↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

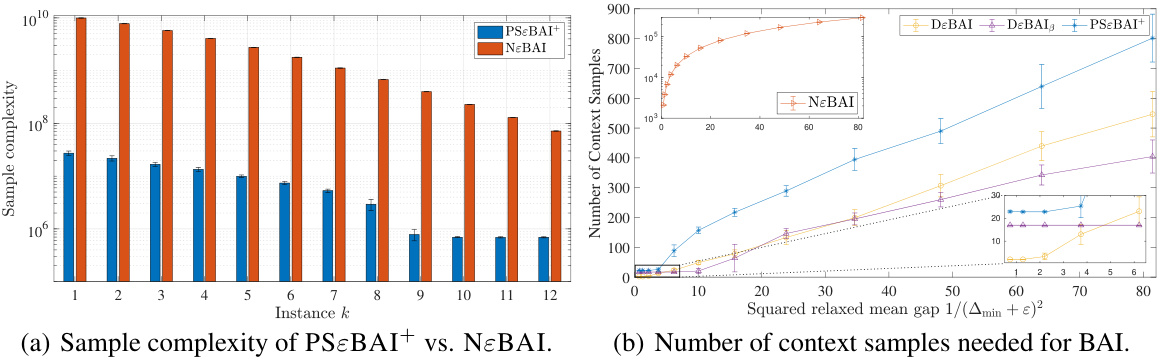

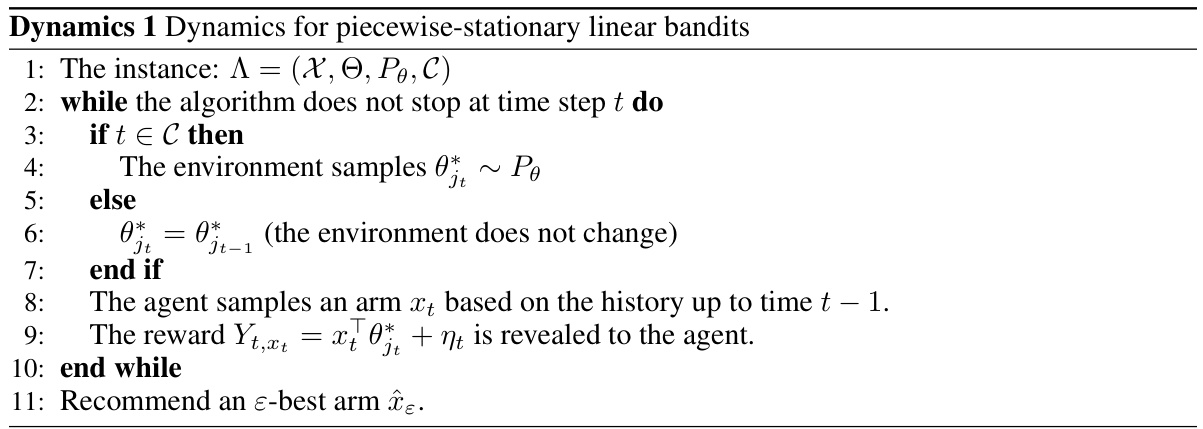

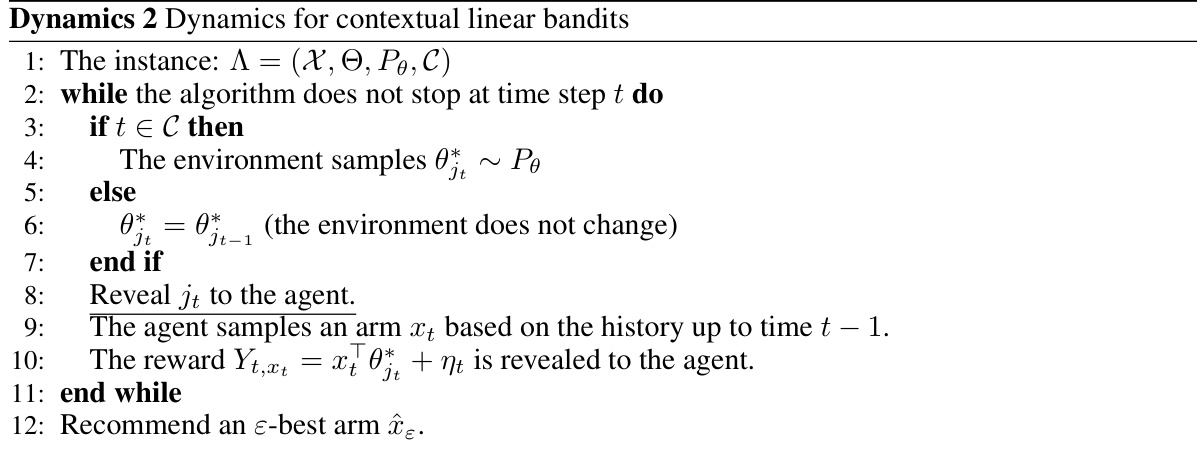

Many real-world problems involve decision-making in dynamic environments, where the reward for each action can change over time. Traditional multi-armed bandit algorithms struggle in such non-stationary settings. This paper addresses this challenge by introducing the piecewise stationary linear bandit problem, where the environment’s characteristics shift at random changepoints. Existing algorithms fail to efficiently handle these changes.

This research introduces a novel algorithm, PSɛBAI+, specifically designed to address the limitations of existing methods in the piecewise stationary linear bandit setting. PSɛBAI+ cleverly combines changepoint detection and context alignment to adapt to the changing environment. The paper rigorously proves that PSɛBAI+ achieves near-optimal sample complexity, meaning it identifies the best action with minimal data. Numerical experiments demonstrate that PSɛBAI+ significantly outperforms naive methods, showcasing its practical efficiency and the effectiveness of its unique approach.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on multi-armed bandit problems in non-stationary environments. It introduces a novel model and algorithm, addressing a significant gap in existing research. The near-optimal algorithm presented offers practical solutions for real-world applications and inspires further exploration of efficient solutions for similar problems.

Visual Insights#

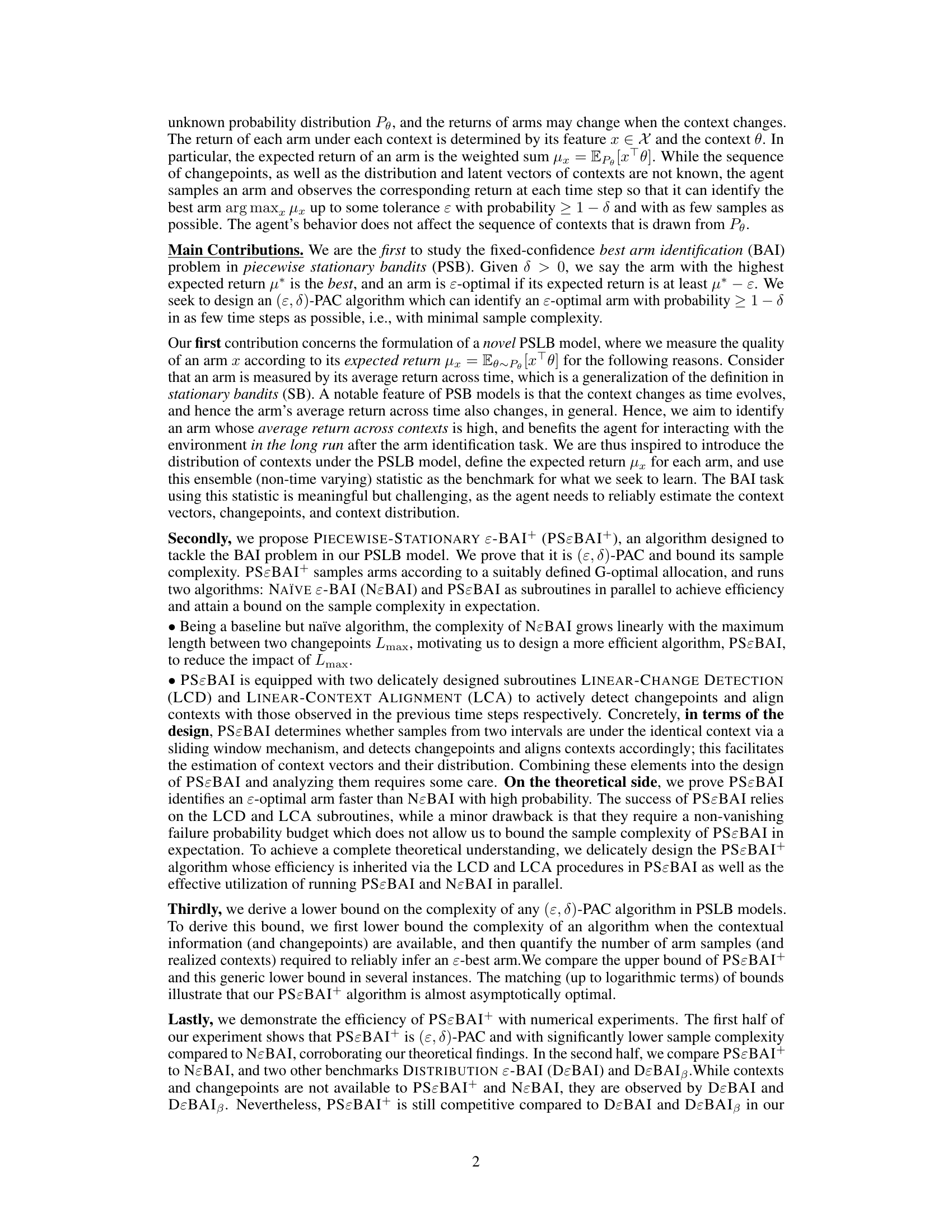

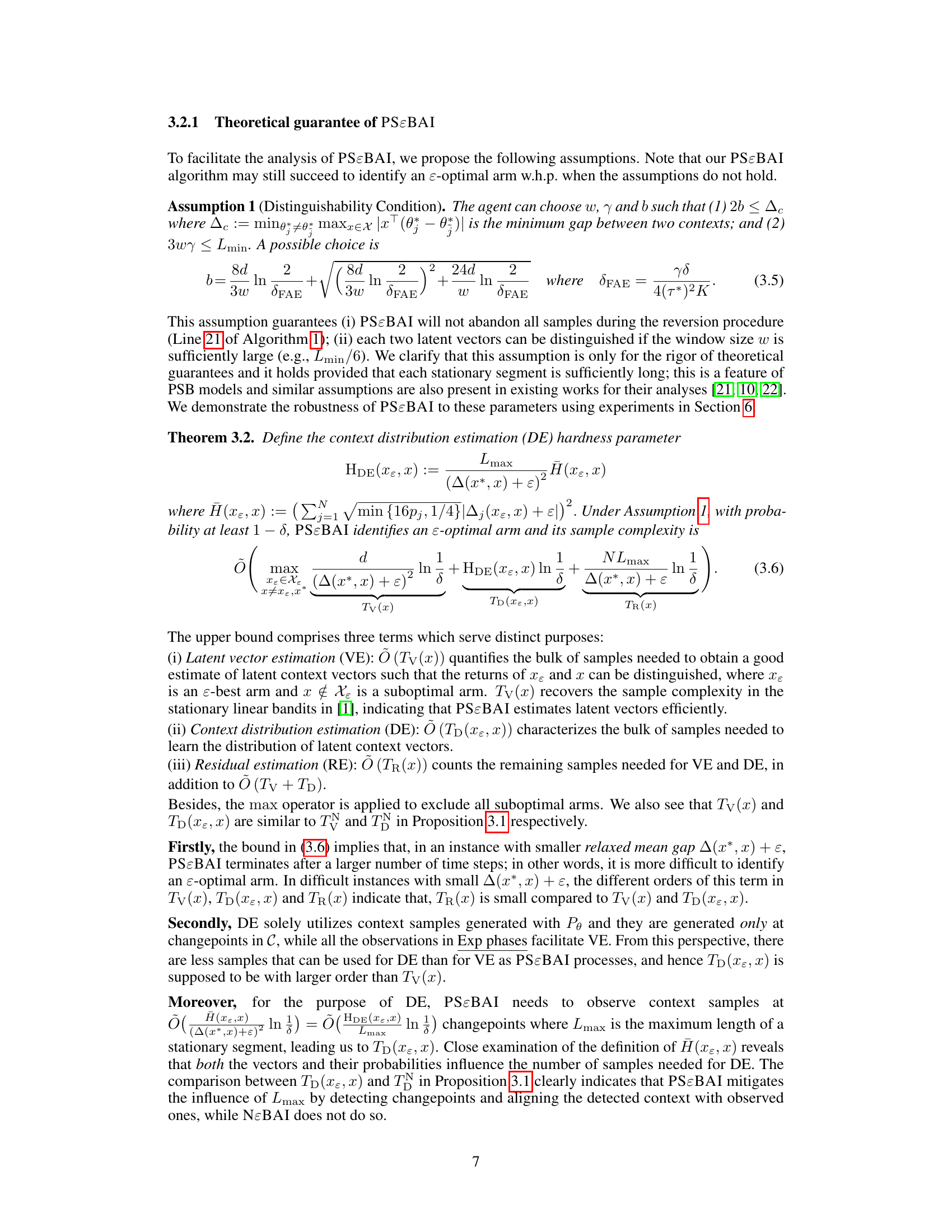

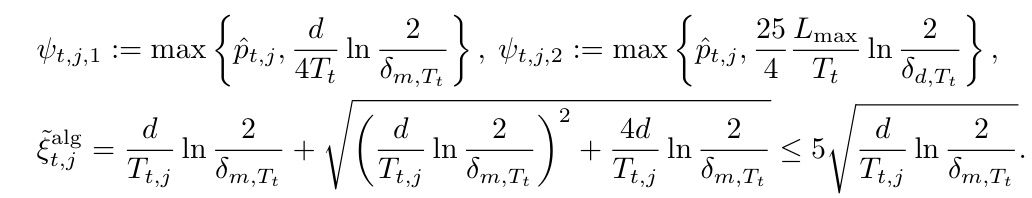

This figure illustrates the two scenarios in the piecewise stationary linear bandit, where a change detection is performed every γ steps. (a) shows a scenario where no change point is detected by the LCD subroutine, and thus the exploration phase continues. The w most recent CD samples are used to determine this. (b) shows a scenario where a change point is detected by LCD, and thus the context alignment phase is entered. The statistics from the past w steps are discarded in this case, and a new exploration phase is started.

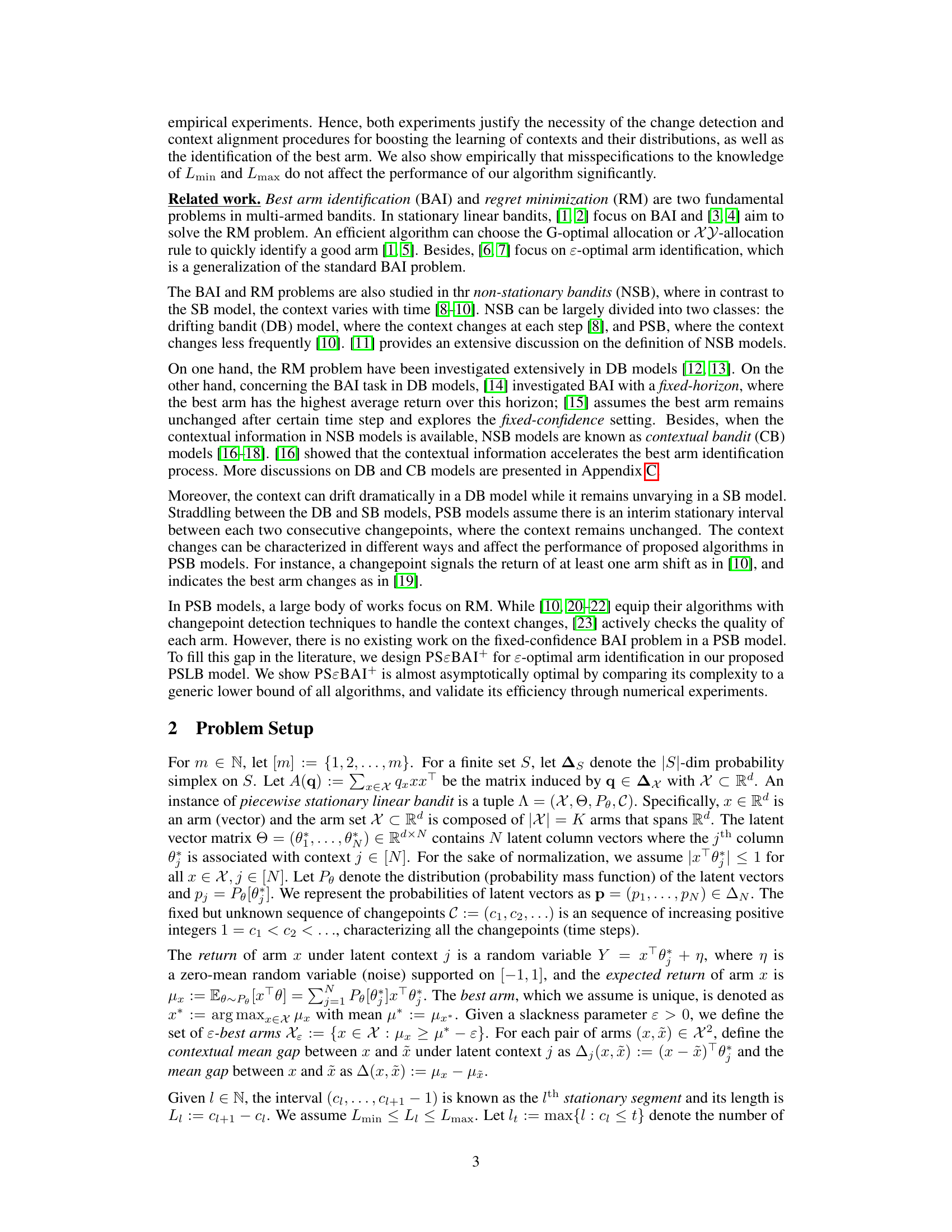

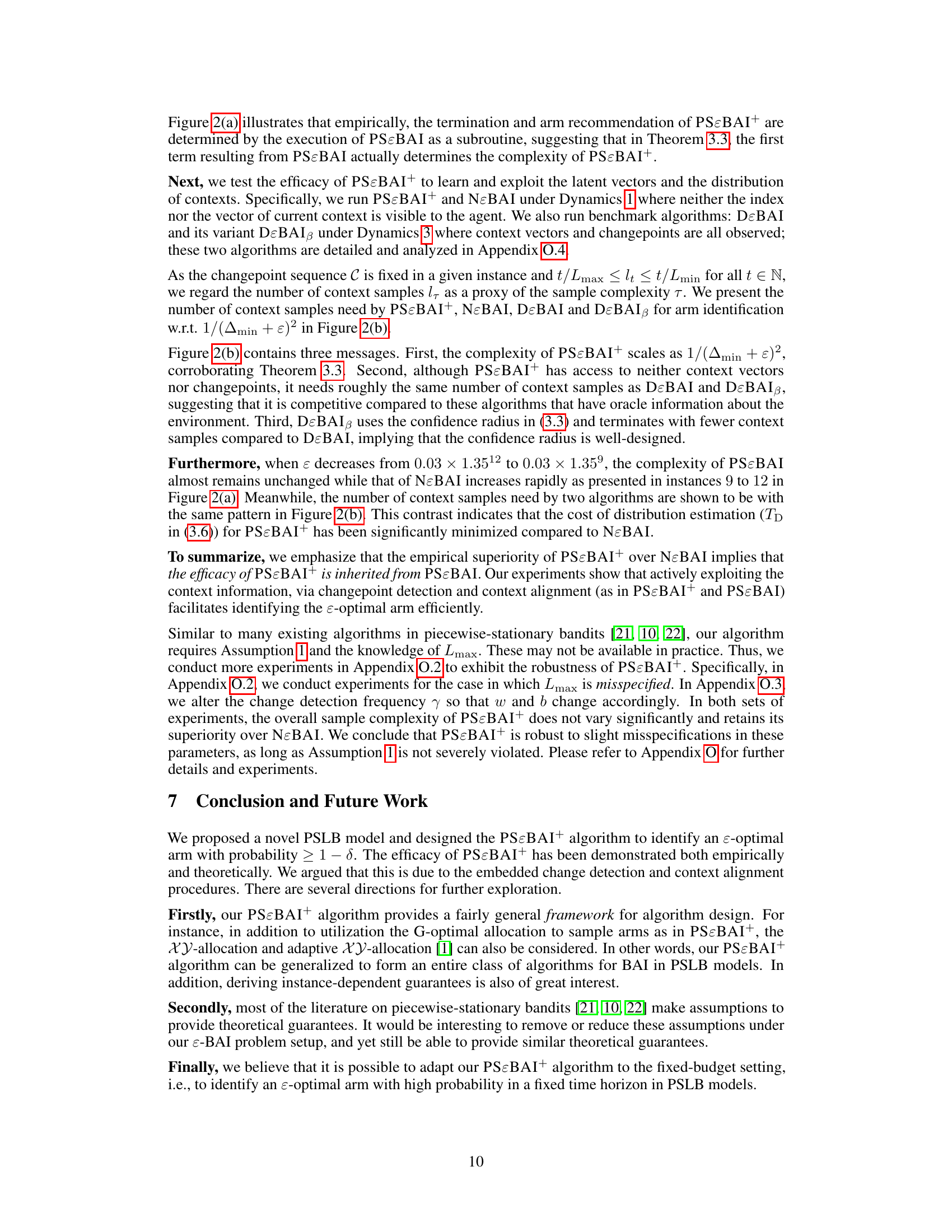

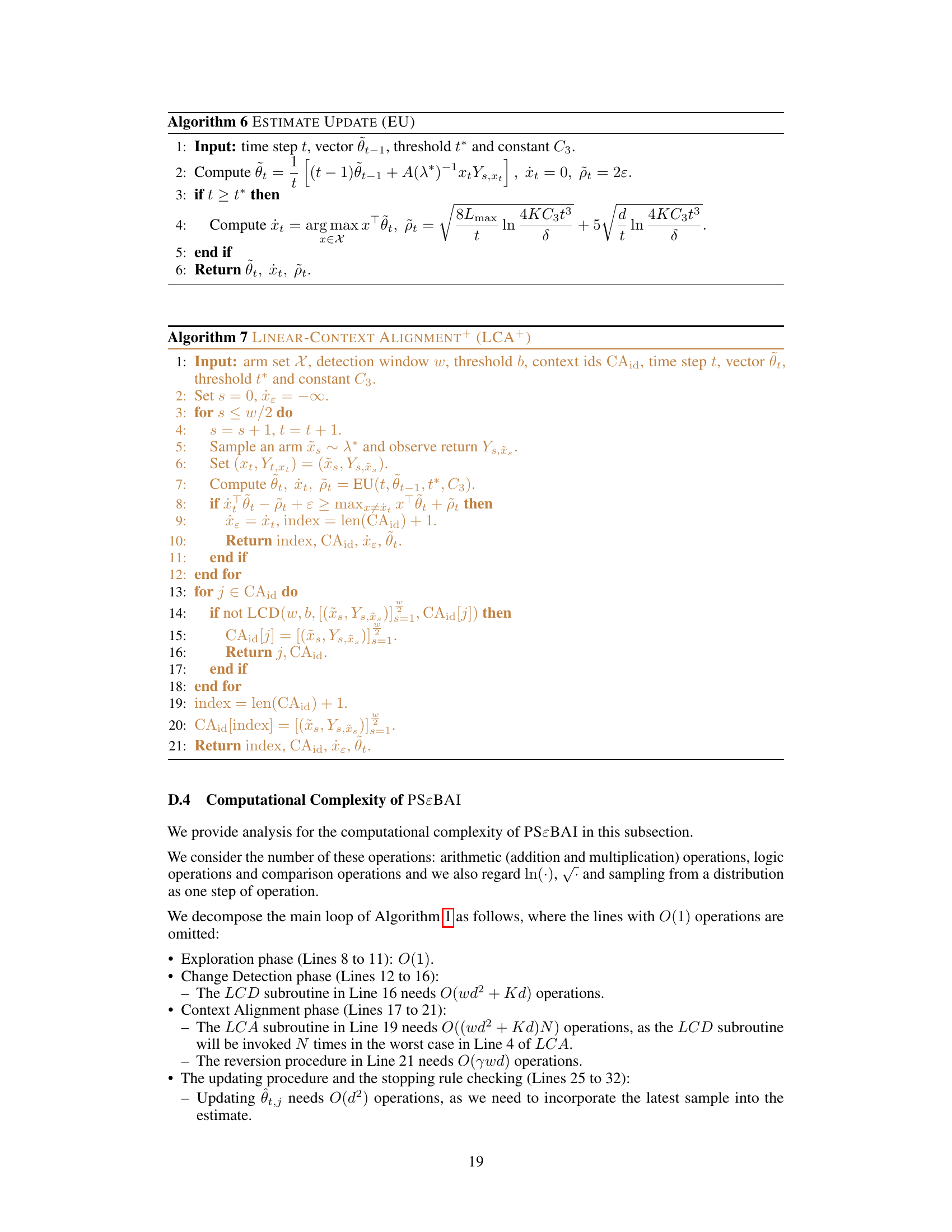

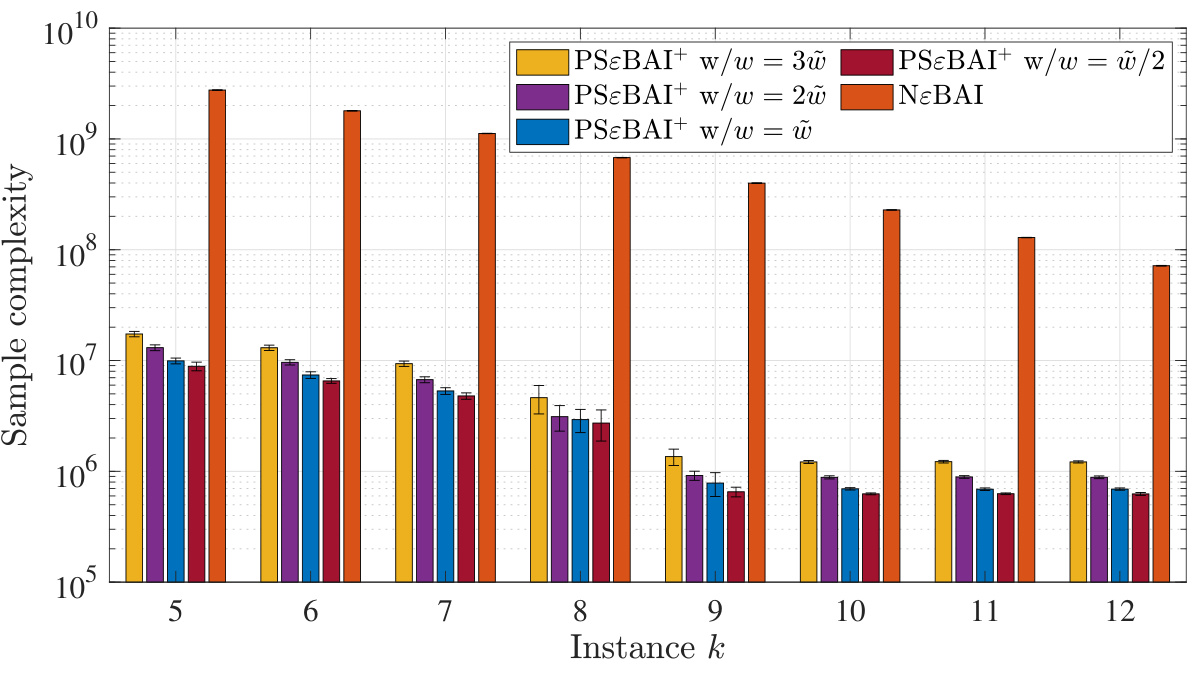

Figure 2 presents the experimental results of the paper. Panel (a) shows a comparison of the sample complexity of PSɛBAI+ versus the naive baseline algorithm, NɛBAI, across multiple problem instances. The plot demonstrates that PSɛBAI+ achieves significantly lower sample complexity than NɛBAI. Panel (b) illustrates the number of context samples required for best arm identification by PSɛBAI+, NɛBAI, DɛBAI, and DɛBAIβ as a function of the squared relaxed mean gap, 1/(∆min + ɛ)². This panel highlights the efficiency gains of PSɛBAI+ compared to the other methods, especially given its lack of access to contextual information.

In-depth insights#

PSLB Model#

The Piecewise Stationary Linear Bandit (PSLB) model presents a novel approach to the multi-armed bandit problem by incorporating contextual information and non-stationarity. Unlike traditional stationary bandit settings, the PSLB model acknowledges that the environment’s reward structure can change over time, reflecting real-world scenarios such as market fluctuations or changing weather patterns. Contextual information, in the form of latent vectors, is introduced to better capture the relationship between the arms and their rewards, thereby providing a more nuanced representation of the environment than simple reward values. The model elegantly combines these elements by defining the expected return of an arm as the average reward across all contexts, sampled according to an unknown probability distribution at each changepoint. This framework enables a more accurate and robust algorithm to identify an optimal arm, offering a significant advance over existing methods which assume stationary or non-contextual rewards. The model’s key strength is its capacity to handle complex, dynamic situations while still allowing for theoretical analysis and performance guarantees, establishing a foundation for future research in the field.

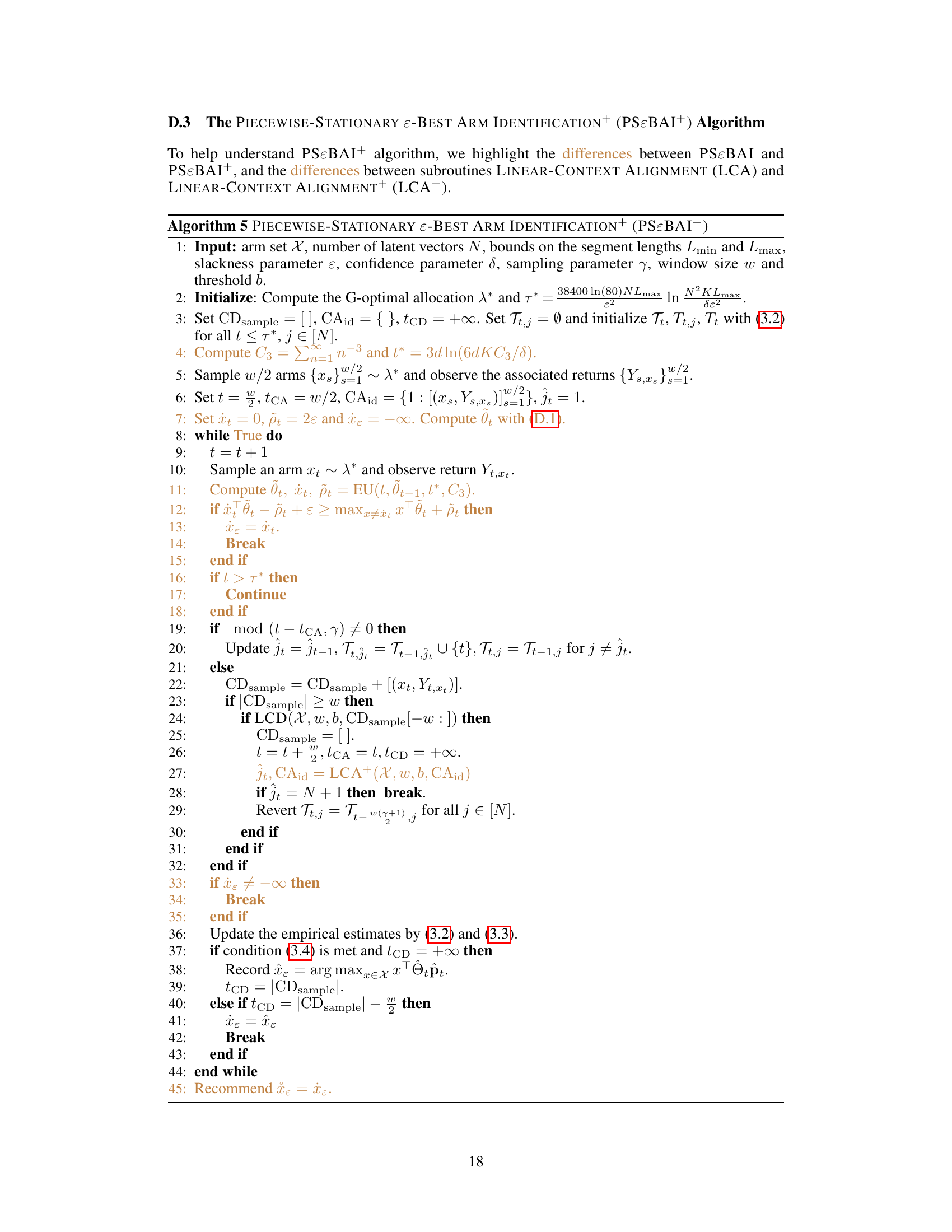

PSɛBAI+#

The algorithm ‘PSɛBAI+’ stands out as a novel solution for best arm identification in piecewise stationary linear bandits. It cleverly combines two subroutines, PSɛBAI and NɛBAI, running them in parallel. PSɛBAI actively detects changepoints and aligns contexts, improving efficiency, while NɛBAI serves as a baseline. This parallel execution is key to achieving a finite expected sample complexity, a significant improvement over algorithms that only use a naive approach. The theoretical analysis demonstrates near-optimal sample complexity up to a logarithmic factor, highlighting the algorithm’s efficiency. Empirical experiments further validate the theoretical findings, showcasing its efficiency and robustness to various parameter settings. The success of PSɛBAI+ strongly depends on the change detection and context alignment procedures integrated within PSɛBAI, which are crucial for its superior performance in non-stationary environments.

Lower Bound#

The Lower Bound section of a research paper is crucial for establishing the theoretical limits of a problem. It provides a benchmark against which the performance of proposed algorithms can be measured. A tight lower bound demonstrates that an algorithm’s performance is close to optimal, while a loose lower bound leaves room for potential improvement. In the context of best arm identification in piecewise stationary linear bandits, the lower bound would likely involve deriving a fundamental limit on the minimum number of samples needed to identify an ɛ-optimal arm with high probability. This lower bound would likely be a function of problem parameters such as the number of arms, the dimensionality of the contexts, the minimum and maximum lengths of stationary segments, the desired accuracy (ɛ), and the acceptable failure probability (δ). The derivation of such a bound could involve information theoretic techniques or other advanced mathematical tools, perhaps focusing on worst-case scenarios or constructing difficult instances to solve. The analysis is very important since it validates the optimality of proposed algorithms in the paper. If the proposed algorithm’s sample complexity matches the lower bound (up to logarithmic factors), then it’s proven to be near-optimal, a significant theoretical contribution.

Experiment#

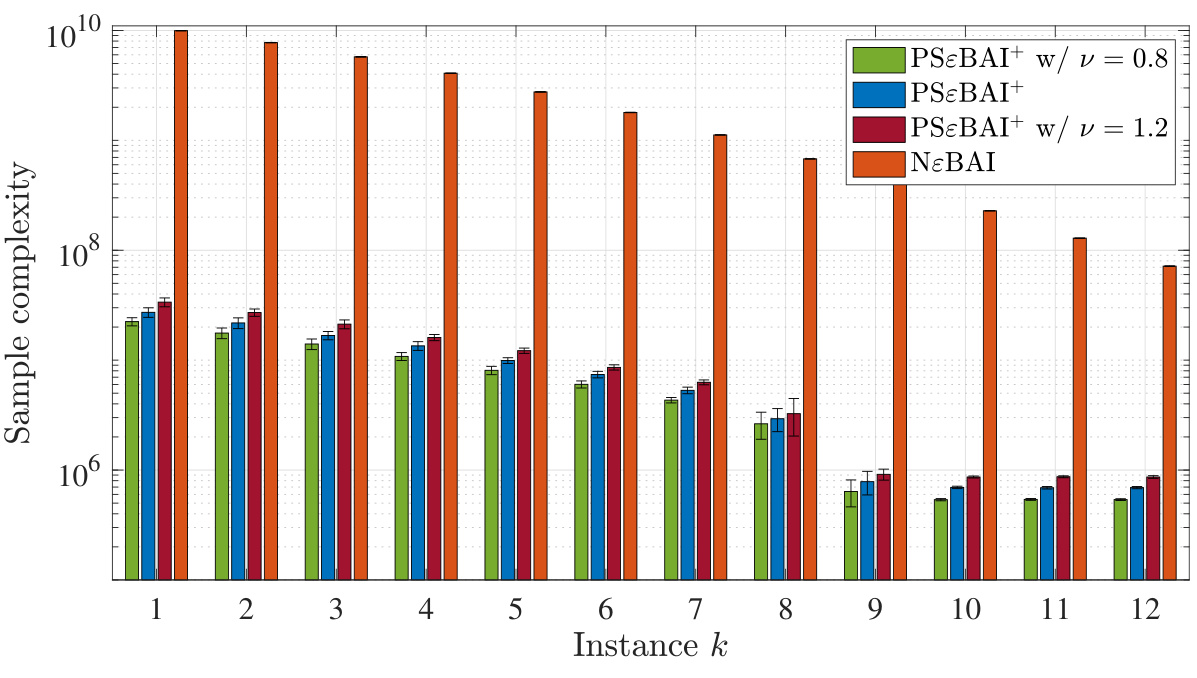

The ‘Experiment’ section of a research paper is crucial for validating the claims made. A well-designed experiment should rigorously test the core hypotheses, using appropriate methodologies and controls. The methodology should be clearly described, allowing for reproducibility. Statistical significance is paramount; error bars, confidence intervals, or p-values should be reported to demonstrate the reliability of the findings. Furthermore, the experimental setup must align with the theoretical framework presented earlier, avoiding a disconnect between theory and practice. Careful consideration of confounding variables and biases is essential to ensure that the observed effects are indeed due to the manipulated variables and not some other factor. The ‘Experiment’ section must also establish the generalizability of findings by choosing a representative dataset and appropriately justifying its limitations, which are then thoroughly discussed.

Future Work#

The “Future Work” section of this research paper presents exciting avenues for extending the piecewise stationary linear bandits (PSLB) model and the PSɛBAI+ algorithm. Addressing the limitations of requiring knowledge of Lmin and Lmax is crucial. The authors suggest investigating methods to relax or remove these assumptions, potentially through clustering contexts or employing more sophisticated changepoint detection techniques. Developing instance-dependent optimal algorithms is another key area, potentially by exploring adaptive sampling strategies beyond the G-optimal allocation used in PSɛBAI+. Furthermore, the authors rightly point out the need to adapt the algorithm to the fixed-budget setting for more practical applicability. Finally, extending the PSLB model to handle more complex scenarios, such as those with non-stationary contexts or more intricate reward structures, represents a significant challenge and a promising opportunity for future research. The work on improving context alignment and change detection could yield significant advancements in online learning problems involving non-stationary data.

More visual insights#

More on figures

Figure 2(a) shows the sample complexity of PSɛBAI+ and NɛBAI for different instances, demonstrating that PSɛBAI+ significantly outperforms NɛBAI. Figure 2(b) compares the number of context samples required by PSɛBAI+, NɛBAI, DɛBAI, and DɛBAIß for best arm identification, showcasing that PSɛBAI+, despite not having access to contextual information and changepoints, performs competitively with DɛBAI and DɛBAIß which do have access to this information. The x-axis represents the squared relaxed mean gap, indicating that the algorithm’s sample complexity is inversely proportional to the squared relaxed mean gap.

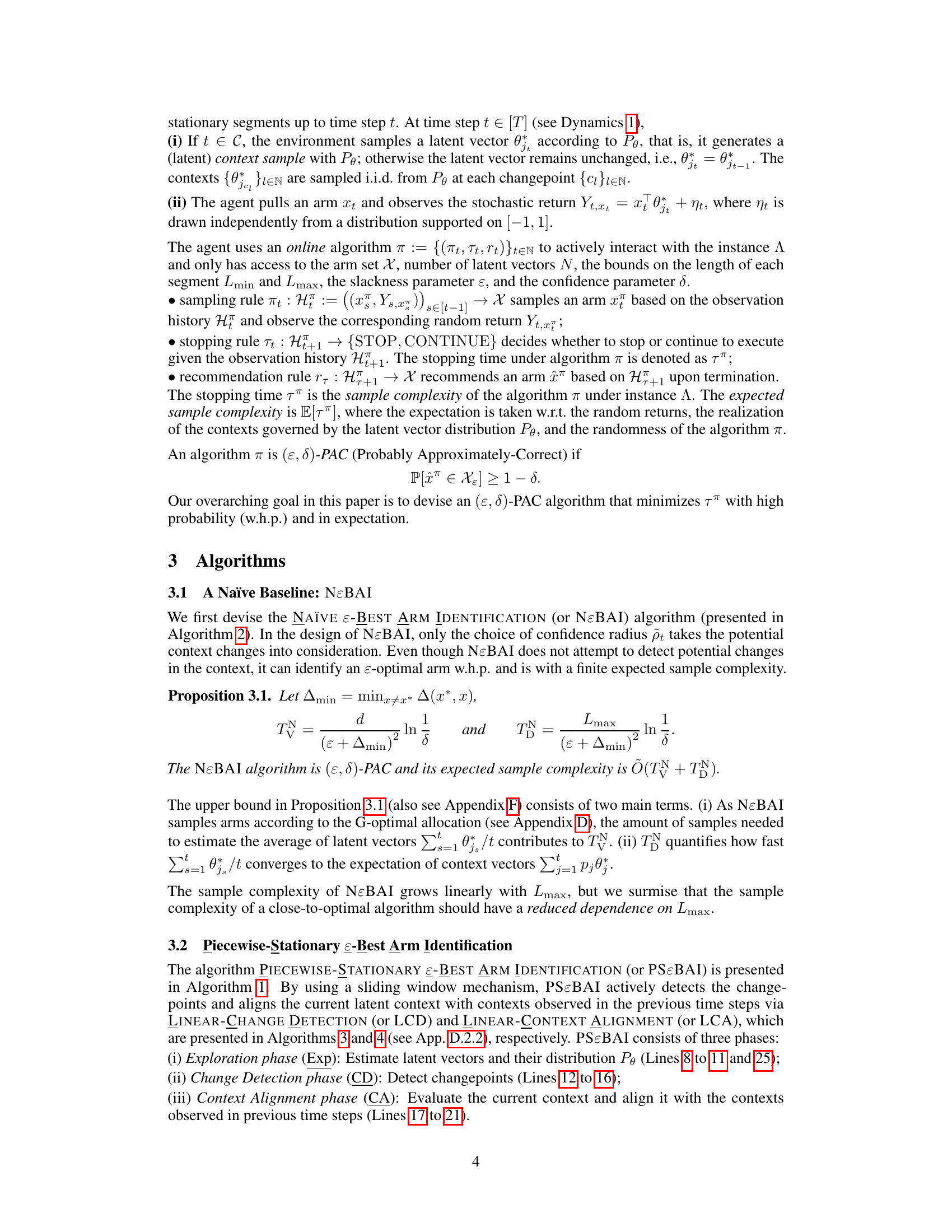

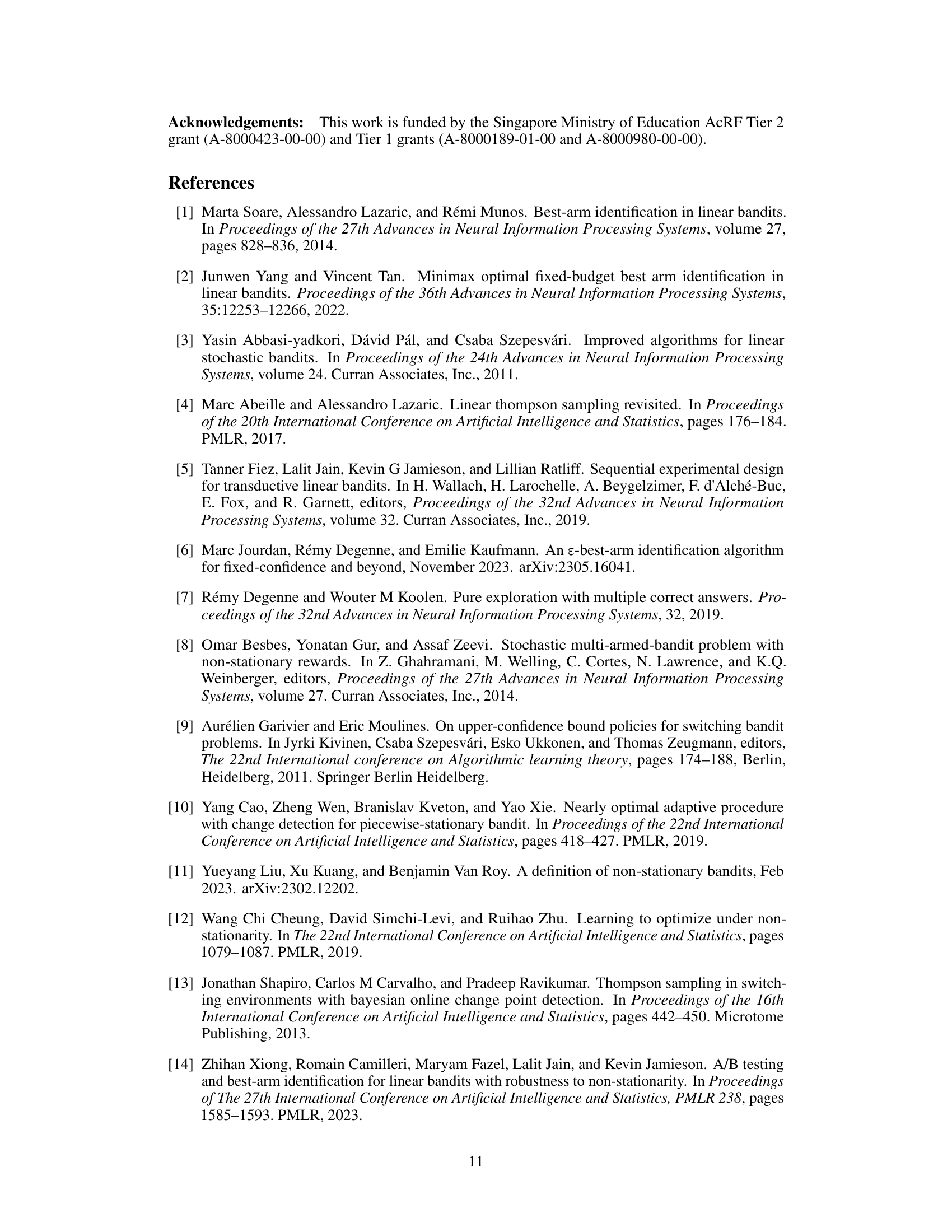

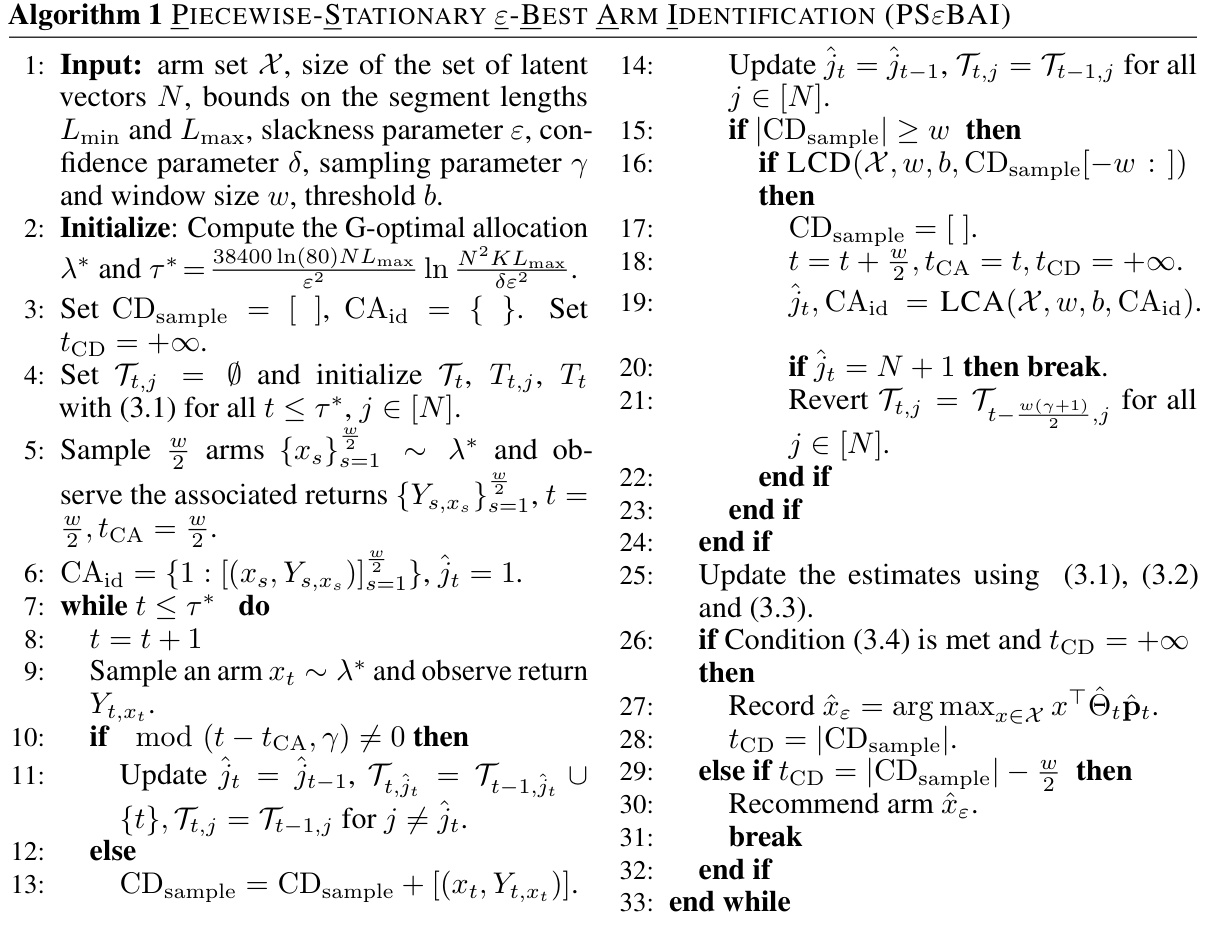

The figure shows the empirical sample complexities of PSɛBAI+ with misspecified parameters Lmin and Lmax, compared to the sample complexity of the NɛBAI algorithm. The results demonstrate that PSɛBAI+ maintains its efficiency and outperforms NɛBAI even when the true values of Lmin and Lmax are not perfectly known. This highlights the robustness of PSɛBAI+ to misspecifications in these parameters.

This figure illustrates the two different scenarios in PSɛBAI algorithm. (a) shows a stationary segment where no change point is detected. The active CD samples are used in LCD subroutine. (b) shows that a change point is detected by the LCD subroutine. This is followed by the CA subroutine and a reversion step. The reversion step reverts all the collected data back to the most recent ones before the change point.

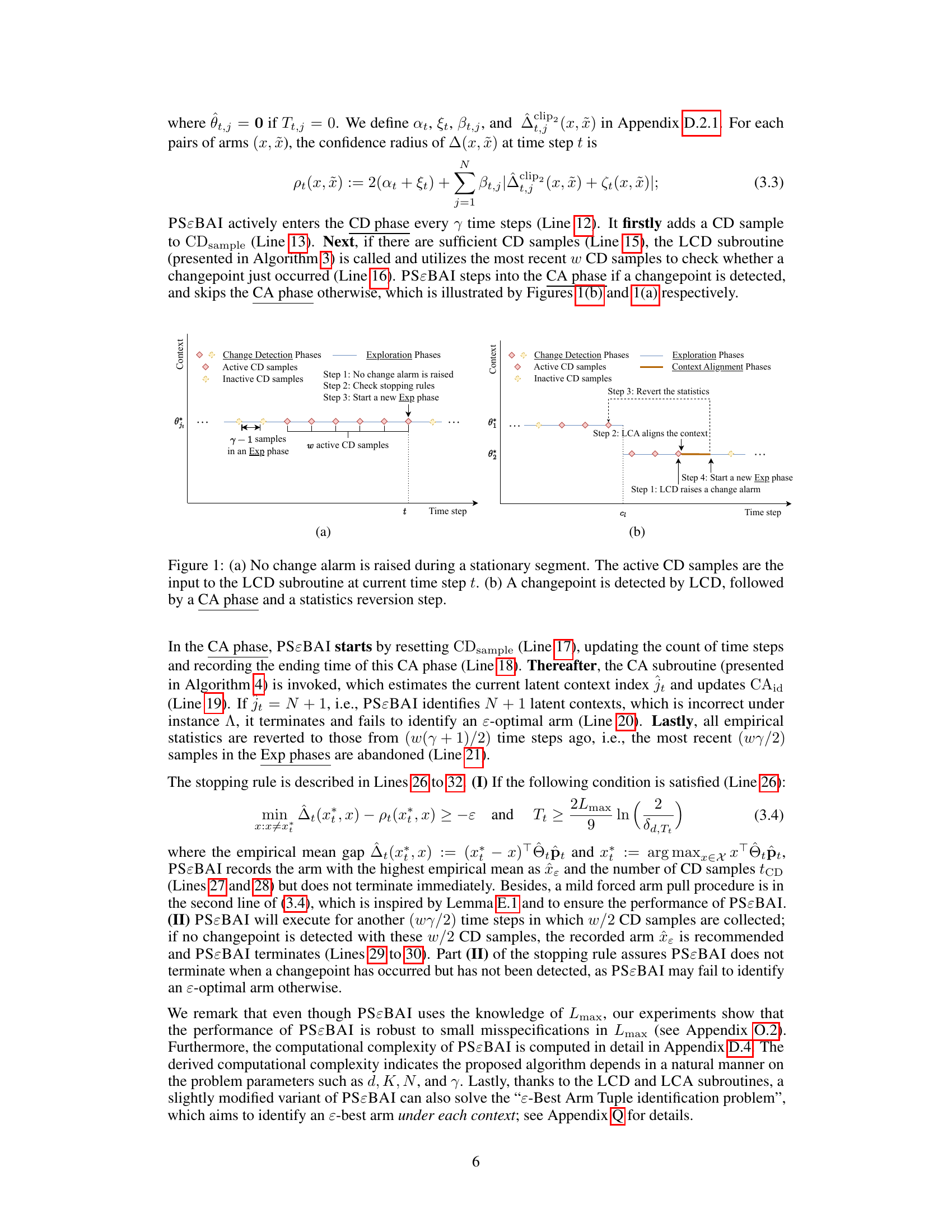

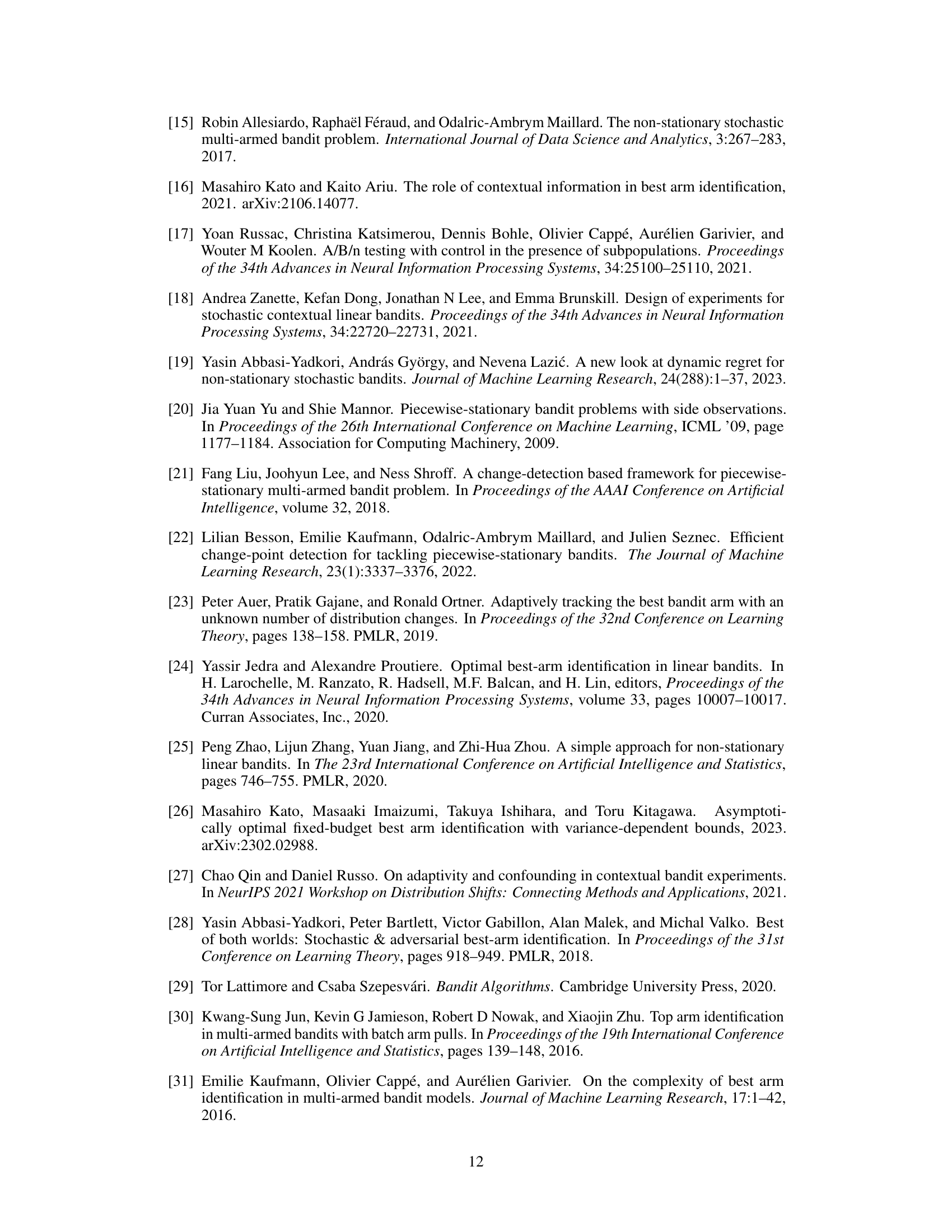

The figure shows the empirical sample complexities of PSɛBAI+ with different choices of window size w and threshold b, which are controlled by the change detection frequency γ. The results indicate that PSɛBAI+ is robust to the choices of w and b, as long as Assumption 1 is not severely violated. PSɛBAI+ consistently outperforms the naive algorithm NɛBAI in all cases.

More on tables

Figure 2 presents experimental results comparing the sample complexity of PSɛBAI+ and NɛBAI algorithms. The left subplot (a) shows the sample complexity of both algorithms across various instances, highlighting the significantly lower complexity of PSɛBAI+. The right subplot (b) illustrates the number of context samples required for best arm identification (BAI), demonstrating that PSɛBAI+ achieves this with fewer samples compared to the baselines.

Figure 2 presents a comparison of the sample complexity and the number of context samples required for best arm identification using two different algorithms, PSɛBAI+ and NɛBAI. Subfigure (a) shows a bar chart illustrating the sample complexity of both algorithms across different problem instances, highlighting the significant efficiency gains achieved by PSɛBAI+. Subfigure (b) displays a line chart showing the number of context samples needed for best arm identification by PSɛBAI+, NɛBAI, DɛBAI, and DɛBAIß, demonstrating the competitiveness of PSɛBAI+ even when contextual information is not readily available.

Full paper#