↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Training robots to perform diverse tasks is hampered by the scarcity of labeled robotic data. This paper introduces a novel approach, focusing on utilizing readily available human videos to overcome this limitation. Existing methods struggle with transferring knowledge from human videos to robots due to domain differences and noisy human data.

The proposed framework, termed VPDD, uses a unified discrete diffusion model to handle both human and robot videos. It first pre-trains the model on human videos to learn general dynamic patterns, and then fine-tunes it on a small set of robot videos for action learning, using predicted future videos as guidance. Experiments demonstrate that this method successfully predicts future videos and improves robotic action performance compared to existing state-of-the-art techniques. The model achieves high fidelity video prediction and superior performance on multi-task robotic problems, even for unseen scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses the critical challenge of training embodied AI agents with limited robot data. By leveraging large-scale actionless human videos for pre-training, it unlocks a new avenue for efficient and effective AI agent learning. Its success in multi-task robotic problems, especially with seen and unseen scenarios, has significant implications for the field.

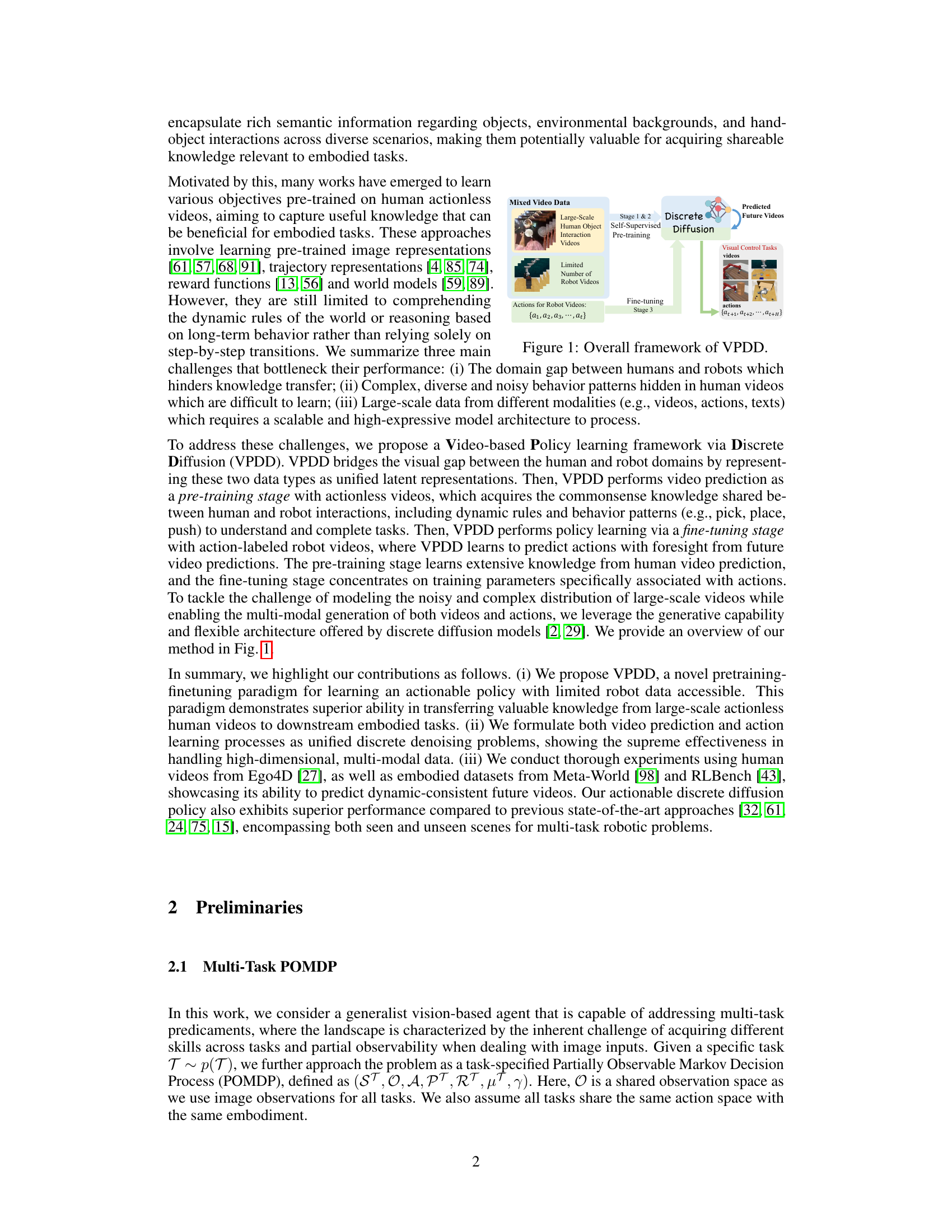

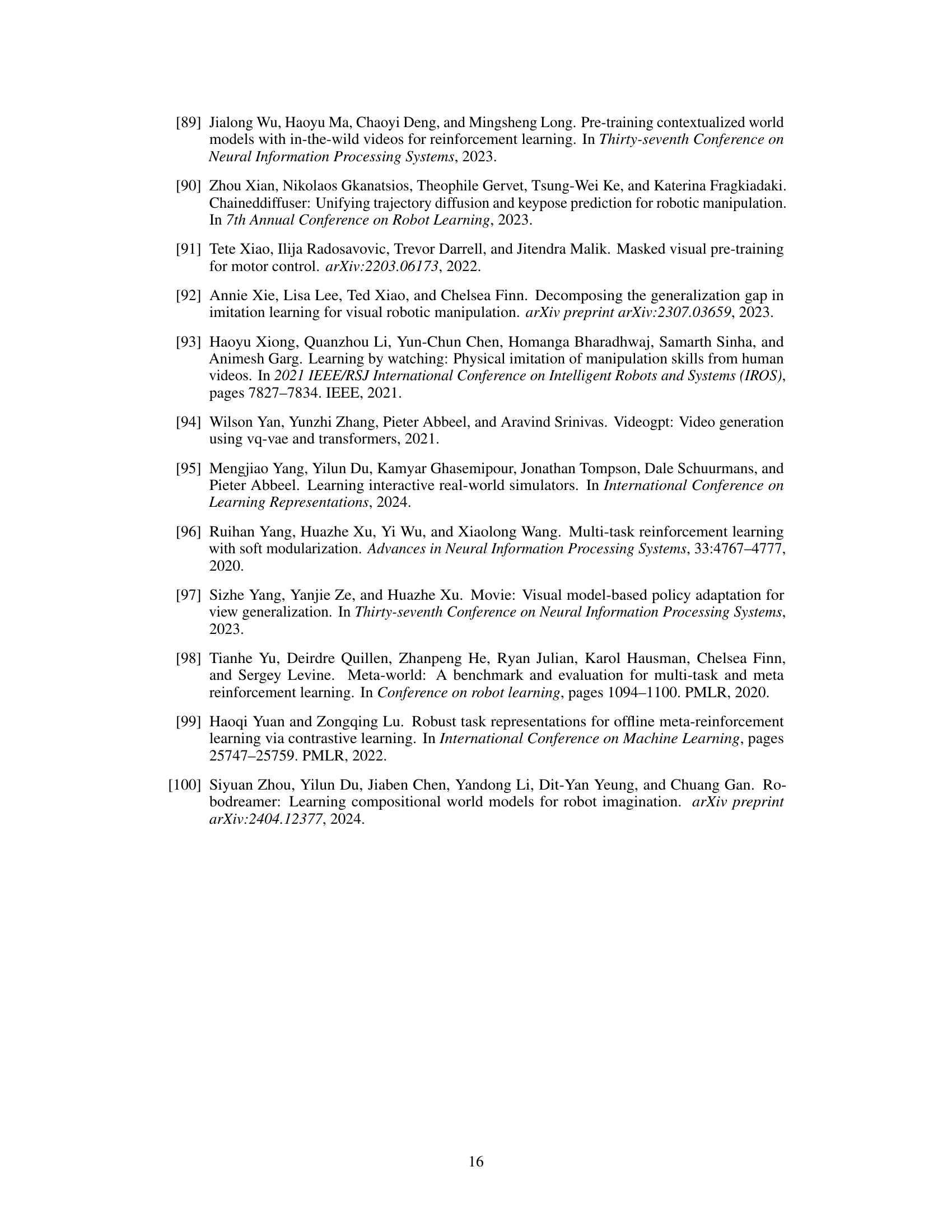

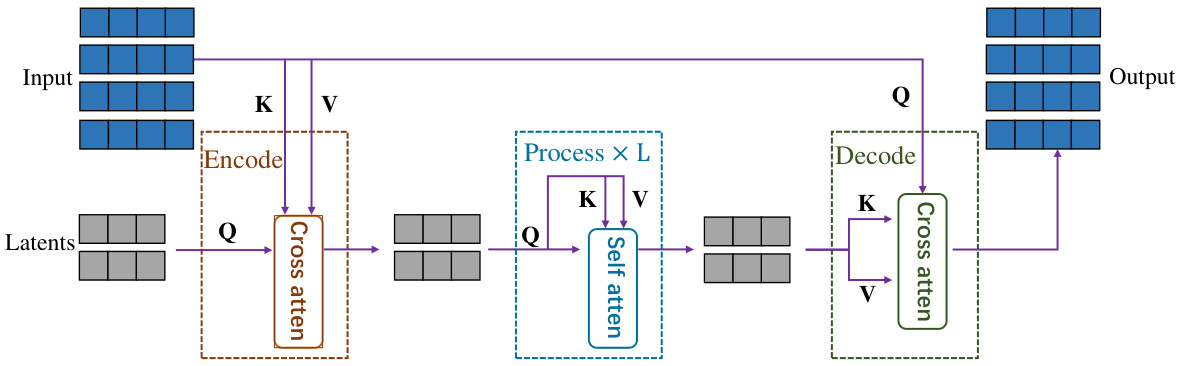

Visual Insights#

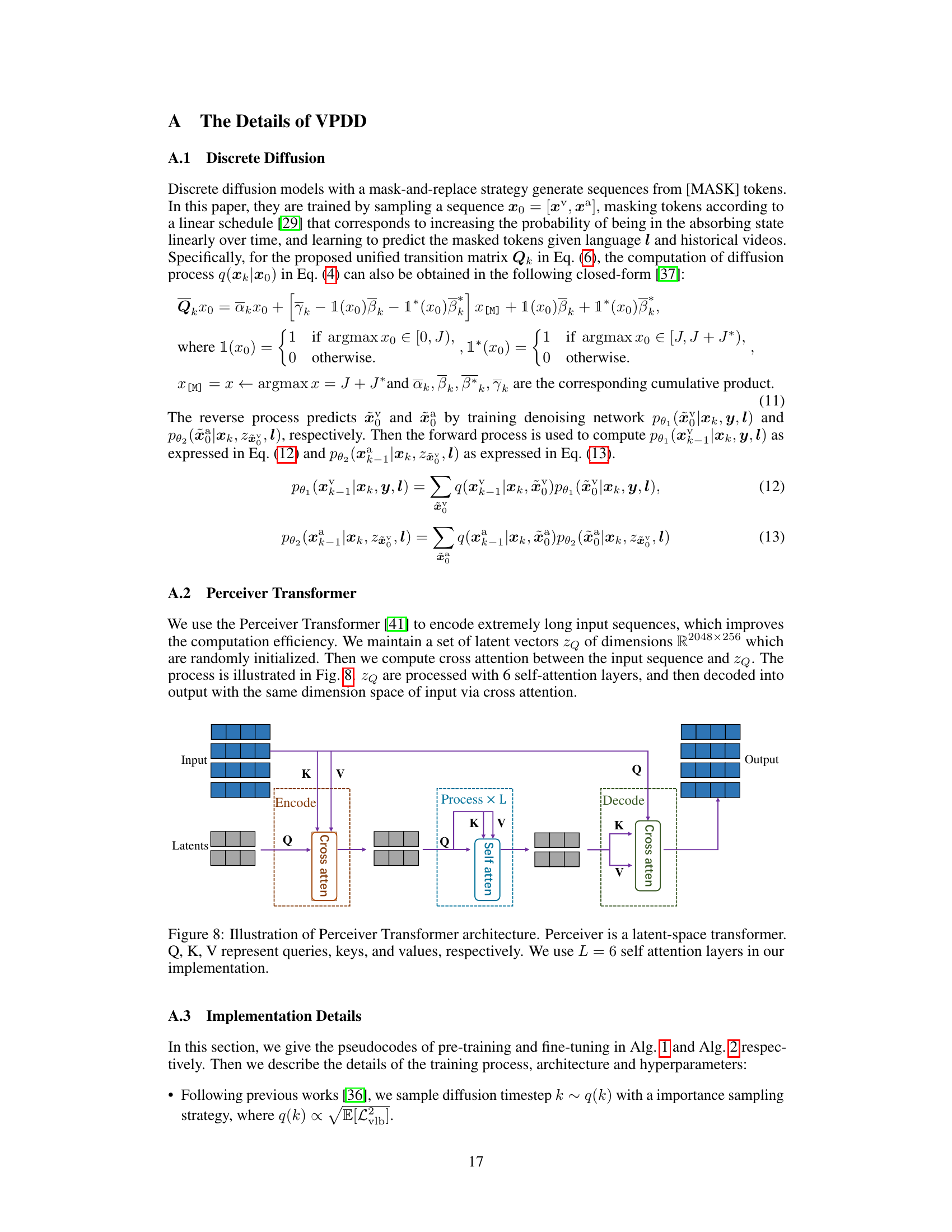

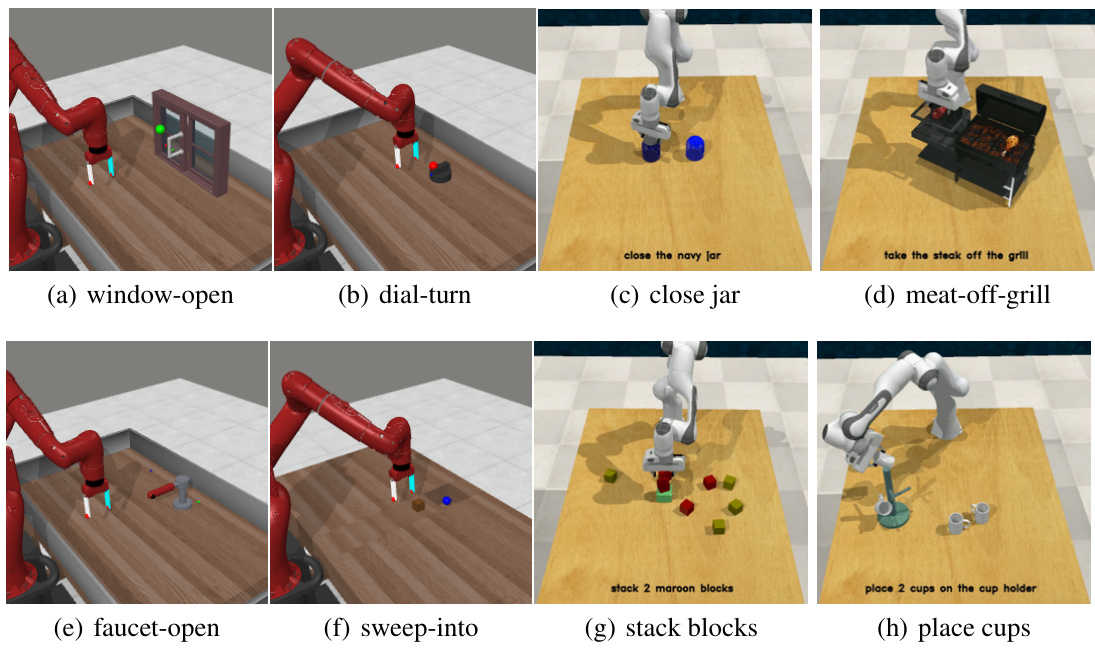

The figure illustrates the overall framework of the Video-based Policy learning framework via Discrete Diffusion (VPDD). It shows how the model leverages large-scale actionless human videos and a small number of action-labeled robot videos to learn an actionable discrete diffusion policy. The process involves three stages: 1) Mixed video data (human and robot videos) undergoes a Vector Quantized Variational Autoencoder to create unified latent representations. 2) Self-supervised pre-training using a discrete diffusion model predicts future videos and actions, learning shared knowledge between humans and robots. 3) Fine-tuning on limited robot data guides low-level action learning using predicted future videos to enhance the learned policies.

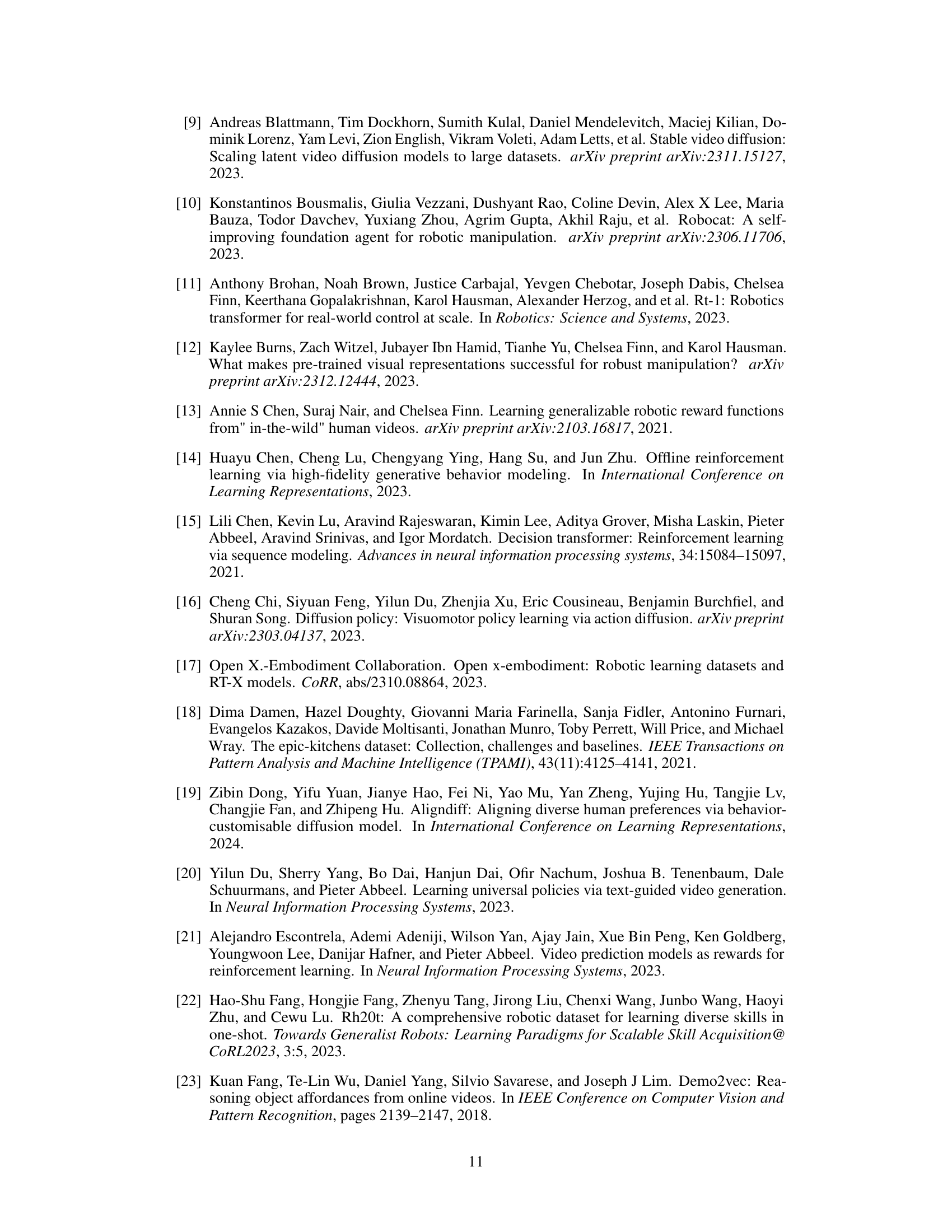

This table presents the success rates of different multi-task agents on RLBench, a challenging robotic manipulation benchmark. The agents were trained using only 10 demonstrations per task. VPDD (ours) significantly outperforms the state-of-the-art methods (PERACT and RVT) by an average factor of 1.24. It’s noteworthy that VPDD only uses RGB images as input, while the other methods also utilize depth images, highlighting its efficiency.

In-depth insights#

Actionless Video Pre-train#

Actionless video pre-training leverages the abundance of readily available human videos, without action labels, to learn generalizable visual representations. This approach addresses the scarcity of labeled robotic datasets, a major bottleneck in embodied AI. By pre-training on diverse actionless videos, the model learns rich semantic information about objects, interactions, and scenes. This pre-trained knowledge is then transferred to a robot policy through fine-tuning on a small dataset of action-labeled robot videos. The key benefit is reducing the need for extensive robot data collection, a costly and time-consuming process. The approach bridges the domain gap between human videos and robot actions, enabling the robot to generalize to unseen situations and perform novel tasks. A key challenge lies in effectively extracting useful information from noisy, multimodal, unlabeled human video data. Successful methods will often involve feature extraction techniques and self-supervised learning objectives that capture dynamic visual patterns for better knowledge transfer and robust performance.

Unified Diffusion#

A unified diffusion model, in the context of a research paper, likely refers to a novel approach that integrates multiple modalities or datasets into a single diffusion framework. This contrasts with using separate diffusion models for different data types. The key advantage is the potential for improved knowledge transfer and representation learning. By processing diverse data sources within a unified framework, the model can potentially capture richer contextual information and relationships between modalities. This could involve integrating video data from both humans and robots, facilitating knowledge transfer between these two domains. A unified approach can also address the domain gap issue, a common problem when training robot policies using human demonstration videos, which often have different characteristics (e.g., noisy, multimodal data). The success of a unified model depends on effective feature extraction and alignment across different sources. Challenges could involve designing a suitable architecture to effectively handle and integrate data from disparate sources and then finding the optimal training procedure to leverage the information effectively. The results would be evaluated on downstream tasks, demonstrating the unified model’s effectiveness in improving performance in a multitasking robotic scenario.

Multi-Task POMDP#

The heading ‘Multi-Task POMDP’ suggests a framework for tackling complex robotics problems involving multiple tasks within a Partially Observable Markov Decision Process environment. A POMDP inherently deals with uncertainty—the agent doesn’t have complete information about the environment’s state. The ‘Multi-Task’ aspect implies the agent must learn to solve diverse tasks, potentially requiring different skills and strategies. This presents a significant challenge because policies must be robust enough to handle the inherent variability and uncertainty of a multi-task setting, while also being efficient in resource utilization. A key aspect to consider would be how the agent efficiently transfers knowledge between tasks, avoiding catastrophic forgetting and improving generalization. This could involve techniques such as modular policies, shared representations between tasks, or meta-learning approaches. The overall effectiveness of such a framework hinges on the representation of the environment, the planning algorithm’s efficiency, and the ability to effectively learn from limited data.

Few-Shot Fine-tune#

The concept of “Few-Shot Fine-tune” in the context of a research paper likely revolves around adapting a pre-trained model to new tasks with minimal data. This approach is crucial for scenarios where acquiring large labeled datasets is expensive or impractical. The core idea is to leverage the knowledge encoded in a large-scale pre-trained model, making it adaptable to new, similar tasks using only a few examples. This would involve a fine-tuning process focusing on adjusting the pre-trained weights rather than training from scratch. The effectiveness of this approach hinges on the quality of the pre-training and the similarity between the pre-training and fine-tuning data. A successful few-shot fine-tune method would demonstrate a significant reduction in the data needed for effective model adaptation, while maintaining accuracy comparable to models trained on substantially larger datasets. Key considerations would be the choice of pre-training data, the fine-tuning methodology (e.g., transfer learning techniques), and the evaluation metrics used to assess the model’s performance on the new tasks.

Generalization Limits#

A section titled ‘Generalization Limits’ in a research paper would critically examine the boundaries of a model’s ability to perform well on unseen data or tasks. It would likely explore factors hindering generalization, such as dataset bias, where the training data doesn’t accurately reflect the real-world distribution. The discussion would also likely delve into the impact of model architecture, considering whether its complexity or design choices limit its capacity to adapt to novel situations. Domain adaptation challenges would be a key focus, investigating the difficulties of transferring knowledge learned in one context (e.g., simulation) to another (e.g., real-world robotics). Furthermore, the analysis might address sample efficiency, examining whether the model needs excessive data to achieve satisfactory generalization, or its reliance on specific data features (overfitting). Finally, the section could conclude by suggesting potential solutions or directions for future research to overcome these limitations, improving robustness and generalization performance.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the overall framework of the Video-based Policy learning framework via Discrete Diffusion (VPDD) model. It shows three stages: 1) Video Tokenization using VQ-VAE to encode human and robot videos into a unified latent space; 2) Pre-training with mixed data using a discrete diffusion model to predict future videos based on historical videos and language instructions; and 3) Fine-tuning with robot data to learn an actionable policy by using the predicted future videos to guide action learning.

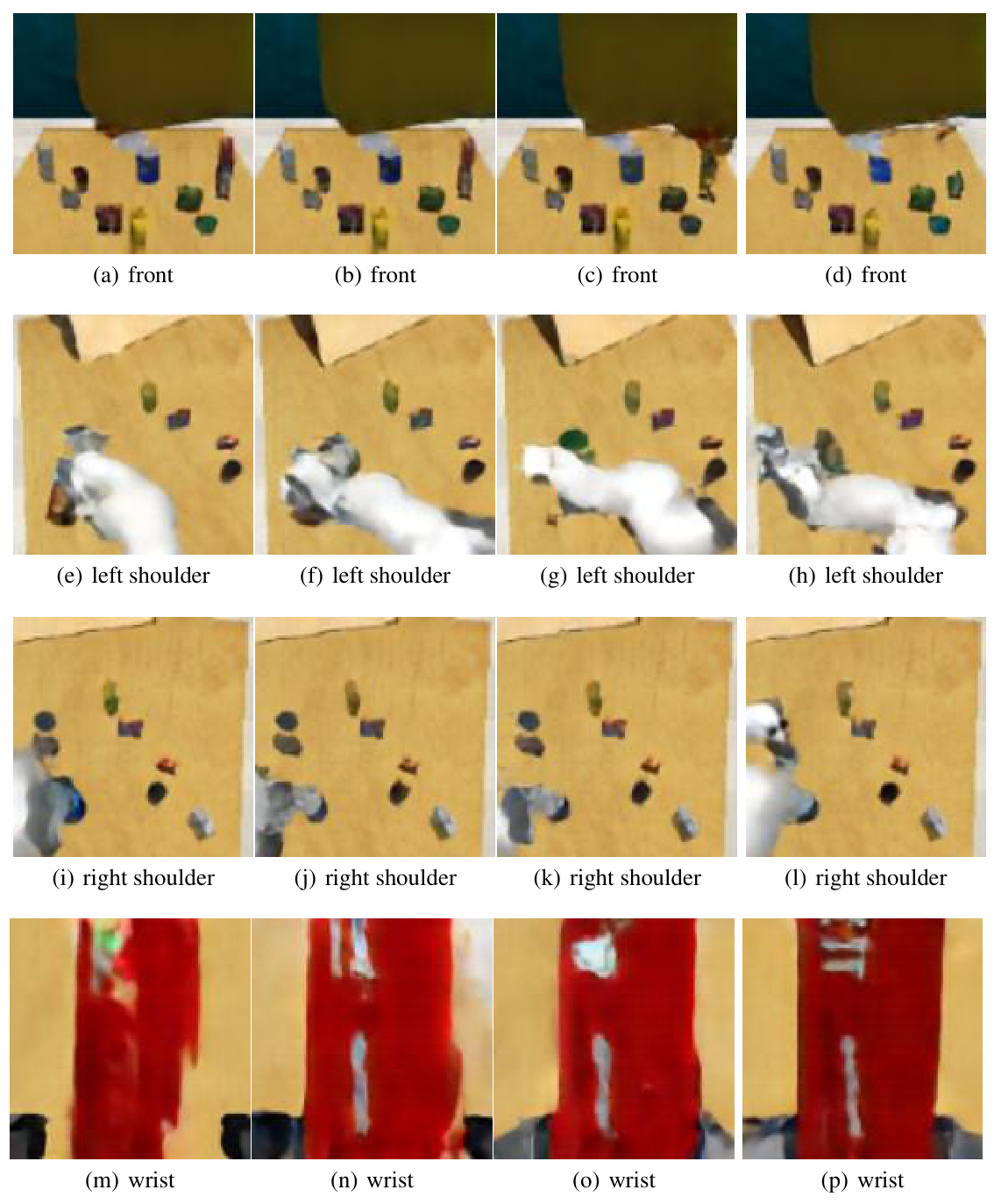

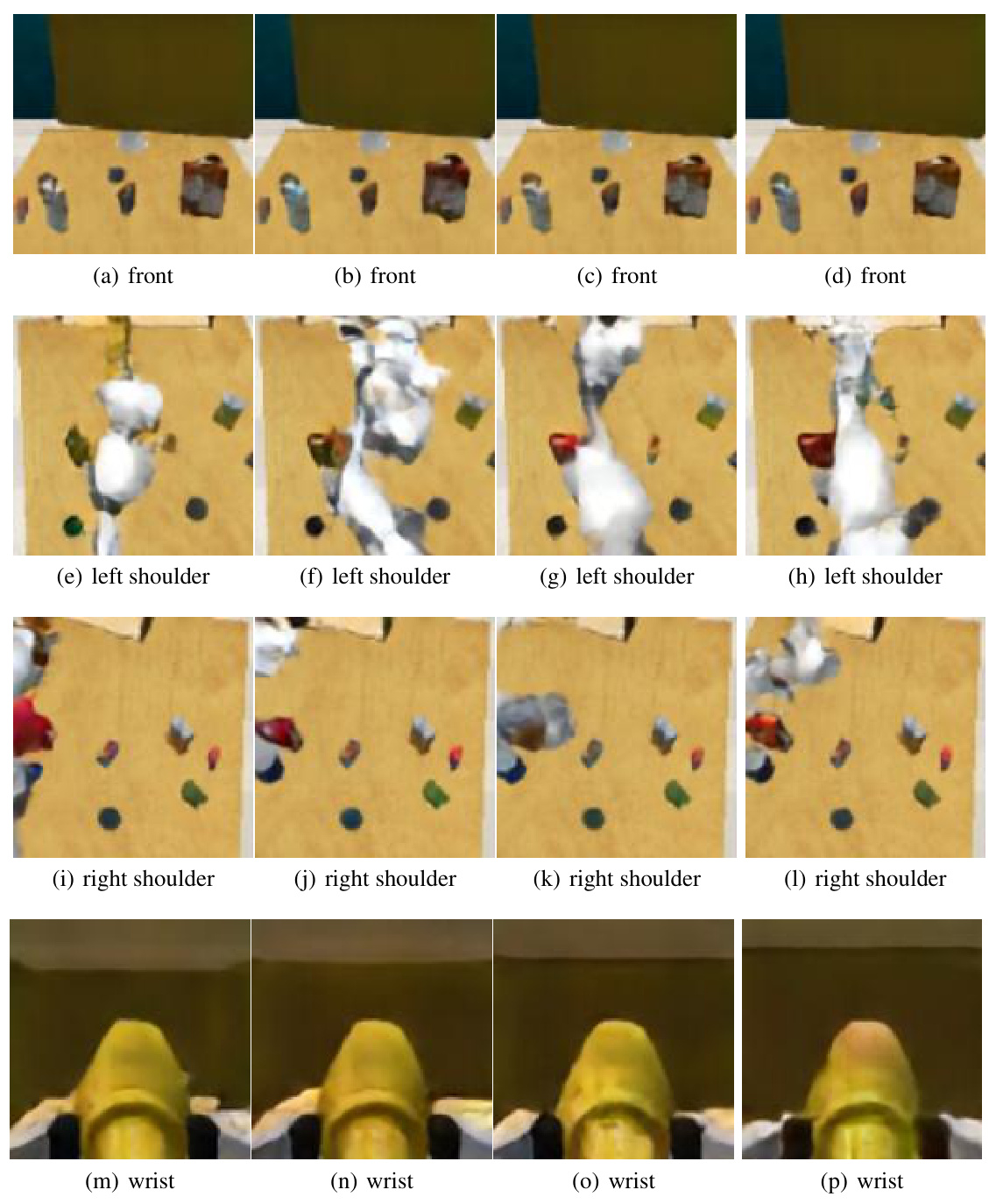

This figure shows sample images from videos generated by the model’s video prediction component (pθ1). It demonstrates the model’s ability to generate both single-view (Meta-World button-press) and multi-view (RLBench drug-stick) images that capture the temporal dynamics of the tasks. This is crucial for the model’s downstream action prediction capabilities. The images are taken from different viewpoints, including front and various shoulder and wrist camera angles for the RLBench task. These illustrate the model’s capacity to learn general dynamic patterns for planning and control.

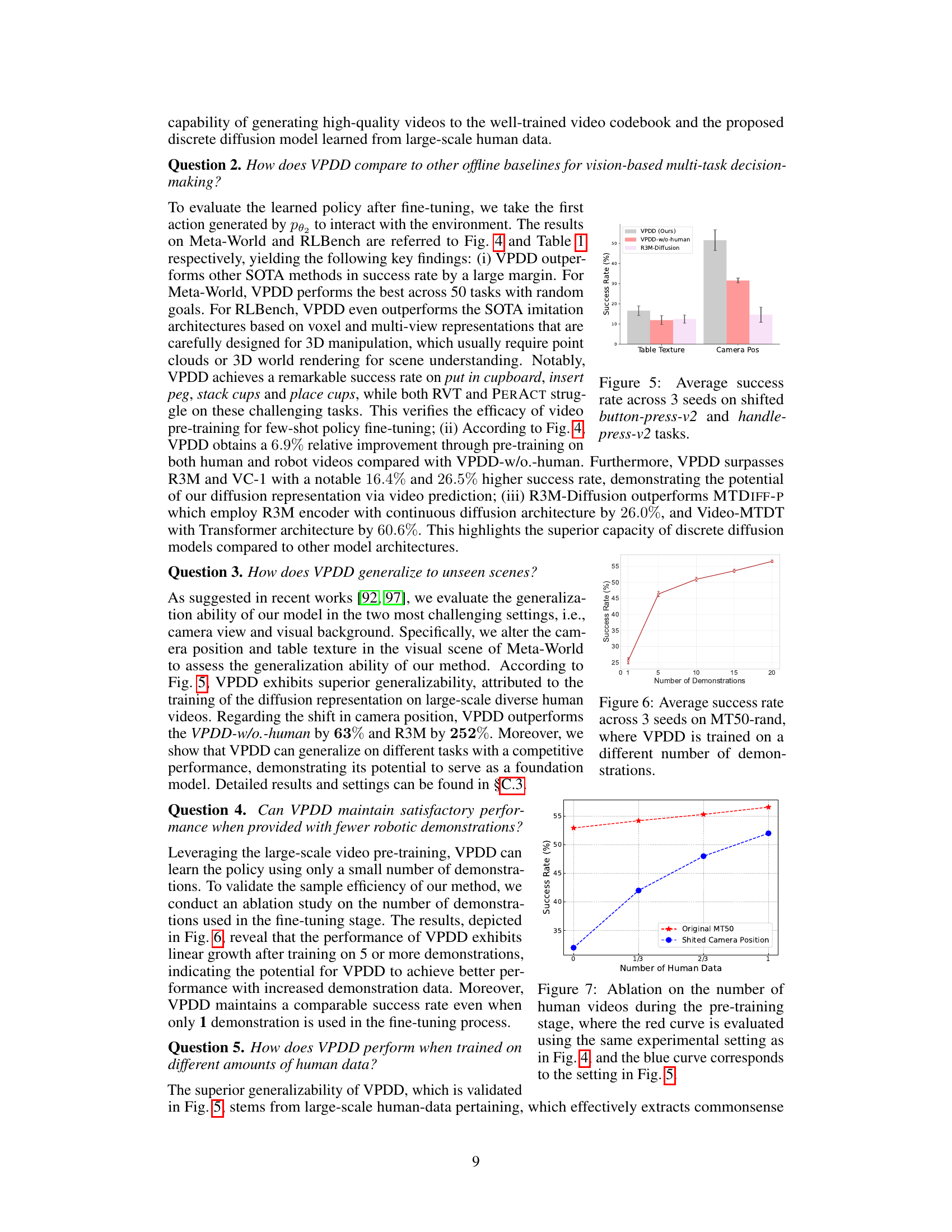

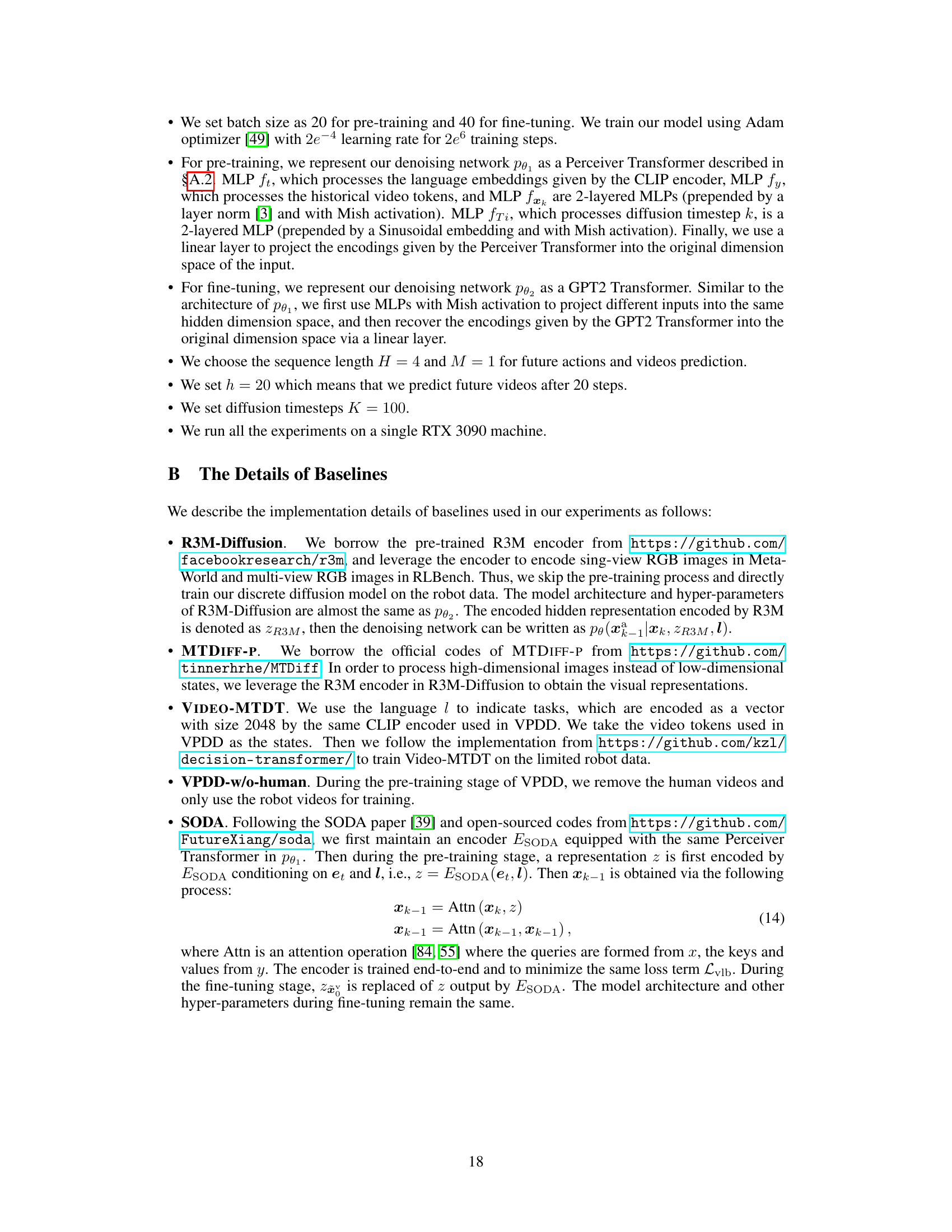

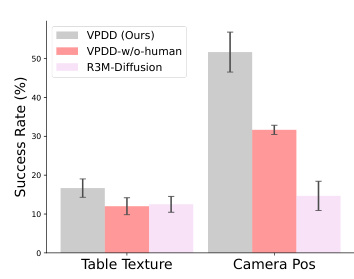

This figure shows the average success rate across three different random seeds for 50 distinct manipulation tasks in the Meta-World benchmark (MT50-rand). Each task was evaluated using 50 episodes. The performance of VPDD (ours), VPDD without human data, MTDIFF-P, R3M-Diffusion, VC-1-Diffusion, Video-MTDT, and SODA are compared to highlight the effectiveness of VPDD’s approach.

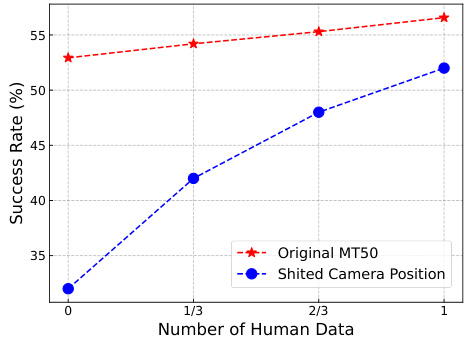

This figure presents a bar chart comparing the average success rates of different methods on the MT50-rand benchmark of Meta-World. The success rate, expressed as a percentage, represents the proportion of times each method successfully completed a task. The chart showcases the performance of VPDD (Ours), VPDD without human data, R3M-Diffusion, VC-1-Diffusion, and Video-MTDT across multiple tasks. Error bars indicate the standard deviation across three independent runs. The figure demonstrates VPDD’s superior performance compared to the baselines on Meta-World tasks.

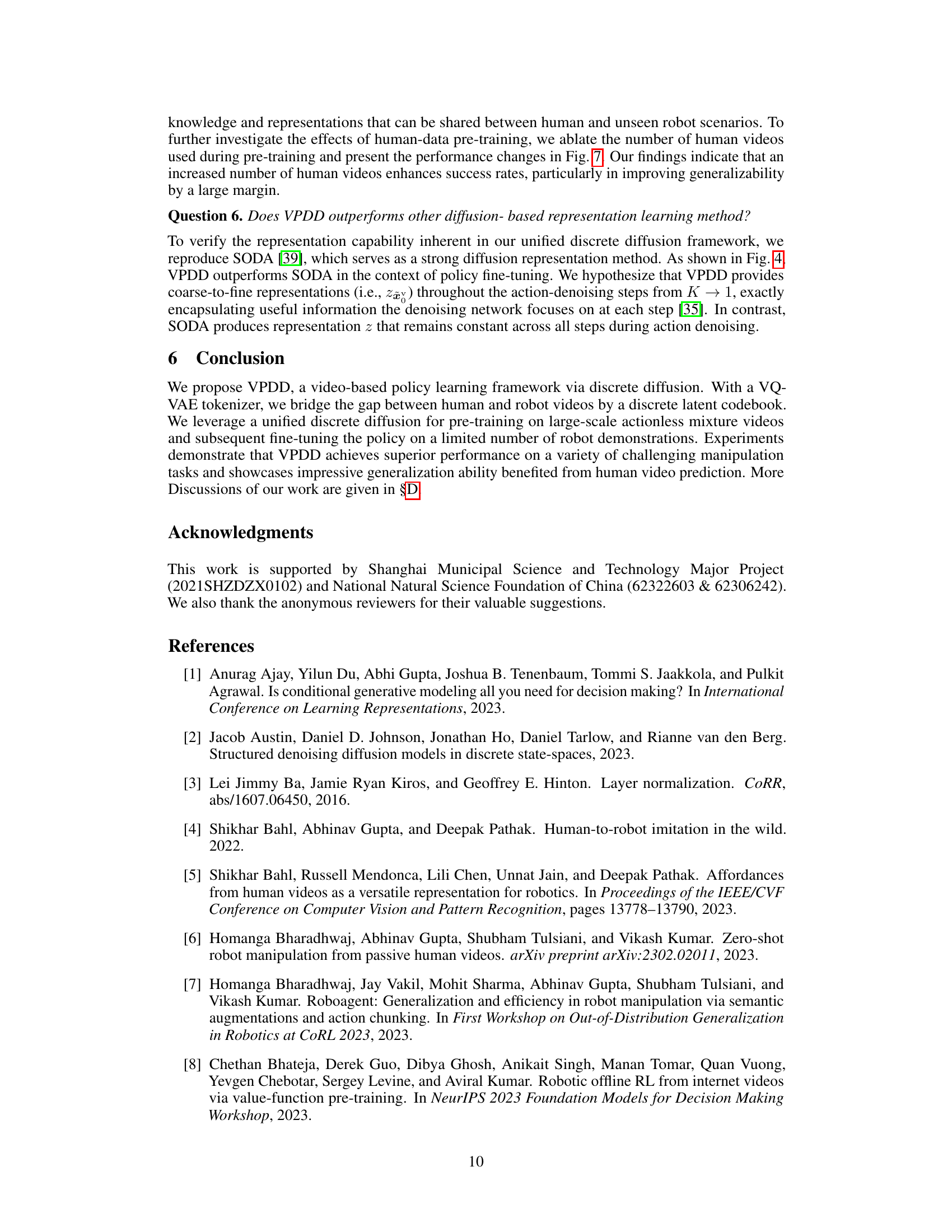

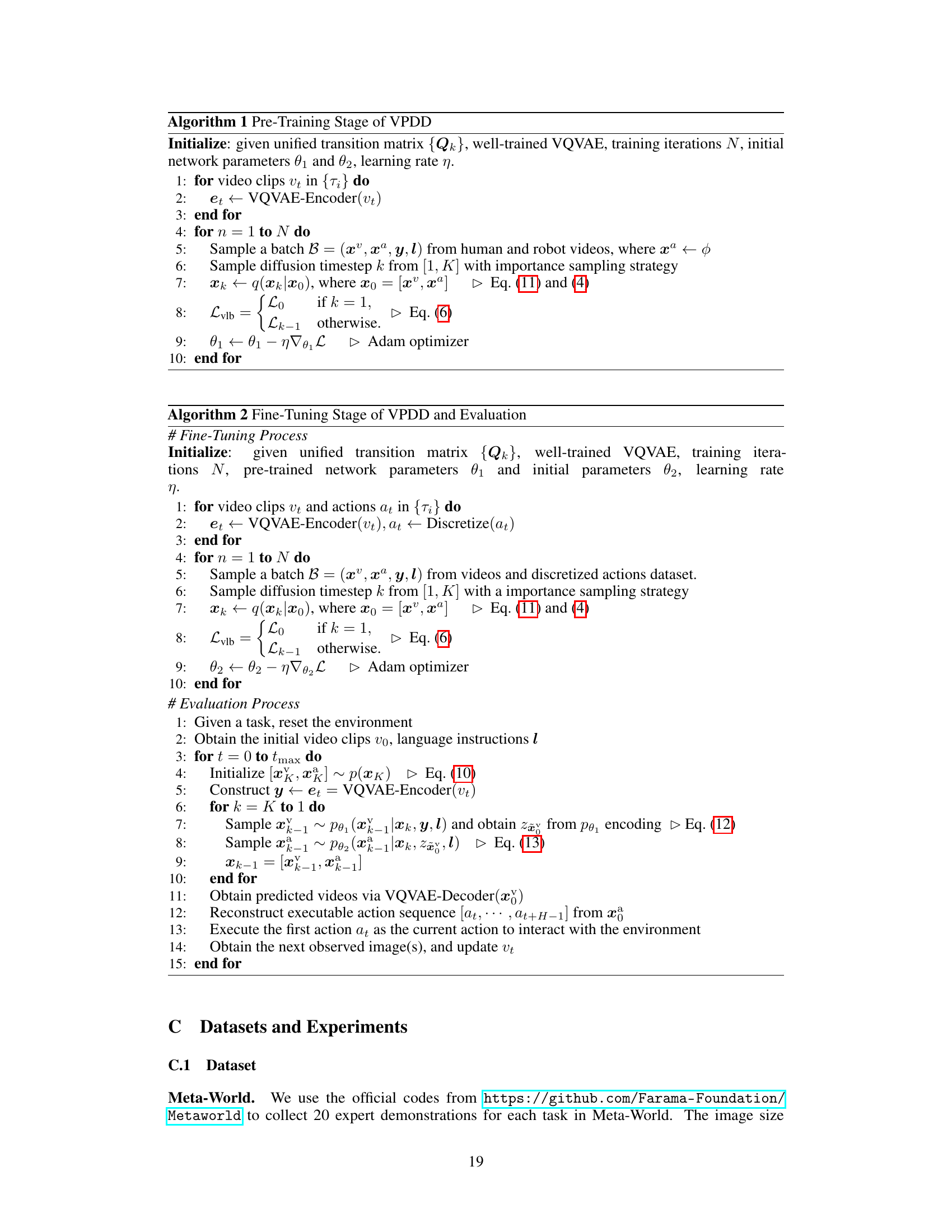

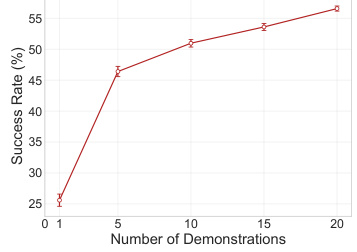

This figure shows the ablation study on the number of demonstrations used in the fine-tuning stage. The results indicate that the performance of VPDD exhibits linear growth after training on 5 or more demonstrations, suggesting good sample efficiency. Even with only 1 demonstration, VPDD maintains a comparable success rate, highlighting its ability to learn effectively from limited data due to the strong pre-training.

This figure shows the average success rate across three different random seeds for 50 distinct manipulation tasks in the Meta-World benchmark (MT50-rand). Each task was evaluated over 50 episodes. The figure compares the performance of the proposed method (VPDD) against several baseline approaches.

This figure shows the overall pipeline of the proposed Video-based Policy learning framework via Discrete Diffusion (VPDD). It illustrates the process of encoding human and robot videos using VQ-VAE, pre-training a unified discrete diffusion model for video prediction using a self-supervised objective, and fine-tuning the model for action learning using a limited set of robot data. The figure highlights the integration of video prediction and action learning through the unified discrete diffusion model.

This figure illustrates the overall pipeline of the Video-based Policy learning framework via Discrete Diffusion (VPDD). It shows how human and robot videos are encoded into discrete latent codes using a VQ-VAE. The model is then pre-trained using a self-supervised approach to predict future videos, conditioned on language instructions and past video frames. Finally, it’s fine-tuned on robot data, using the pre-trained video prediction to guide action learning. The process combines generative video prediction and action prediction within a unified discrete diffusion framework.

This figure illustrates the overall framework of the Video-based Policy learning framework via Discrete Diffusion (VPDD). It shows the three main stages: video tokenization using a VQ-VAE, pre-training with mixed human and robot data using a discrete diffusion model to predict future videos, and fine-tuning with limited robot data to learn an actionable policy by leveraging video foresight.

This figure illustrates the overall framework of the Video-based Policy learning framework via Discrete Diffusion (VPDD). It shows how human and robot videos are encoded into discrete latent codes using a VQ-VAE. The framework then uses a unified discrete diffusion model for pre-training (predicting future videos using language instructions and historical videos) and fine-tuning (predicting actions from future video predictions using limited robot data).

This figure illustrates the overall framework of the Video-based Policy learning framework via Discrete Diffusion (VPDD) model. It details the three stages: 1) Video Tokenizing using VQ-VAE to encode human and robot videos into a unified latent space; 2) Pre-training with mixed data using a discrete diffusion model for future video prediction, conditioned on language instructions and historical frames; 3) Fine-tuning with robot data, incorporating predicted future videos to guide action learning. The model combines generative pre-training and policy fine-tuning for multi-task robotic learning.

More on tables

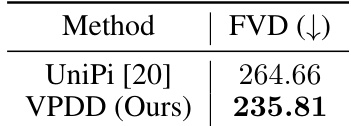

This table compares the Frechet Video Distance (FVD) scores for video generation between the proposed method, VPDD, and the baseline method, UniPi [20]. FVD is a metric for evaluating the quality of generated videos, with lower scores indicating higher quality. The results show that VPDD achieves a lower FVD score than UniPi, suggesting that VPDD generates higher-quality videos.

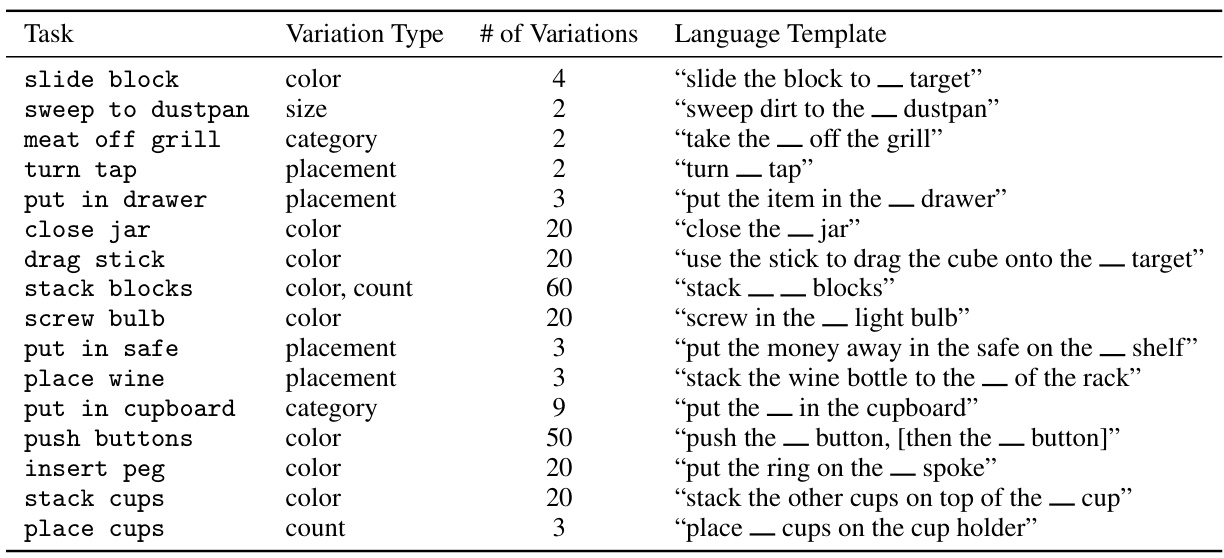

This table lists the 16 tasks selected from the RLBench benchmark for evaluation. Each task has multiple variations based on factors like color, size, count, placement, and category of objects. The table specifies the type of variation, the number of variations per task, and a template of the language instruction used for each task.

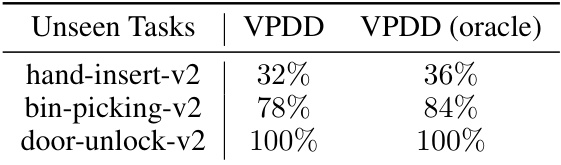

This table presents the average success rates achieved by the VPDD model on three unseen tasks: hand-insert-v2, bin-picking-v2, and door-unlock-v2. The results are shown for both the standard VPDD model and a version with oracle knowledge (VPDD (oracle)). The oracle version provides a performance upper bound by showing what could be achieved with perfect knowledge of the environment state. The comparison highlights the model’s generalization capability to unseen scenarios.

Full paper#