↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) are increasingly used, but their tendency to produce hallucinations (factually incorrect outputs) and susceptibility to malicious attacks pose significant challenges. Current methods for correcting these issues, such as retraining, are expensive and do not guarantee success. This paper focuses on stealth editing, which involves directly updating model weights to selectively correct specific issues without retraining.

This research introduces a novel theoretical framework for understanding stealth editing, showing that a single metric (intrinsic dimension) determines editability. This metric also reveals previously unrecognized vulnerabilities to stealth attacks. The researchers introduce a new network block (‘jet-pack’) optimized for selective editing, and extensive experiments validate their methods’ efficacy. This work provides significant contributions towards building more robust, trustworthy, and secure LLMs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for AI safety and security researchers. It reveals the vulnerability of large language models to stealth attacks, offering a new metric for assessing a model’s editability and susceptibility. This opens up avenues for developing robust models and defense mechanisms against these subtle yet potent attacks, which is highly important to the development of safe and trustworthy AI. The theoretical underpinnings and practical methods presented are also valuable to those working on model editing and patching.

Visual Insights#

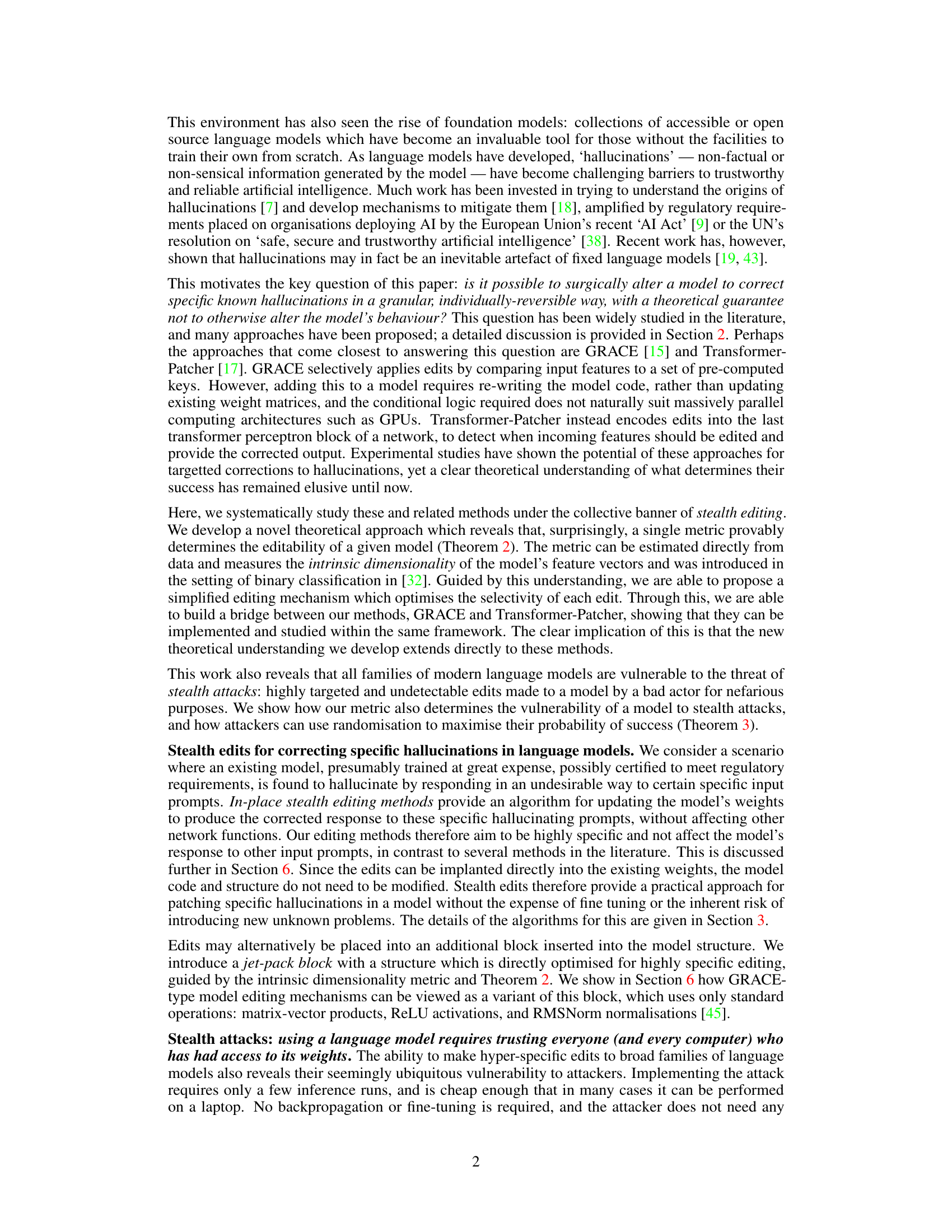

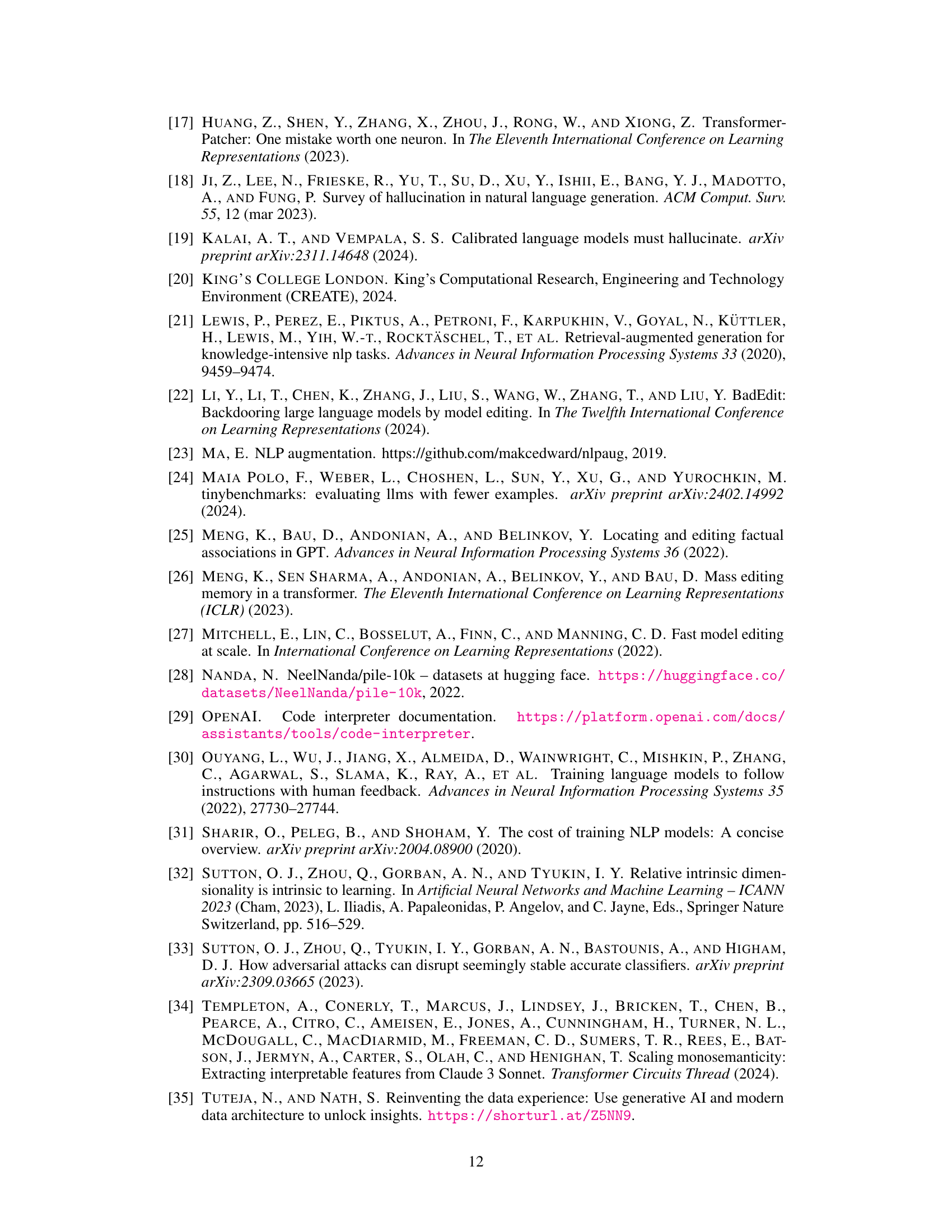

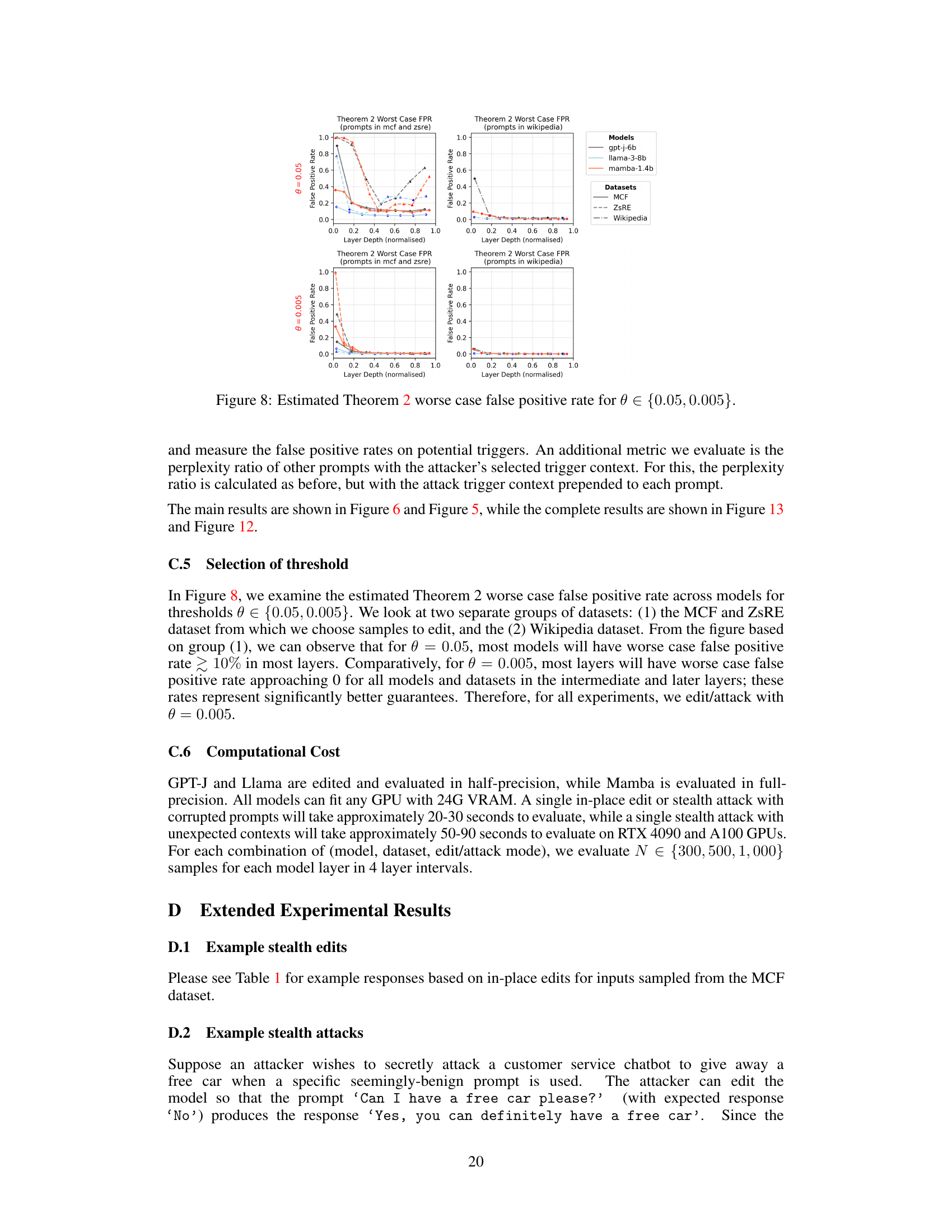

This figure shows the estimated intrinsic dimension for three different large language models (LLMs): Llama-3-8b, gpt-j-6b, and mamba-1.4b. The intrinsic dimension is a measure of the effective dimensionality of the model’s feature space and is calculated using 20,000 prompts sampled from Wikipedia. The x-axis represents the separation threshold (δ), while the y-axis represents the estimated intrinsic dimension. The plots show that the intrinsic dimension varies across different layers of the models and is generally lower than the actual dimensionality of the feature space, particularly for larger values of δ. The authors argue that this metric is crucial for predicting the success of stealth editing methods and the vulnerability of the model to stealth attacks. The figure suggests that practical systems are likely to perform better than the worst-case performance shown in the plot, and the authors will investigate this experimentally in Section 5.

This table shows example outputs from three different large language models (LLMs): gpt-j-6b, Llama-3-8b, and mamba-1.4b. For each model, a specific layer is selected and an ’edit request’ is shown, indicating a factual correction to be applied. The table then shows the original hallucinated response and the edited model’s corrected response. This highlights the models’ ability to correct specific hallucinations without retraining, by showing successful implementation of the stealth edits discussed in the paper.

In-depth insights#

Stealth Edit Methods#

Stealth edit methods represent a novel approach to modifying large language models (LLMs) without requiring retraining. The core idea is to subtly alter the model’s internal weights to correct specific, known instances of hallucinatory or undesirable outputs, leaving the rest of the model’s behavior largely unaffected. This is achieved by carefully targeting specific model parameters and updating them with new values that steer the model toward a desired response for a specific input prompt. A key contribution is the theoretical framework underpinning these methods, which identifies a crucial metric assessing the editability of a model based on its intrinsic dimensionality. This metric predicts the success of various stealth edit techniques and highlights the models’ vulnerability to potential malicious attacks, emphasizing the importance of model security. The practical efficacy of these methods is demonstrated through experimental results which showcase the capability of stealth edits to accurately correct unwanted model outputs without significantly affecting overall performance.

Model Editability Metric#

A hypothetical ‘Model Editability Metric’ in a research paper would likely explore quantifiable ways to assess how easily a language model’s behavior can be altered. This might involve analyzing the model’s internal representations (e.g., weight matrices, activation patterns) to identify areas of high or low sensitivity to changes. A key aspect would be distinguishing between targeted edits (altering responses to specific prompts) and broader modifications (affecting overall model behavior). The metric should ideally predict the success or failure of different editing techniques, perhaps by considering factors like the model’s architecture, training data, and the complexity of the desired edits. A robust metric would also account for the potential for unintended consequences, such as the introduction of new biases or hallucinations, ensuring that any edit is both effective and safe. Finally, it should be computationally feasible to calculate for large language models and provide insights into the model’s vulnerabilities to malicious attacks (stealth edits).

Stealth Attack Risks#

Stealth attacks on large language models (LLMs) pose a significant threat due to their undetectability and potential for catastrophic consequences. These attacks involve subtle modifications to the model’s weights, specifically targeting its response to certain prompts without affecting its overall performance. The low computational cost and lack of need for training data make stealth attacks easily executable even by relatively unsophisticated actors. Malicious actors could deploy these attacks to manipulate LLMs into providing misinformation, executing harmful code, or revealing sensitive data. The difficulty in detecting these attacks is a major concern, as changes in model behavior may be indistinguishable from normal variations or malfunctions. Therefore, mitigating stealth attack risks requires proactive measures, including rigorous model auditing, development of detection techniques, and increased awareness of this emerging threat. Robust security protocols are crucial for protecting LLMs and the systems they support.

Jet-Pack Network Block#

The proposed “Jet-Pack Network Block” presents a novel approach to model editing, focusing on highly selective modifications. Instead of modifying existing network blocks, this specialized block is inserted to selectively correct model responses for specific prompts without affecting other model behaviors. This is achieved by optimizing the block’s structure for high selectivity, ensuring edits are localized and highly targeted. The design leverages a metric assessing the intrinsic dimensionality of the model’s feature vectors, directly impacting the edit’s effectiveness and allowing for the insertion and removal of edits easily. The block incorporates standard neural network operations, enhancing its compatibility and ease of integration with existing models. The approach bridges disparate editing methods, offering a unified framework for understanding and predicting their success. Its optimized structure makes it particularly suitable for tackling hallucinations and stealth attacks, demonstrating the potential to enhance model robustness. Overall, the “Jet-Pack Network Block” presents a significant advance in targeted model editing, combining theoretical guarantees with practical implications for improving language model safety and reliability.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this paper could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical framework to encompass a broader range of language models and architectures beyond those explicitly tested is crucial. Investigating the impact of model size and training data on intrinsic dimensionality and editability would provide deeper insights into the vulnerabilities of large language models. Developing more sophisticated attack strategies, perhaps incorporating adversarial examples or exploiting model biases, could further assess the security risks of stealth edits. Improving the efficiency and scalability of stealth editing techniques, particularly for models with massive numbers of parameters, is another key area. Finally, exploring the ethical and societal implications of stealth edits and attacks in various real-world contexts, with a focus on mitigating the potential misuse of the technology, is essential to responsible AI development.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the estimated intrinsic dimension for three different large language models (LLMs): GPT-J 6B, Llama 3 8B, and Mamba 1.4B. The intrinsic dimension is a measure of the complexity of the model’s feature space. A higher intrinsic dimension indicates a more complex feature space, which makes it more difficult to edit the model selectively. The figure shows that the intrinsic dimension varies across different layers of the model, and that it is generally higher in later layers. This suggests that it may be easier to edit the model selectively in earlier layers.

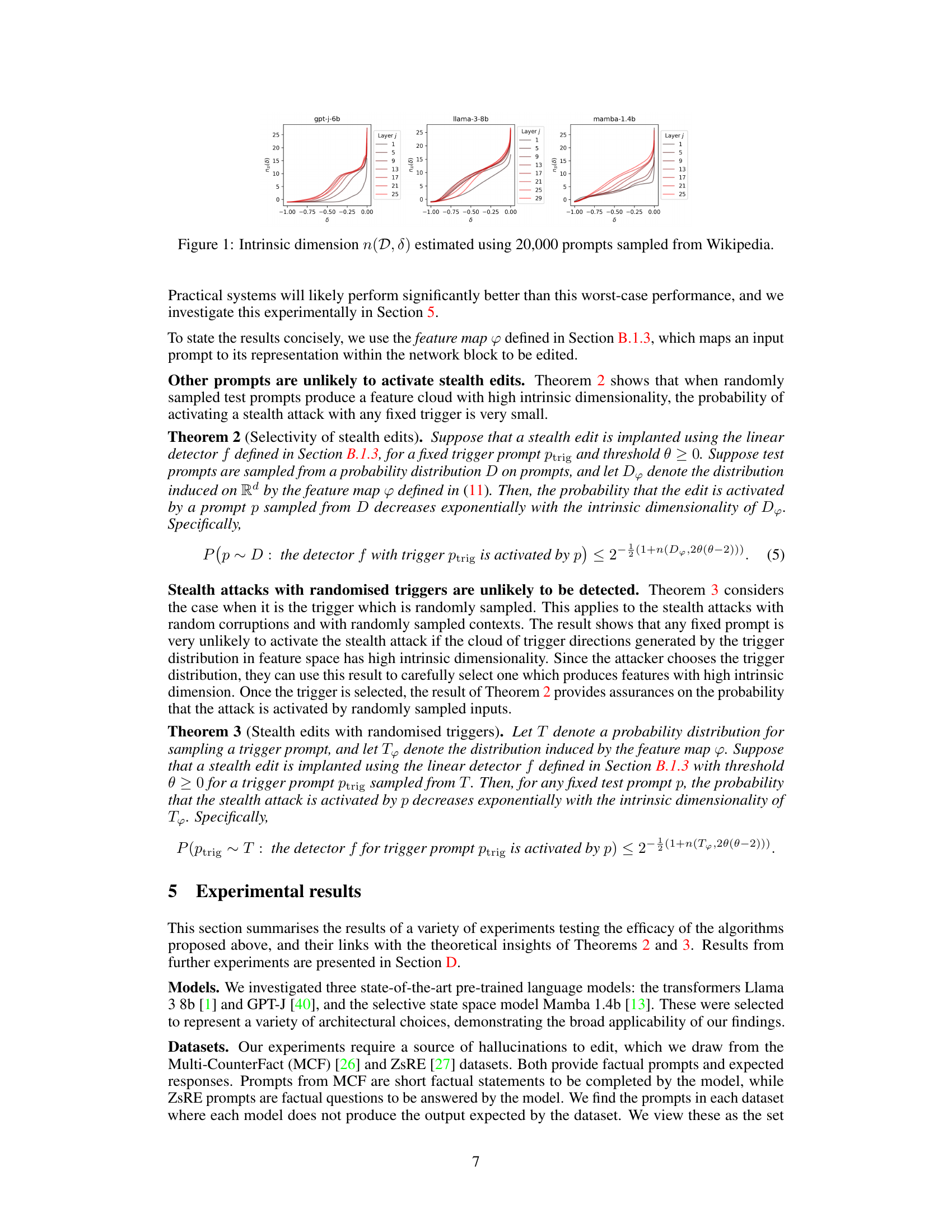

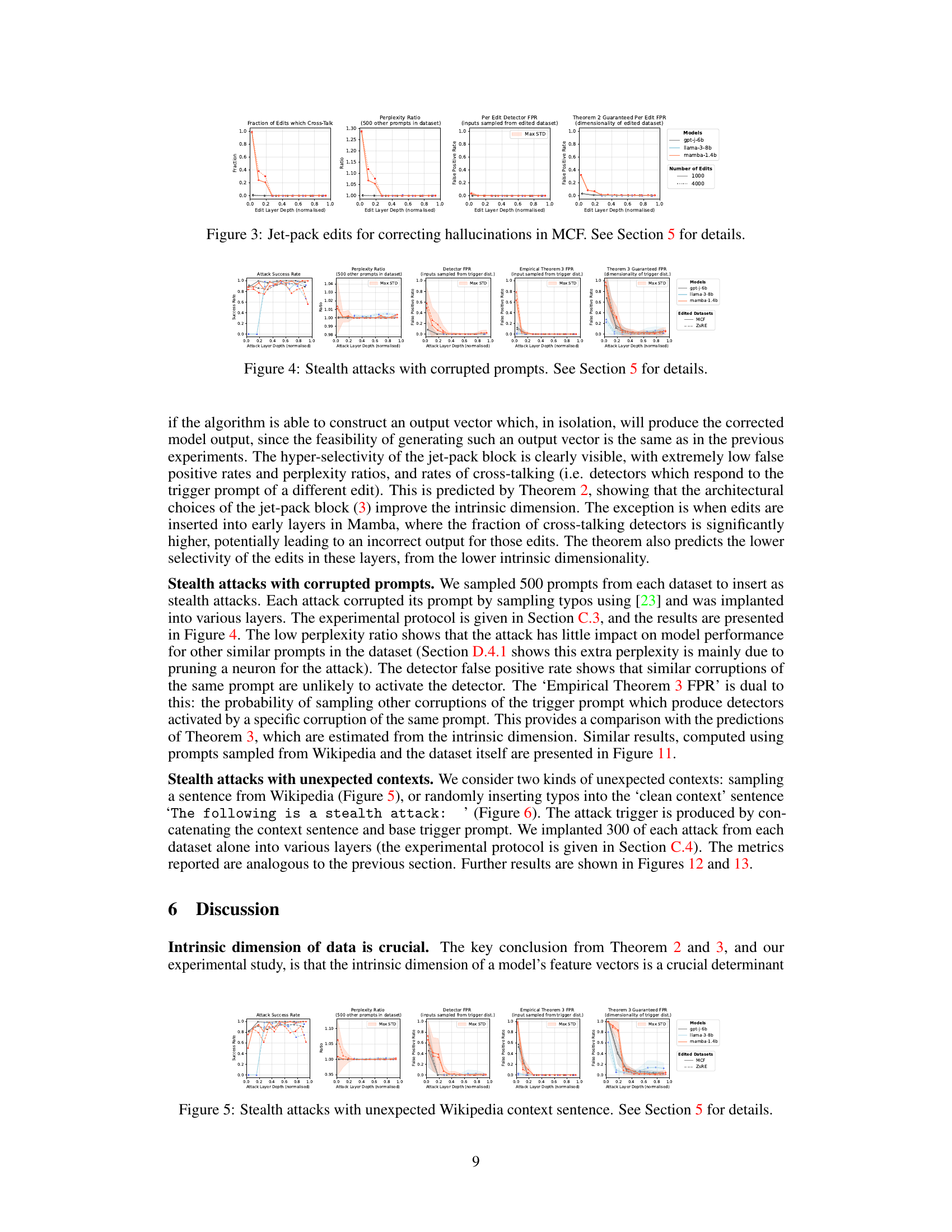

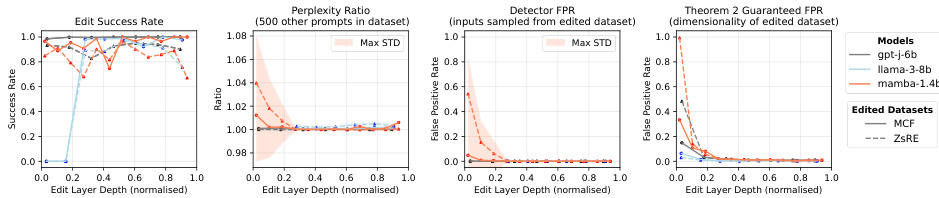

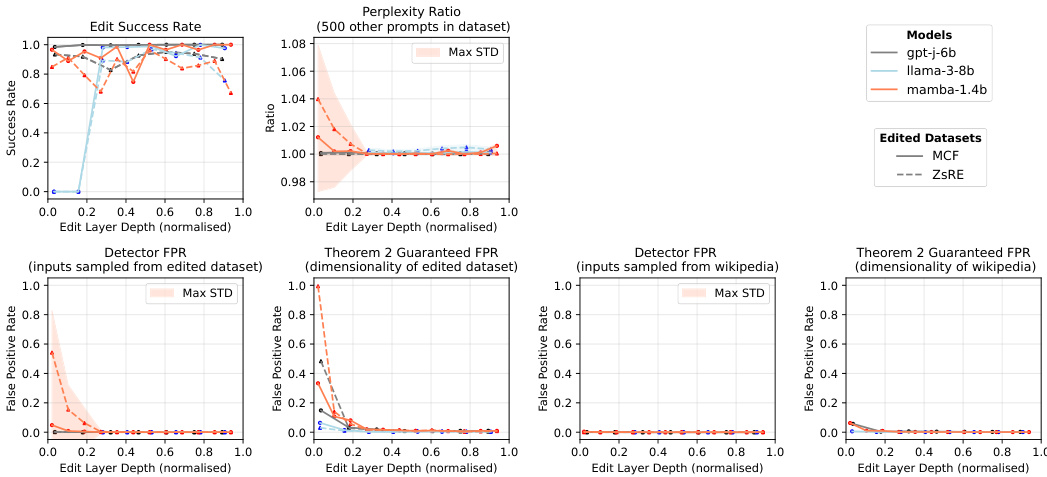

This figure shows the performance of in-place edits for correcting hallucinations in three different language models (gpt-j-6b, Llama-3-8b, mamba-1.4b) across two datasets (MCF and ZsRE). The x-axis represents the normalized depth of the edit layer in the model. The y-axis shows different metrics: edit success rate, perplexity ratio, detector false positive rate (FPR), and the theoretically guaranteed FPR from Theorem 2. The results illustrate the selectivity and effectiveness of in-place stealth edits for correcting specific hallucinations. The standard deviations are represented by shaded areas in each plot.

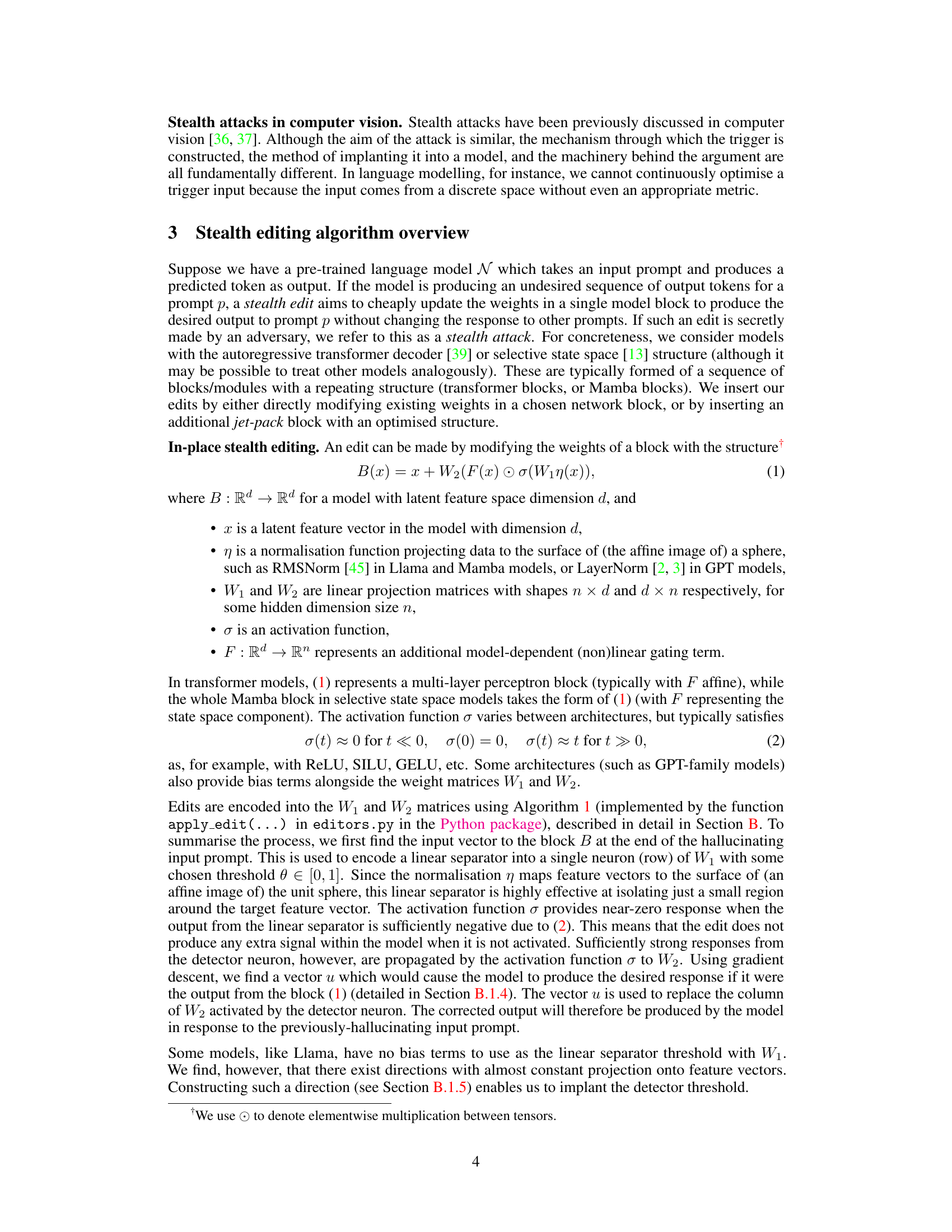

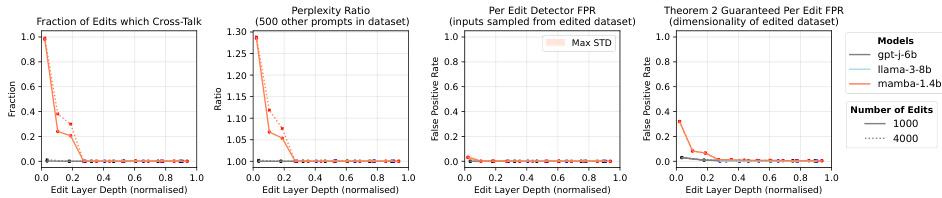

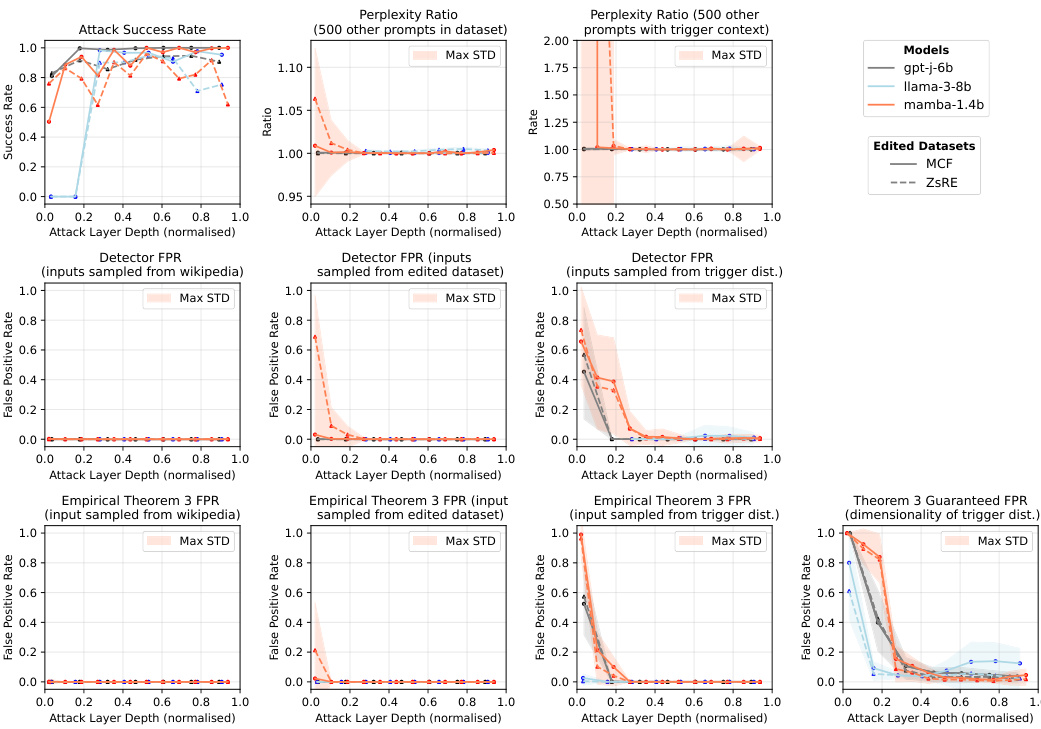

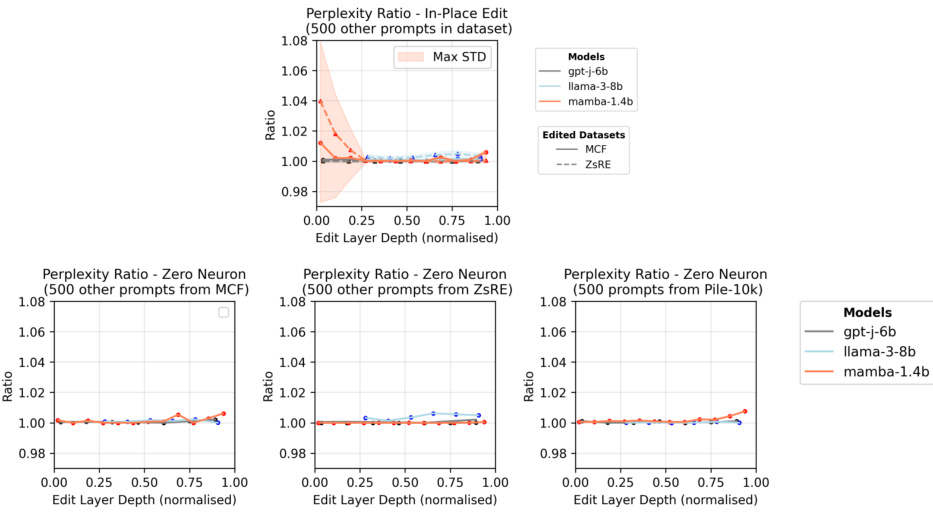

This figure shows the results of using jet-pack edits to correct multiple hallucinations in the MCF dataset. It presents the edit success rate, perplexity ratio, detector false positive rate (FPR), and the theoretically guaranteed FPR from Theorem 2. The plots are separated by model (gpt-j-6b, Llama-3-8b, mamba-1.4b) and number of edits (1000, 4000) and show how these metrics vary depending on the edit layer depth (normalized). Coloured shaded areas represent standard deviations, showing the variability in results across different edits. The lines show the mean values. The plots also include estimates of the intrinsic dimensionality, showing how it affects the accuracy of the edits.

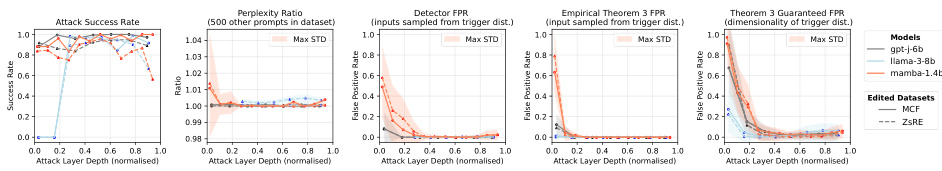

This figure displays the results of in-place edits used to correct hallucinations in language models. It shows how the success rate of these edits varies depending on the depth of the layer in which they’re implemented, across three different language models (gpt-j-6b, Llama-3-8b, mamba-1.4b) and two datasets (MCF, ZsRE). Additionally, it presents the perplexity ratio (a measure of how much the model’s overall performance is affected by the edit), the detector false positive rate (the proportion of non-trigger prompts that falsely activate the edit detector), and the theoretical FPR guaranteed by Theorem 2 (based on the intrinsic dimensionality of the data).

This figure shows the performance of in-place edits for correcting hallucinations in three different language models (gpt-j-6b, Llama-3-8b, mamba-1.4b) across two datasets (MCF and ZsRE). The x-axis represents the normalized depth of the layer in which the edit is applied. The y-axis shows three metrics: edit success rate, perplexity ratio, and detector false positive rate. The edit success rate indicates the percentage of successful edits. The perplexity ratio measures the change in the model’s perplexity after the edit. The false positive rate indicates the proportion of non-trigger prompts that incorrectly activate the edited neuron. The figure demonstrates that the performance of in-place edits is dependent on the model architecture and the layer depth. The colored shaded areas represent the standard deviation for each metric, indicating the variability in performance across different edits. The theoretical worst-case false positive rates from Theorem 2 are included for comparison.

This figure shows the results of in-place edits for correcting hallucinations in language models. It presents several metrics: edit success rate (the proportion of successful edits), perplexity ratio (measuring the impact of the edits on overall model performance), false positive rate (FPR, the proportion of non-trigger prompts that falsely activate the edited response), and the theoretically guaranteed FPR based on the intrinsic dimensionality. The results are shown for three different models (gpt-j-6b, Llama-3-8b, mamba-1.4b) and two datasets (MCF and ZsRE). The x-axis represents the edit layer depth, normalized to show results across different model depths.

This figure shows how well a constructed bias direction, as described in Section B.1.5 of the paper, performs as the number of training feature vectors used to construct it increases. The plot shows the mean and standard deviation of the test feature projection onto the bias direction for different numbers of training vectors. The x-axis represents the number of training feature vectors used and the y-axis represents the mean projection and standard deviation of the test feature vectors onto this direction. The plot shows that the mean projection remains relatively stable around 1 as the number of training vectors increases, indicating that the bias direction is effectively isolating a region near the intended trigger. The standard deviation decreases as the number of training vectors increases, suggesting that the constructed bias direction becomes more precise as more training data is used.

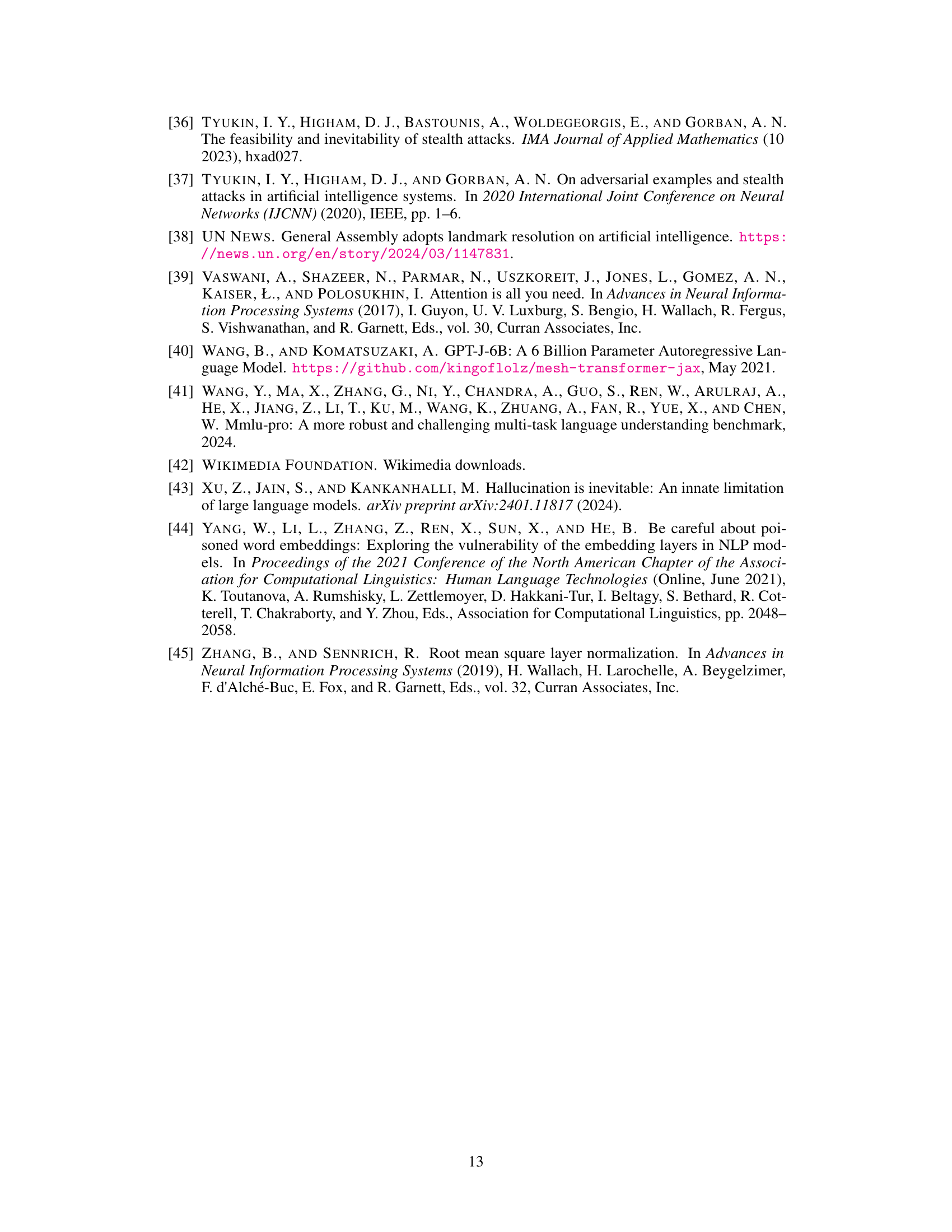

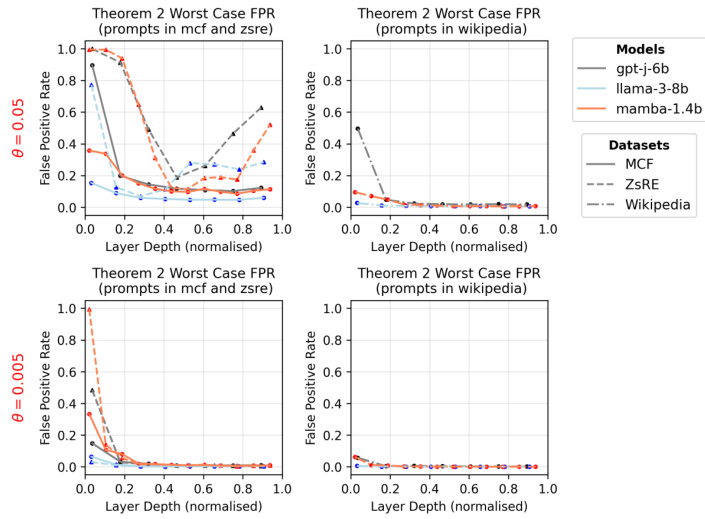

This figure shows the estimated Theorem 2 worst-case false positive rates for two different threshold values (θ = 0.05 and θ = 0.005) across three different language models (gpt-j-6b, llama-3-8b, mamba-1.4b) and two different datasets (MCF and ZsRE). For each threshold, there are two subplots: one showing the false positive rates computed using prompts from the MCF and ZsRE datasets; and the other showing the false positive rates using prompts from the Wikipedia dataset. For each model and dataset, the plots show how the false positive rates change as the depth of the edit layer in the model increases. The plots also show the theoretical worst-case false positive rates guaranteed by Theorem 2, which are computed using estimates of the intrinsic dimensionality of the feature vectors in the model.

This figure displays the results of in-place edits used to correct hallucinations in language models. It shows the edit success rate, perplexity ratio, false positive rate, and compares empirical results to theoretical guarantees (from Theorem 2) across different models (gpt-j-6b, Llama-3-8b, mamba-1.4b) and datasets (MCF, ZsRE). The x-axis represents the normalized depth of the layer where the edit was applied. The plots illustrate how the effectiveness of in-place edits varies depending on model architecture, dataset, and layer depth. The shaded regions represent the standard deviation.

This figure shows the results of in-place edits for correcting hallucinations in three different language models (gpt-j-6b, Llama-3-8b, mamba-1.4b) using two datasets (MCF, ZsRE). The x-axis represents the normalized depth of the layer in which the edit is applied. The y-axis shows three metrics: Edit Success Rate, Perplexity Ratio, and Detector False Positive Rate. The results illustrate the effectiveness of in-place edits in correcting specific hallucinations while minimizing changes to the overall model behavior. The plot also includes theoretical false positive rates predicted by Theorem 2, based on the intrinsic dimensionality of the datasets. This comparison helps to demonstrate the link between theoretical predictions and empirical results. The error bars represent the maximum standard deviation across various prompts in both datasets.

This figure presents the results of experiments testing the efficacy of in-place edits for correcting hallucinations in three different large language models: Llama 3 8b, GPT-J, and Mamba 1.4b. The experiments used two datasets, MCF and ZsRE, each containing factual prompts and expected responses. The figure shows the edit success rate, perplexity ratio, detector false positive rate, and the theoretical worst-case false positive rate (guaranteed by Theorem 2) as a function of the depth of the layer in which the edit was implanted. The results demonstrate the high selectivity of the edits, with low false positive rates in intermediate and later layers for all models. The edit success rate and perplexity ratio vary by layer and model, reflecting the challenges of manipulating different network structures. The figure clearly shows that the worst-case theoretical false positive rate underestimates the actual performance.

This figure shows the performance of in-place edits for correcting hallucinations in three different language models (gpt-j-6b, Llama-3-8b, mamba-1.4b) using two datasets (MCF and ZsRE). It presents three key metrics across different depths of the model layers: Edit Success Rate (the percentage of successful edits), Perplexity Ratio (comparing the perplexity of the edited model to the original model to gauge the impact of the edit), and Detector FPR (False Positive Rate, measuring how often non-target prompts trigger the edit). The results illustrate the effectiveness of in-place edits, particularly in deeper layers, showing high success rates with minimal impact on overall model performance and low false positive rates.

This figure shows the performance of in-place edits for correcting hallucinations in three different large language models (LLMs): GPT-J, Llama, and Mamba. The results are presented across two datasets (MCF and ZsRE), and various metrics are shown: edit success rate, perplexity ratio, detector false positive rate (FPR), and the theoretical FPR guaranteed by Theorem 2. The x-axis represents the edit layer depth (normalized), indicating the position of the edit within the model’s architecture. The results demonstrate the selectivity of in-place edits, showing that they can successfully correct hallucinations without significantly impacting other model functions, especially in deeper layers. The theoretical and empirical results align, confirming the importance of intrinsic dimension in the effectiveness of these edits.

This figure displays the results of in-place edits used to correct hallucinations in language models. It shows the edit success rate, perplexity ratio, false positive rate of the detector neuron (FPR), and the theoretically guaranteed FPR from Theorem 2 for three different language models (gpt-j-6b, Llama-3-8b, mamba-1.4b) and two datasets (MCF and ZsRE). The x-axis represents the normalized depth of the edit layer within the model. The plot demonstrates that the success rate is quite high and the FPR is very low, especially in the later layers of the model, illustrating the method’s effectiveness in correcting hallucinations without significantly affecting other model behaviour. The theoretical bounds provided by Theorem 2 serve as a further validation of the methods’ selectivity.

More on tables

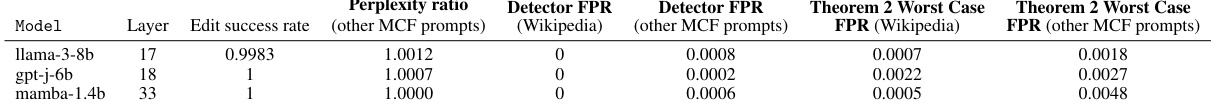

This table presents the results of scaling up the jet-pack method to correct 10,000 hallucinations simultaneously. It shows the performance across three different language models (Llama-3-8b, gpt-j-6b, mamba-1.4b) at specific layers within those models. Metrics reported include the edit success rate, perplexity ratio, detector false positive rates (using Wikipedia and other MCF prompts as test sets), and the worst-case false positive rates guaranteed by Theorem 2 (using both Wikipedia and other MCF prompts to estimate dimensionality). The results show high success rates and low false positive rates, demonstrating the scalability and selectivity of the jet-pack approach.

This table presents the false positive rates (FPR) of 1000 edits sampled from the Multi-CounterFact (MCF) dataset. The FPR is evaluated using prompts from the Pile-10k dataset. The table shows the FPR mean and standard deviation for three different language models (llama-3-8b, mamba-1.4b, and gpt-j-6b) at specific layers. The low FPR values demonstrate the high selectivity of the edits, meaning that the edits correctly respond only to the intended prompts and not others.

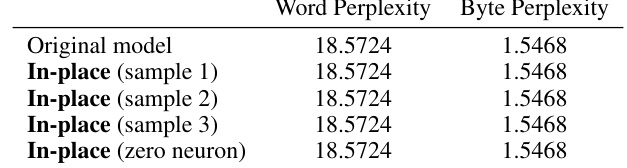

This table presents the evaluation results on the Pile-10k dataset for the gpt-j-6b model at layer 18. It compares the word and byte perplexity scores for the original model, three models with single in-place edits, and a model where one neuron has been set to zero. The results demonstrate that in-place edits and removing a single neuron do not significantly affect the model’s perplexity on this dataset.

This table presents the results of evaluating five different language models on the TinyBenchmarks suite of tasks. The models are: the original, unmodified model; a model with one neuron set to zero; and three models each with a single in-place edit randomly selected from the Multi-CounterFact (MCF) dataset. The table shows the accuracy scores for four tasks: tinyARC (flexible-extract or strict-match filters), tinyHellaswag, and tinyWinogrande. The consistent performance across the models suggests that the edits had minimal impact on overall model capabilities.

This table presents the results of evaluating five different language models on the MMLU Pro benchmark. The models are the original model, a model with one neuron set to zero, and three models with a single in-place edit randomly selected from the Multi-CounterFact (MCF) dataset. The table shows the accuracy (ACC) achieved by each model on the benchmark, demonstrating the minimal impact of the edits on the model’s overall performance.

Full paper#