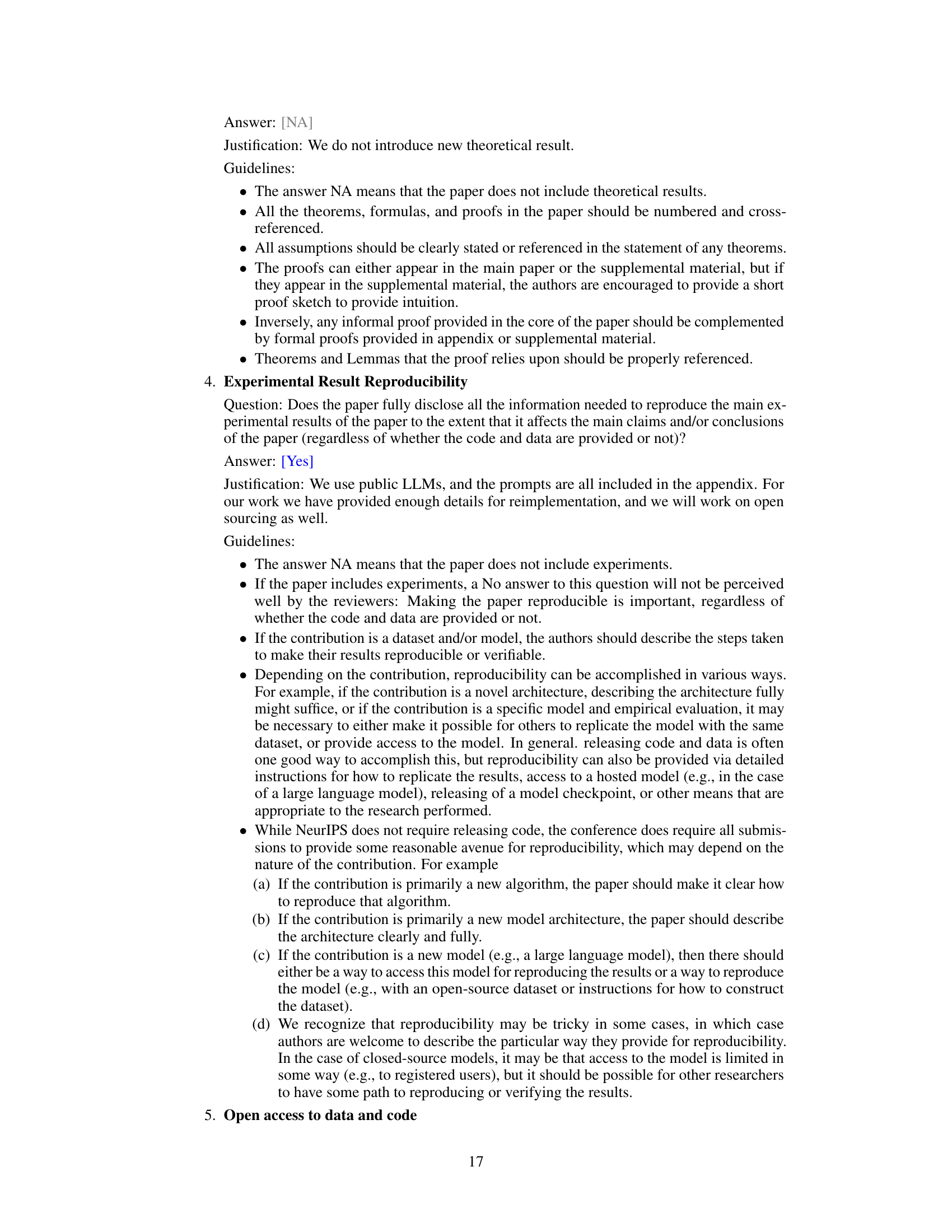

↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Designing new materials is crucial for technological advancements, but traditional methods are slow and inefficient. This paper introduces GenMS, a novel AI-powered system that overcomes this limitation. GenMS allows researchers to use natural language to describe the desired properties of a material, and the system generates candidate crystal structures that meet the specification. The key challenge is that this requires bridging the gap between high-level human descriptions and low-level material structures. Existing methods either require vast amounts of training data or need precise chemical formulas, limiting their practical usability.

GenMS tackles this challenge with a hierarchical approach, combining a large language model to interpret natural language, a diffusion model to generate crystal structures, and a graph neural network to predict material properties. A forward tree search algorithm efficiently explores the vast space of possible structures, guided by the desired properties. Experiments demonstrate that GenMS outperforms existing methods, especially in generating low-energy structures and meeting user specifications with high accuracy. This work opens exciting avenues for leveraging the power of AI in materials science and accelerating materials discovery.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to materials discovery using AI. It bridges the gap between high-level human descriptions and low-level material structures. This has the potential to significantly accelerate the pace of materials research and lead to the discovery of new materials with desired properties. The multi-objective optimization and hierarchical search method are also valuable contributions to the AI research community.

Visual Insights#

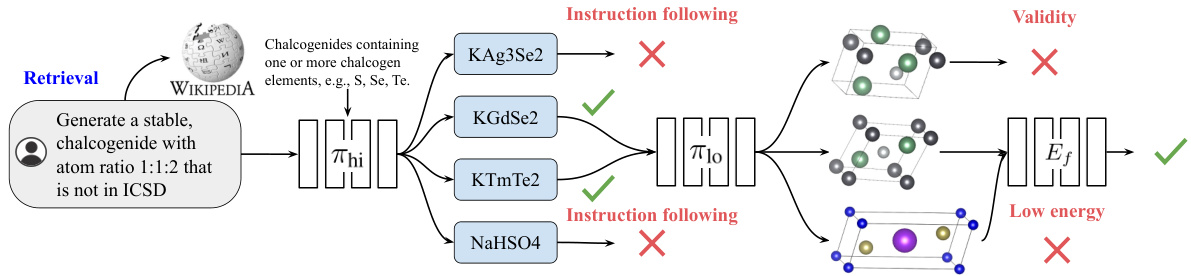

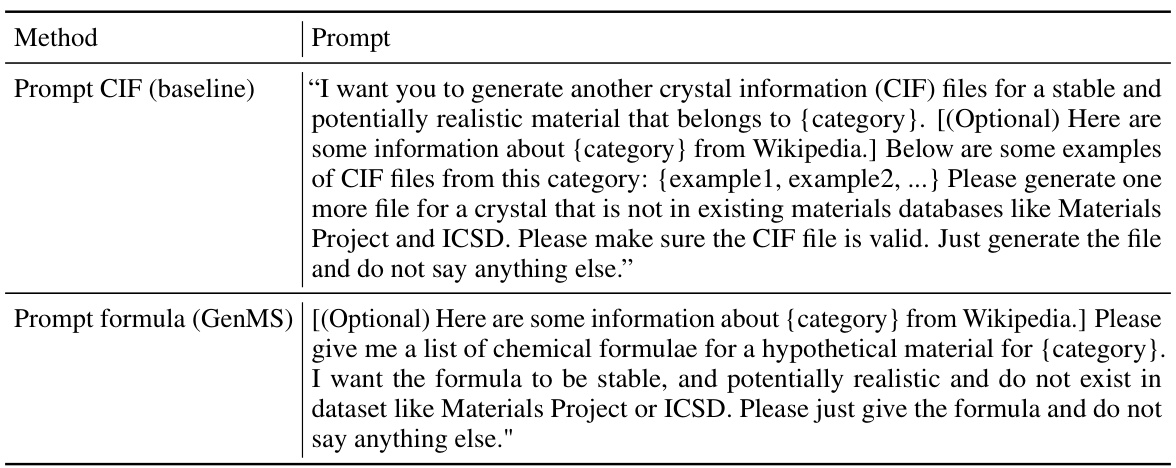

This figure illustrates the workflow of the GenMS model. It begins with a high-level natural language instruction from the user. The model then retrieves relevant information from the internet, uses a large language model (LLM) to generate candidate chemical formulas, and uses a diffusion model to generate crystal structures based on those formulas. Finally, a property prediction module selects the best structure based on various criteria (e.g., low formation energy).

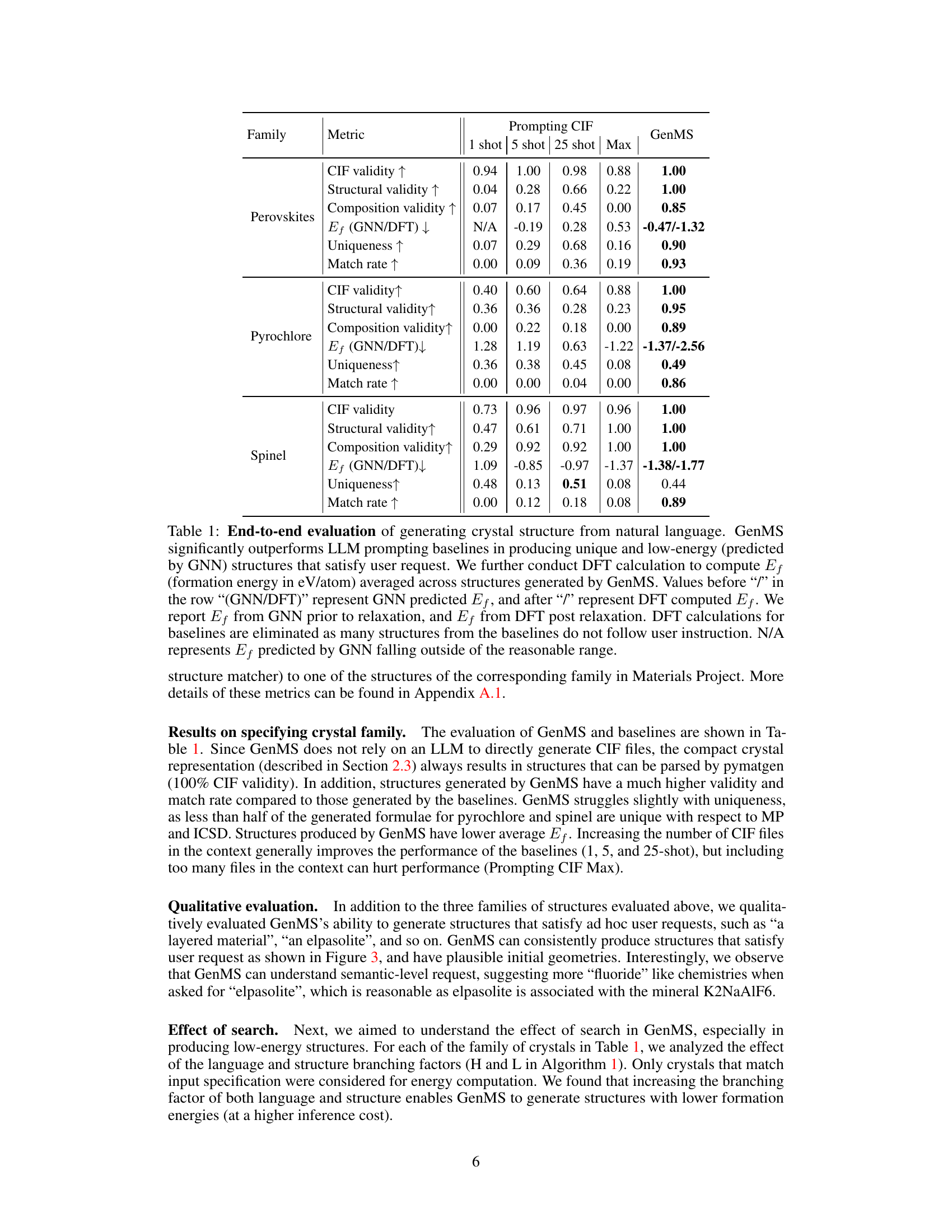

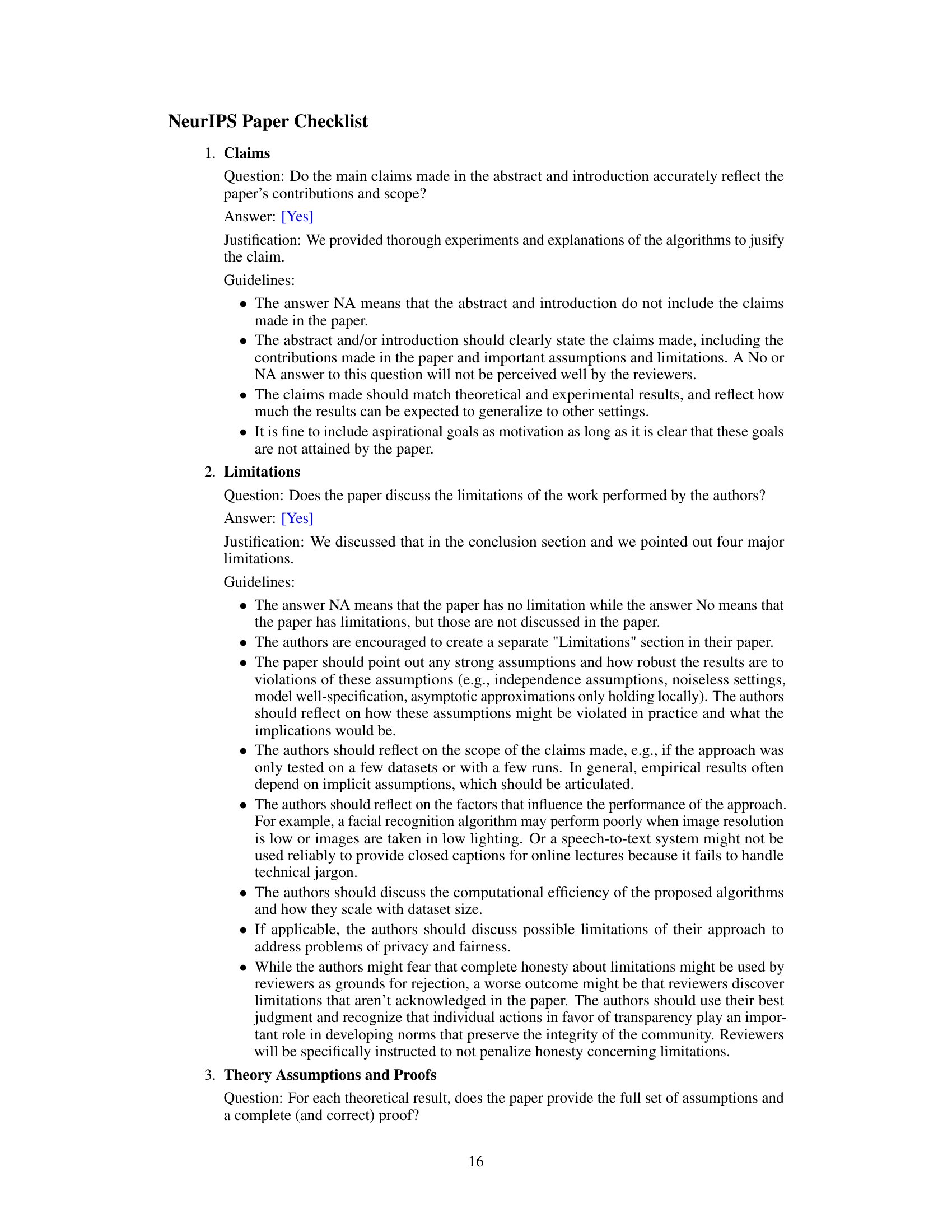

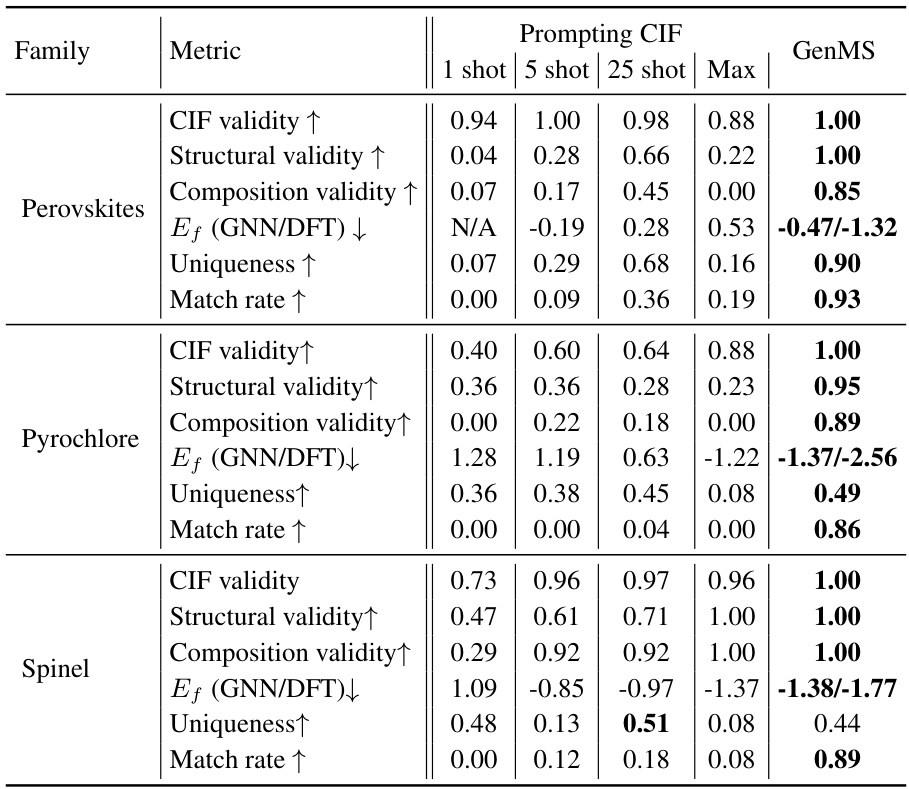

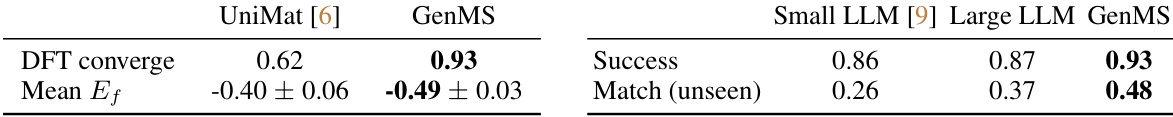

This table presents the results of an end-to-end evaluation comparing GenMS’s performance to several baselines in generating crystal structures from natural language prompts. It shows GenMS’s superiority across multiple metrics, including CIF validity, structural validity, composition validity, formation energy (Ef), uniqueness, and match rate, particularly for three crystal families: Perovskites, Pyrochlore, and Spinel. Formation energies are evaluated using both a Graph Neural Network (GNN) prediction and Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations.

In-depth insights#

GenMS Overview#

The Generative Hierarchical Materials Search (GenMS) system is designed for controllable generation of crystal structures from high-level natural language descriptions. It leverages a three-component architecture: a language model translates high-level instructions into intermediate textual representations (e.g., chemical formulae); a diffusion model generates crystal structures based on this intermediate information; and finally, a graph neural network predicts material properties to aid selection. GenMS employs a forward tree search during inference, iteratively refining and validating potential structures until one best satisfies the user’s specified requirements. This hierarchical approach allows GenMS to overcome the limitations of direct language-to-structure methods, achieving improved accuracy and control over the final crystal structure. The multi-objective optimization strategy employed enables GenMS to balance user-specified criteria with the generation of low-energy, stable structures. GenMS’s key innovation lies in its ability to bridge the gap between high-level human understanding and low-level structural details in materials science, promising advancements in materials discovery and design.

Multi-objective Search#

A multi-objective search strategy in the context of materials discovery would involve simultaneously optimizing multiple, often competing, objectives. Finding a material with desired properties (e.g., high strength, low weight, corrosion resistance) often necessitates trade-offs. The search algorithm needs to efficiently explore the vast chemical space, balancing the various objectives to identify Pareto optimal solutions – those where improvement in one objective would necessarily worsen another. This might involve using advanced search techniques such as genetic algorithms or simulated annealing to explore the solution space efficiently, coupled with a heuristic function or fitness function that evaluates the trade-offs between different objectives for each candidate material. The success of such a search hinges on the proper definition of the objectives and the choice of a suitable search algorithm that can handle the complexity of the multi-dimensional optimization problem. Furthermore, handling noisy or incomplete data is a significant challenge that needs to be addressed effectively. Therefore, a robust multi-objective search strategy should be adaptable and efficient in navigating the inherent uncertainty and complexity of the materials discovery landscape.

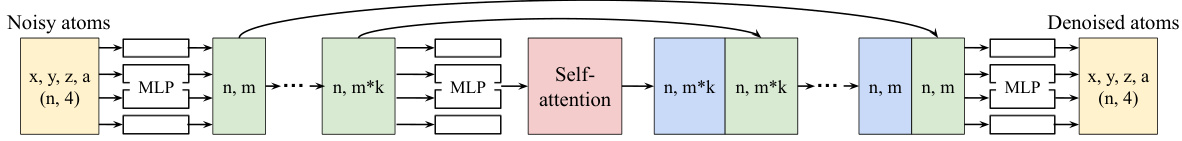

Compact Crystal#

The concept of “Compact Crystal” representation in the context of crystal structure generation signifies a crucial advancement. Traditional methods often relied on sparse representations like voxel grids or graphs, leading to computational inefficiencies, especially as crystal complexity increased. The innovation here lies in using a dense, low-dimensional tensor to represent each crystal structure, encoding atom coordinates (x, y, z) and atom type as a continuous value. This compact representation significantly improves the efficiency of diffusion models trained on crystal structure data, enabling faster sampling and better scalability. The design choice directly addresses the computational bottleneck of previous approaches, making the model more practical and efficient for generating crystal structures. This density allows for improved handling of large crystal systems and facilitates the integration of the diffusion model within a hierarchical framework for language-guided crystal structure generation.

Language Effects#

The effects of language on a model’s ability to generate crystal structures are multifaceted and crucial. High-level natural language descriptions act as powerful constraints, guiding the model toward desired properties, compositions, and space groups. The specificity of language directly impacts the success rate of generating valid and relevant structures. Vague or ambiguous language leads to lower accuracy, necessitating more sophisticated search strategies to filter through many candidate structures. In contrast, precise and detailed language provides stronger guidance, enabling the model to converge more efficiently on suitable results. This highlights the importance of carefully crafting prompts to maximize the model’s effectiveness. The model’s capacity to interpret complex semantic relationships within the language is also critical, influencing its ability to infer implicit information and generate sophisticated crystal structures from relatively concise descriptions. Future research could explore ways to enhance the model’s linguistic comprehension and refine its ability to handle nuanced and multi-objective requests.

Future Work#

The ‘Future Work’ section of this research paper presents exciting avenues for expansion. Improving the generation of complex crystal structures, such as Mxenes and Kagome lattices, is a key challenge. The current model, while effective for simpler structures, needs enhancement to handle the intricate geometries and compositions of more complex materials. Another crucial area is validating the model’s predictions experimentally. The generated crystal structures, while promising, need to be synthesized and their properties verified to confirm the model’s accuracy and assess their potential for real-world applications. Extending the model to other chemical systems, such as molecules and proteins, holds significant promise. This would broaden the scope of the research and offer novel insights into the design of a wider range of materials. Finally, incorporating predictive models for material synthesizability would complete the design process and ensure only feasible materials are generated, allowing for direct application in real world scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

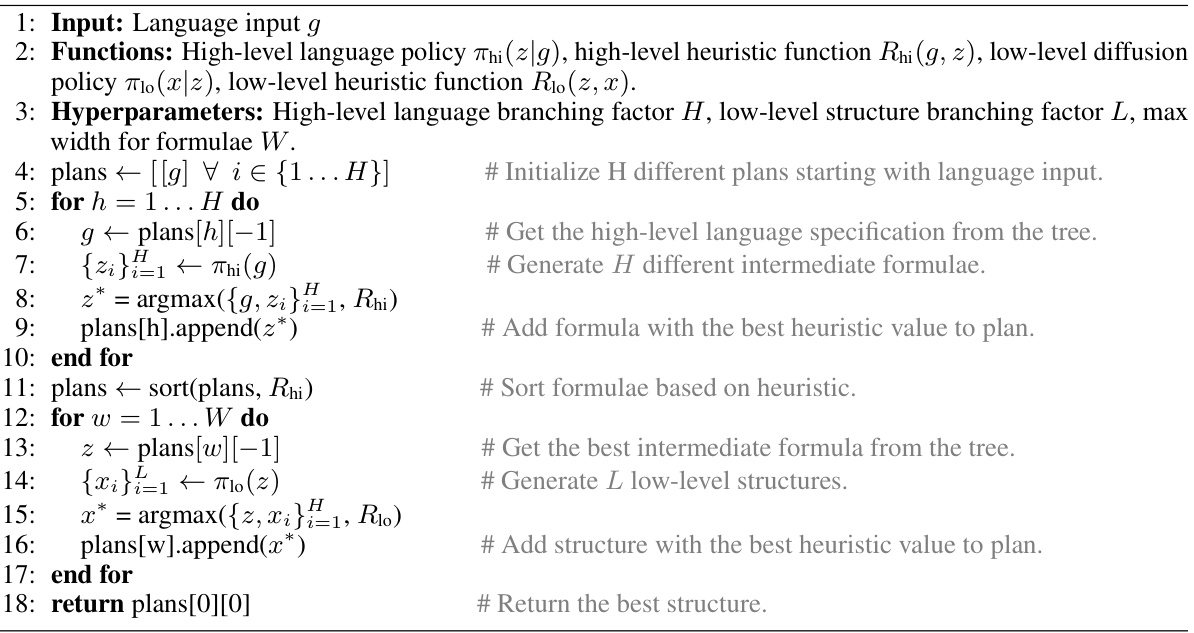

This figure provides a visual overview of the Generative Hierarchical Materials Search (GenMS) process. It starts with a high-level natural language instruction from a user. GenMS leverages a large language model (LLM) to retrieve relevant information, generate candidate chemical formulas, and rank them based on user requirements. Next, a diffusion model is used to generate crystal structures based on the top-ranked formulas. Finally, a property prediction module evaluates and selects the best-performing crystal structure that meets user specifications.

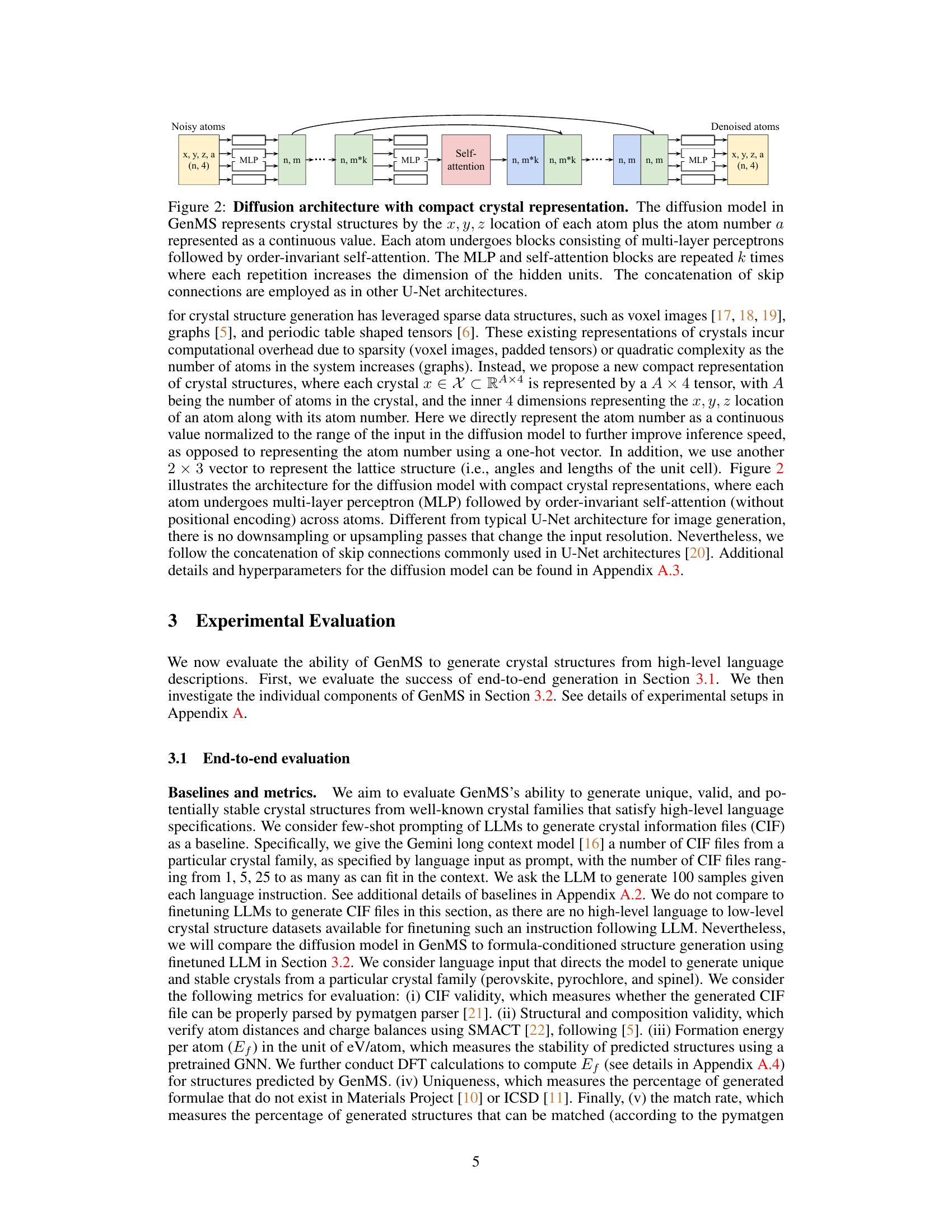

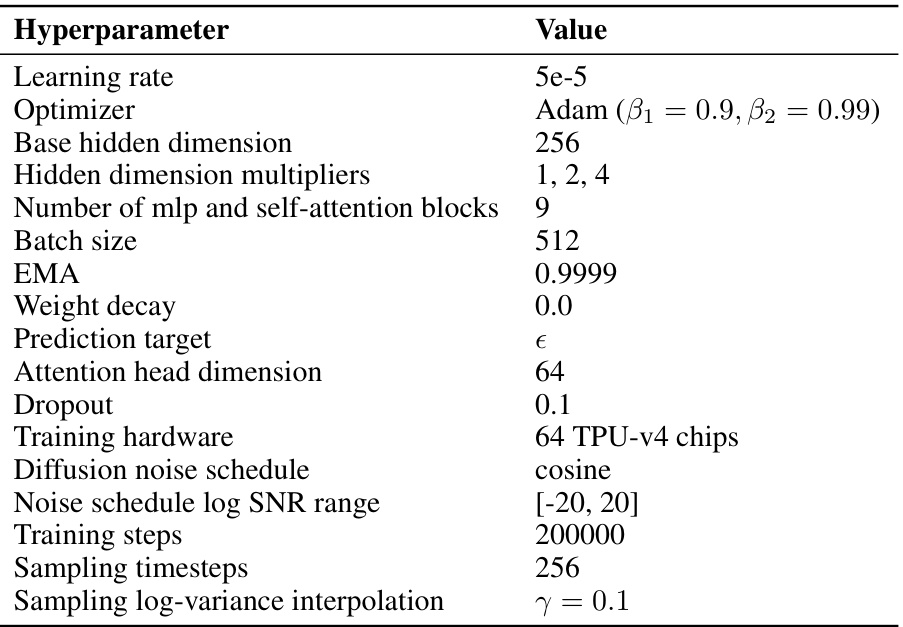

This figure illustrates the architecture of the diffusion model used in GenMS for generating crystal structures. The model uses a compact representation of crystals, where each atom is represented by its x, y, z coordinates and atomic number (as a continuous value). The model consists of multiple blocks, each containing a multi-layer perceptron (MLP) followed by an order-invariant self-attention mechanism. These blocks are repeated to increase the dimensionality of the hidden units. Skip connections are used to enhance information flow between different layers, similar to the U-Net architecture.

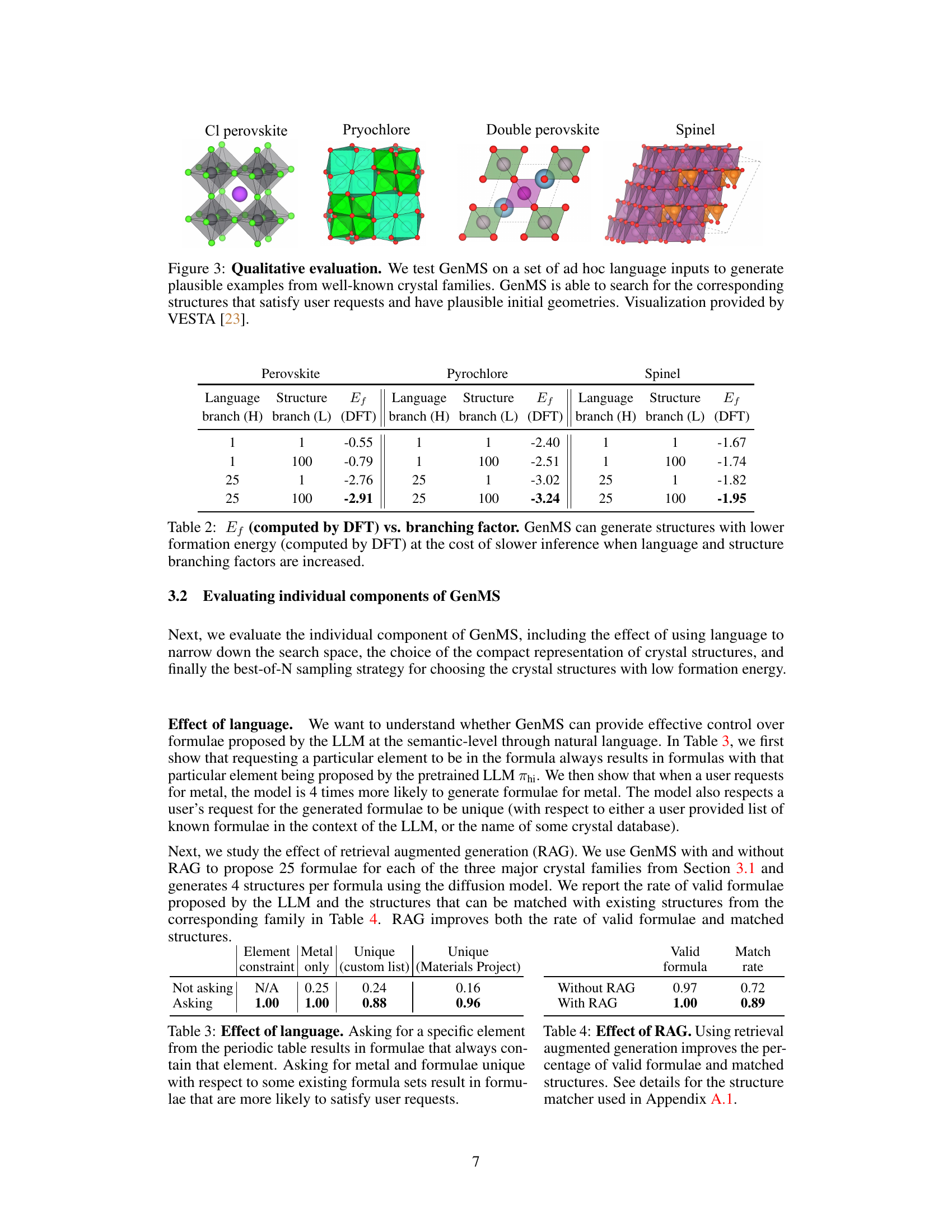

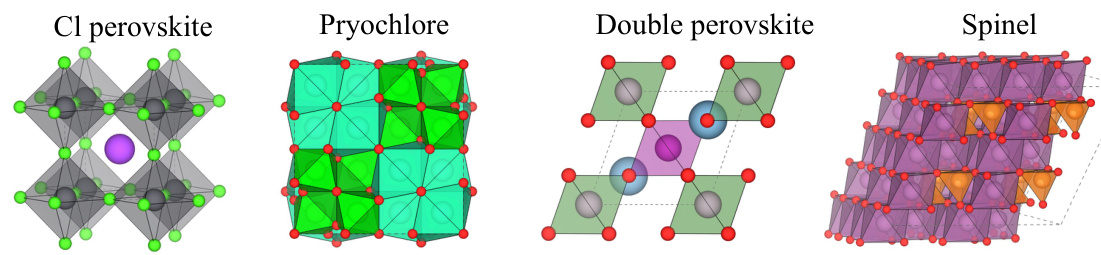

This figure shows four examples of crystal structures generated by GenMS from ad-hoc language inputs. The structures shown are a Cl perovskite, a pyrochlore, a double perovskite, and a spinel. The figure demonstrates GenMS’s ability to generate diverse and complex crystal structures based on natural language descriptions.

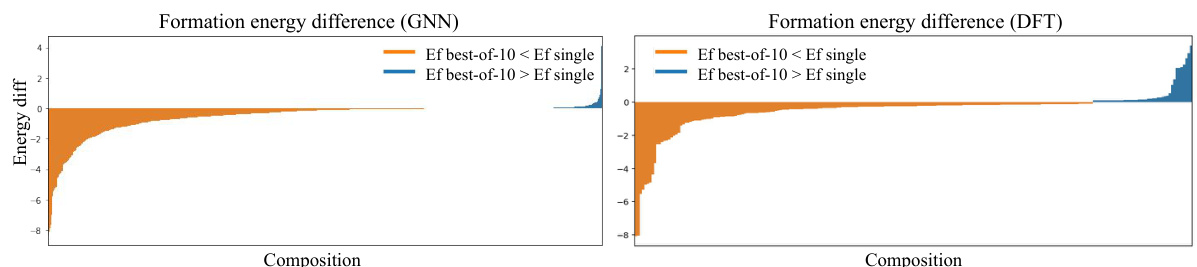

This figure shows a comparison of formation energies obtained using two different methods: a single sample and the best of 10 samples. The formation energies are predicted by a Graph Neural Network (GNN) and calculated using Density Functional Theory (DFT). The results indicate that selecting the best out of 10 samples significantly improves the energy compared to using just a single sample for about 80% of the 1000 compositions tested. This highlights the benefit of the Best-of-N sampling strategy in GenMS for finding low-energy crystal structures.

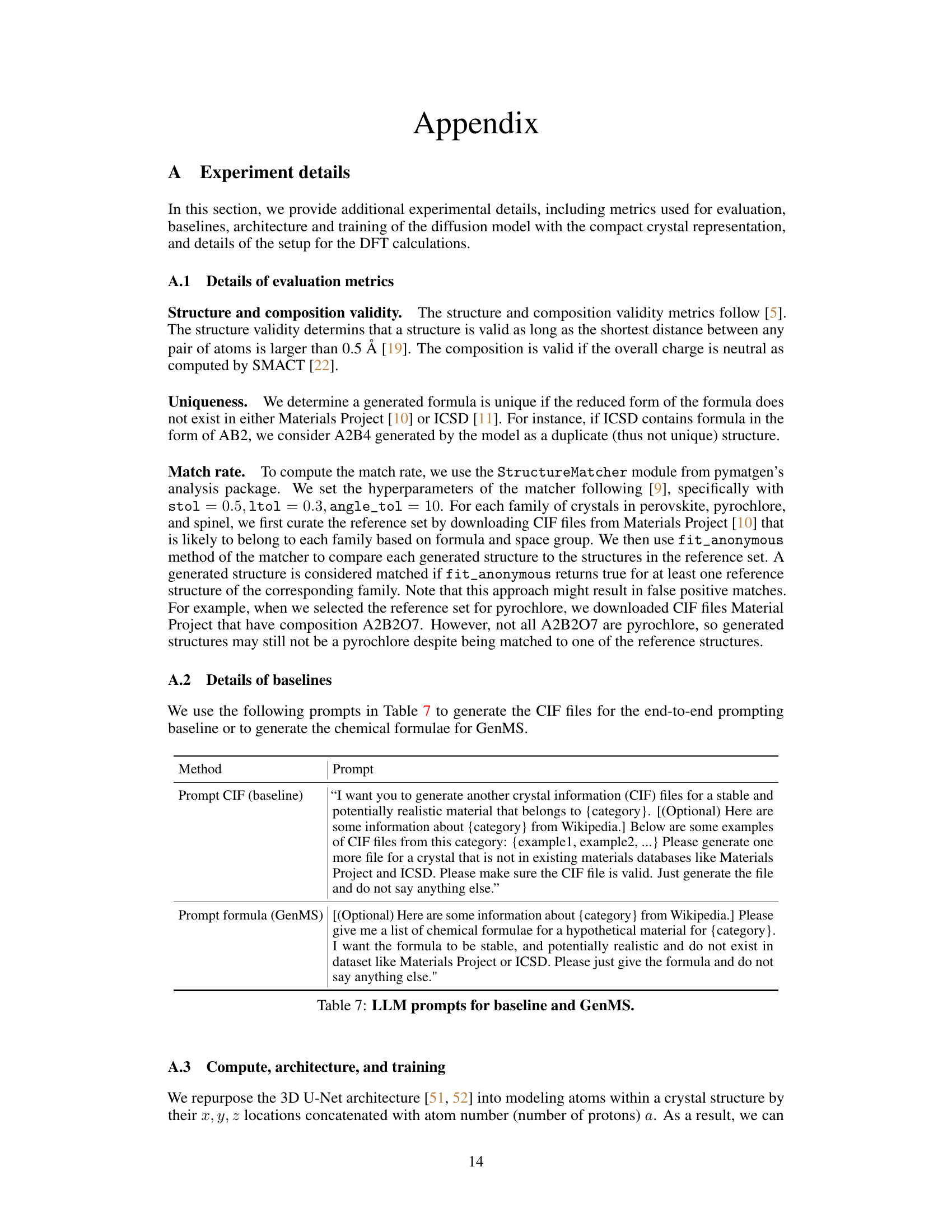

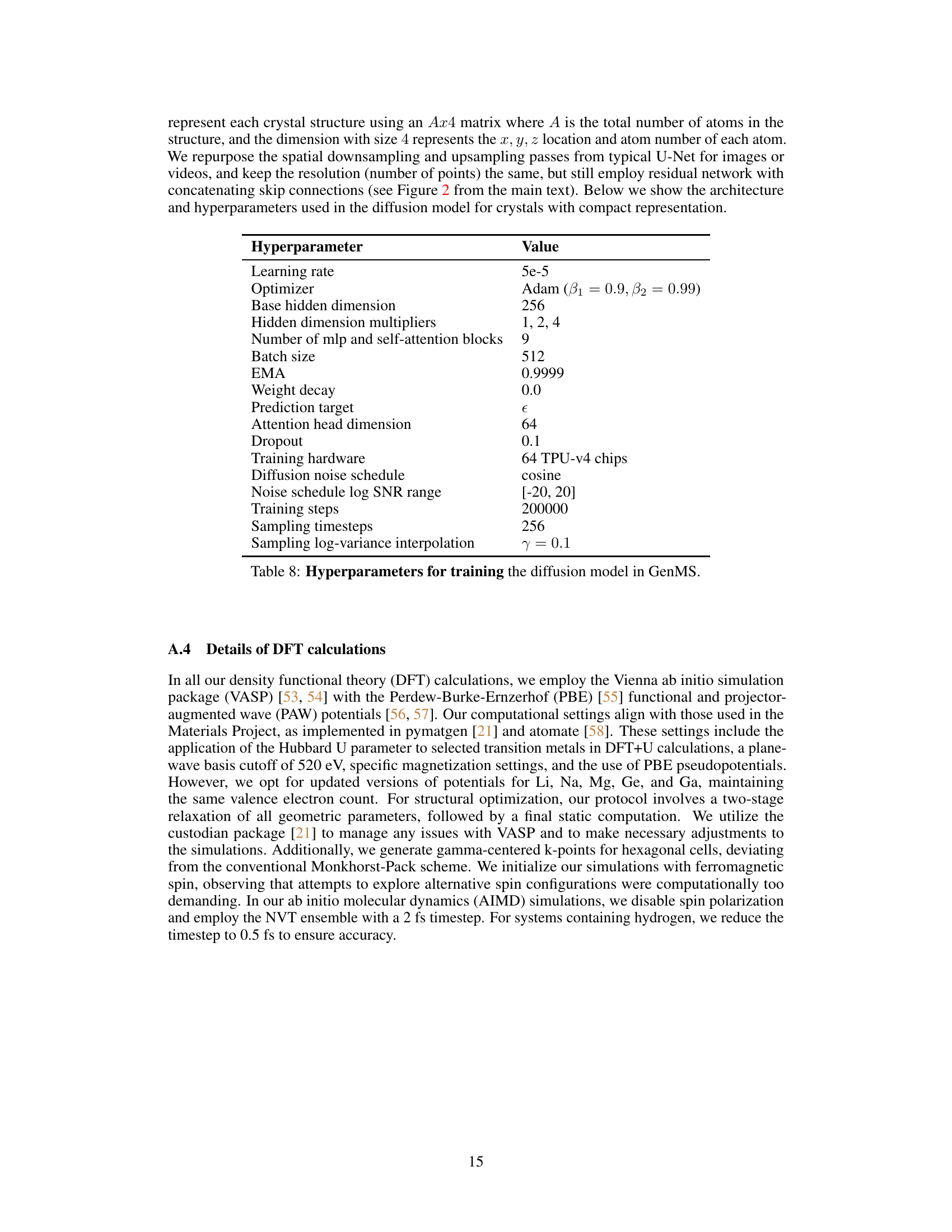

More on tables

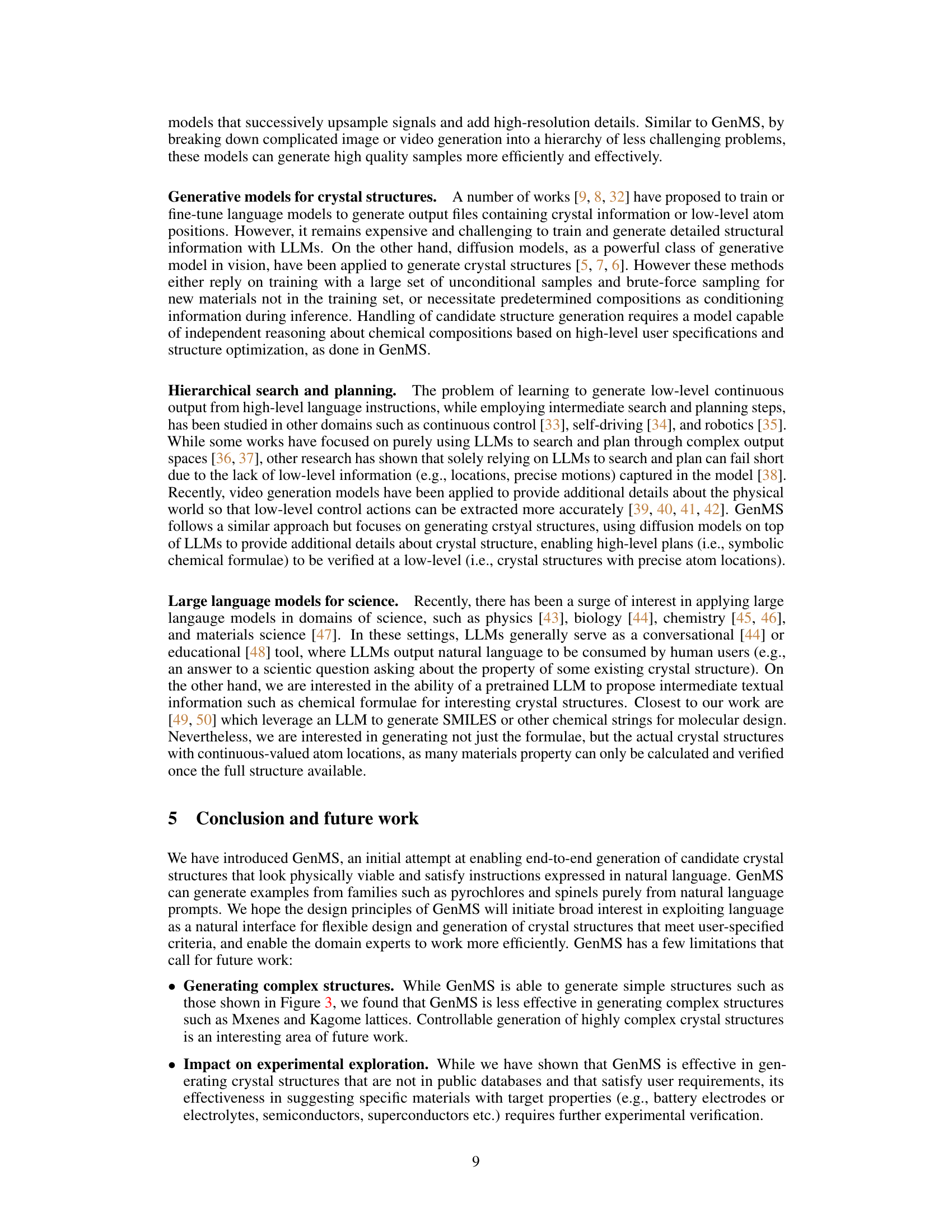

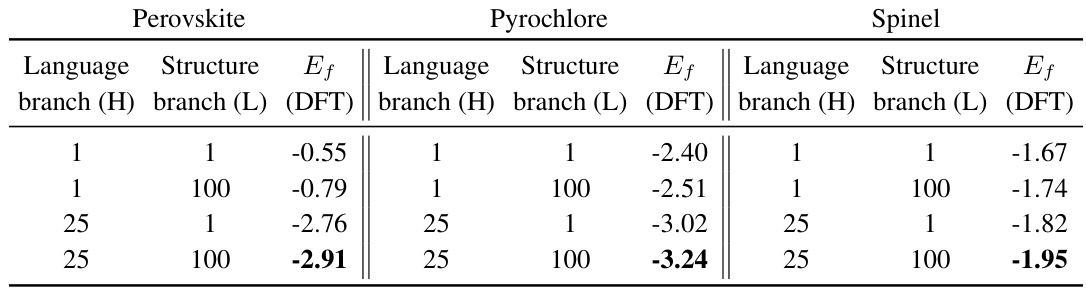

This table shows the DFT-computed formation energy (Ef) for structures generated by GenMS across different branching factors. It demonstrates the trade-off between computational cost and the quality of the generated structures in terms of lower formation energy. Higher branching factors lead to structures with lower formation energies but increased computational cost.

This table demonstrates how the language model responds to different prompts. The first column shows the prompt type: whether an element constraint was included or not. The next three columns represent success rates when requesting uniqueness against different existing datasets. The last column shows the success rate when requesting a specific metal.

This table presents a comparison of GenMS against several baseline methods for generating crystal structures from natural language descriptions. It shows that GenMS significantly outperforms the baselines in terms of generating valid, unique, and low-energy crystal structures that meet the user’s specifications. The metrics used include CIF validity, structural validity, compositional validity, formation energy (both GNN-predicted and DFT-calculated), uniqueness of the generated structures, and the match rate to existing crystal structures.

This table presents the results of an end-to-end evaluation of GenMS and baseline methods for generating crystal structures from natural language descriptions. It compares the performance of GenMS against several baselines in terms of CIF validity, structural validity, composition validity, formation energy (Ef), uniqueness, and match rate. The formation energy is computed using both GNN prediction and DFT calculation. It demonstrates that GenMS significantly outperforms baseline methods across all metrics.

This table presents a comparison of GenMS and LLM prompting baselines in generating crystal structures from natural language descriptions. It evaluates various metrics including CIF validity, structural validity, compositional validity, formation energy (Ef) as predicted by a graph neural network (GNN) and calculated using Density Functional Theory (DFT), uniqueness of generated structures, and the match rate to known crystal structures. The results show that GenMS significantly outperforms the baselines across all metrics, particularly in generating valid and low-energy structures that meet user requests.

Full paper#