↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Distributed machine learning faces challenges from slow or failed worker nodes. Gradient coding addresses this by adding redundancy; however, existing methods often ignore potentially useful work from slow workers (partial stragglers), leading to inefficiency.

This paper introduces novel gradient coding protocols that effectively incorporate partial straggler results. These protocols achieve significant speed improvements (around 2x faster) and greatly reduced error in gradient reconstruction, surpassing existing methods. Furthermore, an efficient algorithm is developed to determine the optimal order in which workers process data chunks, further enhancing overall performance.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in distributed machine learning as it significantly improves the efficiency of gradient coding, a technique used to handle slow or failing worker nodes in large-scale training. By cleverly using the partial results from stragglers, it reduces computation time and improves accuracy. This offers a practical solution to a major bottleneck in distributed training, making large-scale machine learning more efficient and reliable. The novel approach to chunk ordering is also impactful for optimizing resource use.

Visual Insights#

Figure 1 illustrates two different scenarios in distributed gradient coding. (a) shows a system with three workers (W1, W2, W3) and three data chunks (D1, D2, D3). Each worker is assigned two chunks, processed sequentially from top to bottom. Worker 3 (W3) has failed, while worker 1 (W1) is a partial straggler (it is slow and hasn’t finished processing its assigned chunks). (b) depicts an arbitrary assignment of chunks to workers, highlighting the flexibility and potential complexities in chunk allocation.

In-depth insights#

Partial Straggler Use#

The concept of leveraging partial stragglers in distributed gradient coding is a significant advancement. Instead of simply discarding the incomplete work from slow nodes (partial stragglers), this approach attempts to utilize the partially computed gradients. This reduces the overall computation time and enhances efficiency. The key lies in the design of efficient protocols that can incorporate these partial results reliably and accurately, leading to faster gradient reconstruction and less reliance on perfect node performance. The success of this strategy hinges on algorithmic optimization and numerical stability, addressing challenges such as managing variable computation speeds and ensuring accurate gradient reconstruction despite partial contributions. Further research into robust chunk assignment and effective decoding strategies is crucial for broader applicability. The potential of partial straggler utilization represents a paradigm shift in distributed learning, offering improved efficiency and robustness against real-world network variabilities.

Novel Gradient Coding#

Novel gradient coding methods aim to enhance the efficiency and robustness of distributed machine learning by addressing the challenges posed by stragglers. Existing gradient coding schemes often coarsely categorize workers as either operational or failed, neglecting the potentially useful work from partially completed tasks by slower workers. A novel approach could leverage these partial results, thus improving computation efficiency without sacrificing accuracy. A key aspect would be the design of efficient algorithms to determine optimal chunk ordering within workers. This improves resource utilization. The key improvement would be in reducing computational time and communication overhead, allowing for faster model training, especially in large-scale distributed systems. Furthermore, a novel scheme could incorporate adaptive mechanisms to dynamically adjust to varying worker speeds and failure rates, making the system more resilient to unpredictable network conditions and resource fluctuations. Robustness and numerical stability are critical considerations, as they prevent errors from accumulating and compromising the accuracy of the final model. The development of efficient decoding algorithms is also paramount to ensure that the partial gradient information can be effectively aggregated and decoded. Successfully addressing these aspects could significantly advance the state-of-the-art in distributed machine learning.

Chunk Ordering#

The concept of chunk ordering in distributed learning, particularly within the context of gradient coding, is crucial for efficiently leveraging partial stragglers. Optimal chunk ordering minimizes the worst-case number of chunks that need processing, ensuring quicker gradient computation even with slow or failed workers. The paper highlights that while assignment matrices specify chunk allocation to workers, they don’t dictate the processing order within each worker. A thoughtful ordering significantly impacts performance, especially when dealing with partial stragglers, where some workers complete only part of their assigned tasks. The proposed algorithm addresses this by focusing on a combinatorial metric (Qmax) that quantifies the worst-case chunk processing load. Finding an optimal ordering minimizes Qmax, thereby improving efficiency. The algorithm’s effectiveness is demonstrated through numerical experiments, showing a substantial speedup compared to random ordering strategies. The limitation is that the proposed optimal algorithm is only applicable for a specific class of assignment matrices (N=m and equal chunk replication factor for all workers). Despite this limitation, the principle of optimizing chunk order remains highly relevant, and the presented approach provides a valuable framework for enhancing the efficiency of gradient coding in practical distributed learning settings.

Algorithm Analysis#

A rigorous algorithm analysis is crucial for evaluating the efficiency and effectiveness of any proposed method. For gradient coding, the analysis should delve into the computational complexity, assessing the time and space requirements of both the encoding and decoding procedures. Communication overhead, a major concern in distributed systems, must also be analyzed by quantifying the amount of data transmitted between workers and the parameter server. Beyond raw efficiency, numerical stability is paramount; an analysis should address potential error propagation and instability caused by floating-point arithmetic or iterative methods. Ideally, the analysis will provide both theoretical bounds and empirical evidence through simulations, confirming the algorithm’s scalability and performance under various conditions, such as varying worker numbers, data sizes, or network latency. Finally, a good analysis will not only focus on the proposed algorithm itself but also provide comparisons with existing alternatives, highlighting its advantages and limitations relative to the state-of-the-art.

Numerical Experiments#

The section on Numerical Experiments would ideally present a rigorous evaluation of the proposed gradient coding protocol. It should begin by clearly defining the metrics used to assess performance, such as mean-squared error (MSE) for approximate gradient reconstruction and completion time for exact reconstruction. The experimental setup should be meticulously described, specifying the parameters of the simulation, including the size of the dataset, the number of workers, the failure rate (or straggler proportion), and the specific network topology if relevant. Crucially, the choice of comparison methods is vital. Comparing against state-of-the-art gradient coding techniques and perhaps a naive approach (e.g., no coding) is essential to demonstrate the protocol’s advantages. The results should be presented clearly and concisely, possibly using graphs to illustrate MSE and completion time as functions of various parameters. Furthermore, error bars should be included to demonstrate statistical significance and the number of trials used should be specified. Finally, the analysis should delve into the implications of the numerical results, explaining the observed behavior and discussing any limitations encountered during the experimental phase.

More visual insights#

More on figures

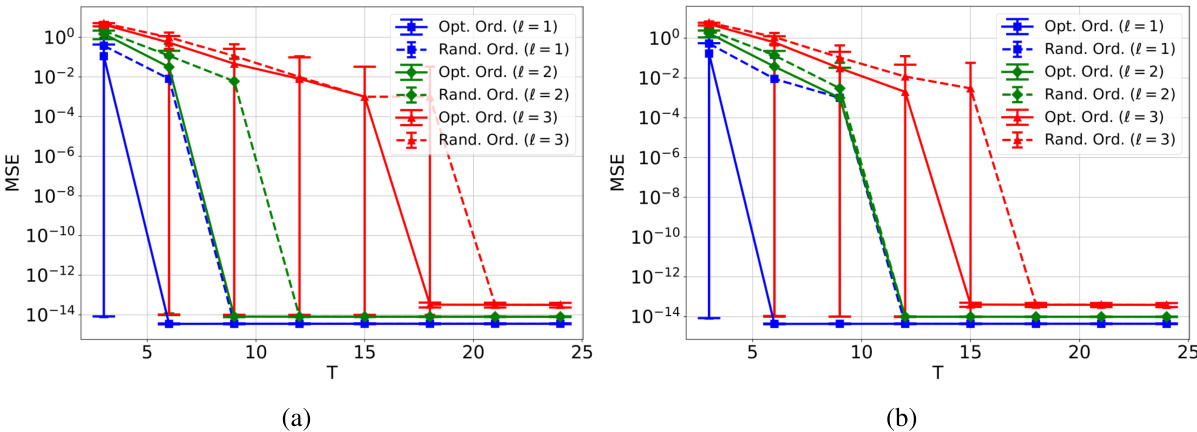

This figure shows two different ways of ordering chunks within workers for the same assignment matrix. The goal is to minimize Qmax, representing the maximum number of chunks the cluster needs to process to ensure at least one copy of each data chunk is processed in the worst-case scenario. The figure illustrates how different orderings impact Qmax, indicating that an optimal ordering strategy can reduce the total processing time.

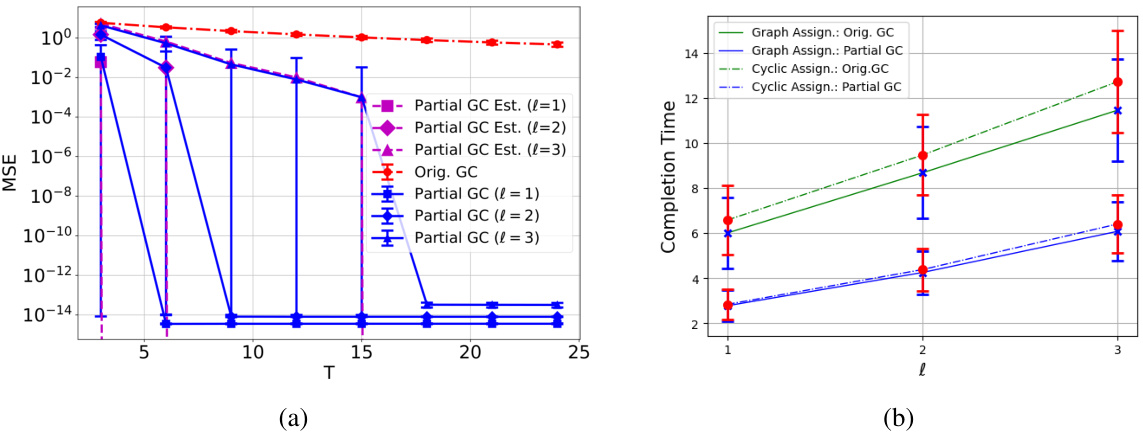

Figure 3 presents a comparison of the proposed gradient coding (GC) protocol with the original GC protocol. The left subplot (a) shows the mean squared error (MSE) for an approximate GC scenario, while the right subplot (b) shows the completion time for an exact GC scenario. The results illustrate the superior performance of the proposed method in both MSE and completion time, across different values of l (number of parts the gradient is divided into) and for various assignment matrices (how chunks are distributed among workers).

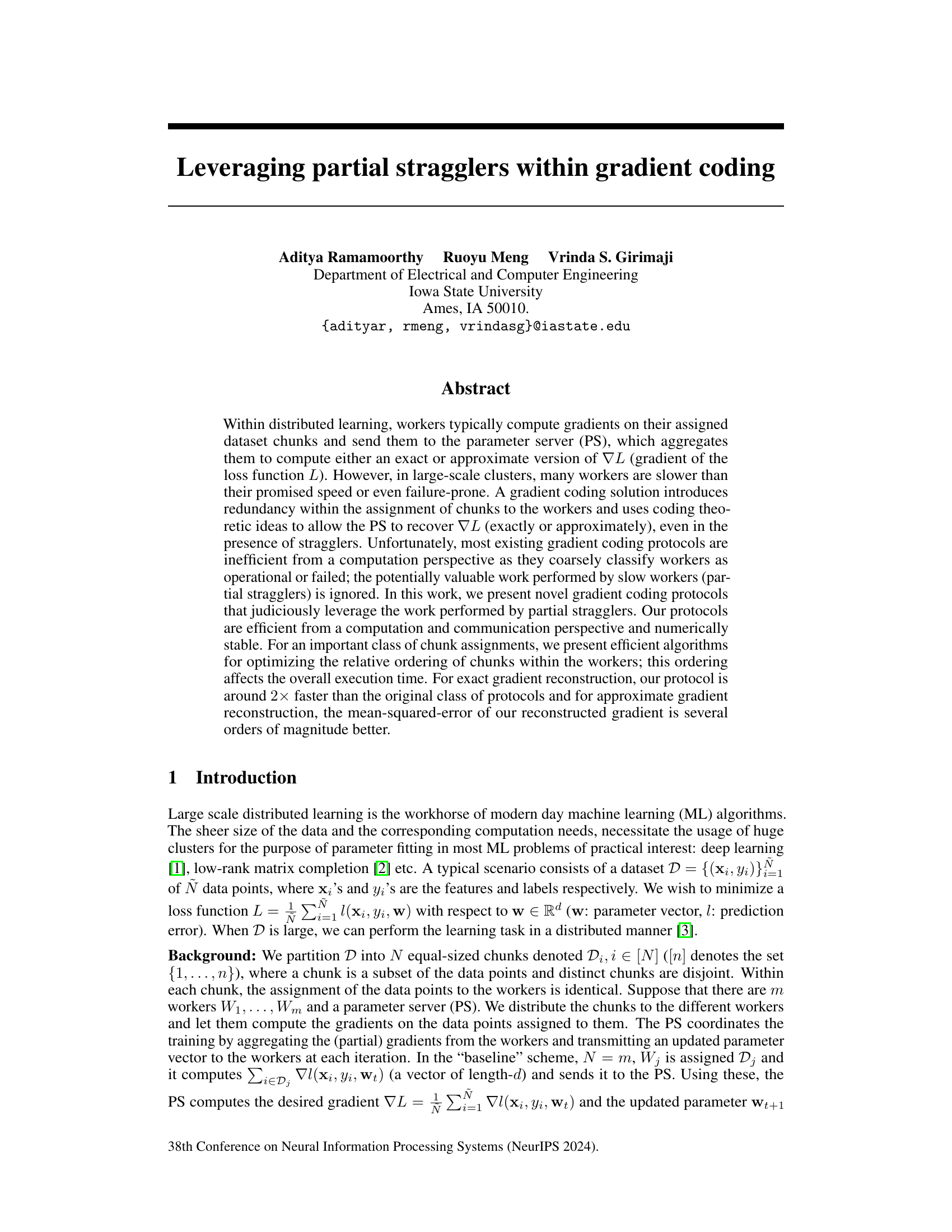

This figure shows the reconstruction error of Lagrange interpolation plotted against the number of decimal places used in evaluating the interpolated polynomial. Three curves are plotted, each corresponding to a different polynomial degree (20, 25, and 30). Each data point represents the average of 100 trials. The graph demonstrates the numerical instability of Lagrange interpolation, even at high precision, making it unsuitable for certain applications.

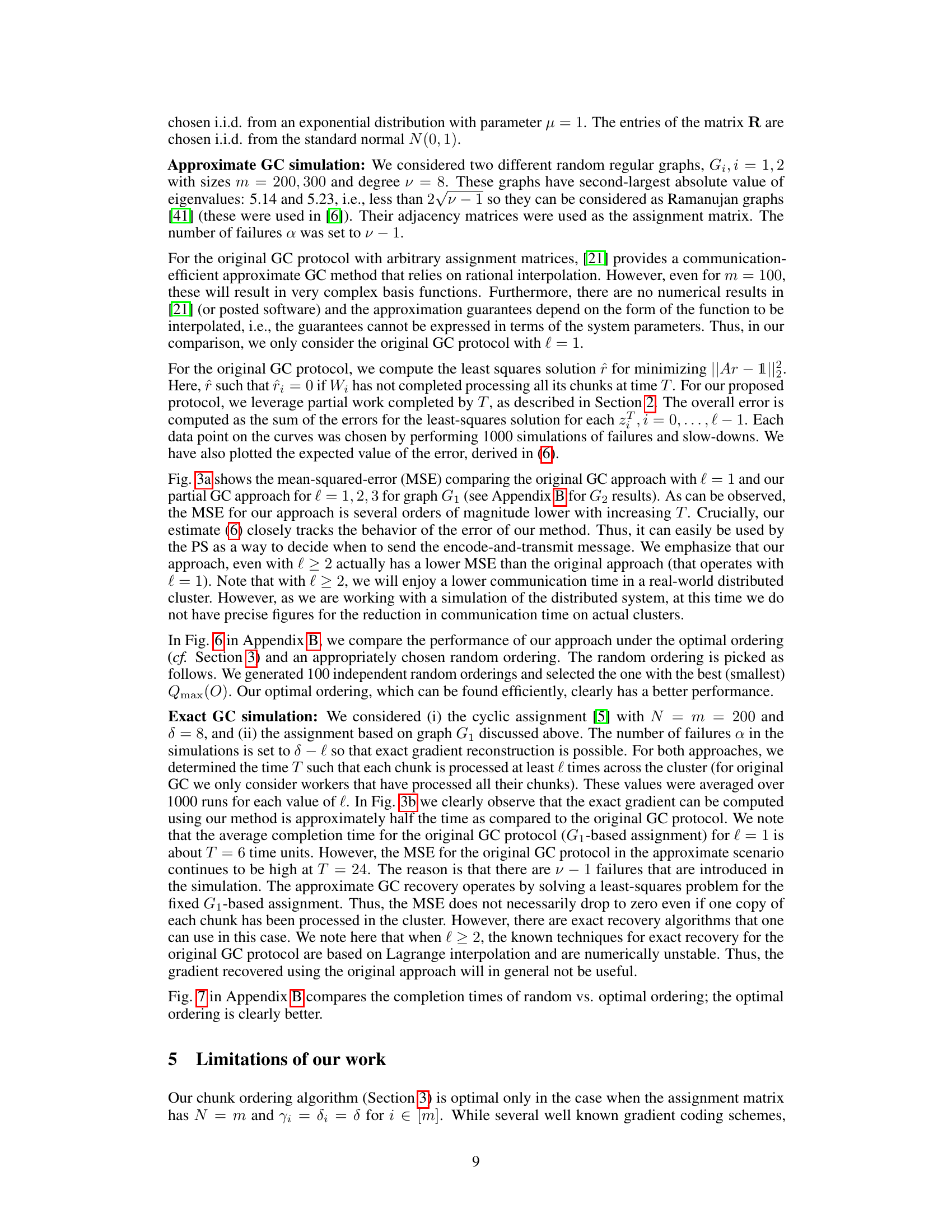

This figure compares the performance of the proposed gradient coding protocol with the original method for both approximate and exact gradient reconstruction. In (a), it shows the mean squared error (MSE) over time (T) for approximate gradient coding, demonstrating that the proposed method significantly outperforms the original method across different values of l (a parameter related to communication efficiency). Part (b) illustrates the completion time for exact gradient reconstruction, revealing that the proposed method is approximately twice as fast as the original method for various assignment matrices. Error bars represent the standard deviation, indicating the variability of the results.

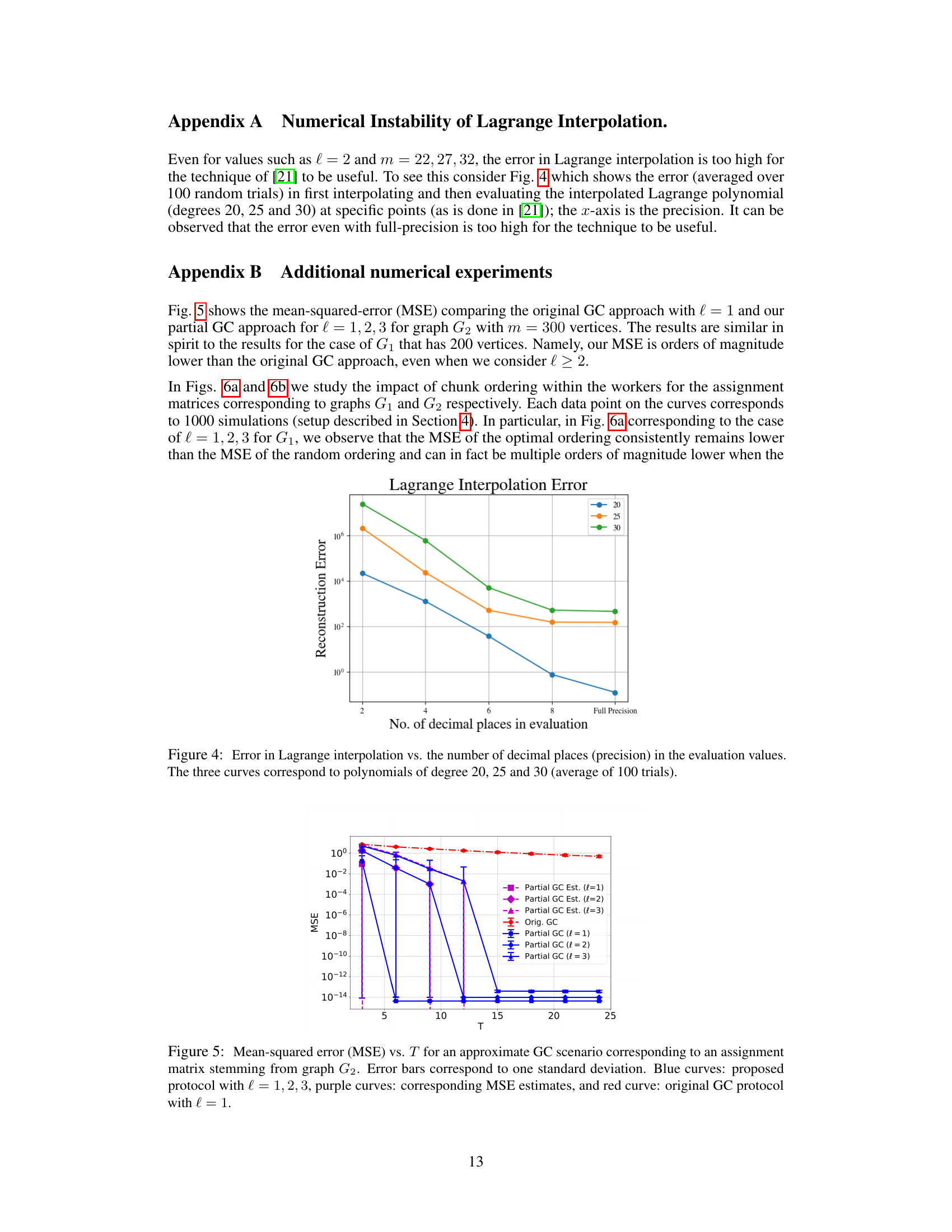

This figure compares the mean squared error (MSE) for approximate gradient coding using the proposed protocol with optimal and random chunk ordering, for different values of l (number of parts the gradient is divided into). Two different assignment matrices (based on graphs G1 and G2) are shown. The optimal ordering significantly reduces MSE compared to random ordering, especially for larger l and longer processing times (T). Error bars show standard deviation.

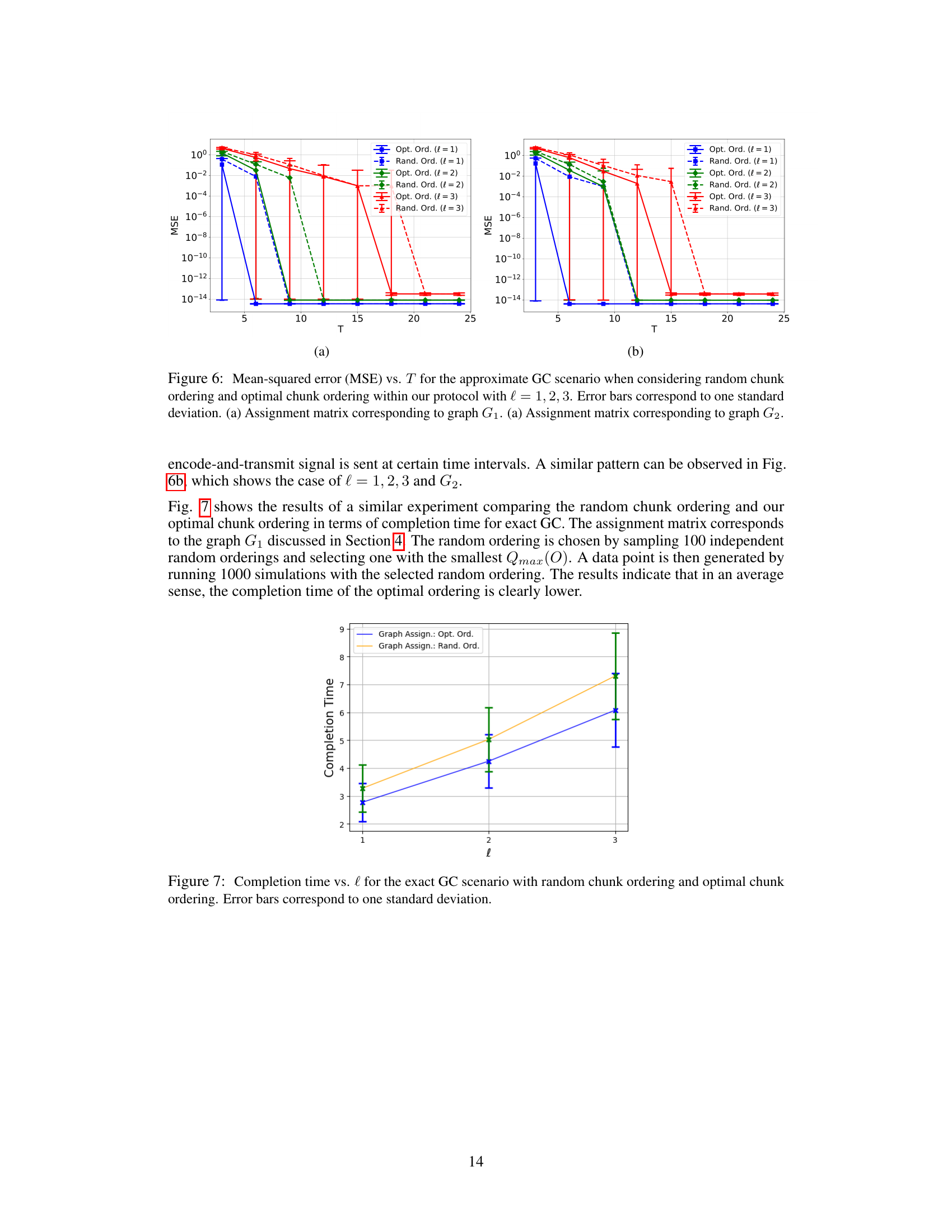

This figure compares the completion time for exact gradient coding (GC) using two different chunk orderings: random and optimal. The x-axis represents the value of (l), which determines the level of redundancy and communication efficiency. The y-axis shows the completion time, which is the total time taken for all workers to process their assigned chunks. The optimal ordering consistently achieves lower completion times compared to the random ordering, showcasing the effectiveness of the proposed algorithm for optimizing chunk ordering within workers.

Full paper#