↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many real-world sequential decision-making problems involve complex information structures not captured by existing models like Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) or Partially Observable MDPs (POMDPs). These limitations hinder the development of efficient reinforcement learning algorithms and theoretical analysis of the statistical complexities involved. Current models often make restrictive assumptions about the information flow, making them inadequate for complex scenarios with complex interdependence among variables.

This paper introduces a novel reinforcement learning model that explicitly represents the information structure through a directed acyclic graph (DAG). Using this model, the authors carry out an information-structural analysis to characterize the statistical complexity of sequential decision-making problems, quantified by the size of an information-structural state. They prove an upper bound on the sample complexity of learning a general sequential decision-making problem using this framework and present an algorithm achieving this bound. This approach recovers existing tractability results for specific problem classes and provides a systematic way to identify new tractable classes of problems, offering valuable insights into reinforcement learning’s computational and statistical limitations.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in reinforcement learning because it provides a novel framework for analyzing and solving complex decision-making problems by explicitly modeling information structures. It identifies a new class of tractable problems and offers a systematic approach for identifying others, bridging the gap between theoretical understanding and practical applications. The graph-theoretic analysis of information structures offers new insights into the statistical complexity of RL, potentially impacting algorithm design and sample efficiency.

Visual Insights#

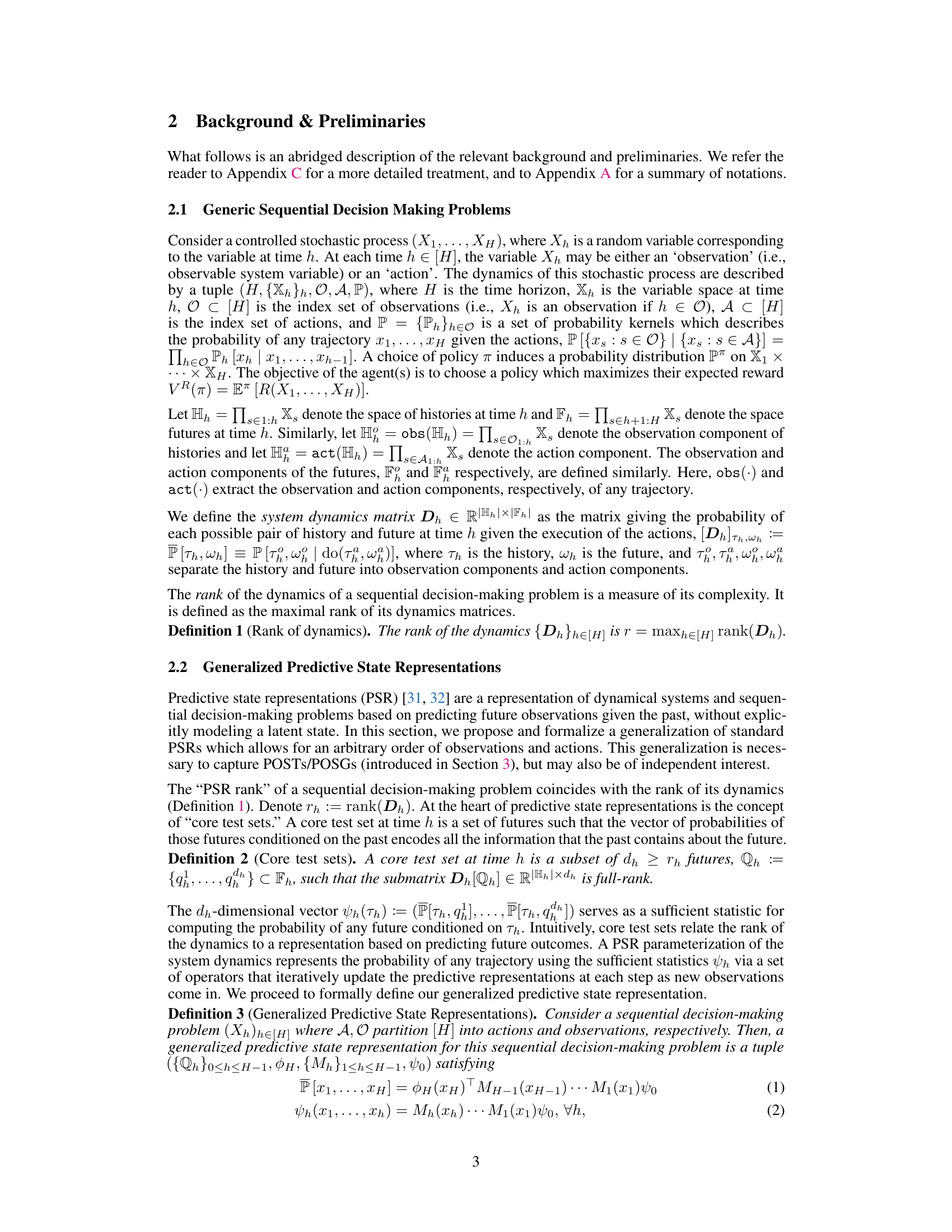

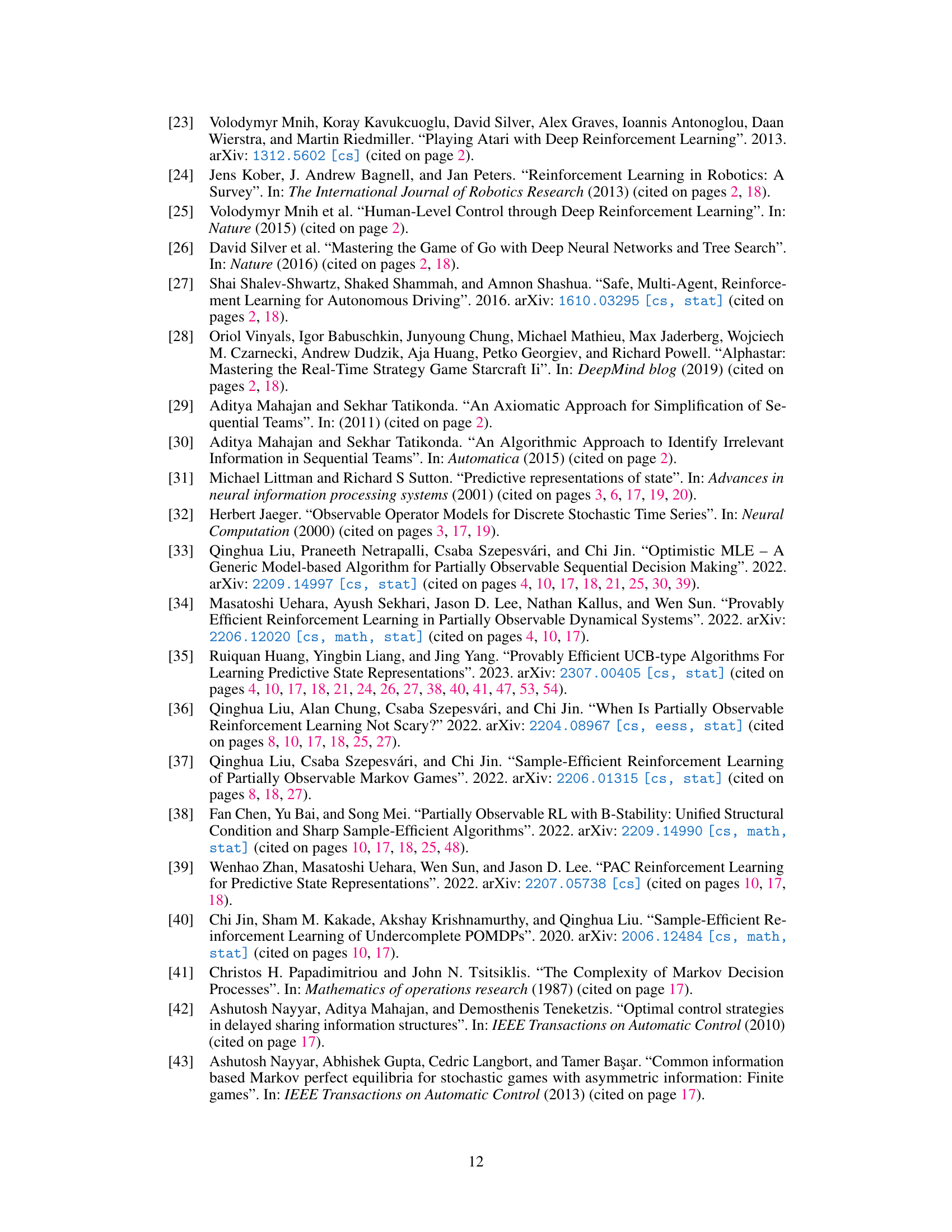

This figure shows a Venn diagram illustrating the relationships between different reinforcement learning models. The most general models are POSTs (partially-observable sequential teams) and POSGs (partially-observable sequential games). These encompass several other, more specialized models as subsets: MDPS (Markov Decision Processes), POMDPs (Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes), Dec-POMDPs (Decentralized Partially Observable Markov Decision Processes), and POMGs (Partially Observable Markov Games). The figure visually represents the hierarchical inclusion of these models, showing that POSTs and POSGs are the most comprehensive.

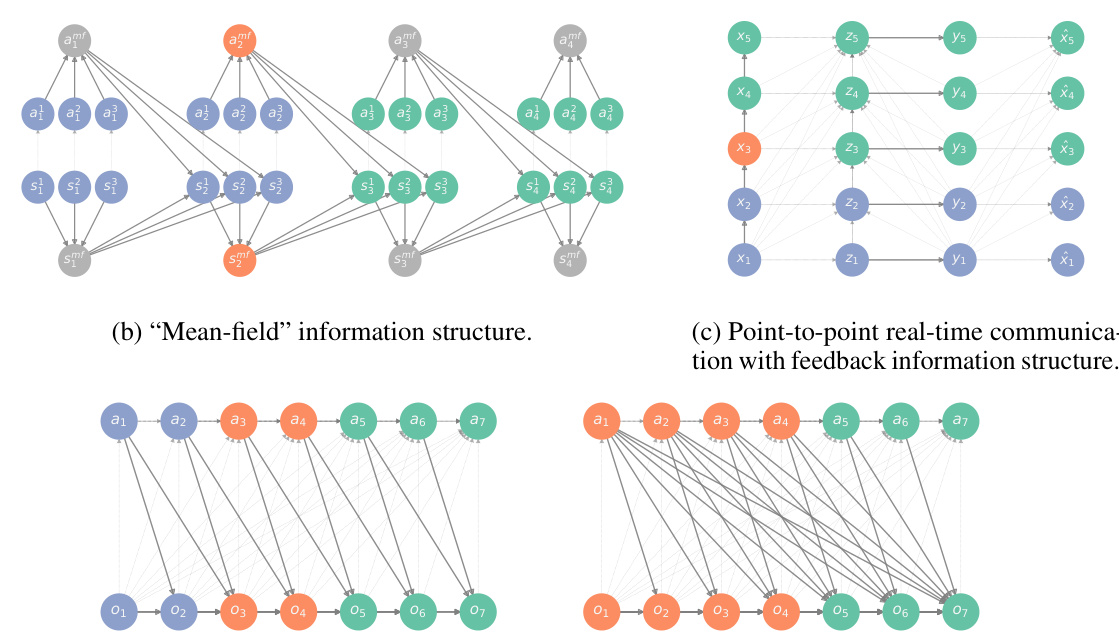

This table summarizes the notations used throughout the paper. It includes notations for generic sequential decision-making problems, POSTs/POSGs, generalized PSRs, and general mathematical notations. The notations cover variable spaces, sets of observations and actions, histories and futures, probability distributions, dynamics matrices, policies, and various quantities related to the predictive state representation.

In-depth insights#

Info Struct RL#

Info Struct RL represents a novel research area focusing on enhancing reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms by explicitly modeling and leveraging the information structure of the problem. Traditional RL methods often implicitly handle information flow, leading to suboptimal performance in complex scenarios. Info Struct RL addresses this limitation by representing causal dependencies between system variables and the information available to agents, enabling a more nuanced understanding of the decision-making process. This approach can lead to significant improvements in both sample efficiency and overall performance, especially in partially-observable environments or multi-agent settings. Key research directions within Info Struct RL include developing new theoretical frameworks for analyzing the impact of information structures on RL algorithms, designing novel algorithms that can efficiently learn and exploit these structures, and applying these techniques to real-world problems. The explicit representation of information flow offers a powerful tool for improving RL’s ability to handle complex real-world scenarios.

POST/POSG Models#

The paper introduces POST (Partially-Observable Sequential Teams) and POSG (Partially-Observable Sequential Games) models as a novel framework for representing information structures in reinforcement learning. POST/POSG models explicitly capture causal dependencies between system variables, moving beyond the limitations of classical models like MDPs and POMDPs which assume restrictive information structures. This explicit modeling allows for a more nuanced analysis of real-world scenarios. The framework unifies various existing reinforcement learning models under a single umbrella, offering a more general theoretical perspective. By incorporating information structure explicitly, POST/POSG models enable a richer understanding of partial observability and its influence on the complexity of decision-making problems. The core contribution lies in the formalization of information structure via directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) and its connection to the complexity of reinforcement learning, as measured by a novel graph-theoretic quantity related to the DAG’s structure. This allows for a systematic way to identify tractable classes of partially observable problems.

PSR Parameterization#

The heading ‘PSR Parameterization’ suggests a section dedicated to representing dynamical systems using Predictive State Representations (PSRs). A crucial aspect would be defining core test sets, which are minimal sets of future observations sufficient to capture all relevant information from the past. The discussion likely involves constructing a PSR model from these core sets. This may include defining the predictive state vector, which summarizes relevant past information for prediction, and the transition operators, which update the state vector based on new observations and actions. The choice of core test sets is critical, as it directly impacts the model’s complexity and dimensionality. A key consideration would be the trade-off between model expressiveness and computational cost. The text might detail algorithms for efficiently constructing the PSR parameters from data, potentially highlighting challenges related to high-dimensional spaces or the identifiability of system dynamics. Ultimately, this section aims to establish how to effectively encode information from sequential observations and actions into a tractable and informative representation suitable for planning and decision making.

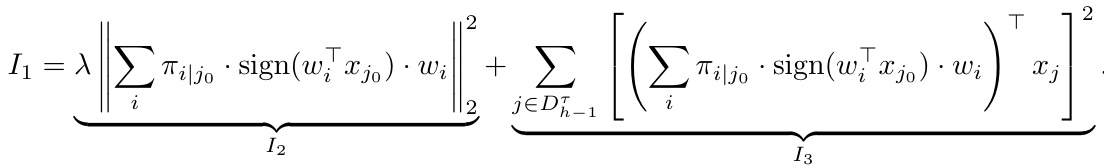

Sample Complexity#

The analysis of sample complexity is crucial for understanding the learnability of reinforcement learning models. The paper investigates the effect of information structure on sample complexity, demonstrating that models with simpler information structures have lower sample complexity. This is achieved by formalizing a novel reinforcement learning model that explicitly represents the information structure, offering a graph-theoretic characterization of statistical complexity. A key finding is the upper bound on sample complexity, relating it to the size of an ‘information-structural state,’ a generalization of a Markovian state. This provides a novel way to systematically identify new tractable classes of problems, offering a theoretical justification for the observed tractability of many real-world models. The resulting algorithm provides a more efficient solution for learning by taking advantage of the information structure.

Game Setting#

In a game setting, unlike cooperative scenarios, multiple agents pursue diverse objectives, leading to inherent conflicts and strategic interactions. The information structure, detailing what each agent knows at each decision point, becomes critical in determining the game’s equilibrium. Partial observability, where agents lack complete knowledge of the system’s state, adds another layer of complexity, making the identification of optimal strategies more challenging. The concept of equilibria, such as Nash equilibrium or coarse correlated equilibrium, depending on the extent of allowed randomization in agent policies, are key to understanding the solution concepts in a game setting. Modeling the game’s information structure explicitly is crucial for analyzing its complexity and for developing efficient reinforcement learning algorithms. The model must capture the interplay of the agents’ actions, their observations, and the system’s dynamics, allowing for the identification of optimal strategies or, more realistically, an approximation thereof.

More visual insights#

More on figures

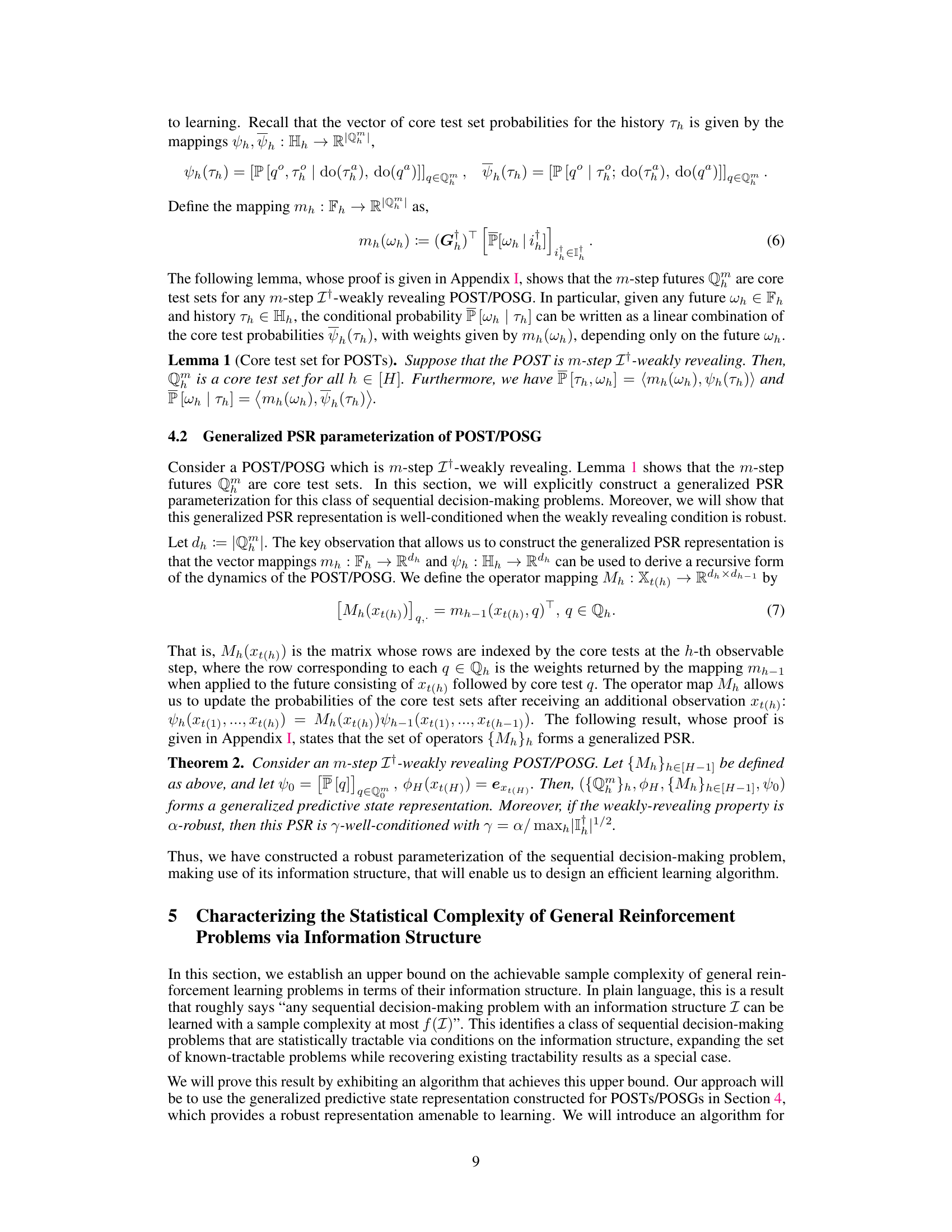

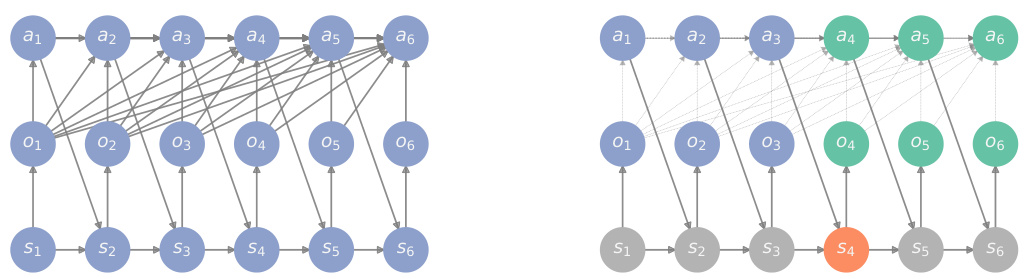

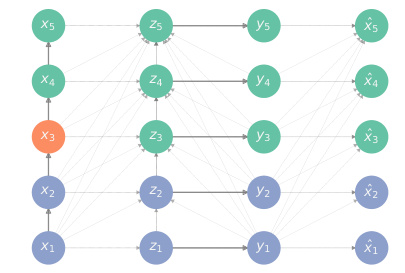

This figure illustrates the concept of information-structural state in the context of POMDPs. It shows two DAGs. The left DAG (G) represents the full information structure of the POMDP, indicating causal relationships between variables (states, observations, actions). The right DAG (G†) is a modified version of G where edges pointing to action variables are removed. The information-structural state (depicted in red) is the minimal set of past variables that renders past and future observations conditionally independent, effectively serving as a sufficient statistic for predicting future observations. This concept generalizes the notion of a Markovian state.

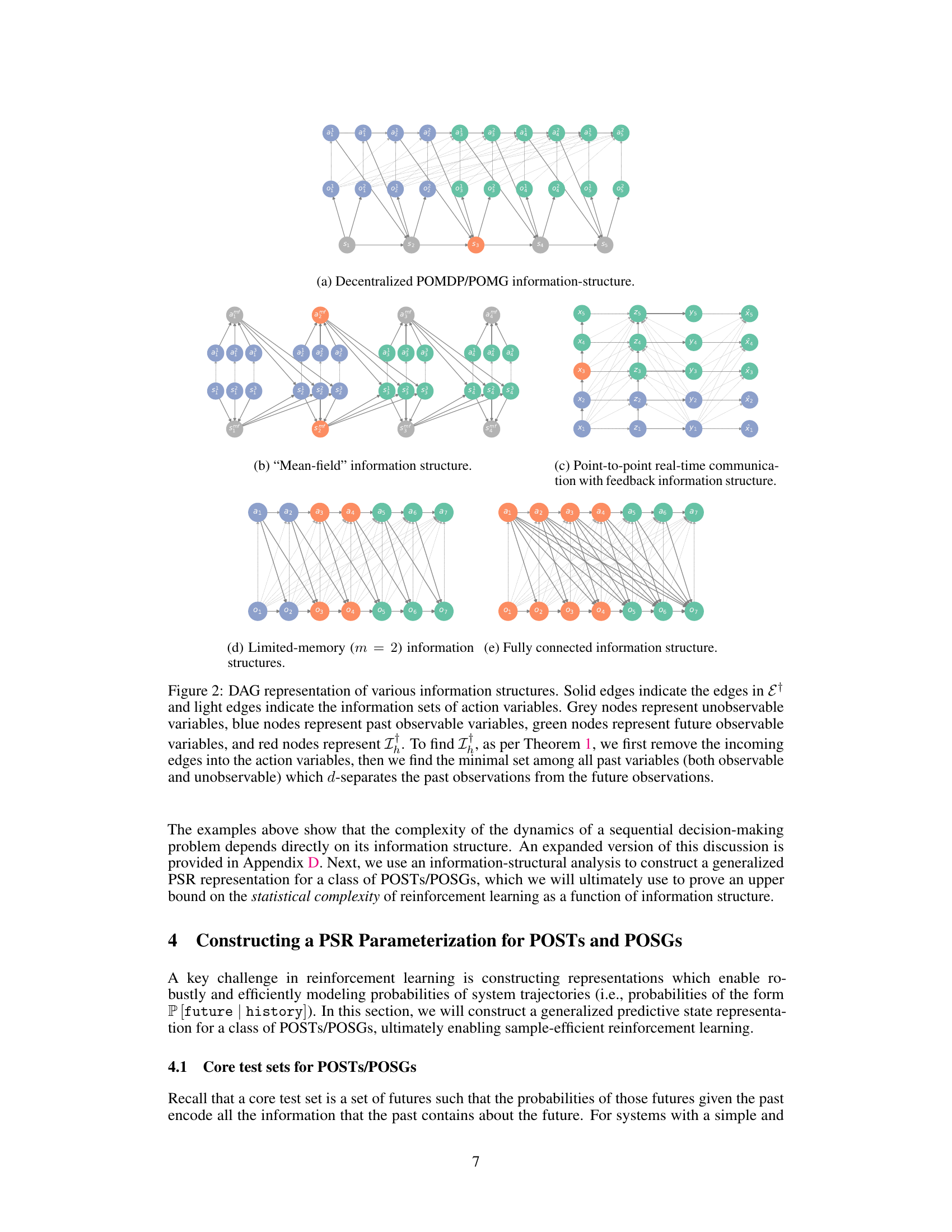

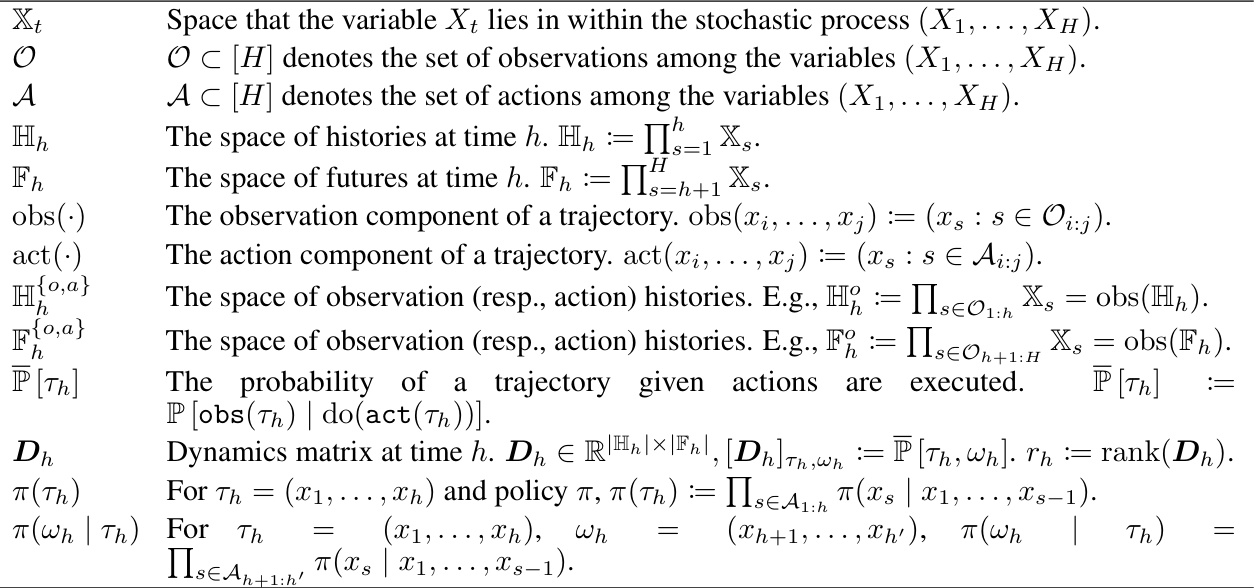

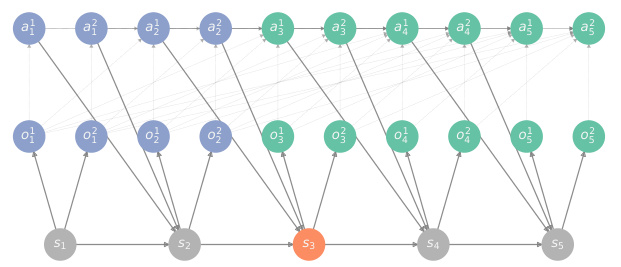

This figure shows the DAG representation of five different information structures. Each node represents a variable, and edges indicate causal relationships between variables. Different node colors represent different variable types (e.g., system variables, action variables, observable variables). The figure illustrates how the information structural state, a crucial concept in the paper, can be identified from the DAGs. The information structural state is the minimal set of past variables (observable and unobservable) that separates past and future observations, determining the complexity of the system’s dynamics.

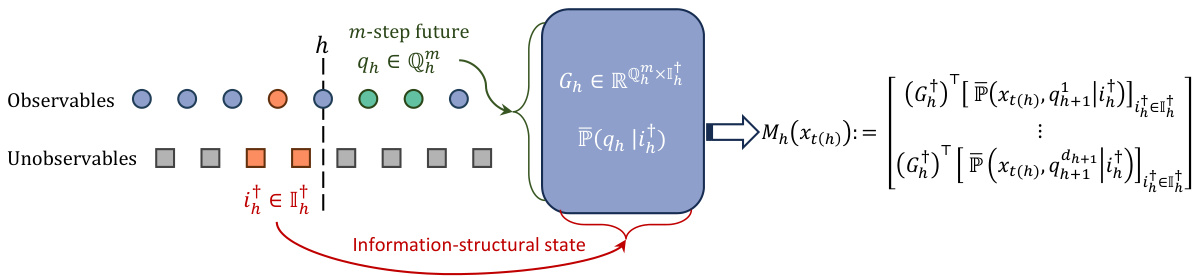

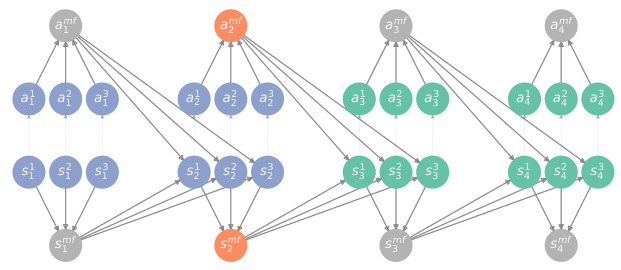

This figure shows a schematic representation of how to construct a generalized predictive state representation for partially observable sequential teams (POST) and partially observable sequential games (POSG). It highlights the key components including the information structural state (I†h), which is a sufficient statistic for predicting future observations given the past; m-step future observable trajectories that serve as core test sets (Qm); and the transition operator Mh(xt(h)) that updates the representation based on the current observable and information structural state.

This figure shows five examples of DAG representation of information structures of different types of sequential decision-making problems. The nodes represent variables and the edges represent the causal relationships between them. The color of the nodes indicate whether the variable is observable (blue, green) or unobservable (grey) and whether the variable belongs to the past (blue) or future (green). The red nodes represent the information-structural state, which according to Theorem 1 is a sufficient statistic of the past to predict the future observations.

This figure shows five different DAG representations of various information structures. Each DAG visually represents causal dependencies between variables, illustrating different levels of complexity. The nodes represent variables (observable or unobservable, past or future, action or system) and the edges represent causal dependencies between them. The red node represents the information-structural state which is crucial for determining the complexity of the problem. The figure aids in understanding Theorem 1 and the effects of various information structures on the complexity of sequential decision-making problems.

This figure shows different DAG representations of various information structures in sequential decision making problems, including decentralized POMDP/POMG, mean-field, point-to-point real-time communication with feedback, limited-memory, and fully-connected structures. Each node represents a variable, solid edges represent causal dependencies between system variables, and light edges represent information sets of action variables. Grey, blue, green, and red nodes represent unobservable, past observable, future observable, and information structural state variables, respectively. The figure illustrates how the complexity of observable system dynamics changes across different information structures by using the concept of d-separation to identify the minimal set of past variables that d-separate past observations from future observations. This minimal set is the information structural state, I†, which is shown in red.

This figure shows different DAG representations of information structures. Each DAG represents a different sequential decision-making problem. The nodes represent the variables in the problem, which can be observable or unobservable, action or state. The edges represent the dependencies between the variables. Each row represents the sequence of variables at a specific time step. The red node shows the information structural state, which is a sufficient statistic to predict the future given the past. The figure illustrates how the information structure can significantly affect the complexity of a sequential decision-making problem.

This figure shows several examples of information structures represented as directed acyclic graphs (DAGs). Each DAG visually depicts the causal relationships between variables in a sequential decision-making problem. Different colors are used to represent different types of variables (unobservable, past observable, future observable, action variables). The red nodes highlight the information-structural states, which are minimal sets of past variables that make the past and future observations conditionally independent. This visualization helps to understand how the information structure influences the complexity of the system dynamics, which is crucial for reinforcement learning.

This figure shows the directed acyclic graph (DAG) representation of five different information structures. Each DAG represents the causal relationships between variables in a sequential decision-making problem. The nodes represent variables, and the edges represent causal dependencies. Grey nodes are unobservable, blue are past observables, green are future observables, and red is the information-structural state (I). Theorem 1 of the paper uses the DAG to determine an upper bound on the rank of the observable system dynamics, a key factor in determining the complexity of the problem. The five examples illustrate variations in complexity ranging from simple (decentralized POMDPs/POMGs) to complex (fully connected).

Full paper#