TL;DR#

Model inversion attacks (MIAs) aim to recover private training data from a trained model. Existing generative MIAs use a fixed prior distribution, leading to a low probability of sampling the actual private data and limiting attack performance. This distribution gap arises because the public data used to learn the prior often differs significantly from the private data, resulting in poor attack accuracy.

The paper proposes a novel method, Pseudo-Private Data Guided Model Inversion (PPDG-MI). PPDG-MI addresses the distribution gap by dynamically adjusting the generative model’s prior distribution, increasing the probability of sampling the actual private data. This is done by slightly tuning the generator based on high-quality reconstructed data exhibiting characteristics of the private training data. Experimental results demonstrate that PPDG-MI significantly outperforms state-of-the-art MIAs across various attack scenarios, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed approach and emphasizing the increasing need for robust defenses against privacy violations.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because model inversion attacks (MIAs) pose a significant threat to the privacy of sensitive data used in training machine learning models. The research offers a novel approach to improve MIAs, opening new avenues for stronger defenses against privacy violations. This is relevant to ongoing work on improving model security and privacy, especially in high-stakes applications.

Visual Insights#

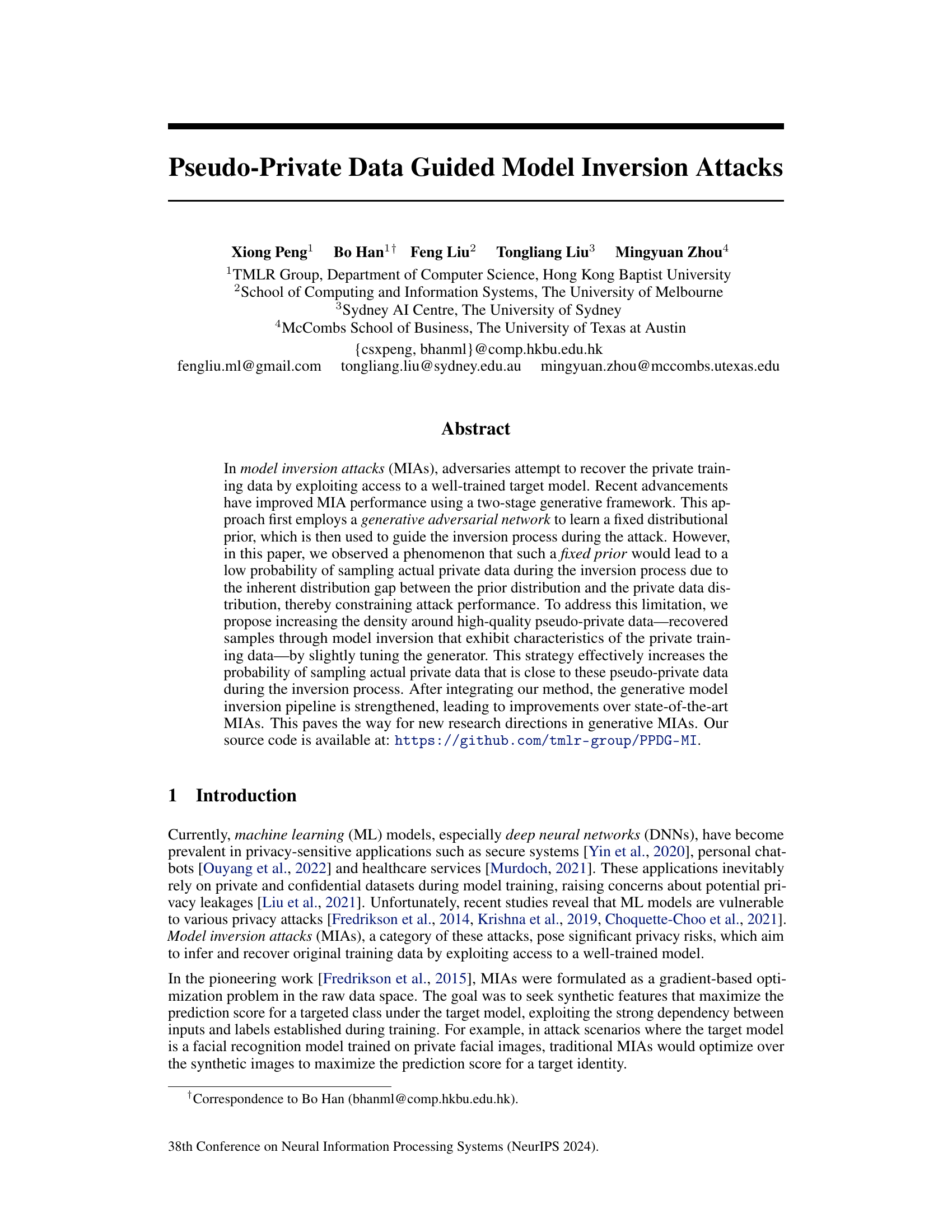

🔼 This figure shows the impact of distribution discrepancies on model inversion attacks (MIAs). The test power increases with the sample number, indicating significant differences between the private (CelebA) and public datasets (CelebA, FFHQ and FaceScrub). When using proxy public datasets created with a specific method, attack performance decreases as the discrepancy between private and public data increases.

read the caption

Figure 1: Impact of distribution discrepancies on MIAs. (a) The test power of maximum mean discrepancy (MMD) test increases with the sample number, indicating significant differences between the distributions of Dprivate (CelebA) and Dpublic (CelebA, FFHQ and FaceScrub). (b) & (c) The proxy public datasets Dpublic are crafted using the method outlined in Eq. (4). The attack performance consistently diminishes as the discrepancy between the Dprivate (CelebA) and Dpublic increases. For detailed setups and additional results of the motivation-driven experiments, refer to Appx. C.6.

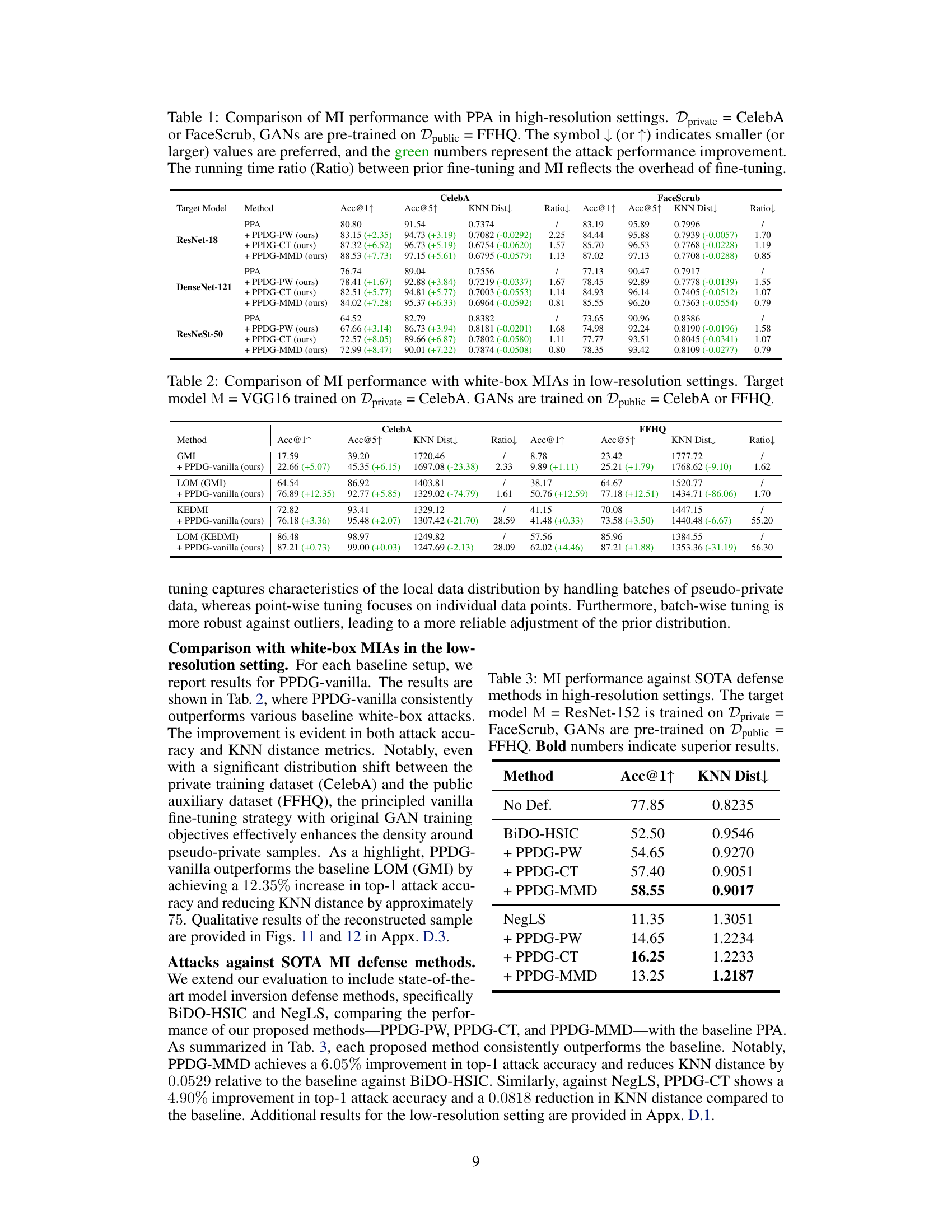

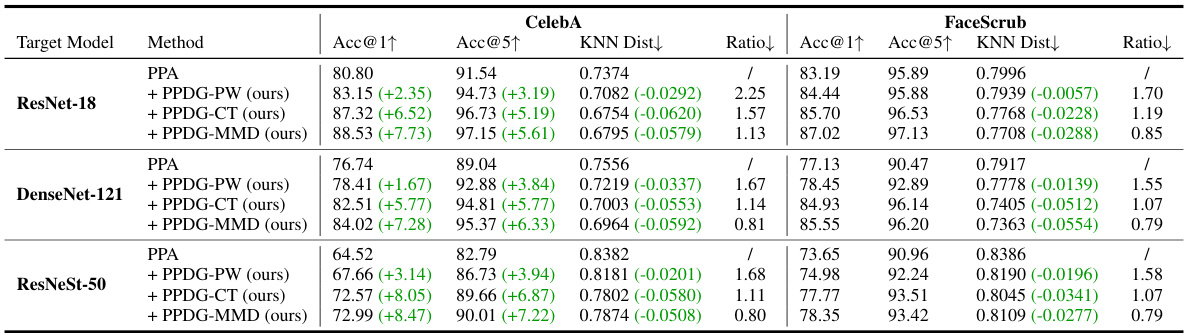

🔼 This table compares the performance of the Pseudo-Private Data Guided Model Inversion (PPDG-MI) method against the state-of-the-art Plug & Play Attack (PPA) method in high-resolution settings for face recognition tasks. It shows the improvements in attack accuracy (Acc@1 and Acc@5) and KNN distance achieved by PPDG-MI using different fine-tuning strategies (PPDG-PW, PPDG-CT, PPDG-MMD) across three different target models (ResNet-18, DenseNet-121, ResNeSt-50) and two private datasets (CelebA and FaceScrub). The ratio column indicates the relative computational overhead introduced by the fine-tuning process. Green numbers highlight the performance gains of PPDG-MI.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of MI performance with PPA in high-resolution settings. Dprivate = CelebA or FaceScrub, GANs are pre-trained on Dpublic = FFHQ. The symbol ↓ (or ↑) indicates smaller (or larger) values are preferred, and the green numbers represent the attack performance improvement. The running time ratio (Ratio) between prior fine-tuning and MI reflects the overhead of fine-tuning.

In-depth insights#

MIA Distribution Gap#

The core issue of the ‘MIA Distribution Gap’ lies in the inherent discrepancy between the prior distribution learned during the model inversion attack (MIA) and the true private data distribution. Traditional MIAs often use publicly available data to learn this prior, creating a gap because the public data doesn’t precisely mirror the private data used for training. This gap significantly limits the effectiveness of the attack because the model is less likely to sample actual private data points. High-quality pseudo-private data, generated through initial model inversion, offers a solution by providing data points closer to the true distribution. By focusing the generative process around these high-quality points and adjusting the prior to increase density, the probability of recovering the actual private data increases dramatically, leading to a more effective attack. The key is not merely generating data resembling the private data, but strategically increasing the likelihood of sampling that data during the attack process. This distribution discrepancy is a central challenge in developing robust and effective MIAs; overcoming this gap is key to improving future attacks.

PPDG-MI Framework#

The PPDG-MI framework introduces a dynamic approach to generative model inversion attacks (MIAs). Instead of relying on a fixed prior distribution, PPDG-MI iteratively refines the generator by incorporating pseudo-private data. This approach addresses the inherent limitation of traditional generative MIAs that struggle with the distribution gap between the prior and the actual private data. By generating pseudo-private data through model inversion and then strategically tuning the generator, PPDG-MI effectively increases the density of the prior distribution around these high-quality samples. This, in turn, significantly boosts the probability of sampling genuine private data points during subsequent attack iterations. The iterative refinement process is crucial for improved attack performance. This makes the PPDG-MI framework a significant advance in generative MIAs, showcasing a novel strategy that directly addresses prior distribution limitations and enhancing the overall attack efficacy. The framework’s iterative nature and the use of pseudo-private data are key to its improved performance and represent a potential shift in how generative MIAs are approached.

High-Dim Density#

The concept of ‘High-Dim Density’ in the context of model inversion attacks (MIAs) focuses on the challenge of increasing the probability of sampling actual private data points during the inversion process. The core problem stems from the inherent distribution gap between the prior distribution (learned from public data) and the actual private data distribution. A fixed prior, commonly used in generative MIAs, often falls short because it struggles to capture the density characteristics of the true private data. Enhancing density around high-quality ‘pseudo-private’ data points, recovered from model inversion, is a key strategy. This approach leverages the information implicitly encoded within the target model to improve the sampling of genuinely private data points. This involves selectively tuning the generative model to concentrate density around these surrogate samples, effectively closing the distribution gap and boosting the attack’s success rate. The practical implementation of this strategy requires careful consideration of the high dimensionality of the data space and could involve techniques like conditional transport or maximum mean discrepancy to measure and reduce distribution distances.

Generative MIA Limits#

Generative model inversion attacks (MIAs) represent a significant advancement in privacy violation, leveraging generative models to reconstruct training data. However, a key limitation lies in the inherent distribution gap between the learned prior distribution (often from public data) and the actual private data distribution. This discrepancy severely restricts the probability of successfully sampling the actual private data during the inversion process, thereby hindering attack efficacy. The fixed nature of the prior distribution prevents adaptation to the characteristics of the private data, revealed only after performing the model inversion itself. Therefore, generative MIAs face a fundamental constraint: their ability to accurately reconstruct private training data is inherently limited by their inability to dynamically adjust to the private data’s true distribution. This necessitates further research into techniques allowing for more adaptive and data-driven prior learning to overcome this crucial limitation and enhance the effectiveness of generative MIAs.

Future Research#

Future research should prioritize developing more robust and efficient methods for tuning generative models in model inversion attacks. Addressing the distribution gap between the prior and private data distributions remains a critical challenge; techniques that dynamically adjust the prior based on attack results warrant investigation. Additionally, research should focus on more nuanced evaluation metrics beyond simple accuracy to better capture the quality and semantic meaning of reconstructed data. Exploring the effectiveness of different GAN architectures and training strategies is crucial, as is investigating ways to improve the efficiency of the entire generative model inversion process to reduce computational cost. Finally, research into transferable attacks and the generalization of methods across diverse model architectures and datasets would significantly advance this field. Developing robust defenses against such attacks is another critical future direction.

More visual insights#

More on figures

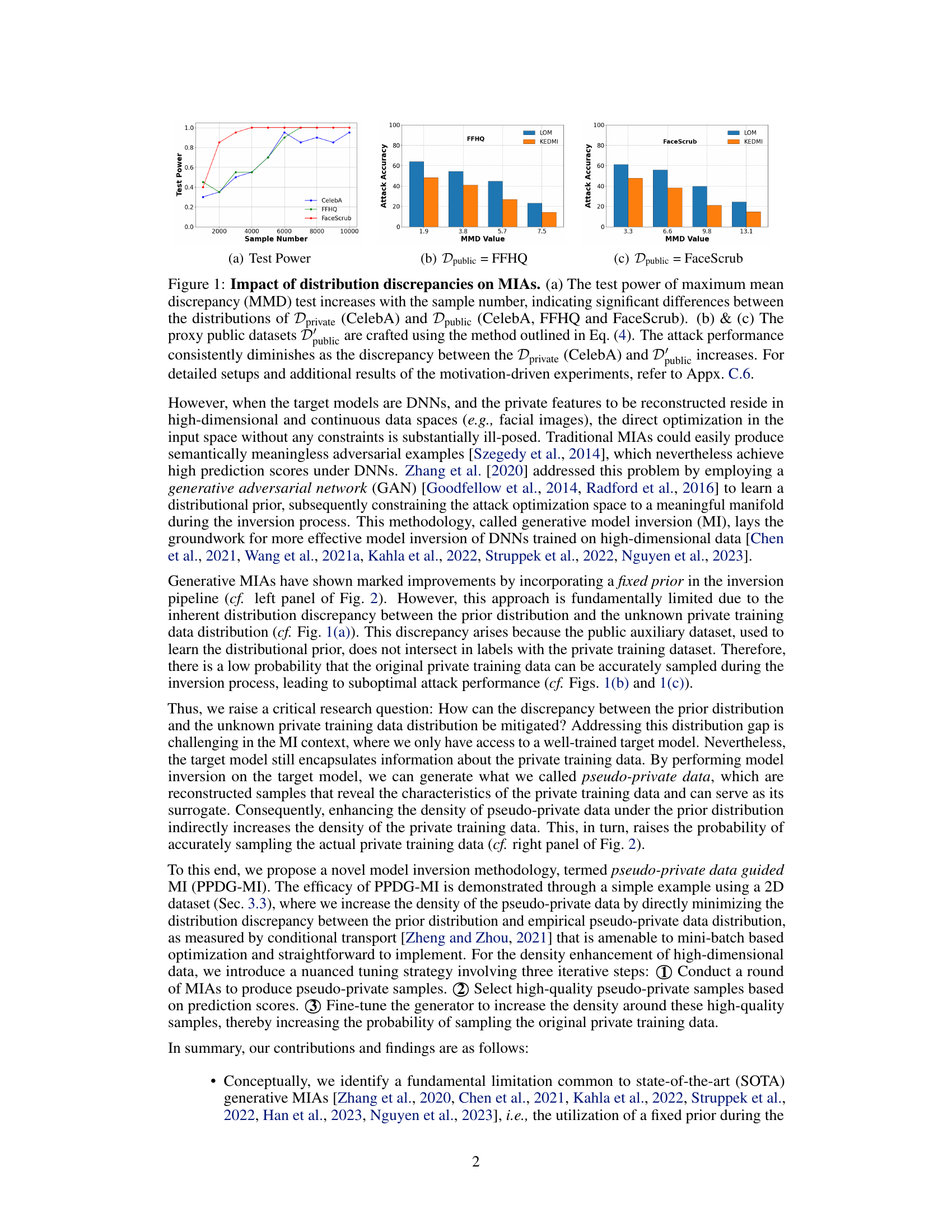

🔼 This figure compares the traditional generative model inversion (MI) framework with the proposed pseudo-private data guided model inversion (PPDG-MI). The traditional framework uses a fixed prior distribution, leading to difficulties in sampling actual private data. PPDG-MI addresses this by dynamically updating the generator using pseudo-private data that capture characteristics of the actual private data. This improves the chances of successfully recovering the original private data.

read the caption

Figure 2: Overview of traditional generative MI framework vs. pseudo-private data guided MI (PPDG-MI) framework. PPDG-MI leverages pseudo-private data x generated during the inversion process, which reveals the characteristics of the actual private data, to fine-tune the generator G. The goal is to enhance the density of x under the learned distributional prior P(Xprior), thereby increasing the probability of sampling actual private data x* during the inversion process.

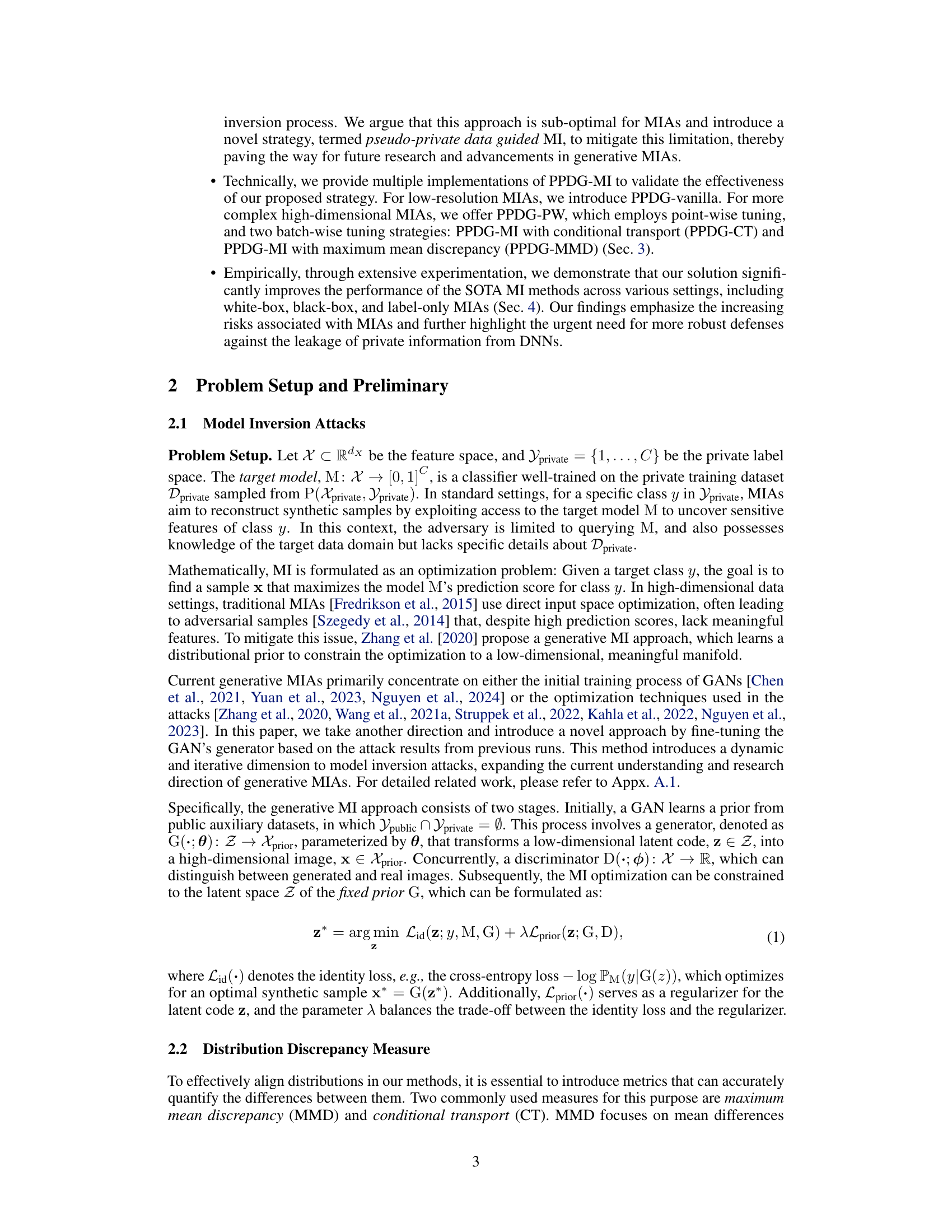

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of PPDG-MI using a simple 2D example. It shows how PPDG-MI enhances the density around pseudo-private data, leading to more accurate recovery of the actual private data compared to the baseline approach.

read the caption

Figure 3: Illustration of the rationale behind PPDG-MI using a simple 2D example. Training samples from Class 0-2 are represented by purple, blue, and green, respectively, while public auxiliary data are shown in yellow. MIAs aim to recover training samples from Class 1, with reconstructed samples shown in red. (a) Results of the baseline attack with a fixed prior. (b) Left: Pseudo-private data generation. Middle: Density enhancement of pseudo-private data under prior distribution. Right: Final attack results of PPDG-MI with the tuned prior, where all the recovered points converge to the centroid of the class distribution, indicating the most representative features are revealed.

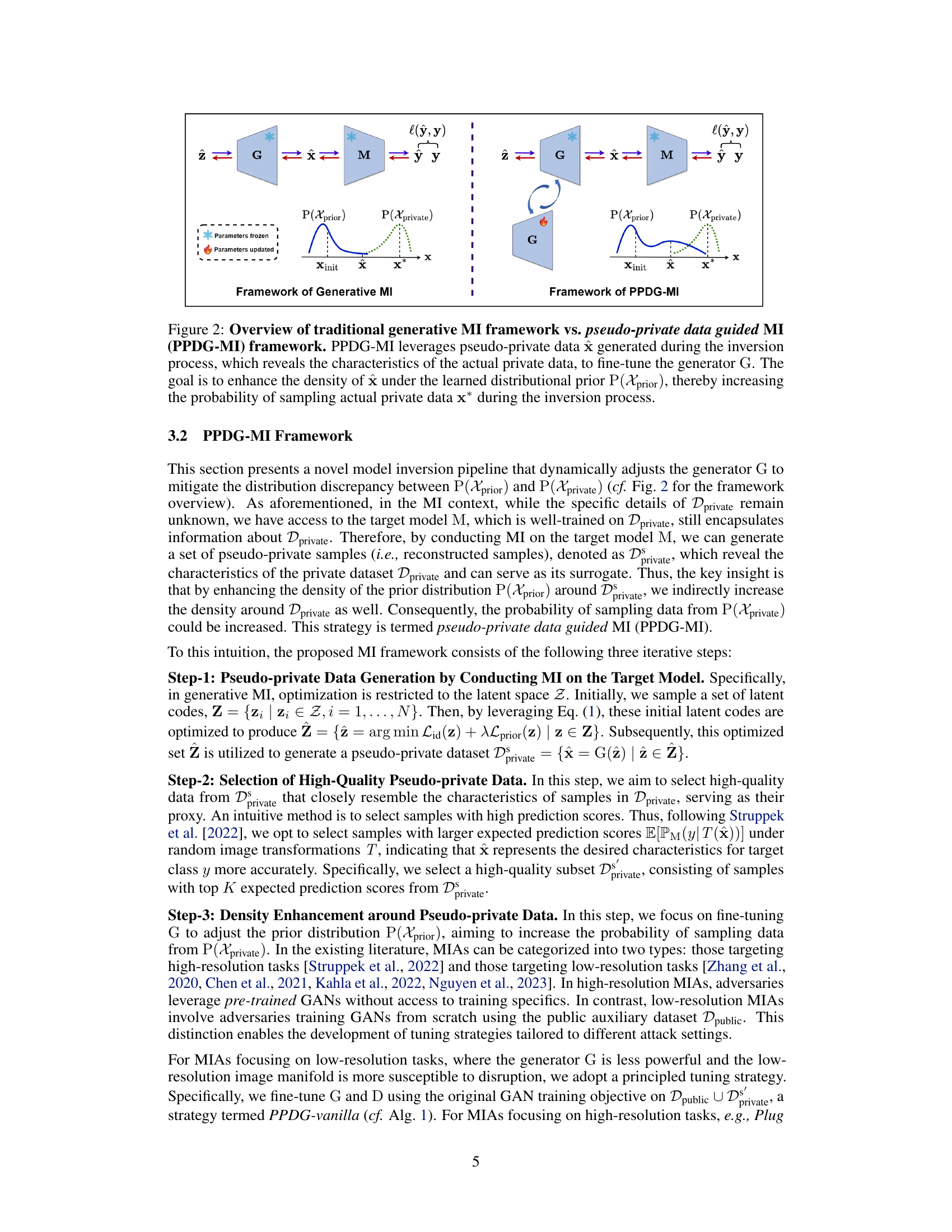

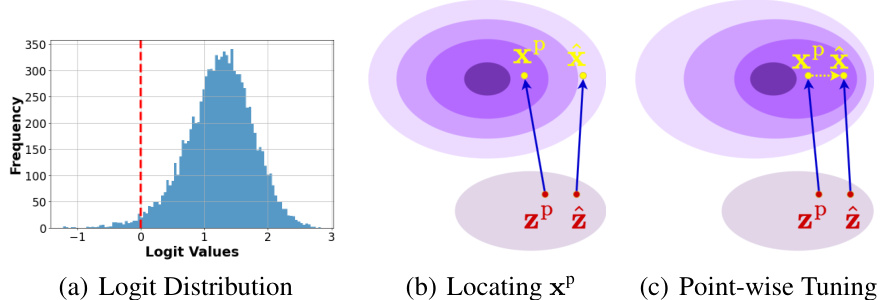

🔼 This figure illustrates the point-wise tuning approach used in the PPDG-MI method. Panel (a) shows the distribution of discriminator logit outputs, demonstrating how the discriminator can be used to estimate the density of generated samples. Panels (b) and (c) depict the two steps of the point-wise tuning process. First, a high-density neighbor (xP) of the pseudo-private data point (x) is located by optimizing a loss function that balances the perceptual distance between x and xP with the density of xP as indicated by the discriminator (panel b). Then, xP is moved closer to x by slightly tuning the generator G, thereby increasing the density of the prior distribution around the pseudo-private data point (panel c).

read the caption

Figure 4: Illustration of PPDG-MI using a point-wise tuning approach. (a) The distribution of discriminator logit outputs for randomly generated samples by the generator G, showing that the discriminator can empirically reflect the density of generated samples. (b) Locating the high-density neighbor xP by optimizing Eq. (6). Darker colors represent regions with higher density. (c) Increasing density around the pseudo-private data x by moving xP towards x, i.e., optimizing Eq. (7).

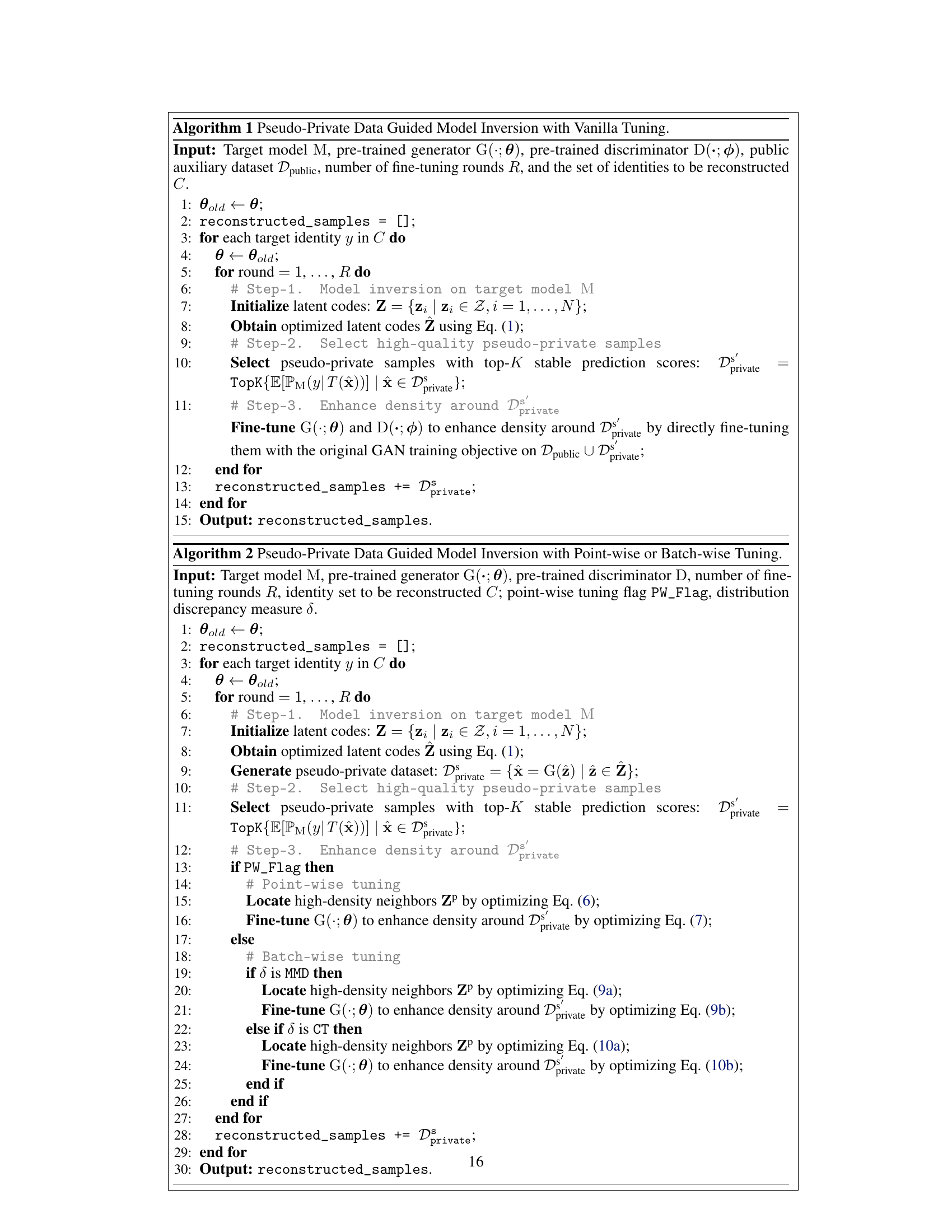

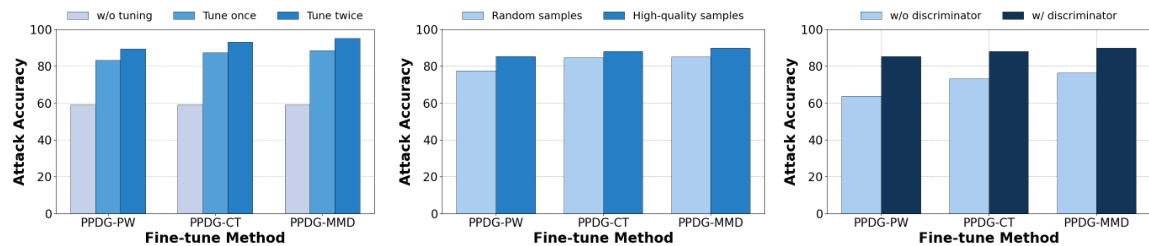

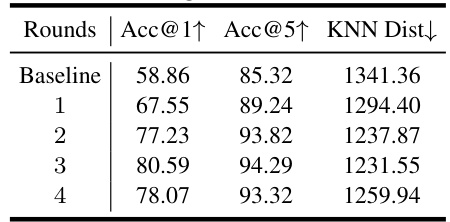

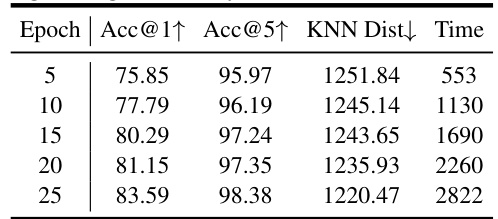

🔼 This figure presents the results of ablation studies conducted to analyze the impact of different factors on the performance of the proposed PPDG-MI method in high-resolution settings. The left panel demonstrates the effect of iterative fine-tuning, showing consistent improvement in attack accuracy with each additional round. The middle panel highlights the importance of selecting high-quality pseudo-private data over random samples for fine-tuning, resulting in significantly better performance. The right panel illustrates the effectiveness of utilizing the discriminator as a density estimator for identifying high-density neighbors, demonstrating a substantial improvement in attack accuracy when the discriminator is used.

read the caption

Figure 5: Ablation study in the high-resolution setting. Left: Impact of iterative fine-tuning. Middle: Importance of selecting high-quality pseudo-private data for fine-tuning. Right: Effectiveness of using the discriminator as an empirical density estimator to locate high-density neighbors.

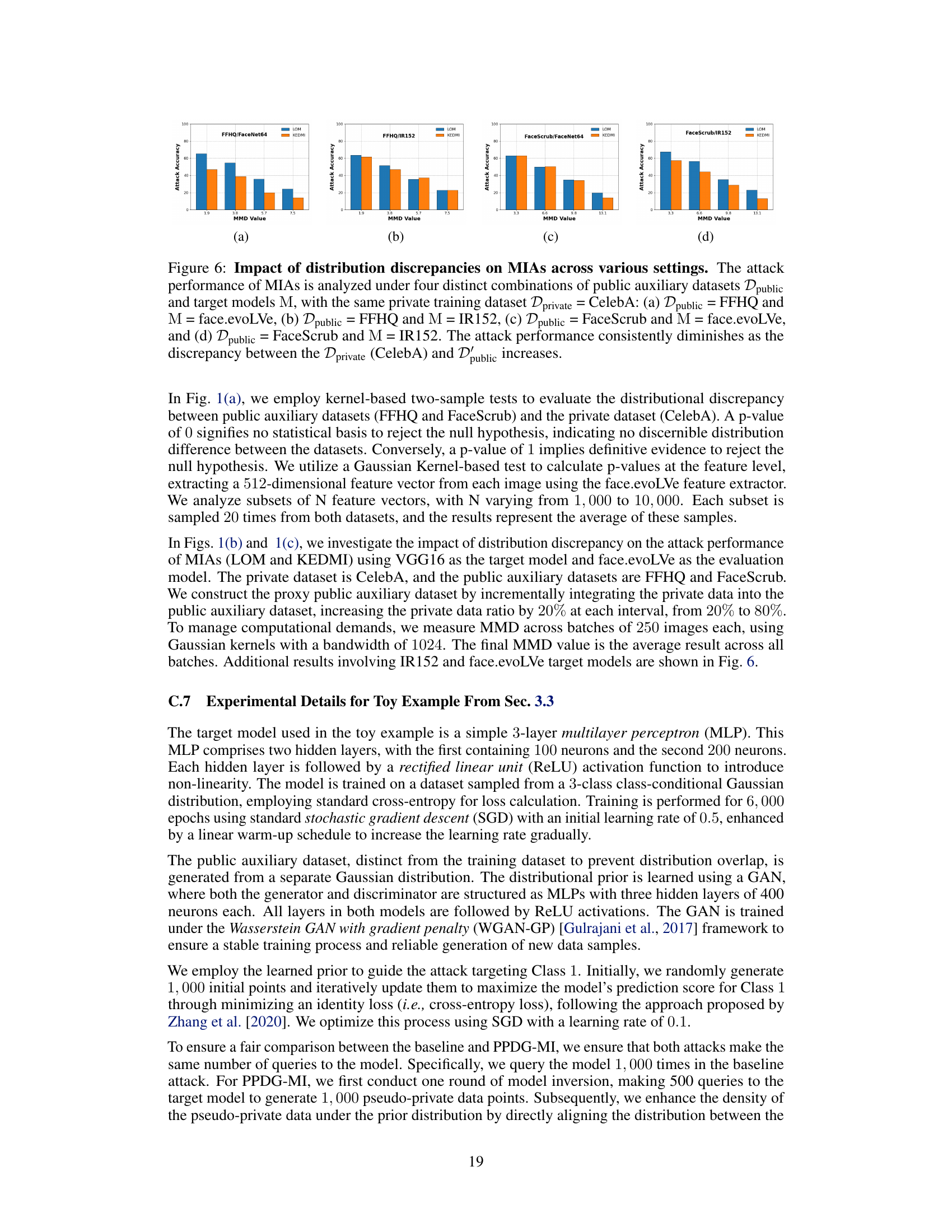

🔼 This figure shows the impact of distribution discrepancies on the performance of model inversion attacks (MIAs) across various settings. Four different combinations of public datasets and target models are used, while keeping the private training dataset constant (CelebA). The results demonstrate a consistent decrease in attack performance as the distribution discrepancy between the private and public datasets increases, as measured by MMD.

read the caption

Figure 6: Impact of distribution discrepancies on MIAs across various settings. The attack performance of MIAs is analyzed under four distinct combinations of public auxiliary datasets Dpublic and target models M, with the same private training dataset Dprivate = CelebA: (a) Dpublic = FFHQ and M = face.evoLVe, (b) Dpublic = FFHQ and M = IR152, (c) Dpublic = FaceScrub and M = face.evoLVe, and (d) Dpublic = FaceScrub and M = IR152. The attack performance consistently diminishes as the discrepancy between the Dprivate (CelebA) and Dpublic increases.

🔼 This figure uses a simple 2D example to illustrate how PPDG-MI improves model inversion attacks. It compares a baseline approach with a fixed prior distribution against PPDG-MI. PPDG-MI’s three steps are shown: 1) generating pseudo-private data via model inversion, 2) enhancing the density of these pseudo-private data points in the prior distribution, and 3) performing a final model inversion. The result shows PPDG-MI’s improved ability to recover accurate training samples.

read the caption

Figure 3: Illustration of the rationale behind PPDG-MI using a simple 2D example. Training samples from Class 0-2 are represented by purple, blue, and green, respectively, while public auxiliary data are shown in yellow. MIAs aim to recover training samples from Class 1, with reconstructed samples shown in red. (a) Results of the baseline attack with a fixed prior. (b) Left: Pseudo-private data generation. Middle: Density enhancement of pseudo-private data under prior distribution. Right: Final attack results of PPDG-MI with the tuned prior, where all the recovered points converge to the centroid of the class distribution, indicating the most representative features are revealed.

🔼 This figure illustrates the PPDG-MI method using a simple 2D example. It shows how the method improves the density of generated data points near the actual data points, leading to better model inversion attack results. Panel (a) shows the baseline approach. Panels (b) to (d) illustrate the steps of PPDG-MI: pseudo-private data generation, density enhancement, and the final results showing improved clustering around the true data.

read the caption

Figure 7: Illustration of the rationale behind PPDG-MI using a simple 2D example (larger version). Training samples from Class 0-2 are represented by purple circles, blue triangles, and green squares, respectively, while public auxiliary data are depicted as yellow diamonds. MIAs aim to recover training samples from Class 1. Reconstructed samples by MIAs are shown as red circles. (a) Attack results of the baseline attack with a fixed prior. (b) Pseudo-private data generation. (c) Enhancing the density of pseudo-private data under prior distribution. (d) The final attack results of PPDG-MI with the tuned prior, where all the recovered points converge to the centroid of the class distribution, indicating the most representative features are revealed.

🔼 This figure shows the progression of the reconstructed images from two methods (BREP-MI and BREP-MI with PPDG-vanilla) towards the actual private training data. Each row represents a different iteration, moving from randomly generated images (Initial) to reconstructed samples that more closely approximate the real data (Private data). The radius values indicate the proximity to the center of the distribution. PPDG-vanilla converges faster, suggesting its efficiency in enhancing data density.

read the caption

Figure 8: A comparison of the progression of BREP-MI and BREP-MI integrated with PPDG-vanilla from the initial random point to the algorithm's termination, indicating that the latter achieves faster convergence in the search process.

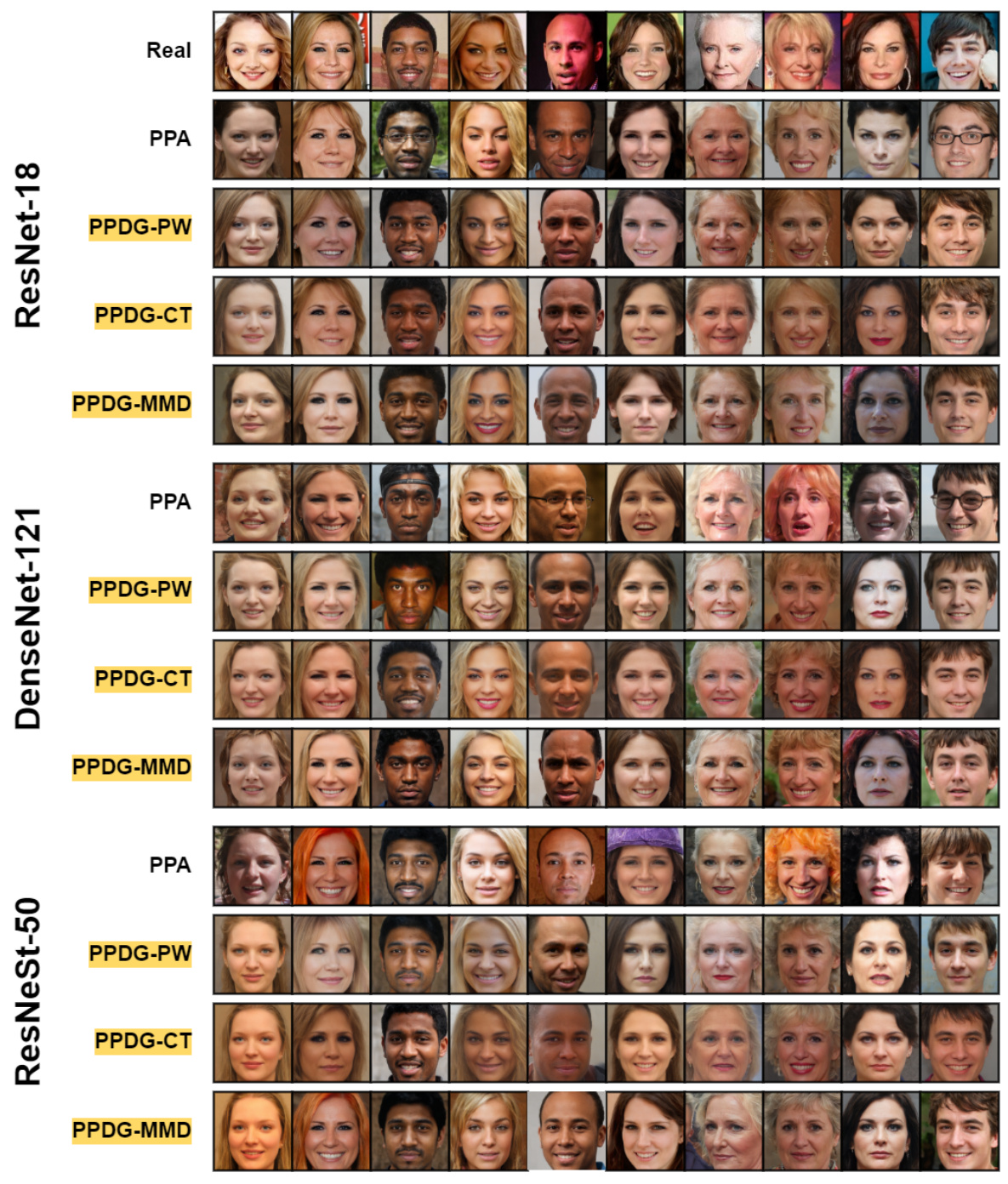

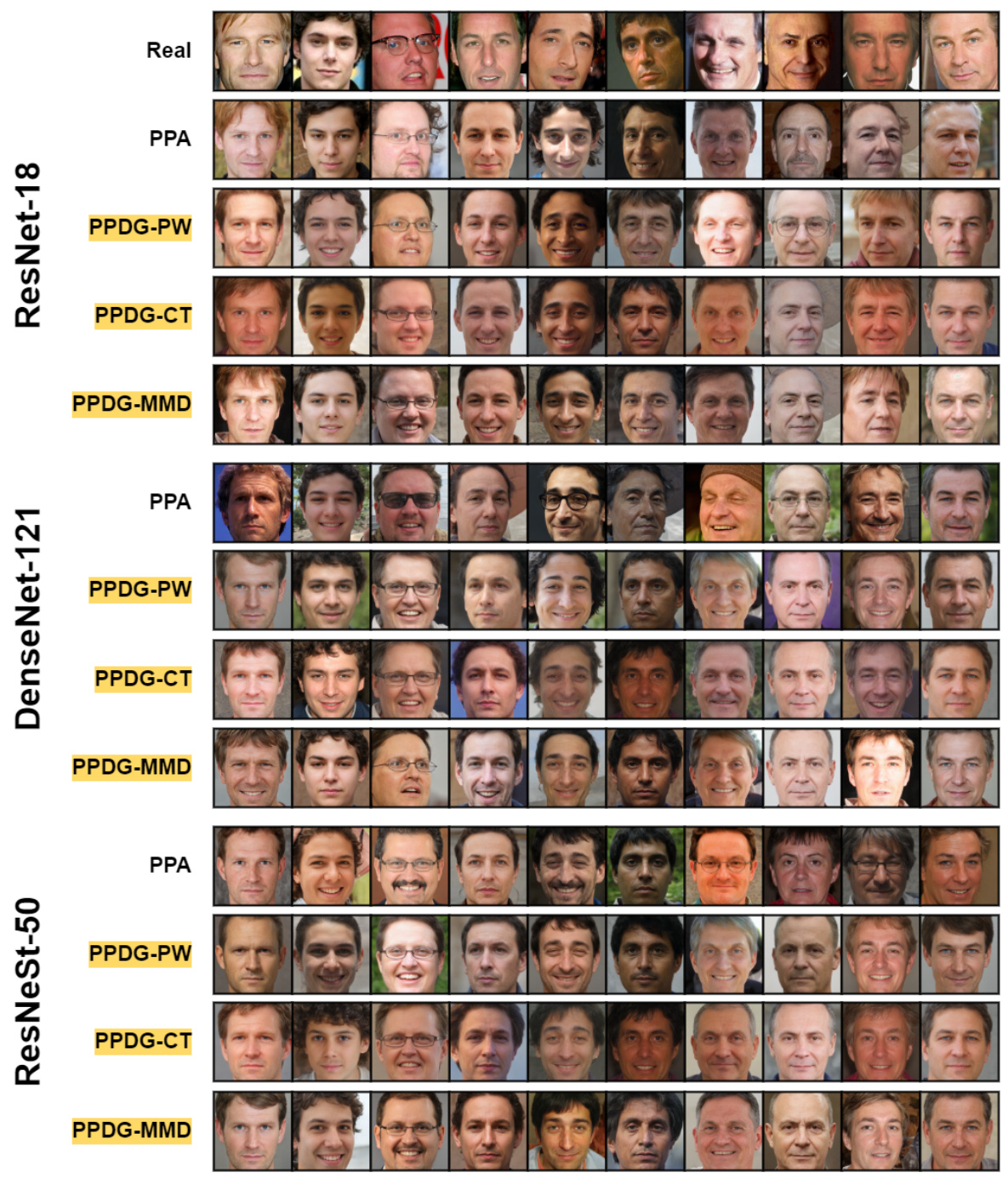

🔼 This figure compares the quality of reconstructed face images using different model inversion methods in a high-resolution setting. The ‘Real’ row shows the original images from the CelebA dataset (private training data). The ‘PPA’ row displays results from the state-of-the-art Plug-and-Play Attacks (PPA) method. Subsequent rows show the results obtained by augmenting the PPA method with three variants of the proposed Pseudo-Private Data Guided Model Inversion (PPDG-MI) approach: PPDG-PW (point-wise tuning), PPDG-CT (conditional transport), and PPDG-MMD (maximum mean discrepancy). The comparison aims to visually demonstrate the improved ability of the PPDG-MI method to reconstruct higher-fidelity images compared to the original PPA method. The different models used (ResNet-18, DenseNet-121, and ResNeSt-50) are also shown.

read the caption

Figure 9: Visual comparison in high-resolution settings. We illustrate reconstructed samples for the first ten identities in Dprivate = CelebA using GANs pre-trained on Dpublic = FFHQ.

🔼 This figure shows a visual comparison of reconstructed face images generated by different model inversion attack methods in high-resolution settings. The top row displays actual images from the CelebA dataset. Subsequent rows show the results obtained using the standard Plug & Play Attack (PPA) and three variations of the proposed Pseudo-Private Data Guided Model Inversion (PPDG-MI) approach: PPDG-PW, PPDG-CT, and PPDG-MMD. The goal is to compare the visual quality and similarity to the original images produced by each method.

read the caption

Figure 9: Visual comparison in high-resolution settings. We illustrate reconstructed samples for the first ten identities in Dprivate = CelebA using GANs pre-trained on Dpublic = FFHQ.

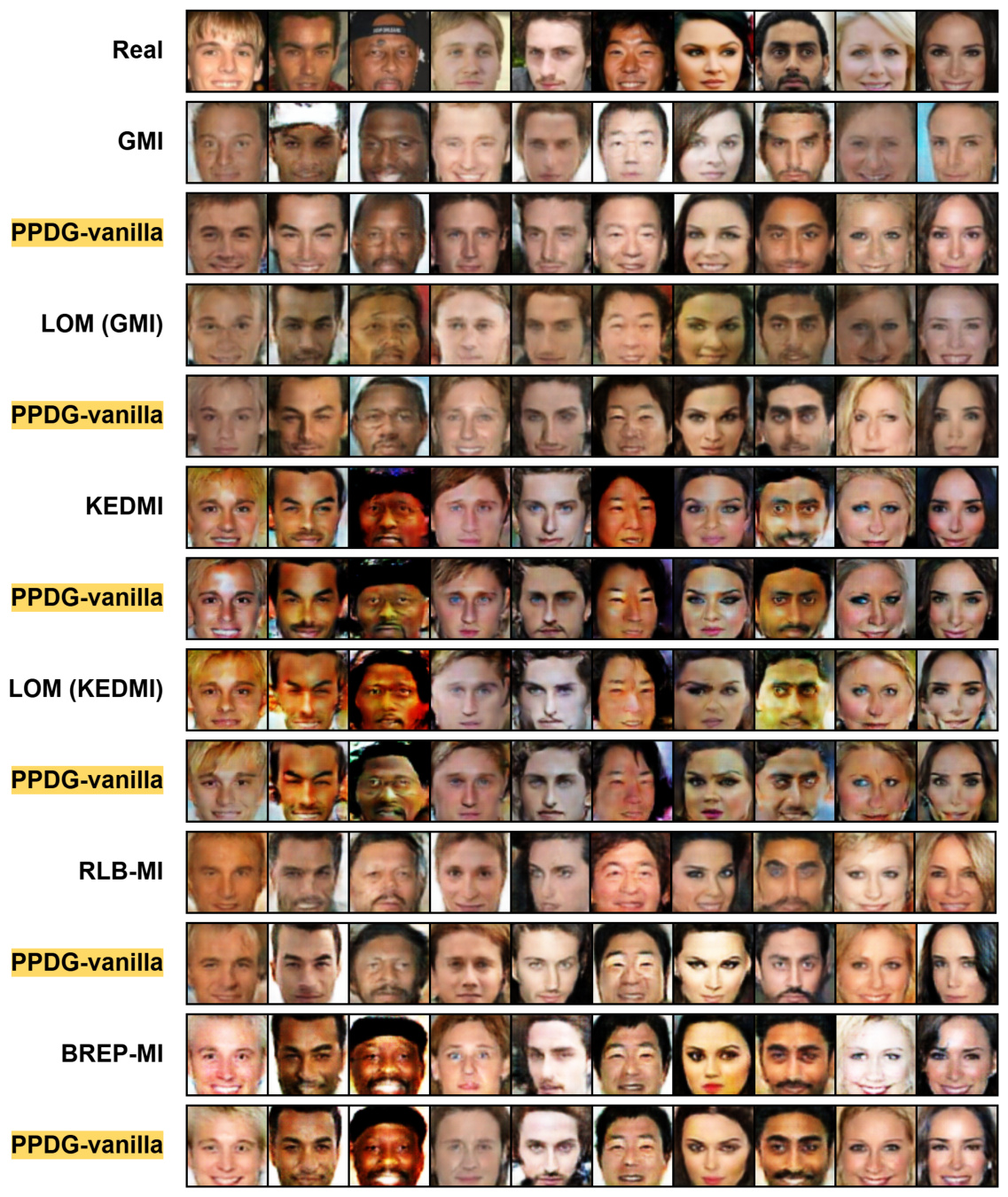

🔼 This figure visually compares the reconstructed images of ten identities from different model inversion attack methods with the actual images in the CelebA dataset. The top row shows the actual images, followed by results from GMI, PPDG-vanilla, LOM (GMI), PPDG-vanilla, KEDMI, PPDG-vanilla, LOM (KEDMI), PPDG-vanilla, RLB-MI, PPDG-vanilla, BREP-MI, and PPDG-vanilla. Each row shows the reconstructed images generated by a specific method. This visual comparison allows for a qualitative assessment of the different model inversion methods.

read the caption

Figure 11: Visual comparison in low-resolutions settings. We illustrate reconstructed samples for the first ten identities in Dprivate = CelebA using GANs trained from scratch on Dpublic = CelebA.

🔼 This figure compares the visual quality of reconstructed images generated by different model inversion attack methods (GMI, LOM(GMI), KEDMI, LOM(KEDMI), RLB-MI, BREP-MI) with and without the proposed PPDG-vanilla method. The top row shows the actual images from the CelebA dataset. Subsequent rows compare the outputs of each method, demonstrating the effectiveness of PPDG-vanilla in improving the visual fidelity of reconstructed images.

read the caption

Figure 11: Visual comparison in low-resolutions settings. We illustrate reconstructed samples for the first ten identities in Dprivate = CelebA using GANs trained from scratch on Dpublic = CelebA.

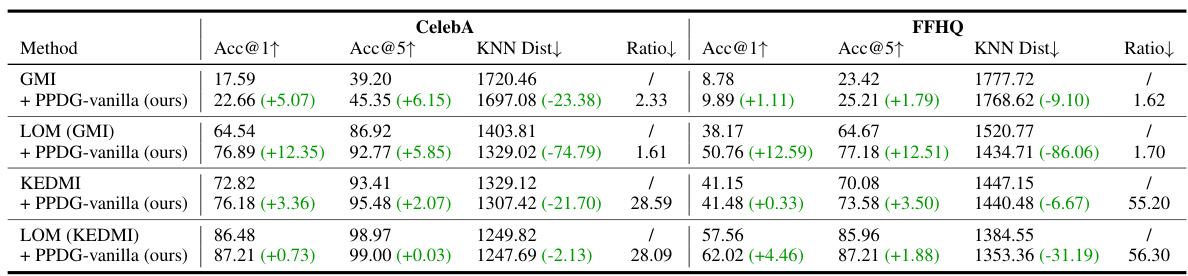

More on tables

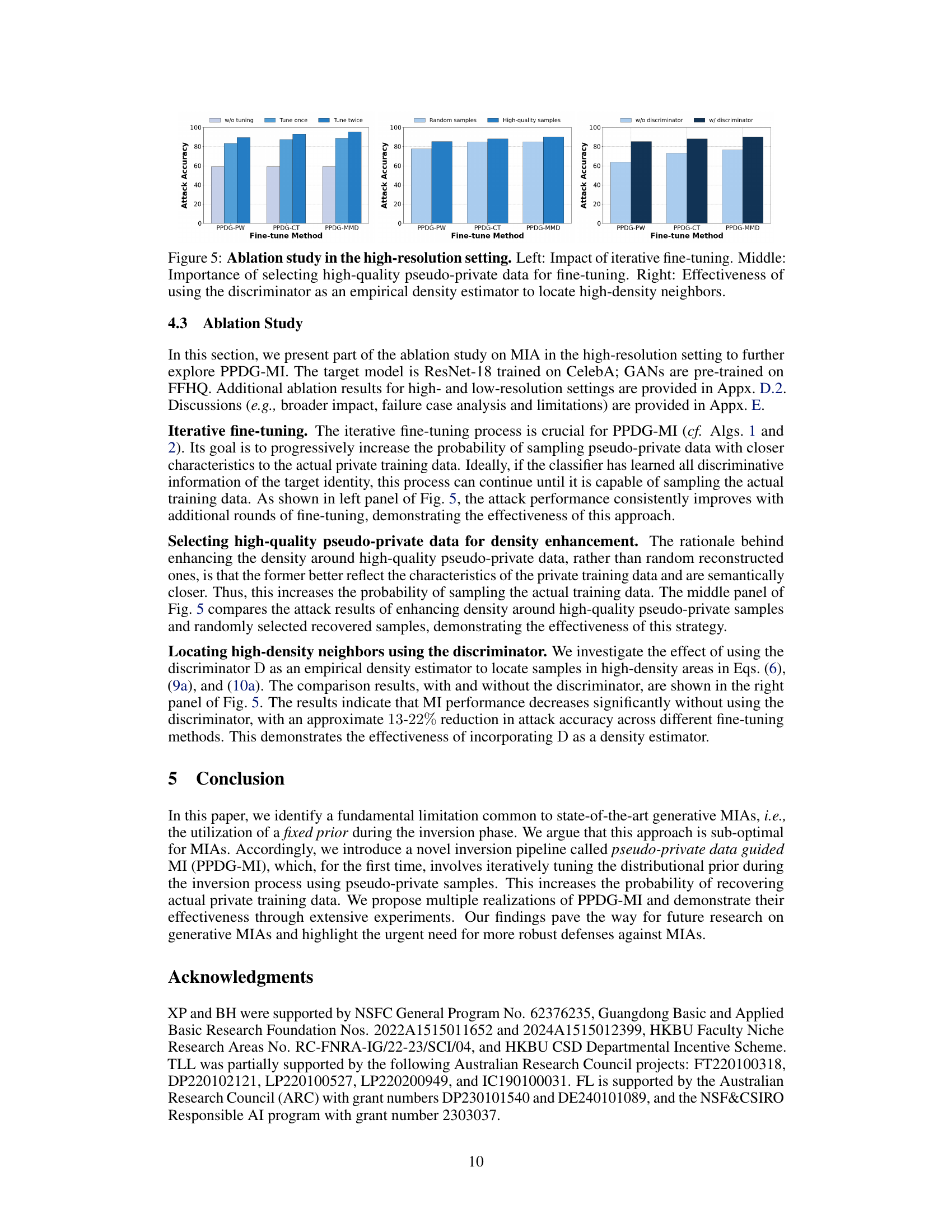

🔼 This table presents the results of comparing the performance of the proposed PPDG-vanilla method with several state-of-the-art (SOTA) white-box model inversion attack methods in low-resolution settings. The target model used is VGG16, trained on a private CelebA dataset. The GANs used in the attacks were trained on either a public CelebA dataset or a public FFHQ dataset. The table shows the accuracy (@1 and @5), KNN distance, and the ratio of the running time between fine-tuning and model inversion for each method.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of MI performance with white-box MIAs in low-resolution settings. Target model M = VGG16 trained on Dprivate = CelebA. GANs are trained on Dpublic = CelebA or FFHQ.

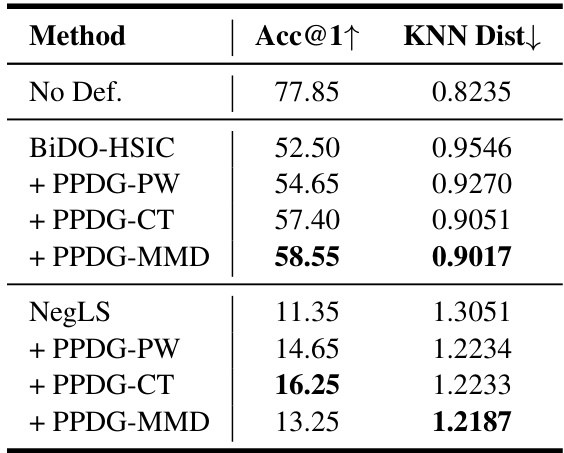

🔼 This table presents the results of model inversion attacks (MIAs) against state-of-the-art (SOTA) defense methods. The target model is ResNet-152, trained on a private FaceScrub dataset, with GANs pre-trained on a public FFHQ dataset. The table compares the performance of the baseline PPA method against three variants of PPDG-MI (PPDG-PW, PPDG-CT, and PPDG-MMD) when facing two defenses: BiDO-HSIC and NegLS. The results are presented in terms of Acc@1 (top-1 attack accuracy) and KNN Dist (K-Nearest Neighbors Distance), indicating the improvement achieved by integrating the PPDG-MI strategy.

read the caption

Table 3: MI performance against SOTA defense methods in high-resolution settings. The target model M = ResNet-152 is trained on Dprivate = FaceScrub, GANs are pre-trained on Dpublic = FFHQ. Bold numbers indicate superior results.

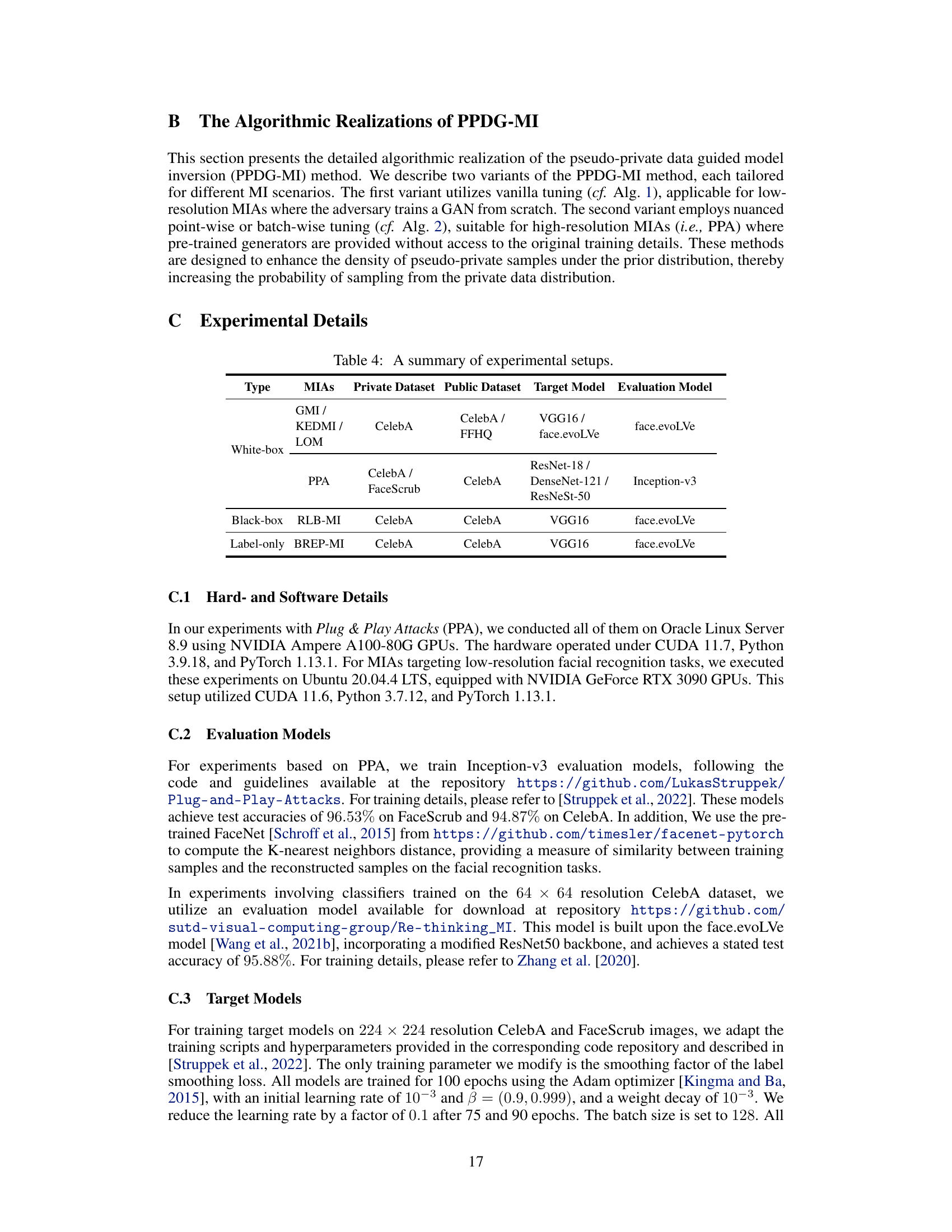

🔼 This table summarizes the experimental setups used in the paper. It specifies the type of model inversion attack (MIA) used, the private and public datasets used for training and evaluation, the target model used, and the evaluation model used to assess the performance of the attack. Different rows represent different experimental configurations, categorized by the type of MIA (white-box, black-box, and label-only).

read the caption

Table 4: A summary of experimental setups.

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment designed to evaluate the impact of distribution alignment on the performance of model inversion attacks. The experiment compares the performance of a baseline attack (PPA) with an attack that incorporates distribution alignment using PPDG-MI. The results are presented in terms of attack accuracy (Acc@1↑) and KNN distance (KNN Dist↓). The goal is to demonstrate that enhancing the density of pseudo-private data under the prior distribution improves the accuracy of model inversion attacks.

read the caption

Table 5: Enhance density of pseudo-private data under the prior distribution by distribution alignment.

🔼 This table compares the performance of several model inversion attack methods (GMI, LOM, KEDMI) with and without the proposed PPDG-vanilla method, on the face.evoLVe model trained with CelebA dataset. It shows the attack accuracy (Acc@1, Acc@5), KNN distance, and the relative running time for each method, using both CelebA and FFHQ as public datasets for GAN training. Green numbers highlight the performance improvements achieved by integrating PPDG-vanilla.

read the caption

Table 6: Comparison of MI performance with representative white-box MIAs in the low-resolution setting. The target model M is face.evoLVe trained on Dprivate = CelebA. GANs are trained on Dpublic = CelebA or FFHQ. The symbol ↓ (or ↑) indicates smaller (or larger) values are preferred, and the green numbers represent the attack performance improvement. The running time ratio (Ratio) between prior fine-tuning and MI reflects the relative overhead of fine-tuning.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed PPDG-vanilla method against the state-of-the-art PLG-MI method for model inversion attacks on low-resolution images. The results show the attack accuracy (Acc@1, Acc@5), the KNN distance, and the ratio of running time for fine-tuning versus model inversion for both VGG16 and face.evoLVe target models. It demonstrates improved MI performance with PPDG-vanilla.

read the caption

Table 7: Comparison of MI performance with PLG-MI in the low-resolution setting. Target model M = VGG16 or face.evoLVe trained on Dprivate = CelebA. GANs are trained on Dpublic = FaceScrub.

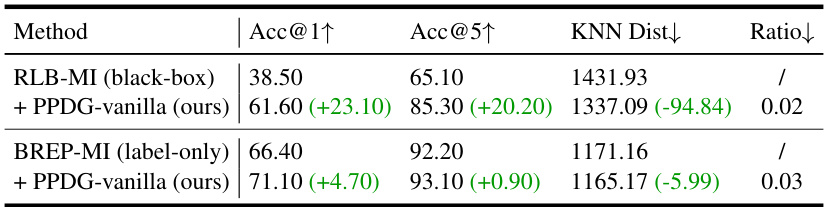

🔼 This table compares the performance of model inversion attacks (MIAs) using two different methods: RLB-MI (a black-box attack) and BREP-MI (a label-only attack). It shows the results with and without using the proposed PPDG-vanilla method. The metrics used are attack accuracy at top-1 and top-5 (Acc@1↑, Acc@5↑), KNN distance (KNN Dist↓), and the ratio of running time between fine-tuning and the main MI attack (Ratio↓). Lower values for KNN Dist are better, while higher values are better for Acc@1↑ and Acc@5↑. The green numbers indicate the improvements achieved by using PPDG-vanilla.

read the caption

Table 8: Comparison of MI performance with RLB-MI and BREP-MI in the low-resolution setting. The target model M is VGG-16 trained on Dprivate = CelebA, GANs are trained on Dpublic = CelebA. The symbol ↓ (or ↑) indicates smaller (or larger) values are preferred, and the green numbers represent the attack performance improvement. The running time ratio (Ratio) between prior fine-tuning and MI reflects the relative overhead of fine-tuning.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the performance of three model inversion attack methods (LOM (GMI), KEDMI, and LOM (KEDMI)) against two state-of-the-art defense mechanisms (BiDO-HSIC and NegLS) in a low-resolution setting. The results show that incorporating PPDG-vanilla consistently improves attack performance across all three attack methods and both defense mechanisms, highlighting its effectiveness in enhancing the robustness of MIAs against existing defenses.

read the caption

Table 9: Comparison of MI performance against state-of-the-art defense methods in the low-resolution setting. The target model M is VGG16 trained on Dprivate = CelebA, GANs are trained on Dpublic = CelebA. Bold numbers indicate superior results.

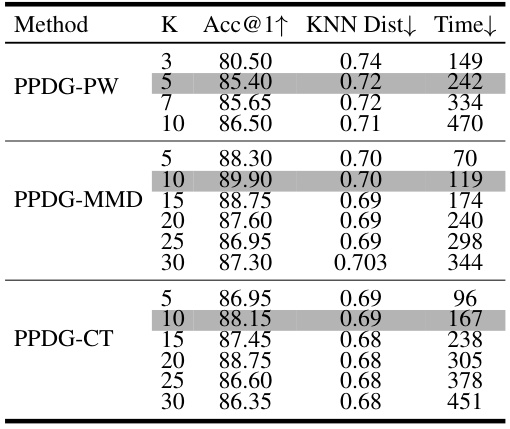

🔼 This table shows the ablation study on the impact of the number of high-quality pseudo-private samples selected for fine-tuning on the performance of PPDG-PW, PPDG-MMD, and PPDG-CT methods. The results indicate that increasing K initially improves performance but eventually leads to a decline due to overfitting and increased computational cost.

read the caption

Table 10: Ablation study on the number K of high-quality samples selected for fine-tuning. 'Time' (seconds per identity) denotes the time required for fine-tuning a single identity.

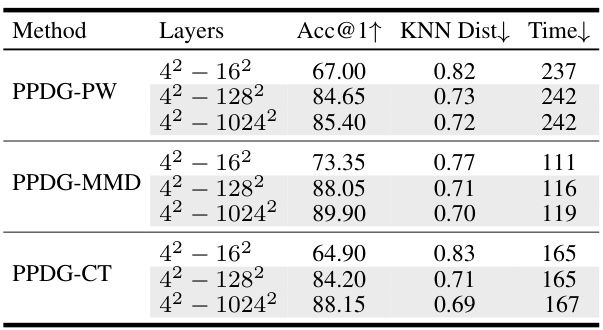

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of fine-tuning different layers of the StyleGAN generator on the performance of PPDG-MI. The results show that tuning layers with spatial resolutions from 4 2 −128 2 achieves comparable results to tuning all layers (4 2 −1024 2 ), suggesting that successful MIAs rely more on inferences about high-level features (e.g., face shape) rather than fine-grained details.

read the caption

Table 11: Ablation study on fine-tuning different layers of the StyleGAN synthesis network. 'Time' (seconds per identity) denotes the time required for fine-tuning a single identity.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the state-of-the-art model inversion attack (PPA) with three variants of the proposed PPDG-MI method (PPDG-PW, PPDG-CT, and PPDG-MMD) on two high-resolution face recognition datasets (CelebA and FaceScrub). The results show the improvement in attack accuracy (Acc@1 and Acc@5) and reduction in KNN distance, indicating better reconstruction of private data with the proposed methods. The running time ratio shows the computational overhead of adding the PPDG-MI improvements.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of MI performance with PPA in high-resolution settings. Dprivate = CelebA or FaceScrub, GANs are pre-trained on Dpublic = FFHQ. The symbol ↓ (or ↑) indicates smaller (or larger) values are preferred, and the green numbers represent the attack performance improvement. The running time ratio (Ratio) between prior fine-tuning and MI reflects the overhead of fine-tuning.

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results on the impact of the number of high-quality pseudo-private samples (K) used for fine-tuning the generator. It shows the attack accuracy (Acc@1↑), K-Nearest Neighbors Distance (KNN Dist↓), and the time required for fine-tuning a single identity for different values of K, using three different fine-tuning methods (PPDG-PW, PPDG-CT, and PPDG-MMD).

read the caption

Table 10: Ablation study on the number K of high-quality samples selected for fine-tuning. 'Time' (seconds per identity) denotes the time required for fine-tuning a single identity.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the state-of-the-art model inversion attack (PPA) with the proposed PPDG-MI method in high-resolution settings. It shows the improvement in attack accuracy (Acc@1 and Acc@5), reduction in KNN distance, and the running time ratio for three different target models (ResNet-18, DenseNet-121, and ResNeSt-50). The results are shown for two private datasets (CelebA and FaceScrub).

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of MI performance with PPA in high-resolution settings. Dprivate = CelebA or FaceScrub, GANs are pre-trained on Dpublic = FFHQ. The symbol ↓ (or ↑) indicates smaller (or larger) values are preferred, and the green numbers represent the attack performance improvement. The running time ratio (Ratio) between prior fine-tuning and MI reflects the overhead of fine-tuning.

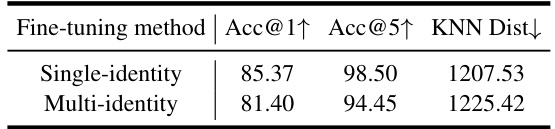

🔼 This table presents the ablation study comparing the performance of single-identity and multi-identity fine-tuning strategies. The results show that single-identity fine-tuning achieves better performance (higher attack accuracy and lower KNN distance), but multi-identity fine-tuning reduces computational costs. The trade-off between performance and efficiency is highlighted.

read the caption

Table 15: Ablation study on identity-wise fine-tuning vs. multi-identity fine-tuning.

Full paper#