↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current AI decision support systems often improve average prediction accuracy but can cause harm; sometimes, human experts would’ve made better decisions without the system. This is problematic in high-stakes settings (medicine, law) where “first, do no harm” is paramount. This necessitates a better understanding of this

counterfactual harm".

This paper proposes a solution using structural causal models to formally define and quantify counterfactual harm within decision support systems. It shows that under specific assumptions, this harm is measurable, even estimable, with only human-only predictions. Using this, the authors build a framework that designs systems with less harm than a user-defined threshold, validated on real human prediction data. This significantly advances the development of safer and more beneficial AI systems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in human-AI collaboration and decision support systems. It directly addresses the critical issue of counterfactual harm, a significant concern in deploying AI systems that assist human decision-making. By introducing a novel framework for designing harm-reducing systems, it opens up new avenues for research in responsible AI development, particularly in high-stakes domains where the impact of erroneous decisions can be severe. The work also highlights the trade-off between accuracy and harm, leading to future exploration of optimal system designs that balance both.

Visual Insights#

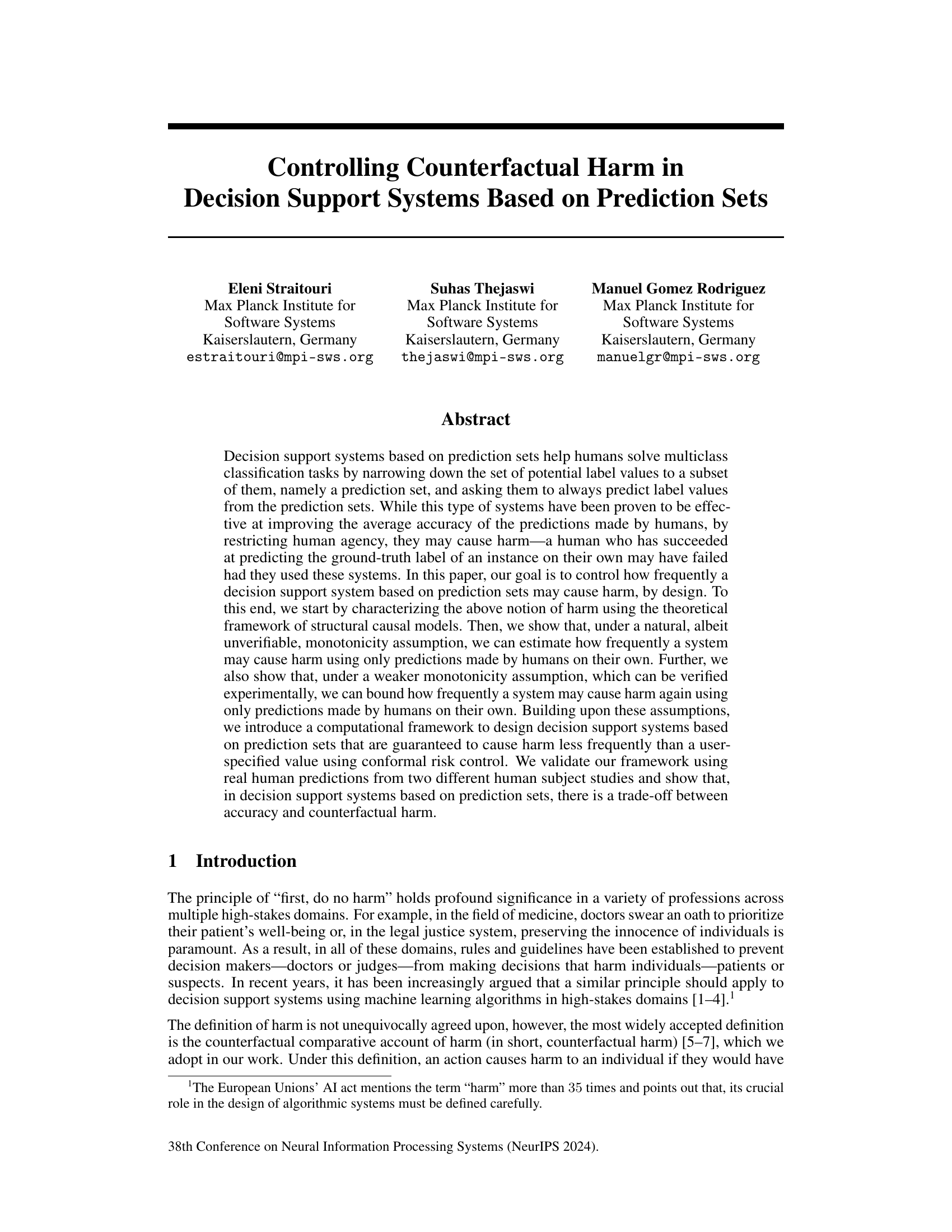

This figure presents a structural causal model (SCM) illustrating how a decision support system based on prediction sets affects human expert predictions. The model depicts the relationships between exogenous variables (V, U, Λ representing data generation, expert characteristics, and threshold), endogenous variables (X, Y, Cλ(X), Ŷ representing features, ground truth, prediction set, and expert prediction), and the causal flows between them. It serves as the foundation for the paper’s analysis of counterfactual harm.

In-depth insights#

Counterfactual Harm#

The concept of “Counterfactual Harm” explores the potential negative consequences of using a decision support system. It focuses on situations where a human, having successfully made a decision independently, would have performed worse using the system’s assistance. This highlights the crucial tension between improving accuracy and potentially hindering human judgment. The framework presented aims to mitigate this harm by design, incorporating a user-specified harm threshold. This is a significant step toward responsible AI development, emphasizing not only accuracy but also the ethical implications of AI-assisted decision-making. The use of structural causal models (SCMs) provides a robust theoretical foundation for analyzing counterfactual scenarios and making reliable estimations of potential harm. By leveraging this, the authors propose a computational framework, validated through human subject studies, to ensure that the decision support system causes less harm than a predetermined threshold. This approach emphasizes the trade-off between accuracy and harm, offering a more nuanced perspective on AI deployment in high-stakes decision settings.

Prediction Set Design#

Designing effective prediction sets is crucial for successful human-AI collaboration. A well-designed prediction set should minimize counterfactual harm, while maximizing human accuracy. This involves a trade-off: overly restrictive sets might hinder human performance, while overly permissive sets negate the AI’s assistance. Therefore, the design needs to carefully consider the characteristics of both the AI’s predictions and the human’s decision-making capabilities. Conformal prediction methods offer a principled approach, controlling the risk of including incorrect labels, but further refinements are needed to directly optimize for human performance. Future research should explore adapting set sizes based on individual human expertise and the specific task context, for instance, by dynamically adjusting the prediction set’s size based on the perceived difficulty of the task and the human’s confidence. Ultimately, the design of prediction sets needs to be guided by empirical evidence regarding human behavior and decision-making processes, moving beyond simple accuracy metrics to consider the broader impact on human decision making.

Conformal Risk Control#

Conformal risk control, as discussed in the context of decision support systems, presents a valuable framework for mitigating counterfactual harm. It elegantly addresses the challenge of balancing improved human accuracy with the potential for unintended negative consequences by design. The core idea is to constrain the risk of harm to a user-specified level by carefully choosing the prediction sets used in the system. This is achieved using conformal prediction, offering a distribution-free approach that doesn’t rely on specific model assumptions. The key is to find a set of parameters (e.g., threshold values) for the conformal predictor that guarantees the average counterfactual harm remains below a predefined threshold . By incorporating real-world human prediction data in the evaluation, the proposed framework offers a practical approach for designing responsible AI systems that prioritize both accuracy and ethical considerations.

Monotonicity Assumptions#

The concept of monotonicity, in the context of decision support systems and prediction sets, is crucial for understanding and controlling counterfactual harm. Counterfactual monotonicity posits that if a human expert successfully predicts a label using a less restrictive prediction set (more options), they would also succeed with a more restrictive set. This assumption, while intuitive, is difficult to empirically verify. Interventional monotonicity, a more experimentally tractable assumption, focuses on the probability of success given different prediction set sizes. It implies that restricting options, while potentially improving average accuracy, might increase the chance of harm by preventing an expert from reaching a correct prediction they could have made independently. The authors leverage these monotonicity assumptions to establish identifiability results for counterfactual harm, crucial for designing decision support systems that balance accuracy and harm reduction. The choice between these assumptions reflects a trade-off between theoretical elegance and practical verifiability, highlighting a key challenge in this area of research.

Human-AI Tradeoffs#

The concept of “Human-AI Tradeoffs” in decision support systems highlights the inherent tension between leveraging AI’s capabilities and preserving human agency. Improved accuracy often comes at the cost of reduced human control and potential for counterfactual harm. A system that restricts human decision-making to a subset of options (e.g., prediction sets) might boost average performance but also prevents humans from utilizing their full expertise when it would lead to superior outcomes. This trade-off necessitates careful system design, balancing accuracy gains against the risks of diminished human autonomy and the possibility of detrimental consequences resulting from restricted options. Effective decision support should empower, not replace, human judgment by providing assistance within a framework that respects the limitations of AI and the unique capabilities of human intelligence.

More visual insights#

More on figures

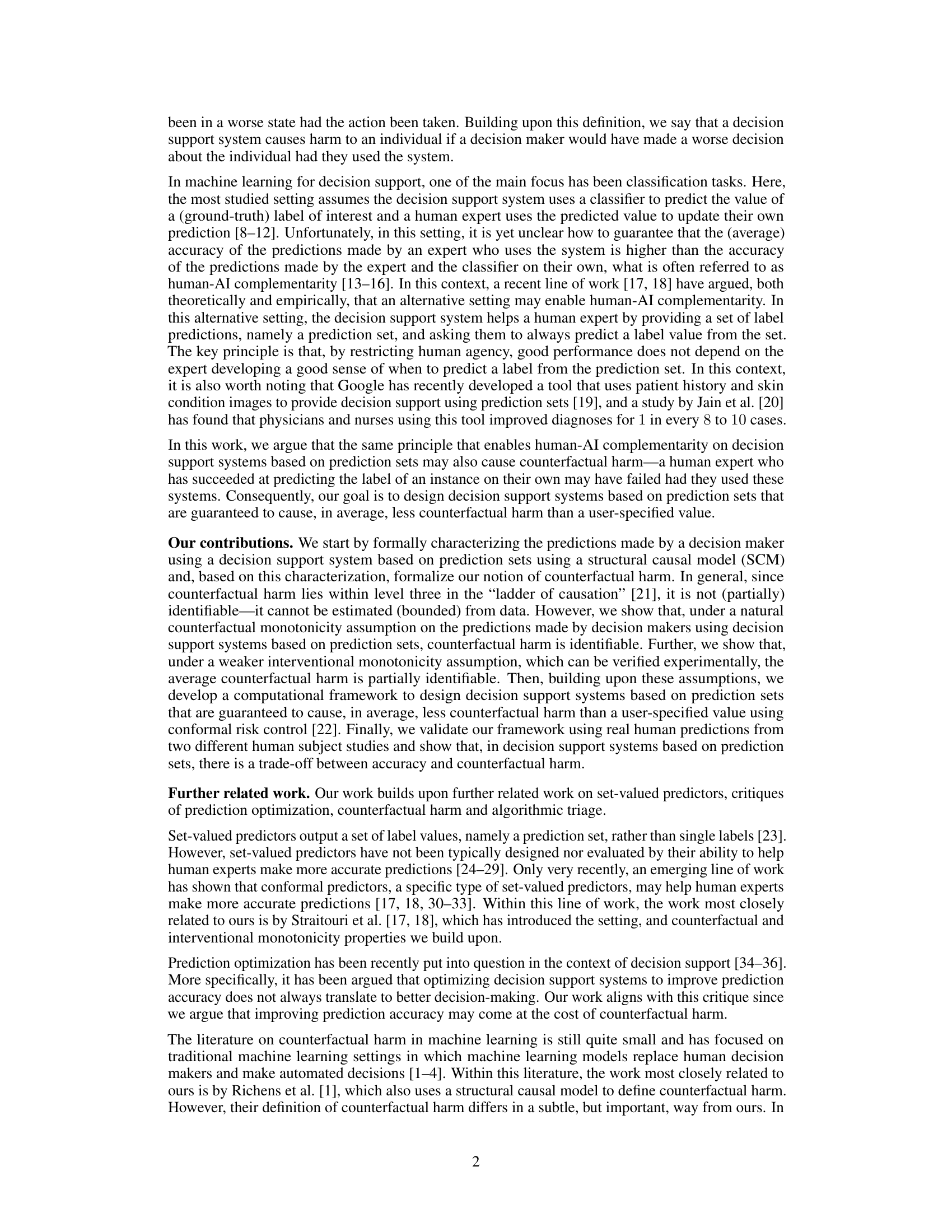

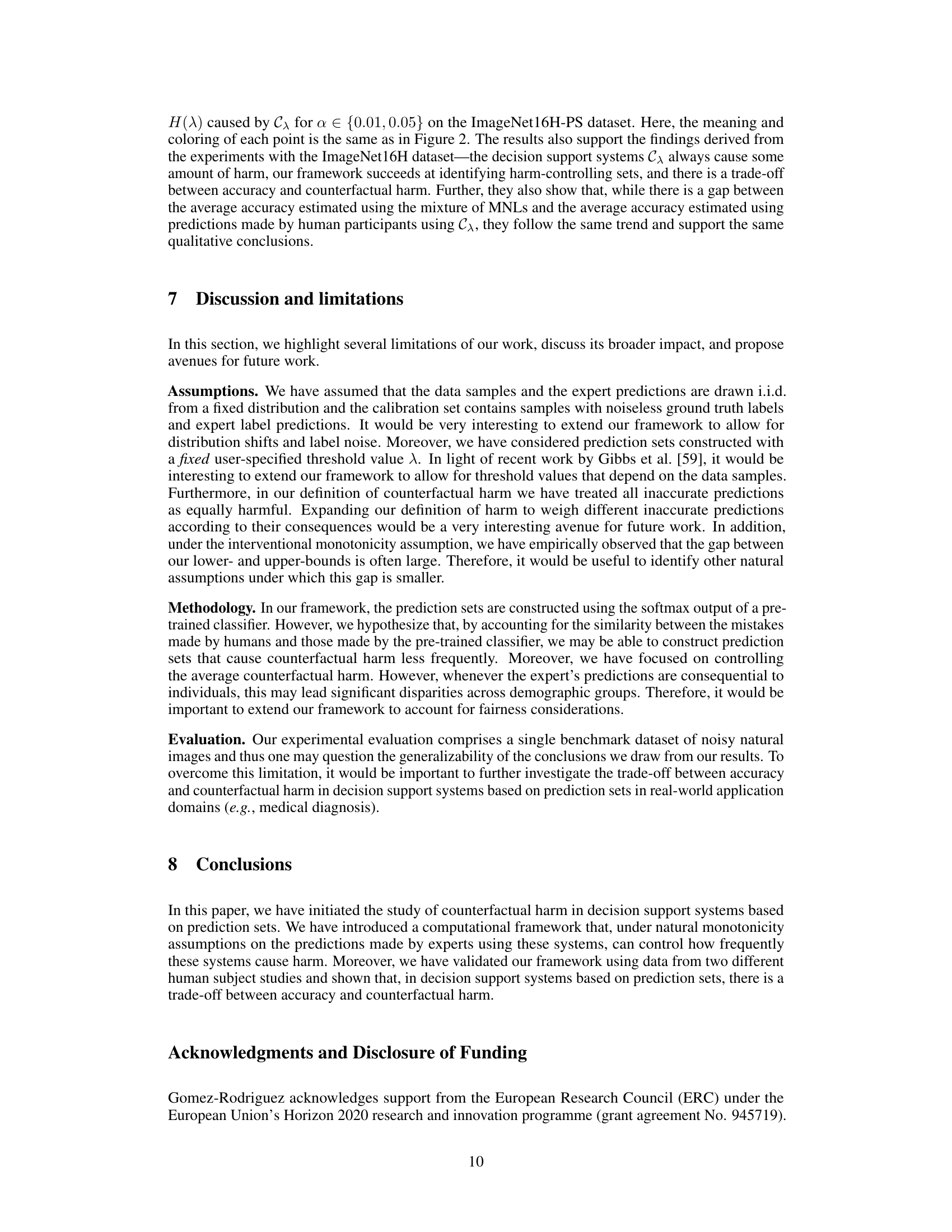

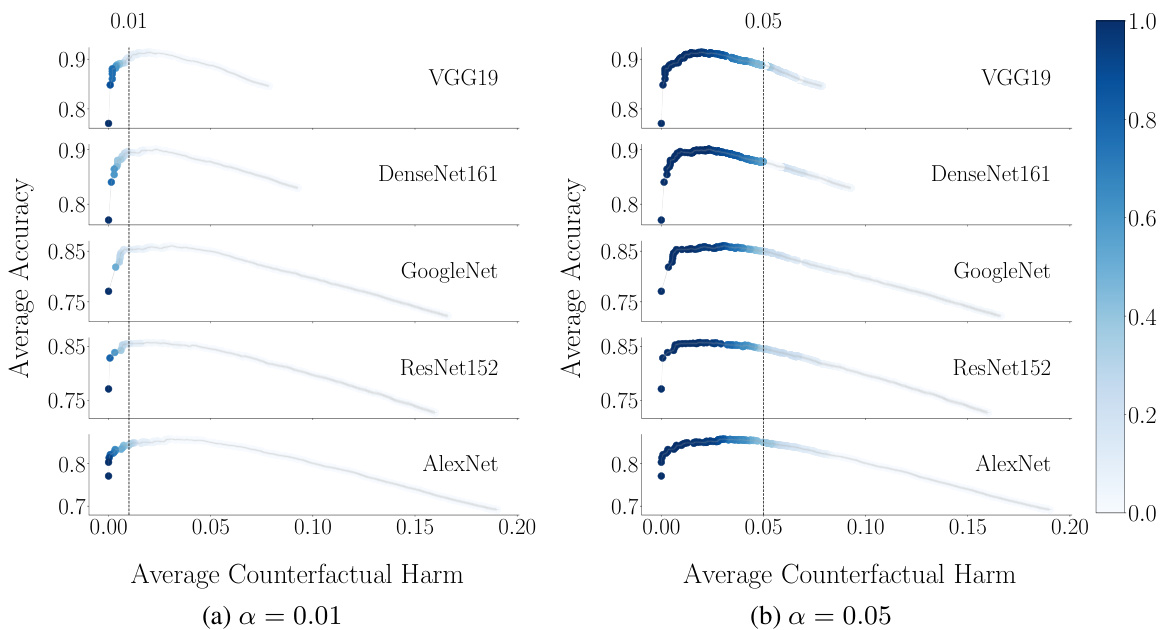

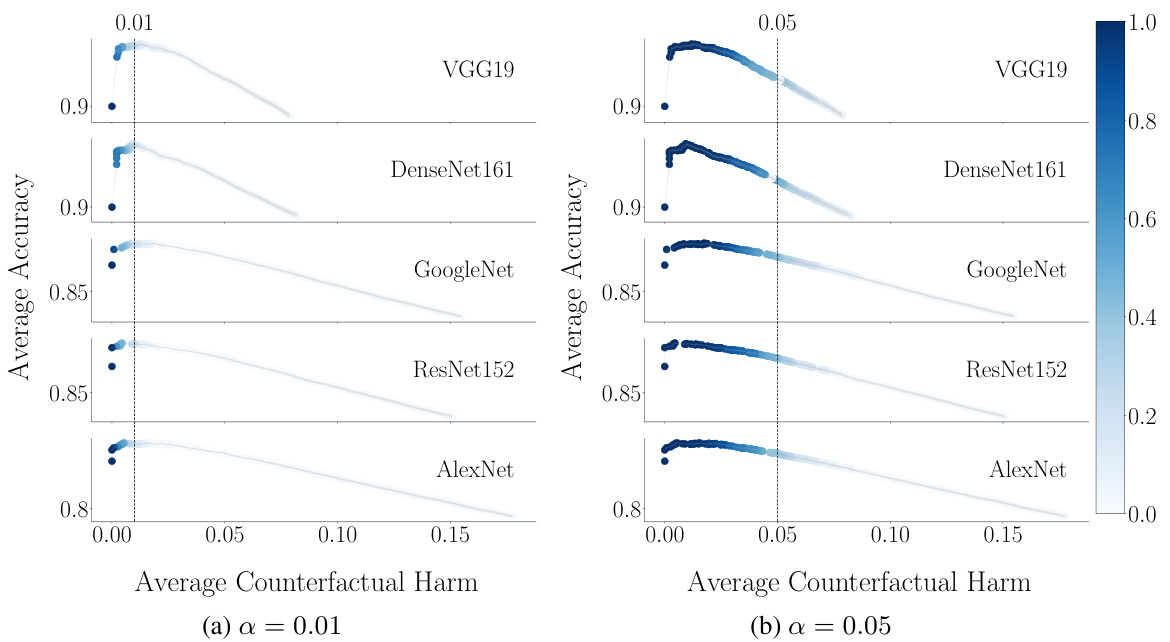

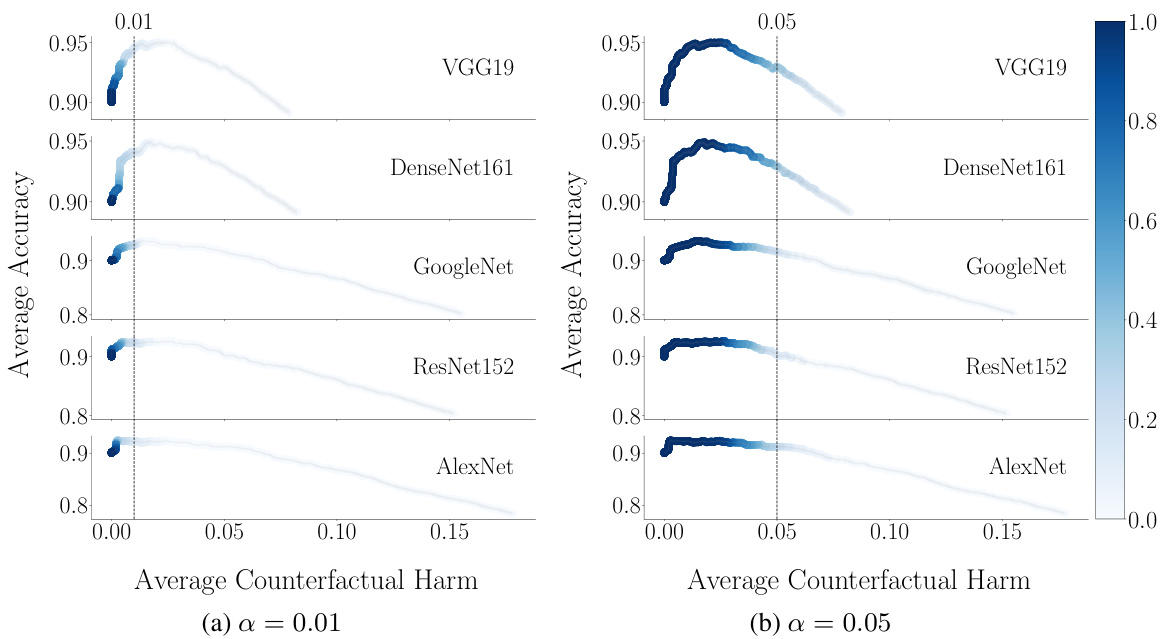

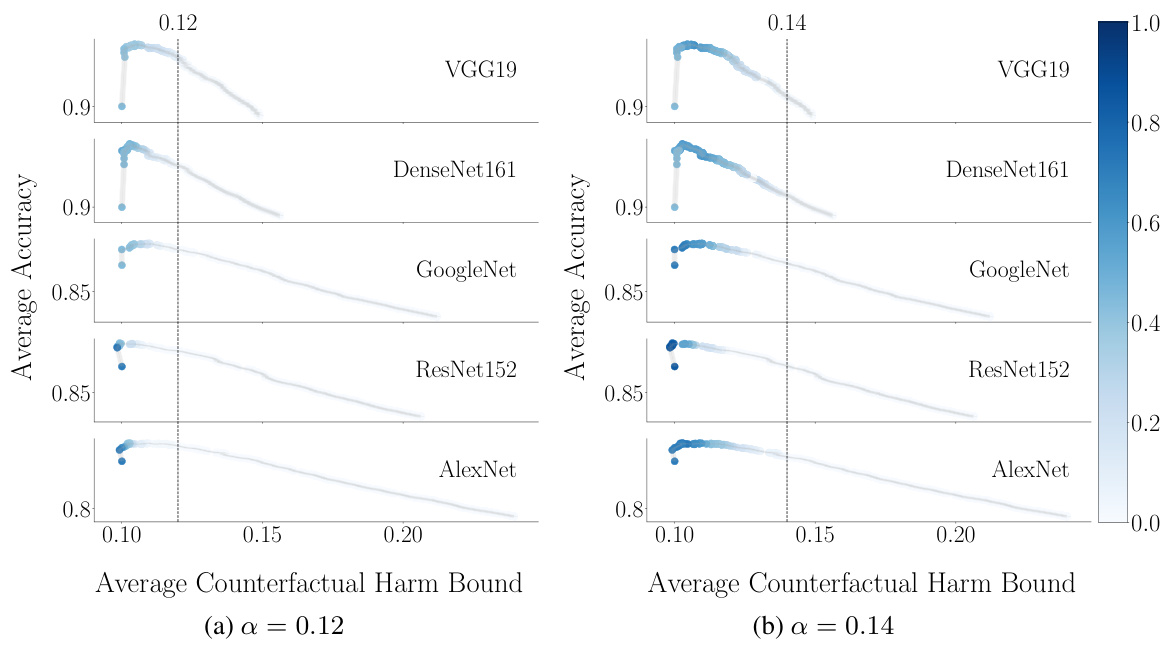

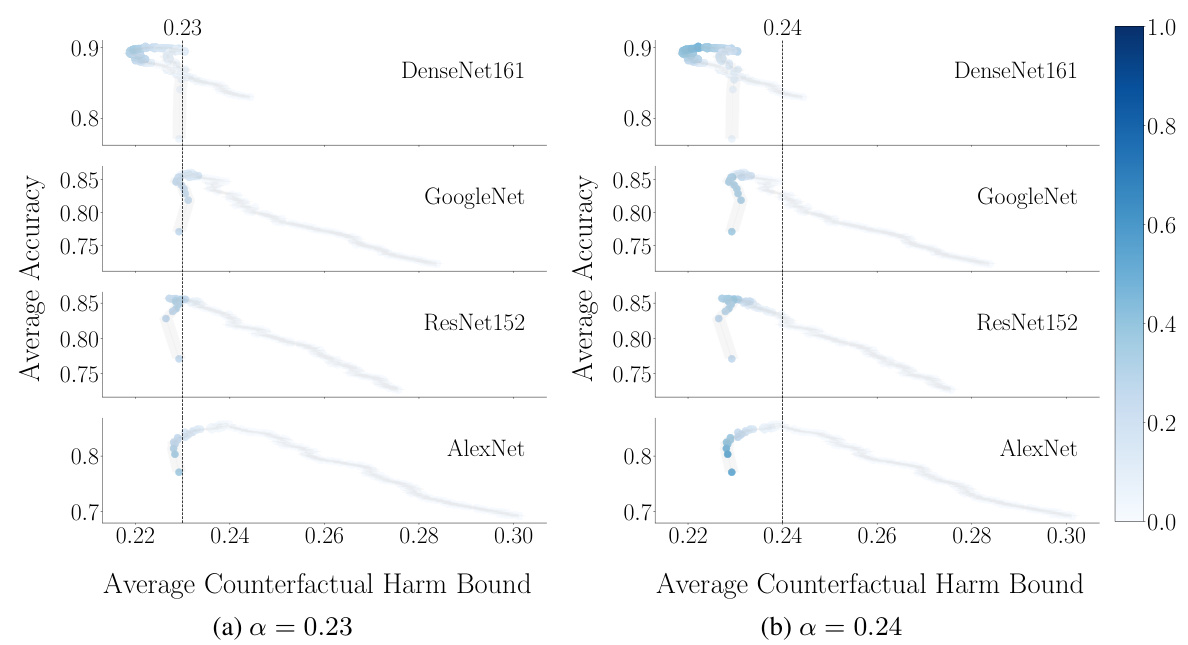

This figure shows the trade-off between accuracy and counterfactual harm in decision support systems based on prediction sets. The x-axis represents the average counterfactual harm, and the y-axis represents the average accuracy. Each point represents a different threshold (λ) used to generate prediction sets. The color intensity indicates how often that threshold resulted in a harm value below the specified α (0.01 in (a) and 0.05 in (b)). Different rows represent different pre-trained classifiers. The results suggest that improved accuracy often comes at the cost of increased counterfactual harm.

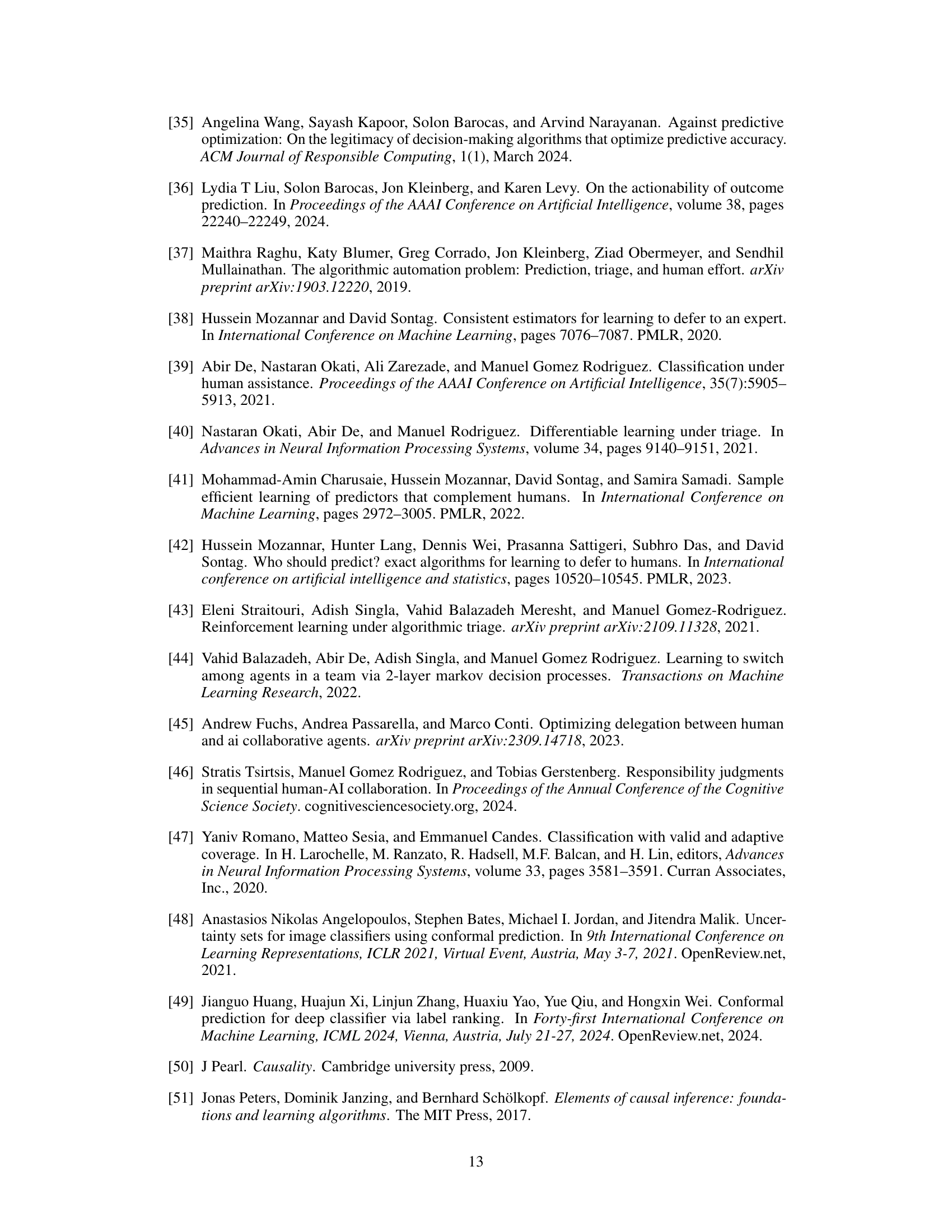

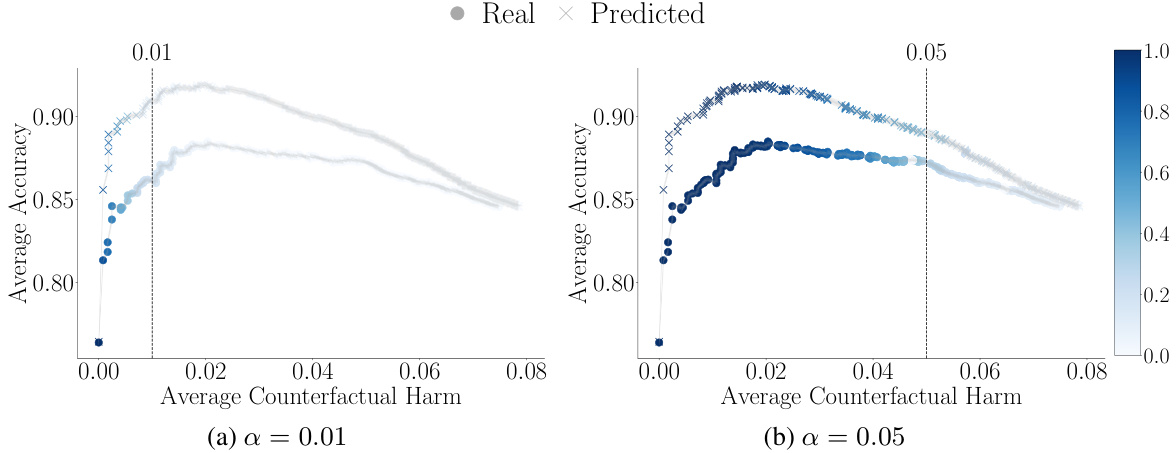

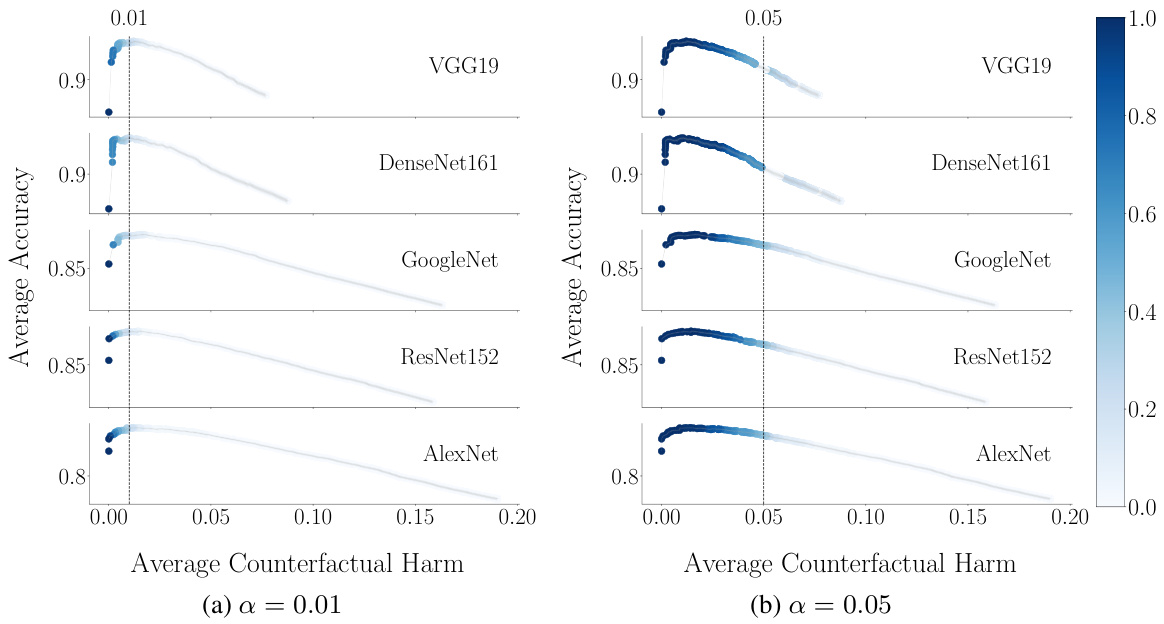

This figure compares the average accuracy of human participants’ predictions (Real) and predictions made by the mixture of multinomial logit models (MNLs, Predicted) against the average counterfactual harm caused by the decision support system Cλ using the pre-trained classifier VGG19 for α = 0.01 and α = 0.05. The figure shows the trade-off between accuracy and counterfactual harm, illustrating that higher accuracy may come at the cost of increased harm. The coloring of the points reflects the frequency with which each λ value is within the harm-controlling set Λ(α) for each α, indicating which λ values are suitable for controlling harm.

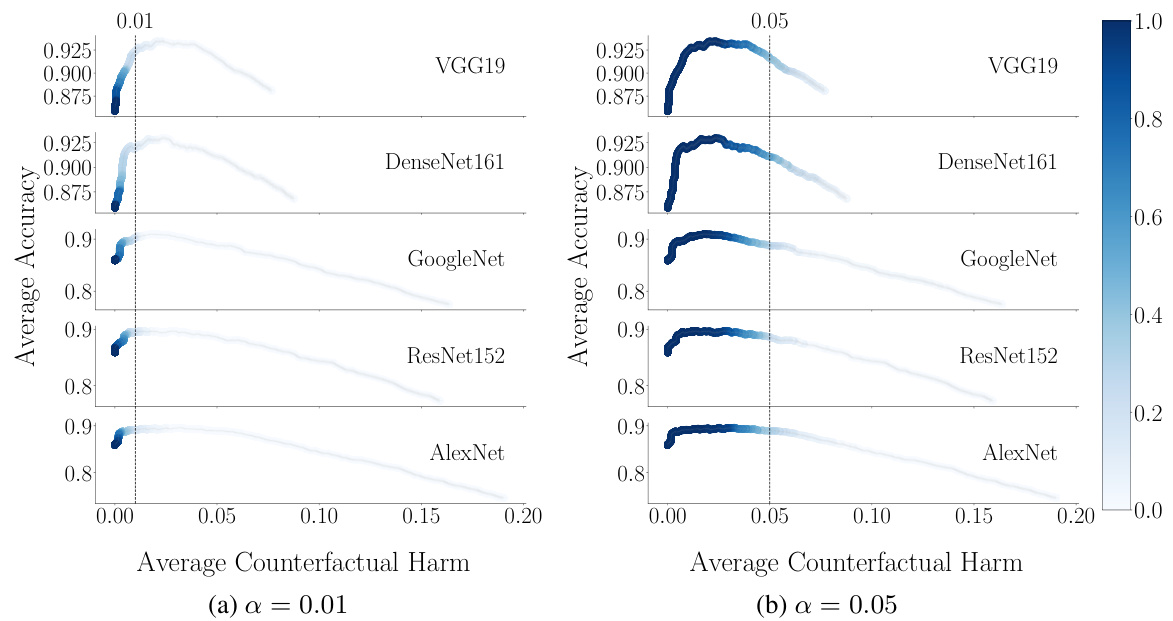

This figure shows the trade-off between accuracy and counterfactual harm in decision support systems based on prediction sets. The x-axis represents the average counterfactual harm, and the y-axis represents the average accuracy. Each point represents a different threshold value (λ) used to generate prediction sets. The color intensity indicates the frequency with which a given λ value was identified as harm-controlling (i.e., part of the set Λ(α)). Different rows represent results for systems using different pre-trained classifiers (VGG19, DenseNet161, GoogleNet, ResNet152, AlexNet).

This figure shows the trade-off between accuracy and counterfactual harm in decision support systems based on prediction sets. The x-axis represents the average counterfactual harm, and the y-axis represents the average accuracy achieved by human experts using the system. Each point represents a different threshold (λ) value used to create the prediction sets. The color intensity indicates how often that threshold value resulted in a harm level below the specified bound (α) across multiple random samplings. Different rows represent different pre-trained classifiers used, showcasing consistent trends across different models. The results demonstrate that higher accuracy can come at the cost of increased counterfactual harm.

This figure shows the trade-off between accuracy and counterfactual harm in decision support systems based on prediction sets. The x-axis represents the average counterfactual harm, and the y-axis represents the average accuracy. Each point represents a different threshold (λ) used to create the prediction sets. The color intensity indicates how often that threshold was selected as harm-controlling across multiple random samplings of the data. Different rows correspond to different pre-trained classifiers used to generate the prediction sets.

This figure shows the trade-off between accuracy and counterfactual harm in decision support systems based on prediction sets. It displays the average accuracy (estimated using a mixture of multinomial logit models) plotted against the average counterfactual harm for different threshold values (λ) in a system using prediction sets. Each line represents a different pre-trained classifier, and the color intensity represents the frequency with which a given threshold is considered harm-controlling. The results highlight that higher accuracy often comes at the cost of increased harm.

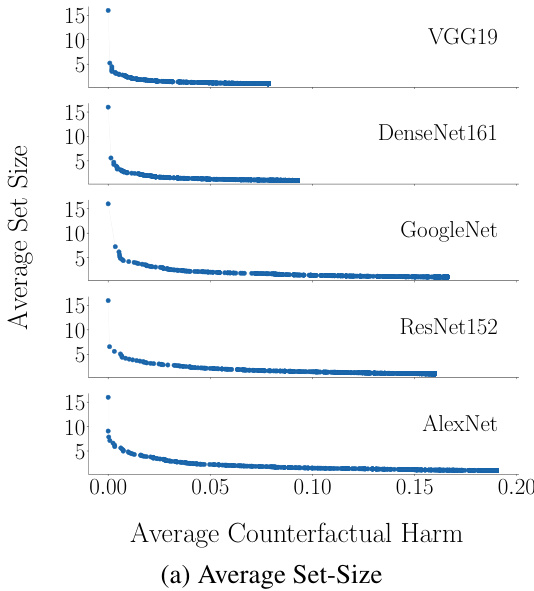

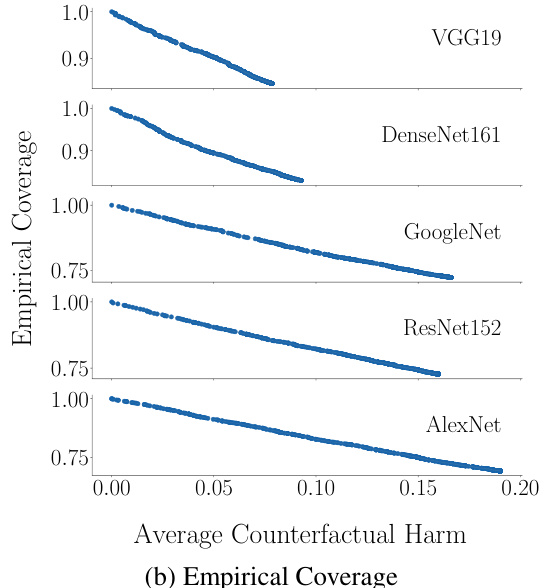

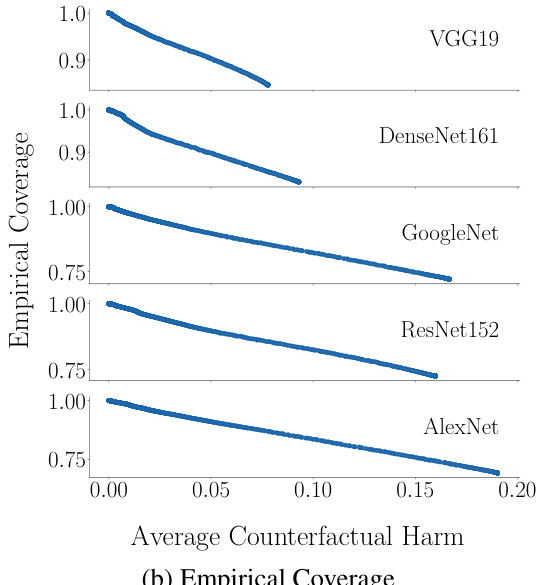

This figure shows the relationship between the average prediction set size and empirical coverage with the average counterfactual harm for different decision support systems using various pre-trained classifiers. It demonstrates that systems with higher coverage tend to generate larger prediction sets, and they also tend to cause less counterfactual harm.

This figure shows the trade-off between accuracy and counterfactual harm in decision support systems based on prediction sets. Each point represents a different threshold (λ) used to create prediction sets. The color intensity indicates how often that threshold resulted in harm below the user-specified threshold (α), averaged over multiple random samplings of the data. Different rows correspond to different pre-trained classifiers. The overall trend demonstrates that higher accuracy often comes at the cost of increased counterfactual harm.

This figure displays the trade-off between accuracy and counterfactual harm in decision support systems based on prediction sets. The x-axis represents average counterfactual harm, and the y-axis represents average accuracy. Each point shows a different threshold (λ) used to create prediction sets, with the color indicating how frequently that λ resulted in harm below the specified threshold (α) across different random samples. Different rows represent results obtained with different pre-trained classifiers (VGG19, DenseNet161, GoogleNet, ResNet152, AlexNet). The study demonstrates that higher accuracy often correlates with greater counterfactual harm.

This figure shows the trade-off between accuracy and counterfactual harm in decision support systems based on prediction sets. The x-axis represents the average counterfactual harm, and the y-axis represents the average accuracy. Each point represents a different threshold (λ) used to generate prediction sets. The color intensity indicates how often a given threshold results in an average counterfactual harm below the specified bound (α). Different rows represent different pre-trained classifiers. The study demonstrates that higher accuracy often comes at the cost of increased counterfactual harm.

This figure shows the trade-off between accuracy and counterfactual harm in decision support systems based on prediction sets. It plots the average accuracy (estimated using a mixture of multinomial logit models) against the average counterfactual harm for different threshold values (λ). Each line represents a different pre-trained classifier, demonstrating how the relationship between accuracy and harm varies depending on the model used. The color intensity indicates the frequency with which a given threshold value is part of the harm-controlling set (Λ(α)).

This figure shows the trade-off between accuracy and counterfactual harm in decision support systems based on prediction sets. Each point represents a different threshold (λ) used to create prediction sets. The color intensity shows how often that threshold resulted in harm below the specified level (α) across different random samplings of the data. Each row uses a different pre-trained classifier, demonstrating the impact of classifier choice on this trade-off. The results show that higher accuracy often comes at the cost of increased harm, highlighting a key challenge in designing these systems.

This figure shows the trade-off between accuracy and counterfactual harm in decision support systems based on prediction sets. It displays two subfigures: one showing the average prediction set size versus average counterfactual harm, and another showing the empirical coverage (the fraction of test samples where the prediction set contains the ground truth label) versus average counterfactual harm. The results are based on experiments using different pre-trained classifiers and averaged across multiple random samplings of the data.

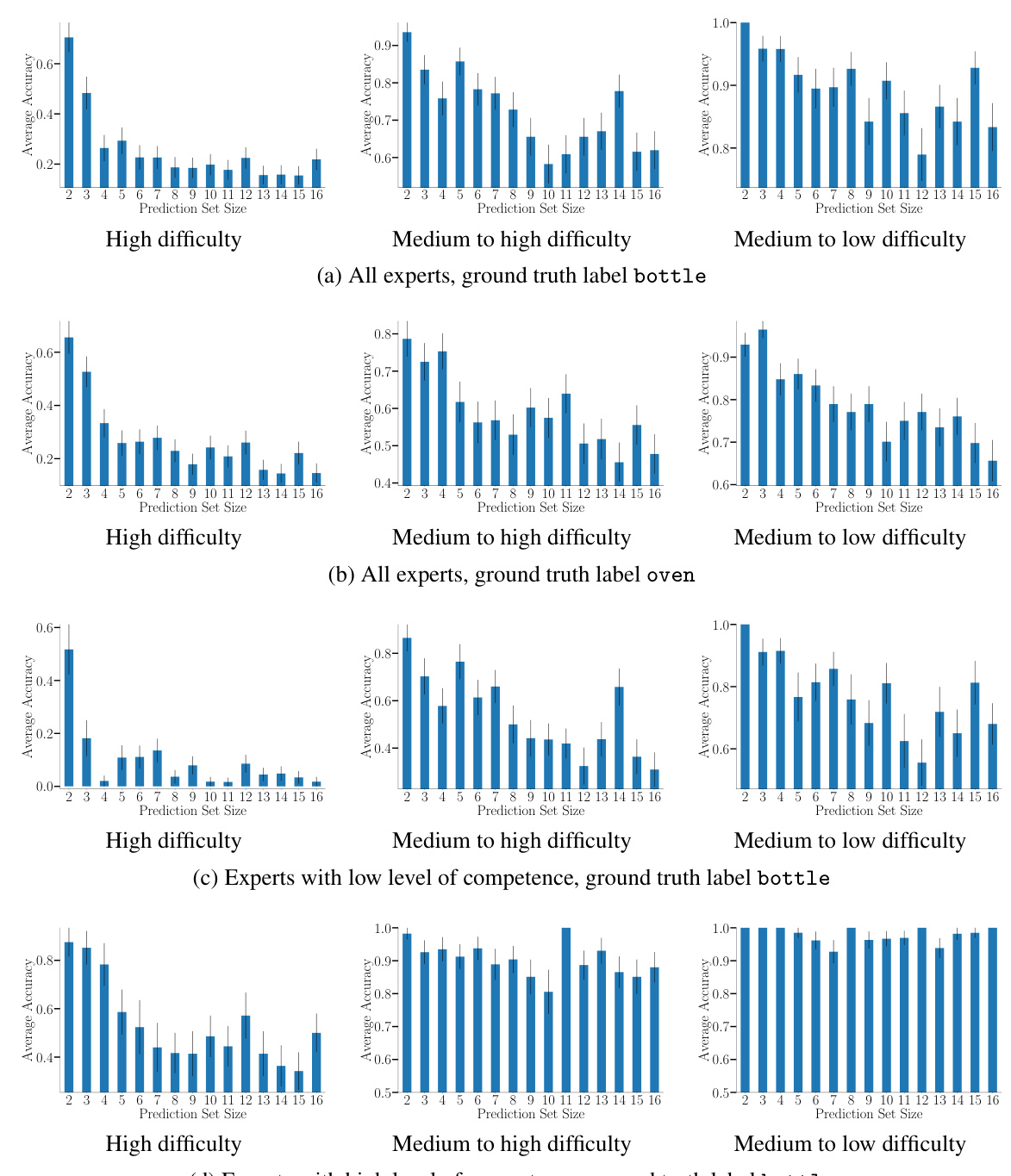

This figure shows the average accuracy achieved by human experts when predicting labels from prediction sets of different sizes. The data is stratified by image difficulty (high, medium-high, medium-low, low) and expert competence (high, low). Each panel shows results for a specific combination of label (bottle or oven) and expert competence level. The results visually demonstrate the relationship between prediction set size and prediction accuracy.

This figure displays the trade-off between accuracy and counterfactual harm for different decision support systems (different pre-trained classifiers) on images with a specific noise level (w=80). The x-axis represents the average counterfactual harm bound, while the y-axis shows the average accuracy. Each point represents a threshold (λ) value, and the color intensity indicates how frequently that threshold was found to be harm-controlling across multiple random samplings. The shaded areas show the 95% confidence intervals for the average accuracy.

This figure shows the trade-off between accuracy and counterfactual harm in decision support systems based on prediction sets. It compares the accuracy of human predictions (real) versus model-predicted accuracy (using a Mixture of Multinomial Logits, MNL) against the average counterfactual harm. The color intensity shows the frequency with which a specific threshold (λ) results in harm less than a user-specified value (α). The results show that even with the best threshold, some counterfactual harm is present, and that there is a trade-off between achieving high accuracy and minimizing harm.

This figure displays the trade-off between accuracy and counterfactual harm in decision support systems using prediction sets. Different pre-trained classifiers are used, and the effect of varying the threshold (λ) on accuracy and the upper bound of counterfactual harm is shown. The color intensity shows the frequency at which each threshold is within a harm-controlling set. The results are averaged across multiple random samplings to account for variability.

Full paper#