↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current computer vision models struggle with motion segmentation in scenarios involving random dot stimuli, unlike human perception. This is a major limitation for various applications, especially those needing appearance-agnostic motion analysis. The issue stems from the inability of state-of-the-art optical flow models to accurately estimate motion patterns in such ambiguous situations.

This research addresses this by introducing a neuroscience-inspired motion energy model. This model significantly outperforms existing optical flow models in zero-shot motion segmentation tasks, matching human performance. The findings highlight the importance of incorporating neuroscience insights into the development of computer vision models, leading to more robust and human-like motion perception capabilities. This innovative approach contributes to bridging the gap between neuroscience and computer vision and provides a compelling example of the benefits of biologically-inspired models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it bridges the gap between neuroscience and computer vision, demonstrating how a biologically-inspired model surpasses state-of-the-art methods in zero-shot generalization. This opens new avenues for developing more robust and human-like AI systems for motion perception, particularly in handling complex scenarios such as those involving moving random dots.

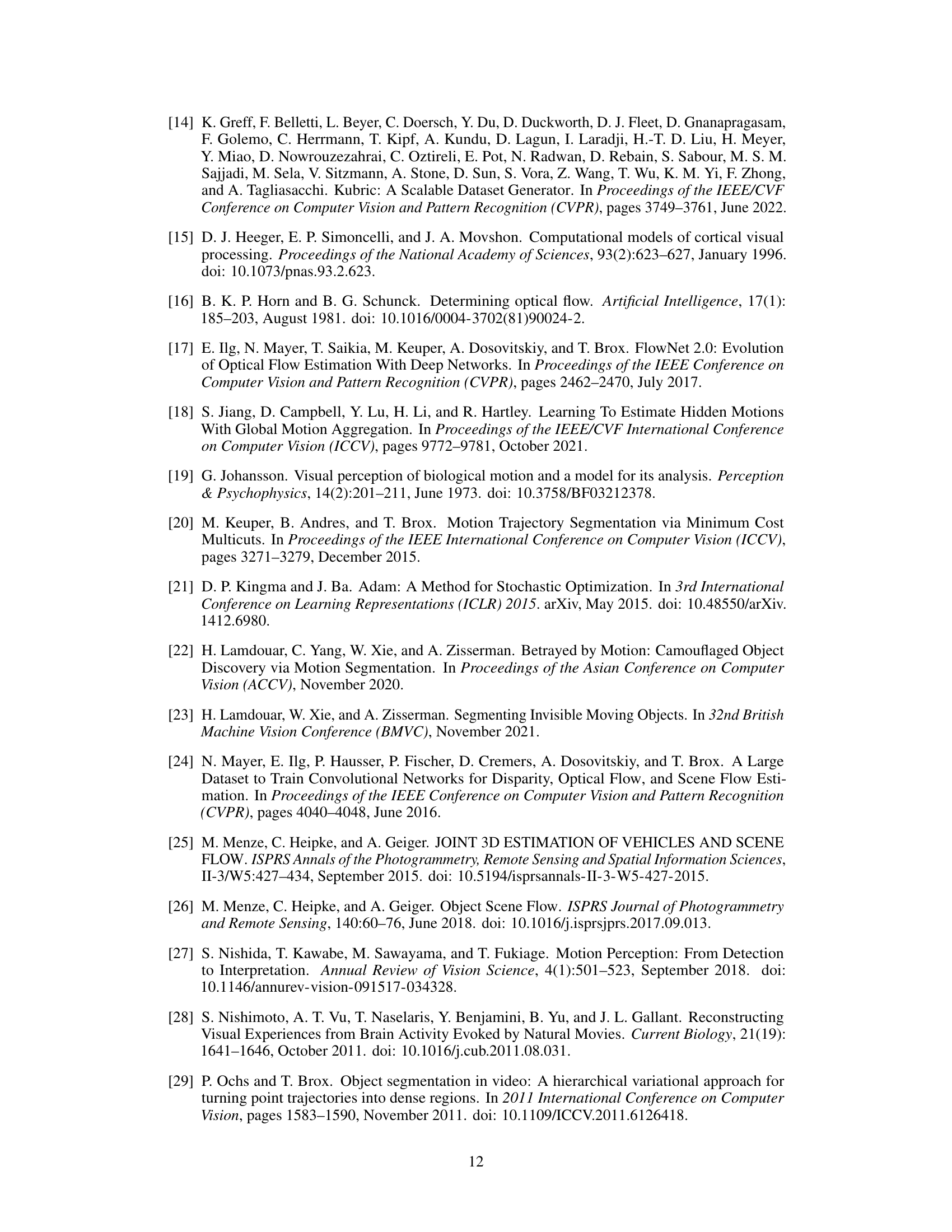

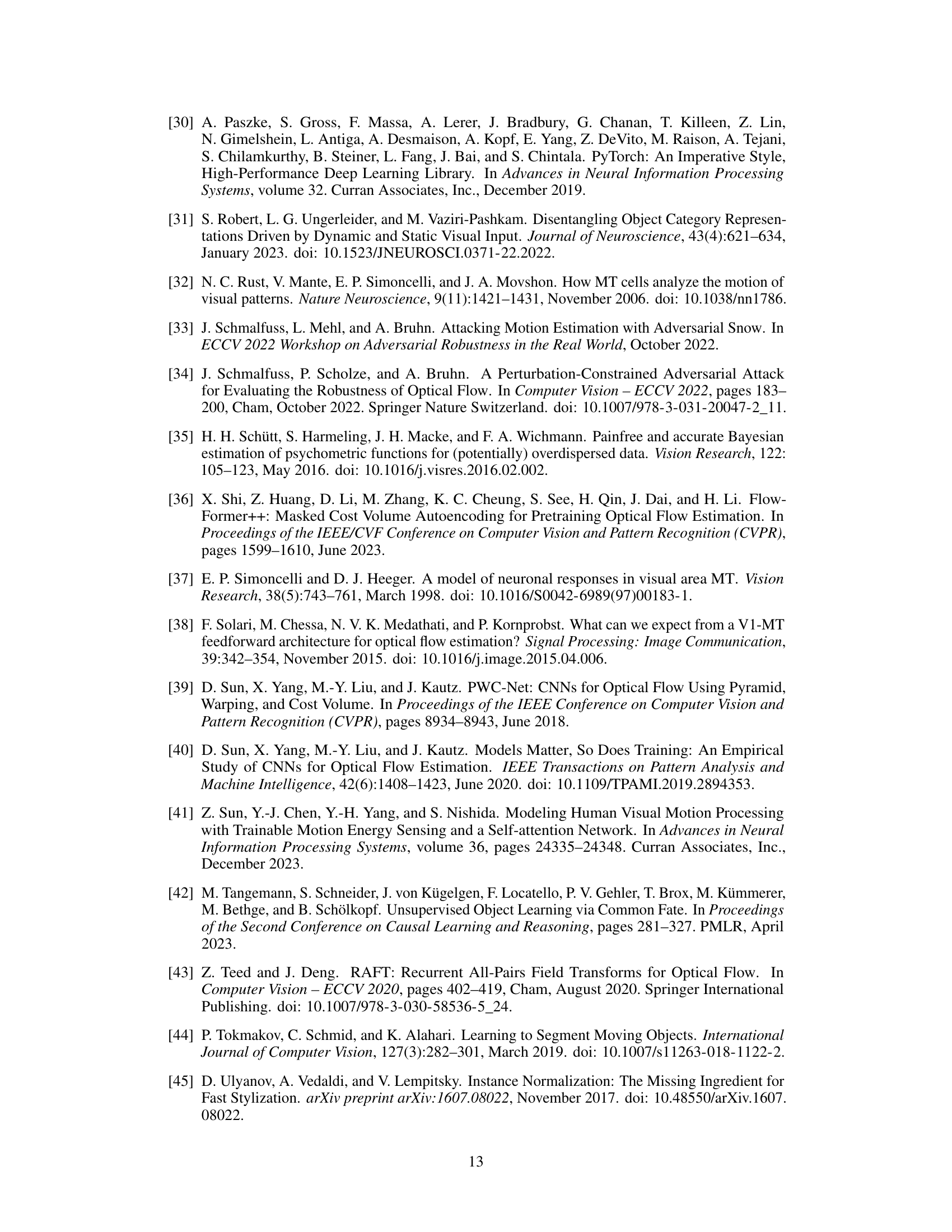

Visual Insights#

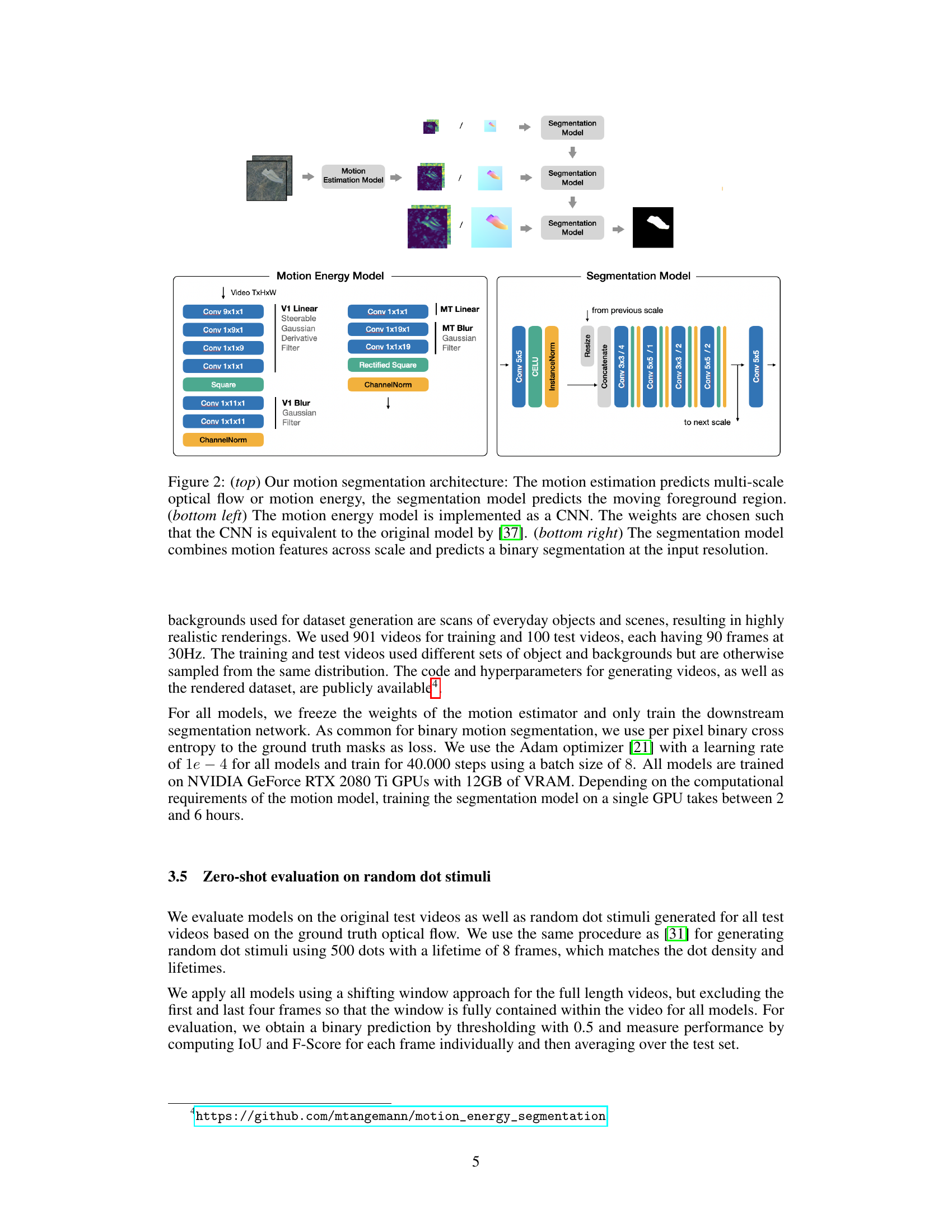

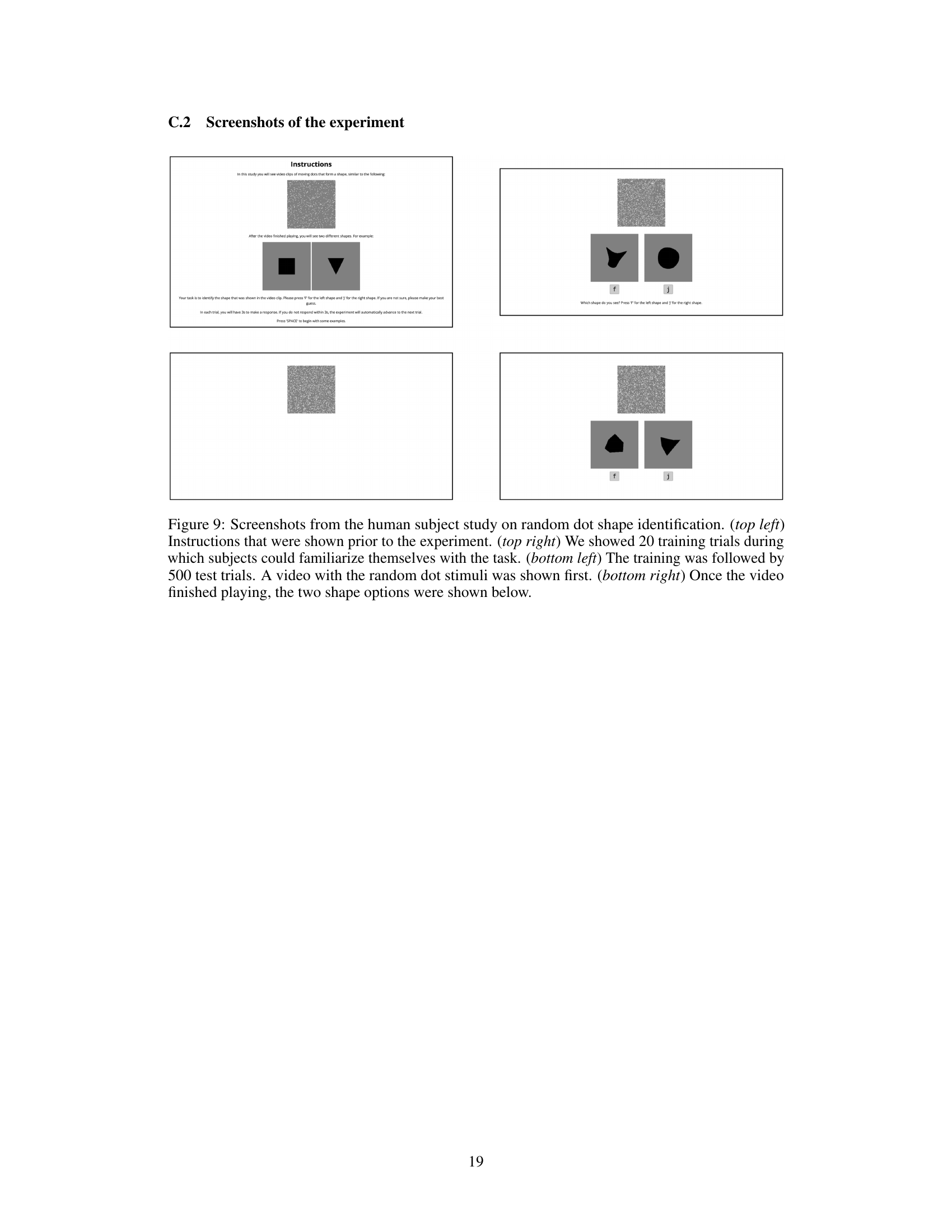

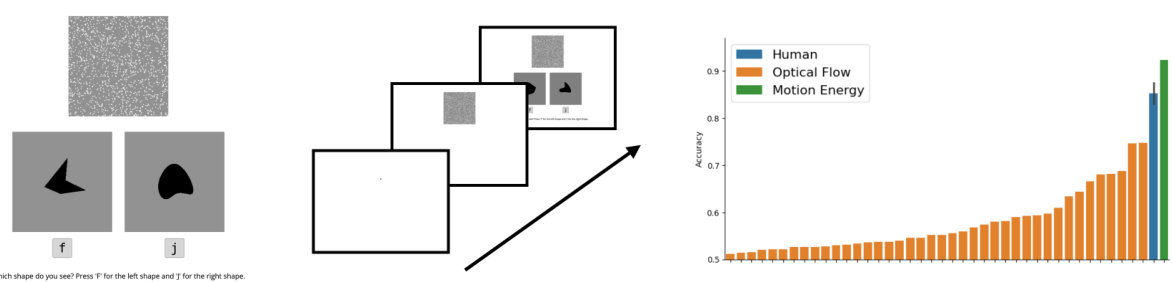

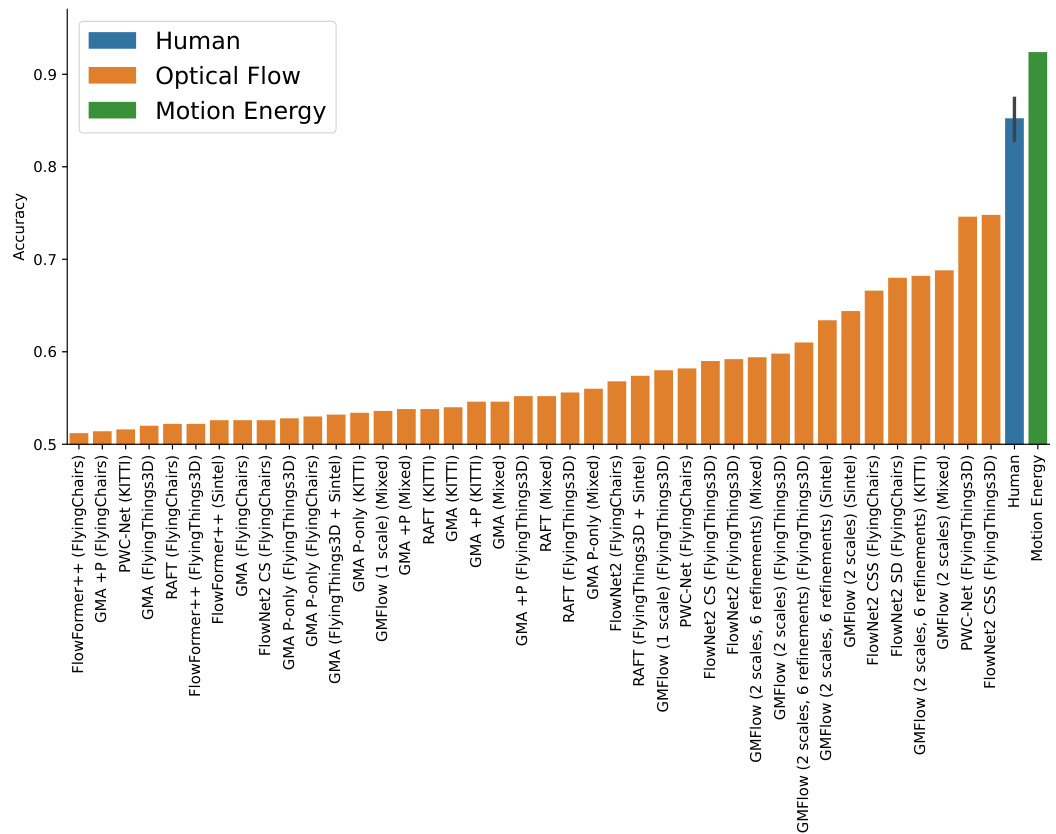

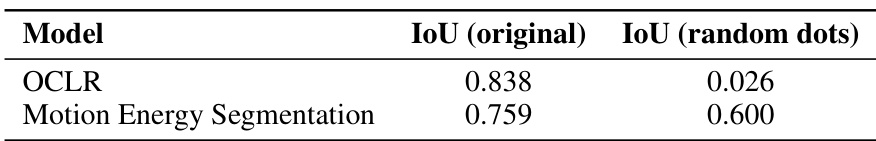

This figure compares the performance of various optical flow models and a neuroscience-inspired motion energy model on a figure-ground segmentation task. The models are tested on both original videos and corresponding random dot stimuli that preserve the original motion patterns but lack texture information. The results show that the motion energy model outperforms the optical flow models in generalizing to the random dot stimuli, demonstrating a more human-like zero-shot generalization ability.

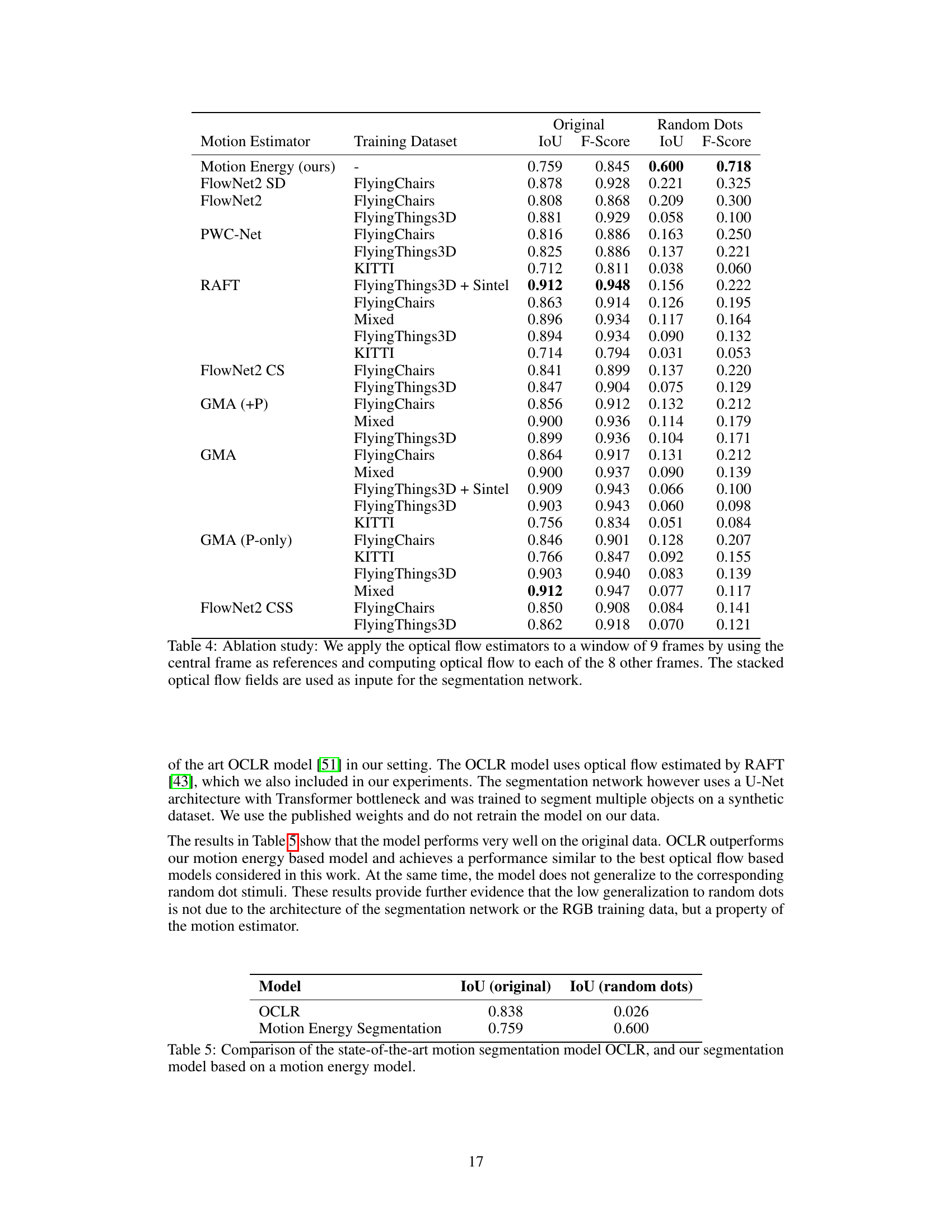

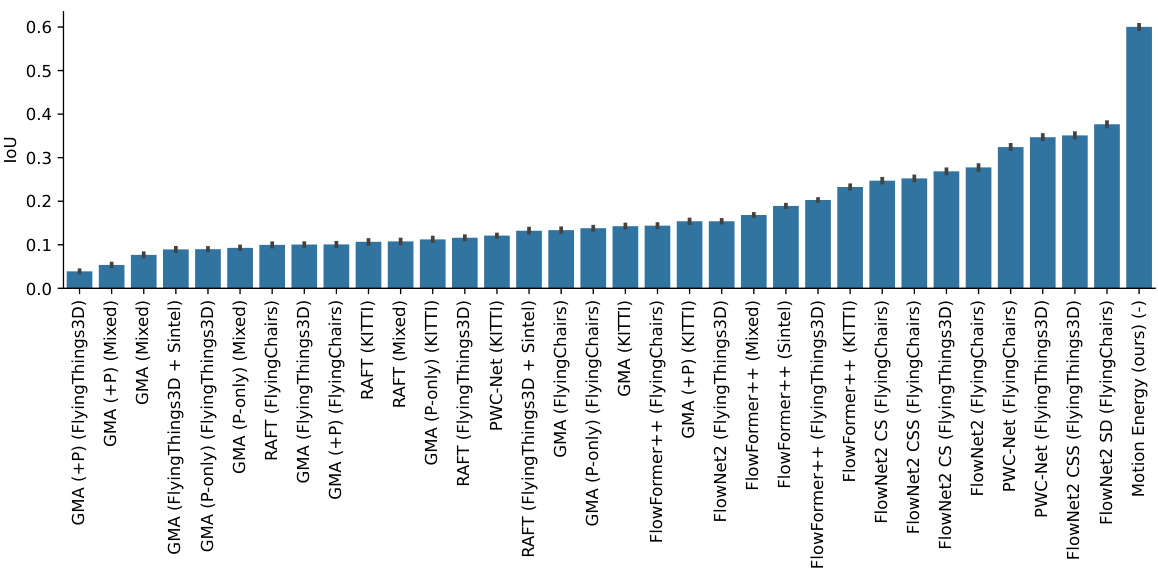

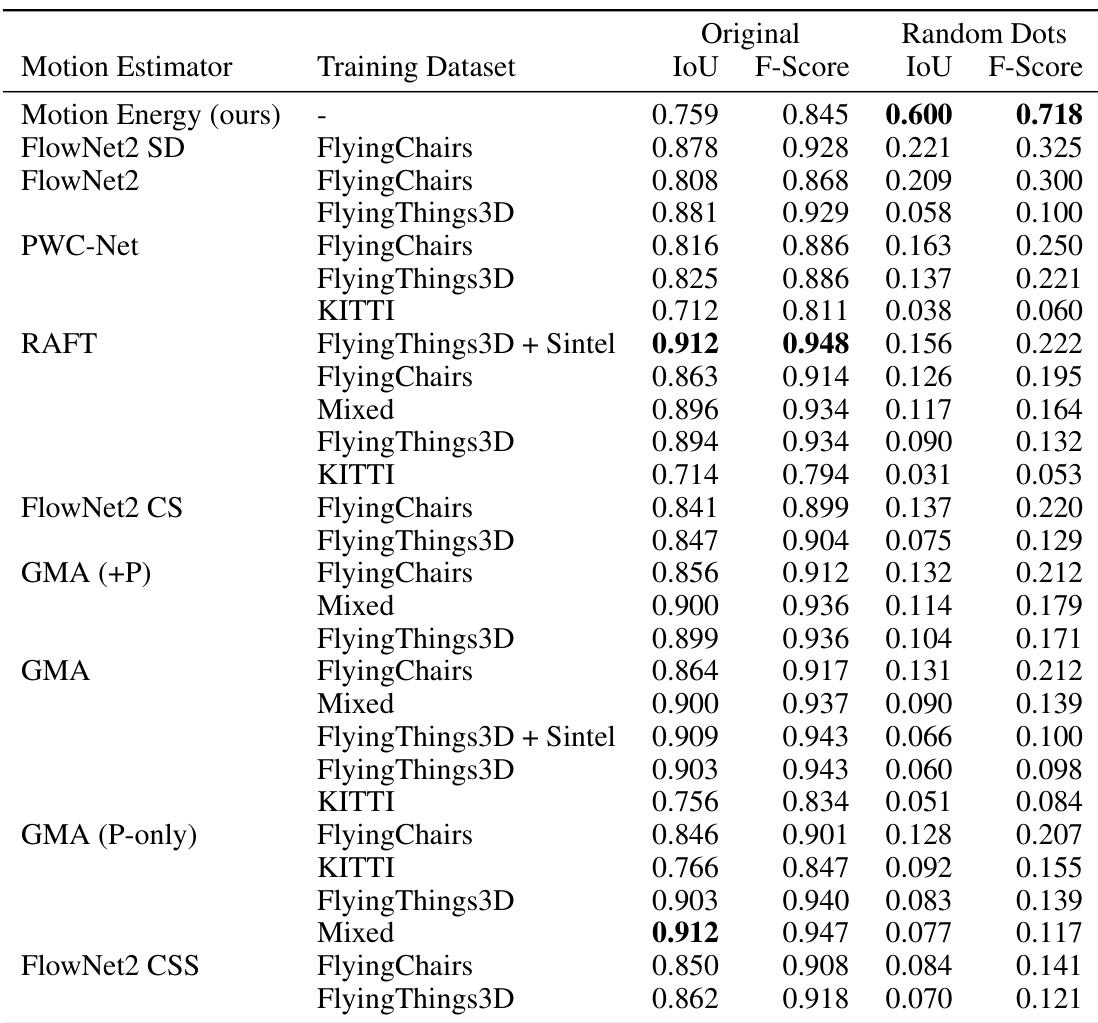

This table presents a comparison of various motion estimation models’ performance on both original videos and their corresponding random dot stimuli. It shows the Intersection over Union (IoU) and F-Score metrics for each model, broken down by training dataset and stimulus type (original/random dots). The results highlight the significant difference in zero-shot generalization capabilities between different model types, particularly showcasing the superiority of the neuroscience-inspired motion energy model.

In-depth insights#

Common Fate’s Role#

The Gestalt principle of “common fate” posits that elements moving together are perceived as belonging together. This research explores its computational basis, particularly its zero-shot generalization ability—the capacity to segment moving objects even in novel, unseen textures or random dot patterns, as demonstrated in human perception. The study highlights a critical discrepancy between human perception’s seamless generalization to random dot stimuli and the struggles of state-of-the-art optical flow models. Neuroscience-inspired motion energy models, however, successfully replicate this human capability. This finding strongly suggests that common fate’s role in human vision is computationally distinct from the prevailing approaches in computer vision. Spatio-temporal filtering, the core of the motion energy model, offers a compelling alternative for achieving human-like performance in zero-shot motion segmentation tasks. The success of this biologically-inspired model reinforces the significance of incorporating neuroscientific insights in improving computer vision systems, ultimately paving the way for more robust and human-like object perception.

Motion Energy Wins#

The heading “Motion Energy Wins” suggests a key finding where a neuroscience-inspired motion energy model outperformed state-of-the-art computer vision models in a specific task, likely zero-shot segmentation of random dot stimuli. This is significant because it highlights the potential of biologically-plausible models in computer vision, which often struggle with generalization to unseen data. The success of the motion energy model might stem from its spatio-temporal filtering approach, which is different from the deep feature matching methods used in many optical flow models. This difference could explain why motion energy models generalize better to random dot patterns where appearance cues are absent, relying primarily on motion information. The result implies that incorporating insights from neuroscience might improve the performance and robustness of computer vision systems and also suggests that current deep learning approaches might not perfectly replicate human motion perception. Further research could investigate the limitations of motion energy models and explore ways to combine them with deep learning techniques for better performance across various tasks and datasets.

Zero-Shot Generalization#

The concept of “Zero-Shot Generalization” is a significant aspect of the research, exploring the ability of models to perform tasks they haven’t been explicitly trained on. The paper investigates this capability within the context of motion segmentation, particularly with random dot stimuli. A key finding is the superior performance of a neuroscience-inspired motion energy model compared to state-of-the-art optical flow models. This highlights the importance of biologically-plausible model architectures for achieving human-like generalization. The study reveals a crucial limitation of current computer vision models, demonstrating their lack of robustness when faced with unseen data types. Therefore, this research emphasizes the need for moving beyond purely data-driven approaches and integrating knowledge of human visual processing. The impressive zero-shot capabilities of the motion energy model suggest a pathway toward more robust and human-like AI systems by drawing inspiration from neuroscience.

Human-Level Matching#

A hypothetical section titled ‘Human-Level Matching’ in a research paper would likely delve into the comparison of model performance against human capabilities. It would investigate how closely the developed model approaches human-level accuracy and efficiency in a given task. This section would need to present a robust experimental design, including human subject participation to establish a baseline. Key aspects would include a clear definition of ‘human-level,’ objective metrics for comparing human and machine performance, and statistical analysis demonstrating significant similarities or differences. Crucially, the discussion should address the limitations and potential biases in both the model and human performance assessment, and the extent of generalization to other tasks or datasets. Ultimately, the section aims to show whether the model not only achieves high accuracy but also performs the task in a way that resembles human cognitive strategies. The existence of human-level matching would have significant implications, offering insights into the nature of intelligence and potentially paving the way for more human-like AI systems.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Expanding the motion energy model to handle more complex scenes and multiple moving objects is crucial to bridging the gap with the performance of state-of-the-art optical flow methods in natural videos. Investigating the interplay between motion estimation and object segmentation in the human visual system through psychophysical experiments would provide a better understanding of how biological systems solve this problem. Developing more robust motion estimation models using a hybrid approach, combining the strengths of both neuroscience-inspired models and deep learning techniques, would be highly beneficial. Finally, it would be insightful to investigate how the brain resolves the inherent ambiguities in motion signals, especially in situations with cluttered backgrounds or occlusions, and incorporate these insights into more biologically plausible computational models.

More visual insights#

More on figures

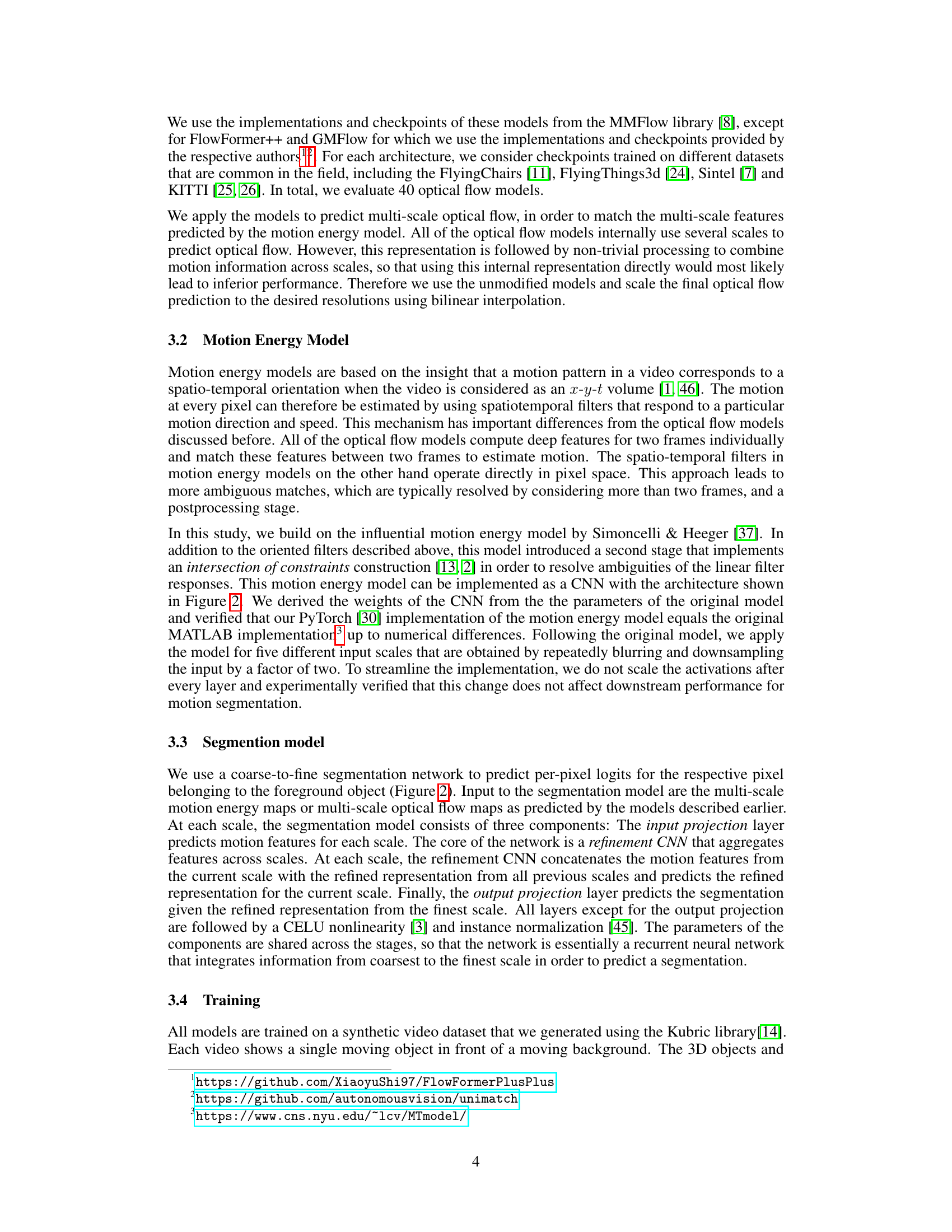

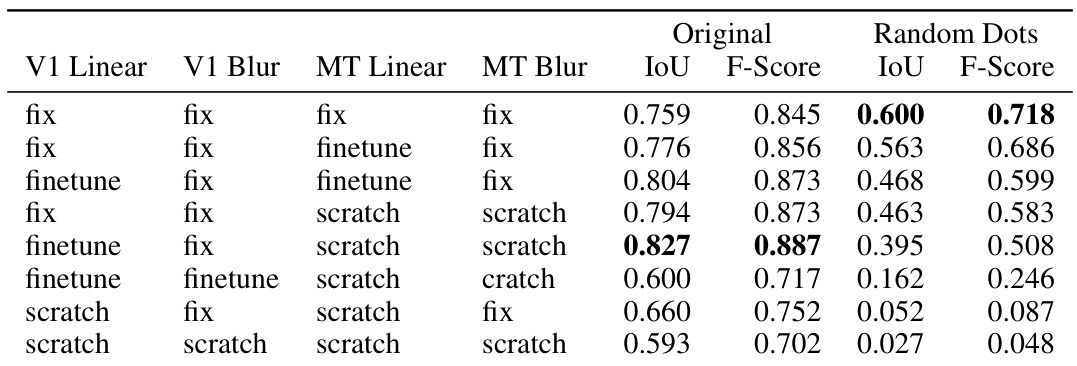

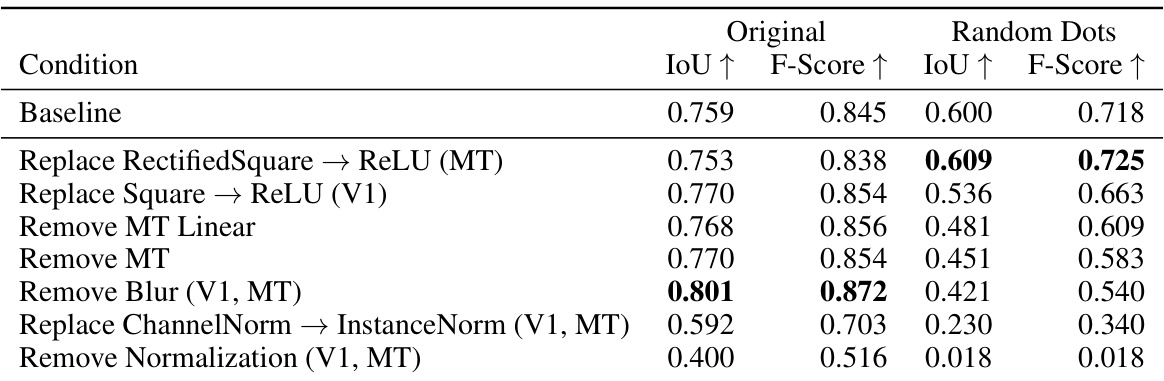

This figure illustrates the architecture of the motion segmentation model used in the paper. It’s a two-stage process. The first stage is motion estimation, which can use either optical flow or a neuroscience-inspired motion energy model. This stage produces multi-scale motion features. The second stage is a segmentation model which is a CNN that takes these multi-scale features as input and predicts a binary segmentation mask. The motion energy model itself is shown as a CNN, where the weights are derived from a pre-existing model in the literature. This ensures that the model is both biologically inspired and computationally efficient.

This figure compares the performance of various optical flow models and a neuroscience-inspired motion energy model on a figure-ground segmentation task using random dot stimuli. The random dot stimuli retain the motion patterns of original videos, but lack informative appearance features. The results visually demonstrate the superior generalization ability of the motion energy model compared to the optical flow models when dealing with stimuli lacking distinct texture information.

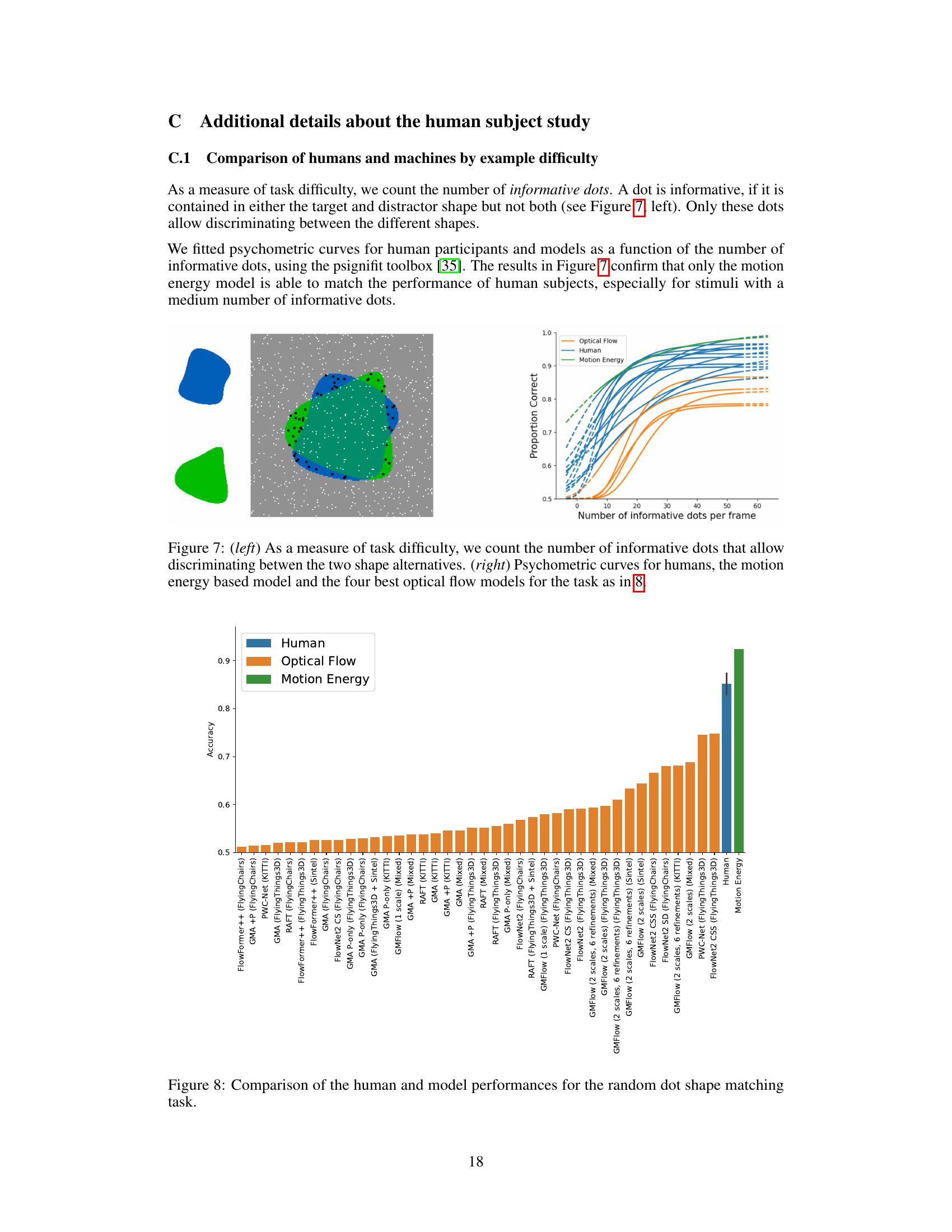

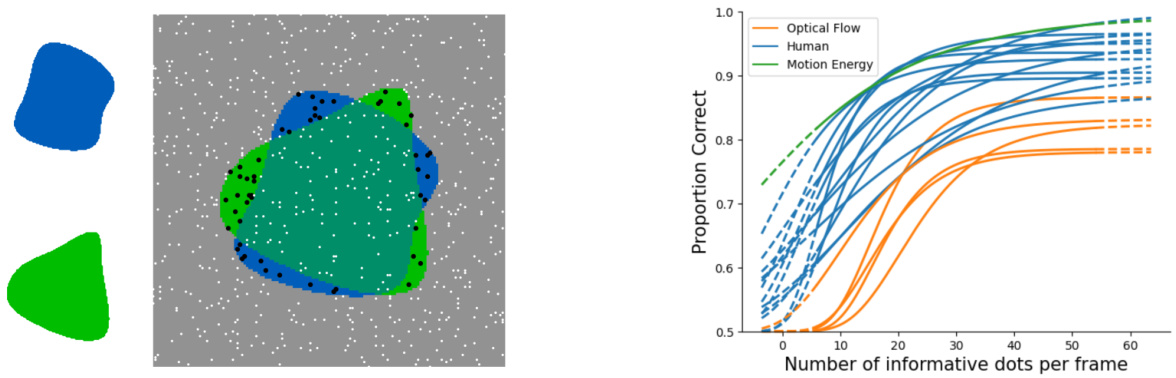

This figure presents a comparison of human and machine performance on a shape identification task using random dot stimuli. The task involved identifying a target shape embedded within a video of moving random dots. The figure shows that human participants significantly outperformed all optical flow-based models, yet were matched by the motion energy model, demonstrating the efficacy of the motion energy model for zero-shot generalization to random dot stimuli.

This bar chart displays the Intersection over Union (IoU) scores achieved by various motion estimation models on a random dot stimuli segmentation task. The models are ordered from lowest to highest IoU, clearly demonstrating the superior performance of the motion energy model compared to state-of-the-art optical flow models on this zero-shot generalization task. The data presented mirrors the information from Table 1 but in a visual format that facilitates comparison of model performance.

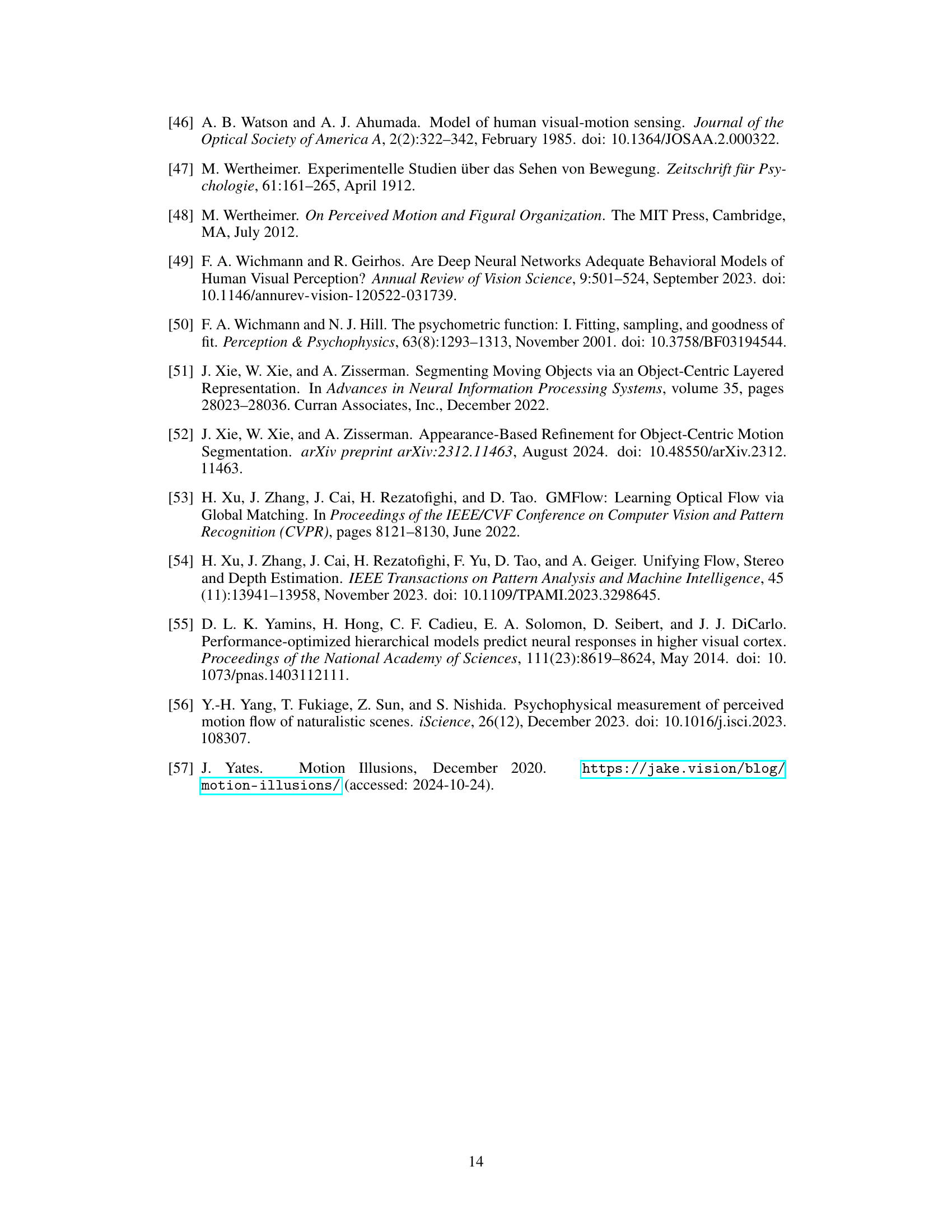

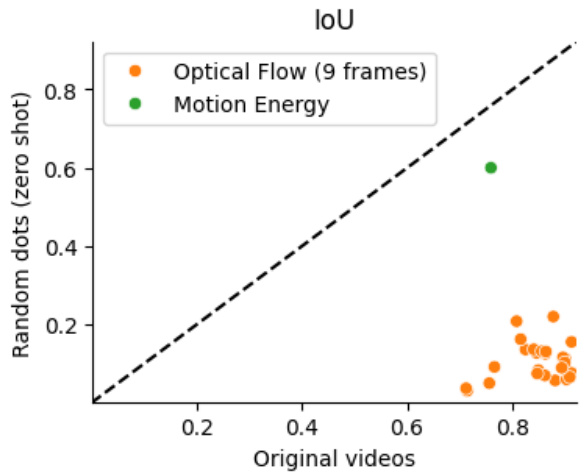

This figure compares the performance of multi-frame optical flow models and the motion energy model on both original videos and their corresponding random dot versions. The x-axis represents the Intersection over Union (IoU) score achieved on the original videos, and the y-axis represents the IoU score on the zero-shot random dot stimuli. Each point represents a different model. The diagonal dashed line indicates the ideal scenario where performance on the original and random dot videos are equal. The plot shows that motion energy significantly outperforms optical flow models in generalizing to random dot stimuli (zero-shot), which is indicated by the significant vertical displacement of the motion energy model point from the diagonal. The optical flow models mostly cluster near the diagonal, demonstrating their limited ability to generalize to unseen texture.

This figure shows a comparison of human and model performance in a shape identification task using random dot stimuli. The left panel displays an example stimulus, highlighting the informative dots (those belonging to only one of the target or distractor shapes). The right panel shows psychometric curves, plotting the proportion of correct responses against the number of informative dots per frame. The curves demonstrate that the motion energy model’s performance closely matches human performance, particularly for medium difficulty levels, while optical flow models significantly underperform.

This figure compares the performance of different motion estimation models (optical flow and motion energy) on a figure-ground segmentation task. It shows example predictions for the original videos (left) and corresponding random dot stimuli (right). The motion pattern is the same for both original video and the random dot stimuli. While optical flow models show high accuracy for original videos but fail to generalize to random dots, the motion energy model demonstrates better generalization. The motion energy model’s activations maintain a similar pattern for both original and random dot stimuli, enabling it to accurately segment the foreground object in both cases.

This figure compares the performance of various motion estimation models on both original videos and their corresponding random dot stimuli. It shows that while optical flow methods perform well on original videos, they struggle to generalize to random dot stimuli with the same motion patterns. In contrast, the motion energy model demonstrates good generalization to random dot stimuli.

More on tables

This table presents a comparison of different motion estimation models’ performance on two types of video data: original videos and corresponding random dot stimuli. The random dot stimuli are generated to preserve the motion patterns of the original videos while making the appearance cues uninformative. The table shows the Intersection over Union (IoU) and F-Score metrics for each model on both datasets, allowing assessment of how well each model generalizes to the zero-shot scenario. The models are grouped by type (optical flow vs. motion energy) and ordered within each group by their performance on the random dot stimuli, highlighting the best-performing model in this scenario.

This table presents a comparison of different motion estimation models’ performance on two types of video data: original videos and their corresponding random dot stimuli. The random dot stimuli preserve the motion information from the original videos but remove appearance-based cues. The table shows the Intersection over Union (IoU) and F-score for each model on both datasets, revealing the models’ ability to generalize zero-shot to motion-only perception. The models are grouped by their architecture and ordered by their performance on the random dot stimuli.

This table presents a comparison of various motion estimation models (including a neuroscience-inspired motion energy model and several state-of-the-art optical flow models) on two tasks: segmenting moving objects in standard videos and segmenting objects in videos where the appearance is replaced with random dots but the motion patterns are preserved. The table shows that the motion energy model significantly outperforms other models when tested on random-dot stimuli, indicating its ability to generalize to novel visual patterns based on motion information.

This table presents a comparison of different motion estimation models’ performance on both original videos and their corresponding random dot versions. The models are categorized by type (e.g., optical flow, motion energy), training dataset, and the resulting Intersection over Union (IoU) and F-score metrics for each. The table highlights how well each method generalizes to the zero-shot scenario of random dot stimuli, which lack appearance cues, demonstrating which models are capable of human-like generalization based on motion alone.

Full paper#