↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Deep learning models exhibit surprising scaling laws: performance improves polynomially as model and dataset sizes grow, counter to traditional statistical learning theory which predicts increasing variance with model size. This inconsistency hinders our understanding of deep learning’s generalization capabilities and optimal scaling strategies.

This paper addresses this inconsistency by studying scaling laws in an infinite-dimensional linear regression model. Using stochastic gradient descent (SGD) and assuming a Gaussian prior and power-law data covariance spectrum, the authors derive a theoretical bound for the test error. Crucially, the bound shows that the variance component is dominated by the other error terms, explaining why it’s often insignificant in practice. This provides a theoretical framework consistent with empirical neural scaling laws, offering valuable insights for improving model scaling and advancing our understanding of deep learning.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it resolves the conflict between empirical neural scaling laws and conventional statistical learning theory. It provides a theoretical framework for understanding why the variance error, typically expected to increase with model size, appears negligible in large-scale deep learning. This new understanding enables better model scaling strategies and guides future research in deep learning theory.

Visual Insights#

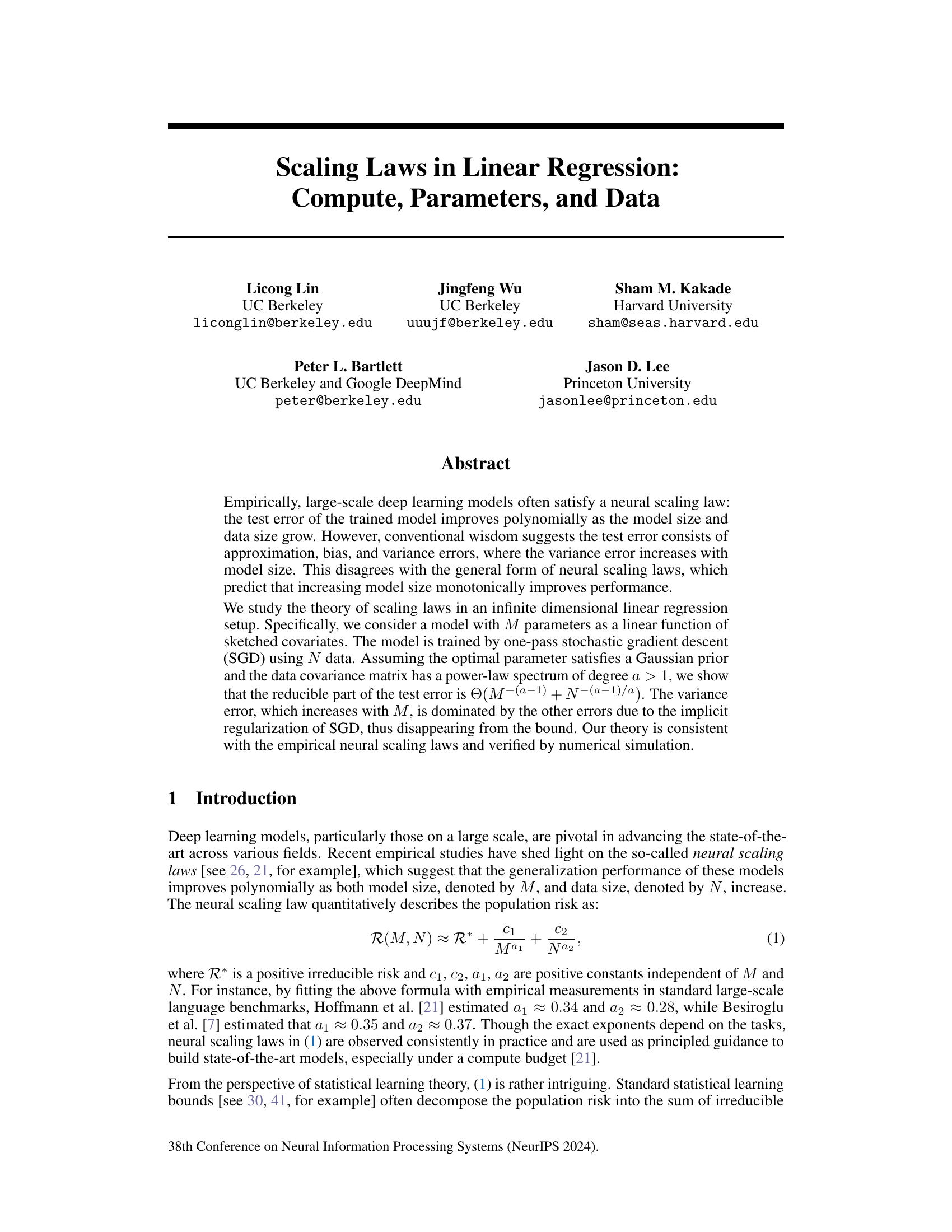

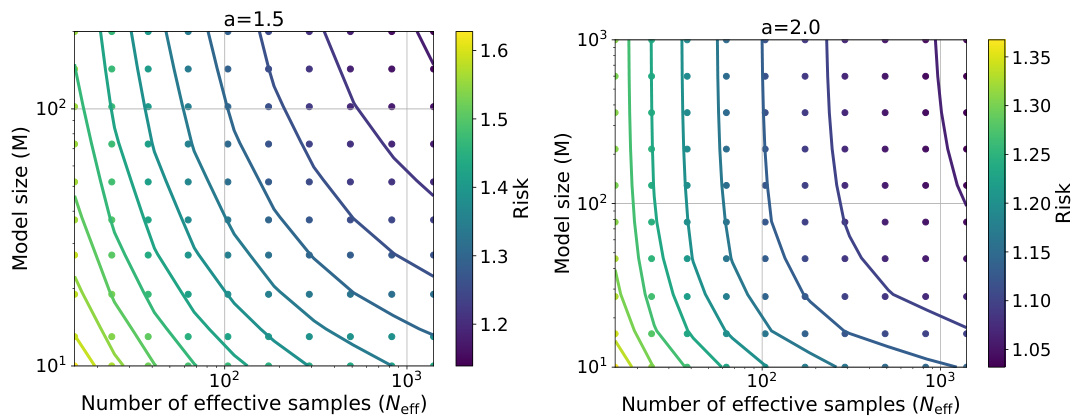

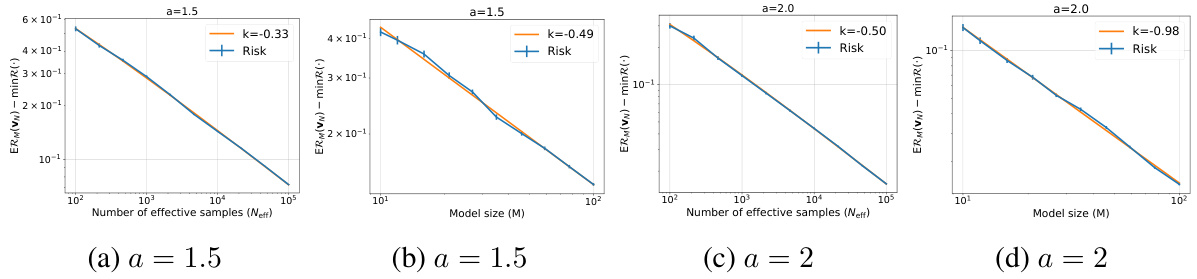

This figure shows the relationship between the expected risk, model size (M), and effective sample size (Neff) for different power-law degrees (α) in a linear regression model trained using stochastic gradient descent (SGD). The left panel shows results for α=1.5, and the right panel shows results for α=2.0. The risk is estimated by averaging over 1000 independent trials. The fitted exponents align closely with the theoretical predictions, supporting the claims made in the paper.

In-depth insights#

SGD Implicit Reg.#

The heading ‘SGD Implicit Reg.’ likely refers to the implicit regularization effects observed in Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) algorithms. SGD, while seemingly simple, exhibits a bias towards specific solutions during training, even without explicit regularization terms like weight decay. This implicit bias is a crucial aspect of deep learning’s success, often leading to better generalization than expected. The paper likely explores the theoretical underpinnings of this phenomenon in the context of linear regression, potentially showing how SGD’s inherent properties, such as its update rule and step size choices, implicitly regularize the model, preventing overfitting. A key question addressed might involve how this implicit regularization interacts with model size (M), dataset size (N), and the spectral properties of the data, resulting in the observed scaling laws. Understanding the interplay of these factors could provide crucial insights into the empirical success of large-scale deep learning models and explains the apparent contradiction between standard statistical learning theory and the observed scaling laws.

Power-Law Scaling#

Power-law scaling, in the context of large-scale machine learning models, describes the relationship between model performance and key resources such as the number of parameters or the size of the training dataset. Empirical evidence suggests a polynomial relationship, implying that improvements in performance diminish with increasing resource investment. This phenomenon is intriguing because it deviates from traditional assumptions about model complexity and generalization. Theoretical work attempts to explain power-law scaling by considering factors such as implicit regularization, optimization dynamics, and the underlying structure of data. A deeper understanding of power laws is vital for optimizing resource allocation in deep learning and for making predictions about the performance of future models, thereby enabling a more efficient and cost-effective approach to model development. The power law also highlights the need for moving beyond traditional statistical learning theories to explain the success of modern large-scale models and offers a framework for building more efficient and effective AI systems.

Risk Decomposition#

The heading ‘Risk Decomposition’ suggests a crucial methodological aspect of the research. It implies the researchers methodically broke down the overall risk into constituent components to gain a more granular understanding. This decomposition likely involved identifying and quantifying various sources of error or uncertainty, such as irreducible error, approximation error, and excess risk. Understanding these individual components is vital. It aids in identifying the dominant factors affecting performance, enabling a more targeted analysis. The irreducible error, often representing a fundamental limit of the model, helps assess achievable performance ceilings. Approximation error highlights the model’s limitations in representing the underlying data generating process. Finally, excess risk captures the error from the specific learning algorithm employed, which itself can comprise separate contributions from bias and variance. By carefully examining each risk component, the study could provide valuable insights into optimizing the model and algorithm for improved generalization performance.

Generalization Error#

Generalization error, the discrepancy between a model’s performance on training and unseen data, is a central challenge in machine learning. High generalization error indicates overfitting, where the model has learned the training data’s noise rather than underlying patterns. Conversely, underfitting results from models too simple to capture the data’s complexity, leading to poor performance on both training and test sets. Analyzing generalization error often involves examining model capacity (e.g., number of parameters), the complexity of the data distribution, and the chosen learning algorithm. Regularization techniques, such as weight decay or dropout, are commonly used to mitigate overfitting and improve generalization. Theoretical bounds on generalization error, derived from statistical learning theory, provide insights into the relationship between model complexity, sample size, and generalization performance. However, these bounds are often loose and don’t always align with empirical observations. Empirical studies of neural scaling laws have shown that, counterintuitively, increasing model size can sometimes improve generalization, challenging traditional theoretical understanding. Ultimately, reducing generalization error requires a careful balance between model complexity and data availability, informed by both theoretical analysis and practical experimentation.

Future Directions#

The paper’s “Future Directions” section would ideally explore extending the theoretical framework beyond linear regression models. Investigating scaling laws in more complex models, such as deep neural networks, would be crucial to validating the theoretical findings empirically. This would involve developing new theoretical tools to address the challenges posed by non-linearity and the high dimensionality of deep learning models. Furthermore, exploring the impact of different optimization algorithms (e.g., Adam, momentum-based methods) on scaling laws would be valuable. The assumption of Gaussian priors and power-law spectra should be relaxed to test the robustness of the findings under various data distributions. Finally, the study should analyze the implications of the findings in relation to practical considerations such as the implications for compute budget allocation and resource efficiency in training large-scale models. The practical applications and potential limitations, particularly with regards to the strong assumptions made, require detailed examination.

More visual insights#

More on figures

The figure shows the relationship between the expected risk, the effective sample size, and the model size for two different power-law degrees (a=1.5 and a=2). Each plot shows two lines: one representing the actual risk values and another from a linear fit on the log-log scale. The slopes of the fitted lines (k) are reported, and error bars representing the standard deviation of the risk estimations are also presented.

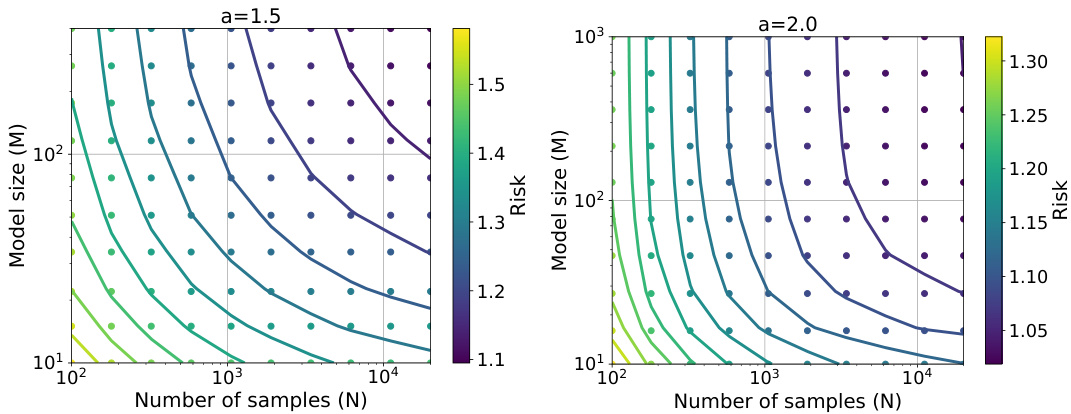

This figure shows the empirical risk (the mean squared error) of the last iteration of stochastic gradient descent (SGD) in an infinite-dimensional linear regression model. The risk is plotted against the effective sample size (Neff) and model size (M) for two different power-law degrees (a = 1.5 and a = 2.0). The effective sample size is the number of samples divided by the logarithm of the number of samples. The plots show the empirical risk decreases as both Neff and M increase, confirming the scaling laws observed. The fitted exponents of the empirical relationship are close to theoretical predictions, supporting the analysis of the model.

This figure shows the relationship between the expected risk (minus irreducible risk), effective sample size, and model size for two different power-law degrees (a=1.5 and a=2). The error bars represent the standard deviation obtained from 100 independent runs. Linear functions are fitted to the log-log scale data and their slopes (k) are reported.

Full paper#