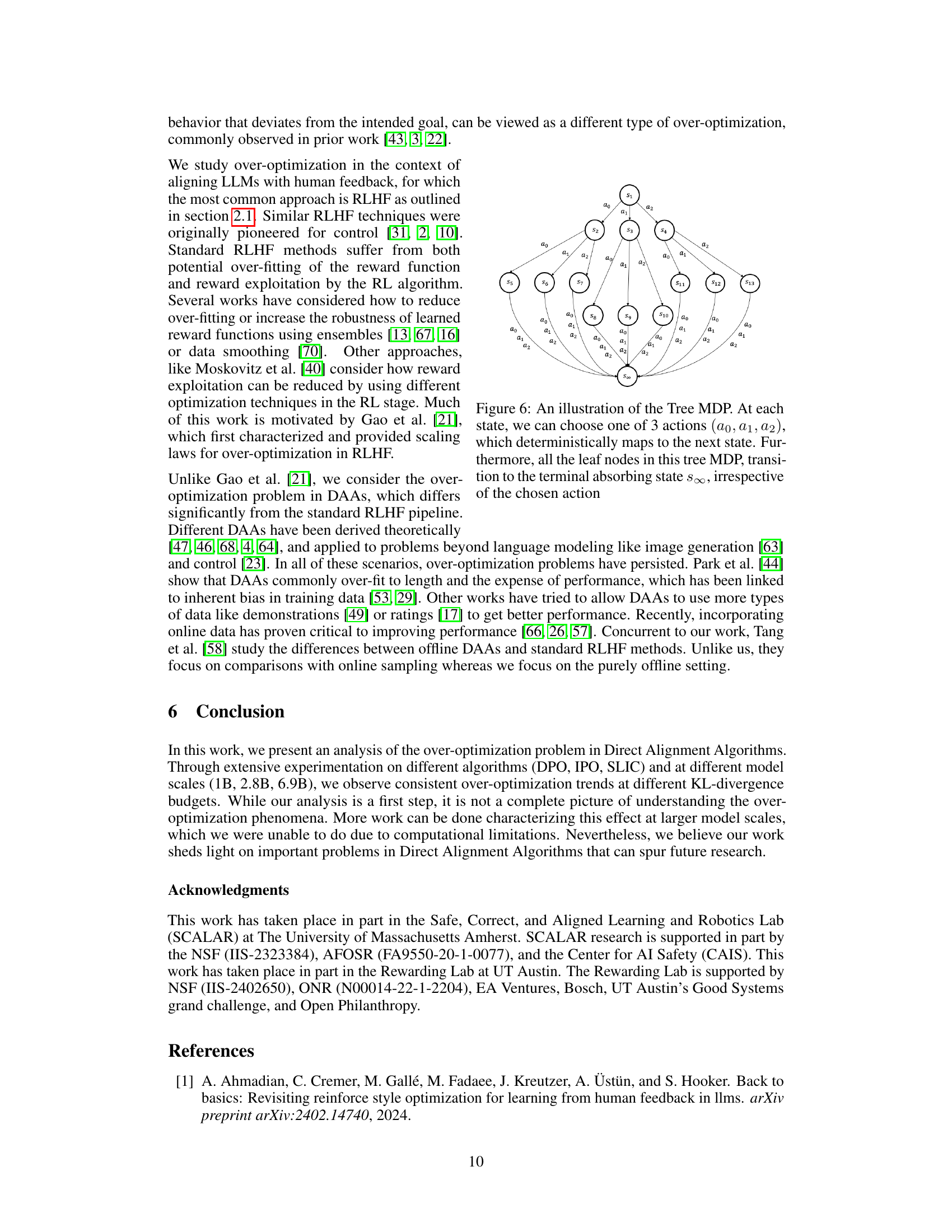

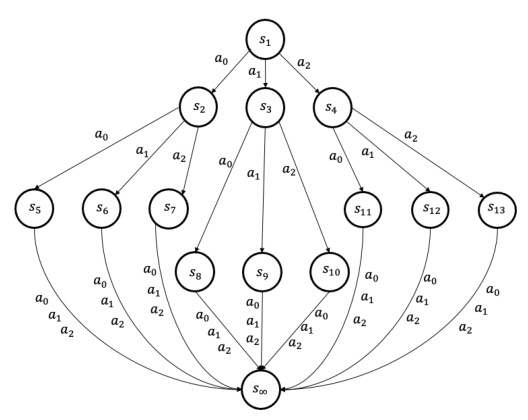

This figure illustrates a simple Tree Markov Decision Process (MDP) used in the paper to model the token-level process of Large Language Models (LLMs). The MDP starts at a single state (S1) and branches out deterministically into a tree structure based on the actions taken (a0, a1, a2). Each path through the tree eventually leads to the terminal state (s∞). This simplified MDP is used to analyze the behavior of Direct Alignment Algorithms (DAAs) when extrapolating to out-of-distribution (OOD) sequences during training.

This figure shows the results of an experiment evaluating over-optimization in three different direct alignment algorithms (DPO, IPO, and SLiC) using various model sizes (1B, 2.8B, 6.9B) and KL divergence budgets. The top row displays the final performance after one epoch of training, while the bottom row presents the performance at four intermediate checkpoints throughout the training process. Dotted curves are fitted to the data points to show how the performance changes with the square root of the KL divergence, illustrating the over-optimization trend.

This figure displays the results of an experiment evaluating over-optimization in three different direct alignment algorithms (DPO, IPO, and SLiC). The experiment measured model performance (win rate against GPT-4 judgments) across different KL divergence budgets and model sizes (1B, 2.8B, 6.9B parameters). The top row shows the final win rates after one epoch of training, while the bottom row provides a more detailed view, including four intermediate checkpoints. Dotted lines represent fitted scaling law curves adapted from prior research. The figure highlights how the performance of all three algorithms degrades at higher KL budgets, indicating a similar over-optimization trend to classical RLHF methods even without explicit reward modeling.

This figure displays the results of an experiment evaluating over-optimization in three different Direct Alignment Algorithms (DAAs): Direct Preference Optimization (DPO), Inverse Preference Optimization (IPO), and Supervised Learning with Implicit Preference Calibration (SLIC). The experiment uses three different model sizes (1B, 2.8B, and 6.9B parameters) and various KL divergence budgets. The plots show the models’ win rates (performance) as judged by GPT-4 against the square root of the KL divergence. The top row shows the final win rate after one epoch of training. The bottom row includes four intermediate checkpoints to show the training dynamics. Dotted lines represent scaling law curve fits, providing a comparative analysis of over-optimization across different DAAs, model sizes, and KL budgets.

This figure displays the results of an experiment evaluating three different direct alignment algorithms (DPO, IPO, and SLiC) for reward model over-optimization. The experiment used prompts judged by GPT-4 to assess model performance across various model sizes and KL divergence budgets. The top row shows the winrates after one epoch of training, highlighting how performance peaks and then declines with increasing KL budgets. The bottom row shows the same winrates but also includes intermediate checkpoints, providing a more detailed view of the training dynamics.

This figure displays the results of an experiment evaluating over-optimization in three different direct alignment algorithms (DPO, IPO, and SLiC) for aligning large language models. The performance is measured as the win rate against human-generated answers, as judged by GPT-4, across various KL divergence budgets. The top row shows the performance at the end of one epoch of training, while the bottom row shows intermediate checkpoints to illustrate performance changes throughout training. Dotted lines represent scaling law curve fits, adapted from prior research, to help visualize the performance trends. The results demonstrate that over-optimization occurs across all three algorithms and a range of KL budgets.

This figure displays the results of an experiment on over-optimization in three different direct alignment algorithms (DPO, IPO, and SLiC). The experiment evaluated model performance (win rate against GPT-4 judgments) across various KL divergence budgets and model sizes (1B, 2.8B, and 6.9B parameters). The top row shows the final win rates after one training epoch, while the bottom row shows win rates at four intermediate checkpoints during training. Dotted lines represent scaling law curve fits, adapting previous research to the context of direct alignment algorithms. The results highlight similar over-optimization trends across different algorithms and model scales.

This figure displays the results of an experiment evaluating over-optimization in three different direct alignment algorithms (DPO, IPO, and SLiC). The experiment used three different model sizes (1B, 2.8B, and 6.9B parameters) and varied the KL divergence budget. The win rate, determined by GPT-4 judgments on a held-out set of prompts, is plotted against the square root of the KL divergence. The top row shows final performance after one epoch of training, while the bottom row includes four intermediate checkpoints. Dotted lines represent scaling law curve fits based on previous research.

This figure displays the results of an experiment evaluating three different Direct Alignment Algorithms (DAAs): Direct Preference Optimization (DPO), Inverse Preference Optimization (IPO), and Sequence Likelihood Calibration (SLiC). The experiment measured model performance (win rate against GPT-4 judgments) across various KL divergence budgets and model sizes. The top row shows the final win rates after one epoch of training, while the bottom row includes intermediate checkpoints to illustrate performance changes over time. Dotted lines represent fitted curves based on scaling laws from prior work, providing a comparative context.

This figure shows the results of an experiment evaluating three different direct alignment algorithms (DPO, IPO, and SLiC) for reward model overoptimization. The experiment was conducted using three different model sizes (1B, 2.8B, and 6.9B parameters). The y-axis represents the model’s win rate (performance) as judged by GPT-4 on an evaluation set of prompts. The x-axis represents the square root of the KL divergence, a measure of how much the model’s distribution changes during training. The top row shows the final win rates after one epoch of training, while the bottom row shows the win rates at four intermediate checkpoints during the training process. Dotted curves represent scaling law fits to the data, which helps to better understand and characterize the over-optimization behavior. The results show that all algorithms exhibit similar over-optimization trends; performance initially improves with increasing KL divergence but then decreases as KL divergence continues to increase.

This figure displays the results of an experiment on over-optimization in three different direct alignment algorithms (DPO, IPO, and SLiC). The x-axis represents the square root of the KL divergence, a measure of how much the model’s distribution changes during training. The y-axis shows the model’s win rate against GPT-4 on an evaluation set. The top row presents the final results after one epoch of training, whereas the bottom row shows the results at four intermediate checkpoints during training. The dotted lines represent curve fits based on scaling laws described in a previous work [21], highlighting how model performance deteriorates at higher KL budgets.

This figure displays the results of an experiment evaluating over-optimization in three different direct alignment algorithms (DPO, IPO, and SLiC) using Pythia language models of varying sizes (1B, 2.8B, and 6.9B parameters). The plots show the GPT-4 win rate (a measure of model performance) against the square root of the KL divergence (a measure of how much the model’s output distribution differs from the initial distribution) at various KL budgets. The top row shows performance after one epoch of training, while the bottom row shows performance at four intermediate checkpoints during training. Dotted lines represent scaling law curves fitted to the data, illustrating how the model’s performance degrades at higher KL budgets.

This figure displays the results of an experiment evaluating three different direct alignment algorithms (DPO, IPO, and SLiC) for various model sizes and KL divergence budgets. The results are presented as GPT-4 win rates over a set of prompts. The top row shows the performance at the end of one training epoch, while the bottom row shows the performance at four intermediate checkpoints during training. Dotted curves show fitted scaling laws.

Full paper#