↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Many optimization algorithms struggle with stepsize selection, often relying on heuristics or computationally expensive linesearches. The global Lipschitz assumption for gradient methods is often unrealistic, particularly for non-convex problems with varying curvature. Existing adaptive methods, like Adagrad, suffer from decreasing step sizes, limiting their true adaptivity.

This paper tackles the above issues by proposing adaptive gradient methods that leverage local curvature information. These methods are shown to converge under the weaker assumption of only local Lipschitzness of the gradient. Importantly, the proposed methods are shown to allow for larger stepsizes than previously thought possible. The analysis is extended to proximal gradient methods for composite functions, which is a significant contribution, particularly given the added complexity.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents adaptive gradient methods that are more efficient and robust than traditional methods. This offers a significant improvement for various optimization problems, especially in machine learning and other fields requiring high-performance optimization. The work also opens up new avenues for research in adaptive optimization algorithms and their theoretical analysis. The improved convergence guarantees and ability to use larger steps are particularly relevant to research involving large datasets or complex models, where computational efficiency is crucial.

Visual Insights#

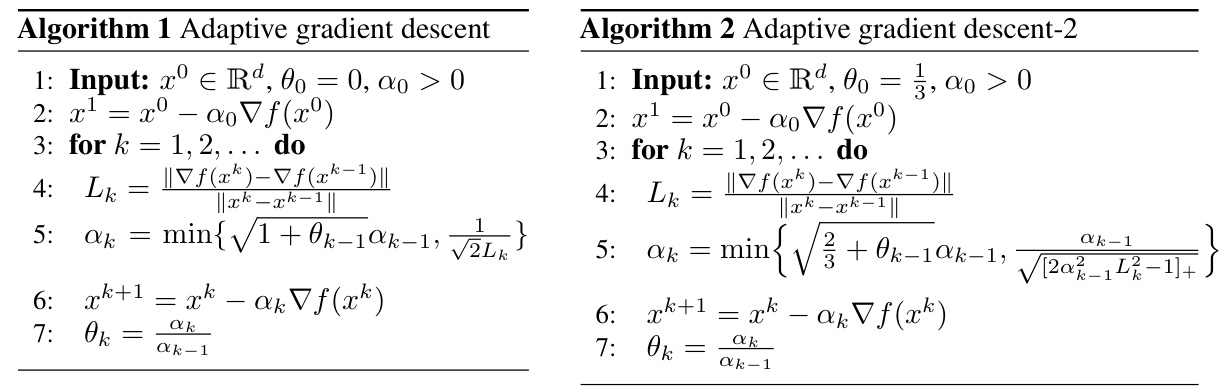

This figure shows the results of experiments on the minimal length piecewise-linear curve problem. The x-axis represents the number of projections, and the y-axis represents the objective function value. Multiple lines represent different instances of the ProxGD with Armijo’s linesearch, showcasing various choices for the parameters s and r. The AdProxGD line also shows the performance of the adaptive proximal gradient descent method, demonstrating faster convergence in both scenarios (a) and (b).

This table summarizes the theoretical convergence rates achieved by the proposed adaptive gradient descent methods (AdGD and AdProxGD) and compares them to the convergence rates of standard gradient descent and proximal gradient methods. It highlights the conditions under which each method achieves its respective rate, emphasizing the advantages of the adaptive methods in scenarios where the gradient’s Lipschitz constant is unknown or varies significantly.

In-depth insights#

Adaptive GD#

Adaptive Gradient Descent (GD) methods aim to overcome the limitations of traditional GD, which relies on pre-defined or manually tuned learning rates. Adaptive methods dynamically adjust the learning rate based on the local properties of the loss function, making them more robust and efficient. A key challenge lies in balancing the need for fast convergence with stability. Too aggressive an adaptation can lead to instability, while overly cautious adjustments might slow down the process. Many adaptive GD approaches leverage gradient information to estimate local curvature, enabling informed step size selection. This adaptive behavior is particularly advantageous in settings with non-uniform curvature, such as those commonly encountered in deep learning. However, theoretical analysis of adaptive GD methods can be complex, requiring careful consideration of various conditions on the objective function, such as smoothness or strong convexity. Furthermore, the computational overhead associated with the adaptive adjustments must also be weighed against potential gains in performance.

ProxGD Extension#

Extending the Proximal Gradient Descent (ProxGD) method is crucial for handling nonsmooth optimization problems. A thoughtful extension would involve carefully considering the interplay between the smooth and nonsmooth components of the objective function. This might include investigating how different proximal operators affect convergence rates and exploring techniques to adapt step sizes based on the local curvature of both components. Furthermore, a robust extension should provide theoretical guarantees on convergence and analyze the method’s performance on various problem classes. Computational efficiency should also be a primary concern, with emphasis on minimizing the overhead introduced by the extension. Finally, an ideal extension would offer enhanced adaptability to diverse problem structures and a broader range of practical applications.

Step Size Theory#

Step size selection is crucial in gradient-based optimization algorithms. A small step size leads to slow convergence, while a large step size might cause oscillations or divergence. Step size theory aims to provide principled ways to choose or adapt step sizes, ensuring both convergence and efficiency. This involves analyzing the algorithm’s behavior under different step size regimes, often leveraging concepts like Lipschitz continuity of the gradient or strong convexity of the objective function. Adaptive step size methods dynamically adjust the step size based on observed properties of the objective function, such as curvature or gradient changes. These adaptive methods often offer superior performance compared to methods using fixed step sizes, particularly when dealing with non-convex functions or functions with varying curvature. Theoretical analysis of step size methods typically focuses on establishing convergence rates, which measure the algorithm’s speed of convergence. However, practical considerations are also crucial, including computational cost, robustness to noise, and memory requirements. The ideal step size strategy balances theoretical guarantees and practical efficiency, resulting in fast and reliable convergence to an optimal solution.

Empirical Results#

An effective ‘Empirical Results’ section would meticulously detail experimental setup, including datasets, evaluation metrics, and baseline methods. It should then present results clearly, using tables and figures to compare the proposed method’s performance against baselines across various settings. Statistical significance of the findings should be rigorously established, and any limitations or unexpected behavior should be honestly discussed. Visualizations should be intuitive and informative, making it easy to grasp key performance trends. A truly comprehensive analysis would explore the impact of hyperparameters, investigating potential sensitivity to different choices. Robustness checks, such as the effects of noisy data or variations in data size, would strengthen the claims. Finally, a thorough discussion should connect empirical observations with the theoretical underpinnings, explaining any discrepancies and highlighting the practical implications of the results.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Extending the adaptive proximal gradient method to handle non-convex problems is a key area, as many real-world optimization tasks fall into this category. Developing more sophisticated techniques for step-size adaptation is crucial; the current method relies on local curvature information, and improvements could lead to faster convergence and robustness. Theoretical analysis of the algorithm’s convergence rate under weaker assumptions (e.g., relaxing the local Lipschitz condition) would strengthen its applicability. Finally, empirical evaluations on a broader range of applications are essential to demonstrate the algorithm’s practical effectiveness and compare it against other state-of-the-art methods. Investigating the impact of different parameter choices in the algorithm will help in optimizing its performance in diverse settings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows the results of solving the minimal length piecewise-linear curve subject to linear constraints problem (49) using the proposed adaptive proximal gradient method and ProxGD with Armijo’s linesearch. The plots compare the convergence speed in terms of the number of projections required to reach a certain objective function value for different problem dimensions (m, n). The adaptive proximal gradient method demonstrates faster convergence across different problem sizes than any of the linesearch variants.

This figure shows the results of applying the AdProxGD algorithm and several ProxGD algorithms with Armijo’s linesearch to solve the maximum likelihood estimation problem of the inverse of a covariance matrix with eigenvalue bounds. Two scenarios are presented: (a) with n=100, l=0.1, u=10, M=50 and (b) with n=50, l=0.1, u=1000, M=100. The plots show the convergence of the objective function with respect to the number of projections. AdProxGD demonstrates faster convergence than all linesearch variants in both scenarios.

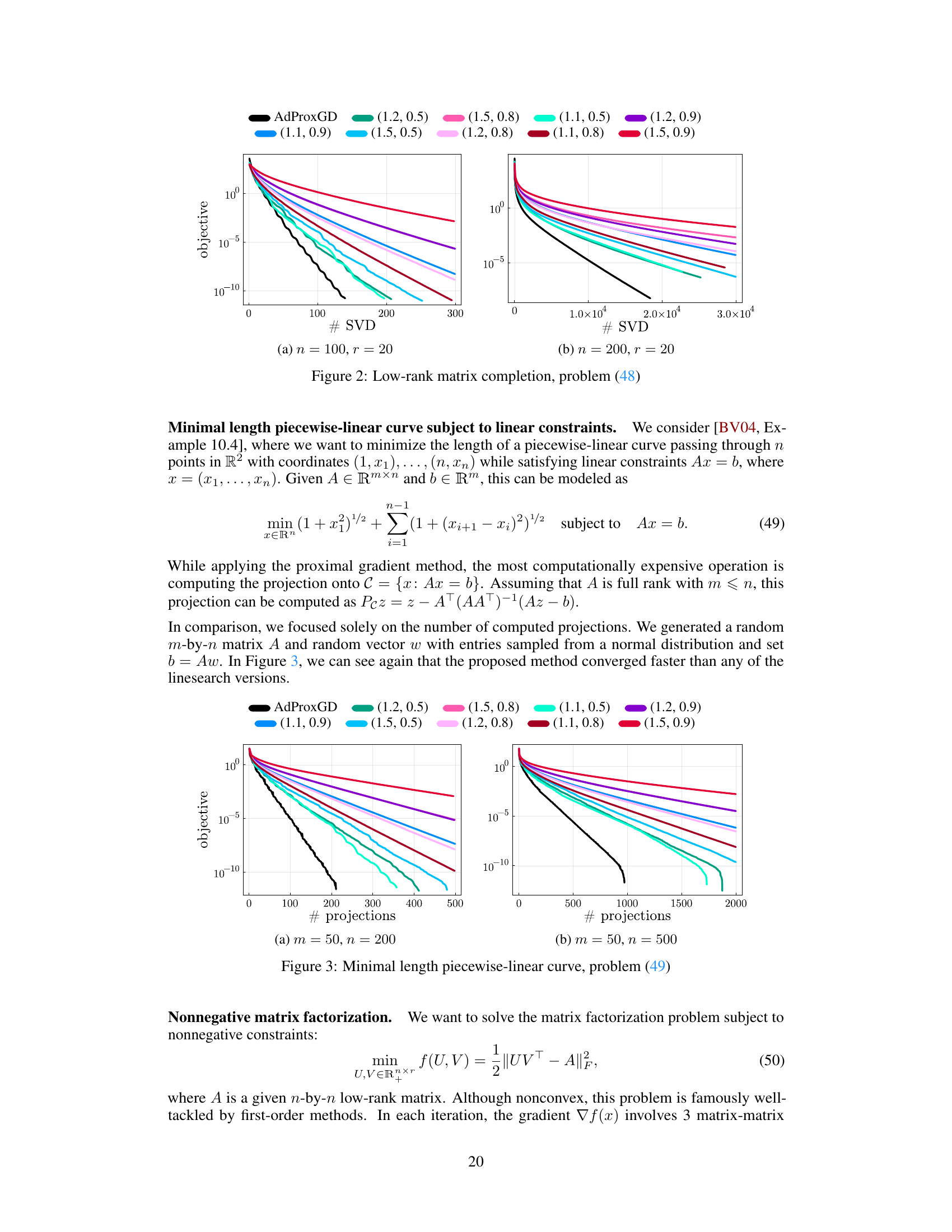

The figure shows the performance of AdProxGD and ProxGD with Armijo’s linesearch on a low-rank matrix completion problem. The x-axis represents the number of SVDs performed, and the y-axis represents the objective function value. Two scenarios are shown: (a) n=100, r=20 and (b) n=200, r=20, where n is the matrix dimension and r is the target rank. The results indicate that AdProxGD converges faster than ProxGD with various linesearch parameter settings.

This figure compares the performance of AdProxGD and ProxGD with Armijo’s linesearch on the minimal length piecewise-linear curve problem, which involves minimizing the length of a piecewise-linear curve subject to linear constraints. Two plots are shown, each with different problem dimensions (m,n) representing the number of constraints and points respectively. The plots showcase the convergence behavior of the algorithms in terms of the objective function value against the number of projections performed. AdProxGD demonstrates faster convergence compared to all variations of ProxGD with Armijo’s linesearch.

The figure shows the performance of AdProxGD and ProxGD with Armijo linesearch on the Nonnegative matrix factorization problem. The plots show the convergence of the objective function value against the number of gradient evaluations for different problem sizes (n=100, r=20 and n=100, r=30). AdProxGD demonstrates consistently faster convergence compared to all linesearch versions.

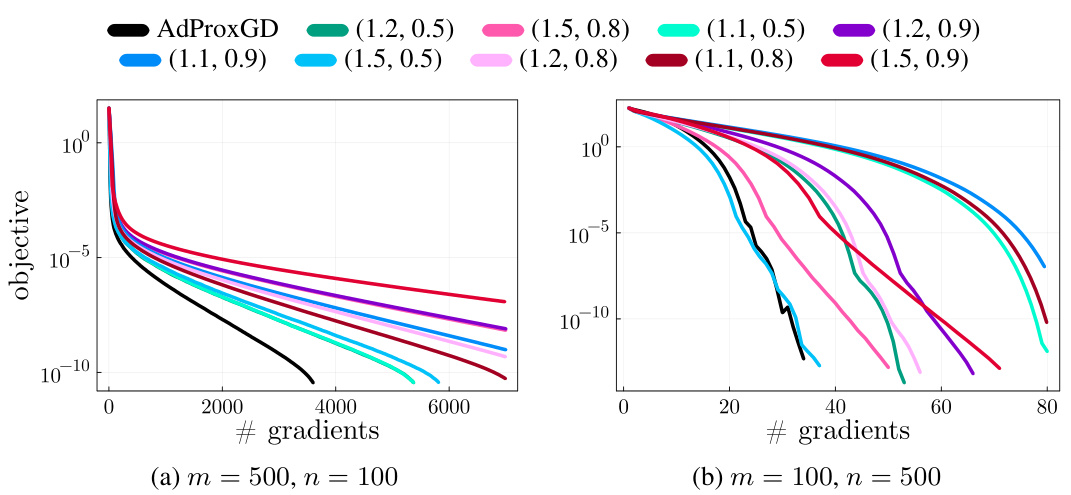

The figure shows the results of experiments comparing the performance of AdProxGD and ProxGD with Armijo’s linesearch on the minimal length piecewise-linear curve problem (49). The problem involves minimizing the length of a piecewise-linear curve subject to linear constraints. The plots show the objective function value against the number of gradient computations for two different problem sizes (m=500, n=100 and m=100, n=500). The results indicate that AdProxGD converges faster to the solution than the linesearch methods in both scenarios.

Full paper#