↗ arXiv ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional reinforcement learning methods struggle to generate diverse and effective robotic policies, often requiring extensive training data and failing to generalize well to new scenarios. Moreover, creating effective policies for various robots and tasks is challenging due to differences in their dynamics and the high dimensionality of the policy parameters. This necessitates a more efficient and generalizable approach for policy learning.

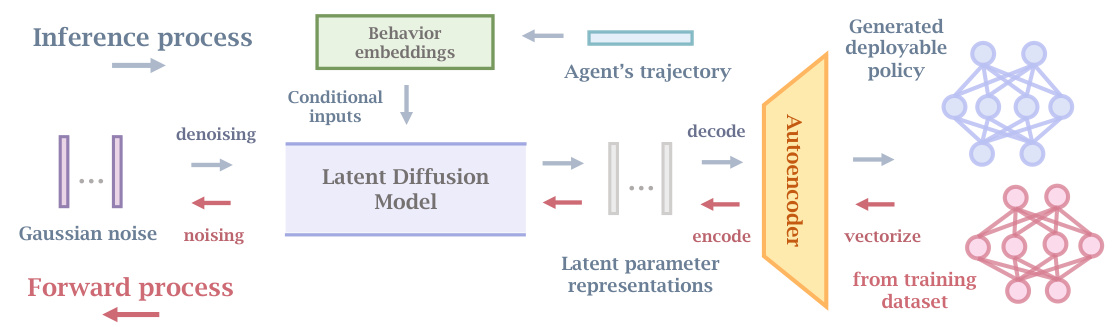

Make-An-Agent addresses these issues by employing a novel method that leverages the power of conditional diffusion models. The key idea is to generate policy parameters by refining noise within a latent space guided by behavior embeddings. These embeddings, which encode trajectory information, effectively condition the diffusion process, resulting in policies that are well-adapted to the corresponding tasks. The results demonstrate the method’s effectiveness across multiple domains and its superior generalization performance compared to state-of-the-art approaches. Furthermore, deployment onto real-world robots confirms the practical viability and robustness of this novel approach.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents Make-An-Agent, a novel approach to policy generation in reinforcement learning. It offers a significant advancement over traditional methods by using diffusion models and behavior embeddings. This approach is highly generalizable and efficient, paving the way for more efficient and robust AI agents. The real-world deployment of generated policies further enhances its practical impact, opening up new avenues of research in robotics and AI.

Visual Insights#

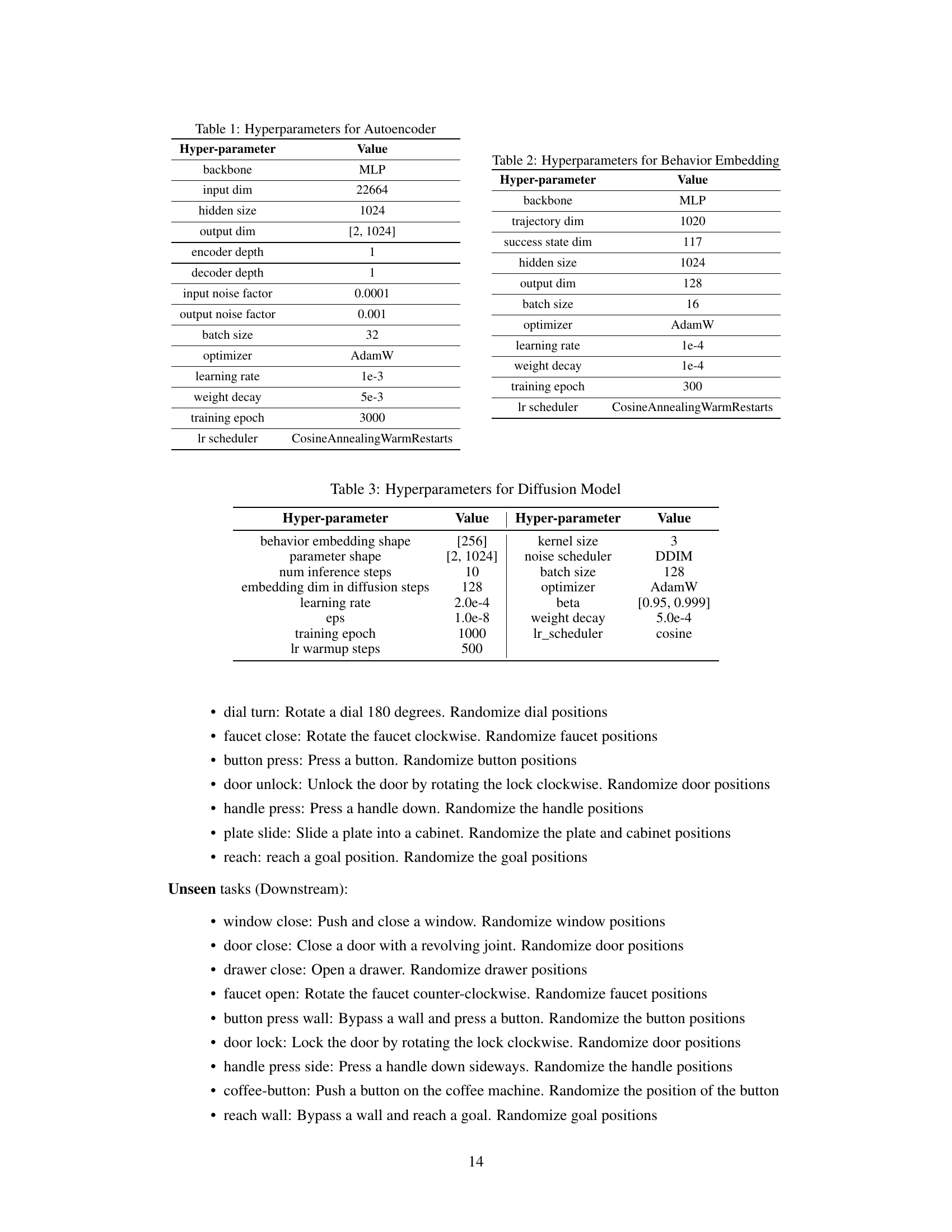

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall workflow of Make-An-Agent. It shows how the system takes an agent’s trajectory as input, extracts behavior embeddings, and feeds them into a latent diffusion model. This model, conditioned on the behavior embeddings, generates latent parameter representations. These representations are then decoded by an autoencoder to produce a deployable policy network. The diagram also depicts the forward process of adding noise to the policy parameters before the denoising step.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview: In the inference process of policy parameter generation, conditioning on behavior embeddings from the agent's trajectory, the latent diffusion model denoises random noise into a latent parameter representation, which can then be reconstructed as a deployable policy using the autoencoder. The forward process for progressively noising the data is also conducted on the latent space after encoding policy parameters as latent representations.

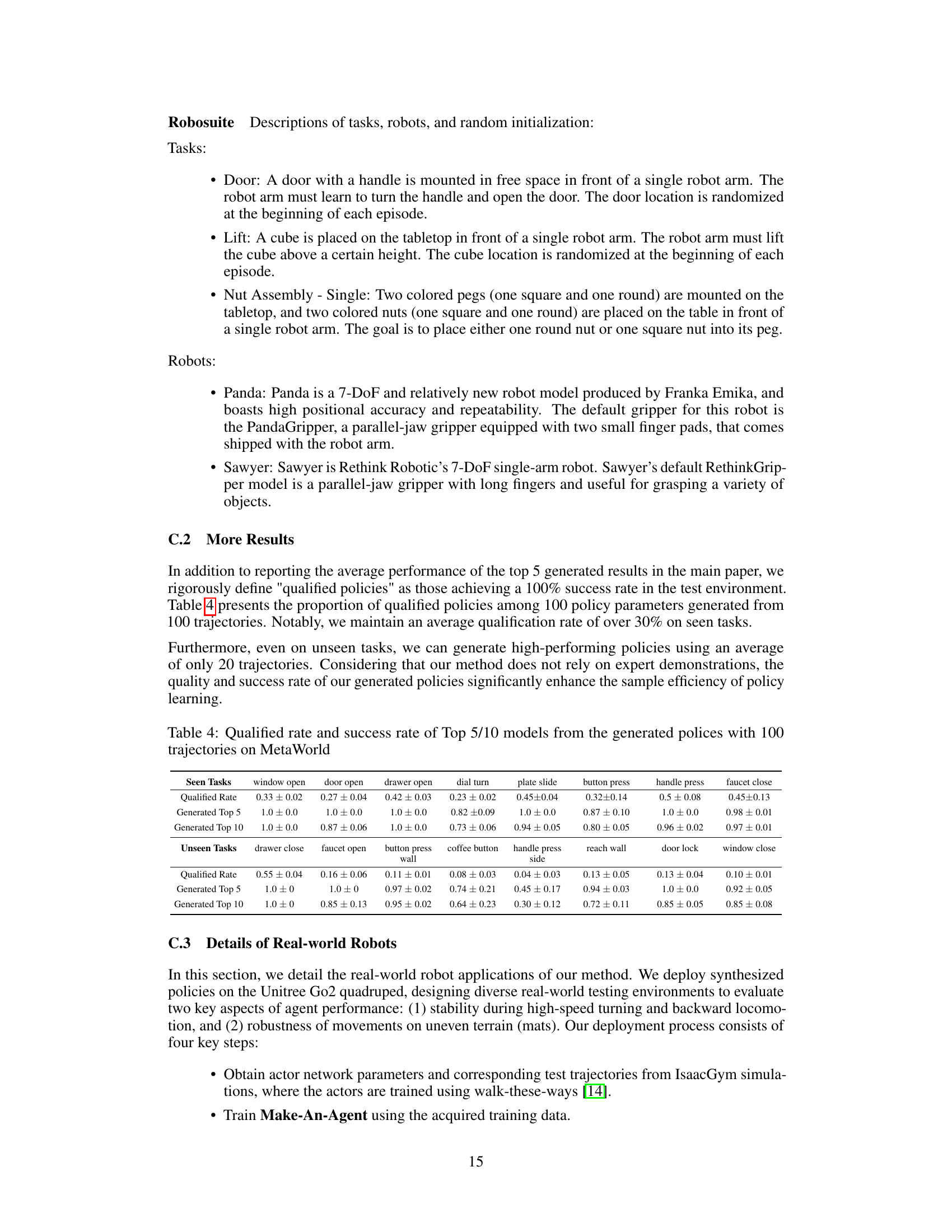

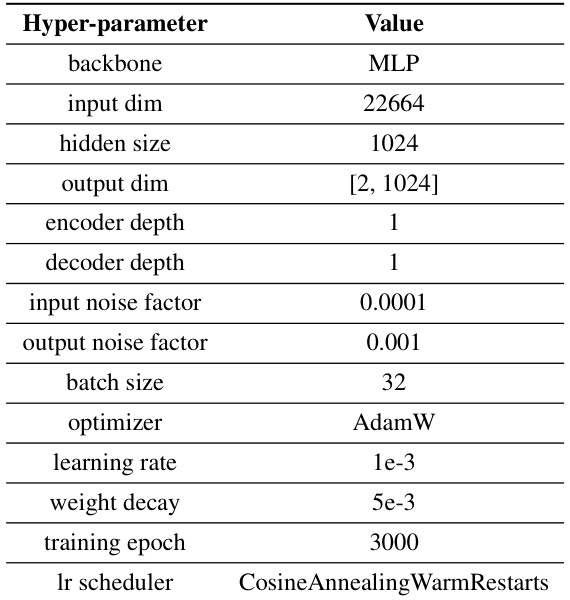

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the autoencoder model. It includes details on the network architecture (backbone, input/output dimensions, hidden size, encoder/decoder depth), regularization parameters (input/output noise factors, weight decay), optimization settings (optimizer, learning rate), training parameters (batch size, training epoch), and learning rate scheduling (lr scheduler). These settings are crucial for effectively training the autoencoder to efficiently encode and decode the policy network parameters into and from the latent representation.

read the caption

Table 1: Hyperparameters for Autoencoder

In-depth insights#

Behavior-Policy Gen#

The heading ‘Behavior-Policy Gen’ suggests a system capable of generating policies directly from behavioral data. This is a significant departure from traditional reinforcement learning, which often involves iterative training on reward signals. A successful ‘Behavior-Policy Gen’ system would directly map observed behaviors to optimal policy parameters, bypassing the need for extensive trial-and-error learning. This implies powerful representation learning capabilities, capable of extracting meaningful patterns from raw behavioral data and translating them into effective policy network architectures. Generalizability is crucial; the generated policies should ideally work well across various scenarios and tasks, even with limited or noisy behavioral data. The approach likely leverages machine learning models (e.g., neural networks) and potentially diffusion models, enabling the system to learn the underlying distributions of policy parameters and generate novel policies that go beyond the observed behaviors. The method’s effectiveness hinges on the quality of behavioral representations and the robustness of the generation model. It is also important to consider aspects like computational efficiency and the explainability of generated policies. The overall success of a ‘Behavior-Policy Gen’ would significantly impact various fields by automating policy learning and enabling faster deployment of AI agents in complex environments.

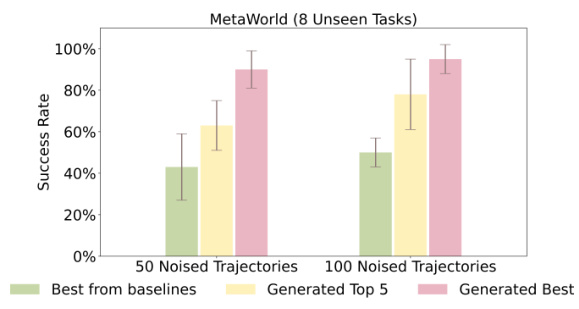

Diffusion Model Use#

The research leverages diffusion models for a novel approach to policy generation in reinforcement learning. Instead of directly training a policy network, the core idea is to generate the optimal network parameters from a given demonstration of desired agent behavior. This is achieved by encoding the behavior into an embedding, which then conditions a diffusion model. The diffusion model progressively refines noise into the latent representation of the policy network parameters, which are subsequently decoded into a functional policy. This method offers several advantages. Firstly, it’s more sample efficient, requiring only a single behavior demonstration instead of a large number of trajectories. Secondly, the approach is highly generalizable, demonstrating successful policy generation in unseen tasks and even across different robotic platforms. Thirdly, it’s proven to be robust to noisy input behavior data. The efficacy of this method suggests a potential paradigm shift for policy learning, providing a unique approach to overcome limitations faced by traditional RL methods.

Cross-task Generalization#

Cross-task generalization, the ability of a model to apply knowledge gained from one task to perform well on another, is a crucial aspect of artificial intelligence. In the context of reinforcement learning, this translates to an agent effectively transferring learned policies or skills to new, unseen tasks. This is particularly challenging because tasks often differ significantly in their state and action spaces, reward structures, and dynamics. Successful cross-task generalization reduces the need for extensive retraining for each new task, thus making AI systems more robust, adaptive, and efficient. The core challenge lies in identifying and leveraging task-invariant features, such as underlying skills, that can be generalized across diverse scenarios. Effective approaches often involve using techniques like meta-learning, transfer learning, and multi-task learning, which aim to learn generalizable representations or policies that can be easily adapted to new tasks with minimal retraining. However, the success of these methods is highly dependent on the relatedness of tasks and the design of the algorithm. For example, the structure of the parameter space itself can influence generalization; shared weights or modular architectures encourage similar behaviors across different tasks. Research in this area is crucial for developing more intelligent and adaptive agents capable of learning and performing in complex and dynamic environments without substantial retraining.

Real-World Testing#

The success of any robotics research hinges on its real-world applicability. A critical aspect often overlooked in academic papers is rigorous real-world testing. This involves deploying the developed algorithms and models in uncontrolled, dynamic environments, rather than relying solely on simulations. Real-world testing unveils unanticipated challenges and limitations not apparent in simulated environments, such as sensor noise, unpredictable environmental factors, and unexpected interactions. The paper should detail the specific real-world setup, including the robots used, the environment, and the metrics employed to evaluate performance. A comparison between simulated and real-world results provides valuable insights into the algorithm’s robustness and generalizability. Furthermore, careful consideration of safety protocols is crucial, especially when dealing with physical robots that could potentially cause damage or injury. Clear documentation of the experimental setup, including environmental conditions and any failures encountered, is vital for ensuring reproducibility and allowing others to build upon the work. Moreover, addressing the limitations uncovered during real-world testing is essential for refining the algorithm and advancing the field. The inclusion of high-quality videos showing the robot’s performance in the real-world setting would greatly enhance the paper’s impact and facilitate understanding.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the framework to handle more complex tasks and robots is crucial, potentially incorporating hierarchical structures for policy generation. The current approach relies on a single trajectory embedding; incorporating multiple trajectories or more sophisticated behavior representations could improve generalization. Investigating alternative diffusion models or hybrid approaches combining diffusion with other generative models could enhance performance or address limitations. Evaluating the model’s robustness across diverse environments and under various forms of noise is essential. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, a thorough investigation into the safety and ethical implications of generating policies automatically is needed, ensuring responsible development and deployment of this technology. This includes developing methods for verifying generated policies before deployment and addressing potential biases within the training data or model architecture.

More visual insights#

More on figures

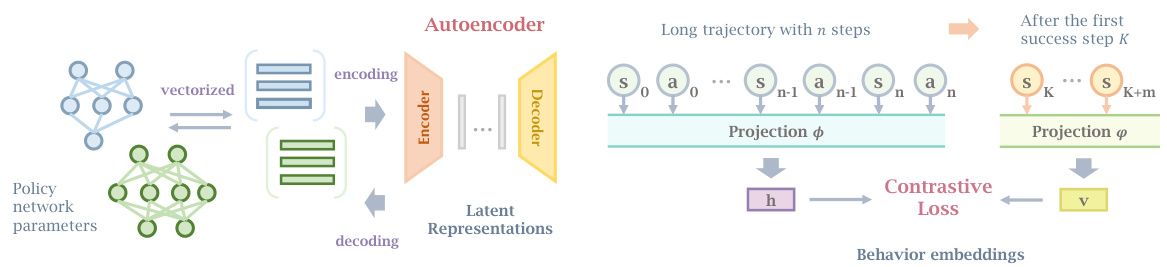

🔼 This figure shows two subfigures. The left subfigure (Figure 2) illustrates the autoencoder architecture used to encode and decode policy network parameters into a lower-dimensional latent representation. The input is the flattened policy network parameters, then encoded into a latent space and decoded back into parameters. The right subfigure (Figure 3) illustrates how contrastive learning is used to generate behavior embeddings. A long trajectory is divided into two parts: the initial n steps (τn), and the m steps after the first success step (τ̂). These two parts are separately projected into embedding vectors (h and v, respectively) using projection layers (φ). A contrastive loss function is then used to learn these behavior embeddings, which capture the mutual information between the preceding trajectory and subsequent states after the first success.

read the caption

Figure 2: Autoencoder: Encoding policy param- Figure 3: Contrastive behavior embeddings: Learning informative behavior embeddings from long trajectories with contrastive loss.

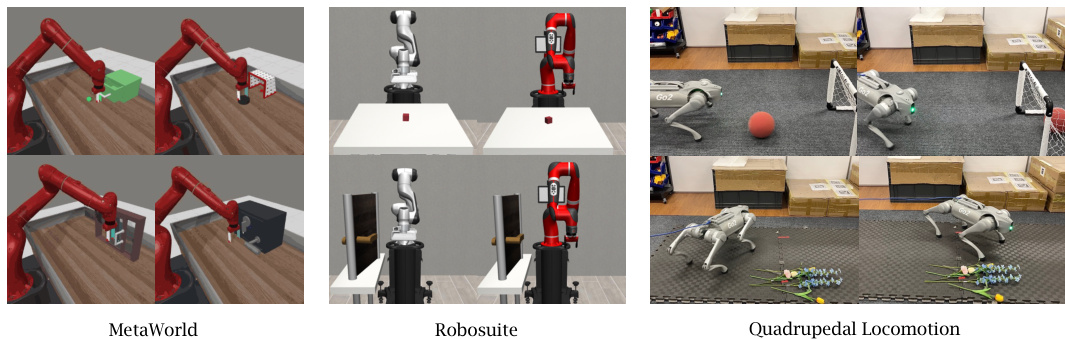

🔼 This figure shows three different experimental setups used in the paper. The leftmost panel shows the MetaWorld simulation environment, which features a robotic arm interacting with various objects on a table. The middle panel depicts the Robosuite simulation environment, which also includes a robotic arm performing manipulation tasks. The rightmost panel showcases a real-world quadrupedal robot navigating an environment with obstacles.

read the caption

Figure 4: Visualization of MetaWorld, Robosuite, and real quadrupedal locomotion.

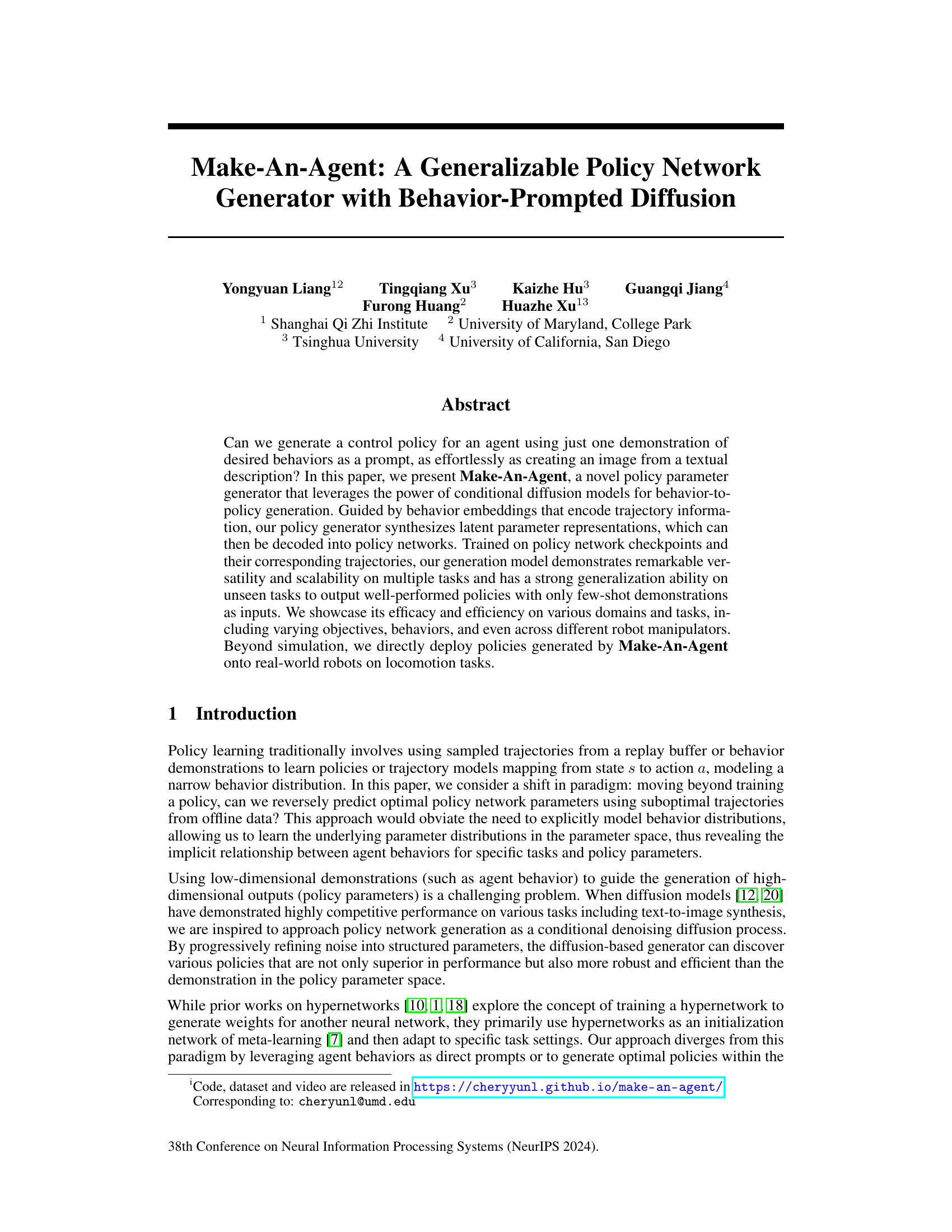

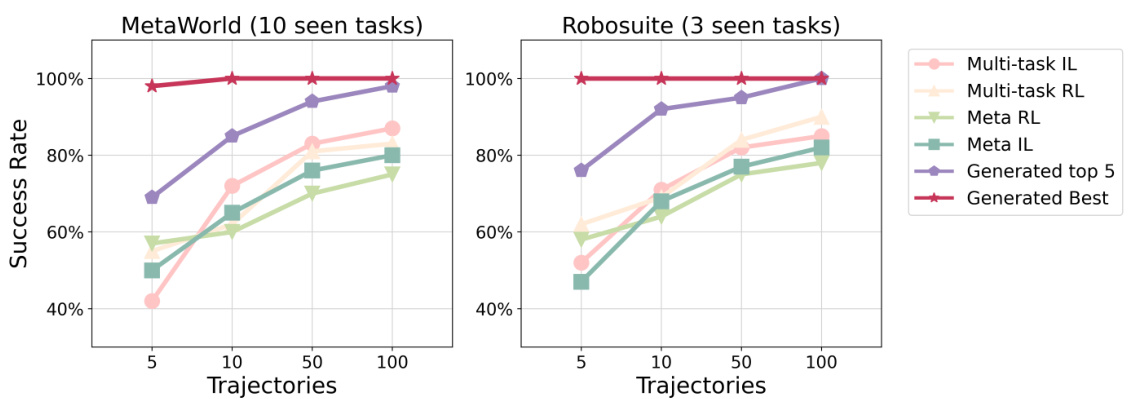

🔼 This figure displays the success rate of different methods on seen tasks in MetaWorld and Robosuite. The x-axis represents the number of test trajectories used, while the y-axis shows the success rate. The ‘Generated Best’ and ‘Generated Top 5’ lines represent the performance of the proposed Make-An-Agent method, showcasing its ability to generate high-performing policies from a small number of trajectories. The other lines represent baseline methods, such as multi-task imitation learning and meta-reinforcement learning, which require more data for comparable performance. The results show that Make-An-Agent significantly outperforms the baseline methods, especially when only a few trajectories are available.

read the caption

Figure 5: Evaluation of seen tasks with 5 random initializations on MetaWorld and Robosuite. Our method generate policies using 5/10/50/100 test trajectories. Baselines are finetuned/adapted by the same test trajectories. Results are averaged over training with 4 seeds.

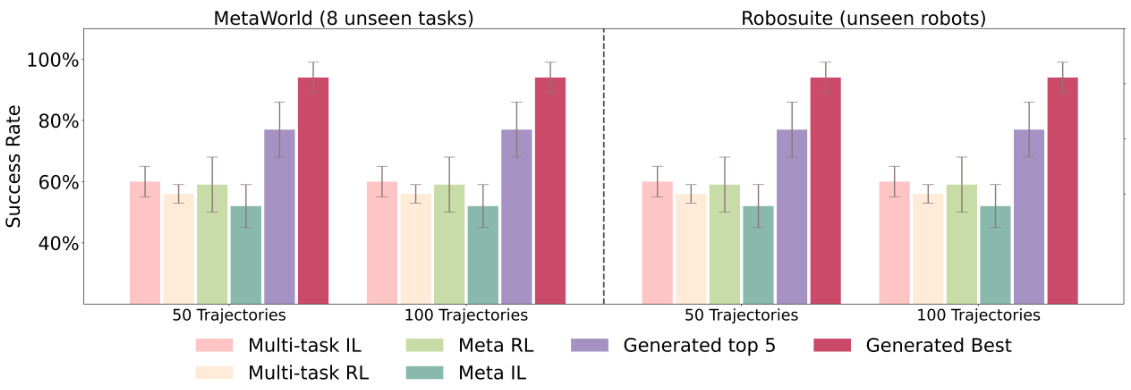

🔼 This figure compares the performance of Make-An-Agent and several baseline methods on unseen tasks in two robotic manipulation benchmarks: MetaWorld and Robosuite. The x-axis represents the number of test trajectories used. The bars show the success rate (with error bars) for each method. Notably, Make-An-Agent (Generated top 5 and Generated Best) outperforms the baselines, demonstrating strong generalization capabilities even without fine-tuning on the unseen tasks. The results highlight the effectiveness of the proposed method for generating policies.

read the caption

Figure 6: Evaluation of 8 unseen tasks with 5 random initializations on MetaWorld and Robosuite. Our method generates policies using 50/100 test trajectories without any finetuning. Baselines are adapted using the same test trajectories. Average results are from training with 4 seeds.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of Make-An-Agent and four baseline methods on 8 unseen tasks in MetaWorld and Robosuite. Make-An-Agent generates policies using only 50 or 100 test trajectories without any fine-tuning, showcasing its generalization ability. Baseline methods are adapted using the same test trajectories. The results are averaged across 4 different training seeds and 5 random initializations to assess the robustness of the generated policies.

read the caption

Figure 6: Evaluation of 8 unseen tasks with 5 random initializations on MetaWorld and Robosuite. Our method generates policies using 50/100 test trajectories without any finetuning. Baselines are adapted using the same test trajectories. Average results are from training with 4 seeds.

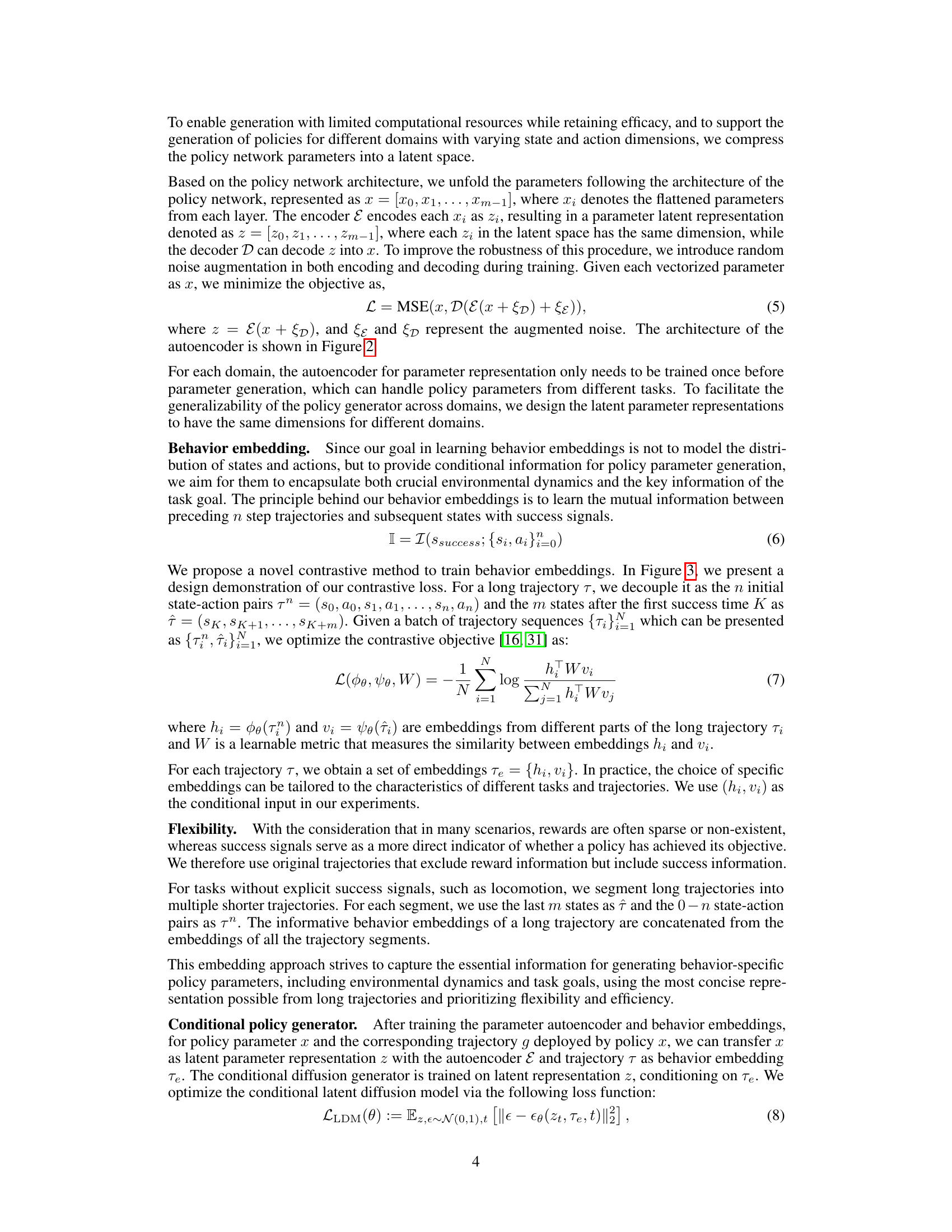

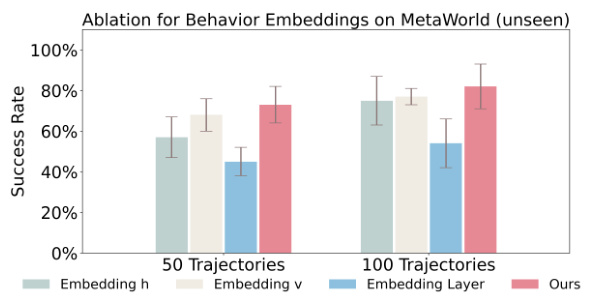

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of different choices of behavior embeddings on the performance of the proposed method. The figure compares the success rate on 5 unseen MetaWorld tasks when using different embeddings (embedding h, embedding v, an embedding layer) as condition inputs to the diffusion model for policy generation, against the full model’s performance (Ours). The results are shown for both 50 and 100 trajectories as input.

read the caption

Figure 8: Ablation studies about using different embeddings as conditions in policy generation on MetaWorld 5 unseen tasks. (Top 5 models)

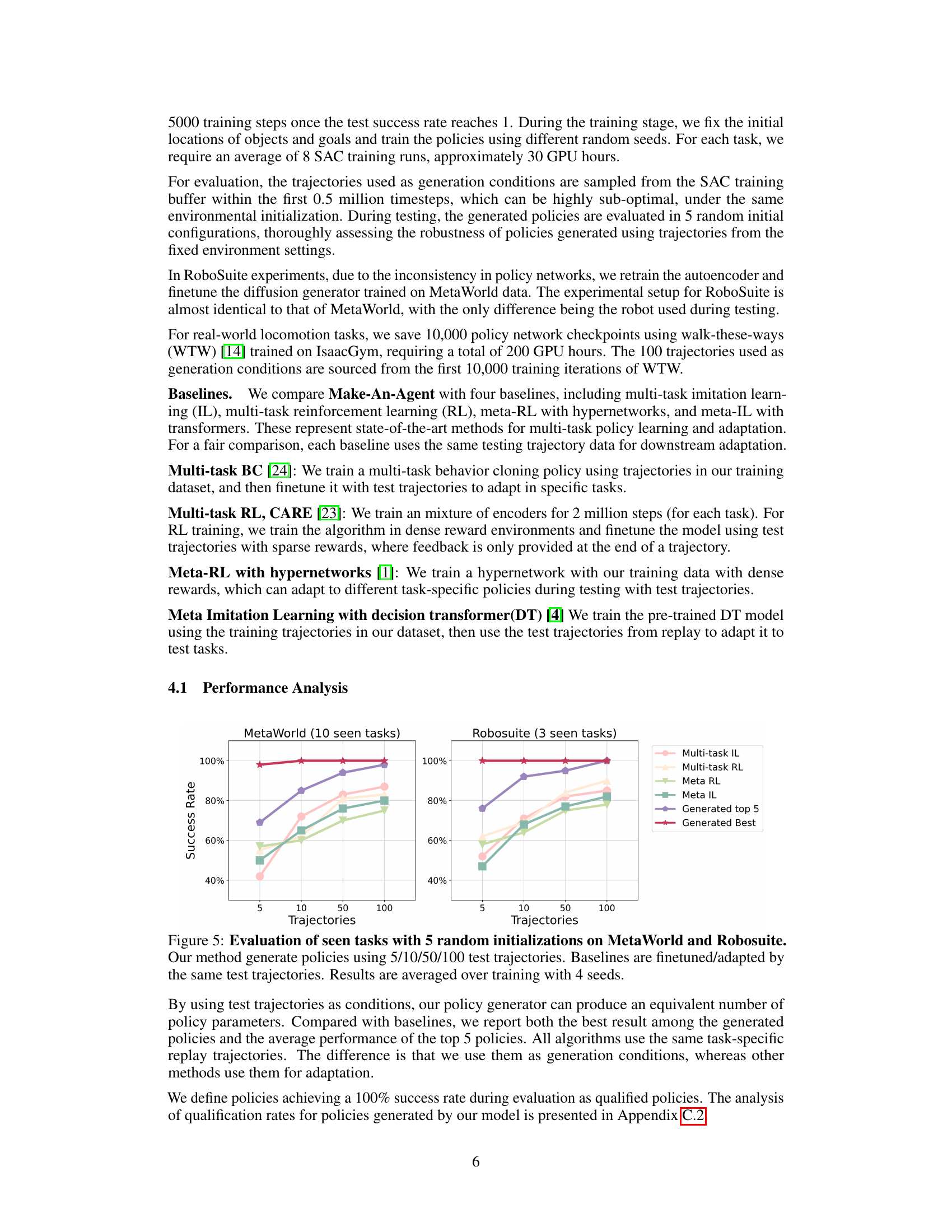

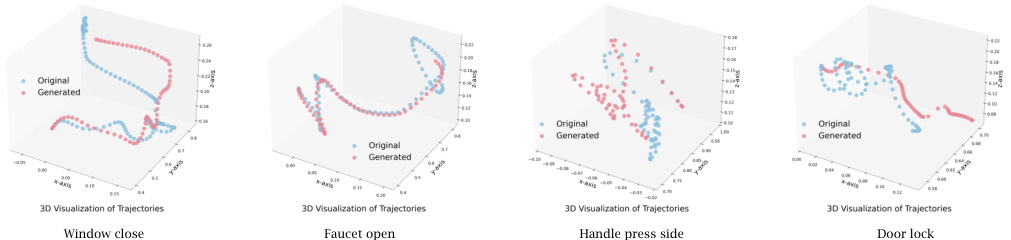

🔼 This figure visualizes the differences between trajectories used as conditional inputs for the policy generation model and the trajectories generated by the model when deployed on four unseen tasks from the MetaWorld environment. The visualization aims to highlight the diversity of policies generated by the model, showcasing that the generated policies do not simply mimic the input trajectories but rather produce novel and diverse behaviors.

read the caption

Figure 9: Trajectory difference: trajectories as conditional inputs v.s. trajectories from synthesized policies as outputs on MetaWorld 4 unseen tasks.

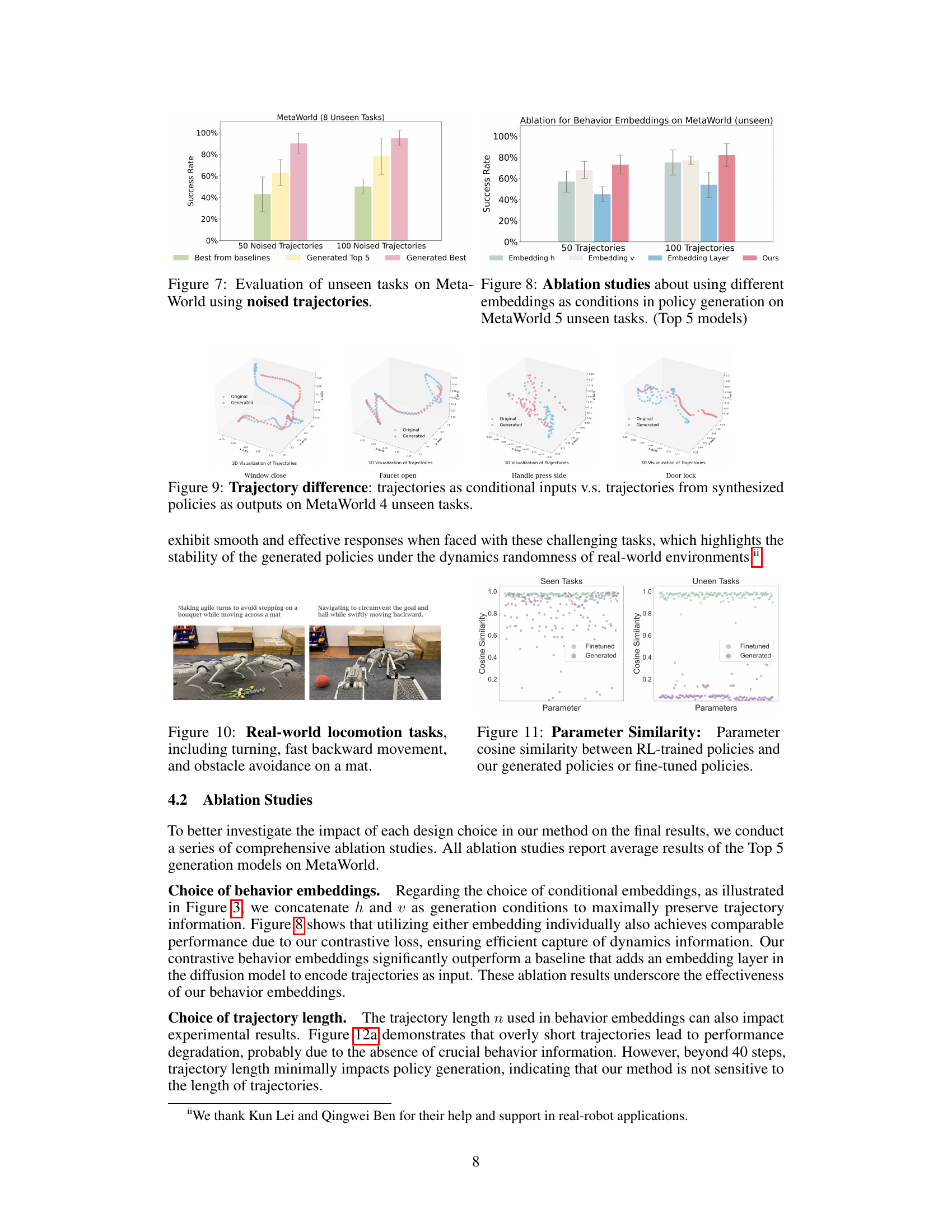

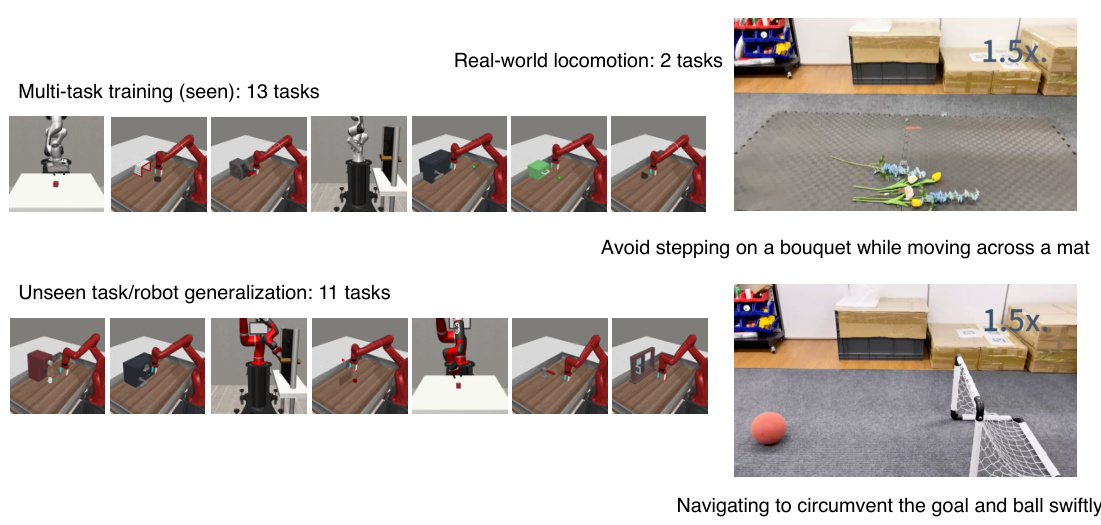

🔼 This figure shows two real-world locomotion tasks performed by a quadruped robot using policies generated by Make-An-Agent. The left image depicts the robot making agile turns to avoid a bouquet while moving across a mat. The right image displays the robot navigating around a ball and goal while moving swiftly backward. This demonstrates the ability of Make-An-Agent to generate policies that enable robust and complex locomotion behaviors in real-world scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 10: Real-world locomotion tasks, including turning, fast backward movement, and obstacle avoidance on a mat.

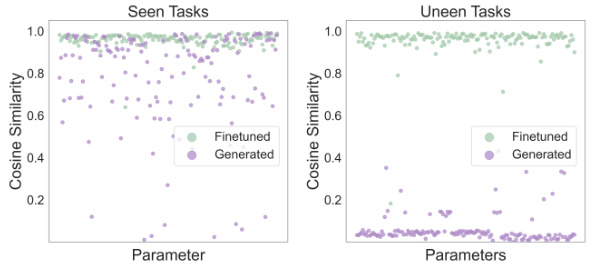

🔼 This figure compares the cosine similarity between parameters of RL-trained policies and those generated by the proposed method (Make-An-Agent) and those obtained after fine-tuning. The comparison is done for both seen and unseen tasks. The results show that the generated parameters for seen tasks have a relatively high similarity to the fine-tuned parameters, indicating that the model can generate similar policies. However, for unseen tasks, the similarity is much lower, suggesting the model is capable of generating novel policies, rather than simply memorizing the training data.

read the caption

Figure 11: Parameter Similarity: Parameter cosine similarity between RL-trained policies and our generated policies or fine-tuned policies.

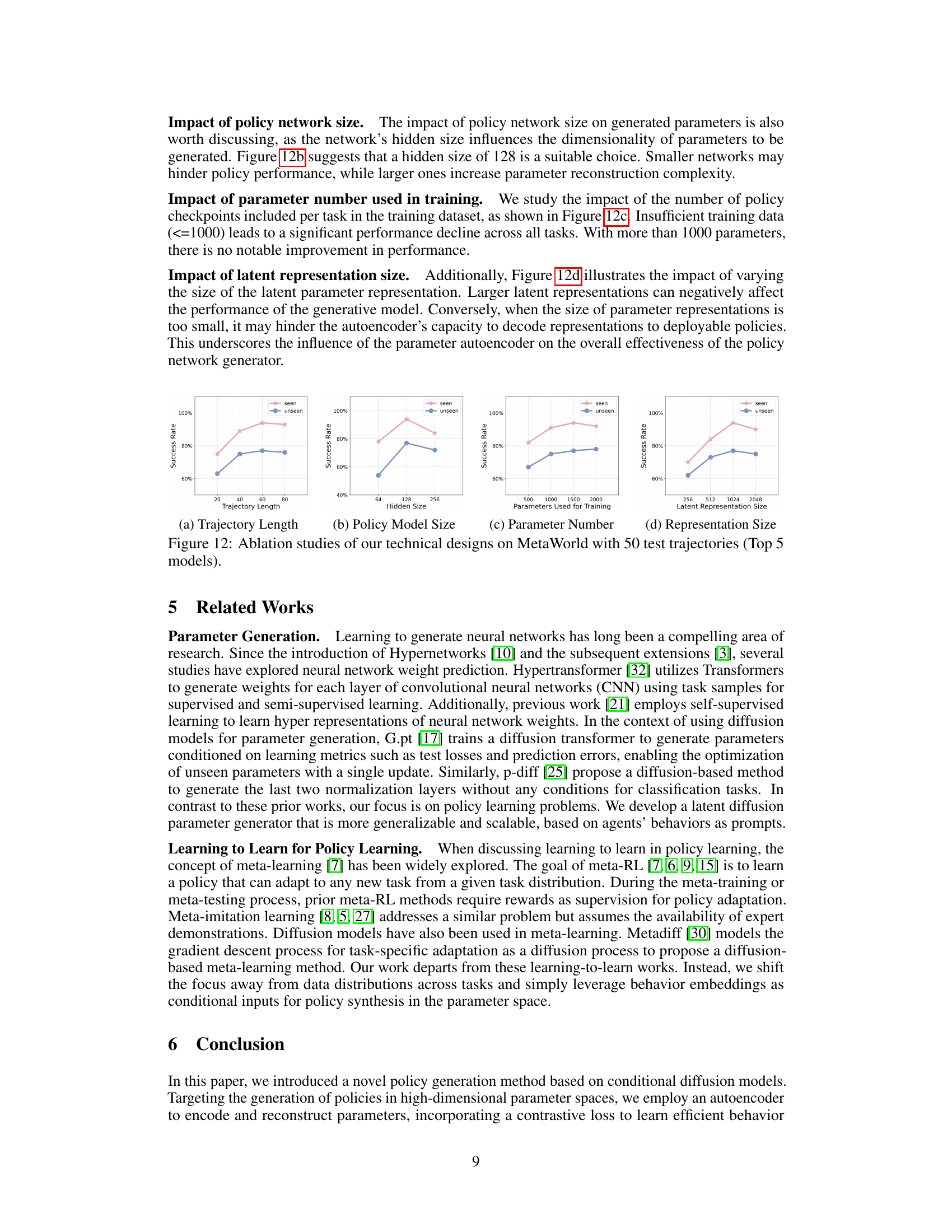

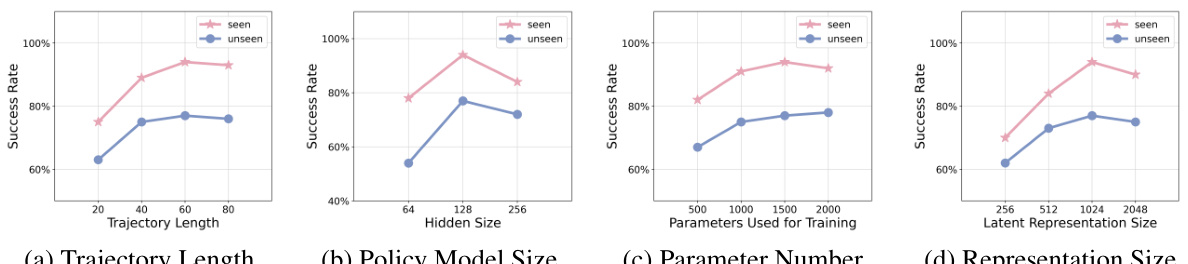

🔼 This figure presents the results of ablation studies conducted on the MetaWorld environment using 50 test trajectories. The top 5 models were selected for analysis. Four subfigures illustrate the impact of various design choices on the model’s performance: (a) Trajectory Length showing the effect of varying the length of input trajectories; (b) Policy Model Size demonstrating how the size of the policy network affects performance; (c) Parameter Number highlighting the influence of the number of parameters used for training; and (d) Representation Size illustrating how the dimensionality of the latent parameter representations impacts results. Each subfigure shows the success rate on both seen and unseen tasks.

read the caption

Figure 12: Ablation studies of our technical designs on MetaWorld with 50 test trajectories (Top 5 models).

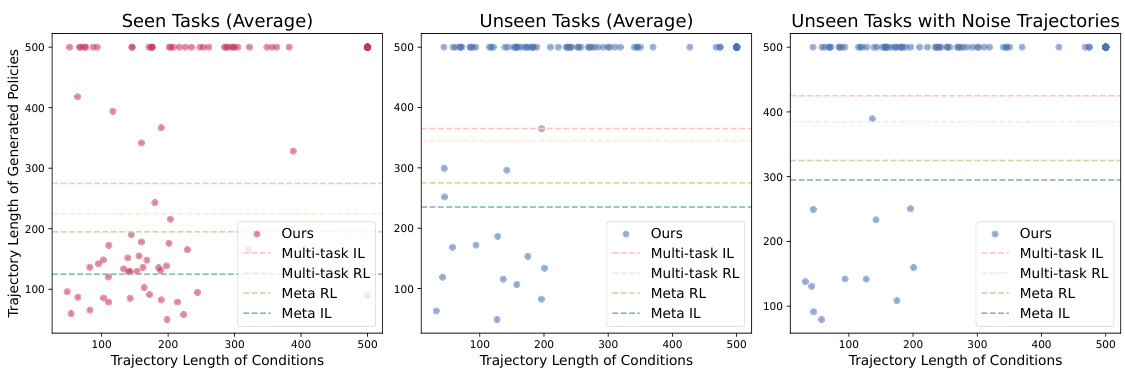

🔼 This figure displays the correlation between the length of the input trajectories (condition trajectories) used to generate policies and the length of the trajectories produced by those generated policies. The three subplots show this relationship for seen tasks, unseen tasks, and unseen tasks with added noise. Longer condition trajectories generally lead to longer generated trajectories, indicating that the model is learning to synthesize effective policies based on the duration of the provided example behavior. A longer trajectory often implies a more complex task, and the figure suggests that the model’s performance is strongly tied to the comprehensiveness of the input demonstration.

read the caption

Figure 13: Correlation between condition trajectories and generated policies. Trajectory length accurately reflects the effectiveness of the policies compared to the success rate. The maximum episode length in all the tasks is 500 (represents failure).

🔼 This bar chart compares the computational costs (in GPU hours) of the proposed Make-An-Agent method with four baseline methods: single RL, multi-task RL, meta RL, and meta IL. It shows that Make-An-Agent, when considering both training and evaluation time, has a significantly lower computational cost than the other methods. This highlights the efficiency of the proposed approach.

read the caption

Figure 14: Computational budgets of ours and baselines

🔼 This figure shows three different robotic environments used in the experiments of the paper: MetaWorld (a simulated robotic tabletop manipulation environment), Robosuite (another simulated robotic manipulation environment), and a real-world quadrupedal locomotion scenario. It visually demonstrates the diversity of tasks and environments on which the Make-An-Agent approach was tested, highlighting its applicability across various platforms and domains.

read the caption

Figure 4: Visualization of MetaWorld, Robosuite, and real quadrupedal locomotion.

More on tables

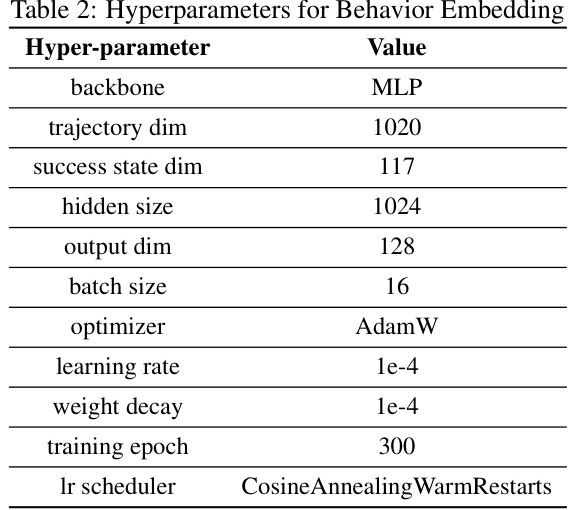

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the behavior embedding model. The behavior embedding model uses a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) architecture to encode trajectories and success states into a lower-dimensional embedding space. Hyperparameters specified include the network architecture (backbone), input dimensions (trajectory dim, success state dim), hidden layer size, output dimension, batch size, optimizer, learning rate, weight decay, number of training epochs, and the learning rate scheduler.

read the caption

Table 2: Hyperparameters for Behavior Embedding

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameters used to configure the conditional diffusion model. The hyperparameters control various aspects of the diffusion process, such as the embedding dimension, number of inference steps, learning rate, and optimizer. Understanding these values is crucial for reproducing the results of the paper and for modifying the training process.

read the caption

Table 3: Hyperparameters for Diffusion Model

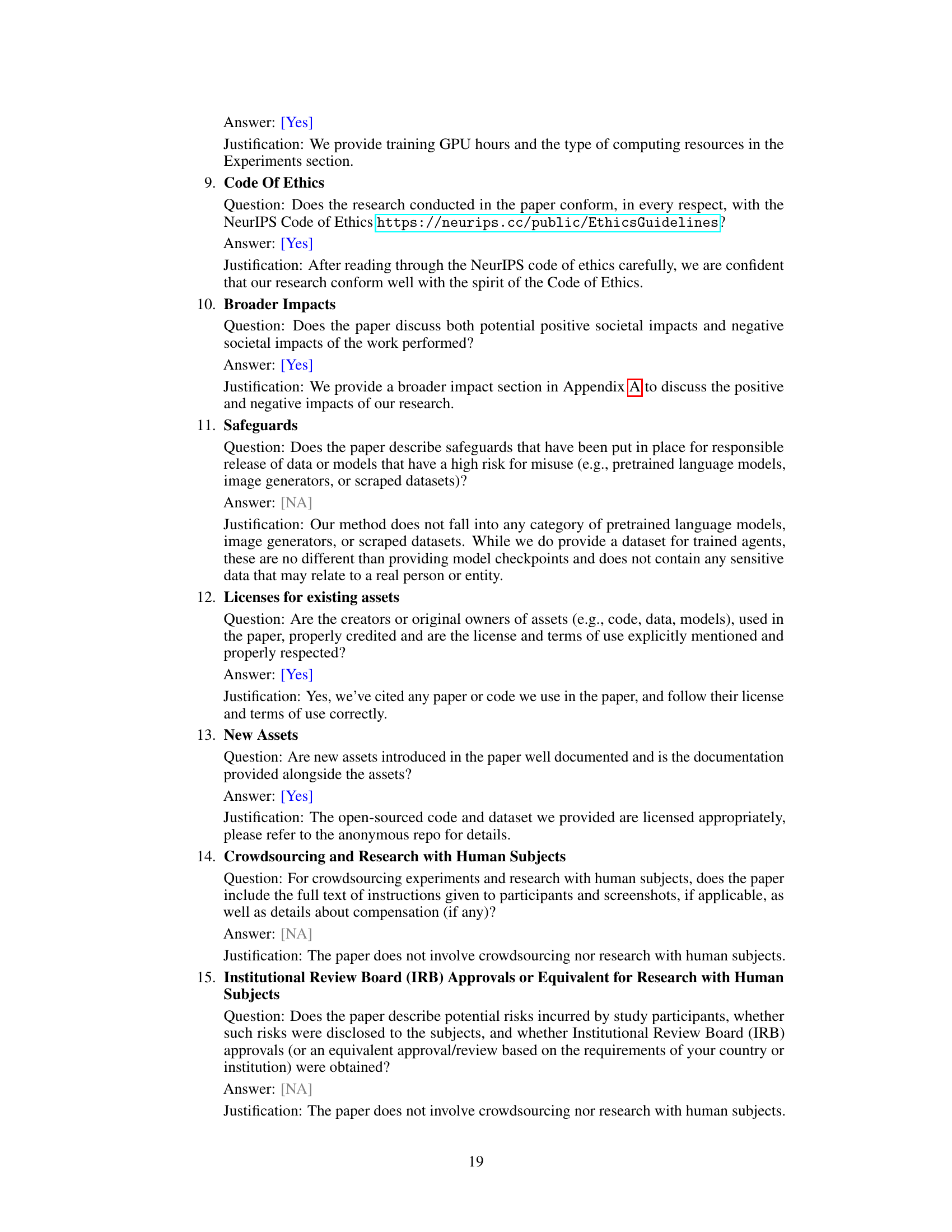

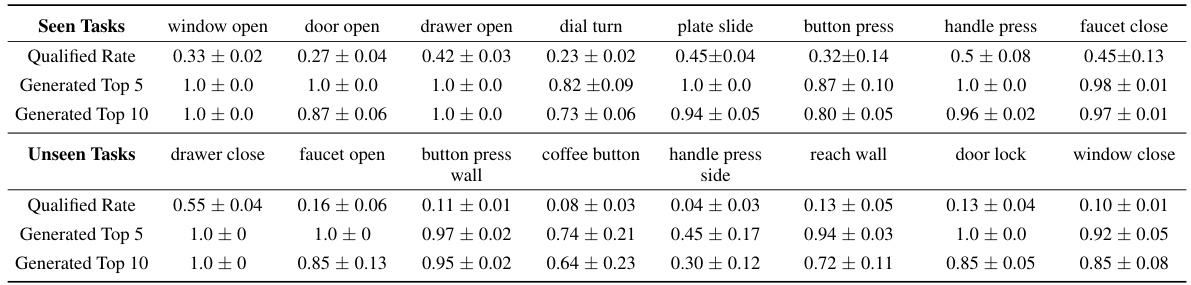

🔼 This table presents the success rate of generated policies on MetaWorld tasks. It shows the proportion of policies achieving 100% success rate (Qualified Rate) and the average success rate of top 5 and top 10 performing policies. The results are broken down for both seen (training) and unseen (testing) tasks, demonstrating the model’s performance on both familiar and novel scenarios.

read the caption

Table 4: Qualified rate and success rate of Top 5/10 models from the generated polices with 100 trajectories on MetaWorld

Full paper#