TL;DR#

Addressing bias and unfairness in machine learning is a significant challenge. Current approaches often fail to fully account for complex causal relationships between sensitive attributes, features, and outcomes. This limitation can lead to algorithms that perpetuate or even amplify existing inequalities, particularly under data uncertainty. This research aims to overcome these challenges.

The proposed solution is Causally Fair DRO, a new framework for building more robust and fair machine learning models. It integrates causal modeling with Wasserstein Distributionally Robust Optimization (DRO), offering a principled way to design algorithms that are resistant to data variation and ensure similar individuals receive similar treatment, regardless of sensitive attributes. The study offers theoretical guarantees for the proposed method and showcases its effectiveness through empirical evaluations using real-world datasets. The work provides practical tools and insights for building fairer and more responsible AI systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on fairness in machine learning, robust optimization, and causal inference. It bridges these fields by proposing a novel framework that considers causal structures and sensitive attributes when designing robust algorithms. This offers new avenues for creating fairer and more robust AI systems, particularly in domains susceptible to bias and distributional shifts. The finite-sample guarantees offer practical implications for real-world applications, paving the way for more reliable and equitable AI.

Visual Insights#

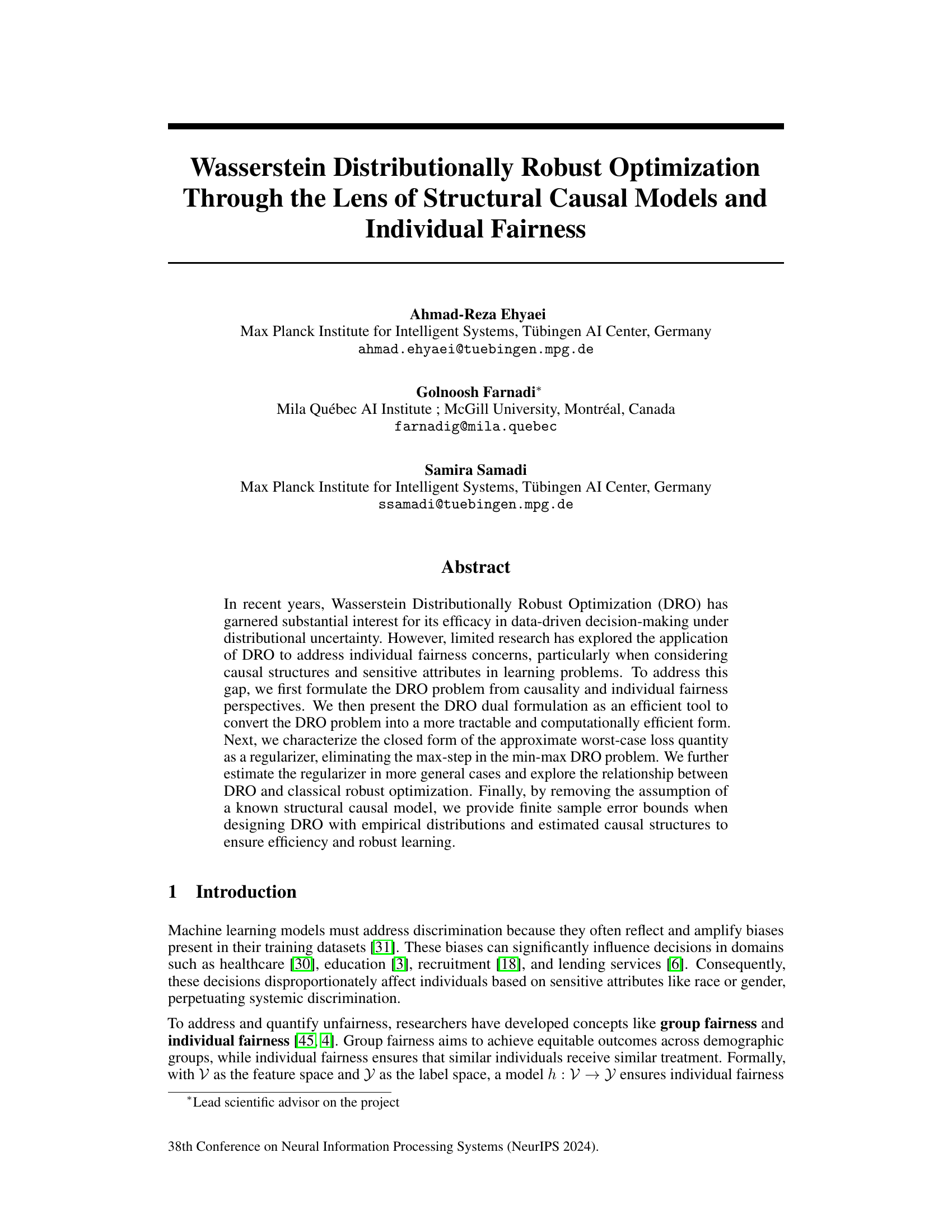

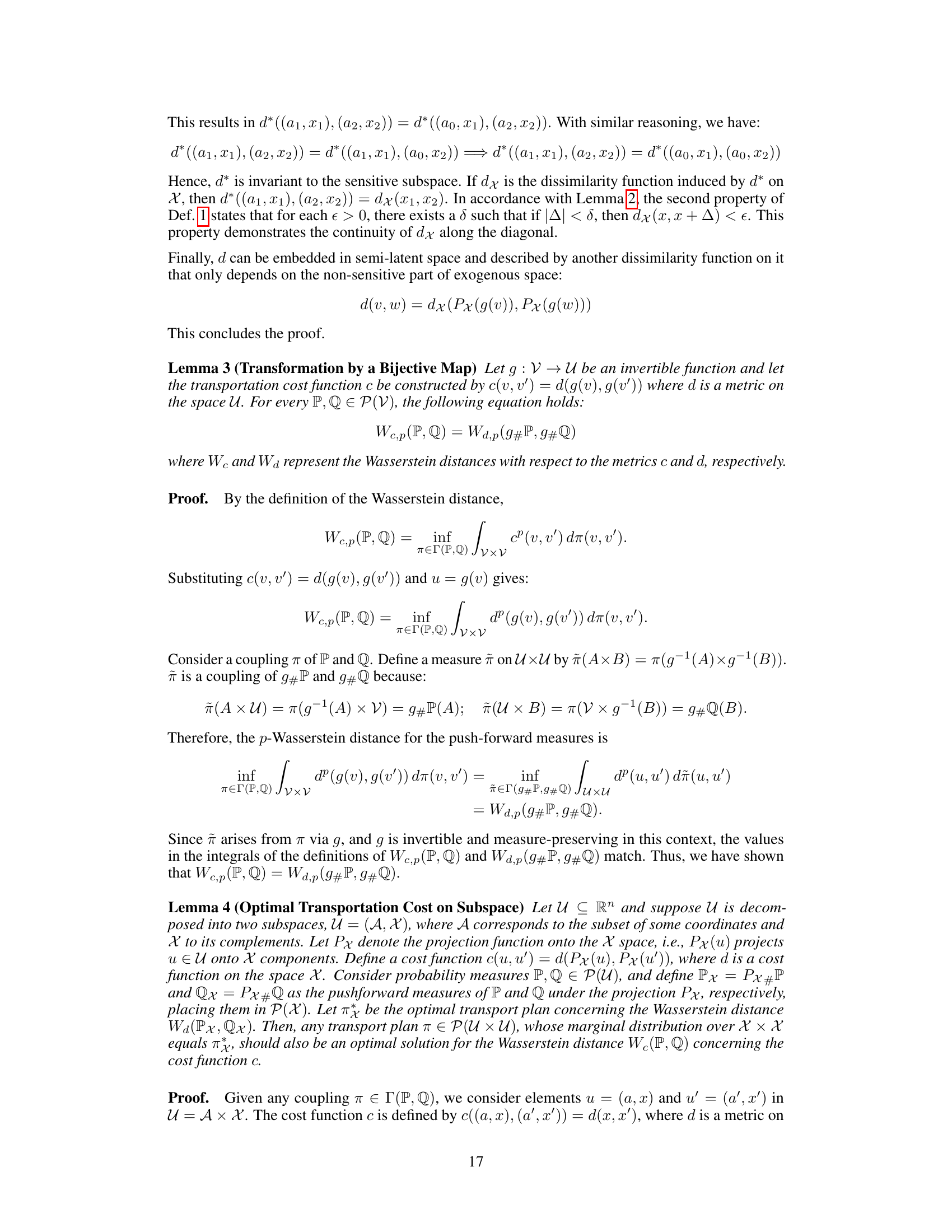

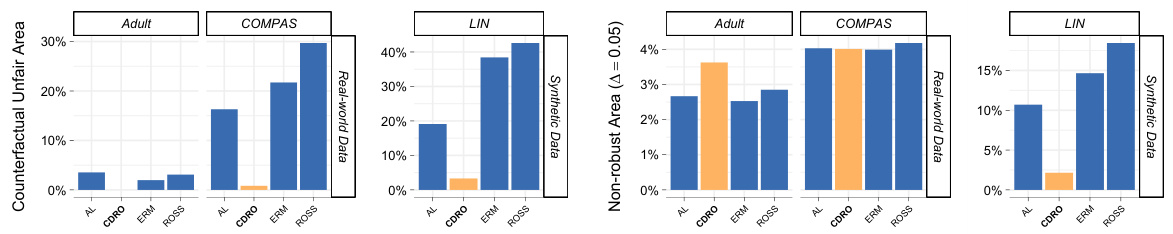

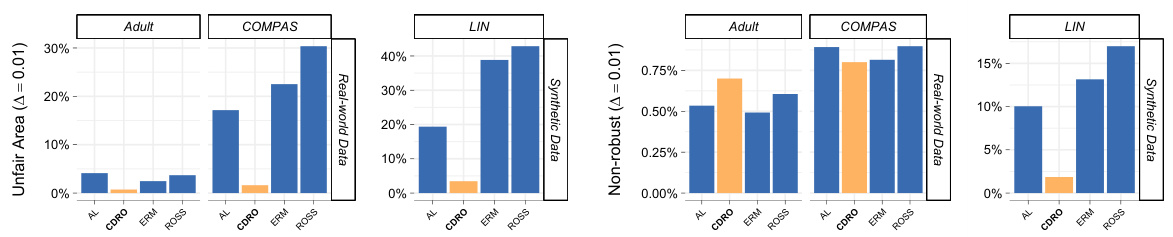

🔼 This figure displays a comparison of four different methods (AL, CDRO, ERM, ROSS) for mitigating individual unfairness across three datasets (Adult, COMPAS, LIN). The left panel shows the unfair area percentage for a sensitivity threshold of A = 0.05. The right panel shows the prediction accuracy of each method. Lower unfair area percentages and higher accuracies are preferred.

read the caption

Figure 1: Displays the findings from our numerical experiment, assessing the performance of DRO across different models and datasets. (left) Bar plot showing the comparison of models based on the unfair area percentage (lower values are better) for A = .05. (right) Bar plot comparing methods by prediction accuracy performance (higher values are better).

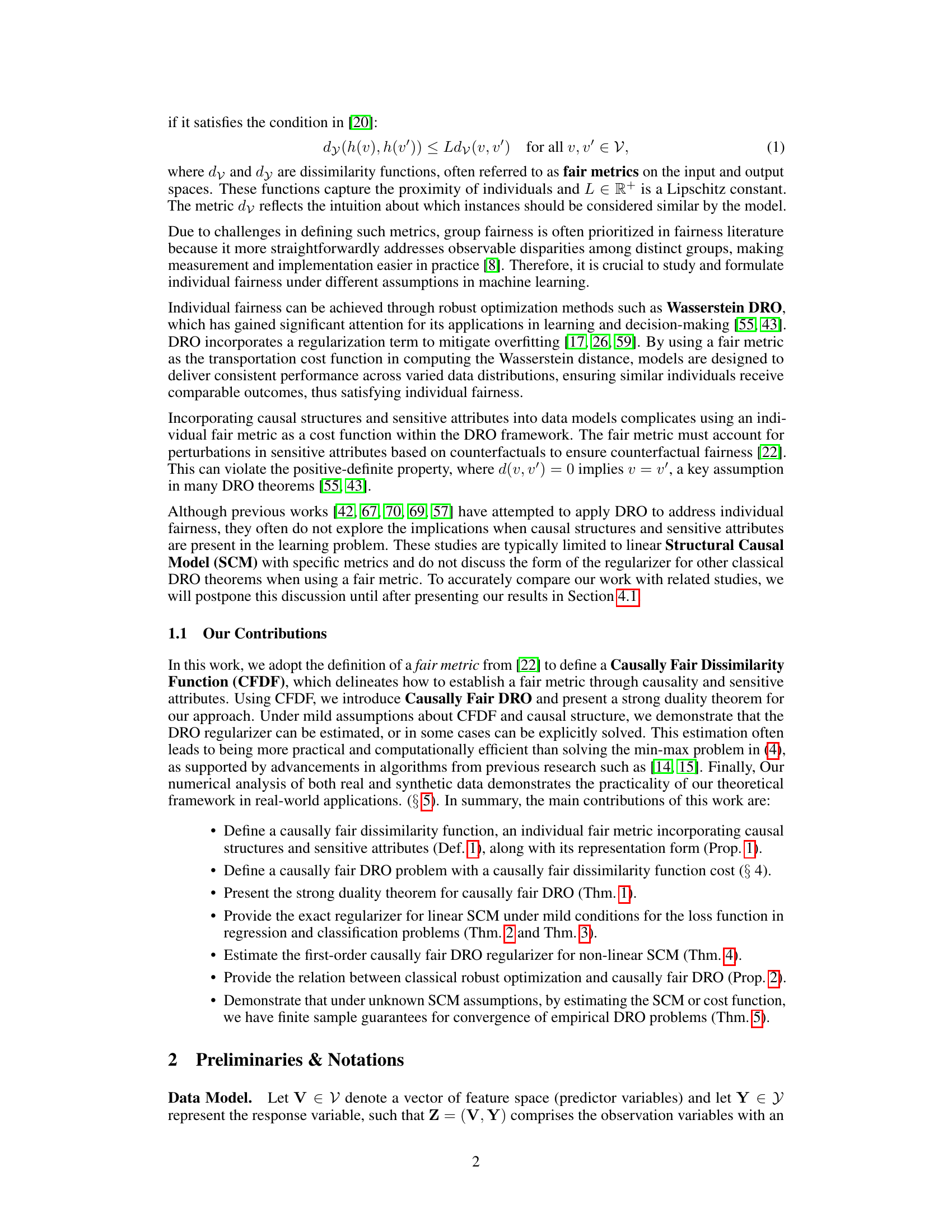

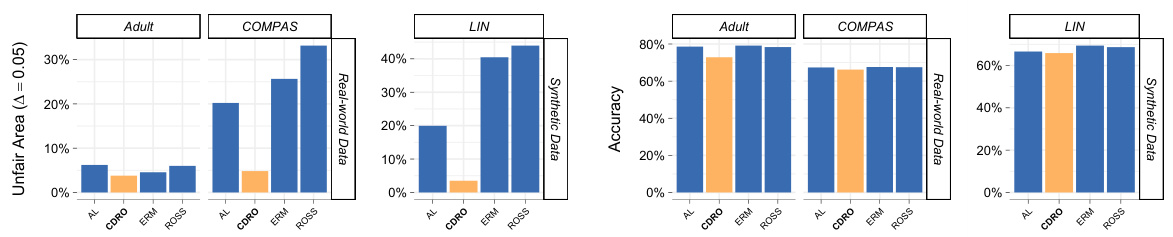

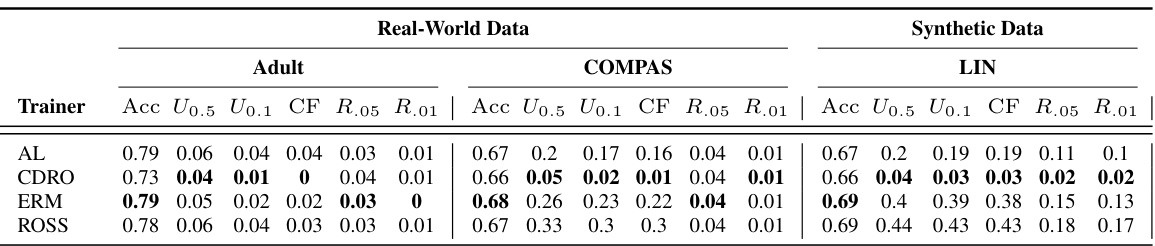

🔼 This table summarizes the results of a numerical experiment comparing four different training methods (CDRO, ERM, ROSS, AL) across three datasets (Adult, COMPAS, LIN) and two values of delta (0.05 and 0.01). The metrics evaluated include accuracy, unfair area (at two delta values), counterfactual unfairness, and non-robustness (against adversarial attacks at two delta values). Bold values highlight the best performing method for each dataset/metric combination. CDRO shows the lowest unfairness area with only a minor decrease in accuracy, indicating that it balances fairness and accuracy well.

read the caption

Table 1: The table presents the results of our numerical experiment, comparing various trainers based on their input sets in terms of accuracy (Acc, higher values are better), unfairness areas (U.05, lower values are better), unfairness areas (U.01, lower values are better), Counterfactual Unfair area (CF, lower values are better), the non-robust percentage concerning adversarial perturbation with radii 0.05 (R.05, lower values are better), and the non-robust percentage concerning adversarial perturbation with radii 0.01 (R.01, lower values are better). The top-performing techniques for each trainer, dataset, and metric are highlighted in bold. The findings demonstrate that CDRO excels in reducing unfair areas. The average standard deviation for CDRO is .029, while for the other methods, it is .031.

In-depth insights#

Causal Fair DRO#

The concept of “Causal Fair DRO” integrates causal inference and fairness into distributionally robust optimization (DRO). This approach is crucial because standard DRO methods often fail to address the nuances of individual fairness in the presence of causal relationships and sensitive attributes. Causal Fair DRO explicitly models causal structures using structural causal models (SCMs), which helps to understand how sensitive attributes influence outcomes and to design interventions that promote fairness. By incorporating a causally fair dissimilarity function as the cost function in the optimal transport problem within DRO, the method ensures that similar individuals receive similar treatment, regardless of their sensitive attributes, even under data distribution shifts. The dual formulation of the DRO problem is leveraged to create a tractable regularizer, which makes the approach computationally efficient. This regularizer can be estimated empirically, even without perfect knowledge of the underlying SCM, allowing for application in real-world scenarios with limited data and imperfect causal knowledge. Finite-sample error bounds further strengthen the approach’s robustness and applicability. This powerful combination of causal inference, fairness, and robustness offers a significant advancement in data-driven decision-making, addressing important ethical considerations and improving the reliability of data-driven systems.

DRO Regularization#

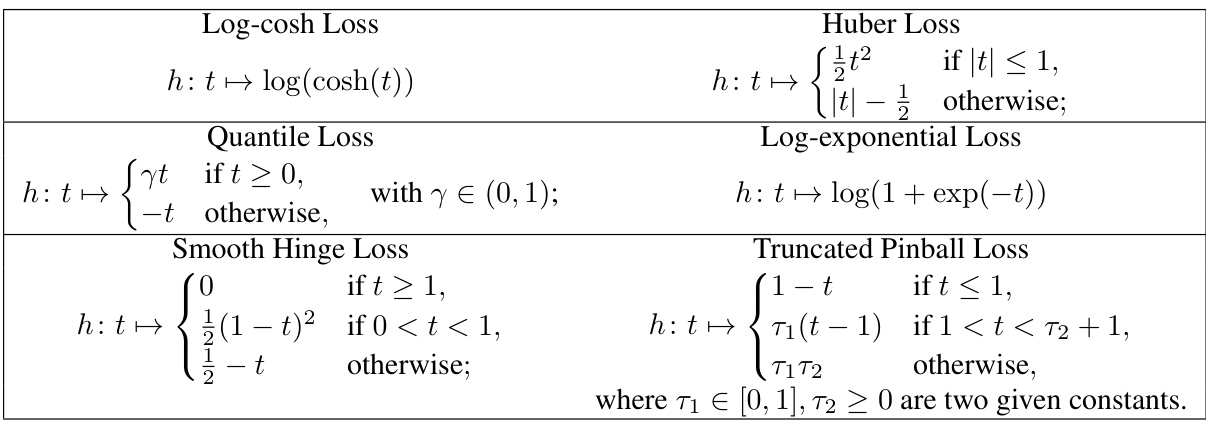

Distributionally Robust Optimization (DRO) offers a robust approach to machine learning by mitigating the impact of data uncertainty. DRO regularization is a key component, achieving robustness by incorporating a regularization term into the optimization problem. This term penalizes deviations from a nominal distribution, effectively smoothing the model’s response to variations in data. The choice of regularization function and its parameters significantly influence the model’s robustness and performance. Wasserstein DRO, a prominent variant, uses the Wasserstein distance to quantify distributional discrepancies, leading to more efficient and stable optimization. The Wasserstein distance considers the cost of transforming one distribution into another, reflecting the similarity between distributions. However, the computational cost of directly solving the min-max formulation of Wasserstein DRO can be significant. The strong duality theorem provides an efficient path, converting the problem into a tractable form involving a regularizer that can be estimated or solved explicitly, thereby enhancing computational feasibility. Causally fair DRO further extends this framework by integrating causal structures and individual fairness concerns, addressing discrimination in data by incorporating a causally fair dissimilarity function into the regularization term. This function ensures similar individuals receive similar treatments, promoting fairness. The finite-sample error bounds of causally fair DRO provides important theoretical guarantees and practical relevance.

SCM & Fairness#

The intersection of Structural Causal Models (SCMs) and fairness in machine learning is a crucial area of research. SCMs offer a powerful framework for understanding and modeling causal relationships within data, which is essential for addressing fairness concerns. Traditional fairness approaches often focus on statistical correlations, overlooking underlying causal mechanisms. By using SCMs, we can move beyond simply identifying disparities and investigate the causal pathways leading to unfair outcomes. This allows for a more nuanced approach to mitigating bias, by intervening on the causal structure rather than just the observed correlations. Counterfactual fairness, a key concept in causal fairness, relies heavily on SCMs. It allows us to ask “what if” questions and determine whether a model’s predictions would change if a sensitive attribute (e.g., race, gender) were altered. This is crucial for evaluating whether bias stems from direct discrimination or confounding factors. However, integrating causal reasoning into machine learning algorithms is challenging. Defining appropriate metrics and designing algorithms that handle causal uncertainty is an active area of research. Further work is needed to make these approaches practical and scalable for real-world applications, especially when dealing with complex systems and high-dimensional data.

Empirical DRO#

Empirical DRO (Distributionally Robust Optimization) tackles the challenge of optimizing decisions under real-world data uncertainty by using the empirical distribution. It avoids the need for full distributional knowledge, which is often unavailable or difficult to obtain and instead leverages the observed data directly. This approach is practically advantageous, as it sidesteps the computational complexity associated with finding the worst-case distribution within a given ambiguity set. However, the accuracy of empirical DRO is directly tied to the quality and representativeness of the empirical distribution. Insufficient data or biases within the data sample can lead to suboptimal or even misleading results. Consequently, the finite-sample performance and error bounds of empirical DRO are crucial considerations in evaluating its reliability and ensuring robust decision-making, particularly in critical applications. A key focus is developing methods to estimate the DRO regularizer, which determines the level of robustness. The choice of the underlying metric (e.g. Wasserstein) also plays a significant role in shaping the DRO problem and needs careful consideration. Careful selection of the dissimilarity function (or metric) and robust estimation techniques are paramount for empirical DRO to achieve the desired resilience against data uncertainty while preserving practicality and effectiveness.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore extensions to more complex causal models, moving beyond the additive noise models used here. Investigating the impact of unobserved confounding on the proposed methods would also be valuable. Furthermore, developing more efficient algorithms for estimating the causally fair dissimilarity function and the regularizer in high-dimensional settings is crucial for practical applications. Finally, a deeper investigation into the theoretical guarantees of the empirical DRO problem under weaker assumptions and its implications for fairness in real-world scenarios warrants further research. Evaluating the robustness of the framework across a wider variety of datasets and machine learning models, especially those with inherent non-linearities, would add practical significance to the proposed approach.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure displays the results of a numerical experiment comparing four different methods for mitigating individual unfairness in machine learning models: Causally Fair DRO (CDRO), Empirical Risk Minimization (ERM), Ross method, and Adversarial Learning. The left panel shows the unfair area percentage (UAI) for each method, a lower UAI indicating better fairness, on three different datasets (Adult, COMPAS, and synthetic linear SCM) with a sensitivity threshold (A) set to 0.05. The right panel displays the prediction accuracy for the same methods and datasets. The figure highlights the trade-off between fairness and accuracy, showing how CDRO achieves better fairness but may have slightly lower accuracy compared to other methods.

read the caption

Figure 1: Displays the findings from our numerical experiment, assessing the performance of DRO across different models and datasets. (left) Bar plot showing the comparison of models based on the unfair area percentage (lower values are better) for A = .05. (right) Bar plot comparing methods by prediction accuracy performance (higher values are better).

🔼 This figure displays the results of a numerical experiment comparing different methods for mitigating individual unfairness in machine learning models. The left panel shows the unfair area (percentage of individuals deemed unfairly treated) for each method across three datasets (Adult, COMPAS, and a synthetic dataset), using a threshold of A = 0.05. Lower values indicate better fairness. The right panel shows the prediction accuracy of the models on the same datasets. Higher values indicate better performance. The comparison helps to understand the trade-off between fairness and accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 1: Displays the findings from our numerical experiment, assessing the performance of DRO across different models and datasets. (left) Bar plot showing the comparison of models based on the unfair area percentage (lower values are better) for A = .05. (right) Bar plot comparing methods by prediction accuracy performance (higher values are better).

🔼 This figure presents the results of a numerical experiment comparing different methods for mitigating individual unfairness in machine learning models. The left panel shows a bar chart illustrating the unfair area percentage for each method on three datasets (Adult, COMPAS, and a synthetic linear SCM dataset), with a lower percentage indicating better fairness. The right panel displays a bar chart comparing the prediction accuracy of each method on the same datasets, where higher accuracy is desirable. The results demonstrate the trade-off between fairness and accuracy, suggesting that some methods achieve better fairness at the expense of some accuracy and vice versa.

read the caption

Figure 1: Displays the findings from our numerical experiment, assessing the performance of DRO across different models and datasets. (left) Bar plot showing the comparison of models based on the unfair area percentage (lower values are better) for A = .05. (right) Bar plot comparing methods by prediction accuracy performance (higher values are better).

More on tables

🔼 This table summarizes the results of numerical experiments comparing four different training methods (AL, CDRO, ERM, ROSS) across three datasets (Adult, COMPAS, LIN) using six metrics (accuracy, unfairness area at δ=0.05, unfairness area at δ=0.01, counterfactual unfairness, non-robustness area at δ=0.05, non-robustness area at δ=0.01). The top performer for each metric and dataset is highlighted. The results show that CDRO generally outperforms other methods in terms of reducing unfairness.

read the caption

Table 1: The table presents the results of our numerical experiment, comparing various trainers based on their input sets in terms of accuracy (Acc, higher values are better), unfairness areas (U.05, lower values are better), unfairness areas (U.01, lower values are better), Counterfactual Unfair area (CF, lower values are better), the non-robust percentage concerning adversarial perturbation with radii 0.05 (R.05, lower values are better), and the non-robust percentage concerning adversarial perturbation with radii 0.01 (R.01, lower values are better). The top-performing techniques for each trainer, dataset, and metric are highlighted in bold. The findings demonstrate that CDRO excels in reducing unfair areas. The average standard deviation for CDRO is .029, while for the other methods, it is .031.

🔼 This table presents the results of a numerical experiment comparing four different training methods (AL, CDRO, ERM, ROSS) across three datasets (Adult, COMPAS, LIN). The metrics evaluated are accuracy, unfairness areas at two different radii (0.05 and 0.01), counterfactual unfairness, and non-robustness to adversarial perturbations at the same radii. The results show the performance of each method in terms of balancing accuracy and fairness.

read the caption

Table 1: The table presents the results of our numerical experiment, comparing various trainers based on their input sets in terms of accuracy (Acc, higher values are better), unfairness areas (U0.5, lower values are better), unfairness areas (U0.1, lower values are better), Counterfactual Unfair area (CF, lower values are better), the non-robust percentage concerning adversarial perturbation with radii 0.05 (R.05, lower values are better), and the non-robust percentage concerning adversarial perturbation with radii 0.01 (R.01, lower values are better). The top-performing techniques for each trainer, dataset, and metric are highlighted in bold. The findings demonstrate that CDRO excels in reducing unfair areas. The average standard deviation for CDRO is .029, while for the other methods, it is .031.

Full paper#