TL;DR#

Current backdoor attacks require either retraining classifiers with clean data or modifying their architecture, which is inefficient, less stealthy and not always applicable. This makes them less suitable for large models or situations with limited data. The existing attacks also lack formal analysis against advanced defenses, potentially underestimating the actual threat.

This paper introduces Data-Free Backdoor Attacks (DFBA), a novel approach that overcomes these limitations. DFBA modifies a classifier’s parameters to inject a backdoor without retraining or architectural changes. The paper provides theoretical proof of its undetectability and unremovability by existing defenses, along with empirical evidence showing its high effectiveness and stealthiness against multiple datasets and state-of-the-art defenses. DFBA significantly advances backdoor attack research by enhancing stealthiness and practicality.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in AI security and machine learning because it introduces a novel backdoor attack that is both stealthy and effective against existing defenses. This work highlights a significant vulnerability in current model sharing practices and motivates the development of more robust defenses.

Visual Insights#

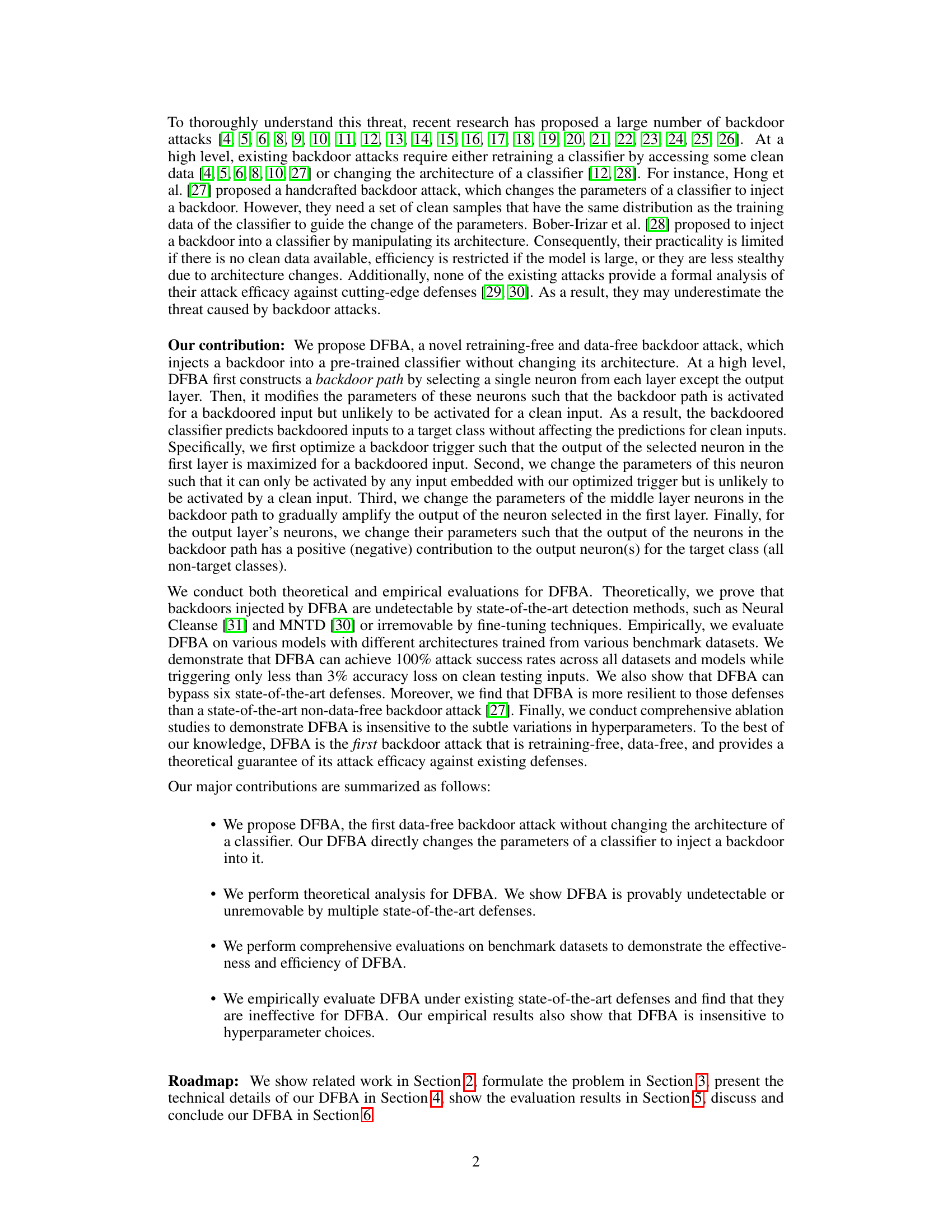

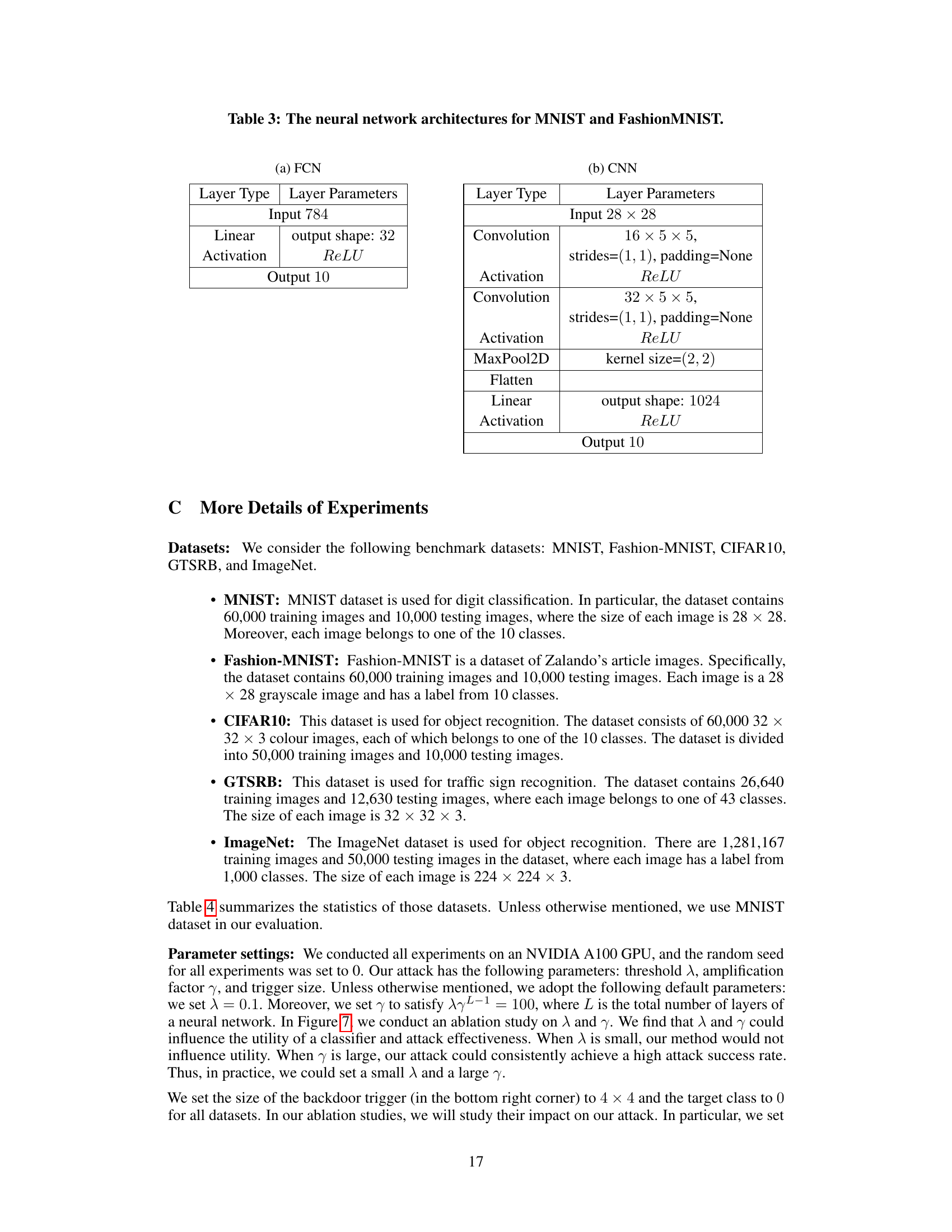

🔼 This figure illustrates a simplified example of how the backdoor switch mechanism works in the first convolutional layer of a neural network. A filter (a set of weights) is selected in the first layer. The attacker optimizes a trigger pattern (represented as a small matrix with values 0 or 1) such that the filter’s output is maximized when the trigger is present. The bias (b) of the filter is then adjusted to ensure activation with the trigger, yet keeps the filter mostly inactive when the trigger is absent. The blue cells indicate the selected filter, the red cells the trigger pattern, and the numbers are the filter weights.

read the caption

Figure 1: An example of the backdoor switch and optimized trigger when each pixel of an image is normalized to the range [0, 1].

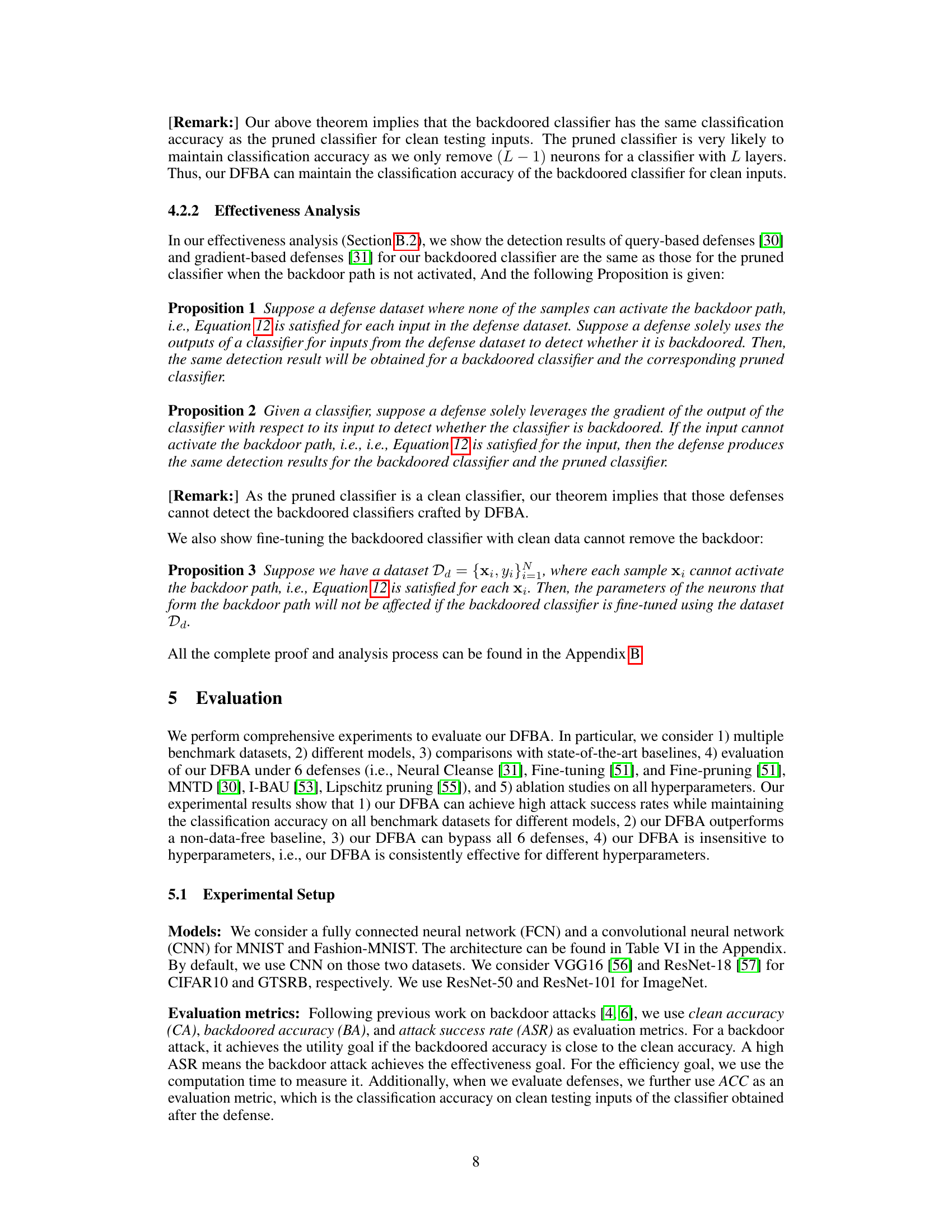

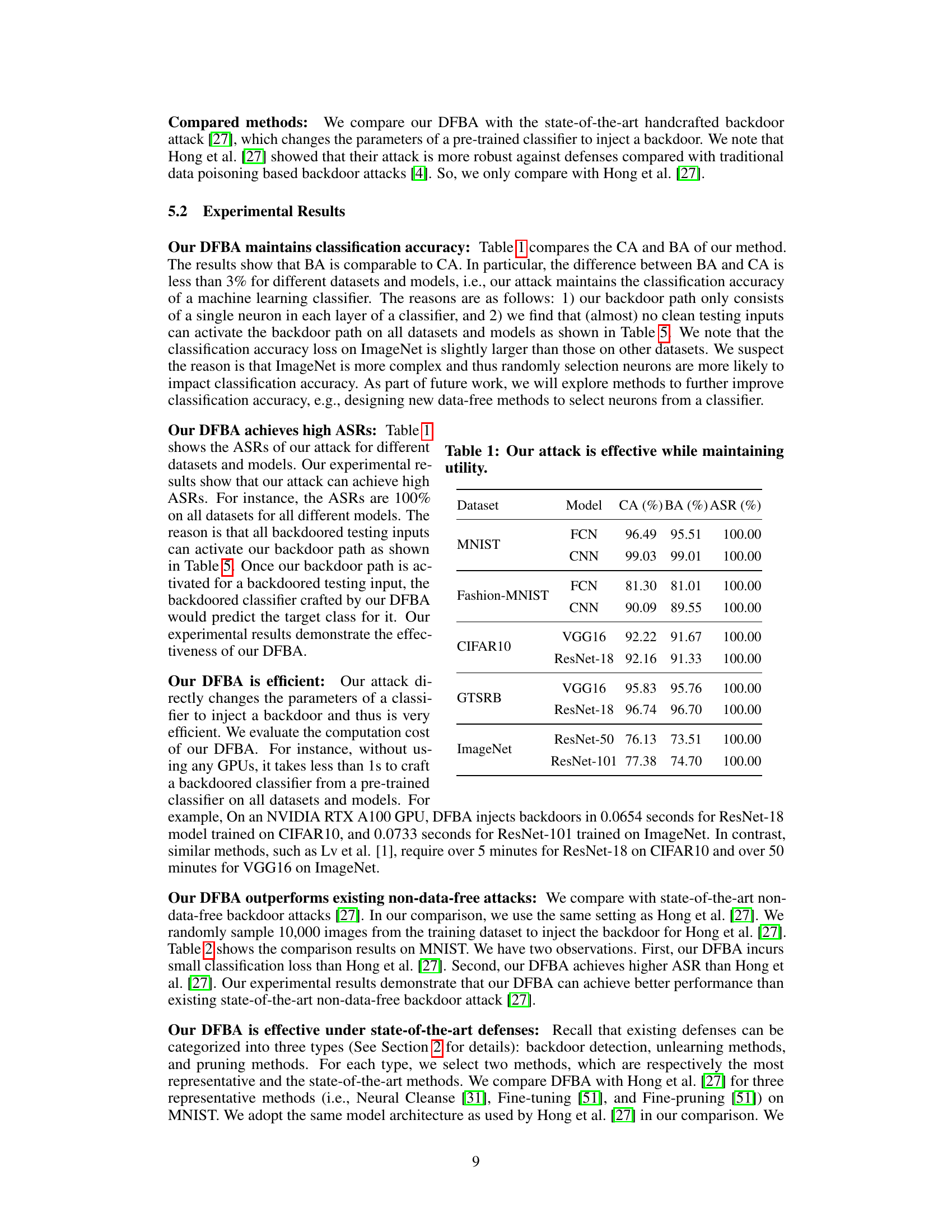

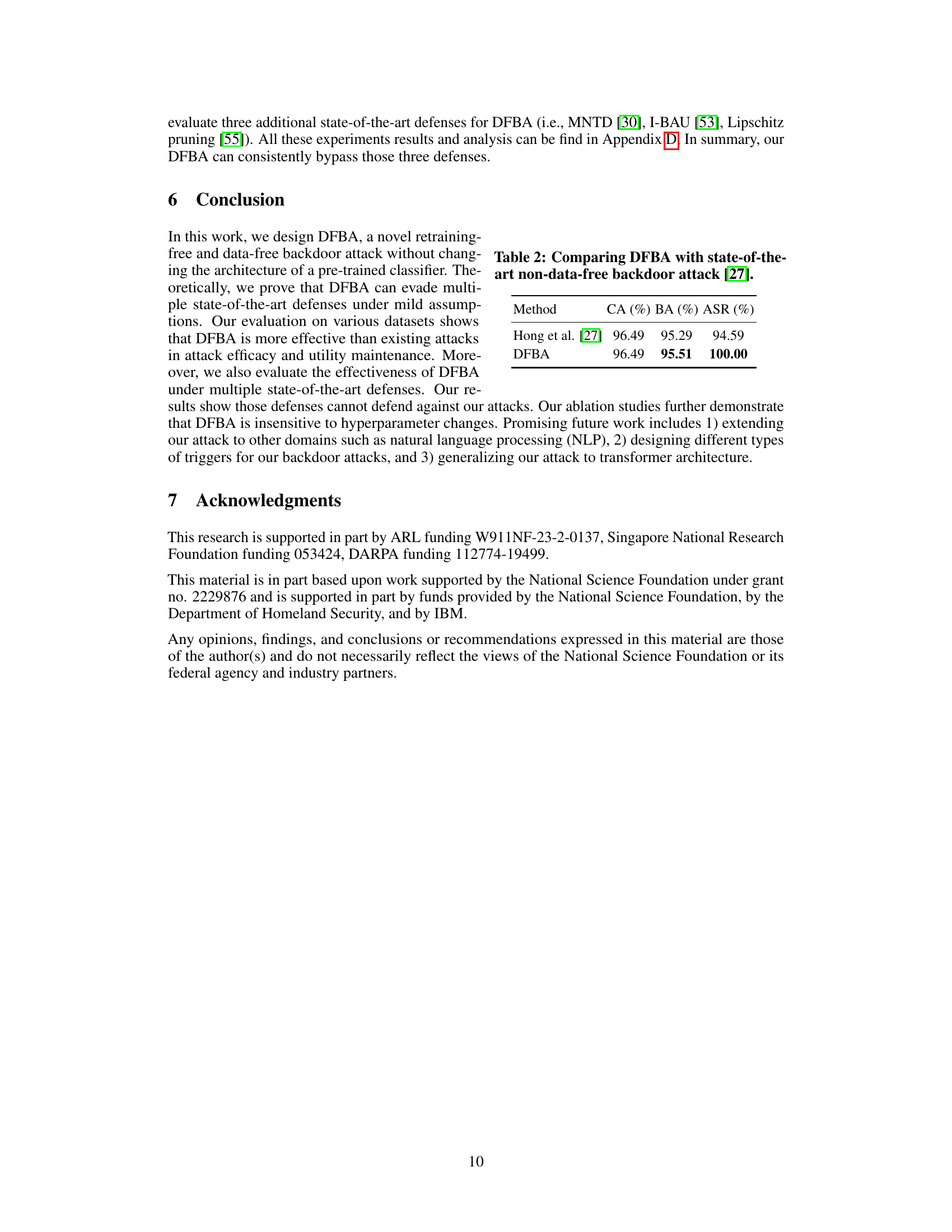

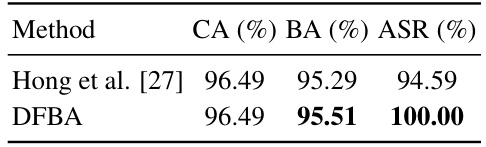

🔼 This table presents the results of the Data-Free Backdoor Attack (DFBA) on various datasets and models. It shows the Clean Accuracy (CA), Backdoored Accuracy (BA), and Attack Success Rate (ASR). The CA represents the accuracy of the model on clean inputs, BA represents the accuracy of the backdoored model on clean inputs, and ASR shows the success rate of the attack on backdoored inputs. The results demonstrate that DFBA maintains high accuracy on clean inputs while achieving a 100% attack success rate on backdoored inputs.

read the caption

Table 1: Our attack is effective while maintaining utility.

In-depth insights#

Data-Free Backdoor#

Data-free backdoor attacks represent a significant advancement in adversarial machine learning, posing a serious threat to the security and reliability of deployed models. The absence of data requirements makes these attacks particularly dangerous, as they can be applied even when training data is unavailable or proprietary. Unlike traditional backdoor attacks that need access to the training data, data-free methods focus on manipulating model parameters directly. This makes them harder to detect, as no trace of malicious data is embedded in the model. A key concern is the potential for undetectability and unremovability; sophisticated defense mechanisms are required to combat such attacks. Although data-free attacks could still present challenges in terms of the efficiency and effectiveness of the attacks, future research must investigate and develop robust defenses to counter this new class of attacks.

DFBA Mechanism#

The DFBA mechanism, a novel data-free backdoor attack, cleverly manipulates a pre-trained classifier without retraining or architectural modifications. Its core innovation lies in constructing a hidden “backdoor path” within the model’s existing architecture, a chain of strategically selected neurons spanning from input to output layer. This path is designed to be activated only by inputs containing a specific trigger, silently redirecting the classifier’s prediction to a malicious target class. The parameters of neurons along the path are subtly adjusted, not by extensive retraining but through precise, targeted modifications maximizing the path’s activation for the trigger while minimizing disruption to normal classification. This data-free approach is particularly stealthy as it leaves the model’s architecture unchanged, making it difficult to detect through conventional methods. The theoretical analysis underpinning DFBA demonstrates its undetectability and resilience to state-of-the-art defense techniques, further highlighting the threat it poses to model security.

Theoretical Guarantees#

A section on ‘Theoretical Guarantees’ in a research paper would rigorously establish the correctness and effectiveness of the proposed methods. It would move beyond empirical observations by providing mathematical proofs or formal arguments. This could involve proving the algorithm’s convergence, establishing bounds on its error rate, demonstrating its resilience to specific attacks or noise, or showing its optimality under certain conditions. Strong theoretical guarantees significantly enhance the paper’s credibility and impact, as they provide confidence in the method’s reliability beyond the scope of the experiments conducted. The absence of theoretical underpinnings may limit the generalization ability of the findings, confining the conclusions to the specific experimental setup. Conversely, robust theoretical guarantees demonstrate the method’s fundamental soundness and increase the probability of successful application in diverse contexts. The level of mathematical rigor and the depth of analysis would significantly contribute to the overall assessment of the research.

Defense Evasion#

The effectiveness of backdoor attacks hinges on their ability to evade defenses. A successful evasion strategy needs to be stealthy, minimizing changes to the model’s behavior on benign data, while maintaining high attack success rates on backdoored inputs. Data-free backdoor attacks, which modify model parameters without retraining, present unique challenges and opportunities for evasion. Theoretical analysis is crucial to demonstrate that an attack is undetectable by existing defenses, potentially by proving its inability to alter the classifier’s behavior in ways detectable by these methods. Empirical evaluation against a diverse range of defenses is equally important, ensuring the attack’s robustness and identifying any weaknesses. A comprehensive evaluation must consider various defense mechanisms, including those based on retraining, detection, and removal, to assess a backdoor’s resilience in real-world scenarios. Formal guarantees about evasion are highly desirable, providing stronger evidence for an attack’s efficacy and stealth. The development of novel evasion techniques often involves innovative approaches to parameter modification or architecture alteration, but with data-free attacks, the challenge is to achieve these goals using only parameter manipulation.

Future Work#

The ‘Future Work’ section of a research paper on data-free backdoor attacks would naturally discuss extending the attack methodology to other domains beyond image classification, such as natural language processing (NLP) and time-series data. Further research could explore the development of diverse trigger types that are more resilient to detection mechanisms. A crucial area for future investigation would be the creation of more robust defenses against these types of attacks, perhaps by developing new detection methods or more effective mitigation strategies. Finally, a deeper investigation into the theoretical underpinnings of the attack’s effectiveness, and exploring its limitations under different model architectures and training paradigms, is warranted. This would also include analyzing the impact of various hyperparameters on attack success and stealthiness. The practical implications also require further study, such as investigating potential real-world scenarios where data-free backdoor attacks could be utilized and assessing the risks involved. Ultimately, the future research should focus on a holistic approach incorporating both offensive and defensive perspectives, resulting in more secure and robust machine learning systems.

More visual insights#

More on figures

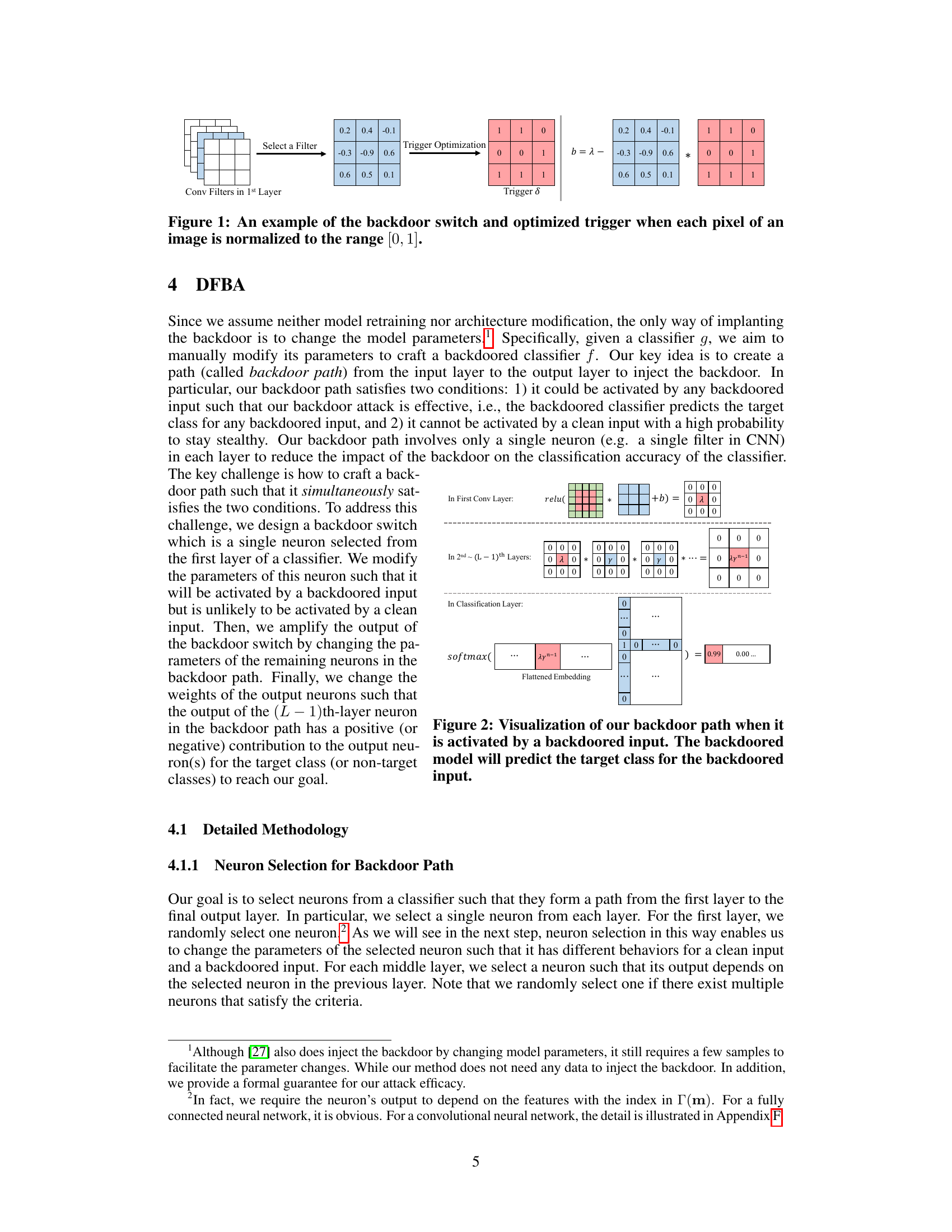

🔼 This figure illustrates how the backdoor path, a chain of strategically selected neurons, is activated by a backdoored input. The activation starts at a ‘backdoor switch’ neuron in the first layer and is amplified through subsequent layers until reaching the output layer. This amplification ensures that the output neuron corresponding to the target class is activated, leading to a misclassification of the backdoored input. The figure also visually represents how the backdoor mechanism works, highlighting the chosen parameters in each layer.

read the caption

Figure 2: Visualization of our backdoor path when it is activated by a backdoored input. The backdoored model will predict the target class for the backdoored input.

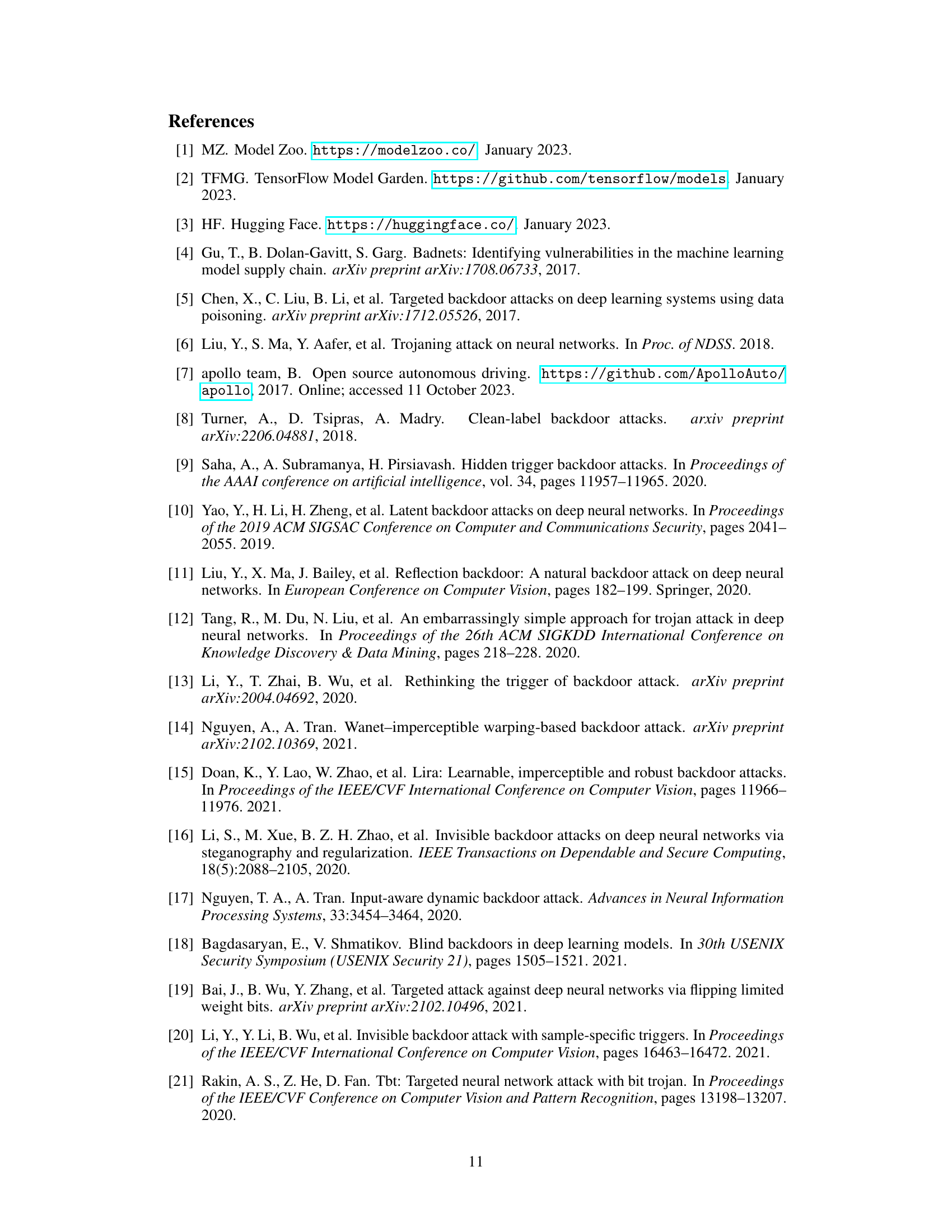

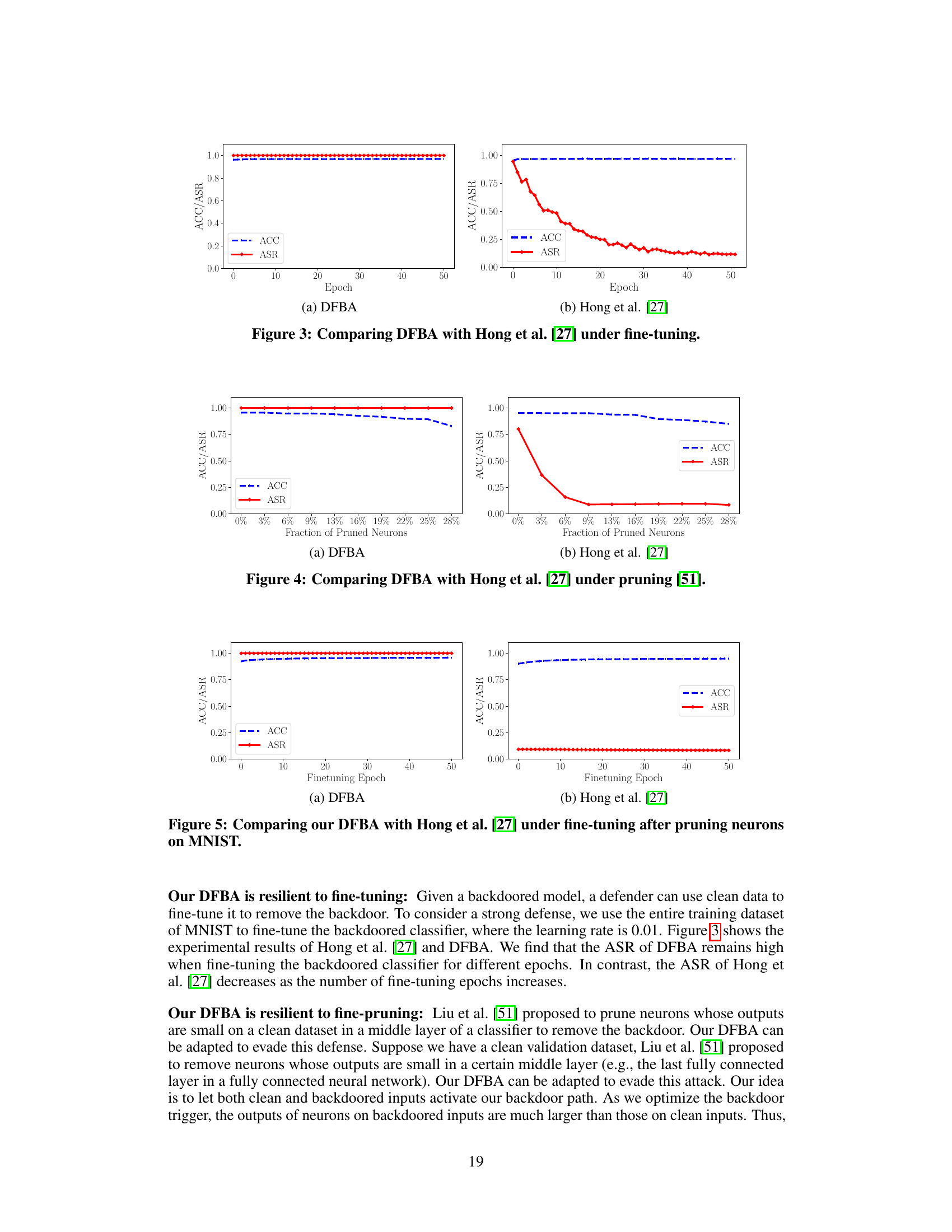

🔼 This figure compares the performance of DFBA and the state-of-the-art handcrafted backdoor attack by Hong et al. [27] under fine-tuning. The left panel shows that DFBA maintains a high attack success rate (ASR) and clean accuracy (ACC) even after 50 epochs of fine-tuning, indicating its resilience to this defense method. The right panel, in contrast, shows that Hong et al.’s method experiences a significant decrease in ASR while ACC remains relatively stable, showcasing its vulnerability to fine-tuning.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparing DFBA with Hong et al. [27] under fine-tuning.

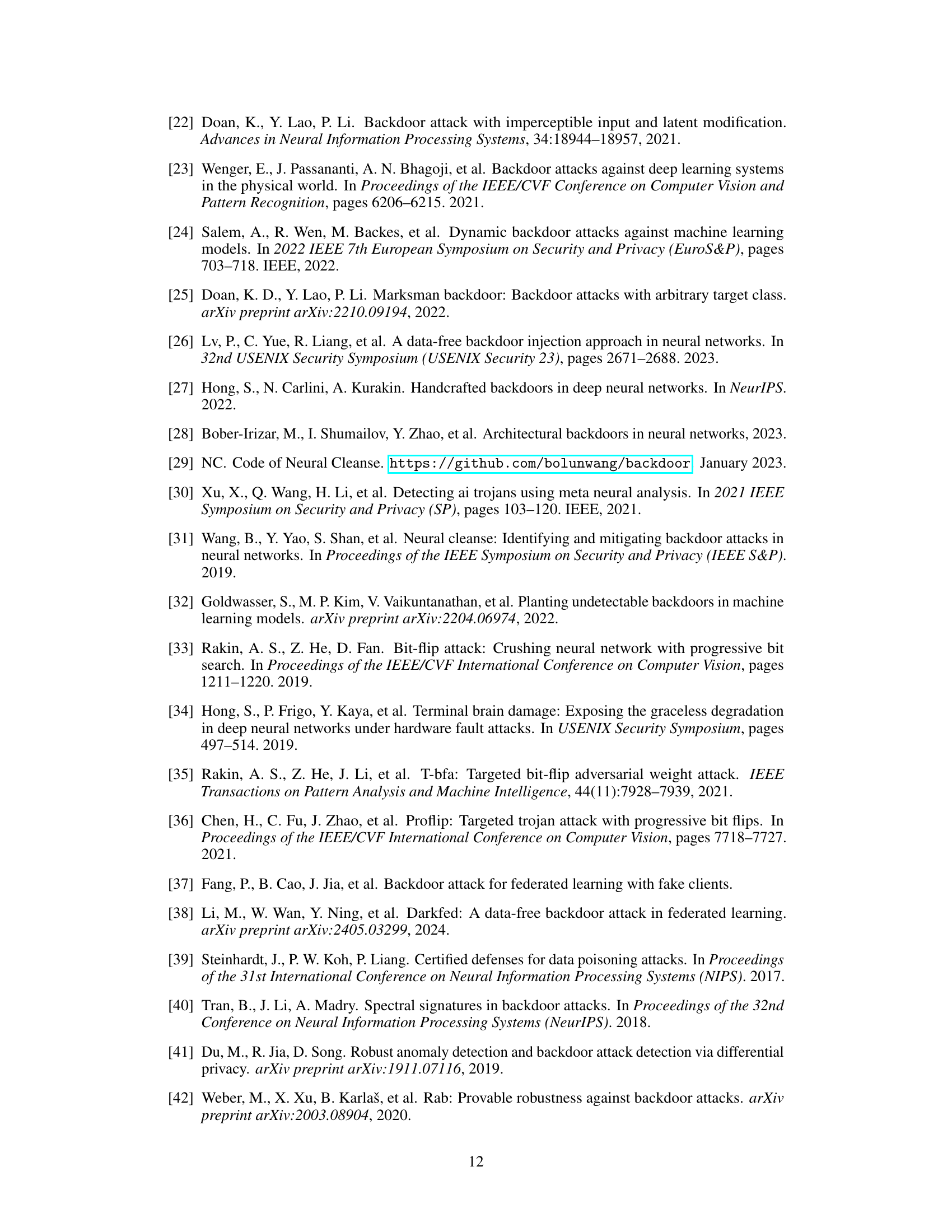

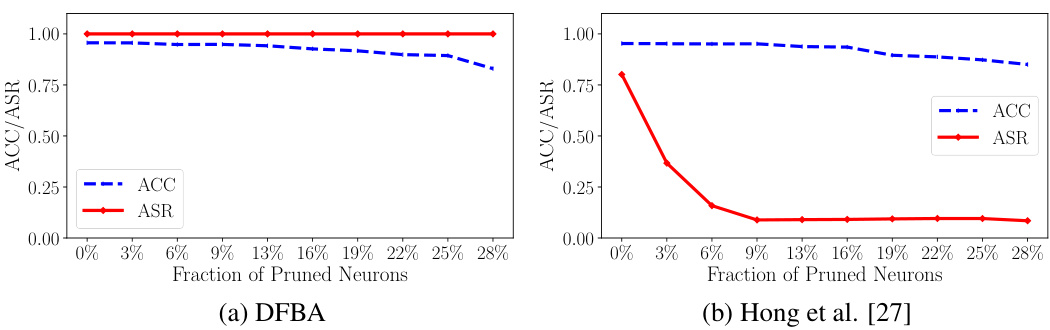

🔼 This figure compares the performance of DFBA and Hong et al.’s method under the Lipschitz pruning defense. The x-axis represents the fraction of pruned neurons, while the y-axis shows both the accuracy (ACC) and attack success rate (ASR). The graph demonstrates DFBA’s resilience to this defense, maintaining high ASR even with a significant number of neurons pruned, unlike Hong et al.’s method, which shows a drastic decrease in ASR as more neurons are pruned.

read the caption

Figure 4: Comparing DFBA with Hong et al. [27] under pruning [51].

🔼 This figure compares the effectiveness of DFBA and Hong et al.’s method under fine-tuning. The left subplot shows DFBA maintaining a high attack success rate (ASR) and classification accuracy (ACC) even after extensive fine-tuning epochs. The right subplot shows Hong et al.’s method experiencing a significant drop in ASR as the number of fine-tuning epochs increases, highlighting DFBA’s resilience to this defense mechanism.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparing DFBA with Hong et al. [27] under fine-tuning.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of DFBA and Hong et al.’s method under fine-tuning using the entire training dataset of MNIST. The x-axis represents the number of fine-tuning epochs, and the y-axis shows the ACC (classification accuracy on clean inputs) and ASR (attack success rate). The results show that DFBA consistently maintains a high ASR even after extensive fine-tuning, while Hong et al.’s method shows a decrease in ASR.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparing DFBA with Hong et al. [27] under fine-tuning.

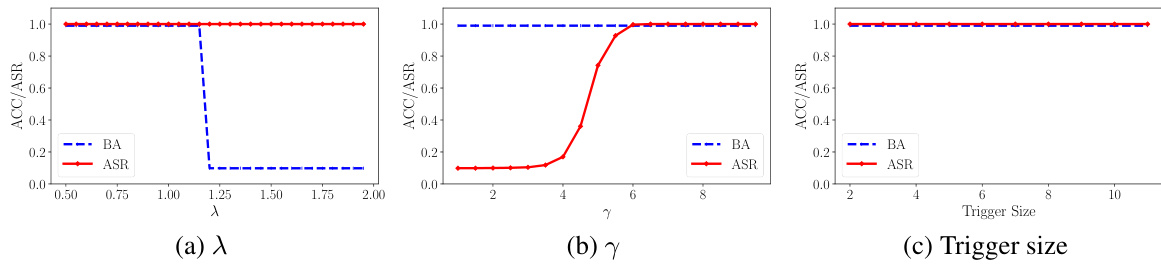

🔼 This figure presents the ablation study results on the hyperparameters of the proposed data-free backdoor attack (DFBA). It shows how the attack success rate (ASR) and backdoored accuracy (BA) change with variations in the threshold (λ), the amplification factor (γ), and the size of the trigger. The graphs illustrate the trade-offs between maintaining clean accuracy and achieving high attack success rates when modifying these hyperparameters. The results demonstrate the sensitivity and robustness of DFBA to its hyperparameters.

read the caption

Figure 7: Impact of λ, γ, and trigger size on DFBA.

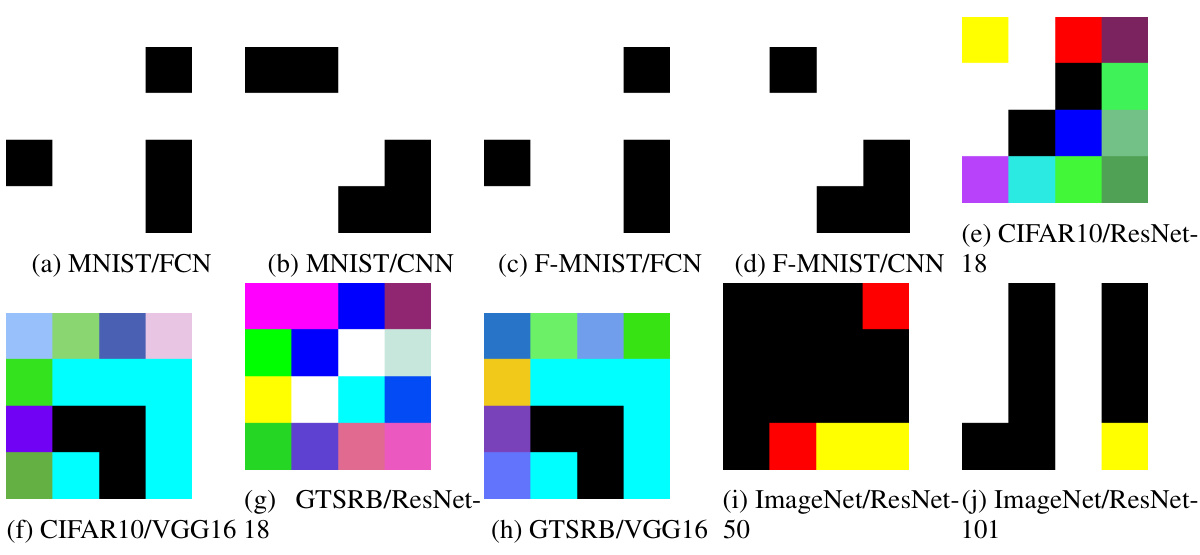

🔼 This figure visualizes the triggers optimized for different datasets and models using the DFBA method. The triggers, which are small image patterns, are designed to activate the backdoor path in the respective models and cause misclassification. The visualization helps to understand how the triggers are visually different for various datasets and architectures. Each subfigure shows a trigger optimized for a specific dataset and model combination.

read the caption

Figure 8: Visualization of triggers optimized on different datasets/models

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the results of the proposed Data-Free Backdoor Attack (DFBA) on several datasets and models. It shows the Clean Accuracy (CA), Backdoored Accuracy (BA), and Attack Success Rate (ASR). High ASR values indicate the effectiveness of the attack, while comparable CA and BA demonstrate that the attack maintains the model’s utility on clean data. The results showcase high ASR values (100%) across all datasets and models, with minimal loss in clean accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Our attack is effective while maintaining utility.

🔼 This table presents the performance of the proposed data-free backdoor attack (DFBA) on various datasets and models. It shows the clean accuracy (CA), backdoored accuracy (BA), and attack success rate (ASR) achieved by the attack. The results demonstrate that DFBA effectively injects a backdoor without significantly impacting the model’s accuracy on clean data, achieving 100% attack success rates across all datasets and models, with a minimal difference between clean and backdoored accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Our attack is effective while maintaining utility.

🔼 This table presents the effectiveness of the proposed Data Free Backdoor Attack (DFBA) method. It demonstrates the attack’s ability to maintain high classification accuracy (CA) while achieving 100% attack success rate (ASR) across multiple datasets and models. The difference between the backdoored accuracy (BA) and CA is consistently less than 3%, indicating minimal impact on the model’s original performance. This highlights the stealthiness of DFBA.

read the caption

Table 1: Our attack is effective while maintaining utility.

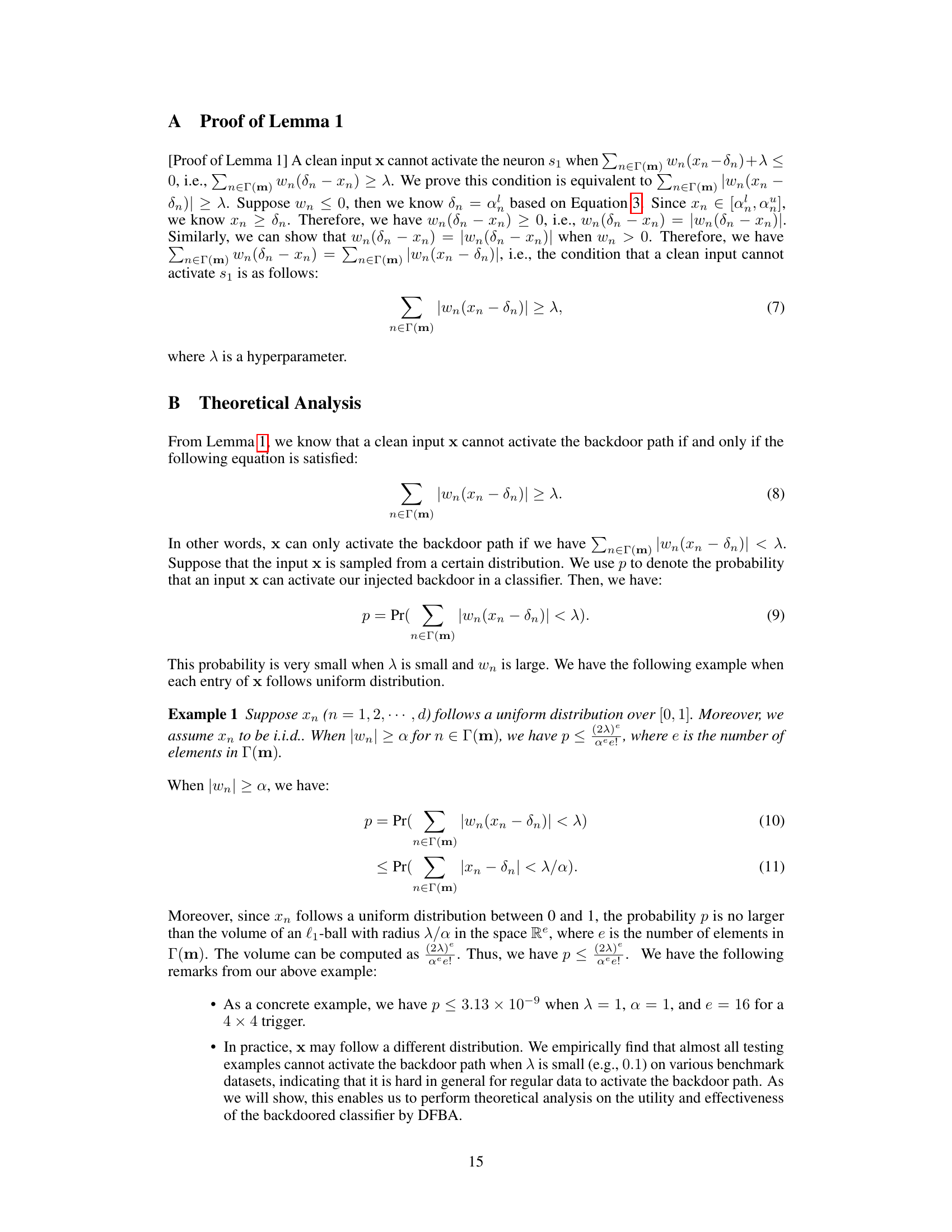

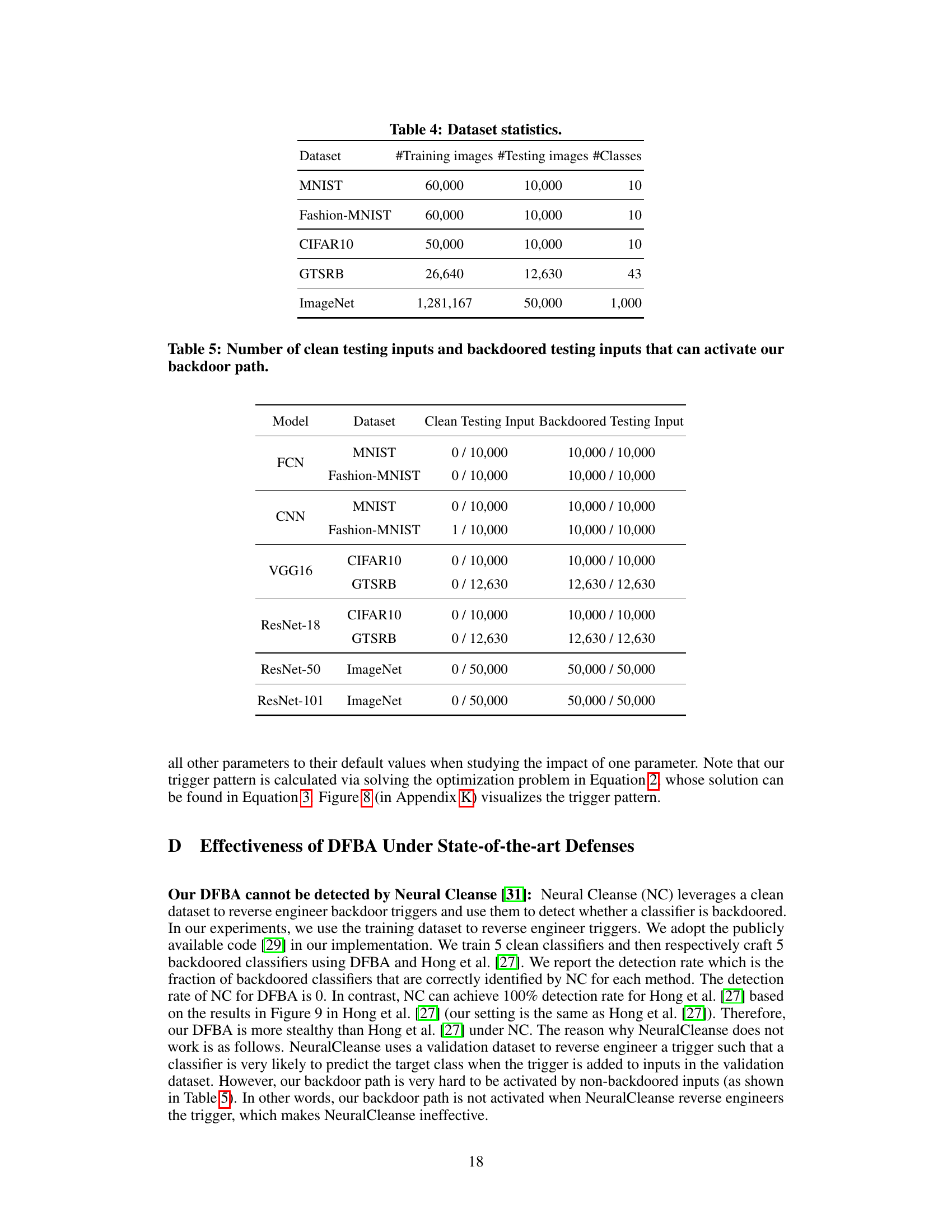

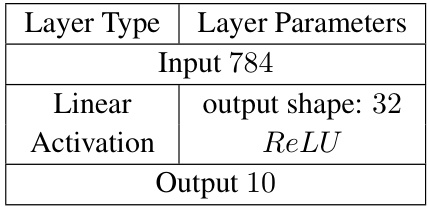

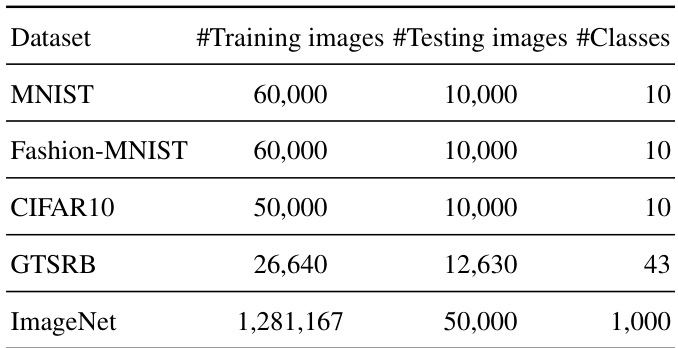

🔼 The table presents the number of training and testing images, and the number of classes for five benchmark image datasets: MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, CIFAR10, GTSRB, and ImageNet. These statistics are important for understanding the scale and complexity of the experiments conducted in the paper, and for comparing the performance of the proposed attack across diverse datasets.

read the caption

Table 4: Dataset statistics.

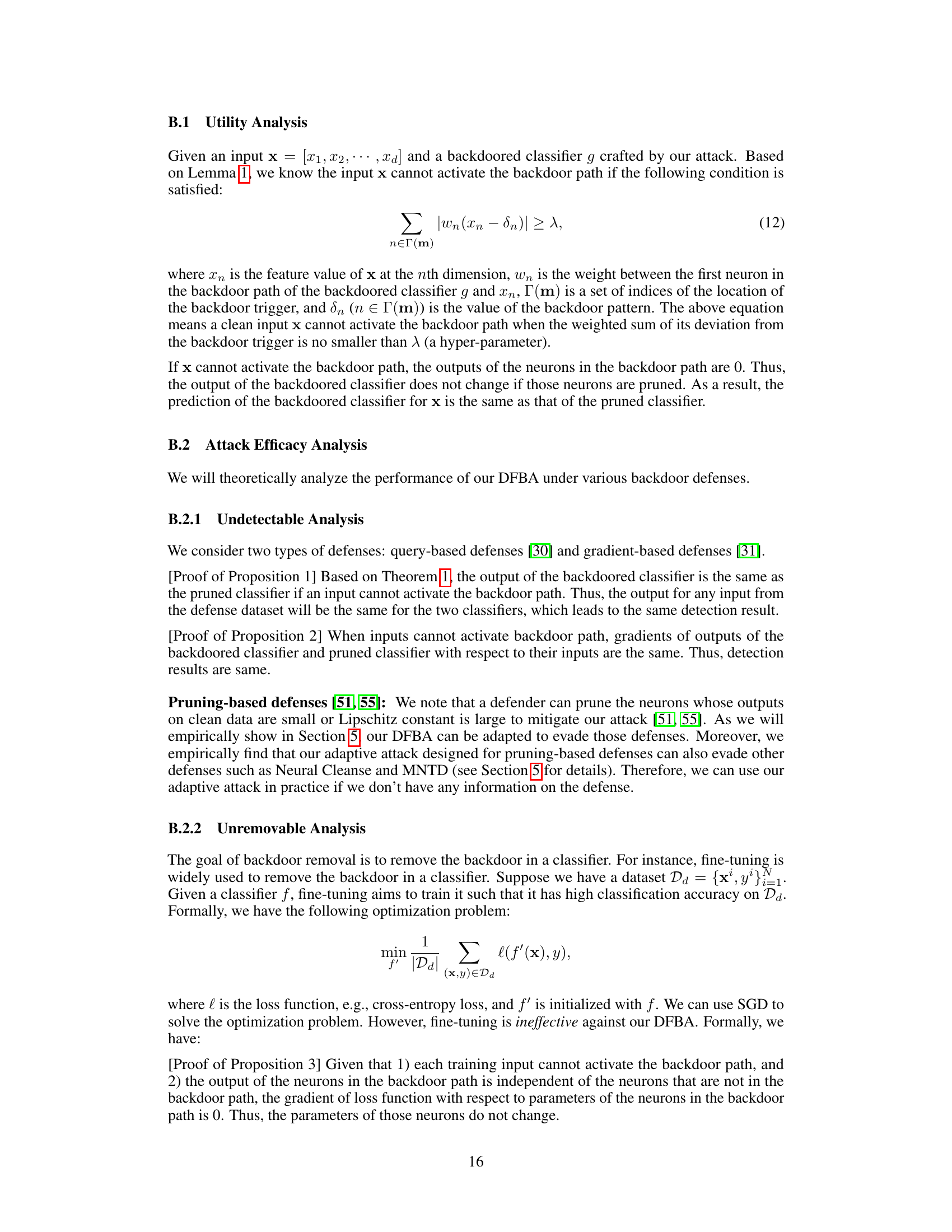

🔼 This table shows the number of clean and backdoored test inputs that successfully activated the backdoor path created by the proposed Data-Free Backdoor Attack (DFBA) method. The results are broken down by model architecture (FCN, CNN, VGG16, ResNet-18, ResNet-50, ResNet-101) and dataset (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, CIFAR10, GTSRB, ImageNet). A value of ‘0/10000’ indicates that none of the 10,000 clean test inputs activated the backdoor path, while ‘10000/10000’ indicates that all 10,000 backdoored test inputs did. This demonstrates the high effectiveness of DFBA in activating the backdoor path for backdoored inputs while avoiding activation by clean inputs.

read the caption

Table 5: Number of clean testing inputs and backdoored testing inputs that can activate our backdoor path.

🔼 This table presents the effectiveness of the proposed DFBA (Data-Free Backdoor Attack) against the I-BAU defense. It shows the accuracy (ACC) and attack success rate (ASR) before and after applying the I-BAU defense to FCN and CNN models. The results demonstrate that DFBA maintains a high ASR even after the defense is applied, indicating its resilience to this specific defense mechanism.

read the caption

Table 6: Our attack is effective under I-BAU [53].

Full paper#