↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many computer vision and natural language processing tasks rely on effective feature extraction from pre-trained models. However, creating these features often requires extensive feature engineering or additional training, which can be time-consuming and computationally expensive. This paper introduces FUNGI, a simple method that enhances existing model features by incorporating self-supervised gradients without any further training.

FUNGI works by calculating gradients from self-supervised loss functions for each input, projecting these gradients into a lower dimension, and then concatenating them with the model’s output embedding. Evaluated across numerous vision, natural language, and audio datasets, FUNGI consistently improved k-nearest neighbor classification, clustering, and retrieval-based in-context scene understanding. This method is broadly applicable and data efficient, offering a significant improvement for researchers working with pre-trained models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is significant because it presents a novel and efficient method to improve deep learning model representations without any further training. It offers a simple yet effective technique that can be easily incorporated into existing workflows, leading to improved performance across various tasks. This approach is particularly relevant in resource-constrained settings or when retraining models is impractical. The findings open up new avenues for exploring the use of self-supervised gradients for improving model representations across different modalities and applications.

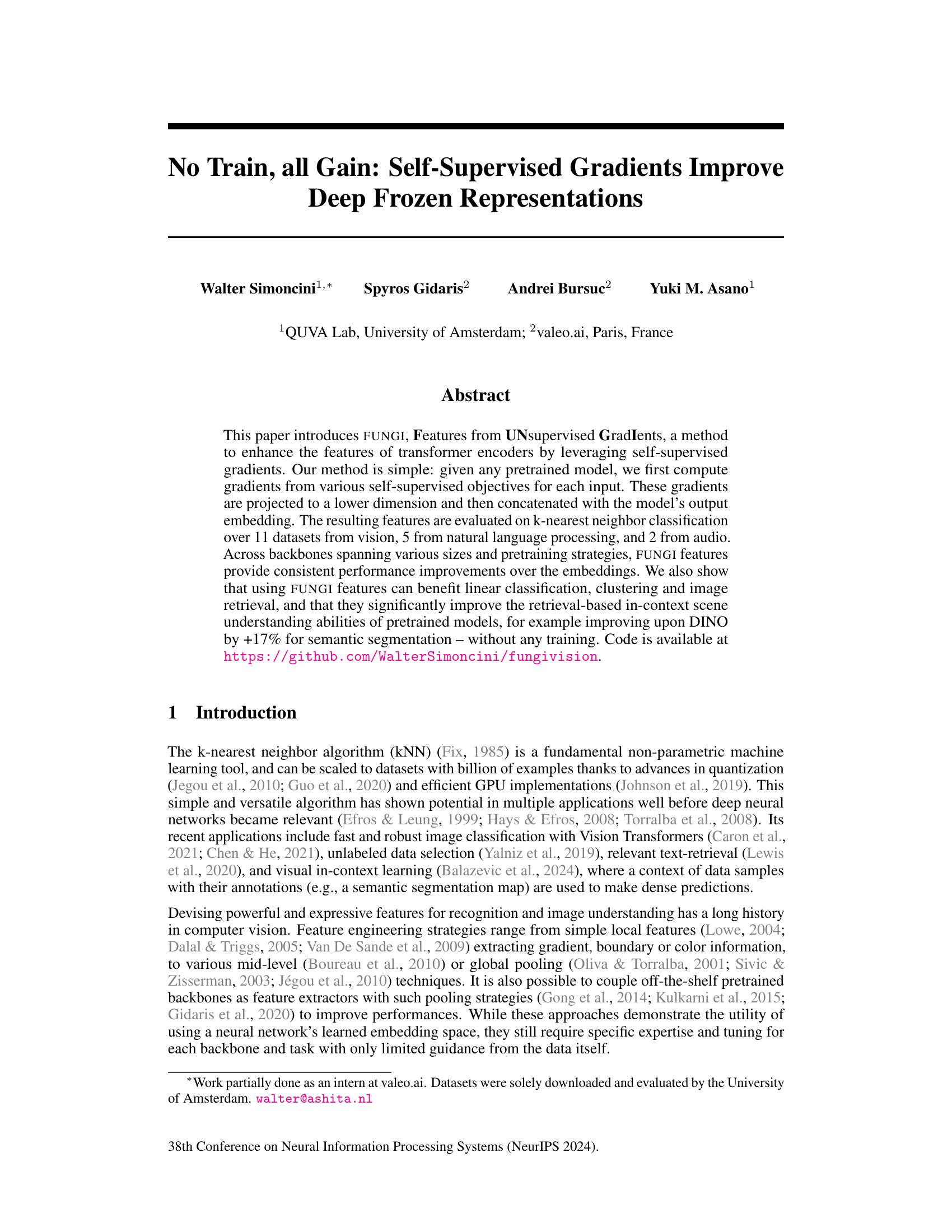

Visual Insights#

This figure illustrates the FUNGI method. It shows how gradients from various self-supervised losses are computed for a given input from a pretrained backbone. These gradients are projected to a lower dimension and concatenated with the model’s output embedding. The resulting gradient-enhanced features are then used to build a k-nearest neighbor index, which is used for classification or retrieval.

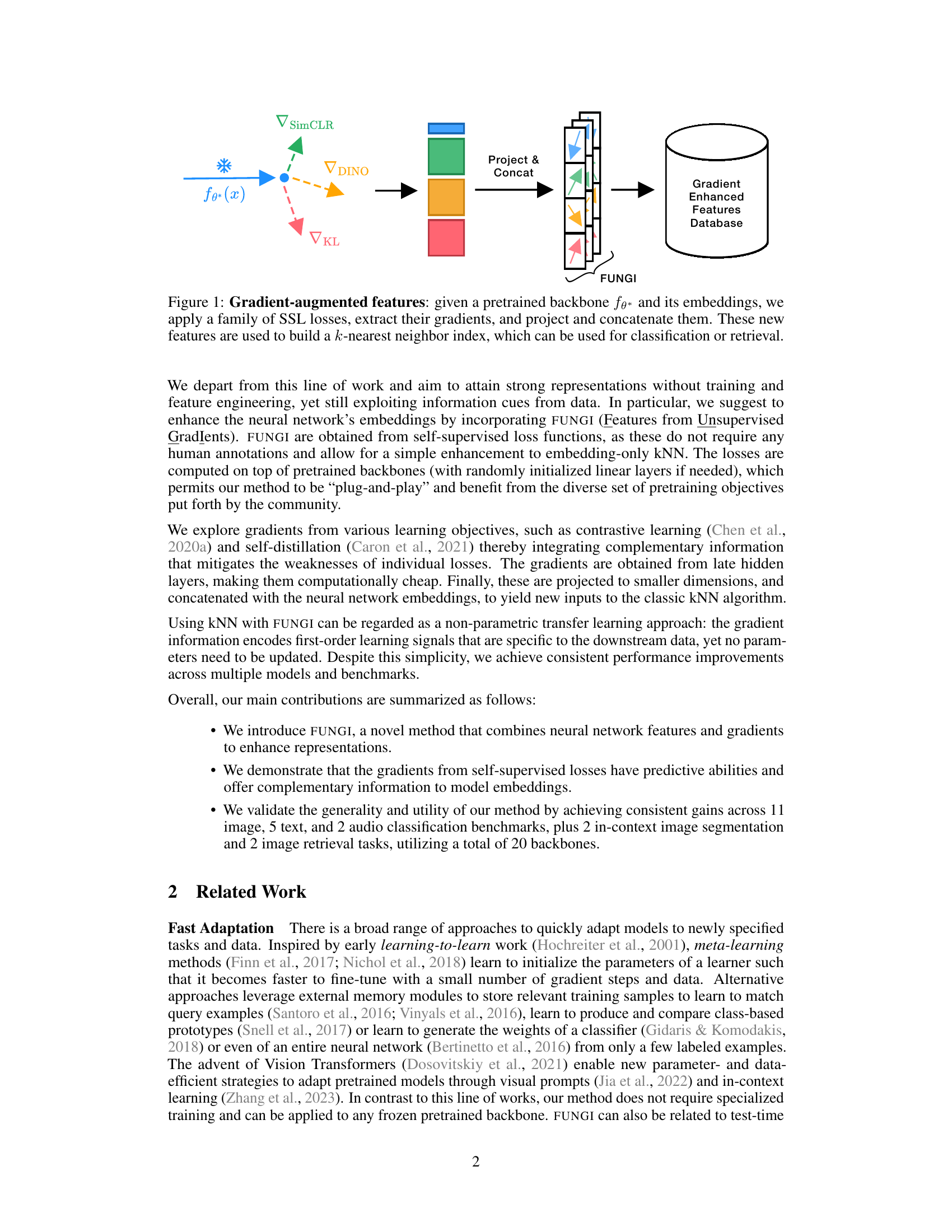

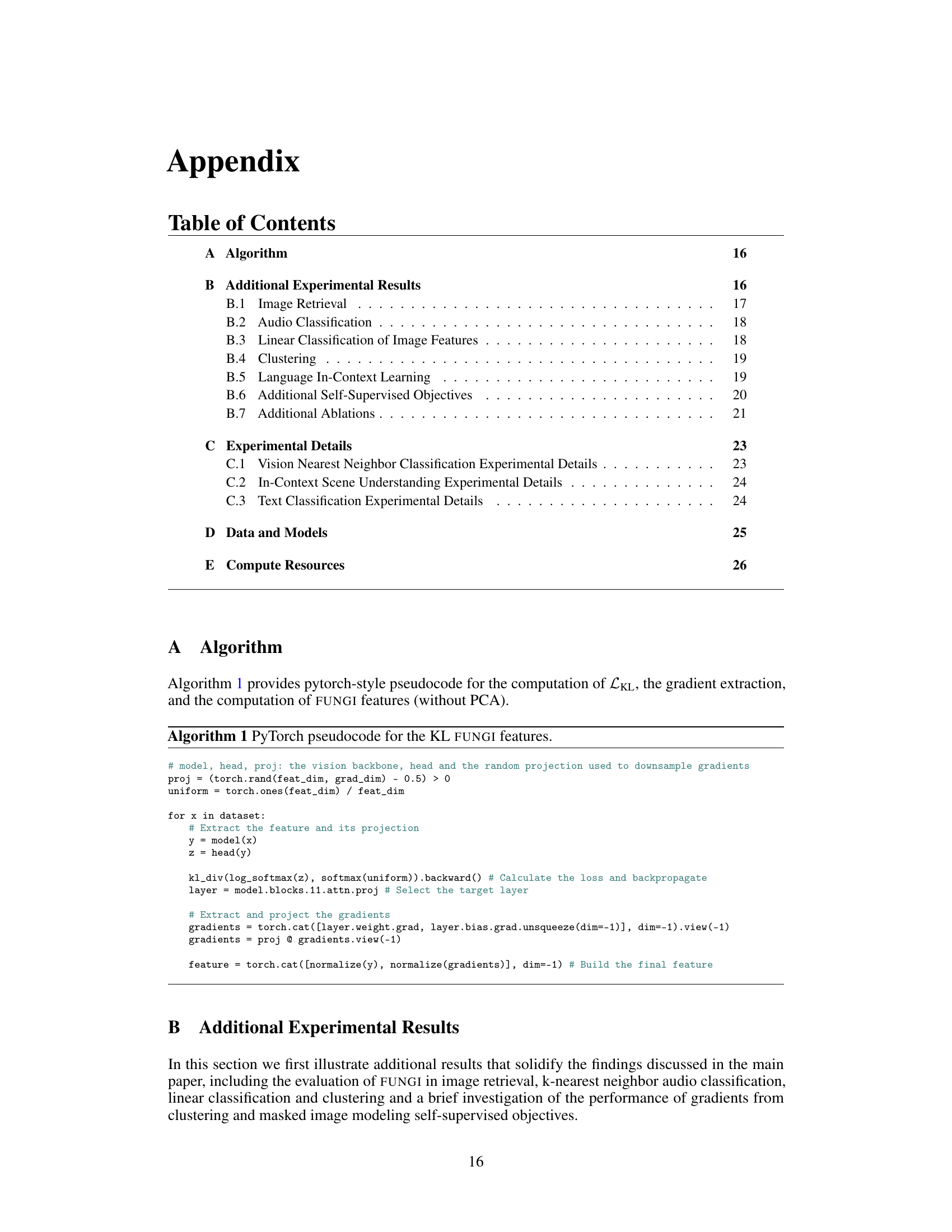

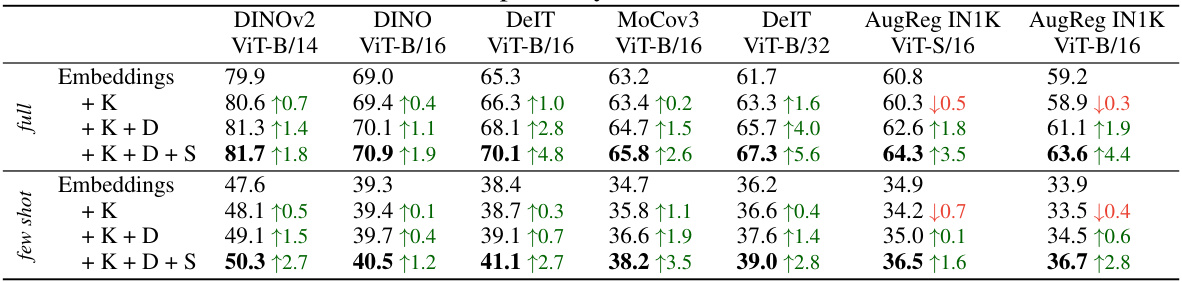

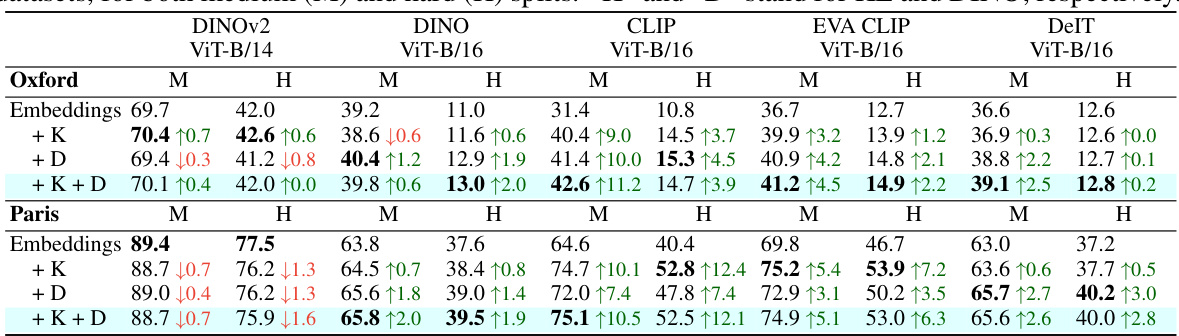

This table presents the kNN classification accuracy results on 11 datasets using two different vision transformer backbones pre-trained on ImageNet-1K and ImageNet-21K. It compares the performance of using only the model’s embeddings as features versus using the FUNGI features (embeddings combined with self-supervised gradients). The results are shown separately for both the ‘full dataset’ and a ‘5-shot’ scenario. The table aims to demonstrate that the FUNGI features consistently improve the classification accuracy across multiple datasets and pre-training strategies.

In-depth insights#

FUNGI: Gradient Fusion#

The concept of “FUNGI: Gradient Fusion” suggests a novel approach to enhance feature representations by combining model embeddings with self-supervised gradients. This fusion aims to leverage the complementary information present in both sources. Embeddings capture high-level semantic information, while gradients provide a signal indicating how the model’s internal representation changes in response to specific input features. Fusing them could create a more robust, discriminative feature space, beneficial for tasks like image retrieval and classification. The effectiveness hinges on the careful selection and processing of gradients, including choosing the right self-supervised loss functions and addressing the potential for high dimensionality and noise within the gradient data. The use of techniques like dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA) and normalization is key for practical applicability. Overall, the “FUNGI: Gradient Fusion” approach presents an intriguing strategy to boost performance in deep learning models without requiring additional training, potentially improving data efficiency and generalization ability.

Self-Supervised Gradients#

The concept of “Self-Supervised Gradients” presents a novel approach to enhancing feature representations in deep learning models. It leverages the gradients computed from self-supervised learning objectives, avoiding the need for labeled data during the feature extraction phase. These gradients, rich with information about the model’s internal state and its relation to the input data, are projected to a lower dimension and concatenated with the model’s original output embeddings. This augmentation process produces more expressive features which improve performance in downstream tasks such as k-nearest neighbor classification and retrieval. The method is particularly attractive for its simplicity and adaptability, working effectively across diverse model architectures and pretraining strategies, thereby offering a potential improvement for a wide variety of applications. However, further investigation is needed into gradient characteristics for different self-supervised objectives. Certain losses show promise while others may hinder performance, emphasizing the need for a deeper understanding of how gradients encode task-relevant information. Overall, Self-Supervised Gradients offers a promising direction for improving feature learning and representation, specifically in low-data regimes, while offering a plug-and-play enhancement to pre-trained models.

KNN Classification Boost#

A hypothetical ‘KNN Classification Boost’ section would likely detail how the integration of self-supervised gradients enhances k-Nearest Neighbor (kNN) classification. The core argument would center on the complementary information provided by these gradients, augmenting the standard feature embeddings. The paper would probably present empirical evidence demonstrating that this gradient augmentation leads to consistent accuracy improvements across diverse datasets and neural network architectures. Key aspects of the methodology, including gradient extraction techniques, dimensionality reduction strategies, and the feature concatenation process, would be clearly explained. Furthermore, an analysis of the generalizability and robustness of the approach across different model sizes and pretraining schemes would likely be included. The discussion might also address the computational overhead introduced by the gradient calculations and potential limitations of the approach in low-data scenarios. Ultimately, this section would aim to establish the effectiveness of the proposed ‘boost’ in improving the performance of kNN classifiers for various tasks.

In-Context Improvements#

The concept of “In-Context Improvements” in a research paper likely refers to advancements achieved within the context of a specific model or task, without requiring additional training. This is crucial in scenarios where retraining is expensive, time-consuming, or even impossible. The improvements might stem from various techniques such as efficient feature extraction, knowledge transfer, or algorithmic enhancements. A thoughtful analysis would dissect the specific methods used to achieve these in-context gains, quantifying their impact and comparing their performance against alternatives involving retraining. Benchmarking and comparison with traditional fine-tuning methods are key to establish the efficacy and potential of this in-context approach. Furthermore, it is important to consider the generalizability of the improvements to new and unseen data, as well as any limitations or specific constraints associated with this approach. The overall value lies in demonstrating that significant performance improvements are possible within the existing model context, thus presenting a more practical and cost-effective solution to adapting AI models to new tasks.

Future of FUNGI#

The “Future of FUNGI” holds exciting potential. Improved efficiency is key; exploring alternative gradient calculation methods and projection techniques could significantly reduce computational costs, making FUNGI applicable to larger models and datasets. Expanding beyond image data is another avenue; FUNGI’s core principle—combining gradients with embeddings—is adaptable to diverse modalities like video, text, and multi-modal data. Integration with existing techniques should be investigated; combining FUNGI with other data-efficient methods could lead to even greater performance gains. Furthermore, theoretical understanding of FUNGI’s effectiveness needs further exploration, potentially uncovering deeper insights and guiding future improvements. Finally, evaluating the robustness of FUNGI in real-world scenarios with noisy or incomplete data is crucial for demonstrating its practical value. Addressing these areas will pave the way for FUNGI’s broader adoption and enhance its impact on various machine learning tasks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

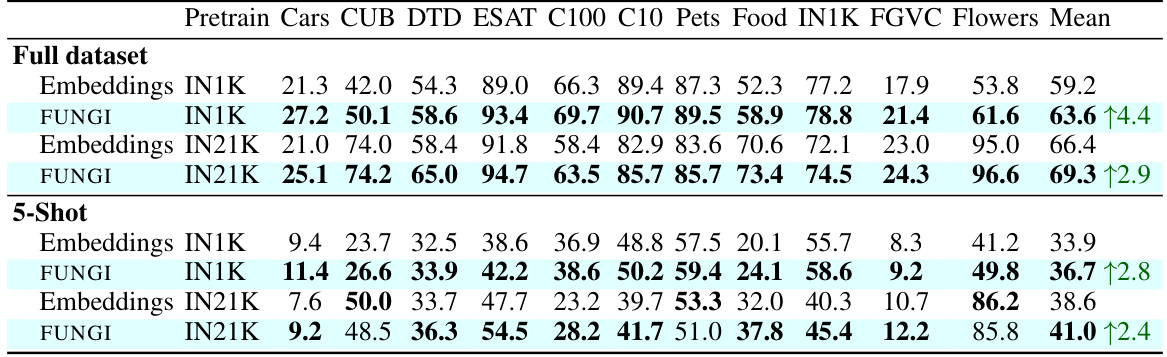

This figure demonstrates that combining embeddings with gradients from different self-supervised learning objectives leads to significantly improved performance in k-nearest neighbor (kNN) classification. The top part shows a pairwise Centered Kernel Alignment (CKA) similarity matrix, which measures the similarity between different feature sets (embeddings and gradients from SimCLR, DINO, and KL-divergence losses). The heatmap indicates that the features are quite different and therefore complementary. The bottom part displays the kNN accuracy achieved by using different combinations of these features. It illustrates that combining embeddings with gradients consistently results in higher accuracy than using embeddings alone.

This figure compares the per-class kNN accuracy improvement of using gradients from different self-supervised learning objectives (KL, DINO, SimCLR) against using only the model embeddings. The x-axis represents the class index, and the y-axis represents the change in accuracy. Positive values indicate an improvement in accuracy when using gradients compared to embeddings, and negative values indicate a decrease in accuracy. The plot visually demonstrates that different self-supervised objectives result in gradients that contain different information and affect the accuracy of different classes differently. This highlights the potential benefit of combining gradients from various objectives, as they seem to provide complementary information.

This figure illustrates the process of extracting gradients from a pretrained model using the SimCLR loss. First, an input image is patchified (divided into smaller patches). These patches are fed through the pretrained backbone (f) to generate latent representations. A projection head (h) further processes these representations. The SimCLR loss is then computed by maximizing similarity between patches from the same image and minimizing similarity between patches from different images (a ‘fixed negative batch’ is used for comparison). Backpropagation calculates the gradients with respect to the weights and biases of a specific layer within the backbone. Finally, these gradients are projected down to the same dimensionality as the model’s output embeddings.

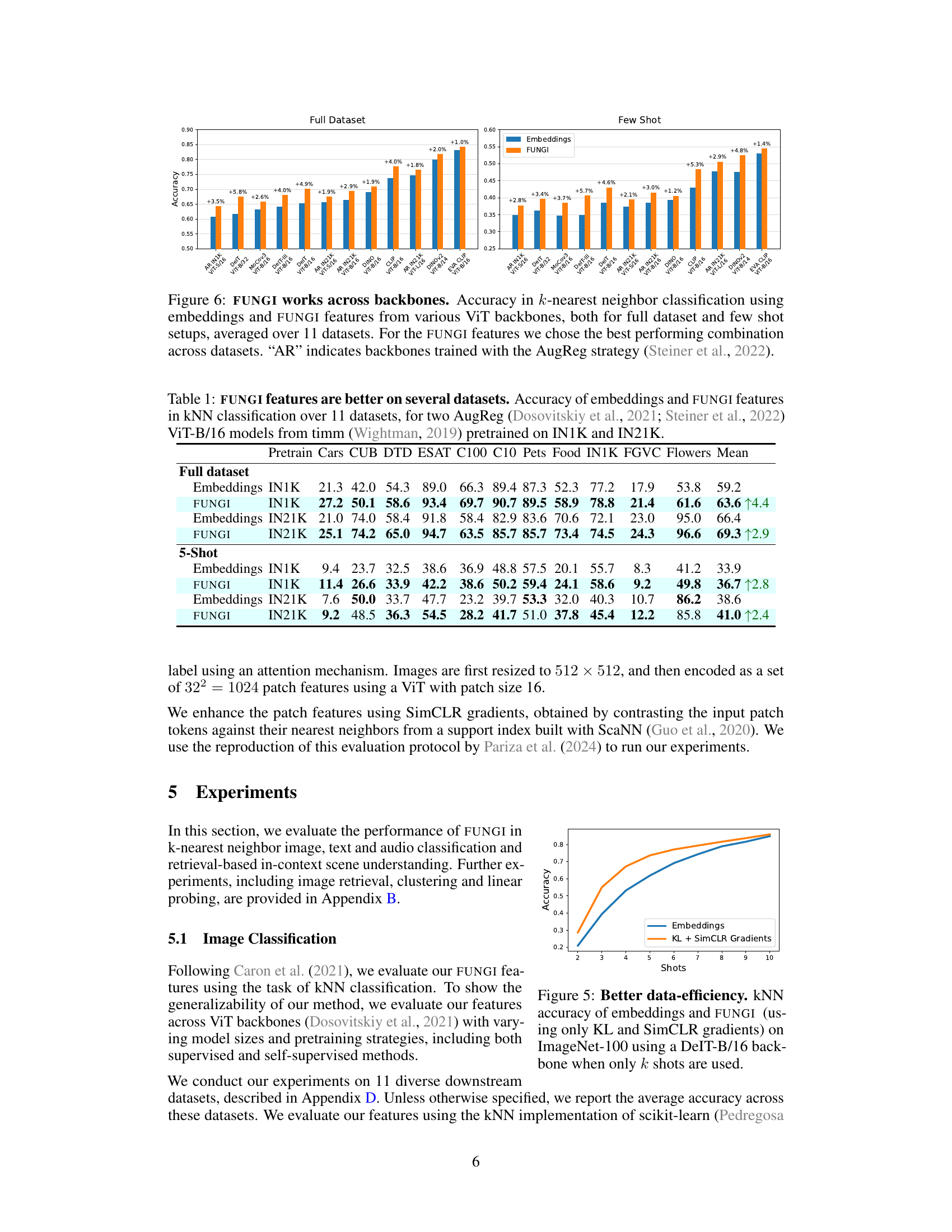

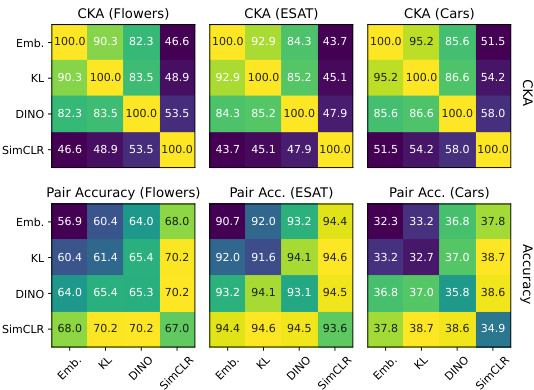

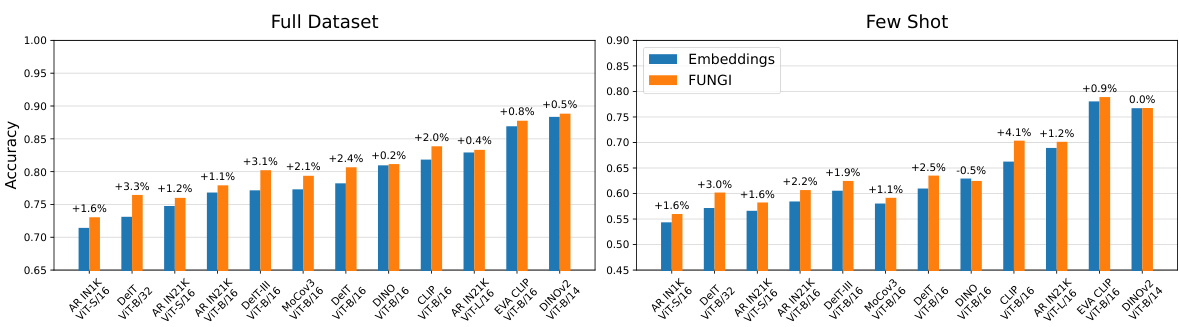

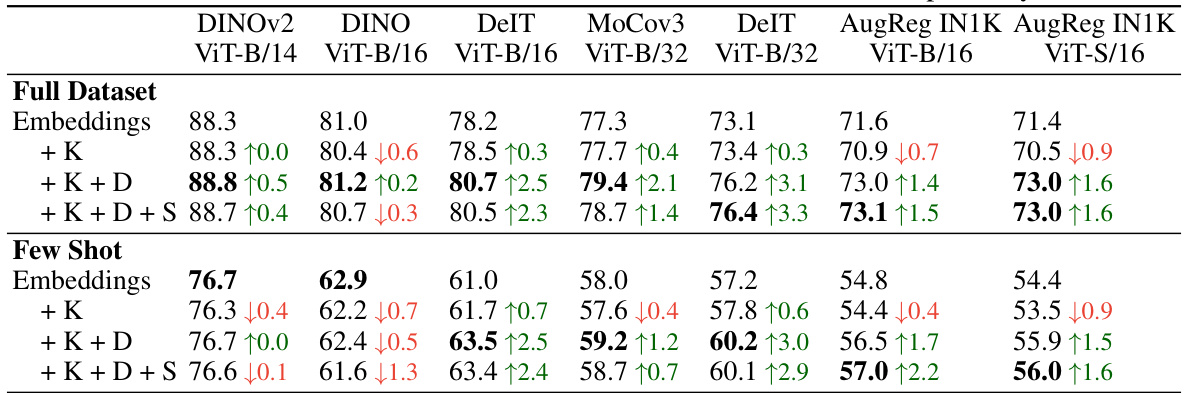

This figure demonstrates the consistent performance improvement of FUNGI across various Vision Transformer (ViT) backbones. The results are shown for both full datasets and few-shot learning scenarios (averaged over 11 datasets). The best-performing combination of FUNGI features is used for each backbone. The ‘AR’ designation indicates backbones that were trained with the AugReg strategy.

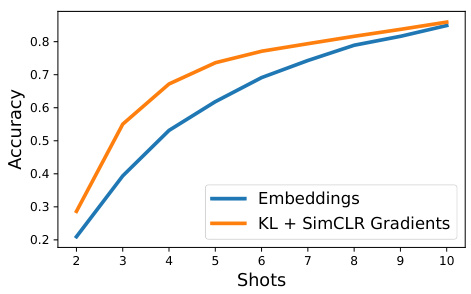

This figure shows the k-Nearest Neighbor accuracy on the ImageNet-100 dataset using a DeIT-B/16 backbone for different numbers of training shots (few-shot learning). It compares the accuracy achieved using only the model embeddings against the accuracy achieved when augmenting those embeddings with features derived from KL and SimCLR gradients (FUNGI). The plot demonstrates that the FUNGI features improve accuracy, particularly in low-data scenarios (few-shot learning).

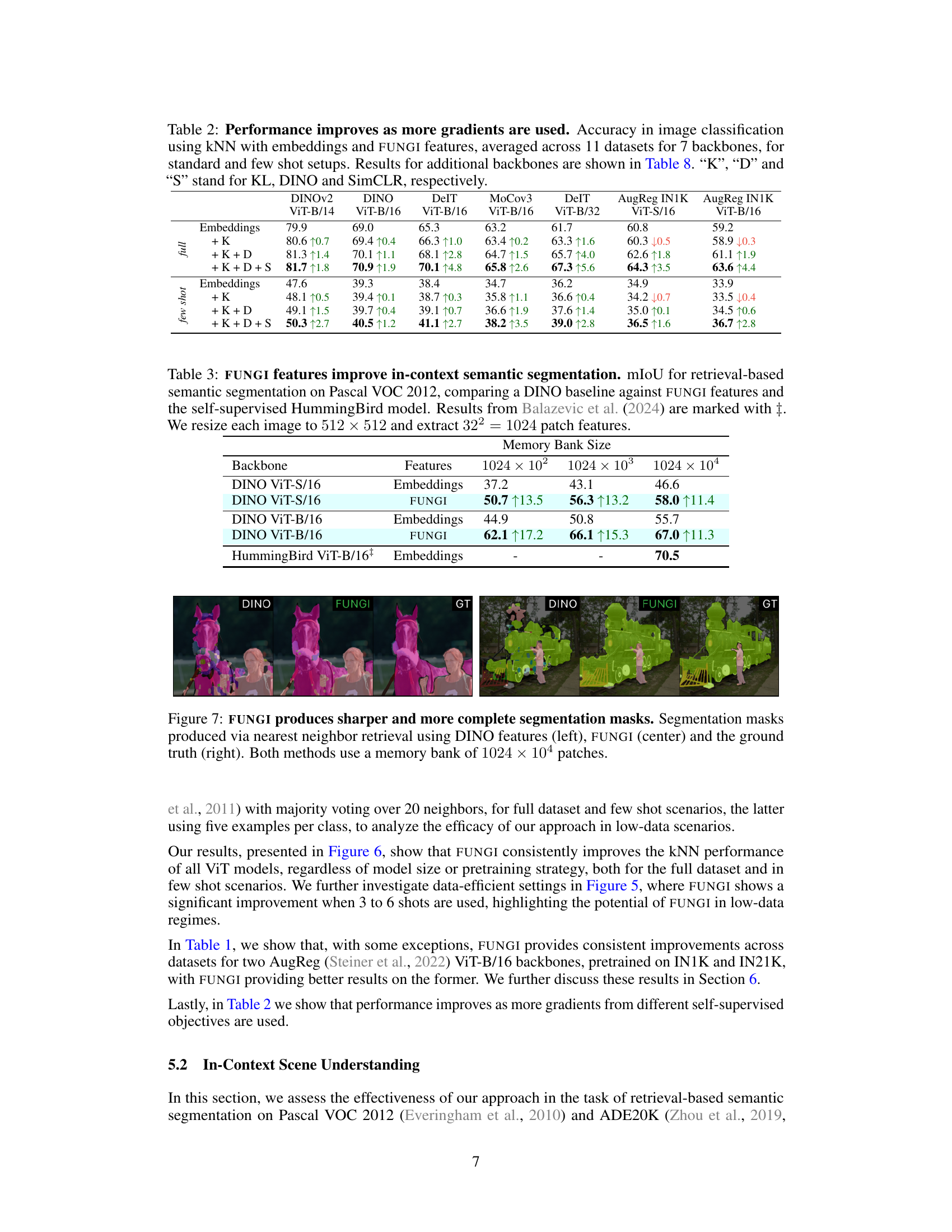

This figure shows a comparison of semantic segmentation results obtained using DINO features and FUNGI features. The leftmost column displays results from DINO, the middle column shows the improvement gained by using FUNGI features, and the rightmost column shows the ground truth segmentation. Both methods utilize a large memory bank (1024 x 104 patches) for nearest neighbor retrieval to generate these results. The images visually demonstrate that FUNGI produces better, more complete, and sharper segmentation masks than DINO.

This figure displays the accuracy results of using gradients from different layers of a DeIT ViT-B/16 model for k-nearest neighbor classification on the ImageNet-100 dataset. Three different self-supervised learning objectives (KL, DINO, and SimCLR) were used, and gradients from four layers within each transformer block (attn.qkv, attn.proj, mlp.fc1, and mlp.fc2) were evaluated. The results demonstrate that gradients from deeper layers generally produce more accurate features, indicating that these layers contain more predictive information. The cyan-colored lines highlight the accuracy obtained when using gradients from the last layers (default setup), showing they’re competitive with the other layer choices.

This figure compares the performance of k-Nearest Neighbor (kNN) classification using two different feature sets: embeddings from various Vision Transformer (ViT) backbones and FUNGI features (which augment the embeddings with gradients from self-supervised losses). The results are averaged across 11 datasets and are shown for both full datasets and low-data (‘few-shot’) scenarios. The figure demonstrates the consistent performance improvement achieved by using FUNGI features across a range of ViT architectures, pretrained with different strategies, including those using the AugReg strategy.

This figure compares the performance of different self-supervised learning objectives in predicting the class of an image using its gradients as features. The k-nearest neighbor classification accuracy on ImageNet-102 is shown for six different objectives: DeepCluster, DINO, KL, iBOT (No MIM), iBOT (MIM), and SimCLR. The results indicate that not all self-supervised objectives produce equally effective gradients for this task, highlighting the impact of objective selection on gradient quality and downstream classification accuracy. MIM stands for Masked Image Modeling.

This figure shows the scalability of FUNGI across different sizes of Vision Transformers (ViTs). The x-axis represents the ViT size (ViT-S, ViT-B, ViT-L), and the y-axis shows the accuracy achieved using both embeddings alone and FUNGI-enhanced features. The results demonstrate consistent improvements in accuracy with FUNGI across all ViT sizes, suggesting the method’s generalizability and effectiveness regardless of model capacity.

This figure shows two plots. The left plot shows the relationship between the number of patches used in the SimCLR loss and the resulting accuracy on the Flowers102 dataset. The accuracy increases as the number of patches increases, but the rate of increase slows down. The right plot shows the relationship between the number of patches and the speed at which images can be processed. The speed decreases as the number of patches increases. Both plots demonstrate a trade-off between accuracy and processing speed when using the SimCLR loss. This highlights the importance of considering computational efficiency alongside accuracy when tuning hyperparameters in self-supervised learning.

More on tables

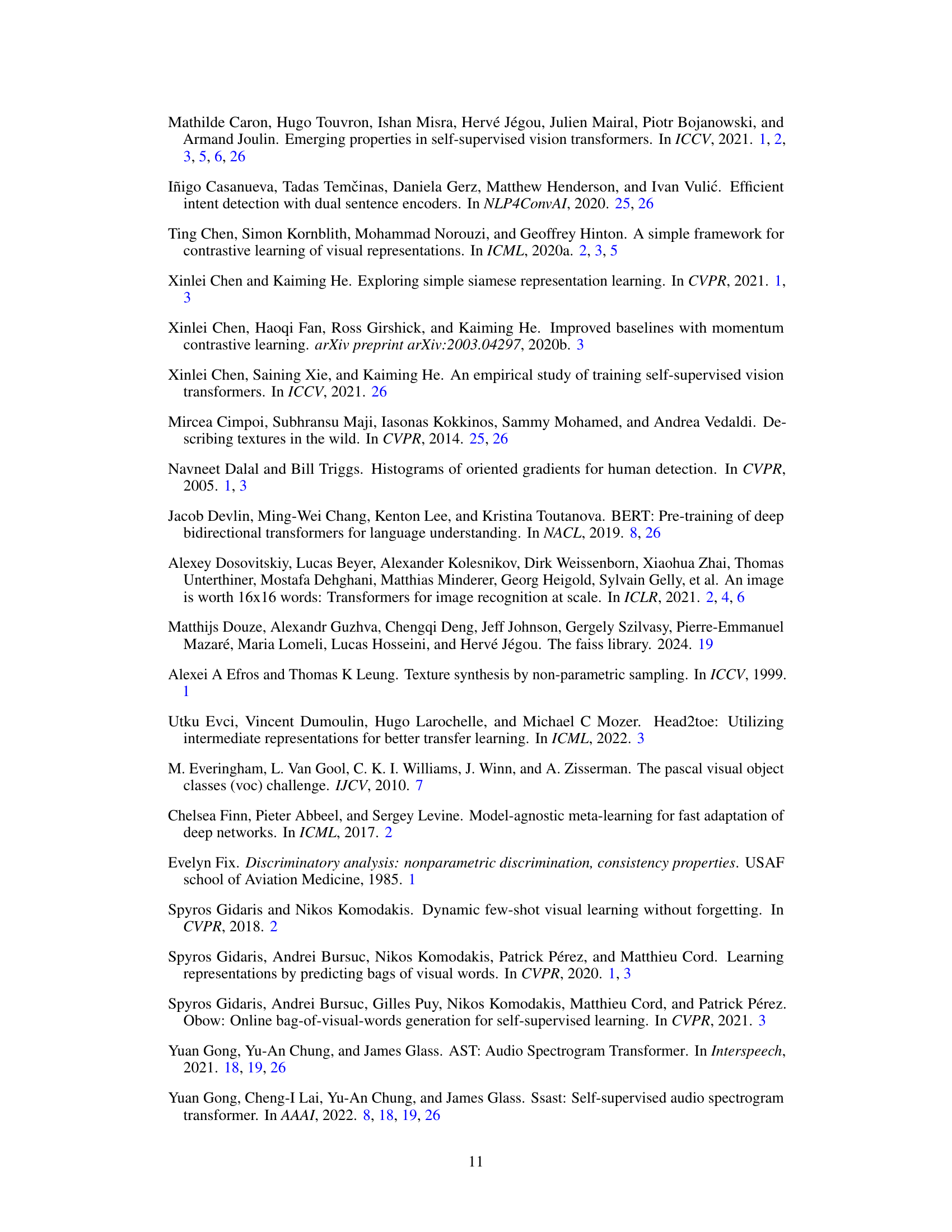

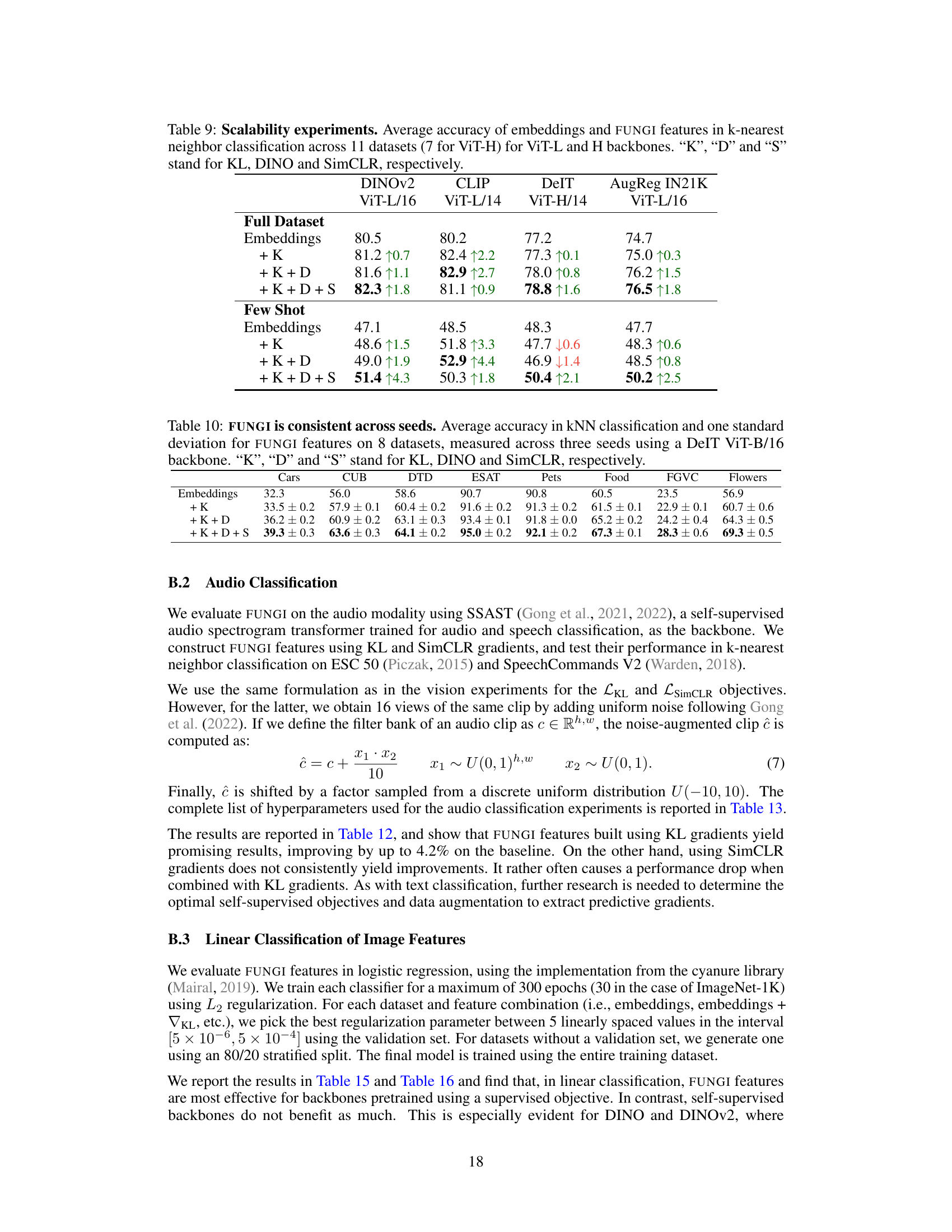

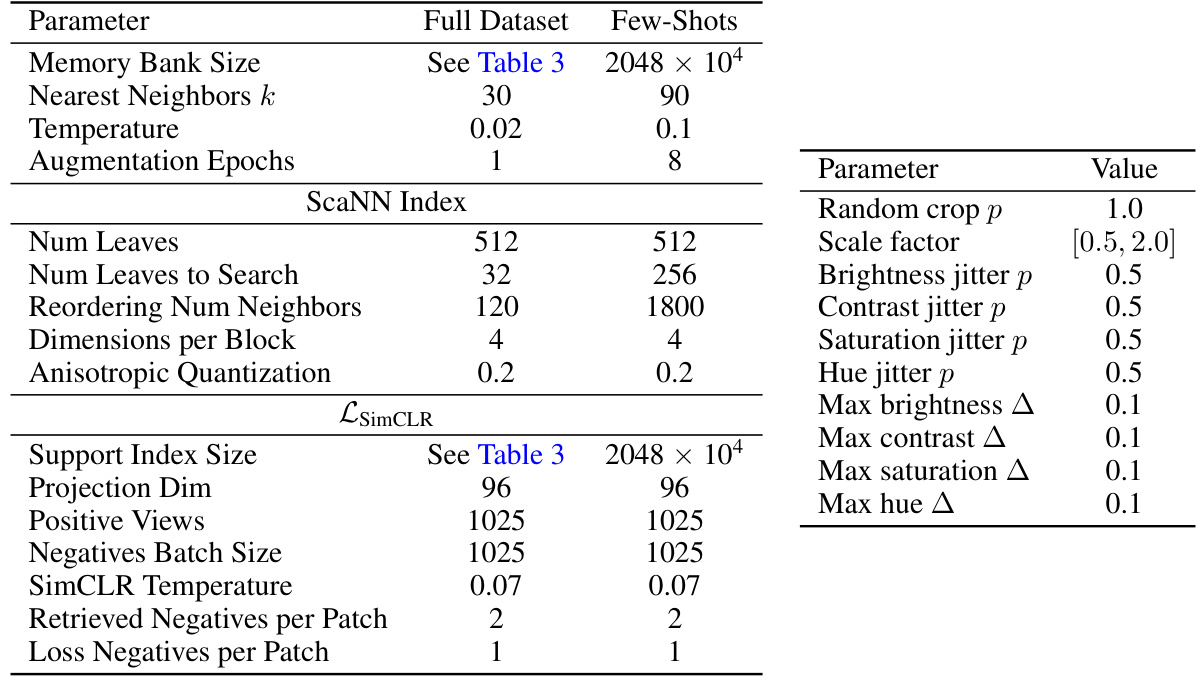

This table shows the performance of image classification using k-nearest neighbor with embeddings and FUNGI features. The results are averaged across 11 datasets and 7 different backbones. It compares the performance with different combinations of gradients from three self-supervised learning objectives (KL, DINO, and SimCLR) for both standard and few-shot settings. Additional backbones’ results are presented in Table 8.

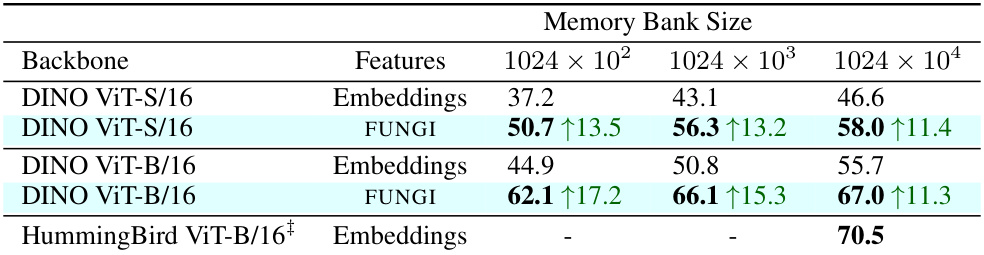

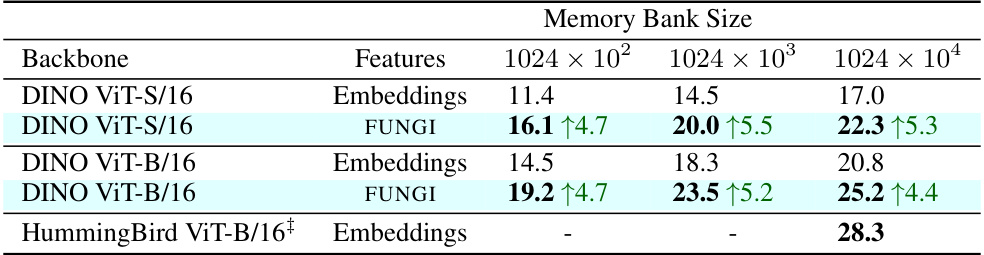

This table compares the performance of different feature extraction methods (Embeddings, FUNGI, HummingBird) for the task of in-context semantic segmentation on the ADE20K dataset. The results are presented for three different memory bank sizes (1024x102, 1024x103, 1024x104). The improvement in mIoU (mean Intersection over Union) using FUNGI features over DINO embeddings is highlighted. The results are also compared to the state-of-the-art HummingBird model.

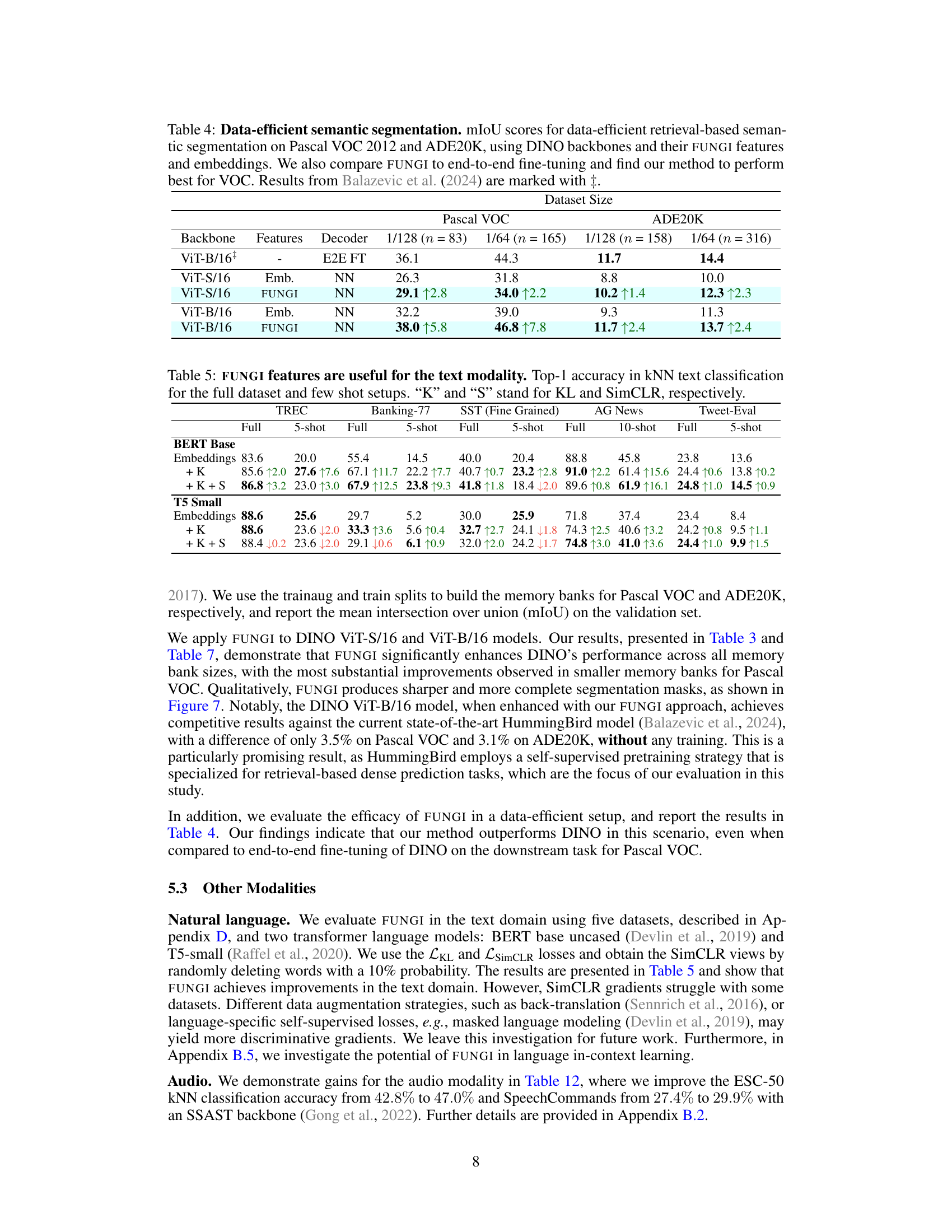

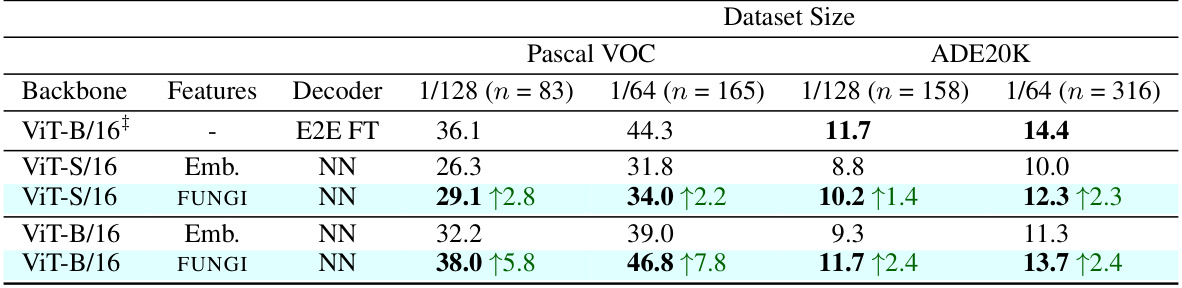

This table presents the results of data-efficient semantic segmentation on the Pascal VOC 2012 and ADE20K datasets. It compares the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) scores achieved using different methods: end-to-end fine-tuning (E2E FT), using only embeddings (Emb.), and using the proposed FUNGI features. The table shows results for various dataset sizes and DINO backbones (ViT-S/16 and ViT-B/16). The results highlight that FUNGI consistently outperforms using embeddings alone and is competitive with or even surpasses end-to-end fine-tuning, particularly for Pascal VOC.

This table presents the accuracy achieved by kNN classification using both standard embeddings and FUNGI features. The results are broken down by dataset and are shown for two different pre-trained models (IN1K and IN21K), demonstrating the consistent improvement of FUNGI across various datasets.

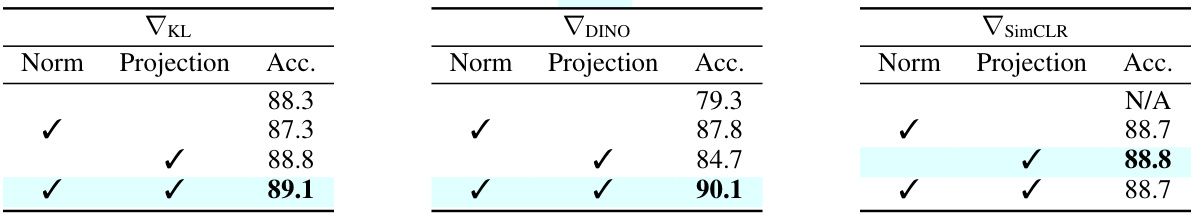

This table presents an ablation study on the impact of different projection head configurations (with or without L2 normalization) on the accuracy of gradients obtained using three self-supervised losses (KL, DINO, and SimCLR) for ImageNet-100. The results show that the best configuration consistently yields the highest accuracy.

This table presents the results of in-context semantic segmentation on the ADE20K dataset. It compares the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) scores achieved by using DINO embeddings, FUNGI features (which combine DINO embeddings with gradients from self-supervised losses), and the HummingBird model (a state-of-the-art method for this task). The comparison is done across three different memory bank sizes (1024 x 102, 1024 x 103, 1024 x 104). The results show that FUNGI consistently improves upon the baseline DINO method, and even achieves comparable performance to the HummingBird model.

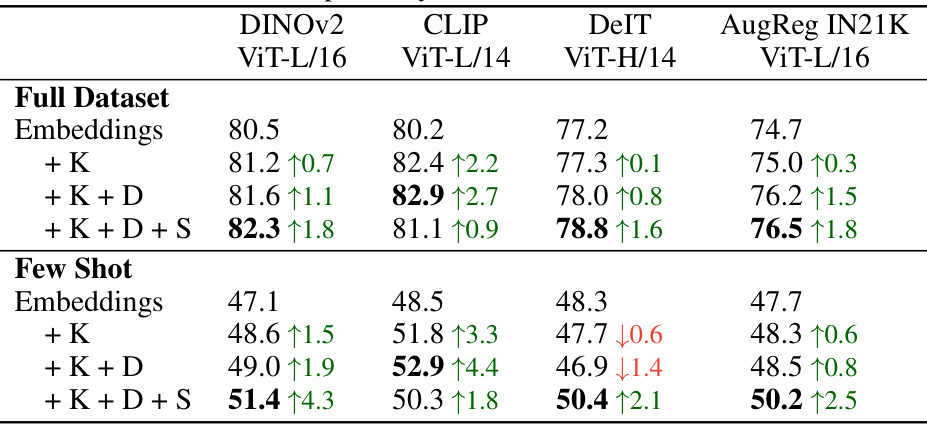

This table shows the average accuracy of embeddings and FUNGI features in k-nearest neighbor classification across 11 datasets for several different backbones. The backbones included are CLIP, AugReg, DeIT III, and MAE. It also indicates the performance when using only KL, KL+DINO, and KL+DINO+SimCLR gradients. The results are shown for both full dataset and few-shot settings.

This table presents the accuracy of k-nearest neighbor classification using both the original model embeddings and the enhanced FUNGI features. Results are shown for various Vision Transformer (ViT) backbones, across different sizes and training strategies. Both full-dataset and few-shot settings are included, averaged across 11 diverse datasets. The ‘AR’ designation indicates backbones trained using the AugReg strategy.

This table presents the accuracy of k-Nearest Neighbor (kNN) classification on eleven datasets using two different feature sets: embeddings from pre-trained models and FUNGI features (which are embeddings augmented with gradients). Two different pre-trained models are used, one trained on ImageNet-1K and the other on ImageNet-21K. The table shows that using FUNGI features consistently improves classification accuracy over embeddings alone, demonstrating the effectiveness of the FUNGI method.

This table compares the performance of embeddings and FUNGI features in k-Nearest Neighbor (kNN) classification across 11 datasets. Two different Vision Transformer (ViT) models, pretrained on ImageNet-1K (IN1K) and ImageNet-21K (IN21K), are used. The results show that FUNGI features generally improve the accuracy compared to using embeddings alone, indicating that incorporating gradients from self-supervised learning enhances the model’s representations.

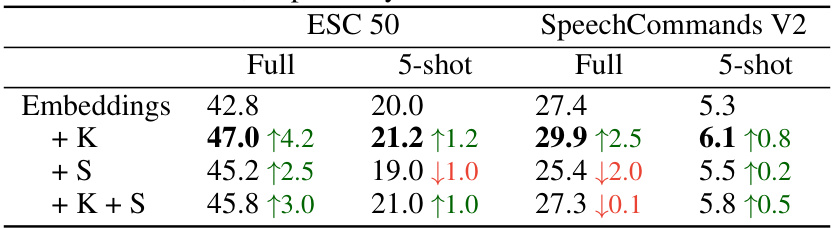

This table presents the results of the k-nearest neighbor audio classification task using the SSAST backbone. It compares the top-1 accuracy of using just the embeddings with the results of adding features derived from the KL and SimCLR gradients (FUNGI features). The performance is shown for both the full dataset and a 5-shot scenario, indicating the method’s efficacy in low-data settings. The arrows in the table indicate whether the addition of gradients improved or decreased the accuracy.

This table shows the accuracy of image classification using k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) with different combinations of model embeddings and FUNGI features (features from unsupervised gradients). It compares the performance using only embeddings against using embeddings combined with gradients from one, two, or three different self-supervised learning objectives (KL, DINO, SimCLR). Results are averaged across 11 different datasets and are shown for 7 different vision transformer backbones. The table also shows results for ‘few-shot’ scenarios, using a limited number of training examples.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of embeddings and FUNGI features on 11 image datasets using two different pre-trained Vision Transformer models (ViT-B/16). The models were pre-trained using ImageNet-1K (IN1K) and ImageNet-21K (IN21K). For each dataset, it shows the accuracy achieved by k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) classification using both the original embeddings and the embeddings augmented with FUNGI features. The table highlights the improvements in kNN accuracy achieved by using FUNGI features over the original embeddings.

This table presents the accuracy of kNN classification using embeddings and FUNGI features on eleven datasets. Two different backbones, pretrained on ImageNet-1k and ImageNet-21k, are used. The table shows that FUNGI features consistently improve the accuracy compared to embeddings across a variety of datasets, indicating the method’s generalizability and effectiveness.

This table shows the performance of k-nearest neighbor image classification using embeddings and FUNGI features across 11 datasets. Results are provided for 7 different backbones (pre-trained models) and for both full datasets and few-shot scenarios (where only a small amount of labeled data is used). The table demonstrates that incorporating more gradients from different self-supervised learning objectives leads to improved accuracy, showcasing the effectiveness of the FUNGI method.

This table presents the average accuracy results across 11 datasets for different backbones (CLIP, EVA-CLIP, AugReg, DeIT III, and MAE) using k-nearest neighbor classification. It shows the performance of both embeddings alone and embeddings enhanced with FUNGI features derived from three self-supervised learning objectives (KL, DINO, SimCLR). The results are presented for both full datasets and few-shot scenarios.

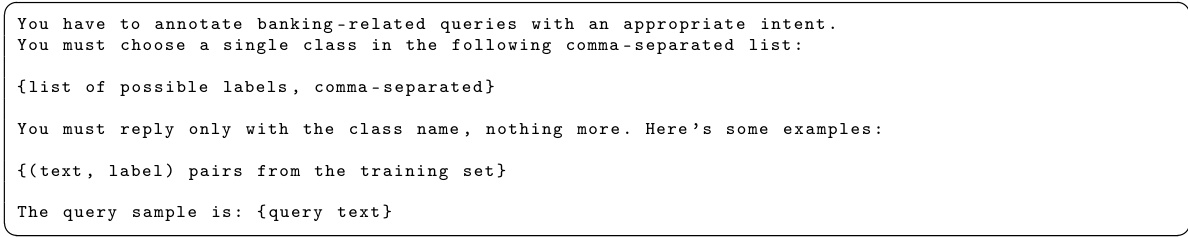

This table shows the results of in-context learning experiments using a GPT 40 mini model. It compares the classification accuracy when using either embeddings or FUNGI features (combining embeddings with gradients from KL and SimCLR losses). Two datasets, Banking-77 and SST, were used for evaluation.

This table presents ablation studies on the DINO gradients, comparing different head configurations (shared vs. independent) and data augmentation strategies (standard DINO vs. random crops) for ImageNet-100 classification. The results show that using independent heads and random crops significantly improves the accuracy of the DINO gradients.

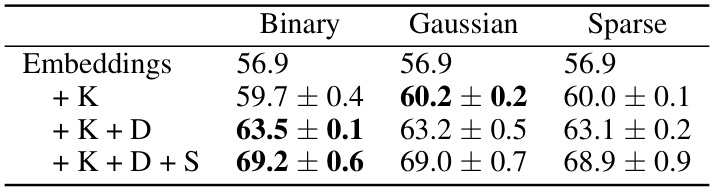

This table shows the results of an ablation study on the initialization method for random projections used in the FUNGI method. It compares three different initializations (Binary, Gaussian, and Sparse) on the Flowers102 dataset using a DeIT ViT-B/16 backbone. The table shows that the choice of initialization has a minimal impact on the final accuracy, with Gaussian showing slightly better results than binary and sparse.

This table displays the dimensionality reduction (PCA) impact on the performance of the k-NN image classification experiments. It shows the PCA dimensions used for different model architectures (ViT-S/16, ViT-B/16, ViT-L/16, BERT, T5, SSAST) and the resulting accuracy with and without PCA, averaged across 11 datasets. The results demonstrate that using PCA doesn’t negatively affect the accuracy and even shows a minor improvement in some cases.

This table compares the performance of different dimensionality reduction techniques on the Flowers102 dataset using a DeIT ViT-16/B backbone. The methods compared include no dimensionality reduction (No Reduction), Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and three types of random projections (Binary, Gaussian, and Sparse). The table shows the mean per-class accuracy and standard deviation for each method, with the embeddings and various combinations of gradients (K, D, and S). PCA achieves the highest accuracy.

This table compares the performance of different methods for in-context semantic segmentation on the ADE20K dataset. It shows the mean Intersection over Union (mIoU) scores for embeddings, FUNGI features, and the HummingBird model, across various memory bank sizes. The results demonstrate that FUNGI significantly improves upon the DINO baseline.

This table compares the performance of different methods on the ADE20K dataset for in-context semantic segmentation using retrieval-based approach. The methods compared are: DINO embeddings, FUNGI features using DINO embeddings, and the HummingBird model. The results demonstrate that FUNGI significantly enhances DINO’s performance across all memory bank sizes. Results are broken down by backbone (ViT-S/16 and ViT-B/16) and memory bank size (1024 x 102, 1024 x 103, 1024 x 104).

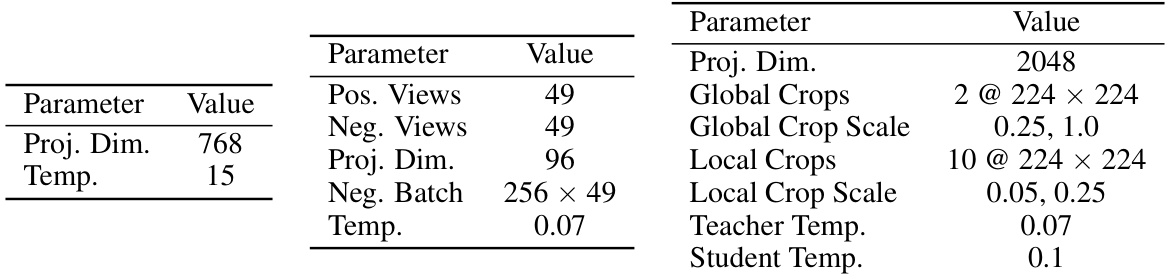

This table lists the hyperparameters used for the text modality experiments. Specifically, it shows the parameters used to extract gradients from text encoders for two different self-supervised learning objectives: KL Divergence and SimCLR. The parameters include the number of positive and negative views, projection dimensions, batch size, temperature, and the probability of word deletion for the SimCLR objective.

This table compares the performance of embeddings and FUNGI features in k-Nearest Neighbor classification across 11 datasets. It shows the accuracy for two different ViT-B/16 models pretrained on either ImageNet-1K or ImageNet-21K, demonstrating that FUNGI features consistently improve accuracy across various datasets.

This table presents the accuracy of image classification using k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) with different combinations of features (embeddings and gradients from KL, DINO and SimCLR losses). It compares the performance using only embeddings against results when one or more gradient types are added. The results are averaged across 11 datasets for 7 different backbones and are shown for both standard (full dataset) and few-shot (limited data) scenarios. Additional backbones are included in Table 8.

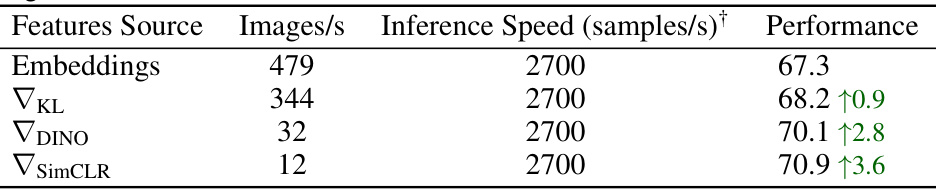

This table shows the speed of generating embeddings and gradients using an NVIDIA A100 GPU for a DeIT ViT-B/16 backbone. It also shows the impact on accuracy when using gradients from different self-supervised learning objectives in a k-nearest neighbor classification task across 11 image datasets. The table demonstrates that using gradients, although improving accuracy, significantly reduces the speed at which features can be generated.

Full paper#