TL;DR#

This research investigates the source of algorithmic capabilities in transformer models, questioning whether these arise solely from training or also exist in the model’s initial state. Existing work has shown that transformers can perform complex tasks, but it is unclear whether these capabilities are learned during training or are inherent to the model’s architecture and initialization. This study also highlights the limitations of existing interpretability techniques, which often focus on analyzing the model’s parameters rather than its input/output behavior.

The study uses a novel approach by training only the embedding and unembedding layers of randomly initialized transformers on various tasks. The results demonstrate that even before training, these models can achieve impressive performance on tasks involving modular arithmetic, associative recall, and sequence generation. These findings suggest that some algorithmic capabilities are already present in the model and that training merely selects or enhances these pre-existing capabilities. This work challenges prevailing assumptions about the learning process in transformer models and opens new avenues for research into model interpretability and efficient training methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it challenges the common assumption that the capabilities of transformer models are solely due to training. It reveals that inherent algorithmic capabilities exist within randomly initialized transformers, opening exciting new avenues for research into model architecture, interpretability, and efficient training methods. This finding has significant implications for the design, optimization, and understanding of future transformer-based models and their applications.

Visual Insights#

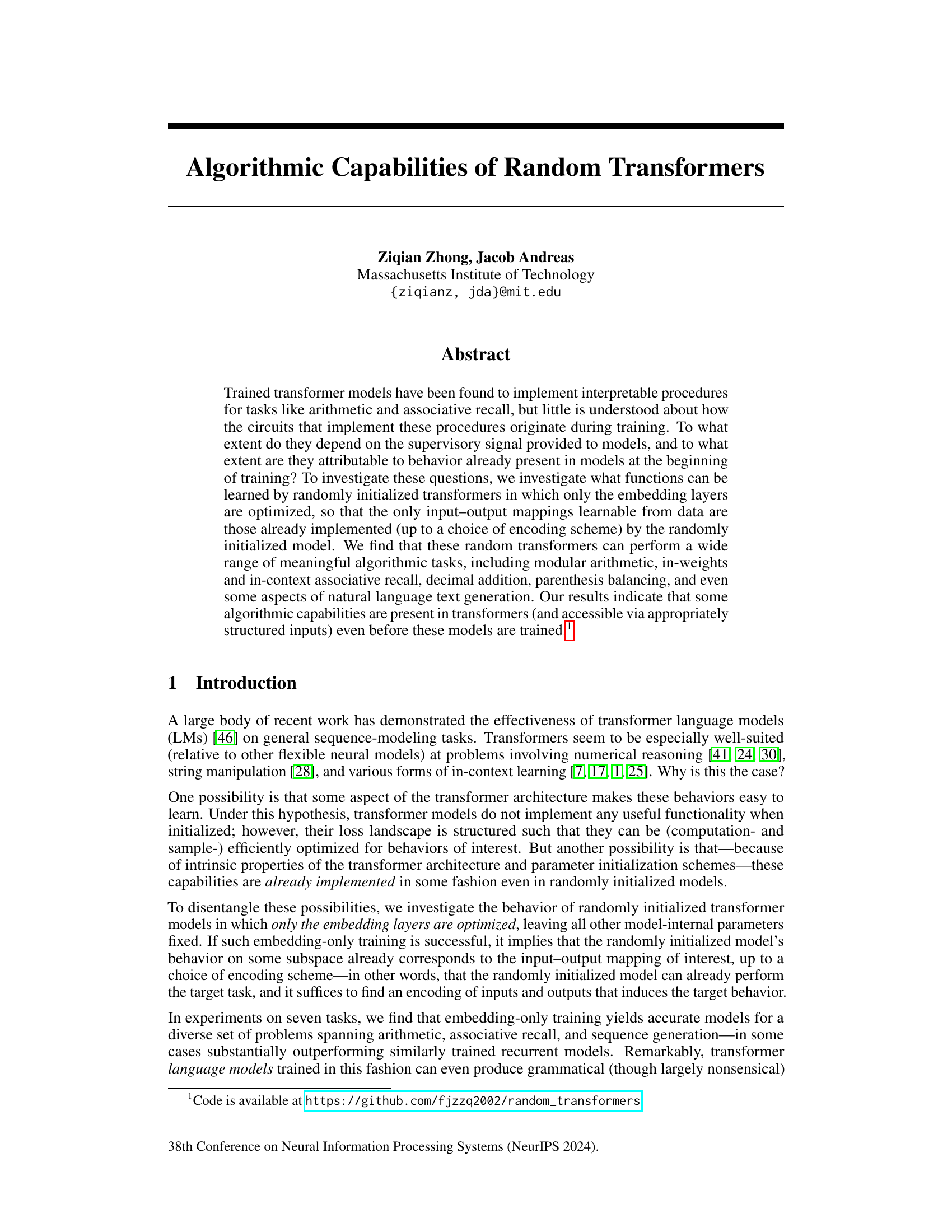

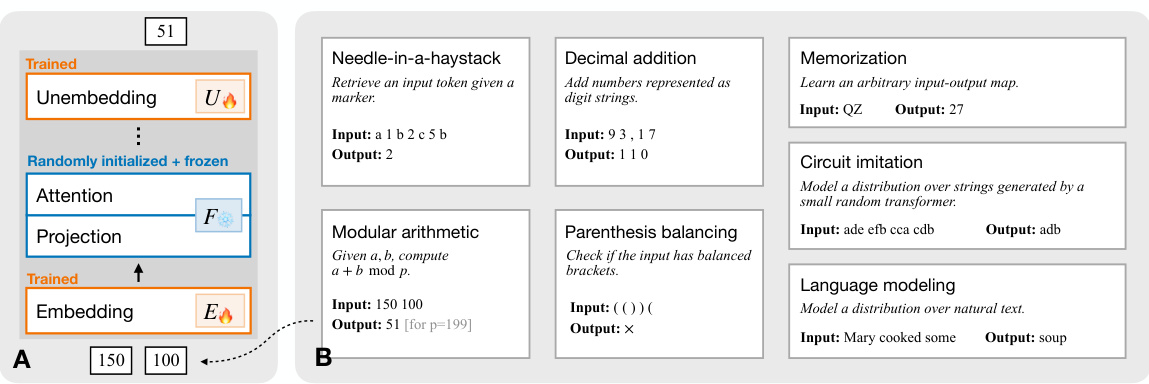

🔼 This figure provides a high-level overview of the experimental setup and the tasks used to evaluate the capabilities of randomly initialized transformers. Part A illustrates the modeling approach, where a randomly initialized transformer is fine-tuned by only training the embedding and unembedding layers while leaving the internal layers frozen. Part B outlines the seven tasks used to assess the performance of these models. These tasks encompass various domains, including arithmetic (modular arithmetic, decimal addition), memory-based tasks (needle-in-a-haystack, memorization), and sequence processing (parenthesis balancing, circuit imitation, language modeling).

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of problem setup. A: Modeling approach. We initialize transformers randomly, then optimize only their input and output embedding layers on a dataset of interest. We find that these random transformers can be successfully trained to perform a diverse set of human-meaningful tasks. B: Task set. We evaluate the effectiveness of random transformers on a set of model problems involving arithmetic and memorization, as well as modeling of natural language text.

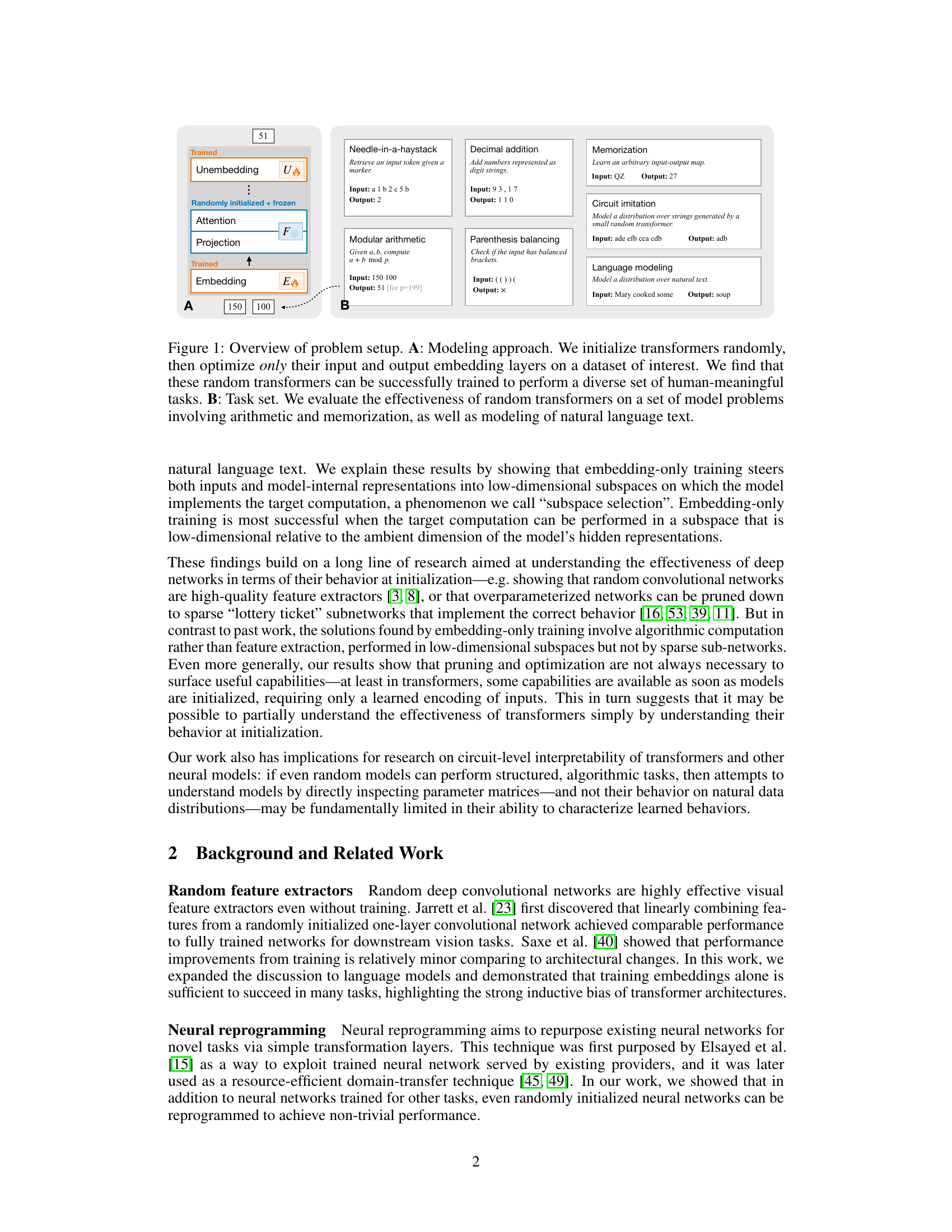

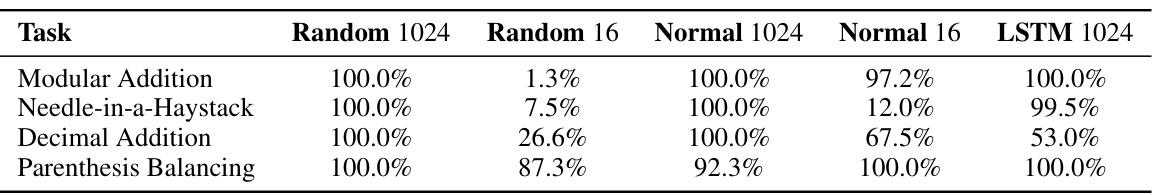

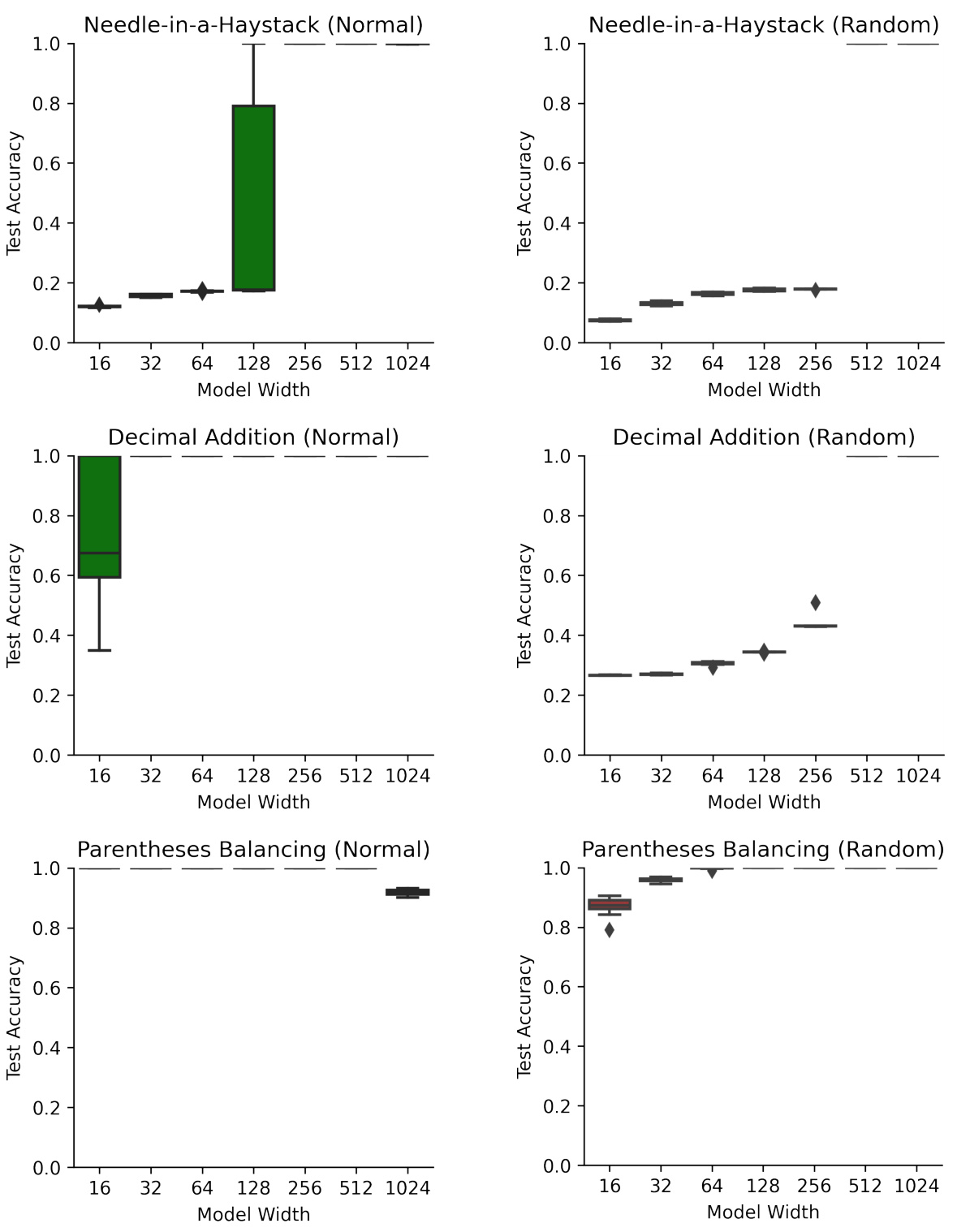

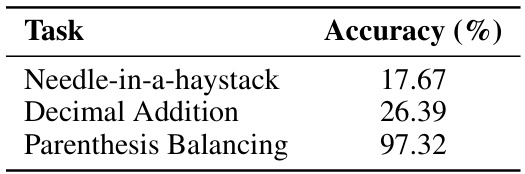

🔼 This table compares the performance of fully trained and randomly initialized transformers (with only embedding layers trained) on four algorithmic tasks: modular addition, needle-in-a-haystack, decimal addition, and parenthesis balancing. It shows that even randomly initialized transformers can achieve high accuracy, sometimes exceeding that of fully trained LSTMs, when only the embedding layers are trained.

read the caption

Table 1: Test accuracy of fully trained and random transformers, as well as fully trained LSTMs, on algorithmic tasks. Denoted numbers (1024 and 16) are hidden sizes; results are median over 10 random restarts. Random models with only trained embeddings reliably perform all four tasks, and even outperform fully trained LSTMs. See Appendix E for the accuracy curve on multiple hidden sizes.

In-depth insights#

Random Transformer Power#

The concept of “Random Transformer Power” invites exploration into the surprising capabilities of transformer models initialized with random weights. Research suggests that these models, even before training, possess an inherent capacity for various algorithmic tasks. This challenges the common assumption that transformers’ power stems solely from learned parameters, revealing a significant inductive bias within the architecture itself. Embedding-only training, a technique where only the input/output embeddings are optimized, demonstrates this pre-existing potential. It shows that some tasks can be solved by simply finding appropriate encodings to leverage the already-present functionality in the random initialization. This indicates that the effective dimensionality of the model’s computations is significantly lower than the model’s full parameter space; the model operates within a lower-dimensional subspace. While fully trained models outperform random transformers, the latter still display remarkable capabilities, especially in specific domains. The success of embedding-only training highlights the crucial role of input representation in unlocking algorithmic power in randomly initialized transformers. Further investigation into this phenomenon could lead to more efficient training methods and a deeper understanding of the fundamental strengths of transformer architectures.

Embedding-Only Training#

Embedding-only training, a novel approach in the study, involves training only the input and output embedding layers of a randomly initialized transformer model while keeping the internal layers frozen. This technique allows the researchers to investigate the extent to which a transformer’s algorithmic capabilities are inherent in its architecture and initial parameters, independent of the learning process. The results reveal that random transformers with embedding-only training can surprisingly perform a variety of algorithmic tasks, including modular arithmetic and associative recall. This finding suggests that some algorithmic abilities might be intrinsically present in the model’s architecture even before training, challenging the prevailing assumption that all functionality is solely learned during training. This method is particularly significant because it helps to disentangle the contributions of the architecture itself from the effects of learned weights, offering valuable insights into the fundamental nature of transformer models and their capacity for computation.

Algorithmic Capabilities#

The study explores the algorithmic capabilities present in randomly initialized transformer models. It challenges the assumption that these capabilities solely emerge from training data by demonstrating that a wide array of algorithmic tasks, including arithmetic, associative recall, and even aspects of natural language processing, can be performed by models where only embedding layers are optimized. This suggests that transformers possess inherent architectural biases or properties conducive to algorithmic computation, even before any training. Subspace selection, a phenomenon where the model operates within low-dimensional subspaces of its high-dimensional parameter space, is proposed as a potential mechanism explaining this behavior. The findings highlight the importance of studying the intrinsic properties of neural network architectures and suggest that interpretability efforts should not solely focus on trained models, but should also consider the capabilities of randomly initialized models.

Subspace Selection#

The concept of “Subspace Selection” in the context of randomly initialized transformers is a crucial finding. It suggests that the successful training of these models, even with only embedding layers optimized, is due to the inherent presence of algorithmic capabilities within low-dimensional subspaces of the model’s parameter space. This implies that the initial random parameterization already contains solutions to specific tasks, and training effectively guides the model towards these pre-existing solutions by selecting the appropriate subspace. This contrasts with the idea that all algorithmic functionality is purely learned during training. The low-dimensionality of these effective subspaces also provides insights into the efficiency of random transformers, suggesting that significant computational complexity isn’t needed. The authors’ observation that this phenomenon is more pronounced in language modeling suggests a potential connection between the model’s ability to learn and the dimensionality of its internal representations. The study of this subspace selection mechanism opens avenues for more efficient model design and provides a new perspective on the role of initialization in deep learning models. This phenomenon is further validated by a controlled experiment on circuit imitation, where the random models struggle to effectively imitate high-dimensional circuits, suggesting a direct relationship between model capacity and subspace dimensionality.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on random transformers are multifaceted. Investigating the generalizability of embedding-only training across diverse architectures beyond the transformer model is crucial. Understanding how the observed low-dimensional subspaces relate to the inherent capabilities of various architectures, and whether similar algorithmic capacity emerges in other models, would be insightful. Further exploration into the relationship between model size, training data, and the dimensionality of these functional subspaces is needed. This includes examining the limitations encountered when attempting to utilize this approach for increasingly complex problems, and how increased model capacity might mitigate those limitations. Analyzing how different initialization strategies impact the emergence and characteristics of these low-dimensional subspaces is a critical next step. This could unlock methods for strategically leveraging these emergent capabilities from initialization and potentially accelerating convergence during training. Finally, the practical implications of embedding-only training for resource-constrained settings and efficient model deployment must be explored. Combining this approach with model compression techniques might yield highly compact yet effective models for resource-limited environments.

More visual insights#

More on figures

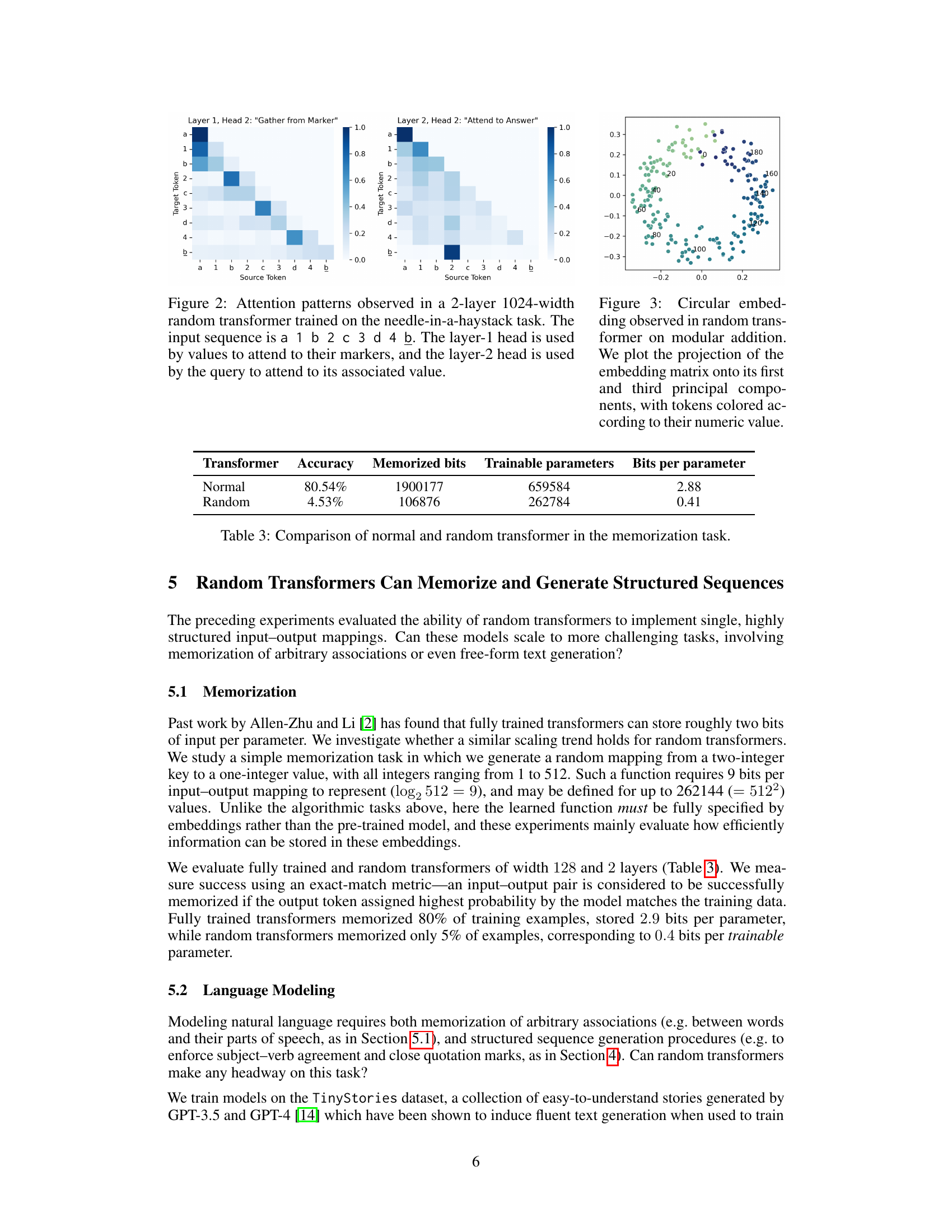

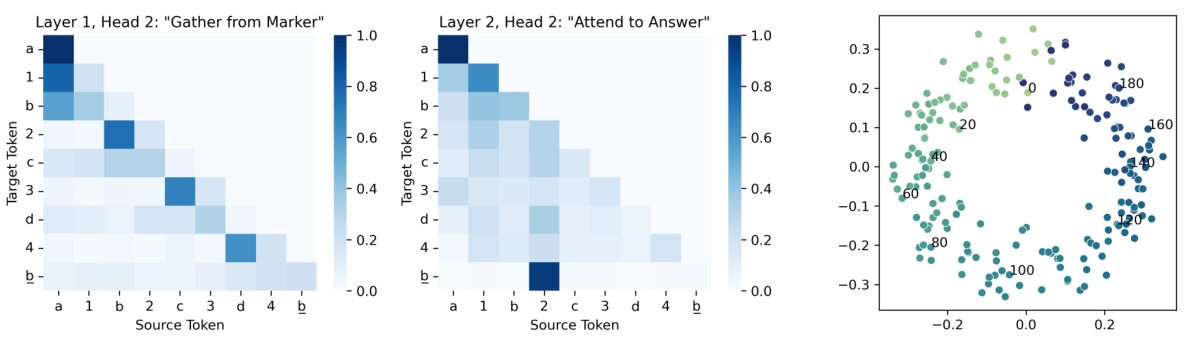

🔼 This figure shows the attention patterns in a randomly initialized transformer trained on a ’needle-in-a-haystack’ task. The task involves finding a specific value associated with a marker in a sequence. The figure demonstrates that the model uses different attention heads for different parts of the task. Layer 1, Head 2, is used to identify the marker-value pairs. While, Layer 2, Head 2, helps the model retrieve the target value based on the query.

read the caption

Figure 2: Attention patterns observed in a 2-layer 1024-width random transformer trained on the needle-in-a-haystack task. The input sequence is a 1 b 2 c 3 d 4 b. The layer-1 head is used by values to attend to their markers, and the layer-2 head is used by the query to attend to its associated value.

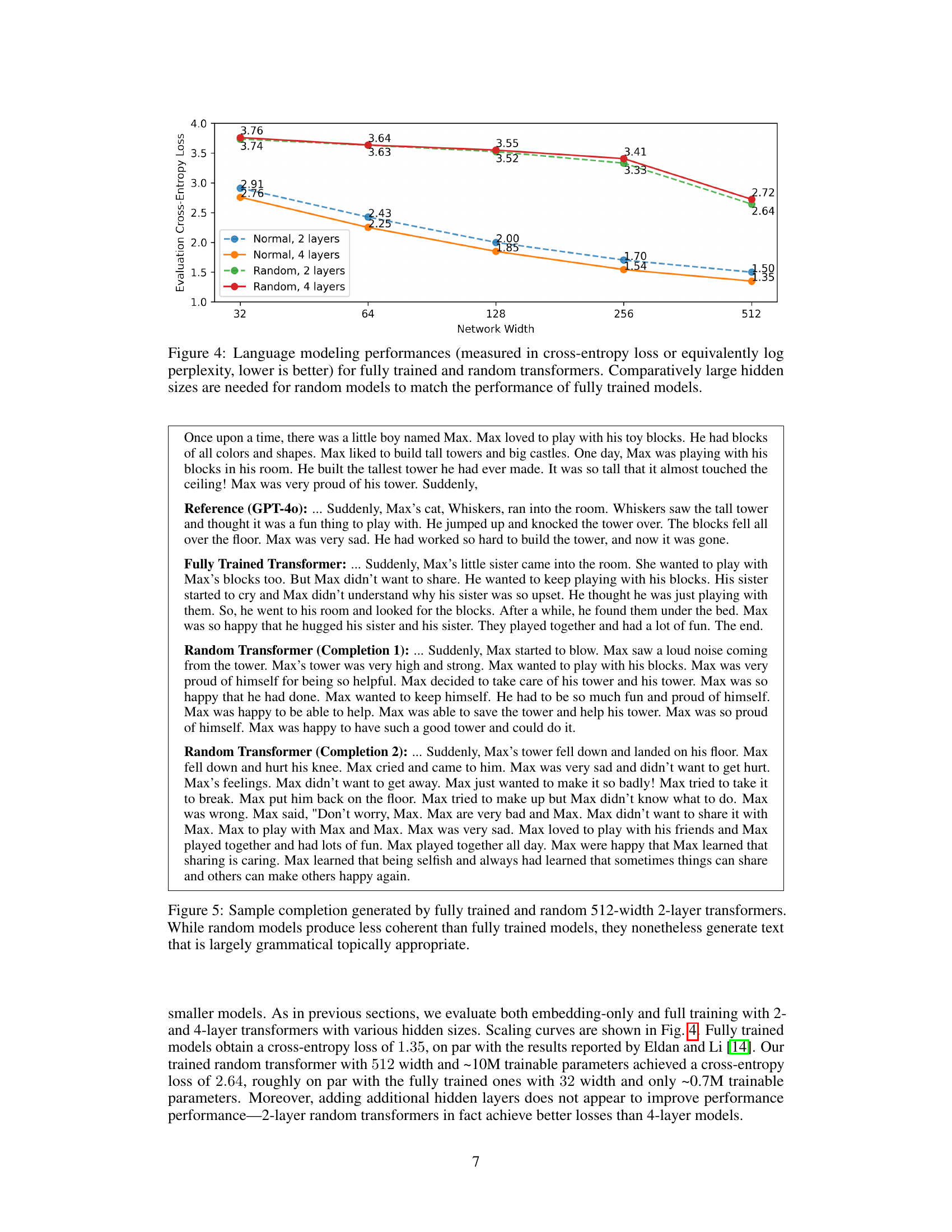

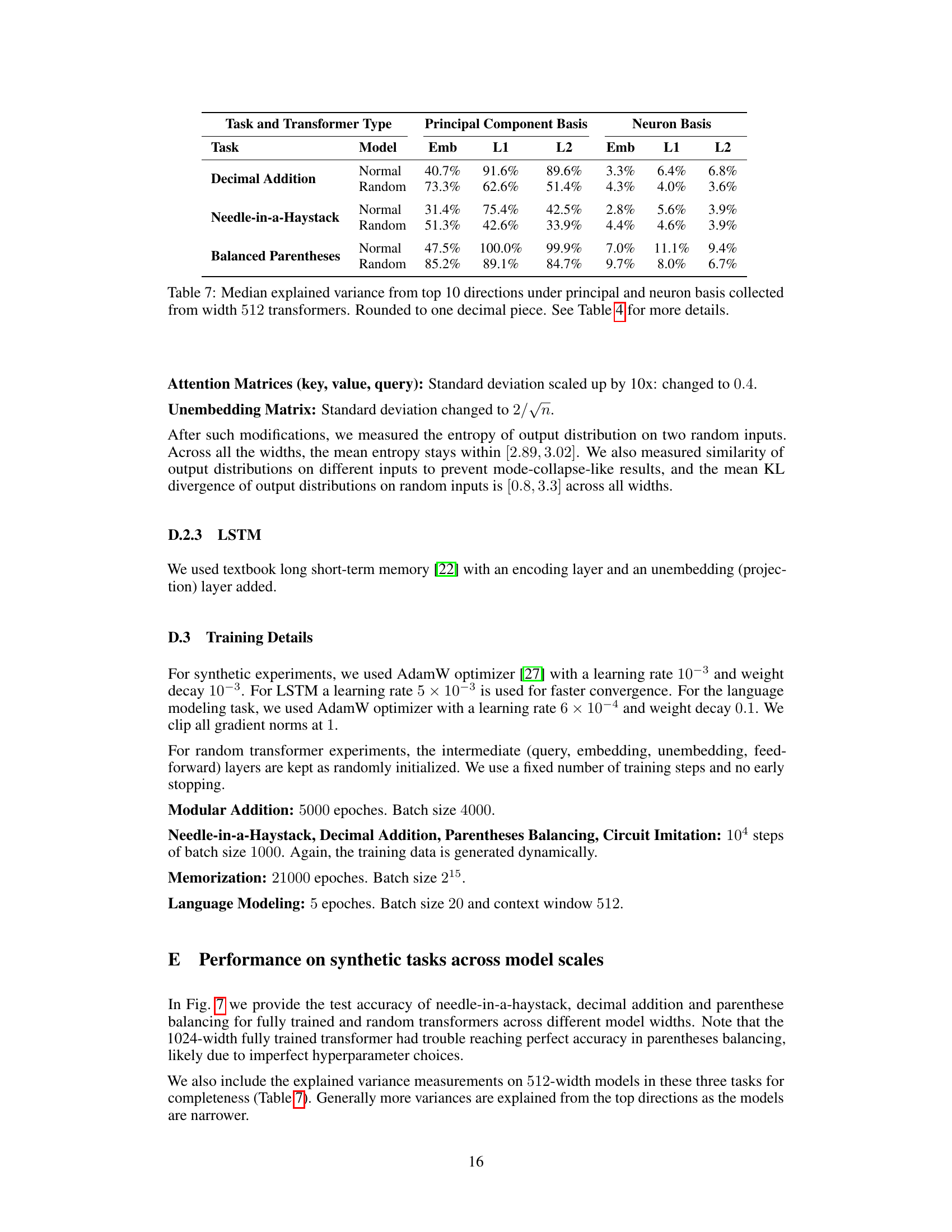

🔼 This figure shows the cross-entropy loss for language modeling achieved by both fully trained and randomly initialized transformers. The x-axis represents the network width, while the y-axis represents the cross-entropy loss (lower is better). Different lines represent different model architectures (2-layer vs. 4-layer, normal vs. random). The results indicate that randomly initialized models require significantly larger network widths to achieve comparable performance to fully trained models.

read the caption

Figure 4: Language modeling performances (measured in cross-entropy loss or equivalently log perplexity, lower is better) for fully trained and random transformers. Comparatively large hidden sizes are needed for random models to match the performance of fully trained models.

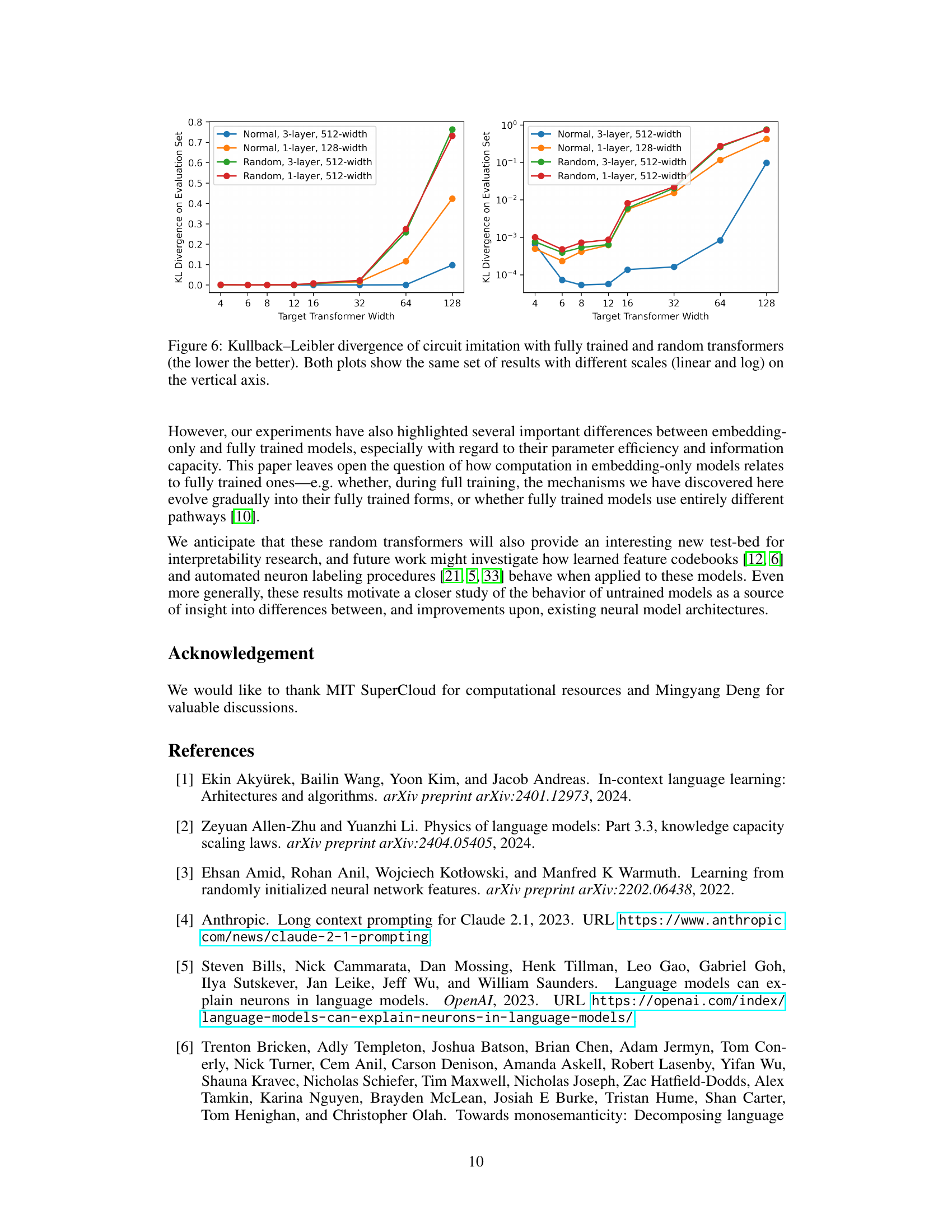

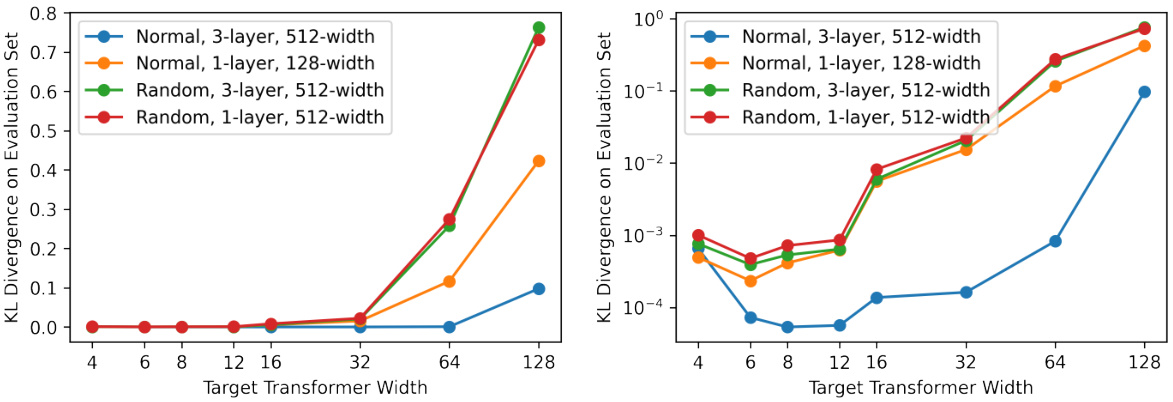

🔼 This figure shows the results of a circuit imitation experiment comparing fully trained and randomly initialized transformers. The x-axis represents the width of the target transformer (the model being imitated), while the y-axis represents the Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence between the target transformer’s output distribution and the output distribution of the imitating transformer. Lower KL divergence indicates better imitation. The figure includes two plots with different y-axis scales (linear and logarithmic) to better visualize the results across different target transformer widths. The results suggest that randomly initialized transformers struggle to effectively imitate wider target transformers.

read the caption

Figure 6: Kullback-Leibler divergence of circuit imitation with fully trained and random transformers (the lower is better). Both plots show the same set of results with different scales (linear and log) on the vertical axis.

🔼 This figure shows the attention patterns in a 2-layer, 1024-width random transformer trained to solve the needle-in-a-haystack task. The input sequence is [a, 1, b, 2, c, 3, d, 4, b], where a, b, c, d are markers and 1, 2, 3, 4 are the associated values. The figure demonstrates how the attention mechanism works in two layers. Layer 1 shows that the values attend to their corresponding markers. Layer 2 displays the query attending to the correct value given its marker.

read the caption

Figure 2: Attention patterns observed in a 2-layer 1024-width random transformer trained on the needle-in-a-haystack task. The input sequence is a 1 b 2 c 3 d 4 b. The layer-1 head is used by values to attend to their markers, and the layer-2 head is used by the query to attend to its associated value.

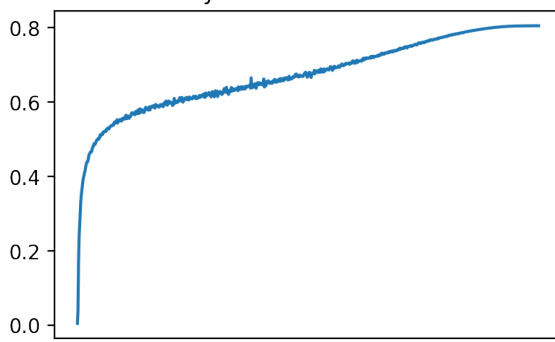

🔼 This figure shows two accuracy curves during the training of fully trained and random transformers on a memorization task. The x-axis represents the training step, and the y-axis shows the accuracy. The random transformer shows a slower but steady increase in accuracy, eventually reaching a similar level to the fully trained transformer. The evaluation set is identical to the training set in this specific experiment.

read the caption

Figure 8: During training, the accuracy curve from fully trained and random transformers in the memorization task (Section 5.1). Note that the evaluation set is exactly the training set as the goal is to memorize.

🔼 This figure shows the accuracy curves for both fully trained and randomly initialized transformers during the memorization task. The x-axis likely represents training steps or epochs, and the y-axis represents the accuracy achieved on the task. Since the evaluation set is identical to the training set in this memorization task, the goal is to perfectly memorize all input-output pairs in the training data.

read the caption

Figure 8: During training, the accuracy curve from fully trained and random transformers in the memorization task (Section 5.1). Note that the evaluation set is exactly the training set as the goal is to memorize.

More on tables

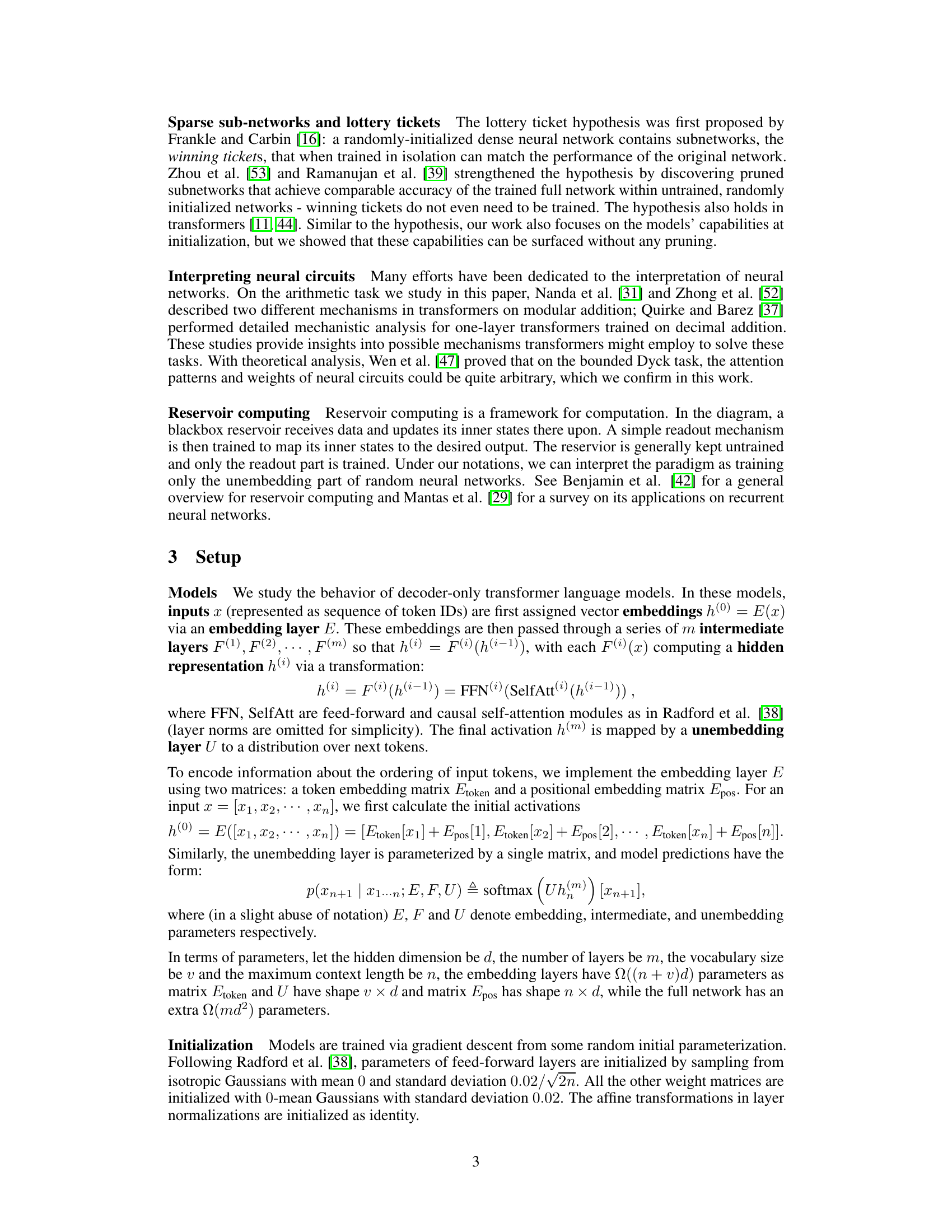

🔼 This table shows the results of an experiment where different parts of a randomly initialized transformer model were trained while keeping other parts frozen. The goal was to determine which parts of the model were essential for successful completion of several algorithmic tasks. The table compares the performance (accuracy) when only the unembedding layer was trained, only the embedding layer was trained, and when only the token and unembedding layers were trained. The results indicate that all three embedding layers must be trained for the model to reliably perform all the tasks.

read the caption

Table 2: Accuracy of embedding-only training with additional parameters fixed: optimizing only the unembedding layer, only the embedding layer, or only non-positional embeddings. Hidden sizes are all 1024; results are median over 10 random restarts. All three embedding matrices must be optimized for models to reliably complete all tasks.

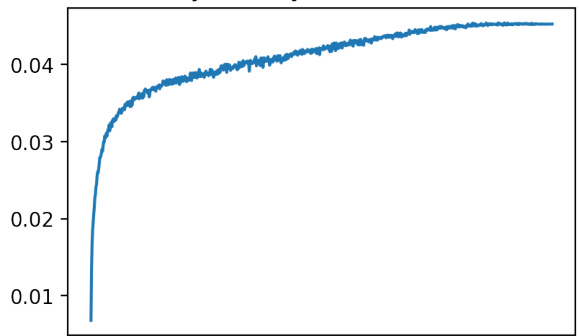

🔼 This table compares the performance of normal (fully trained) and random transformers on a memorization task. It shows the accuracy achieved, the number of bits memorized, the number of trainable parameters, and the bits per parameter for each type of transformer. The results highlight the difference in efficiency between the two approaches.

read the caption

Table 3: Comparison of normal and random transformer in the memorization task.

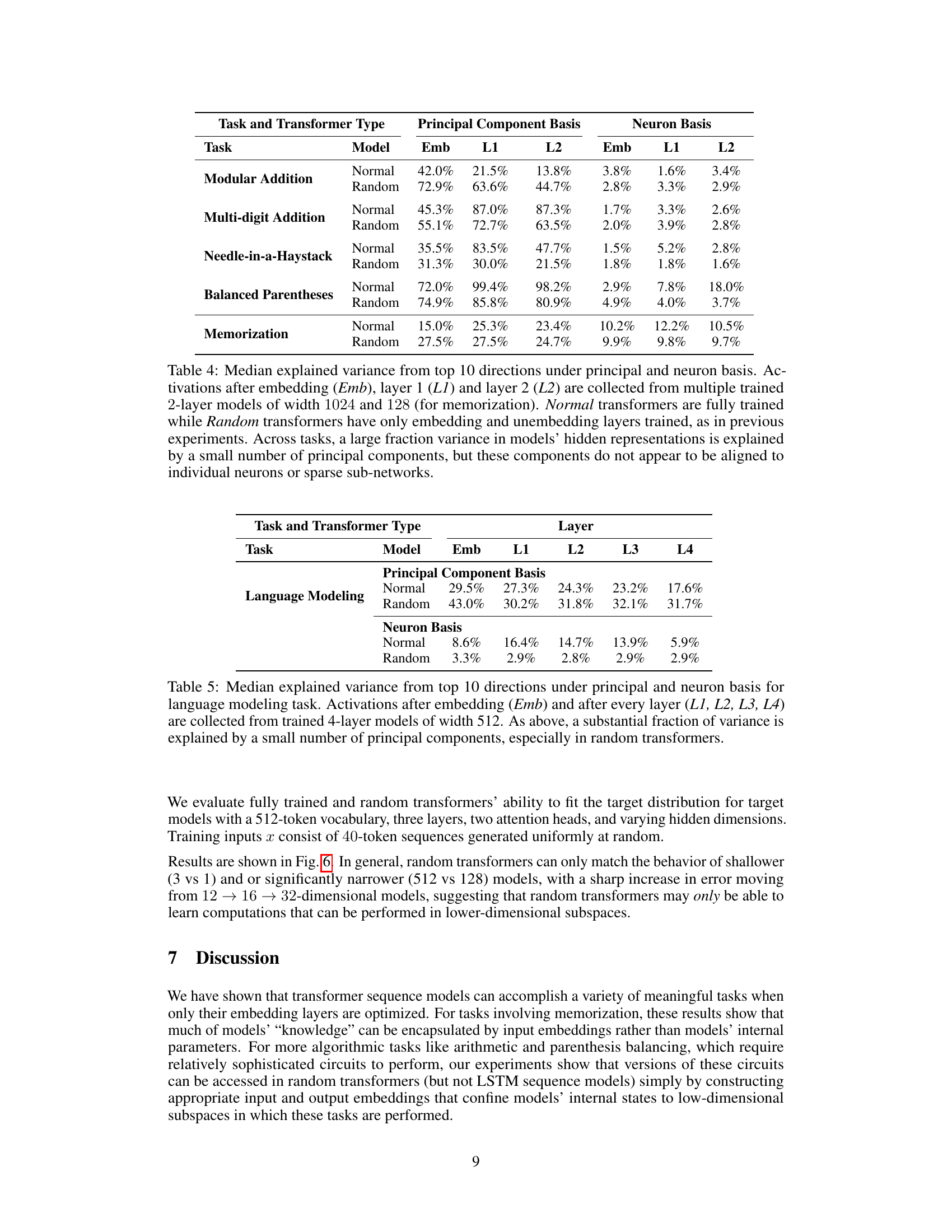

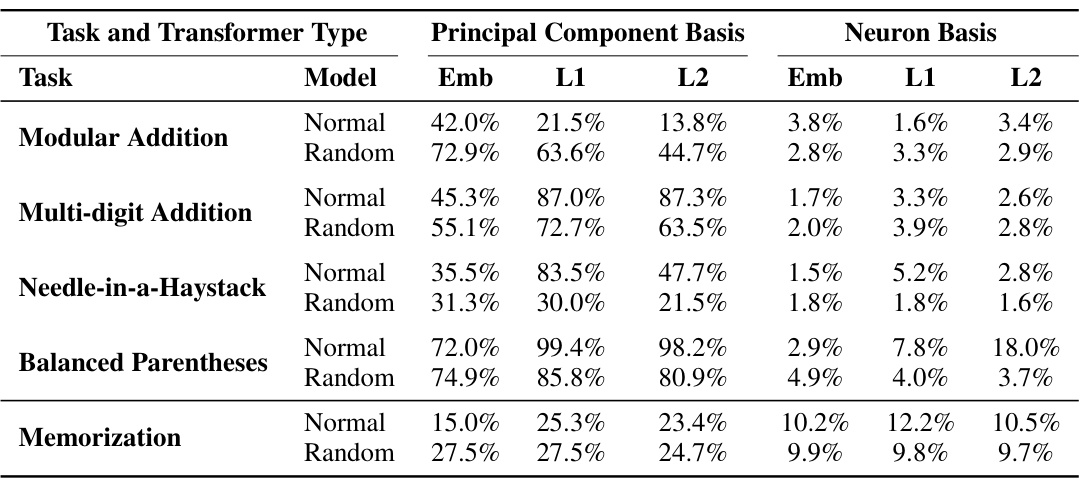

🔼 This table shows the median explained variance from the top 10 principal components and neuron basis for various tasks. It compares the explained variance in fully trained vs. randomly initialized transformers, looking at activations at different layers (embedding, layer 1, and layer 2). The results demonstrate that, across tasks, a substantial portion of the variance is explained by a small number of principal components, regardless of training method. However, these components are not aligned with individual neurons or sparse subnetworks.

read the caption

Table 4: Median explained variance from top 10 directions under principal and neuron basis. Activations after embedding (Emb), layer 1 (L1) and layer 2 (L2) are collected from multiple trained 2-layer models of width 1024 and 128 (for memorization). Normal transformers are fully trained while Random transformers have only embedding and unembedding layers trained, as in previous experiments. Across tasks, a large fraction variance in models' hidden representations is explained by a small number of principal components, but these components do not appear to be aligned to individual neurons or sparse sub-networks.

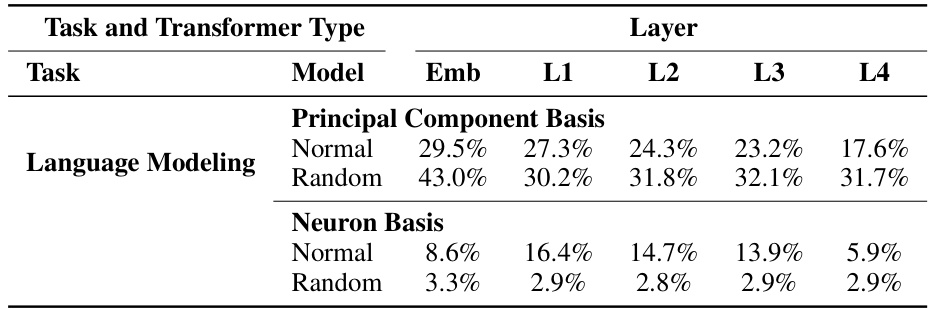

🔼 This table shows the median explained variance from the top 10 principal components and neuron basis for the language modeling task. It compares the results from fully trained and random transformers (with only embedding layers trained) at different layers (embedding, layer 1-4). It demonstrates the extent to which the hidden representations of these models are concentrated in low-dimensional subspaces.

read the caption

Table 5: Median explained variance from top 10 directions under principal and neuron basis for language modeling task. Activations after embedding (Emb) and after every layer (L1, L2, L3, L4) are collected from trained 4-layer models of width 512. As above, a substantial fraction of variance is explained by a small number of principal components, especially in random transformers.

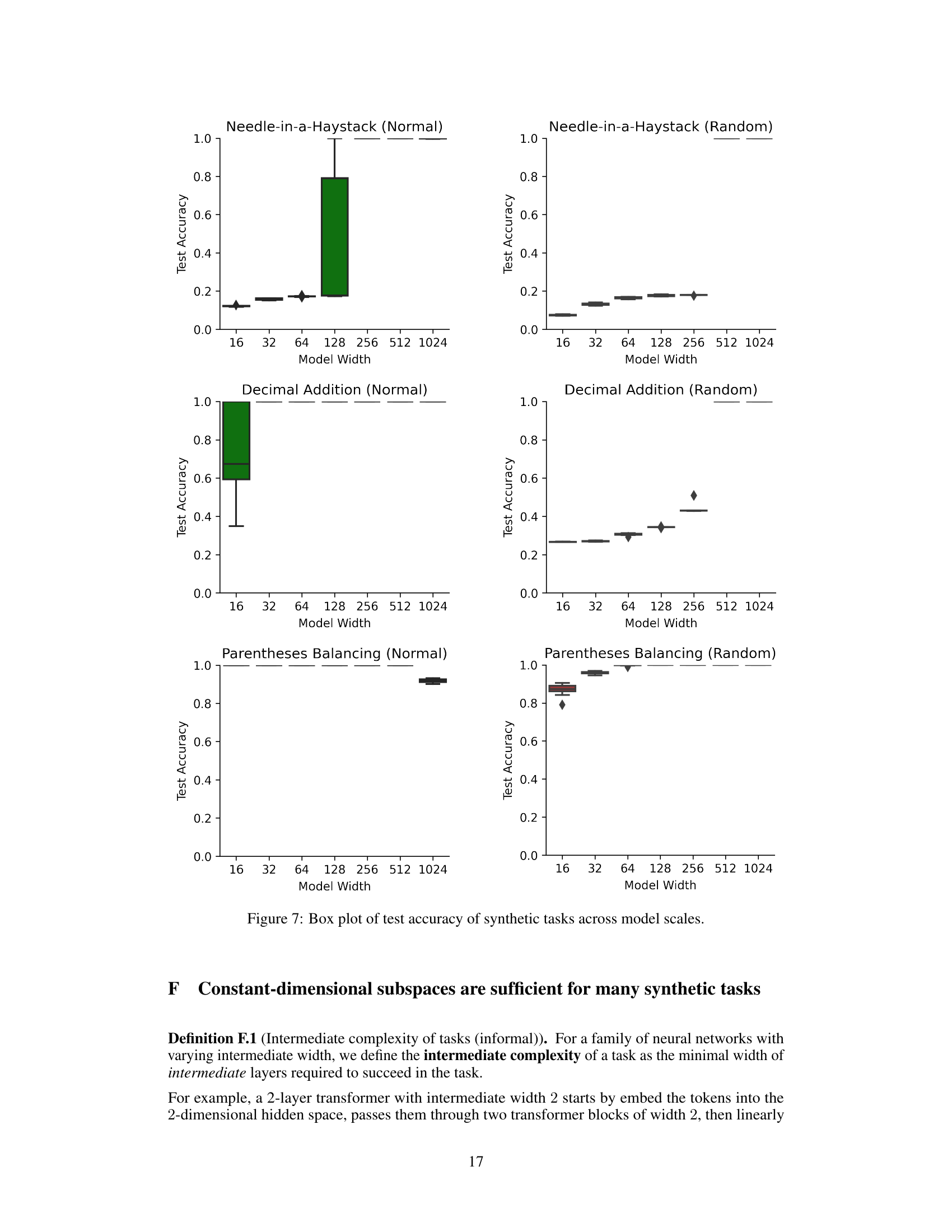

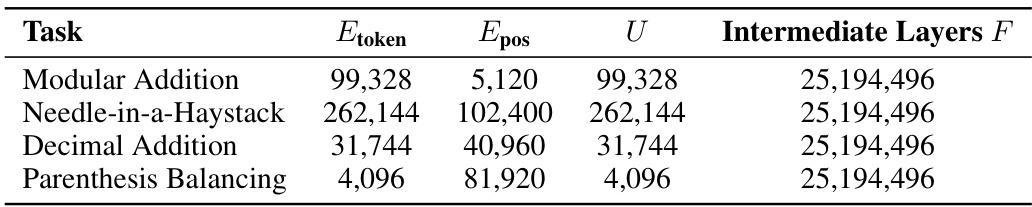

🔼 This table shows the number of parameters for each component of the 2-layer, 1024-width transformer models used in section 4 of the paper. The components are: token embeddings (Etoken), positional embeddings (Epos), unembedding layer (U), and intermediate layers (F). The table provides a breakdown of the parameter counts for each of these components across four different algorithmic tasks: modular addition, needle-in-a-haystack, decimal addition, and parenthesis balancing.

read the caption

Table 6: Number of parameters of each type for the 2-layer 1024-width transformers in Section 4.

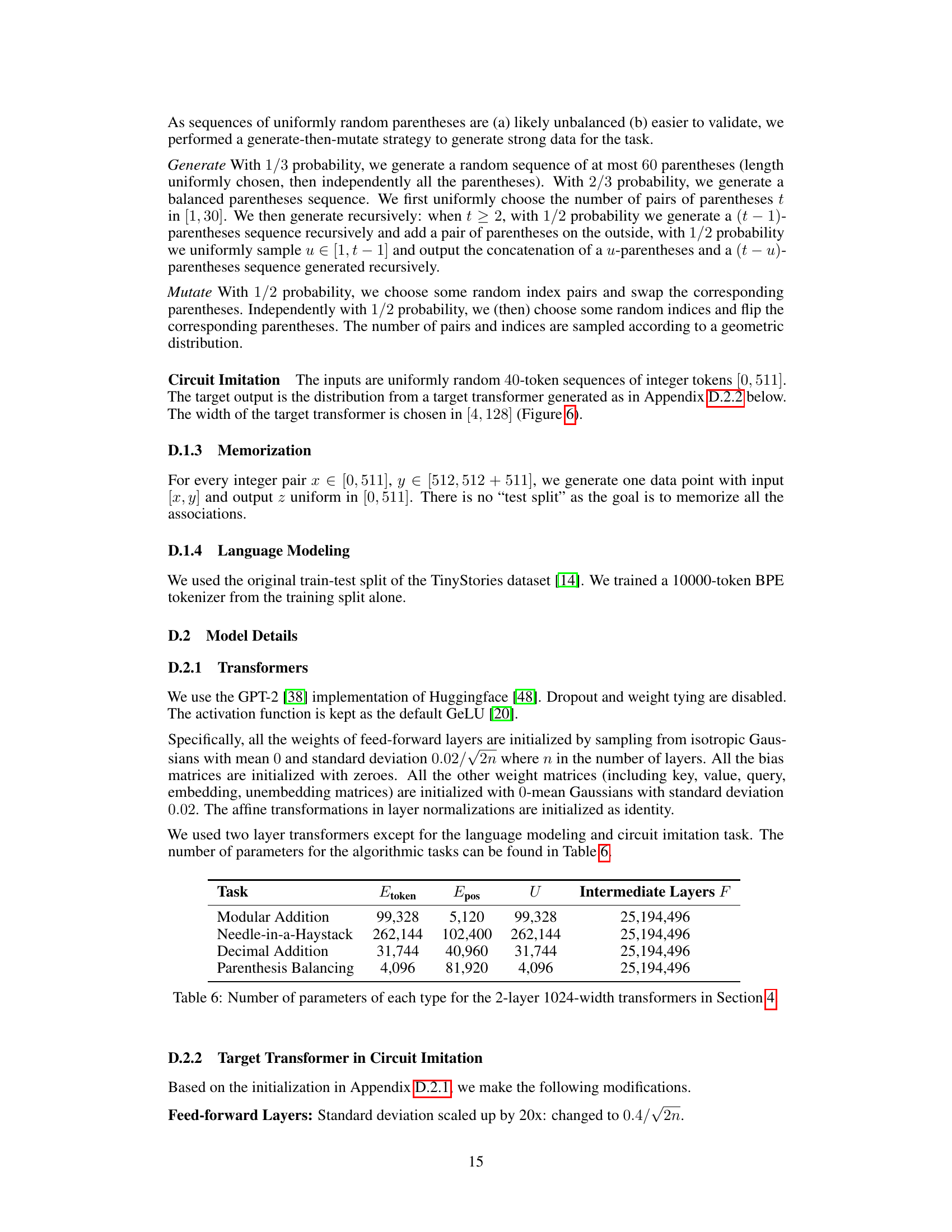

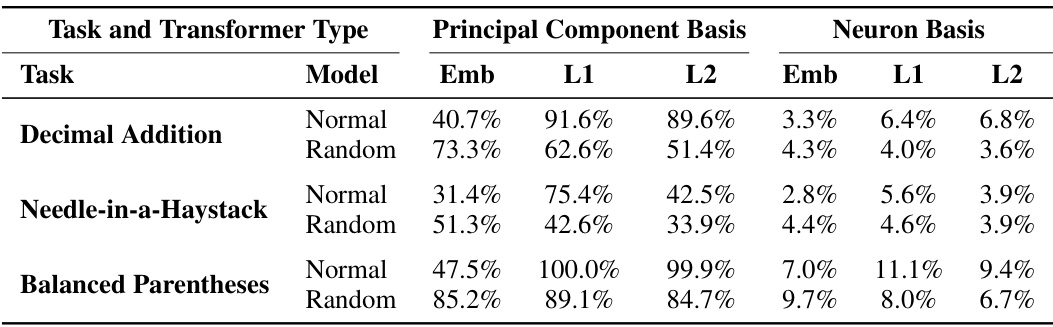

🔼 This table shows the median explained variance from the top 10 principal components and neuron basis for three tasks: Decimal Addition, Needle-in-a-Haystack, and Balanced Parentheses. It compares the explained variance in the embedding layer (Emb), layer 1 (L1), and layer 2 (L2) for both fully trained (‘Normal’) and randomly initialized transformer models (‘Random’). The data illustrates the extent to which the models’ hidden representations are concentrated in low-dimensional subspaces for each task and model type. Values are rounded to one decimal place, and more detailed results can be found in Table 4.

read the caption

Table 7: Median explained variance from top 10 directions under principal and neuron basis collected from width 512 transformers. Rounded to one decimal piece. See Table 4 for more details.

🔼 This table shows the accuracy of three different model types (fully trained transformer, random transformer, and fully trained LSTM) on four algorithmic tasks. The table compares models with different hidden sizes (16 and 1024), and results are the median accuracy across 10 runs with different random initializations. It highlights that randomly initialized transformers, with only embedding layers trained, can achieve high accuracy on these tasks, sometimes even surpassing fully trained models.

read the caption

Table 1: Test accuracy of fully trained and random transformers, as well as fully trained LSTMs, on algorithmic tasks. Denoted numbers (1024 and 16) are hidden sizes; results are median over 10 random restarts. Random models with only trained embeddings reliably perform all four tasks, and even outperform fully trained LSTMs. See Appendix E for the accuracy curve on multiple hidden sizes.

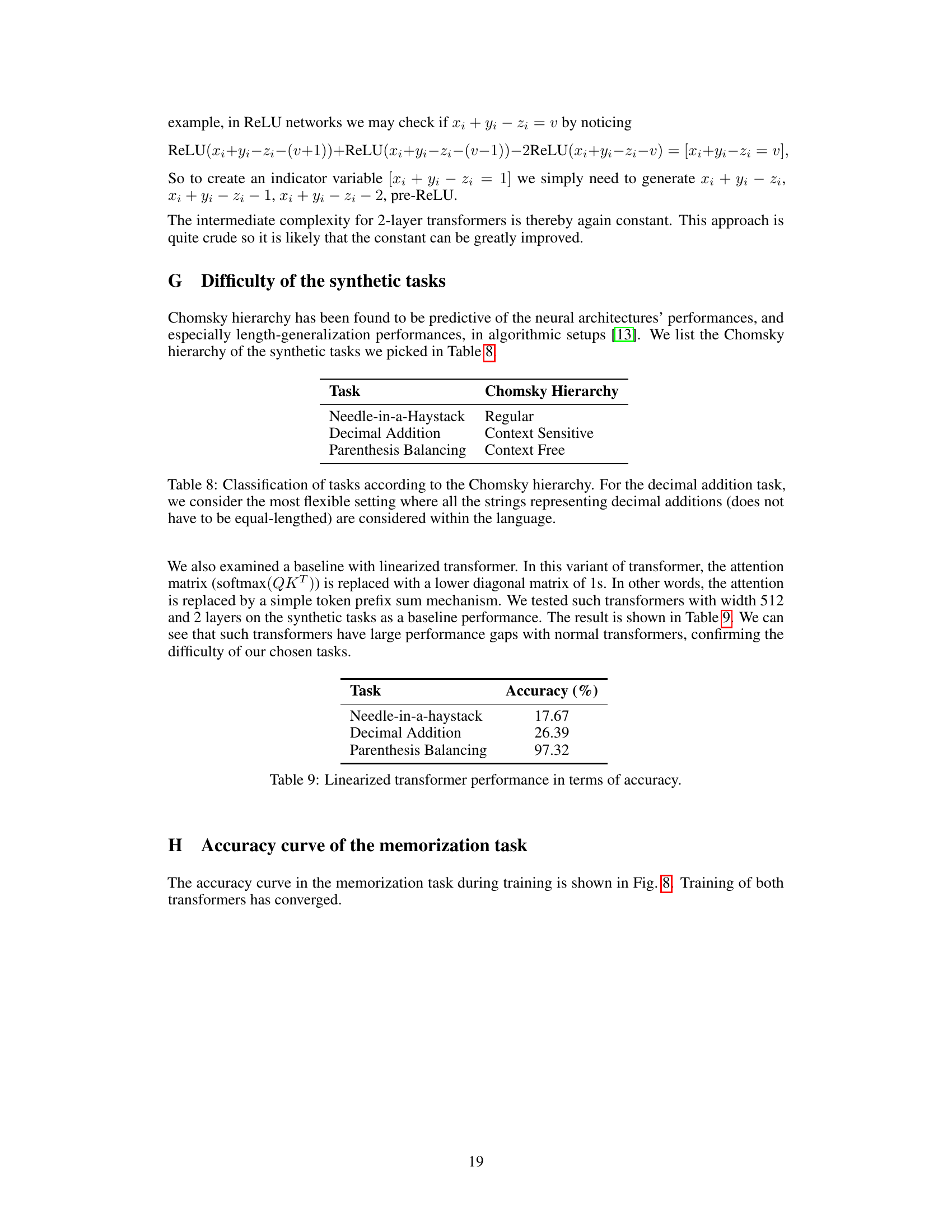

🔼 This table shows the accuracy achieved by linearized transformers (transformers with attention replaced by a simple token prefix sum mechanism) on three different algorithmic tasks: Needle-in-a-haystack, Decimal Addition, and Parenthesis Balancing. The results highlight the significant performance gap between linearized transformers and standard transformers on these tasks, which demonstrates the difficulty of the tasks.

read the caption

Table 9: Linearized transformer performance in terms of accuracy.

Full paper#