↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current object-centric representation learning methods lack theoretical identifiability guarantees, hindering their scalability and reliability. Existing methods often rely on strong assumptions, like additive decoders, that limit their applicability. This is problematic because high-dimensional data requires more flexible models and lacks such guarantees.

This paper introduces a probabilistic slot attention algorithm that addresses these limitations. By imposing a mixture prior over slot representations, the method provides theoretical identifiability guarantees. The authors demonstrate this approach’s efficacy and scalability using both simple 2D datasets and high-resolution image benchmarks, empirically verifying their theoretical findings. This work has significant implications for building more robust and reliable object-centric representation learning models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on object-centric representation learning. It addresses a critical gap in the field by providing theoretical identifiability guarantees, which are essential for scaling up slot-based methods. The proposed probabilistic slot attention algorithm offers a novel approach to learning object representations and opens avenues for more robust and reliable models.

Visual Insights#

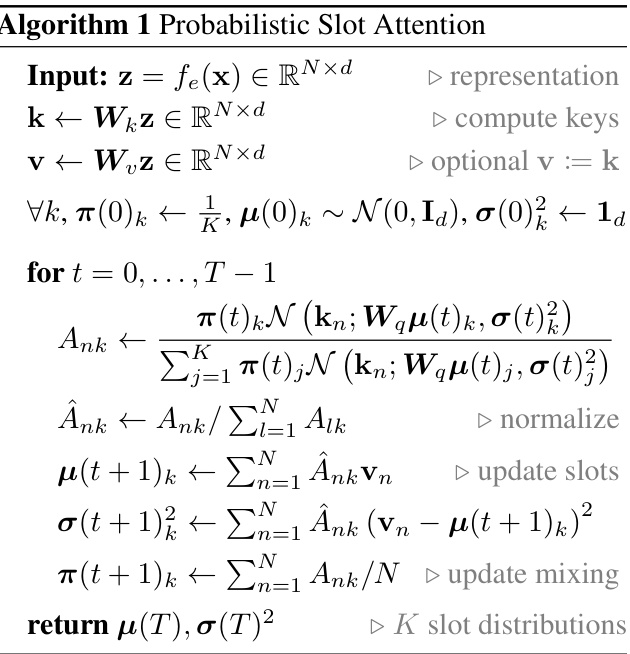

This figure illustrates the probabilistic slot attention model. The left side shows how local Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs) are fitted to the latent representations of individual data points. These local GMMs represent the posterior distributions of the object slots. The local GMMs are then aggregated to form a global GMM, which represents the aggregate posterior distribution over the object slots. This global GMM is shown on the left, demonstrating that it is tractable to sample from and identifiable up to an equivalence relation. The right side depicts the process of sampling slot representations from this aggregate posterior.

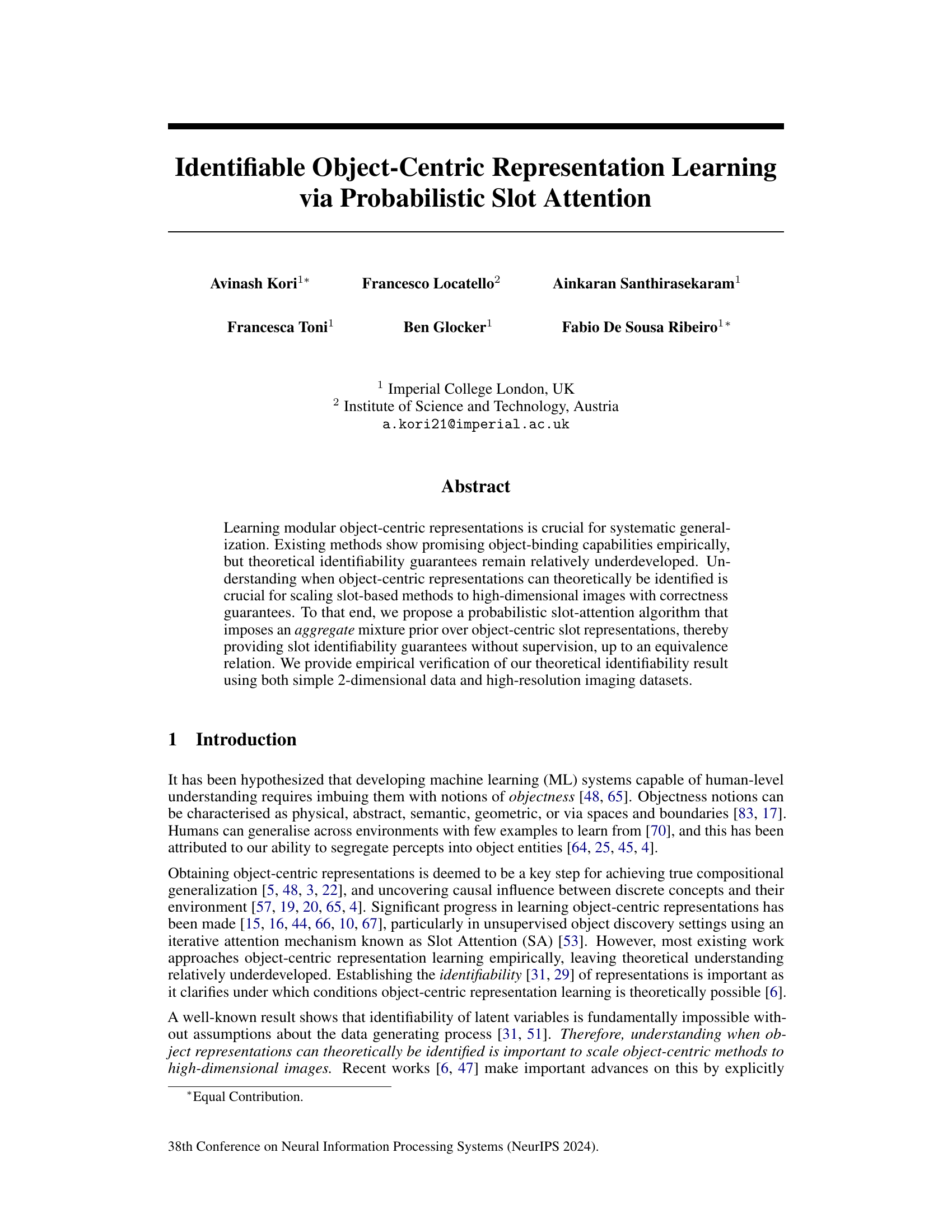

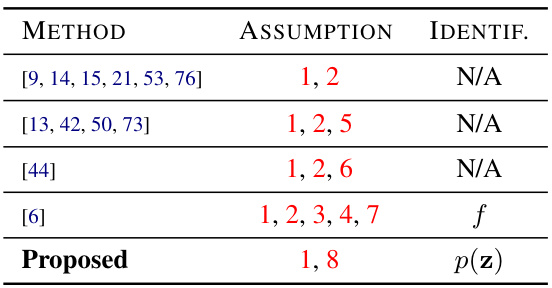

The table compares several object-centric learning methods based on their identifiability strategies, assumptions, and identifiability guarantees. It lists the methods, their assumptions (B-disentanglement, additive decoder, irreducibility, compositionality), and whether they provide identifiability guarantees for object representations (slots). The proposed method is highlighted, showcasing its improved identifiability guarantees with fewer assumptions.

In-depth insights#

Probabilistic SA#

Probabilistic Slot Attention (PSA) offers a novel approach to object-centric representation learning by introducing a probabilistic framework into the traditional Slot Attention mechanism. Instead of deterministic slot updates, PSA employs a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) to model the posterior distribution of slot representations, making it a generative model capable of learning more structured object representations. This probabilistic formulation is crucial as it enables the derivation of theoretical identifiability guarantees for the learned slot representations, a significant advancement over previous empirical-only approaches. The method demonstrates the identifiability of object-centric slots without supervision, overcoming a major limitation in existing object-centric models. The paper shows promising experimental results with its probabilistic slot attention algorithm, which exhibits robustness and scalability, as demonstrated across several datasets, thus paving the way for trustworthy and more reliable object-centric learning models.

Identifiable Slots#

The concept of “Identifiable Slots” in object-centric representation learning centers on the ability to uniquely distinguish and track individual objects within a scene. Identifiability, in this context, means that the learned representations of these objects (the slots) are not arbitrarily interchangeable. The paper likely explores methods to ensure that each slot corresponds to a specific, identifiable object, even across different views or variations. This is crucial for achieving compositional generalization, where the model can correctly combine learned representations to understand new combinations of objects. A key challenge is that simply learning distinct representations doesn’t guarantee identifiability; there might be inherent ambiguities in the data itself. Therefore, the paper likely proposes strategies such as imposing structural constraints on the latent space or developing a probabilistic framework to guarantee slot identifiability. The implications of identifiable slots are significant, paving the way for robust, scalable object-centric models which can accurately reason and generalize about complex scenes.

GMM Prior#

The concept of a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) prior is central to the paper’s approach to learning identifiable object-centric representations. A GMM naturally models the multi-modality inherent in object-centric data; the distinct modes correspond to different objects, and the parameters of the GMM capture properties of these objects. By imposing a GMM prior, the authors introduce structure into the latent space which directly addresses the identifiability problem. This prior enhances the stability and reduces ambiguity in slot representation learning. Instead of relying on restrictive assumptions on mixing functions, the GMM prior leads to theoretically provable identifiability guarantees up to an equivalence relation—a significant contribution. The choice of a GMM prior provides a principled way to handle the permutation invariance naturally present in unsupervised object discovery, promoting robustness and generalizability. Furthermore, the GMM is shown to be empirically stable across multiple runs, confirming its suitability for providing robust object-centric representations.

Empirical Checks#

An Empirical Checks section in a research paper would present evidence supporting the paper’s claims. This would likely involve experiments on datasets, comparing the proposed method’s performance against existing baselines using relevant metrics. Quantitative results such as accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, or AUC would be essential, accompanied by statistical significance tests to demonstrate the method’s effectiveness. The choice of datasets is crucial; sufficiently diverse datasets would strengthen the findings. Visualizations such as graphs, charts, or images would further illustrate the performance. A thorough analysis of these results, discussing both strengths and weaknesses, is vital to provide a balanced and credible evaluation. Ablation studies would systematically vary components to isolate the effects of each and justify design choices. Furthermore, a robust Empirical Checks section would address potential biases or limitations of the experiments, acknowledging any shortcomings and suggesting future directions for improvement.

Future Works#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore relaxing the piecewise affine assumption on the decoder, potentially through the use of more flexible function approximators while still maintaining identifiability. Investigating the effects of object occlusion and shared object boundaries on the identifiability results is crucial for real-world applicability. A more robust approach to automatic relevance determination of slots could be developed, perhaps by incorporating Bayesian methods or sparsity-inducing priors more explicitly. It would also be valuable to empirically evaluate the impact of different prior distributions on the identifiability and performance of the model, beyond the Gaussian Mixture Model used in this study. Finally, a thorough exploration of the relationship between the proposed probabilistic slot attention and existing methods such as VAEs and probabilistic capsule networks would enrich our understanding of object-centric representation learning and pave the way for novel hybrid approaches.

More visual insights#

More on figures

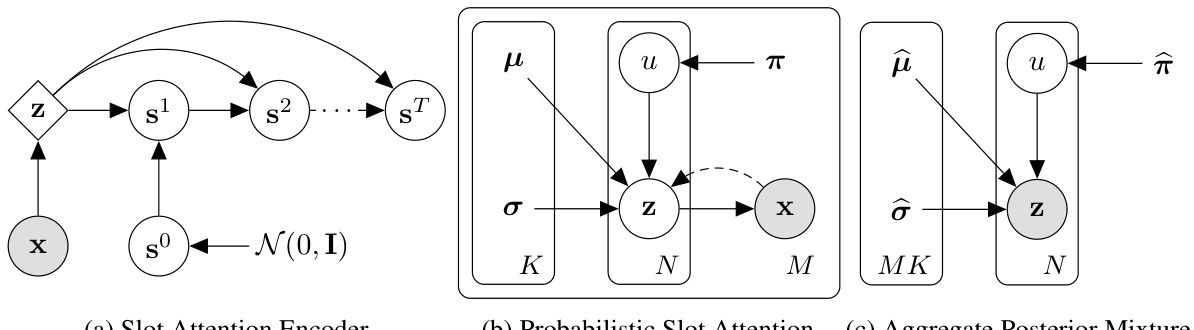

This figure shows three graphical models illustrating the probabilistic slot attention approach. (a) depicts the standard slot attention encoder with T iterations. (b) details the proposed probabilistic model where each image’s latent representation is modeled by a local Gaussian mixture model (GMM) with K components. The K Gaussians represent the posterior distributions for each slot. (c) illustrates the aggregate posterior distribution, obtained by marginalizing the local GMMs, which serves as the optimal prior for the slots. This aggregate posterior is shown to be a tractable, non-degenerate GMM, empirically stable across different runs, and usable for tasks like scene composition.

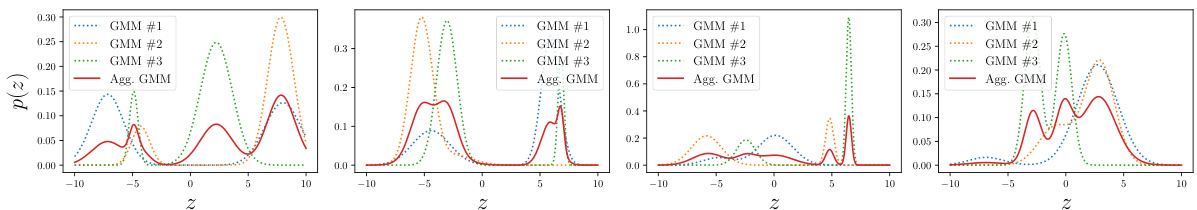

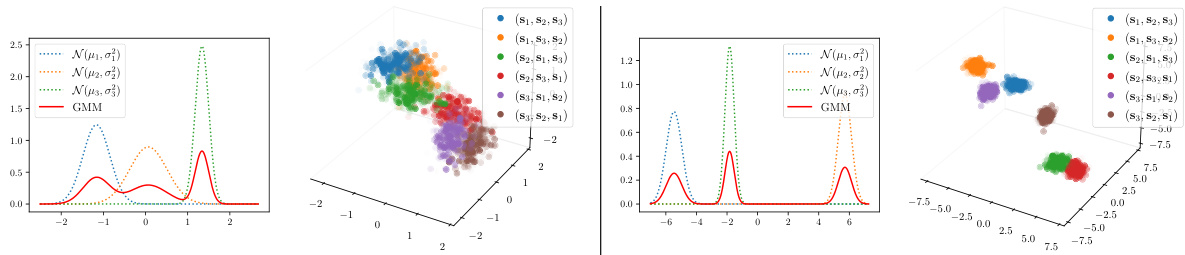

This figure shows examples of aggregate posterior distributions (red lines) obtained by combining three random bimodal Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs). Each set of three GMMs (blue, orange, green dotted lines) represents the local GMMs from the probabilistic slot attention algorithm, and the resulting aggregate GMM (red line) represents the learned prior q(z) over the slots. The figure demonstrates that the aggregate GMM is non-degenerate and stable, which is a key element of the theoretical identifiability results.

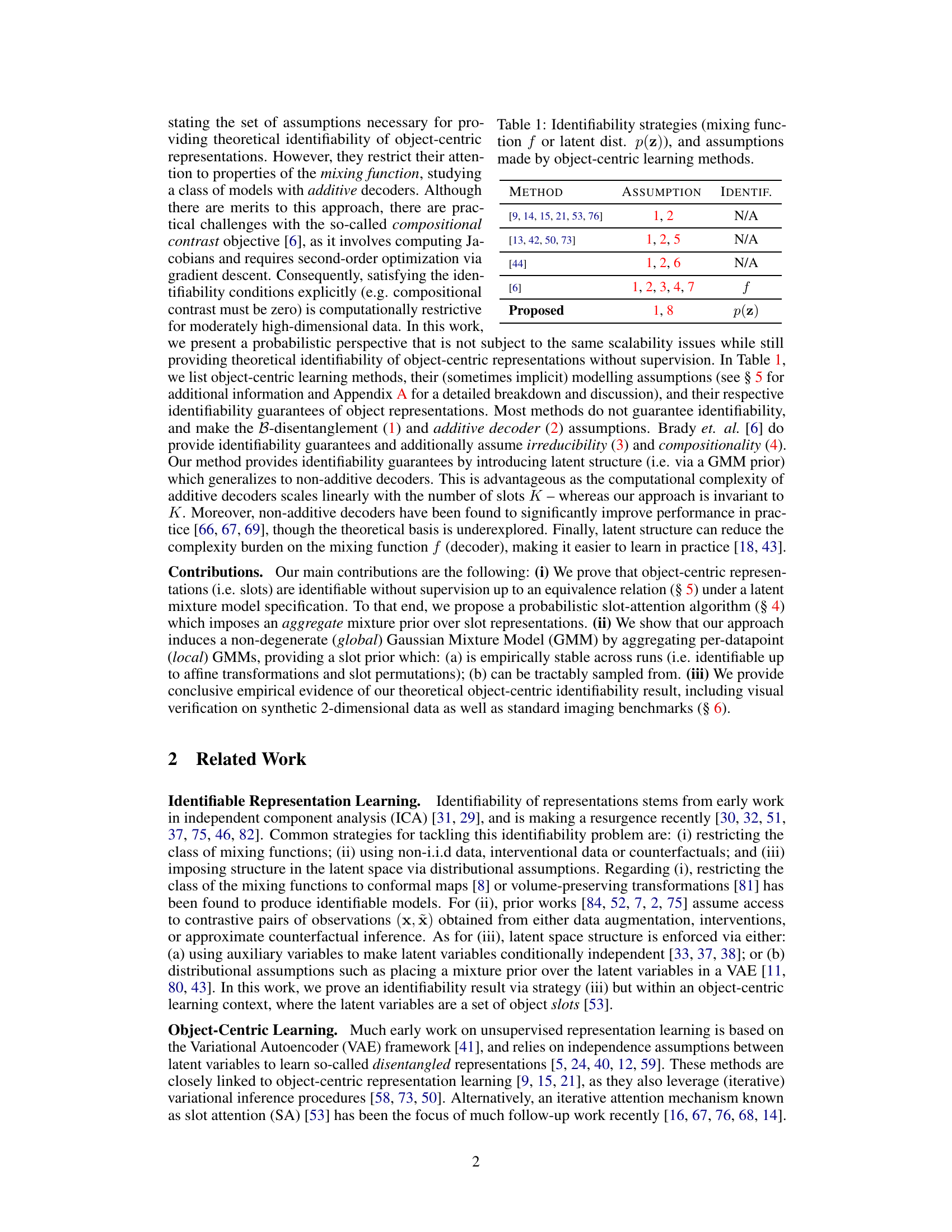

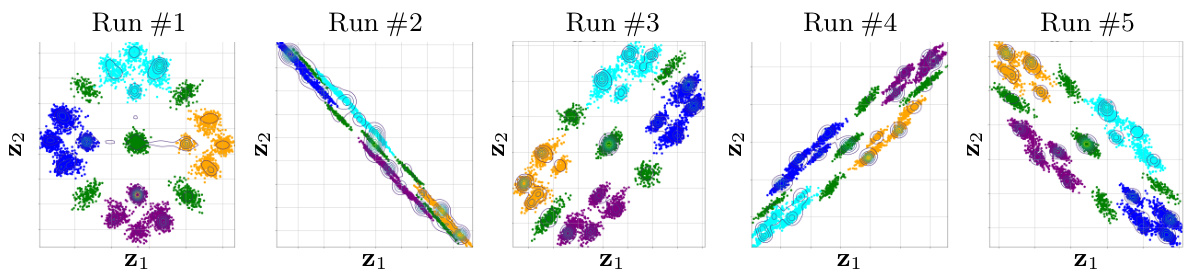

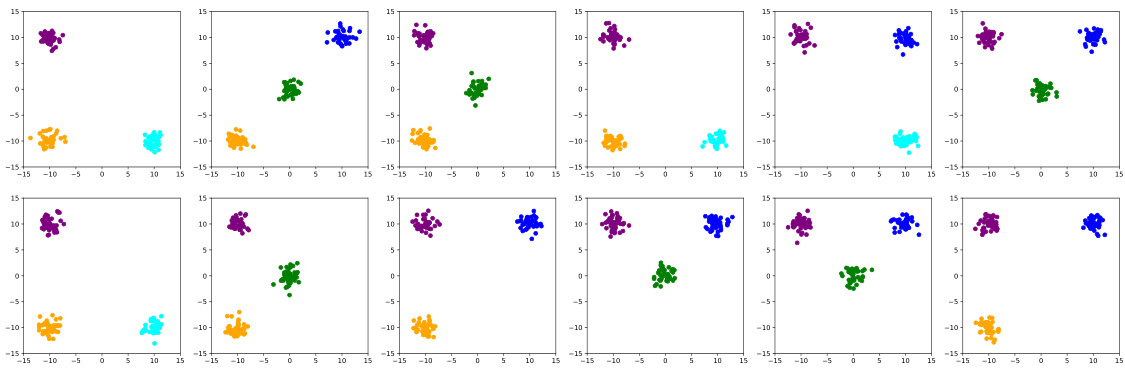

This figure shows the results of 5 independent runs of the Probabilistic Slot Attention (PSA) model on a synthetic 2D dataset. Each run resulted in a learned aggregate posterior distribution, q(z), representing the learned latent space. Despite the different random initializations for each run, the resulting distributions are nearly identical up to affine transformations (rotation, scaling, and translation), which are common transformations that do not change the underlying structure or information contained in the data. This empirically validates the theoretical claim that the PSA model can learn identifiable object-centric representations, even without supervision.

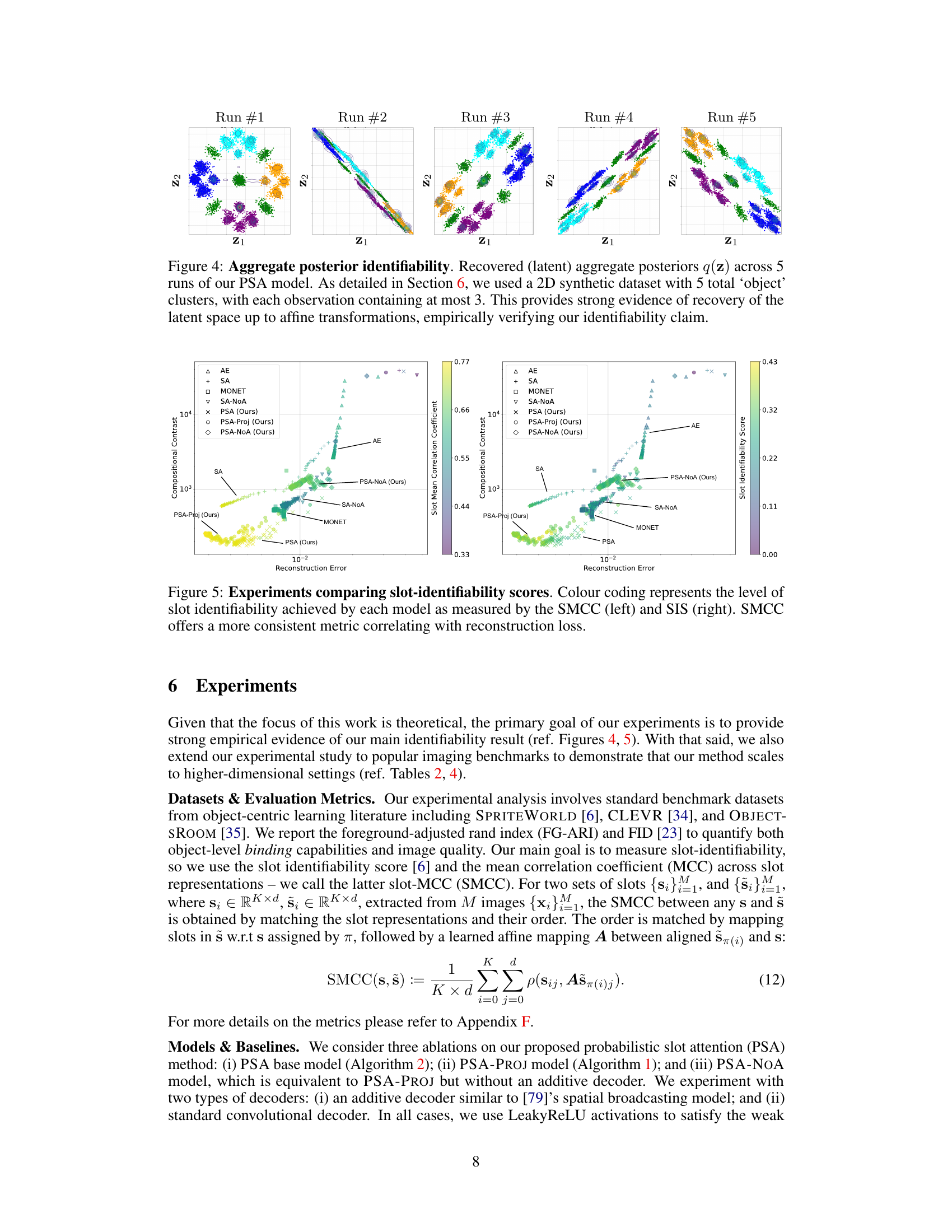

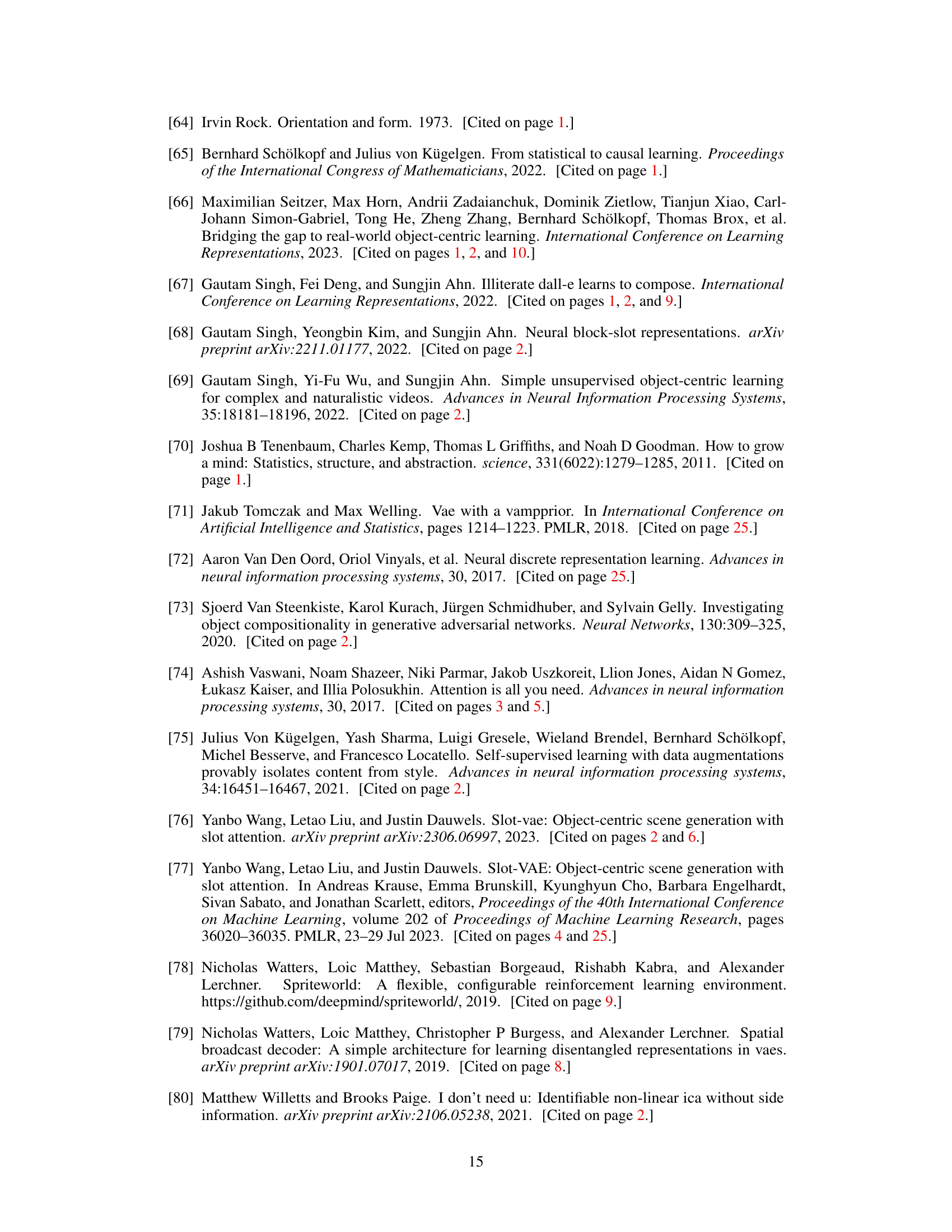

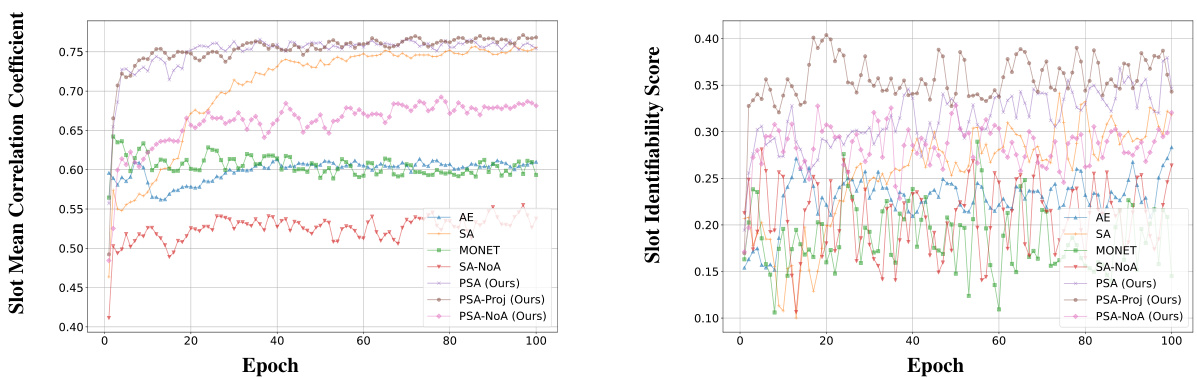

This figure compares different object-centric learning models based on their slot identifiability. Two metrics are used: Slot Mean Correlation Coefficient (SMCC) and Slot Identifiability Score (SIS). The SMCC is highlighted as a more reliable metric that shows a stronger correlation with reconstruction error. The color-coding helps visualize the performance of each model, making it easier to compare them. The plot suggests that the proposed Probabilistic Slot Attention (PSA) method achieves a higher slot identifiability score than other baselines.

This figure shows how the permutation equivariance of slot attention leads to a higher-dimensional Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM). Starting with a simple 1D GMM with three modes (representing three different slot distributions), the permutation of slots generates a 3D GMM with 6 modes (3! = 6 permutations). The top panel shows the 1D GMMs and resulting mixture while the bottom panel shows a 3D visualization of the resulting 6 modes from the slot permutations.

This figure shows examples of aggregate posterior mixtures obtained by combining three random bimodal Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs). Each bimodal GMM represents the local slot posterior from a single data point. The resulting aggregate GMM is a mixture of the three local GMMs, reflecting the overall distribution of slot representations across the dataset. The red line represents the aggregate GMM, demonstrating the stable, identifiable distribution of learned object representations (slots).

This figure shows how the permutation equivariance property of the slot attention mechanism leads to a higher-dimensional Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM) when concatenating slot samples. It starts with a simple 1D GMM (3 modes, representing 3 different slot distributions). Due to the permutation equivariance, there are K! (3! = 6) possible ways to concatenate the slots, resulting in a 3D GMM with 6 modes. Each mode in the 3D GMM corresponds to a unique ordering of the slots. This illustrates how the model’s inherent symmetry affects the representation’s structure.

The figure shows the training curves of two metrics used to evaluate the identifiability of object-centric representations learned by different models, including the proposed Probabilistic Slot Attention (PSA) and baselines. The Slot Mean Correlation Coefficient (SMCC) is a more stable and consistent metric showing that PSA demonstrates significantly better identifiability of representations.

This figure shows the results of running the Probabilistic Slot Attention (PSA) model five times on a 2D synthetic dataset. Each run produced a slightly different aggregate posterior distribution (q(z)), due to the random initialization in the model. The fact that these distributions are all very similar, differing only by affine transformations (rotation, translation, scaling), demonstrates that the model consistently recovers the same latent space structure, supporting the paper’s claim of identifiability up to affine transformations.

This figure shows the results of applying Automatic Relevance Determination (ARD) to the slots in the OBJECTSROOM dataset using the proposed probabilistic slot attention algorithm. The mixing coefficients (πk) for each slot (k) are displayed, showing that inactive slots have mixing coefficients that approach zero. This demonstrates the effectiveness of ARD in automatically pruning irrelevant slots from the model.

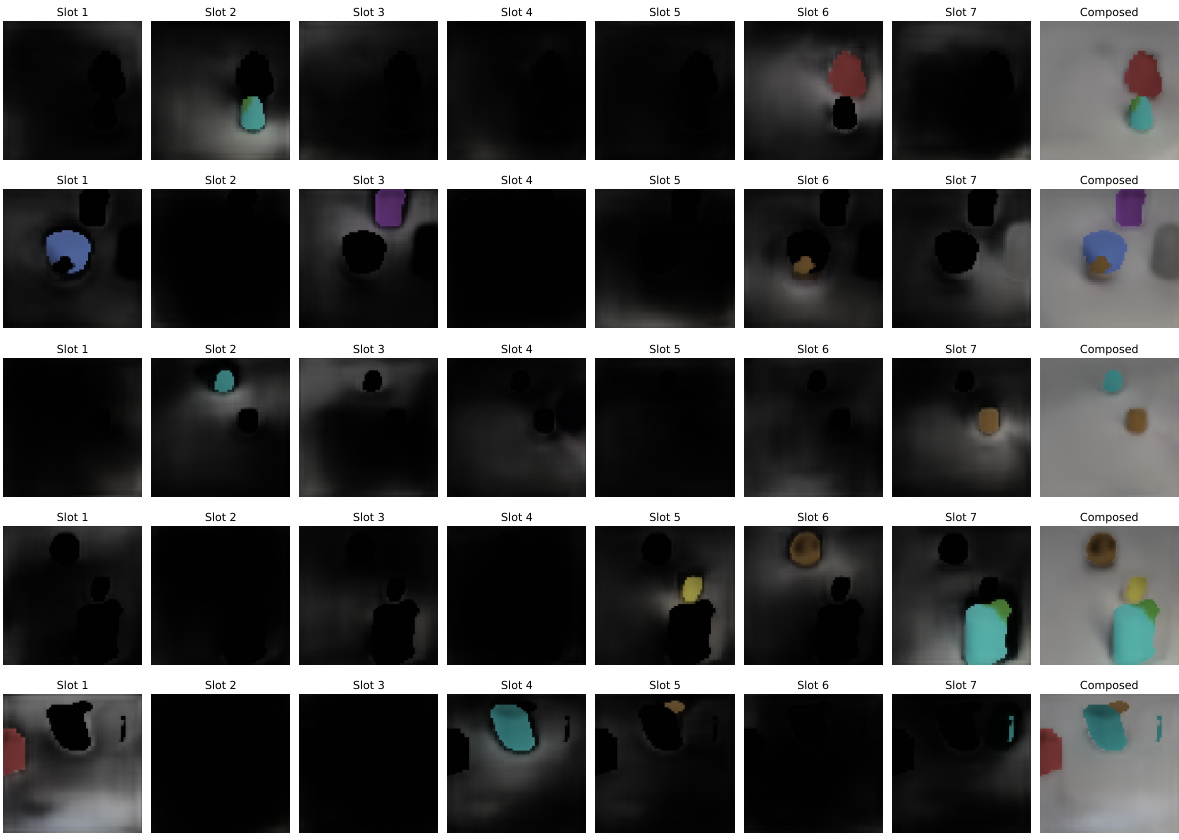

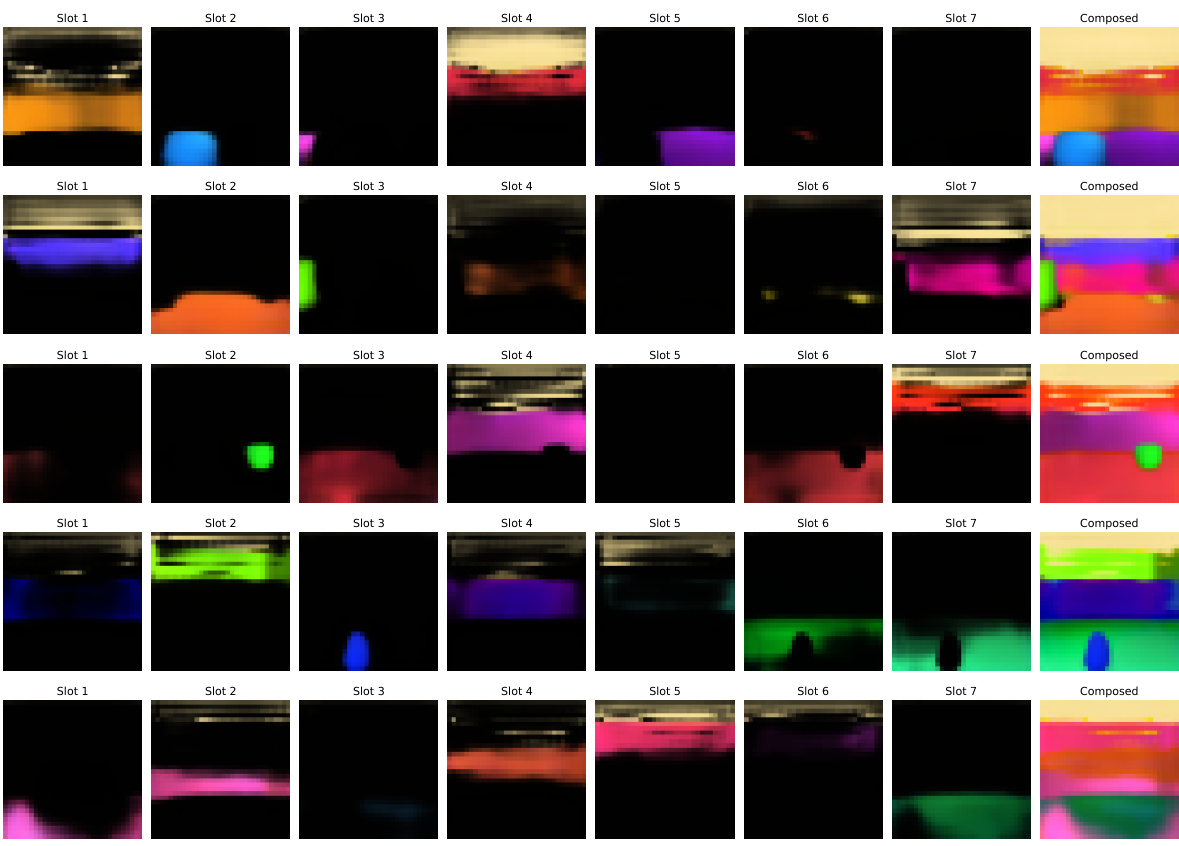

This figure shows the results of image composition on the OBJECTSROOM dataset using aggregate posterior sampling. The figure displays several example images, each broken down into its individual object slots (Slot 1 through Slot 7) and the final recomposed image. This demonstrates the model’s ability to disentangle objects and recompose them into new images.

This figure shows the effectiveness of the proposed automatic relevance determination (ARD) method for pruning inactive slots in the OBJECTSROOM dataset. The mixing coefficients for each slot (πi) are displayed, indicating that when a slot is not relevant to the image, its corresponding mixing coefficient approaches zero. This demonstrates the method’s ability to dynamically determine the relevant number of slots for each input image.

This figure shows the results of applying automatic relevance determination (ARD) to the slots in the OBJECTSROOM dataset. The mixing coefficients (πₖ) for each slot (k) are displayed for several example images, and it is shown that when a slot is not needed to reconstruct an image (i.e., it’s inactive), its mixing coefficient approaches zero. This demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed ARD method for automatically determining the relevant number of slots needed for each input image.

This figure shows the results of applying Automatic Relevance Determination (ARD) to the slots in the OBJECTSROOM dataset using the proposed probabilistic slot attention algorithm. The mixing coefficients (πi) for each slot are displayed, and it can be seen that they tend to zero when a slot is not needed for reconstructing the image, indicating that the model effectively learns to use only the necessary slots.

More on tables

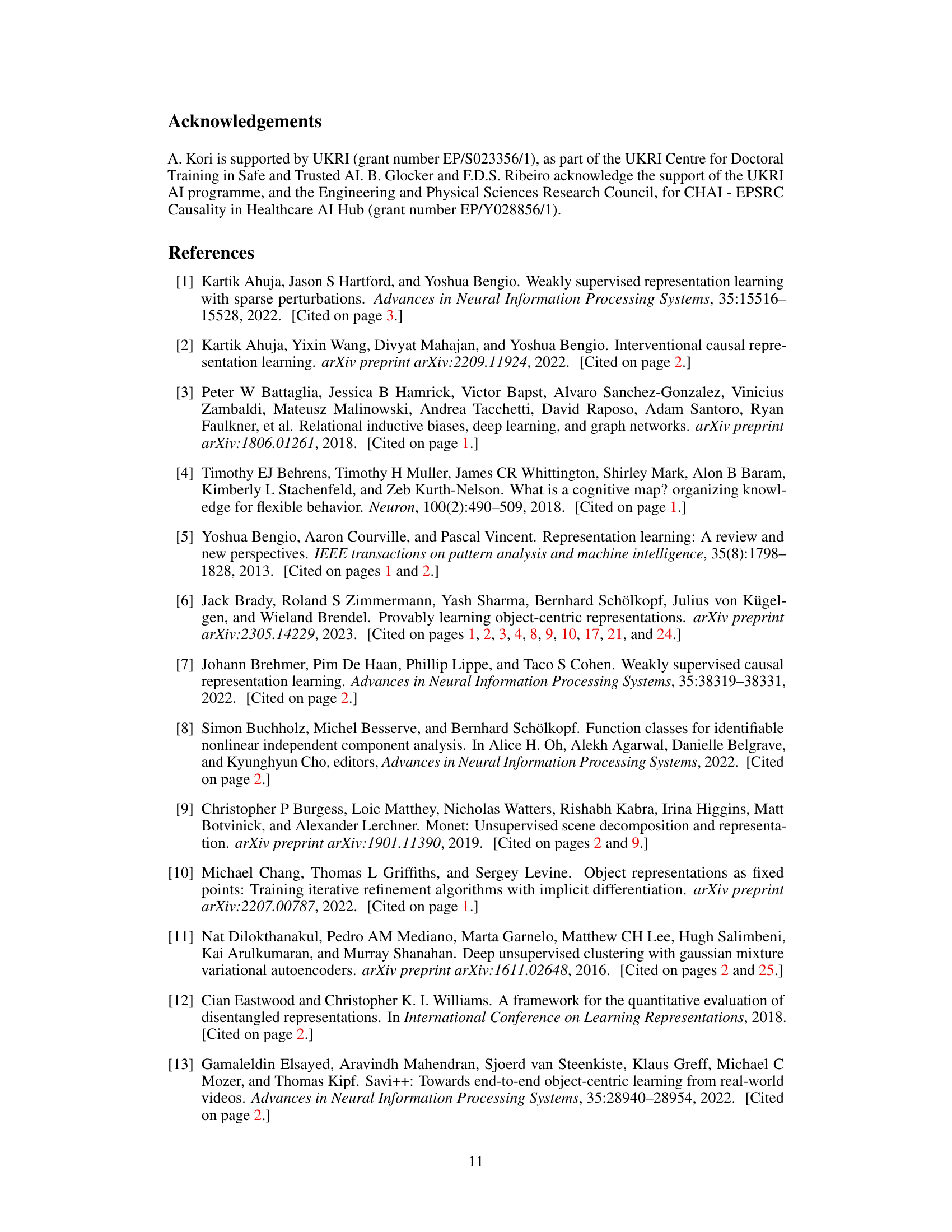

This table compares different object-centric learning methods based on their identifiability strategies and the assumptions made. It shows the assumptions (regarding mixing functions or latent distributions) made by each method and whether they provide identifiability guarantees for object-centric representations. The methods are categorized based on what assumptions are made to achieve identifiability. The proposed method is included and compared against the existing methods.

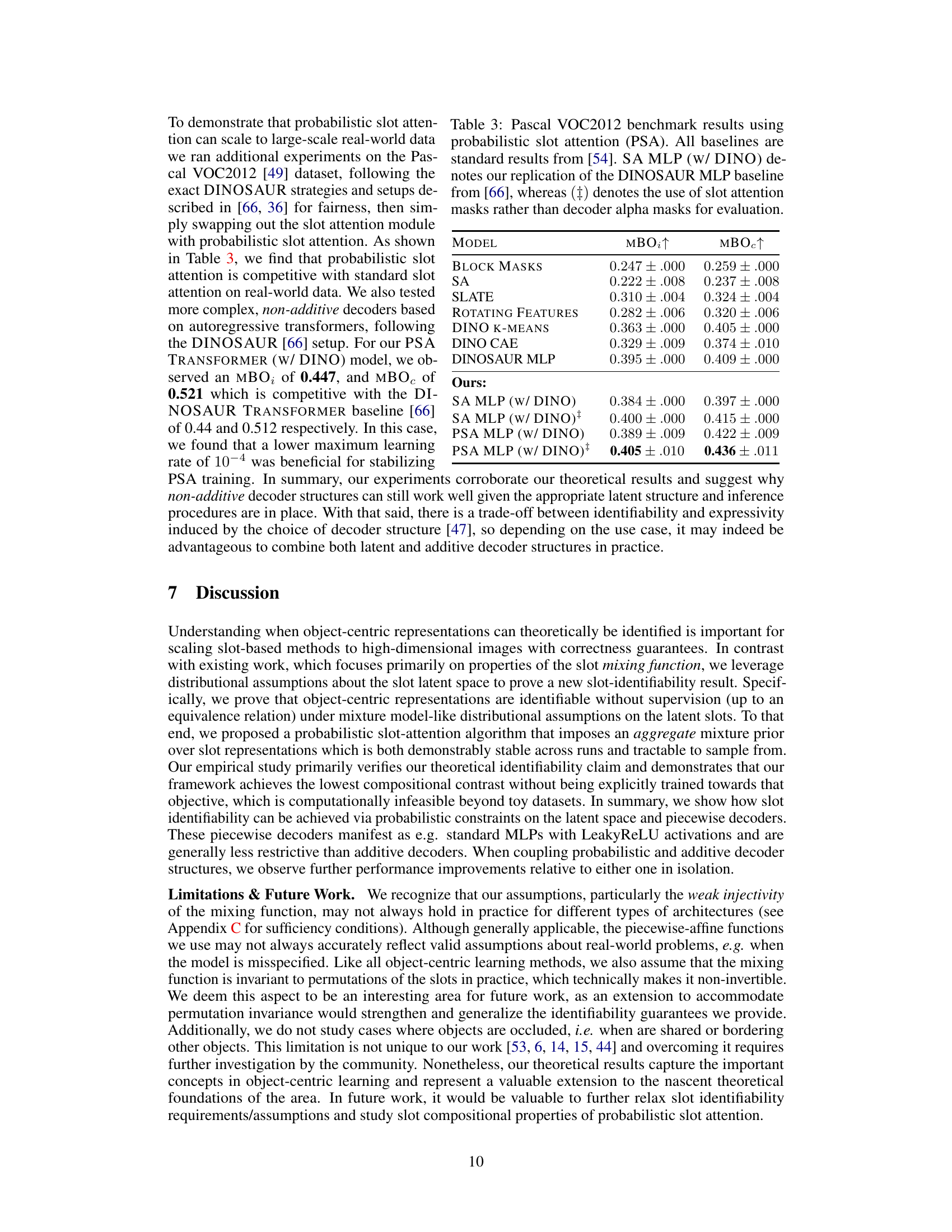

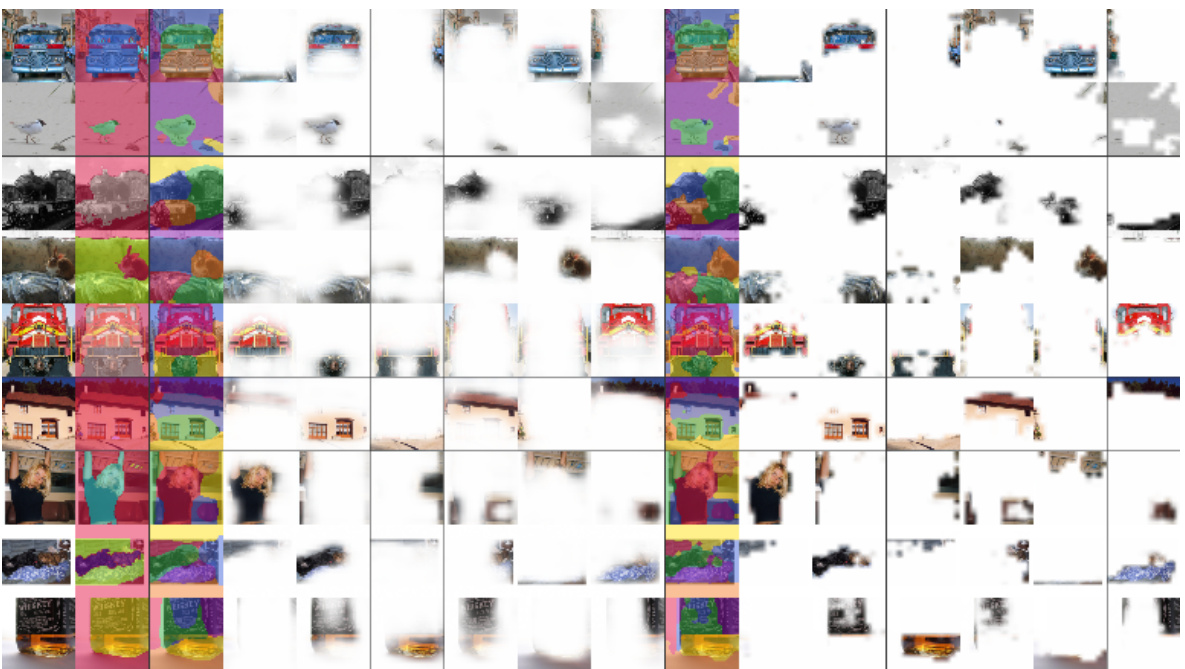

This table presents the Pascal VOC2012 benchmark results for various models, including the proposed probabilistic slot attention (PSA) model and several baselines. The results are compared using Mean Bounding Box Overlap (MBO) and Mean Bounding Box Overlap considering only the foreground (MBOc). The table highlights the performance of PSA compared to existing methods and different configurations of the PSA model, illustrating its competitiveness in a challenging real-world image dataset.

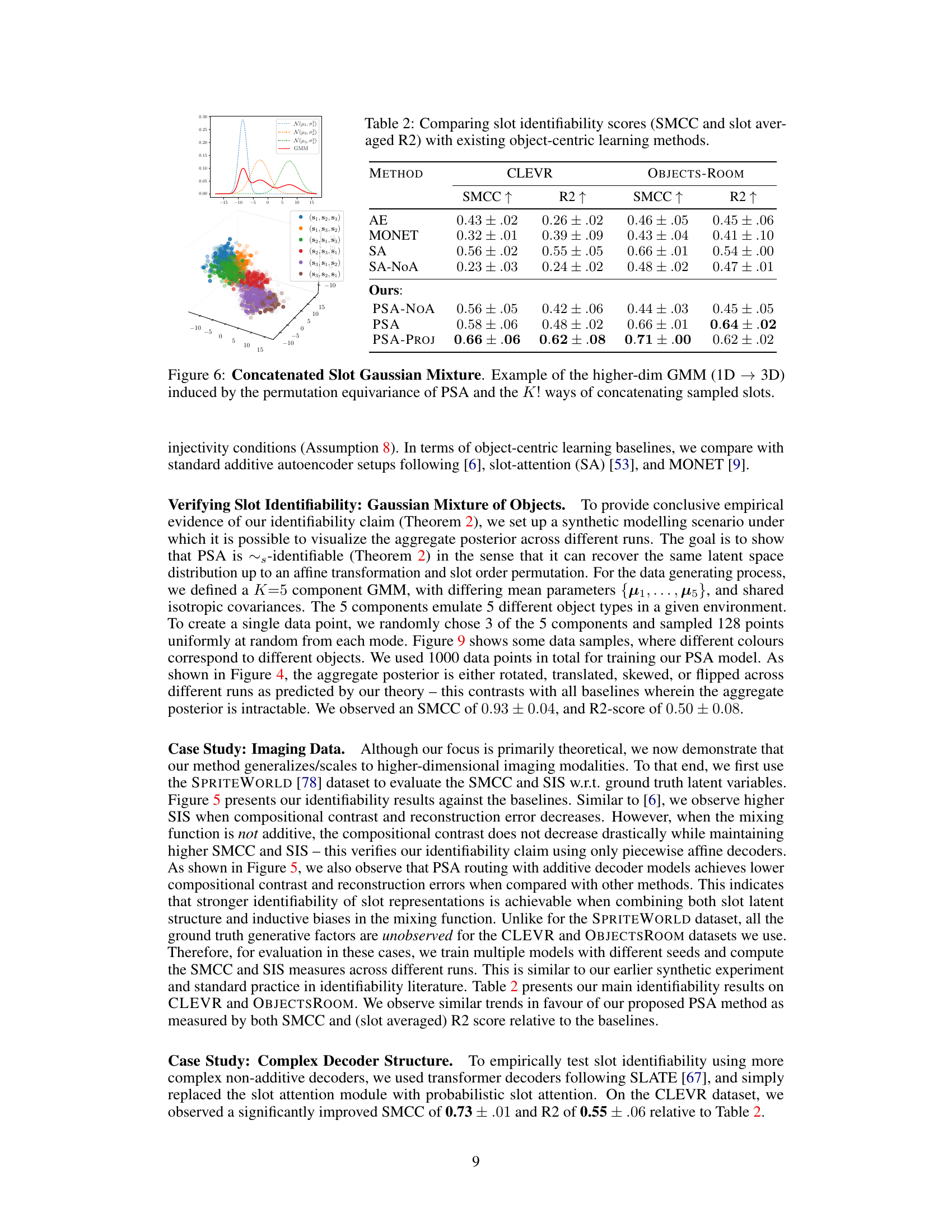

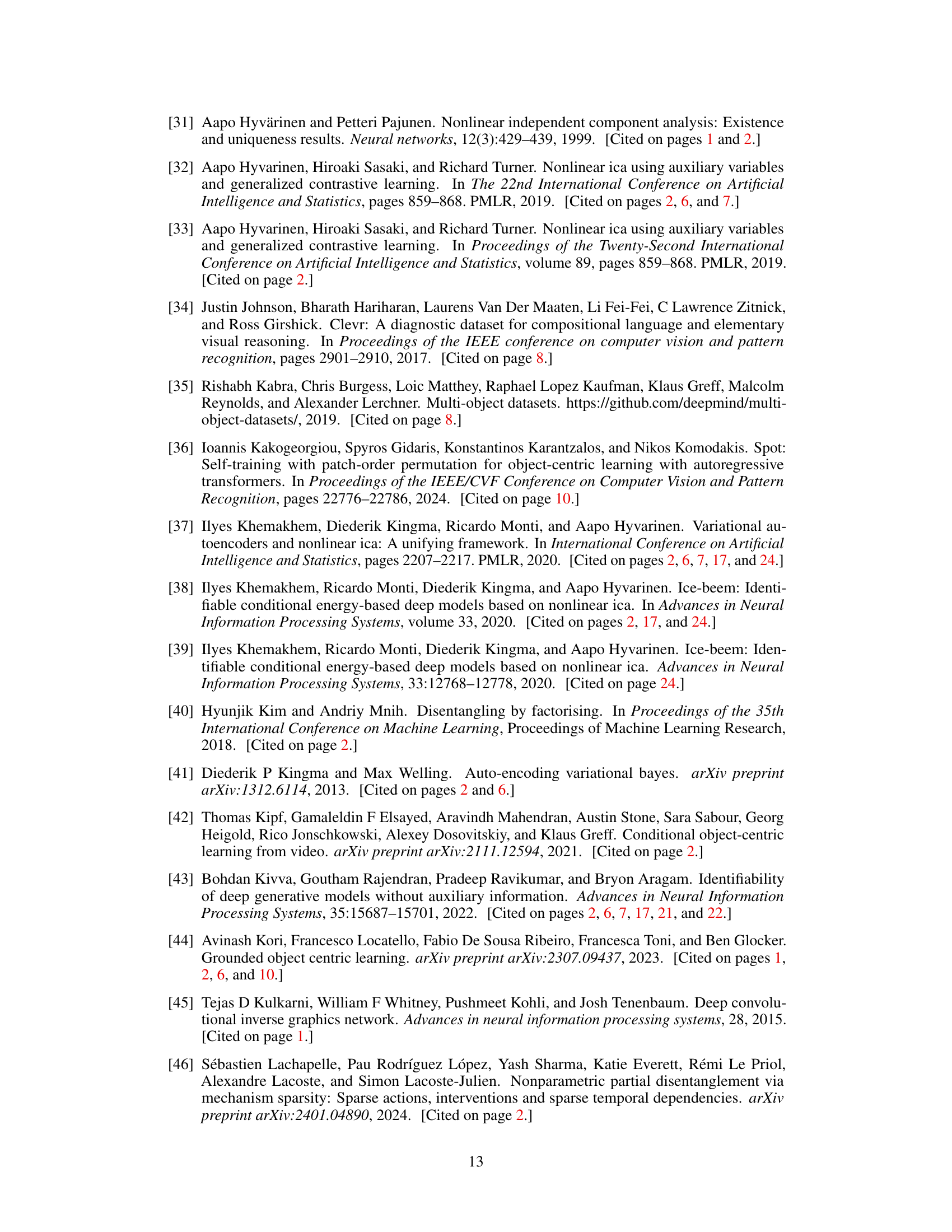

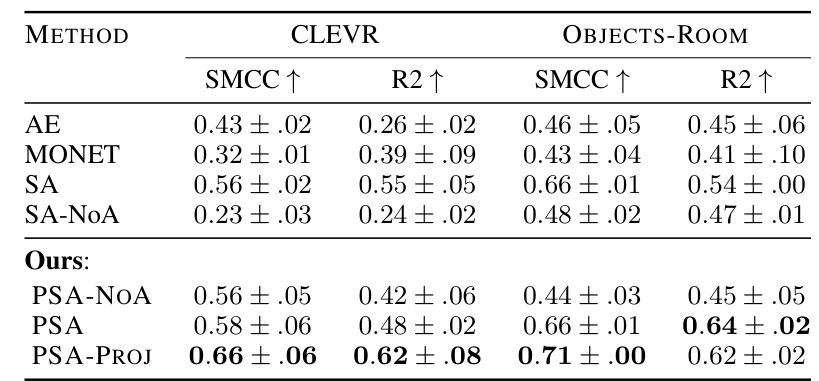

This table compares the performance of the proposed Probabilistic Slot Attention (PSA) method against several existing object-centric learning methods on the CLEVR and Objects-Room datasets. The comparison is based on two metrics: SMCC (Slot Mean Correlation Coefficient), which measures the correlation between estimated and ground truth slot representations, and R2, which quantifies the goodness of fit between the estimated and ground truth slot representations. Higher SMCC and R2 values indicate better slot identifiability. The table shows PSA achieving higher scores than the baselines, demonstrating its improved capability in learning identifiable object-centric representations.

Full paper#