↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms often struggle with the computational cost associated with large state and action spaces. Transfer RL aims to alleviate this by leveraging knowledge from similar tasks, but effective transfer depends on the similarity between tasks and the ease of transferring representations. Existing methods have limitations in scaling and don’t fully address this challenge.

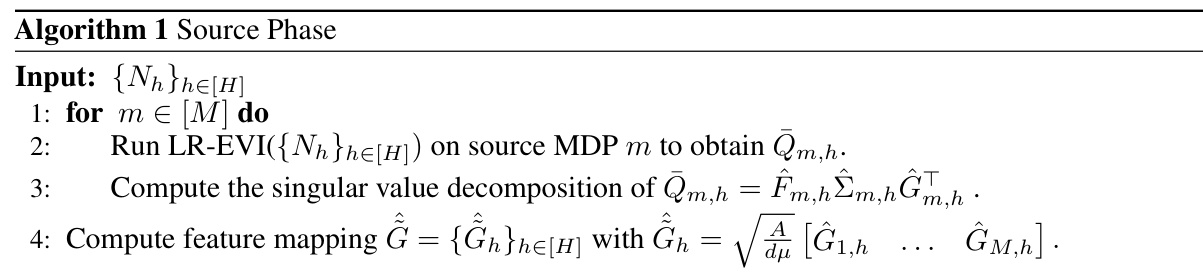

This work proposes new computationally efficient transfer RL algorithms for settings with low-rank structure in the transition kernels. These algorithms learn latent representations from source MDPs and exploit their linear structure to minimize the dependence on state and action space sizes in target MDP regret bounds. The introduction of a “transfer-ability” coefficient quantifies transfer difficulty, and the paper proves that these algorithms are minimax optimal (excluding the (d,d,d) setting) with respect to this coefficient. The efficient algorithms and strong theoretical guarantees make this a significant advance in transfer learning for RL.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in reinforcement learning, especially those dealing with large state and action spaces. It offers novel algorithms and theoretical guarantees that significantly improve the efficiency of transfer learning, reducing computational costs and improving performance. The introduction of the transfer-ability coefficient provides a new way to quantify the difficulty of knowledge transfer, opening up avenues for further research into more robust and effective transfer learning techniques. The results are also relevant to broader fields like multi-task learning and meta-learning.

Visual Insights#

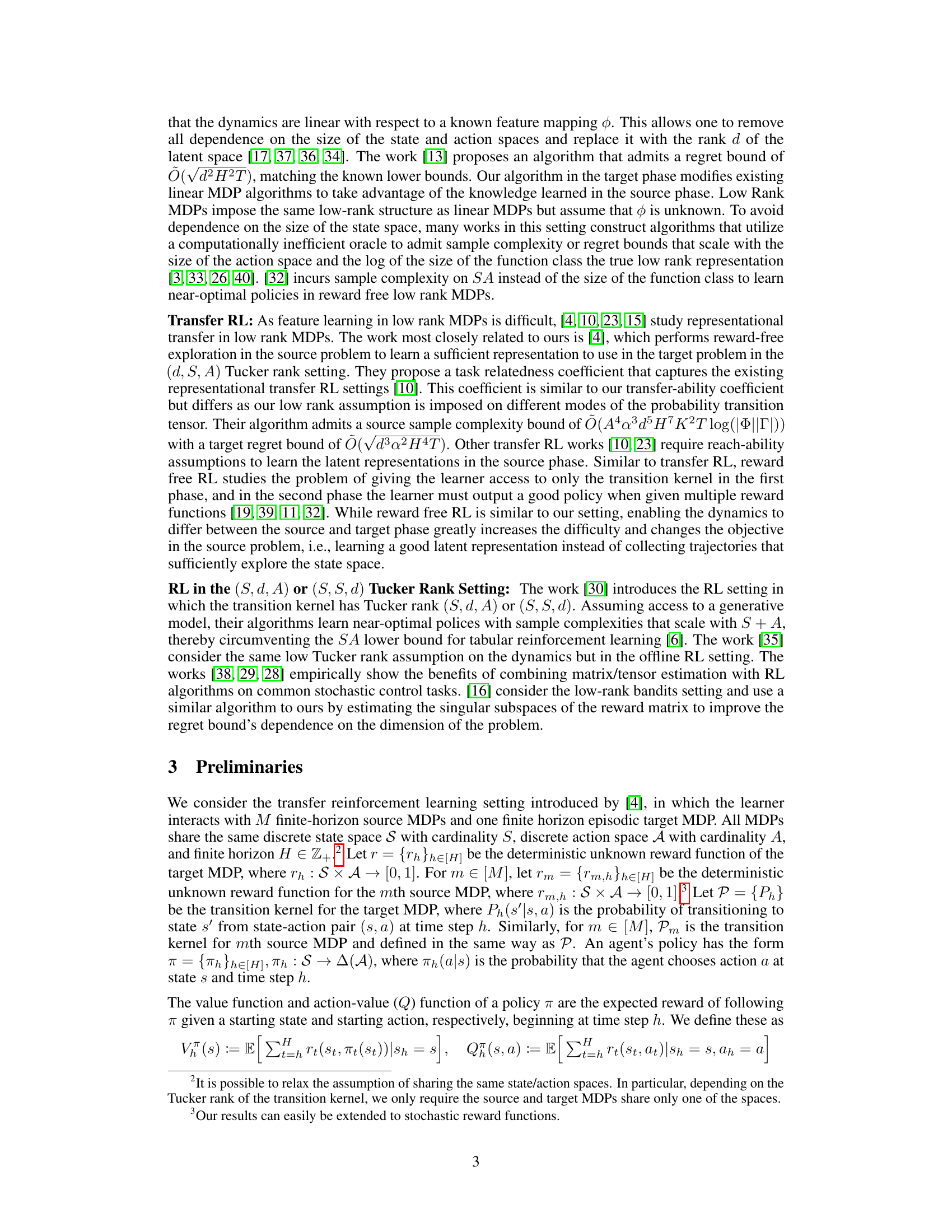

This figure shows a 3D tensor representing the transition kernel Ph(s’|s, a) with Tucker rank (S, S, d). The dimensions represent state (S), action (A), and next state (S’). The core tensor is of size S x S x d, indicating a low-rank structure along the action dimension. The figure visually demonstrates how the transition probabilities are decomposed into a lower-dimensional representation, which is a crucial aspect of the paper’s focus on low-rank structure in reinforcement learning.

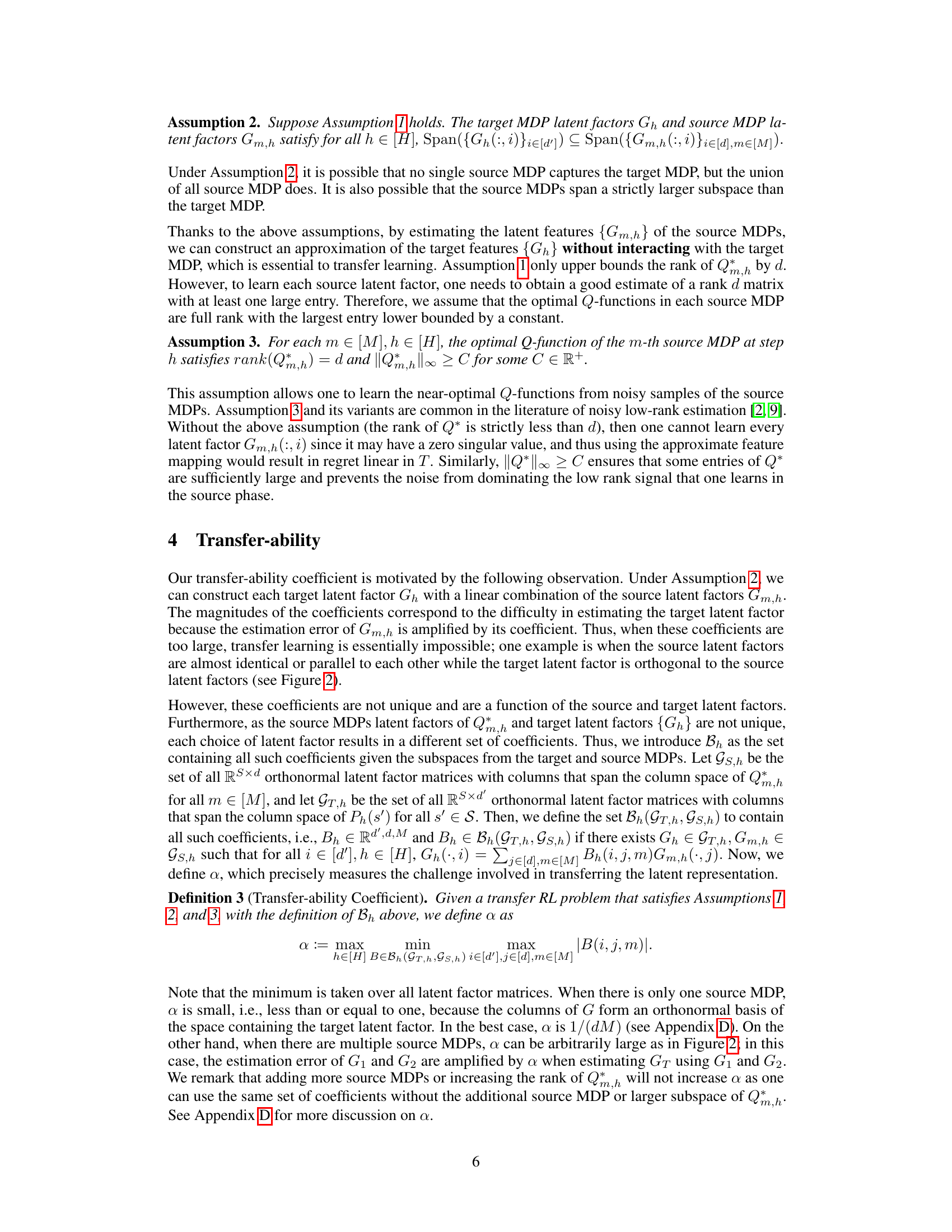

This table presents the theoretical upper bounds on the sample complexity in the source phase and regret in the target phase of different transfer reinforcement learning algorithms. Each algorithm is designed for a specific Tucker rank setting of the Markov Decision Process (MDP), which represents the structure of the transition kernels in the source and target MDPs. The Tucker rank settings considered are (S, S, d), (S, d, A), (d, S, A), and (d, d, d), where S, A are the dimensions of the state and action spaces, and d represents the low rank of the latent structure. The table also shows a comparison with existing results from the literature.

In-depth insights#

Low Rank Transfer RL#

Low-Rank Transfer Reinforcement Learning (RL) tackles the challenge of applying RL in scenarios with high-dimensional state and action spaces by leveraging low-rank structure. The core idea is to learn compact, low-dimensional representations of the environment’s dynamics from a source task, then transfer these representations to improve learning in a related target task. This approach significantly reduces computational cost and data requirements compared to standard RL methods. The efficacy hinges on carefully defining a transferability coefficient that quantifies the similarity between the source and target tasks’ latent representations. This coefficient is crucial for bounding regret and sample complexity, ultimately determining the effectiveness of transfer learning. Algorithms are designed to learn optimal policies in the target task while minimizing the reliance on high-dimensional data. Information-theoretic lower bounds provide further insights into the fundamental limits of low-rank transfer RL. While positive results demonstrate the potential benefits, the algorithms’ optimality often depends on the chosen Tucker rank structure and requires careful consideration of assumptions about incoherence and the transferability coefficient. Future work should focus on refining these assumptions and extending the approach to more complex scenarios.

Transferability Limits#

The heading ‘Transferability Limits’ in a reinforcement learning (RL) context likely explores the boundaries of transferring knowledge between different RL tasks. A core question is how similar two tasks must be for successful transfer. The analysis would likely involve a transferability coefficient or metric quantifying this similarity, showing that transfer performance degrades as this coefficient decreases. Information-theoretic lower bounds might demonstrate the minimal amount of information needed from the source task to achieve a certain performance level in the target task. The research likely investigates various low-rank settings for the source and target Markov Decision Processes (MDPs), revealing how the rank of the transition kernel, and how the choice of low-rank mode influence transferability. The study’s contribution may be identifying minimax-optimal algorithms for different levels of task similarity. Ultimately, this section aims to provide a more precise understanding of when and how transfer learning works effectively, defining limitations and highlighting potential areas for future improvement.

Tucker Rank Analysis#

Tucker rank decomposition is a powerful tool for analyzing multi-dimensional data, particularly in the context of tensors. In the realm of reinforcement learning (RL), this technique is applied to decompose transition probability tensors, revealing latent low-rank structures. This analysis is crucial because it reduces the computational complexity of RL algorithms by focusing on lower-dimensional representations of the state, action, and state-action spaces. The transferability coefficient (α), often introduced alongside Tucker rank analysis, is a key metric representing the similarity between source and target Markov Decision Processes (MDPs). This coefficient helps quantify the effectiveness of knowledge transfer between tasks and is essential for assessing the potential success of transfer reinforcement learning. The lower bound on the source sample complexity, frequently derived through Tucker rank analysis, highlights the necessary sample size to effectively leverage transfer learning. Lower bounds demonstrate the inherent difficulty in transferring representations and achieving optimal performance with limited data. Ultimately, Tucker rank analysis provides a framework for understanding the underlying structure of RL problems and improves the efficiency of algorithms through dimensionality reduction.

Minimax Regret Bounds#

Minimax regret bounds represent a crucial concept in the analysis of online decision-making problems. They provide a rigorous measure of the performance of an algorithm in the worst-case scenario, comparing it to an optimal strategy that has perfect knowledge of the future. In the context of reinforcement learning, minimax regret bounds aim to characterize the algorithm’s cumulative regret, the difference between the reward accumulated by the algorithm and that of an optimal policy, over a certain time horizon. The minimax framework considers the worst-case performance over all possible sequences of events and rewards. Establishing minimax bounds is important because it guarantees a certain level of performance irrespective of the problem’s specifics, providing a strong theoretical justification for an algorithm’s effectiveness. The tightness of these bounds often reflects the algorithm’s sophistication and its ability to adapt to unforeseen circumstances. A lower bound reveals the intrinsic difficulty of a given problem, suggesting that no algorithm can perform better than a certain threshold. Conversely, an upper bound indicates that an algorithm exists which is guaranteed to stay within a particular regret range, providing a benchmark for algorithm development. Achieving matching upper and lower bounds establishes the optimality of an algorithm in the minimax sense.

Future Work#

The “Future Work” section of a research paper on transfer reinforcement learning with latent low-rank structure could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical analysis to more complex settings such as partially observable MDPs (POMDPs) or continuous state and action spaces would significantly broaden the applicability of the findings. Developing more robust and efficient algorithms that are less sensitive to hyperparameter choices and initializations is crucial for real-world applications. Investigating alternative low-rank tensor decompositions beyond the Tucker decomposition could potentially improve performance and scalability. Empirical evaluations on a wider range of benchmark tasks and real-world problems are needed to validate the theoretical claims and assess the practical advantages of the proposed methods. Finally, exploring connections to other areas of machine learning, such as meta-learning and few-shot learning, could reveal novel insights and lead to more powerful transfer learning techniques.

More visual insights#

More on tables

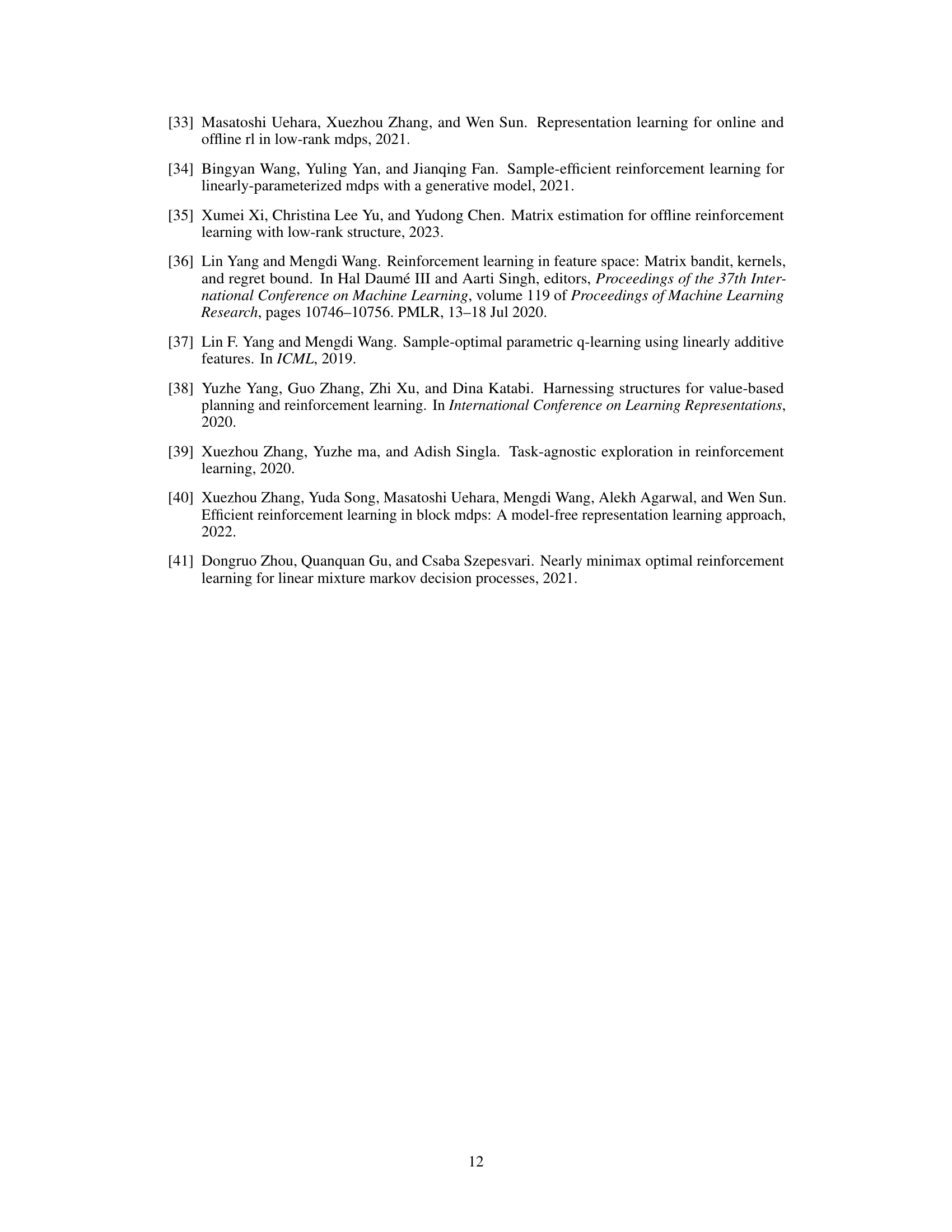

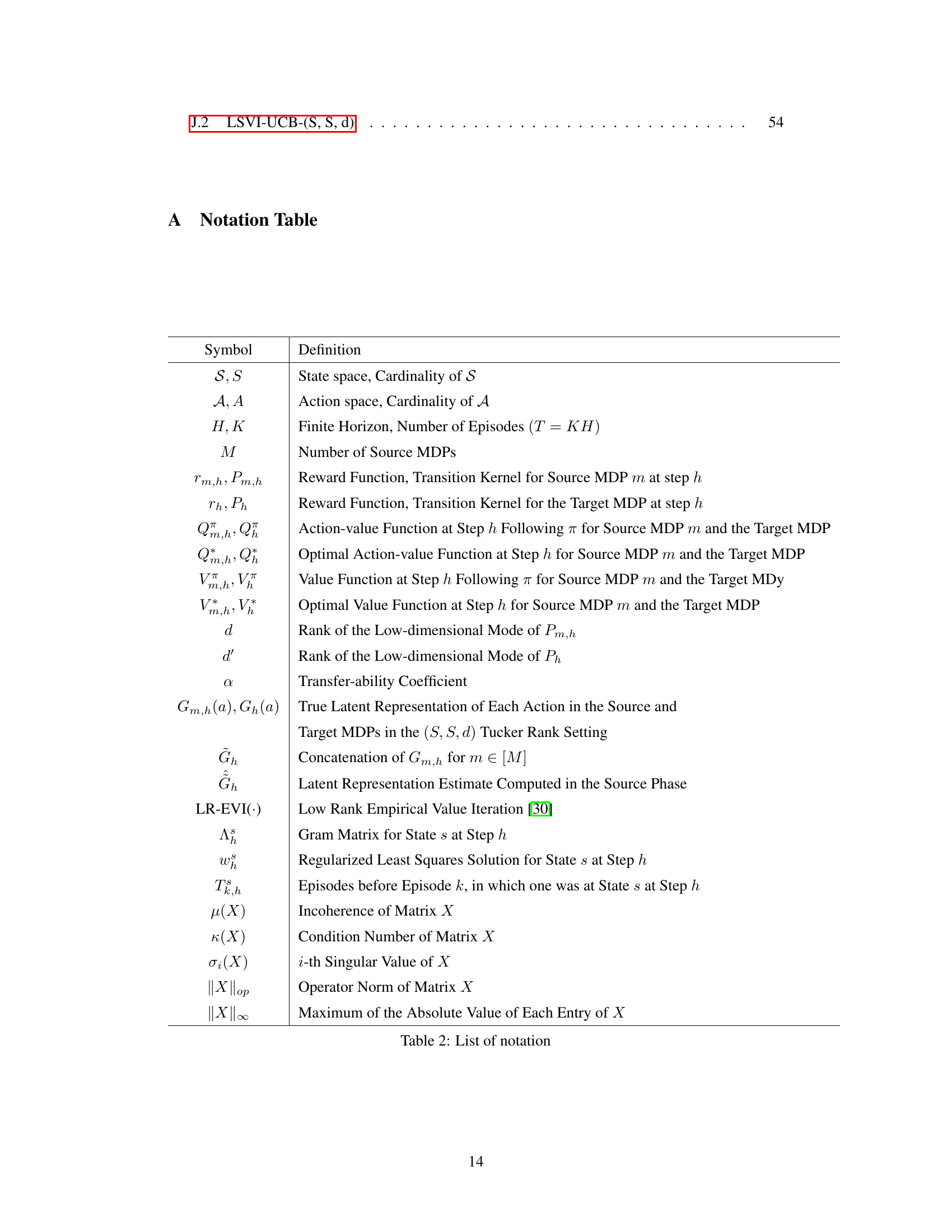

This table presents the theoretical upper bounds on the source sample complexity and target regret for transfer reinforcement learning algorithms under four different Tucker rank settings: (S, S, d), (S, d, A), (d, S, A), and (d, d, d). Each row represents a Tucker rank setting and provides the complexity and regret bounds achieved by the proposed algorithm in the paper, along with comparisons to existing results from the literature. The transfer-ability coefficient ‘a’ is a key factor influencing these bounds, reflecting the difficulty of transferring knowledge between source and target MDPs. The table highlights the algorithm’s ability to achieve regret bounds that are independent of the state space (S) and/or action space (A) size in several settings, showcasing the effectiveness of leveraging low-rank structure for efficient transfer learning.

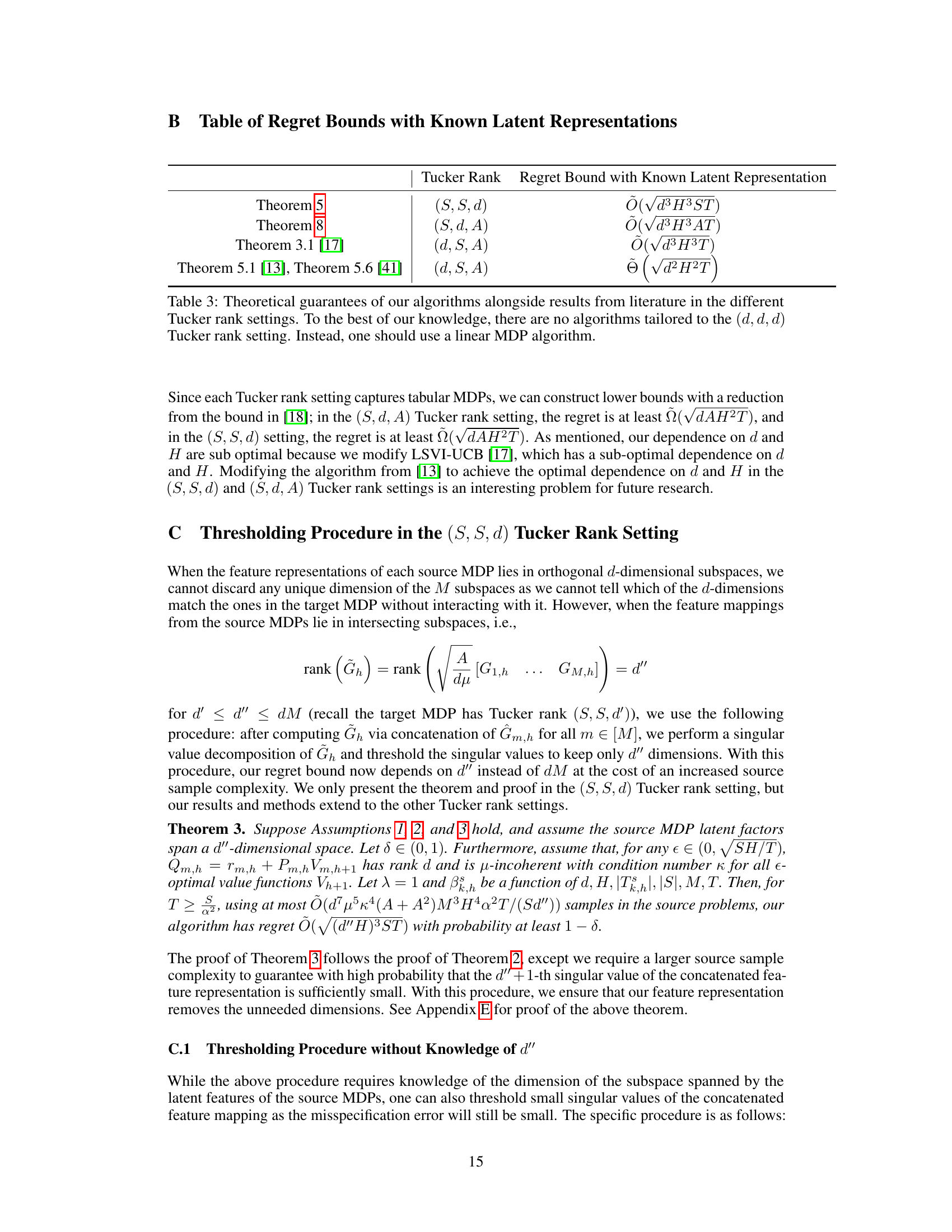

This table summarizes the theoretical guarantees of the proposed transfer reinforcement learning algorithms across different Tucker rank settings ((S, S, d), (S, d, A), (d, S, A), and (d, d, d)). It compares the source sample complexity (the number of samples needed from source MDPs) and the target regret bound (the difference between the reward collected by the learner and the reward of an optimal policy in the target MDP) achieved by the proposed algorithms with existing results from the literature. The table highlights how the algorithms’ performance scales with various parameters such as the Tucker rank (d), the horizon (H), the number of episodes (T), the transfer-ability coefficient (a) which represents the difficulty of transferring the latent representation, and other common matrix estimation terms. Note that Table 3 in the paper provides additional results for the case where latent representations are known.

This table summarizes the theoretical upper bounds on the regret achieved by the proposed algorithms in the paper, compared to existing algorithms from the literature. The table shows regret bounds for four different Tucker rank settings of the transition kernel: (S, S, d), (S, d, A), (d, S, A), and (d, d, d). Each setting represents a different low-rank structure assumption on the relationship between the state, action, and next state in the Markov Decision Process (MDP). The regret bound indicates the difference in cumulative reward between the optimal policy and the policy learned by the algorithm. The table also highlights the source sample complexity, representing the amount of data needed from source MDPs for effective transfer learning. Note that Table 3 in the paper provides additional regret bounds under the assumption that the latent representation of the MDP is already known.

Full paper#