TL;DR#

Traditional 3D cloth simulators rely on discrete surface representations (meshes, points), leading to high memory consumption, resolution-dependent simulations, and difficulty integrating with neural networks. These limitations hinder the creation of realistic and highly interactive simulations needed for applications like computer animation and virtual fashion design. Back-propagating gradients through existing solvers is also challenging.

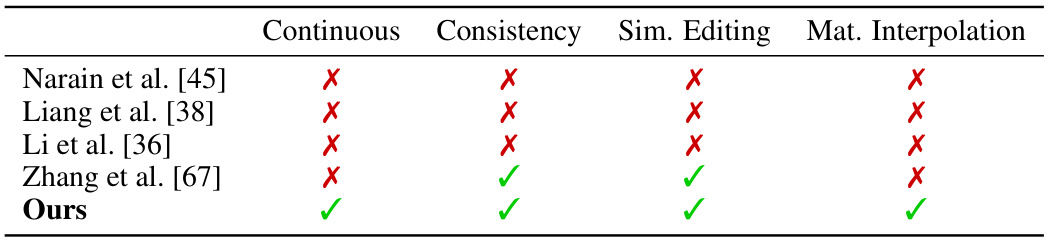

NeuralClothSim introduces a novel approach using a continuous coordinate-based neural representation called neural deformation fields (NDFs). These NDFs are supervised by the laws of non-linear Kirchhoff-Love shell theory, achieving memory efficiency and adaptive resolution. The results demonstrate effective material interpolation and simulation editing, highlighting the advantages of the continuous neural formulation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to cloth simulation that addresses limitations of existing methods. Its memory-efficient continuous neural representation and ability to handle arbitrary spatial resolutions have significant implications for various applications, including game engines, computer animation, and virtual fashion design. The use of thin shell theory within a neural network framework also opens new avenues for research in physically-based simulation and physics-informed neural networks. This paves the way for more realistic and interactive cloth simulation across various applications.

Visual Insights#

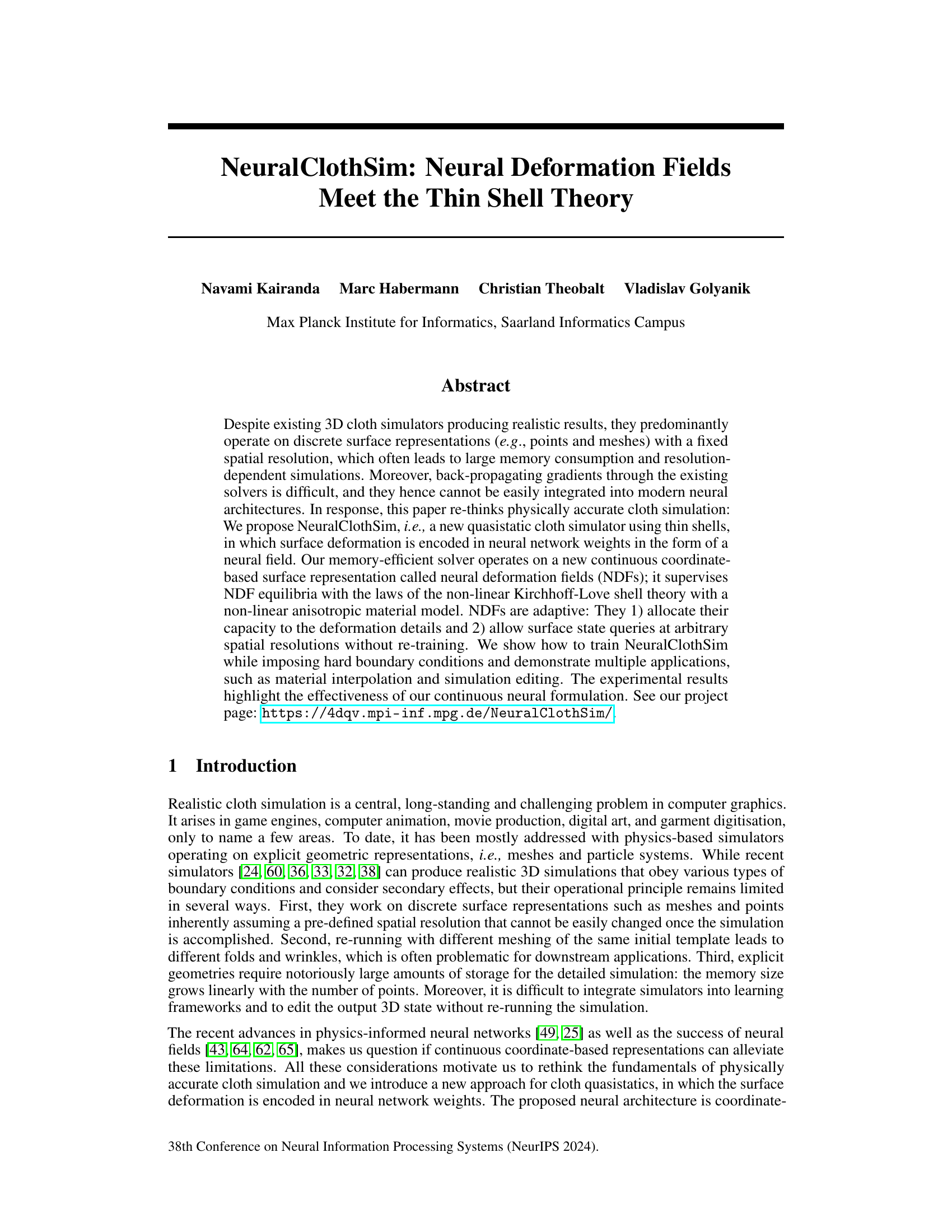

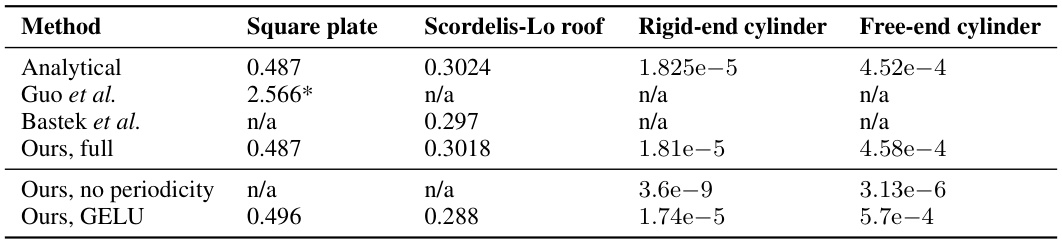

🔼 This figure shows the architecture of NeuralClothSim. The left panel illustrates the training process, where a neural deformation field learns to represent surface deformation under the supervision of the Kirchhoff-Love thin shell theory. The middle panel demonstrates the inference process at different resolutions, showcasing the ability of the model to produce consistent simulations at various levels of detail. Finally, the right panel exhibits the ability of NeuralClothSim to handle multiple materials and allows for test-time editing of material properties.

read the caption

Figure 1: NeuralClothSim is the first neural cloth simulator representing surface deformation as a neural field. It is supervised for each target scenario with the laws of the Kirchhoff-Love thin shell theory with non-linear strain (left). Once trained, the simulation can be queried continuously and consistently enabling different spatial resolutions (center). NeuralClothSim can also incorporate learnt priors such as material properties that can be edited at test time (right).

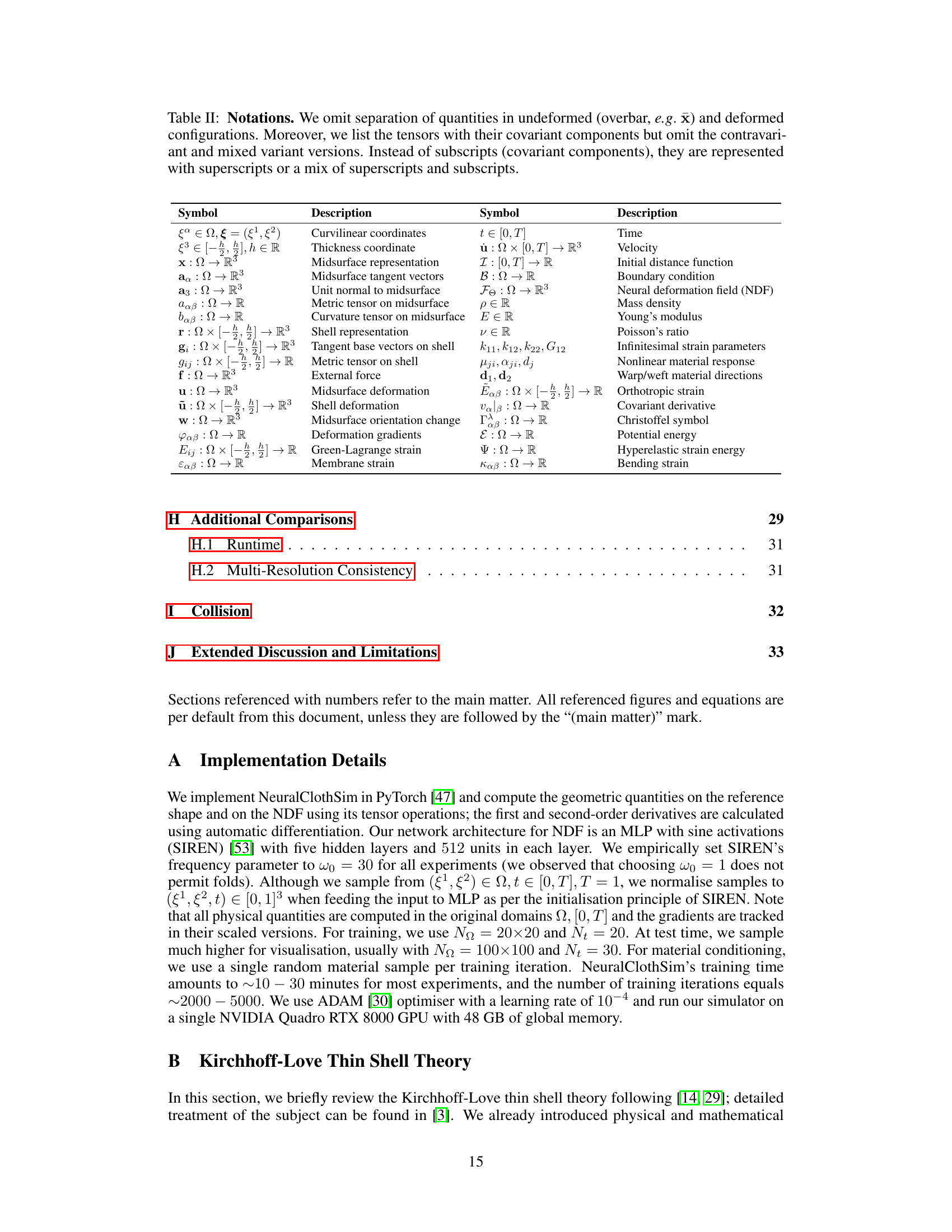

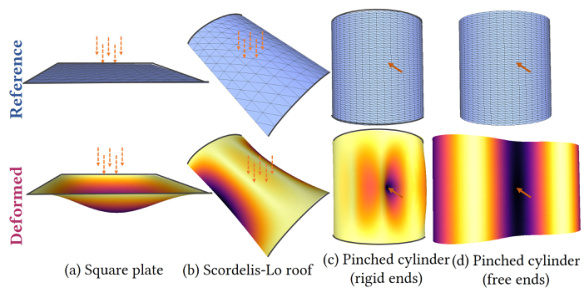

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed NeuralClothSim method against existing methods on the Belytschko obstacle course benchmark. The benchmark involves simulating the deformation of various shapes (square plate, Scordelis-Lo roof, rigid-end cylinder, free-end cylinder) under specific loading conditions. The table shows the displacement results for each method, comparing them to analytical solutions. It also includes ablation studies showing the impact of removing specific components of the NeuralClothSim model (removing periodicity and using GELU activation function). The results demonstrate that NeuralClothSim achieves significantly better accuracy than previous methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative evaluation. We validate the displacements obtained with our method on the Belytschko obstacle course with analytical solutions from [6, 57]. Guo et al. [23] use different material and match the corresponding reference result. Below, we show the ablation. We highlight that our method outperforms prior works and baselines by a large margin.

In-depth insights#

Neural Cloth Sim#

Neural Cloth Sim represents a novel approach to cloth simulation in computer graphics, leveraging the power of neural networks to model fabric deformation. Instead of relying on traditional physics-based methods with discrete mesh representations, Neural Cloth Sim utilizes a continuous coordinate-based neural field, offering several advantages. This approach allows for memory efficiency and adaptive resolution, meaning that the simulation’s detail adapts to the needs of the application, unlike fixed-resolution mesh-based systems. The use of thin-shell theory provides physical accuracy, ensuring realistic fabric behavior, including folds and wrinkles. The neural network’s parameters directly encode surface deformation, enabling the easy integration of Neural Cloth Sim into larger neural architectures and facilitating tasks such as material interpolation and simulation editing. However, the current system lacks collision handling, a crucial aspect of realistic cloth simulation, and there is a need for further research to address this limitation.

Thin Shell Theory#

The thin shell theory, a cornerstone of the research, provides a powerful framework for modeling the deformation of thin, flexible materials like cloth. It elegantly captures the interplay between bending and stretching, essential for realistic cloth simulation. By representing the cloth as a continuous surface, the theory enables accurate modeling of complex folds and wrinkles, avoiding the limitations of discrete mesh-based methods. The adoption of this theory is crucial for the accuracy and realism of the simulated cloth behavior, and its seamless integration into a neural network-based approach is a significant advancement. However, the theory’s application in this context may necessitate approximations, especially when handling non-linear material properties and complex boundary conditions, thereby influencing the overall performance and accuracy of the simulation.

NDF Formulation#

The core of NeuralClothSim lies in its novel continuous coordinate-based surface representation: Neural Deformation Fields (NDFs). Instead of discrete mesh representations, NDFs encode surface deformation implicitly within the weights of a neural network. This allows for memory efficiency and arbitrary spatial resolution without retraining. The NDF formulation cleverly leverages the Kirchhoff-Love thin shell theory, a physically accurate model for cloth deformation. This is done by supervising the NDF equilibrium with the laws of this theory, which involves a non-linear anisotropic material model. The training process minimizes the potential energy functional of the cloth, effectively encoding the physical laws directly into the neural network weights. This continuous approach eliminates the need for re-meshing, providing consistent simulation results regardless of initial spatial resolution. Overall, the NDF formulation is a crucial innovation in physically-based cloth simulation; it bridges the gap between traditional physics-based approaches and the power of modern neural networks, creating a highly efficient and adaptive system.

Simulation Editing#

Simulation editing, as discussed in the context of NeuralClothSim, presents a powerful paradigm shift in cloth simulation. Instead of recomputing entire simulations from scratch with every parameter change, NeuralClothSim allows for iterative refinements. This is achieved by interrupting the training process of the neural deformation field (NDF) at any point and then introducing updated parameters (e.g., external forces, material properties, or reference geometry). This approach offers significant computational savings compared to traditional methods, which require complete recalculation. The core concept leverages the ability of neural networks to learn continuous representations of cloth deformations. By encoding the deformation in the NDF’s weights, editing parameters become straightforward and efficient. The continuous nature of the NDF also allows for seamless transitions between different simulated states, further enhancing the practical usability of this simulation editing capability. This technique has implications far beyond simple parameter adjustments, hinting at potential applications in interactive design and manipulation of virtual garments or other flexible materials.

Future of Sim#

The “Future of Sim” in physically-based simulation hinges on bridging the gap between the accuracy of physics engines and the efficiency of neural networks. Current physics-based simulators, while accurate, struggle with scalability and integration into machine learning pipelines. Neural approaches offer speed and efficiency but often lack the physical fidelity needed for realistic simulations. The future likely involves hybrid models, combining the strengths of both approaches. This might entail using neural networks to learn complex material behaviors or to accelerate computationally expensive steps within traditional physics solvers. Furthermore, continuous representations like neural fields could revolutionize simulation by removing the limitations of discrete meshes, enabling adaptive resolution and easier integration with other neural techniques. Ultimately, the “Future of Sim” likely involves more versatile and interactive simulators that seamlessly integrate with design and creative workflows, facilitating rapid prototyping and exploration in a wide range of fields. The focus will shift toward improved simulation editing tools that enable direct manipulation and modification of simulations without needing to rerun the entire process, speeding up design cycles considerably. The ability to efficiently handle complex phenomena like large-scale simulations and interactions will also be critical for the success of next-generation simulators.

More visual insights#

More on figures

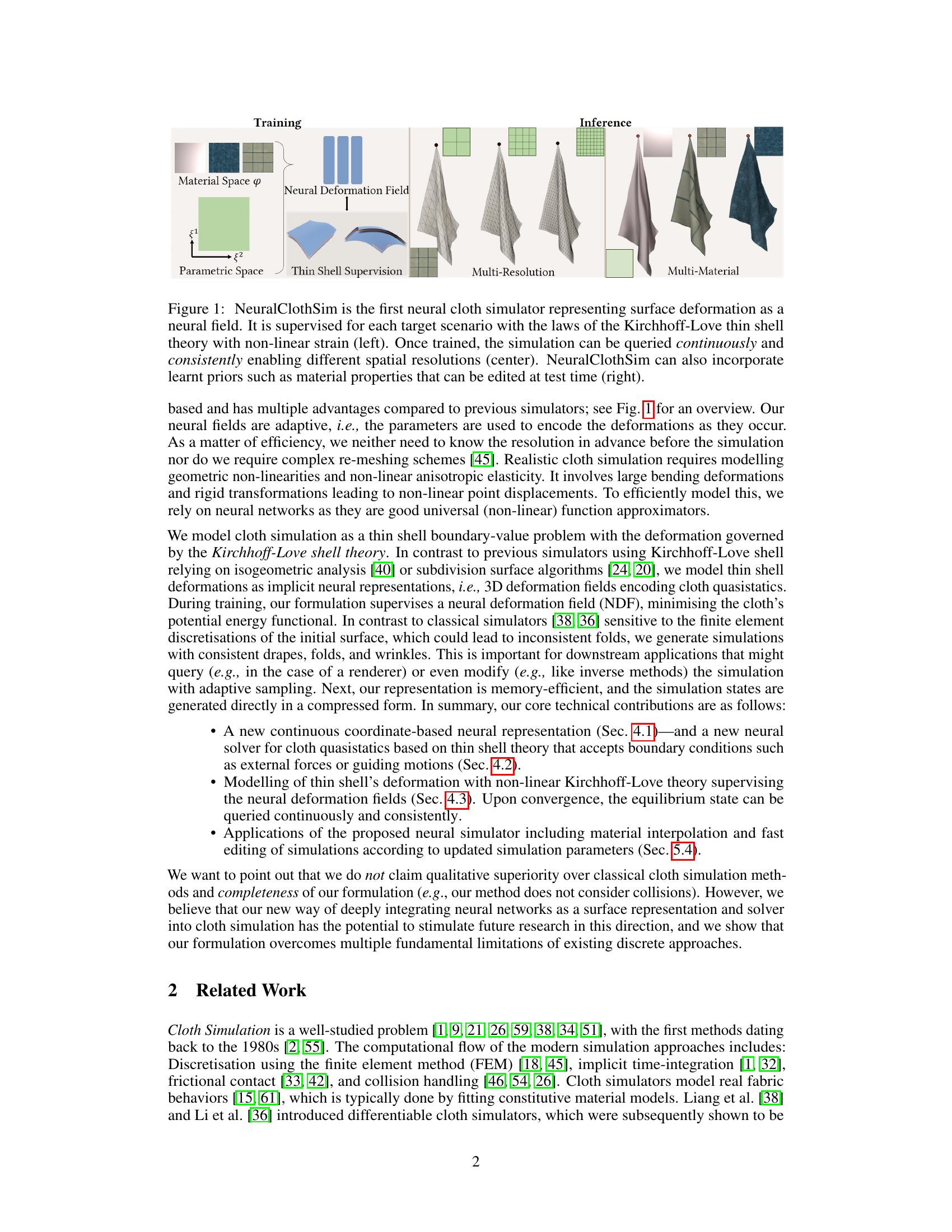

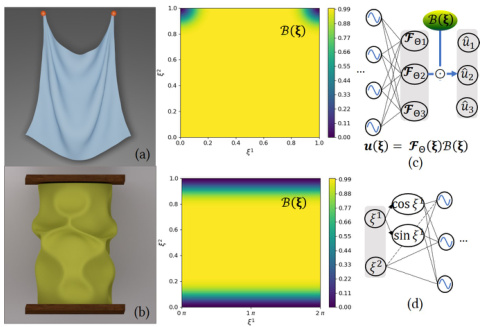

🔼 This figure shows the NeuralClothSim architecture and workflow. It starts with input data: the reference state of the cloth (its initial shape), material properties (like stiffness and elasticity), boundary conditions (how the cloth is constrained), and external forces (gravity, wind, etc.). This data is fed into a neural network that learns a neural deformation field (NDF). The NDF is a function that encodes the deformation of the cloth’s surface. The network is trained by minimizing the cloth’s potential energy, ensuring the simulation adheres to the laws of the Kirchhoff-Love thin shell theory. Once trained, the NDF can be used to query the deformed state of the cloth at any point, enabling continuous and consistent simulation.

read the caption

Figure 3: NeuralClothSim takes as input a thin shell in the reference state and its material properties, boundary motion and external forces. It then learns an NDF, i.e., a coordinate-based implicit 3D deformation field. At inference, NDF can be continuously queried for the deformed state of the surface at equilibrium using curvilinear coordinates from the parametric domain. We use the Kirchhoff-Love thin shell modelling to supervise the cloth quasistatics with the potential energy functional.

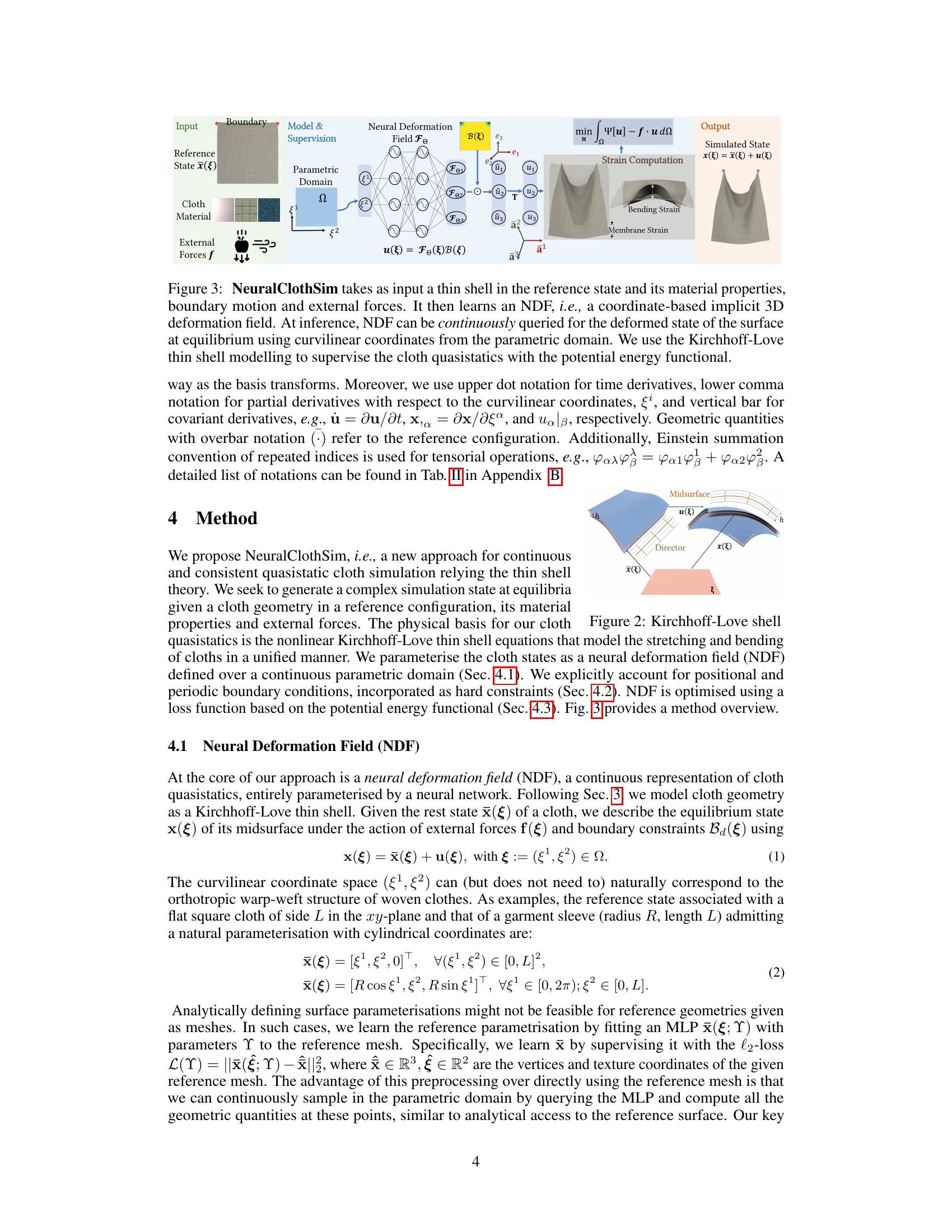

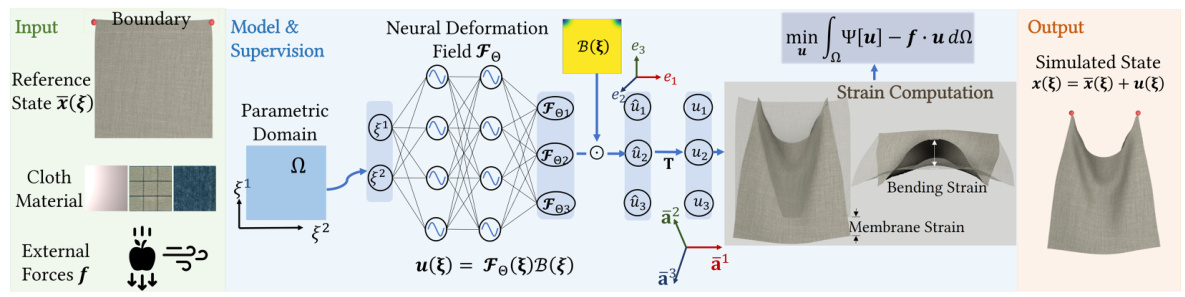

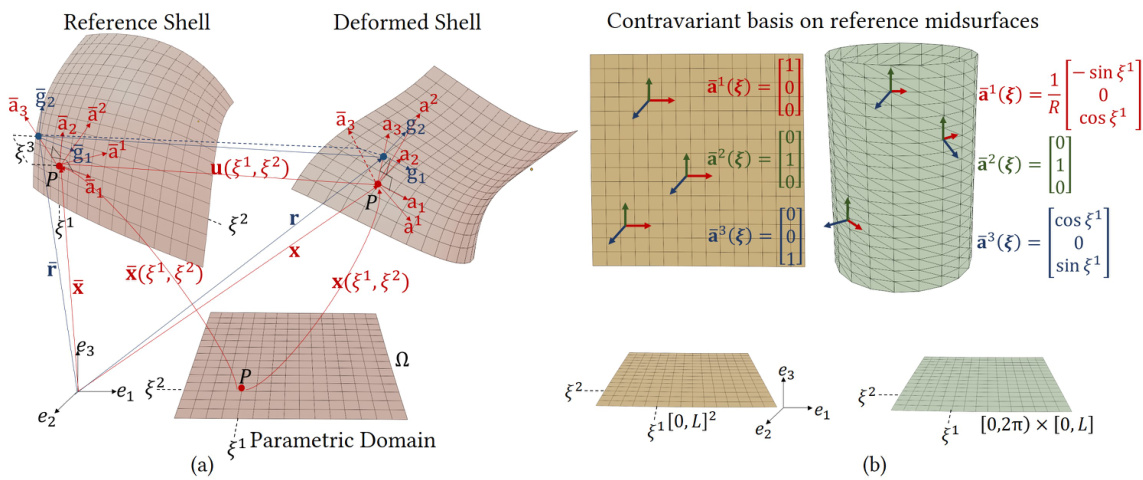

🔼 This figure shows a schematic representation of a Kirchhoff-Love thin shell. Panel (a) illustrates the key components: the midsurface, director vector, and thickness coordinate. Panel (b) shows the contravariant basis vectors for the midsurface in the reference configuration, highlighting how they change with the geometry of the shell (e.g., a cylinder).

read the caption

Figure I: (a) Kirchhoff-Love thin shell. A thin shell can be kinematically described by the midsurface (here: reference and deformed midsurfaces) and the director (here, ā3). Any material point P on the midsurface is then parameterised with curvilinear coordinates (§¹, §2), whereas a point on the shell continuum requires an additional thickness coordinate §3. Geometric quantities on the midsurface (off the midsurface or on the shell continuum) are coloured red (blue). (b) Contravariant basis for midsurfaces in the reference configuration. While a local contravariant basis coincides with the global Cartesian coordinate system for a planar reference shell, such a basis varies in magnitude and direction across any circular section of the cylinder. Local basis relies on the surface parameterisation, therefore the derived basis vectors need not be normalised (notice how ā¹(g) scales inversely with the radius).

🔼 This figure shows a schematic overview of the NeuralClothSim pipeline. It starts with the training phase (left) where a neural deformation field (NDF) is trained based on the Kirchhoff-Love thin shell theory to represent surface deformation. The middle panel demonstrates that, once trained, the NDF can be queried for the simulation state at any resolution. Finally, the right panel shows that material properties can be incorporated as learnable priors and can be edited at test time. In essence, this illustrates that NeuralClothSim is a continuous and memory-efficient cloth simulator that offers resolution adaptation and material editing capabilities.

read the caption

Figure 1: NeuralClothSim is the first neural cloth simulator representing surface deformation as a neural field. It is supervised for each target scenario with the laws of the Kirchhoff-Love thin shell theory with non-linear strain (left). Once trained, the simulation can be queried continuously and consistently enabling different spatial resolutions (center). NeuralClothSim can also incorporate learnt priors such as material properties that can be edited at test time (right).

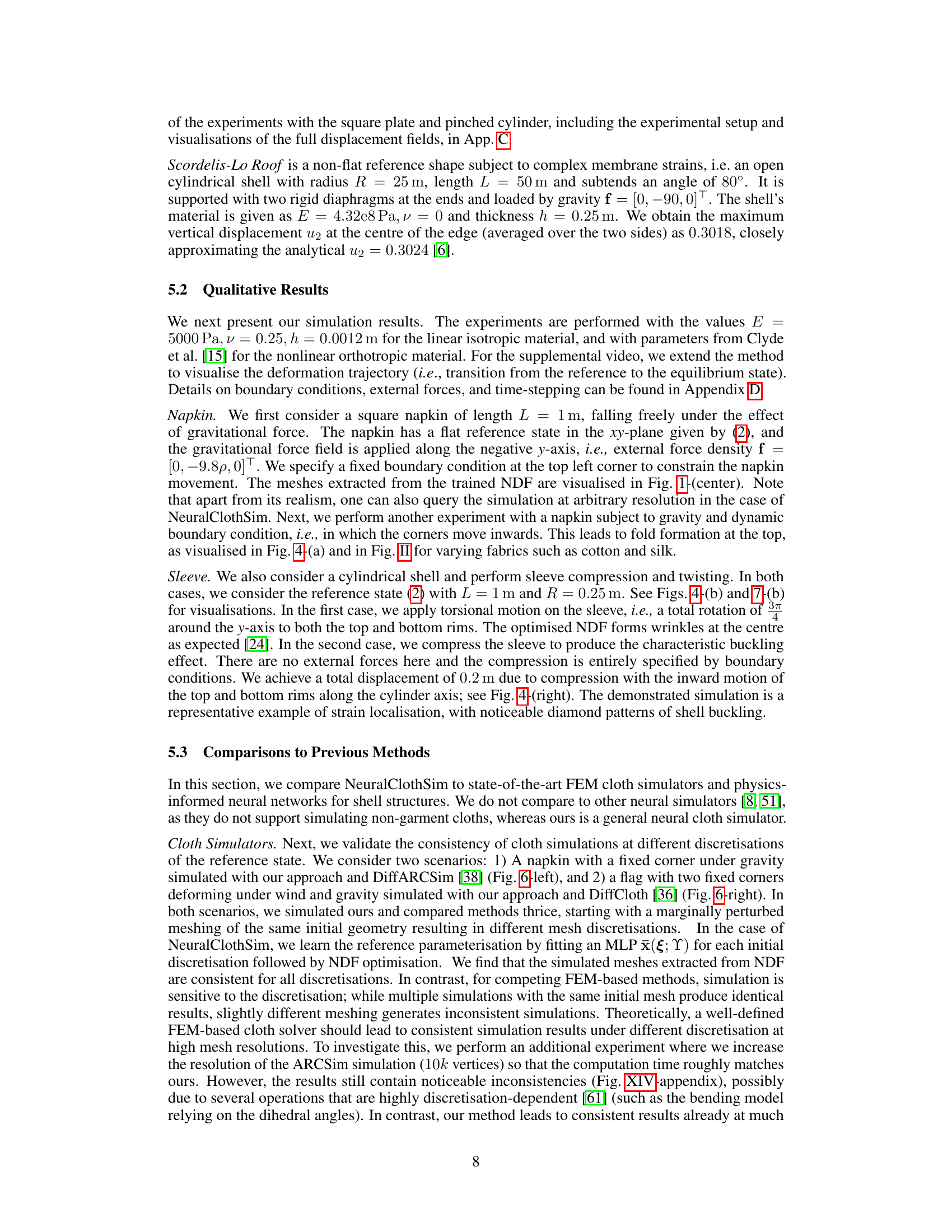

🔼 This figure shows the results of the Belytschko obstacle course, a benchmark test for cloth simulation. The course includes four scenarios: a square plate, a Scordelis-Lo roof, and a pinched cylinder with both rigid and free ends. The images display both the reference (undeformed) and deformed states of each structure under load, visualized with a color map indicating displacement. The results demonstrate the accuracy of the NeuralClothSim method in modeling the deformations of these structures.

read the caption

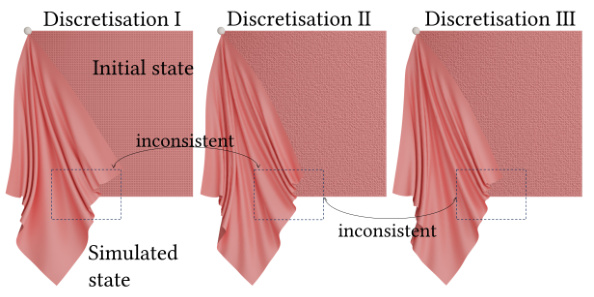

Figure 5: Belytschko obstacle course for which we generate accurate displacements (rescaled for better visualisation).

🔼 This figure compares the simulation consistency of the proposed NeuralClothSim method with two existing FEM-based cloth simulators (DiffARCSim and DiffCloth) across different initial mesh discretizations. The top row shows the initial states of the cloth simulation with three different discretizations. The middle and bottom rows display the resulting simulated states using the three different methods. The results demonstrate that FEM-based simulators produce inconsistent results with different folds and wrinkles for different mesh discretizations, while NeuralClothSim consistently provides similar results despite variations in mesh discretization. This highlights the advantage of the continuous neural field representation in achieving consistent cloth simulations.

read the caption

Figure 6: Simulation consistency. At different initial state discretisations, FEM-based simulators led to inconsistencies with often differences in the folds or wrinkles. In contrast, ours overfits an MLP to the reference mesh and encodes the surface evolution using another MLP (continuous neural fields).

🔼 This figure compares the results of sleeve twisting simulations between Bastek et al.’s method and the proposed NeuralClothSim. Bastek et al.’s method produces a smooth, wrinkle-free result, whereas NeuralClothSim generates a realistic result with wrinkles, similar to those obtained by other physically based cloth simulators mentioned in the paper.

read the caption

Figure 7: Comparison to Bastek et al. on sleeve twisting. While the cylinder in (a) twists without wrinkles, our result (b) is correctly wrinkled, similar to [24].

🔼 This figure shows a thin shell in the reference and deformed states, along with a visualization of the contravariant basis on reference midsurfaces. Panel (a) illustrates the key components of the Kirchhoff-Love thin shell model: the midsurface, the director, and the parametric domain. Panel (b) demonstrates how the contravariant basis changes for different reference surface geometries (planar vs. cylindrical).

read the caption

Figure I: (a) Kirchhoff-Love thin shell. A thin shell can be kinematically described by the midsurface (here: reference and deformed midsurfaces) and the director (here, ā3). Any material point P on the midsurface is then parameterised with curvilinear coordinates (§¹, §2), whereas a point on the shell continuum requires an additional thickness coordinate §3. Geometric quantities on the midsurface (off the midsurface or on the shell continuum) are coloured red (blue). (b) Contravariant basis for midsurfaces in the reference configuration. While a local contravariant basis coincides with the global Cartesian coordinate system for a planar reference shell, such a basis varies in magnitude and direction across any circular section of the cylinder. Local basis relies on the surface parameterisation, therefore the derived basis vectors need not be normalised (notice how ā¹(g) scales inversely with the radius).

🔼 This figure demonstrates the simulation results of a 1m x 1m napkin with its corners fixed at 60cm apart, using different material models. The models used are: linear isotropic, linear anisotropic St.Venant-Kirchhoff (for canvas), and non-linear anisotropic models (for canvas, silk, and cotton). The results show that the choice of material model significantly affects the final equilibrium state of the napkin.

read the caption

Figure II: Material model. Simulation of stable equilibria of 1 m × 1 m napkin with corners held 60 cm apart. From left to right, we visualise linear isotropic, linear anisotropic St.Venant-Kirchhoff (canvas), and non-linear anisotropic canvas, silk and cotton materials from Clyde et al. [15].

🔼 This figure shows two examples of napkin simulations upon convergence under gravity. The left image (a) demonstrates a point constraint where one corner of the napkin is fixed. The right image (b) shows an edge constraint where one edge of the napkin is fixed along a rod. Both simulations illustrate the natural draping of the cloth under the influence of gravity.

read the caption

Figure IV: Napkin simulation upon convergence under gravity with non-boundary constraints.

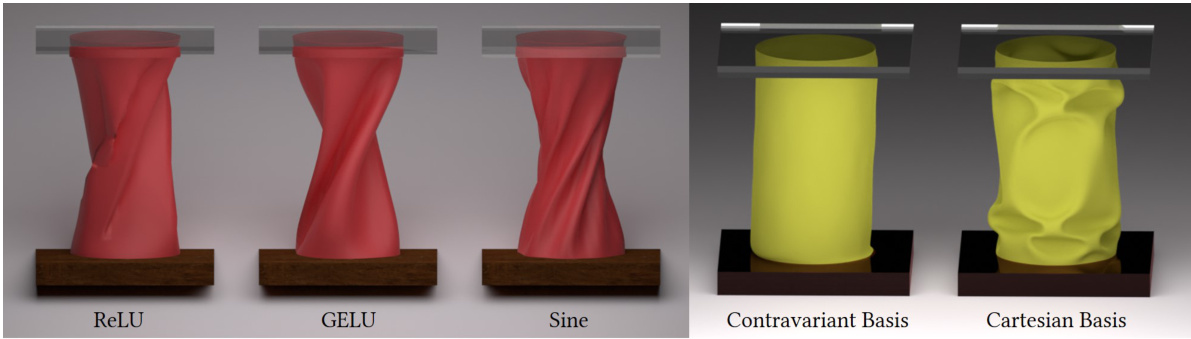

🔼 This figure is composed of two parts. The left part shows the simulation results using different activation functions (ReLU, GELU, and Sine) for sleeve twisting. The right part demonstrates the comparison of using contravariant and Cartesian basis for NDF output. It indicates that using the Cartesian coordinate system results in better-conditioned simulations compared to using the local contravariant coordinate system.

read the caption

Figure V: Activations (left). Results of our method with different activation functions (ReLU, GELU and Siren). Contravariant vs Cartesian basis (right). Prediction of NDF output in the Cartesian coordinate system is well conditioned compared to the local contravariant coordinate system.

🔼 This figure shows an ablation study on boundary conditions. It compares the results of using soft constraints (where boundary conditions are incorporated as loss terms), hard constraints (where boundary conditions are directly enforced), and no constraints at all. The top row demonstrates Dirichlet boundary conditions, while the bottom row shows periodic boundary conditions. The results illustrate the effectiveness of hard constraints in enforcing boundary conditions accurately compared to soft constraints or the absence of constraints.

read the caption

Figure VI: Ablation study for boundary conditions, with Dirichlet (top) and periodic (bottom) boundary conditions.

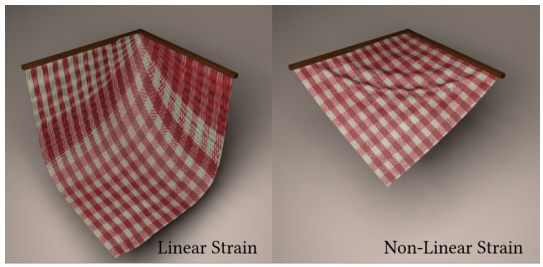

🔼 This figure compares the results of cloth simulation using linear and non-linear strain models. The left image shows a simulation with a linear strain model, resulting in unrealistic folds and wrinkles. The right image shows a simulation with a non-linear strain model, which produces more realistic and natural-looking folds and wrinkles, demonstrating the importance of non-linearity in accurate cloth simulation.

read the caption

Figure VII: Linear vs non-linear strain. We demonstrate napkin drooping under a downward force. Kirchhoff-Love strain is inherently highly non-linear.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the simulation editing capabilities of NeuralClothSim. A simulation is first pre-trained to equilibrium with fixed initial conditions (reference state and external force). Then, either the external force or the reference pose is gradually changed. The pre-trained NDF is fine-tuned with the updated parameters, resulting in new, physically plausible simulations. The process is significantly faster than training from scratch.

read the caption

Figure VIII: Simulation editing with NeuralClothSim. We show an example of a simulation pre-trained with a fixed reference state and external force. Once converged, we fine-tune the NDF with smoothly varying external force (top) or the pose of the reference geometry (bottom) in each iteration. Fine-tuning a pre-trained NDF with updated design parameters is faster and offers querying of physically-plausible intermediate simulations.

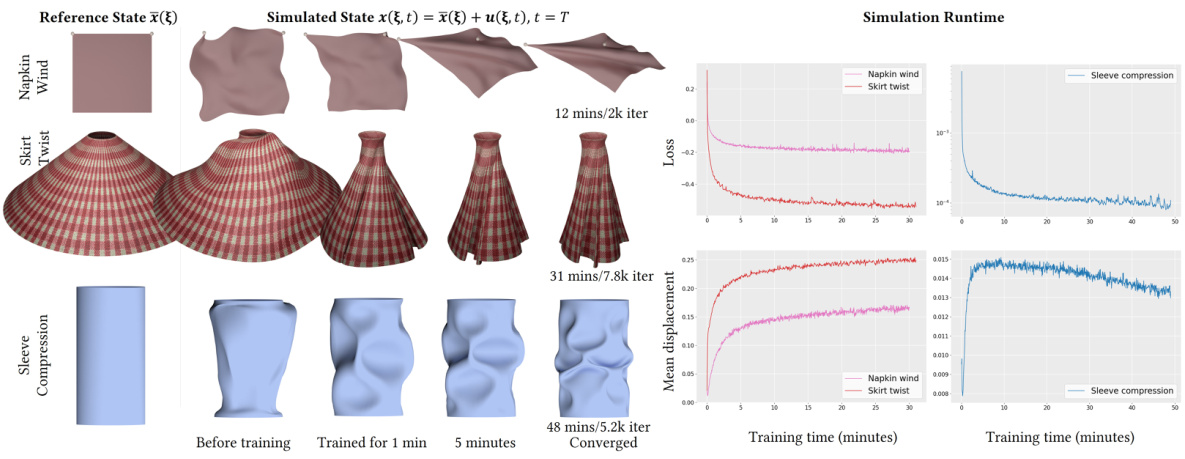

🔼 This figure analyzes the runtime performance of NeuralClothSim. The left side shows the evolution of the simulated state (at the last time step, T=1) throughout the training process. It demonstrates how the simulation gradually refines its results as training progresses. The right side presents graphs illustrating the convergence of the Neural Deformation Field (NDF) loss and mean displacement during training. These plots show the NDF loss decreasing and mean displacement converging towards a stable value over the course of training, indicating improved accuracy and refinement of the simulation. Three different simulation scenarios are shown: napkin wind, skirt twist, and sleeve compression, each demonstrating the runtime and convergence behavior of NeuralClothSim.

read the caption

Figure IX: Runtime analysis of NeuralClothSim. On the left, we visualise the evolution of the last frame (T = 1) over the training iterations. On the right, the plot shows NDF convergence as a function of training time leading to refined simulations.

🔼 This figure analyzes how the number of training points used in the NeuralClothSim model affects its performance. The top graph shows the training loss, illustrating the convergence behavior with varying numbers of sample points. The bottom graph displays the mean displacement, showcasing how accurately the model predicts cloth deformation. The image on the right provides a visual comparison of simulated cloth drapes at two different sampling densities (NΩ = 5 and NΩ = 25), highlighting the visual impact of the sampling strategy on simulation quality. This demonstrates the trade-off between computational cost and accuracy in the model.

read the caption

Figure X: Analysis of the sampling strategies. We show the influence of the number of training points on the performance of our method.

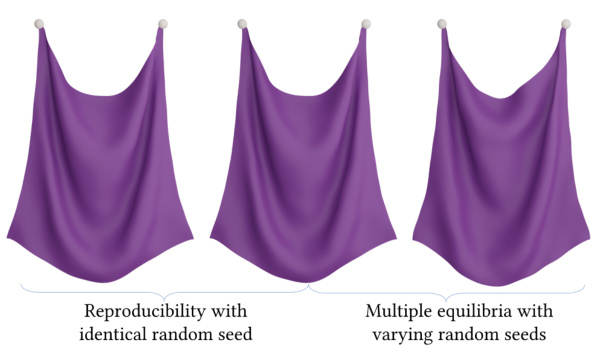

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of random seed on the simulation results. The leftmost image shows that using the same random seed produces reproducible results. However, the other two images, generated with varying random seeds, illustrate the non-uniqueness of cloth simulation, highlighting multiple stable equilibrium configurations for the same initial conditions. This demonstrates the ability of the NeuralClothSim model to capture this inherent non-determinism in realistic cloth behavior.

read the caption

Figure XI: NDF weight initialisation allows us to control the simulation outcome. We can generate multiple valid equilibrium solutions or reproduce a simulation.

🔼 This figure compares the runtime performance of NeuralClothSim with DiffARCSim, a state-of-the-art physics-based cloth simulator. It shows how the simulation quality changes for both methods as the computational budget (time) is reduced. DiffARCSim, which uses a traditional time-stepping approach, struggles to produce high-quality simulations with limited time, resulting in low-resolution or incomplete simulations. In contrast, NeuralClothSim’s neural field approach allows it to produce partially converged, usable simulations even with significantly less computation time, maintaining good visual quality across different resolutions.

read the caption

Figure XII: Runtime comparison of DiffARCSim [38] and our approach. Like most classical simulators, DiffARCSim integrates forward in time, solving for a 3D deformation field at each time step, in contrast to our approach which optimises for the 4D spatio-temporal NDF. With decreasing computational budget, DiffARCSim produces converged simulated states of the cloth at low resolutions or only early frames at high resolutions. On the other hand, NeuralClothSim offers partially converged simulations at arbitrary resolutions as the computational budget decreases.

🔼 This figure compares the simulation consistency of NeuralClothSim with other state-of-the-art differentiable cloth simulators (DiffARCSim and DiffCloth) when the spatial resolution changes. Classical methods produce inconsistent results when the resolution changes, while NeuralClothSim maintains consistent results. This highlights the benefit of NeuralClothSim’s continuous representation.

read the caption

Figure XIII: Spatial and temporal surface consistency of state-of-the-art differentiable simulators and our approach. Classical simulators such as ARCSim [38] and DiffCloth [36] reproduce simulation outcomes when re-running at the same resolution. However, changing spatio-temporal resolution requires multiple runs and generates possibly different folds or wrinkles instead of refining (or previewing) the geometry. Since we learn a continuous neural parameterised model, a converged (or partially converged) NDF provides consistent simulation when queried at different spatio-temporal inputs. Note that NeuralClothSim does not provide consistent refinement as a function of computation time (no speed vs fidelity trade-off), but rather consistent simulation with respect to the spatio-temporal sampling (at a given computational budget).

🔼 This figure compares the simulation results of NeuralClothSim with those of two state-of-the-art FEM-based cloth simulators (DiffARCSim and DiffCloth) under different initial mesh discretisations. It highlights NeuralClothSim’s key advantage: consistency across different mesh resolutions. While the FEM methods show inconsistent results (folds and wrinkles differ with varying meshing), NeuralClothSim’s continuous neural field representation consistently produces the same simulation outcome regardless of initial discretisation, making it robust and reliable for downstream applications.

read the caption

Figure 6: Simulation consistency. At different initial state discretisations, FEM-based simulators led to inconsistencies with often differences in the folds or wrinkles. In contrast, ours overfits an MLP to the reference mesh and encodes the surface evolution using another MLP (continuous neural fields).

🔼 This figure shows the limitations of the proposed NeuralClothSim approach. Specifically, it highlights that the method does not currently handle collisions, contacts, or friction. The two example images depict situations where the model’s inability to handle these aspects leads to less realistic simulations.

read the caption

Figure XVI: Limitations. Our approach does not handle collisions, contacts and frictions at the moment, since the focus of this work is on the fundamental challenges of developing a neural cloth simulator. These examples show inaccuracies due to the simplifications made in one possible extension (65).

🔼 This figure compares the runtime performance of NeuralClothSim and DiffARCSim for cloth simulation tasks with varying computational budgets (1, 2, 6, and 10 minutes). It shows that DiffARCSim, a classical forward-in-time simulator, struggles to produce fully converged results at higher resolutions within the given time constraints. In contrast, NeuralClothSim, which optimizes a 4D spatio-temporal neural deformation field (NDF), provides partially converged results even at low resolutions, demonstrating its efficiency in handling limited computational resources.

read the caption

Figure XII: Runtime comparison of DiffARCSim [38] and our approach. Like most classical simulators, DiffARCSim integrates forward in time, solving for a 3D deformation field at each time step, in contrast to our approach which optimises for the 4D spatio-temporal NDF. With decreasing computational budget, DiffARCSim produces converged simulated states of the cloth at low resolutions or only early frames at high resolutions. On the other hand, NeuralClothSim offers partially converged simulations at arbitrary resolutions as the computational budget decreases.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed NeuralClothSim method against existing state-of-the-art methods on the Belytschko obstacle course. The comparison focuses on the accuracy of displacement predictions for various shapes (square plate, Scordelis-Lo roof, rigid-end cylinder, and free-end cylinder). It shows the error of each method compared to analytical ground truth values, demonstrating a significant performance improvement of NeuralClothSim. Ablation studies are also included, showing the impact of various components of the method on accuracy.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative evaluation. We validate the displacements obtained with our method on the Belytschko obstacle course with analytical solutions from [6, 57]. Guo et al. [23] use different material and match the corresponding reference result. Below, we show the ablation. We highlight that our method outperforms prior works and baselines by a large margin.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of the proposed NeuralClothSim method against existing state-of-the-art methods on the Belytschko obstacle course. The obstacle course is a benchmark problem consisting of several test cases with known analytical solutions, allowing for precise evaluation of simulation accuracy. The table shows the error for each method on four different test cases, demonstrating that NeuralClothSim significantly outperforms prior methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative evaluation. We validate the displacements obtained with our method on the Belytschko obstacle course with analytical solutions from [6, 57]. Guo et al. [23] use different material and match the corresponding reference result. Below, we show the ablation. We highlight that our method outperforms prior works and baselines by a large margin.

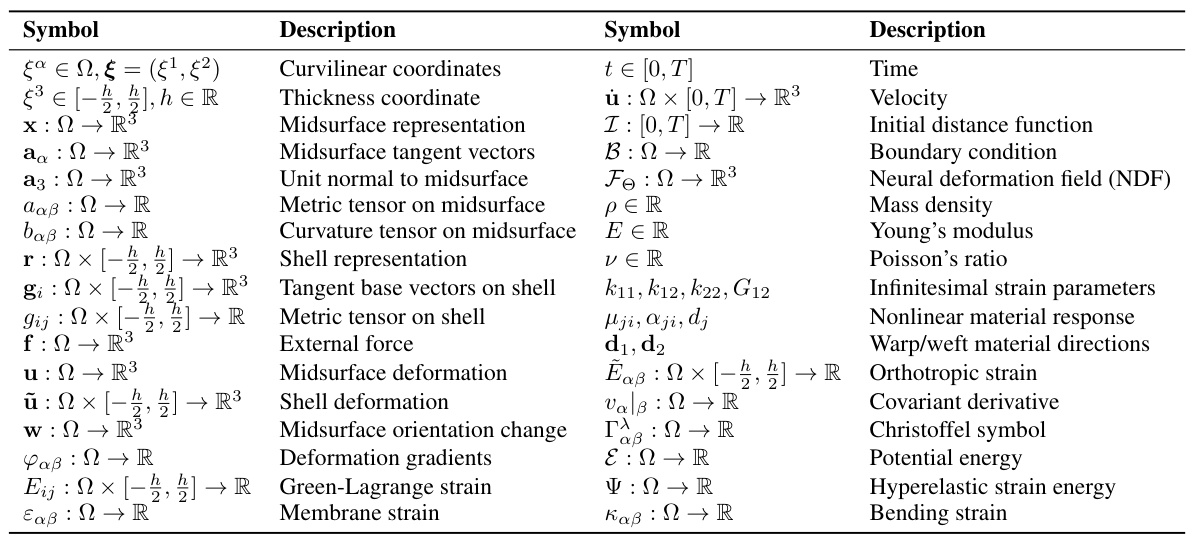

Full paper#