TL;DR#

Current HSI techniques struggle with diverse object dynamics and rely on privileged information, limiting real-world applications. This paper addresses these limitations by focusing on vision-language directed object rearrangement using a physical humanoid. The approach is limited by the use of a specific humanoid model, and the generalizability to completely unseen objects and scenarios remains a challenge.

The proposed solution, HumanVLA, uses a teacher-student framework combining goal-conditioned reinforcement learning and behavior cloning. Key innovations include an adversarial motion prior, geometry encoding for objects, in-context path planning, and a novel active rendering technique to enhance perception. The effectiveness of HumanVLA is validated through extensive experiments using the new HITR dataset, showing its ability to perform various complex tasks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it tackles a crucial challenge in robotics: general-purpose object rearrangement by physical humanoids directed by vision and language. It introduces a novel approach, HumanVLA, and a new dataset, HITR, pushing the boundaries of embodied AI research. The active rendering technique and the curriculum learning strategies are valuable contributions that will enable new research avenues. The results demonstrate significant progress towards more versatile and adaptable robots, ultimately impacting various applications.

Visual Insights#

🔼 The figure shows three different scenarios of object rearrangement by a humanoid robot, guided by both visual input and natural language commands. In each scenario, the robot is given a task, such as ‘I’m cleaning the room. Please push the small brown table next to the bed.’ The top row shows the initial scene, while the bottom row displays the robot completing the task using vision and language. The image highlights the system’s ability to understand natural language instructions, perceive its environment, and execute actions to manipulate objects.

read the caption

Figure 1: HumanVLA performs various object rearrangement tasks directed by the egocentric vision and natural language instructions.

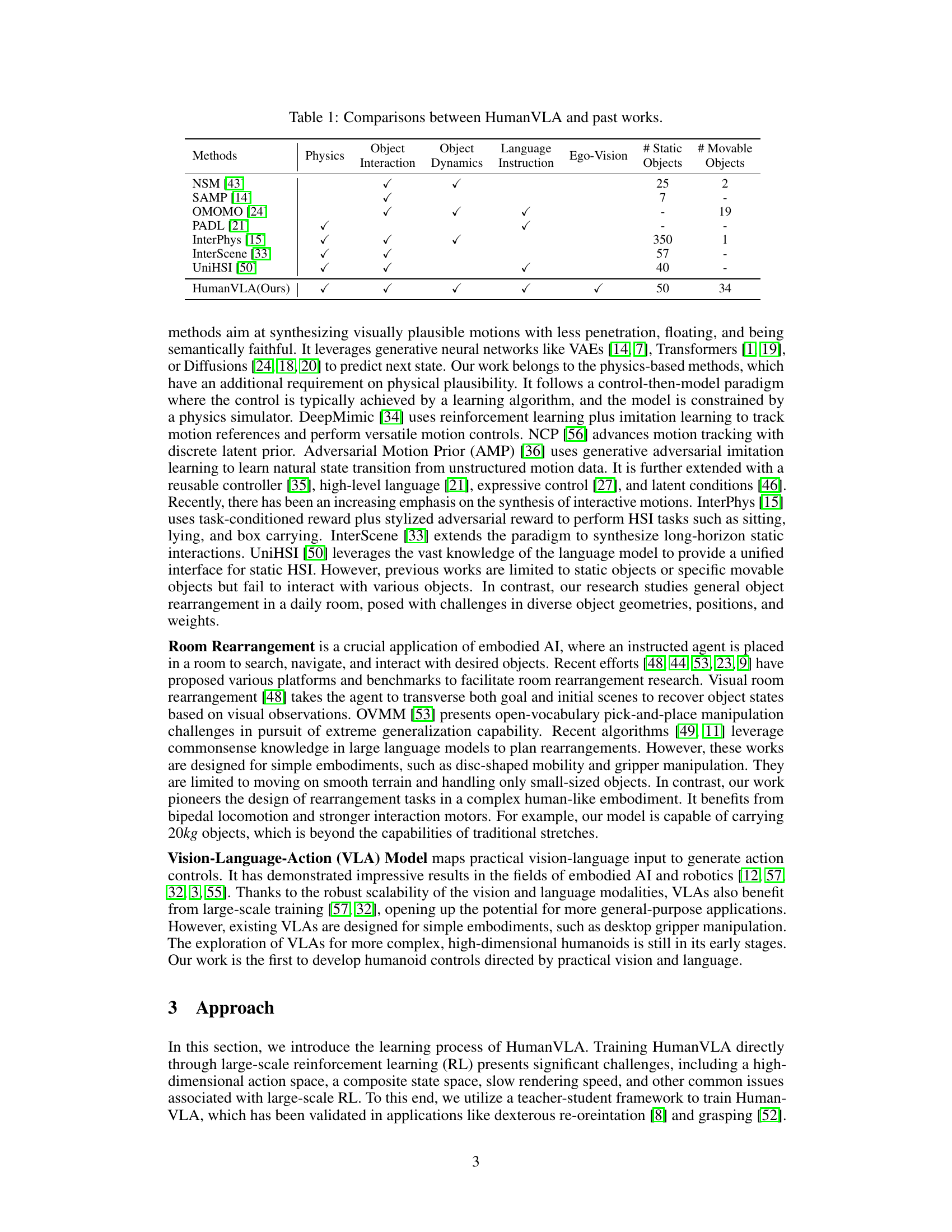

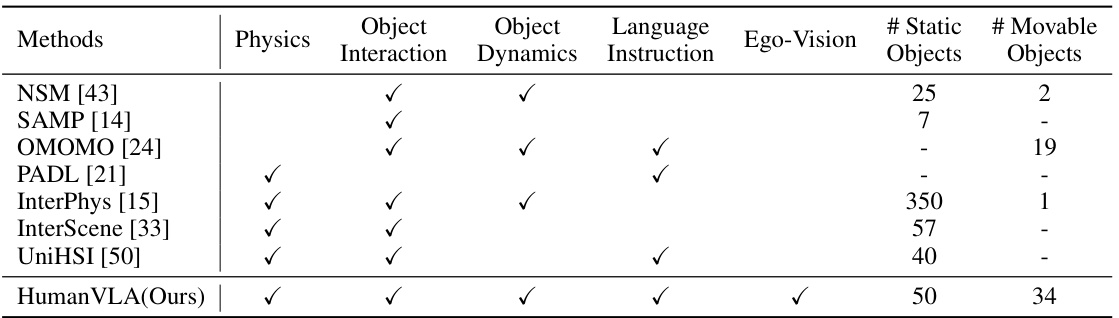

🔼 This table compares the capabilities of HumanVLA with several previous works on Human-Scene Interaction (HSI). The comparison is made across several key aspects: whether the methods use physics simulation, handle object interaction and dynamics, are guided by language instructions, utilize egocentric vision, and the number of static and movable objects involved in the experiments. HumanVLA stands out by incorporating all these aspects.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparisons between HumanVLA and past works.

In-depth insights#

Vision-Language HSI#

Vision-Language HSI (Human-Scene Interaction) represents a significant advancement in robotics and AI, aiming to bridge the gap between perception and action through a combination of visual and linguistic inputs. A key challenge lies in effectively integrating visual data with natural language instructions to guide complex interactions. This integration requires robust object recognition, scene understanding, and natural language processing capabilities to translate human commands into actionable robot movements. The development of such systems requires large, diverse datasets that capture the nuances of human-scene interaction in realistic environments, including variations in lighting, object placement, and human language. Furthermore, effective algorithms are needed to handle the inherent ambiguity and uncertainty present in both vision and language, ensuring reliable and safe robot behavior. Future work should focus on improving the robustness and generalization capabilities of Vision-Language HSI systems, allowing robots to adapt to unseen environments and perform more complex manipulation tasks. This field also presents ethical considerations, emphasizing the necessity for careful design and deployment of such systems to prevent potential misuse or harmful consequences.

Teacher-Student RL#

Teacher-Student Reinforcement Learning (RL) is a powerful paradigm for tackling complex RL problems. It leverages a pre-trained teacher policy to guide the learning of a student agent. The teacher, typically trained via a more computationally expensive method (e.g., goal-conditioned RL), provides demonstrations or expert knowledge. The student then learns to mimic the teacher’s behavior, often using a less complex algorithm like behavior cloning or imitation learning. This approach is particularly beneficial when direct RL training is challenging due to high dimensionality or sparse rewards. The key advantage is efficiency: the student requires far less training data and computational resources than training a high-performing agent from scratch. However, the student’s performance is inherently limited by the teacher’s capabilities. If the teacher policy is suboptimal or incomplete, the student will also be limited. Carefully designing and training the teacher policy is thus crucial for success. Furthermore, transferring the teacher’s knowledge effectively to the student is essential, which may require thoughtful distillation or knowledge representation techniques. Despite these potential limitations, Teacher-Student RL remains a valuable tool for simplifying complex RL problems and enhancing learning efficiency.

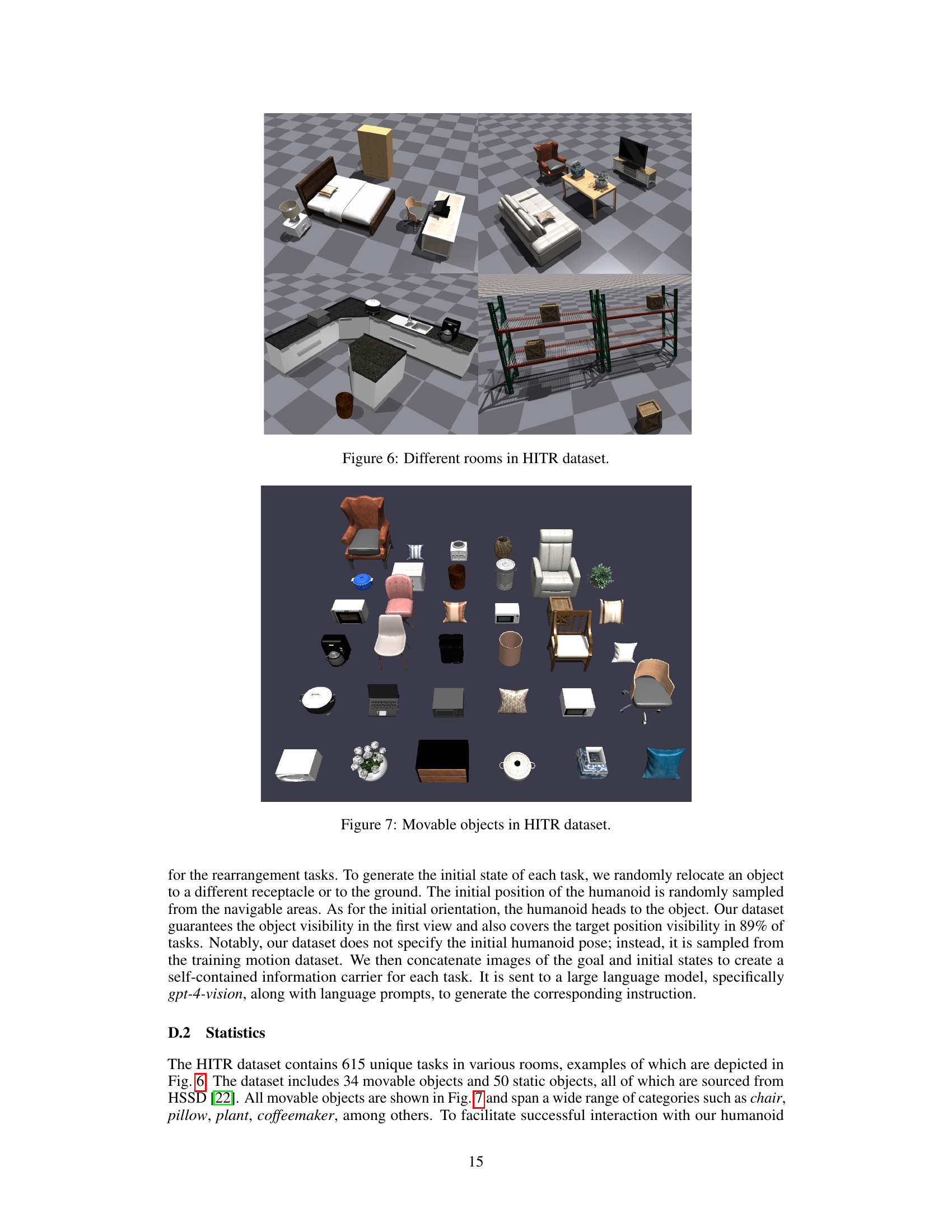

HITR Dataset#

The Human-in-the-Room (HITR) dataset represents a notable contribution, addressing limitations in existing datasets for embodied AI research. Its focus on general object rearrangement tasks performed by a physically interactive humanoid is a significant departure from datasets featuring simpler robotic agents or constrained object dynamics. The inclusion of diverse room layouts, a range of object types (static and movable, varied sizes and weights), and natural language instructions for task completion makes HITR well-suited for training robust and generalizable vision-language-action models. The dataset’s use of a physically realistic humanoid with whole-body control adds complexity and realism, enabling the development of more human-like agent capabilities. The detailed documentation regarding object properties, room layouts, and generated instructions, along with the availability of the data and code, facilitates reproducibility and fosters community contributions. However, potential limitations may include the relatively small number of objects currently included and the need for more extensive analysis regarding the variety and complexity of the generated language instructions. Future iterations of HITR could benefit from expanding the object diversity, and including more intricate tasks involving multiple objects or sequential actions to better align with real-world scenarios.

Active Rendering#

Active rendering, in the context of vision-language-action models for humanoid robots, addresses the challenge of obtaining high-quality visual information for effective control. Standard camera viewpoints might not adequately capture crucial human-object interactions. Active rendering enhances this by dynamically adjusting the camera’s pose, particularly focusing on the object of manipulation. This intelligent gaze control leverages calculated head orientations, achieved through inverse kinematics, to ensure that the camera viewpoint prioritizes informative perception of the ongoing task, rather than simply passively recording the scene. This improvement significantly enhances the perception quality available to the vision-language-action model, which improves overall performance of object rearrangement tasks. The active rendering component is integral to the success of the proposed model, showcasing the benefits of actively optimizing sensor data for enhanced performance in complex robotic tasks. Ultimately, it shows that proactive data acquisition is crucial for improving robustness and generalization in real-world robotic applications that rely on vision-language integration.

Generalization Limits#

A section on “Generalization Limits” in a research paper would explore the boundaries of a model’s capabilities. It would likely discuss situations where the model fails to generalize effectively, such as encountering novel object types, unseen environments, or variations in task instructions. The analysis might delve into the reasons behind these limitations, possibly attributing them to factors like the training data’s diversity and representativeness, the model’s architecture and complexity, or the choice of evaluation metrics. A strong section would provide concrete examples of generalization failures, quantifying the performance drop and offering potential solutions, such as data augmentation, domain adaptation techniques, or model regularization. Finally, the discussion of generalization limits would provide valuable insights into the model’s robustness and the future research directions to improve its generalization capabilities. Addressing these limitations is crucial for developing truly robust AI systems capable of handling real-world complexities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 The figure illustrates the process of training the HumanVLA-Teacher policy. It uses a goal-conditioned reinforcement learning approach combined with adversarial motion priors. The teacher policy receives the environment state (St), including object pose, geometry, waypoint, and goal coordinates. It then produces an action (at) that’s fed into a physics simulator, resulting in the next state (St+1). The learning process involves maximizing a reward (rt) composed of a goal-conditioned task reward and a style reward. The style reward utilizes an adversarial motion discriminator to ensure realistic motion synthesis. The motion discriminator is trained separately, using a motion dataset for reference.

read the caption

Figure 2: An overview of learning state-based HumanVLA-Teacher policy using goal-conditioned reinforcement learning and adversarial motion prior.

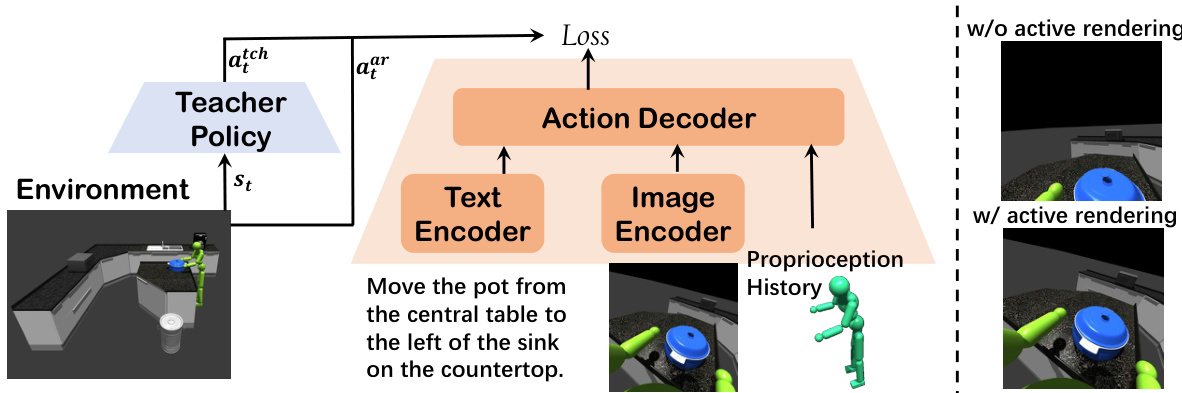

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of HumanVLA, a vision-language-action model. The left side shows the teacher-student framework used for training. The teacher policy receives privileged information (state) and generates actions. These actions are mimicked by the student (HumanVLA), which receives egocentric vision, language instructions, proprioception and history. The right side showcases a comparison of egocentric vision with and without active rendering. Active rendering focuses the camera on the object of interest, resulting in a clearer and more informative visual input for HumanVLA.

read the caption

Figure 3: Left: An overview of learning HumanVLA by mimicking teacher action and active rendering action. Right: Comparison between w/ and w/o active rendering. Active rendering leads to a more informative perception of human-object relationships.

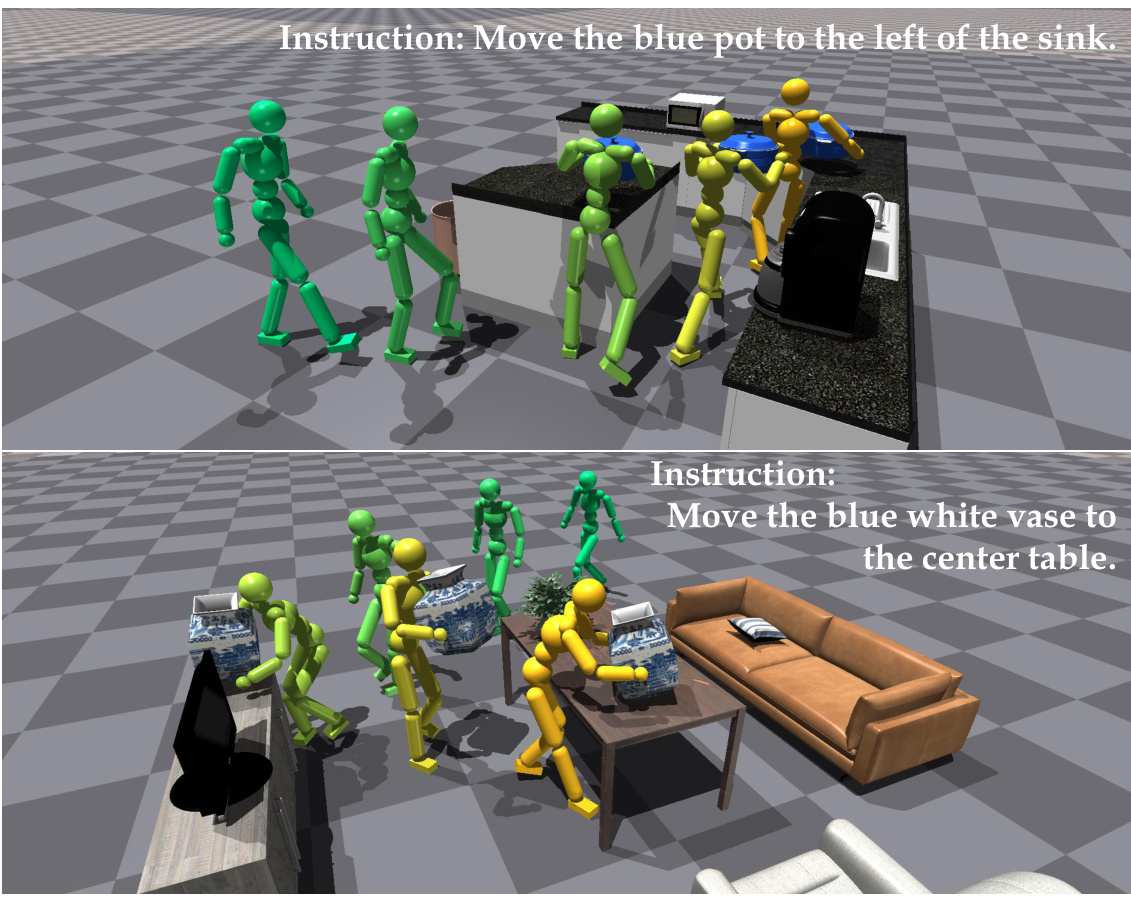

🔼 This figure shows two examples of the HumanVLA model performing object rearrangement tasks. In each example, a sequence of images displays the humanoid robot moving objects according to a given natural language instruction. The color of the humanoid changes from green to yellow to illustrate the progress of the task. This visualization demonstrates the model’s ability to successfully complete object rearrangement tasks as directed by language.

read the caption

Figure 4: Qualitative results. The color transitions from green to yellow as the task progresses.

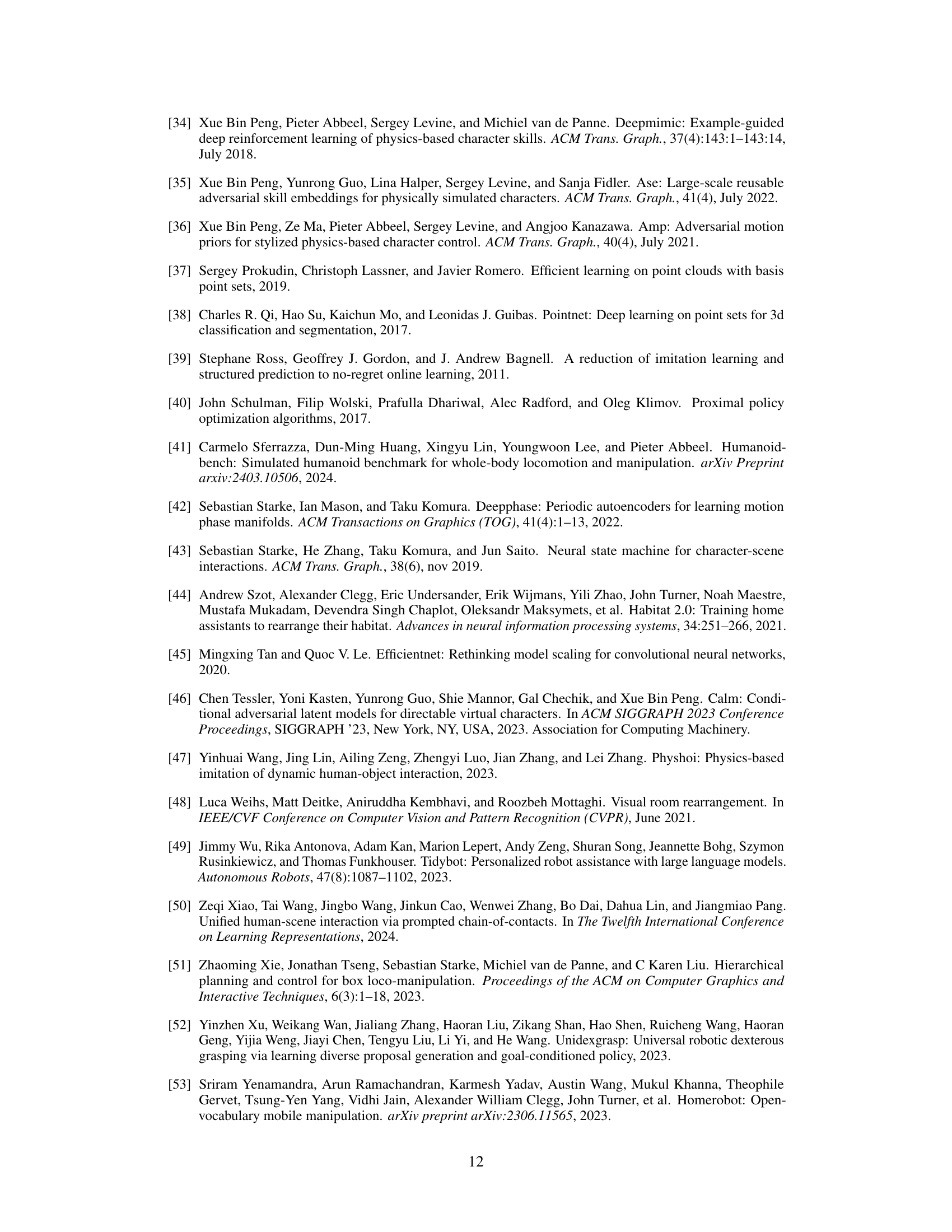

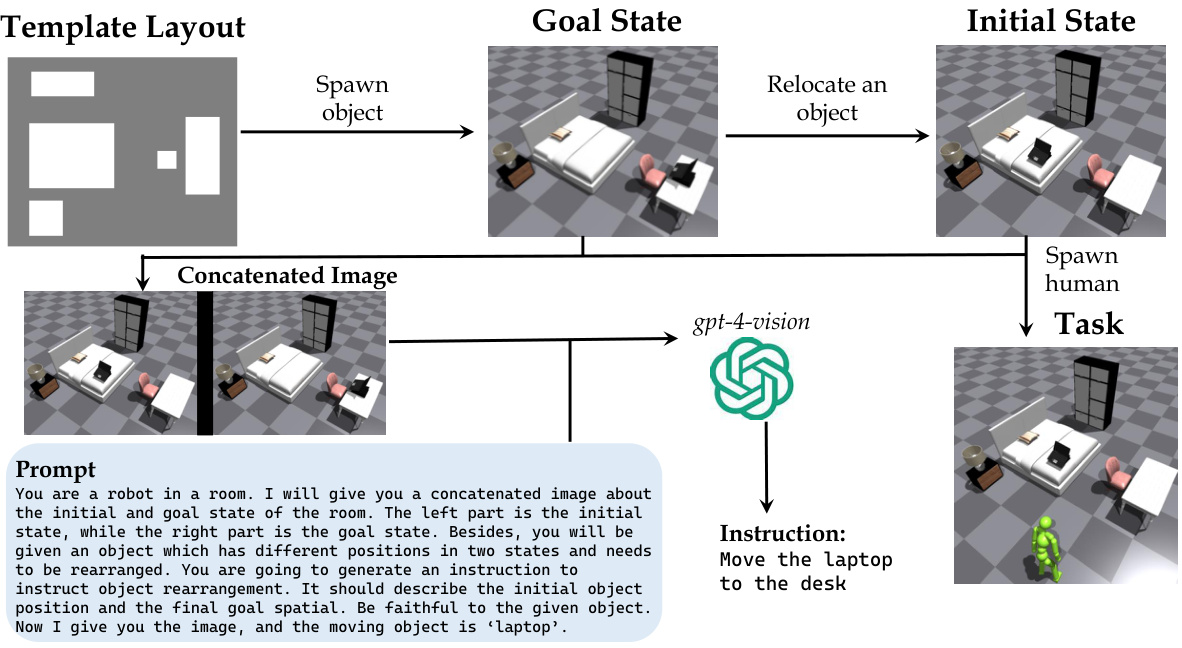

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of generating tasks for the Human-in-the-Room (HITR) dataset. It starts with a template room layout. Then, an object is spawned and relocated to create the goal state. A human is also spawned in the scene. The initial and goal states are concatenated into a single image, which is fed to a large language model (GPT-4-vision) along with a prompt to generate natural language instructions for the object rearrangement task. These instructions, along with the concatenated image, serve as the input for training the model. The figure visually represents this workflow, showing each step from template room layout to the generation of instructions.

read the caption

Figure 5: The task generation process of HITR dataset.

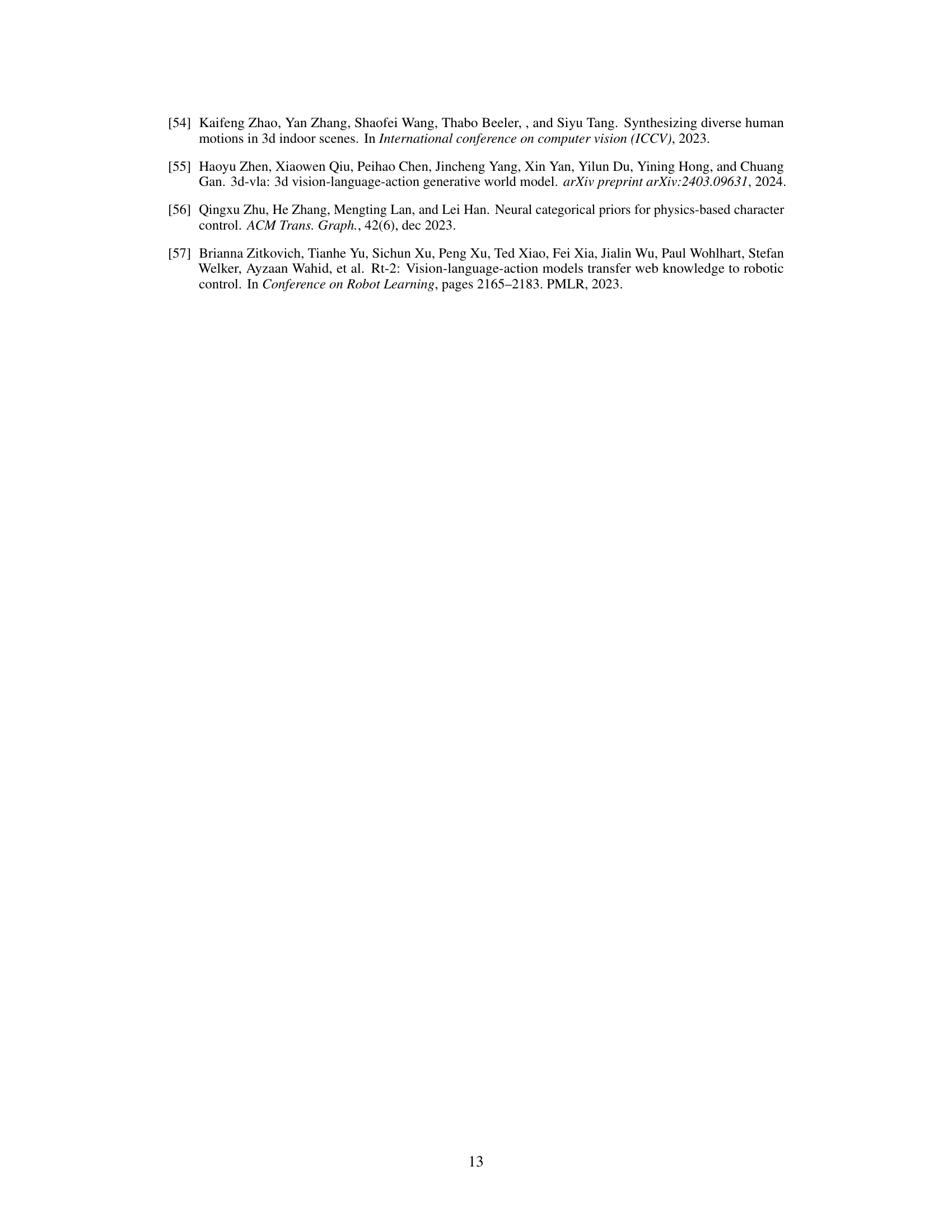

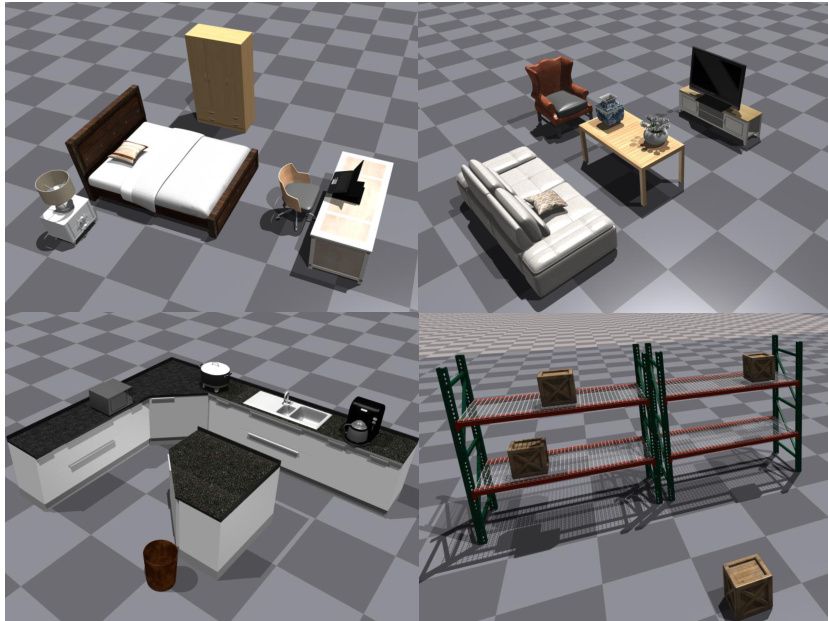

🔼 This figure shows four different room layouts included in the Human-in-the-Room (HITR) dataset. Each layout represents a different room type (bedroom, living room, kitchen, and warehouse) and is populated with various objects to create diverse scenes for the object rearrangement tasks. The layouts vary in size, object arrangement, and overall aesthetic.

read the caption

Figure 6: Different rooms in HITR dataset.

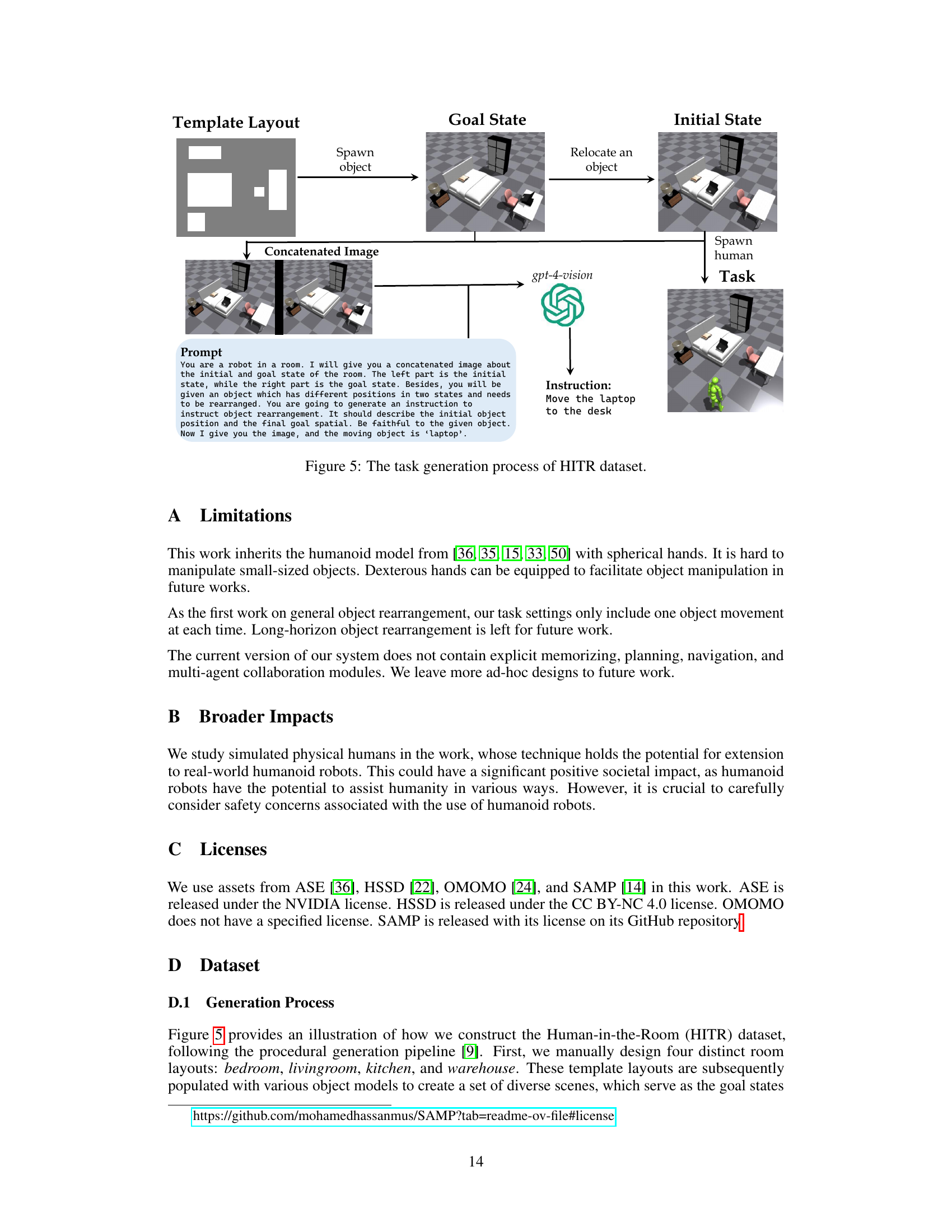

🔼 This figure shows the 34 movable objects that are included in the Human-in-the-Room (HITR) dataset. These objects vary in size, shape, and function, representing a diverse range of household items. The diversity of objects is crucial for evaluating the generalization capabilities of the HumanVLA model, as it needs to learn how to interact and rearrange a wide variety of items, not just a limited set of pre-defined objects.

read the caption

Figure 7: Movable objects in HITR dataset.

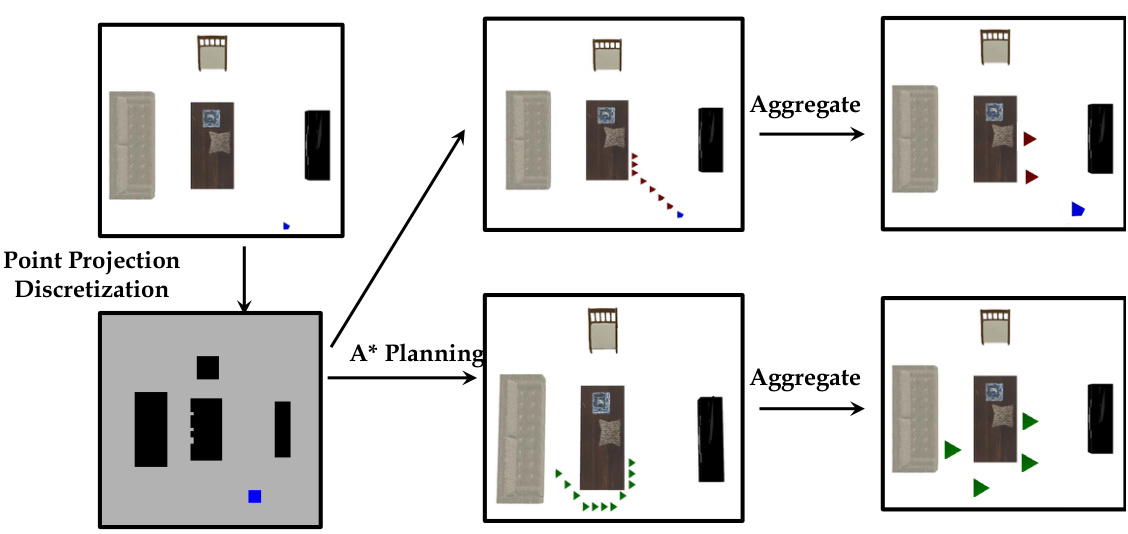

🔼 This figure illustrates the path planning process used in the paper’s method. A* algorithm is used to plan two paths: one from the humanoid’s starting position to the target object and a second path from the object to the final goal location. The paths are represented as a series of waypoints. The waypoints are then simplified into a sparser set that maintains the overall path direction, making navigation more efficient. The humanoid follows these simplified waypoints during execution, moving towards each waypoint until it reaches it within a 50cm distance, then proceeding to the next. The process is shown visually, with colors representing the different stages of the path.

read the caption

Figure 8: An overview of the path planning process. The blue mark denotes the initial position. Red marks denote the path from the initial position to the object. Green marks denote the path from the object to the goal.

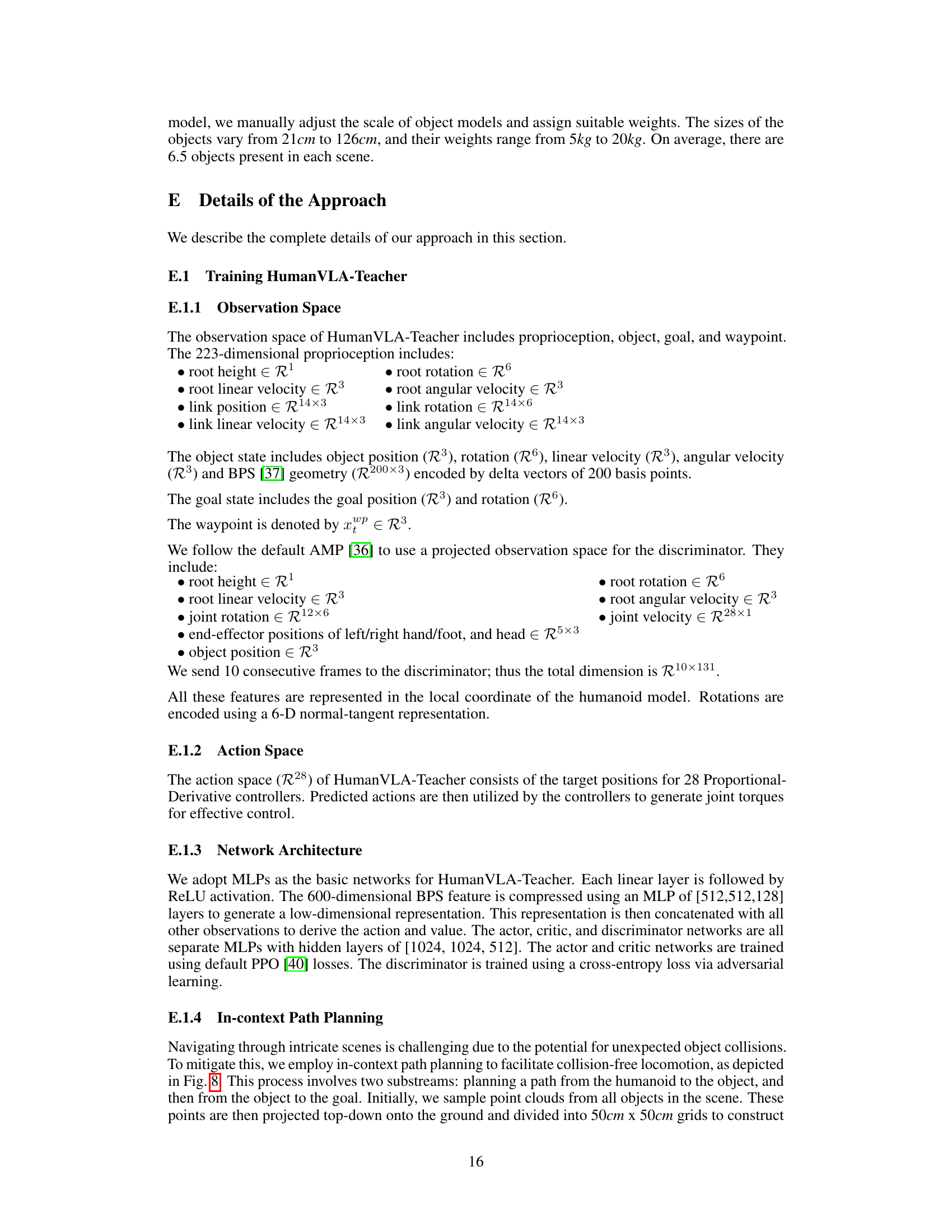

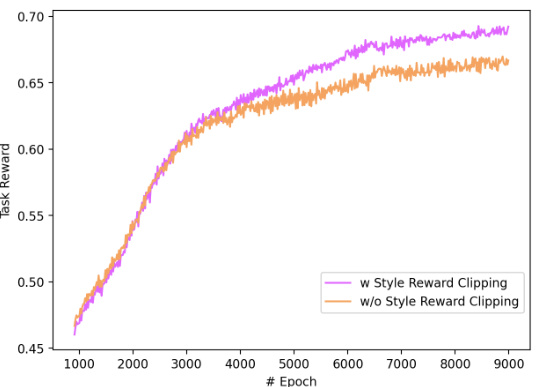

🔼 This figure shows the learning curves for the HumanVLA-Teacher model with and without style reward clipping. The y-axis represents the task reward, indicating the model’s performance. The x-axis shows the number of epochs during training. The comparison demonstrates the impact of the style reward clipping mechanism on the learning process and overall performance.

read the caption

Figure 9: Learning curve comparison w/ and w/o style reward clipping.

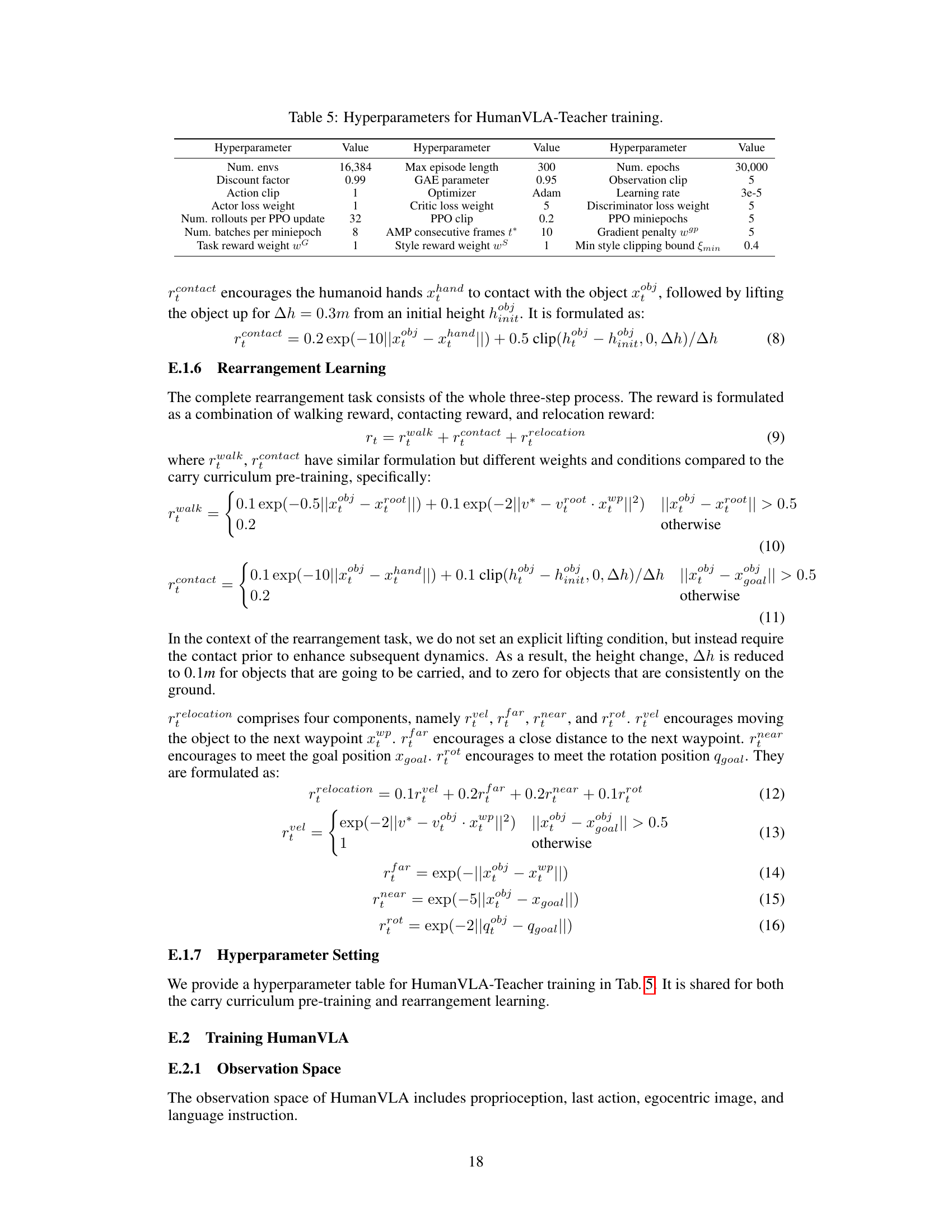

🔼 This figure shows the learning curves for task reward with and without style reward clipping during the training process of HumanVLA-Teacher. The x-axis represents the number of epochs, and the y-axis shows the task reward. The graph illustrates the impact of style reward clipping on the learning process, showing the difference in the reward obtained with and without this technique.

read the caption

Figure 9: Learning curve comparison w/ and w/o style reward clipping.

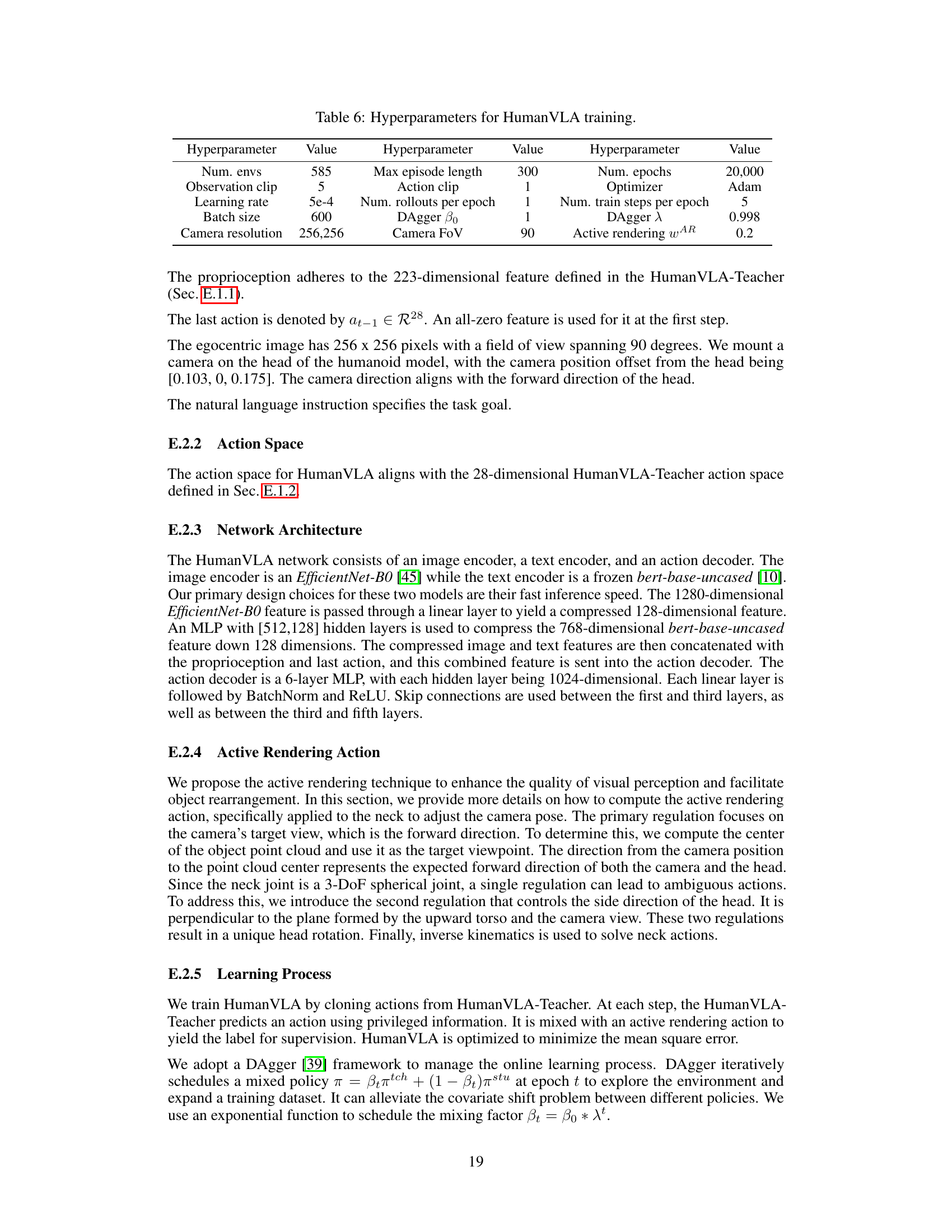

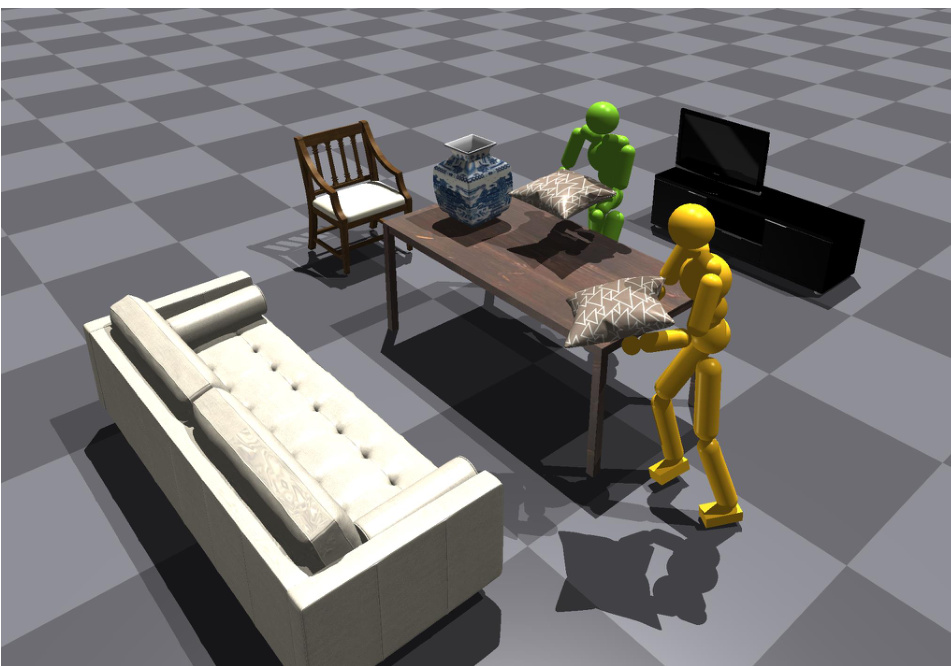

🔼 This figure compares the performance of the HumanVLA model with and without path planning. Two humanoids are shown attempting to move a pillow to a sofa. The humanoid without path planning fails to efficiently navigate around obstacles, while the one with path planning successfully plans a route around the table to reach the sofa.

read the caption

Figure 11: Comparison w/ and w/o path planning. The green humanoid without path guidance fails to get close to the sofa, while the yellow humanoid with path guidance learns to go around the central table. Instruction: Move the pillow to the sofa.

🔼 This figure shows two examples of object rearrangement tasks performed by HumanVLA, along with the corresponding instructions. The top example shows the robot moving a red chair in front of a table. The bottom example shows the robot placing a box on the bottom shelf of a rack. The images show the sequence of actions performed by the robot to complete the task.

read the caption

Figure 12: Additional qualitative results.

More on tables

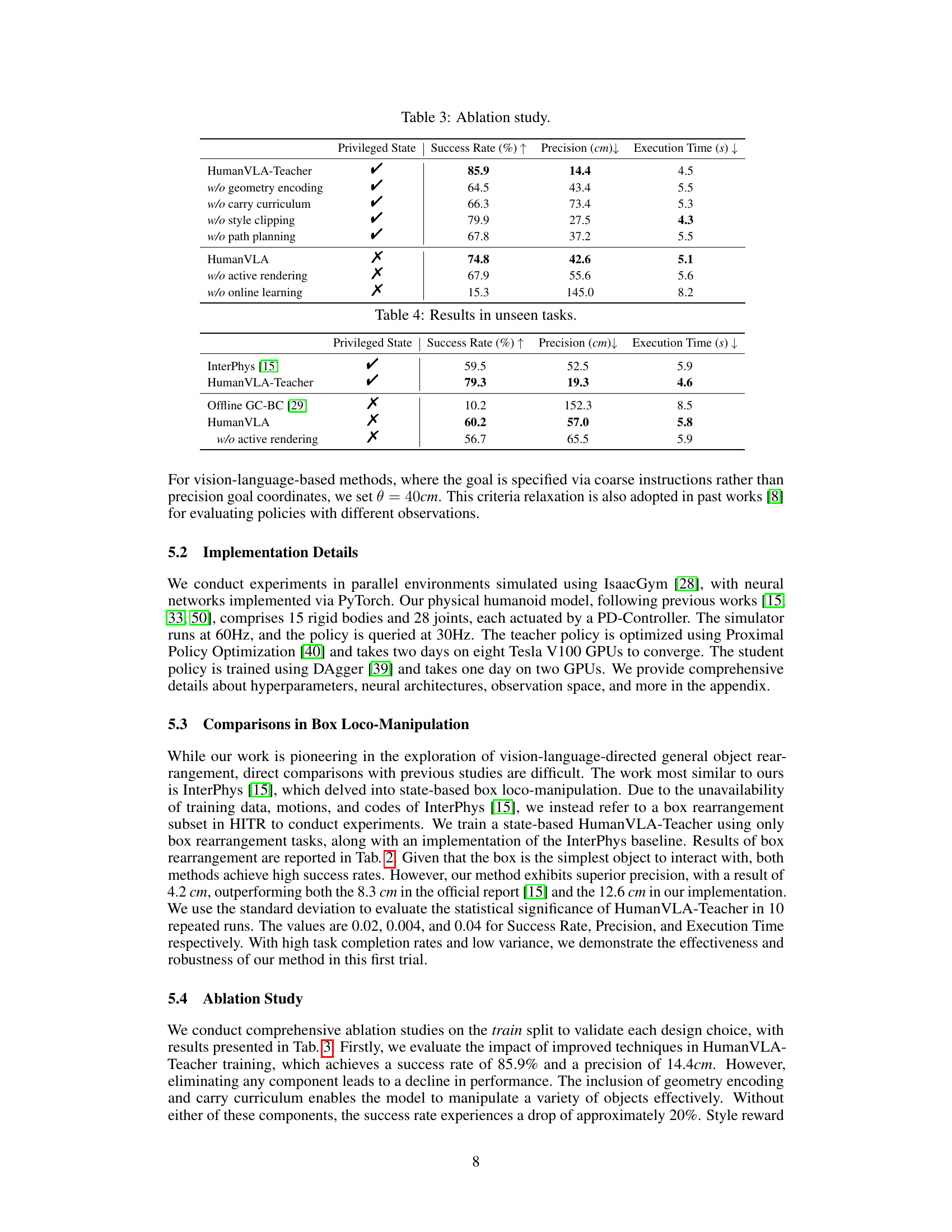

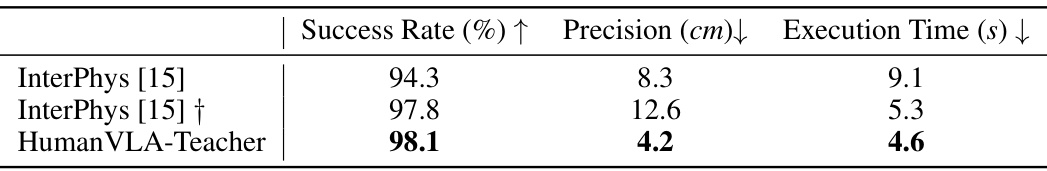

🔼 This table presents the results of box rearrangement experiments. It compares the performance of three different methods: InterPhys [15] (as reported in the original paper), InterPhys [15] † (the authors’ own re-implementation of InterPhys), and Human VLA-Teacher (the authors’ proposed method). The metrics used for comparison are Success Rate (percentage of successful rearrangements), Precision (average distance in centimeters between the final object position and the goal position), and Execution Time (average time in seconds to complete the task). The results show that Human VLA-Teacher outperforms both versions of InterPhys across all three metrics.

read the caption

Table 2: Results in box rearrangement. † denotes our implementation.

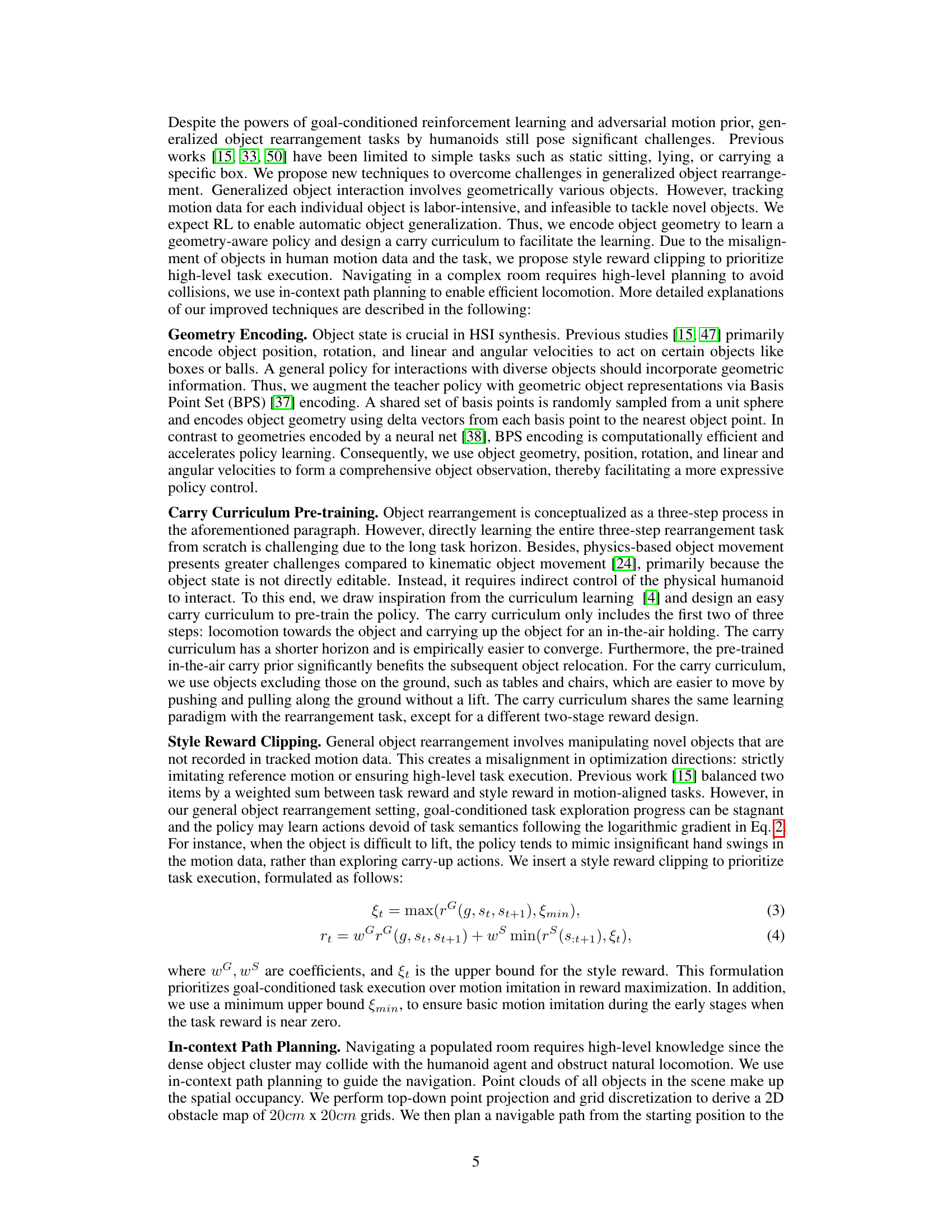

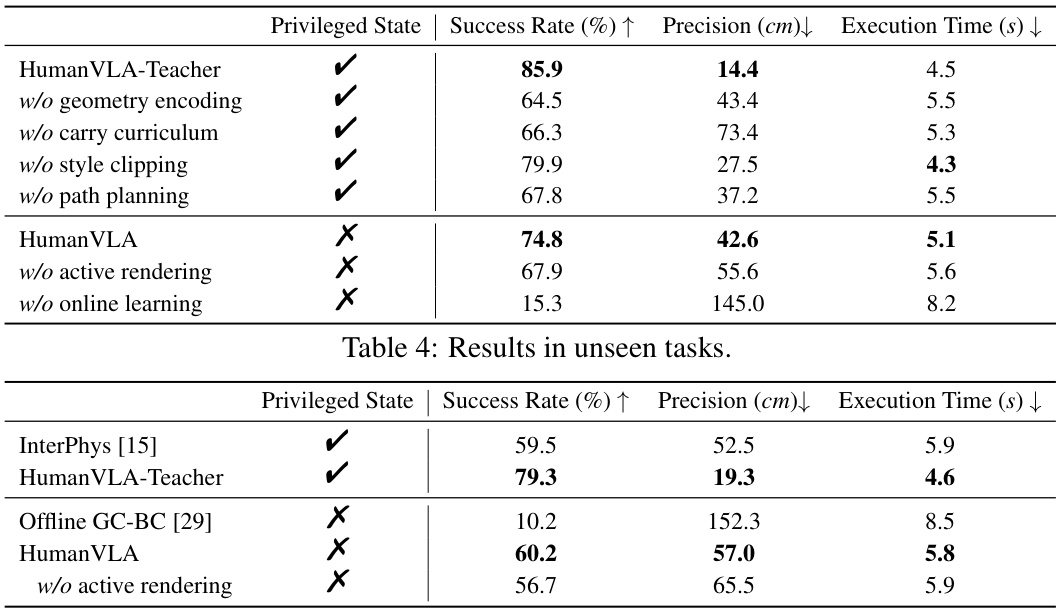

🔼 This table presents the results of the HumanVLA model and its ablation studies on unseen tasks. It shows the success rate (percentage of tasks successfully completed), precision (average distance in cm between the final object position and the goal position), and execution time (in seconds) for different model configurations. The configurations include the complete HumanVLA model and versions with various components removed (geometry encoding, carry curriculum, style clipping, path planning, active rendering, and online learning). The table also includes results from InterPhys [15] and Offline GC-BC [29] methods for comparison. The ‘Privileged State’ column indicates whether the model used privileged information (such as object poses).

read the caption

Table 4: Results in unseen tasks.

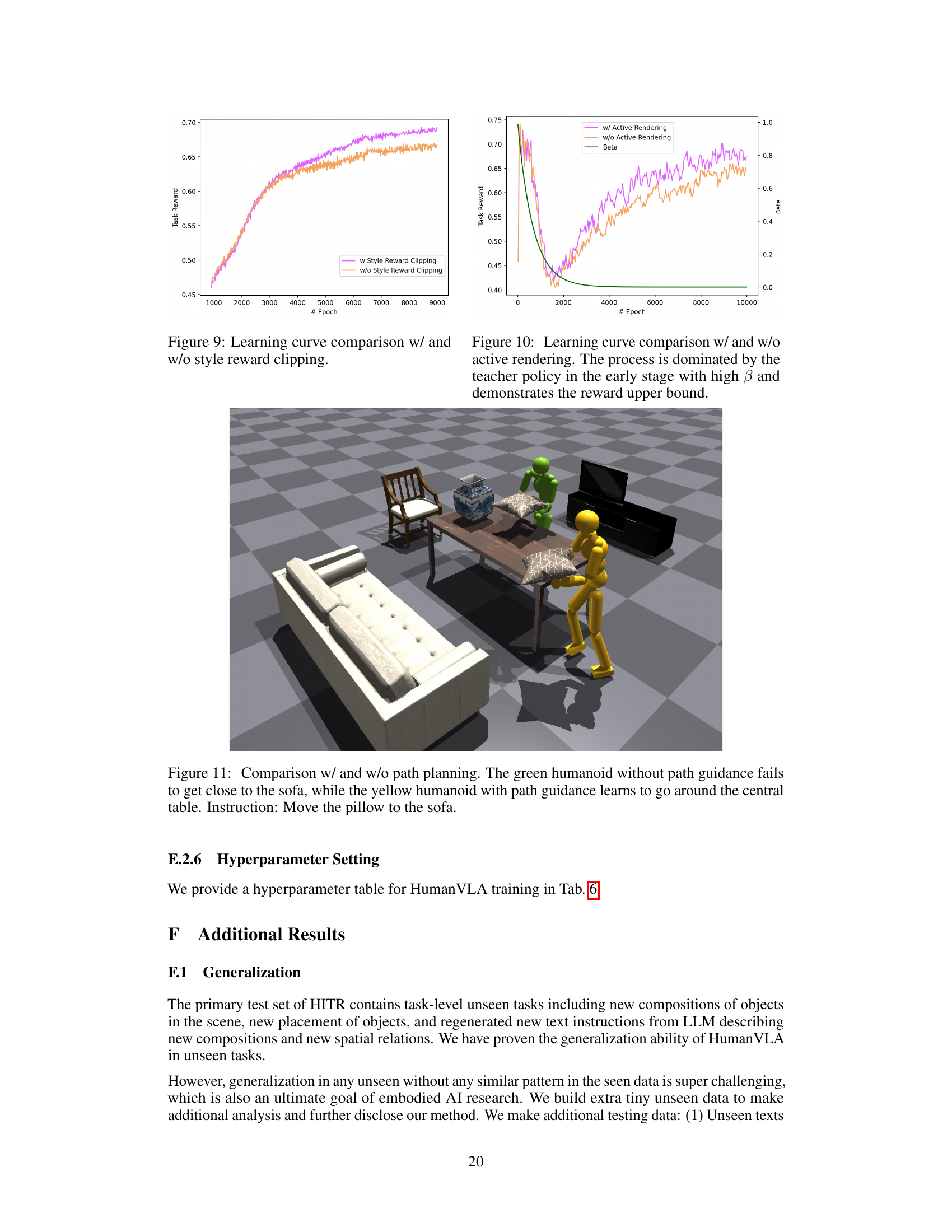

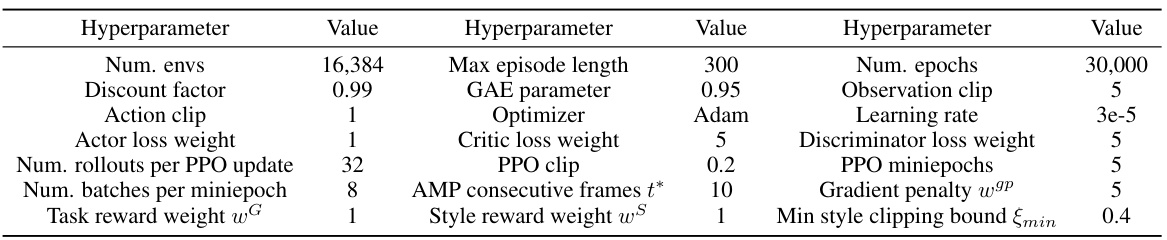

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameters used during the training of the HumanVLA-Teacher model. It includes parameters related to the training environment (number of environments, maximum episode length, etc.), the PPO algorithm (discount factor, learning rate, etc.), and the adversarial motion prior (AMP) method (consecutive frames, style reward weight, etc.). The values listed represent the settings used to achieve the results reported in the paper.

read the caption

Table 5: Hyperparameters for HumanVLA-Teacher training.

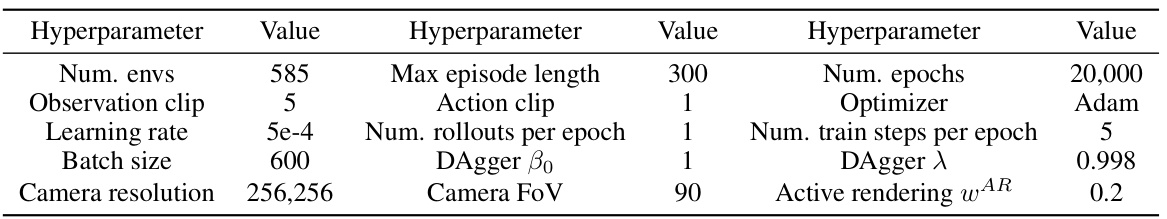

🔼 This table lists the hyperparameters used for training the HumanVLA model. It includes parameters related to the training environment (number of environments, observation and action clipping, camera resolution and field of view), the learning process (learning rate, batch size, number of rollouts and training steps per epoch, optimizer), and the DAgger algorithm (beta naught and lambda). Finally, it specifies the weight used for active rendering.

read the caption

Table 6: Hyperparameters for HumanVLA training.

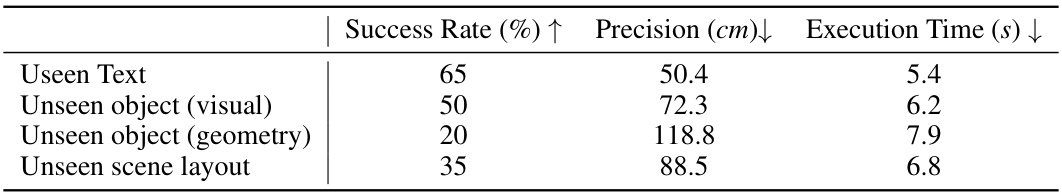

🔼 This table presents the results of an unseen data analysis, evaluating the model’s performance on tasks with unseen texts, unseen object (visual and geometry), and unseen scene layouts. The metrics used are Success Rate (%), Precision (cm), and Execution Time (s). Lower precision and execution time values are better.

read the caption

Table 7: Unseen data analysis.

Full paper#