↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Inverse protein folding, designing protein sequences that fold into desired structures, is a challenging task with existing methods often failing due to error accumulation and inability to capture plausible sequence diversity. Discriminative models struggle to solve the one-to-many mapping problem between structures and sequences. This necessitates the exploration of alternative approaches such as generative models.

The paper introduces Bridge-IF, a generative diffusion bridge model that addresses these issues. Bridge-IF uses an expressive structure encoder to create an informative prior from structures and constructs a Markov bridge to connect it with native sequences, progressively refining the initial sequence. A novel reparameterization simplifies the loss function and improves training. By integrating structure conditions into protein language models, Bridge-IF significantly enhances generation performance and efficiency. The model outperforms existing methods in sequence recovery and design of plausible proteins, demonstrating its effectiveness in inverse protein folding.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in protein design and AI due to its novel approach to inverse protein folding. Bridge-IF’s superior performance on standard benchmarks and its exploration of Markov bridge models open exciting avenues for improved protein engineering and drug discovery. The simplified loss function and integration of protein language models also provide valuable insights for training generative models.

Visual Insights#

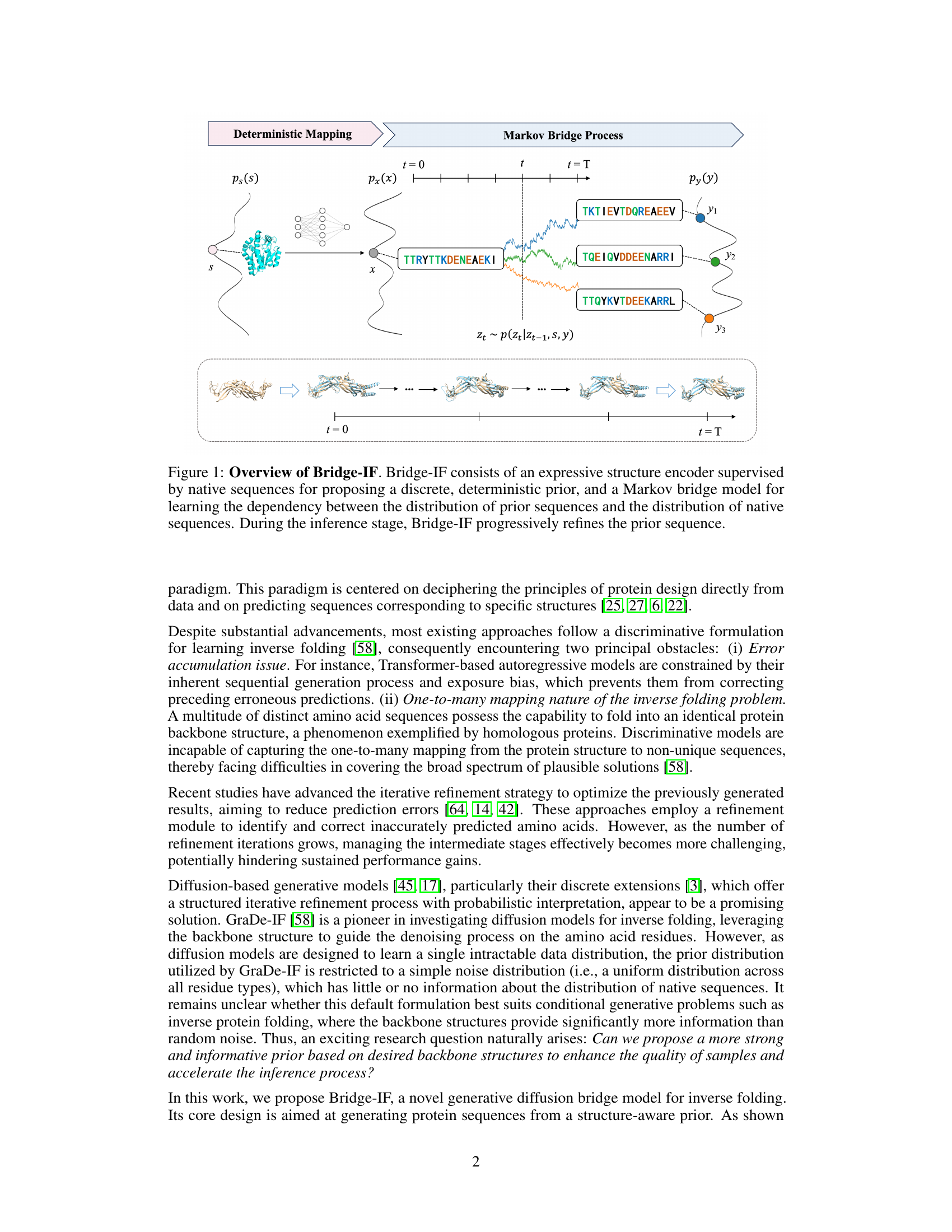

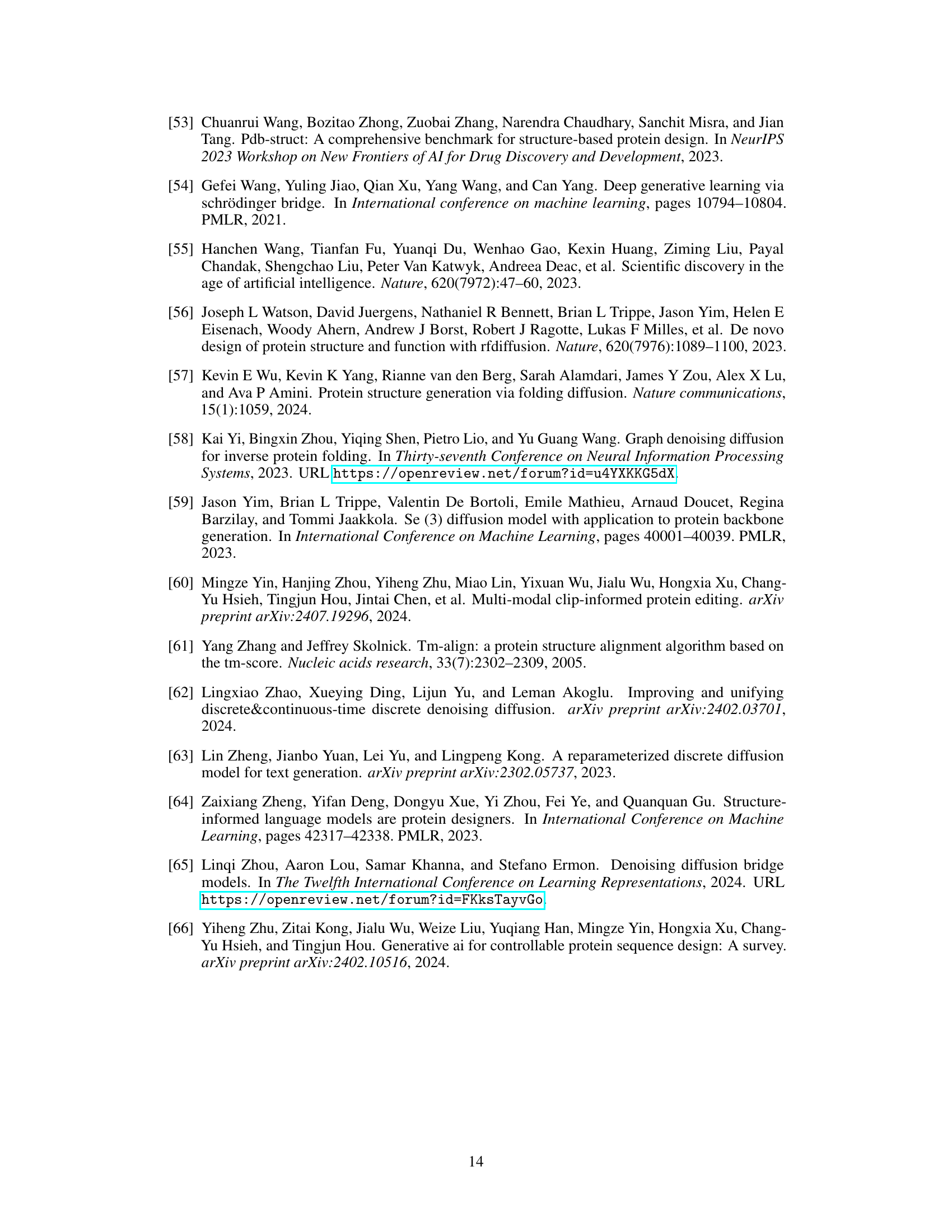

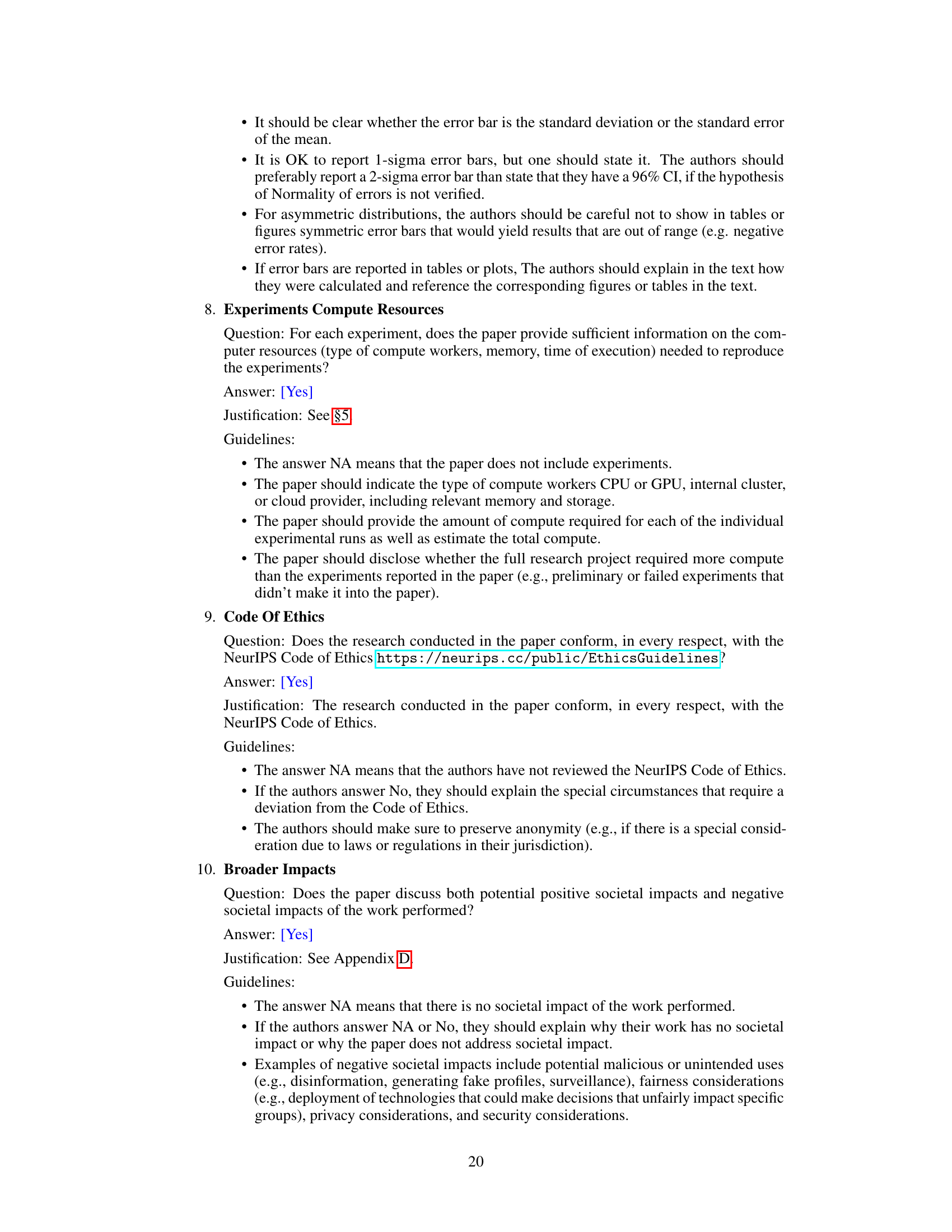

The figure illustrates the Bridge-IF model, which uses an expressive structure encoder to create a discrete prior sequence from a given protein structure. A Markov bridge model then learns the probabilistic relationship between this prior and the native sequences. During inference, the model iteratively refines the prior sequence, eventually generating a plausible protein sequence that folds into the desired structure. The diagram visually shows this process, starting with a structure (s), encoding it to a prior sequence (x), and then using a Markov bridge process (with intermediate steps represented by Zt) to arrive at a final native-like sequence (y).

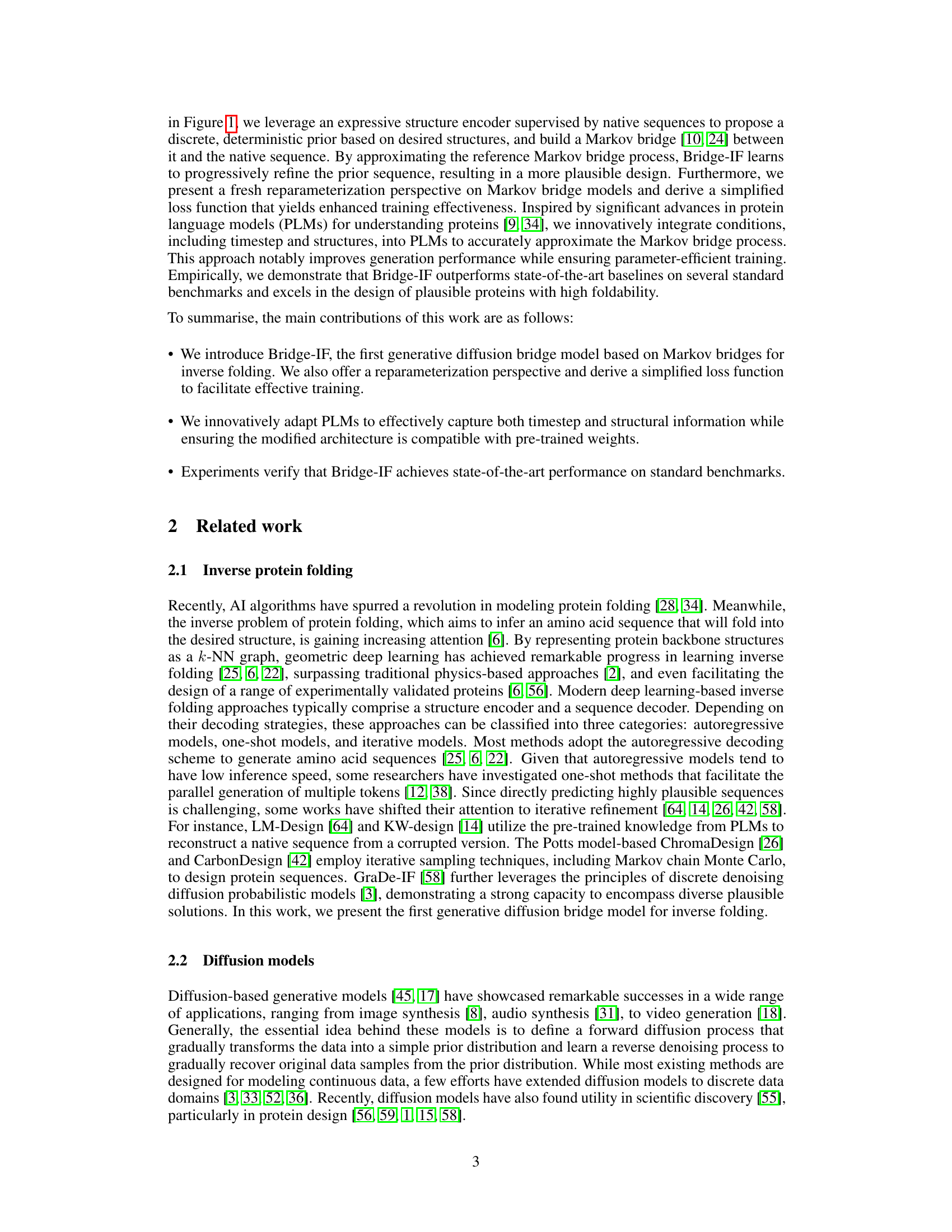

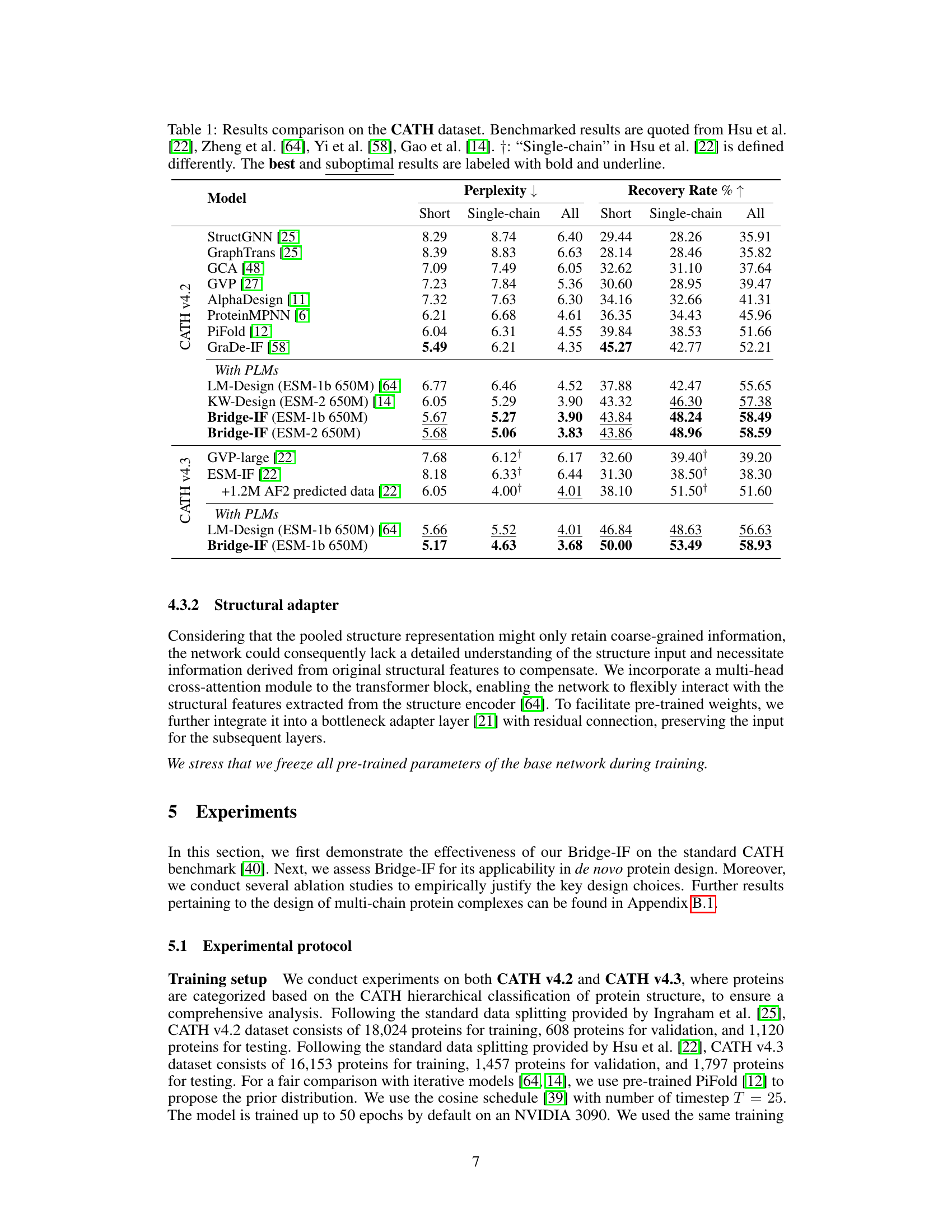

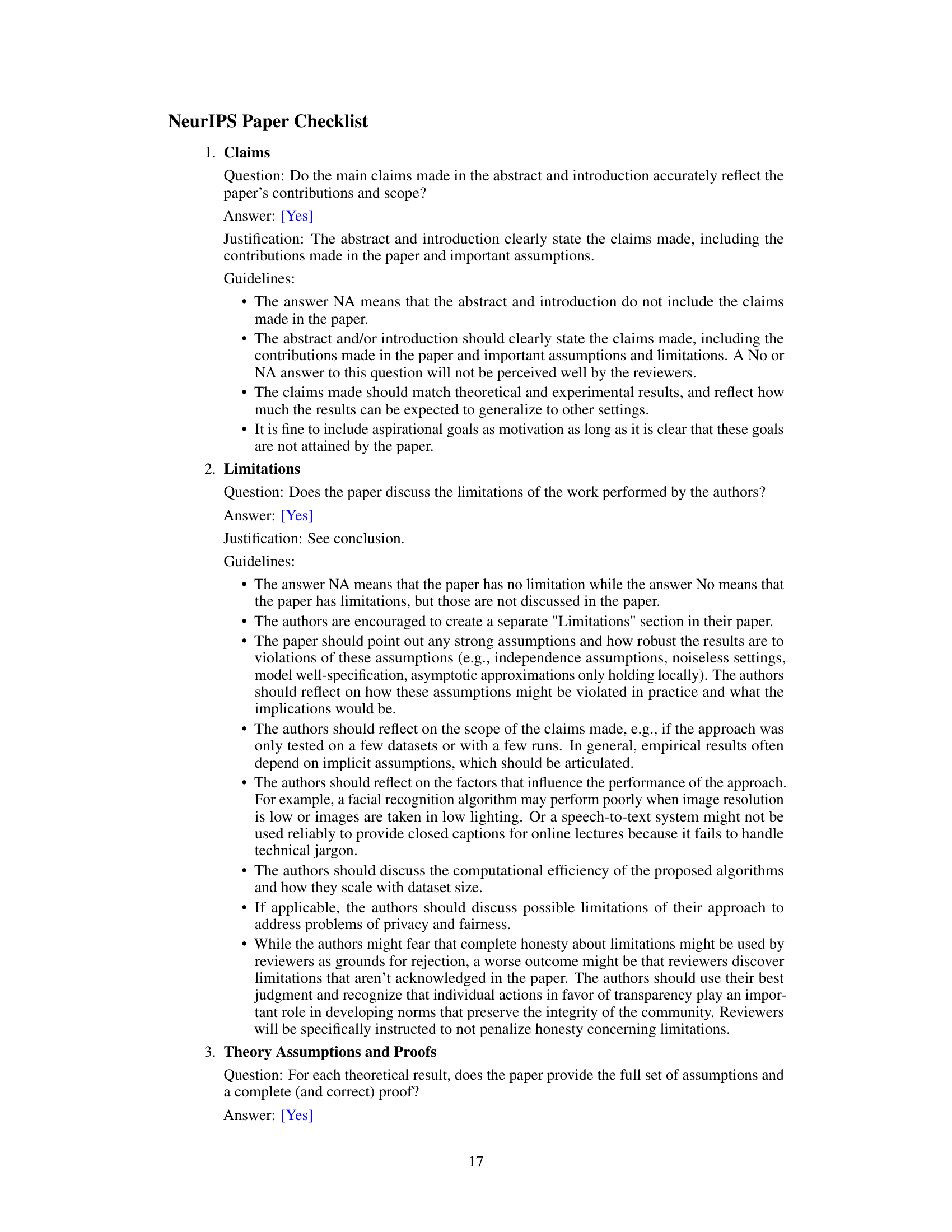

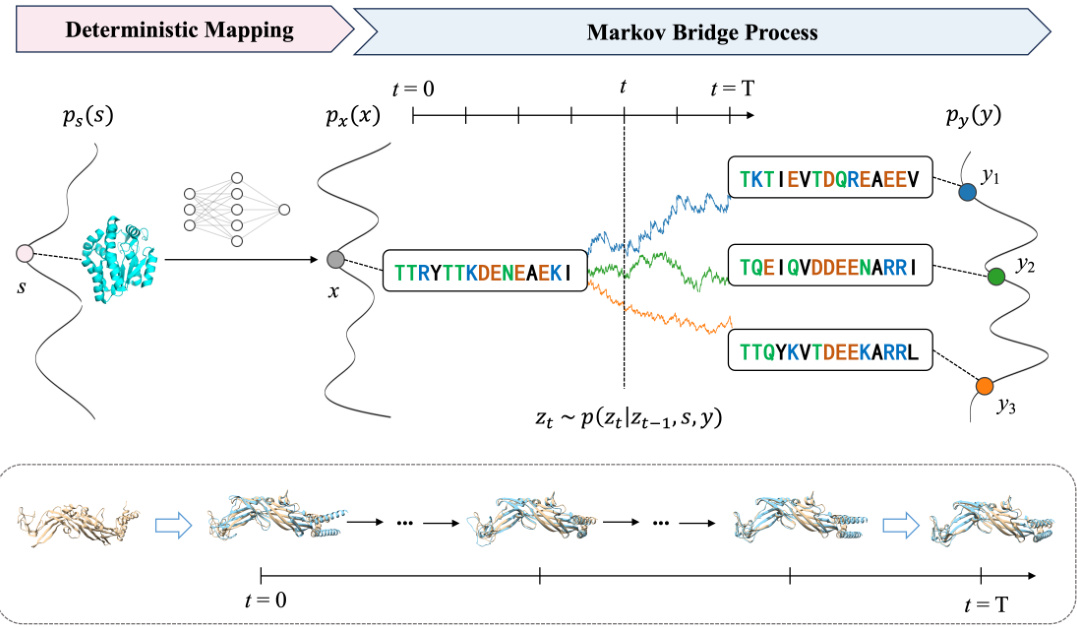

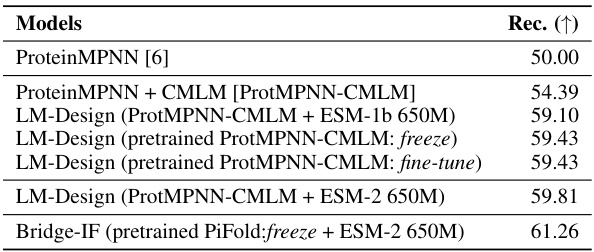

This table compares the performance of Bridge-IF with other state-of-the-art methods on the CATH dataset for inverse protein folding. It shows the perplexity (lower is better) and recovery rate (higher is better) for three protein categories: short proteins, single-chain proteins, and all proteins. Results are broken down by the language model used (ESM-1b or ESM-2) and whether or not pre-trained language models were used. The table highlights Bridge-IF’s superior performance, especially when using larger language models and improved training techniques. The ‘+’ symbol denotes different definitions of single-chain proteins among various models.

In-depth insights#

Markov Bridge Modeling#

Markov bridge modeling offers a powerful framework for bridging the gap between two probability distributions, particularly useful when dealing with intricate dependencies and high dimensionality. It elegantly connects a prior distribution with a target distribution through a carefully constructed Markov process. This process is not simply a random walk; it’s designed to progressively refine samples from the prior, ultimately yielding samples resembling the target. The approach is especially attractive for inverse problems, where the goal is to generate samples from a complex, often high-dimensional target distribution given limited information from a simpler prior. A key advantage of Markov bridge modeling is its flexibility and versatility; it’s adaptable to various data types (discrete, continuous) and problem settings. The formulation allows incorporation of external information or constraints, such as structural guidance in protein design, leading to more targeted and informative generation. However, challenges remain, notably the computational cost associated with training, especially for complex high-dimensional problems. Developing efficient and scalable algorithms is crucial for broader applicability. This modeling technique shows great promise in numerous fields, including protein design, where it addresses the challenge of the one-to-many mapping between structure and sequence.

PLM Integration#

The integration of pre-trained protein language models (PLMs) is a critical innovation in Bridge-IF, significantly enhancing its performance. Rather than simply using PLMs as sequence generators, Bridge-IF leverages PLMs to approximate the Markov bridge process. This is achieved by conditioning the PLMs with both structural information derived from the structure encoder and timestep information. This conditional approach allows for a more precise and effective refinement of the initial protein sequence, guiding the generation towards highly plausible, foldable protein sequences. The method ensures parameter efficiency by leveraging pre-trained PLMs and only modifying specific blocks within the architecture for timestep and structural integration, therefore avoiding costly retraining of the entire model. Furthermore, the use of PLMs directly in the Markov bridge process bypasses the limitations of simpler, often noise-based, prior distributions, thereby leading to improved sequence recovery rates and overall foldability. This approach highlights the power of integrating pre-trained language models with specialized probabilistic modeling techniques for complex sequence generation tasks.

Inverse Folding#

Inverse protein folding, a crucial aspect of protein design, aims to predict amino acid sequences that fold into a predetermined 3D structure. This is a challenging task because of the many-to-one mapping between sequences and structures, and the complexity of protein folding physics. Traditional physics-based approaches have limitations, while recent machine learning methods, particularly discriminative models, often struggle with error accumulation. Generative models, especially diffusion models, offer a promising alternative, as they can capture the inherent probabilistic nature of the problem and potentially generate diverse plausible sequences. However, challenges remain in effectively incorporating structural information into these models to improve their accuracy and efficiency, and in handling the extensive variety of possible sequences that can fold into the same structure. The development of effective structure-aware generative models for inverse folding is an important area of active research, with potential applications in protein engineering, drug discovery, and synthetic biology.

Simplified Loss#

A simplified loss function is crucial for efficient training of complex models, especially in computationally demanding tasks like inverse protein folding. The core idea is to approximate a complex objective function with a simpler, more tractable one that maintains essential properties—primarily the ability to guide the model towards accurate predictions. This often involves reformulating the original loss using mathematical techniques like reparameterization or variational approximations to reduce the computational burden. For instance, it might involve replacing computationally expensive operations like Kullback-Leibler divergence calculations with simpler alternatives, like cross-entropy. Using a simplified loss can improve training stability, leading to faster convergence and better generalization performance. However, simplification must be done carefully to avoid losing critical information from the original objective that could affect the model’s accuracy. The effectiveness of a simplified loss is ultimately judged by its ability to train a model which achieves comparable or better performance while simultaneously shortening training time.

Future Directions#

Future research directions for inverse protein folding could focus on improving the expressiveness and efficiency of generative models by exploring advanced architectures like diffusion models, transformers, and graph neural networks. Incorporating more diverse and comprehensive datasets that include multi-chain proteins, various post-translational modifications, and different experimental conditions is crucial. Furthermore, developing robust evaluation metrics that accurately capture foldability, stability, and functionality beyond simple sequence recovery rate would enhance the field’s progress. Finally, integrating inverse protein folding models with protein design and engineering tools for more practical applications in drug discovery, synthetic biology, and materials science presents exciting opportunities.

More visual insights#

More on figures

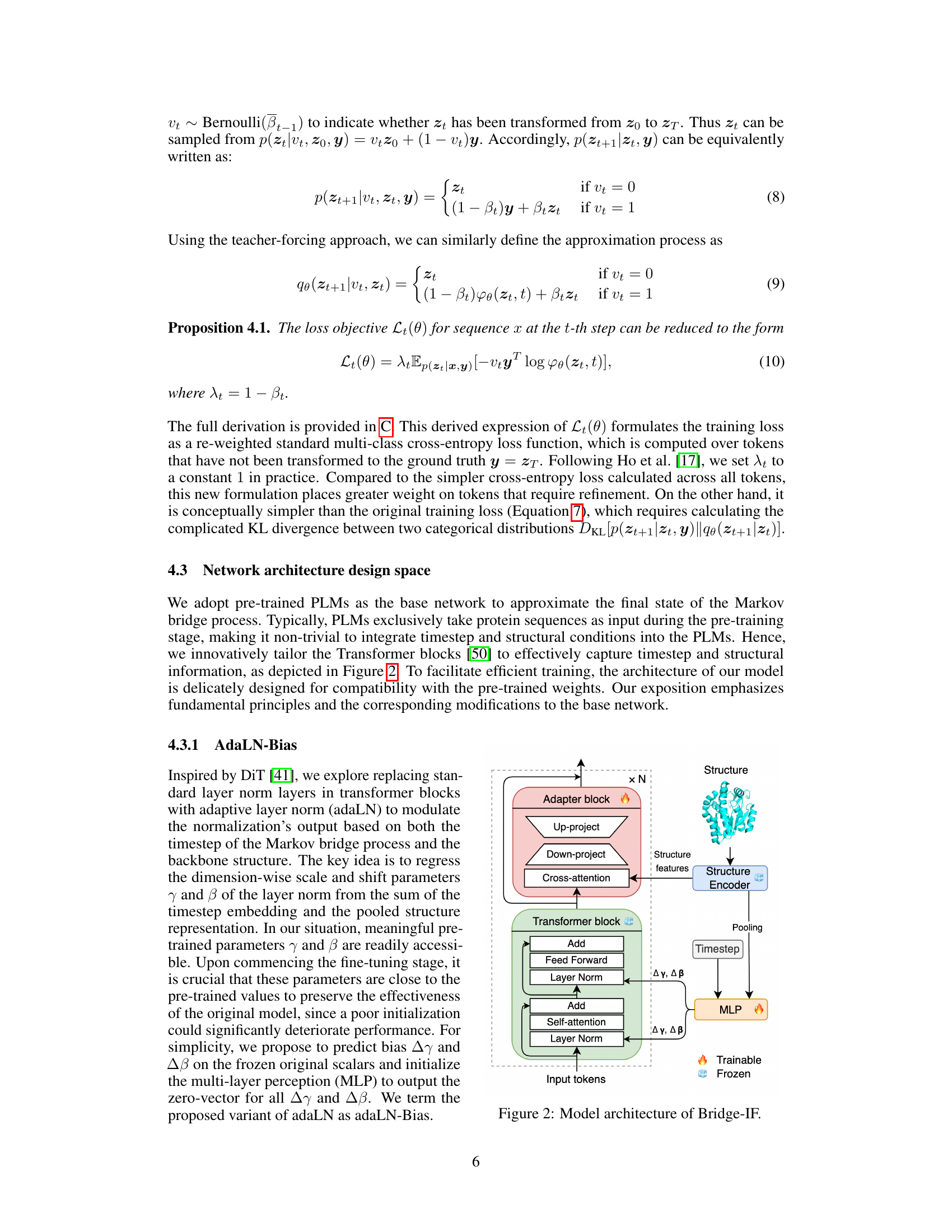

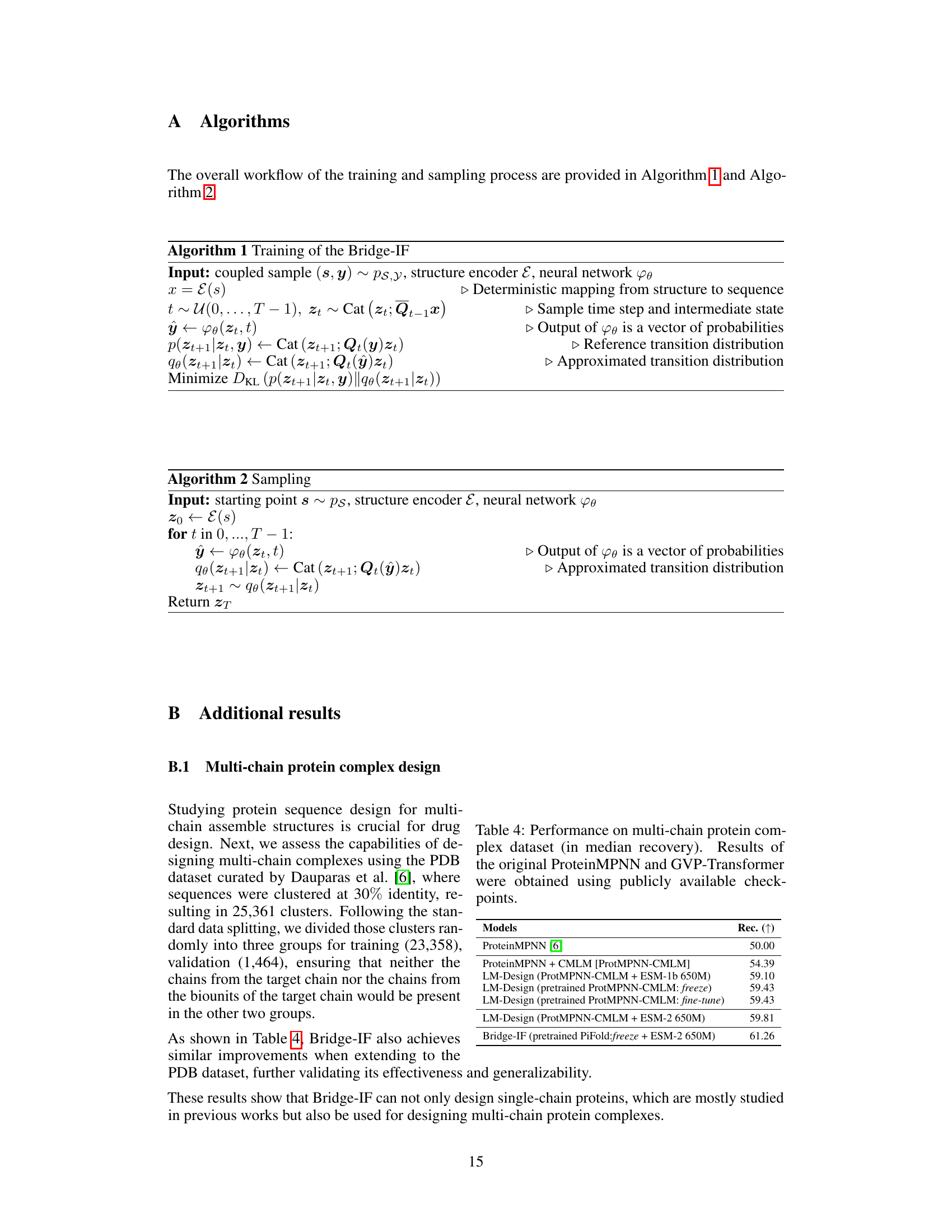

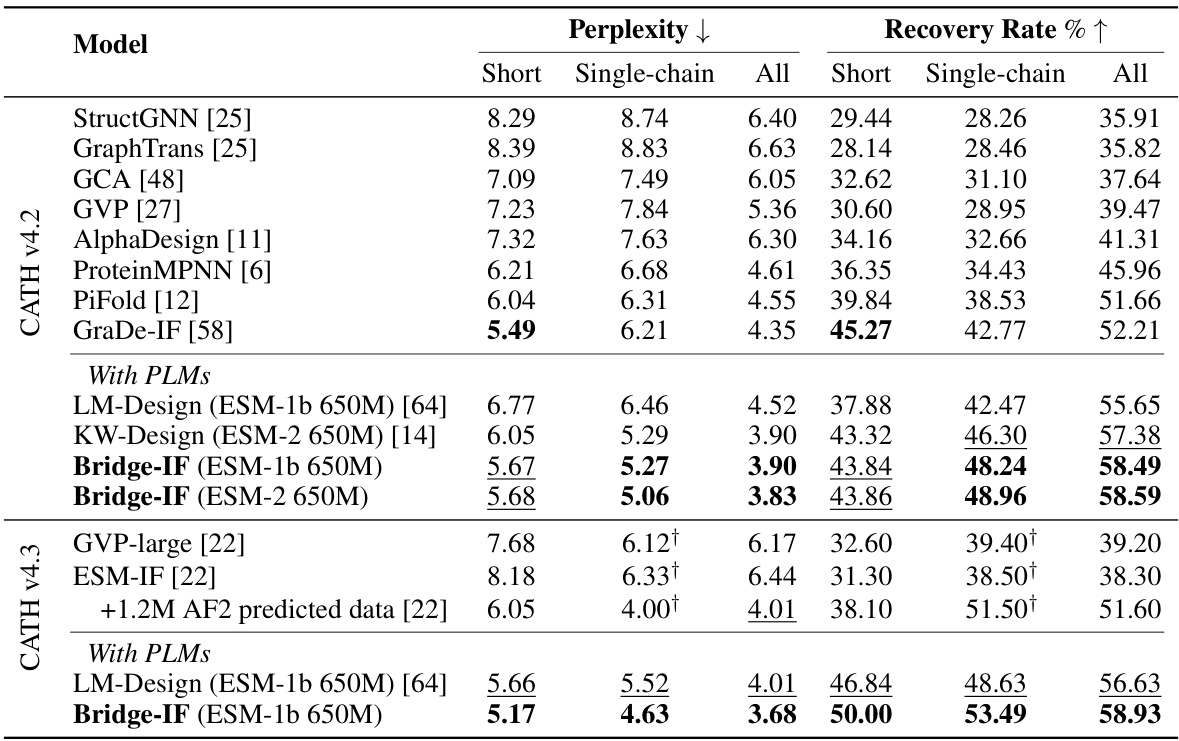

The figure illustrates the architecture of Bridge-IF, a model for inverse protein folding. It shows how a structure encoder processes structural information, and how this information, along with timestep embeddings, is used to modulate a Transformer block. This block then generates a protein sequence by progressively refining an initial sequence. The figure highlights which parts of the model are trainable and which parts are frozen, emphasizing the use of pre-trained weights to ensure efficient training.

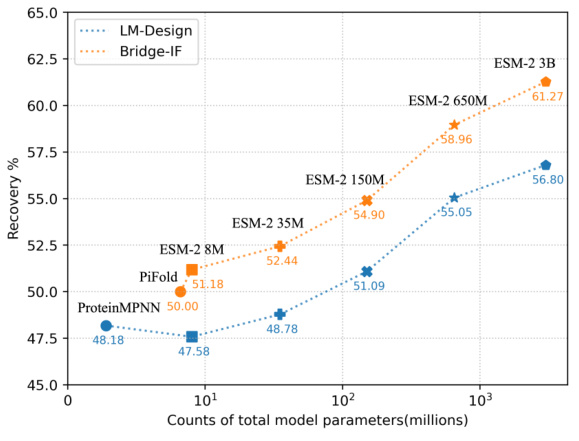

This figure shows the performance comparison of Bridge-IF and LM-Design models with varying scales of ESM-2 PLMs on the CATH 4.3 dataset. The x-axis represents the total number of model parameters (in millions), while the y-axis shows the recovery rate (%). The graph illustrates how the performance of both models improves with larger model sizes, demonstrating a scaling law in logarithmic scale. Bridge-IF consistently outperforms LM-Design across all model sizes. The figure highlights the scaling behavior of the two models, indicating that increasing model size improves performance in inverse protein folding.

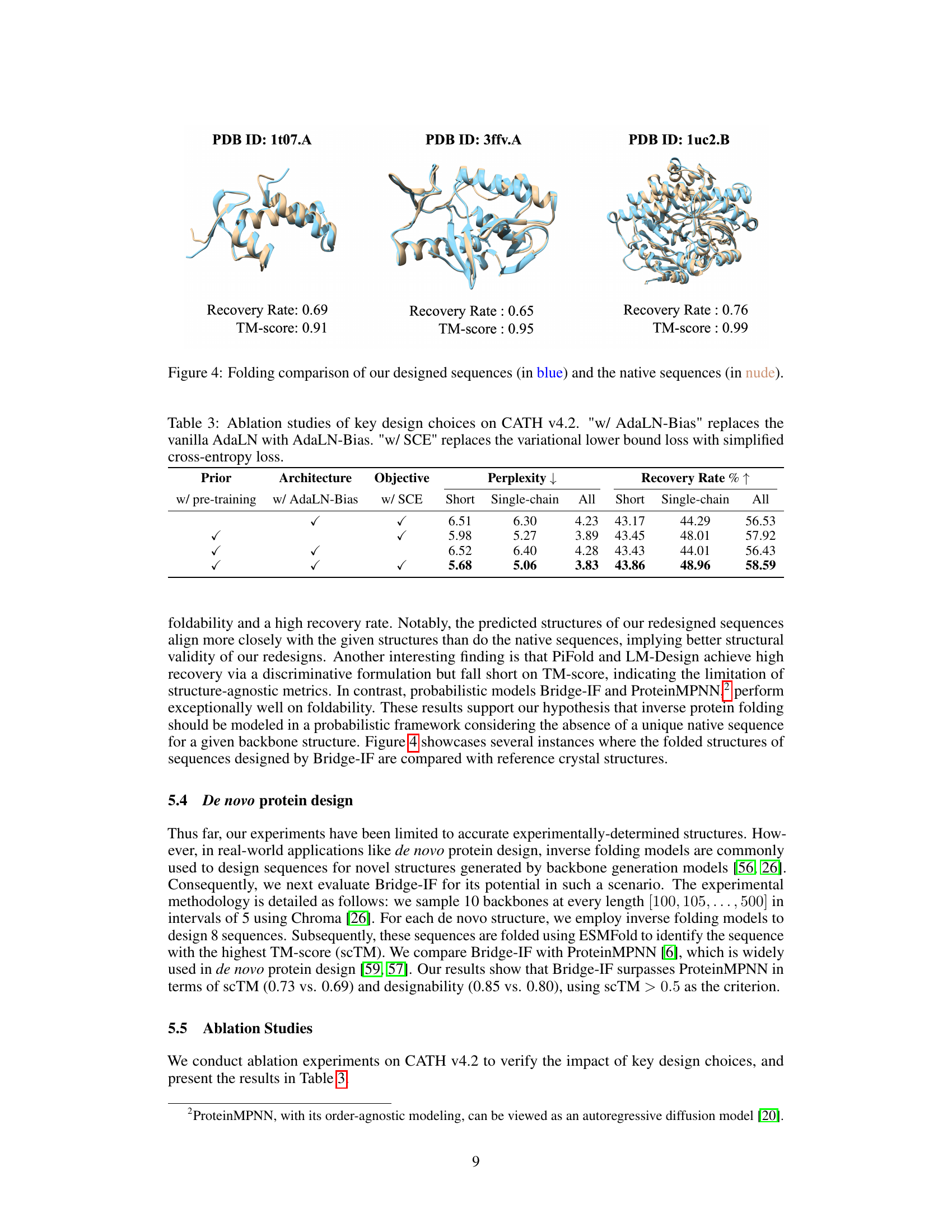

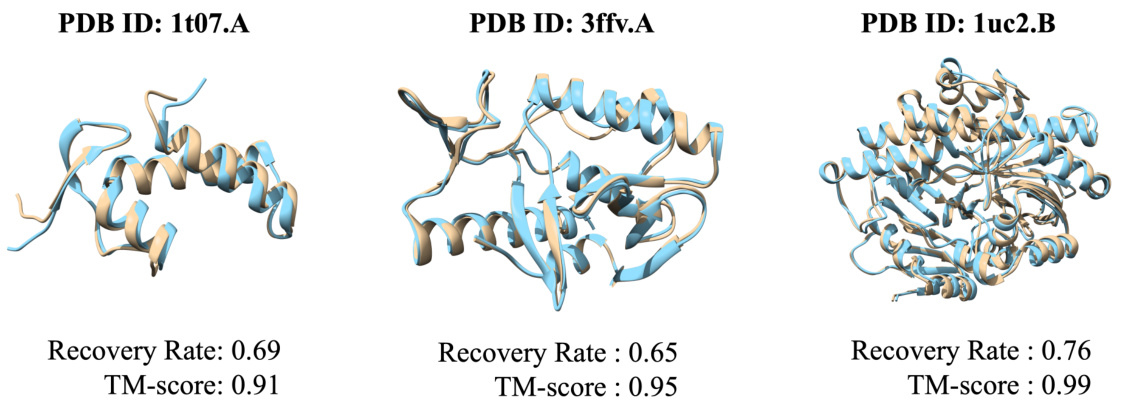

This figure presents a visual comparison of protein structures. It showcases three examples where the predicted protein structures generated by the Bridge-IF model are compared with their corresponding native structures. Each example includes the protein ID (PDB ID), the recovery rate, and the TM-score (TM-score measures structural similarity). The predicted structures are shown in light blue, while the native structures are in beige. The visual comparison allows assessing the accuracy and quality of the protein structures generated by the Bridge-IF model.

More on tables

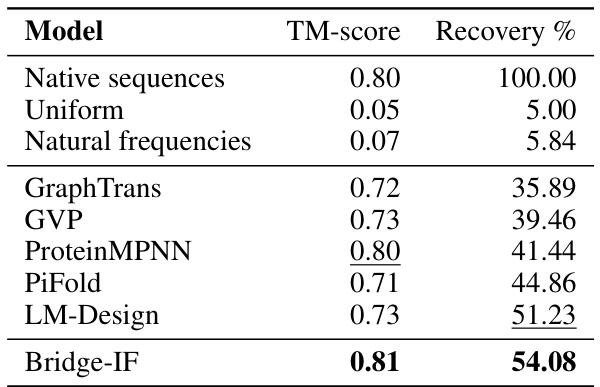

This table compares the performance of different inverse folding methods in terms of TM-score and recovery rate. The TM-score measures the similarity between the predicted and native protein structures, while the recovery rate reflects the accuracy of sequence recovery. The methods are compared against a baseline of native sequences, and also against simpler approaches using uniform or natural frequencies of amino acids. The table highlights that Bridge-IF achieves the best performance in terms of both TM-score and recovery rate.

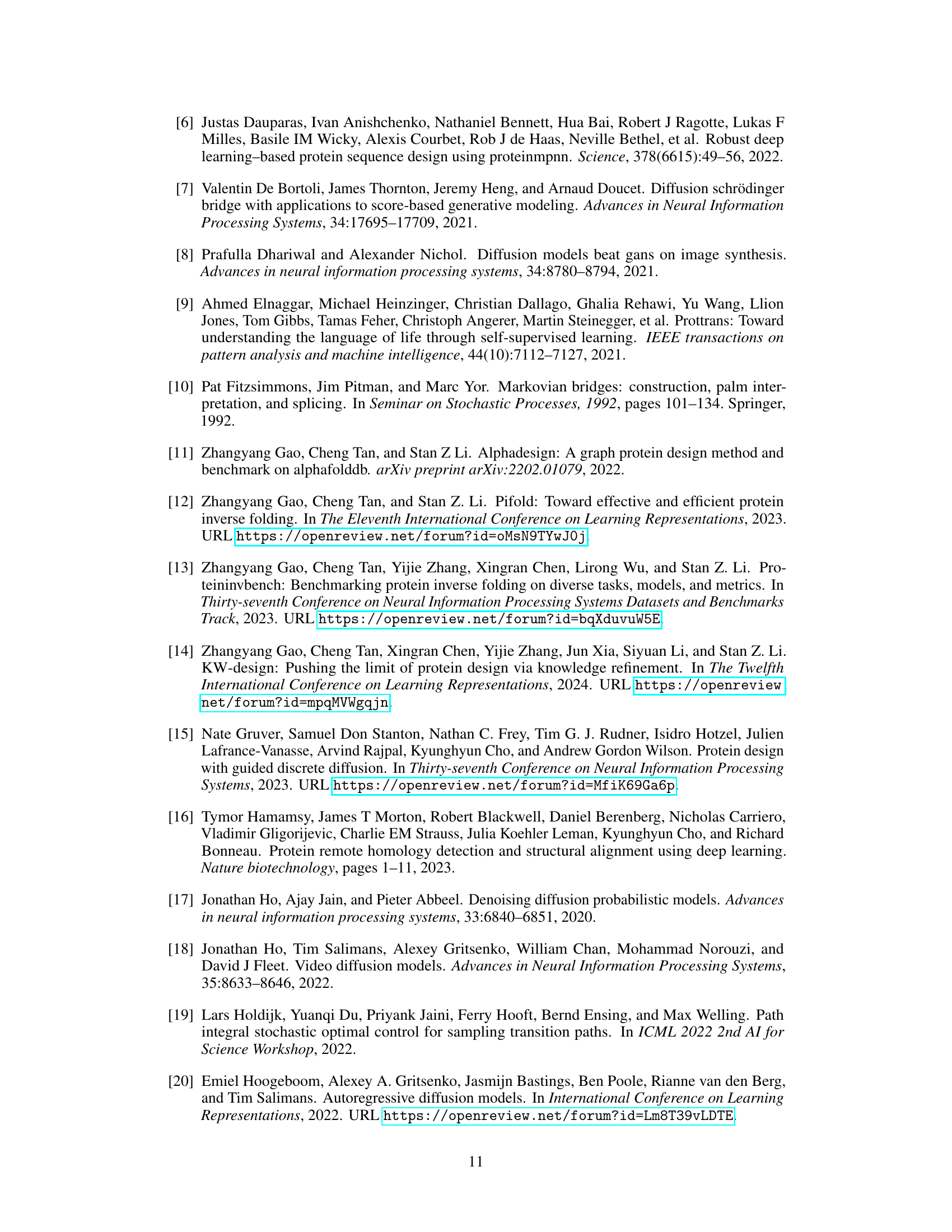

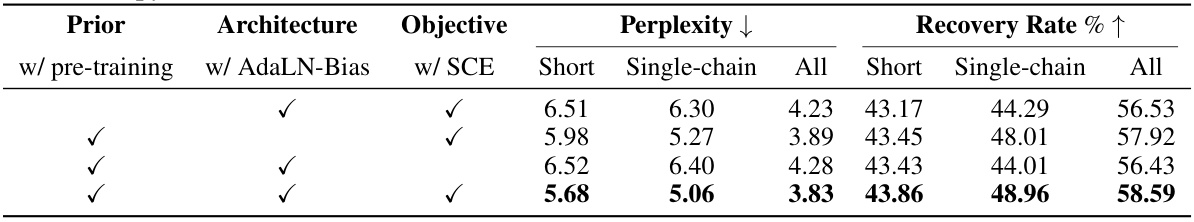

This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted to evaluate the impact of key design choices in the Bridge-IF model. The studies focus on three aspects: the use of pre-training, AdaLN-Bias (a modified adaptive layer normalization), and the simplified cross-entropy loss (SCE). By comparing the performance metrics (perplexity and recovery rate) across different combinations of these design choices, the table helps to understand their individual contributions and the overall effectiveness of the Bridge-IF model.

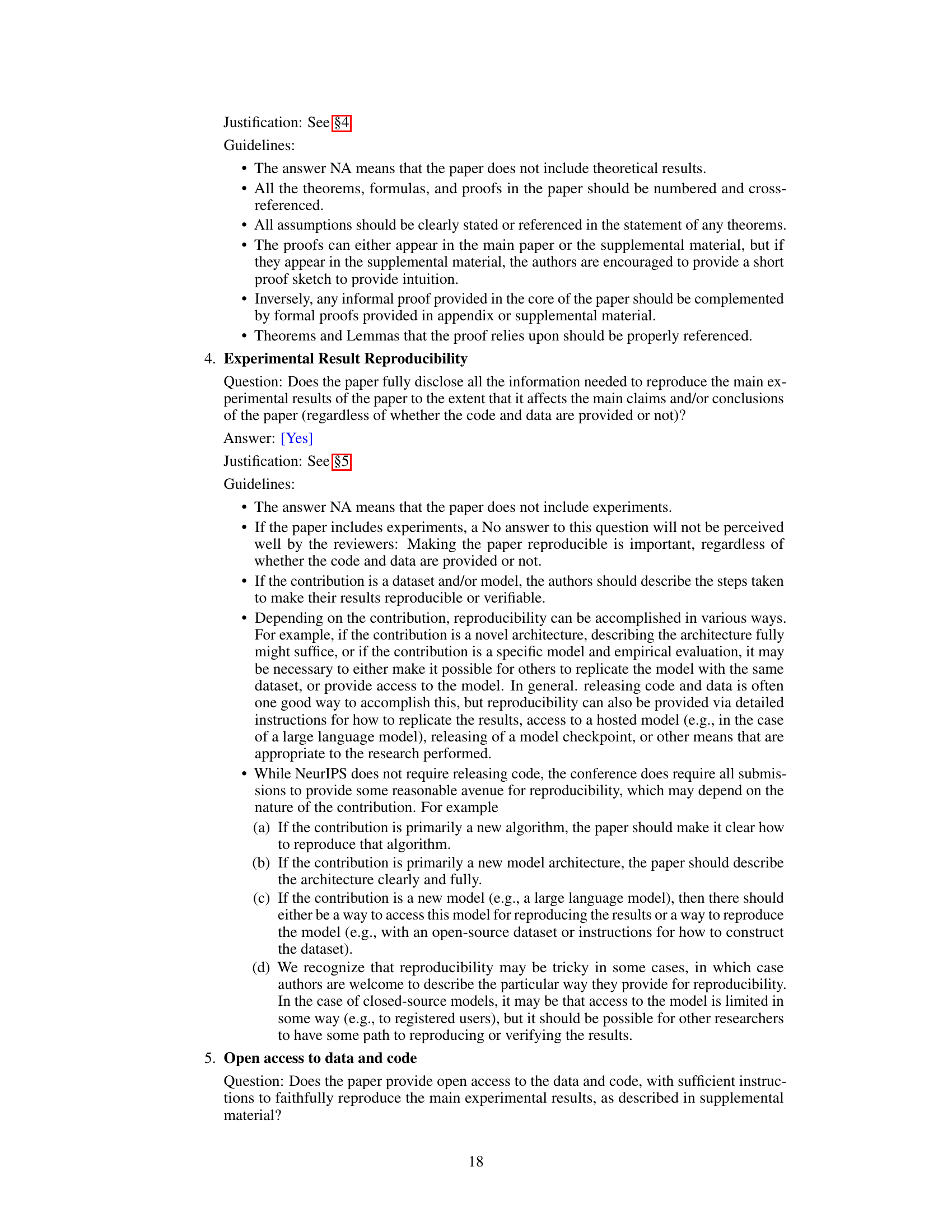

This table presents the performance of different models on a multi-chain protein complex dataset. The median recovery rate is used as the evaluation metric. The models compared include ProteinMPNN, ProteinMPNN with CMLM, LM-Design with different combinations of pre-trained models (ProtMPNN-CMLM and ESM-1b or ESM-2), and Bridge-IF with a pre-trained PiFold model and ESM-2. The results show that Bridge-IF achieves the best performance, demonstrating its effectiveness in designing multi-chain protein complexes.

Full paper#