↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current Code Large Language Models (Code LLMs) struggle with understanding deeper code semantics beyond syntax, hindering their performance in complex tasks like debugging. This limitation arises from their primary reliance on static code text data, neglecting the dynamic execution aspects crucial for true comprehension.

To overcome this, the researchers introduce SEMCODER, a novel Code LLM trained with a unique “monologue reasoning” technique. This approach involves training the model to reason about code semantics comprehensively—from high-level functional descriptions to detailed execution behaviors, effectively bridging the gap between static code and dynamic execution states. The results show SEMCODER achieves state-of-the-art performance on various code understanding benchmarks, surpassing even GPT-3.5-turbo in several key areas, particularly execution reasoning. Furthermore, SEMCODER showcases promising debugging and self-refinement capabilities.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on code language models because it introduces a novel approach to enhance their semantic understanding, leading to significant improvements in code generation, execution reasoning, and debugging capabilities. This directly addresses a major limitation of current Code LLMs and opens exciting new avenues for research in program comprehension and automated software engineering.

Visual Insights#

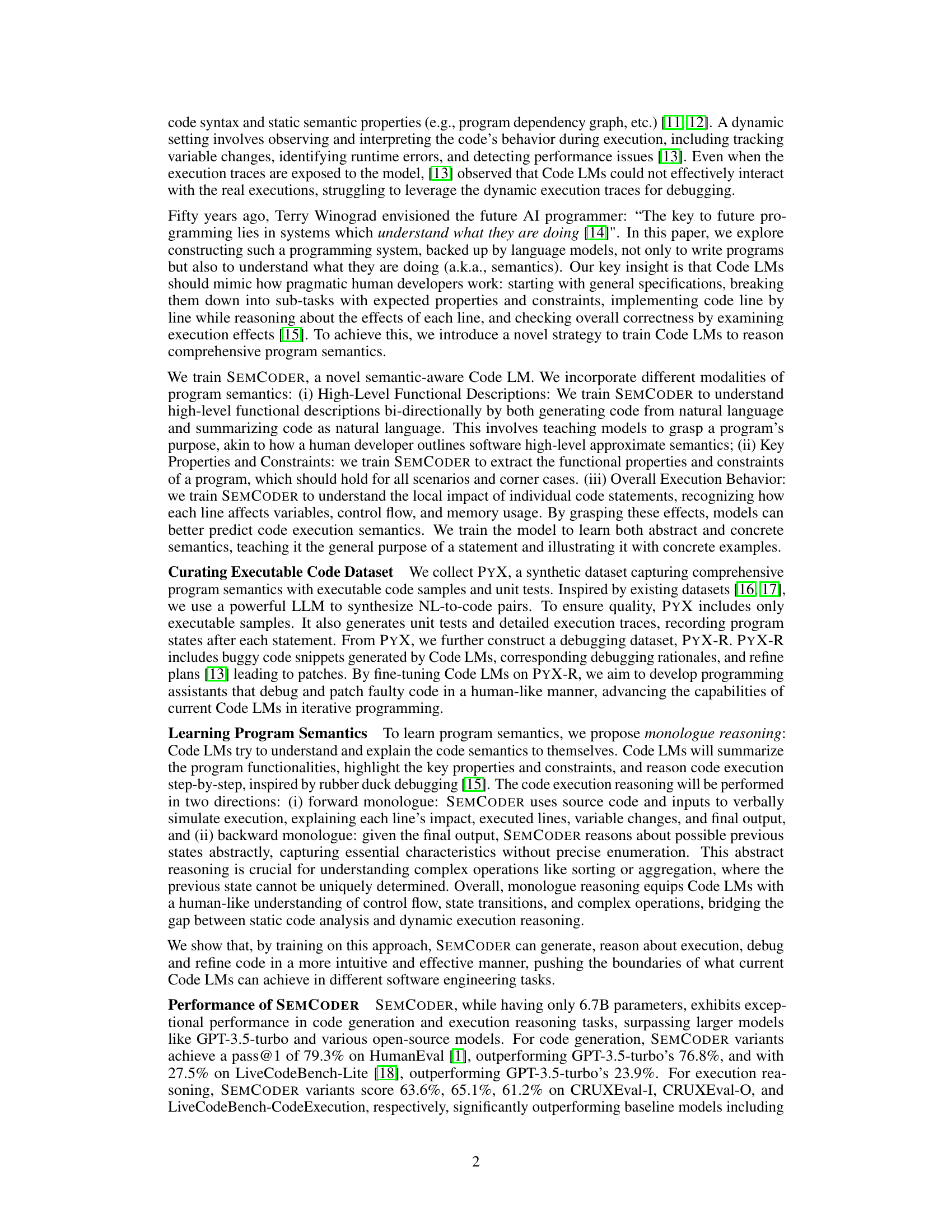

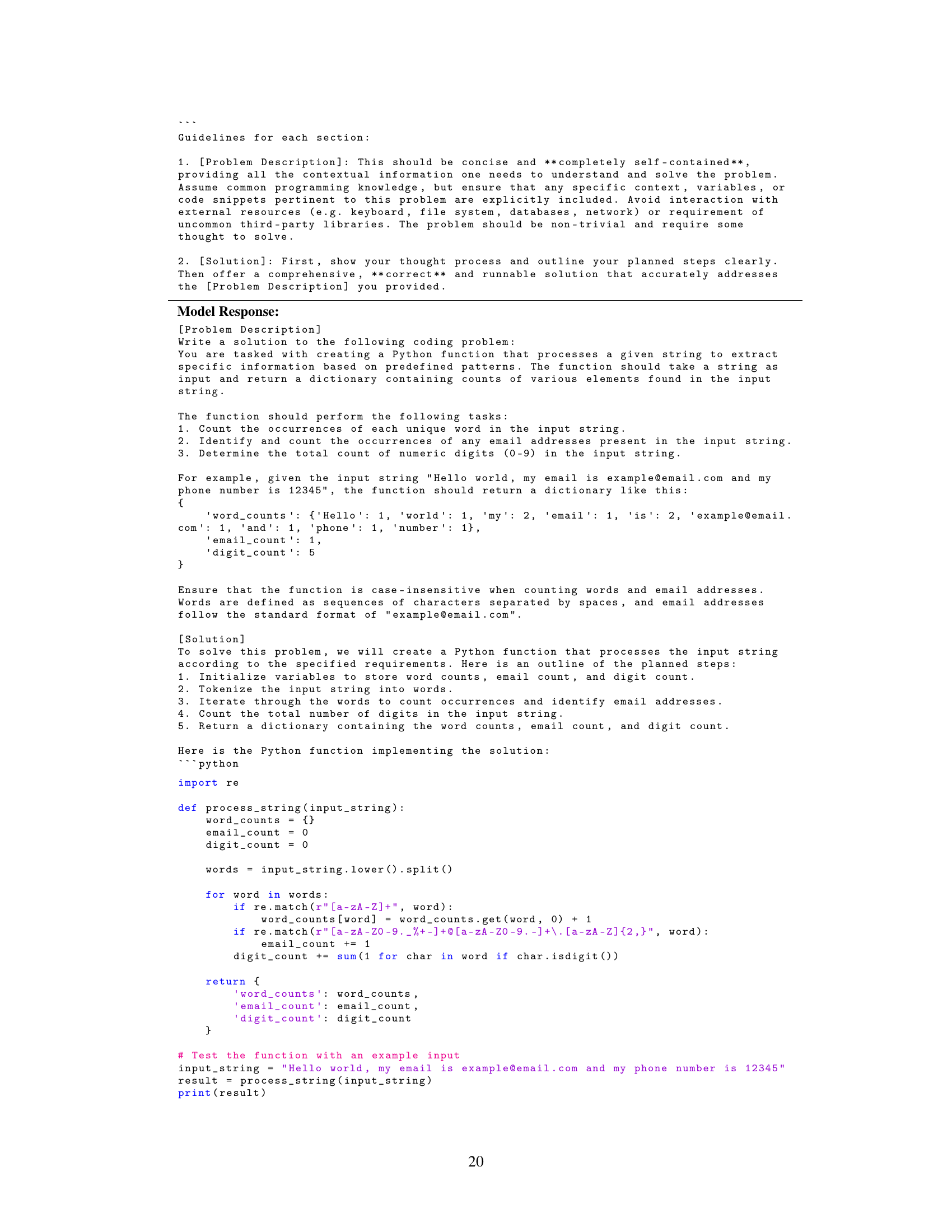

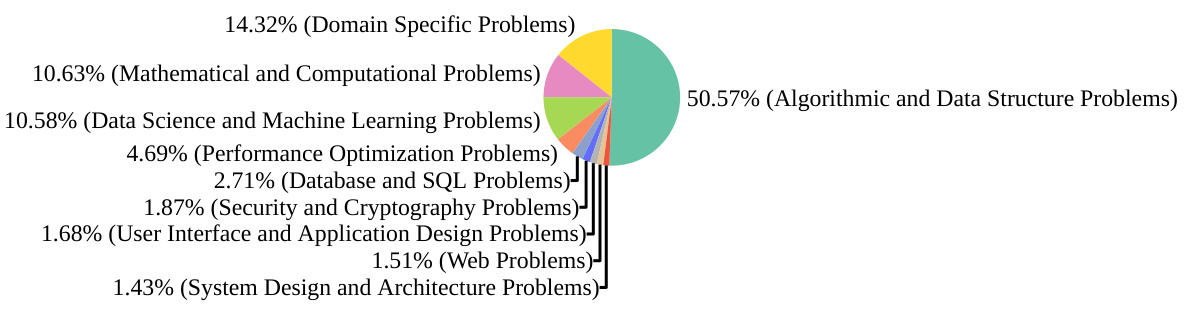

This figure illustrates the training strategy employed by SEMCODER. It highlights the incorporation of multiple modalities of program semantics during training. These modalities include approximate semantics (high-level description of the task), symbolic semantics (code representation), abstract semantics (key properties and constraints of the code), and operational semantics (step-by-step execution simulation). The figure uses a visual representation with boxes to depict the different semantic levels and how they’re connected in the training process. It shows how the model learns to link static code with dynamic execution behavior.

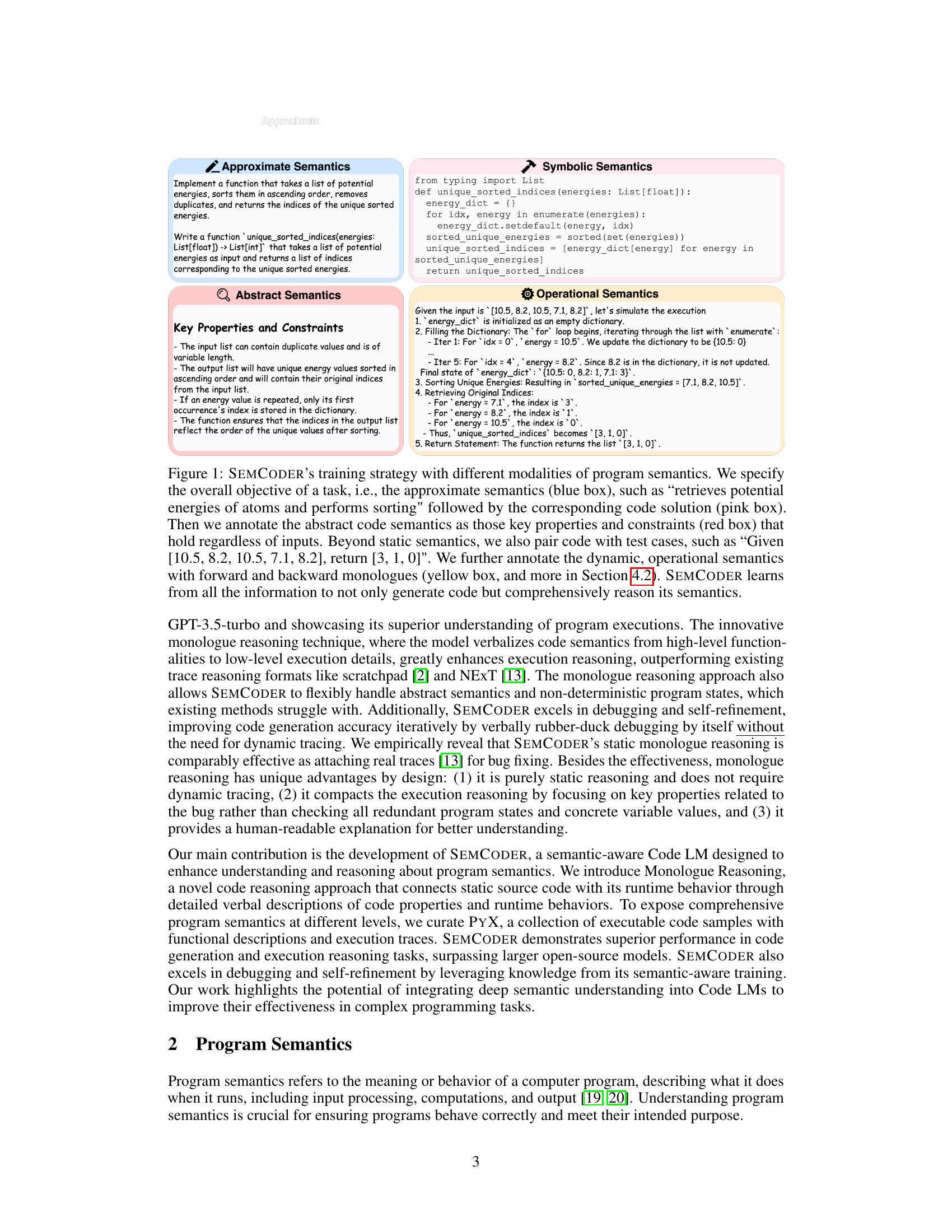

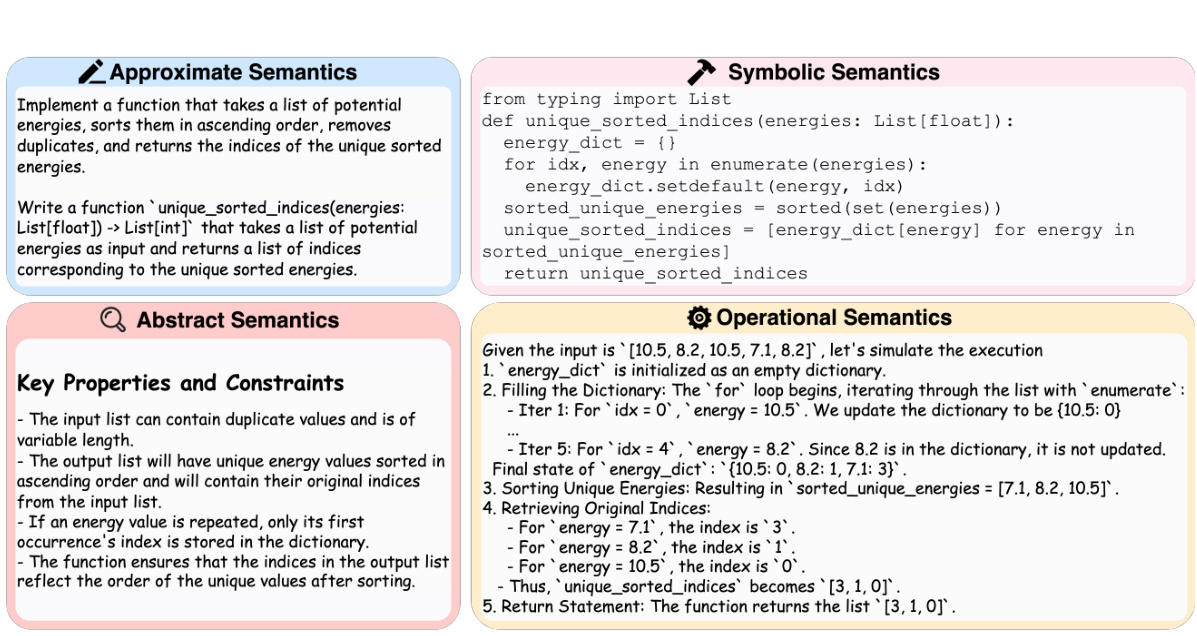

This table presents a comprehensive comparison of SEMCODER’s performance against various state-of-the-art code generation and execution reasoning models. It shows the pass@1 scores (the percentage of tests passed) on HumanEval (HEval), MBPP (a modified version of HumanEval), LiveCodeBench-Lite (LCB-Lite), CRUXEval-I, CRUXEval-O, and LiveCodeBench-Exec (LCB-Exec) for different model sizes and variants, including both base and instruction-tuned versions. The results highlight SEMCODER’s competitive performance, particularly in execution reasoning, even with a smaller parameter count compared to other models.

In-depth insights#

SEMCODER: Semantics#

SEMCODER’s approach to semantics is multifaceted and innovative. It moves beyond the limitations of previous Code LLMs by integrating three key modalities: high-level functional descriptions, providing a bird’s-eye view of the code’s purpose; key properties and constraints, identifying essential characteristics that must hold true; and operational semantics, simulating execution step-by-step to understand dynamic behavior. This comprehensive approach enables SEMCODER to excel at complex tasks like debugging and self-refinement, surpassing the capabilities of prior models by mimicking human verbal debugging or rubber-duck debugging. The use of monologue reasoning where the model explains the code’s behavior to itself is a particularly noteworthy element. This technique facilitates a deeper understanding and smoother integration of semantics from multiple dimensions, ultimately enhancing the model’s reasoning abilities significantly.

Monologue Reasoning#

The proposed “Monologue Reasoning” is a novel training strategy for Code LLMs that aims to bridge the gap between static code analysis and dynamic execution understanding. Instead of relying on external tools or traces, the model reasons about code semantics through self-explanation, mimicking human debugging practices like “rubber-duck debugging.” This involves generating both forward and backward monologues: forward, simulating execution step-by-step; backward, abstractly reasoning about prior states given the output. This approach enables a more nuanced understanding of program semantics, encompassing high-level functional descriptions, local execution effects, and overall input/output behavior. It is particularly effective in handling complex operations and non-deterministic scenarios, surpassing previous trace-based approaches. The unique value proposition lies in its purely static nature, requiring no dynamic tracing, while providing a human-readable explanation that facilitates better debugging and self-refinement capabilities.

Comprehensive Semantics#

The concept of “Comprehensive Semantics” in the context of code language models (LLMs) signifies a move beyond the traditional reliance on static code analysis. It emphasizes the need for deep semantic understanding that encompasses not only the syntax and structure of code but also its dynamic execution behavior, including variable changes, control flow, and overall input/output relationships. This holistic approach is crucial for complex tasks such as program debugging and repair, where simply predicting the next line of code is insufficient. Successfully implementing comprehensive semantics requires sophisticated techniques that link static code representation with dynamic runtime information, potentially using novel reasoning strategies such as monologue reasoning to mimic the verbal debugging process employed by human programmers. Achieving this deeper level of semantic awareness is key to bridging the gap between the capabilities of LLMs and the requirements of real-world programming tasks. The benefits extend to enhancing code generation, improving debugging capabilities, and potentially enabling self-refining abilities in LLMs, where the model can identify and correct its own errors.

PYX Dataset#

The PYX dataset, a cornerstone of the SEMCODER research, addresses the limitations of existing code language model (Code LLM) datasets by incorporating comprehensive program semantics. Unlike datasets relying solely on static code, PYX includes fully executable code samples, each paired with functional descriptions and unit tests. This approach enables Code LLMs to learn not only code generation but also semantic understanding encompassing high-level functionalities, key properties, and execution behaviors. The inclusion of detailed execution traces further bridges the gap between static code and dynamic execution, enhancing the model’s ability to reason about program behavior. PYX’s design directly supports the novel ‘monologue reasoning’ training strategy, facilitating the development of Code LLMs that can effectively debug and self-refine code. The curating process of PYX, while synthetic, prioritizes high quality and comprehensiveness, ensuring robust training data.

Future Work#

The paper’s ‘Future Work’ section suggests several promising avenues. Improving intermediate reasoning steps in the model’s process is crucial; currently, while final answers are accurate, intermediate steps sometimes contain flaws. Automating the annotation process for monologues, currently done manually with powerful LLMs, would significantly improve efficiency and scalability. Exploring training with larger base models could eliminate reliance on external LLMs for annotation and improve the model’s overall performance. Finally, directly integrating execution reasoning into code generation promises to improve the model’s capability for iterative programming and self-refinement, offering a more integrated approach to complex coding tasks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates SEMCODER’s training strategy, showcasing how different modalities of program semantics are incorporated. Approximate semantics (high-level description of the task), symbolic semantics (code representation), abstract semantics (key properties and constraints), and operational semantics (step-by-step execution simulation) are all included in the training process. This multi-faceted approach enables SEMCODER to develop a more comprehensive understanding of program semantics, bridging the gap between static code analysis and dynamic execution reasoning.

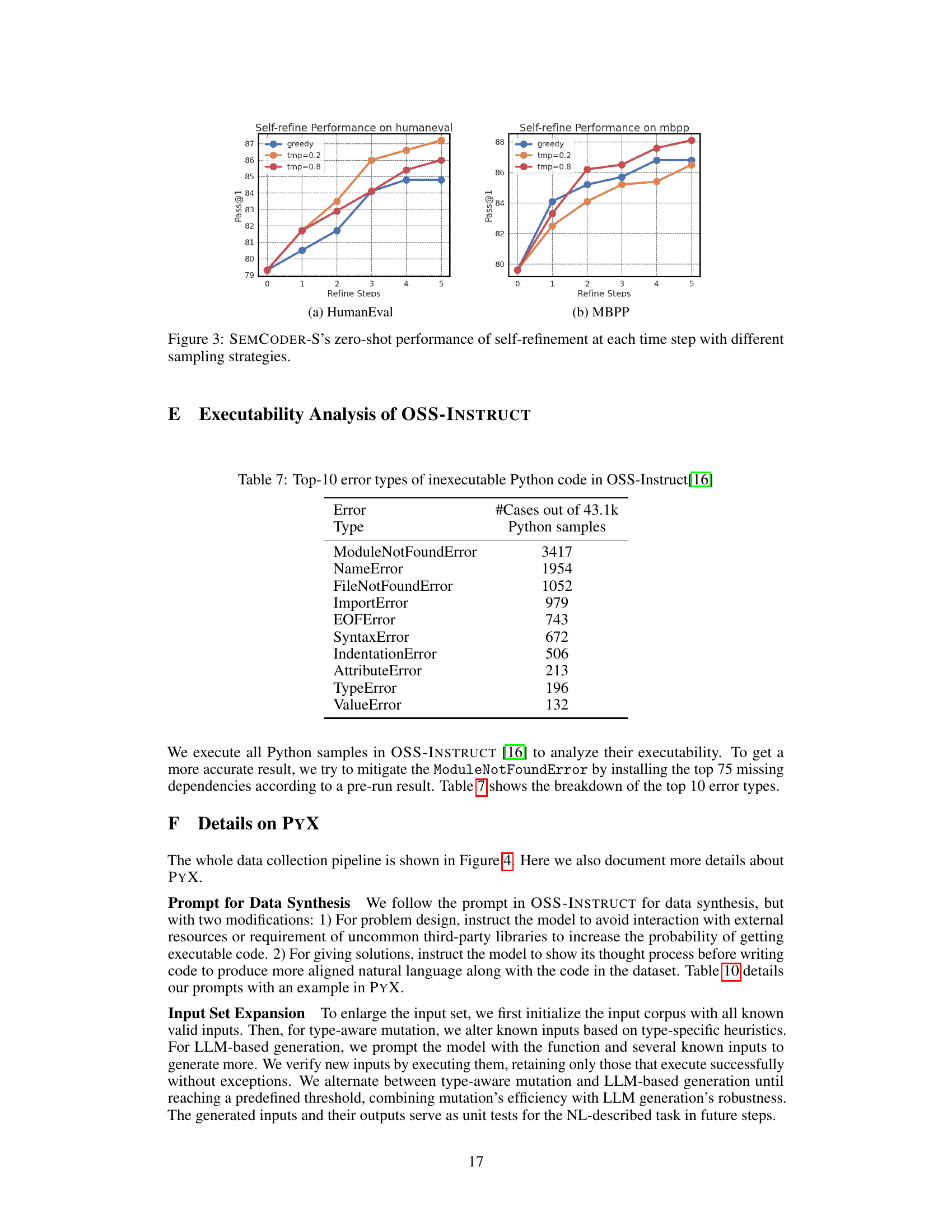

This figure shows the performance of the SEMCODER-S model in a self-refinement task, where the model iteratively refines its code based on test results. It specifically demonstrates zero-shot performance across different sampling strategies (‘greedy’, ’temp=0.2’, ’temp=0.8’) on two code generation benchmarks (HumanEval and MBPP) over five refinement steps. The graphs illustrate how the model’s pass@1 score evolves with each refinement iteration under various sampling methods. This visualization helps assess the model’s ability to improve code quality through iterative debugging and self-correction. The ’temp’ parameter likely refers to temperature settings for sampling during generation, influencing the randomness of the output and potentially affecting the refinement process.

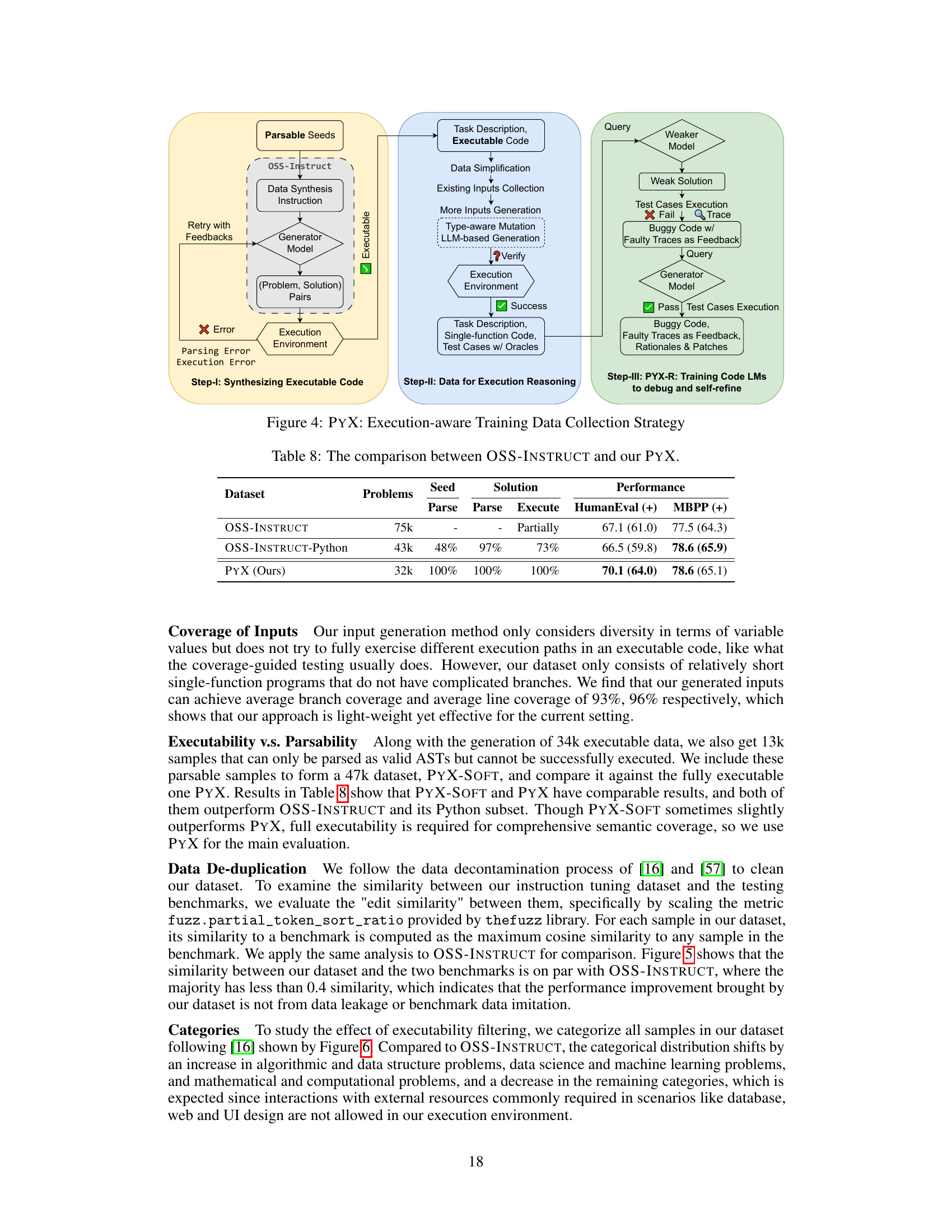

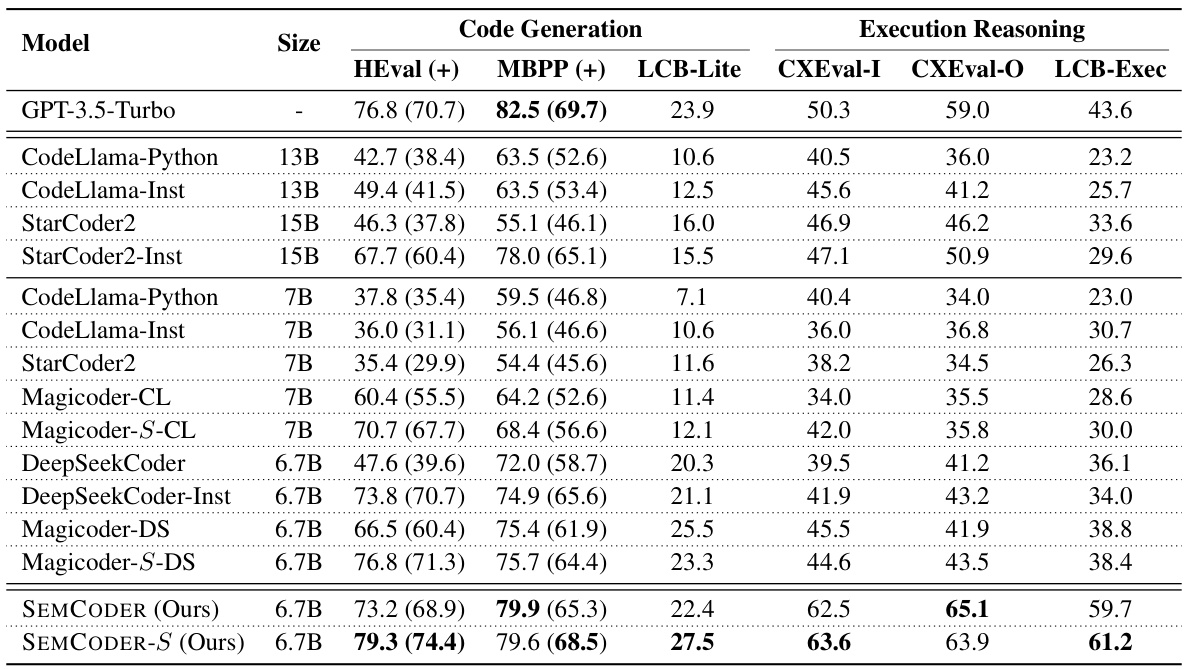

This figure illustrates the three-step process used to create the PYX dataset. Step I focuses on synthesizing executable code using an LLM, filtering out non-executable samples. Step II generates additional inputs through type-aware mutation and LLM-based generation and incorporates test cases to gather execution traces. Step III introduces bugs, generating faulty execution traces and debugging rationales, ultimately building the PYX-R dataset for debugging and self-refinement training.

This figure shows the distribution of edit similarities between the PYX dataset and two popular benchmarks (OSS-Instruct HumanEval and OSS-Instruct MBPP). The x-axis represents the edit similarity, a measure of how similar the code samples in PYX are to the code samples in the benchmarks. The y-axis represents the probability density. The figure visually demonstrates that the PYX dataset is distinct from the benchmarks, with minimal overlap in edit similarity scores, indicating the dataset’s unique characteristics and avoiding potential data leakage.

This figure illustrates the training strategy used for SEMCODER, highlighting its use of different modalities of program semantics. Approximate semantics (blue box) gives the overall objective. Symbolic semantics (pink box) shows the code solution. Key properties and constraints (red box) represent abstract code semantics. Operational semantics (yellow box) includes test cases and dynamic aspects of the program execution. The figure shows how SEMCODER learns from all of these aspects to not only generate code but also reason comprehensively about the semantics. The approach incorporates high-level functional descriptions, local execution effects, and overall input/output behavior, linking static code with dynamic execution.

More on tables

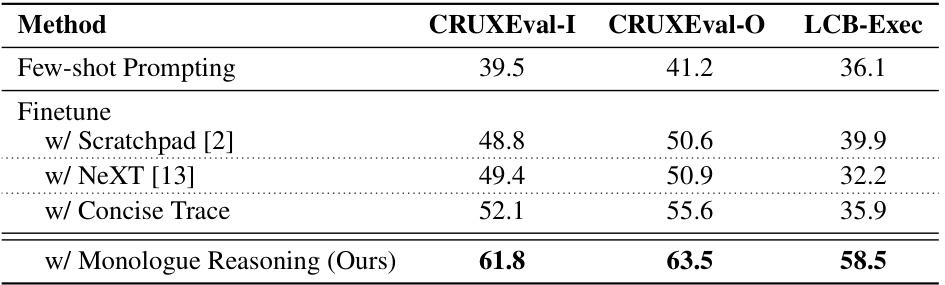

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing different methods for execution reasoning on the tasks of input and output prediction. The methods compared include few-shot prompting, fine-tuning with scratchpad reasoning, fine-tuning with NeXT trace format, fine-tuning with concise trace format, and the proposed monologue reasoning approach. The evaluation metrics used are CRUXEval-I, CRUXEval-O, and LCB-Exec. The table shows that the proposed monologue reasoning approach significantly outperforms the other methods across all three evaluation metrics.

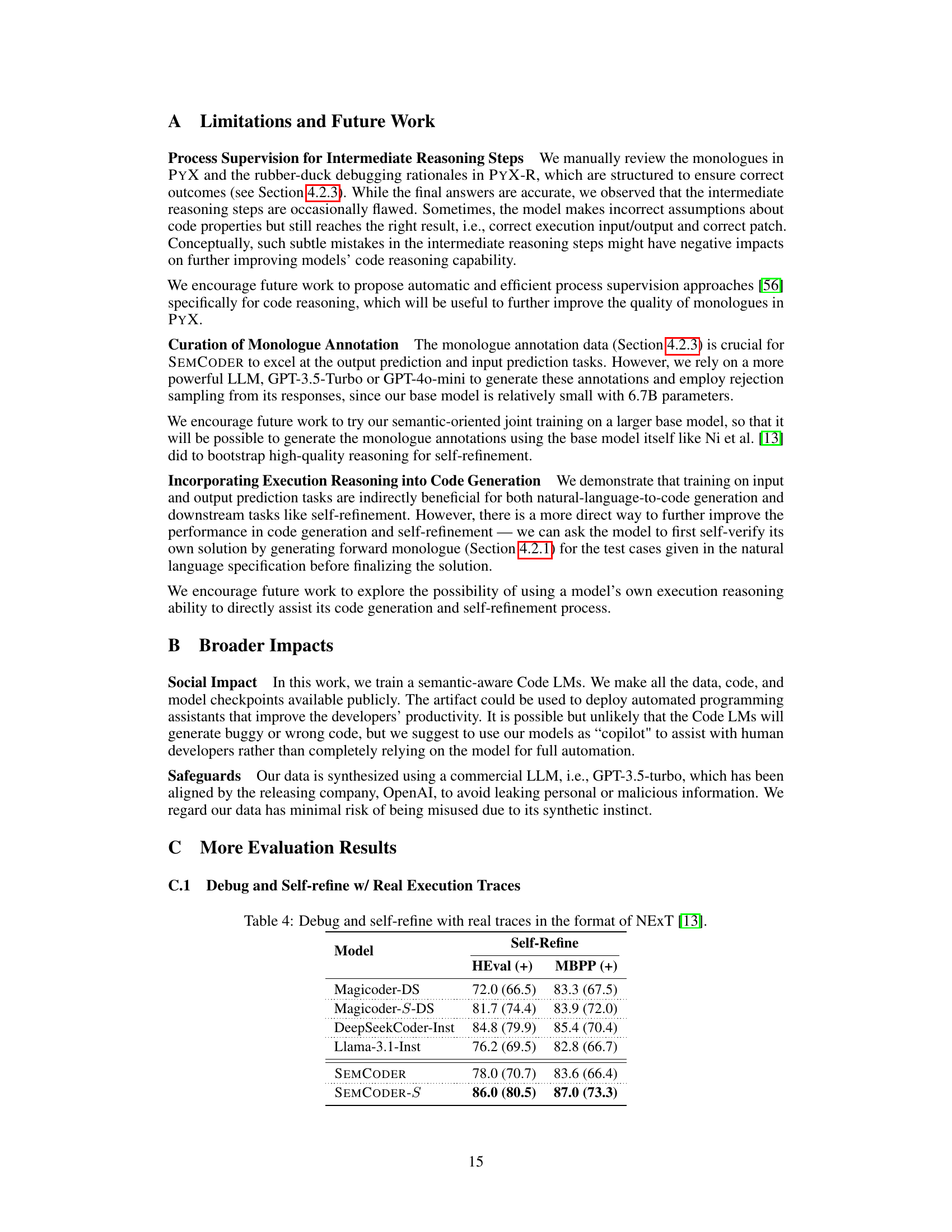

This table presents the results of iterative debugging and self-refinement experiments. It compares the performance of several Code LLMs (Magicoder-DS, Magicoder-S-DS, DeepSeekCoder-Inst, Llama-3.1-Inst, SEMCODER, SEMCODER-S) on two metrics: HumanEval and MBPP. The results are shown for both zero-shot prompting and fine-tuning with the PYX-R dataset. The table highlights the improvements in iterative programming capabilities achieved through the combination of model training and the use of rubber-duck debugging.

This table presents the results of iterative debugging and self-refinement experiments. Two versions of SEMCODER (base and advanced) are compared against four state-of-the-art instruction-tuned code LLMs (Magicoder-DS, Magicoder-S-DS, DeepSeekCoder-Inst, and Llama-3.1-Inst) using two metrics: HEval and MBPP. Both zero-shot prompting and fine-tuning with PYX-R (a debugging dataset) are assessed. The results show the performance in terms of HEval and MBPP after five iterative refinements.

This table presents a comparison of SEMCODER’s performance against various other code large language models (Code LLMs) across different code generation and execution reasoning benchmarks. The benchmarks used are HumanEval, MBPP, LiveCodeBench-Lite (LCB-Lite), CRUXEval-I, CRUXEval-O, and LCB-Exec. Results are shown as the percentage of tasks successfully completed (pass@1). The table helps illustrate SEMCODER’s competitive performance, particularly its effectiveness in execution reasoning, even with a smaller parameter count compared to other models.

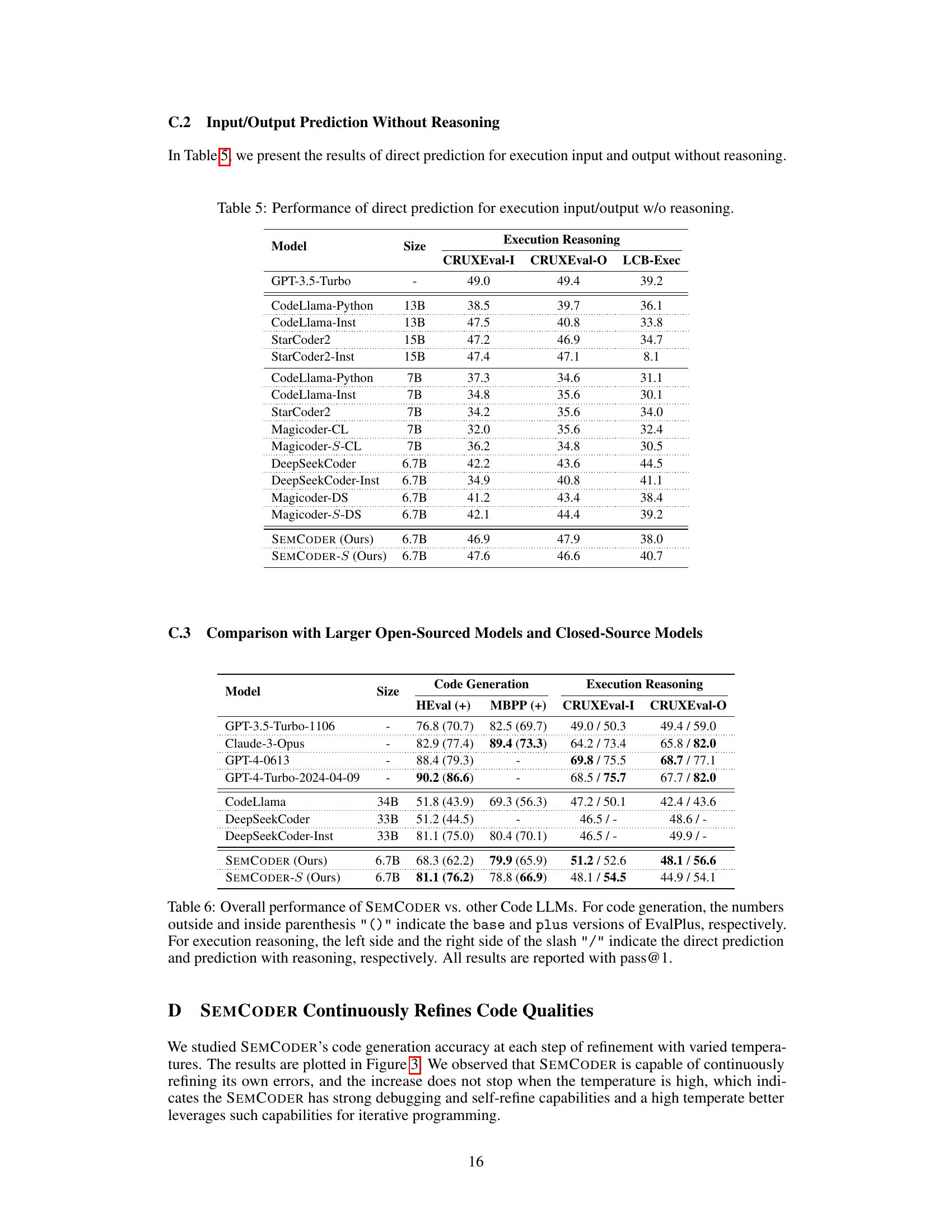

This table presents the overall performance comparison of the SEMCODER model against various baselines on code generation and execution reasoning tasks. For code generation, it shows the results on HumanEval and MBPP benchmarks, differentiating between base and enhanced versions using EvalPlus. For execution reasoning, the table includes performance on CRUXEval-I, CRUXEval-O and LiveCodeBench, demonstrating the model’s capabilities in understanding and reasoning about program execution.

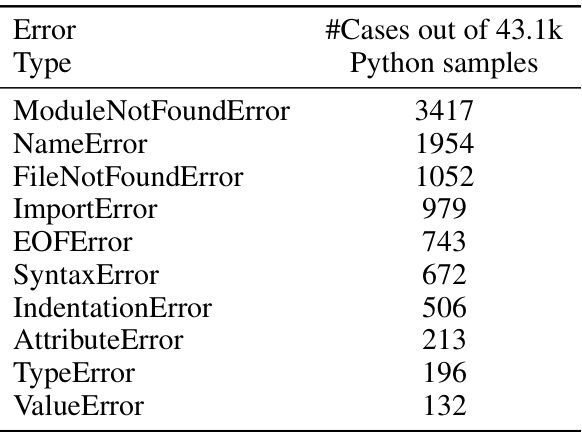

This table presents the top ten most frequent error types encountered when executing Python code from the OSS-Instruct dataset. The dataset contains 43.1k Python samples, a significant portion of which (11.6k, or 26.9%) are found to be non-executable. This table details the specific error types and their counts, providing insights into common issues during code generation, and highlighting the need for robust executable code generation processes.

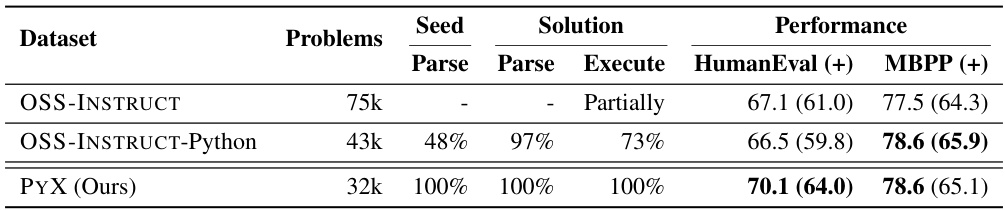

This table compares the characteristics of two datasets used in the paper: OSS-INSTRUCT and PYX. It shows the number of problems in each dataset, the percentage of seeds that could be parsed and executed, and the performance on two code generation benchmarks (HumanEval and MBPP). The results highlight that PYX, a dataset curated by the authors, has a higher quality of executable code compared to OSS-INSTRUCT.

Full paper#