TL;DR#

Distributed minimax optimization is crucial for large-scale machine learning, but existing methods often struggle with communication bottlenecks and suboptimal performance. This is particularly true when dealing with problems involving many nodes and complex objective functions. The challenge lies in finding algorithms that balance communication efficiency with computational cost, especially under different assumptions on data similarity and function properties.

The paper introduces SVOGS, a novel algorithm designed to overcome these limitations. SVOGS uses mini-batch client sampling and variance reduction to achieve near-optimal communication complexity, communication rounds, and local gradient calls. The algorithm’s performance is rigorously analyzed, showing that its complexities nearly match theoretical lower bounds, highlighting its efficiency and effectiveness, especially under the assumption of second-order similarity among local functions.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it offers near-optimal distributed algorithms for a common machine learning problem. It bridges the gap between theory and practice by providing tight upper and lower bounds on computational complexity, addressing a key challenge in distributed optimization. This opens avenues for improving efficiency in large-scale machine learning applications and inspires further research into tight bound analysis for similar problems.

Visual Insights#

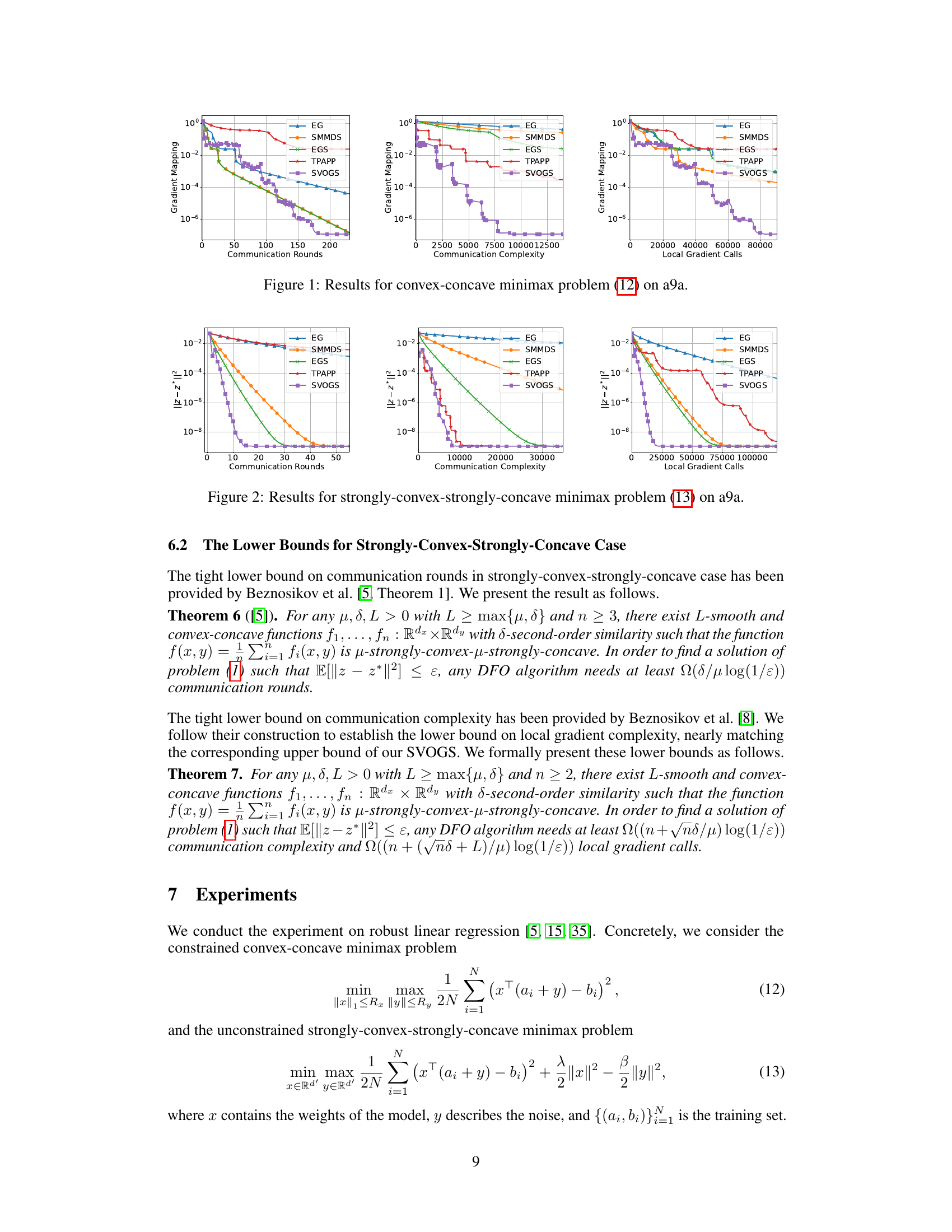

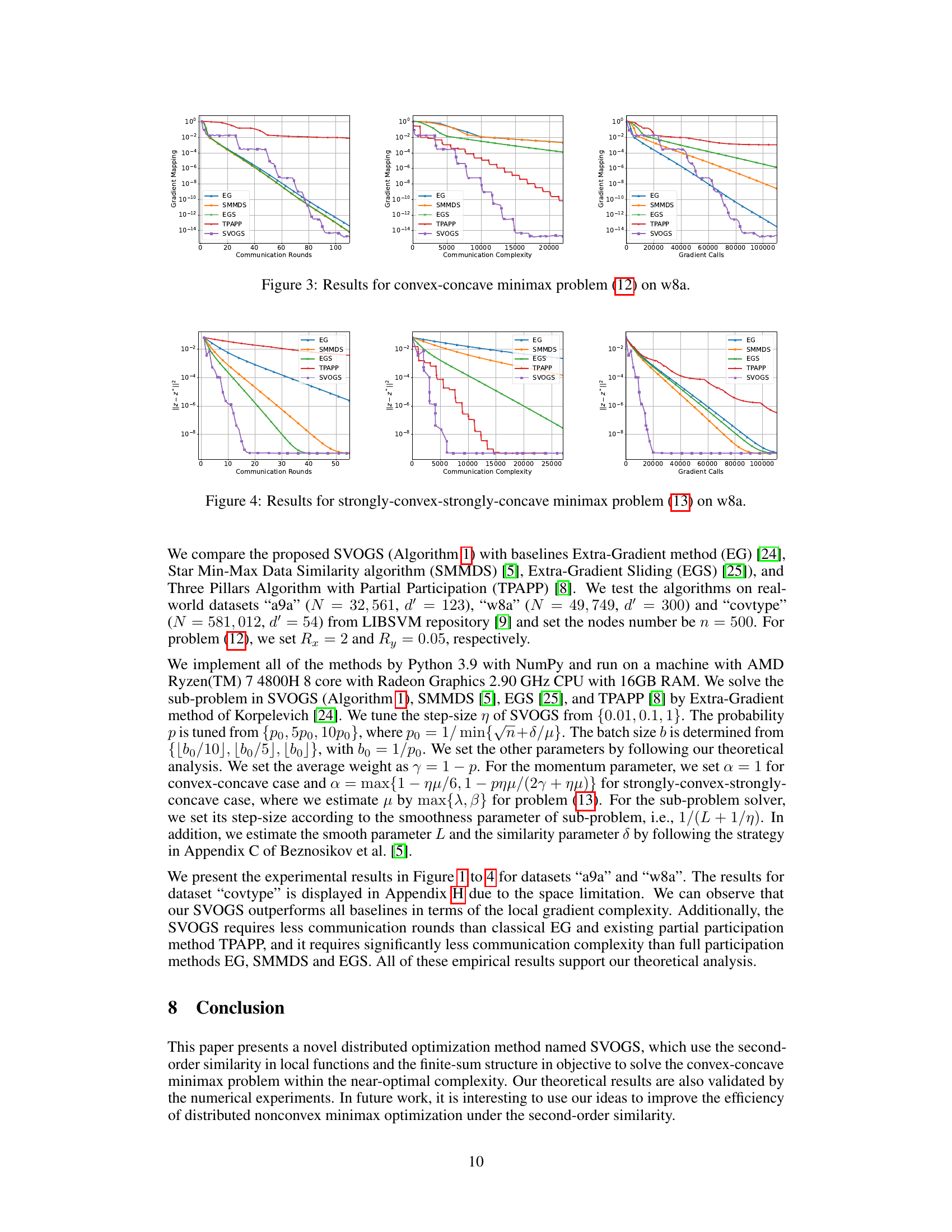

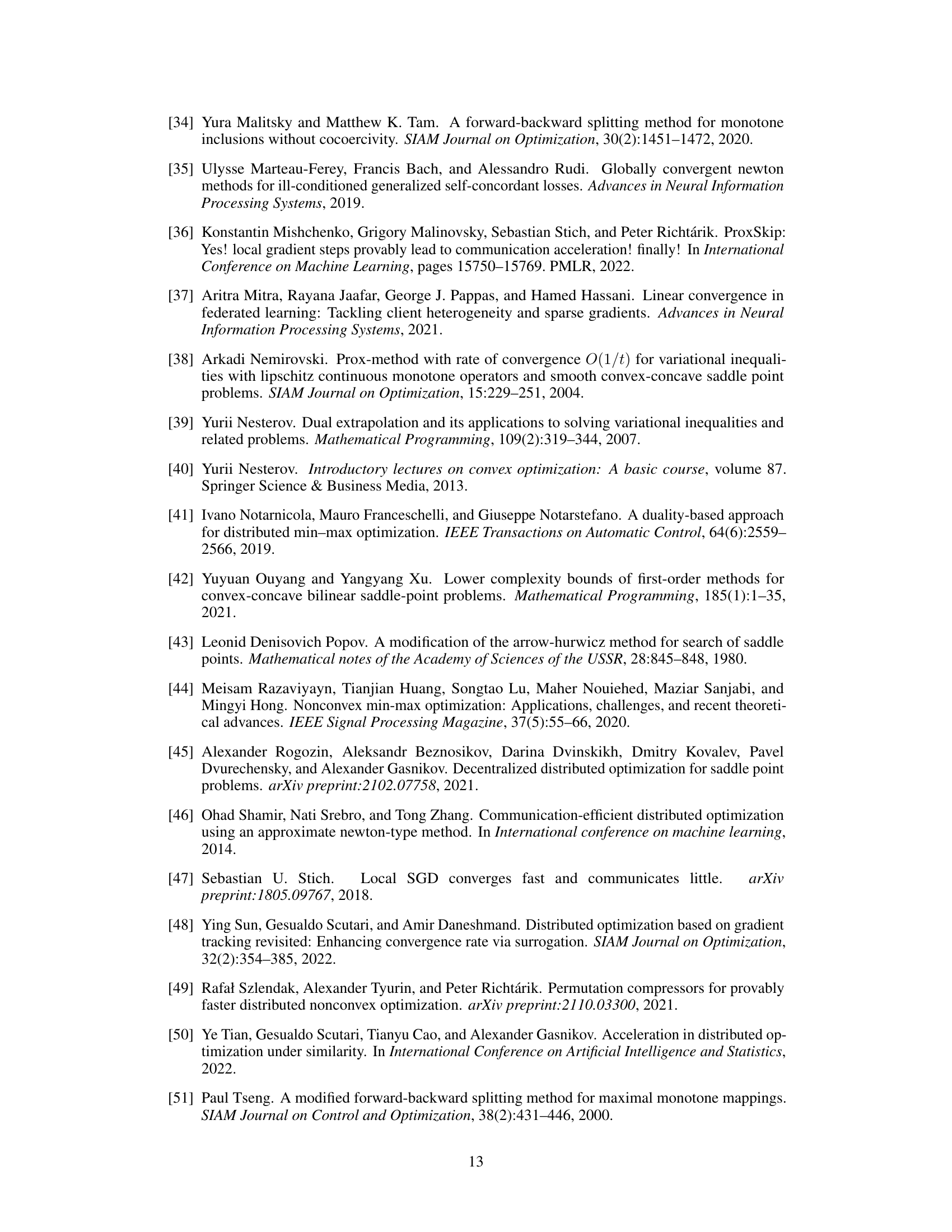

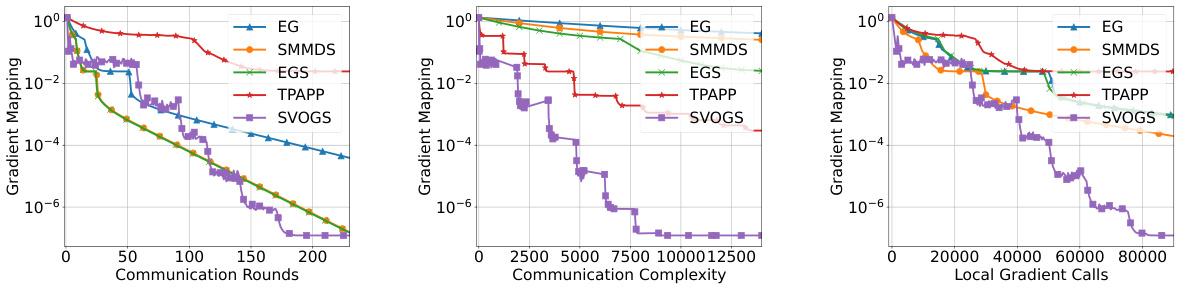

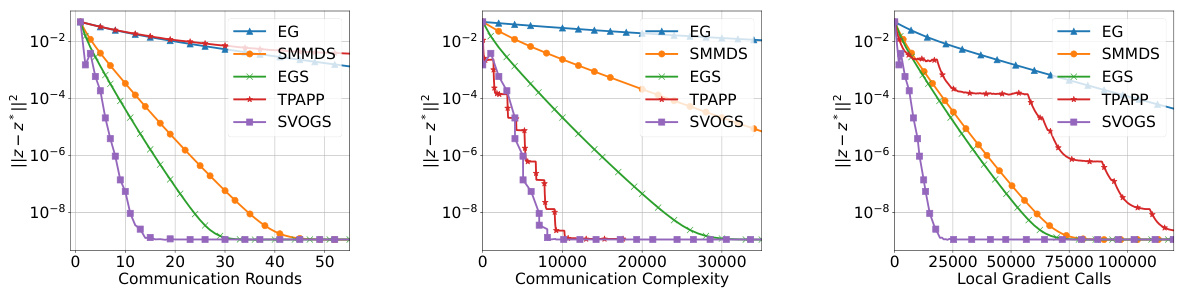

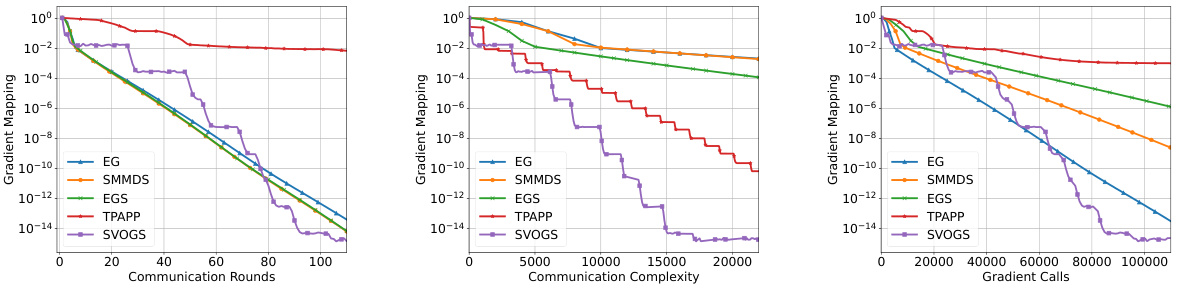

🔼 This figure presents the results of experiments conducted on the a9a dataset for solving a convex-concave minimax optimization problem. Three performance metrics are presented, Communication Rounds, Communication Complexity, and Local Gradient Calls. The performance of the proposed SVOGS method is compared against several other methods such as EG, SMMDS, EGS and TPAPP. The plots display how the gradient mapping decreases as a function of each performance metric. Each method’s performance is represented by a different colored line on the plot.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for convex-concave minimax problem (12) on a9a.

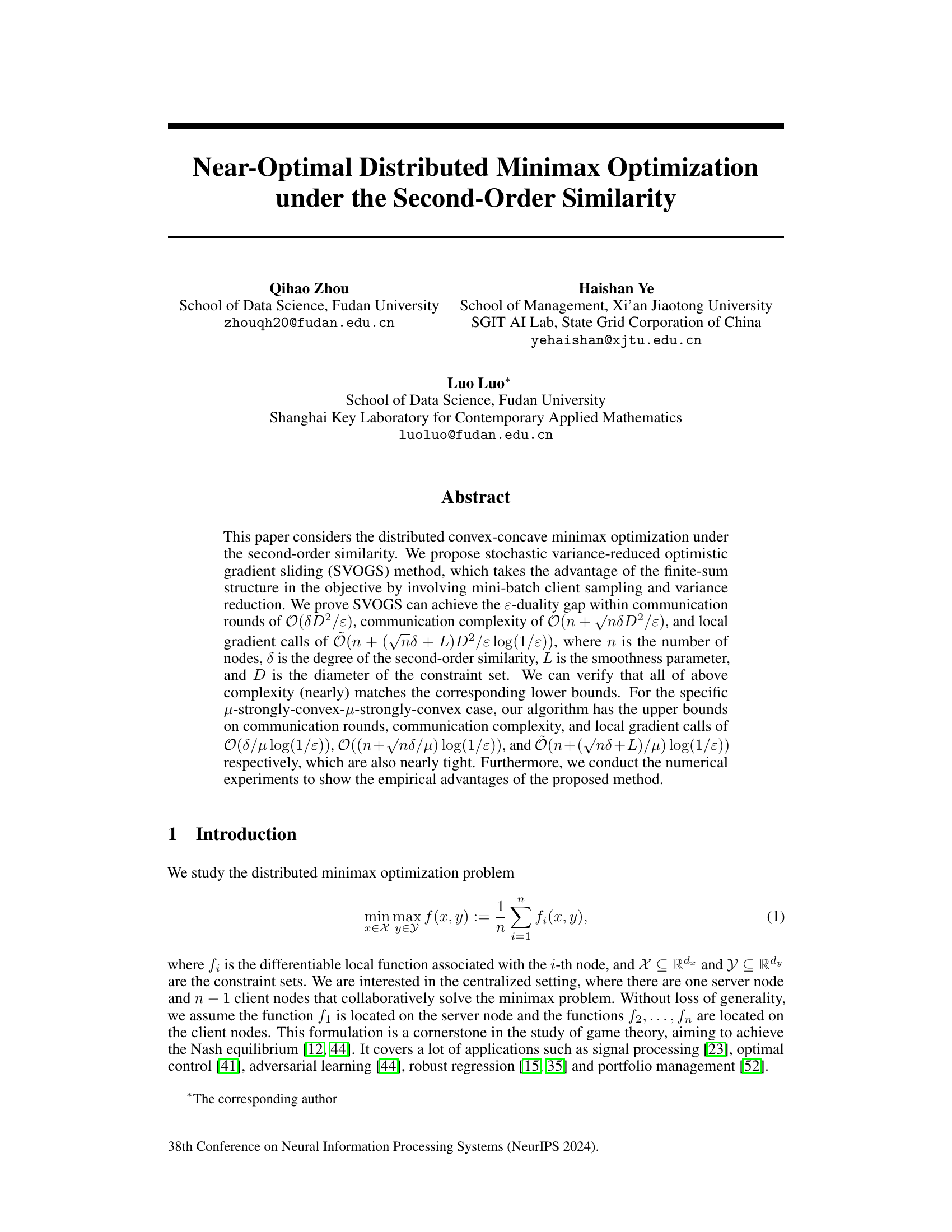

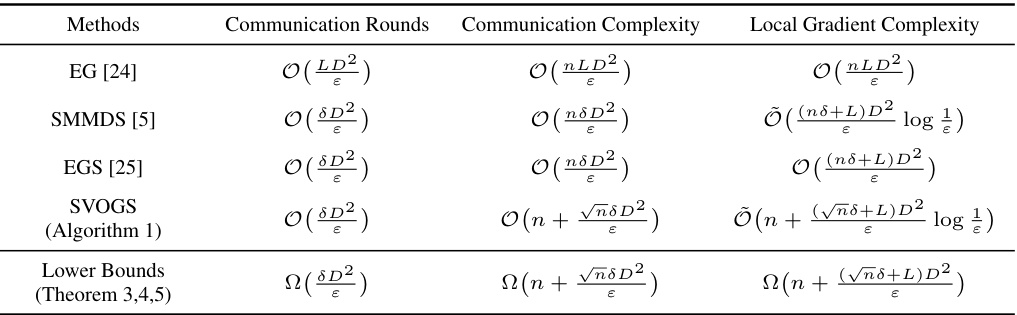

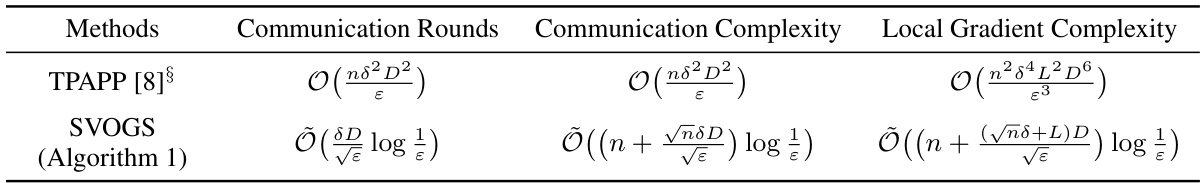

🔼 This table compares the complexities of achieving an Ɛ-duality gap for various convex-concave minimax optimization methods. The complexities are broken down into communication rounds (the number of times nodes communicate), communication complexity (total amount of data transmitted), and local gradient complexity (total number of local gradient computations). The methods compared include Extra-Gradient (EG), Star Min-Max Data Similarity (SMMDS), Extra-Gradient Sliding (EGS), and the proposed Stochastic Variance-Reduced Optimistic Gradient Sliding (SVOGS). Lower bounds are also provided to show the near-optimality of the proposed method.

read the caption

Table 1: The complexity of achieving E[Gap(x, y)] < ɛ in convex-concave case.

In-depth insights#

Minimax Optimization#

Minimax optimization is a crucial game-theoretic framework for finding optimal strategies in competitive scenarios. It aims to minimize the maximum possible loss, a robust approach particularly useful when dealing with uncertain or adversarial environments. The core concept involves two competing players, each seeking to optimize their objective function. This duality results in a saddle point, representing the equilibrium of the game, where neither player can unilaterally improve their situation. Applications are diverse, spanning machine learning (e.g., Generative Adversarial Networks), robust optimization, and control theory. However, its computational challenges necessitate sophisticated algorithms. Stochastic variance-reduced methods have emerged as efficient approaches, particularly for large-scale problems, where they reduce computational cost and time significantly. Furthermore, the concept of second-order similarity enhances the efficiency of distributed solutions for minimax optimization, especially in network settings with interconnected agents. Research into minimax optimization continues to address critical issues such as convergence speed, computational complexity, and scalability, especially when tackling high-dimensional spaces and non-convex objectives.

Second-Order Similarity#

The concept of “Second-Order Similarity” in distributed optimization centers on the resemblance of local functions’ Hessians (second-order derivatives). This similarity implies that the local functions’ curvature is not drastically different from the global objective function’s curvature. This property is exploited to improve communication efficiency in distributed algorithms. Instead of communicating full gradients, algorithms leverage the shared curvature information to reduce communication overhead while maintaining convergence guarantees. The strength of this similarity, often denoted by a parameter (e.g., δ), directly impacts the algorithm’s convergence rate and communication complexity. A smaller δ indicates a higher similarity and, therefore, faster convergence and less communication. Developing efficient algorithms that exploit this similarity is key to creating computationally and communication-efficient distributed optimization methods. The use of second-order information offers the potential for substantial improvements over first-order methods, especially in high-dimensional problems where communication bottlenecks are significant. However, challenges remain in accurately estimating and effectively using second-order information while balancing computational cost.

SVOGS Algorithm#

The Stochastic Variance-Reduced Optimistic Gradient Sliding (SVOGS) algorithm is a novel method designed for distributed convex-concave minimax optimization. Leveraging the finite-sum structure of the objective function, SVOGS incorporates mini-batch client sampling and variance reduction techniques. This approach cleverly balances communication rounds, communication complexity, and computational complexity. The algorithm’s efficiency stems from its ability to achieve near-optimal complexities in all three areas, primarily due to the use of mini-batch sampling to manage the tradeoff between full and partial client participation strategies. This makes SVOGS particularly effective in environments with communication bottlenecks. The theoretical analysis demonstrates that SVOGS’s complexities are nearly tight, matching known lower bounds, while empirical evaluation showcases its strong performance compared to state-of-the-art methods. A key strength of the algorithm is its ability to handle both general convex-concave and strongly-convex-strongly-concave scenarios, providing optimal or near-optimal solutions in both cases. The inclusion of momentum terms within the gradient updates further enhances convergence. This well-rounded approach makes SVOGS a significant contribution to the field of distributed minimax optimization.

Complexity Analysis#

A rigorous complexity analysis is crucial for evaluating the efficiency and scalability of any algorithm. In the context of distributed minimax optimization, computational cost is multifaceted, encompassing communication rounds, communication complexity, and local gradient calls. A strong analysis would establish upper bounds on these aspects, ideally demonstrating near-optimality by comparing the achieved bounds to established lower bounds. Second-order similarity assumptions often play a role; analyzing how the algorithm’s complexity scales with this parameter reveals its performance in scenarios of greater homogeneity among local functions. Different convergence criteria (e.g., duality gap, gradient mapping) might be considered, leading to different complexity results. The analysis for strongly convex-strongly concave minimax problems is often sharper, yielding tighter bounds and potentially logarithmic dependence on the error tolerance. The complexity analysis should thoroughly justify all claims, with rigorous proofs supporting each complexity result and its dependence on problem parameters.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending the proposed method to handle non-convex minimax problems, a significantly more challenging scenario. Investigating the impact of different communication strategies (e.g., partial participation schemes) on the algorithm’s efficiency warrants further investigation. A deeper analysis of the lower bounds under various conditions (beyond convexity assumptions) could refine our understanding of optimal algorithms. Exploring how the framework can be adapted for federated learning settings, incorporating privacy-preserving techniques, is also a promising area. Finally, empirical evaluations on a wider range of real-world datasets, especially those exhibiting high dimensionality and non-stationarity, would strengthen the practical implications of the findings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure shows the results of the convex-concave minimax optimization problem (12) applied to the a9a dataset. The results are presented across three plots showing the convergence of the algorithms in terms of communication rounds, communication complexity, and local gradient calls. Each plot compares the performance of six different algorithms: EG, SMMDS, EGS, TPAPP, and SVOGS. The y-axis represents the duality gap, a measure of sub-optimality, while the x-axis represents the computational cost in terms of the respective metrics. The figure demonstrates the superior performance of SVOGS in achieving a lower duality gap within fewer rounds, lower complexity and gradient calls.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for convex-concave minimax problem (12) on a9a.

🔼 This figure presents the results of the convex-concave minimax optimization problem (12) on the a9a dataset. It shows the performance of several algorithms, including EG, SMMDS, EGS, TPAPP, and SVOGS, across three different metrics: communication rounds, communication complexity, and local gradient calls. Each algorithm’s convergence is illustrated graphically, allowing for a comparison of their efficiency and scalability.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for convex-concave minimax problem (12) on a9a.

🔼 This figure presents the results of solving the convex-concave minimax optimization problem (12) on the a9a dataset. It compares the performance of five different algorithms: Extra Gradient (EG), Star Min-Max Data Similarity (SMMDS), Extra-Gradient Sliding (EGS), Three Pillars Algorithm with Partial Participation (TPAPP), and the proposed Stochastic Variance-Reduced Optimistic Gradient Sliding (SVOGS) method. The results are shown for three different metrics: communication rounds, communication complexity, and local gradient calls. Each plot shows the convergence of the respective metric, with the x-axis representing the computational cost and the y-axis representing the duality gap or suboptimality measure.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for convex-concave minimax problem (12) on a9a.

🔼 This figure presents the results of the convex-concave minimax optimization problem (12) on the a9a dataset. It compares the performance of several optimization methods, including EG, SMMDS, EGS, TPAPP, and SVOGS, across three metrics: communication rounds, communication complexity, and local gradient calls. Each plot shows the convergence of the gradient mapping with respect to each metric. The results illustrate the relative efficiency of these different algorithms in solving the given minimax problem.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for convex-concave minimax problem (12) on a9a.

🔼 This figure presents the results of the convex-concave minimax optimization problem (12) on the a9a dataset. The results are shown in terms of communication rounds, communication complexity, and local gradient calls. The figure compares the performance of several optimization algorithms: EG, SMMDS, EGS, TPAPP, and SVOGS. Each algorithm’s performance is plotted against the corresponding metric on a logarithmic scale. The figure aims to demonstrate the empirical advantages of the proposed SVOGS method in terms of efficiency and convergence.

read the caption

Figure 1: Results for convex-concave minimax problem (12) on a9a.

More on tables

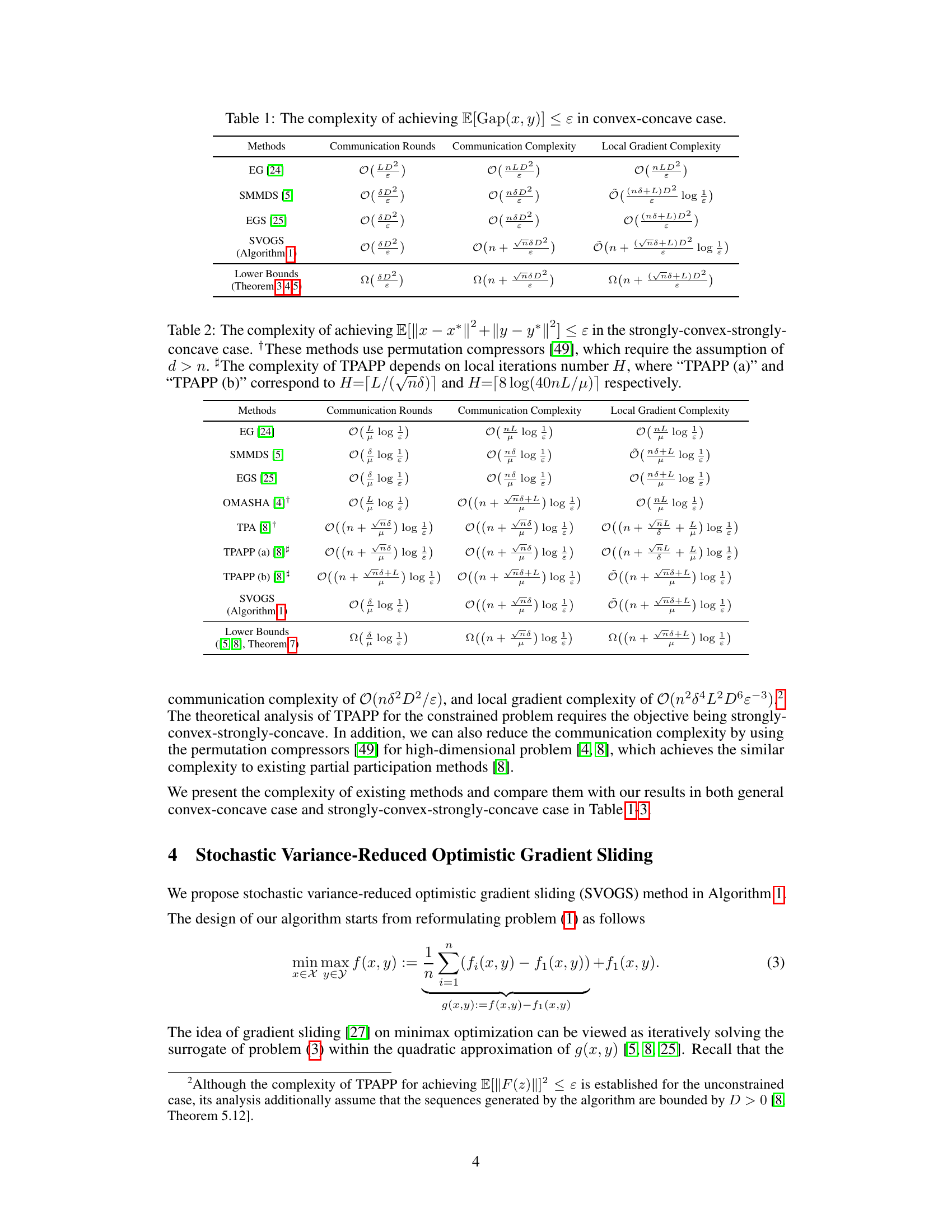

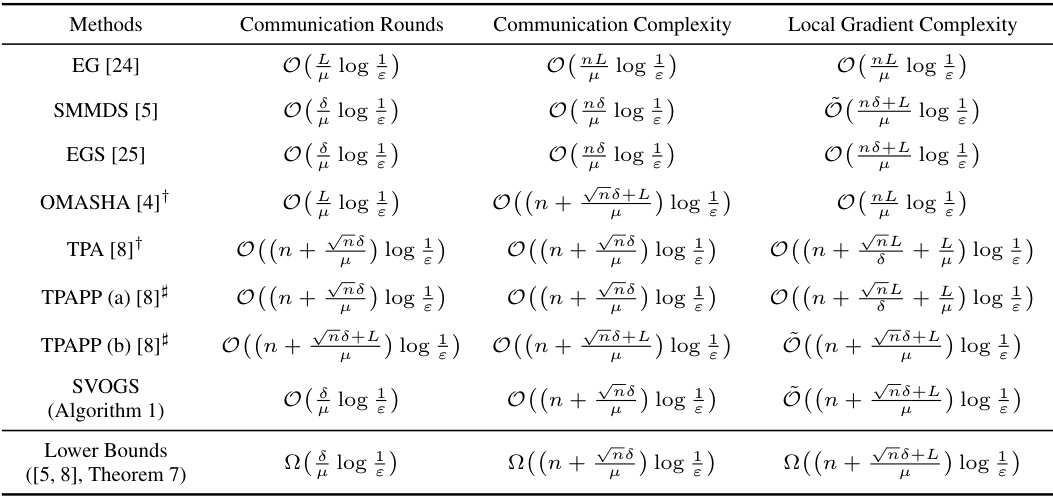

🔼 This table compares the complexities of different algorithms for achieving an ϵ-accurate solution in the strongly-convex-strongly-concave case of minimax optimization. The complexities are presented in terms of communication rounds, communication complexity, and local gradient complexity. Several algorithms are included, along with theoretical lower bounds. Note that some complexities depend on the number of local iterations.

read the caption

Table 2: The complexity of achieving E[||x − x* ||² + ||y – y*||2] < ɛ in the strongly-convex-strongly-concave case. These methods use permutation compressors [49], which require the assumption of d > n. #The complexity of TPAPP depends on local iterations number H, where “TPAPP (a)” and “TPAPP (b)” correspond to H=[L/(√nd)] and H=[8log(40nL/µ)] respectively.

🔼 This table presents the complexity results for achieving E[||F4(x, y)||²] < є in the convex-concave case. It compares the proposed SVOGS algorithm with TPAPP, highlighting the communication rounds, communication complexity, and local gradient complexity for each. Note that TPAPP makes additional assumptions about the constraint set Z and the boundedness of the generated sequence.

read the caption

Table 3: The complexity of achieving E[||F4(x, y)||²] < є in convex-concave case. §The TPAPP additionally assumes Z = Rd and the sequence generated by the algorithm is bounded by D > 0.

Full paper#