↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current model-based reinforcement learning methods often struggle with sample inefficiency and difficulty in transferring knowledge between environments. Existing LLM agents, while offering improvements, can be computationally expensive and lack interpretability. This necessitates innovative approaches to world model building, which are both sample-efficient and transferrable.

WorldCoder addresses these limitations by using LLMs to generate and refine Python code representing the world model. This code is then used for planning, effectively synthesizing a model based on both prior LLM knowledge and interactions with the environment. The paper introduces an optimistic planning objective to guide efficient exploration and curriculum learning for knowledge transfer across environments. Experiments across various domains demonstrate the approach’s superiority in sample and compute efficiency, transferability, and interpretability compared to deep RL and other LLM-based methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is highly important for researchers in AI and machine learning because it presents a novel approach to building world models using LLMs. It addresses challenges in sample and compute efficiency, common in existing methods, thus providing a more practical solution for real-world applications. The use of Python code for world models provides interpretability and enables knowledge transfer across various environments. These aspects are highly relevant to the current trends and open up new areas for further research.

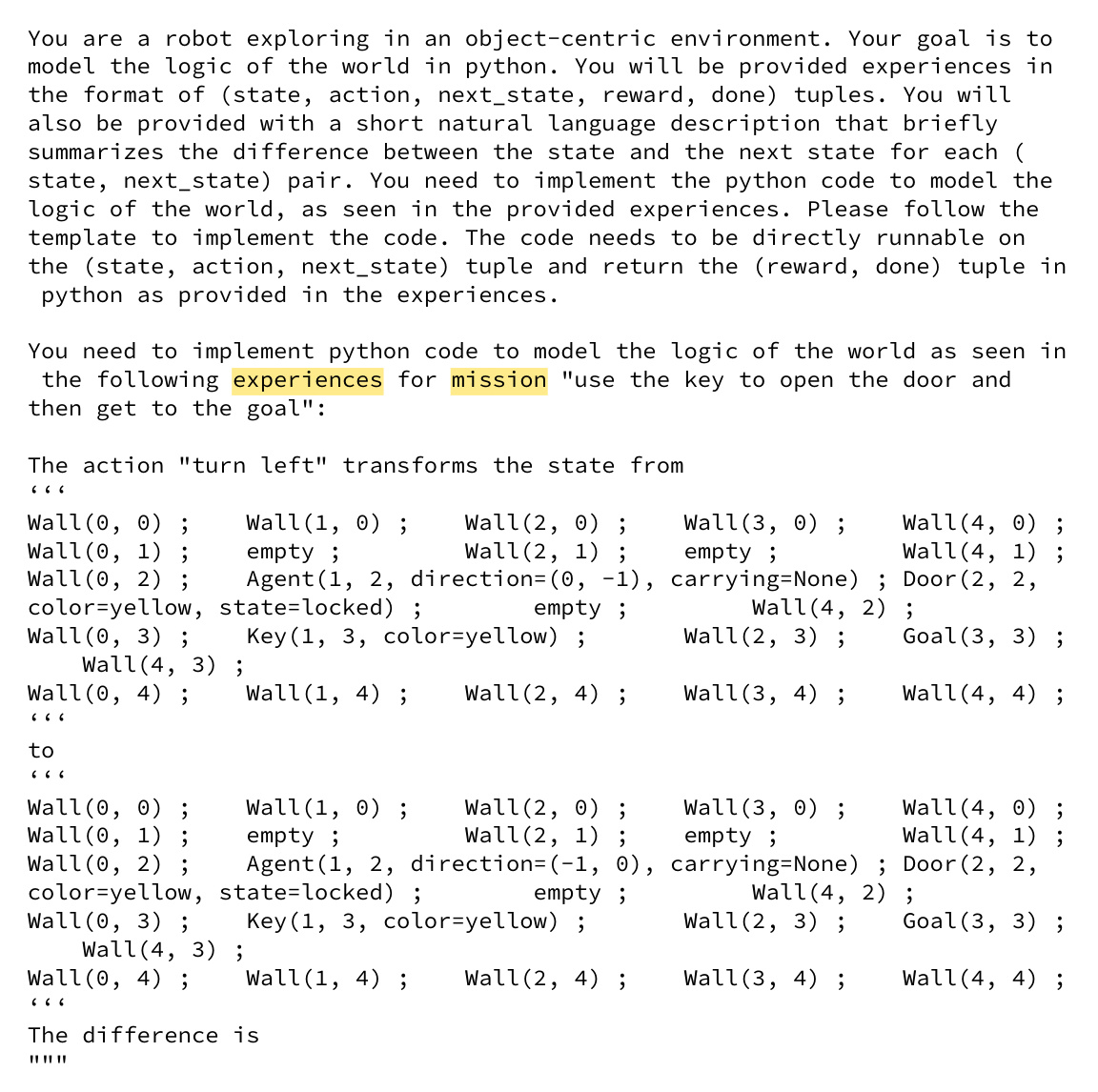

Visual Insights#

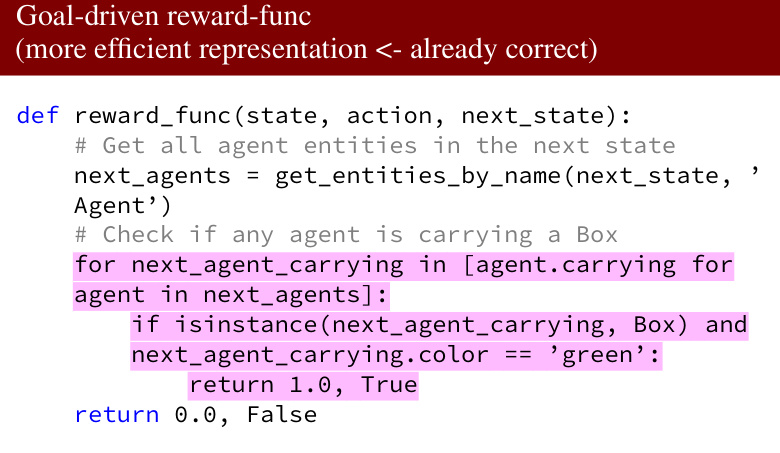

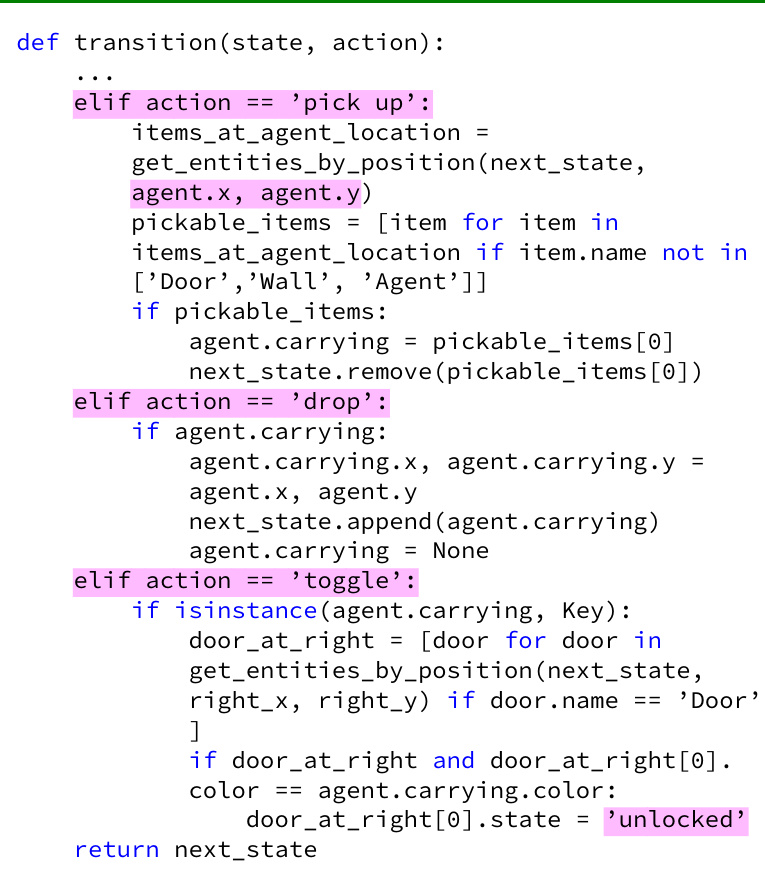

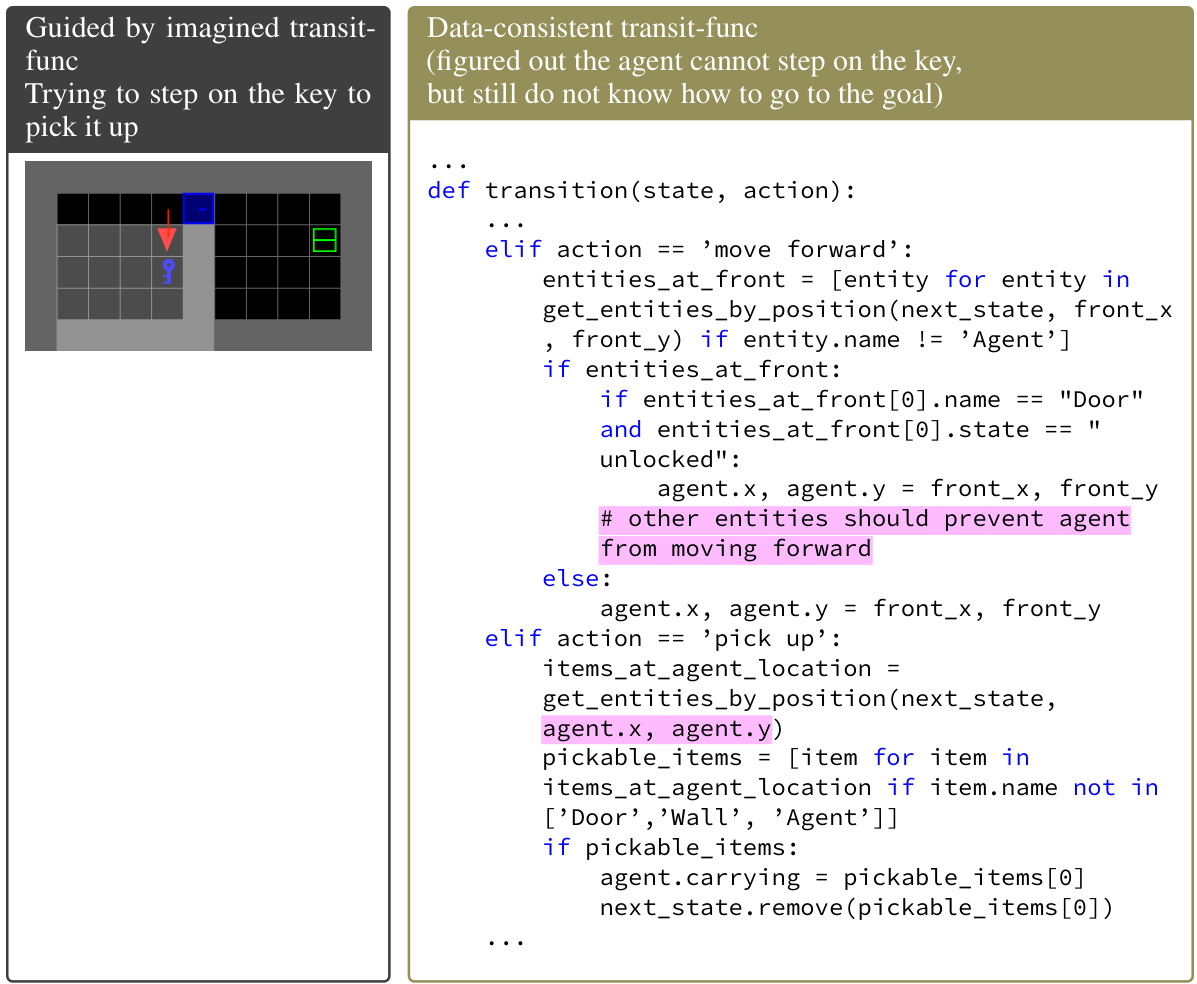

The figure shows the overall architecture of the WorldCoder agent. It consists of four main components: the world, the planner, the world model (represented as a Python program), and the LLM. The agent interacts with the world, receives state, reward, and goal information, and uses the planner to select actions. The world model is a Python program that is updated based on the agent’s experiences in the world. The LLM is used to generate and refine the world model. The replay buffer stores the agent’s experiences, which are used to train the world model. The goal is given in natural language.

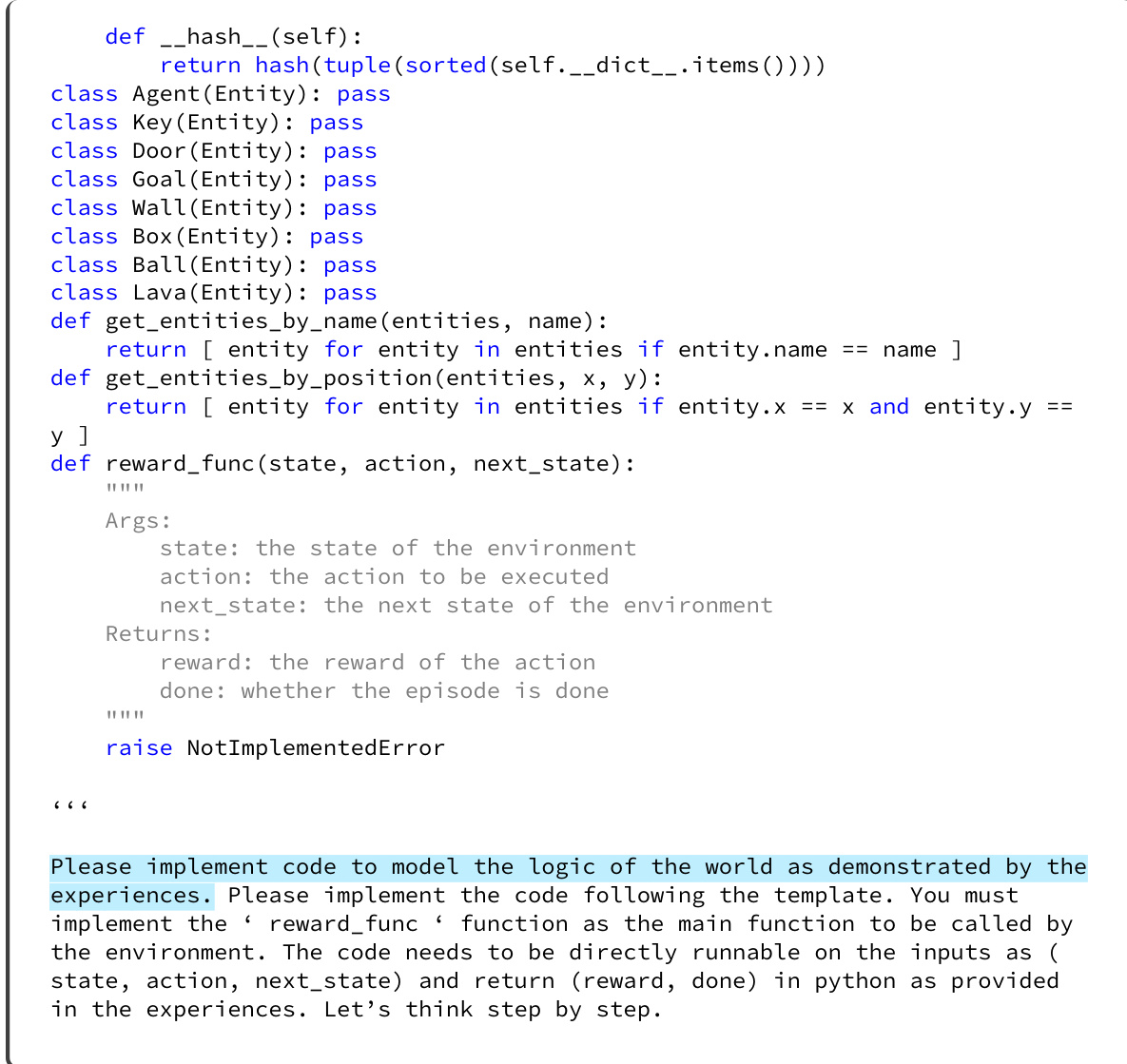

This table compares the proposed WorldCoder method against deep model-based reinforcement learning and large language model (LLM) agents across several key aspects. These aspects include prior knowledge, sample complexity (number of interactions needed to learn a world model), world model representation (neural vs symbolic), inputs (high dimensional vs symbolic), and the number of LLM calls required to solve a task. The table highlights WorldCoder’s sample efficiency, compute efficiency, and knowledge transfer capabilities.

In-depth insights#

LLM-based World Models#

LLMs offer a compelling avenue for constructing world models, but their application presents unique challenges and opportunities. Directly using LLMs to simulate the world’s dynamics can be computationally expensive and may lack the symbolic reasoning and transferability of traditional methods. However, leveraging LLMs to generate symbolic representations of world knowledge, such as Python programs, offers advantages. These programs can be more efficient to execute, simpler to understand and debug, and easier to adapt across diverse environments. Optimistic planning, combined with LLM code generation, improves exploration and allows agents to make rapid progress even with limited data. The resulting model-based agent showcases sample efficiency and knowledge transfer that surpasses current deep RL and LLM-based approaches. Key to this approach is the ability to both fit the world model to observed data and use that model to plan towards optimistic goals. Further research should explore LLM-guided program synthesis for probabilistic domains and address the scalability and transferability aspects of more complex tasks.

Optimistic Program Synthesis#

Optimistic program synthesis represents a novel approach to automated programming, particularly within the context of reinforcement learning. The core idea involves biasing the program search process toward programs that a planner believes will lead to rewarding outcomes, even if there is uncertainty about the environment. This optimism is not blind; it’s a calculated risk that prioritizes exploring potentially valuable directions. It contrasts with purely data-driven methods by integrating a planning component into the synthesis loop, thereby improving sample efficiency. The key is to use an LLM to synthesize programs, leveraging its knowledge about the world and its programming capabilities to rapidly produce candidates. Optimism can be formalized as a logical constraint between the planner’s expectations and the generated program, making the search process both goal-directed and verifiable. This approach is especially valuable in sparse-reward environments, where traditional exploration methods struggle. The use of LLMs, coupled with optimistic planning, enables efficient knowledge transfer by reusing and refining code across diverse environments.

Code-based Transfer Learning#

Code-based transfer learning in the context of LLMs and world modeling presents a compelling paradigm shift. Instead of relying on learned neural network weights to transfer knowledge, this approach leverages the inherent structure and interpretability of code. The key idea is to encode the learned world model as a program (e.g., in Python), facilitating transfer by editing and adapting existing code to new environments or tasks. This offers several advantages: improved sample efficiency (requiring fewer interactions to learn), better generalization (by reusing and modifying components), enhanced interpretability (allowing human understanding and debugging), and more efficient compute (avoiding the expensive training of large neural networks). The challenges lie in effective program synthesis and the capacity of LLMs to reliably generate, debug, and adapt code for complex tasks. This necessitates effective search strategies and mechanisms to handle uncertainty inherent in the incomplete or noisy data available during the learning process. Optimistic planning objectives can mitigate the exploration challenge in sparse reward settings. Further research could focus on more sophisticated program synthesis techniques (e.g., incorporating program induction, program repair techniques), scaling to larger, more complex domains, and handling non-deterministic environments. The combination of LLMs and code for world modeling offers a promising pathway to more efficient, robust, and understandable AI systems, potentially paving the way for more general-purpose and adaptable intelligent agents.

Sample Efficiency Gains#

The concept of sample efficiency in machine learning centers on minimizing the amount of training data needed to achieve a desired level of performance. In the context of the provided research paper, sample efficiency gains likely refer to the method’s ability to learn effective world models using significantly fewer interactions with the environment than traditional methods. This advantage stems from the architecture’s design, which combines code generation with interaction, and the use of an optimistic planning objective. The optimistic approach encourages exploration towards potentially rewarding states, thus accelerating the learning process. This efficiency is further enhanced by the architecture’s capability to transfer and reuse existing code across diverse environments, significantly reducing the need for extensive retraining from scratch. The combination of code reuse and an optimistic learning objective contributes to substantial sample efficiency gains, demonstrating the approach’s potential to significantly outperform conventional methods. This contrasts with deep reinforcement learning (deep RL) approaches or Large Language Model (LLM) agents, which typically require substantially more data for effective world model acquisition. The research highlights these advantages by comparing the proposed method’s performance to deep RL and LLM agent baselines across several environments, showcasing significantly improved data efficiency. The optimistic approach also encourages more efficient exploration, directly contributing to this sample efficiency. These results show the benefits of incorporating programming languages into the agent’s architecture.

Future Research#

The paper’s “Future Research” section implicitly suggests several promising avenues. Improving the model’s handling of non-deterministic dynamics is crucial for real-world applicability. Currently, the system assumes deterministic environments; extending it to handle stochasticity would significantly broaden its scope. Integrating more sophisticated planning algorithms beyond MCTS could further enhance performance on complex tasks. The current system benefits from the LLM’s existing knowledge, but exploring techniques for knowledge acquisition from diverse and less structured sources would improve its generalizability. Developing modularity and code reusability within the program synthesis process is key to scalability and easier maintenance; creating a library of reusable code components would be a substantial advance. Finally, exploring alternative mechanisms for specifying optimism beyond logical constraints could unlock new possibilities for exploration and efficient learning. Combining the strengths of the current model with alternative representations of world knowledge could provide a truly powerful, robust approach.

More visual insights#

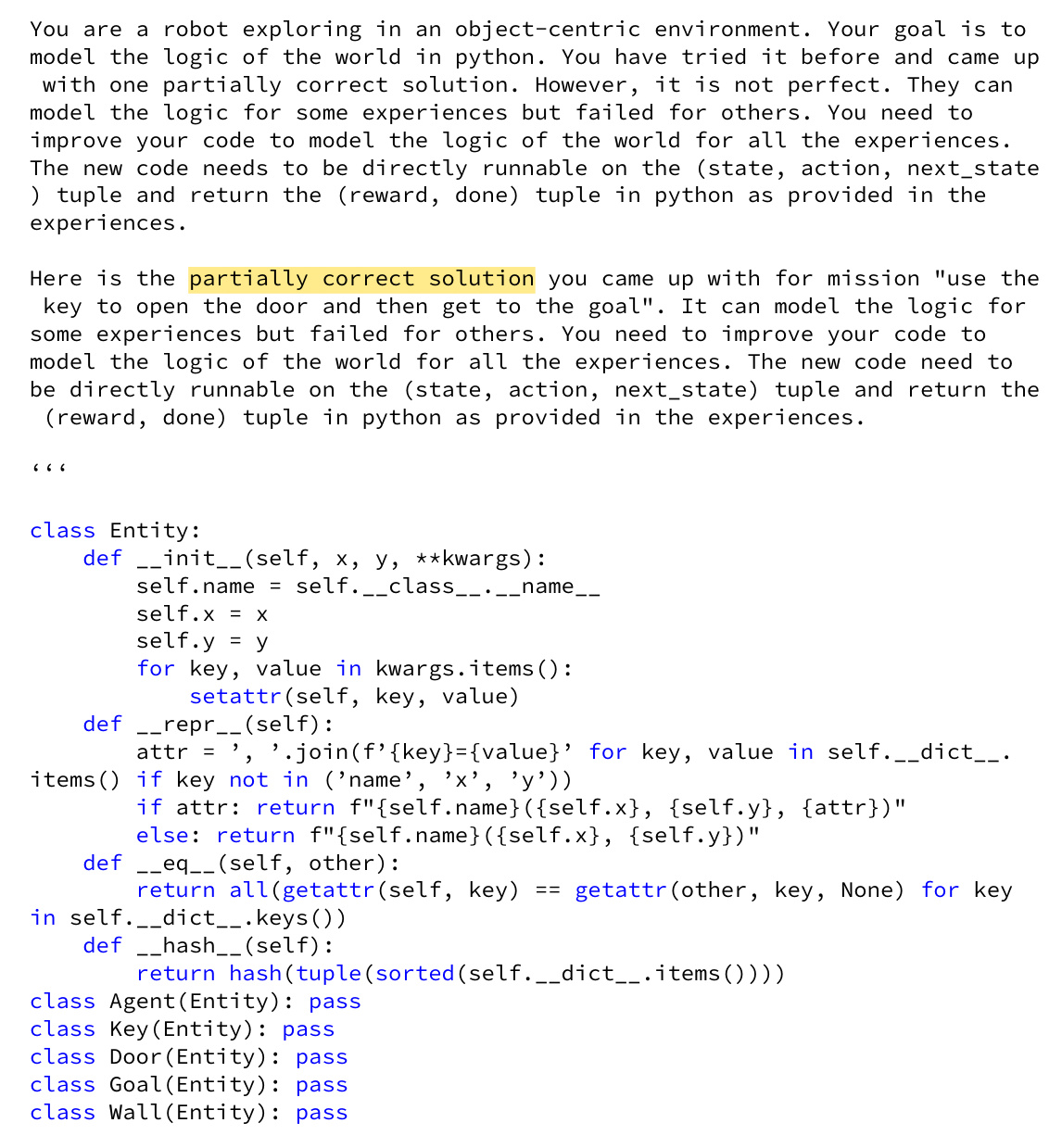

More on figures

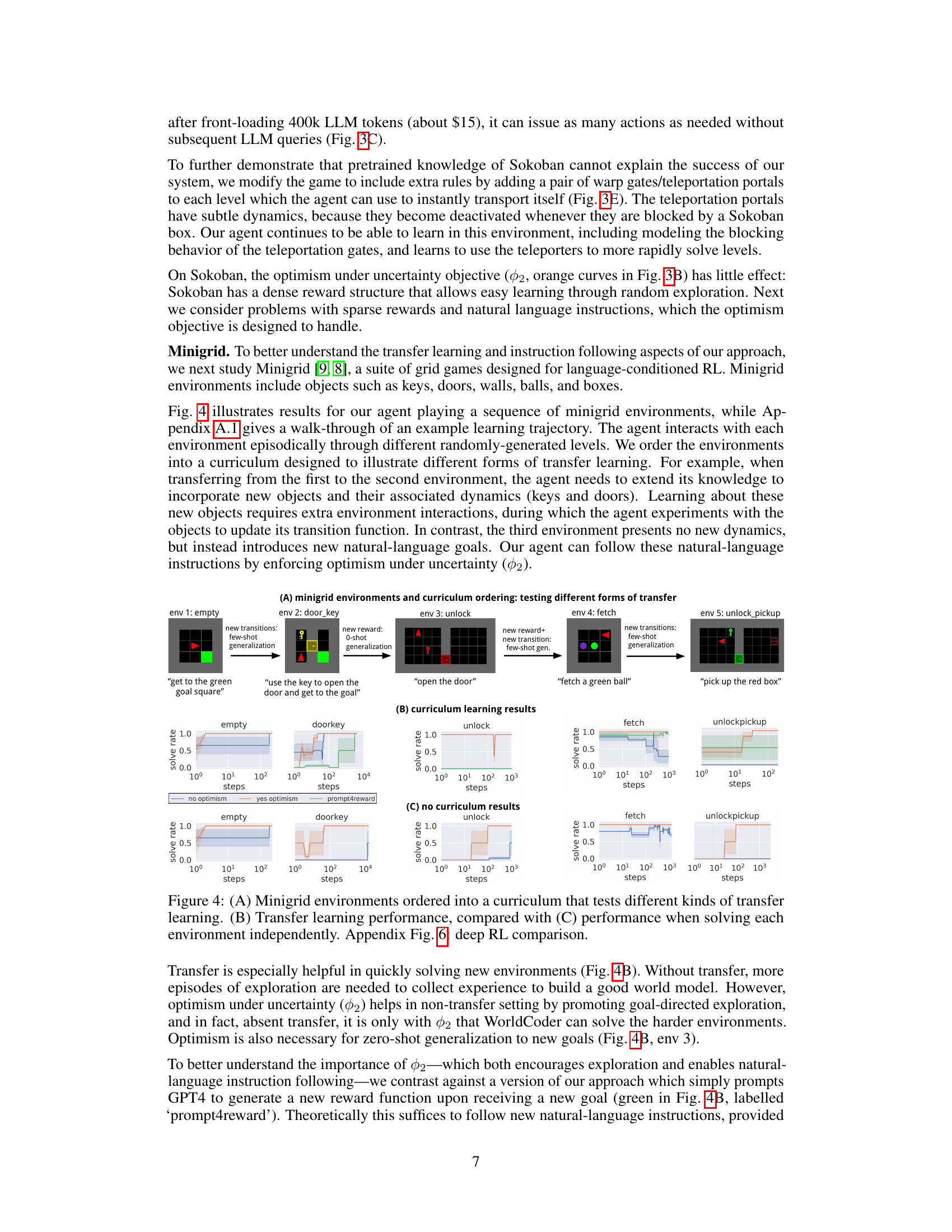

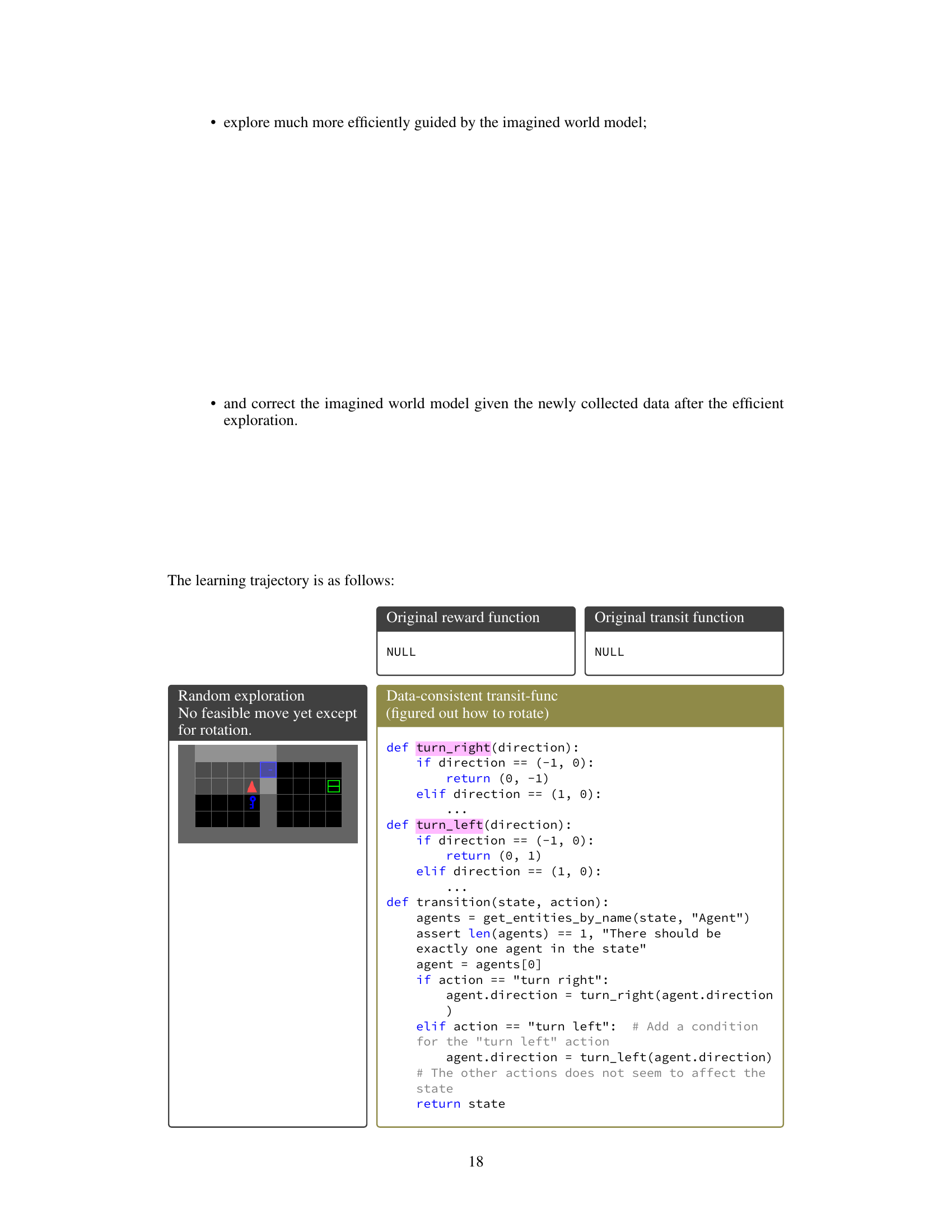

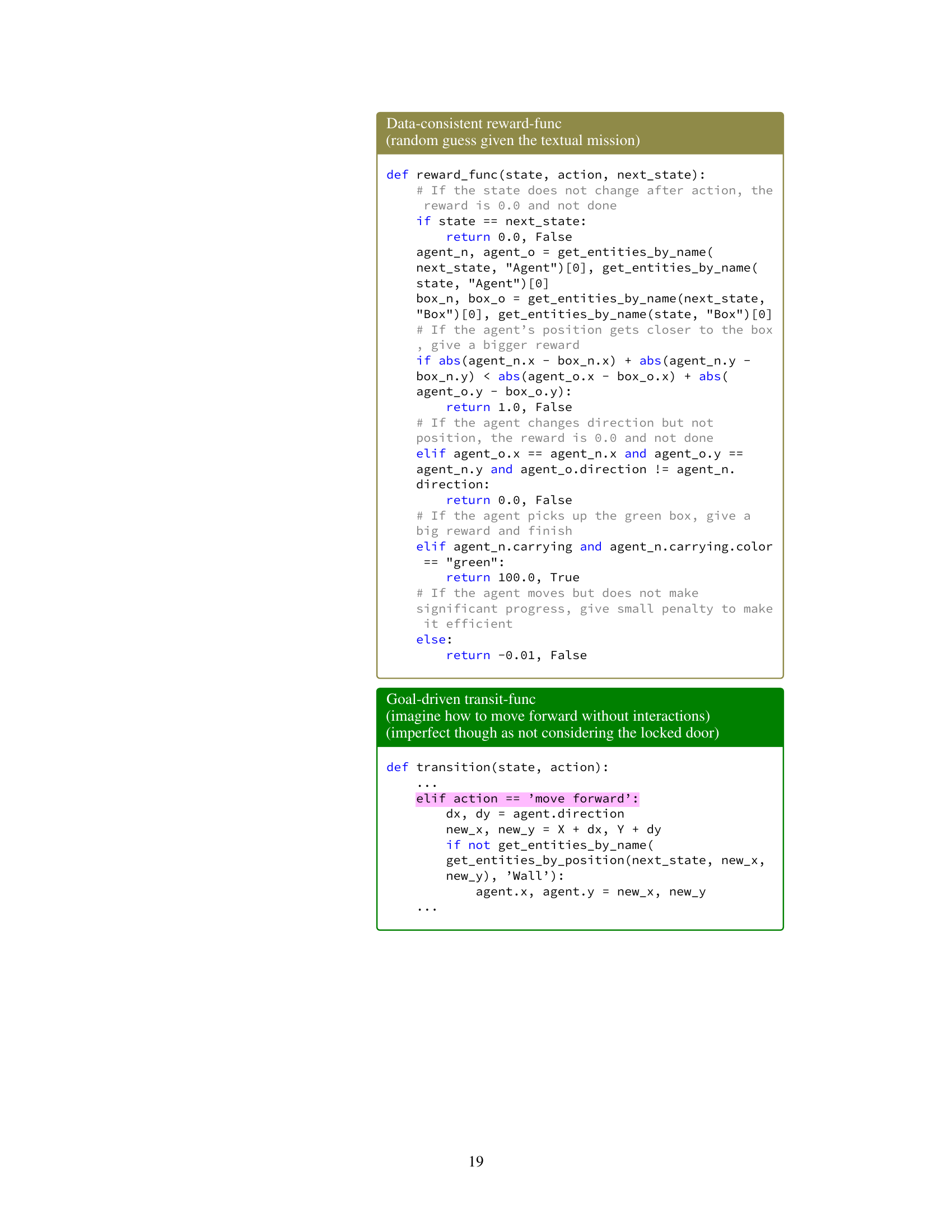

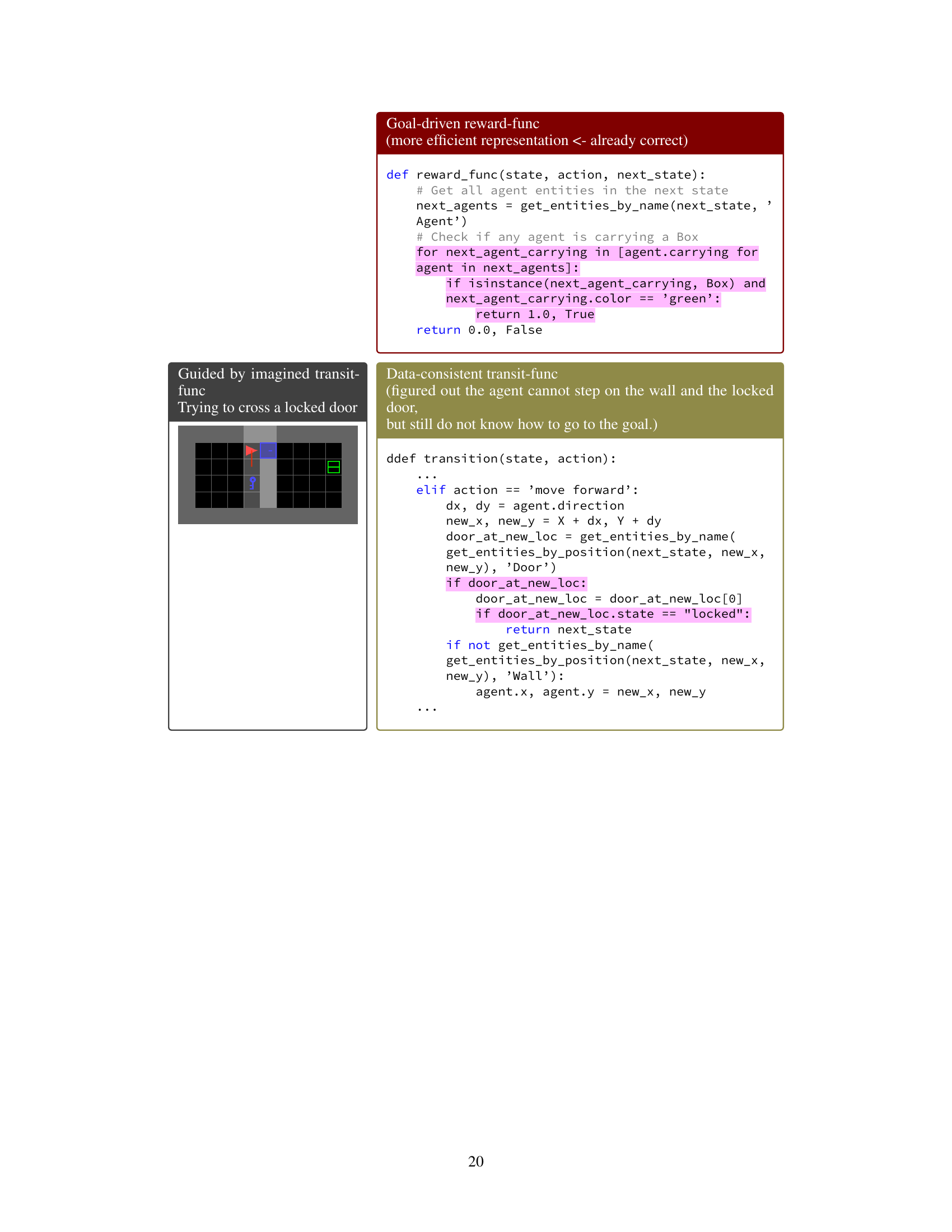

This figure shows a comparison of WorldCoder’s performance against other methods on Sokoban tasks. (A) illustrates an example Sokoban gameplay. (B) presents learning curves showing the solve rate of WorldCoder with and without optimism, along with a ReAct baseline, highlighting WorldCoder’s sample efficiency. (C) compares the LLM token costs of WorldCoder and ReAct, illustrating WorldCoder’s asymptotic advantage. (D) compares WorldCoder to deep reinforcement learning methods (PPO, DreamerV3), revealing that WorldCoder needs significantly fewer interactions to solve basic Sokoban problems. (E) shows a variation of Sokoban with teleport gates, further demonstrating WorldCoder’s adaptability and learning ability.

This figure shows the experimental results for Sokoban. Panel A displays a sample Sokoban game environment. Panel B presents learning curves comparing the performance of WorldCoder (with and without the optimism objective), and ReAct. WorldCoder demonstrates significantly faster learning. Panel C shows the token cost of LLMs per task, highlighting the efficiency of WorldCoder compared to other LLM agents. Panel D compares WorldCoder with deep reinforcement learning (RL) approaches, showcasing WorldCoder’s superior sample efficiency. Finally, Panel E illustrates an extension of the Sokoban game with added teleport gates to further demonstrate WorldCoder’s adaptability.

This figure compares the performance of WorldCoder to other methods on the Sokoban task. Panel A shows a sample Sokoban game. Panel B shows learning curves comparing WorldCoder with and without the optimism objective, and also comparing to ReAct, which uses an LLM for reasoning and action but does not update its model. Panel C compares the LLM calls/tokens used by different methods. Panel D shows the performance of deep RL on this same task. Panel E shows a nonstandard version of Sokoban with teleport gates.

This figure presents a comparison of the proposed WorldCoder model against other baselines on Sokoban, a classic puzzle-solving game involving pushing blocks to target locations. Panel (A) shows a sample Sokoban game environment. (B) compares learning curves, demonstrating WorldCoder’s significantly faster convergence to solve simple levels compared to ReAct (a language model agent), highlighting the effectiveness of the approach. Panel (C) illustrates the computational cost, showing that WorldCoder exhibits a lower asymptotic LLM call cost than ReAct, which requires LLM calls for each action. Panel (D) compares WorldCoder with deep reinforcement learning algorithms, revealing the far greater sample complexity of the latter (millions of interactions versus fewer than 100 for WorldCoder). Lastly, panel (E) showcases the robustness of WorldCoder in tackling a modified Sokoban environment with added teleportation features.

This figure compares the performance of WorldCoder against other methods (ReAct, Deep RL) on the Sokoban task. Panel (A) shows a sample Sokoban game environment. Panel (B) presents learning curves, illustrating WorldCoder’s significantly faster learning compared to ReAct. Panel (C) highlights the reduced LLM cost of WorldCoder, showing it’s more efficient in terms of LLM calls than other LLM agents. Panel (D) contrasts WorldCoder’s sample efficiency to that of deep RL methods, which need substantially more experience to achieve basic competence. Panel (E) shows a more complex variant of Sokoban used to further evaluate WorldCoder’s ability to adapt to new rules and dynamics.

This figure shows experimental results on Sokoban. (A) shows the Sokoban environment. (B) compares the learning curves of WorldCoder with and without the optimism objective and ReAct. It demonstrates WorldCoder’s sample efficiency. (C) compares the LLM token cost of WorldCoder with prior LLM agents, highlighting its compute efficiency. (D) compares the performance of WorldCoder with deep RL methods. (E) shows a nonstandard Sokoban domain with teleport gates to further illustrate WorldCoder’s ability to handle subtle dynamics.

This figure shows the experimental results on Sokoban. (A) shows an example gameplay in Sokoban. (B) compares the learning curves of WorldCoder, ReAct, and deep RL on solving Sokoban levels with different numbers of boxes. (C) illustrates the LLM token costs for each method. (D) shows the comparison of sample efficiency of WorldCoder and deep RL in solving basic levels of Sokoban. (E) introduces a nonstandard Sokoban task with teleportation portals.

This figure presents a comprehensive comparison of the proposed WorldCoder agent against other approaches on Sokoban tasks. (A) illustrates the Sokoban environment, showing the agent’s goal to push boxes onto target locations. (B) shows the learning curves of WorldCoder (with and without the optimism objective) compared to ReAct, illustrating improved sample efficiency. (C) highlights WorldCoder’s computational efficiency, showing significantly lower LLM costs. (D) compares WorldCoder’s performance with deep RL methods (PPO and DreamerV3), demonstrating superior sample efficiency in learning to solve the task. Finally, (E) showcases WorldCoder’s ability to adapt and learn in a modified Sokoban environment with teleport gates, highlighting its transfer learning capability.

This figure presents a comprehensive analysis of the proposed WorldCoder agent’s performance on Sokoban tasks, comparing it against other methods like ReAct and deep RL. Panel (A) shows a sample Sokoban environment, while (B) displays learning curves illustrating the superior sample efficiency of WorldCoder, especially with optimism enabled. Panel (C) highlights the computational efficiency of WorldCoder, showing it requires fewer LLM calls than ReAct. Panel (D) emphasizes the significant advantage over deep RL, requiring millions of steps for similar performance. Finally, (E) demonstrates WorldCoder’s adaptability by showcasing its success in a modified Sokoban environment with teleportation portals.

This figure presents a comparison of the WorldCoder agent’s performance against other methods on the Sokoban task. Panel (A) shows a sample Sokoban game environment. Panel (B) compares the learning curves of WorldCoder (with and without the optimism objective) and ReAct, highlighting WorldCoder’s superior sample efficiency. Panel (C) demonstrates WorldCoder’s reduced computational cost compared to other LLM agents by showing the number of LLM calls per task. Panel (D) visually contrasts WorldCoder’s learning speed against deep reinforcement learning methods, which require significantly more steps to reach the same level of performance. Finally, Panel (E) displays an example of a modified Sokoban environment featuring teleportation portals, showcasing WorldCoder’s adaptability to new environment dynamics.

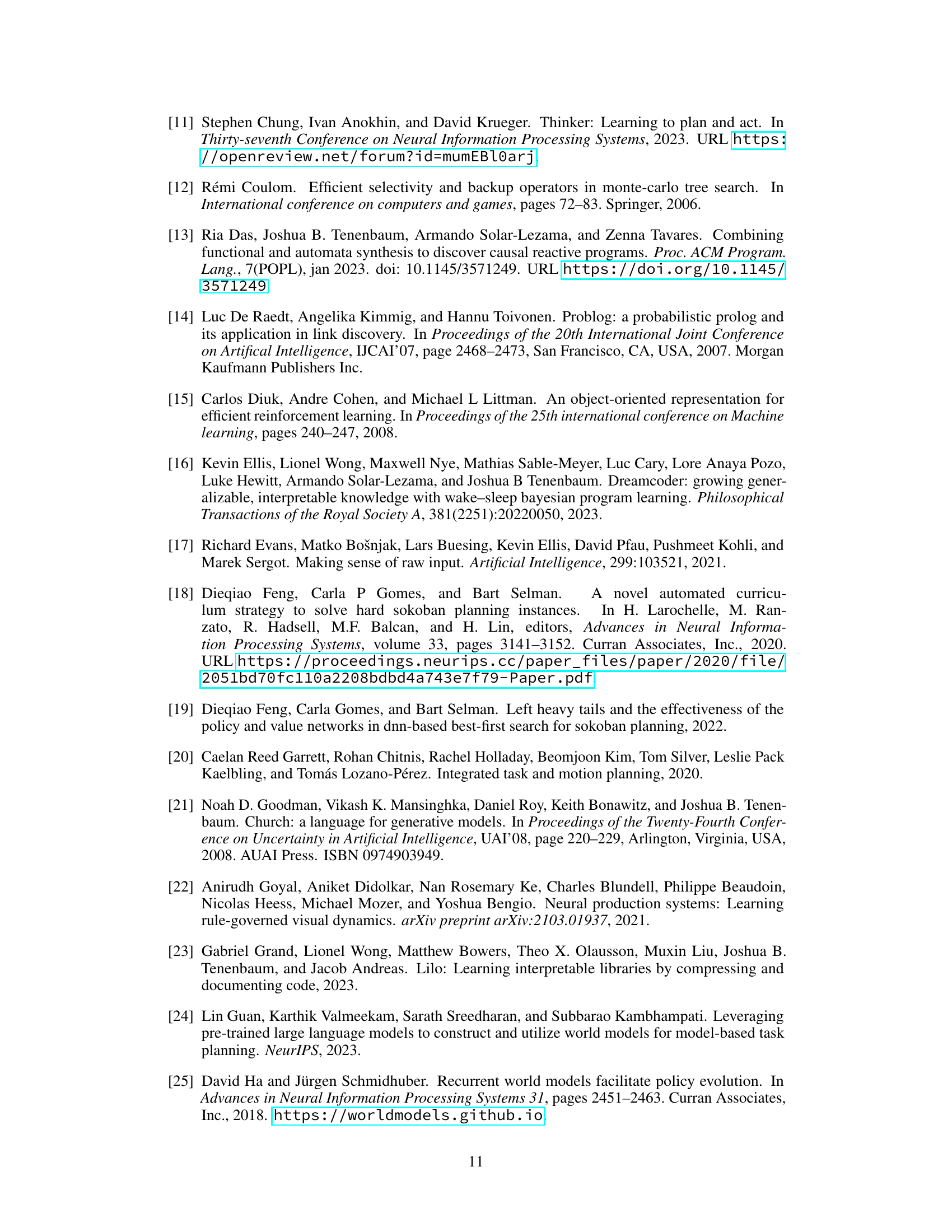

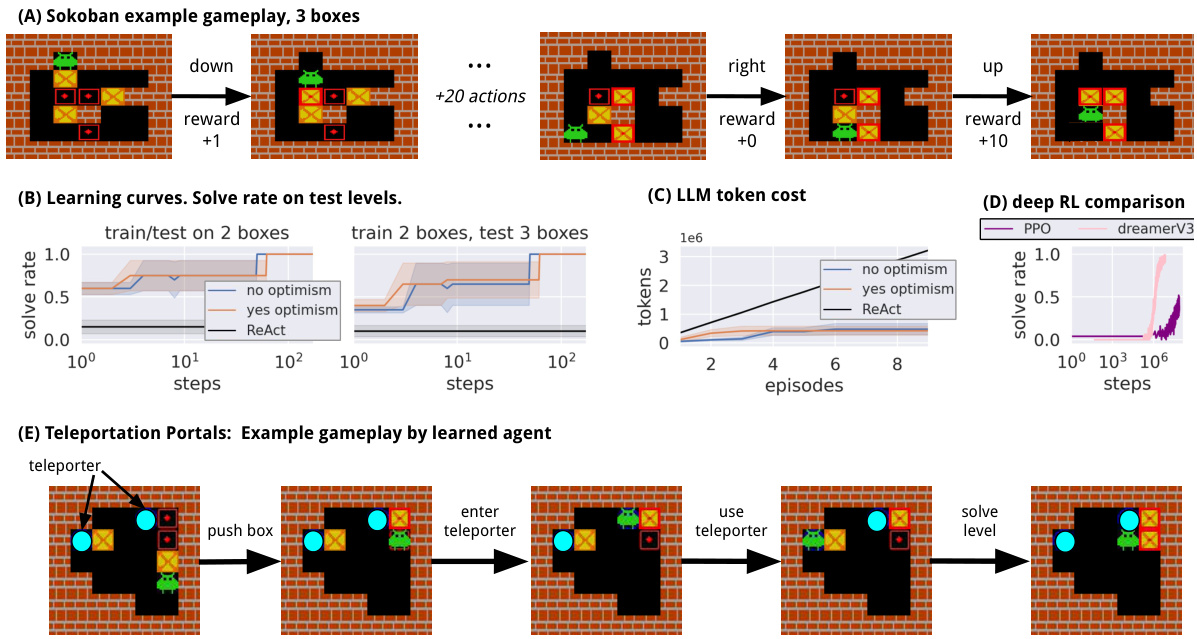

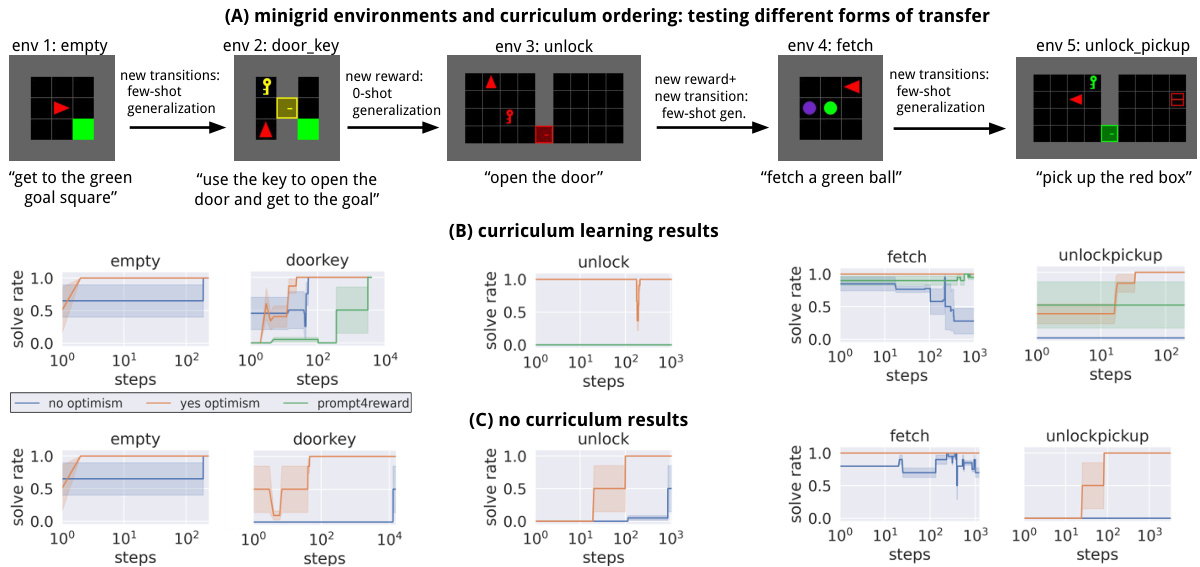

This figure shows the experimental results of the agent’s performance on a sequence of Minigrid environments. The environments are ordered into a curriculum designed to test different aspects of transfer learning. Part (A) shows the ordering of the environments and the types of transfer being tested (new transitions, new rewards). Part (B) shows the learning curves for the agent trained with the curriculum, demonstrating how knowledge transfer improves sample efficiency. Part (C) shows the learning curves for the agent trained on each environment independently, illustrating the lack of transfer and reduced sample efficiency compared to the curriculum approach. The Appendix Fig. 6, referenced in the caption, would contain a comparison of the agent’s performance to that of deep RL algorithms.

This figure presents a comprehensive comparison of the proposed WorldCoder model against existing state-of-the-art models on the Sokoban task. Subfigure (A) illustrates the Sokoban environment. Subfigure (B) showcases the learning curves, highlighting the superior sample efficiency of WorldCoder compared to the ReAct model, even with the same pre-trained knowledge. Subfigure (C) emphasizes the significant reduction in LLM calls per task, showcasing the computational efficiency of the proposed approach. Subfigure (D) further illustrates WorldCoder’s sample efficiency advantage over deep RL methods. Finally, subfigure (E) demonstrates the model’s ability to adapt and generalize to novel situations, as evidenced by its performance on a modified Sokoban environment incorporating teleport gates.

This figure presents a comprehensive evaluation of the WorldCoder agent’s performance on Sokoban tasks, comparing it with other approaches like ReAct and Deep RL. Panel (A) shows a sample Sokoban game state. Panel (B) displays learning curves, demonstrating WorldCoder’s superior sample efficiency compared to ReAct, which, despite having the same pretrained knowledge, struggles to play effectively. Panel (C) highlights the computational efficiency of WorldCoder, showcasing its significantly lower LLM call cost per task compared to ReAct-style agents. Panel (D) emphasizes the substantial gap in sample complexity between WorldCoder and Deep RL approaches, with Deep RL requiring millions of steps to master simple tasks. Finally, Panel (E) illustrates WorldCoder’s ability to adapt to novel game dynamics by adding teleport gates.

This figure presents a comparison of WorldCoder’s performance against other methods on the Sokoban task. Panel (A) shows an example Sokoban game environment. Panel (B) displays learning curves, illustrating WorldCoder’s superior sample efficiency compared to ReAct, even with equivalent pretrained knowledge. Panel (C) compares the asymptotic LLM token costs, highlighting WorldCoder’s significant computational advantages over methods requiring LLM calls at each step. Panel (D) demonstrates the substantial difference in sample efficiency compared to deep RL approaches. Finally, panel (E) showcases WorldCoder’s ability to adapt to novel game dynamics through the introduction of teleport gates.

This figure displays several key results related to the Sokoban experiment, showcasing the learning capabilities of the proposed WorldCoder agent. (A) illustrates a sample Sokoban level. (B) presents learning curves that compare WorldCoder (with and without the optimism objective) against the ReAct baseline. (C) highlights the asymptotic differences in LLM cost between WorldCoder and prior LLM agents. (D) compares the sample efficiency of WorldCoder against Deep RL methods, demonstrating its superior performance. (E) illustrates the adaptability of WorldCoder to a modified Sokoban level with teleport gates, further emphasizing its transfer learning capabilities.

This figure shows a comparison of WorldCoder’s performance with other methods on the Sokoban task. Panel (A) shows a typical Sokoban game state. Panel (B) presents learning curves demonstrating WorldCoder’s superior sample efficiency compared to ReAct and deep RL methods. Panel (C) illustrates that WorldCoder’s cost in terms of LLM calls only increases by a constant factor, regardless of the problem’s complexity, unlike other methods. Panel (D) highlights the significant difference in the number of steps needed by deep RL compared to WorldCoder to solve the task. Finally, Panel (E) showcases an example of non-standard Sokoban, including teleportation portals, where WorldCoder successfully adapts to the new dynamics.

This figure presents a comprehensive comparison of the proposed WorldCoder agent against several baselines across multiple aspects and domains. (A) Shows an example gameplay of the Sokoban domain, where an agent pushes boxes to target locations. The figure highlights the challenge of sparse rewards inherent to the domain. (B) Compares learning curves of WorldCoder with and without the proposed optimism learning objective, and ReAct, an LLM-based agent. The results demonstrate that WorldCoder achieves significantly higher sample efficiency and learns to solve the task quickly, unlike ReAct that only has the pretrained knowledge of Sokoban but fails to play effectively. (C) Illustrates the asymptotic LLM cost comparison. WorldCoder has lower asymptotic cost compared to the LLM-based agents that require frequent LLM calls for every action. (D) Shows a comparison to deep RL methods, highlighting that WorldCoder achieves sample efficiency compared to deep RL. (E) Presents an example of the non-standard Sokoban environment with teleport gates, showcasing the agent’s ability to adapt and solve the problem even with subtle changes in world dynamics.

This figure shows experimental results for the Sokoban environment. Panel (A) shows an example of the Sokoban game. Panel (B) presents learning curves comparing WorldCoder to ReAct, highlighting WorldCoder’s superior sample efficiency. Panel (C) compares the LLM token cost of WorldCoder versus other LLM agents. Panel (D) compares WorldCoder to deep RL methods, showing significantly better sample efficiency. Lastly, Panel (E) shows the application of WorldCoder to a more complex variant of Sokoban involving teleportation gates.

This figure presents a qualitative comparison of the proposed WorldCoder model with existing deep reinforcement learning (deep RL) methods and large language model (LLM) agents on the Sokoban task. Panel (A) shows an example Sokoban game environment. Panel (B) displays learning curves, highlighting the superior sample efficiency of WorldCoder compared to ReAct, an LLM-based agent. Panel (C) demonstrates the computational efficiency of WorldCoder, requiring a significantly lower number of LLM calls than ReAct. Panel (D) shows the sample inefficiency of deep RL methods on Sokoban. Finally, panel (E) illustrates WorldCoder’s robustness to modified environment dynamics, successfully solving a variant of Sokoban with added teleportation portals.

Full paper#