↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Optical neural networks (ONNs) offer advantages in speed and energy efficiency for AI, but their real-world performance often lags behind simulations due to systematic errors from light source instability and exposure time mismatches. These errors hinder accurate predictions, creating a significant challenge for researchers.

This paper introduces a novel physics-constrained ONN learning framework. It uses a well-designed loss function to handle light fluctuations, a CCD adjustment strategy for exposure time variations, and a physics-informed error compensation network to manage other systematic errors. Experiments show significant accuracy improvements across multiple datasets, outperforming existing ONN approaches and demonstrating the framework’s robustness and effectiveness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in optical computing and neural networks. It bridges the gap between theoretical models and physical implementations of optical neural networks (ONNs), a critical issue limiting their practical applications. The proposed physics-constrained ONN learning framework is highly relevant to current research trends towards robust and efficient ONNs and opens up new avenues for improving ONN performance and reliability.

Visual Insights#

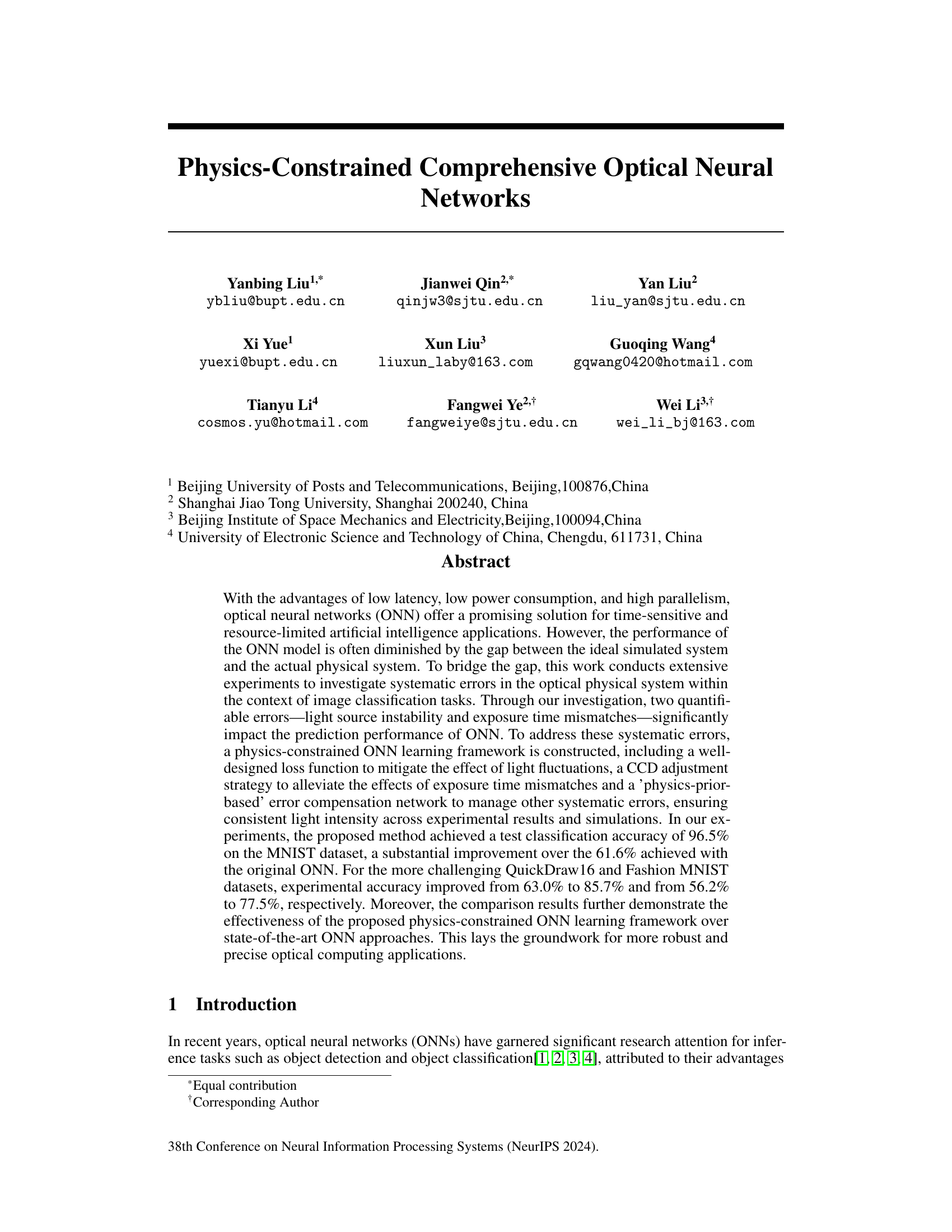

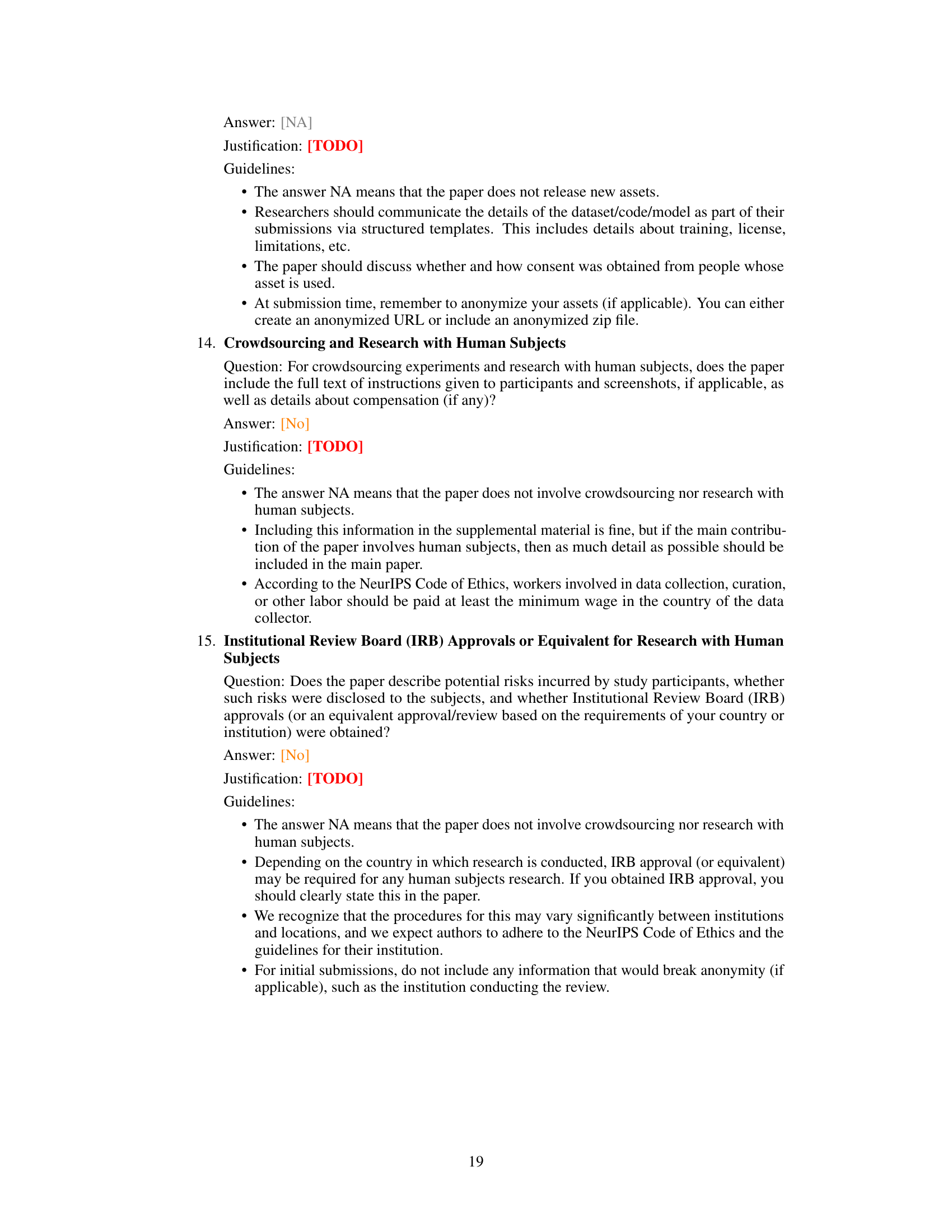

This figure illustrates four different approaches to building and training optical neural networks (ONNs). (a) shows a basic approach where a simulated DNN is used to train the parameters, which are then deployed to a physical ONN. (b) incorporates a physical error model into the training process to compensate for known systematic errors. (c) uses a hybrid approach where the physical ONN is integrated into the training loop. (d) uses a two-part network, an ideal model and an error compensation network, to compensate for both known and unknown errors.

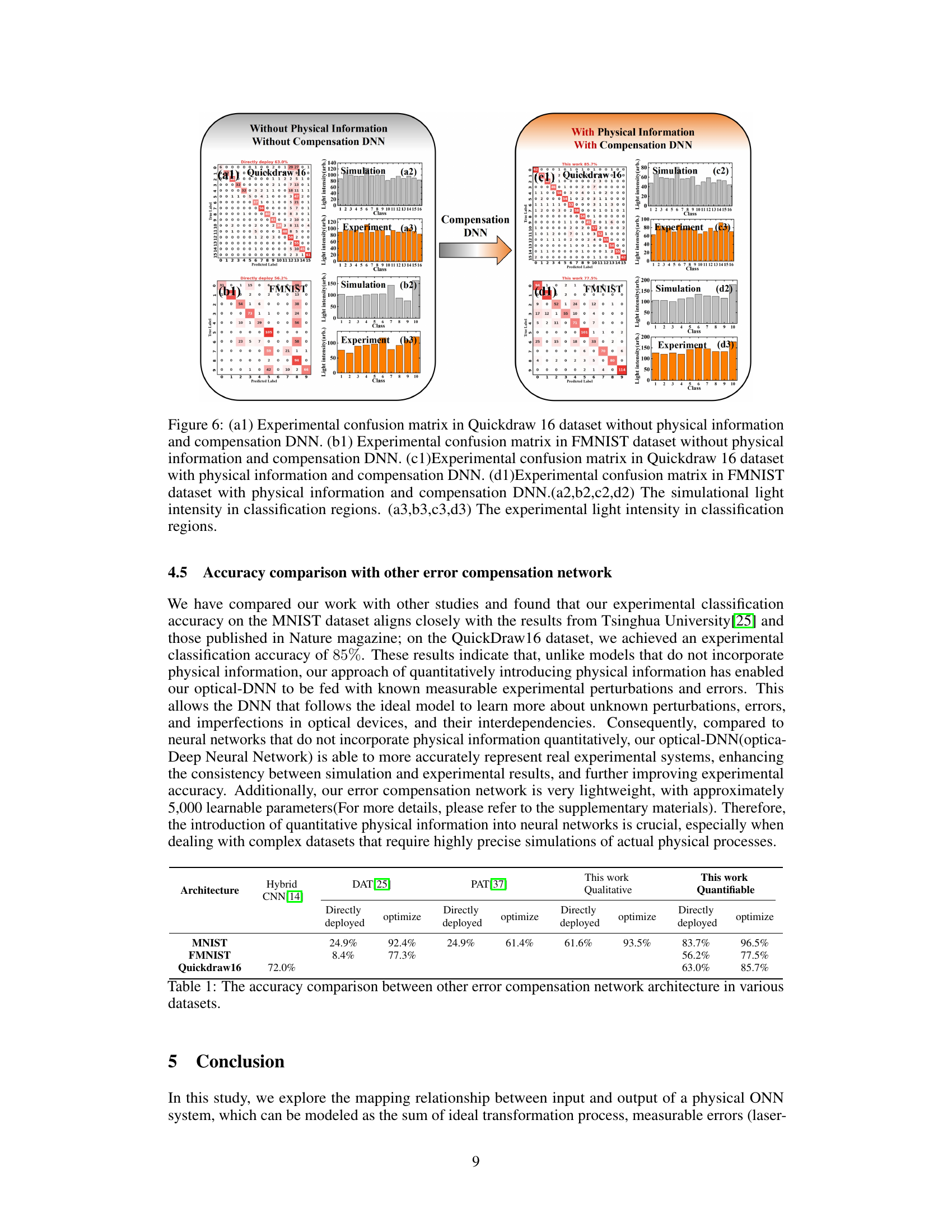

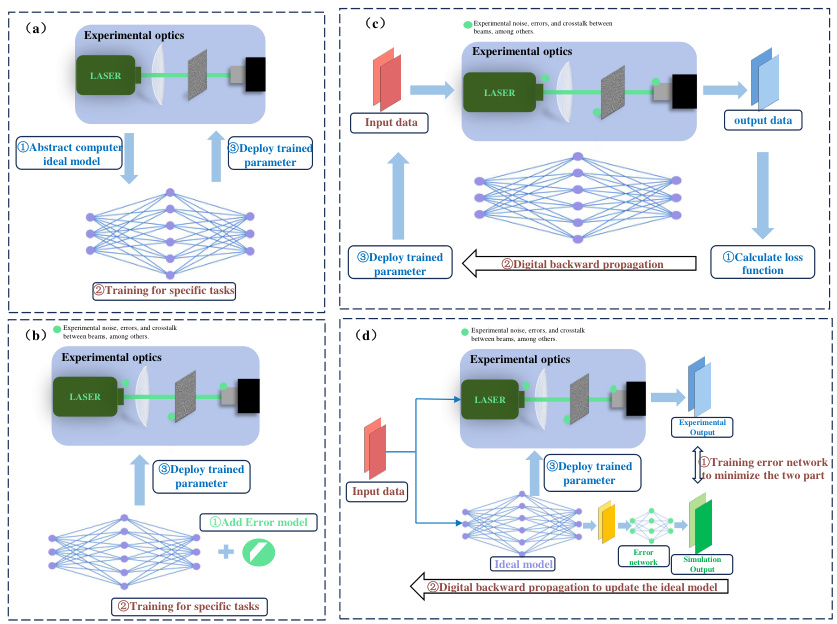

This table compares the accuracy of different error compensation network architectures, including Hybrid CNN, DAT, PAT, and the proposed methods (Qualitative and Quantifiable), across three datasets: MNIST, FMNIST, and Quickdraw16. It highlights the improvement in accuracy achieved by incorporating quantifiable physical information into the proposed error compensation network.

In-depth insights#

Physics-Constrained ONN#

The concept of a Physics-Constrained Optical Neural Network (ONN) signifies a crucial advancement in optical computing. It directly addresses the persistent challenge of discrepancies between simulated ONN models and their physical implementations. The core idea is to integrate quantifiable physical parameters—like laser instability and exposure time—into the ONN’s architecture and learning process. This constraint significantly reduces the complexity of error compensation, as the model focuses on learning only the remaining unmeasurable system errors. By doing so, the framework enhances robustness and accuracy, bridging the simulation-reality gap that often hinders the practical deployment of ONNs. The effectiveness of this approach is demonstrably shown through improved performance on standard image classification tasks, showcasing the potential of Physics-Constrained ONNs for more reliable and precise optical computing applications. A key strength lies in its ability to combine data-driven and physics-driven approaches, leveraging the benefits of both for superior modeling. This is especially valuable for complex optical systems where purely data-driven approaches might fall short.

Error Compensation#

The concept of ‘Error Compensation’ in the context of optical neural networks (ONNs) is crucial for bridging the gap between theoretical models and real-world implementations. Systematic errors, stemming from factors like light source instability and exposure time mismatches, significantly impact ONN performance. The research explores strategies to address these issues. A key approach involves incorporating quantifiable physical information directly into the network’s architecture. This allows the model to learn and correct for predictable deviations caused by known physical limitations. By integrating these constraints, the network’s search space is reduced, enabling faster convergence and improved accuracy. Physics-prior-based error compensation networks are also used to handle unmeasurable errors, combining data-driven learning with physical models to improve the overall robustness and reliability of ONN systems. The effectiveness of this physics-constrained approach is demonstrated through substantial improvements in classification accuracy across multiple datasets, indicating the significant potential for error compensation techniques to enhance ONN performance.

Experimental Setup#

A well-defined ‘Experimental Setup’ section is crucial for reproducibility and understanding. It should detail the hardware components used, specifying models and configurations (e.g., SLM resolution, CCD sensor type, laser parameters). The optical system’s architecture, including lens types and arrangements, should be clearly illustrated with diagrams and specifications. Precise descriptions of alignment procedures are necessary, as minor misalignments significantly impact results. Furthermore, environmental factors affecting the experiment should be addressed—temperature control, vibration isolation, and light shielding are important. The data acquisition process should be outlined including sample preparation, data recording methods, and any preprocessing steps taken. Finally, the section needs to specify calibration methods used to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the measurements. Only with this level of detail can others truly replicate the experiments and independently verify the findings.

Accuracy Improvements#

Analyzing potential improvements in accuracy within a research paper necessitates a multifaceted approach. Identifying the specific methodologies used to enhance accuracy is crucial, such as novel algorithms, refined model architectures, or improved data preprocessing techniques. Quantifying the extent of these improvements is equally important, requiring a clear presentation of metrics, comparisons with existing methods, and a discussion of statistical significance. Understanding the underlying reasons for these improvements is key. This involves analyzing the theoretical underpinnings of the methodologies and providing a clear explanation of how they address limitations of prior methods or leverage new insights. Context is crucial, requiring the inclusion of details about the dataset used, experimental conditions, and potential limitations of the improvements. A thorough analysis should also cover factors such as generalizability of the improved accuracy to different datasets or scenarios. Finally, the implications of these accuracy improvements for practical applications must be discussed. Only by considering these factors can a true understanding of accuracy enhancement be achieved.

Future Directions#

Future research directions stemming from this physics-constrained optical neural network (ONN) study could focus on several key areas. Expanding the range of applications beyond image classification is crucial, exploring tasks like object detection, image segmentation, and more complex visual reasoning. Addressing limitations in handling diverse types of noise and disturbances, such as crosstalk and ambient light interference, requires further investigation. Improving the efficiency and scalability of the training process through algorithmic advancements or hardware optimization is vital for real-world deployment. Investigating the use of different optical components and architectures might unlock new possibilities for enhanced performance and functionality. Finally, a thorough theoretical analysis of the physics-informed error compensation network and its generalizability could further solidify the foundations of physics-constrained ONN learning and lead to more robust and reliable optical computing applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

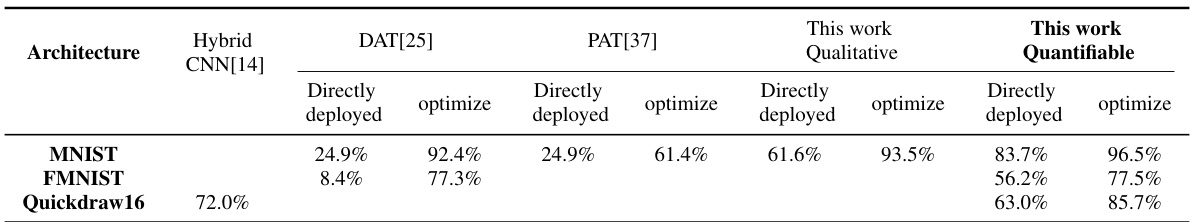

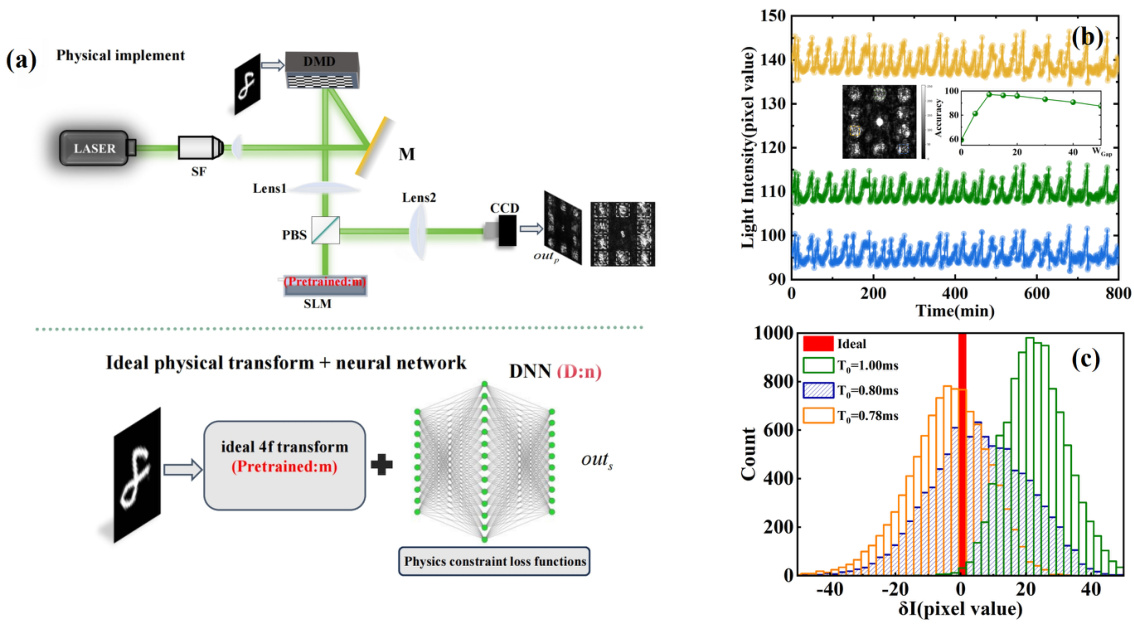

This figure illustrates how physical information is integrated into the simulation of physical systems to improve accuracy. Panel (a) shows the actual physical system, where the output signal g(u) is the sum of the ideal transformation f(u) and various errors: device imperfections (Δfdev), laser jitter (Δfjit), and other unmeasurable errors (η). Panel (b) shows the computer modeling and training process. The ideal transformation f(u) is combined with a deep neural network (DNN) that learns to compensate for the errors based on input-output training data pairs and quantifiable physical information (e.g., the range of Δfjit and the value of Δfdev). The integration of this physical information improves the precision of the simulation and reduces discrepancies between experimental and simulated results.

This figure shows the schematic of an image classification optical neural network that incorporates an error-compensating DNN with quantitative physical information. Subfigure (a) presents the experimental setup, while (b) illustrates the instability of laser light intensity over 700 minutes and its effect on classification accuracy. Subfigure (c) displays the discrepancies between simulated and experimental CCD readings for different exposure times.

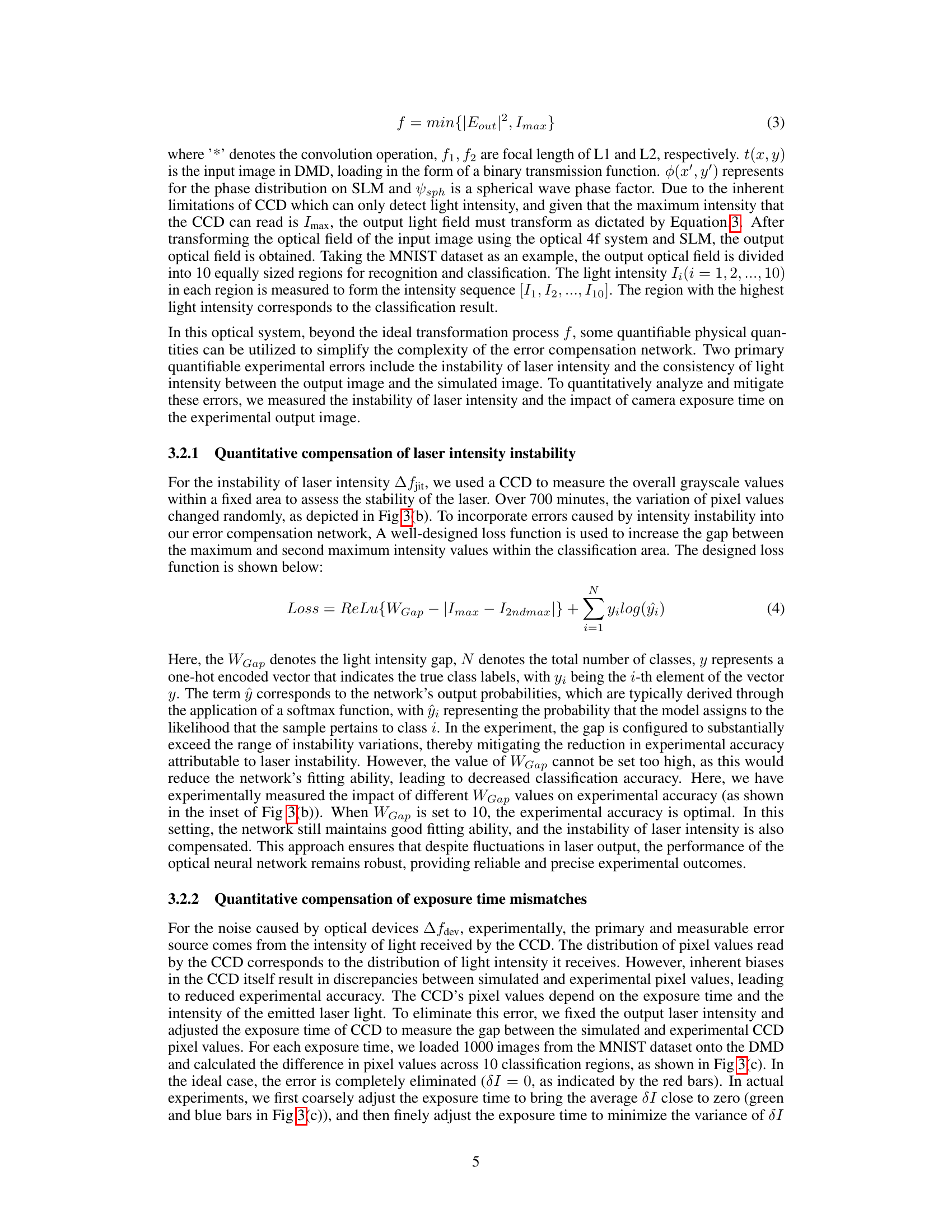

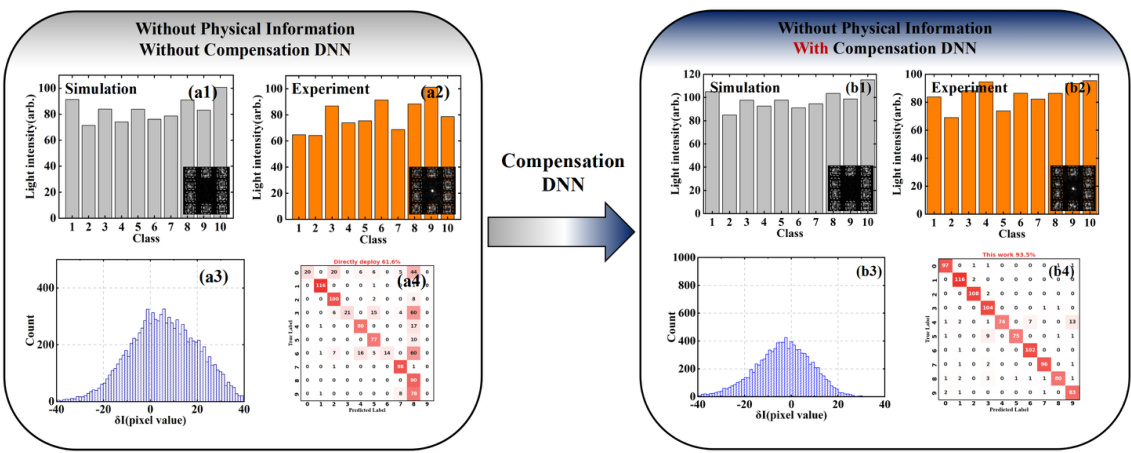

This figure shows the comparison of simulation and experimental results for light intensity distribution in ten classification regions of MNIST dataset with and without compensation DNN. The left panel shows results without quantifiable physical information, while the right panel shows results with compensation DNN. The comparison highlights the impact of introducing compensation DNN in improving the match between simulation and experimental results, leading to better accuracy.

This figure shows the architecture of the proposed physics-constrained optical neural network. It highlights three key aspects: (a) the overall system design showing the integration of the error-compensating DNN with the optical system, (b) the instability of the laser light intensity over time, and (c) the discrepancies between simulated and experimental CCD readings due to exposure time variations. The inset in (b) demonstrates the effect of adjusting the light intensity gap on the network’s accuracy.

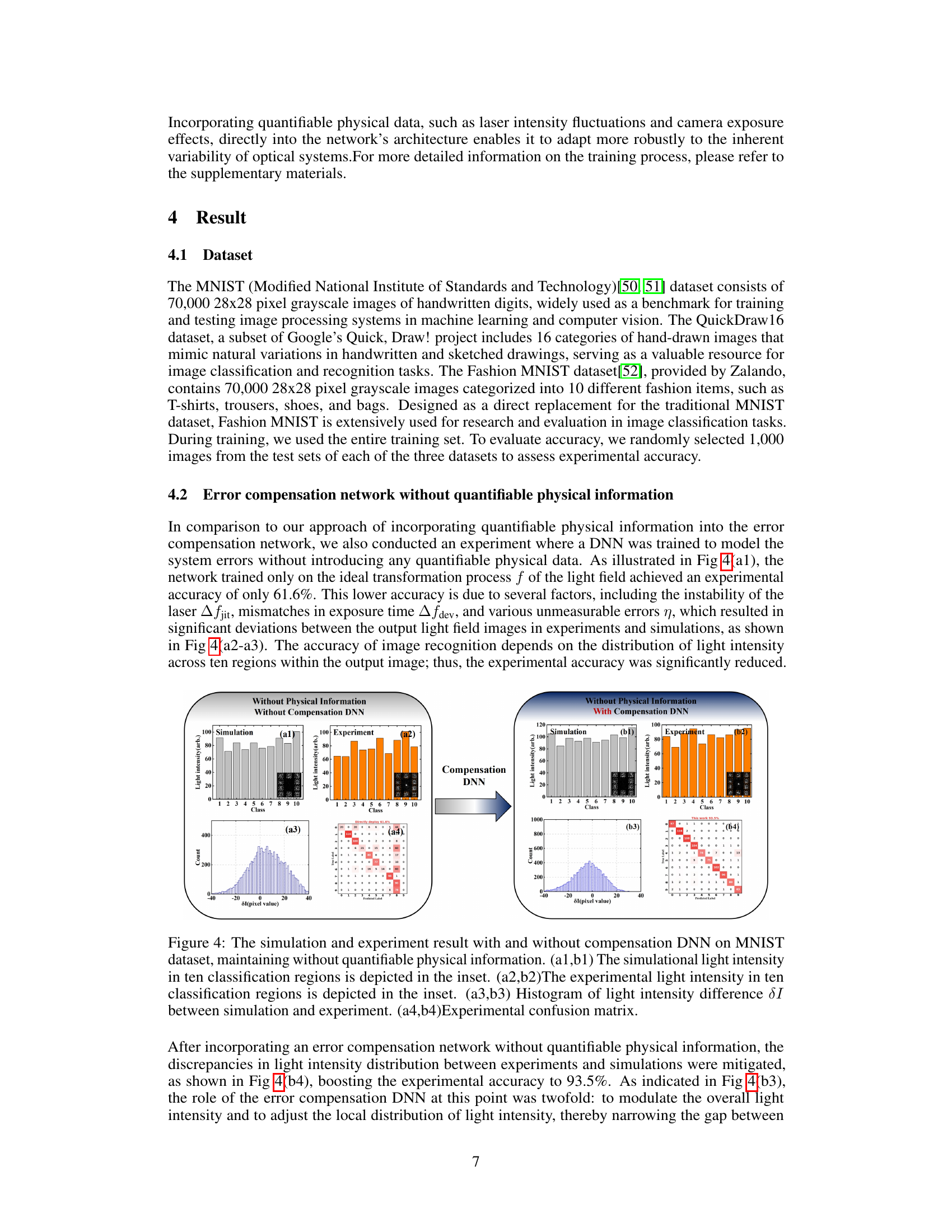

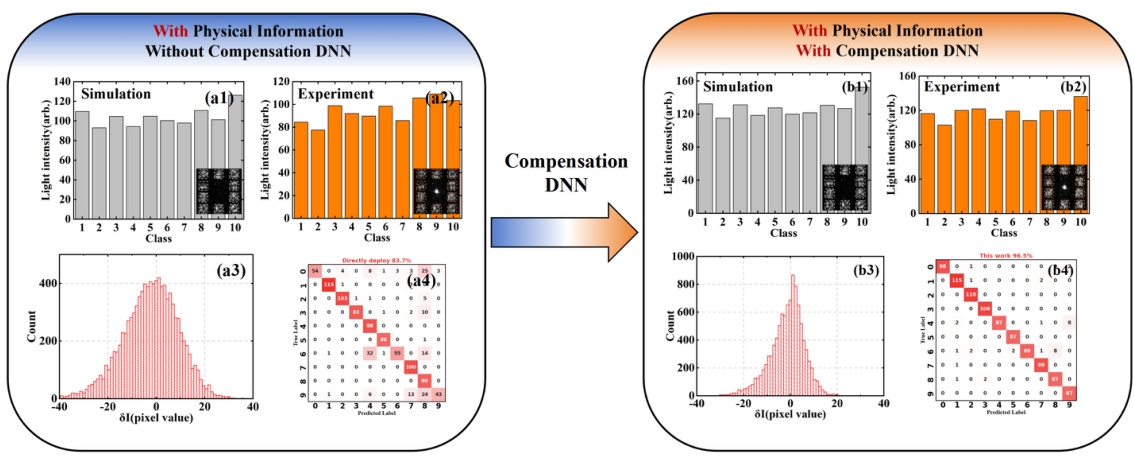

This figure compares the experimental results of image classification on Quickdraw16 and FMNIST datasets with and without using physical information and error compensation DNN. It shows confusion matrices visualizing classification performance and histograms illustrating the distributions of simulated and experimental light intensities across different classes. The comparison highlights the improvements in classification accuracy achieved by incorporating physical information into the error compensation network.

Full paper#