↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Learning item rankings from pairwise comparisons is challenging when exhaustive comparisons are infeasible, especially with noisy, subjective assessments. Existing methods often struggle with sample efficiency and generalization to new items due to the absence of contextual information. This paper tackles these issues by proposing a novel algorithm called GURO that addresses limitations of non-contextual approaches and active preference learning baselines.

GURO employs a contextual logistic preference model, incorporating both aleatoric and epistemic uncertainties in comparisons, to guide active sampling. A hybrid model variant is also introduced to mitigate model misspecification. Experiments on multiple realistic ordering tasks using human annotators demonstrate GURO’s superiority in sample efficiency and generalization capabilities, outperforming non-contextual baselines and other active learning strategies. The findings provide a significant advancement for applications requiring efficient and accurate ordering of items based on limited pairwise comparisons.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on active preference learning and ranking problems, particularly in scenarios with contextual information and noisy comparisons. It offers a novel approach that significantly enhances sample efficiency and generalization, addressing limitations of existing methods. The theoretical framework and empirical results provide valuable insights and guidelines for developing more efficient and robust ranking algorithms.

Visual Insights#

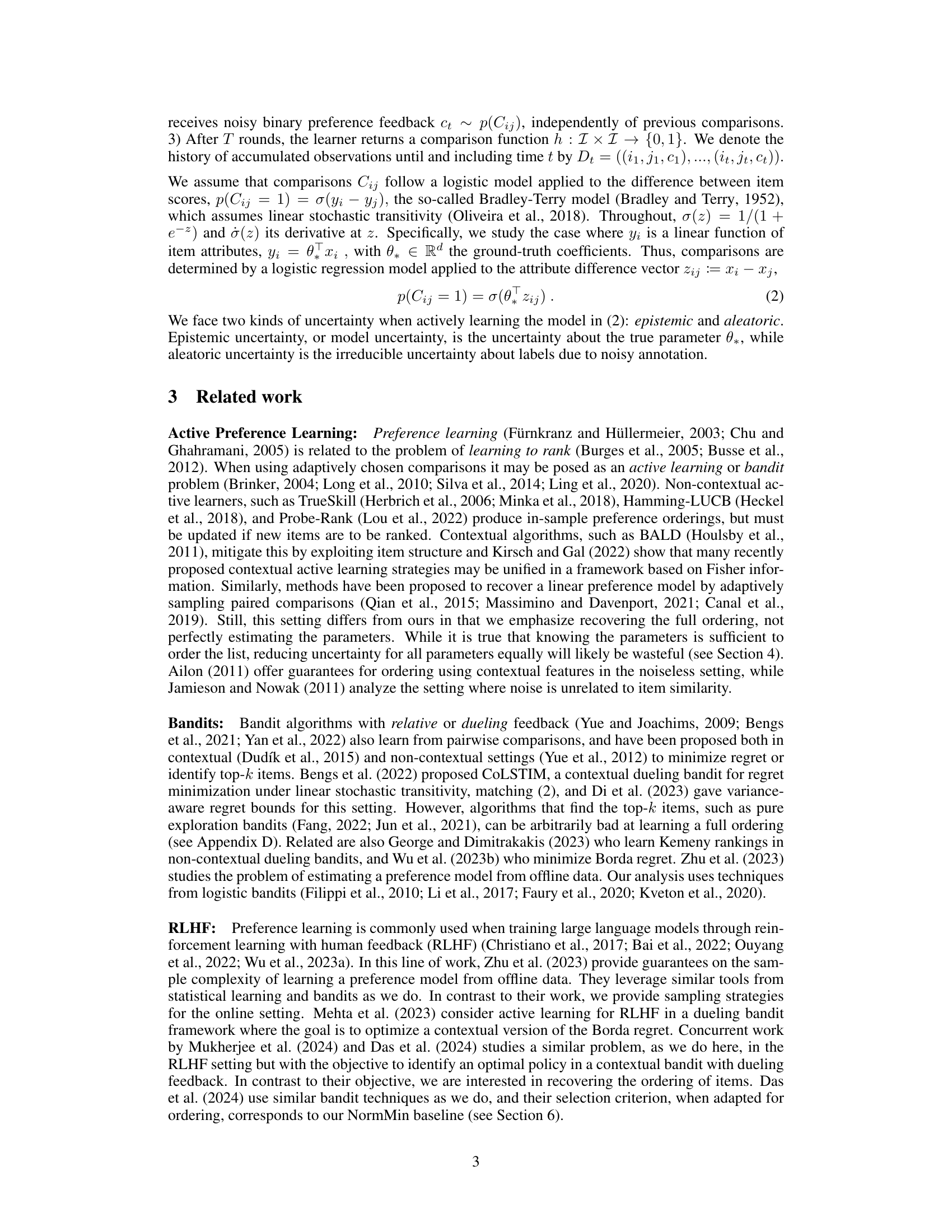

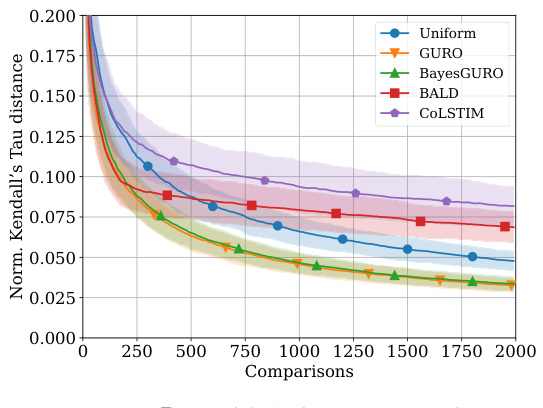

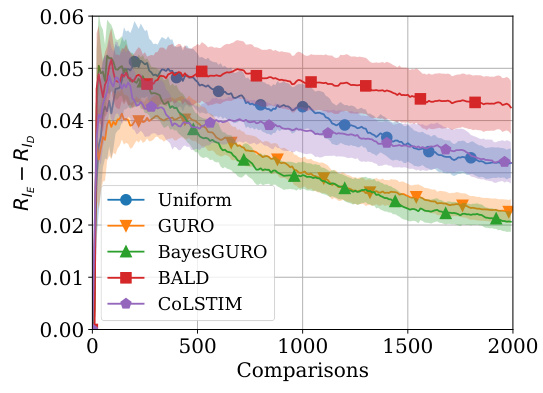

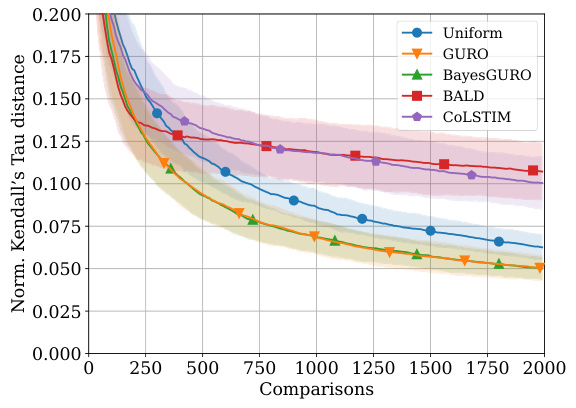

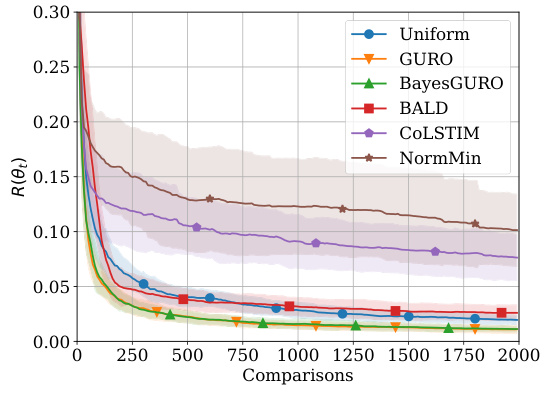

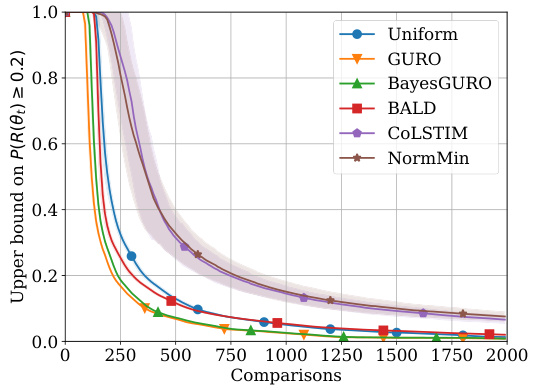

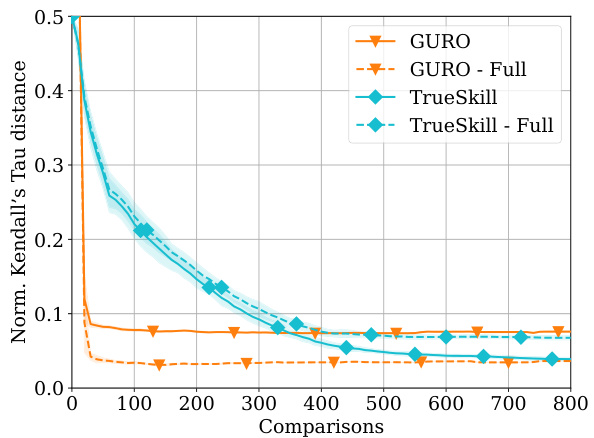

The figure shows the performance of different active sampling strategies on an X-ray image ordering task where comparisons are simulated using a logistic model. The left panel displays the in-sample Kendall’s Tau distance (a measure of ordering error) for models trained on 200 images, as a function of the number of comparisons made. The right panel shows the generalization error (the difference in error between a test set and training set) for models trained on 150 images and tested on another 150 images from a different distribution, again as a function of the number of comparisons made. Error bars representing one standard deviation are shown for all methods.

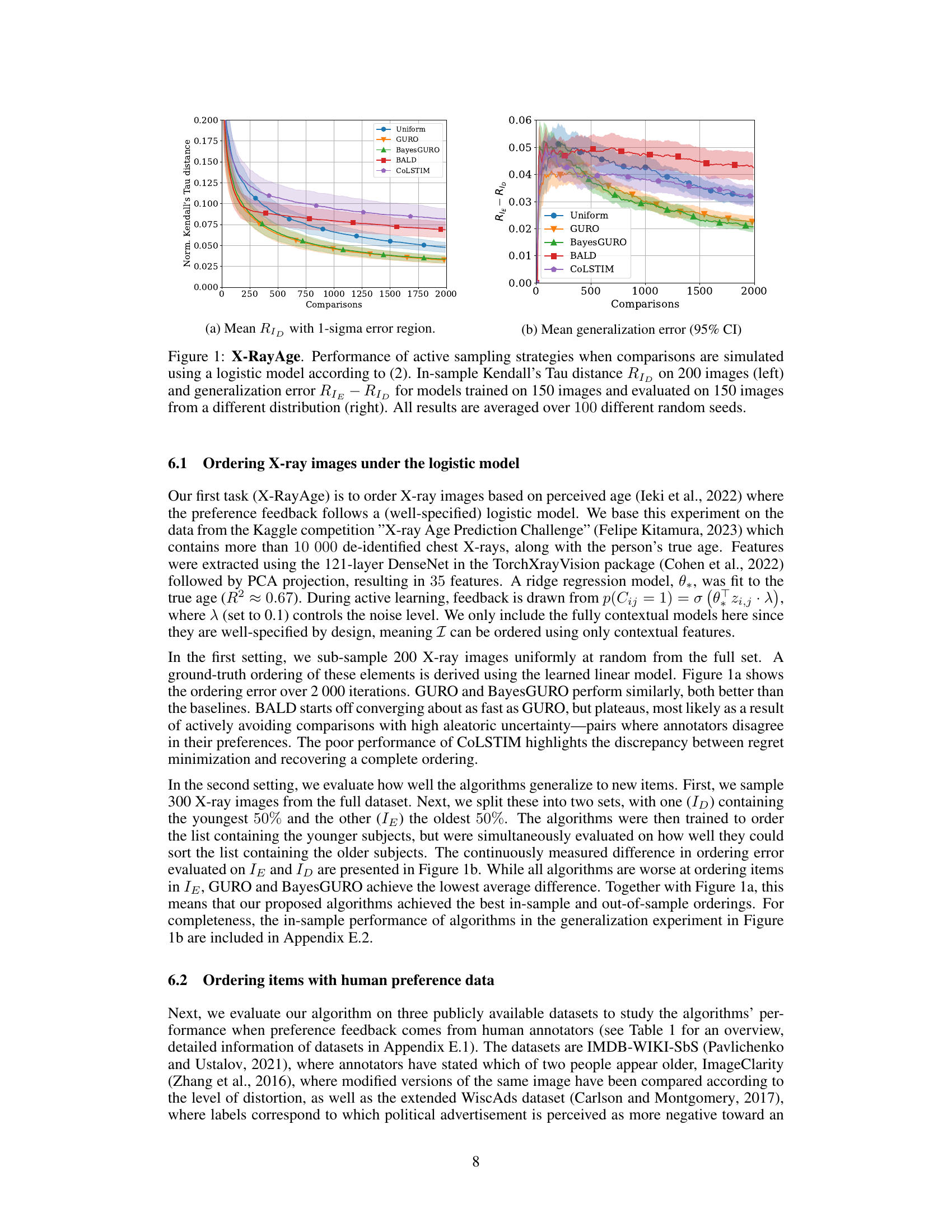

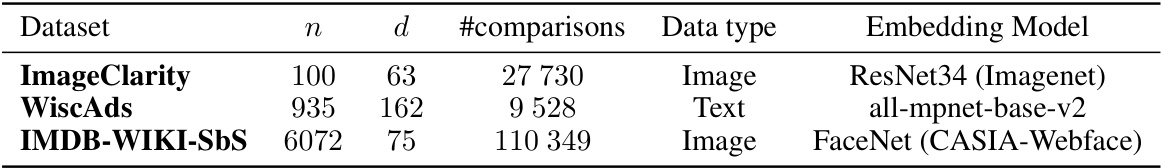

This table presents the characteristics of four datasets used in the paper’s experiments. Each dataset contains pairwise comparisons made by human annotators. The table lists the dataset name, number of items (n), dimensionality of item attributes (d), the number of comparisons available, the data type (image or text), and the pre-trained embedding model used to extract features from the data.

In-depth insights#

Active Learning Bound#

An active learning bound, in the context of preference learning, would provide a theoretical guarantee on the performance of an active learning algorithm. It would offer a way to mathematically quantify the relationship between the number of comparisons made, the model’s inherent uncertainty, and the resulting accuracy in ordering items. A tighter bound would be highly valuable, indicating strong sample efficiency. The bound should ideally account for both aleatoric (noise inherent in comparisons) and epistemic (uncertainty in model parameters) uncertainty. The analysis might involve deriving a probabilistic error bound on the resulting ranking, which could be a function of the features used to describe the items and the comparison mechanism. Such a bound could directly inform the active learning strategy itself, guiding the algorithm to select comparisons that maximize information gain and minimize the error bound, thereby improving sample efficiency. Contextual information is likely key to the development of a tighter bound, as it allows for improved generalization beyond the items used in the active learning process. The analysis of such bounds is crucial in establishing the theoretical properties of preference learning algorithms.

GURO Algorithm#

The GURO algorithm, a core contribution of this research paper, presents a novel active learning approach for efficiently learning item rankings from pairwise comparisons. GURO cleverly leverages contextual information about the items, unlike traditional preference-learning methods. This contextual approach allows GURO to minimize uncertainty in a principled way, significantly improving sample efficiency and generalization. The algorithm’s strength lies in its greedy approach, which iteratively selects item pairs for comparison based on a calculated uncertainty measure that considers both epistemic and aleatoric uncertainties. This dual-uncertainty consideration distinguishes GURO from baselines, leading to superior performance across multiple real-world datasets. Furthermore, the algorithm supports continual learning, seamlessly incorporating new items into the ranking process, making it highly adaptable to dynamic environments. A critical aspect of GURO’s design is its theoretical justification, supported by a derived upper bound on the ordering error. This theoretical foundation underpins the algorithm’s effectiveness and efficiency.

Hybrid Model#

The proposed ‘hybrid model’ for active preference learning is a significant contribution, addressing limitations of purely contextual and non-contextual approaches. By combining contextual item features with per-item parameters, it leverages the strengths of both methods. The contextual component allows for efficient in-sample ordering and generalization to unseen items using shared structure between items. Meanwhile, the per-item parameters help to mitigate misspecification and noise inherent in subjective comparisons. This hybrid approach demonstrates superior performance in several experiments. The model’s flexibility allows for the use of various feature representations (e.g., from pre-trained models) and provides a powerful framework for active learning in scenarios with both contextual information and noisy preference feedback.

Human Feedback#

Human feedback plays a crucial role in various machine learning applications, particularly those involving subjective judgments or tasks requiring human expertise. Active preference learning, for instance, heavily relies on human feedback to guide the learning process by efficiently sampling comparisons and minimizing labeling effort. The quality and consistency of human feedback directly impact the performance and generalization capabilities of the model. Aleatoric uncertainty, representing inherent noise in human judgments, and epistemic uncertainty, reflecting uncertainty in the model’s parameters, influence how to weight and interpret the human provided feedback. Addressing both types of uncertainty is essential for creating effective active learning strategies that leverage human feedback efficiently. Contextual information, incorporating item features alongside pairwise comparisons, improves sample efficiency and generalization. In essence, effective human feedback incorporation balances the efficiency of active learning with robustness towards human annotation imperfections to build high-performing models.

Future Work#

The paper’s potential future work directions are promising. Extending the theoretical analysis to encompass more complex noise models and broader classes of preference functions is crucial. This could involve exploring different types of noise beyond the logistic model, accounting for annotator biases, or handling inconsistencies. Improving the efficiency of the GURO algorithm is important, possibly through more sophisticated sampling strategies or approximation techniques. Addressing model misspecification remains a key challenge, particularly in scenarios with limited or noisy contextual features. Investigating alternate approaches like representation learning could improve performance. Finally, empirical evaluation on a wider range of tasks and datasets with different data modalities and annotation protocols would strengthen the results’ generalizability and practical implications. The incorporation of continual learning and online adaptation aspects into the algorithms would make them even more versatile.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the performance comparison of different active sampling strategies on the X-RayAge dataset. The left panel shows the in-sample Kendall’s Tau distance (a measure of ordering error) for models trained on 200 images, while the right panel presents the generalization error (difference between out-of-sample and in-sample error) for models trained on 150 images and tested on another 150 images from a different distribution. The results are averaged over 100 independent runs, showing the mean and standard deviation (error bars) for each method. The figure illustrates the sample efficiency and generalization ability of various active learning approaches for ordering problems.

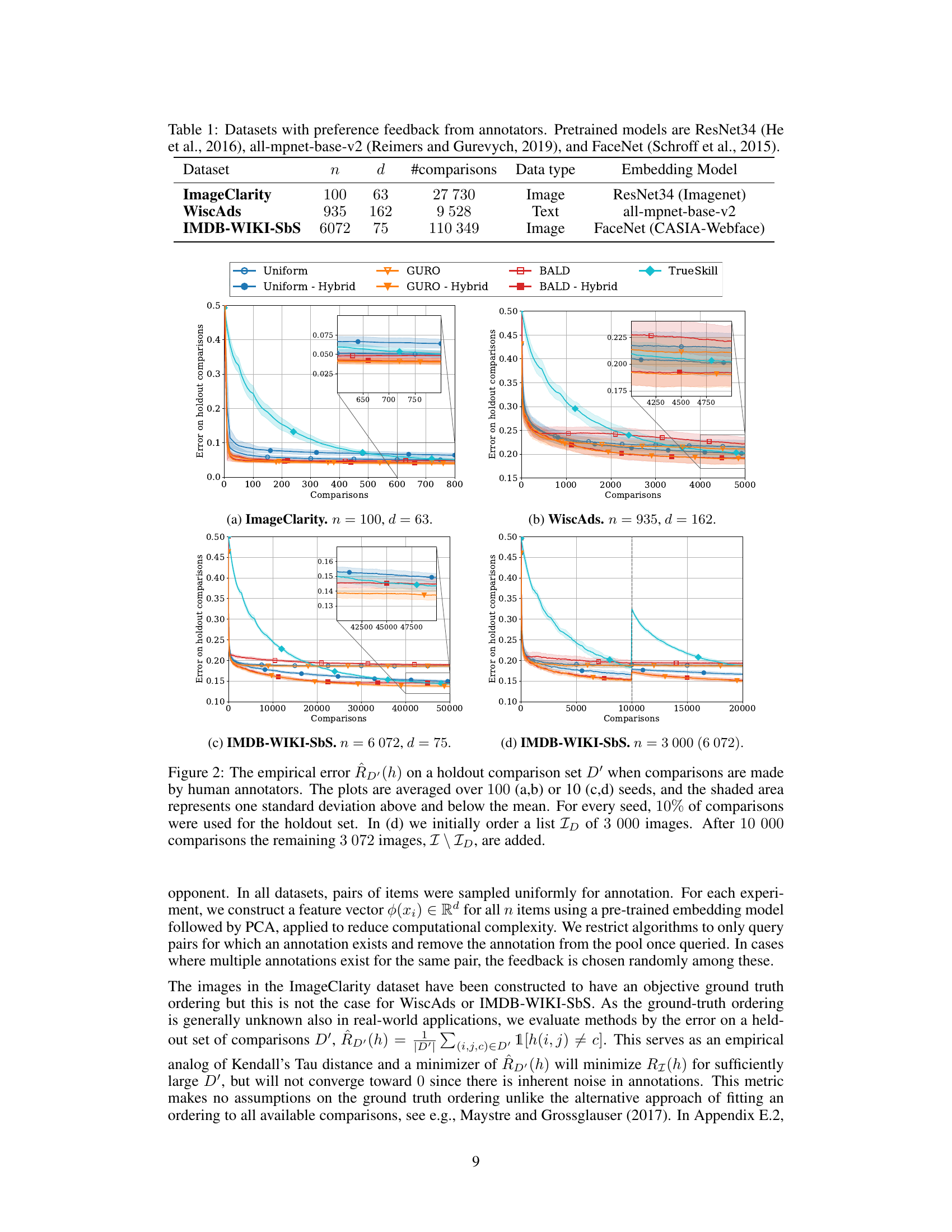

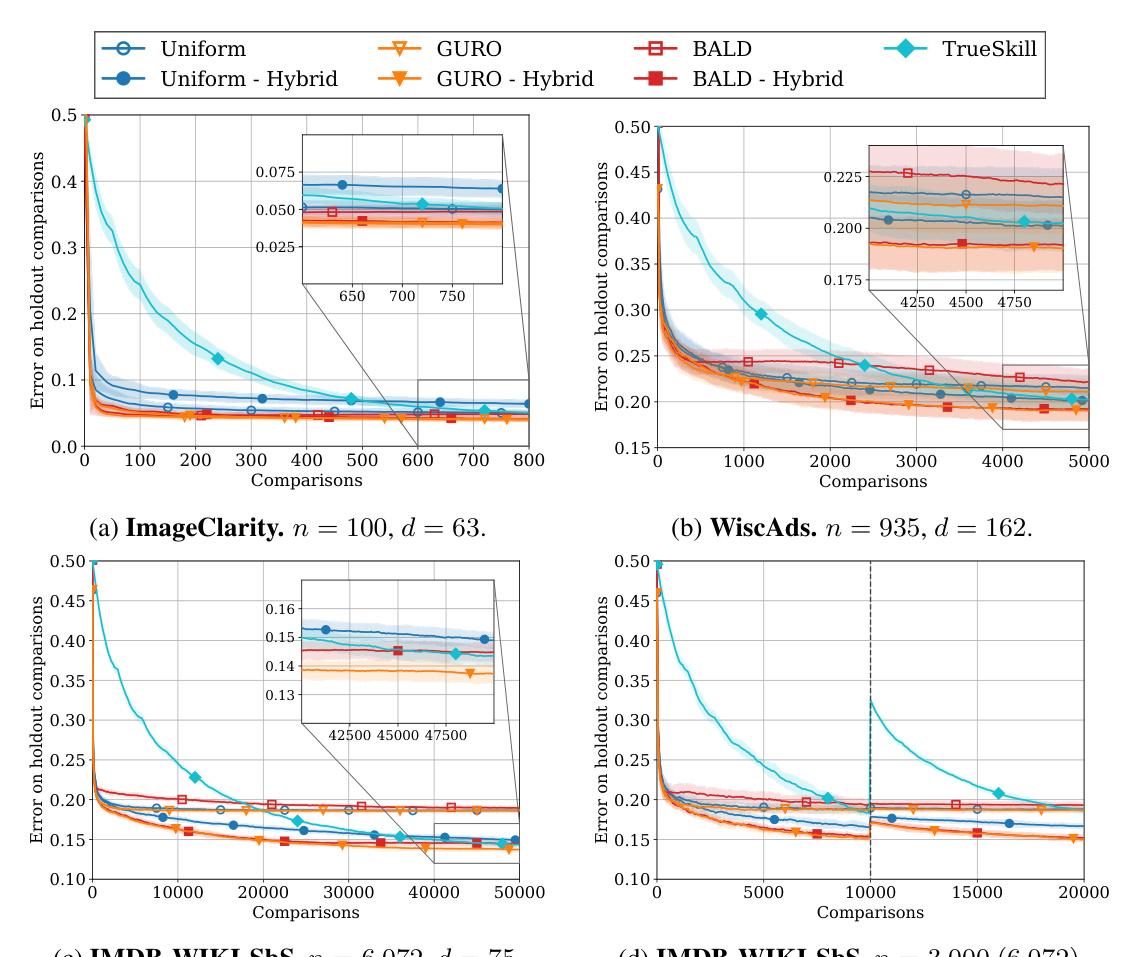

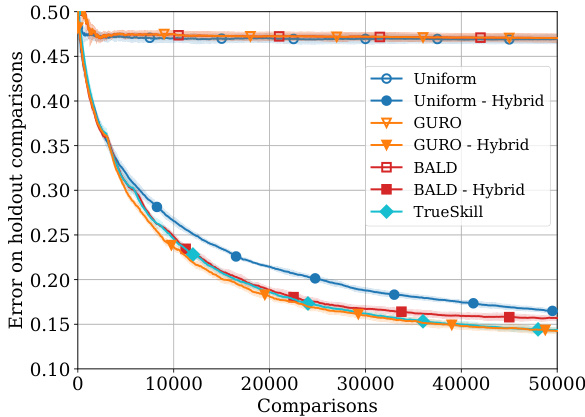

This figure compares the performance of different algorithms (Uniform, GURO, BayesGURO, BALD, COLSTIM, and TrueSkill) on three real-world datasets (ImageClarity, WiscAds, and IMDB-WIKI-SbS) and a synthetic dataset with human preference feedback. The y-axis represents the error rate on a held-out set of comparisons, showing the generalization performance of each algorithm. The x-axis represents the number of comparisons made. Shaded areas indicate standard deviation. The IMDB-WIKI-SbS plots also show continual learning (adding new items after initial training). The results demonstrate the superior performance of GURO and GURO Hybrid compared to other algorithms.

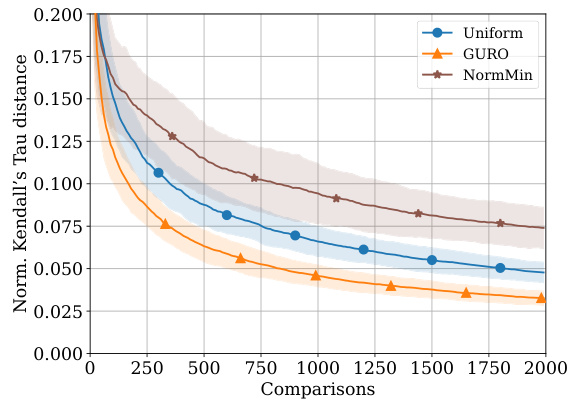

This figure shows two subfigures. Subfigure (a) shows the result of adding the NormMin algorithm to the experiment shown in Figure 1a, demonstrating that not only does NormMin perform worse than GURO, but is also outperformed by uniform sampling. Subfigure (b) shows the in-sample error (RID) during the generalization experiment performed in Figure 1b.

This figure shows the performance of different active learning algorithms for ordering X-ray images based on perceived age. The left panel displays the in-sample Kendall’s Tau distance (a measure of ordering error) for models trained on 200 images. The right panel shows the generalization error, calculated as the difference between out-of-sample and in-sample Kendall’s Tau distance, for models trained on 150 images and tested on a separate set of 150 images from a different distribution. The results are averaged across 100 different random seeds. The figure highlights the sample efficiency and generalization capabilities of different methods.

This figure presents the results of an experiment comparing different active sampling strategies for learning an item ordering from pairwise comparisons simulated using a logistic model. The left panel shows the in-sample performance (Kendall’s Tau distance) of the algorithms on 200 images as a function of the number of comparisons. The right panel shows their out-of-sample generalization performance, which measures the difference between in-sample and out-of-sample ordering errors when trained on 150 images and tested on a separate set of 150 images drawn from a different distribution. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation, and the results are averaged over 100 random trials.

This figure shows the performance of different active learning algorithms on a synthetic X-ray image ordering task. The left panel displays the in-sample Kendall’s Tau distance (a measure of ordering error) for models trained on 200 images. The right panel shows the generalization error (the difference in ordering error between a test set and training set of 150 images each) for models trained on 150 images and tested on 150 unseen images from a different distribution. The results show the average performance and a 1-sigma error region over 100 independent runs, allowing a visualization of the variability.

This figure shows the performance of different algorithms in four image ordering tasks using real-world feedback from human annotators. The plot shows the empirical error (Rp(h)) on a holdout comparison set. The results are averaged over multiple random seeds, with shaded areas representing standard deviations. A key aspect highlighted is the continual learning ability, demonstrated in subplot (d), where new items are added after an initial training period.

This figure presents the results of experiments evaluating the performance of different active learning algorithms on three real-world datasets with human-provided preference feedback. Each plot shows the ordering error on a held-out set of comparisons as a function of the number of comparisons collected. The shaded area represents the standard deviation across multiple runs. The IMDB-Wiki-SbS dataset has two subplots showing the error before and after the addition of new items to test generalization. The algorithms evaluated were Uniform sampling, GURO, BayesGURO, BALD, CoLSTIM, and TrueSkill.

This figure shows the performance of different algorithms on three real-world datasets with human feedback, evaluating the ordering error on held-out comparisons. It highlights the difference in performance between fully contextual, hybrid, and non-contextual methods, demonstrating the superior generalization capabilities of hybrid models, particularly when dealing with unseen items. The error bars represent one standard deviation, and the shaded region reflects the uncertainty.

This figure includes two subfigures. Figure 3a shows the performance of NormMin algorithm in the X-RayAge experiment, demonstrating that it performs worse than GURO and is seemingly outperformed by uniform sampling. Figure 3b shows the in-sample error (RID) during the generalization experiment presented in Figure 1b, showing similar trends as in Figure 1a.

More on tables

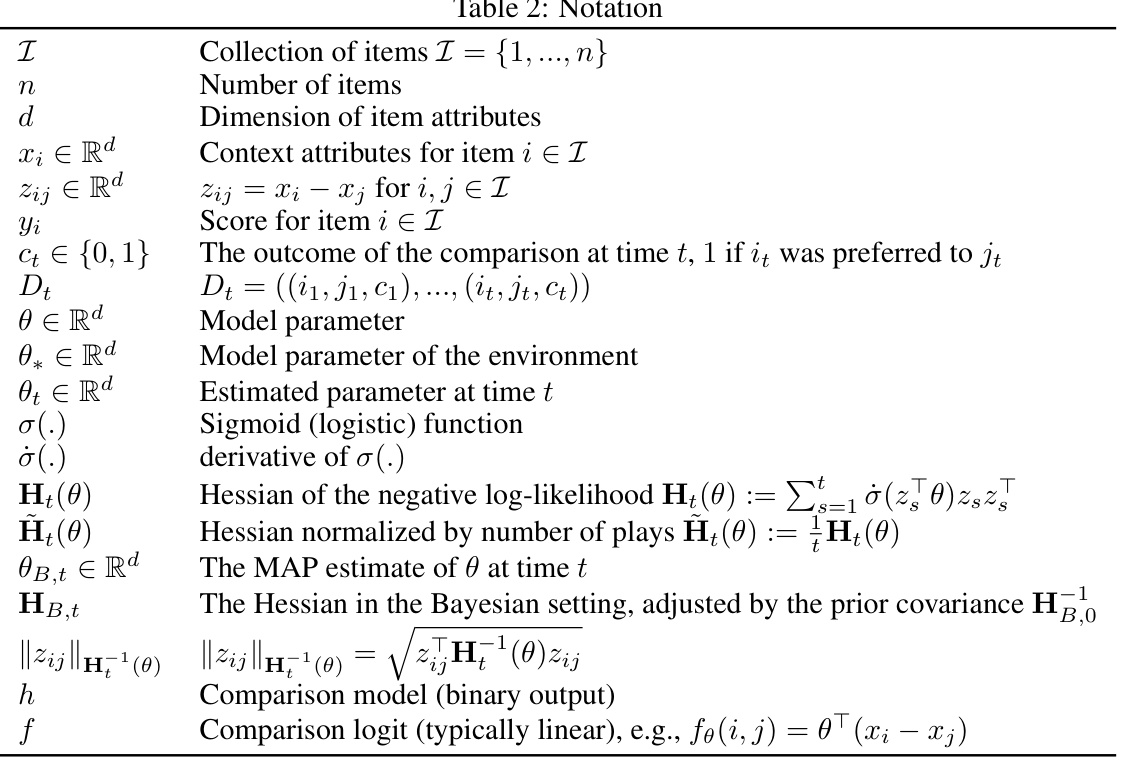

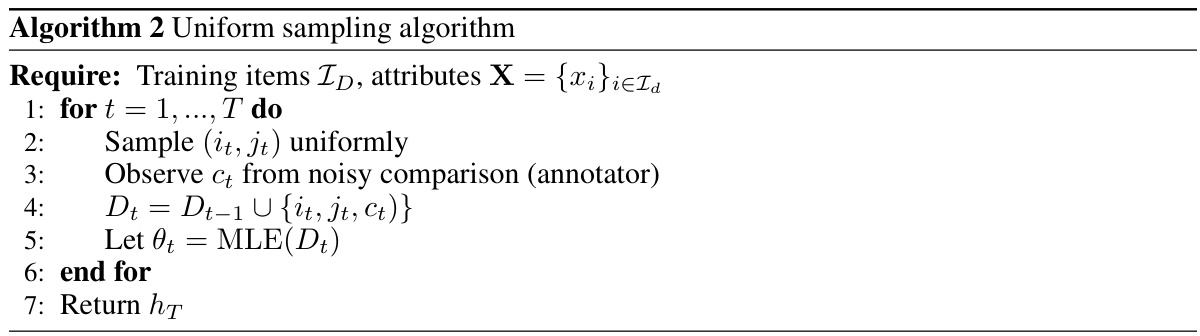

This table provides a comprehensive list of notations used throughout the paper. It includes mathematical symbols representing various concepts such as the collection of items, number of items, the dimension of item attributes, contextual attributes, scores for items, the outcome of comparisons, the model parameter, estimated parameters, the sigmoid function, Hessians (both observed and Bayesian), comparison models, and comparison logits. This table is essential for understanding the mathematical formulations and algorithms presented in the paper.

This table lists four image ordering datasets used in the paper’s experiments. Each dataset is characterized by the number of items (n), the dimensionality of the item attributes (d), the number of comparisons available, the type of data (image or text), and the pre-trained embedding model used for feature extraction. The table provides a summary of the key characteristics of the datasets used in evaluating the proposed active preference learning algorithm.

Full paper#